User login

Menopause accelerates RA functional decline

Rheumatoid arthritis gets worse after menopause, likely because of lower hormone levels, according to a review of 8,189 women in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, published recently in Rheumatology.

The investigators compared scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) between 2,005 premenopausal women with a mean age of 39.7 years; 611 women transitioning through menopause with a mean age of 50.7 years, and 5,573 postmenopausal women with a mean age of 62.3 years. As participants in the data bank, the women completed a questionnaire at regular intervals that included the HAQ, which is a 3-point measure of functional status, with 0 meaning no disability and 3 severe disability. They had all been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis prior to menopause.

“Women with RA have better functional status prior to menopause, even after controlling for covariates,” and after menopause, functional decline worsens and accelerates, said investigators led by Elizabeth Mollard, PhD, a nurse practitioner at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Lincoln. The findings were “robust even after adjustment for other significant factors.”

The team also found that functional decline was less in women who had a longer reproductive life; had ever been pregnant; or had ever used hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

The findings support the notion that hormone exposure plays a role in RA severity, at least in women. It’s well known that RA activity trails off when women are pregnant, but increases after delivery, when hormone levels are returning to baseline. It’s also known that women who go through menopause early are at greater risk for developing RA. Longer reproductive life, pregnancy, and HRT use, meanwhile, all increase women’s hormonal exposure and were protective in the study.

“Women have changes in disease development and progression surrounding reproductive and hormonal events. ... Our results suggest further study on hormonal involvement in functional decline in women with RA,” the investigators said.

Menopausal stage was determined by survey response. Pregnant women and those with hysterectomies were excluded from the study, as were those who went through menopause before the age of 40 years, and those over the age of 55 who had not reported a menstruation cessation date.

There was no external funding for the work. Dr. Mollard had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollard E et. al. Rheumatology. 2018 Jan 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex526

Rheumatoid arthritis gets worse after menopause, likely because of lower hormone levels, according to a review of 8,189 women in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, published recently in Rheumatology.

The investigators compared scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) between 2,005 premenopausal women with a mean age of 39.7 years; 611 women transitioning through menopause with a mean age of 50.7 years, and 5,573 postmenopausal women with a mean age of 62.3 years. As participants in the data bank, the women completed a questionnaire at regular intervals that included the HAQ, which is a 3-point measure of functional status, with 0 meaning no disability and 3 severe disability. They had all been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis prior to menopause.

“Women with RA have better functional status prior to menopause, even after controlling for covariates,” and after menopause, functional decline worsens and accelerates, said investigators led by Elizabeth Mollard, PhD, a nurse practitioner at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Lincoln. The findings were “robust even after adjustment for other significant factors.”

The team also found that functional decline was less in women who had a longer reproductive life; had ever been pregnant; or had ever used hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

The findings support the notion that hormone exposure plays a role in RA severity, at least in women. It’s well known that RA activity trails off when women are pregnant, but increases after delivery, when hormone levels are returning to baseline. It’s also known that women who go through menopause early are at greater risk for developing RA. Longer reproductive life, pregnancy, and HRT use, meanwhile, all increase women’s hormonal exposure and were protective in the study.

“Women have changes in disease development and progression surrounding reproductive and hormonal events. ... Our results suggest further study on hormonal involvement in functional decline in women with RA,” the investigators said.

Menopausal stage was determined by survey response. Pregnant women and those with hysterectomies were excluded from the study, as were those who went through menopause before the age of 40 years, and those over the age of 55 who had not reported a menstruation cessation date.

There was no external funding for the work. Dr. Mollard had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollard E et. al. Rheumatology. 2018 Jan 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex526

Rheumatoid arthritis gets worse after menopause, likely because of lower hormone levels, according to a review of 8,189 women in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, published recently in Rheumatology.

The investigators compared scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) between 2,005 premenopausal women with a mean age of 39.7 years; 611 women transitioning through menopause with a mean age of 50.7 years, and 5,573 postmenopausal women with a mean age of 62.3 years. As participants in the data bank, the women completed a questionnaire at regular intervals that included the HAQ, which is a 3-point measure of functional status, with 0 meaning no disability and 3 severe disability. They had all been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis prior to menopause.

“Women with RA have better functional status prior to menopause, even after controlling for covariates,” and after menopause, functional decline worsens and accelerates, said investigators led by Elizabeth Mollard, PhD, a nurse practitioner at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Lincoln. The findings were “robust even after adjustment for other significant factors.”

The team also found that functional decline was less in women who had a longer reproductive life; had ever been pregnant; or had ever used hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

The findings support the notion that hormone exposure plays a role in RA severity, at least in women. It’s well known that RA activity trails off when women are pregnant, but increases after delivery, when hormone levels are returning to baseline. It’s also known that women who go through menopause early are at greater risk for developing RA. Longer reproductive life, pregnancy, and HRT use, meanwhile, all increase women’s hormonal exposure and were protective in the study.

“Women have changes in disease development and progression surrounding reproductive and hormonal events. ... Our results suggest further study on hormonal involvement in functional decline in women with RA,” the investigators said.

Menopausal stage was determined by survey response. Pregnant women and those with hysterectomies were excluded from the study, as were those who went through menopause before the age of 40 years, and those over the age of 55 who had not reported a menstruation cessation date.

There was no external funding for the work. Dr. Mollard had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mollard E et. al. Rheumatology. 2018 Jan 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex526

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: HAQ scores were 0.68 points higher in postmenopausal women, compared with premenopausal women of the same age.

Study details: Review of 8,189 women in the National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases.

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the work. The lead investigator had no disclosures.

Source: Mollard E et. al. Rheumatology. 2018 Jan 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex526

