User login

Emerging Therapies In Psoriasis: A Systematic Review

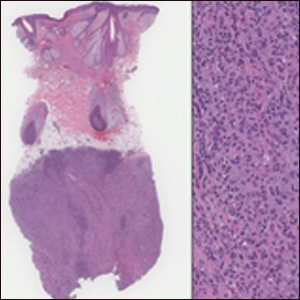

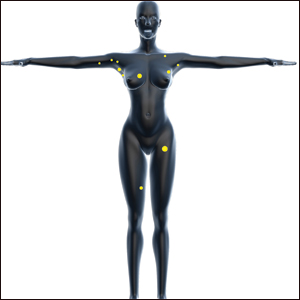

Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disease estimated to affect 2.8% of the US population.1 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to involve a complex process triggered by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that induce tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α secretion by keratinocytes, which in turn activates dendritic cells. Activated dendritic cells produce IL-23, leading to helper T cell (TH17) differentiation.2,3 TH17 cells secrete IL-17A, which has been shown to promote psoriatic skin changes.4 Therefore, TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17A have been recognized as key targets for psoriasis therapy.

The newest biologic agents targeting IL-17–mediated pathways include ixekizumab, brodalumab, and bimekizumab. Secukinumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved IL-17 inhibitor, has been available since 2015 and therefore is not included in this review. IL-23 inhibitors that are FDA approved or being evaluated in clinical trials include guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab. In addition, certolizumab pegol, a TNF-α inhibitor, is being studied for use in psoriasis.

METHODS

We reviewed the published results of phase 3 clinical trials for ixekizumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab, and certolizumab pegol. We performed an English-language literature search (January 1, 2012 to October 15, 2017) of articles indexed for PubMed/MEDLINE using the following combinations of keywords: IL-23 and psoriasis; IL-17 and psoriasis; tumor necrosis factor and psoriasis; [drug name] and psoriasis. If data from phase 3 clinical trials were not yet available, data from phase 2 clinical trials were incorporated in our analysis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources.

