User login

CAR T-cell therapy produces durable CRs in ALL

Updated results from the phase 2 ELIANA study have shown that tisagenlecleucel can produce durable complete responses (CRs) in children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Sixty percent of patients who received the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy achieved a CR, and 21% had a CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi).

The median duration of CR/CRi was not reached at a median follow-up of 13.1 months.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) was cytokine release syndrome (CRS), occurring in 77% of patients.

Researchers reported these results in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Novartis.

“This expanded, global study of CAR T-cell therapy gives us further evidence of how remarkable this treatment can be for our young patients in whom all other treatments failed,” said study author Shannon L. Maude, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Our data show not only can we can achieve longer-term durable remissions and longer-term survival for our patients but that these personalized, cancer-fighting cells can remain in the body for months or even years, effectively doing their job.”

The trial included 75 patients who received tisagenlecleucel. At enrollment, the patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 to 8), and they had a median marrow blast percentage of 74% (range, 5 to 99).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Most (n=72) received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to the CAR T cells.

Results

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CRi within 3 months. The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi.

All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

The researchers said tisagenlecleucel persisted in the blood for as long as 20 months.

The relapse-free survival rate among patients with a CR/CRi was 80% at 6 months and 59% at 12 months.

Seventeen patients who had achieved a CR relapsed before receiving subsequent treatment. Three patients went on to subsequent therapy before relapse but ultimately relapsed.

Relapse was also reported in 2 patients who had been classified as non-responders because they did not maintain a response for at least 28 days.

Eight patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant while in remission, and all 8 were alive when the manuscript for this study was submitted. Four patients had not relapsed, and the other 4 had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the overall survival rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

All patients experienced at least 1 AE, and 95% had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 88% of patients. In 73% of patients, these AEs were thought to be related to treatment.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

The median duration of CRS was 8 days (range, 1-36). Forty-seven patients were admitted to the intensive care unit to receive treatment for CRS, with a median stay of 7 days (range, 1-34).

“One of our more challenging questions—‘Can we manage the serious side effects of CAR T-cell therapy?’—was asked and answered in this global study,” said author Stephan A. Grupp, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“Some of our patients get very sick, but we showed that most toxic effects can be short-lived and reversible, with the potential for our patients to achieve durable complete remissions. That’s a pretty amazing turnaround for the high-risk child who, up until now, had little chance of surviving.” ![]()

Updated results from the phase 2 ELIANA study have shown that tisagenlecleucel can produce durable complete responses (CRs) in children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Sixty percent of patients who received the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy achieved a CR, and 21% had a CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi).

The median duration of CR/CRi was not reached at a median follow-up of 13.1 months.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) was cytokine release syndrome (CRS), occurring in 77% of patients.

Researchers reported these results in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Novartis.

“This expanded, global study of CAR T-cell therapy gives us further evidence of how remarkable this treatment can be for our young patients in whom all other treatments failed,” said study author Shannon L. Maude, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Our data show not only can we can achieve longer-term durable remissions and longer-term survival for our patients but that these personalized, cancer-fighting cells can remain in the body for months or even years, effectively doing their job.”

The trial included 75 patients who received tisagenlecleucel. At enrollment, the patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 to 8), and they had a median marrow blast percentage of 74% (range, 5 to 99).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Most (n=72) received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to the CAR T cells.

Results

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CRi within 3 months. The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi.

All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

The researchers said tisagenlecleucel persisted in the blood for as long as 20 months.

The relapse-free survival rate among patients with a CR/CRi was 80% at 6 months and 59% at 12 months.

Seventeen patients who had achieved a CR relapsed before receiving subsequent treatment. Three patients went on to subsequent therapy before relapse but ultimately relapsed.

Relapse was also reported in 2 patients who had been classified as non-responders because they did not maintain a response for at least 28 days.

Eight patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant while in remission, and all 8 were alive when the manuscript for this study was submitted. Four patients had not relapsed, and the other 4 had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the overall survival rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

All patients experienced at least 1 AE, and 95% had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 88% of patients. In 73% of patients, these AEs were thought to be related to treatment.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

The median duration of CRS was 8 days (range, 1-36). Forty-seven patients were admitted to the intensive care unit to receive treatment for CRS, with a median stay of 7 days (range, 1-34).

“One of our more challenging questions—‘Can we manage the serious side effects of CAR T-cell therapy?’—was asked and answered in this global study,” said author Stephan A. Grupp, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“Some of our patients get very sick, but we showed that most toxic effects can be short-lived and reversible, with the potential for our patients to achieve durable complete remissions. That’s a pretty amazing turnaround for the high-risk child who, up until now, had little chance of surviving.” ![]()

Updated results from the phase 2 ELIANA study have shown that tisagenlecleucel can produce durable complete responses (CRs) in children and young adults with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Sixty percent of patients who received the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy achieved a CR, and 21% had a CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi).

The median duration of CR/CRi was not reached at a median follow-up of 13.1 months.

The most common treatment-related adverse event (AE) was cytokine release syndrome (CRS), occurring in 77% of patients.

Researchers reported these results in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Novartis.

“This expanded, global study of CAR T-cell therapy gives us further evidence of how remarkable this treatment can be for our young patients in whom all other treatments failed,” said study author Shannon L. Maude, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

“Our data show not only can we can achieve longer-term durable remissions and longer-term survival for our patients but that these personalized, cancer-fighting cells can remain in the body for months or even years, effectively doing their job.”

The trial included 75 patients who received tisagenlecleucel. At enrollment, the patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1 to 8), and they had a median marrow blast percentage of 74% (range, 5 to 99).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Most (n=72) received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to the CAR T cells.

Results

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CRi within 3 months. The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi.

All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

The researchers said tisagenlecleucel persisted in the blood for as long as 20 months.

The relapse-free survival rate among patients with a CR/CRi was 80% at 6 months and 59% at 12 months.

Seventeen patients who had achieved a CR relapsed before receiving subsequent treatment. Three patients went on to subsequent therapy before relapse but ultimately relapsed.

Relapse was also reported in 2 patients who had been classified as non-responders because they did not maintain a response for at least 28 days.

Eight patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant while in remission, and all 8 were alive when the manuscript for this study was submitted. Four patients had not relapsed, and the other 4 had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the overall survival rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

All patients experienced at least 1 AE, and 95% had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 88% of patients. In 73% of patients, these AEs were thought to be related to treatment.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

The median duration of CRS was 8 days (range, 1-36). Forty-seven patients were admitted to the intensive care unit to receive treatment for CRS, with a median stay of 7 days (range, 1-34).

“One of our more challenging questions—‘Can we manage the serious side effects of CAR T-cell therapy?’—was asked and answered in this global study,” said author Stephan A. Grupp, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“Some of our patients get very sick, but we showed that most toxic effects can be short-lived and reversible, with the potential for our patients to achieve durable complete remissions. That’s a pretty amazing turnaround for the high-risk child who, up until now, had little chance of surviving.” ![]()

FDA places T-cell therapy on clinical hold

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed BPX-501, a T-cell therapy being evaluated in patients who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs), on clinical hold.

Three cases of encephalopathy possibly related to BPX-501 prompted the agency to impose the hold.

Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the developer of BPX-501, and the company was conducting 4 trials in the US in children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The BPX-501 registration trial in Europe is not affected by the clinical hold.

BPX-501 is designed to fight infection, support engraftment, prevent disease relapse, and potentially stop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) should it occur.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the administration of rimiducid to kill the toxic T cells in the event of GVHD.

The 3 cases of encephalopathy are complex, according to a company press release, and have confounding factors. These include prior failed transplants, prior history of immunodeficiency, concurrent infection, and administration of rimiducid in combination with other medications.

Encephalopathy had not emerged as an adverse event in 240 patients treated with the cell therapy, until now.

BPX-501 had produced encouraging results, according to trial data presented at EHA 2017 and ASH 2017 (abstract 211*).

In this trial, 112 pediatric patients were transfused with BPX-501 cells about 2 weeks after transplant. Patients had acute leukemia (n=53), primary immune deficiencies (n=26), erythroid disorders (n=17), Fanconi anemia (n=7), and other diseases (n=9).

Investigators reported that infused cells expanded and persisted, with peak expansion reached at 9 months after infusion. Investigators continued to detect BPX-501 cells after 2 years.

The European Commission granted BPX-501 orphan drug designation for the agent for treatment in HSCT, and for the activator agent rimiducid for the treatment of GVHD.

And the FDA had granted the agents orphan drug status as a combination replacement T-cell therapy for the treatment of immunodeficiency and GVHD after HSCT.

Bellicum says it is working with the FDA to evaluate the risk of encephalopathy in patients receiving BPX-501. ![]()

* Data in the abstract were updated in the oral presentation and reported on the company’s website.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed BPX-501, a T-cell therapy being evaluated in patients who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs), on clinical hold.

Three cases of encephalopathy possibly related to BPX-501 prompted the agency to impose the hold.

Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the developer of BPX-501, and the company was conducting 4 trials in the US in children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The BPX-501 registration trial in Europe is not affected by the clinical hold.

BPX-501 is designed to fight infection, support engraftment, prevent disease relapse, and potentially stop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) should it occur.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the administration of rimiducid to kill the toxic T cells in the event of GVHD.

The 3 cases of encephalopathy are complex, according to a company press release, and have confounding factors. These include prior failed transplants, prior history of immunodeficiency, concurrent infection, and administration of rimiducid in combination with other medications.

Encephalopathy had not emerged as an adverse event in 240 patients treated with the cell therapy, until now.

BPX-501 had produced encouraging results, according to trial data presented at EHA 2017 and ASH 2017 (abstract 211*).

In this trial, 112 pediatric patients were transfused with BPX-501 cells about 2 weeks after transplant. Patients had acute leukemia (n=53), primary immune deficiencies (n=26), erythroid disorders (n=17), Fanconi anemia (n=7), and other diseases (n=9).

Investigators reported that infused cells expanded and persisted, with peak expansion reached at 9 months after infusion. Investigators continued to detect BPX-501 cells after 2 years.

The European Commission granted BPX-501 orphan drug designation for the agent for treatment in HSCT, and for the activator agent rimiducid for the treatment of GVHD.

And the FDA had granted the agents orphan drug status as a combination replacement T-cell therapy for the treatment of immunodeficiency and GVHD after HSCT.