Hospitals filling as flu season worsens

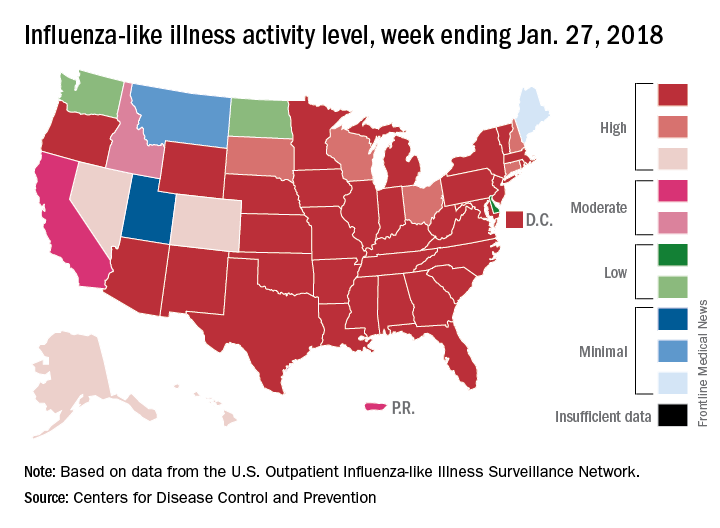

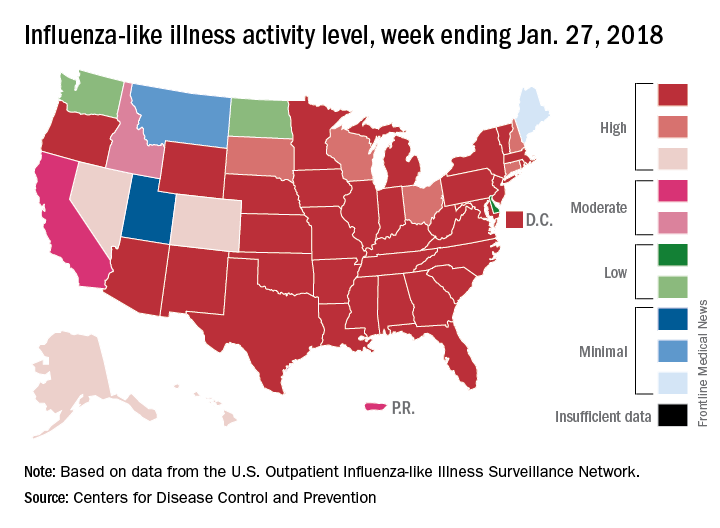

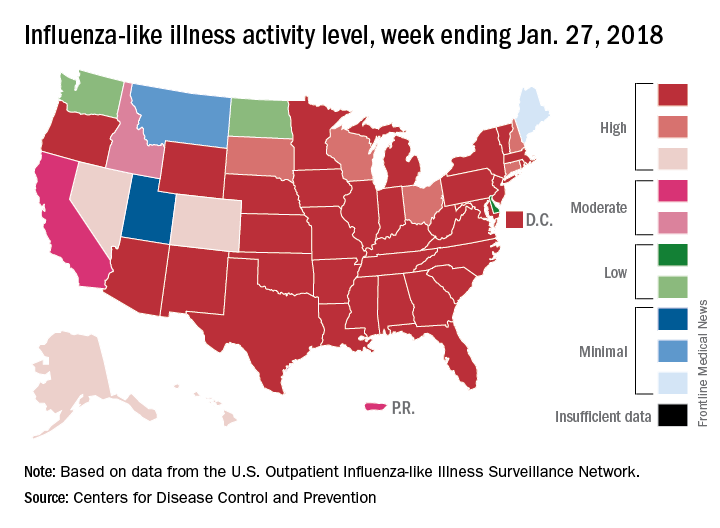

Through the last full week of January, the cumulative “hospitalization rate is the highest we’ve seen,” acting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Anne Schuchat, MD, said. For the current season so far, the hospitalization rate stands at 51.4 per 100,000 population, putting it on pace to top the total of 710,000 flu-related admissions that occurred during the 2014-2015 season, she said in a weekly briefing Feb. 2.

Flu-related pediatric deaths also took a big jump for the week as another 16 were reported, which brings the total for the season to 53. Of the children who have died so far, only 20% were vaccinated, said Dan Jernigan, MD, MPH, director of the influenza division at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta. He also noted that half of the children who have been hospitalized did not had an underlying condition.

The one bit of good news for the week was that activity in the West seems to be easing up, Dr. Schuchat said. The geographic spread of ILI was reported as widespread in 48 states, which is down from 49 the previous week because Oregon dropped off the list. To go along with that, the ILI activity level in California has dropped 2 weeks in a row and now stands at level 7, the CDC data show.

Through the last full week of January, the cumulative “hospitalization rate is the highest we’ve seen,” acting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Anne Schuchat, MD, said. For the current season so far, the hospitalization rate stands at 51.4 per 100,000 population, putting it on pace to top the total of 710,000 flu-related admissions that occurred during the 2014-2015 season, she said in a weekly briefing Feb. 2.

Flu-related pediatric deaths also took a big jump for the week as another 16 were reported, which brings the total for the season to 53. Of the children who have died so far, only 20% were vaccinated, said Dan Jernigan, MD, MPH, director of the influenza division at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta. He also noted that half of the children who have been hospitalized did not had an underlying condition.

The one bit of good news for the week was that activity in the West seems to be easing up, Dr. Schuchat said. The geographic spread of ILI was reported as widespread in 48 states, which is down from 49 the previous week because Oregon dropped off the list. To go along with that, the ILI activity level in California has dropped 2 weeks in a row and now stands at level 7, the CDC data show.

Through the last full week of January, the cumulative “hospitalization rate is the highest we’ve seen,” acting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Anne Schuchat, MD, said. For the current season so far, the hospitalization rate stands at 51.4 per 100,000 population, putting it on pace to top the total of 710,000 flu-related admissions that occurred during the 2014-2015 season, she said in a weekly briefing Feb. 2.

Flu-related pediatric deaths also took a big jump for the week as another 16 were reported, which brings the total for the season to 53. Of the children who have died so far, only 20% were vaccinated, said Dan Jernigan, MD, MPH, director of the influenza division at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta. He also noted that half of the children who have been hospitalized did not had an underlying condition.

The one bit of good news for the week was that activity in the West seems to be easing up, Dr. Schuchat said. The geographic spread of ILI was reported as widespread in 48 states, which is down from 49 the previous week because Oregon dropped off the list. To go along with that, the ILI activity level in California has dropped 2 weeks in a row and now stands at level 7, the CDC data show.

Many drugs in the pipeline for IBD treatment

LAS VEGAS – .

“The challenge for all of us is to integrate the right drugs for the right patients,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, said at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Sandborn, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, began his presentation by highlighting anti-integrin therapies for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. These leukocyte membrane glycoproteins target beta1 and beta7 subunits. They interact with endothelial ligands VCAM-1, fibronectin, and MadCAM-1, and mediate leukocyte adhesion and trafficking. Approved anti-integrin therapies to date include natalizumab and vedolizumab, while investigational therapies include etrolizumab, PF-00547,659, abrilumab, and AJM 300.

In a phase 2 study of etrolizumab as induction therapy for moderate to severe UC, Séverine Vermeire, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates randomized 124 patients to one of two dose levels of subcutaneous etrolizumab (100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 8, with placebo at week 2 or a 420-mg loading dose at week 0 followed by 300 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 8), or matching placebo (The Lancet 2014 348;309-18). They found that etrolizumab was more likely to lead to clinical remission at week 10 than was placebo, especially at the 100-mg dose. Meanwhile, a more recent study of the anti-MAdCAM antibody PF-00547659 in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis found that it was better than placebo for induction of remission (The Lancet 2017;390:135-144). Investigators for the trial, known as TURANDOT, found that the greatest clinical effects were observed with the 22.5-mg and 75-mg doses. “This is now being taken forward in phase 3 trials by Shire,” Dr. Sandborn said.

The anti-interleukin 12/23 antibody (p40) ustekinumab is being investigated for efficacy in UC, while anti-interleukin 23 (p19) antibodies being studied include brazikumab (MEDI2070), risankizumab (BI 6555066), geslekumab, mirikizumab (LY3074828), and tildrakizumab (MK 3222). In 2015, Janssen launched NCT02407236, with the aim of evaluating the effectiveness and safety of continuing ustekinumab as a subcutaneous (injection) maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active UC who have demonstrated a clinical response to an induction treatment with intravenous ustekinumab. The estimated primary completion date is April 12, 2018. Meanwhile, a phase 2a trial of 119 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease who had failed treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists showed that treatment with MEDI2070 was associated with clinical improvement after 8 and 24 weeks of therapy (Gastroenterol 2017;153:77-86). The investigators also found that patients with baseline serum IL-22 concentrations above the median threshold concentration of 15.6 pg/mL treated with MEDI2070 had higher rates of clinical response and remission, compared with those with baseline concentrations below this threshold. According to Dr. Sandborn, who was not involved in the study, these results provide support for further research on the value of IL-22 serum concentrations to predict response to MEDI2070. “It’s a small study and is hypothesis generating,” he said. “This will need to be confirmed in subsequent trials.”

In a short-term study of 121 patients with active Crohn’s disease, Brian G. Feagan, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates found that risankizumab was more effective than placebo for inducing clinical remission, particularly at the 600-mg dose, compared with the 200-mg dose (Lancet 2017;389:1699-709). The researchers also observed significant differences in endoscopic remission among patients on the study drug, compared with those on placebo (17% vs. 3%; P = .0015) as well as endoscopic response (32% vs. 13%; P = .0104). The trial provides further evidence that selective blockade of interleukin 23 via inhibition of p19 might be a viable therapeutic approach in Crohn’s disease.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors under investigation for Crohn’s disease include tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, baricitinib, and TD-1473. In the OCTAVE Induction 1 trial led by Dr. Sandborn, 18.5% of the patients in the tofacitinib group achieved remission at 8 weeks, compared with 8.2% in the placebo group (P = .007); in the OCTAVE Induction 2 trial, remission occurred in 16.6% vs. 3.6% (P less than .001). In the OCTAVE Sustain trial, remission at 52 weeks occurred in 34.3% of the patients in the 5-mg tofacitinib group and 40.6% in the 10-mg tofacitinib group vs. 11.1% in the placebo group (P less than 0.001 for both comparisons with placebo; N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36). “In subgroup analyses, it looks like the 10-mg dose is more effective for maintenance in patients who previously received anti-TNF therapy,” said Dr. Sandborn, who also directs the UCSD IBD Center. “All secondary outcomes were positive. You don’t see that very often. It tells you that this is a really effective therapy. It’s currently being reviewed by the FDA.”

