User login

Biosimilar rituximab approved in Europe

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has approved the Sandoz biosimilar rituximab (Rixathon®) for use in the European Economic Area.

Rixathon is approved for all indications of the reference medicine, MabThera®, including follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and immunologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and microscopic polyangiitis.

This approval allows Rixathon to be marketed in the member states of the European Union and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, members of the European Free Trade Association.

The approval “represents a big win for patients in Europe with blood cancers or immunological diseases,” according to Carol Lynch, global head of Biopharmaceuticals at Sandoz.

“Rixathon will be one of the 5 major launches we plan in the next 4 years,” she said.

Earlier in the year, the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use had recommended marketing authorization for Rixathon.

The EC based its approval on a comprehensive development program generating analytical, preclinical, and clinical data. Clinical studies included ASSIST-RA and ASSIST-FL.

ASSIST-RA demonstrated that the biosimilar product has equivalent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles to the reference medicine, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, tolerability, or immunogenicity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

ASSIST-FL was a phase 3 study confirming efficacy and safety. The study met its primary endpoint of equivalence in overall response rate between the biosimilar product and the reference medicine after 6 months.

ASSIST-FL also confirmed the comparable safety profiles of the 2 medicines.

Sandoz is a division of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. MabThera is a registered trademark of F. Hoffmann-La-Roche AG.

Another Sandoz biosimilar rituximab has been approved in the EU as Riximyo® under a duplicate marketing authorization. ![]()

Rest dyspnea dims as acute heart failure treatment target

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PARIS – During the most recent pharmaceutical generation, drug development for heart failure largely focused on acute heart failure, and specifically on patients with rest dyspnea as the primary manifestation of their acute heart failure decompensation events.

That has now changed, agreed heart failure experts as they debated the upshot of sobering results from two neutral trials that failed to show a midterm mortality benefit in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure who underwent aggressive management of their congestion using 2 days of intravenous treatment with either of two potent vasodilating drugs. Results first reported in November 2016 failed to show a survival benefit from ularitide in the 2,100-patient TRUE-AHF (Efficacy and Safety of Ularitide for the Treatment of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure) trial (N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376[20]:1956-64). And results reported at a meeting of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC failed to show a survival benefit from serelaxin in more than 6,500 acute heart failure patients in the RELAX-AHF-2 (Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Serelaxin When Added to Standard Therapy in AHF) trial.

The failure of a 2-day infusion of serelaxin to produce a significant reduction in cardiovascular death in RELAX-AHF-2 was especially surprising because the predecessor trial, RELAX-AHF, which randomized only 1,160 patients and used a surrogate endpoint of dyspnea improvement, had shown significant benefit that hinted more clinically meaningful benefits might also result from serelaxin treatment (Lancet. 2013 Jan 5;381[9860]:29-39). The disappointing serelaxin and ularitide results also culminate a series of studies using several different agents or procedures to treat acute decompensated heart failure patients that all failed to produce a reduction in deaths.

“This is a sea change; make no mistake. We will need a more targeted, selective approach. It was always a daunting proposition to believe that short-term infusion could have an effect 6 months later. We were misled by the analogy [of acute heart failure] to acute coronary syndrome,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor of medicine at the University of Zürich.

The right time to intervene

Meeting attendees offered several hypotheses to explain why the acute ularitide and serelaxin trials both failed to show a mortality benefit, with timing of treatment the most common denominator.

Acute heart failure “is an event, not a disease,” declared Milton Packer, MD, lead investigator of TRUE-AHF, during a session devoted to vasodilator treatment of acute heart failure. Acute heart failure decompensations “are fluctuations in a chronic disease. It doesn’t matter what you do during the episode – it matters what you do between acute episodes. We focus all our attention on which vasodilator and which dose of Lasix [furosemide], but we send patients home on inadequate chronic therapy. It doesn’t matter what you do to the dyspnea, the shortness of breath will get better. Do we need a new drug that makes dyspnea go away an hour sooner and doesn’t cost a fortune? What really matters is what patients do between acute episodes and how to prevent them, ” said Dr. Packer, distinguished scholar in cardiovascular science at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

Dr. Packer strongly urged clinicians to put heart failure patients on the full regimen of guideline-directed drugs and at full dosages, a step he thinks would go a long way toward preventing a majority of decompensation episodes. “Chronic heart failure treatment has improved dramatically, but implementation is abysmal,” he said.

Of course, at this phase of their disease heart failure patients are usually at home, which more or less demands that the treatments they take are oral or at least delivered by subcutaneous injection.

“We’ve had a mismatch of candidate drugs, which have mostly been IV infusions, with a clinical setting where an IV infusion is challenging to use.”

“We are killing good drugs by the way we’re testing them,” commented Javed Butler, MD, who bemoaned the ignominious outcome of serelaxin treatment in RELAX-AHF-2. “The available data show it makes no sense to treat for just 2 days. We should take true worsening heart failure patients, those who are truly failing standard treatment, and look at new chronic oral therapies to try on them.” Oral drugs similar to serelaxin and ularitide could be used chronically, suggested Dr. Butler, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) School of Medicine.

