User login

Sjögren’s syndrome most common extrahepatic PBC manifestation

Extrahepatic manifestations of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) occur in 73% of patients, with Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and systemic sclerosis being the most common, according to a literature review from Sara Chalifoux, MD, and her associates.

Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in 3.5%-73% of PBC patients, usually presenting with dry eyes and oral complications. Sjögren’s treatment in PBC patients involves symptom management associated with exocrine gland infiltration.

Thyroid diseases are present in 5.6%-23.6% of PBC patients. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common hypothyroidism in PBC patients, presenting with symptoms such as constipation, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, and inability to concentrate. Grave’s disease is the most common hyperthyroidism, presenting with symptoms such as palpitations, tremulousness, heat intolerance, and weight loss.

Systemic sclerosis occurs in 1.4%-12.3% of PBC patients. Multiple studies found that limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was more common in PBC patients than was the diffuse form of the disease.

Other diseases that may have a connection to PBC but lack solid, compelling evidence to make a firm association include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and celiac disease. While many PBC patients have irritable bowel disorder, there is no significant association between the two conditions.

“The patient care team should include practitioners in rheumatology, endocrinology, pulmonology, and cardiology when indicated. Patients should follow up regularly with their primary care physicians. As some of these extrahepatic manifestations can lead to diseases with a poor prognosis, vigilant screening and close follow-up will lead to prompt identification and treatment,” the investigators noted.

The investigators reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Find the full study in Gut and Liver (doi: 10.5009/gnl16365).

Extrahepatic manifestations of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) occur in 73% of patients, with Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and systemic sclerosis being the most common, according to a literature review from Sara Chalifoux, MD, and her associates.

Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in 3.5%-73% of PBC patients, usually presenting with dry eyes and oral complications. Sjögren’s treatment in PBC patients involves symptom management associated with exocrine gland infiltration.

Thyroid diseases are present in 5.6%-23.6% of PBC patients. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common hypothyroidism in PBC patients, presenting with symptoms such as constipation, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, and inability to concentrate. Grave’s disease is the most common hyperthyroidism, presenting with symptoms such as palpitations, tremulousness, heat intolerance, and weight loss.

Systemic sclerosis occurs in 1.4%-12.3% of PBC patients. Multiple studies found that limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was more common in PBC patients than was the diffuse form of the disease.

Other diseases that may have a connection to PBC but lack solid, compelling evidence to make a firm association include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and celiac disease. While many PBC patients have irritable bowel disorder, there is no significant association between the two conditions.

“The patient care team should include practitioners in rheumatology, endocrinology, pulmonology, and cardiology when indicated. Patients should follow up regularly with their primary care physicians. As some of these extrahepatic manifestations can lead to diseases with a poor prognosis, vigilant screening and close follow-up will lead to prompt identification and treatment,” the investigators noted.

The investigators reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Find the full study in Gut and Liver (doi: 10.5009/gnl16365).

Extrahepatic manifestations of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) occur in 73% of patients, with Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and systemic sclerosis being the most common, according to a literature review from Sara Chalifoux, MD, and her associates.

Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in 3.5%-73% of PBC patients, usually presenting with dry eyes and oral complications. Sjögren’s treatment in PBC patients involves symptom management associated with exocrine gland infiltration.

Thyroid diseases are present in 5.6%-23.6% of PBC patients. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common hypothyroidism in PBC patients, presenting with symptoms such as constipation, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, and inability to concentrate. Grave’s disease is the most common hyperthyroidism, presenting with symptoms such as palpitations, tremulousness, heat intolerance, and weight loss.

Systemic sclerosis occurs in 1.4%-12.3% of PBC patients. Multiple studies found that limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis was more common in PBC patients than was the diffuse form of the disease.

Other diseases that may have a connection to PBC but lack solid, compelling evidence to make a firm association include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and celiac disease. While many PBC patients have irritable bowel disorder, there is no significant association between the two conditions.

“The patient care team should include practitioners in rheumatology, endocrinology, pulmonology, and cardiology when indicated. Patients should follow up regularly with their primary care physicians. As some of these extrahepatic manifestations can lead to diseases with a poor prognosis, vigilant screening and close follow-up will lead to prompt identification and treatment,” the investigators noted.

The investigators reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Find the full study in Gut and Liver (doi: 10.5009/gnl16365).

FROM GUT AND LIVER

Low-dose aspirin bests dual-antiplatelet therapy in TAVR

PARIS – Single-antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) reduced the occurrence of major adverse events, compared with guideline-recommended dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in the randomized ARTE trial.

The TAVR guideline recommendation for DAPT with low-dose aspirin plus clopidogrel is not based on evidence. It relies on expert opinion. ARTE (Aspirin Versus Aspirin + Clopidogrel Following TAVR) is the first sizable randomized trial to address the safety and efficacy of aspirin alone versus DAPT in the setting of TAVR, Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, noted in presenting the ARTE results at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

ARTE was a multicenter, prospective, international open-label study of 222 TAVR patients who were randomized to 3 months of single-antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day or to DAPT with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day plus clopidogrel at 75 mg/day after a single 300-mg loading dose. Participants had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality score of 6.3%. The vast majority of participants received the balloon-expandable Edwards Lifesciences Sapien XT valve. The remainder got the Sapien 3 valve.

The primary outcome was the 3-month composite of death, MI, major or life-threatening bleeding, or stroke or transient ischemic attack. It occurred in 15.3% of the DAPT group and 7.2% on SAPT, a difference that didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .065) because of small patient numbers.

All subjects were on a proton pump inhibitor. The type, timing, and severity of bleeding events differed between the two study arms. All 4 bleeding events in the SAPT group were vascular in nature, while 5 of the 12 in the DAPT group were gastrointestinal. All the bleeding events in the SAPT group occurred within 72 hours after TAVR, whereas 5 of 12 in the DAPT recipients occurred later. Only one patient on SAPT experienced life-threatening bleeding, compared with seven DAPT patients who did.

“There were two prior smaller studies before ours,” according to Dr. Rodés-Cabau of Laval University in Quebec City. “One showed no differences, and an Italian one showed a tendency toward more bleeding with DAPT. So, I think there has been no sign to date that adding clopidogrel protects this group of patients from anything.”

Discussant Luis Nombela-Franco, MD, an interventional cardiologist at San Carlos Hospital in Madrid, pronounced the ARTE trial guideline-changing despite its limitations.

ARTE was supported by grants from Edwards Lifesciences and the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Rodés-Cabau’s presentation in Paris, the ARTE trial was published online (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 11. pii: S1936-8798[17]30812-9).

PARIS – Single-antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) reduced the occurrence of major adverse events, compared with guideline-recommended dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in the randomized ARTE trial.

The TAVR guideline recommendation for DAPT with low-dose aspirin plus clopidogrel is not based on evidence. It relies on expert opinion. ARTE (Aspirin Versus Aspirin + Clopidogrel Following TAVR) is the first sizable randomized trial to address the safety and efficacy of aspirin alone versus DAPT in the setting of TAVR, Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, noted in presenting the ARTE results at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

ARTE was a multicenter, prospective, international open-label study of 222 TAVR patients who were randomized to 3 months of single-antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day or to DAPT with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day plus clopidogrel at 75 mg/day after a single 300-mg loading dose. Participants had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality score of 6.3%. The vast majority of participants received the balloon-expandable Edwards Lifesciences Sapien XT valve. The remainder got the Sapien 3 valve.

