User login

Almost one-third of Syrian refugees in U.S. met PTSD criteria

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly one-third of adult Syrian civil war refugees who have resettled in the Detroit area meet diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, according to preliminary results of an ongoing study presented by Arash Javanbakht, MD, at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

That’s comparable to PTSD rates documented in Vietnam War combat veterans.

“Based on these data, mental health care for Syrian refugees resettling in the U.S. is highly needed,” he observed.

Michigan has a large population of Syrian war refugees. All who settle in southeastern Michigan undergo an initial health examination at Arab American and Chaldean Council primary care clinics staffed by bilingual teams. More than 90% of eligible adult refugees who have been invited to join Dr. Javanbakht’s mental health screening study have opted to participate. This extraordinarily high recruitment rate suggests that the findings are generalizable to the broader Syrian refugee community throughout the United States in his view.

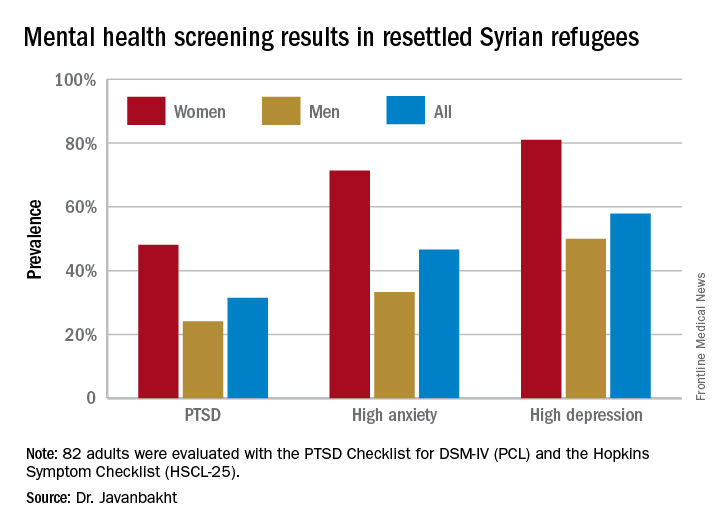

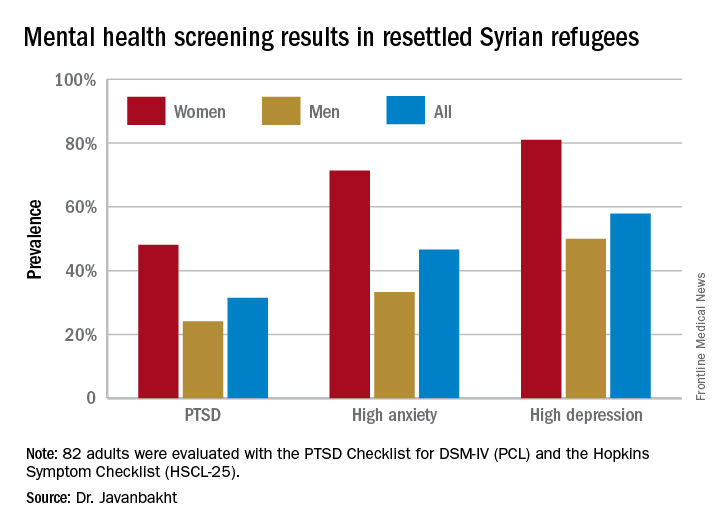

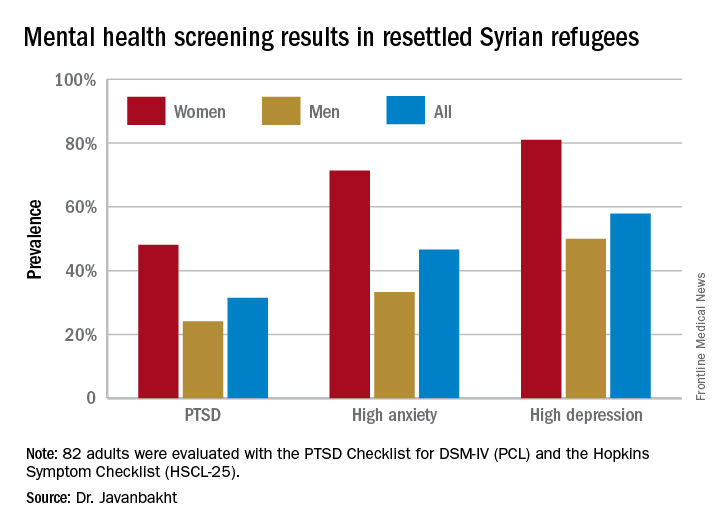

The screening tools employed in the study are the PTSD Checklist, DSM-IV version (PCL), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25), which contains 10 anxiety questions and 15 depression questions.

Of the first 82 adult Syrian refugees evaluated, 26 (31.5%) were diagnosed as having PTSD on the basis of a PCL total score of 40 or more plus fulfillment of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the disorder. In fact, this subgroup had a mean PCL score of 62.3. The prevalence of PTSD was twice as great in women, compared with men (see graphic).

Clinically impactful anxiety symptoms as defined by an HSCL-25 anxiety score greater than 1.79 was present in 38 refugees (47%), and clinically meaningful depressive symptoms were present in 47 (58%).

Anxiety, depression, and PTSD all were tightly correlated, complicating the clinical challenges, the psychiatrist noted.

Enrollment in the study is ongoing, but a first pass examination of a participant population that’s now twice the size of that in his presentation at the conference continues to show similar results, according to Dr. Javanbakht.

Dr. Javanbakht reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which was funded by the state of Michigan and the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly one-third of adult Syrian civil war refugees who have resettled in the Detroit area meet diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, according to preliminary results of an ongoing study presented by Arash Javanbakht, MD, at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

That’s comparable to PTSD rates documented in Vietnam War combat veterans.

“Based on these data, mental health care for Syrian refugees resettling in the U.S. is highly needed,” he observed.

Michigan has a large population of Syrian war refugees. All who settle in southeastern Michigan undergo an initial health examination at Arab American and Chaldean Council primary care clinics staffed by bilingual teams. More than 90% of eligible adult refugees who have been invited to join Dr. Javanbakht’s mental health screening study have opted to participate. This extraordinarily high recruitment rate suggests that the findings are generalizable to the broader Syrian refugee community throughout the United States in his view.

The screening tools employed in the study are the PTSD Checklist, DSM-IV version (PCL), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25), which contains 10 anxiety questions and 15 depression questions.