Bellicum says it is working with the FDA to evaluate the risk of encephalopathy in patients receiving BPX-501. ![]()

* Data in the abstract were updated in the oral presentation and reported on the company’s website.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed BPX-501, a T-cell therapy being evaluated in patients who undergo haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs), on clinical hold.

Three cases of encephalopathy possibly related to BPX-501 prompted the agency to impose the hold.

Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the developer of BPX-501, and the company was conducting 4 trials in the US in children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The BPX-501 registration trial in Europe is not affected by the clinical hold.

BPX-501 is designed to fight infection, support engraftment, prevent disease relapse, and potentially stop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) should it occur.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the administration of rimiducid to kill the toxic T cells in the event of GVHD.

The 3 cases of encephalopathy are complex, according to a company press release, and have confounding factors. These include prior failed transplants, prior history of immunodeficiency, concurrent infection, and administration of rimiducid in combination with other medications.

Encephalopathy had not emerged as an adverse event in 240 patients treated with the cell therapy, until now.

BPX-501 had produced encouraging results, according to trial data presented at EHA 2017 and ASH 2017 (abstract 211*).

In this trial, 112 pediatric patients were transfused with BPX-501 cells about 2 weeks after transplant. Patients had acute leukemia (n=53), primary immune deficiencies (n=26), erythroid disorders (n=17), Fanconi anemia (n=7), and other diseases (n=9).

Investigators reported that infused cells expanded and persisted, with peak expansion reached at 9 months after infusion. Investigators continued to detect BPX-501 cells after 2 years.

The European Commission granted BPX-501 orphan drug designation for the agent for treatment in HSCT, and for the activator agent rimiducid for the treatment of GVHD.

And the FDA had granted the agents orphan drug status as a combination replacement T-cell therapy for the treatment of immunodeficiency and GVHD after HSCT.

Bellicum says it is working with the FDA to evaluate the risk of encephalopathy in patients receiving BPX-501. ![]()

* Data in the abstract were updated in the oral presentation and reported on the company’s website.

Persistent rash on feet

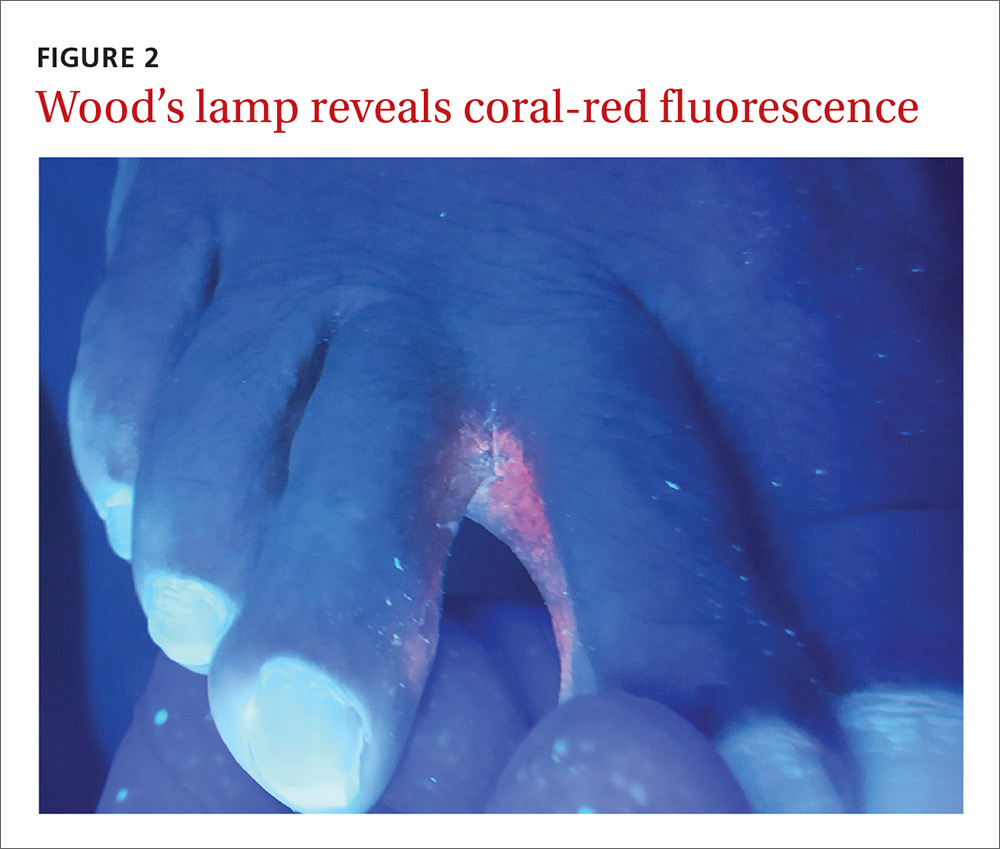

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

A 49-year-old Hispanic woman presented with a 4-month history of scaling and a macerated rash localized between her toes (FIGURE 1). The rash was malodorous, mildly erythematous, and sometimes associated with pruritus. The patient had no relevant medical history. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing was performed and found to be negative. So a Wood’s lamp was used to examine the patient’s toes—and it revealed the diagnosis.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythrasma

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 2), which led us to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.1,2

Interdigital erythrasma is more common than previously thought; in one study of 151 patients with erythrasma, the most common site was the toe webs (64.9%), followed by the inguinal region (17.9%), the axillary region (14.6%), and the inframammary region (2.6%).2 Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state.3

Differential includes “athlete’s foot”

The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes:

Tinea pedis. Erythrasma is often mistaken for tinea pedis, because both conditions cause scaling between the toes. A Wood’s lamp exam can quickly differentiate between the 2,1 as tinea pedis does not fluoresce under ultraviolet light.

Contact dermatitis mimics many conditions, but a negative Wood’s lamp exam and history of worsening with contact to specific substances helps to make this diagnosis.

Prevention and Tx hinge on good hygiene, topical agents

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%.4 Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice.4,5 It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea, because it can treat both conditions. This is not uncommon in the interdigital spaces between the toes and in the groin.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks can also be used to treat the condition.3,6 However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics,6 clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred.2,6

Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

1. Polat M, lhan MN. The prevalence of interdigital erythrasma: a prospective study from an outpatient clinic in Turkey. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2015;105:121-124.

2. Avci O, Tanyildizi T, Kusku E. A comparison between the effectiveness of erythromycin, single-dose clarithromycin and topical fusidic acid in the treatment of erythrasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:70-74.

3. Kibbi AG, Sleiman M. Erythrasma. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052532-overview#a0199. Accessed December 10, 2016.

4. Pitcher DG, Noble WC, Seville RH. Treatment of erythrasma with miconazole. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:453-456.

5. Clayton YM, Knight AG. A clinical double-blind trial of topical miconazole and clotrimazole against superficial fungal infections and erythrasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1:225-232.

6. Holdiness MR. Management of cutaneous erythrasma. Drugs. 2002;62:1131-1141.

Mild cough • wheezing • loud heart sounds • Dx?

THE CASE

A 25-year-old man, who was an active duty US Navy sailor, went to his ship’s medical department complaining of a mild cough that he’d had for 2 days. He denied having any fevers, chills, night sweats, angina, or dyspnea. He said he hadn’t experienced any exertional fatigue or difficulty completing the rigorous physical tasks of his occupation as an engineman on the ship. The patient had no medical or surgical history of significance, and he wasn’t taking any medications or supplements.

On exam, he was not in acute distress and his vital signs were within normal limits. Auscultation revealed mild wheezing throughout the upper lung fields and loud heart sounds throughout his chest that were audible even with gentle contact of the stethoscope diaphragm. He had no discernible murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