Meanwhile, a phase 2 trial found that a higher percentage of patients with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease who received a 200-mg dose of filgotinib over 10 weeks achieved clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo (47% vs. 23%, respectively; P = .0077; The Lancet 2017;389:266-75). Serious treatment-emergent adverse effects occurred in 9% of the 152 patients treated with filgotinib and 3 of the 67 patients treated with placebo. According to Dr. Sandborn, filgotinib is currently in phase 3 development trials for both Crohn’s Disease and UC. At the same time, results from an unpublished study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week in 2017 found that 16 weeks of treatment with the investigational agent upadacitinib led to modified clinical remission in 37% of patients on the 24-mg bid dose, compared with 30% of patients in the 6-mg bid dose. There was also a dose response for endoscopic response. “Based on these data, this drug is now in a phase 3 trial, so lots of JAK inhibitors are coming along,” he said.

Sphingosine-1–phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulators currently under investigation include fingolimod (not studied in IBD), ozanimod, and etrasimod. “These modulators cause the S1P1 receptors that are expressed on the surface of positive lymphocytes to be eluded back into the cell, which leads to a reversible reduction in circulating lymphocytes in the blood,” Dr. Sandborn explained. In a phase 2 trial, he and his associates found that UC patients who received ozanimod at a daily dose of 1 mg had a slightly higher rate of clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo, but the study was not sufficiently powered to establish clinical efficacy or assess safety (N Engl J. Med 2016;374:1754-62).

Dr. Sandborn reported having consulting relationships with Takeda, Genentech, Pfizer, Shire, Amgen, and many other pharmaceutical companies.

LAS VEGAS – .

“The challenge for all of us is to integrate the right drugs for the right patients,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, said at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Sandborn, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, began his presentation by highlighting anti-integrin therapies for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. These leukocyte membrane glycoproteins target beta1 and beta7 subunits. They interact with endothelial ligands VCAM-1, fibronectin, and MadCAM-1, and mediate leukocyte adhesion and trafficking. Approved anti-integrin therapies to date include natalizumab and vedolizumab, while investigational therapies include etrolizumab, PF-00547,659, abrilumab, and AJM 300.

In a phase 2 study of etrolizumab as induction therapy for moderate to severe UC, Séverine Vermeire, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates randomized 124 patients to one of two dose levels of subcutaneous etrolizumab (100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 8, with placebo at week 2 or a 420-mg loading dose at week 0 followed by 300 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 8), or matching placebo (The Lancet 2014 348;309-18). They found that etrolizumab was more likely to lead to clinical remission at week 10 than was placebo, especially at the 100-mg dose. Meanwhile, a more recent study of the anti-MAdCAM antibody PF-00547659 in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis found that it was better than placebo for induction of remission (The Lancet 2017;390:135-144). Investigators for the trial, known as TURANDOT, found that the greatest clinical effects were observed with the 22.5-mg and 75-mg doses. “This is now being taken forward in phase 3 trials by Shire,” Dr. Sandborn said.

The anti-interleukin 12/23 antibody (p40) ustekinumab is being investigated for efficacy in UC, while anti-interleukin 23 (p19) antibodies being studied include brazikumab (MEDI2070), risankizumab (BI 6555066), geslekumab, mirikizumab (LY3074828), and tildrakizumab (MK 3222). In 2015, Janssen launched NCT02407236, with the aim of evaluating the effectiveness and safety of continuing ustekinumab as a subcutaneous (injection) maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active UC who have demonstrated a clinical response to an induction treatment with intravenous ustekinumab. The estimated primary completion date is April 12, 2018. Meanwhile, a phase 2a trial of 119 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease who had failed treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists showed that treatment with MEDI2070 was associated with clinical improvement after 8 and 24 weeks of therapy (Gastroenterol 2017;153:77-86). The investigators also found that patients with baseline serum IL-22 concentrations above the median threshold concentration of 15.6 pg/mL treated with MEDI2070 had higher rates of clinical response and remission, compared with those with baseline concentrations below this threshold. According to Dr. Sandborn, who was not involved in the study, these results provide support for further research on the value of IL-22 serum concentrations to predict response to MEDI2070. “It’s a small study and is hypothesis generating,” he said. “This will need to be confirmed in subsequent trials.”

In a short-term study of 121 patients with active Crohn’s disease, Brian G. Feagan, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates found that risankizumab was more effective than placebo for inducing clinical remission, particularly at the 600-mg dose, compared with the 200-mg dose (Lancet 2017;389:1699-709). The researchers also observed significant differences in endoscopic remission among patients on the study drug, compared with those on placebo (17% vs. 3%; P = .0015) as well as endoscopic response (32% vs. 13%; P = .0104). The trial provides further evidence that selective blockade of interleukin 23 via inhibition of p19 might be a viable therapeutic approach in Crohn’s disease.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors under investigation for Crohn’s disease include tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, baricitinib, and TD-1473. In the OCTAVE Induction 1 trial led by Dr. Sandborn, 18.5% of the patients in the tofacitinib group achieved remission at 8 weeks, compared with 8.2% in the placebo group (P = .007); in the OCTAVE Induction 2 trial, remission occurred in 16.6% vs. 3.6% (P less than .001). In the OCTAVE Sustain trial, remission at 52 weeks occurred in 34.3% of the patients in the 5-mg tofacitinib group and 40.6% in the 10-mg tofacitinib group vs. 11.1% in the placebo group (P less than 0.001 for both comparisons with placebo; N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36). “In subgroup analyses, it looks like the 10-mg dose is more effective for maintenance in patients who previously received anti-TNF therapy,” said Dr. Sandborn, who also directs the UCSD IBD Center. “All secondary outcomes were positive. You don’t see that very often. It tells you that this is a really effective therapy. It’s currently being reviewed by the FDA.”

Meanwhile, a phase 2 trial found that a higher percentage of patients with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease who received a 200-mg dose of filgotinib over 10 weeks achieved clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo (47% vs. 23%, respectively; P = .0077; The Lancet 2017;389:266-75). Serious treatment-emergent adverse effects occurred in 9% of the 152 patients treated with filgotinib and 3 of the 67 patients treated with placebo. According to Dr. Sandborn, filgotinib is currently in phase 3 development trials for both Crohn’s Disease and UC. At the same time, results from an unpublished study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week in 2017 found that 16 weeks of treatment with the investigational agent upadacitinib led to modified clinical remission in 37% of patients on the 24-mg bid dose, compared with 30% of patients in the 6-mg bid dose. There was also a dose response for endoscopic response. “Based on these data, this drug is now in a phase 3 trial, so lots of JAK inhibitors are coming along,” he said.

Sphingosine-1–phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulators currently under investigation include fingolimod (not studied in IBD), ozanimod, and etrasimod. “These modulators cause the S1P1 receptors that are expressed on the surface of positive lymphocytes to be eluded back into the cell, which leads to a reversible reduction in circulating lymphocytes in the blood,” Dr. Sandborn explained. In a phase 2 trial, he and his associates found that UC patients who received ozanimod at a daily dose of 1 mg had a slightly higher rate of clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo, but the study was not sufficiently powered to establish clinical efficacy or assess safety (N Engl J. Med 2016;374:1754-62).