The primary outcome was the 3-month composite of death, MI, major or life-threatening bleeding, or stroke or transient ischemic attack. It occurred in 15.3% of the DAPT group and 7.2% on SAPT, a difference that didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .065) because of small patient numbers.

All subjects were on a proton pump inhibitor. The type, timing, and severity of bleeding events differed between the two study arms. All 4 bleeding events in the SAPT group were vascular in nature, while 5 of the 12 in the DAPT group were gastrointestinal. All the bleeding events in the SAPT group occurred within 72 hours after TAVR, whereas 5 of 12 in the DAPT recipients occurred later. Only one patient on SAPT experienced life-threatening bleeding, compared with seven DAPT patients who did.

“There were two prior smaller studies before ours,” according to Dr. Rodés-Cabau of Laval University in Quebec City. “One showed no differences, and an Italian one showed a tendency toward more bleeding with DAPT. So, I think there has been no sign to date that adding clopidogrel protects this group of patients from anything.”

Discussant Luis Nombela-Franco, MD, an interventional cardiologist at San Carlos Hospital in Madrid, pronounced the ARTE trial guideline-changing despite its limitations.

ARTE was supported by grants from Edwards Lifesciences and the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Rodés-Cabau’s presentation in Paris, the ARTE trial was published online (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 11. pii: S1936-8798[17]30812-9).

PARIS – Single-antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) reduced the occurrence of major adverse events, compared with guideline-recommended dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in the randomized ARTE trial.

The TAVR guideline recommendation for DAPT with low-dose aspirin plus clopidogrel is not based on evidence. It relies on expert opinion. ARTE (Aspirin Versus Aspirin + Clopidogrel Following TAVR) is the first sizable randomized trial to address the safety and efficacy of aspirin alone versus DAPT in the setting of TAVR, Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, noted in presenting the ARTE results at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

ARTE was a multicenter, prospective, international open-label study of 222 TAVR patients who were randomized to 3 months of single-antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day or to DAPT with aspirin at 80-100 mg/day plus clopidogrel at 75 mg/day after a single 300-mg loading dose. Participants had a mean Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality score of 6.3%. The vast majority of participants received the balloon-expandable Edwards Lifesciences Sapien XT valve. The remainder got the Sapien 3 valve.

The primary outcome was the 3-month composite of death, MI, major or life-threatening bleeding, or stroke or transient ischemic attack. It occurred in 15.3% of the DAPT group and 7.2% on SAPT, a difference that didn’t reach statistical significance (P = .065) because of small patient numbers.

All subjects were on a proton pump inhibitor. The type, timing, and severity of bleeding events differed between the two study arms. All 4 bleeding events in the SAPT group were vascular in nature, while 5 of the 12 in the DAPT group were gastrointestinal. All the bleeding events in the SAPT group occurred within 72 hours after TAVR, whereas 5 of 12 in the DAPT recipients occurred later. Only one patient on SAPT experienced life-threatening bleeding, compared with seven DAPT patients who did.

“There were two prior smaller studies before ours,” according to Dr. Rodés-Cabau of Laval University in Quebec City. “One showed no differences, and an Italian one showed a tendency toward more bleeding with DAPT. So, I think there has been no sign to date that adding clopidogrel protects this group of patients from anything.”

Discussant Luis Nombela-Franco, MD, an interventional cardiologist at San Carlos Hospital in Madrid, pronounced the ARTE trial guideline-changing despite its limitations.

ARTE was supported by grants from Edwards Lifesciences and the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute.

Simultaneous with Dr. Rodés-Cabau’s presentation in Paris, the ARTE trial was published online (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017 May 11. pii: S1936-8798[17]30812-9).

AT EUROPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 3-month composite of death, MI, major or life-threatening bleeding, or stroke or transient ischemic attack occurred in 15.3% of TAVR patients randomized to DAPT with low-dose aspirin plus clopidogrel, compared with 7.2% on aspirin only.

Data source: A randomized, multicenter, international, prospective open-label trial in 222 TAVR patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research grants from Edwards Lifesciences and the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, which supported the ARTE trial.

Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

From the Division of Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective:To review the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the peer-reviewed literature.

- Results: Effective management of stable COPD requires the physician to apply a stepwise intensification of therapy depending on patient symptoms and functional reserve. Bronchodilators are the cornerstone of management. In addition to pharmacologic therapies, nonpharmacologic therapies, including smoking cessation, vaccinations, proper nutrition, and maintaining physical activity, are an important part of long-term management. Those who continue to be symptomatic despite appropriate maximal therapy may be candidates for lung volume reduction. Palliative care services for COPD patients, which can aid in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life, should not be overlooked.

- Conclusion: Successful management of stable COPD requires a multidisciplinary approach that utilizes various medical therapies as well as nonpharmacologic interventions.

Key words: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; exacerbation; bronchodilator; lung volume reduction; cough.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by irreversible obstructive ventilatory defects [1–4]. It is a major cause of morbidity and mortality affecting 5% of the population in the United States and was the third leading cause of death in 2008 [5,6]. The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. In this review, we will discuss the management of stable COPD in the context of 3 common clinical scenarios.

Case 1

A 65-year-old male with COPD underwent pulmonary function testing (PFT), which demonstrated an obstructive ventilatory defect (forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio [FEV1/FVC], 0.45; FEV1, 2 L [65% of predicted]; and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide [DLCO], 15 [65% of predicted]). He has dyspnea with strenuous exercise but is comfortable at rest and with minimal exercise. He has had 1 exacerbation in the last year that was treated on an outpatient basis with steroids and antibiotics. His medication regimen includes inhaled tiotropium once daily and inhaled albuterol as needed that he uses roughly twice a week.

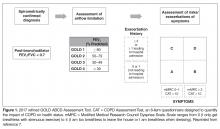

What determines the appropriate therapy for a given COPD patient?

What is the approach to building a pharmacologic regimen for the patient with COPD?

The backbone of the pharmacologic regimen for COPD includes short- and long-acting bronchodilators. They are usually given in an inhaled form to maximize local effects on the lungs and minimize systemic side effects. There are 2 main classes of bronchodilators, beta agonists and muscarinic antagonists, and each targets specific receptors on the surface of airway smooth muscle cells. Beta agonists work by stimulating beta-2 receptors, resulting in bronchodilation, while muscarinic antagonists work by blocking the bronchoconstrictor action of M3 muscarinic receptors. Inhaled corticosteroids can be added to long-acting bronchodilator therapy but cannot be used as stand-alone therapy. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator that is used infrequently due to its narrow therapeutic index, toxicity, and multiple drug interactions.

Who should be on short-acting bronchodilators? What is the best agent? Should it be scheduled or used as needed?

All patients with COPD should be an on inhaled short-acting bronchodilator as needed for relief of symptoms [7]. Both short-acting beta agonists (albuterol and levalbuterol) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium) have been shown in clinical trials and meta-analyses to improve symptoms and lung function in patients with stable COPD [9,10] and seem to have comparative efficacy when compared head-to-head in trials [11]. However, the airway bronchodilator effect achieved by both classes seems to be additive when used in combination and is also associated with less exacerbations compared to albuterol alone [12]. On the other hand, adding albuterol to ipratropium increased the bronchodilator response but did not reduce the exacerbation rate [11–13]. Inhaled short-acting beta agonists when used as needed rather than scheduled are associated with less medication use without any significant difference in symptoms or lung function [14].