RESULTS

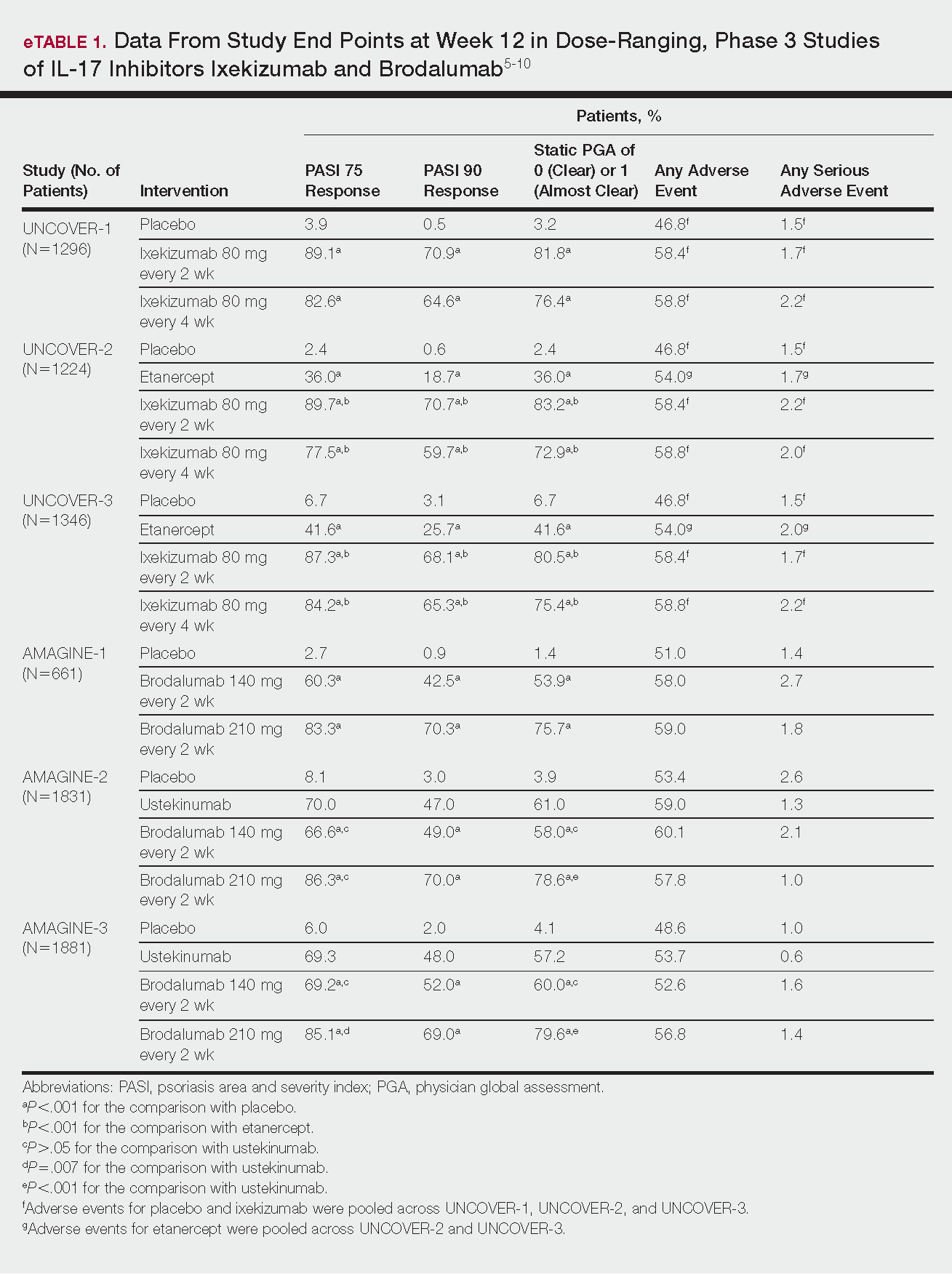

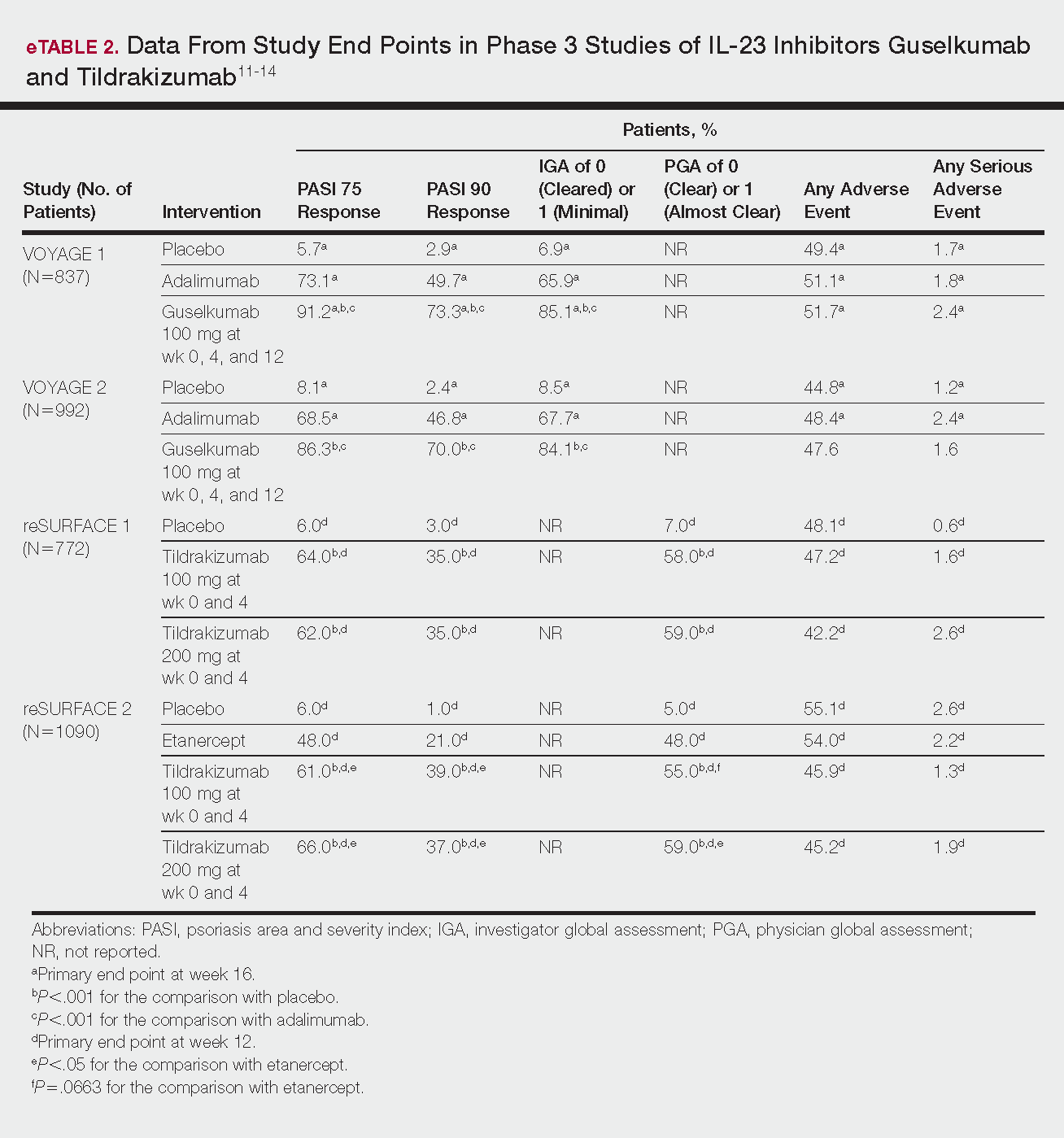

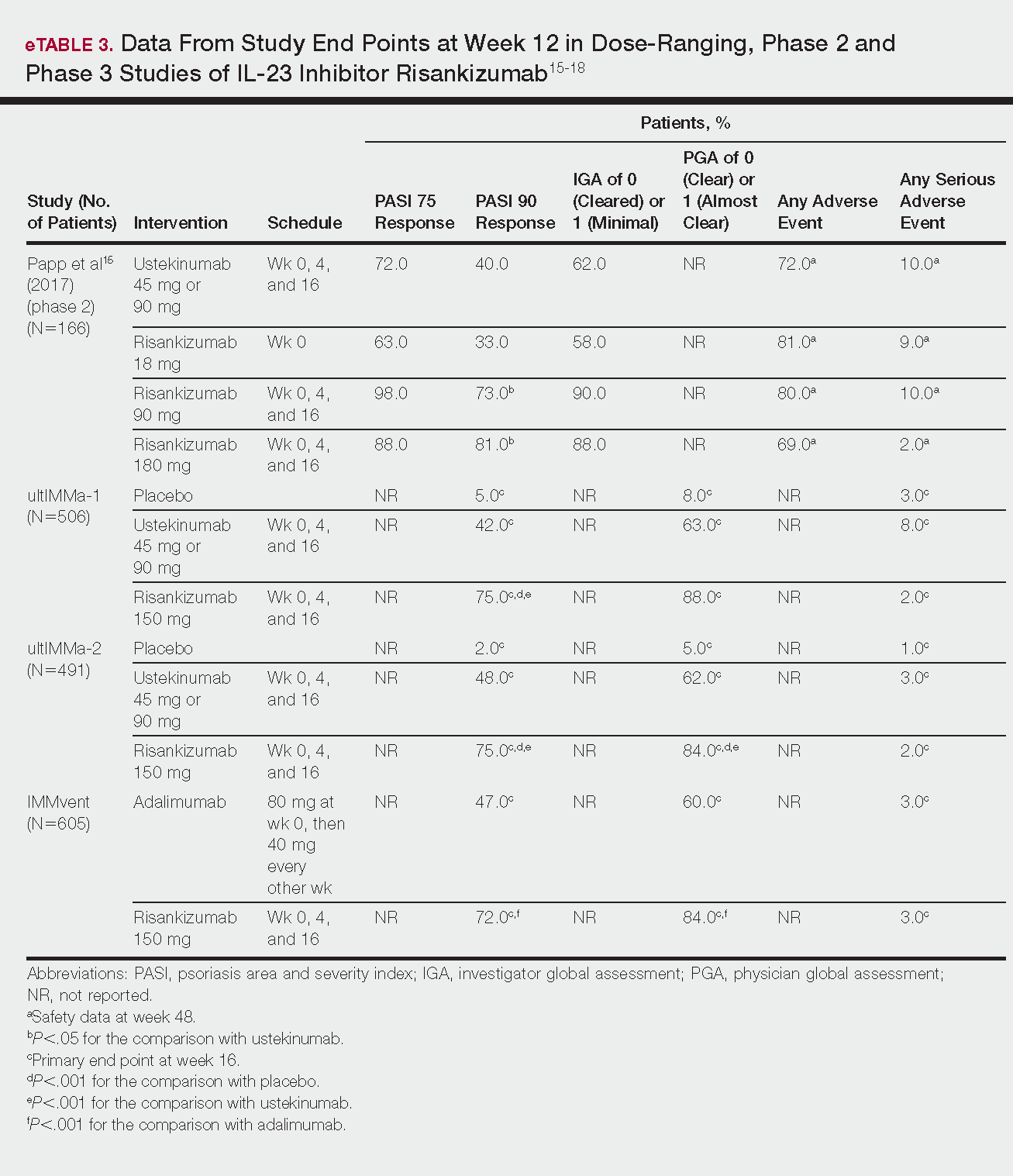

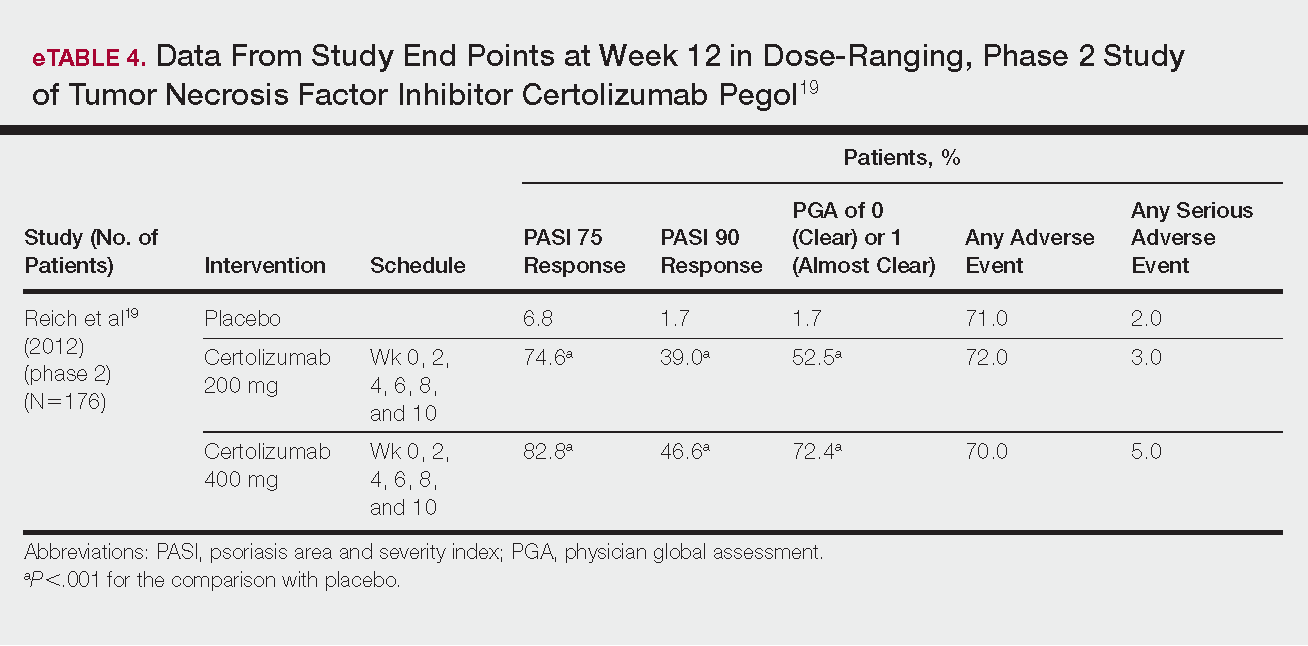

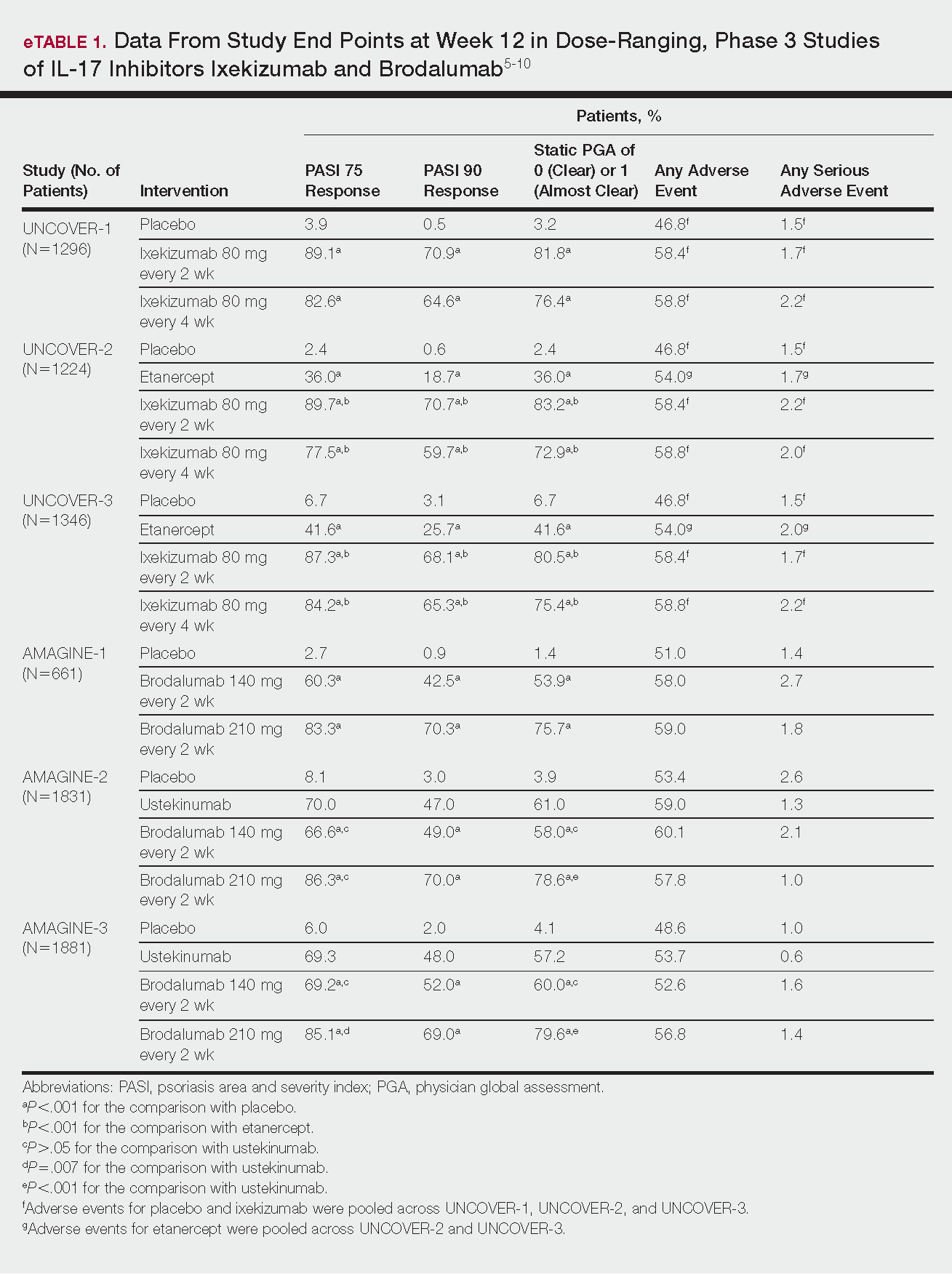

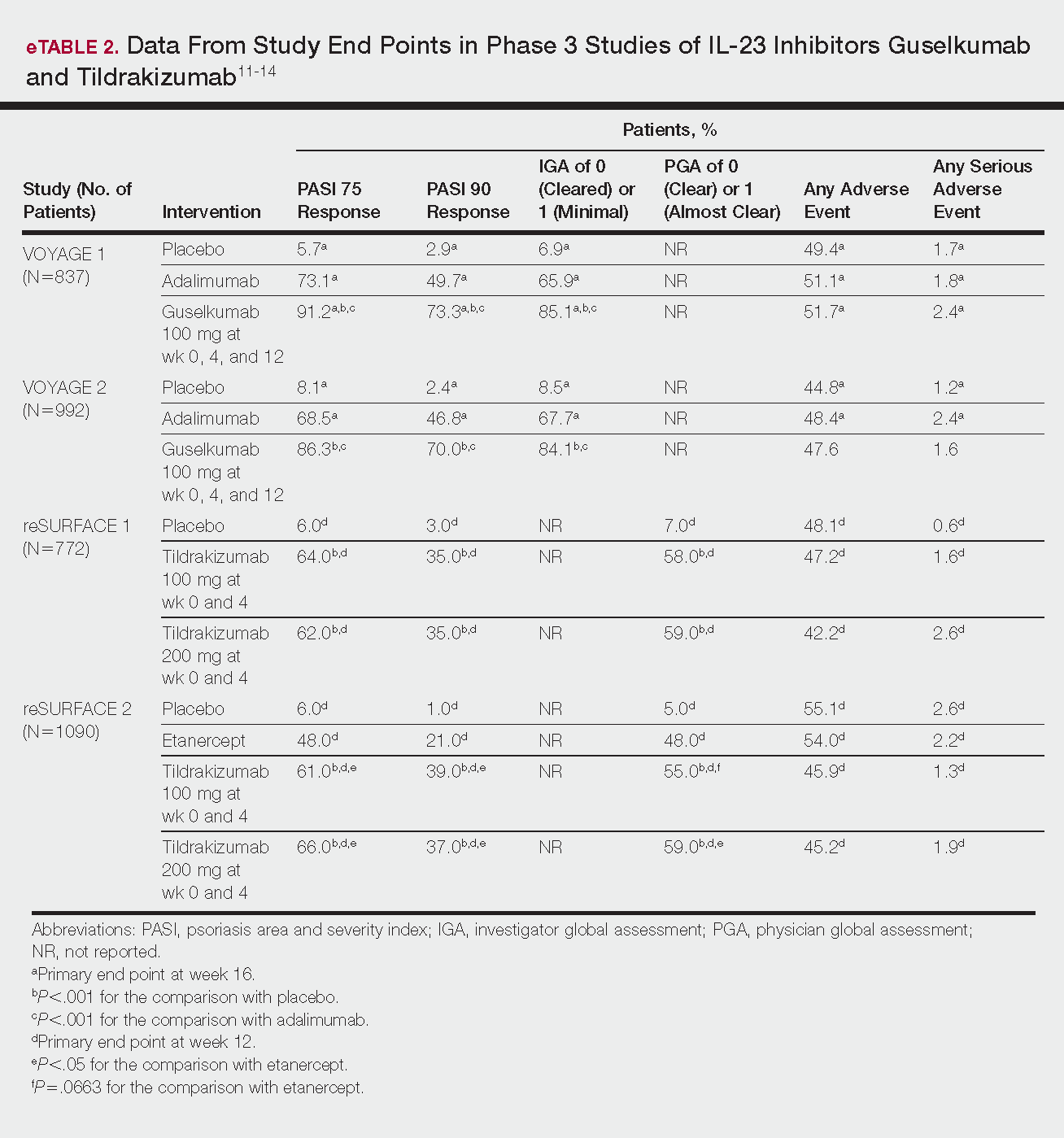

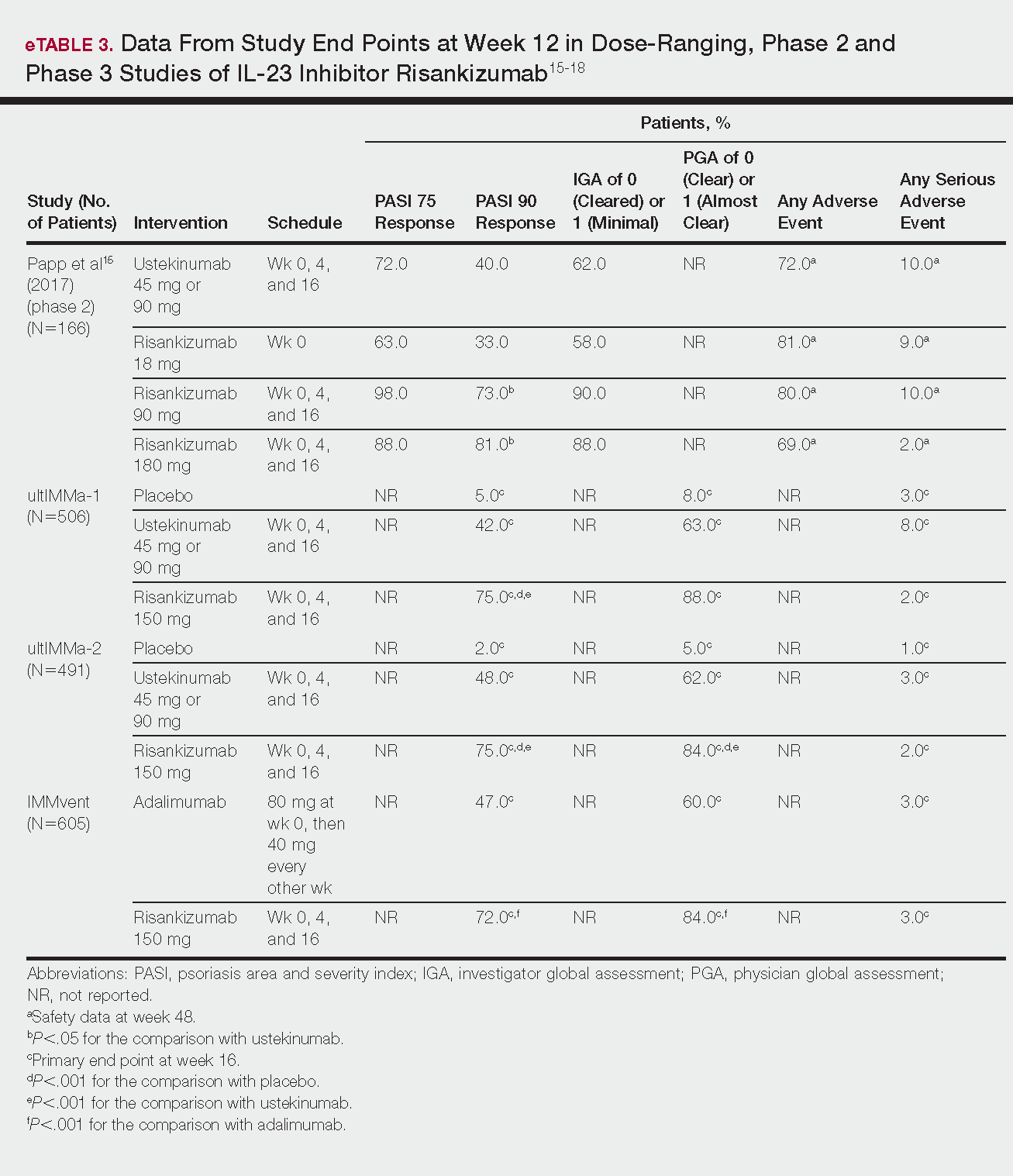

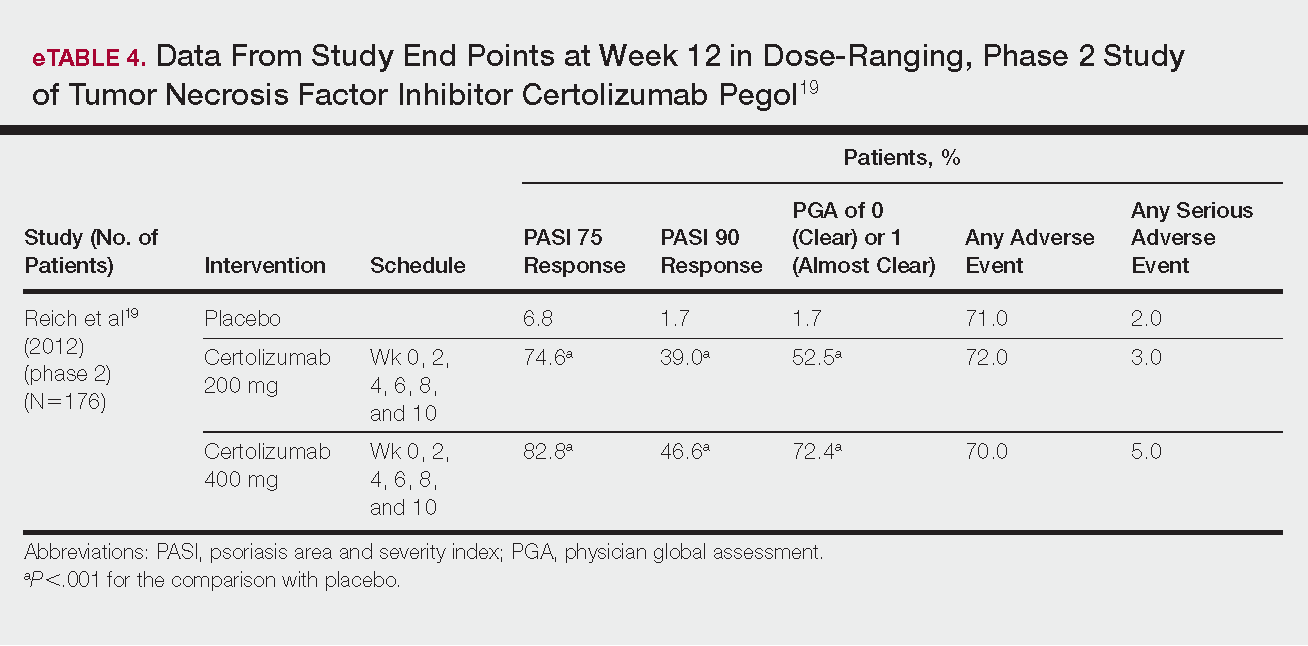

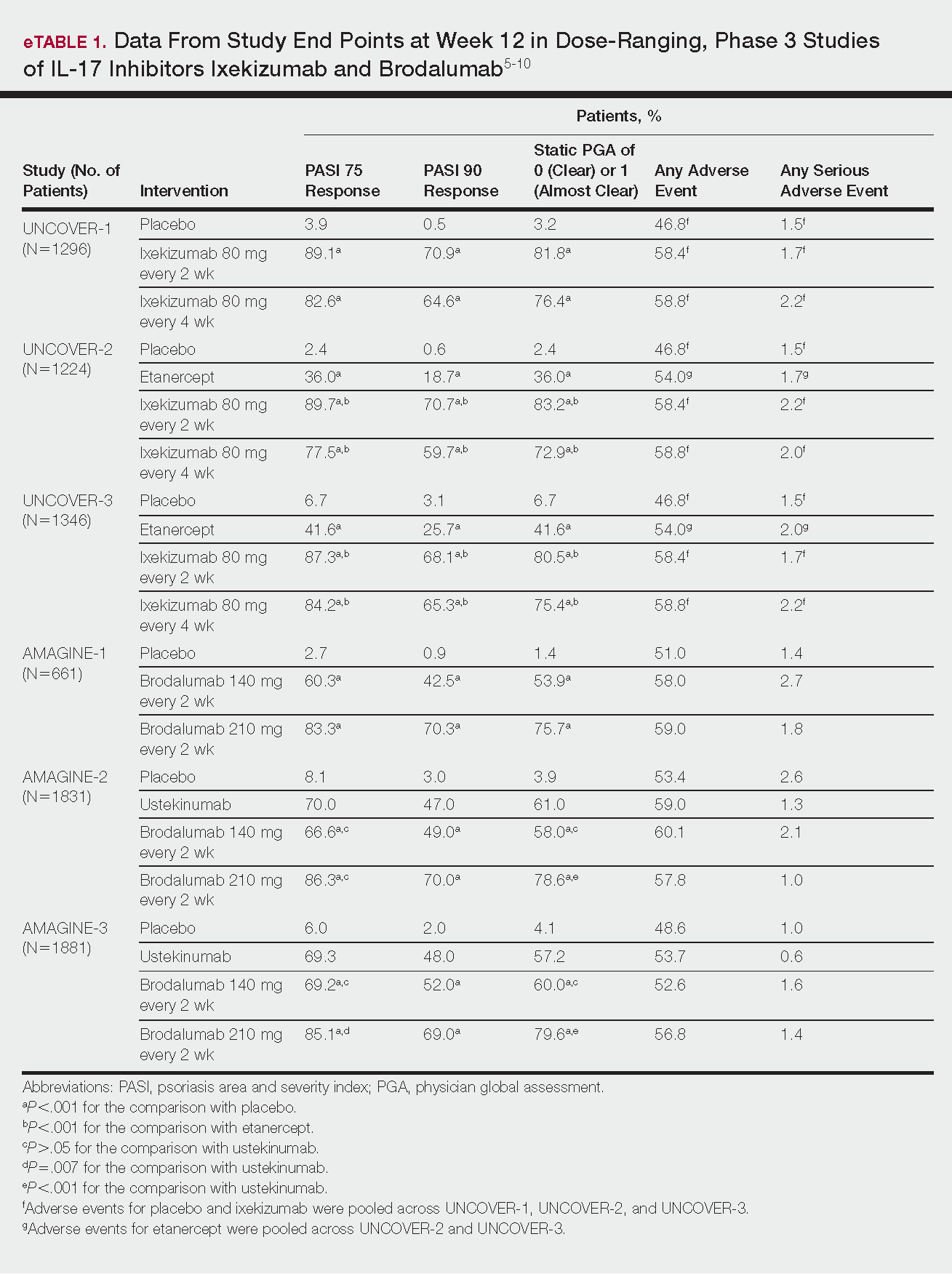

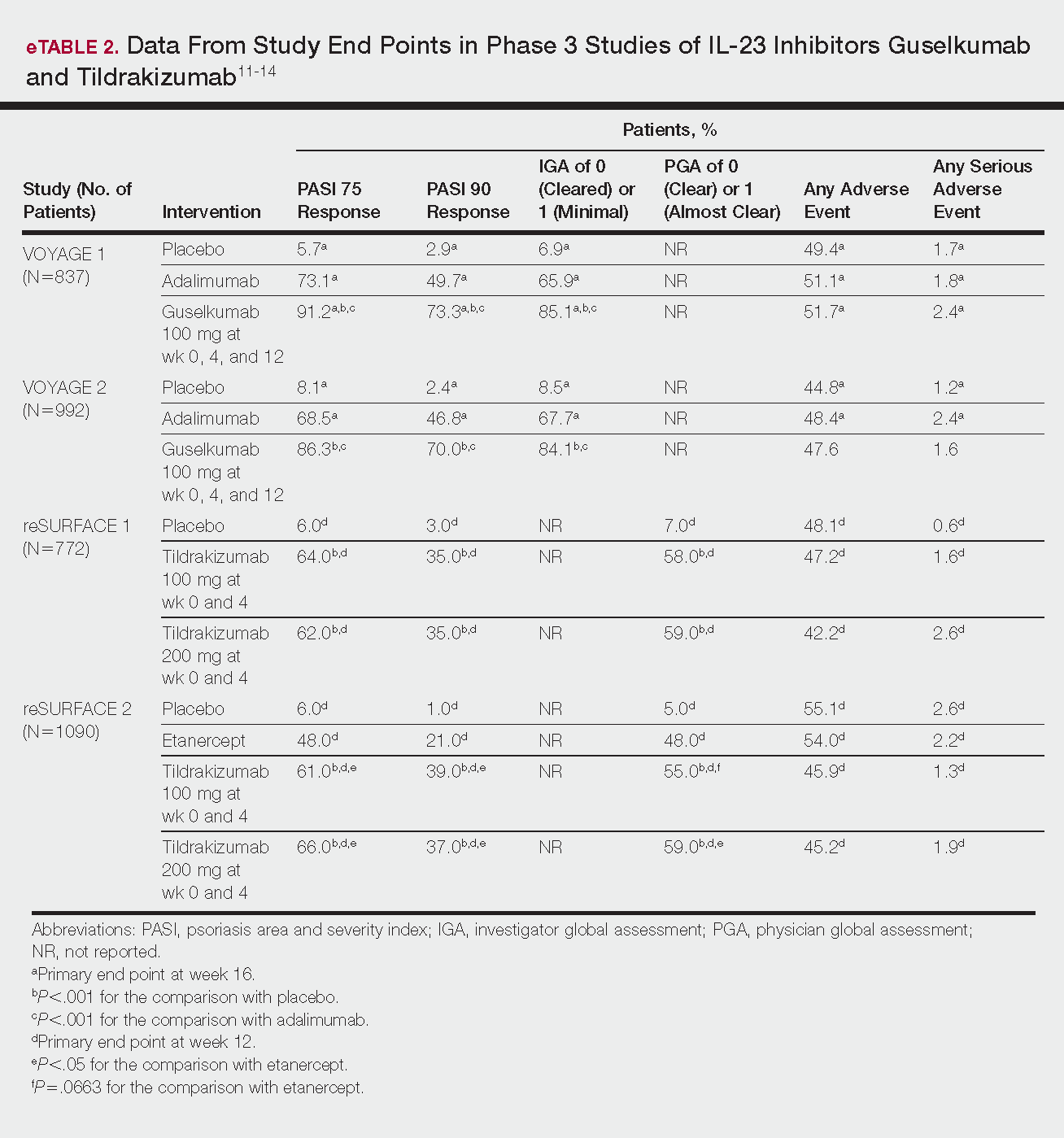

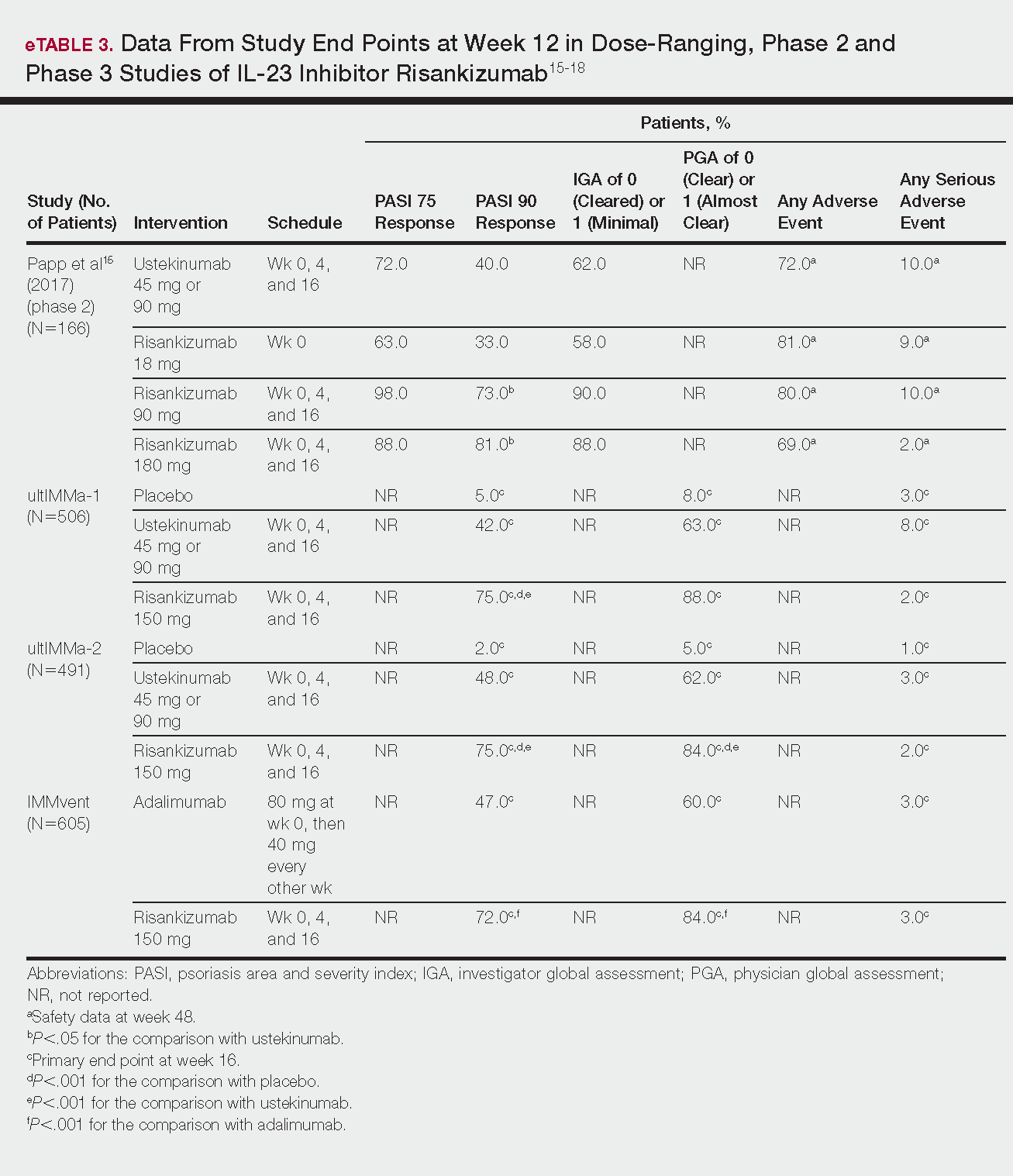

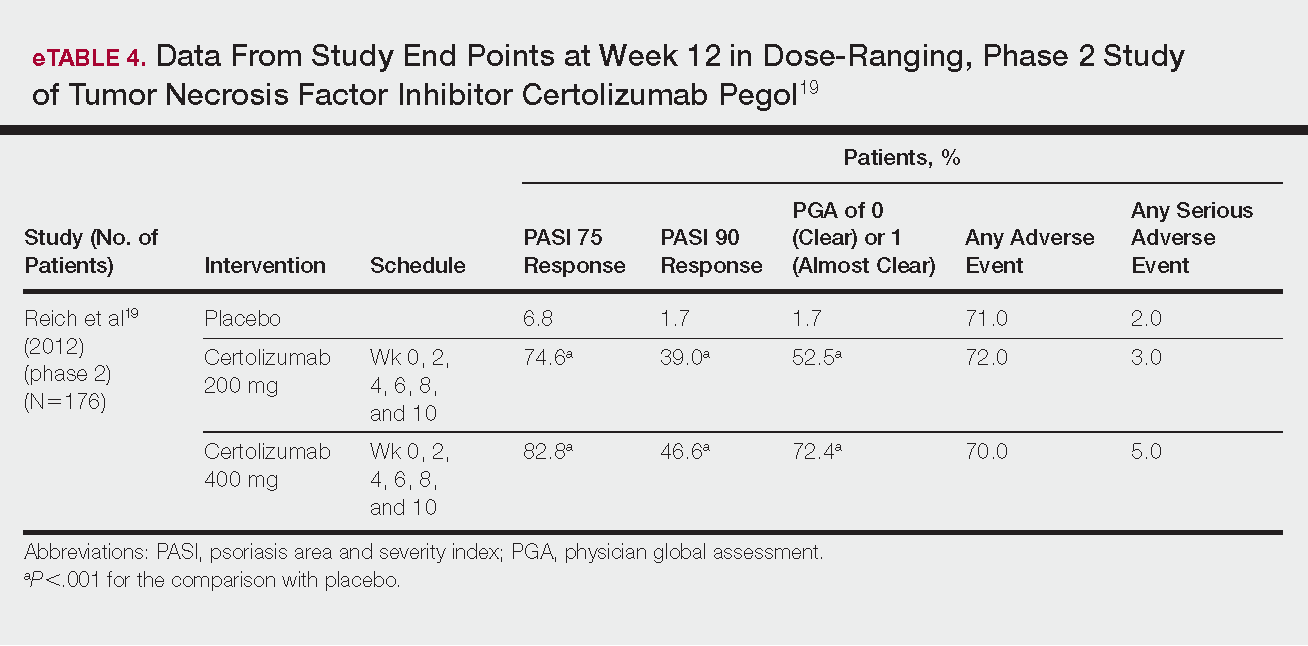

Phase 3 clinical trial design, efficacy, and adverse events (AEs) for ixekizumab and brodalumab are reported in eTable 15-10 and for guselkumab and tildrakizumab in eTable 2.11-14 Phase 2 clinical trial design, efficacy, and AEs are presented for risankizumab in eTable 315-18 and for certolizumab pegol in eTable 4.17,19 No published clinical trial data were found for bimekizumab.

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

This recombinant, high-affinity IgG4κ antibody selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A.5,6 Three phase 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—evaluated ixekizumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.7

The 3 UNCOVER trials were randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of 1296, 1224, and 1346 patients, respectively, assigned to a placebo group; a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks; and a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks. Both ixekizumab groups received a loading dose of 160 mg at week 0.5,6 UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 also included a comparator group of patients on etanercept 50 mg.5 Co-primary end points included the percentage of patients reaching a psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 75 and with a static physician global assessment (PGA) score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 12.5,6

Ixekizumab achieved greater efficacy than placebo: 89.1%, 89.7%, and 87.3% of patients achieved PASI 75 in the every 2-week dosing group, and 82.6%, 77.5% and 84.2% achieved PASI 75 in the every 4-week dosing group in UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3, respectively (P<.001 for both treatment arms compared to placebo in all trials). The percentage of patients achieving a static PGA score of 0 or 1 also was higher in the ixekizumab groups in the 2-week and 4-week dosing groups in all UNCOVER trials—81.8% and 76.4% in UNCOVER-1, 83.2% and 72.9% in UNCOVER-2, and 80.5% and 75.4% in UNCOVER-3—compared to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 6.7% in the placebo groups of the 3 trials (P<.001 for both ixekizumab groups compared to placebo in all trials).5,6 Ixekizumab also was found to be more effective than etanercept for both co-primary end points in both UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 (eTable 1).5