Dr. Sandborn reported having consulting relationships with Takeda, Genentech, Pfizer, Shire, Amgen, and many other pharmaceutical companies.

LAS VEGAS – .

“The challenge for all of us is to integrate the right drugs for the right patients,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, said at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Dr. Sandborn, professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego, began his presentation by highlighting anti-integrin therapies for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. These leukocyte membrane glycoproteins target beta1 and beta7 subunits. They interact with endothelial ligands VCAM-1, fibronectin, and MadCAM-1, and mediate leukocyte adhesion and trafficking. Approved anti-integrin therapies to date include natalizumab and vedolizumab, while investigational therapies include etrolizumab, PF-00547,659, abrilumab, and AJM 300.

In a phase 2 study of etrolizumab as induction therapy for moderate to severe UC, Séverine Vermeire, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates randomized 124 patients to one of two dose levels of subcutaneous etrolizumab (100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 8, with placebo at week 2 or a 420-mg loading dose at week 0 followed by 300 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 8), or matching placebo (The Lancet 2014 348;309-18). They found that etrolizumab was more likely to lead to clinical remission at week 10 than was placebo, especially at the 100-mg dose. Meanwhile, a more recent study of the anti-MAdCAM antibody PF-00547659 in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis found that it was better than placebo for induction of remission (The Lancet 2017;390:135-144). Investigators for the trial, known as TURANDOT, found that the greatest clinical effects were observed with the 22.5-mg and 75-mg doses. “This is now being taken forward in phase 3 trials by Shire,” Dr. Sandborn said.

The anti-interleukin 12/23 antibody (p40) ustekinumab is being investigated for efficacy in UC, while anti-interleukin 23 (p19) antibodies being studied include brazikumab (MEDI2070), risankizumab (BI 6555066), geslekumab, mirikizumab (LY3074828), and tildrakizumab (MK 3222). In 2015, Janssen launched NCT02407236, with the aim of evaluating the effectiveness and safety of continuing ustekinumab as a subcutaneous (injection) maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active UC who have demonstrated a clinical response to an induction treatment with intravenous ustekinumab. The estimated primary completion date is April 12, 2018. Meanwhile, a phase 2a trial of 119 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease who had failed treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists showed that treatment with MEDI2070 was associated with clinical improvement after 8 and 24 weeks of therapy (Gastroenterol 2017;153:77-86). The investigators also found that patients with baseline serum IL-22 concentrations above the median threshold concentration of 15.6 pg/mL treated with MEDI2070 had higher rates of clinical response and remission, compared with those with baseline concentrations below this threshold. According to Dr. Sandborn, who was not involved in the study, these results provide support for further research on the value of IL-22 serum concentrations to predict response to MEDI2070. “It’s a small study and is hypothesis generating,” he said. “This will need to be confirmed in subsequent trials.”

In a short-term study of 121 patients with active Crohn’s disease, Brian G. Feagan, MD, Dr. Sandborn, and associates found that risankizumab was more effective than placebo for inducing clinical remission, particularly at the 600-mg dose, compared with the 200-mg dose (Lancet 2017;389:1699-709). The researchers also observed significant differences in endoscopic remission among patients on the study drug, compared with those on placebo (17% vs. 3%; P = .0015) as well as endoscopic response (32% vs. 13%; P = .0104). The trial provides further evidence that selective blockade of interleukin 23 via inhibition of p19 might be a viable therapeutic approach in Crohn’s disease.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors under investigation for Crohn’s disease include tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, baricitinib, and TD-1473. In the OCTAVE Induction 1 trial led by Dr. Sandborn, 18.5% of the patients in the tofacitinib group achieved remission at 8 weeks, compared with 8.2% in the placebo group (P = .007); in the OCTAVE Induction 2 trial, remission occurred in 16.6% vs. 3.6% (P less than .001). In the OCTAVE Sustain trial, remission at 52 weeks occurred in 34.3% of the patients in the 5-mg tofacitinib group and 40.6% in the 10-mg tofacitinib group vs. 11.1% in the placebo group (P less than 0.001 for both comparisons with placebo; N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36). “In subgroup analyses, it looks like the 10-mg dose is more effective for maintenance in patients who previously received anti-TNF therapy,” said Dr. Sandborn, who also directs the UCSD IBD Center. “All secondary outcomes were positive. You don’t see that very often. It tells you that this is a really effective therapy. It’s currently being reviewed by the FDA.”

Meanwhile, a phase 2 trial found that a higher percentage of patients with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease who received a 200-mg dose of filgotinib over 10 weeks achieved clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo (47% vs. 23%, respectively; P = .0077; The Lancet 2017;389:266-75). Serious treatment-emergent adverse effects occurred in 9% of the 152 patients treated with filgotinib and 3 of the 67 patients treated with placebo. According to Dr. Sandborn, filgotinib is currently in phase 3 development trials for both Crohn’s Disease and UC. At the same time, results from an unpublished study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week in 2017 found that 16 weeks of treatment with the investigational agent upadacitinib led to modified clinical remission in 37% of patients on the 24-mg bid dose, compared with 30% of patients in the 6-mg bid dose. There was also a dose response for endoscopic response. “Based on these data, this drug is now in a phase 3 trial, so lots of JAK inhibitors are coming along,” he said.

Sphingosine-1–phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulators currently under investigation include fingolimod (not studied in IBD), ozanimod, and etrasimod. “These modulators cause the S1P1 receptors that are expressed on the surface of positive lymphocytes to be eluded back into the cell, which leads to a reversible reduction in circulating lymphocytes in the blood,” Dr. Sandborn explained. In a phase 2 trial, he and his associates found that UC patients who received ozanimod at a daily dose of 1 mg had a slightly higher rate of clinical remission, compared with those who received placebo, but the study was not sufficiently powered to establish clinical efficacy or assess safety (N Engl J. Med 2016;374:1754-62).

Dr. Sandborn reported having consulting relationships with Takeda, Genentech, Pfizer, Shire, Amgen, and many other pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

Preoperative exercise lowers postoperative lung resection complications

with a systematic review suggesting it reduces postoperative complications and duration of hospital stay.

The review and meta-analysis, published in the February British Journal of Sports Medicine, looked at the impact of preoperative exercise in patients undergoing surgery for a range of cancers.

Their review of 13 interventional trials, involving 806 patients and six tumor types, found the postoperative benefits of exercise were evident only in patients undergoing lung resection.

Data from five randomized controlled trials and one quasirandomized trial in lung cancer patients showed a significant 48% reduction in postoperative complications, and a significant mean reduction of 2.86 days in hospital stay among patients undergoing lung resection, compared with controls.

“Postoperative complication is a major concern for patients undergoing oncological surgery,” wrote Dr. Daniel Steffens, from the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, and his coauthors. They suggested the benefits for patients undergoing lung resection were significant enough that exercise before surgery should be considered as standard preoperative care.

“Such findings may also [have impacts] on health care costs and on patients’ quality of life, and consequently, have important implications for patients, health care professionals and policy makers.”

The exercise regimens in the lung cancer studies mostly involved aerobic exercise, such as walking, and breathing exercises to train respiratory muscles, as well as use of an exercise bicycle. The exercises were undertaken in the 1-2 weeks before surgery, with a frequency ranging from three times a week to three times a day.

The authors noted that trials involving a higher frequency of exercise showed a larger effect size, which suggested there was a dose-response relationship.

There was little evidence of benefit in other tumor types. Two studies examined the benefits of preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercises in men undergoing radical prostatectomy and found significant benefits in quality of life, assessed using the International Continence Society Male Short form. However, the authors pointed out that the quality of evidence was very low.

One study investigated the effects of preoperative mouth-opening exercise training in patients undergoing surgery for oral cancer and found enhanced postoperative quality of life in these patients, but the researchers did not report estimates.

For patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer, colorectal liver metastases, and esophageal cancer, there was no benefit of exercise either in postoperative complications or duration of hospital stay. In all these studies, the authors rated the quality of evidence as “very low.”

“Despite the evidence suggesting that exercise improves physical and mental health in patients with cancer, there are only a limited number of trials investigating the effect of preoperative exercise on patients’ quality of life,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the effect of preoperative exercise on quality of life at short-term and long-term postoperation should be explored in future trials.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Steffens D et al. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098032

with a systematic review suggesting it reduces postoperative complications and duration of hospital stay.

The review and meta-analysis, published in the February British Journal of Sports Medicine, looked at the impact of preoperative exercise in patients undergoing surgery for a range of cancers.

Their review of 13 interventional trials, involving 806 patients and six tumor types, found the postoperative benefits of exercise were evident only in patients undergoing lung resection.

Data from five randomized controlled trials and one quasirandomized trial in lung cancer patients showed a significant 48% reduction in postoperative complications, and a significant mean reduction of 2.86 days in hospital stay among patients undergoing lung resection, compared with controls.

“Postoperative complication is a major concern for patients undergoing oncological surgery,” wrote Dr. Daniel Steffens, from the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, and his coauthors. They suggested the benefits for patients undergoing lung resection were significant enough that exercise before surgery should be considered as standard preoperative care.

“Such findings may also [have impacts] on health care costs and on patients’ quality of life, and consequently, have important implications for patients, health care professionals and policy makers.”

The exercise regimens in the lung cancer studies mostly involved aerobic exercise, such as walking, and breathing exercises to train respiratory muscles, as well as use of an exercise bicycle. The exercises were undertaken in the 1-2 weeks before surgery, with a frequency ranging from three times a week to three times a day.

The authors noted that trials involving a higher frequency of exercise showed a larger effect size, which suggested there was a dose-response relationship.

There was little evidence of benefit in other tumor types. Two studies examined the benefits of preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercises in men undergoing radical prostatectomy and found significant benefits in quality of life, assessed using the International Continence Society Male Short form. However, the authors pointed out that the quality of evidence was very low.

One study investigated the effects of preoperative mouth-opening exercise training in patients undergoing surgery for oral cancer and found enhanced postoperative quality of life in these patients, but the researchers did not report estimates.

For patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer, colorectal liver metastases, and esophageal cancer, there was no benefit of exercise either in postoperative complications or duration of hospital stay. In all these studies, the authors rated the quality of evidence as “very low.”

“Despite the evidence suggesting that exercise improves physical and mental health in patients with cancer, there are only a limited number of trials investigating the effect of preoperative exercise on patients’ quality of life,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the effect of preoperative exercise on quality of life at short-term and long-term postoperation should be explored in future trials.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Steffens D et al. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098032

with a systematic review suggesting it reduces postoperative complications and duration of hospital stay.

The review and meta-analysis, published in the February British Journal of Sports Medicine, looked at the impact of preoperative exercise in patients undergoing surgery for a range of cancers.

Their review of 13 interventional trials, involving 806 patients and six tumor types, found the postoperative benefits of exercise were evident only in patients undergoing lung resection.

Data from five randomized controlled trials and one quasirandomized trial in lung cancer patients showed a significant 48% reduction in postoperative complications, and a significant mean reduction of 2.86 days in hospital stay among patients undergoing lung resection, compared with controls.

“Postoperative complication is a major concern for patients undergoing oncological surgery,” wrote Dr. Daniel Steffens, from the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, and his coauthors. They suggested the benefits for patients undergoing lung resection were significant enough that exercise before surgery should be considered as standard preoperative care.

“Such findings may also [have impacts] on health care costs and on patients’ quality of life, and consequently, have important implications for patients, health care professionals and policy makers.”

The exercise regimens in the lung cancer studies mostly involved aerobic exercise, such as walking, and breathing exercises to train respiratory muscles, as well as use of an exercise bicycle. The exercises were undertaken in the 1-2 weeks before surgery, with a frequency ranging from three times a week to three times a day.

The authors noted that trials involving a higher frequency of exercise showed a larger effect size, which suggested there was a dose-response relationship.

There was little evidence of benefit in other tumor types. Two studies examined the benefits of preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercises in men undergoing radical prostatectomy and found significant benefits in quality of life, assessed using the International Continence Society Male Short form. However, the authors pointed out that the quality of evidence was very low.

One study investigated the effects of preoperative mouth-opening exercise training in patients undergoing surgery for oral cancer and found enhanced postoperative quality of life in these patients, but the researchers did not report estimates.

For patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer, colorectal liver metastases, and esophageal cancer, there was no benefit of exercise either in postoperative complications or duration of hospital stay. In all these studies, the authors rated the quality of evidence as “very low.”

“Despite the evidence suggesting that exercise improves physical and mental health in patients with cancer, there are only a limited number of trials investigating the effect of preoperative exercise on patients’ quality of life,” the authors wrote. “Therefore, the effect of preoperative exercise on quality of life at short-term and long-term postoperation should be explored in future trials.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Steffens D et al. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Feb 1. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098032

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Exercising before oncologic surgery appears to lower the risk of postoperative complications and reduce hospital stay for lung cancer patients.

Major finding: Patients who participated in preoperative exercise before lung cancer surgery had a 48% reduction in postoperative complications, compared with controls.

Data source: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 interventional trials involving 806 patients.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Steffens D et al. Br J Sports Med. 2018, Feb 1. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098032

New and Noteworthy Information—February 2018

Device May Predict Seizure Risk

The NeuroPace RNS System may enable clinicians to identify when patients are at highest risk for seizures, thus allowing patients to plan around these events, according to a study published January 8 in Nature Communications. In 37 subjects with the implanted brain stimulation device, which detected interictal epileptiform activity (IEA) and seizures over years, researchers found that IEA oscillates with circadian and subject-specific multiday periods. Multiday periodicities, most commonly 20–30 days in duration, are robust and relatively stable for as long as 10 years in men and women. Investigators also found that seizures occur preferentially during the rising phase of multiday IEA rhythms. Combining phase information from circadian and multiday IEA rhythms could be a biomarker for determining relative seizure risk with a large effect size in most subjects.

Baud MO, Kleen JK, Mirro EA, et al. Multi-day rhythms modulate seizure risk in epilepsy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):88.

DBS May Improve Survival in Parkinson’s Disease

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is associated with a modest survival advantage when compared with medical management alone, according to a study published in the December 2017 issue of Movement Disorders. Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of Veterans Affairs and Medicare administrative data of veterans with Parkinson’s disease between 2007 and 2013. They used propensity-score matching to pair patients who received DBS with those who received medical management alone. Veterans with Parkinson’s disease who received DBS had a longer survival measured in days than veterans who did not undergo DBS (2,291 days vs 2,064 days). Mean age at death was similar for both groups (76.5 vs 75.9), and the most common cause of death was Parkinson’s disease. The study groups may have differed in ways that are not measured.

Weaver FM, Stroupe KT, Smith B, et al. Survival in patients with Parkinson’s disease after deep brain stimulation or medical management. Mov Disord. 2017;32(12):1756-1763.

Idalopirdine May Not Decrease Cognitive Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease

In patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, the use of idalopirdine, compared with placebo, does not improve cognition over 24 weeks of treatment, according to a study published January 9 in JAMA. The study examined three randomized clinical trials with 2,525 patients age 50 or older with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The 24-week studies were conducted from October 2013 to January 2017. Six months of 10 mg/day, 30 mg/day, or 60 mg/day idalopirdine treatment added to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy did not improve cognition or decrease cognitive loss. There was no requirement for evidence of Alzheimer’s disease biomarker positivity for inclusion in the trials, however, which may have allowed some patients to be included without having Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Atri A, Frölich L, Ballard C, et al. Effect of idalopirdine as adjunct to cholinesterase inhibitors on change in cognition in patients with Alzheimer disease: three randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2018;319(2):130-142.