Of the first 82 adult Syrian refugees evaluated, 26 (31.5%) were diagnosed as having PTSD on the basis of a PCL total score of 40 or more plus fulfillment of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the disorder. In fact, this subgroup had a mean PCL score of 62.3. The prevalence of PTSD was twice as great in women, compared with men (see graphic).

Clinically impactful anxiety symptoms as defined by an HSCL-25 anxiety score greater than 1.79 was present in 38 refugees (47%), and clinically meaningful depressive symptoms were present in 47 (58%).

Anxiety, depression, and PTSD all were tightly correlated, complicating the clinical challenges, the psychiatrist noted.

Enrollment in the study is ongoing, but a first pass examination of a participant population that’s now twice the size of that in his presentation at the conference continues to show similar results, according to Dr. Javanbakht.

Dr. Javanbakht reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which was funded by the state of Michigan and the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly one-third of adult Syrian civil war refugees who have resettled in the Detroit area meet diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, according to preliminary results of an ongoing study presented by Arash Javanbakht, MD, at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

That’s comparable to PTSD rates documented in Vietnam War combat veterans.

“Based on these data, mental health care for Syrian refugees resettling in the U.S. is highly needed,” he observed.

Michigan has a large population of Syrian war refugees. All who settle in southeastern Michigan undergo an initial health examination at Arab American and Chaldean Council primary care clinics staffed by bilingual teams. More than 90% of eligible adult refugees who have been invited to join Dr. Javanbakht’s mental health screening study have opted to participate. This extraordinarily high recruitment rate suggests that the findings are generalizable to the broader Syrian refugee community throughout the United States in his view.

The screening tools employed in the study are the PTSD Checklist, DSM-IV version (PCL), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25), which contains 10 anxiety questions and 15 depression questions.

Of the first 82 adult Syrian refugees evaluated, 26 (31.5%) were diagnosed as having PTSD on the basis of a PCL total score of 40 or more plus fulfillment of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the disorder. In fact, this subgroup had a mean PCL score of 62.3. The prevalence of PTSD was twice as great in women, compared with men (see graphic).

Clinically impactful anxiety symptoms as defined by an HSCL-25 anxiety score greater than 1.79 was present in 38 refugees (47%), and clinically meaningful depressive symptoms were present in 47 (58%).

Anxiety, depression, and PTSD all were tightly correlated, complicating the clinical challenges, the psychiatrist noted.

Enrollment in the study is ongoing, but a first pass examination of a participant population that’s now twice the size of that in his presentation at the conference continues to show similar results, according to Dr. Javanbakht.

Dr. Javanbakht reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which was funded by the state of Michigan and the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: One-third of adult Syrian war refugees who have resettled in Michigan have posttraumatic stress disorder.

Data source: This ongoing cross-sectional study initially screened 82 adult Syrian civil war refugees for PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

Disclosures: This ongoing study is funded by the state of Michigan and the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

New approval lights up gliomas to aid resection

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Gleolan) to help visualize gliomas during surgery and allow for more complete resection.

Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride lights up the tumor so surgeons can distinguish it from healthy tissue. Patients take the drug orally – 20 mg/kg – approximately 3 hours before anesthesia. Glioma cells take it up and convert it to the fluorescent chemical protoporphyrin IX. When illuminated under blue light, protoporphyrin in the tumor glows an intense red, while normal brain tissue appears blue, enabling “the surgeon to see the tumor more clearly during brain surgery and to remove it more accurately, sparing healthy brain tissue,” according to information from NX Development Corp, which markets Gleolan.

In a phase III trial of 349 patients with suspected malignant glioma amenable to complete resection, a contrast-enhanced tumor was resected in 64% of patients in the aminolevulinic acid (ALA) arm, versus 38 % of patients in the control-group, who had conventional resection under white light (P less than .001); 20.5 % of ALA patients versus 11 % patients in the control arm were alive at 6 months without progression.

FDA officials noted that there’s a risk of false negatives and positives with ALA, and that “an increase in the extent of resection might increase the risk of serious neurologic deficits in the short term.”

Side effects in preapproval studies included fever, hypotension, nausea, and vomiting in more than 1% percent of patients within a week of surgery. Adverse events included chills, abnormal liver function tests, and diarrhea in less than 1% of patients within 6 weeks of surgery.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Gleolan) to help visualize gliomas during surgery and allow for more complete resection.

Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride lights up the tumor so surgeons can distinguish it from healthy tissue. Patients take the drug orally – 20 mg/kg – approximately 3 hours before anesthesia. Glioma cells take it up and convert it to the fluorescent chemical protoporphyrin IX. When illuminated under blue light, protoporphyrin in the tumor glows an intense red, while normal brain tissue appears blue, enabling “the surgeon to see the tumor more clearly during brain surgery and to remove it more accurately, sparing healthy brain tissue,” according to information from NX Development Corp, which markets Gleolan.

In a phase III trial of 349 patients with suspected malignant glioma amenable to complete resection, a contrast-enhanced tumor was resected in 64% of patients in the aminolevulinic acid (ALA) arm, versus 38 % of patients in the control-group, who had conventional resection under white light (P less than .001); 20.5 % of ALA patients versus 11 % patients in the control arm were alive at 6 months without progression.

FDA officials noted that there’s a risk of false negatives and positives with ALA, and that “an increase in the extent of resection might increase the risk of serious neurologic deficits in the short term.”

Side effects in preapproval studies included fever, hypotension, nausea, and vomiting in more than 1% percent of patients within a week of surgery. Adverse events included chills, abnormal liver function tests, and diarrhea in less than 1% of patients within 6 weeks of surgery.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Gleolan) to help visualize gliomas during surgery and allow for more complete resection.

Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride lights up the tumor so surgeons can distinguish it from healthy tissue. Patients take the drug orally – 20 mg/kg – approximately 3 hours before anesthesia. Glioma cells take it up and convert it to the fluorescent chemical protoporphyrin IX. When illuminated under blue light, protoporphyrin in the tumor glows an intense red, while normal brain tissue appears blue, enabling “the surgeon to see the tumor more clearly during brain surgery and to remove it more accurately, sparing healthy brain tissue,” according to information from NX Development Corp, which markets Gleolan.

In a phase III trial of 349 patients with suspected malignant glioma amenable to complete resection, a contrast-enhanced tumor was resected in 64% of patients in the aminolevulinic acid (ALA) arm, versus 38 % of patients in the control-group, who had conventional resection under white light (P less than .001); 20.5 % of ALA patients versus 11 % patients in the control arm were alive at 6 months without progression.