Safety data for all UNCOVER trials were pooled and reported.6 At week 12 the rate of at least 1 AE was 58.4% in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks and 58.8% in patients on ixekizumab every 4 weeks compared to 54.0% in the etanercept group in UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 and 46.8% in the placebo group. At week 12, 72 nonfatal serious AEs were reported: 12 in the placebo group, 14 in the etanercept group, 20 in the ixekizumab every 2 weeks group, and 26 in the ixekizumab every 4 weeks group.6

The most common AE across all groups was nasopharyngitis. Overall, infections were more frequent in patients treated with ixekizumab than in patients treated with placebo or etanercept. Specifically, oral candidiasis occurred more frequently in the ixekizumab groups, with a higher rate in the 2-week dosing group than in the 4-week dosing group.6 Two myocardial infarctions (MIs) occurred: 1 in the etanercept group and 1 in the placebo group.5

Brodalumab

This human monoclonal antibody binds to IL-17ra.8,9 Three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3—evaluated its use for plaque psoriasis.10

In AMAGINE-1 (N=661), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), or placebo.8 In AMAGINE-2 (N=1831) and AMAGINE-3 (N=1881), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), ustekinumab 45 mg or 90 mg by weight (at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks thereafter), or placebo. In all trials, patients on brodalumab received a dose at week 0 and week 1. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at 12 weeks compared to placebo and to ustekinumab (in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 only).8

At week 12, 83.3%, 86.3%, and 85.1% of patients on brodalumab 210 mg, and 60.3%, 66.6%, and 69.2% of patients on brodalumab 140 mg, achieved PASI 75 in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively, compared to 2.7%, 8.1%, and 6.0% in the placebo groups (P<.001 between both brodalumab groups and placebo in all trials).8 Both brodalumab groups were noninferior but not significantly superior to ustekinumab, which achieved a PASI 75 of 70.