New Biomarker May Identify Huntington’s Disease

A potential biomarker for Huntington’s disease could mean a more effective way of evaluating treatments for this neurologic disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers studied miRNA levels in CSF from 30 asymptomatic carriers of the mutation that causes Huntington’s disease. They also studied CSF from participants diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, and from healthy controls. In all, 2,081 miRNAs were detected, and six were significantly increased in asymptomatic carriers versus controls. When the researchers evaluated the miRNA levels in each of the three patient groups, they found that all six had a pattern of increasing abundance from control to low risk, and from low risk to medium risk. The miRNA levels increase years before symptoms arise.

Reed ER, Latourelle JC, Bockholt JH, et al. MicroRNAs in CSF as prodromal biomarkers for Huntington disease in the PREDICT-HD study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Higher Topiramate Dose May Increase Risk of Cleft Lip or Palate

Topiramate increases the risk of cleft lip or cleft palate in offspring in a dose-dependent manner, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers examined Medicaid data and identified approximately 1.4 million women who gave birth to live babies over 10 years. They compared women who filled a prescription for topiramate during their first trimester with women who did not fill a prescription for any antiseizure drug and women who filled a prescription for lamotrigine. The risk of oral clefts at birth was 4.1 per 1,000 in infants born to women exposed to topiramate, compared with 1.1 per 1,000 in the group unexposed to antiseizure drugs, and 1.5 per 1,000 among women exposed to lamotrigine.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, et al. Topiramate use early in pregnancy and the risk of oral clefts: A pregnancy cohort study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Genetic Factors That Contribute to Alzheimer’s Disease Identified

Researchers have identified several new genes responsible for Alzheimer’s disease, including genes leading to functional and structural changes in the brain and elevated levels of Alzheimer’s disease proteins in CSF, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers tested the association between Alzheimer’s disease-related brain MRI measures, logical memory test scores, and CSF levels of amyloid beta and tau with millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 1,189 participants in the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. Among people with normal cognitive functioning, SRRM4 was associated with total tau, and MTUS1 was associated with hippocampal volume. In participants with mild cognitive impairment, SNPs near ZNF804B were associated with logical memory test of delayed recall scores.

Chung J, Wang X, Maruyama T, et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease endophenotypes at prediagnosis stages. Alzheimers Dement. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Fish Consumption May Improve Intelligence and Sleep

Children who eat fish at least once per week sleep better and have higher IQ scores than children who consume fish less frequently or not at all, according to a study published December 21, 2017, in Scientific Reports. The study included a cohort of 541 children (54% boys) between ages 9 and 11. The children took an IQ test and completed a questionnaire about fish consumption in the previous month. Options ranged from “never” to “at least once per week.” Their parents also answered the standardized Children Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Children who reported eating fish weekly scored 4.8 points higher on the IQ exams than those who said they “seldom” or “never” consumed fish. In addition, increased fish consumption was associated with fewer sleep disturbances.

Liu J, Cui Y, Li L, et al. The mediating role of sleep in the fish consumption - cognitive functioning relationship: a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17961.

Rating Scales Predict Discharge Destination in Stroke

Outcome measure scores strongly predict discharge destination among patients with stroke and provide an objective means of early discharge planning, according to a study published in the January issue of the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. A systematic review indicated that for every one-point increase on the Functional Independence Measure, a patient was approximately 1.08 times more likely to be discharged home than to institutionalized care. Patients with stroke who performed above average were 12 times more likely to be discharged home. Patients who performed poorly were 3.4 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care than home, and skilled nursing facility admission was more likely than admission to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Patients with average performance were 1.9 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care.

Thorpe ER, Garrett KB, Smith AM, et al. Outcome measure scores predict discharge destination in patients with acute and subacute stroke: a systematic review and series of meta-analyses. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2018;42(1):2-11.

Do Green Leafy Vegetables Slow Brain Aging?

Eating about one serving per day of green, leafy vegetables may be linked to a slower rate of brain aging, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers followed 960 cognitively normal people with an average age of 81 for an average of 4.7 years. In a linear mixed model adjusted for age, sex, education, cognitive activities, physical activities, smoking, and seafood and alcohol consumption, consumption of green, leafy vegetables was associated with slower cognitive decline. Participants in the highest quintile of vegetable intake were the equivalent of 11 years younger, compared with people who never ate vegetables. Higher intake of phylloquinone, lutein, nitrate, folate, kaempferol, and alpha-tocopherol were associated with slower cognitive decline.

Morris MC, Wang Y, Barnes LL, et al. Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline: prospective study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Data Clarify the Genetic Profile of Dementia With Lewy Bodies

Research has increased understanding of the unique genetic profile of dementia with Lewy bodies. In a study published January 17 in Lancet Neurology, researchers genotyped 1,743 patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and 4,454 controls. APOE and GBA had the same associations with dementia with Lewy bodies as they do with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, respectively. SNCA, which is associated with Parkinson’s disease, also was associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but through a different part of the gene. Evidence suggested that CNTN1 is associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but the result was not statistically significant. The authors estimated that the heritable component of the disorder is approximately 36%. Common genetic variability has a role in the disease, said the authors.

Guerreiro R, Ross OA, Kun-Rodrigues C, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):64-74.

Preterm Newborns Have Altered Cerebral Perfusion

Altered regional cortical blood flow (CBF) in infants born very preterm at term-equivalent age may reflect early brain dysmaturation despite the absence of cerebral cortical injury, according to a study published online ahead of print November 30, 2017 in the Journal of Pediatrics. In this prospective, cross-sectional study, researchers used noninvasive 3T arterial spin labeling MRI to quantify regional CBF in the cerebral cortex of 202 infants, 98 of whom were born preterm. Analyses were performed controlling for sex, gestational age, and age at MRI. Infants born preterm had greater global CBF and greater absolute regional CBF in all brain regions except the insula. Relative CBF in the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and auditory cortex were decreased significantly in infants born preterm, compared with infants born at full term.

Bouyssi-Kobar M, Murnick J, Brossard-Racine M, et al. Altered cerebral perfusion in infants born preterm compared with infants born full term. J Pediatr. 2017 Nov 30 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

Device May Predict Seizure Risk

The NeuroPace RNS System may enable clinicians to identify when patients are at highest risk for seizures, thus allowing patients to plan around these events, according to a study published January 8 in Nature Communications. In 37 subjects with the implanted brain stimulation device, which detected interictal epileptiform activity (IEA) and seizures over years, researchers found that IEA oscillates with circadian and subject-specific multiday periods. Multiday periodicities, most commonly 20–30 days in duration, are robust and relatively stable for as long as 10 years in men and women. Investigators also found that seizures occur preferentially during the rising phase of multiday IEA rhythms. Combining phase information from circadian and multiday IEA rhythms could be a biomarker for determining relative seizure risk with a large effect size in most subjects.

Baud MO, Kleen JK, Mirro EA, et al. Multi-day rhythms modulate seizure risk in epilepsy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):88.

DBS May Improve Survival in Parkinson’s Disease

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is associated with a modest survival advantage when compared with medical management alone, according to a study published in the December 2017 issue of Movement Disorders. Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of Veterans Affairs and Medicare administrative data of veterans with Parkinson’s disease between 2007 and 2013. They used propensity-score matching to pair patients who received DBS with those who received medical management alone. Veterans with Parkinson’s disease who received DBS had a longer survival measured in days than veterans who did not undergo DBS (2,291 days vs 2,064 days). Mean age at death was similar for both groups (76.5 vs 75.9), and the most common cause of death was Parkinson’s disease. The study groups may have differed in ways that are not measured.

Weaver FM, Stroupe KT, Smith B, et al. Survival in patients with Parkinson’s disease after deep brain stimulation or medical management. Mov Disord. 2017;32(12):1756-1763.

