User login

A Quick Test Identifies Risk Factors for Sleep Apnea in Pregnant Women

Snoring on 3 or more nights per week, older maternal age, and obesity—these are risk factors for sleep apnea in pregnancy, according to a National Institutes of Health-funded study. Checking for those factors is an easy, inexpensive way to rapidly identify women who may benefit from further testing, says Uma Reddy, MD, study coauthor.

In the study, 3,264 women in early pregnancy (6 -15 weeks) and 2,512 in mid-pregnancy (22- 29 weeks) responded to questionnaires about their sleep habits, snoring, and daytime sleepiness. Participants also used an at-home monitoring device to test for sleep apnea.

Nearly 4% of the women in early pregnancy and 8.3% of those in mid-pregnancy had sleep apnea. In an earlier study of first-time pregnancies, the researchers found that sleep apnea increases the risk of hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes. A clinical study of the link between sleep-disordered breathing and adverse pregnancy outcomes is underway, expected to be completed by 2019.

Currently there are no medical guidelines or treatment recommendations for sleep apnea during pregnancy.

Snoring on 3 or more nights per week, older maternal age, and obesity—these are risk factors for sleep apnea in pregnancy, according to a National Institutes of Health-funded study. Checking for those factors is an easy, inexpensive way to rapidly identify women who may benefit from further testing, says Uma Reddy, MD, study coauthor.

In the study, 3,264 women in early pregnancy (6 -15 weeks) and 2,512 in mid-pregnancy (22- 29 weeks) responded to questionnaires about their sleep habits, snoring, and daytime sleepiness. Participants also used an at-home monitoring device to test for sleep apnea.

Nearly 4% of the women in early pregnancy and 8.3% of those in mid-pregnancy had sleep apnea. In an earlier study of first-time pregnancies, the researchers found that sleep apnea increases the risk of hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes. A clinical study of the link between sleep-disordered breathing and adverse pregnancy outcomes is underway, expected to be completed by 2019.

Currently there are no medical guidelines or treatment recommendations for sleep apnea during pregnancy.

Snoring on 3 or more nights per week, older maternal age, and obesity—these are risk factors for sleep apnea in pregnancy, according to a National Institutes of Health-funded study. Checking for those factors is an easy, inexpensive way to rapidly identify women who may benefit from further testing, says Uma Reddy, MD, study coauthor.

In the study, 3,264 women in early pregnancy (6 -15 weeks) and 2,512 in mid-pregnancy (22- 29 weeks) responded to questionnaires about their sleep habits, snoring, and daytime sleepiness. Participants also used an at-home monitoring device to test for sleep apnea.

Nearly 4% of the women in early pregnancy and 8.3% of those in mid-pregnancy had sleep apnea. In an earlier study of first-time pregnancies, the researchers found that sleep apnea increases the risk of hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes. A clinical study of the link between sleep-disordered breathing and adverse pregnancy outcomes is underway, expected to be completed by 2019.

Currently there are no medical guidelines or treatment recommendations for sleep apnea during pregnancy.

Agent can reveal HSC engraftment faster

An imaging agent can safely show engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) just days after transplant, according to research published in The Lancet Haematology.

The agent is 18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), a radio-labeled analogue of thymidine.

Past studies have shown that 18F-FLT is incorporated into HSCs.

With the current study, researchers wanted to determine if 18F-FLT could allow them to safely visualize transplanted HSCs.

Kirsten M. Williams, MD, of Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, and her colleagues tested 18F-FLT in 23 patients undergoing HSC transplant to treat high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients first underwent total body irradiation to destroy their own HSCs and then received donor HSCs.

The patients underwent PET/CT scans 1 day before they were infused with HSCs as well as post-transplant at 5 or 9 days, 28 days, and 1 year.

Results

All patients engrafted, a finding that was reflected in blood tests conducted 2 to 4 weeks after transplant. However, imaging results revealed more details.

“Through the images we took, these patients could see the new cells growing in their bodies,” Dr Williams said. “They loved that.”

The researchers and the patients saw the HSCs take a complex journey as they engrafted.

First, HSCs migrated to the patients’ livers and spleens. Next, the cells went to the thoracic spine, the axial spine, the sternum, and the arms and legs.

By 1 year, most of the HSCs were concentrated in the bones that make up the trunk of the body, including the hip, where most biopsies to assess marrow function take place.

This pathway is the same one HSCs take in the fetus when they first form.

The researchers also found the radiation in 18F-FLT did not adversely affect engraftment.

And imaging could reveal successful engraftment at 5 days post-transplant, “which was up to 20 days before engraftment became clinically evident,” according to the researchers.

Dr Williams and her colleagues believe use of 18F-FLT could potentially help patients avoid bone marrow biopsies or, at the very least, help target those biopsies.