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 69.3% in AMAGINE-3. The PASI 90 rate was higher, however, in both brodalumab groups compared to ustekinumab but significance was not reported (eTable 1).9 For both brodalumab groups, significantly more patients achieved a static PGA value of 0 or 1 compared to placebo (P<.001 across all trials). However, only the brodalumab 210-mg group achieved a significantly higher rate of static PGA 0 or 1 compared to ustekinumab in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 (P<.001).9

After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 AE was 59.0%, 57.8%, and 56.8% in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively; 58.0%, 60.1%, and 52.6% in the brodalumab 140-mg group; and 51.0%, 53.4%, and 48.6% in the placebo group. Patients taking ustekinumab had an AE rate of 59.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 53.7% in AMAGINE-3. The most common AE was nasopharyngitis, followed by upper respiratory infection (URI) and headache across all trials.8,9 Serious AEs were rare: 10 in AMAGINE-1, 31 in AMAGINE-2, and 24 in AMAGINE-3 across all groups. One death occurred from stroke in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-2.9

IL-23 Inhibitors

Guselkumab

This drug is a human IgG1κ antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby inhibiting IL-23 signaling.11,12 Guselkumab was approved by the FDA in July 2017 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13

VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 were phase 3, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials of 837 and 992 patients, respectively, randomized to receive adalimumab (80 mg at week 0 and 40 mg at week 1, then at 40 mg every 2 weeks thereafter), guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 12, or placebo.11 Co-primary end points for both trials were the percentage of patients reaching PASI 90 and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 16.11

By week 16 of both trials, PASI 90 values were statistically superior for guselkumab (VOYAGE 1, 73.3%; VOYAGE 2, 70.0%) compared to adalimumab (VOYAGE 1, 49.7%; VOYAGE 2, 46.8%) and placebo (VOYAGE 1, 2.9%; VOYAGE 2, 2.4%)(P<.001). Moreover, patients on guselkumab achieved a higher rate of IGA values of 0 and 1 at week 12 (85.1% in VOYAGE 1 and 84.1% in VOYAGE 2) than patients on adalimumab (65.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 67.7% in VOYAGE 2) and placebo (6.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 8.5% in VOYAGE 2)(P<.001).11,12