The side effects related to using recommended doses of a short-acting bronchodilator are minimal. In retrospective studies, short-acting beta agonists increased the risk of severe cardiac arrhythmias [15]. Levalbuterol, the active enantiomer of albuterol (R-albuterol) developed for the theoretical benefits of reduced tachycardia, increased tolerability, and better or equal efficacy compared to racemic albuterol, failed to show a clinically significant difference in inducing tachycardia [16]. Beta agonist overuse is associated with tremor and in severe cases hypokalemia, which happens mainly when patients try to achieve maximal bronchodilation; the clinically used doses of beta agonists are associated with fewer side affects but achieve less than maximal bronchodilation [17]. Ipratropium can produce systemic anticholinergic side effects, urinary retention being the most clinically significant especially when combined with long-acting anticholinergic agents [18].

In light of the above discussion, a combination of short-acting beta agonist and muscarinic antagonist is recommended in all patients with COPD unless the patient is on a long-acting muscarinic antagonist [7,18]. In the latter case, a short-acting beta agonist used as a rescue inhaler is the best option. In our patient, albuterol was the choice for his short-acting bronchodilator as he was using the long-acting muscarinic antagonist tiotropium.

Are short-acting bronchodilators enough? What do we use for maintenance therapy?

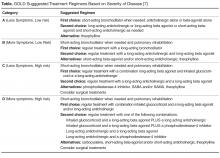

All patients with COPD who are category B or higher according to the modified GOLD staging system should be on a long-acting bronchodilator [7,19]: either a long-acting beta agonist (LABA) or long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA). Long-acting bronchodilators work on the same receptors as their short-acting counterparts but have structural differences. Salmeterol is the prototype for long-acting selective beta-2 agonist. It is structurally similar to albuterol but has an elongated side chain that allows it to bind firmly to the area of beta receptors and stimulate them repetitively, resulting in an extendedduration of action [20]. Tiotropium on the other hand is a quaternary ammonium of ipratropium that is a nonselective muscarinic antagonist [21]. Compared to ipratropium, tiotropium dissociates more quickly from M2 receptors, which is responsible for the undesired anticholinergic effects, while at the same time it binds M1 and M3 receptors for a prolonged time, resulting in extended duration of action [21].

The currently available long-acting beta agonists include salmeterol, formoterol, aformoterol, olodatetol, and indacaterol. The last two have the advantage of once-daily dosing rather than twice [22,23]. LABAs have been shown to improve lung function, exacerbation rate, and quality of life in multiple clinical trials [22–24]. Vilanterol is another LABA that has a long duration of action and can be used once daily [25], but is only available in a combination with umeclidinium, a LAMA. Several LAMAs are approved for use in COPD, including the prototype tiotropium in addition to aclidinium, umeclidinium, and glycopyrronium. These have been shown in clinical trials to improve lung function, symptoms, and exacerbation rate [26–29].

Patients can be started on either a LAMA or LABA depending on patient needs and side effects [7]. Both have comparable side effects and efficacy as detailed below. Concerning side effects, there is conflicting data concerning an association of cardiovascular events with both classes of long-acting bronchodilators. While clinical trials failed to show an increased risk [24,30,31], several retrospective studies showed an increased risk of emergency room visits and hospitalizations due to tachyarrhythmias, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke upon initiation of long-acting bronchodilators [32,33]. There was no difference in risk for adverse cardiovascular events between LABA and LAMA in one Canadian study, and slightly more with LABA in a study using an American database [32,33]. Urinary retention is another possible complication of LAMA supported by evidence from meta-analyses and retrospective studies but not clinical trials and should be discussed with patients upon initiation [34,35]. There have been concerns about increased mortality with the soft mist formulation of tiotropium that were put to rest by the tiotropium safety and performance in Respimat (TIOSPIR) trial, which showed no increased mortality compared to Handihaler [36].

As far as efficacy and benefits, tiotropium and salmeterol were compared head-to-head in a clinical trial, and tiotropium increased the time before developing first exacerbation and decreased the overall rate of exacerbations [37]. No difference in hospitalization rate or mortality was noted in one meta-analysis, although tiotropium was more effective in reducing exacerbations [38]. The choice of agent should be made based on patient comorbidities and side effects. For example, an elderly patient with severe benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary retention should try a LABA while for a patient with severe tachycardia induced by albuterol, LAMA would be a better first agent.

What is the role of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are believed to work in COPD by reducing airway inflammation [39]. ICS should not be used alone for COPD management and are always combined with LABA [7]. Several inhaled corticosteroid formulations are approved for use in COPD, including budesonide and fluticasone. ICS has been shown to decrease symptoms and exacerbations with modest effect on lung function and no change in mortality [40]. Side effects include oral candidiasis, dysphonia, and skin bruising [41]. There is also an increased risk of pneumonia [42]. ICS are best reserved for patients with a component of asthma or asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) [43]. ACOS is characterized by persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD [44].

What if the patient is still symptomatic on a LABA or LAMA?

For patients whose symptoms are not controlled on one class of long-acting bronchodilator, recommendations are to add a bronchodilator from the other class [7]. There are also multiple combined LAMA-LABA inhalers that are approved in the US and can possible improve adherence to therapy. These include tiotropium-oladeterol, umeclidinium-vilanterol, glycopyronnium-indacaterol, and glycopyrrolate-formoterol. In a large systematic review and meta-analysis comparing LABA-LAMA combination to either agent alone, there was a modest improvement in post bronchodilator FEV1 and quality of life with no change in hospital admissions, mortality, or side effects [45]. Interestingly, adding tiotropium to LABA reduced exacerbations although adding LABA to tiotropium did not [45].

Current guidelines recommend that patients in GOLD categories C and D that are not well controlled should receive a combination of LABA-ICS [7]. However, a new randomized trial showed better reduction of exacerbations and decreased occurrence of pneumonia in patients receiving LAMA-LABA compared to LABA-ICS [46]. In light of this new evidence, it is prudent to use a LAMA-LABA combination before adding ICS.

Triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS is a common approach for patients with severe uncontrolled disease and has been shown to decrease exacerbations and improve quality of life [7,47]. Adding tiotropium to LABA-ICS decreased exacerbations and improved quality of life and airflow in the landmark UPLIFT trial [26]. In another clinical trial, triple therapy with LAMA, LABA, and ICS compared to tiotropium alone decreased severe exacerbations, pre-bronchodilator FEV1, and morning symptoms [48].

Is there a role for theophylline? Other agents?

Theophylline

Theophylline is an oral adenosine diphosphate antagonist with indirect adrenergic activity, which is responsible for the bronchodilator therapeutic effect in patients with obstructive lung disease. It is also thought to work by an additional mechanism that decreases inflammation in the airways [49]. It has a serious side effect profile that includes ventricular arrhythmias, seizures, vomiting, and tremor [50]. It is metabolized in the liver and has multiple drug interactions and a narrow therapeutic index. It has been shown to improve lung function, gas exchange and symptoms in meta-analysis and clinical trials [51,52].