Wrong patients with the wrong presentation

Perhaps just as big a flaw of the acute heart failure trials has been their target patient population, patients with rest dyspnea at the time of admission. “Why do we think that dyspnea is a clinically relevant symptom for acute heart failure?” Dr. Packer asked.

Dr. Cleland and his associates analyzed data on 116,752 hospitalizations for acute heart failure in England and Wales during April 2007–March 2013, a database that included more than 90% of hospitals for these regions. “We found that a large proportion of admitted patients did not have breathlessness at rest as their primary reason for seeking hospitalization. For about half the patients, moderate or severe peripheral edema was the main problem,” he reported. Roughly a third of patients had rest dyspnea as their main symptom.

An unadjusted analysis also showed a stronger link between peripheral edema and the rate of mortality during a median follow-up of about a year following hospitalization, compared with rest dyspnea. Compared with the lowest-risk subgroup, the patients with severe peripheral edema (18% of the population) had more than twice the mortality. In contrast, the patients with the most severe rest dyspnea and no evidence at all of peripheral edema, just 6% of the population, had a 50% higher mortality rate than the lowest-risk patients.

”It’s peripheral edema rather than breathlessness that is the important determinant of length of stay and prognosis. The disastrous neutral trials for acute heart failure have all targeted the breathless subset of patients. Maybe a reason for the failures has been that they’ve been treating a problem that does not exist. The trials have looked at the wrong patients,” Dr. Cleland said.

‘We’ve told the wrong story to industry” about the importance of rest dyspnea to acute heart failure patients. “When we say acute heart failure, we mean an ambulance and oxygen and the emergency department and rapid IV treatment. That’s breathlessness. Patients with peripheral edema usually get driven in and walk from the car to a wheelchair and they wait 4 hours to be seen. I think that, following the TRUE-AHF and RELAX-AHF-2 results, we’ll see a radical change.”

But just because the focus should be on peripheral edema rather than dyspnea, that doesn’t mean better drugs aren’t needed, Dr. Cleland added.

“We need better treatments to deal with congestion. Once a patient is congested, we are not very good at getting rid of it. We depend on diuretics, which we don’t use properly. Ultimately I’d like to see agents as adjuncts to diuretics, to produce better kidney function.” But treatments for breathlessness are decent as they now exist: furosemide plus oxygen. When a simple, cheap drug works 80% of the time, it is really hard to improve on that.” The real unmet needs for treating acute decompensated heart failure are patients with rest dyspnea who don’t respond to conventional treatment, and especially patients with gross peripheral edema plus low blood pressure and renal dysfunction for whom no good treatments have been developed, Dr. Cleland said.

Another flaw in the patient selection criteria for the acute heart failure studies has been the focus on patients with elevated blood pressures, the logical target for vasodilator drugs that lower blood pressure, noted Dr. Felker. “But these are the patients at lowest risk. We’ve had a mismatch between the patients with the biggest need and the patients we actually study, which relates to the types of drugs we’ve developed.”

Acute heart failure remains a target

Despite all the talk of refocusing attention on chronic heart failure and peripheral edema, at least one expert remained steadfast in talking up the importance of new acute interventions.

Part of the problem in believing that existing treatments can adequately manage heart failure and prevent acute decompensations is that about 75% of acute heart failure episodes either occur as the first presentation of heart failure, or occur in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a type of heart failure that, until recently, had no chronic drug regimens with widely acknowledged efficacy for HFpEF. (The 2017 U.S. heart failure management guidelines update listed aldosterone receptor antagonists as a class IIb recommendation for treating HFpEF, the first time guidelines have sanctioned a drug class for treating HFpEF [Circulation. 2017 Apr 28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509].)

“For patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, you can give optimal treatments and [decompensations] are prevented,” noted Dr. Mebazaa, a professor of anesthesiology and resuscitation at Lariboisière Hospital in Paris. “But for the huge number of HFpEF patients we have nothing. Acute heart failure will remain prevalent, and we still don’t have the right drugs to use on these patients.”

The TRUE-AHF trial was sponsored by Cardiorentis. RELAX-AHF-2 was sponsored by Novartis. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a speaker on behalf of Novartis, and has been a speaker for or consultant to several companies and was a coinvestigator for TRUE-AHF and received fees from Cardiorentis for his participation. Dr. Packer is a consultant to and stockholder in Cardiorentis and has been a consultant to several other companies. Dr. Felker has been a consultant to Novartis and several other companies and was a coinvestigator on RELAX-AHF-2. Dr. Butler has been a consultant to several companies. Dr. Cleland has received research support from Novartis, and he has been a consultant to and received research support from several other companies. Dr. Mebazaa has received honoraria from Novartis and Cardiorentis as well as from several other companies and was a coinvestigator on TRUE-AHF.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM HEART FAILURE 2017

FDA approves new fluoroquinolone for skin, skin structure infections

The Food and Drug Administration has approved delafloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, according to an agency announcement June 19.

Delafloxacin, which will be marketed by Melinta Therapeutics as Baxdela, was designated a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) and granted fast-track and priority review. These classifications are designed to speed approval of antibacterial products to treat serious or life-threatening infections, according to an FDA statement.

Common adverse events seen with use of delafloxacin included nausea, diarrhea, headache, elevated liver enzymes, and vomiting.