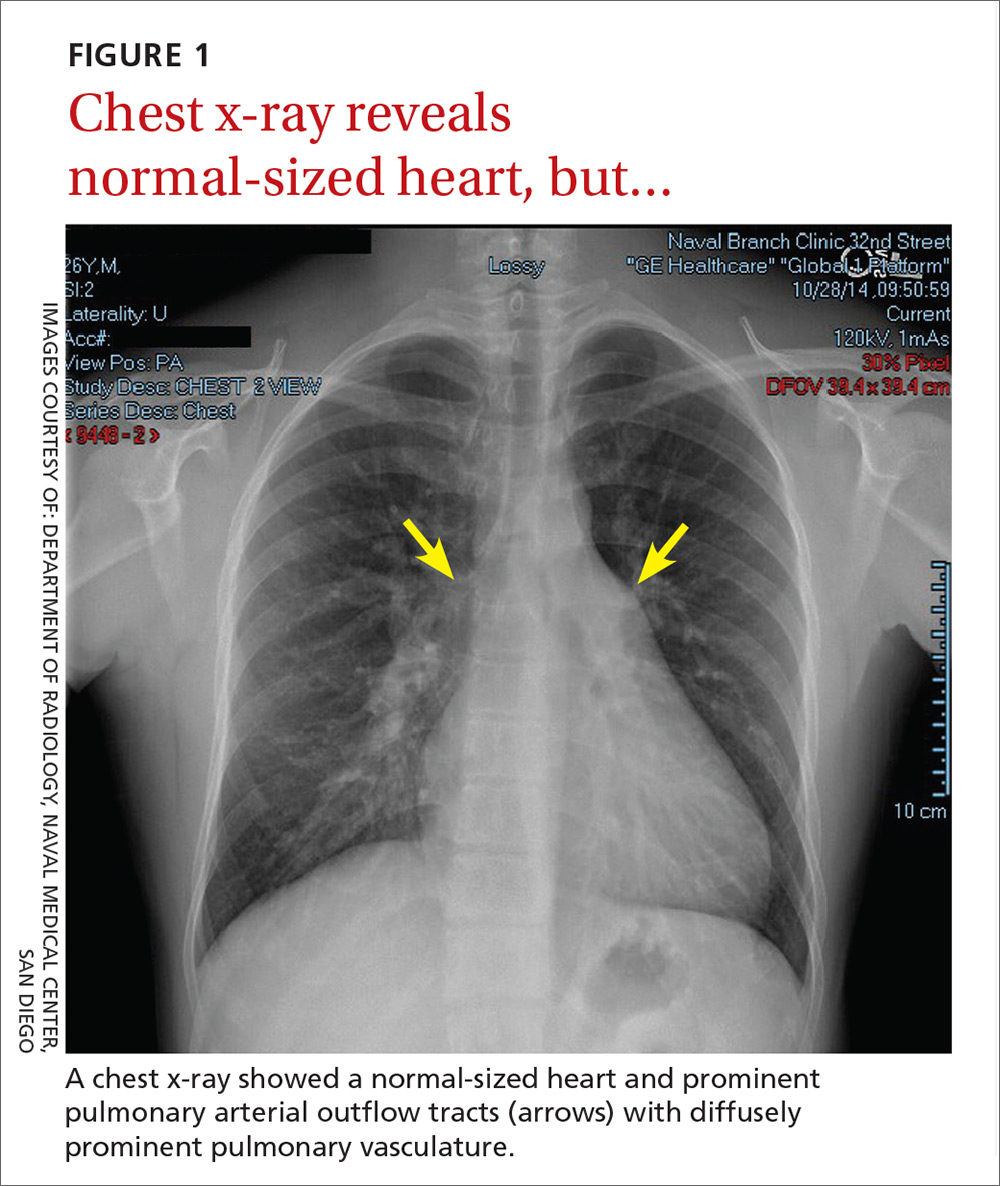

In light of the unusually loud heart sounds heard on exam, we performed an electrocardiogram. The EKG revealed a normal sinus rhythm, slight right axis deviation indicated by tall R-waves in V1 (also suggestive of right ventricular hypertrophy), an incomplete right bundle branch block, and a crochetage sign (a notch in the R-waves of the inferior leads).1 A chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) revealed a normal-sized heart and dilated pulmonary vasculature suggestive of pulmonary hypertension.