And the agent might be helpful for taking stock of HSCs in conditions such as aplastic anemia.

“What happens with HSCs always has been a mystery,” Dr Williams said. “Now, we can start to open that black box.”

An imaging agent can safely show engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) just days after transplant, according to research published in The Lancet Haematology.

The agent is 18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), a radio-labeled analogue of thymidine.

Past studies have shown that 18F-FLT is incorporated into HSCs.

With the current study, researchers wanted to determine if 18F-FLT could allow them to safely visualize transplanted HSCs.

Kirsten M. Williams, MD, of Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, and her colleagues tested 18F-FLT in 23 patients undergoing HSC transplant to treat high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients first underwent total body irradiation to destroy their own HSCs and then received donor HSCs.

The patients underwent PET/CT scans 1 day before they were infused with HSCs as well as post-transplant at 5 or 9 days, 28 days, and 1 year.

Results

All patients engrafted, a finding that was reflected in blood tests conducted 2 to 4 weeks after transplant. However, imaging results revealed more details.

“Through the images we took, these patients could see the new cells growing in their bodies,” Dr Williams said. “They loved that.”

The researchers and the patients saw the HSCs take a complex journey as they engrafted.

First, HSCs migrated to the patients’ livers and spleens. Next, the cells went to the thoracic spine, the axial spine, the sternum, and the arms and legs.

By 1 year, most of the HSCs were concentrated in the bones that make up the trunk of the body, including the hip, where most biopsies to assess marrow function take place.

This pathway is the same one HSCs take in the fetus when they first form.

The researchers also found the radiation in 18F-FLT did not adversely affect engraftment.

And imaging could reveal successful engraftment at 5 days post-transplant, “which was up to 20 days before engraftment became clinically evident,” according to the researchers.

Dr Williams and her colleagues believe use of 18F-FLT could potentially help patients avoid bone marrow biopsies or, at the very least, help target those biopsies.

And the agent might be helpful for taking stock of HSCs in conditions such as aplastic anemia.

“What happens with HSCs always has been a mystery,” Dr Williams said. “Now, we can start to open that black box.”

An imaging agent can safely show engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) just days after transplant, according to research published in The Lancet Haematology.

The agent is 18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), a radio-labeled analogue of thymidine.

Past studies have shown that 18F-FLT is incorporated into HSCs.

With the current study, researchers wanted to determine if 18F-FLT could allow them to safely visualize transplanted HSCs.

Kirsten M. Williams, MD, of Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, and her colleagues tested 18F-FLT in 23 patients undergoing HSC transplant to treat high-risk hematologic malignancies.

The patients first underwent total body irradiation to destroy their own HSCs and then received donor HSCs.

The patients underwent PET/CT scans 1 day before they were infused with HSCs as well as post-transplant at 5 or 9 days, 28 days, and 1 year.

Results

All patients engrafted, a finding that was reflected in blood tests conducted 2 to 4 weeks after transplant. However, imaging results revealed more details.

“Through the images we took, these patients could see the new cells growing in their bodies,” Dr Williams said. “They loved that.”

The researchers and the patients saw the HSCs take a complex journey as they engrafted.

First, HSCs migrated to the patients’ livers and spleens. Next, the cells went to the thoracic spine, the axial spine, the sternum, and the arms and legs.

By 1 year, most of the HSCs were concentrated in the bones that make up the trunk of the body, including the hip, where most biopsies to assess marrow function take place.

This pathway is the same one HSCs take in the fetus when they first form.

The researchers also found the radiation in 18F-FLT did not adversely affect engraftment.

And imaging could reveal successful engraftment at 5 days post-transplant, “which was up to 20 days before engraftment became clinically evident,” according to the researchers.

Dr Williams and her colleagues believe use of 18F-FLT could potentially help patients avoid bone marrow biopsies or, at the very least, help target those biopsies.

And the agent might be helpful for taking stock of HSCs in conditions such as aplastic anemia.

“What happens with HSCs always has been a mystery,” Dr Williams said. “Now, we can start to open that black box.”