The approval requires Melinta Therapeutics to conduct a 5-year postmarketing surveillance study to look for resistance to delafloxacin; the final report on that study must be submitted by the end of 2022.

The drug was not subject to FDA advisory committee review because its new drug application “did not raise significant safety or efficacy issues that were unexpected” for a drug in its class, according to FDA officials.

For more information see the Drugs@FDA listing for Baxdela.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

The Food and Drug Administration has approved delafloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, according to an agency announcement June 19.

Delafloxacin, which will be marketed by Melinta Therapeutics as Baxdela, was designated a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) and granted fast-track and priority review. These classifications are designed to speed approval of antibacterial products to treat serious or life-threatening infections, according to an FDA statement.

Common adverse events seen with use of delafloxacin included nausea, diarrhea, headache, elevated liver enzymes, and vomiting.

The approval requires Melinta Therapeutics to conduct a 5-year postmarketing surveillance study to look for resistance to delafloxacin; the final report on that study must be submitted by the end of 2022.

The drug was not subject to FDA advisory committee review because its new drug application “did not raise significant safety or efficacy issues that were unexpected” for a drug in its class, according to FDA officials.

For more information see the Drugs@FDA listing for Baxdela.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

The Food and Drug Administration has approved delafloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, according to an agency announcement June 19.

Delafloxacin, which will be marketed by Melinta Therapeutics as Baxdela, was designated a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) and granted fast-track and priority review. These classifications are designed to speed approval of antibacterial products to treat serious or life-threatening infections, according to an FDA statement.

Common adverse events seen with use of delafloxacin included nausea, diarrhea, headache, elevated liver enzymes, and vomiting.

The approval requires Melinta Therapeutics to conduct a 5-year postmarketing surveillance study to look for resistance to delafloxacin; the final report on that study must be submitted by the end of 2022.

The drug was not subject to FDA advisory committee review because its new drug application “did not raise significant safety or efficacy issues that were unexpected” for a drug in its class, according to FDA officials.

For more information see the Drugs@FDA listing for Baxdela.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

Brexanolone appears effective for severe postpartum depression

A single 60-hour infusion of brexanolone dramatically and rapidly improves severe postpartum depression with minimal adverse effects, a small manufacturer-conducted phase II trial suggests.

Brexanolone is a proprietary formulation of allopregnanolone, the major metabolite of progesterone and a potent modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors that has demonstrated profound benefits for anxiety and depression symptoms in animal models. Plasma levels of allopregnanolone rise to a peak during the third trimester of pregnancy, then abruptly fall after childbirth. “Failure of GABAA receptors to adapt to these changes at parturition has been postulated to have a role in triggering postpartum depression,” said Stephen Kanes, MD, of Sage Therapeutics, Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They assessed the drug’s effects in 21 women hospitalized for severe postpartum depression at 11 U.S. medical centers during a 5-month period. The study participants, who had Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scores of 26 or higher at baseline, randomized to receive a 60-hour infusion of brexanolone (10 patients) or a matching placebo (11 patients) in a double-blind fashion.

The primary outcome measure – mean reduction in HAM-D score at the end of the 60-hour infusion – was 21.0 points with brexanolone, significantly greater than the 8.8 point reduction seen with placebo. Women in the active-treatment group began showing a marked improvement within 24 hours of beginning the infusion, which was maintained throughout the week of treatment, as well as for the succeeding 30 days of follow-up.

Of the 10 patients, 7 receiving brexanolone (70%), compared with only 1 of those receiving placebo (9%), achieved remission of depression (HAM-D score of 7 or less) by the end of treatment. That remission occurred within 24 hours of beginning the infusion in six of the women in the brexanolone group. Moreover, improvement extended beyond the core depressive symptoms, with women in the active-treatment group also showing rapid and marked improvement on Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale scores, the investigators said (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-67369(17)31264-3).

Two women who received brexanolone admitted that, at baseline, they’d had active suicidal ideation with a specific plan and intent. Neither was suicidal after treatment.

Brexanolone was well-tolerated, with no serious adverse events or treatment discontinuations. Fewer patients who received active treatment (4) than placebo (8) reported mild adverse events. The most frequently reported adverse effects of brexanolone were dizziness and somnolence.

Among the limitations cited by the investigators was the use of a “very strict definition of postpartum depression” (HAM-D scores greater than or equal to 26).

Dr. Kanes and his associates reported that a phase III study currently underway is looking into the possible use of brexanolone in women with “varying degrees of severity.”

“Our findings provide the first placebo-controlled clinical support for the role of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the modulation of mood and affective states in any clinical population. The large effect size seen in this trial contrasts with that observed in studies of currently available and widely used antidepressants, including [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], [selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and tricyclics,” Dr. Kanes and his associates noted.

The impressive findings by Kanes et al., even though based on a very small sample of patients, are promising for new mothers who have postpartum depression and for the clinicians who treat them, wrote Ian Jones, PhD, in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Kanes’s report (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31546-5).

Now, the pressing need is for larger phase III trials to replicate these results in postpartum depression. After that, researchers can address whether brexanolone is effective for other psychiatric conditions triggered by childbirth, such as postpartum psychosis, or even for a wider spectrum of reproductive- and endocrine-related mood disorders such as those related to menstruation and menopause. Eventually, brexanolone or similar agents may even prove helpful in preventing postpartum depression in women at high risk for the disorder.