The frequency of AEs was comparable across all groups in both trials.11,12 During the 16-week treatment period, 51.7% and 47.6% of the guselkumab groups in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 51.1% and 48.4% of the adalimumab groups; and 49.4% and 44.8% of the placebo groups reported at least 1 AE. The most common AEs in all groups were nasopharyngitis, headache, and URI.11,12

Serious AEs also occurred at similar rates: 2.4% and 1.6% in the guselkumab group in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 2.4% and 1.8% in the adalimumab group; and 1.7% and 1.2% in the placebo group.11,12 One case of malignancy occurred in the VOYAGE 1 trial: basal cell carcinoma in the guselkumab group.11 Three major cardiovascular events occurred across both trials: 1 MI in the guselkumab group in each trial and 1 MI in the adalimumab group in VOYAGE 1.11,12

Tildrakizumab

A high-affinity, humanized IgG1κ antibody, tildrakizumab targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. As of February 2018, 2 double-blind, randomized phase 3 trials have studied tildrakizumab with published results: reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2.14

reSURFACE 1 (N=772) and reSURFACE 2 (N=1090) randomized patients to receive tildrakizumab 100 or 200 mg (at weeks 0 and 4), etanercept 50 mg (twice weekly) for 12 weeks (reSURFACE 2 only), or placebo. Co-primary end points were the percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 and the percentage of patients achieving a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.14

In reSURFACE 1, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab attained PASI 75 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 62.0%; 100 mg, 64.0%; and placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo). Moreover, significantly proportionally more patients received a PGA score of 0 or 1 compared to placebo: 100 mg, 59%; 200 mg, 58.0%; placebo, 7.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

In reSURFACE 2, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab achieved PASI 75 compared to etanercept and placebo at week 12: 200 mg, 66.0%; 100mg, 61.0%; etanercept, 48.0%; placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo; P<.05 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to etanercept). Additionally, significantly more patients in the tildrakizumab groups experienced a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 59%; 100 mg, 55.0%; placebo, 5% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

Adverse events were reported at a similar rate across all groups. For reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2, at least 1 AE by week 12 was reported by 42.2% and 45.2% of patients in the 200-mg group; 47.2% and 45.9% in the 100-mg group; and 48.1% and 55.1% in the placebo groups.14The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, URI (reSURFACE 1), and erythema at the injection site (reSURFACE 2). One case of serious infection was reported in each of the tildrakizumab groups: 1 case of drug-related hypersensitivity reaction in the 200-mg group, and 1 major cardiovascular event in the 100-mg group of reSURFACE 1. There was 1 serious AE in reSURFACE 2 that led to death in which the cause was undetermined.14

Risankizumab

This humanized IgG1 antibody binds the p19 unit of IL-23.15,16 The drug is undergoing 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—for which only preliminary data have been published and are reported here.16,17 There is 1 phase 2 randomized, dose-ranging trial with published data.15

ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2 comprised 506 and 491 patients, respectively, randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16), ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg, by weight, at weeks 0, 4, and 16), or placebo. Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2, 75.0% and 75.0% of patients on risankizumab 150 mg achieved PASI 90 compared to 42.0% and 48.0% on ustekinumab and 5.0% and 2.0% on placebo at 16 weeks (P<.001 between both placebo and ustekinumab in both trials).17 In both trials, patients receiving risankizumab achieved higher rates of a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (88.0% and 84.0%) compared to ustekinumab (63.0% and 62.0%) and placebo (8.0% and 5.0%) at 16 weeks (P<.001 for both trials).18

At week 16, 2.0% of patients on risankizumab reported a serious AE in both trials, compared to 8.0% and 3.0% of patients on ustekinumab and 3.0% and 1.0% on placebo. No new safety concerns were noted.17

In the phase 3 IMMvent trial, 605 patients were randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16) or adalimumab (80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, then 40 mg every 2 weeks). Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In IMMvent, risankizumab was significantly more effective than adalimumab for PASI 75 (risankizumab, 72.0%; adalimumab, 47.0%) and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (risankizumab 84.0%; adalimumab, 60.0%) (P<.001 risankizumab compared to adalimumab for both end points).17

At week 16, serious AEs were reported in 3.0% of patients on risankizumab and 3.0% of patients on adalimumab. One patient receiving risankizumab died of an acute MI during the treatment phase.17

TNF Inhibitor

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a human PEGylated anti-TNF agent. In vitro studies have shown that certolizumab binds to soluble and membrane-bound TNF.19 Unlike other TNF inhibitors, certolizumab pegol is a Fab‘ portion of anti-TNF conjugated to a molecule of polyethylene glycol.19 The drug is approved in the United States for treating psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, and rheumatoid arthritis; its potential for treating psoriasis has been confirmed. Results of 1 phase 2 trial have been published19; data from 3 phase 3 trials are forthcoming.

This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 study comprised 176 patients who received certolizumab 200 mg, certolizumab 400 mg, or placebo. The dosing schedule was 400 mg at week 0, followed by either 200 or 400 mg every other week until week 10. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.19

Certolizumab was significantly more effective than placebo at week 12: 74.6% of the 200-mg group and 82.8% of the 400-mg group achieved PASI 75 compared to 6.8% of the placebo group (P<.001). Certolizumab also performed better for the PGA score: 52.5% and 72.4% of patients attained a score of 0 or 1 in the 200-mg and 400-mg groups compared to 1.7% in the placebo group.19

Adverse events were reported equally across all groups: 72% of patients in the 200-mg group, 70% in the 400-mg group, and 71% in the placebo group reported at least 1 AE, most commonly nasopharyngitis, headache, and pruritis.19

COMMENT

With the development of new insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis, therapies that are targeted toward key cytokines may contribute to improved management of the disease. The results of these clinical trials demonstrate numerous promising options for psoriatic patients.

IL-17 Inhibitors Ixekizumab and Brodalumab

When comparing these 2 biologics, it is important to consider that these studies were not performed head to head, thereby inhibiting direct comparisons. Moreover, dosage ranges of the investigative drugs were not identical, which also makes comparisons challenging. However, when looking at the highest dosages of ixekizumab and brodalumab, results indicate that ixekizumab may be slightly more effective than brodalumab based on the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (eTable 1).

Phase 3 trials have shown ixekizumab to maintain efficacy over 60 weeks of treatment.6 Ixekizumab also has been shown to alleviate other symptoms of psoriasis, such as itching, pain, and nail involvement.20,21 Furthermore, ixekizumab appears to be equally effective in patients with or without prior exposure to biologics22; therefore, ixekizumab may benefit patients who have not experienced success with other biologics.

Across the UNCOVER trials, 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease were reported in patients receiving ixekizumab (ulcerative colitis in 7; Crohn disease in 4)6; it appears that at least 3 of these cases were new diagnoses. In light of a study suggesting that IL-17A might have a protective function in the intestine,23 these findings may have important clinical implications and require follow-up studies.

Brodalumab also has been shown to maintain efficacy and acceptable safety for as long as 120 weeks.24 In the extension period of the AMAGINE-1 trial, patients who experienced a return of disease during a withdrawal period recaptured static PGA success with re-treatment for 12 weeks (re-treatment was successful in 97% of those given a dosage of 210 mg and in 84% of those given 140 mg).8

Furthermore, phase 2 trials also have shown that brodalumab is effective in patients with a history of biologic use.25 Across all AMAGINE trials, only 1 case of Crohn disease was reported in a patient taking brodalumab.9 There are concerns about depression, despite data from AMAGINE-1 stating patients on brodalumab actually had greater improvements in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores after 12 weeks of treatment (P<.001) for both brodalumab 140 mg and 210 mg compared to placebo.8 Regardless, brodalumab has a black-box warning for suicidal ideation and behavior, and availability is restricted through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.26

Bimekizumab

Although no phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trial data have been published for bimekizumab (phase 2 trials are underway), it has been shown in a phase 1 trial to be effective for psoriasis. Bimekizumab also is unique; it is the first dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F.18

IL-23 Inhibitors Guselkumab, Tildrakizumab, and Risankizumab

Making comparisons among the IL-23 inhibitors also is difficult; studies were not head-to-head comparison trials, and the VOYAGE and reSURFACE studies used different time points for primary end points. Furthermore, only phase 2 trial data are available for risankizumab. Despite these limitations, results of these trials suggest that guselkumab and risankizumab may be slightly more efficacious than tildrakizumab. However, future studies, including head-to-head studies, would ultimately provide further information on how these agents compare.

Guselkumab was shown to remain efficacious at 48 weeks, though patients on maintenance dosing had better results than those who were re-treated.12 Moreover, guselkumab was found to be effective in hard-to-treat areas, such as the scalp,11 and in patients who did not respond to adalimumab. Guselkumab may therefore benefit patients who have experienced limited clinical improvement on other biologics.12

Tildrakizumab was shown to improve PASI 75 and PGA scores through week 28 of treatment. Moreover, a higher percentage of patients taking tildrakizumab scored 0 or 1 on the dermatology life quality index, suggesting that the drug improves quality of life.14 No specific safety concerns arose in either reSURFACE trial; however, long-term studies are needed for further evaluation.

Risankizumab appears to be a promising new therapy based on phase 2 trial results. Improvements also were seen in dermatology life quality index scores, scalp and fingernail symptoms, and palmoplantar psoriasis.15 Of note, neutralizing antidrug antibodies were found in 3 patients during this study,15 which may present potential problems for long-term efficacy. However, preliminary data from 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—are promising.17

CONCLUSION

Advances in the understanding of psoriasis have led to new targeted therapies. Ongoing clinical trials have shown encouraging results for treating physical and psychological symptoms of psoriasis. The findings of these trials support the idea that therapies targeting IL-23, specifically its p19 subunit, are effective against psoriasis while sparing IL-12. Long-term data from open-label extension studies would help guide clinical recommendations regarding the safety profiles of these agents and determine their long-term utility.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23; discussion, ii24, ii25.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Amin M, Darji K, No DJ, et al. Review of phase III trial data on IL-23 inhibitors tildrakizumab and guselkumab for psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1627-1632.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:273-279.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al; UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 investigators. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 study group, UNCOVER-2 study group, UNCOVER-3 study group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug Taltz [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; March 22, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm491872.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Mentor A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 15, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm541981.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:405-417.

- Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:418-431.

- Janssen announces U.S. FDA approval of Tremfya™ (guselkumab) for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Horsham, PA: Johnson & Johnson; July 13, 2017. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/janssen-announces-us-fda-approval-of-tremfya-guselkumab-for-the-treatment-of-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomized controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276-288.

- Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1551-1560.

- Risankizumab. AbbVie Inc website. https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/pipeline/risankizumab.html. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Risankizumab meets all co-primary and ranked secondary endpoints, achieving significantly greater efficacy versus standard biologic therapies in three pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies [news release]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; October 26, 2017. https://news.abbvie.com/news/risankizumab-meets-all-co-primary-and-ranked-secondary-endpoints-achieving-significantly-greater-efficacy-versus-standard-biologic-therapies-in-three-pivotal-phase-3-psoriasis-studies.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Glatt S, Helmer E, Haier B, et al. First-in-human randomized study of bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody and selective dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F, in mild psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:991-1001.

- Reich K, Ortonne JP, Gottlieb AB, et al. Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab‘ certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:180-190.

- Kimball AB, Luger T, Gottlieb A, et al. Impact of ixekizumab on psoriasis itch severity and other psoriasis symptoms: results from 3 phase III psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1156-1161.

- Dennehy EB, Zhang L, Amato D, et al. Ixekizumab is effective in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with significant nail involvement: results from UNCOVER 3. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:958-961.

- Gottlieb AB, Lacour JP, Korman N, et al. Treatment outcomes with ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have not received prior biological therapies: an integrated analysis of two phase III randomized studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:679-685.

- Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitsky S, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693-1700.

- Papp K, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Safety and efficacy of brodalumab for psoriasis after 120 weeks of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1183-1190.

- Papp K, Menter A, Strober B, et al. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in subpopulations of patients with difficult-to-treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:436-439.

- SILIQ [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen, Inc; 2017.

Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disease estimated to affect 2.8% of the US population.1 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to involve a complex process triggered by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that induce tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α secretion by keratinocytes, which in turn activates dendritic cells. Activated dendritic cells produce IL-23, leading to helper T cell (TH17) differentiation.2,3 TH17 cells secrete IL-17A, which has been shown to promote psoriatic skin changes.4 Therefore, TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17A have been recognized as key targets for psoriasis therapy.

The newest biologic agents targeting IL-17–mediated pathways include ixekizumab, brodalumab, and bimekizumab. Secukinumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved IL-17 inhibitor, has been available since 2015 and therefore is not included in this review. IL-23 inhibitors that are FDA approved or being evaluated in clinical trials include guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab. In addition, certolizumab pegol, a TNF-α inhibitor, is being studied for use in psoriasis.