Idalopirdine May Not Decrease Cognitive Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease

In patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, the use of idalopirdine, compared with placebo, does not improve cognition over 24 weeks of treatment, according to a study published January 9 in JAMA. The study examined three randomized clinical trials with 2,525 patients age 50 or older with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The 24-week studies were conducted from October 2013 to January 2017. Six months of 10 mg/day, 30 mg/day, or 60 mg/day idalopirdine treatment added to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy did not improve cognition or decrease cognitive loss. There was no requirement for evidence of Alzheimer’s disease biomarker positivity for inclusion in the trials, however, which may have allowed some patients to be included without having Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Atri A, Frölich L, Ballard C, et al. Effect of idalopirdine as adjunct to cholinesterase inhibitors on change in cognition in patients with Alzheimer disease: three randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2018;319(2):130-142.

New Biomarker May Identify Huntington’s Disease

A potential biomarker for Huntington’s disease could mean a more effective way of evaluating treatments for this neurologic disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers studied miRNA levels in CSF from 30 asymptomatic carriers of the mutation that causes Huntington’s disease. They also studied CSF from participants diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, and from healthy controls. In all, 2,081 miRNAs were detected, and six were significantly increased in asymptomatic carriers versus controls. When the researchers evaluated the miRNA levels in each of the three patient groups, they found that all six had a pattern of increasing abundance from control to low risk, and from low risk to medium risk. The miRNA levels increase years before symptoms arise.

Reed ER, Latourelle JC, Bockholt JH, et al. MicroRNAs in CSF as prodromal biomarkers for Huntington disease in the PREDICT-HD study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Higher Topiramate Dose May Increase Risk of Cleft Lip or Palate

Topiramate increases the risk of cleft lip or cleft palate in offspring in a dose-dependent manner, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers examined Medicaid data and identified approximately 1.4 million women who gave birth to live babies over 10 years. They compared women who filled a prescription for topiramate during their first trimester with women who did not fill a prescription for any antiseizure drug and women who filled a prescription for lamotrigine. The risk of oral clefts at birth was 4.1 per 1,000 in infants born to women exposed to topiramate, compared with 1.1 per 1,000 in the group unexposed to antiseizure drugs, and 1.5 per 1,000 among women exposed to lamotrigine.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, et al. Topiramate use early in pregnancy and the risk of oral clefts: A pregnancy cohort study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Genetic Factors That Contribute to Alzheimer’s Disease Identified

Researchers have identified several new genes responsible for Alzheimer’s disease, including genes leading to functional and structural changes in the brain and elevated levels of Alzheimer’s disease proteins in CSF, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers tested the association between Alzheimer’s disease-related brain MRI measures, logical memory test scores, and CSF levels of amyloid beta and tau with millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 1,189 participants in the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. Among people with normal cognitive functioning, SRRM4 was associated with total tau, and MTUS1 was associated with hippocampal volume. In participants with mild cognitive impairment, SNPs near ZNF804B were associated with logical memory test of delayed recall scores.

Chung J, Wang X, Maruyama T, et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease endophenotypes at prediagnosis stages. Alzheimers Dement. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Fish Consumption May Improve Intelligence and Sleep

Children who eat fish at least once per week sleep better and have higher IQ scores than children who consume fish less frequently or not at all, according to a study published December 21, 2017, in Scientific Reports. The study included a cohort of 541 children (54% boys) between ages 9 and 11. The children took an IQ test and completed a questionnaire about fish consumption in the previous month. Options ranged from “never” to “at least once per week.” Their parents also answered the standardized Children Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Children who reported eating fish weekly scored 4.8 points higher on the IQ exams than those who said they “seldom” or “never” consumed fish. In addition, increased fish consumption was associated with fewer sleep disturbances.

Liu J, Cui Y, Li L, et al. The mediating role of sleep in the fish consumption - cognitive functioning relationship: a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17961.

Rating Scales Predict Discharge Destination in Stroke

Outcome measure scores strongly predict discharge destination among patients with stroke and provide an objective means of early discharge planning, according to a study published in the January issue of the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. A systematic review indicated that for every one-point increase on the Functional Independence Measure, a patient was approximately 1.08 times more likely to be discharged home than to institutionalized care. Patients with stroke who performed above average were 12 times more likely to be discharged home. Patients who performed poorly were 3.4 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care than home, and skilled nursing facility admission was more likely than admission to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Patients with average performance were 1.9 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care.

Thorpe ER, Garrett KB, Smith AM, et al. Outcome measure scores predict discharge destination in patients with acute and subacute stroke: a systematic review and series of meta-analyses. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2018;42(1):2-11.

Do Green Leafy Vegetables Slow Brain Aging?

Eating about one serving per day of green, leafy vegetables may be linked to a slower rate of brain aging, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers followed 960 cognitively normal people with an average age of 81 for an average of 4.7 years. In a linear mixed model adjusted for age, sex, education, cognitive activities, physical activities, smoking, and seafood and alcohol consumption, consumption of green, leafy vegetables was associated with slower cognitive decline. Participants in the highest quintile of vegetable intake were the equivalent of 11 years younger, compared with people who never ate vegetables. Higher intake of phylloquinone, lutein, nitrate, folate, kaempferol, and alpha-tocopherol were associated with slower cognitive decline.

Morris MC, Wang Y, Barnes LL, et al. Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline: prospective study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Data Clarify the Genetic Profile of Dementia With Lewy Bodies

Research has increased understanding of the unique genetic profile of dementia with Lewy bodies. In a study published January 17 in Lancet Neurology, researchers genotyped 1,743 patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and 4,454 controls. APOE and GBA had the same associations with dementia with Lewy bodies as they do with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, respectively. SNCA, which is associated with Parkinson’s disease, also was associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but through a different part of the gene. Evidence suggested that CNTN1 is associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but the result was not statistically significant. The authors estimated that the heritable component of the disorder is approximately 36%. Common genetic variability has a role in the disease, said the authors.

Guerreiro R, Ross OA, Kun-Rodrigues C, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):64-74.

Preterm Newborns Have Altered Cerebral Perfusion

Altered regional cortical blood flow (CBF) in infants born very preterm at term-equivalent age may reflect early brain dysmaturation despite the absence of cerebral cortical injury, according to a study published online ahead of print November 30, 2017 in the Journal of Pediatrics. In this prospective, cross-sectional study, researchers used noninvasive 3T arterial spin labeling MRI to quantify regional CBF in the cerebral cortex of 202 infants, 98 of whom were born preterm. Analyses were performed controlling for sex, gestational age, and age at MRI. Infants born preterm had greater global CBF and greater absolute regional CBF in all brain regions except the insula. Relative CBF in the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and auditory cortex were decreased significantly in infants born preterm, compared with infants born at full term.

Bouyssi-Kobar M, Murnick J, Brossard-Racine M, et al. Altered cerebral perfusion in infants born preterm compared with infants born full term. J Pediatr. 2017 Nov 30 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

Device May Predict Seizure Risk

The NeuroPace RNS System may enable clinicians to identify when patients are at highest risk for seizures, thus allowing patients to plan around these events, according to a study published January 8 in Nature Communications. In 37 subjects with the implanted brain stimulation device, which detected interictal epileptiform activity (IEA) and seizures over years, researchers found that IEA oscillates with circadian and subject-specific multiday periods. Multiday periodicities, most commonly 20–30 days in duration, are robust and relatively stable for as long as 10 years in men and women. Investigators also found that seizures occur preferentially during the rising phase of multiday IEA rhythms. Combining phase information from circadian and multiday IEA rhythms could be a biomarker for determining relative seizure risk with a large effect size in most subjects.

Baud MO, Kleen JK, Mirro EA, et al. Multi-day rhythms modulate seizure risk in epilepsy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):88.