“Those of us hoping for the development of effective pharmacological treatments that specifically target postpartum depression have, like our patients, felt in a dark place,” Dr. Jones wrote. “With the very encouraging results of this trial, perhaps we can begin to see the first glimpses of light.”

Dr. Jones is affiliated with the National Centre for Mental Health and the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics at Cardiff (Wales) University. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The impressive findings by Kanes et al., even though based on a very small sample of patients, are promising for new mothers who have postpartum depression and for the clinicians who treat them, wrote Ian Jones, PhD, in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Kanes’s report (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31546-5).

Now, the pressing need is for larger phase III trials to replicate these results in postpartum depression. After that, researchers can address whether brexanolone is effective for other psychiatric conditions triggered by childbirth, such as postpartum psychosis, or even for a wider spectrum of reproductive- and endocrine-related mood disorders such as those related to menstruation and menopause. Eventually, brexanolone or similar agents may even prove helpful in preventing postpartum depression in women at high risk for the disorder.

“Those of us hoping for the development of effective pharmacological treatments that specifically target postpartum depression have, like our patients, felt in a dark place,” Dr. Jones wrote. “With the very encouraging results of this trial, perhaps we can begin to see the first glimpses of light.”

Dr. Jones is affiliated with the National Centre for Mental Health and the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics at Cardiff (Wales) University. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The impressive findings by Kanes et al., even though based on a very small sample of patients, are promising for new mothers who have postpartum depression and for the clinicians who treat them, wrote Ian Jones, PhD, in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Kanes’s report (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31546-5).

Now, the pressing need is for larger phase III trials to replicate these results in postpartum depression. After that, researchers can address whether brexanolone is effective for other psychiatric conditions triggered by childbirth, such as postpartum psychosis, or even for a wider spectrum of reproductive- and endocrine-related mood disorders such as those related to menstruation and menopause. Eventually, brexanolone or similar agents may even prove helpful in preventing postpartum depression in women at high risk for the disorder.

“Those of us hoping for the development of effective pharmacological treatments that specifically target postpartum depression have, like our patients, felt in a dark place,” Dr. Jones wrote. “With the very encouraging results of this trial, perhaps we can begin to see the first glimpses of light.”

Dr. Jones is affiliated with the National Centre for Mental Health and the MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics at Cardiff (Wales) University. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A single 60-hour infusion of brexanolone dramatically and rapidly improves severe postpartum depression with minimal adverse effects, a small manufacturer-conducted phase II trial suggests.

Brexanolone is a proprietary formulation of allopregnanolone, the major metabolite of progesterone and a potent modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors that has demonstrated profound benefits for anxiety and depression symptoms in animal models. Plasma levels of allopregnanolone rise to a peak during the third trimester of pregnancy, then abruptly fall after childbirth. “Failure of GABAA receptors to adapt to these changes at parturition has been postulated to have a role in triggering postpartum depression,” said Stephen Kanes, MD, of Sage Therapeutics, Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They assessed the drug’s effects in 21 women hospitalized for severe postpartum depression at 11 U.S. medical centers during a 5-month period. The study participants, who had Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scores of 26 or higher at baseline, randomized to receive a 60-hour infusion of brexanolone (10 patients) or a matching placebo (11 patients) in a double-blind fashion.

The primary outcome measure – mean reduction in HAM-D score at the end of the 60-hour infusion – was 21.0 points with brexanolone, significantly greater than the 8.8 point reduction seen with placebo. Women in the active-treatment group began showing a marked improvement within 24 hours of beginning the infusion, which was maintained throughout the week of treatment, as well as for the succeeding 30 days of follow-up.

Of the 10 patients, 7 receiving brexanolone (70%), compared with only 1 of those receiving placebo (9%), achieved remission of depression (HAM-D score of 7 or less) by the end of treatment. That remission occurred within 24 hours of beginning the infusion in six of the women in the brexanolone group. Moreover, improvement extended beyond the core depressive symptoms, with women in the active-treatment group also showing rapid and marked improvement on Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale scores, the investigators said (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-67369(17)31264-3).

Two women who received brexanolone admitted that, at baseline, they’d had active suicidal ideation with a specific plan and intent. Neither was suicidal after treatment.

Brexanolone was well-tolerated, with no serious adverse events or treatment discontinuations. Fewer patients who received active treatment (4) than placebo (8) reported mild adverse events. The most frequently reported adverse effects of brexanolone were dizziness and somnolence.

Among the limitations cited by the investigators was the use of a “very strict definition of postpartum depression” (HAM-D scores greater than or equal to 26).

Dr. Kanes and his associates reported that a phase III study currently underway is looking into the possible use of brexanolone in women with “varying degrees of severity.”

“Our findings provide the first placebo-controlled clinical support for the role of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the modulation of mood and affective states in any clinical population. The large effect size seen in this trial contrasts with that observed in studies of currently available and widely used antidepressants, including [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], [selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and tricyclics,” Dr. Kanes and his associates noted.

A single 60-hour infusion of brexanolone dramatically and rapidly improves severe postpartum depression with minimal adverse effects, a small manufacturer-conducted phase II trial suggests.