Taking the Bite Out of Nutrition

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

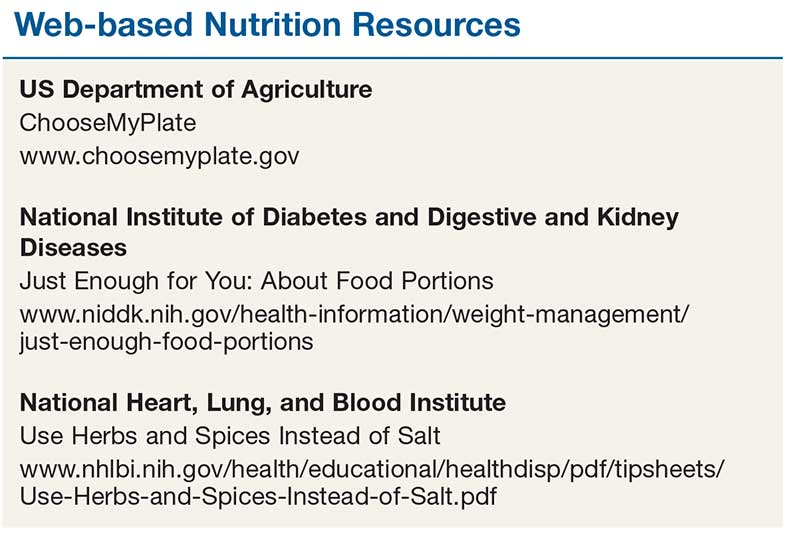

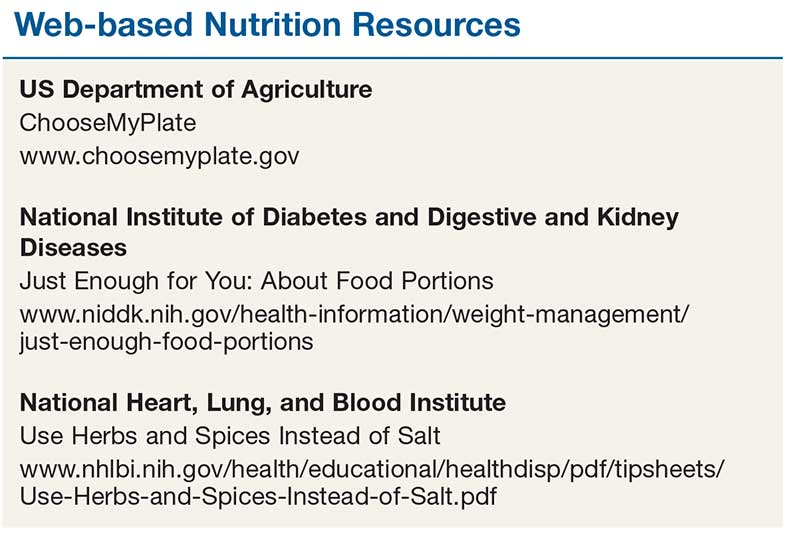

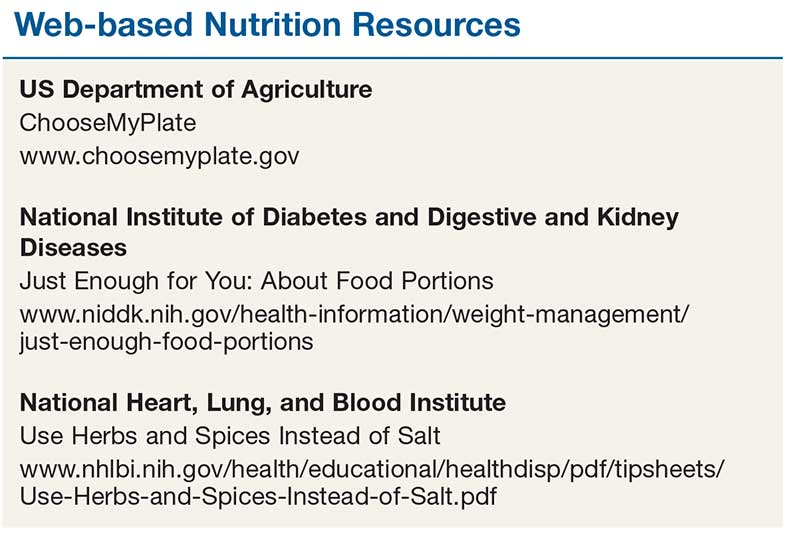

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

As March arrives, we rejoice in the promise of spring sunlight and start planning ahead for summer and its associated clothing, which tends to be a bit more … revealing, shall we say. If we’re really motivated, we might dust off our (quickly forgotten) New Year’s weight-loss resolutions, adjusting our carb:veggie ratio to get beach-ready. Furthermore, March historically signified the start of farming season—making it a natural fit for National Nutrition Month.

In 1973, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) initiated a week-long campaign to educate the public about hea

This guidance is needed more now than ever before. About 75% of Americans follow a diet that is low in fruits, vegetables, dairy, and oils (compared to the recommended values)—and most exceed the recommended allotment for added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats.2 It’s no surprise, then, that two-thirds of US adults are either overweight or obese.2

It is imperative that we, as health care providers, provide our patients and their families with practical, evidence-based information about healthy food choices. But are we sufficiently educated to provide that guidance?