FDA officials noted that there’s a risk of false negatives and positives with ALA, and that “an increase in the extent of resection might increase the risk of serious neurologic deficits in the short term.”

Side effects in preapproval studies included fever, hypotension, nausea, and vomiting in more than 1% percent of patients within a week of surgery. Adverse events included chills, abnormal liver function tests, and diarrhea in less than 1% of patients within 6 weeks of surgery.

Extended-release Aristada OK’d for 2-month dosing for schizophrenia

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded labeling of extended-release aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada) to allow for administration once every 2 months at a dose of 1,064 mg, for schizophrenia.

Depending on patient needs, treatment now can be initiated at a dose of 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; 882 mg administered every 6 weeks; or 1,064 mg administered every 2 months. For patients who have never taken aripiprazole, “establish tolerability with oral aripiprazole prior to initiating treatment with Aristada. Due to the half-life of oral aripiprazole, it may take up to 2 weeks to fully assess tolerability,” according to the updated labeling. The new 2-month option is expected to be available in mid-June.

Another extended-release IM aripiprazole option, (Abilify Maintena, Otsuka) is approved only for once-a-month injection.

Approval of the bimonthly dose was based on pharmacokinetic data showing long-term therapeutic aripiprazole plasma levels. Labeling did not note whether the higher dose is associated with increased adverse events. Aristada originally was approved in 2015.

As with other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada labeling notes that the drug should not be used in elderly patients with dementia because of the increased risk of fatal strokes. The labeling also warns of the possibility of tardive dyskinesia, metabolic derangements, compulsive behaviors, agranulocytosis, and other risks.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded labeling of extended-release aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada) to allow for administration once every 2 months at a dose of 1,064 mg, for schizophrenia.

Depending on patient needs, treatment now can be initiated at a dose of 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; 882 mg administered every 6 weeks; or 1,064 mg administered every 2 months. For patients who have never taken aripiprazole, “establish tolerability with oral aripiprazole prior to initiating treatment with Aristada. Due to the half-life of oral aripiprazole, it may take up to 2 weeks to fully assess tolerability,” according to the updated labeling. The new 2-month option is expected to be available in mid-June.

Another extended-release IM aripiprazole option, (Abilify Maintena, Otsuka) is approved only for once-a-month injection.

Approval of the bimonthly dose was based on pharmacokinetic data showing long-term therapeutic aripiprazole plasma levels. Labeling did not note whether the higher dose is associated with increased adverse events. Aristada originally was approved in 2015.

As with other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada labeling notes that the drug should not be used in elderly patients with dementia because of the increased risk of fatal strokes. The labeling also warns of the possibility of tardive dyskinesia, metabolic derangements, compulsive behaviors, agranulocytosis, and other risks.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded labeling of extended-release aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada) to allow for administration once every 2 months at a dose of 1,064 mg, for schizophrenia.

Depending on patient needs, treatment now can be initiated at a dose of 441 mg, 662 mg, or 882 mg administered monthly; 882 mg administered every 6 weeks; or 1,064 mg administered every 2 months. For patients who have never taken aripiprazole, “establish tolerability with oral aripiprazole prior to initiating treatment with Aristada. Due to the half-life of oral aripiprazole, it may take up to 2 weeks to fully assess tolerability,” according to the updated labeling. The new 2-month option is expected to be available in mid-June.

Another extended-release IM aripiprazole option, (Abilify Maintena, Otsuka) is approved only for once-a-month injection.

Approval of the bimonthly dose was based on pharmacokinetic data showing long-term therapeutic aripiprazole plasma levels. Labeling did not note whether the higher dose is associated with increased adverse events. Aristada originally was approved in 2015.

As with other atypical antipsychotics, Aristada labeling notes that the drug should not be used in elderly patients with dementia because of the increased risk of fatal strokes. The labeling also warns of the possibility of tardive dyskinesia, metabolic derangements, compulsive behaviors, agranulocytosis, and other risks.

Early literacy assessment tool shows promise for screening preschool children

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-item Early Literary Assessment Tool (ELSAT) used during regular pediatrician appointments in the first 4 years of life has shown promise in screening preschool children for delayed literacy skills that could result in later reading problems, based on a pilot study conducted in the preschool setting.

ELSAT “can be completed by a clinician [in the primary care setting] in less than a minute and can be incorporated into the Reach Out and Read intervention. An important next step in our research is to study the feasibility of the ELSAT within primary care visits and obtain feedback from clinicians about the ease of administration and value to their practice,” said Sai N. Iyer, MD, a developmental-behavioral pediatric fellow at the University of California, San Diego.

The initial 40-item ELSAT addressed three key domains of early literacy skills: knowledge and awareness of printed words, knowledge of letters, and recognition of word sounds. The observational study had two phases. ELSAT was developed and refined in the pilot phase, with validation against three aforementioned reference measures in the validation phase. The process whittled the test down to 10 items, with the same three domains represented. Comparisons were between the individual measures and a composite of the three.

The 10-item ELSAT correlated with each of the reference measures and with the composite of the three measures of early literacy (Pearson’s correlation, 810; P less than .01; Cronbach’s alpha [a measure of internal consistency] of .852). A cut-off ELSAT score of less than or equal to 5 predicted a “below average” score in any of the three reference measures and identified delayed literacy with a sensitivity of 92% and an acceptable specificity of 64%, Dr. Iyer explained during her presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

Language skills acquired during the first few years of life in the home and preschool settings lay the path for the development of more sophisticated reading skills, including decoding and comprehension beginning in grade 1. “Research has shown that about 40% of children enter kindergarten behind their peers in important early literacy skills. This gap widens with time, and the cost of catching them up far exceeds the cost of screening and early intervention. Many studies have demonstrated that effective early interventions improve the long-term outcomes for children who are at risk for later reading failure. Children who are reading at a below grade level by 4th grade are unlikely to catch up. Low levels of literacy have an impact on later educational and employment opportunities and set up a cycle of social and economic disadvantage that can have transgenerational effects,” Dr. Iyer said.

While parent-completed questionnaires are a convenient way to perform developmental screening, they are limited by the health literacy of the parents and other factors. Furthermore, while some preschools perform assessments, not all children attend preschools. This prompted Dr. Iyer and colleagues to think about developing a more objective screening strategy, with which a clinician could do the brief assessment. “All preschool children do see their pediatrician/primary care provider for vaccinations that are required before kindergarten. This makes the primary care setting an ideal opportunity to screen these children,” said Dr. Iyer.