In light of the nature of the adverse effects and the wide array of safer and more effective pharmacologic agents available, theophylline should be avoided early on in patients with COPD. Its use can be justified as an add-on therapy in patients with refractory disease on triple therapy for symptomatic relief [50]. If used, the therapeutic range for COPD is 8–12 mcg/mL peak level measured 3 to 7 hours after morning dose and is usually achieved using a daily dose of 10 mg per kilogram of body weight for nonobese patients [53].

Systemic Steroids

Oral steroids are used in COPD exacerbations but should never be used chronically in COPD patients regardless of disease severity as they increase morbidity and mortality without improving symptoms or lung function [54,55]. The dose of systemic steroids should be tapered and finally discontinued.

Mucolytics

Classes of mucolytics include thiol derivatives, inhaled dornase alpha, hypertonic saline, and iodine preparations. Thiol derivatives such as N-acetylcysteine are the most widely studied [56].

There is no consistent evidence of beneficial role of mucolytics in COPD patient [7,56]. The PANTHEON trial showed decreased exacerbations with N-acetylcysteine (1.16 exacerbations per patient-year compared to 1.49 exacerbations per patient-year in the placebo group; risk ratio 0.78, 95% CI 0.67–0.90; P = 0.001) but had methodologic issues including high drop-out rate, exclusion of patients on oxygen, and a large of proportion of nonsmokers [57].

Chronic Antibiotics

There is no role for chronic antibiotics in the management of COPD [7]. Macrolides are an exception but are used for their anti-inflammatory effects rather than their antibiotic effects. They should be reserved for patient with frequent exacerbations on optimal therapy and will be discussed later in the review [58].

What nonpharmacologic treatments are recommended for COPD patients?

Smoking cessation, oxygen therapy for severe hypoxemia (resting O2 saturation ≤ 88 or PaO2 ≤ 55), vaccination for influenza and pneumococcus, and appropriate nutrition should be provided in all COPD patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation is indicated for patients in GOLD categories B, C, and D [7]. It improves symptoms, quality of life, exercise tolerance and health care utilization. Beneficial effects last for about 2 years [59,60].

What other diagnoses should be considered in patients who continue to be symptomatic on optimal therapy?

Other diseases that share the same risk factors as COPD and can contribute to dyspnea, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, thromboembolic disease, and pulmonary hypertension, should be considered. In addition, all patients with refractory disease should have a careful assessment of their inhaler technique, continued smoking, need for oxygen therapy, and associated deconditioning.

Case 2

A 70-year-old male with severe COPD on oxygen therapy and obstructive sleep apnea treated on nocturnal CPAP was seen in the pulmonary clinic for evaluation of his dyspnea. He was symptomatic with minimal activity and had chronic cough with some sputum production. He had been hospitalized 3 times over the past 12 months and had been to the emergency department (ED) the same number of times for dyspnea. Pertinent medications included as-needed albuterol inhaler, inhaled steroids, and tiotropium 18 mcg inhaled daily. He demonstrated good inhaler technique. On examination, his vital signs were pulse 99 bpm, SpO2 94% on 2L/min oxygen by nasal cannula, blood pressure 126/72 mm Hg, respiratory rate 15, and BMI 35 kg/m2. He appeared chronically ill but in no acute distress. No wheezing or rales were heard. He had no lower extremity edema. The remainder of the exam was within normal limits. His last pulmonary function test demonstrated moderate obstruction with significant bronchodilator response to 2 puffs of albuterol. The side effects of chronic steroid therapy were impressed upon the patient and 500 mg of roflumilast was started daily. Over the course of the next 3 months, he had no further exacerbations. Roflumilast was continued. He has not required any further hospitalizations, ED visits, or oral steroid use since the last clinic visit.

What is the significance of acute exacerbations of COPD?

Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) is a frequently observed complication for many patients with COPD [61,62]. AECOPD is associated with accelerated disease progression, augmented decline in health status and quality of life, and increased mortality [63]. Exacerbations account for most of the costs associated with COPD. Estimates suggest that the aggregate costs associated with the treatment of AECOPDs are between $3.2 and $3.8 billion, and that annual health care costs are 10-fold greater for patients with COPD associated with acute exacerbations than for patients with COPD but without exacerbations [64]. Hence, any intervention that could potentially minimize or prevent this complication will have far-reaching benefits to patients with COPD as well as provide significant cost saving.

How is acute exacerbation of COPD defined?

COPD exacerbation is defined as a baseline change of the patient’s dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum that is acute in onset, and may warrant a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD [65]. Exacerbation in clinical trials has been defined on the basis of whether an increase in the level of care beyond regular care is required primarily in the hospital or ED [66]. Frequent exacerbations are defined as 3 symptom-defined exacerbations per year or 2 per year if defined by the need for therapy with corticosteroids, antibiotics, or both [67].

What is the underlying pathophysiology?

AECOPD is associated with enhanced upper and lower airway and systemic inflammation. The bronchial mucosa of stable COPD patients have increased numbers of CD8+ lymphocytes and macrophages. In mild AECOPD, eosinophils are increased in the bronchial mucosa and modest elevation of neutrophils, T lymphocytes (CD3), and TNF alpha positive cells has also been reported [62]. With more severe AECOPD, airway neutrophils are increased. Oxidative stress is a key factor in the development of airway inflammation in COPD [61]. Patients with severe exacerbations have augmented large airway interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels and increased oxidative stress as demonstrated by markers such as hydrogen peroxide and 8-isoprostane [66].

How do acute exacerbations affect the course of the disease?

In general, as the severity of the underlying COPD increases, exacerbations become both more severe and more frequent. The quality of life of patients with frequent exacerbations is worse than patients with a history of less frequent exacerbations [68]. Frequent exacerbations have also been linked to a decline in lung function, with studies suggesting that there might be a decline of 7 mL in FEV1 per lower respiratory tract infection per year [59,69] and approxi-mately 8 mL per year in patients with frequent exacerbations as compared to those with sporadic exacerbations [70].

What are the triggers for COPD exacerbation?

Respiratory infections are estimated to trigger approximately two-thirds of exacerbations [62]. Viral and bacterial infections cause most exacerbations. The effect of the infective triggers is to increase inflammation, cause bronchoconstriction, edema, and mucus production, with a resultant increase in dynamic hyperinflation [71]. Thus, any intervention that reduces inflammation in COPD reduces the number and severity of exacerbations, whereas bronchodilators have an impact on exacerbation by their effects on reducing dynamic hyperinflation. The triggers for the one-third of exacerbations not triggered by infection are postulated to be related to other medical conditions, including pulmonary embolism, aspiration, heart failure, and myocardial ischemia [66].

What are the pharmacologic options available for prevention of AECOPD?

In recognition of the importance of preventing COPD exacerbations, the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society [65] have published an evidence-informed clinical guideline specifically examining the prevention of AECOPD, with the goal of assisting clinicians in providing optimal management for COPD patients. The following pharmacologic agents have been recognized as being effective at reducing the frequency of acute exacerbations without any impact on the severity of COPD itself.

Roflumilast

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibition appears to have inflammatory modulating properties in the airways, although the exact mechanism of action is unclear. Some have proposed that it reduces inflammation by inhibiting the breakdown of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate [72]. In 2 large clinical trials [73,74], daily use of a PDE4 inhibitor (roflumilast) showed a significant (15%–18%) reduction in yearly AECOPD incidence (approximate number needed to treat: 4). This benefit was seen in patients with GOLD stage 3–4 disease (FEV1 < 50% predicted) with the chronic bronchitic phenotype and who had experienced at least 1 exacerbation in the previous year.