I admit, my confidence in my nutritional knowledge falls short of the mark. I vaguely recall nutrition being discussed in one of my basic nursing courses; diets designed for specific disease entities were introduced as I progressed in my education. But a specific nutrition course is not a requirement in the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice—even though nutrition is directly linked to wellness and health promotion is an essential component of nursing practice.3 (This inconsistency in nutrition education holds true for our PA colleagues, as well.)

How, then, do we educate ourselves so that we can impart the necessary guidance to our patients? The plethora of articles—some more scholarly than others—on what we should and should not eat can be very confusing.

Generally, though, the soundest advice encourages a healthy lifestyle, with emphasis on consistent, enjoyable eating practices and regular physical activity. Of particular note: The word “diet” is not included in most guides. Rather, we are advised to make small changes to the way we think about eating.

Substituting fruit for added sugar, whole grains for refined grains, and oils for solid fats are just a few simple ways to transition to a healthier eating regimen.2 Another adaptation is to plan out meals and snacks prior to food shopping; this not only prevents us from making poor choices and purchasing items based on impulse or hunger, but also decreases food waste. These comparatively small adjustments can make a real difference over time.

To help achieve the goal of a healthy lifestyle, AND offers the following suggestions:

- Include a variety of healthful foods from all food groups on a regular basis.

- Consider which food items you have on hand before buying more at the store.

- Buy only an amount that can be eaten within a few days (or stored in the freezer) and plan ways to use leftovers later in the week.

- Be mindful of portion sizes.

- Find activities you enjoy to keep you physically active throughout the week.4

We also have a resource at our fingertips that we often overlook: registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs). These professionals are educated specifically to provide counseling on food choices and can help clear the murky waters surrounding nutrition. An RDN can partner with a consumer to develop a safe, effective, sustainable eating plan that takes into consideration health status, lifestyle, and personal taste preferences.

In addition to RDN colleagues, there are trustworthy, easy-to-navigate websites that provide resources on nutrition and healthy eating. They also have tools we can provide to our patients and their families (see box). For example, ChooseMyPlate (www.choosemyplate.gov) is an interactive site based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that provides information on how much of each food group should be eaten each day. It also includes resources for planning well-balanced, healthy meals and a series of fact sheets with tips that can be useful for patients. The National Institutes of Health also offers practical guidance on differentiating a portion from a serving, controlling portion size (both at home and when eating out), and finding alternatives to salt when you want or need to season food.

Reviewing even just one or two of these resources can improve your knowledge about healthy eating habits. Since a balanced and tasty meal plan is a recipe for success, let’s make better nutrition our mantra. We can help our patients, and perhaps learn something ourselves!

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month®. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/national-nutrition-month. Accessed February 13, 2018.

2. US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. 8th ed. 2015. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed February 13, 2018.

3. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. 2008. www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/BaccEssentials08.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

4. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. National Nutrition Month® celebration toolkit. www.eatright.org/resource/food/resources/national-nutrition-month/toolkit. Accessed February 13, 2018.

Gout: What You Need to Know

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

Women, Apply for Leadership Training Grant

Through the Leadership Development and Diversity Committee, the SVS continues its strong commitment to leadership development in women. The Women's Leadership Training Grant seeks to identify female surgeons who want to sharpen their leadership skills. A $5,000 award will defray costs for travel, hotel accommodations and registration expenses to attend relevant courses and/or other leadership training opportunities and activities. Application deadline is March 14.

Through the Leadership Development and Diversity Committee, the SVS continues its strong commitment to leadership development in women. The Women's Leadership Training Grant seeks to identify female surgeons who want to sharpen their leadership skills. A $5,000 award will defray costs for travel, hotel accommodations and registration expenses to attend relevant courses and/or other leadership training opportunities and activities. Application deadline is March 14.

Through the Leadership Development and Diversity Committee, the SVS continues its strong commitment to leadership development in women. The Women's Leadership Training Grant seeks to identify female surgeons who want to sharpen their leadership skills. A $5,000 award will defray costs for travel, hotel accommodations and registration expenses to attend relevant courses and/or other leadership training opportunities and activities. Application deadline is March 14.

Apply for Disaster Relief Funds by March 16

The SVS Foundation will accept applications through March 16 for funds from its Disaster Relief Fund. The fund can be used for recovery efforts in areas that have experienced catastrophes.

Monies support programs, initiated by SVS members, that provide short-term emergency assistance and longer-term aid for vascular surgery practices and vascular patients in disaster-devastated communities.

The SVS Foundation will accept applications through March 16 for funds from its Disaster Relief Fund. The fund can be used for recovery efforts in areas that have experienced catastrophes.

Monies support programs, initiated by SVS members, that provide short-term emergency assistance and longer-term aid for vascular surgery practices and vascular patients in disaster-devastated communities.