DBS May Improve Survival in Parkinson’s Disease

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is associated with a modest survival advantage when compared with medical management alone, according to a study published in the December 2017 issue of Movement Disorders. Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of Veterans Affairs and Medicare administrative data of veterans with Parkinson’s disease between 2007 and 2013. They used propensity-score matching to pair patients who received DBS with those who received medical management alone. Veterans with Parkinson’s disease who received DBS had a longer survival measured in days than veterans who did not undergo DBS (2,291 days vs 2,064 days). Mean age at death was similar for both groups (76.5 vs 75.9), and the most common cause of death was Parkinson’s disease. The study groups may have differed in ways that are not measured.

Weaver FM, Stroupe KT, Smith B, et al. Survival in patients with Parkinson’s disease after deep brain stimulation or medical management. Mov Disord. 2017;32(12):1756-1763.

Idalopirdine May Not Decrease Cognitive Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease

In patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, the use of idalopirdine, compared with placebo, does not improve cognition over 24 weeks of treatment, according to a study published January 9 in JAMA. The study examined three randomized clinical trials with 2,525 patients age 50 or older with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The 24-week studies were conducted from October 2013 to January 2017. Six months of 10 mg/day, 30 mg/day, or 60 mg/day idalopirdine treatment added to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy did not improve cognition or decrease cognitive loss. There was no requirement for evidence of Alzheimer’s disease biomarker positivity for inclusion in the trials, however, which may have allowed some patients to be included without having Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Atri A, Frölich L, Ballard C, et al. Effect of idalopirdine as adjunct to cholinesterase inhibitors on change in cognition in patients with Alzheimer disease: three randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2018;319(2):130-142.

New Biomarker May Identify Huntington’s Disease

A potential biomarker for Huntington’s disease could mean a more effective way of evaluating treatments for this neurologic disease, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers studied miRNA levels in CSF from 30 asymptomatic carriers of the mutation that causes Huntington’s disease. They also studied CSF from participants diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, and from healthy controls. In all, 2,081 miRNAs were detected, and six were significantly increased in asymptomatic carriers versus controls. When the researchers evaluated the miRNA levels in each of the three patient groups, they found that all six had a pattern of increasing abundance from control to low risk, and from low risk to medium risk. The miRNA levels increase years before symptoms arise.

Reed ER, Latourelle JC, Bockholt JH, et al. MicroRNAs in CSF as prodromal biomarkers for Huntington disease in the PREDICT-HD study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Higher Topiramate Dose May Increase Risk of Cleft Lip or Palate

Topiramate increases the risk of cleft lip or cleft palate in offspring in a dose-dependent manner, according to a study published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers examined Medicaid data and identified approximately 1.4 million women who gave birth to live babies over 10 years. They compared women who filled a prescription for topiramate during their first trimester with women who did not fill a prescription for any antiseizure drug and women who filled a prescription for lamotrigine. The risk of oral clefts at birth was 4.1 per 1,000 in infants born to women exposed to topiramate, compared with 1.1 per 1,000 in the group unexposed to antiseizure drugs, and 1.5 per 1,000 among women exposed to lamotrigine.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, et al. Topiramate use early in pregnancy and the risk of oral clefts: A pregnancy cohort study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Genetic Factors That Contribute to Alzheimer’s Disease Identified

Researchers have identified several new genes responsible for Alzheimer’s disease, including genes leading to functional and structural changes in the brain and elevated levels of Alzheimer’s disease proteins in CSF, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Researchers tested the association between Alzheimer’s disease-related brain MRI measures, logical memory test scores, and CSF levels of amyloid beta and tau with millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 1,189 participants in the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. Among people with normal cognitive functioning, SRRM4 was associated with total tau, and MTUS1 was associated with hippocampal volume. In participants with mild cognitive impairment, SNPs near ZNF804B were associated with logical memory test of delayed recall scores.

Chung J, Wang X, Maruyama T, et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease endophenotypes at prediagnosis stages. Alzheimers Dement. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Fish Consumption May Improve Intelligence and Sleep

Children who eat fish at least once per week sleep better and have higher IQ scores than children who consume fish less frequently or not at all, according to a study published December 21, 2017, in Scientific Reports. The study included a cohort of 541 children (54% boys) between ages 9 and 11. The children took an IQ test and completed a questionnaire about fish consumption in the previous month. Options ranged from “never” to “at least once per week.” Their parents also answered the standardized Children Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Children who reported eating fish weekly scored 4.8 points higher on the IQ exams than those who said they “seldom” or “never” consumed fish. In addition, increased fish consumption was associated with fewer sleep disturbances.

Liu J, Cui Y, Li L, et al. The mediating role of sleep in the fish consumption - cognitive functioning relationship: a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17961.

Rating Scales Predict Discharge Destination in Stroke

Outcome measure scores strongly predict discharge destination among patients with stroke and provide an objective means of early discharge planning, according to a study published in the January issue of the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. A systematic review indicated that for every one-point increase on the Functional Independence Measure, a patient was approximately 1.08 times more likely to be discharged home than to institutionalized care. Patients with stroke who performed above average were 12 times more likely to be discharged home. Patients who performed poorly were 3.4 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care than home, and skilled nursing facility admission was more likely than admission to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Patients with average performance were 1.9 times more likely to be discharged to institutionalized care.

Thorpe ER, Garrett KB, Smith AM, et al. Outcome measure scores predict discharge destination in patients with acute and subacute stroke: a systematic review and series of meta-analyses. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2018;42(1):2-11.

Do Green Leafy Vegetables Slow Brain Aging?

Eating about one serving per day of green, leafy vegetables may be linked to a slower rate of brain aging, according to a study published online ahead of print December 20, 2017, in Neurology. Researchers followed 960 cognitively normal people with an average age of 81 for an average of 4.7 years. In a linear mixed model adjusted for age, sex, education, cognitive activities, physical activities, smoking, and seafood and alcohol consumption, consumption of green, leafy vegetables was associated with slower cognitive decline. Participants in the highest quintile of vegetable intake were the equivalent of 11 years younger, compared with people who never ate vegetables. Higher intake of phylloquinone, lutein, nitrate, folate, kaempferol, and alpha-tocopherol were associated with slower cognitive decline.

Morris MC, Wang Y, Barnes LL, et al. Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline: prospective study. Neurology. 2017 Dec 20 [Epub ahead of print].

Data Clarify the Genetic Profile of Dementia With Lewy Bodies

Research has increased understanding of the unique genetic profile of dementia with Lewy bodies. In a study published January 17 in Lancet Neurology, researchers genotyped 1,743 patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and 4,454 controls. APOE and GBA had the same associations with dementia with Lewy bodies as they do with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, respectively. SNCA, which is associated with Parkinson’s disease, also was associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but through a different part of the gene. Evidence suggested that CNTN1 is associated with dementia with Lewy bodies, but the result was not statistically significant. The authors estimated that the heritable component of the disorder is approximately 36%. Common genetic variability has a role in the disease, said the authors.

Guerreiro R, Ross OA, Kun-Rodrigues C, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):64-74.

Preterm Newborns Have Altered Cerebral Perfusion

Altered regional cortical blood flow (CBF) in infants born very preterm at term-equivalent age may reflect early brain dysmaturation despite the absence of cerebral cortical injury, according to a study published online ahead of print November 30, 2017 in the Journal of Pediatrics. In this prospective, cross-sectional study, researchers used noninvasive 3T arterial spin labeling MRI to quantify regional CBF in the cerebral cortex of 202 infants, 98 of whom were born preterm. Analyses were performed controlling for sex, gestational age, and age at MRI. Infants born preterm had greater global CBF and greater absolute regional CBF in all brain regions except the insula. Relative CBF in the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and auditory cortex were decreased significantly in infants born preterm, compared with infants born at full term.

Bouyssi-Kobar M, Murnick J, Brossard-Racine M, et al. Altered cerebral perfusion in infants born preterm compared with infants born full term. J Pediatr. 2017 Nov 30 [Epub ahead of print].

—Kimberly Williams

NIMH launches interactive statistics section on its website