Importantly, these clinical trials specifically prohibited the use of ICS and LAMAs. Thus, it remains unclear if PDE4 inhibition should be used as an add-on to ICS/LAMA therapy in patients who continue to have frequent AECOPD or whether PDE4 inhibition could be used instead of these standard therapies in patients with well-controlled daily symptoms without ICS or LAMA therapy but who experience frequent exacerbations.

Of note, earlier trials with roflumilast included patients with ICS and LAMA use [73,75]. These trials were focused on FEV1 improvement and found no benefit. It was only in post ad hoc analyses that a reduction in AECOPD in patients with frequent exacerbations was found among those taking roflumilast, regardless of ICS or LAMA use [76]. While roflumilast has documented benefit in improving lung function and reducing the rate of exacerbations, it has not been reported to decrease hospitalizations [64]. This indicates that although the drug reduces the total number of exacerbations, it may not be as useful in preventing episodes of severe exacerbations of COPD.

Although PDE4 inhibitors are easy to administer (a once-daily pill), they are associated with significant GI side effects (diarrhea, nausea, reduced appetite), weight loss, headache, and sleep disturbance [77]. Adverse effects tend to occur early during treatment, are reversible, and lessen over time with treatment [66]. Studies reported an average unexplained weight loss of 2 kg, and monitoring weight during treatment is advised. In addition, it is important to avoid roflumilast in underweight patients. Roflumilast should also be used with caution in depressed patients [65].

N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) reduces the viscosity of respiratory secretions as a result of the cleavage of the disulfide bonds and has been studied as a mucolytic agent to aid in the elimination of respiratory secretions [78]. Oral NAC is quickly absorbed and is rapidly present in an active form in lung tissue and respiratory secretions after ingestion. NAC is well tolerated except for occasional patients with GI adverse effects. The role of NAC in preventing AECOPD has been studied for more than 3 decades [79–81], although the largest clinical trial to date was reported in 2014 [57]. Taken together, the combined data demonstrate a significant reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations associated with the use of NAC when compared with placebo (OR, 0.61; CI, 0.37–0.99). Clinical guidelines suggest that in patients with moderate to severe COPD (FEV1/FVC < 0.7, and FEV1 < 80% predicted) receiving maintenance bronchodilator therapy combined with ICS and history of 2 more exacerbations in the previous 2 years, treatment with oral NAC can be administered to prevent AECOPD.

Macrolides

Continuous prophylactic use of antibiotics in older studies had no effect on the frequency of AECOPD [82,83]. But it is known that macrolide antibiotics have several antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating effects and have been used for many years in the management of other chronic airway disease, including diffuse pan-bronchiolitis and cystic fibrosis [65]. One recent study showed that the use of once-daily, generic azithromycin 5 days/week appeared to have an impact on AECOPD incidence [84]. In this study, AECOPD was reduced from 1.83 to 1.48 per patient-year (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72–0.95: P = 0.01). Azithromycin also prevented severe AECOPD. Greater benefit was obtained with milder forms of the disease and in the elderly. Azithromycin did not appear to provide any benefit in those who continued to smoke (hazard ratio, 0.99) [85]. Other studies have shown that azithromycin was associated with an increased incidence of bacterial resistance and impaired hearing [86]. Overall data from the available clinical trials are robust and demonstrate that regular macrolide therapy definitely reduces the risk of AECOPD. But due to potential side effects macrolide therapy is an option rather than a strong recommendation [65]. The prescribing clinician also needs to consider the potential of prolongation of the QT interval [84].

Immunostimulants

Immunostimulants have also been reported to reduce frequency of AECOPD [87,88]. Bacterial lysates, reconstituted mixtures of bacterial antigens present in the lower airways of COPD patients, act as immuno-stimulants through the induction of cellular maturation, stimulating lymphocyte chemotaxis, and increasing opsonization when administered to individuals with COPD [66]. Studies have demonstrated a reduction in the severe complications of exacerbations and hospital admissions in COPD patients with OM-85, a detoxified oral immunoactive bacterial extract [87,88]. However, most of these trials were conducted prior to the routine use of long-acting bronchodilators and ICS in COPD. A recent study by Braido et al evaluated the efficacy of ismigen, a bacterial lysate, in reducing AECOPD [89] and found no difference in the exacerbation rate between ismigen and placebo or the time to first exacerbation. Additional studies are needed to examine the long-term effects of this therapy in patients receiving currently recommended COPD maintenance therapy [66].

β Blockers

Observational studies of beta-blocker use in preventing AECOPD have yielded encouraging results, with one study showing a reduction in AECOPD risk (incidence risk ratio, 0.73; CI 0.60–0.90) in patients receiving beta blockers versus those not on beta blockers [90]. Based on these findings, a clinical trial investigating the impact of metoprolol on risk of AECOPD is ongoing [91].

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is an independent risk factor for exacerbations [92]. Two small, single-center studies [93,94] have shown that use of lansoprazole decreases the risk and frequency of AECOPD. However, data from the Predicting Outcome using Systemic Markers in Severe Exacerbations of COPD (PROMISE-COPD) study [66], which was a multicenter prospective observational study, suggested that patients with stable COPD receiving a proton pump inhibitor were at high risk of frequent and severe exacerbations [95]. Thus, at this stage, their definitive role needs to be defined, possibly with a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

Case 3

A 65-year-old male with severe COPD (FEV1/FVC 27, FEV1 25% of predicted, residual volume 170% of predicted for his age and height) was seen in the pulmonary clinic. His medications include a LABA/LAMA combination that he uses twice daily as advised. He uses his rescue albuterol inhaler roughly once a week. The patient complains of severe disabling shortness of breath with exertion and severe limitation of his quality of life because of his inability to lead a normal active life. He is on 2 L/min of oxygen at all times. He has received pulmonary rehabilitation in hopes of improving his quality of life but can only climb a flight of stairs before he must stop to rest. He asks about options but does not want to consider lung transplantation today. His most recent chest CT scan demonstrates upper lobe predominant emphysematous changes with no masses or nodules.

What are the patient's options at this time?

Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) attempts to reduce space-occupying severely diseased, hyperexpanded lung, thus allowing the relatively normal adjoining lung parenchyma to expand into the vacated space and function effectively [96].Hence, such therapies are suitable for patients with emphysematous lungs and not those with bronchitic-predominant COPD. LVRS offers a greater chance of improvement in exercise capacity, lung function, quality of life, and dyspnea in the correctly chosen patient population as compared with pharmacologic management alone [97]. However, the procedure is associated with risks, including higher short-term morbidity and mortality [97]. Patients with predominantly upper-lobe emphysema and a low maximal workload after rehabilitation were noted to have lower mortality, a greater probability of improvement in exercise capacity, and a greater probability of improvement in symptoms if they underwent surgery compared to medical therapy alone [97]. On the contrary, patients with predominantly non–upper-lobe emphysema and a high maximal workload after rehabilitation had higher mortality if they underwent surgery compared to receiving medical therapy alone [97]. Thus, a subgroup of patients with homogeneous emphysema symmetrically affecting the upper and lower lobes are considered to be unlikely to benefit from this surgery [97,98].