Brexanolone is a proprietary formulation of allopregnanolone, the major metabolite of progesterone and a potent modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors that has demonstrated profound benefits for anxiety and depression symptoms in animal models. Plasma levels of allopregnanolone rise to a peak during the third trimester of pregnancy, then abruptly fall after childbirth. “Failure of GABAA receptors to adapt to these changes at parturition has been postulated to have a role in triggering postpartum depression,” said Stephen Kanes, MD, of Sage Therapeutics, Cambridge, Mass., and his associates.

They assessed the drug’s effects in 21 women hospitalized for severe postpartum depression at 11 U.S. medical centers during a 5-month period. The study participants, who had Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) scores of 26 or higher at baseline, randomized to receive a 60-hour infusion of brexanolone (10 patients) or a matching placebo (11 patients) in a double-blind fashion.

The primary outcome measure – mean reduction in HAM-D score at the end of the 60-hour infusion – was 21.0 points with brexanolone, significantly greater than the 8.8 point reduction seen with placebo. Women in the active-treatment group began showing a marked improvement within 24 hours of beginning the infusion, which was maintained throughout the week of treatment, as well as for the succeeding 30 days of follow-up.

Of the 10 patients, 7 receiving brexanolone (70%), compared with only 1 of those receiving placebo (9%), achieved remission of depression (HAM-D score of 7 or less) by the end of treatment. That remission occurred within 24 hours of beginning the infusion in six of the women in the brexanolone group. Moreover, improvement extended beyond the core depressive symptoms, with women in the active-treatment group also showing rapid and marked improvement on Clinical Global Impression–Improvement Scale scores, the investigators said (Lancet. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-67369(17)31264-3).

Two women who received brexanolone admitted that, at baseline, they’d had active suicidal ideation with a specific plan and intent. Neither was suicidal after treatment.

Brexanolone was well-tolerated, with no serious adverse events or treatment discontinuations. Fewer patients who received active treatment (4) than placebo (8) reported mild adverse events. The most frequently reported adverse effects of brexanolone were dizziness and somnolence.

Among the limitations cited by the investigators was the use of a “very strict definition of postpartum depression” (HAM-D scores greater than or equal to 26).

Dr. Kanes and his associates reported that a phase III study currently underway is looking into the possible use of brexanolone in women with “varying degrees of severity.”

“Our findings provide the first placebo-controlled clinical support for the role of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in the modulation of mood and affective states in any clinical population. The large effect size seen in this trial contrasts with that observed in studies of currently available and widely used antidepressants, including [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors], [selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and tricyclics,” Dr. Kanes and his associates noted.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: A single 60-hour infusion of brexanolone dramatically and rapidly improved severe postpartum depression with minimal adverse effects in a small manufacturer-conducted phase II trial.

Major finding: The primary outcome measure – mean reduction in HAM-D score at the end of the 60-hour infusion – was 21.0 points with brexanolone vs. 8.8 points with placebo.

Data source: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial involving 21 women with severe postpartum depression.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sage Therapeutics, maker of brexanolone, which also was involved in the study design, collection,and interpretation of the data and the writing of the report. Dr. Kanes is an employee of Sage Therapeutics, and several of his associates reported being employees of or consultants for the company.

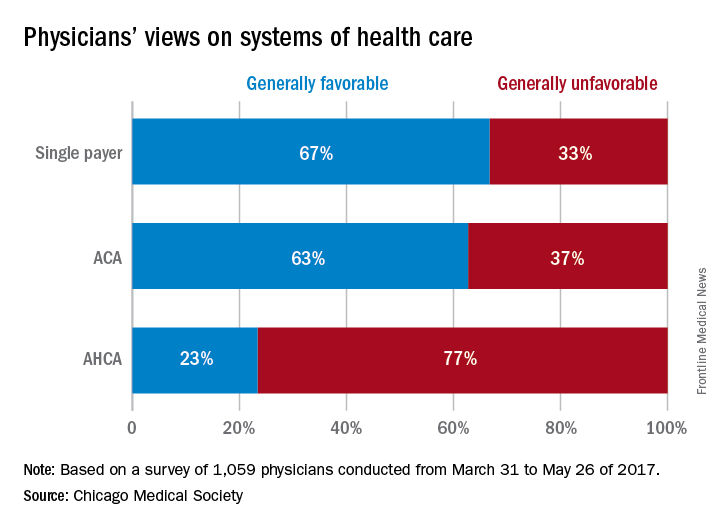

Survey: Most doctors would pick single payer over ACA, ACHA

CHICAGO – If given the option, the majority of physicians would scrap both the Affordable Care Act and the proposed American Health Care Act (AHCA) and opt for a single payer health care system, according to a survey of 1,059 doctors by the Chicago Medical Society (CMS).

When asked their preferred health care structure, 53% of physician said they would prefer a single payer health system, while 26% preferred the Affordable Care Act, and 13% said they would like to see the ACA repealed and replaced with the AHCA. Another 8% of doctors stated they would prefer repeal of the ACA but did not offer a replacement option.

The high percentage of physicians who favored a single payer system was surprising, said A. Jay Chauhan, DO, secretary and chair of public health for the Chicago Medical Society.