The SVS Foundation will accept applications through March 16 for funds from its Disaster Relief Fund. The fund can be used for recovery efforts in areas that have experienced catastrophes.

Monies support programs, initiated by SVS members, that provide short-term emergency assistance and longer-term aid for vascular surgery practices and vascular patients in disaster-devastated communities.

Get Pocket Versions of Practice Guidelines

SVS has partnered with Guidelines Central to create a Pocket Guide version of the new AAA guidelines. Also available are pocket guides on Management of Diabetic Foot, Peripheral Arterial Disease and Venous Leg Ulcers.

SVS members can access the digital versions for free; printed guidelines vary in price. The guidelines also are available as a bundled set.

Slide sets of the guidelines, useful as educational tools, also are available online.

SVS has partnered with Guidelines Central to create a Pocket Guide version of the new AAA guidelines. Also available are pocket guides on Management of Diabetic Foot, Peripheral Arterial Disease and Venous Leg Ulcers.

SVS members can access the digital versions for free; printed guidelines vary in price. The guidelines also are available as a bundled set.

Slide sets of the guidelines, useful as educational tools, also are available online.

SVS has partnered with Guidelines Central to create a Pocket Guide version of the new AAA guidelines. Also available are pocket guides on Management of Diabetic Foot, Peripheral Arterial Disease and Venous Leg Ulcers.

SVS members can access the digital versions for free; printed guidelines vary in price. The guidelines also are available as a bundled set.

Slide sets of the guidelines, useful as educational tools, also are available online.

VAM Registration Opens This Week

It's nearly here! The 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting takes a big step forward this week with the opening of housing and registration. Prepare to sign up for VAM, June 20 to 23 in Boston.

Following a full day of postgraduate courses, VESS abstracts, workshops and international programming, abstract-based scientific sessions will open June 21 and continue to June 23. The Exhibit Hall will be open June 21 to 22.

Catch the highlights of this year's annual meeting here.

It's nearly here! The 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting takes a big step forward this week with the opening of housing and registration. Prepare to sign up for VAM, June 20 to 23 in Boston.

Following a full day of postgraduate courses, VESS abstracts, workshops and international programming, abstract-based scientific sessions will open June 21 and continue to June 23. The Exhibit Hall will be open June 21 to 22.

Catch the highlights of this year's annual meeting here.

It's nearly here! The 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting takes a big step forward this week with the opening of housing and registration. Prepare to sign up for VAM, June 20 to 23 in Boston.

Following a full day of postgraduate courses, VESS abstracts, workshops and international programming, abstract-based scientific sessions will open June 21 and continue to June 23. The Exhibit Hall will be open June 21 to 22.

Catch the highlights of this year's annual meeting here.

Drug approved to treat newly diagnosed MM in China

The China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) has approved lenalidomide (Revlimid®) to treat patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant.

Lenalidomide was first approved by the CFDA in 2013 for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who had received at least one prior therapy.

“In China, where the incidence of multiple myeloma is on the rise due to an aging population and improved diagnosis, we are hopeful that newly diagnosed patients will have a meaningful long-term benefit from this approval,” said John V. Oyler, founder, chief executive officer, and chairman of BeiGene, the company marketing lenalidomide as Revlimid in China under an exclusive license from Celgene Corporation.

Trial results

The CFDA’s decision to expand the approval of lenalidomide is based on results from the phase 3 FIRST trial. Updated results from this study were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in November 2016.

The trial included 1623 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive:

- Lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), known as the “continuous Rd group”

- 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), known as the “Rd18 group”

- Melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, progression-free survival rates were 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The median overall survival was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, overall survival rates were 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

The China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) has approved lenalidomide (Revlimid®) to treat patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant.

Lenalidomide was first approved by the CFDA in 2013 for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who had received at least one prior therapy.

“In China, where the incidence of multiple myeloma is on the rise due to an aging population and improved diagnosis, we are hopeful that newly diagnosed patients will have a meaningful long-term benefit from this approval,” said John V. Oyler, founder, chief executive officer, and chairman of BeiGene, the company marketing lenalidomide as Revlimid in China under an exclusive license from Celgene Corporation.

Trial results

The CFDA’s decision to expand the approval of lenalidomide is based on results from the phase 3 FIRST trial. Updated results from this study were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in November 2016.

The trial included 1623 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive:

- Lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), known as the “continuous Rd group”

- 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), known as the “Rd18 group”

- Melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, progression-free survival rates were 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The median overall survival was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, overall survival rates were 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

The China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) has approved lenalidomide (Revlimid®) to treat patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for transplant.

Lenalidomide was first approved by the CFDA in 2013 for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat adults with MM who had received at least one prior therapy.