Valves and other methods of lung volume reduction such as coils, sealants, intrapulmonary vents, and thermal vapor in the bronchi or subsegmental airways have emerged as new techniques for nonsurgical lung volume reduction [99–104]. Endobronchial-valve therapy is associated with improvement in lung function and with clinical benefits that are greatest in the presence of heterogeneous lung involvement. This works by the same principle as with LVRS, by reduction of the most severely diseased lung units, expansion of the more viable, less emphysematous lung results in substantial improvements in lung mechanics [105,106]. The most important complications of this procedure include pneumonia, pneumothorax, hemoptysis and increased frequency of COPD exacerbation in the following thirty days. The fact that high-heterogeneity subgroup had greater improvements in both the FEV1 and distance on the 6-minute walk test than did patients with lower heterogeneity supports the use of quantitative high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) in selecting patients for endobronchial-valve therapy [107].The HRCT scans also help in identifying those with complete fissures; a marker of lack of collateral ventilation (CV+) between different lobes. Presence of CV+ state predicts failure of endobronchial valve and all forms of endoscopic lung volume reduction strategies [108]. Bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA) therapy can potentially work on a subsegmental level and be successful for treatment of emphysema with lack of intact fissures on CT scans. Other methods that have the potential to be effective in those with collateral ventilation would be endoscopic coil therapy and polymeric lung volume reduction [106,109].Unfortunately, there are no randomized controlled trial data demonstrating clinically meaningful improvement following coil therapy or polymeric lung volume reduction in this CV+ patient population. Vapor therapy is perhaps the only technique that has been found to be effective in upper lobe predominant emphysema even with CV+ status [108].

Our patient has evidence of air trapping and emphysema based on a high residual volume. A CT scan of the chest can determine the nature of the emphysema (heterogeneous versus homogenous) and based on these findings, further determination of the best strategy for lung volume reduction can be made.

Is there a role for long-term oxygen therapy?

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) used for > 15 hours a day is thought to reduce mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and severe resting hypoxemia [110–113].More recent studies have failed to show similar beneficial effects of LTOT. A recent study examined the effects of LTOT in randomized fashion and determined that supplemental oxygen for patients with stable COPD and resting or exercise-induced moderate desaturation did not affect the time to death or first hospitalization, time to first COPD exacerbation, time to first hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation, the rate of all hospitalizations, the rate of all COPD exacerbations, or changes in measures of quality of life, depression, anxiety, or functional status [114].

Our patient is currently on long-term oxygen therapy and in spite of some uncertainty as to its benefit, it is prudent to order oxygen therapy until further clarification is available.

What is the role of pulmonary rehabilitation?

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an established treatment for patients with chronic lung disease [115]. Benefits include improvement in exercise tolerance, symptoms, and quality of life, with a reduction in the use of health care resources [116].A Spanish population-based cohort study that looked at the influence of regular physical activity on COPD showed that patients who reported low, moderate, or high physical activity had a lower risk of COPD admissions and all-cause mortality than patients with very low physical activity after adjusting for all confounders [117].

As previously mentioned, patients in GOLD categories B, C, and D should be offered pulmonary rehabilitation as part of their treatment [7]. The ideal patient is one who is not too sick to undergo rehabilitation and is motivated to his or her quality of life.

What is the current scope of lung transplantation in the management of severe COPD?

There is a indisputable role for lung transplantation in end-stage COPD. However, lung transplantation does not benefit all COPD patients. There is a subset of patients for whom the treatment provides a survival benefit. It has been reported that 79% of patients with an FEV1 < 16% predicted will survive at least 1 year additional after transplant, but only 11% of patients with an FEV1 > 25% will do so [118]. The pre-transplant BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction/FEV1, dyspnea, and exercise capacity) index score is used to identify the patients who will benefit from lung transplantation [119,120]. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates identify the following patient characteristics [121]:

- The disease is progressive, despite maximal treatment including medication, pulmonary rehabilitation, and oxygen therapy

- The patient is not a candidate for endoscopic or surgical LVRS

- BODE index of 5 to 6

- The partial pressure of carbon dioxide is greater than 50 mm Hg or 6.6kPa and/or partial pressure of oxygen is less than 60 mm Hg or 8kPa

- FEV1 of 25% predicted

The perioperative mortality of lung transplantation surgery has been reduced to less than 10%. Risk of complications from surgery in the perioperative period, such as bronchial dehiscence, infectious complications, and acute rejection, have also been reduced but do occur. Chronic allograft dysfunction and the risk of lung cancer in cases of single lung transplant should be discussed with the patient before surgery [122].

How can we incorporate palliative care into the management plan for patients with COPD?

Among patients with end-stage COPD on home oxygen therapy who have required mechanical ventilation for an exacerbation, only 55% are alive at 1 year [123]. COPD patients at high risk of death within the next year of life as well as patients with refractory symptoms and unmet needs are candidates for early palliative care. Palliative care and palliative care specialists can aid in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life among these patients and their family members and is recommended by multiple international societies for patients with advanced COPD [124,125]. In spite of these recommendations, the utilization of palliative care resources has been dismally low [126,127]. Improving physician-patient communication regarding palliative services and patients’ unmet care needs will help ensure that COPD patients receive adequate palliative care services at the appropriate time.

Conclusion

COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and represents a significant economic burden for both individuals and society. The goals in COPD management are to provide symptom relief, improve the quality of life, preserve lung function, and reduce the frequency of exacerbations and mortality. COPD management is guided by disease severity that is measured using the GOLD multimodal staging system and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Several classes of medication are available for treatment, and a step-wise approach should be applied in building an effective pharmacologic regimen. In addition to pharmacologic therapies, nonpharmacologic therapies, including smoking cessation, vaccinations, proper nutrition, and maintaining physical activity, are an important part of long-term management. Those who continue to be symptomatic despite appropriate maximal therapy may be candidates for lung volume reduction. Palliative care services for COPD patients, which can aid in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life, should not be overlooked.

Corresponding author: Abhishek Biswas, MD, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Rm. M452, University of Florida, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Segreti A, Stirpe E, Rogliani P, Cazzola M. Defining phenotypes in COPD: an aid to personalized healthcare. Mol Diagn Ther 2014;18:381–8.

2. Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:598–604.

3. Aubier M, Marthan R, Berger P, et al. [COPD and inflammation: statement from a French expert group: inflammation and remodelling mechanisms]. Rev Mal Respir 2010;27:1254–66.

4. Wang ZL. Evolving role of systemic inflammation in comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:3467–78.

5. Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50.

6. Miniño AM, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2011;59:1–126.

7. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD 2017. Accessed at www.goldcopd.org.

8. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54.

9. Wadbo M, Löfdahl CG, Larsson K, et al. Effects of formoterol and ipratropium bromide in COPD: a 3-month placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J 2002;20:1138–46.

10. Ram FS, Sestini P. Regular inhaled short acting beta2 agonists for the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2003;58:580–4.

11. Colice GL. Nebulized bronchodilators for outpatient management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 1996;100(1A):11S–8S.

12. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a combination of ipratropium and albuterol is more effective than either agent alone. An 85-day multicenter trial. COMBIVENT Inhalation Aerosol Study Group. Chest 1994;105:1411–9.

13. Friedman M, Serby CW, Menjoge SS, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a combination of ipratropium plus albuterol compared with ipratropium alone and albuterol alone in COPD. Chest 1999;115:635–41.