“That is a shift from past surveys,” Dr. Chauhan said during an interview at a conference held by the American Bar Association. “It certainly speaks to the frustration that physicians are [feeling] and how difficult it is to practice. I think they’re trying to reach out for other alternatives because the current manner in which we’re practicing doesn’t seem to fulfill our desires to better take care of patients.”

Respondents also choose a single payer system as their top preference when asked which health care system they believed would provide “the best care to the greatest number of people for a given amount of funding.”

A primary takeaway from the survey is that physicians want to see better access to health care for their patients and more affordable insurance coverage, said Katherine M. Tynus, MD, immediate past president of the Chicago Medical Society and president-elect of the Illinois State Medical Society.

“I think what the Affordable Care Act did was raise expectations as far as access to care and people being able to afford their health care,” Dr. Tynus said in an interview at the meeting. “Since that system seems to be failing, the expectation remains. Now, we need to find an alternative solution to achieve that.”

The online survey, released at the Physicians Legal Issues Conference held by the American Bar Association, was conducted between March 2017 and May 2017 and featured questions about health reform. Survey participants were physicians primarily based in the Chicago area or within Illinois and the majority practiced in an urban area. Respondents represented a variety of political affiliations and medical specialties. The majority said they identifying as independent (43%), and the most common specialty was general medicine (19%).

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

CHICAGO – If given the option, the majority of physicians would scrap both the Affordable Care Act and the proposed American Health Care Act (AHCA) and opt for a single payer health care system, according to a survey of 1,059 doctors by the Chicago Medical Society (CMS).

When asked their preferred health care structure, 53% of physician said they would prefer a single payer health system, while 26% preferred the Affordable Care Act, and 13% said they would like to see the ACA repealed and replaced with the AHCA. Another 8% of doctors stated they would prefer repeal of the ACA but did not offer a replacement option.

The high percentage of physicians who favored a single payer system was surprising, said A. Jay Chauhan, DO, secretary and chair of public health for the Chicago Medical Society.

“That is a shift from past surveys,” Dr. Chauhan said during an interview at a conference held by the American Bar Association. “It certainly speaks to the frustration that physicians are [feeling] and how difficult it is to practice. I think they’re trying to reach out for other alternatives because the current manner in which we’re practicing doesn’t seem to fulfill our desires to better take care of patients.”

Respondents also choose a single payer system as their top preference when asked which health care system they believed would provide “the best care to the greatest number of people for a given amount of funding.”

A primary takeaway from the survey is that physicians want to see better access to health care for their patients and more affordable insurance coverage, said Katherine M. Tynus, MD, immediate past president of the Chicago Medical Society and president-elect of the Illinois State Medical Society.

“I think what the Affordable Care Act did was raise expectations as far as access to care and people being able to afford their health care,” Dr. Tynus said in an interview at the meeting. “Since that system seems to be failing, the expectation remains. Now, we need to find an alternative solution to achieve that.”

The online survey, released at the Physicians Legal Issues Conference held by the American Bar Association, was conducted between March 2017 and May 2017 and featured questions about health reform. Survey participants were physicians primarily based in the Chicago area or within Illinois and the majority practiced in an urban area. Respondents represented a variety of political affiliations and medical specialties. The majority said they identifying as independent (43%), and the most common specialty was general medicine (19%).

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

CHICAGO – If given the option, the majority of physicians would scrap both the Affordable Care Act and the proposed American Health Care Act (AHCA) and opt for a single payer health care system, according to a survey of 1,059 doctors by the Chicago Medical Society (CMS).

When asked their preferred health care structure, 53% of physician said they would prefer a single payer health system, while 26% preferred the Affordable Care Act, and 13% said they would like to see the ACA repealed and replaced with the AHCA. Another 8% of doctors stated they would prefer repeal of the ACA but did not offer a replacement option.

The high percentage of physicians who favored a single payer system was surprising, said A. Jay Chauhan, DO, secretary and chair of public health for the Chicago Medical Society.

“That is a shift from past surveys,” Dr. Chauhan said during an interview at a conference held by the American Bar Association. “It certainly speaks to the frustration that physicians are [feeling] and how difficult it is to practice. I think they’re trying to reach out for other alternatives because the current manner in which we’re practicing doesn’t seem to fulfill our desires to better take care of patients.”

Respondents also choose a single payer system as their top preference when asked which health care system they believed would provide “the best care to the greatest number of people for a given amount of funding.”

A primary takeaway from the survey is that physicians want to see better access to health care for their patients and more affordable insurance coverage, said Katherine M. Tynus, MD, immediate past president of the Chicago Medical Society and president-elect of the Illinois State Medical Society.

“I think what the Affordable Care Act did was raise expectations as far as access to care and people being able to afford their health care,” Dr. Tynus said in an interview at the meeting. “Since that system seems to be failing, the expectation remains. Now, we need to find an alternative solution to achieve that.”

The online survey, released at the Physicians Legal Issues Conference held by the American Bar Association, was conducted between March 2017 and May 2017 and featured questions about health reform. Survey participants were physicians primarily based in the Chicago area or within Illinois and the majority practiced in an urban area. Respondents represented a variety of political affiliations and medical specialties. The majority said they identifying as independent (43%), and the most common specialty was general medicine (19%).