“In China, where the incidence of multiple myeloma is on the rise due to an aging population and improved diagnosis, we are hopeful that newly diagnosed patients will have a meaningful long-term benefit from this approval,” said John V. Oyler, founder, chief executive officer, and chairman of BeiGene, the company marketing lenalidomide as Revlimid in China under an exclusive license from Celgene Corporation.

Trial results

The CFDA’s decision to expand the approval of lenalidomide is based on results from the phase 3 FIRST trial. Updated results from this study were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in November 2016.

The trial included 1623 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive:

- Lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), known as the “continuous Rd group”

- 18 cycles of Rd (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), known as the “Rd18 group”

- Melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

In the intent-to-treat population, the overall response rate was 81% for the continuous Rd group, 79% for the Rd18 group, and 67% in the MPT group. The complete response rates were 21%, 20%, and 12%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was 26.0 months in the continuous Rd group, 21.0 months in the Rd18 group, and 21.9 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, progression-free survival rates were 33%, 14%, and 13%, respectively.

The median overall survival was 58.9 months in the continuous Rd group, 56.7 months in the Rd18 group, and 48.5 months in the MPT group. At 4 years, overall survival rates were 60%, 57%, and 51%, respectively.

The most frequent grade 3/4 hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anemia. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was higher in the MPT group than the continuous Rd or Rd18 groups.

Infections were the most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events. The rate of grade 3/4 infections was higher in the Rd groups than the MPT group.

Does boosting inhaled glucocorticoids avoid asthma exacerbations?

in preventing the exacerbation from occurring, according to the results of two trials in adults and children.

Presented at the joint congress of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the World Asthma Organization and simultaneously published in the March 3 online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, one study explored the effect of quadrupling the inhaled glucocorticoid dose in adults and adolescents with asthma, while the other looked at quintupling the dose in children.

At 1 year, there was a significantly lower incidence of severe asthma exacerbations in the group who used the higher dose of inhaled glucocorticoids (45% vs. 52%; hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .001) after adjusting for age, sex, and peak flow measures at randomization.

Researchers also saw a lower percentage of participants using systemic glucocorticoids in the quadruple-dose group compared with the normal-dose group (33% vs. 40%), and the quadruple-dose group also showed a 14% lower incidence of unscheduled health care consultations.

At the end of the 12-month follow-up, the estimated mean total dose of inhaled glucocorticoids was 385 mg in the quadruple-dose group and 328 mg in the normal-dose group.

The most common serious adverse event was hospitalization for asthma, which occurred three times in the quadruple-dose group and 18 times in the normal-dose group. However the incidence of oral candidiasis and dysphonia – both potentially treatment related – was significantly higher in the quadruple-dose group (36 events vs. 9 events).

Overall, the number needed to treat with the quadruple dose to prevent one severe asthma exacerbation was 15.

“Given the potential benefit with respect to preventing exacerbations and in view of the toxic effects of inhaled glucocorticoids and the biases that may have been introduced by the absence of blinding, individual practitioners, patients, and guideline committees will need to consider whether the magnitude of the reduction achieved is clinically meaningful,” wrote Tricia McKeever, PhD, from the department of epidemiology and public health at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom) and her coauthors.

The second study, which was double blinded, investigated whether quintupling the dose of inhaled glucocorticoids might avoid exacerbations in children. They randomized 254 children who had mild-moderate persistent asthma and had had at least one exacerbation treated with systemic glucocorticoids in the previous year to manage “yellow zone” early warning signs with either normal dose or five times their usual dose of inhaled glucocorticoids.

The rate of severe asthma exacerbations did not differ significantly between the quintuple-dose and normal-dose groups at the 1-year follow-up (0.48 vs. 0.37; P = 0.3), nor did the time to the first severe exacerbation or the rate of emergency department or urgent care visits.

The four hospitalizations for asthma all occurred in the high-dose group. However, there was a lower growth rate seen in children in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group (5.43 cm/yr vs. 5.65 cm/yr; P = .06). There were no significant differences between the two groups in other adverse events.

However, Daniel J. Jackson, MD, and his coauthors noted that there were fewer yellow zone episodes and fewer exacerbations in both groups than they had anticipated.

“It is important to recognize that our findings are specific to school-age children with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma regularly treated with daily low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids (with good adherence),” wrote Dr. Jackson from the department of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and his coauthors.

The first study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Six authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding and support from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

The second study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Fifteen authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, as well as other private industry, outside the submitted work. Several also declared grants from organizations including the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: McKeeve T et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714257; Jackson DJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM0a1710988.