METHODS

We reviewed the published results of phase 3 clinical trials for ixekizumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab, and certolizumab pegol. We performed an English-language literature search (January 1, 2012 to October 15, 2017) of articles indexed for PubMed/MEDLINE using the following combinations of keywords: IL-23 and psoriasis; IL-17 and psoriasis; tumor necrosis factor and psoriasis; [drug name] and psoriasis. If data from phase 3 clinical trials were not yet available, data from phase 2 clinical trials were incorporated in our analysis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources.

RESULTS

Phase 3 clinical trial design, efficacy, and adverse events (AEs) for ixekizumab and brodalumab are reported in eTable 15-10 and for guselkumab and tildrakizumab in eTable 2.11-14 Phase 2 clinical trial design, efficacy, and AEs are presented for risankizumab in eTable 315-18 and for certolizumab pegol in eTable 4.17,19 No published clinical trial data were found for bimekizumab.

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

This recombinant, high-affinity IgG4κ antibody selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A.5,6 Three phase 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—evaluated ixekizumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.7

The 3 UNCOVER trials were randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of 1296, 1224, and 1346 patients, respectively, assigned to a placebo group; a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks; and a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks. Both ixekizumab groups received a loading dose of 160 mg at week 0.5,6 UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 also included a comparator group of patients on etanercept 50 mg.5 Co-primary end points included the percentage of patients reaching a psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 75 and with a static physician global assessment (PGA) score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 12.5,6

Ixekizumab achieved greater efficacy than placebo: 89.1%, 89.7%, and 87.3% of patients achieved PASI 75 in the every 2-week dosing group, and 82.6%, 77.5% and 84.2% achieved PASI 75 in the every 4-week dosing group in UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3, respectively (P<.001 for both treatment arms compared to placebo in all trials). The percentage of patients achieving a static PGA score of 0 or 1 also was higher in the ixekizumab groups in the 2-week and 4-week dosing groups in all UNCOVER trials—81.8% and 76.4% in UNCOVER-1, 83.2% and 72.9% in UNCOVER-2, and 80.5% and 75.4% in UNCOVER-3—compared to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 6.7% in the placebo groups of the 3 trials (P<.001 for both ixekizumab groups compared to placebo in all trials).5,6 Ixekizumab also was found to be more effective than etanercept for both co-primary end points in both UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 (eTable 1).5

Safety data for all UNCOVER trials were pooled and reported.6 At week 12 the rate of at least 1 AE was 58.4% in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks and 58.8% in patients on ixekizumab every 4 weeks compared to 54.0% in the etanercept group in UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 and 46.8% in the placebo group. At week 12, 72 nonfatal serious AEs were reported: 12 in the placebo group, 14 in the etanercept group, 20 in the ixekizumab every 2 weeks group, and 26 in the ixekizumab every 4 weeks group.6

The most common AE across all groups was nasopharyngitis. Overall, infections were more frequent in patients treated with ixekizumab than in patients treated with placebo or etanercept. Specifically, oral candidiasis occurred more frequently in the ixekizumab groups, with a higher rate in the 2-week dosing group than in the 4-week dosing group.6 Two myocardial infarctions (MIs) occurred: 1 in the etanercept group and 1 in the placebo group.5

Brodalumab

This human monoclonal antibody binds to IL-17ra.8,9 Three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3—evaluated its use for plaque psoriasis.10

In AMAGINE-1 (N=661), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), or placebo.8 In AMAGINE-2 (N=1831) and AMAGINE-3 (N=1881), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), ustekinumab 45 mg or 90 mg by weight (at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks thereafter), or placebo. In all trials, patients on brodalumab received a dose at week 0 and week 1. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at 12 weeks compared to placebo and to ustekinumab (in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 only).8

At week 12, 83.3%, 86.3%, and 85.1% of patients on brodalumab 210 mg, and 60.3%, 66.6%, and 69.2% of patients on brodalumab 140 mg, achieved PASI 75 in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively, compared to 2.7%, 8.1%, and 6.0% in the placebo groups (P<.001 between both brodalumab groups and placebo in all trials).8 Both brodalumab groups were noninferior but not significantly superior to ustekinumab, which achieved a PASI 75 of 70.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 69.3% in AMAGINE-3. The PASI 90 rate was higher, however, in both brodalumab groups compared to ustekinumab but significance was not reported (eTable 1).9 For both brodalumab groups, significantly more patients achieved a static PGA value of 0 or 1 compared to placebo (P<.001 across all trials). However, only the brodalumab 210-mg group achieved a significantly higher rate of static PGA 0 or 1 compared to ustekinumab in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 (P<.001).9

After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 AE was 59.0%, 57.8%, and 56.8% in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively; 58.0%, 60.1%, and 52.6% in the brodalumab 140-mg group; and 51.0%, 53.4%, and 48.6% in the placebo group. Patients taking ustekinumab had an AE rate of 59.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 53.7% in AMAGINE-3. The most common AE was nasopharyngitis, followed by upper respiratory infection (URI) and headache across all trials.8,9 Serious AEs were rare: 10 in AMAGINE-1, 31 in AMAGINE-2, and 24 in AMAGINE-3 across all groups. One death occurred from stroke in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-2.9

IL-23 Inhibitors

Guselkumab

This drug is a human IgG1κ antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby inhibiting IL-23 signaling.11,12 Guselkumab was approved by the FDA in July 2017 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13

VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 were phase 3, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials of 837 and 992 patients, respectively, randomized to receive adalimumab (80 mg at week 0 and 40 mg at week 1, then at 40 mg every 2 weeks thereafter), guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 12, or placebo.11 Co-primary end points for both trials were the percentage of patients reaching PASI 90 and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 16.11

By week 16 of both trials, PASI 90 values were statistically superior for guselkumab (VOYAGE 1, 73.3%; VOYAGE 2, 70.0%) compared to adalimumab (VOYAGE 1, 49.7%; VOYAGE 2, 46.8%) and placebo (VOYAGE 1, 2.9%; VOYAGE 2, 2.4%)(P<.001). Moreover, patients on guselkumab achieved a higher rate of IGA values of 0 and 1 at week 12 (85.1% in VOYAGE 1 and 84.1% in VOYAGE 2) than patients on adalimumab (65.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 67.7% in VOYAGE 2) and placebo (6.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 8.5% in VOYAGE 2)(P<.001).11,12

The frequency of AEs was comparable across all groups in both trials.11,12 During the 16-week treatment period, 51.7% and 47.6% of the guselkumab groups in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 51.1% and 48.4% of the adalimumab groups; and 49.4% and 44.8% of the placebo groups reported at least 1 AE. The most common AEs in all groups were nasopharyngitis, headache, and URI.11,12

Serious AEs also occurred at similar rates: 2.4% and 1.6% in the guselkumab group in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 2.4% and 1.8% in the adalimumab group; and 1.7% and 1.2% in the placebo group.11,12 One case of malignancy occurred in the VOYAGE 1 trial: basal cell carcinoma in the guselkumab group.11 Three major cardiovascular events occurred across both trials: 1 MI in the guselkumab group in each trial and 1 MI in the adalimumab group in VOYAGE 1.11,12

Tildrakizumab

A high-affinity, humanized IgG1κ antibody, tildrakizumab targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. As of February 2018, 2 double-blind, randomized phase 3 trials have studied tildrakizumab with published results: reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2.14

reSURFACE 1 (N=772) and reSURFACE 2 (N=1090) randomized patients to receive tildrakizumab 100 or 200 mg (at weeks 0 and 4), etanercept 50 mg (twice weekly) for 12 weeks (reSURFACE 2 only), or placebo. Co-primary end points were the percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 and the percentage of patients achieving a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.14

In reSURFACE 1, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab attained PASI 75 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 62.0%; 100 mg, 64.0%; and placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo). Moreover, significantly proportionally more patients received a PGA score of 0 or 1 compared to placebo: 100 mg, 59%; 200 mg, 58.0%; placebo, 7.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

In reSURFACE 2, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab achieved PASI 75 compared to etanercept and placebo at week 12: 200 mg, 66.0%; 100mg, 61.0%; etanercept, 48.0%; placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo; P<.05 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to etanercept). Additionally, significantly more patients in the tildrakizumab groups experienced a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 59%; 100 mg, 55.0%; placebo, 5% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

Adverse events were reported at a similar rate across all groups. For reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2, at least 1 AE by week 12 was reported by 42.2% and 45.2% of patients in the 200-mg group; 47.2% and 45.9% in the 100-mg group; and 48.1% and 55.1% in the placebo groups.14The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, URI (reSURFACE 1), and erythema at the injection site (reSURFACE 2). One case of serious infection was reported in each of the tildrakizumab groups: 1 case of drug-related hypersensitivity reaction in the 200-mg group, and 1 major cardiovascular event in the 100-mg group of reSURFACE 1. There was 1 serious AE in reSURFACE 2 that led to death in which the cause was undetermined.14

Risankizumab

This humanized IgG1 antibody binds the p19 unit of IL-23.15,16 The drug is undergoing 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—for which only preliminary data have been published and are reported here.16,17 There is 1 phase 2 randomized, dose-ranging trial with published data.15

ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2 comprised 506 and 491 patients, respectively, randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16), ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg, by weight, at weeks 0, 4, and 16), or placebo. Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2, 75.0% and 75.0% of patients on risankizumab 150 mg achieved PASI 90 compared to 42.0% and 48.0% on ustekinumab and 5.0% and 2.0% on placebo at 16 weeks (P<.001 between both placebo and ustekinumab in both trials).17 In both trials, patients receiving risankizumab achieved higher rates of a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (88.0% and 84.0%) compared to ustekinumab (63.0% and 62.0%) and placebo (8.0% and 5.0%) at 16 weeks (P<.001 for both trials).18

At week 16, 2.0% of patients on risankizumab reported a serious AE in both trials, compared to 8.0% and 3.0% of patients on ustekinumab and 3.0% and 1.0% on placebo. No new safety concerns were noted.17

In the phase 3 IMMvent trial, 605 patients were randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16) or adalimumab (80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, then 40 mg every 2 weeks). Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In IMMvent, risankizumab was significantly more effective than adalimumab for PASI 75 (risankizumab, 72.0%; adalimumab, 47.0%) and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (risankizumab 84.0%; adalimumab, 60.0%) (P<.001 risankizumab compared to adalimumab for both end points).17

At week 16, serious AEs were reported in 3.0% of patients on risankizumab and 3.0% of patients on adalimumab. One patient receiving risankizumab died of an acute MI during the treatment phase.17

TNF Inhibitor

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a human PEGylated anti-TNF agent. In vitro studies have shown that certolizumab binds to soluble and membrane-bound TNF.19 Unlike other TNF inhibitors, certolizumab pegol is a Fab‘ portion of anti-TNF conjugated to a molecule of polyethylene glycol.19 The drug is approved in the United States for treating psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, and rheumatoid arthritis; its potential for treating psoriasis has been confirmed. Results of 1 phase 2 trial have been published19; data from 3 phase 3 trials are forthcoming.

This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 study comprised 176 patients who received certolizumab 200 mg, certolizumab 400 mg, or placebo. The dosing schedule was 400 mg at week 0, followed by either 200 or 400 mg every other week until week 10. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.19

Certolizumab was significantly more effective than placebo at week 12: 74.6% of the 200-mg group and 82.8% of the 400-mg group achieved PASI 75 compared to 6.8% of the placebo group (P<.001). Certolizumab also performed better for the PGA score: 52.5% and 72.4% of patients attained a score of 0 or 1 in the 200-mg and 400-mg groups compared to 1.7% in the placebo group.19

Adverse events were reported equally across all groups: 72% of patients in the 200-mg group, 70% in the 400-mg group, and 71% in the placebo group reported at least 1 AE, most commonly nasopharyngitis, headache, and pruritis.19

COMMENT

With the development of new insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis, therapies that are targeted toward key cytokines may contribute to improved management of the disease. The results of these clinical trials demonstrate numerous promising options for psoriatic patients.

IL-17 Inhibitors Ixekizumab and Brodalumab

When comparing these 2 biologics, it is important to consider that these studies were not performed head to head, thereby inhibiting direct comparisons. Moreover, dosage ranges of the investigative drugs were not identical, which also makes comparisons challenging. However, when looking at the highest dosages of ixekizumab and brodalumab, results indicate that ixekizumab may be slightly more effective than brodalumab based on the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (eTable 1).

Phase 3 trials have shown ixekizumab to maintain efficacy over 60 weeks of treatment.6 Ixekizumab also has been shown to alleviate other symptoms of psoriasis, such as itching, pain, and nail involvement.20,21 Furthermore, ixekizumab appears to be equally effective in patients with or without prior exposure to biologics22; therefore, ixekizumab may benefit patients who have not experienced success with other biologics.