During the question-and-answer session, an attendee described the data concerning the dichotomy in the test results between the public and private preschools as “some of the most impressive and depressing I’ve seen in this area.”

In a later interview, Dr. Iyer commented that, while the results in the study were not entirely new or surprising, “it was remarkable that we were able to demonstrate such significant differences in a sample of children enrolled in a high-quality preschool. Without specific screening and intervention, these early literacy delays would go unrecognized and increase the risk of poor academic outcomes for these high-risk children. The children were all in some type of preschool environment. Throughout the country, there are many children from low-income families who are not able to access preschool education. Although we did not test these children in our study, it is likely that the gaps between these children and their more advantaged peers are even higher. The pediatrician’s office may be the only place for these children to receive early literacy screening and anticipatory guidance on reading readiness.”

The sponsor of the study was the University of California, San Diego. The study was funded by the 2015 Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award and by Reach Out and Read. Dr. Iyer had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-item Early Literary Assessment Tool (ELSAT) used during regular pediatrician appointments in the first 4 years of life has shown promise in screening preschool children for delayed literacy skills that could result in later reading problems, based on a pilot study conducted in the preschool setting.

ELSAT “can be completed by a clinician [in the primary care setting] in less than a minute and can be incorporated into the Reach Out and Read intervention. An important next step in our research is to study the feasibility of the ELSAT within primary care visits and obtain feedback from clinicians about the ease of administration and value to their practice,” said Sai N. Iyer, MD, a developmental-behavioral pediatric fellow at the University of California, San Diego.

The initial 40-item ELSAT addressed three key domains of early literacy skills: knowledge and awareness of printed words, knowledge of letters, and recognition of word sounds. The observational study had two phases. ELSAT was developed and refined in the pilot phase, with validation against three aforementioned reference measures in the validation phase. The process whittled the test down to 10 items, with the same three domains represented. Comparisons were between the individual measures and a composite of the three.

The 10-item ELSAT correlated with each of the reference measures and with the composite of the three measures of early literacy (Pearson’s correlation, 810; P less than .01; Cronbach’s alpha [a measure of internal consistency] of .852). A cut-off ELSAT score of less than or equal to 5 predicted a “below average” score in any of the three reference measures and identified delayed literacy with a sensitivity of 92% and an acceptable specificity of 64%, Dr. Iyer explained during her presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

Language skills acquired during the first few years of life in the home and preschool settings lay the path for the development of more sophisticated reading skills, including decoding and comprehension beginning in grade 1. “Research has shown that about 40% of children enter kindergarten behind their peers in important early literacy skills. This gap widens with time, and the cost of catching them up far exceeds the cost of screening and early intervention. Many studies have demonstrated that effective early interventions improve the long-term outcomes for children who are at risk for later reading failure. Children who are reading at a below grade level by 4th grade are unlikely to catch up. Low levels of literacy have an impact on later educational and employment opportunities and set up a cycle of social and economic disadvantage that can have transgenerational effects,” Dr. Iyer said.

While parent-completed questionnaires are a convenient way to perform developmental screening, they are limited by the health literacy of the parents and other factors. Furthermore, while some preschools perform assessments, not all children attend preschools. This prompted Dr. Iyer and colleagues to think about developing a more objective screening strategy, with which a clinician could do the brief assessment. “All preschool children do see their pediatrician/primary care provider for vaccinations that are required before kindergarten. This makes the primary care setting an ideal opportunity to screen these children,” said Dr. Iyer.

During the question-and-answer session, an attendee described the data concerning the dichotomy in the test results between the public and private preschools as “some of the most impressive and depressing I’ve seen in this area.”

In a later interview, Dr. Iyer commented that, while the results in the study were not entirely new or surprising, “it was remarkable that we were able to demonstrate such significant differences in a sample of children enrolled in a high-quality preschool. Without specific screening and intervention, these early literacy delays would go unrecognized and increase the risk of poor academic outcomes for these high-risk children. The children were all in some type of preschool environment. Throughout the country, there are many children from low-income families who are not able to access preschool education. Although we did not test these children in our study, it is likely that the gaps between these children and their more advantaged peers are even higher. The pediatrician’s office may be the only place for these children to receive early literacy screening and anticipatory guidance on reading readiness.”

The sponsor of the study was the University of California, San Diego. The study was funded by the 2015 Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award and by Reach Out and Read. Dr. Iyer had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-item Early Literary Assessment Tool (ELSAT) used during regular pediatrician appointments in the first 4 years of life has shown promise in screening preschool children for delayed literacy skills that could result in later reading problems, based on a pilot study conducted in the preschool setting.

ELSAT “can be completed by a clinician [in the primary care setting] in less than a minute and can be incorporated into the Reach Out and Read intervention. An important next step in our research is to study the feasibility of the ELSAT within primary care visits and obtain feedback from clinicians about the ease of administration and value to their practice,” said Sai N. Iyer, MD, a developmental-behavioral pediatric fellow at the University of California, San Diego.

The initial 40-item ELSAT addressed three key domains of early literacy skills: knowledge and awareness of printed words, knowledge of letters, and recognition of word sounds. The observational study had two phases. ELSAT was developed and refined in the pilot phase, with validation against three aforementioned reference measures in the validation phase. The process whittled the test down to 10 items, with the same three domains represented. Comparisons were between the individual measures and a composite of the three.

The 10-item ELSAT correlated with each of the reference measures and with the composite of the three measures of early literacy (Pearson’s correlation, 810; P less than .01; Cronbach’s alpha [a measure of internal consistency] of .852). A cut-off ELSAT score of less than or equal to 5 predicted a “below average” score in any of the three reference measures and identified delayed literacy with a sensitivity of 92% and an acceptable specificity of 64%, Dr. Iyer explained during her presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

Language skills acquired during the first few years of life in the home and preschool settings lay the path for the development of more sophisticated reading skills, including decoding and comprehension beginning in grade 1. “Research has shown that about 40% of children enter kindergarten behind their peers in important early literacy skills. This gap widens with time, and the cost of catching them up far exceeds the cost of screening and early intervention. Many studies have demonstrated that effective early interventions improve the long-term outcomes for children who are at risk for later reading failure. Children who are reading at a below grade level by 4th grade are unlikely to catch up. Low levels of literacy have an impact on later educational and employment opportunities and set up a cycle of social and economic disadvantage that can have transgenerational effects,” Dr. Iyer said.