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

AT THE PHYSICIANS LEGAL ISSUES CONFERENCE

VIDEO: Tocilizumab tested in children with sJIA under 2 years old

MADRID – The results of the first trial of a biologic agent in children less than 2 years of age with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) suggest that tocilizumab is likely to be effective in this age group.

“sJIA is the most severe form of childhood arthritis, and as you are aware, it’s the most difficult to treat as well,” said Navita L. Mallalieu, PhD, director of clinical pharmacology at Roche Innovation Center New York, the company that funded the study.

Tocilizumab (Actemra) has been available for the treatment of sJIA, both in the United States and the European Union since 2011, she observed at the European Congress of Rheumatology, but only for children aged 2 years or older at the current time.

Because of this prior history of use in sJIA, “we have confidence in the safety profile, and so we were able to go to the next step of testing children who were even younger than 2 years of age,” Dr. Mallalieu said in a video interview.

[polldaddy:9771949]

Dr. Mallalieu presented findings from an open-label, single-arm, phase I trial that evaluated a 12 mg/kg dosing regimen of tocilizumab, which was given intravenously every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. Eleven children were studied who had a mean age of 1.3 years and active disease for at least 1 month despite treatment with glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The primary endpoint was the pharmacokinetics of tocilizumab in this younger patient population, and secondary endpoints were safety, pharmacodynamics, and exploring the efficacy over 12 weeks on top of stable background therapy, she explained.

Results showed that tocilizumab in children under 2 years of age could achieve pharmacokinetics similar to those seen in older children in the TENDER trial (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2385-95), which is the trial that helped the biologic get licensed for use in the older sJIA population. Reductions in soluble interleukin-6 receptor, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were seen, again to a similar extent as seen in the TENDER trial. There was also an indication that similar reductions in the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 score could be achieved, Dr. Mallalieu reported.

While the pattern and nature of adverse events were similar to those seen in the TENDER trial, there were more cases of hypersensitivity in this phase I study. Four cases of hypersensitivity were clinically confirmed, three of which were deemed serious. The three serious cases were observed at day 15, with two of the cases associated with multiple signs and symptoms that were confounded by either subclinical macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or a faster infusion rate. One patient had urticaria and was hospitalized for observation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MADRID – The results of the first trial of a biologic agent in children less than 2 years of age with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) suggest that tocilizumab is likely to be effective in this age group.

“sJIA is the most severe form of childhood arthritis, and as you are aware, it’s the most difficult to treat as well,” said Navita L. Mallalieu, PhD, director of clinical pharmacology at Roche Innovation Center New York, the company that funded the study.

Tocilizumab (Actemra) has been available for the treatment of sJIA, both in the United States and the European Union since 2011, she observed at the European Congress of Rheumatology, but only for children aged 2 years or older at the current time.

Because of this prior history of use in sJIA, “we have confidence in the safety profile, and so we were able to go to the next step of testing children who were even younger than 2 years of age,” Dr. Mallalieu said in a video interview.

[polldaddy:9771949]

Dr. Mallalieu presented findings from an open-label, single-arm, phase I trial that evaluated a 12 mg/kg dosing regimen of tocilizumab, which was given intravenously every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. Eleven children were studied who had a mean age of 1.3 years and active disease for at least 1 month despite treatment with glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The primary endpoint was the pharmacokinetics of tocilizumab in this younger patient population, and secondary endpoints were safety, pharmacodynamics, and exploring the efficacy over 12 weeks on top of stable background therapy, she explained.

Results showed that tocilizumab in children under 2 years of age could achieve pharmacokinetics similar to those seen in older children in the TENDER trial (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2385-95), which is the trial that helped the biologic get licensed for use in the older sJIA population. Reductions in soluble interleukin-6 receptor, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were seen, again to a similar extent as seen in the TENDER trial. There was also an indication that similar reductions in the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 score could be achieved, Dr. Mallalieu reported.

While the pattern and nature of adverse events were similar to those seen in the TENDER trial, there were more cases of hypersensitivity in this phase I study. Four cases of hypersensitivity were clinically confirmed, three of which were deemed serious. The three serious cases were observed at day 15, with two of the cases associated with multiple signs and symptoms that were confounded by either subclinical macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or a faster infusion rate. One patient had urticaria and was hospitalized for observation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MADRID – The results of the first trial of a biologic agent in children less than 2 years of age with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) suggest that tocilizumab is likely to be effective in this age group.

“sJIA is the most severe form of childhood arthritis, and as you are aware, it’s the most difficult to treat as well,” said Navita L. Mallalieu, PhD, director of clinical pharmacology at Roche Innovation Center New York, the company that funded the study.

Tocilizumab (Actemra) has been available for the treatment of sJIA, both in the United States and the European Union since 2011, she observed at the European Congress of Rheumatology, but only for children aged 2 years or older at the current time.

Because of this prior history of use in sJIA, “we have confidence in the safety profile, and so we were able to go to the next step of testing children who were even younger than 2 years of age,” Dr. Mallalieu said in a video interview.