THE DIAGNOSIS

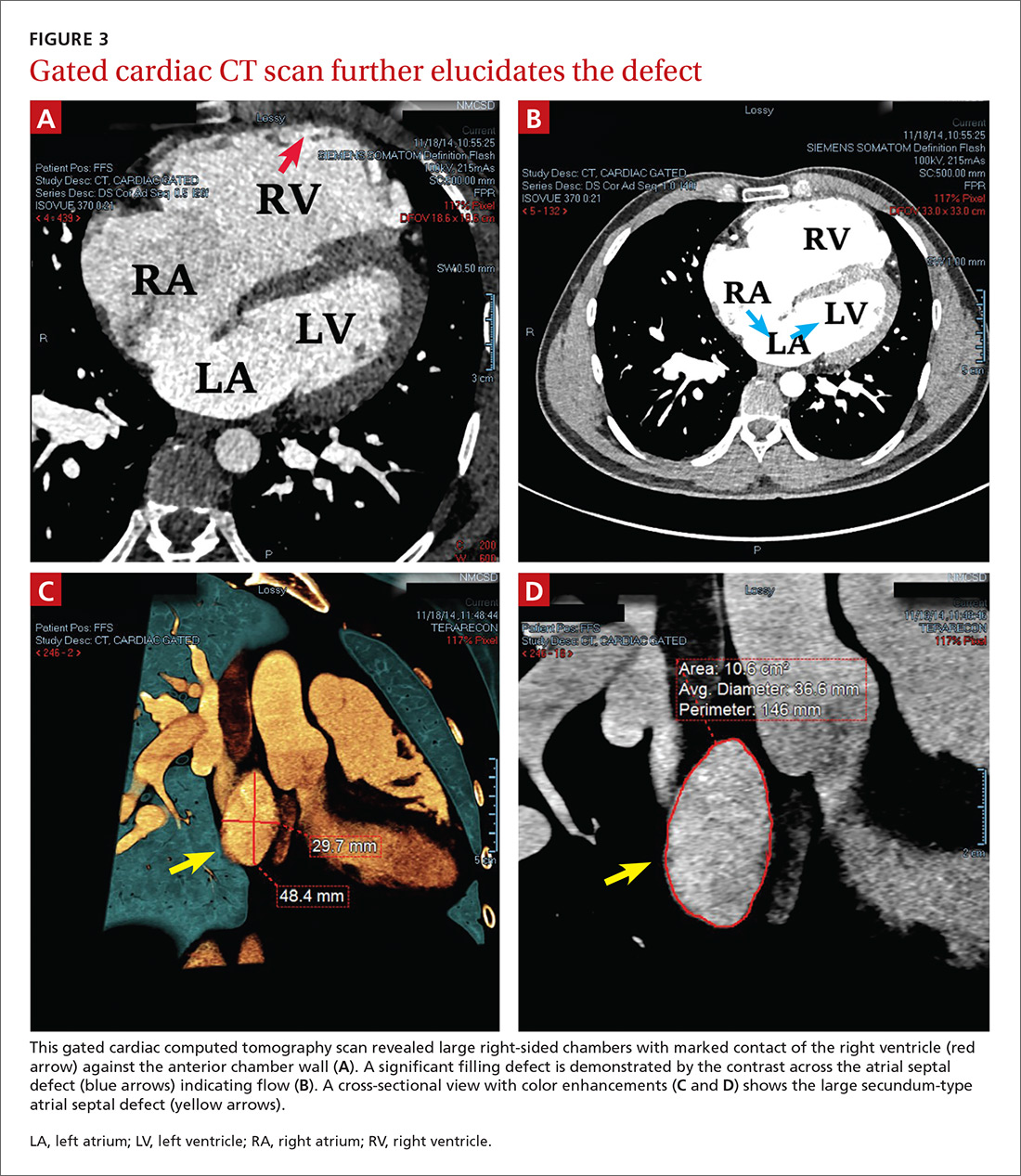

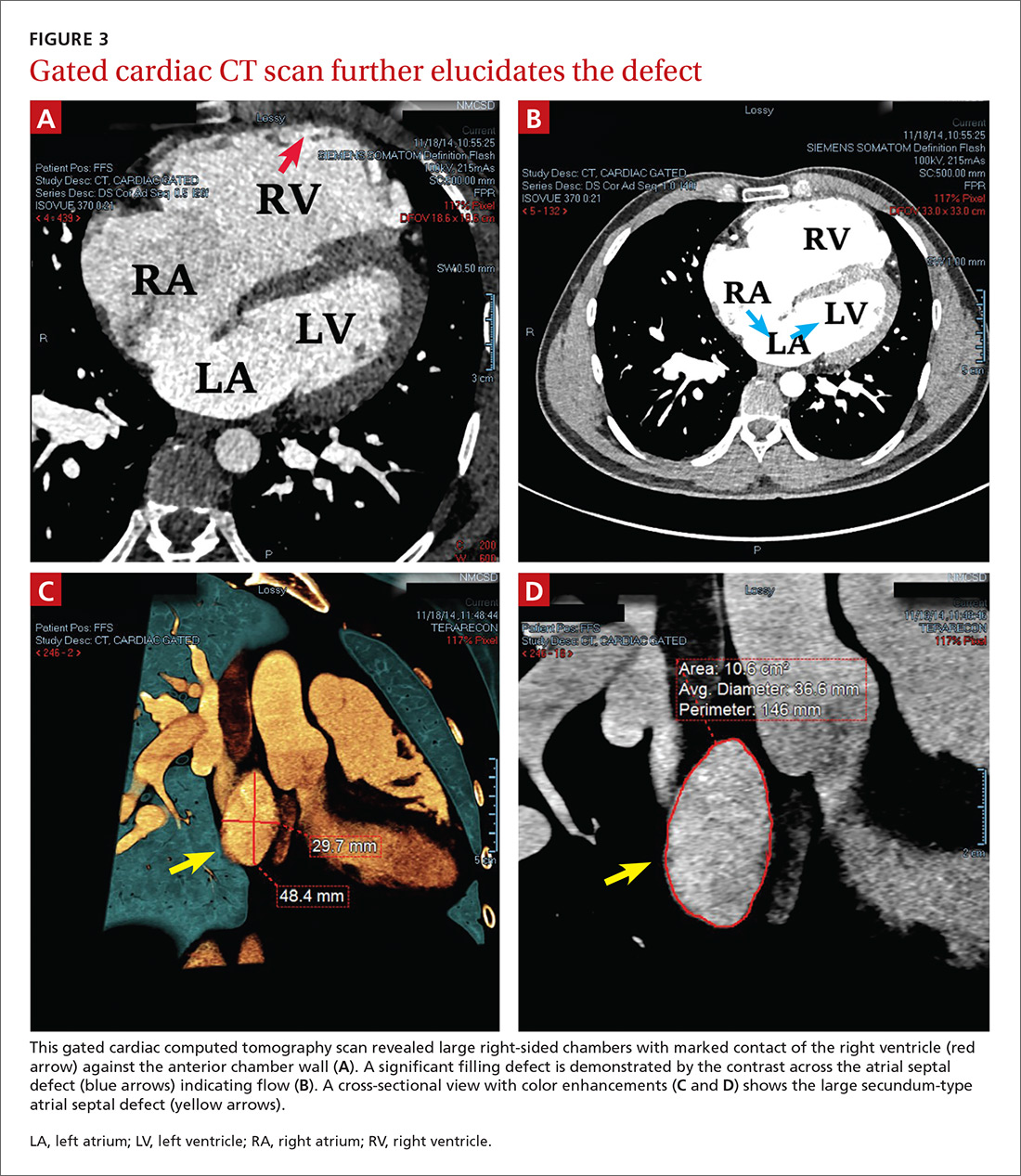

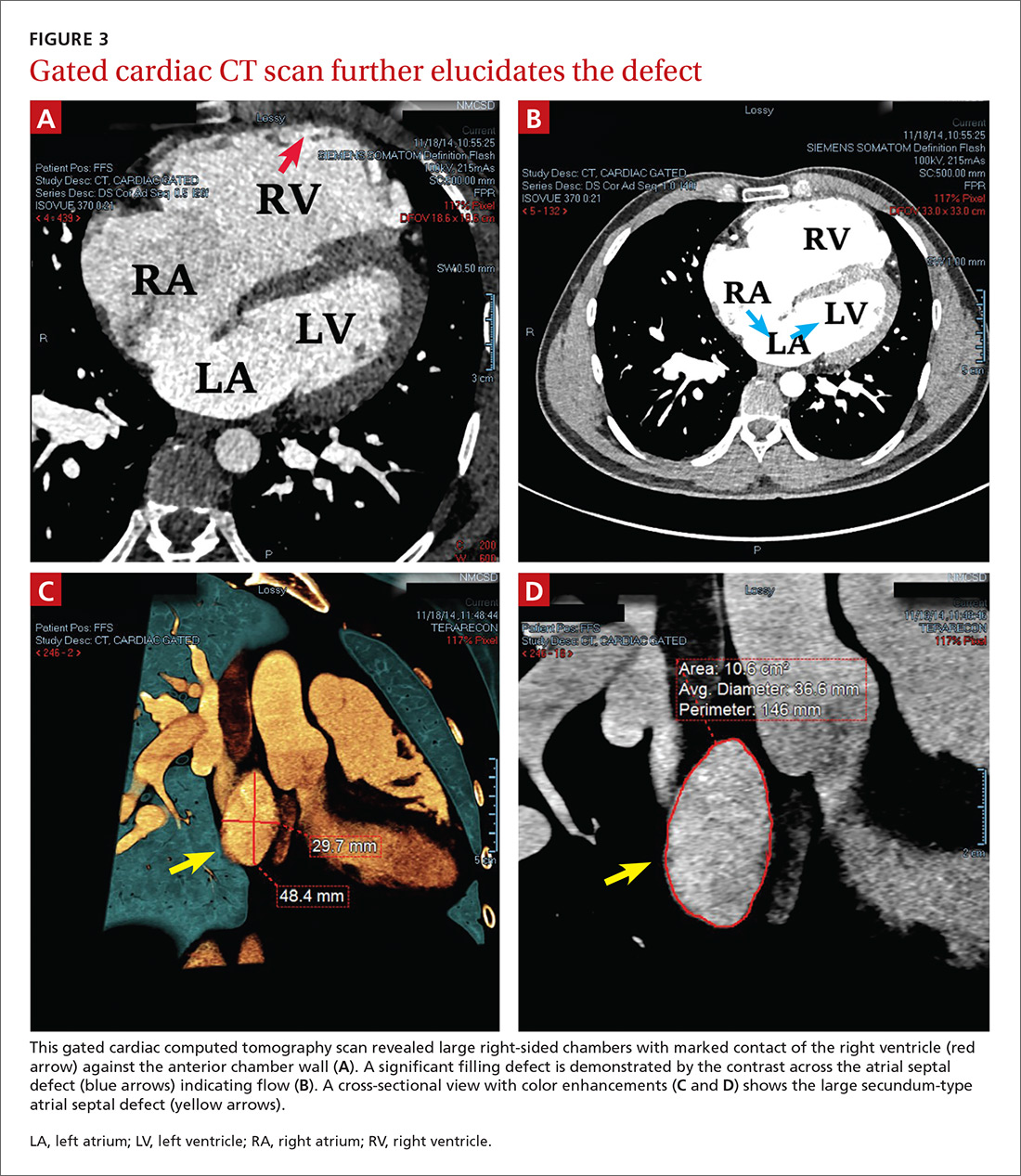

To further evaluate the cardiopulmonary findings, ultrasound studies (transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography) were performed. These demonstrated a very large secundum-type atrial septal defect (ASD), measuring at its largest point about 30 × 48 mm (FIGURE 2 and FIGURE 3C). Doppler flow analysis and a bubble study (VIDEOS 1 and 2) demonstrated significant shunting across the ASD. Gated cardiac computed tomography (CT) was also used to characterize the ASD (FIGURE 3). It revealed that the superior and posterior rims of the ASD were essentially absent and that the right atrium and ventricle were severely enlarged, while the left chambers were normal in size and function with an ejection fraction >55%. The notching of the R-waves of the inferior leads, seen in our patient’s EKG, is typically seen with large ASDs.1,2

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with color Doppler flow (red) demonstrated significant shunting across a large atrial septal defect (white box). The largest white dot is positioned near the center of the defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with a bubble study showed injected air bubbles traversing the atrial septal defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

DISCUSSION

ASDs are typically uncovered on exam via auscultation of heart sounds, which might reveal a split of the second heart sound (S2) and diastolic murmurs. ASDs are typically classified by size, and their management depends on this factor, along with the patient’s age and symptoms. In children with small defects (<6 mm), treatment usually consists of conservative observation, as more than half of these ASDs will spontaneously close.3 But, as children age, they are more likely to engage in exertional activity (work, recreational sports) and an unrepaired ASD may yield symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue, other cardiopulmonary strain). With such symptoms and when closure is not spontaneously achieved by adolescence or adulthood, an invasive approach is often necessary to correct the defect.

ASD repair. Traditionally, repair has involved some form of open thoracotomy. More recently, several minimally invasive techniques have been developed. Catheter-based device closure, in which a catheter is percutaneously guided to the defect and a patch is deployed to seal the ASD, is a technique that has been shown to successfully correct large ASDs of up to 40 mm in size.4 Robotic procedures have also been developed to correct ASDs through much smaller incisions.5 Both of these techniques require a significant rim of residual septal tissue around the defect.

Individualized approach. Since our patient had a rather large ASD that did not have sufficient residual septal rim tissue, percutaneous and robotic approaches were not feasible. Instead, he required more invasive cardiothoracic surgery. In cases such as this, the exact technique and type of incision (sternotomy vs access through the lateral chest wall) depend on age, gender, and the presence of other comorbidities.6

Our patient. Because there was concern that any approach other than a median one might not afford enough space to fix an ASD of such considerable size, our patient underwent a median sternotomy by a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon who specialized in these repairs (in children as well as young adults). During the procedure, the ASD was accessed and confirmed to be as large as predicted by diagnostic imaging. A surgical patch was sutured in place to correct the defect. There were no intra-operative or postop complications.

Four weeks later, the patient had a mild pericardial effusion that was managed medically with daily furosemide and aspirin. At his 8-week postop appointment, the fluid accumulation had resolved, and he was completely asymptomatic. The patient returned to full-time active duty in the US Navy.

Adults with rather large ASDs can present in a relatively asymptomatic manner and report none of the classic complaints (angina, dyspnea, fatigue). They may even engage in heavy exertional activity with no difficulty. The underlying defect may be discovered incidentally on exam by noting a split of the S2 on auscultation. If pulmonary hypertension exists, the clinician may also note a loud S2. An exam that raises suspicion for an ASD can then be followed by tests that solidify the diagnosis. Surgery is usually necessary to correct an ASD in an adult who is symptomatic or exhibits significant cardiopulmonary strain.

1. Heller J, Hagège AA, Besse B, et al. “Crochetage” (notch) on R wave in inferior limb leads: a new independent electrocardiographic sign of atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:877-882.

2. Kuijpers JM, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ. Secundum atrial septal defect in adults: a practical review and recent developments. Neth Heart J. 2015;23:205-211.

3. McMahon CJ, Feltes TF, Fraley JK, et al. Natural history of growth of secundum atrial septal defects and implications for transcatheter closure. Heart. 2002;87:256-259.

4. Lopez K, Dalvi BV, Balzer D, et al. Transcatheter closure of large secundum atrial septal defects using the 40 mm amplatzer septal occluder: results of an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:580-584.

5. Argenziano M, Oz MC, Kohmoto T, et al. Totally endoscopic atrial septal defect repair with robotic assistance. Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II191-II194.

6. Hopkins RA, Bert AA, Buchholz B, et al. Surgical patch closure of atrial septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2144-2149.

THE CASE

A 25-year-old man, who was an active duty US Navy sailor, went to his ship’s medical department complaining of a mild cough that he’d had for 2 days. He denied having any fevers, chills, night sweats, angina, or dyspnea. He said he hadn’t experienced any exertional fatigue or difficulty completing the rigorous physical tasks of his occupation as an engineman on the ship. The patient had no medical or surgical history of significance, and he wasn’t taking any medications or supplements.

On exam, he was not in acute distress and his vital signs were within normal limits. Auscultation revealed mild wheezing throughout the upper lung fields and loud heart sounds throughout his chest that were audible even with gentle contact of the stethoscope diaphragm. He had no discernible murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

In light of the unusually loud heart sounds heard on exam, we performed an electrocardiogram. The EKG revealed a normal sinus rhythm, slight right axis deviation indicated by tall R-waves in V1 (also suggestive of right ventricular hypertrophy), an incomplete right bundle branch block, and a crochetage sign (a notch in the R-waves of the inferior leads).1 A chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) revealed a normal-sized heart and dilated pulmonary vasculature suggestive of pulmonary hypertension.

THE DIAGNOSIS

To further evaluate the cardiopulmonary findings, ultrasound studies (transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography) were performed. These demonstrated a very large secundum-type atrial septal defect (ASD), measuring at its largest point about 30 × 48 mm (FIGURE 2 and FIGURE 3C). Doppler flow analysis and a bubble study (VIDEOS 1 and 2) demonstrated significant shunting across the ASD. Gated cardiac computed tomography (CT) was also used to characterize the ASD (FIGURE 3). It revealed that the superior and posterior rims of the ASD were essentially absent and that the right atrium and ventricle were severely enlarged, while the left chambers were normal in size and function with an ejection fraction >55%. The notching of the R-waves of the inferior leads, seen in our patient’s EKG, is typically seen with large ASDs.1,2

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with color Doppler flow (red) demonstrated significant shunting across a large atrial septal defect (white box). The largest white dot is positioned near the center of the defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with a bubble study showed injected air bubbles traversing the atrial septal defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

DISCUSSION

ASDs are typically uncovered on exam via auscultation of heart sounds, which might reveal a split of the second heart sound (S2) and diastolic murmurs. ASDs are typically classified by size, and their management depends on this factor, along with the patient’s age and symptoms. In children with small defects (<6 mm), treatment usually consists of conservative observation, as more than half of these ASDs will spontaneously close.3 But, as children age, they are more likely to engage in exertional activity (work, recreational sports) and an unrepaired ASD may yield symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue, other cardiopulmonary strain). With such symptoms and when closure is not spontaneously achieved by adolescence or adulthood, an invasive approach is often necessary to correct the defect.

ASD repair. Traditionally, repair has involved some form of open thoracotomy. More recently, several minimally invasive techniques have been developed. Catheter-based device closure, in which a catheter is percutaneously guided to the defect and a patch is deployed to seal the ASD, is a technique that has been shown to successfully correct large ASDs of up to 40 mm in size.4 Robotic procedures have also been developed to correct ASDs through much smaller incisions.5 Both of these techniques require a significant rim of residual septal tissue around the defect.