While parent-completed questionnaires are a convenient way to perform developmental screening, they are limited by the health literacy of the parents and other factors. Furthermore, while some preschools perform assessments, not all children attend preschools. This prompted Dr. Iyer and colleagues to think about developing a more objective screening strategy, with which a clinician could do the brief assessment. “All preschool children do see their pediatrician/primary care provider for vaccinations that are required before kindergarten. This makes the primary care setting an ideal opportunity to screen these children,” said Dr. Iyer.

During the question-and-answer session, an attendee described the data concerning the dichotomy in the test results between the public and private preschools as “some of the most impressive and depressing I’ve seen in this area.”

In a later interview, Dr. Iyer commented that, while the results in the study were not entirely new or surprising, “it was remarkable that we were able to demonstrate such significant differences in a sample of children enrolled in a high-quality preschool. Without specific screening and intervention, these early literacy delays would go unrecognized and increase the risk of poor academic outcomes for these high-risk children. The children were all in some type of preschool environment. Throughout the country, there are many children from low-income families who are not able to access preschool education. Although we did not test these children in our study, it is likely that the gaps between these children and their more advantaged peers are even higher. The pediatrician’s office may be the only place for these children to receive early literacy screening and anticipatory guidance on reading readiness.”

The sponsor of the study was the University of California, San Diego. The study was funded by the 2015 Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award and by Reach Out and Read. Dr. Iyer had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

AT PAS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 10-item ELSAT correlated with each of the reference measures and with the composite of the three measures of early literacy (Pearson’s correlation, 810; P less than .01; Cronbach’s alpha [a measure of internal consistency] of .852).

Data source: An observational study of 54-month-old children in five public preschools (n = 61) and two private preschools (n = 35) in San Diego.

Disclosures: The sponsor of the study was the University of California, San Diego. The study was funded by the 2015 Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award and by Reach Out and Read. Dr. Iyer had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

‘How could he?’

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The headline in a Portland, Maine, newspaper read, “Standish man sentenced to serve 15 years in prison for death of his 3-month-old son” (Edward Murphy, May 23, 2017). I suspect that many of the folks who read the story under the headline feel that the sentence was too light. Others are asking themselves how a 21-year-old man could beat a fragile 5-pound infant to death. What kind of evil monster is this guy?

However, even with the snatches of information provided in the 500-word newspaper story, the unfortunate scenario makes sense, and the child’s death is a tragic culmination of a series of events that shouldn’t surprise any pediatrician. It turns out the infant was a twin who, with his sister, had been born at 30 weeks’ gestation. He had spent a month or more in the hospital, and his sister was still in neonatal ICU at the time of his death. While it is unclear from the newspaper article whether the twins’ parents were married, they were living in a house with eight other adults and some other children. The mother was out of the home working while the father was left to care for his son.

I am sure that the neonatologists and social workers at the hospital where the twins were born were aware of at least some of the red flags that waved over this unfortunate family. I also am confident that they did what they could to assure this infant a safe home environment when it was time for his discharge from the NICU. However, risks factors may have been missed that now seem obvious in retrospect. We should all realize by now from our experience with domestic terrorism that simply appearing on someone’s radar doesn’t mean that preemptive action can or will be taken. Short of keeping the parents of high-risk neonates under constant surveillance for a year or 2, there are few other workable options to prevent every tragedy like this one.

This case is another example of the erosive power of a baby’s cry. Most pediatricians have developed a filtering mechanism that allows us to function in a cacophonous environment dominated by a screaming infant. However, even adults without this young father’s deprived background crack under the stress when they are confined in a space with a crying child. The risk of decompensation is compounded when the adult also feels some responsibility for the child’s welfare. I don’t think we can condone what the father did in this tragic scenario, but we can certainly understand how the dominoes fell.

We are all potential child abusers. When faced with the right, or I guess the wrong, set of circumstances we might lash out to stop the crying. Luckily, most of us are several body lengths from the end of that rope.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Not better late ...

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

You all know the statistics or at least have a sense of the scope of the problem. While 85% of mothers in this country intend to breastfeed their infants exclusively for at least 3 months, only slightly more than 30% achieve this goal. Among the dozens of reasons for this unfortunate shortfall is what some experts view as inadequate support by primary care physicians and their offices. In the May 2017 Pediatrics, two members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding offer a clinical report that hopes to remedy this situation (“The Breastfeeding-Friendly Pediatric Office Practice.” Pediatrics. 2017 May. 139[5]:e20170647). It is a document that begins with an excellent review of the background and epidemiology of breastfeeding in the United States and a survey of the current initiatives targeted at improving our dismal performance. What follows is an extensive set of 19 evidence-based recommendations for the pediatric outpatient practice that hopes to “meet or exceed the AAP recommendations.”

A large part of the problem is the failure of the point person in the office, usually the receptionist, to realize that a tearful call from a new mother who is struggling with breastfeeding is an emergency, one that demands a response in minutes … not hours. Even when the call is eventually routed to someone with a compassionate voice who will call back with the right answers, if that process takes just an hour or two, that is enough time for a mother with a screaming and hungry newborn to reach for a bottle of formula.

I urge you to read this exhaustive clinical report in Pediatrics because it is very likely you will come across some things that you can include in your office practice to make it more breastfeeding friendly. However, Even if you and your staff have the right advice, this is not a situation of “better late than never.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