These two trials address the important question of whether substantial escalation of regularly used inhaled glucocorticoids prevents exacerbations if started at the first sign of deterioration, as this so-called yellow zone has long been thought the perfect time to initiate more aggressive care. However glucocorticoids have serious side effects, and there is some preclinical evidence that they may enhance viral replication

One trial shows that escalating dose in this yellow zone does not prevent exacerbations in children with the early signs of asthma instability. The second trial is more complex and more controversial, as the open-label design may have biased the outcome, and the degree of benefit is debatable.

Together, these studies suggest that high doses of inhaled glucocorticoids either do not prevent exacerbations or only do so in a small subgroup of patients with as-yet-undefined baseline and exacerbation characteristics.

Philip G. Bardin, PhD, is from the Monash Lung and Sleep Unit at the Monash University Medical Centre in Melbourne, Australia. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1800152). Dr. Bardin reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work.

These two trials address the important question of whether substantial escalation of regularly used inhaled glucocorticoids prevents exacerbations if started at the first sign of deterioration, as this so-called yellow zone has long been thought the perfect time to initiate more aggressive care. However glucocorticoids have serious side effects, and there is some preclinical evidence that they may enhance viral replication

One trial shows that escalating dose in this yellow zone does not prevent exacerbations in children with the early signs of asthma instability. The second trial is more complex and more controversial, as the open-label design may have biased the outcome, and the degree of benefit is debatable.

Together, these studies suggest that high doses of inhaled glucocorticoids either do not prevent exacerbations or only do so in a small subgroup of patients with as-yet-undefined baseline and exacerbation characteristics.

Philip G. Bardin, PhD, is from the Monash Lung and Sleep Unit at the Monash University Medical Centre in Melbourne, Australia. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1800152). Dr. Bardin reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work.

These two trials address the important question of whether substantial escalation of regularly used inhaled glucocorticoids prevents exacerbations if started at the first sign of deterioration, as this so-called yellow zone has long been thought the perfect time to initiate more aggressive care. However glucocorticoids have serious side effects, and there is some preclinical evidence that they may enhance viral replication

One trial shows that escalating dose in this yellow zone does not prevent exacerbations in children with the early signs of asthma instability. The second trial is more complex and more controversial, as the open-label design may have biased the outcome, and the degree of benefit is debatable.

Together, these studies suggest that high doses of inhaled glucocorticoids either do not prevent exacerbations or only do so in a small subgroup of patients with as-yet-undefined baseline and exacerbation characteristics.

Philip G. Bardin, PhD, is from the Monash Lung and Sleep Unit at the Monash University Medical Centre in Melbourne, Australia. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1800152). Dr. Bardin reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work.

in preventing the exacerbation from occurring, according to the results of two trials in adults and children.

Presented at the joint congress of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the World Asthma Organization and simultaneously published in the March 3 online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, one study explored the effect of quadrupling the inhaled glucocorticoid dose in adults and adolescents with asthma, while the other looked at quintupling the dose in children.

At 1 year, there was a significantly lower incidence of severe asthma exacerbations in the group who used the higher dose of inhaled glucocorticoids (45% vs. 52%; hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .001) after adjusting for age, sex, and peak flow measures at randomization.

Researchers also saw a lower percentage of participants using systemic glucocorticoids in the quadruple-dose group compared with the normal-dose group (33% vs. 40%), and the quadruple-dose group also showed a 14% lower incidence of unscheduled health care consultations.

At the end of the 12-month follow-up, the estimated mean total dose of inhaled glucocorticoids was 385 mg in the quadruple-dose group and 328 mg in the normal-dose group.

The most common serious adverse event was hospitalization for asthma, which occurred three times in the quadruple-dose group and 18 times in the normal-dose group. However the incidence of oral candidiasis and dysphonia – both potentially treatment related – was significantly higher in the quadruple-dose group (36 events vs. 9 events).

Overall, the number needed to treat with the quadruple dose to prevent one severe asthma exacerbation was 15.

“Given the potential benefit with respect to preventing exacerbations and in view of the toxic effects of inhaled glucocorticoids and the biases that may have been introduced by the absence of blinding, individual practitioners, patients, and guideline committees will need to consider whether the magnitude of the reduction achieved is clinically meaningful,” wrote Tricia McKeever, PhD, from the department of epidemiology and public health at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom) and her coauthors.

The second study, which was double blinded, investigated whether quintupling the dose of inhaled glucocorticoids might avoid exacerbations in children. They randomized 254 children who had mild-moderate persistent asthma and had had at least one exacerbation treated with systemic glucocorticoids in the previous year to manage “yellow zone” early warning signs with either normal dose or five times their usual dose of inhaled glucocorticoids.

The rate of severe asthma exacerbations did not differ significantly between the quintuple-dose and normal-dose groups at the 1-year follow-up (0.48 vs. 0.37; P = 0.3), nor did the time to the first severe exacerbation or the rate of emergency department or urgent care visits.