14. Cook D, Guyatt G, Wong E, et al. Regular versus as-needed short-acting inhaled beta-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:85–90.

15. Wilchesky M, Ernst P, Brophy JM, et al. Bronchodilator use and the risk of arrhythmia in COPD: part 2: reassessment in the larger Quebec cohort. Chest 2012;142:305–11.

16. Scott VL, Frazee LA. Retrospective comparison of nebulized levalbuterol and albuterol for adverse events in patients with acute airflow obstruction. Am J Ther 2003;10:341–7.

17. Wong CS, Pavord ID, Williams J, et al. Bronchodilator, cardiovascular, and hypokalaemic effects of fenoterol, salbutamol, and terbutaline in asthma. Lancet 1990;336:1396–9.

18. Cole JM, Sheehan AH, Jordan JK. Concomitant use of ipratropium and tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Pharmacother 2012;46:1717–21.

19. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011;155 :179–91.

20. Pearlman DS, Chervinsky P, LaForce C, et al. A comparison of salmeterol with albuterol in the treatment of mild-to-moderate asthma. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1420–5.

21. Takahashi T, Belvisi MG, Patel H, et al. Effect of Ba 679 BR, a novel long-acting anticholinergic agent, on cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig and human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150(6 Pt 1):1640–5.

22. Donohue JF, Fogarty C, Lötvall J, et al. Once-daily bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: indacaterol versus tiotropium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:155–62.

23. Koch A, Pizzichini E, Hamilton A, et al. Lung function efficacy and symptomatic benefit of olodaterol once daily delivered via Respimat versus placebo and formoterol twice daily in patients with GOLD 2-4 COPD: results from two replicate 48-week studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:697–714.

24. Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775–89.

25. Hanania NA, Feldman G, Zachgo W, et al. The efficacy and safety of the novel long-acting β2 agonist vilanterol in patients with COPD: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Chest 2012;142:119–27.

26. Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543–54.

27. Decramer ML, Chapman KR, Dahl R, et al. Once-daily indacaterol versus tiotropium for patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (INVIGORATE): a randomised, blinded, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:524–33.

28. Jones PW, Singh D, Bateman ED, et al. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily aclidinium bromide in COPD patients: the ATTAIN study. Eur Respir J 2012;40:830–6.

29. D’Urzo A, Ferguson GT, van Noord JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily NVA237 in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: the GLOW1 trial. Respir Res 2011;12:156.

30. Antoniu SA. UPLIFT Study: the effects of long-term therapy with inhaled tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evaluation of: Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543–54. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009;10:719–22.

31. Nelson HS, Gross NJ, Levine B, et al. Cardiac safety profile of nebulized formoterol in adults with COPD: a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double- blind, double-dummy, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Clin Ther 2007;29:2167–78.

32. Gershon A, Croxford R, Calzavara A, et al. Cardiovascular safety of inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1175–85.

33. Aljaafareh A, Valle JR, Lin YL, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events after initiation of long-acting bronchodilators in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease: A population-based study. SAGE Open Med 2016;4:2050312116671337.

34. O’Connor AB. Tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360:185–6.

35. Kesten S, Jara M, Wentworth C, Lanes S. Pooled clinical trial analysis of tiotropium safety. Chest 2006;130:1695–703.

36. Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D, et al. Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1491–501.

37. Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1093–103.

38. Chong J, Karner C, Poole P. Tiotropium versus long-acting beta-agonists for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(9):CD009157.

39. Gan WQ, Man SF, Sin DD. Effects of inhaled corticosteroids on sputum cell counts in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2005;5:3.

40. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(7):CD002991.

41. Roland NJ, Bhalla RK, Earis J. The local side effects of inhaled corticosteroids: current understanding and review of the literature. Chest 2004;126:213–9.

42. Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:2407–16.

43. Lee SY, Park HY, Kim EK, et al. Combination therapy of inhaled steroids and long-acting beta2-agonists in asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:2797–803.

44. Postma DS, Rabe KF. The asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1241–9.

45. Farne HA, Cates CJ. Long-acting beta2-agonist in addition to tiotropium versus either tiotropium or long-acting beta2-agonist alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD008989.

46. Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2222–34.

47. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, et al. Tiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:545–55.

48. Welte T, Miravitlles M, Hernandez P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:741–50.

49. Gallelli L, Falcone D, Cannataro R, et al. Theophylline action on primary human bronchial epithelial cells under proinflammatory stimuli and steroidal drugs: a therapeutic rationale approach. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:265–72.

50. Paloucek FP, Rodvold KA. Evaluation of theophylline overdoses and toxicities. Ann Emerg Med 1988;17:135–44.

51. Ram FS, Jones PW, Castro AA, et al. Oral theophylline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002(4):CD003902.

52. Murciano D, Auclair MH, Pariente R, Aubier M. A randomized, controlled trial of theophylline in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 1989;320:1521–5.

53. Devereux G, Cotton S, Barnes P, et al. Use of low-dose oral theophylline as an adjunct to inhaled corticosteroids in preventing exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:267.

54. Walters JA, Walters EH, Wood-Baker R. Oral corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(3):CD005374.

55. Horita N, Miyazawa N, Morita S, et al. Evidence suggesting that oral corticosteroids increase mortality in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 2014;15:37.

56. Poole P, Chong J, Cates CJ. Mucolytic agents versus placebo for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(7):CD001287.

57. Zheng JP, Wen FQ, Bai CX, et al. Twice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:187–94.

58. Seemungal TA, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, et al. Long-term erythromycin therapy is associated with decreased chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:1139–47.

59. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM, Prewitt LM. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:823– 32.

60. Güell R, Casan P, Belda J, et al. Long-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation of COPD: a randomized trial. Chest 2000;117:976–83.

61. Wedzicha JA, Singh R, Mackay AJ. Acute COPD exacerbations. Clin Chest Med 2014;35:157–63.

62. Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TAR. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet 2007;370:786–96.

63. Spencer S, Calverley PMA, Burge PS, Jones PW. Impact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPD. Eur Respir J 2004;23:698–702.

64. Blanchette CM, Gross NJ, Altman P. Rising costs of COPD and the potential for maintenance therapy to slow the trend. Am Health Drug Benef 2014;7:98.

65. Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest 2015;147:894–942.

66. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. Respirology 2017;22:575–601.

67. Wedzicha JA, Brill SE, Allinson JP, Donaldson GC. Mechanisms and impact of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Med 2013;11:181.

68. Seemungal TAR, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1418–22.

69. Kanner RE, Anthonisen NR, Connett JE. Lower respiratory illnesses promote FEV1 decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:358–64.

70. Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002;57:847–52.

71. Papi A, Bellettato CM, Braccioni F, et al. Infections and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1114–21.

72. Rabe KF. Update on roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Pharmacol 2011;163:53–67.

73. Calverley PMA, Rabe KF, Goehring U-M, et al. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2009;374:685–94.

74. Fabbri LM, Calverley PMA, Izquierdo-Alonso JL, et al. Roflumilast in moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with longacting bronchodilators: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2009;374:695–703.

75. Lee S, Hui DSC, Mahayiddin AA, et al. Roflumilast in Asian patients with COPD: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Respirology 2011;16:1249–57.

76. Calverley PM, Martinez FJ, Fabbri LM, et al. Does roflumilast decrease exacerbations in severe COPD patients not controlled by inhaled combination therapy? The REACT study protocol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012;7:375–82.