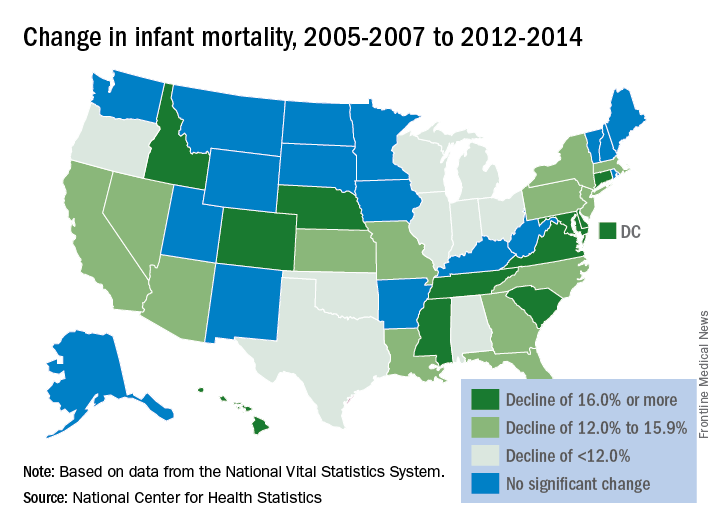

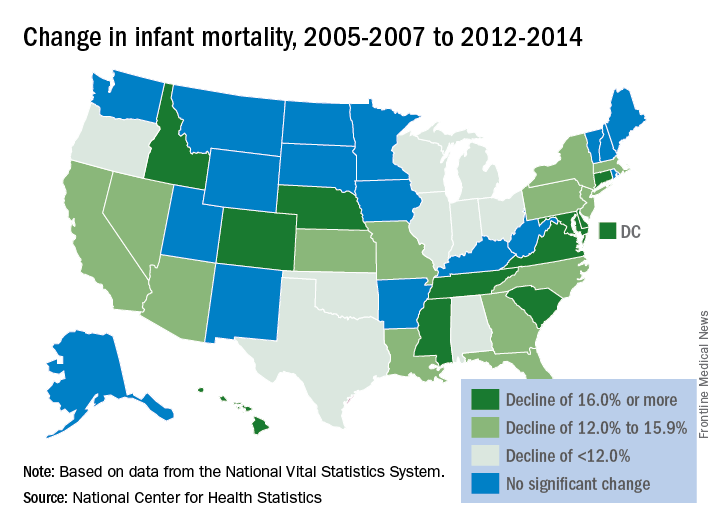

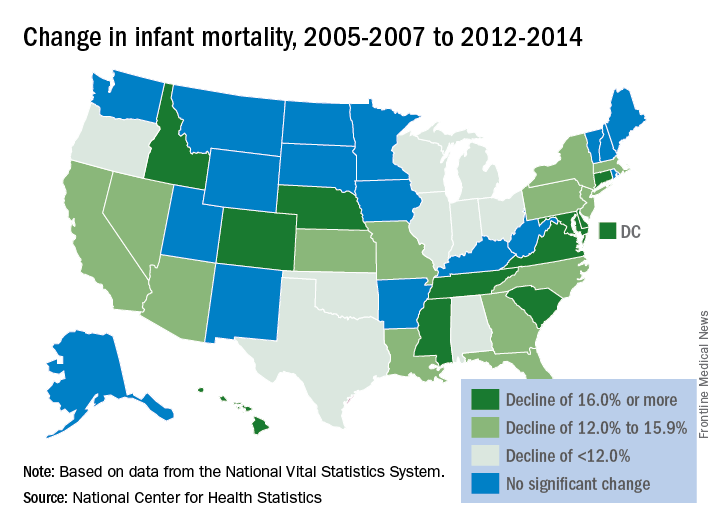

Infant mortality down in most states

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Infant mortality in the United States was down by 15% from 2005 to 2014, with 33 states reporting significant declines, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The overall rate for 2014 was 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with 6.84 per 1,000 in 2005. The data for individual states were grouped into 3-year periods, so between the periods of 2005-2007 and 2012-2014, there were 33 states (and the District of Columbia) with a significant decline and 17 states with no significant change. Three states – Maine, South Dakota, and Utah – had increased infant mortality, but the changes did not reach significance, the NCHS reported, using data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Should convicted sex offender get penile prosthetic implant?

SAN DIEGO – Should a man with a distant history of pedophilia be allowed to get a penile prosthetic implant to treat his erectile dysfunction? Mental health professionals at a Veterans Affairs medical center in San Diego recently faced this question and decided the risk was too great. They denied his request.

“This kind of dilemma occurs throughout all health systems, and it’s very challenging. It obviously puts the physician in a very ethically challenging situation,” said Kristin Beizai, MD, a psychiatrist and coauthor of a case report presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Yash B. Joshi, MD, PhD, and Dr. Beizai, both psychiatrists at the University of California, San Diego, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, reported the penile prosthetic implant case in a poster at APA.

According to them, a married veteran sought treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED) from VA hospital urologists after oral treatment had failed. The elderly man, who had been imprisoned for 3 years some 25-30 years previously, sought a penile prosthetic implant – an alternative to treatments for ED when drugs have failed. Other options include self-injections and vacuum devices.

Men with the implants trigger erections by squeezing a pump in the scrotum that allows fluid to flow from a reservoir into the cylinder.

The man had been imprisoned in his 40s for 3 years because of a single incident of sexually abusing a toddler. According to the case report, his primary care doctors previously had offered him ED treatments “without acknowledging this history in their clinical-decision making process.”

A psychologist determined the man to be at low risk of committing a sexual offense again and cleared him for an implant. But his urologists requested an ethics consultation, which was provided by a team that included representatives from the fields of psychiatry, internal medicine, nursing, and social work.

“The ethics team determined that the most appropriate course of action hinged on a thorough and individualized risk-benefit assessment to determine if providing the treatment was ethically justifiable,” Dr. Beizai said in an interview.

An on-site psychologist and an outside expert evaluated the patient using a tool known as the Violence Risk Assessment Instrument–Sexual and determined the man was at moderate to severe risk of committing a sexual offense again.

“It was also discovered that the patient never completed treatment for pedophilia in the community as previously recommended,” the psychiatrists reported. “He was offered a plan for reevaluation and rehabilitation by subspecialists but declined this option.”

The man subsequently died of natural causes.

Dr. Beizai said those kinds of cases present numerous challenges. “This case involves surgery/urology, but this is an issue with primary care as well, and they likely do not have the time, resources, or protocol to address fully, particularly when legal information may be withheld and there are confidentiality issues.”

In regard to a risk-benefit analysis, she said, “a general mental health practitioner may not be comfortable completing this kind of assessment, and there may be an indication to refer to a forensic psychiatrist or psychologist. But this can be an expensive and scarce resource.”

There’s also the potential for political storms if the news gets out that a convicted sex offender received ED treatment. News reports in the mid-2000s about this kind of care persuaded several states to ban government payments for ED treatment for convicted sex offenders, and Medicaid funding was eliminated.

Two researchers who study pedophilia said in an interview that these decisions are far from simple and must take several factors into account.

Fred S. Berlin, MD, PhD, director of the Sexual Behavior Consultation Unit, and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said a sexual offense background isn’t necessarily enough of a reason to deny ED treatment to a patient. Important factors for decision making, he said, include the nature of the previous offenses (such as whether they involved penile penetration, or the use of drugs or alcohol) and the state of an offender’s current relationship.

He added that it’s important to understand that the lack of functioning genitals isn’t a barrier to sexual abuse. “There shouldn’t be a narrow focus on the capacity of the penis to have an erection,” he said.

Treatment for ED in convicted sex offenders can be helpful in some cases, said Richard B. Krueger, MD, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and medical director of the Sexual Behavior Clinic at New York State Psychiatric Institute. “The general sense is that it would be a benefit to enable an appropriate, peer-related relationship with a spouse, significant other, or adults,” Dr. Krueger said.