The four hospitalizations for asthma all occurred in the high-dose group. However, there was a lower growth rate seen in children in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group (5.43 cm/yr vs. 5.65 cm/yr; P = .06). There were no significant differences between the two groups in other adverse events.

However, Daniel J. Jackson, MD, and his coauthors noted that there were fewer yellow zone episodes and fewer exacerbations in both groups than they had anticipated.

“It is important to recognize that our findings are specific to school-age children with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma regularly treated with daily low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids (with good adherence),” wrote Dr. Jackson from the department of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and his coauthors.

The first study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Six authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding and support from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

The second study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Fifteen authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, as well as other private industry, outside the submitted work. Several also declared grants from organizations including the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: McKeeve T et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714257; Jackson DJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM0a1710988.

in preventing the exacerbation from occurring, according to the results of two trials in adults and children.

Presented at the joint congress of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the World Asthma Organization and simultaneously published in the March 3 online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, one study explored the effect of quadrupling the inhaled glucocorticoid dose in adults and adolescents with asthma, while the other looked at quintupling the dose in children.

At 1 year, there was a significantly lower incidence of severe asthma exacerbations in the group who used the higher dose of inhaled glucocorticoids (45% vs. 52%; hazard ratio, 0.80; P = .001) after adjusting for age, sex, and peak flow measures at randomization.

Researchers also saw a lower percentage of participants using systemic glucocorticoids in the quadruple-dose group compared with the normal-dose group (33% vs. 40%), and the quadruple-dose group also showed a 14% lower incidence of unscheduled health care consultations.

At the end of the 12-month follow-up, the estimated mean total dose of inhaled glucocorticoids was 385 mg in the quadruple-dose group and 328 mg in the normal-dose group.

The most common serious adverse event was hospitalization for asthma, which occurred three times in the quadruple-dose group and 18 times in the normal-dose group. However the incidence of oral candidiasis and dysphonia – both potentially treatment related – was significantly higher in the quadruple-dose group (36 events vs. 9 events).

Overall, the number needed to treat with the quadruple dose to prevent one severe asthma exacerbation was 15.

“Given the potential benefit with respect to preventing exacerbations and in view of the toxic effects of inhaled glucocorticoids and the biases that may have been introduced by the absence of blinding, individual practitioners, patients, and guideline committees will need to consider whether the magnitude of the reduction achieved is clinically meaningful,” wrote Tricia McKeever, PhD, from the department of epidemiology and public health at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom) and her coauthors.

The second study, which was double blinded, investigated whether quintupling the dose of inhaled glucocorticoids might avoid exacerbations in children. They randomized 254 children who had mild-moderate persistent asthma and had had at least one exacerbation treated with systemic glucocorticoids in the previous year to manage “yellow zone” early warning signs with either normal dose or five times their usual dose of inhaled glucocorticoids.

The rate of severe asthma exacerbations did not differ significantly between the quintuple-dose and normal-dose groups at the 1-year follow-up (0.48 vs. 0.37; P = 0.3), nor did the time to the first severe exacerbation or the rate of emergency department or urgent care visits.

The four hospitalizations for asthma all occurred in the high-dose group. However, there was a lower growth rate seen in children in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group (5.43 cm/yr vs. 5.65 cm/yr; P = .06). There were no significant differences between the two groups in other adverse events.

However, Daniel J. Jackson, MD, and his coauthors noted that there were fewer yellow zone episodes and fewer exacerbations in both groups than they had anticipated.

“It is important to recognize that our findings are specific to school-age children with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma regularly treated with daily low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids (with good adherence),” wrote Dr. Jackson from the department of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and his coauthors.

The first study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Six authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding and support from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work.

The second study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Fifteen authors declared grants, personal fees and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, as well as other private industry, outside the submitted work. Several also declared grants from organizations including the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: McKeeve T et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714257; Jackson DJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM0a1710988.

FROM AAAAI/WAO JOINT CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Escalating the dose of inhaled glucocorticoids at the first early warnings of an asthma exacerbation may not significantly reduce the likelihood of the exacerbation occurring.

Major finding: Fifteen individuals would need to quadruple their dose of inhaled glucocorticoids to avoid one asthma exacerbation.

Data source: Two randomized, controlled trials in 1,992 adolescents and adults and 254 children with asthma.

Disclosures: The first study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Six authors declared grants, personal fees, and other funding and support from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. The second study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Fifteen authors declared grants, personal fees, and other funding from the pharmaceutical industry, as well as other private industry, outside the submitted work. Several also declared grants from organizations including the National Institutes of Health. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Sources: McKeeve T et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714257; Jackson DJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM0a1710988.