Individualized approach. Since our patient had a rather large ASD that did not have sufficient residual septal rim tissue, percutaneous and robotic approaches were not feasible. Instead, he required more invasive cardiothoracic surgery. In cases such as this, the exact technique and type of incision (sternotomy vs access through the lateral chest wall) depend on age, gender, and the presence of other comorbidities.6

Our patient. Because there was concern that any approach other than a median one might not afford enough space to fix an ASD of such considerable size, our patient underwent a median sternotomy by a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon who specialized in these repairs (in children as well as young adults). During the procedure, the ASD was accessed and confirmed to be as large as predicted by diagnostic imaging. A surgical patch was sutured in place to correct the defect. There were no intra-operative or postop complications.

Four weeks later, the patient had a mild pericardial effusion that was managed medically with daily furosemide and aspirin. At his 8-week postop appointment, the fluid accumulation had resolved, and he was completely asymptomatic. The patient returned to full-time active duty in the US Navy.

Adults with rather large ASDs can present in a relatively asymptomatic manner and report none of the classic complaints (angina, dyspnea, fatigue). They may even engage in heavy exertional activity with no difficulty. The underlying defect may be discovered incidentally on exam by noting a split of the S2 on auscultation. If pulmonary hypertension exists, the clinician may also note a loud S2. An exam that raises suspicion for an ASD can then be followed by tests that solidify the diagnosis. Surgery is usually necessary to correct an ASD in an adult who is symptomatic or exhibits significant cardiopulmonary strain.

THE CASE

A 25-year-old man, who was an active duty US Navy sailor, went to his ship’s medical department complaining of a mild cough that he’d had for 2 days. He denied having any fevers, chills, night sweats, angina, or dyspnea. He said he hadn’t experienced any exertional fatigue or difficulty completing the rigorous physical tasks of his occupation as an engineman on the ship. The patient had no medical or surgical history of significance, and he wasn’t taking any medications or supplements.

On exam, he was not in acute distress and his vital signs were within normal limits. Auscultation revealed mild wheezing throughout the upper lung fields and loud heart sounds throughout his chest that were audible even with gentle contact of the stethoscope diaphragm. He had no discernible murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

In light of the unusually loud heart sounds heard on exam, we performed an electrocardiogram. The EKG revealed a normal sinus rhythm, slight right axis deviation indicated by tall R-waves in V1 (also suggestive of right ventricular hypertrophy), an incomplete right bundle branch block, and a crochetage sign (a notch in the R-waves of the inferior leads).1 A chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) revealed a normal-sized heart and dilated pulmonary vasculature suggestive of pulmonary hypertension.

THE DIAGNOSIS

To further evaluate the cardiopulmonary findings, ultrasound studies (transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography) were performed. These demonstrated a very large secundum-type atrial septal defect (ASD), measuring at its largest point about 30 × 48 mm (FIGURE 2 and FIGURE 3C). Doppler flow analysis and a bubble study (VIDEOS 1 and 2) demonstrated significant shunting across the ASD. Gated cardiac computed tomography (CT) was also used to characterize the ASD (FIGURE 3). It revealed that the superior and posterior rims of the ASD were essentially absent and that the right atrium and ventricle were severely enlarged, while the left chambers were normal in size and function with an ejection fraction >55%. The notching of the R-waves of the inferior leads, seen in our patient’s EKG, is typically seen with large ASDs.1,2

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with color Doppler flow (red) demonstrated significant shunting across a large atrial septal defect (white box). The largest white dot is positioned near the center of the defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Transthoracic echocardiography with a bubble study showed injected air bubbles traversing the atrial septal defect.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

DISCUSSION

ASDs are typically uncovered on exam via auscultation of heart sounds, which might reveal a split of the second heart sound (S2) and diastolic murmurs. ASDs are typically classified by size, and their management depends on this factor, along with the patient’s age and symptoms. In children with small defects (<6 mm), treatment usually consists of conservative observation, as more than half of these ASDs will spontaneously close.3 But, as children age, they are more likely to engage in exertional activity (work, recreational sports) and an unrepaired ASD may yield symptoms (angina, dyspnea, fatigue, other cardiopulmonary strain). With such symptoms and when closure is not spontaneously achieved by adolescence or adulthood, an invasive approach is often necessary to correct the defect.

ASD repair. Traditionally, repair has involved some form of open thoracotomy. More recently, several minimally invasive techniques have been developed. Catheter-based device closure, in which a catheter is percutaneously guided to the defect and a patch is deployed to seal the ASD, is a technique that has been shown to successfully correct large ASDs of up to 40 mm in size.4 Robotic procedures have also been developed to correct ASDs through much smaller incisions.5 Both of these techniques require a significant rim of residual septal tissue around the defect.

Individualized approach. Since our patient had a rather large ASD that did not have sufficient residual septal rim tissue, percutaneous and robotic approaches were not feasible. Instead, he required more invasive cardiothoracic surgery. In cases such as this, the exact technique and type of incision (sternotomy vs access through the lateral chest wall) depend on age, gender, and the presence of other comorbidities.6

Our patient. Because there was concern that any approach other than a median one might not afford enough space to fix an ASD of such considerable size, our patient underwent a median sternotomy by a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon who specialized in these repairs (in children as well as young adults). During the procedure, the ASD was accessed and confirmed to be as large as predicted by diagnostic imaging. A surgical patch was sutured in place to correct the defect. There were no intra-operative or postop complications.

Four weeks later, the patient had a mild pericardial effusion that was managed medically with daily furosemide and aspirin. At his 8-week postop appointment, the fluid accumulation had resolved, and he was completely asymptomatic. The patient returned to full-time active duty in the US Navy.

Adults with rather large ASDs can present in a relatively asymptomatic manner and report none of the classic complaints (angina, dyspnea, fatigue). They may even engage in heavy exertional activity with no difficulty. The underlying defect may be discovered incidentally on exam by noting a split of the S2 on auscultation. If pulmonary hypertension exists, the clinician may also note a loud S2. An exam that raises suspicion for an ASD can then be followed by tests that solidify the diagnosis. Surgery is usually necessary to correct an ASD in an adult who is symptomatic or exhibits significant cardiopulmonary strain.

1. Heller J, Hagège AA, Besse B, et al. “Crochetage” (notch) on R wave in inferior limb leads: a new independent electrocardiographic sign of atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:877-882.

2. Kuijpers JM, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ. Secundum atrial septal defect in adults: a practical review and recent developments. Neth Heart J. 2015;23:205-211.

3. McMahon CJ, Feltes TF, Fraley JK, et al. Natural history of growth of secundum atrial septal defects and implications for transcatheter closure. Heart. 2002;87:256-259.

4. Lopez K, Dalvi BV, Balzer D, et al. Transcatheter closure of large secundum atrial septal defects using the 40 mm amplatzer septal occluder: results of an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:580-584.

5. Argenziano M, Oz MC, Kohmoto T, et al. Totally endoscopic atrial septal defect repair with robotic assistance. Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II191-II194.

6. Hopkins RA, Bert AA, Buchholz B, et al. Surgical patch closure of atrial septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2144-2149.

1. Heller J, Hagège AA, Besse B, et al. “Crochetage” (notch) on R wave in inferior limb leads: a new independent electrocardiographic sign of atrial septal defect. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:877-882.

2. Kuijpers JM, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ. Secundum atrial septal defect in adults: a practical review and recent developments. Neth Heart J. 2015;23:205-211.

3. McMahon CJ, Feltes TF, Fraley JK, et al. Natural history of growth of secundum atrial septal defects and implications for transcatheter closure. Heart. 2002;87:256-259.

4. Lopez K, Dalvi BV, Balzer D, et al. Transcatheter closure of large secundum atrial septal defects using the 40 mm amplatzer septal occluder: results of an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:580-584.

5. Argenziano M, Oz MC, Kohmoto T, et al. Totally endoscopic atrial septal defect repair with robotic assistance. Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II191-II194.

6. Hopkins RA, Bert AA, Buchholz B, et al. Surgical patch closure of atrial septal defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2144-2149.

Elevated serum alkaline phosphatase • generalized pruritus • Dx?

THE CASE

A 34-year-old woman was referred to the hepatology clinic for evaluation of an increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level. She was gravida 5 and in her 38th week of gestation. Her obstetric history was significant for 2 uncomplicated spontaneous term vaginal deliveries resulting in live births and 2 spontaneous abortions. The patient reported generalized pruritus for 2 months prior to the visit. She had no comorbidities and denied any other symptoms. She reported no family history of liver disease or complications during pregnancy in relatives. The patient did not smoke or drink, and had come to our hospital for her prenatal care visits.

The physical exam revealed normal vital signs, no jaundice, a gravid uterus, and acanthosis nigricans on the neck and axilla with scattered excoriations on the arms, legs, and abdomen. Her serum ALP level was 1093 U/L (normal: 50-136 U/L). Immediately before this pregnancy, her serum ALP had been normal at 95 U/L, but it had since been increasing with a peak value of 1134 U/L by 37 weeks’ gestation. Serum transaminase activities and albumin and bilirubin concentrations were normal, as was her prothrombin time. The rest of her lab tests were also normal, including her fasting serum bile acid concentration, which was 9 mcmol/L (normal: 4.5-19.2 mcmol/L).