Red flags regarding ED treatment in sex offenders, he said, include high scores on predictive tests, a history of extreme sadism or sociopathy, and challenges regarding monitoring of the offender.

Dr. Beizai, Dr. Joshi, Dr. Krueger, and Dr. Berlin reported no relevant disclosures.

[polldaddy:9767052]

SAN DIEGO – Should a man with a distant history of pedophilia be allowed to get a penile prosthetic implant to treat his erectile dysfunction? Mental health professionals at a Veterans Affairs medical center in San Diego recently faced this question and decided the risk was too great. They denied his request.

“This kind of dilemma occurs throughout all health systems, and it’s very challenging. It obviously puts the physician in a very ethically challenging situation,” said Kristin Beizai, MD, a psychiatrist and coauthor of a case report presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Yash B. Joshi, MD, PhD, and Dr. Beizai, both psychiatrists at the University of California, San Diego, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, reported the penile prosthetic implant case in a poster at APA.

According to them, a married veteran sought treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED) from VA hospital urologists after oral treatment had failed. The elderly man, who had been imprisoned for 3 years some 25-30 years previously, sought a penile prosthetic implant – an alternative to treatments for ED when drugs have failed. Other options include self-injections and vacuum devices.

Men with the implants trigger erections by squeezing a pump in the scrotum that allows fluid to flow from a reservoir into the cylinder.

The man had been imprisoned in his 40s for 3 years because of a single incident of sexually abusing a toddler. According to the case report, his primary care doctors previously had offered him ED treatments “without acknowledging this history in their clinical-decision making process.”

A psychologist determined the man to be at low risk of committing a sexual offense again and cleared him for an implant. But his urologists requested an ethics consultation, which was provided by a team that included representatives from the fields of psychiatry, internal medicine, nursing, and social work.

“The ethics team determined that the most appropriate course of action hinged on a thorough and individualized risk-benefit assessment to determine if providing the treatment was ethically justifiable,” Dr. Beizai said in an interview.

An on-site psychologist and an outside expert evaluated the patient using a tool known as the Violence Risk Assessment Instrument–Sexual and determined the man was at moderate to severe risk of committing a sexual offense again.

“It was also discovered that the patient never completed treatment for pedophilia in the community as previously recommended,” the psychiatrists reported. “He was offered a plan for reevaluation and rehabilitation by subspecialists but declined this option.”

The man subsequently died of natural causes.

Dr. Beizai said those kinds of cases present numerous challenges. “This case involves surgery/urology, but this is an issue with primary care as well, and they likely do not have the time, resources, or protocol to address fully, particularly when legal information may be withheld and there are confidentiality issues.”

In regard to a risk-benefit analysis, she said, “a general mental health practitioner may not be comfortable completing this kind of assessment, and there may be an indication to refer to a forensic psychiatrist or psychologist. But this can be an expensive and scarce resource.”

There’s also the potential for political storms if the news gets out that a convicted sex offender received ED treatment. News reports in the mid-2000s about this kind of care persuaded several states to ban government payments for ED treatment for convicted sex offenders, and Medicaid funding was eliminated.

Two researchers who study pedophilia said in an interview that these decisions are far from simple and must take several factors into account.

Fred S. Berlin, MD, PhD, director of the Sexual Behavior Consultation Unit, and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said a sexual offense background isn’t necessarily enough of a reason to deny ED treatment to a patient. Important factors for decision making, he said, include the nature of the previous offenses (such as whether they involved penile penetration, or the use of drugs or alcohol) and the state of an offender’s current relationship.

He added that it’s important to understand that the lack of functioning genitals isn’t a barrier to sexual abuse. “There shouldn’t be a narrow focus on the capacity of the penis to have an erection,” he said.

Treatment for ED in convicted sex offenders can be helpful in some cases, said Richard B. Krueger, MD, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and medical director of the Sexual Behavior Clinic at New York State Psychiatric Institute. “The general sense is that it would be a benefit to enable an appropriate, peer-related relationship with a spouse, significant other, or adults,” Dr. Krueger said.

Red flags regarding ED treatment in sex offenders, he said, include high scores on predictive tests, a history of extreme sadism or sociopathy, and challenges regarding monitoring of the offender.

Dr. Beizai, Dr. Joshi, Dr. Krueger, and Dr. Berlin reported no relevant disclosures.

[polldaddy:9767052]

SAN DIEGO – Should a man with a distant history of pedophilia be allowed to get a penile prosthetic implant to treat his erectile dysfunction? Mental health professionals at a Veterans Affairs medical center in San Diego recently faced this question and decided the risk was too great. They denied his request.

“This kind of dilemma occurs throughout all health systems, and it’s very challenging. It obviously puts the physician in a very ethically challenging situation,” said Kristin Beizai, MD, a psychiatrist and coauthor of a case report presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Yash B. Joshi, MD, PhD, and Dr. Beizai, both psychiatrists at the University of California, San Diego, and the VA San Diego Healthcare System, reported the penile prosthetic implant case in a poster at APA.

According to them, a married veteran sought treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED) from VA hospital urologists after oral treatment had failed. The elderly man, who had been imprisoned for 3 years some 25-30 years previously, sought a penile prosthetic implant – an alternative to treatments for ED when drugs have failed. Other options include self-injections and vacuum devices.

Men with the implants trigger erections by squeezing a pump in the scrotum that allows fluid to flow from a reservoir into the cylinder.

The man had been imprisoned in his 40s for 3 years because of a single incident of sexually abusing a toddler. According to the case report, his primary care doctors previously had offered him ED treatments “without acknowledging this history in their clinical-decision making process.”

A psychologist determined the man to be at low risk of committing a sexual offense again and cleared him for an implant. But his urologists requested an ethics consultation, which was provided by a team that included representatives from the fields of psychiatry, internal medicine, nursing, and social work.

“The ethics team determined that the most appropriate course of action hinged on a thorough and individualized risk-benefit assessment to determine if providing the treatment was ethically justifiable,” Dr. Beizai said in an interview.

An on-site psychologist and an outside expert evaluated the patient using a tool known as the Violence Risk Assessment Instrument–Sexual and determined the man was at moderate to severe risk of committing a sexual offense again.

“It was also discovered that the patient never completed treatment for pedophilia in the community as previously recommended,” the psychiatrists reported. “He was offered a plan for reevaluation and rehabilitation by subspecialists but declined this option.”