[polldaddy:9771949]

Dr. Mallalieu presented findings from an open-label, single-arm, phase I trial that evaluated a 12 mg/kg dosing regimen of tocilizumab, which was given intravenously every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. Eleven children were studied who had a mean age of 1.3 years and active disease for at least 1 month despite treatment with glucocorticoids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The primary endpoint was the pharmacokinetics of tocilizumab in this younger patient population, and secondary endpoints were safety, pharmacodynamics, and exploring the efficacy over 12 weeks on top of stable background therapy, she explained.

Results showed that tocilizumab in children under 2 years of age could achieve pharmacokinetics similar to those seen in older children in the TENDER trial (N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2385-95), which is the trial that helped the biologic get licensed for use in the older sJIA population. Reductions in soluble interleukin-6 receptor, C-reactive protein, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were seen, again to a similar extent as seen in the TENDER trial. There was also an indication that similar reductions in the Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS)-71 score could be achieved, Dr. Mallalieu reported.

While the pattern and nature of adverse events were similar to those seen in the TENDER trial, there were more cases of hypersensitivity in this phase I study. Four cases of hypersensitivity were clinically confirmed, three of which were deemed serious. The three serious cases were observed at day 15, with two of the cases associated with multiple signs and symptoms that were confounded by either subclinical macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or a faster infusion rate. One patient had urticaria and was hospitalized for observation.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Similar pharmacokinetics were observed in children under 2 years of age as those seen in a prior study of older children.

Data source: Open-label, single-arm, phase I trial that evaluated a 12-mg/kg dosing regimen of tocilizumab given intravenously every 2 weeks for 12 weeks.

Disclosures: Roche funded the study. The presenter is an employee of Roche.

Teens’ overall tobacco use falls, but e-cigs now most popular product

Twenty percent of surveyed high school students and 7% of middle school students were using some kind of tobacco product in 2016 – and e-cigarettes were the most commonly used product among those groups, according to an analysis from federal researchers.

, although combustible tobacco product use declined in both groups, said Ahmed Jamal, MD, of the Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and his associates. That was determined using data from the 2011-2016 National Youth Tobacco Surveys, which assessed tobacco use in the past 30 days by groups of middle school and high school students numbering from more than 17,000 to almost 25,000.

High school boys had higher use of any tobacco product, two or more tobacco products, cigars, smokeless tobacco, and pipe tobacco than did high school girls. The most commonly used tobacco product among non-Hispanic white (13.7%) and Hispanic high school students (10%) were e-cigarettes; cigars were the most commonly used tobacco product among non-Hispanic black high school students (9.5%).

Seven percent of middle school students had used any tobacco product within the past 30 days, and 3% had used two or more tobacco products. Similar to high school students, e-cigarettes were the most commonly used tobacco product among middle school students (4.3%), followed by cigarettes (2%), cigars (2%), smokeless tobacco (2%), hookahs (2%), pipe tobacco (0.7%), and bidis (0.3%).

Use of any tobacco product among middle school boys was 8.3%, and among middle school girls use was 6%. Hispanic middle school students reported higher use of any tobacco product, were more likely to use two or more tobacco products, and said they used hookahs more often than did non-Hispanic white middle school students.

Looking at the changes from 2011 to 2016, current use of any tobacco product did not change significantly among high school students (falling from 24% to 20%), but there was a reduction in current use of any combustible tobacco product (22%-14%) and in use of two or more tobacco products (12%-9.6%) over this time period.

By product type, there were increases in current use of e-cigarettes (from 1.5% to 11.3%) and hookahs (from 4.1% to 4.8%) among high school students, as well as decreases in current use of cigarettes (from 16% to 8%), cigars (from 12% to 8%), smokeless tobacco (from 8% to 6%), pipe tobacco (from 4% to 1%), and bidis (from 2% to 0.5%).

Among middle school students during 2011-2016, there was a rise in current use of e-cigarettes (from 0.6% to 4%), and in current use of hookahs (from 1% to 2%). There was a drop in current use of any combustible tobacco products (from 6% to 4%), cigarettes (from 4% to 2%), cigars (from 3.5% to 2.2%), and pipe tobacco (from 2% to 0.7%).

“Since February 2014, the Food and Drug Administration’s first national tobacco public education campaign, the Real Cost, has broadcasted tobacco education advertising designed for youths aged 12-17 years; the campaign was associated with an estimated 348,398 U.S. youths who did not initiate cigarette smoking during February 2014–March 2016,” the investigators said. “Continued implementation of these strategies can help prevent and further reduce the use of all forms of tobacco product among U.S. youths.”

Read more in MMWR (2017 Jun 16;66[23]:597-603).

Twenty percent of surveyed high school students and 7% of middle school students were using some kind of tobacco product in 2016 – and e-cigarettes were the most commonly used product among those groups, according to an analysis from federal researchers.

, although combustible tobacco product use declined in both groups, said Ahmed Jamal, MD, of the Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and his associates. That was determined using data from the 2011-2016 National Youth Tobacco Surveys, which assessed tobacco use in the past 30 days by groups of middle school and high school students numbering from more than 17,000 to almost 25,000.

High school boys had higher use of any tobacco product, two or more tobacco products, cigars, smokeless tobacco, and pipe tobacco than did high school girls. The most commonly used tobacco product among non-Hispanic white (13.7%) and Hispanic high school students (10%) were e-cigarettes; cigars were the most commonly used tobacco product among non-Hispanic black high school students (9.5%).