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although cholestasis of pregnancy was considered, the patient’s markedly elevated serum ALP level suggested the presence of another cholestatic liver disease. Additional tests revealed an antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) titer of 1:320 (normal: <1:20) and immunoglobulin A, G, and M levels within normal limits. Accordingly, we diagnosed primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

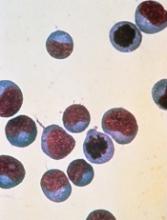

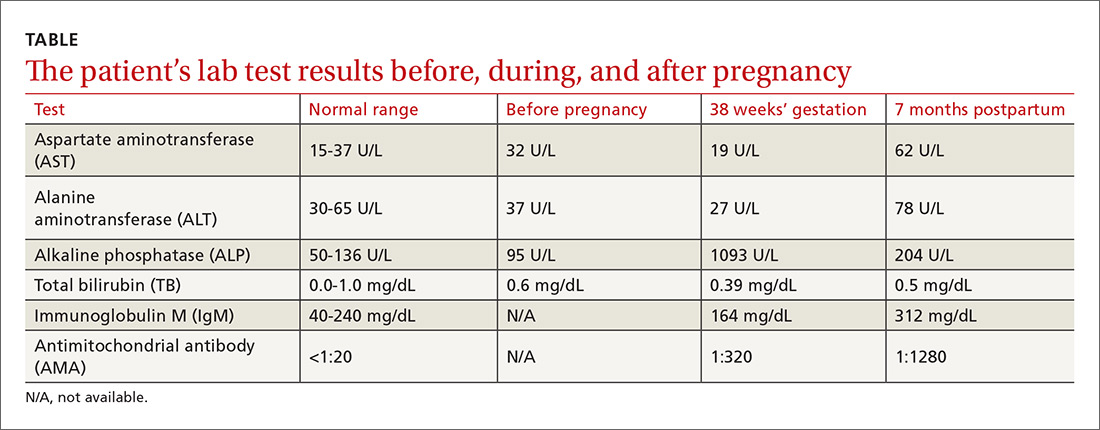

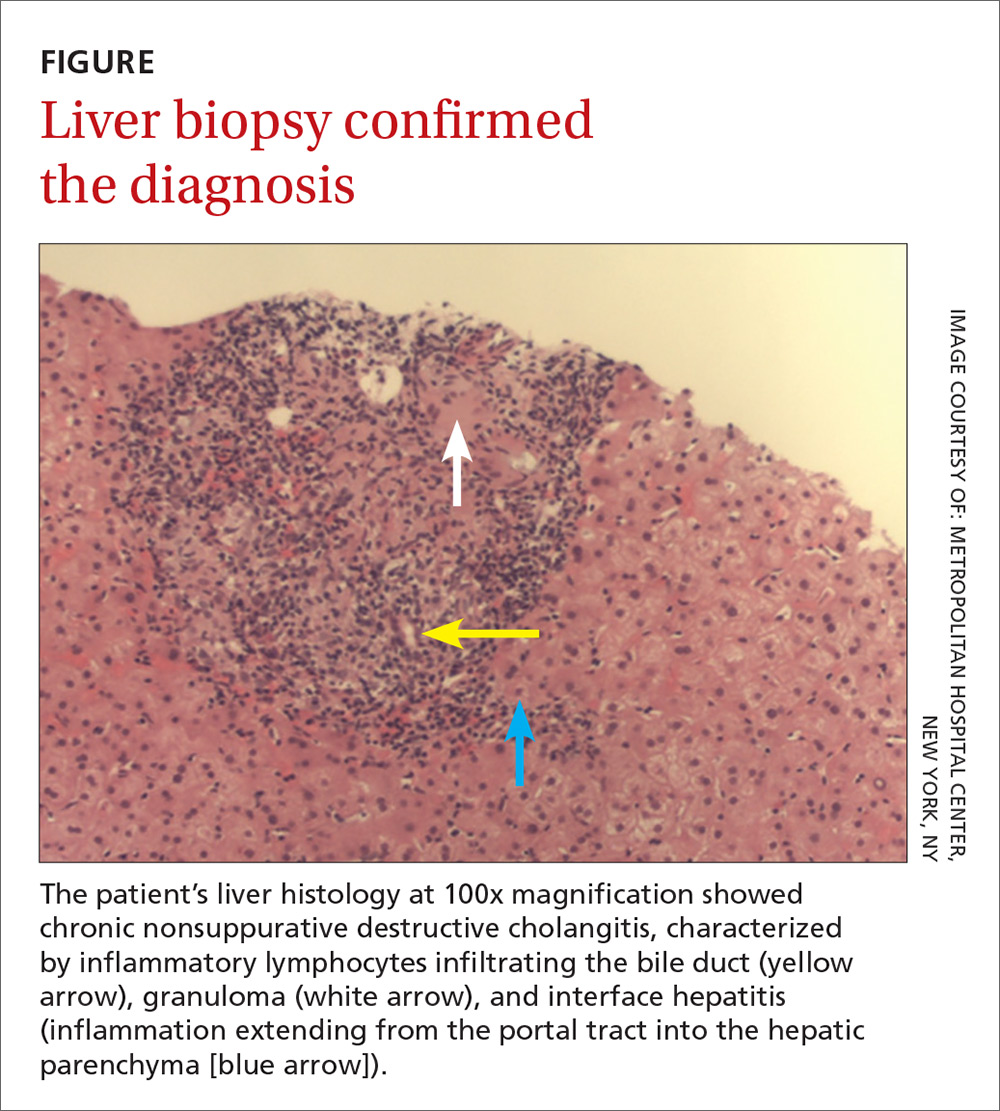

The patient delivered vaginally at another institution uneventfully and returned to the hepatology clinic 7 months postpartum. Repeat laboratory tests (TABLE) revealed increased AMA titer and immunoglobulin M levels from baseline (38 weeks’ gestation). The physical exam was notable for the absence of both jaundice and stigmata of chronic liver disease. A liver ultrasound was normal. The patient still reported pruritus, as well as a new symptom—fatigue. A liver biopsy was performed, and findings were consistent with PBC, stage 1 (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

PBC, historically known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic, likely immune-mediated, cholestatic liver disease characterized by the progressive inflammatory destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts. The disease has a female to male predominance of 10:1, with age of diagnosis most often between 40 and 50 years, although about a quarter of female patients present during their reproductive years.1,2

PBC in pregnant women

During pregnancy, the profound physiologic changes and adaptations in the endocrine, metabolic, and immune systems that are necessary for normal fetal development can affect the maternal hepatobiliary system. In patients with prior autoimmune liver disease, the liver is known to adapt itself to these physiologic changes by entering a state of immune tolerance. This is induced by relative hypercortisolism, a shift from predominantly cell-mediated immunity to humoral immunity, and inhibition of T-cell activation. These changes can result in remission of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and postpartum flaring when these protective mechanisms are lost (although neither remission nor postpartum flaring occurred in this patient’s case).1-3

While a well-compensated state is associated with better fetal and maternal outcomes than a decompensated condition, cirrhosis is not a contraindication to pregnancy. Vaginal delivery is generally safe for patients with PBC, and studies have reported no childbirth complications or adverse maternal outcomes.1,3,4

The approved treatment for PBC, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), was classified as a category B agent according to the Food and Drug Administration’s now defunct classification system for drugs used during pregnancy and lactation. It’s considered to be the treatment of choice for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, but there are no recommendations for its use in pregnant patients with PBC. Several studies have observed no significant teratogenic effect in babies whose mothers were treated with UDCA for PBC during pregnancy.1-4 Postpartum, 60% to 70% of PBC patients have been reported to exhibit biochemical disease activity,1,3 and in one case, a liver transplant was required due to liver failure.5

Look for AMA, elevated ALP

The diagnosis of the disease in this case was made by the detection of AMA, which has a specificity of 98% for PBC. However, isolated instances of the presence of AMA are not uncommon; they have been documented in up to 64% of healthy individuals.6 In addition, while one would expect to see a 2- to 4-fold rise in ALP levels during pregnancy (due to placental isoenzyme production),2,7 our patient’s serum ALP level was much higher, suggesting probable cholestatic liver disease such as PBC. The diagnosis in this case was confirmed by liver biopsy.

Our patient was started on UDCA 13 to 15 mg/kg/d. She remained clinically stable at subsequent follow-ups.

THE TAKEAWAY

Typically seen in middle-aged women, PBC can be detected by the presence of AMA and elevated ALP levels. Pregnant patients with chronic liver disease, including PBC, should be followed by a hepatologist and a high-risk obstetrician. They should be carefully monitored and frequently reassessed throughout the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period, even though studies have documented favorable outcomes for both mother and baby.1,3,4

1. Trivedi PJ, Kumagi T, Al-Harthy N, et al. Good maternal and fetal outcomes for pregnant women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1179-1185.

2. Marchioni Beery RM, Vaziri H, Forouhar F. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review featuring a women’s health perspective. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:266-284.

3. Efe C, Kahramanoğlu-Aksoy E, Yilmaz B, et al. Pregnancy in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:931-935.

4. Floreani A, Infantolino C, Franceschet I, et al. Pregnancy and primary biliary cirrhosis: a case control study. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;48:236-242.

5. Rabinovitz M, Appasamy R, Finkelstein S. Primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosed during pregnancy. Does it have a different outcome? Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:571-574.

6. Carey EJ, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386:1565-1575.

7. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Gynecology. Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, et al, eds. The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011.

THE CASE

A 34-year-old woman was referred to the hepatology clinic for evaluation of an increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level. She was gravida 5 and in her 38th week of gestation. Her obstetric history was significant for 2 uncomplicated spontaneous term vaginal deliveries resulting in live births and 2 spontaneous abortions. The patient reported generalized pruritus for 2 months prior to the visit. She had no comorbidities and denied any other symptoms. She reported no family history of liver disease or complications during pregnancy in relatives. The patient did not smoke or drink, and had come to our hospital for her prenatal care visits.

The physical exam revealed normal vital signs, no jaundice, a gravid uterus, and acanthosis nigricans on the neck and axilla with scattered excoriations on the arms, legs, and abdomen. Her serum ALP level was 1093 U/L (normal: 50-136 U/L). Immediately before this pregnancy, her serum ALP had been normal at 95 U/L, but it had since been increasing with a peak value of 1134 U/L by 37 weeks’ gestation. Serum transaminase activities and albumin and bilirubin concentrations were normal, as was her prothrombin time. The rest of her lab tests were also normal, including her fasting serum bile acid concentration, which was 9 mcmol/L (normal: 4.5-19.2 mcmol/L).