The man subsequently died of natural causes.

Dr. Beizai said those kinds of cases present numerous challenges. “This case involves surgery/urology, but this is an issue with primary care as well, and they likely do not have the time, resources, or protocol to address fully, particularly when legal information may be withheld and there are confidentiality issues.”

In regard to a risk-benefit analysis, she said, “a general mental health practitioner may not be comfortable completing this kind of assessment, and there may be an indication to refer to a forensic psychiatrist or psychologist. But this can be an expensive and scarce resource.”

There’s also the potential for political storms if the news gets out that a convicted sex offender received ED treatment. News reports in the mid-2000s about this kind of care persuaded several states to ban government payments for ED treatment for convicted sex offenders, and Medicaid funding was eliminated.

Two researchers who study pedophilia said in an interview that these decisions are far from simple and must take several factors into account.

Fred S. Berlin, MD, PhD, director of the Sexual Behavior Consultation Unit, and associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said a sexual offense background isn’t necessarily enough of a reason to deny ED treatment to a patient. Important factors for decision making, he said, include the nature of the previous offenses (such as whether they involved penile penetration, or the use of drugs or alcohol) and the state of an offender’s current relationship.

He added that it’s important to understand that the lack of functioning genitals isn’t a barrier to sexual abuse. “There shouldn’t be a narrow focus on the capacity of the penis to have an erection,” he said.

Treatment for ED in convicted sex offenders can be helpful in some cases, said Richard B. Krueger, MD, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and medical director of the Sexual Behavior Clinic at New York State Psychiatric Institute. “The general sense is that it would be a benefit to enable an appropriate, peer-related relationship with a spouse, significant other, or adults,” Dr. Krueger said.

Red flags regarding ED treatment in sex offenders, he said, include high scores on predictive tests, a history of extreme sadism or sociopathy, and challenges regarding monitoring of the offender.

Dr. Beizai, Dr. Joshi, Dr. Krueger, and Dr. Berlin reported no relevant disclosures.

[polldaddy:9767052]

AT APA

Crossing the personal quality chasm: QI enthusiast to QI leader

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Eric Howell, MD, MHM, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

For Eric Howell, MD, MHM, the journey to becoming a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, past president of SHM, and director of SHM’s Leadership Academies commenced with a major quality improvement (QI) challenge.

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center was struggling with throughput from the emergency department when Dr. Howell began practicing there in the early days of hospital medicine. “The ED said the medicine service was too slow, and the hospitalists said, ‘We’re working as fast as we can,’ ” Dr. Howell recalled of his real-world introduction to implementation science. “So, I took on triage oversight in 2000 and began streamlining flow.”

With a growing reputation for finding solutions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions, Dr. Howell joined the Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions (Project BOOST) project team in 2007 to codevelop one of SHM’s most successful programs. He humbly attributes some of this success to luck. “I happened to be at the right place at the right time. There was a problem, opportunity knocked, and I opened the door,” he said.

After some reflection, he pinpoints more tangible factors – a gift for innovative thinking and finding options that unify, rather than polarize, people and departments.

“I always ensure a solution makes the pie bigger, so that everyone benefits from it,” he said. “I don’t approach a problem like a sporting event, where one group wins and another loses.”

Dr. Howell says that an inclusive mindset is an important characteristic for anyone on a QI track because “it encourages buy-in from everyone who is impacted by a problem, and their investment in making the outcome successful.”

Skill development in areas such as leadership principles and processes such as lean will benefit those on a QI pathway, but finding the right mentors is just as critical. Dr. Howell looked to multiple people from diverse backgrounds, none of which included QI, to “help me move my skill set forward,” he said. “A clinical educator helped me to interact with other people, learn to facilitate an educational initiative, and lead people to change.”

Another mentor, he recalled, was an engineer who helped him figure out how to measure the success of his projects. And a third mentor cleared the pathway of obstructions, providing access to the people who would make his projects successful.

Being able to pivot is also important, Dr. Howell said. “Whether it is looking at data or the people you need to approach to solve a problem, be able to change your approach. Flip-flopping is a good thing in QI, because you’re always adjusting your tactics based on new information.”

Today, as SHM’s senior physician advisor to its Center for Quality Improvement, Dr. Howell holds multiple roles within the Johns Hopkins system and has received numerous awards for excellence in teaching and practice. The core principles that he started with on the path remain the same: “Be humble,” he said, “and give away credit. We are often collaborating with other professionals, so shining a light on the great work that they do will make projects more successful and improve the likelihood that they will want to collaborate with you in the future.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

FDA asks drug maker to shelve Opana ER

The Food and Drug Administration has asked Endo Pharmaceuticals to voluntarily remove its opioid pain medication, reformulated Opana ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride), from the market in the United States, citing the potential for its abuse as a concern.

“We are facing an opioid epidemic – a public health crisis, and we must take all necessary steps to reduce the scope of opioid misuse and abuse,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a June 8 press release . “We will continue to take regulatory steps when we see situations where an opioid product’s risks outweigh its benefits, not only for its intended patient population but also in regard to its potential for misuse and abuse.”

Opana ER was first approved in 2006 for the management of moderate to severe pain when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. It was reformulated in 2012, with the intent of making it “resistant to physical and chemical manipulation for abuse by snorting or injecting,” according to the FDA release.

The Food and Drug Administration has asked Endo Pharmaceuticals to voluntarily remove its opioid pain medication, reformulated Opana ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride), from the market in the United States, citing the potential for its abuse as a concern.

“We are facing an opioid epidemic – a public health crisis, and we must take all necessary steps to reduce the scope of opioid misuse and abuse,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a June 8 press release . “We will continue to take regulatory steps when we see situations where an opioid product’s risks outweigh its benefits, not only for its intended patient population but also in regard to its potential for misuse and abuse.”

Opana ER was first approved in 2006 for the management of moderate to severe pain when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. It was reformulated in 2012, with the intent of making it “resistant to physical and chemical manipulation for abuse by snorting or injecting,” according to the FDA release.

The Food and Drug Administration has asked Endo Pharmaceuticals to voluntarily remove its opioid pain medication, reformulated Opana ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride), from the market in the United States, citing the potential for its abuse as a concern.

“We are facing an opioid epidemic – a public health crisis, and we must take all necessary steps to reduce the scope of opioid misuse and abuse,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a June 8 press release . “We will continue to take regulatory steps when we see situations where an opioid product’s risks outweigh its benefits, not only for its intended patient population but also in regard to its potential for misuse and abuse.”