77. Chong J, Leung B, Poole P. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(11):CD002309.

78. Sheffner AL, Medler EM, Jacobs LW, Sarett HP. The in vitro reduction in viscosity of human tracheobronchial secretions by acetylcysteine. Am Rev Respir Dis 1964;90:721–9.

79. Boman G, Bäcker U, Larsson S, et al. Oral acetylcysteine reduces exacerbation rate in chronic bronchitis: report of a trial organized by the Swedish Society for Pulmonary Diseases. Eur J Respir Dis 1983;64:405–15.

80. Grassi C, Morandini GC. A controlled trial of intermittent oral acetylcysteine in the long-term treatment of chronic bronchitis. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1976;9:393–6.

81. Hansen NCG, Skriver A, Brorsen-Riis L, et al. Orally administered N-acetylcysteine may improve general well-being in patients with mild chronic bronchitis. Respir Med 1994;88:531–5.

82. Francis RS, Spicer CC. Chemotherapy in chronic bronchitis: Influence of daily penicillin and tetracycline on exacerbations and their cost: A report to the research committee of the British Tuberculosis Association by Their Chronic Bronchitis Subcommittee. BMJ 1960;1:297–303.

83. Francis RS, May JR, Spicer CC. Chemotherapy of bronchitis. BMJ 1961;2:979.

84. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2011;365:689–98.

85. Han MK, Tayob N, Murray S, et al. Predictors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation reduction in response to daily azithromycin therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1503–8.

86. Uzun S, Djamin RS, Kluytmans JAJW, et al. Azithromycin maintenance treatment in patients with frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COLUMBUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:361–8.

87. Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ernst P, et al. Effects of an immunostimulating agent on acute exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:1719–24.

88. Jing LI. Protective effect of a bacterial extract against acute exacerbation in patients with chronic bronchitis accompanied by chronic obstructive pulmonary. Age 2004;67:0–05.

89. Braido F, Tarantini F, Ghiglione V, et al. Bacterial lysate in the prevention of acute exacerbation of COPD and in respiratory recurrent infections. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007;2:335.

90. Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL, et al. β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations. Thorax 2016;71:8–14.

91. Bhatt SP, Connett JE, Voelker H, et al. β-Blockers for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (βLOCK COPD): a randomised controlled study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012292.

92. Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1128–8.

93. Sasaki T, Nakayama K, Yasuda H, et al. A randomized, single-blind study of lansoprazole for the prevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1453–7.

94. Xiong W, Zhang Qs, Zhao W, et al. A 12-month follow-up study on the preventive effect of oral lansoprazole on acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Exper Pathol 2016;97:107–13.

95. Baumeler L, Papakonstantinou E, Milenkovic B, et al. Therapy with proton-pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease does not reduce the risk for severe exacerbations in COPD. Respirology 2016;21:883–90.

96 Sabanathan A, Sabanathan S, Shah R, Richardson J. Lung volume reduction surgery for emphysema: a review. J Cardiovasc Surg 1998;39:237.

97. Group NETTR. Patients at high risk of death after lung-volume–reduction surgery. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1075–83.

98. Group NETTR. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume–reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059–73.

99. Decker MR, Leverson GE, Jaoude WA, Maloney JD. Lung volume reduction surgery since the National Emphysema Treatment Trial: study of Society of Thoracic Surgeons database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:2651–8.

100. Deslée G, Mal H, Dutau H, et al. Lung volume reduction coil treatment vs usual care in patients with severe emphysema: the REVOLENS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:175–84.

101. Hartman JE, Klooster K, Gortzak K, et al. Long-term follow-up after bronchoscopic lung volume reduction treatment with coils in patients with severe emphysema. Respirology 2015;20:319–26.

102. Snell GI, Hopkins P, Westall G, et al. A feasibility and safety study of bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation: a novel emphysema therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1993–8.

103. Ingenito EP, Berger RL, Henderson AC, et al. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction using tissue engineering principles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:771–8.

104. Ingenito EP, Loring SH, Moy ML, et al. Comparison of physiological and radiological screening for lung volume reduction surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1068–73.

105. Shah P, Slebos D, Cardoso P, et al. Bronchoscopic lung-volume reduction with Exhale airway stents for emphysema (EASE trial): randomised, sham-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2011;378:997–1005.

106. Sciurba FC, Ernst A, Herth FJ, et al. A randomized study of endobronchial valves for advanced emphysema. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1233–44.

107. Wan IY, Toma TP, Geddes DM, et al. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction for end-stage emphysema: report on the first 98 patients. Chest 2006;129:518–26.

108. Gompelmann D, Eberhardt R, Schuhmann M, et al. Lung volume reduction with vapor ablation in the presence of incomplete fissures: 12-month results from the STEP-UP randomized controlled study. Respiration 2016;92:397–403.

109. Come CE, Kramer MR, Dransfield MT, et al. A randomised trial of lung sealant versus medical therapy for advanced emphysema. Eur Respir J 2015;46:651–62.

110. Group NOTT. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1980;93:391–8.

111. Council M. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema: Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet 1981;1:681–6.

112. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:179–91.

113. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:347–65.

114. Group L-TOTTR. A randomized trial of long-term oxygen for COPD with moderate desaturation. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1617–27.

115. McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(2):CD003793.

116. Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, et al. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:362–8.

117. Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, et al. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax 2006;61:772–8.

118. Thabut G, Ravaud P, Christie JD, et al. Determinants of the survival benefit of lung transplantation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:1156–63.

119. Lahzami S, Bridevaux PO, Soccal PM, et al. Survival impact of lung transplantation for COPD. Eur Respir J 2010;36:74–80.

120. Cerón Navarro J, de Aguiar Quevedo K, Ansótegui Barrera E, et al. Functional outcomes after lung transplant in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Bronconeumol 2015;51:109–14.

121. Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014--an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:1–15.

122. Minai OA, Shah S, Mazzone P, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma after lung transplantation: characteristics and outcomes. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1404–9.

123. Hajizadeh N, Goldfeld K, Crothers K. What happens to patients with COPD with long-term oxygen treatment who receive mechanical ventilation for COPD exacerbation? A 1-year retrospective follow- up study. Thorax 2015;70:294–6.

124. Siouta N, van Beek K, Preston N, et al. Towards integration of palliative care in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review of European guidelines and pathways. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:18.

125. Celli BR, MacNee W; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–46.

126. Szekendi MK, Vaughn J, Lal A, et al. The prevalence of inpatients at thirty-three U.S. hospitals appropriate for and receiving referral to palliative care. J Palliat Med 2016;19:360–72.

127. Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, et al. Use of palliative care in patients with end-stage COPD and receiving home oxygen: national trends and barriers to care in the United States. Chest 2017;151:41–6.

From the Division of Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective:To review the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Methods: Review of the peer-reviewed literature.

- Results: Effective management of stable COPD requires the physician to apply a stepwise intensification of therapy depending on patient symptoms and functional reserve. Bronchodilators are the cornerstone of management. In addition to pharmacologic therapies, nonpharmacologic therapies, including smoking cessation, vaccinations, proper nutrition, and maintaining physical activity, are an important part of long-term management. Those who continue to be symptomatic despite appropriate maximal therapy may be candidates for lung volume reduction. Palliative care services for COPD patients, which can aid in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life, should not be overlooked.