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although cholestasis of pregnancy was considered, the patient’s markedly elevated serum ALP level suggested the presence of another cholestatic liver disease. Additional tests revealed an antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) titer of 1:320 (normal: <1:20) and immunoglobulin A, G, and M levels within normal limits. Accordingly, we diagnosed primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

The patient delivered vaginally at another institution uneventfully and returned to the hepatology clinic 7 months postpartum. Repeat laboratory tests (TABLE) revealed increased AMA titer and immunoglobulin M levels from baseline (38 weeks’ gestation). The physical exam was notable for the absence of both jaundice and stigmata of chronic liver disease. A liver ultrasound was normal. The patient still reported pruritus, as well as a new symptom—fatigue. A liver biopsy was performed, and findings were consistent with PBC, stage 1 (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

PBC, historically known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic, likely immune-mediated, cholestatic liver disease characterized by the progressive inflammatory destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts. The disease has a female to male predominance of 10:1, with age of diagnosis most often between 40 and 50 years, although about a quarter of female patients present during their reproductive years.1,2

PBC in pregnant women

During pregnancy, the profound physiologic changes and adaptations in the endocrine, metabolic, and immune systems that are necessary for normal fetal development can affect the maternal hepatobiliary system. In patients with prior autoimmune liver disease, the liver is known to adapt itself to these physiologic changes by entering a state of immune tolerance. This is induced by relative hypercortisolism, a shift from predominantly cell-mediated immunity to humoral immunity, and inhibition of T-cell activation. These changes can result in remission of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and postpartum flaring when these protective mechanisms are lost (although neither remission nor postpartum flaring occurred in this patient’s case).1-3

While a well-compensated state is associated with better fetal and maternal outcomes than a decompensated condition, cirrhosis is not a contraindication to pregnancy. Vaginal delivery is generally safe for patients with PBC, and studies have reported no childbirth complications or adverse maternal outcomes.1,3,4

The approved treatment for PBC, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), was classified as a category B agent according to the Food and Drug Administration’s now defunct classification system for drugs used during pregnancy and lactation. It’s considered to be the treatment of choice for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, but there are no recommendations for its use in pregnant patients with PBC. Several studies have observed no significant teratogenic effect in babies whose mothers were treated with UDCA for PBC during pregnancy.1-4 Postpartum, 60% to 70% of PBC patients have been reported to exhibit biochemical disease activity,1,3 and in one case, a liver transplant was required due to liver failure.5

Look for AMA, elevated ALP

The diagnosis of the disease in this case was made by the detection of AMA, which has a specificity of 98% for PBC. However, isolated instances of the presence of AMA are not uncommon; they have been documented in up to 64% of healthy individuals.6 In addition, while one would expect to see a 2- to 4-fold rise in ALP levels during pregnancy (due to placental isoenzyme production),2,7 our patient’s serum ALP level was much higher, suggesting probable cholestatic liver disease such as PBC. The diagnosis in this case was confirmed by liver biopsy.

Our patient was started on UDCA 13 to 15 mg/kg/d. She remained clinically stable at subsequent follow-ups.

THE TAKEAWAY

Typically seen in middle-aged women, PBC can be detected by the presence of AMA and elevated ALP levels. Pregnant patients with chronic liver disease, including PBC, should be followed by a hepatologist and a high-risk obstetrician. They should be carefully monitored and frequently reassessed throughout the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period, even though studies have documented favorable outcomes for both mother and baby.1,3,4

THE CASE

A 34-year-old woman was referred to the hepatology clinic for evaluation of an increased serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level. She was gravida 5 and in her 38th week of gestation. Her obstetric history was significant for 2 uncomplicated spontaneous term vaginal deliveries resulting in live births and 2 spontaneous abortions. The patient reported generalized pruritus for 2 months prior to the visit. She had no comorbidities and denied any other symptoms. She reported no family history of liver disease or complications during pregnancy in relatives. The patient did not smoke or drink, and had come to our hospital for her prenatal care visits.

The physical exam revealed normal vital signs, no jaundice, a gravid uterus, and acanthosis nigricans on the neck and axilla with scattered excoriations on the arms, legs, and abdomen. Her serum ALP level was 1093 U/L (normal: 50-136 U/L). Immediately before this pregnancy, her serum ALP had been normal at 95 U/L, but it had since been increasing with a peak value of 1134 U/L by 37 weeks’ gestation. Serum transaminase activities and albumin and bilirubin concentrations were normal, as was her prothrombin time. The rest of her lab tests were also normal, including her fasting serum bile acid concentration, which was 9 mcmol/L (normal: 4.5-19.2 mcmol/L).

THE DIAGNOSIS

Although cholestasis of pregnancy was considered, the patient’s markedly elevated serum ALP level suggested the presence of another cholestatic liver disease. Additional tests revealed an antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) titer of 1:320 (normal: <1:20) and immunoglobulin A, G, and M levels within normal limits. Accordingly, we diagnosed primary biliary cholangitis (PBC).

The patient delivered vaginally at another institution uneventfully and returned to the hepatology clinic 7 months postpartum. Repeat laboratory tests (TABLE) revealed increased AMA titer and immunoglobulin M levels from baseline (38 weeks’ gestation). The physical exam was notable for the absence of both jaundice and stigmata of chronic liver disease. A liver ultrasound was normal. The patient still reported pruritus, as well as a new symptom—fatigue. A liver biopsy was performed, and findings were consistent with PBC, stage 1 (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

PBC, historically known as primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic, likely immune-mediated, cholestatic liver disease characterized by the progressive inflammatory destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts. The disease has a female to male predominance of 10:1, with age of diagnosis most often between 40 and 50 years, although about a quarter of female patients present during their reproductive years.1,2

PBC in pregnant women

During pregnancy, the profound physiologic changes and adaptations in the endocrine, metabolic, and immune systems that are necessary for normal fetal development can affect the maternal hepatobiliary system. In patients with prior autoimmune liver disease, the liver is known to adapt itself to these physiologic changes by entering a state of immune tolerance. This is induced by relative hypercortisolism, a shift from predominantly cell-mediated immunity to humoral immunity, and inhibition of T-cell activation. These changes can result in remission of autoimmune disease activity during pregnancy and postpartum flaring when these protective mechanisms are lost (although neither remission nor postpartum flaring occurred in this patient’s case).1-3

While a well-compensated state is associated with better fetal and maternal outcomes than a decompensated condition, cirrhosis is not a contraindication to pregnancy. Vaginal delivery is generally safe for patients with PBC, and studies have reported no childbirth complications or adverse maternal outcomes.1,3,4

The approved treatment for PBC, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), was classified as a category B agent according to the Food and Drug Administration’s now defunct classification system for drugs used during pregnancy and lactation. It’s considered to be the treatment of choice for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, but there are no recommendations for its use in pregnant patients with PBC. Several studies have observed no significant teratogenic effect in babies whose mothers were treated with UDCA for PBC during pregnancy.1-4 Postpartum, 60% to 70% of PBC patients have been reported to exhibit biochemical disease activity,1,3 and in one case, a liver transplant was required due to liver failure.5

Look for AMA, elevated ALP

The diagnosis of the disease in this case was made by the detection of AMA, which has a specificity of 98% for PBC. However, isolated instances of the presence of AMA are not uncommon; they have been documented in up to 64% of healthy individuals.6 In addition, while one would expect to see a 2- to 4-fold rise in ALP levels during pregnancy (due to placental isoenzyme production),2,7 our patient’s serum ALP level was much higher, suggesting probable cholestatic liver disease such as PBC. The diagnosis in this case was confirmed by liver biopsy.

Our patient was started on UDCA 13 to 15 mg/kg/d. She remained clinically stable at subsequent follow-ups.

THE TAKEAWAY

Typically seen in middle-aged women, PBC can be detected by the presence of AMA and elevated ALP levels. Pregnant patients with chronic liver disease, including PBC, should be followed by a hepatologist and a high-risk obstetrician. They should be carefully monitored and frequently reassessed throughout the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period, even though studies have documented favorable outcomes for both mother and baby.1,3,4

1. Trivedi PJ, Kumagi T, Al-Harthy N, et al. Good maternal and fetal outcomes for pregnant women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1179-1185.

2. Marchioni Beery RM, Vaziri H, Forouhar F. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review featuring a women’s health perspective. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:266-284.

3. Efe C, Kahramanoğlu-Aksoy E, Yilmaz B, et al. Pregnancy in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:931-935.

4. Floreani A, Infantolino C, Franceschet I, et al. Pregnancy and primary biliary cirrhosis: a case control study. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;48:236-242.

5. Rabinovitz M, Appasamy R, Finkelstein S. Primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosed during pregnancy. Does it have a different outcome? Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:571-574.

6. Carey EJ, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386:1565-1575.

7. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Gynecology. Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, et al, eds. The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011.

1. Trivedi PJ, Kumagi T, Al-Harthy N, et al. Good maternal and fetal outcomes for pregnant women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1179-1185.

2. Marchioni Beery RM, Vaziri H, Forouhar F. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review featuring a women’s health perspective. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:266-284.

3. Efe C, Kahramanoğlu-Aksoy E, Yilmaz B, et al. Pregnancy in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:931-935.

4. Floreani A, Infantolino C, Franceschet I, et al. Pregnancy and primary biliary cirrhosis: a case control study. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;48:236-242.

5. Rabinovitz M, Appasamy R, Finkelstein S. Primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosed during pregnancy. Does it have a different outcome? Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:571-574.

6. Carey EJ, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386:1565-1575.

7. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Gynecology. Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, et al, eds. The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011.