Across the UNCOVER trials, 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease were reported in patients receiving ixekizumab (ulcerative colitis in 7; Crohn disease in 4)6; it appears that at least 3 of these cases were new diagnoses. In light of a study suggesting that IL-17A might have a protective function in the intestine,23 these findings may have important clinical implications and require follow-up studies.

Brodalumab also has been shown to maintain efficacy and acceptable safety for as long as 120 weeks.24 In the extension period of the AMAGINE-1 trial, patients who experienced a return of disease during a withdrawal period recaptured static PGA success with re-treatment for 12 weeks (re-treatment was successful in 97% of those given a dosage of 210 mg and in 84% of those given 140 mg).8

Furthermore, phase 2 trials also have shown that brodalumab is effective in patients with a history of biologic use.25 Across all AMAGINE trials, only 1 case of Crohn disease was reported in a patient taking brodalumab.9 There are concerns about depression, despite data from AMAGINE-1 stating patients on brodalumab actually had greater improvements in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores after 12 weeks of treatment (P<.001) for both brodalumab 140 mg and 210 mg compared to placebo.8 Regardless, brodalumab has a black-box warning for suicidal ideation and behavior, and availability is restricted through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.26

Bimekizumab

Although no phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trial data have been published for bimekizumab (phase 2 trials are underway), it has been shown in a phase 1 trial to be effective for psoriasis. Bimekizumab also is unique; it is the first dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F.18

IL-23 Inhibitors Guselkumab, Tildrakizumab, and Risankizumab

Making comparisons among the IL-23 inhibitors also is difficult; studies were not head-to-head comparison trials, and the VOYAGE and reSURFACE studies used different time points for primary end points. Furthermore, only phase 2 trial data are available for risankizumab. Despite these limitations, results of these trials suggest that guselkumab and risankizumab may be slightly more efficacious than tildrakizumab. However, future studies, including head-to-head studies, would ultimately provide further information on how these agents compare.

Guselkumab was shown to remain efficacious at 48 weeks, though patients on maintenance dosing had better results than those who were re-treated.12 Moreover, guselkumab was found to be effective in hard-to-treat areas, such as the scalp,11 and in patients who did not respond to adalimumab. Guselkumab may therefore benefit patients who have experienced limited clinical improvement on other biologics.12

Tildrakizumab was shown to improve PASI 75 and PGA scores through week 28 of treatment. Moreover, a higher percentage of patients taking tildrakizumab scored 0 or 1 on the dermatology life quality index, suggesting that the drug improves quality of life.14 No specific safety concerns arose in either reSURFACE trial; however, long-term studies are needed for further evaluation.

Risankizumab appears to be a promising new therapy based on phase 2 trial results. Improvements also were seen in dermatology life quality index scores, scalp and fingernail symptoms, and palmoplantar psoriasis.15 Of note, neutralizing antidrug antibodies were found in 3 patients during this study,15 which may present potential problems for long-term efficacy. However, preliminary data from 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—are promising.17

CONCLUSION

Advances in the understanding of psoriasis have led to new targeted therapies. Ongoing clinical trials have shown encouraging results for treating physical and psychological symptoms of psoriasis. The findings of these trials support the idea that therapies targeting IL-23, specifically its p19 subunit, are effective against psoriasis while sparing IL-12. Long-term data from open-label extension studies would help guide clinical recommendations regarding the safety profiles of these agents and determine their long-term utility.

Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune-mediated disease estimated to affect 2.8% of the US population.1 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to involve a complex process triggered by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that induce tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α secretion by keratinocytes, which in turn activates dendritic cells. Activated dendritic cells produce IL-23, leading to helper T cell (TH17) differentiation.2,3 TH17 cells secrete IL-17A, which has been shown to promote psoriatic skin changes.4 Therefore, TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17A have been recognized as key targets for psoriasis therapy.

The newest biologic agents targeting IL-17–mediated pathways include ixekizumab, brodalumab, and bimekizumab. Secukinumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved IL-17 inhibitor, has been available since 2015 and therefore is not included in this review. IL-23 inhibitors that are FDA approved or being evaluated in clinical trials include guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab. In addition, certolizumab pegol, a TNF-α inhibitor, is being studied for use in psoriasis.

METHODS

We reviewed the published results of phase 3 clinical trials for ixekizumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab, and certolizumab pegol. We performed an English-language literature search (January 1, 2012 to October 15, 2017) of articles indexed for PubMed/MEDLINE using the following combinations of keywords: IL-23 and psoriasis; IL-17 and psoriasis; tumor necrosis factor and psoriasis; [drug name] and psoriasis. If data from phase 3 clinical trials were not yet available, data from phase 2 clinical trials were incorporated in our analysis. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources.

RESULTS

Phase 3 clinical trial design, efficacy, and adverse events (AEs) for ixekizumab and brodalumab are reported in eTable 15-10 and for guselkumab and tildrakizumab in eTable 2.11-14 Phase 2 clinical trial design, efficacy, and AEs are presented for risankizumab in eTable 315-18 and for certolizumab pegol in eTable 4.17,19 No published clinical trial data were found for bimekizumab.

IL-17 Inhibitors

Ixekizumab

This recombinant, high-affinity IgG4κ antibody selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A.5,6 Three phase 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—evaluated ixekizumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.7

The 3 UNCOVER trials were randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trials of 1296, 1224, and 1346 patients, respectively, assigned to a placebo group; a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks; and a group treated with ixekizumab 80 mg every 4 weeks. Both ixekizumab groups received a loading dose of 160 mg at week 0.5,6 UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 also included a comparator group of patients on etanercept 50 mg.5 Co-primary end points included the percentage of patients reaching a psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) of 75 and with a static physician global assessment (PGA) score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 12.5,6

Ixekizumab achieved greater efficacy than placebo: 89.1%, 89.7%, and 87.3% of patients achieved PASI 75 in the every 2-week dosing group, and 82.6%, 77.5% and 84.2% achieved PASI 75 in the every 4-week dosing group in UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3, respectively (P<.001 for both treatment arms compared to placebo in all trials). The percentage of patients achieving a static PGA score of 0 or 1 also was higher in the ixekizumab groups in the 2-week and 4-week dosing groups in all UNCOVER trials—81.8% and 76.4% in UNCOVER-1, 83.2% and 72.9% in UNCOVER-2, and 80.5% and 75.4% in UNCOVER-3—compared to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 6.7% in the placebo groups of the 3 trials (P<.001 for both ixekizumab groups compared to placebo in all trials).5,6 Ixekizumab also was found to be more effective than etanercept for both co-primary end points in both UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 (eTable 1).5

Safety data for all UNCOVER trials were pooled and reported.6 At week 12 the rate of at least 1 AE was 58.4% in patients on ixekizumab every 2 weeks and 58.8% in patients on ixekizumab every 4 weeks compared to 54.0% in the etanercept group in UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 and 46.8% in the placebo group. At week 12, 72 nonfatal serious AEs were reported: 12 in the placebo group, 14 in the etanercept group, 20 in the ixekizumab every 2 weeks group, and 26 in the ixekizumab every 4 weeks group.6

The most common AE across all groups was nasopharyngitis. Overall, infections were more frequent in patients treated with ixekizumab than in patients treated with placebo or etanercept. Specifically, oral candidiasis occurred more frequently in the ixekizumab groups, with a higher rate in the 2-week dosing group than in the 4-week dosing group.6 Two myocardial infarctions (MIs) occurred: 1 in the etanercept group and 1 in the placebo group.5

Brodalumab

This human monoclonal antibody binds to IL-17ra.8,9 Three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials—AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3—evaluated its use for plaque psoriasis.10

In AMAGINE-1 (N=661), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), or placebo.8 In AMAGINE-2 (N=1831) and AMAGINE-3 (N=1881), patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 140 mg or 210 mg (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks), ustekinumab 45 mg or 90 mg by weight (at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks thereafter), or placebo. In all trials, patients on brodalumab received a dose at week 0 and week 1. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at 12 weeks compared to placebo and to ustekinumab (in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 only).8

At week 12, 83.3%, 86.3%, and 85.1% of patients on brodalumab 210 mg, and 60.3%, 66.6%, and 69.2% of patients on brodalumab 140 mg, achieved PASI 75 in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively, compared to 2.7%, 8.1%, and 6.0% in the placebo groups (P<.001 between both brodalumab groups and placebo in all trials).8 Both brodalumab groups were noninferior but not significantly superior to ustekinumab, which achieved a PASI 75 of 70.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 69.3% in AMAGINE-3. The PASI 90 rate was higher, however, in both brodalumab groups compared to ustekinumab but significance was not reported (eTable 1).9 For both brodalumab groups, significantly more patients achieved a static PGA value of 0 or 1 compared to placebo (P<.001 across all trials). However, only the brodalumab 210-mg group achieved a significantly higher rate of static PGA 0 or 1 compared to ustekinumab in AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 (P<.001).9

After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 AE was 59.0%, 57.8%, and 56.8% in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-1, AMAGINE-2, and AMAGINE-3, respectively; 58.0%, 60.1%, and 52.6% in the brodalumab 140-mg group; and 51.0%, 53.4%, and 48.6% in the placebo group. Patients taking ustekinumab had an AE rate of 59.0% in AMAGINE-2 and 53.7% in AMAGINE-3. The most common AE was nasopharyngitis, followed by upper respiratory infection (URI) and headache across all trials.8,9 Serious AEs were rare: 10 in AMAGINE-1, 31 in AMAGINE-2, and 24 in AMAGINE-3 across all groups. One death occurred from stroke in the brodalumab 210-mg group in AMAGINE-2.9

IL-23 Inhibitors

Guselkumab

This drug is a human IgG1κ antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23, thereby inhibiting IL-23 signaling.11,12 Guselkumab was approved by the FDA in July 2017 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13

VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 were phase 3, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator–controlled trials of 837 and 992 patients, respectively, randomized to receive adalimumab (80 mg at week 0 and 40 mg at week 1, then at 40 mg every 2 weeks thereafter), guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 12, or placebo.11 Co-primary end points for both trials were the percentage of patients reaching PASI 90 and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 16.11

By week 16 of both trials, PASI 90 values were statistically superior for guselkumab (VOYAGE 1, 73.3%; VOYAGE 2, 70.0%) compared to adalimumab (VOYAGE 1, 49.7%; VOYAGE 2, 46.8%) and placebo (VOYAGE 1, 2.9%; VOYAGE 2, 2.4%)(P<.001). Moreover, patients on guselkumab achieved a higher rate of IGA values of 0 and 1 at week 12 (85.1% in VOYAGE 1 and 84.1% in VOYAGE 2) than patients on adalimumab (65.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 67.7% in VOYAGE 2) and placebo (6.9% in VOYAGE 1 and 8.5% in VOYAGE 2)(P<.001).11,12

The frequency of AEs was comparable across all groups in both trials.11,12 During the 16-week treatment period, 51.7% and 47.6% of the guselkumab groups in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 51.1% and 48.4% of the adalimumab groups; and 49.4% and 44.8% of the placebo groups reported at least 1 AE. The most common AEs in all groups were nasopharyngitis, headache, and URI.11,12

Serious AEs also occurred at similar rates: 2.4% and 1.6% in the guselkumab group in VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2, respectively; 2.4% and 1.8% in the adalimumab group; and 1.7% and 1.2% in the placebo group.11,12 One case of malignancy occurred in the VOYAGE 1 trial: basal cell carcinoma in the guselkumab group.11 Three major cardiovascular events occurred across both trials: 1 MI in the guselkumab group in each trial and 1 MI in the adalimumab group in VOYAGE 1.11,12

Tildrakizumab

A high-affinity, humanized IgG1κ antibody, tildrakizumab targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. As of February 2018, 2 double-blind, randomized phase 3 trials have studied tildrakizumab with published results: reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2.14

reSURFACE 1 (N=772) and reSURFACE 2 (N=1090) randomized patients to receive tildrakizumab 100 or 200 mg (at weeks 0 and 4), etanercept 50 mg (twice weekly) for 12 weeks (reSURFACE 2 only), or placebo. Co-primary end points were the percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 and the percentage of patients achieving a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.14

In reSURFACE 1, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab attained PASI 75 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 62.0%; 100 mg, 64.0%; and placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo). Moreover, significantly proportionally more patients received a PGA score of 0 or 1 compared to placebo: 100 mg, 59%; 200 mg, 58.0%; placebo, 7.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

In reSURFACE 2, significantly more patients receiving tildrakizumab achieved PASI 75 compared to etanercept and placebo at week 12: 200 mg, 66.0%; 100mg, 61.0%; etanercept, 48.0%; placebo, 6.0% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo; P<.05 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to etanercept). Additionally, significantly more patients in the tildrakizumab groups experienced a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12 compared to placebo: 200 mg, 59%; 100 mg, 55.0%; placebo, 5% (P<.001 for both tildrakizumab groups compared to placebo).14

Adverse events were reported at a similar rate across all groups. For reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2, at least 1 AE by week 12 was reported by 42.2% and 45.2% of patients in the 200-mg group; 47.2% and 45.9% in the 100-mg group; and 48.1% and 55.1% in the placebo groups.14The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, URI (reSURFACE 1), and erythema at the injection site (reSURFACE 2). One case of serious infection was reported in each of the tildrakizumab groups: 1 case of drug-related hypersensitivity reaction in the 200-mg group, and 1 major cardiovascular event in the 100-mg group of reSURFACE 1. There was 1 serious AE in reSURFACE 2 that led to death in which the cause was undetermined.14

Risankizumab

This humanized IgG1 antibody binds the p19 unit of IL-23.15,16 The drug is undergoing 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—for which only preliminary data have been published and are reported here.16,17 There is 1 phase 2 randomized, dose-ranging trial with published data.15

ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2 comprised 506 and 491 patients, respectively, randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16), ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg, by weight, at weeks 0, 4, and 16), or placebo. Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In ultIMMa-1 and ultIMMa-2, 75.0% and 75.0% of patients on risankizumab 150 mg achieved PASI 90 compared to 42.0% and 48.0% on ustekinumab and 5.0% and 2.0% on placebo at 16 weeks (P<.001 between both placebo and ustekinumab in both trials).17 In both trials, patients receiving risankizumab achieved higher rates of a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (88.0% and 84.0%) compared to ustekinumab (63.0% and 62.0%) and placebo (8.0% and 5.0%) at 16 weeks (P<.001 for both trials).18

At week 16, 2.0% of patients on risankizumab reported a serious AE in both trials, compared to 8.0% and 3.0% of patients on ustekinumab and 3.0% and 1.0% on placebo. No new safety concerns were noted.17

In the phase 3 IMMvent trial, 605 patients were randomized to receive risankizumab (150 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16) or adalimumab (80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, then 40 mg every 2 weeks). Co-primary end points were PASI 90 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.17

In IMMvent, risankizumab was significantly more effective than adalimumab for PASI 75 (risankizumab, 72.0%; adalimumab, 47.0%) and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (risankizumab 84.0%; adalimumab, 60.0%) (P<.001 risankizumab compared to adalimumab for both end points).17

At week 16, serious AEs were reported in 3.0% of patients on risankizumab and 3.0% of patients on adalimumab. One patient receiving risankizumab died of an acute MI during the treatment phase.17

TNF Inhibitor

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol is a human PEGylated anti-TNF agent. In vitro studies have shown that certolizumab binds to soluble and membrane-bound TNF.19 Unlike other TNF inhibitors, certolizumab pegol is a Fab‘ portion of anti-TNF conjugated to a molecule of polyethylene glycol.19 The drug is approved in the United States for treating psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, and rheumatoid arthritis; its potential for treating psoriasis has been confirmed. Results of 1 phase 2 trial have been published19; data from 3 phase 3 trials are forthcoming.

This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 study comprised 176 patients who received certolizumab 200 mg, certolizumab 400 mg, or placebo. The dosing schedule was 400 mg at week 0, followed by either 200 or 400 mg every other week until week 10. Co-primary end points were PASI 75 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12.19

Certolizumab was significantly more effective than placebo at week 12: 74.6% of the 200-mg group and 82.8% of the 400-mg group achieved PASI 75 compared to 6.8% of the placebo group (P<.001). Certolizumab also performed better for the PGA score: 52.5% and 72.4% of patients attained a score of 0 or 1 in the 200-mg and 400-mg groups compared to 1.7% in the placebo group.19

Adverse events were reported equally across all groups: 72% of patients in the 200-mg group, 70% in the 400-mg group, and 71% in the placebo group reported at least 1 AE, most commonly nasopharyngitis, headache, and pruritis.19

COMMENT

With the development of new insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis, therapies that are targeted toward key cytokines may contribute to improved management of the disease. The results of these clinical trials demonstrate numerous promising options for psoriatic patients.

IL-17 Inhibitors Ixekizumab and Brodalumab

When comparing these 2 biologics, it is important to consider that these studies were not performed head to head, thereby inhibiting direct comparisons. Moreover, dosage ranges of the investigative drugs were not identical, which also makes comparisons challenging. However, when looking at the highest dosages of ixekizumab and brodalumab, results indicate that ixekizumab may be slightly more effective than brodalumab based on the percentage of patients who achieved a PASI 75 and a static PGA score of 0 or 1 (eTable 1).

Phase 3 trials have shown ixekizumab to maintain efficacy over 60 weeks of treatment.6 Ixekizumab also has been shown to alleviate other symptoms of psoriasis, such as itching, pain, and nail involvement.20,21 Furthermore, ixekizumab appears to be equally effective in patients with or without prior exposure to biologics22; therefore, ixekizumab may benefit patients who have not experienced success with other biologics.

Across the UNCOVER trials, 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease were reported in patients receiving ixekizumab (ulcerative colitis in 7; Crohn disease in 4)6; it appears that at least 3 of these cases were new diagnoses. In light of a study suggesting that IL-17A might have a protective function in the intestine,23 these findings may have important clinical implications and require follow-up studies.

Brodalumab also has been shown to maintain efficacy and acceptable safety for as long as 120 weeks.24 In the extension period of the AMAGINE-1 trial, patients who experienced a return of disease during a withdrawal period recaptured static PGA success with re-treatment for 12 weeks (re-treatment was successful in 97% of those given a dosage of 210 mg and in 84% of those given 140 mg).8

Furthermore, phase 2 trials also have shown that brodalumab is effective in patients with a history of biologic use.25 Across all AMAGINE trials, only 1 case of Crohn disease was reported in a patient taking brodalumab.9 There are concerns about depression, despite data from AMAGINE-1 stating patients on brodalumab actually had greater improvements in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores after 12 weeks of treatment (P<.001) for both brodalumab 140 mg and 210 mg compared to placebo.8 Regardless, brodalumab has a black-box warning for suicidal ideation and behavior, and availability is restricted through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.26

Bimekizumab

Although no phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trial data have been published for bimekizumab (phase 2 trials are underway), it has been shown in a phase 1 trial to be effective for psoriasis. Bimekizumab also is unique; it is the first dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F.18

IL-23 Inhibitors Guselkumab, Tildrakizumab, and Risankizumab

Making comparisons among the IL-23 inhibitors also is difficult; studies were not head-to-head comparison trials, and the VOYAGE and reSURFACE studies used different time points for primary end points. Furthermore, only phase 2 trial data are available for risankizumab. Despite these limitations, results of these trials suggest that guselkumab and risankizumab may be slightly more efficacious than tildrakizumab. However, future studies, including head-to-head studies, would ultimately provide further information on how these agents compare.

Guselkumab was shown to remain efficacious at 48 weeks, though patients on maintenance dosing had better results than those who were re-treated.12 Moreover, guselkumab was found to be effective in hard-to-treat areas, such as the scalp,11 and in patients who did not respond to adalimumab. Guselkumab may therefore benefit patients who have experienced limited clinical improvement on other biologics.12

Tildrakizumab was shown to improve PASI 75 and PGA scores through week 28 of treatment. Moreover, a higher percentage of patients taking tildrakizumab scored 0 or 1 on the dermatology life quality index, suggesting that the drug improves quality of life.14 No specific safety concerns arose in either reSURFACE trial; however, long-term studies are needed for further evaluation.

Risankizumab appears to be a promising new therapy based on phase 2 trial results. Improvements also were seen in dermatology life quality index scores, scalp and fingernail symptoms, and palmoplantar psoriasis.15 Of note, neutralizing antidrug antibodies were found in 3 patients during this study,15 which may present potential problems for long-term efficacy. However, preliminary data from 3 phase 3 trials—ultIMMa-1, ultIMMa-2, and IMMvent—are promising.17

CONCLUSION

Advances in the understanding of psoriasis have led to new targeted therapies. Ongoing clinical trials have shown encouraging results for treating physical and psychological symptoms of psoriasis. The findings of these trials support the idea that therapies targeting IL-23, specifically its p19 subunit, are effective against psoriasis while sparing IL-12. Long-term data from open-label extension studies would help guide clinical recommendations regarding the safety profiles of these agents and determine their long-term utility.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23; discussion, ii24, ii25.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Amin M, Darji K, No DJ, et al. Review of phase III trial data on IL-23 inhibitors tildrakizumab and guselkumab for psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1627-1632.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:273-279.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al; UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 investigators. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 study group, UNCOVER-2 study group, UNCOVER-3 study group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug Taltz [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; March 22, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm491872.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Mentor A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 15, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm541981.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:405-417.

- Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:418-431.

- Janssen announces U.S. FDA approval of Tremfya™ (guselkumab) for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Horsham, PA: Johnson & Johnson; July 13, 2017. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/janssen-announces-us-fda-approval-of-tremfya-guselkumab-for-the-treatment-of-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomized controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276-288.

- Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1551-1560.

- Risankizumab. AbbVie Inc website. https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/pipeline/risankizumab.html. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Risankizumab meets all co-primary and ranked secondary endpoints, achieving significantly greater efficacy versus standard biologic therapies in three pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies [news release]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; October 26, 2017. https://news.abbvie.com/news/risankizumab-meets-all-co-primary-and-ranked-secondary-endpoints-achieving-significantly-greater-efficacy-versus-standard-biologic-therapies-in-three-pivotal-phase-3-psoriasis-studies.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Glatt S, Helmer E, Haier B, et al. First-in-human randomized study of bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody and selective dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F, in mild psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:991-1001.

- Reich K, Ortonne JP, Gottlieb AB, et al. Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab‘ certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:180-190.

- Kimball AB, Luger T, Gottlieb A, et al. Impact of ixekizumab on psoriasis itch severity and other psoriasis symptoms: results from 3 phase III psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1156-1161.

- Dennehy EB, Zhang L, Amato D, et al. Ixekizumab is effective in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with significant nail involvement: results from UNCOVER 3. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:958-961.

- Gottlieb AB, Lacour JP, Korman N, et al. Treatment outcomes with ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who have not received prior biological therapies: an integrated analysis of two phase III randomized studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:679-685.

- Hueber W, Sands BE, Lewitsky S, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: unexpected results of a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2012;61:1693-1700.

- Papp K, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Safety and efficacy of brodalumab for psoriasis after 120 weeks of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1183-1190.

- Papp K, Menter A, Strober B, et al. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in subpopulations of patients with difficult-to-treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:436-439.

- SILIQ [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen, Inc; 2017.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23; discussion, ii24, ii25.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Amin M, Darji K, No DJ, et al. Review of phase III trial data on IL-23 inhibitors tildrakizumab and guselkumab for psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1627-1632.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:273-279.

- Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al; UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 investigators. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541-551.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al; UNCOVER-1 study group, UNCOVER-2 study group, UNCOVER-3 study group. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug Taltz [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; March 22, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm491872.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273-286.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Mentor A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- FDA approves new psoriasis drug [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; February 15, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm541981.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:405-417.

- Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:418-431.

- Janssen announces U.S. FDA approval of Tremfya™ (guselkumab) for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [news release]. Horsham, PA: Johnson & Johnson; July 13, 2017. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/janssen-announces-us-fda-approval-of-tremfya-guselkumab-for-the-treatment-of-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomized controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276-288.

- Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1551-1560.

- Risankizumab. AbbVie Inc website. https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/pipeline/risankizumab.html. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Risankizumab meets all co-primary and ranked secondary endpoints, achieving significantly greater efficacy versus standard biologic therapies in three pivotal phase 3 psoriasis studies [news release]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; October 26, 2017. https://news.abbvie.com/news/risankizumab-meets-all-co-primary-and-ranked-secondary-endpoints-achieving-significantly-greater-efficacy-versus-standard-biologic-therapies-in-three-pivotal-phase-3-psoriasis-studies.htm. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- Glatt S, Helmer E, Haier B, et al. First-in-human randomized study of bimekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody and selective dual inhibitor of IL-17A and IL-17F, in mild psoriasis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:991-1001.

- Reich K, Ortonne JP, Gottlieb AB, et al. Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab‘ certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:180-190.

- Kimball AB, Luger T, Gottlieb A, et al. Impact of ixekizumab on psoriasis itch severity and other psoriasis symptoms: results from 3 phase III psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1156-1161.