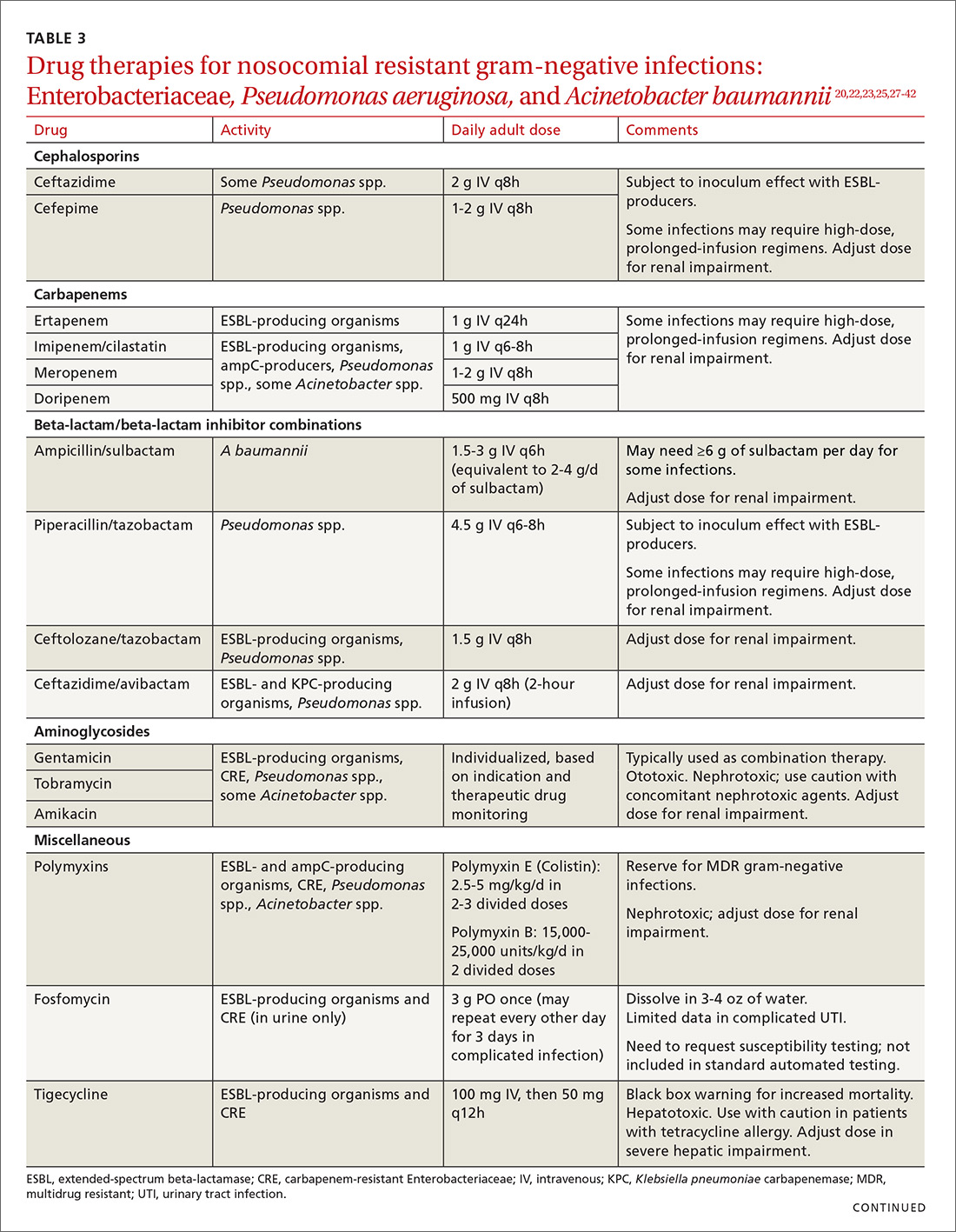

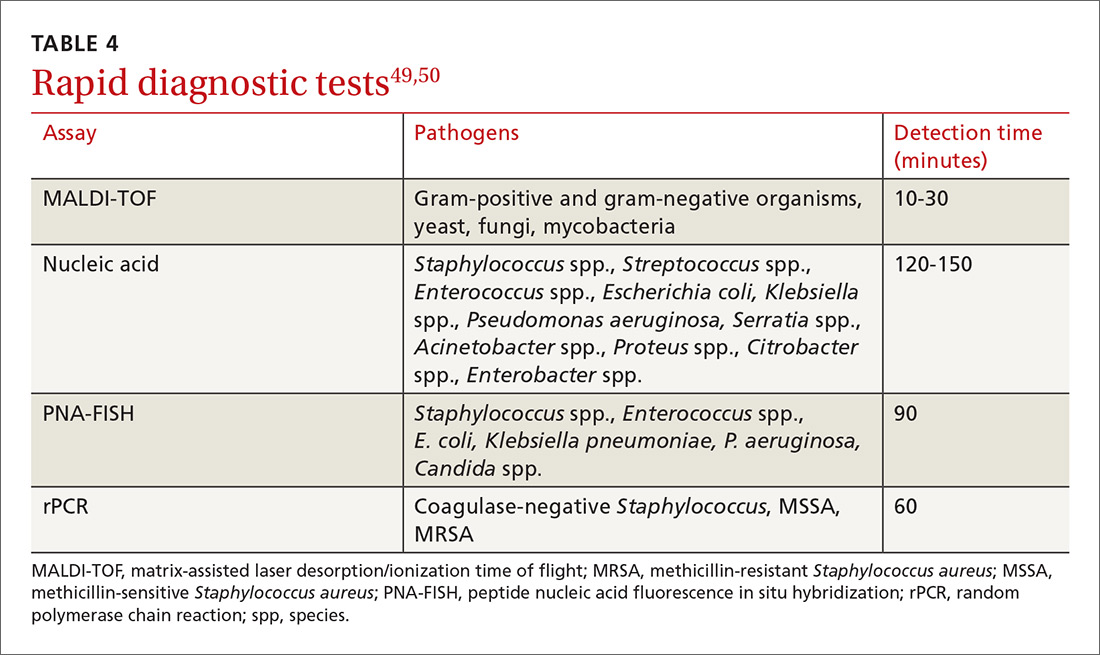

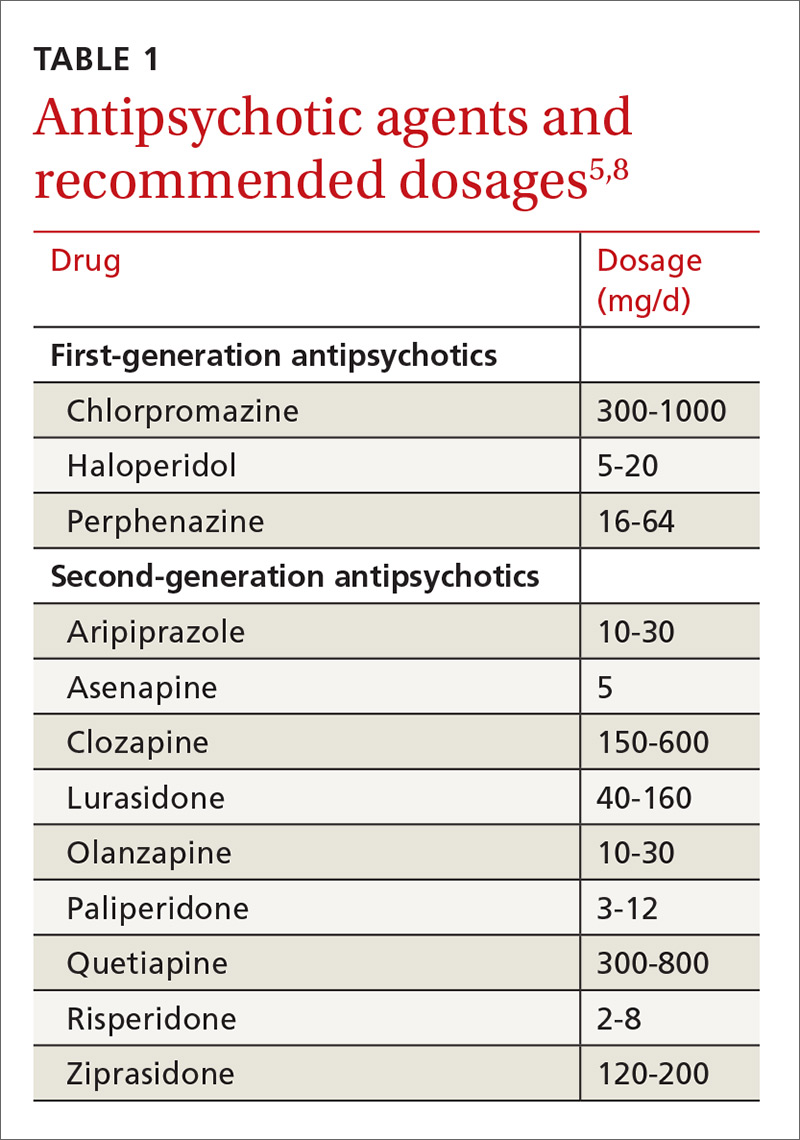

Inpatient antibiotic resistance: Everyone’s problem

CASE

A 68-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital from home with acute onset, unrelenting, upper abdominal pain radiating to the back and nausea/vomiting. Her medical history includes bile duct obstruction secondary to gall stones, which was managed in another facility 6 days earlier with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and stenting. The patient has type 2 diabetes (managed with metformin and glargine insulin), hypertension (managed with lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide), and cholesterolemia (managed with atorvastatin).

On admission, the patient's white blood cell count is 14.7 x 103 cells/mm3, heart rate is 100 bpm, blood pressure is 90/68 mm Hg, and temperature is 101.5° F. Serum amylase and lipase are 3 and 2 times the upper limit of normal, respectively. A working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis with sepsis is made. Blood cultures are drawn. A computed tomography scan confirms acute pancreatitis. She receives one dose of meropenem, is started on intravenous fluids and morphine, and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

Her ICU course is complicated by worsening sepsis despite aggressive fluid resuscitation, nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. On post-admission Day 2, blood culture results reveal Escherichia coli that is resistant to gentamicin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline. Additional susceptibility testing is ordered.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conservatively estimates that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are responsible for 2 billion infections annually, resulting in approximately 23,000 deaths and $20 billion in excess health care expenditures annually.1 Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria typically require longer hospitalizations, more expensive drug therapies, and additional follow-up visits.1 They also result in greater morbidity and mortality compared with similar infections involving non-resistant bacteria.1 To compound the problem, antibiotic development has steadily declined over the last 3 decades, with few novel antimicrobials developed in recent years.2 The most recently approved antibiotics with new mechanisms of action were linezolid in 2000 and daptomycin in 2003, preceded by the carbapenems 15 years earlier. (See “New antimicrobials in the pipeline.”)

New antimicrobials in the pipeline

The Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act was signed into law in 2012, creating a new designation—qualified infectious diseases products (QIDPs)—for antibiotics in development for serious or life-threatening infections (https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ144/PLAW-112publ144.pdf). QIDPs are granted expedited FDA approval and an additional 5 years of patent exclusivity in order to encourage new antimicrobial development.

Five antibiotics have been approved with the QIDP designation: tedizolid, dalbavancin, oritavancin, ceftolozane/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/avibactam, and 20 more agents are in development including a new fluoroquinolone, delafloxacin, for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections including those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and a new tetracycline, eravacycline, for complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated UTIs. Eravacycline has in vitro activity against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, MRSA, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, and multidrug-resistant A. baumannii. Both drugs will be available in intravenous and oral formulations.

Greater efforts aimed at using antimicrobials sparingly and appropriately, as well as developing new antimicrobials with activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, are ultimately needed to address the threat of antimicrobial resistance. This article describes the evidence-based management of inpatient infections caused by resistant bacteria and the role family physicians (FPs) can play in reducing further development of resistance through antimicrobial stewardship practices.

Health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus