User login

Telestroke Neurologists May Have Longer Nonenhanced CT-to-CTA Times, Compared With Bedside Neurologists

LOS ANGELES—Among patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion, average time from nonenhanced CT (NECT) to CT angiogram (CTA) was significantly longer for patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers by telestroke neurologists, compared with the average time for patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers by bedside neurologists, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2018.

“Importantly, it may be that the delays at facilities covered by teleneurologists are due to radiology policies and procedures.… Telestroke neurologists should work with emergency department physicians and CT personnel to ensure that patients with suspected large-vessel occlusions have a CTA performed immediately after completion of the NECT,” said Andrew W. Asimos, MD, Medical Director of the Carolina Stroke Network of Carolinas Healthcare System in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“These data suggest that steps should be taken to ensure that NECT-to-CTA times receive the same attention as door-to-needle IV t-PA times in assessing overall telestroke neurologist process performance.”

The 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association stroke management guidelines strongly recommend that if endovascular therapy is considered, CTA should be included in the initial imaging evaluation. A prompt CTA can expedite the identification and transfer of patients with large-vessel occlusion for endovascular treatment, said Dr. Asimos.

Telestroke Neurologists vs Bedside Neurologists

Telestroke neurologists mainly focus on achieving quick door-to-needle IV t-PA times, rather than prompt CTA performance times, however. As a result, the researchers hypothesized that the NECT-to-CTA time interval for patients with large-vessel occlusion would be significantly longer at nonendovascular stroke centers using telestroke neurologists than at endovascular stroke centers with bedside neurologists.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers conducted a retrospective analysis. They compared the NECT–to-CTA time performance interval for consecutive patients with large-vessel occlusion who initially presented to any of 23 hospitals or freestanding emergency departments in a large healthcare system’s stroke network database and were candidates for endovascular treatment.

Over a seven-month period, researchers identified 71 cases of large-vessel occlusion in which patients initially presented to one of 21 nonendovascular stroke centers covered by telestroke neurologists and 62 cases in which patients presented to one of two endovascular stroke centers covered by bedside neurologists. After removing the outliers (ie, those NECT-to-CTA times greater than the 95th percentile for endovascular stroke center cases and greater than the 90th percentile for nonendovascular stroke center cases), researchers retained 64 cases from nonendovascular stroke centers and 59 cases from endovascular stroke centers.

In all, 48.4% of patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers and 45.8% of patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers were female.

NECT-to-CTA Times Were Longer at Nonendovascular Stroke Centers

Overall, patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers had significantly longer NECT-to-CTA performance times, compared with those examined at endovascular stroke centers. The mean NECT–to-CTA time interval was 29.9 minutes for telestroke neurologists, compared with 10 minutes for bedside neurologists. It is unknown, however, what protocol limitations contributed to these longer NECT to CTA performance times at non-endovascular stroke centers, said the researchers.

“Our focus now is to ensure that a sensitive large-vessel occlusion screen is performed on all patients prior to going to CT. For patients that screen positive for a possible large-vessel occlusion, we advocate that a CTA be performed immediately after the NECT,” said

—Erica Tricarico

LOS ANGELES—Among patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion, average time from nonenhanced CT (NECT) to CT angiogram (CTA) was significantly longer for patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers by telestroke neurologists, compared with the average time for patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers by bedside neurologists, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2018.

“Importantly, it may be that the delays at facilities covered by teleneurologists are due to radiology policies and procedures.… Telestroke neurologists should work with emergency department physicians and CT personnel to ensure that patients with suspected large-vessel occlusions have a CTA performed immediately after completion of the NECT,” said Andrew W. Asimos, MD, Medical Director of the Carolina Stroke Network of Carolinas Healthcare System in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“These data suggest that steps should be taken to ensure that NECT-to-CTA times receive the same attention as door-to-needle IV t-PA times in assessing overall telestroke neurologist process performance.”

The 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association stroke management guidelines strongly recommend that if endovascular therapy is considered, CTA should be included in the initial imaging evaluation. A prompt CTA can expedite the identification and transfer of patients with large-vessel occlusion for endovascular treatment, said Dr. Asimos.

Telestroke Neurologists vs Bedside Neurologists

Telestroke neurologists mainly focus on achieving quick door-to-needle IV t-PA times, rather than prompt CTA performance times, however. As a result, the researchers hypothesized that the NECT-to-CTA time interval for patients with large-vessel occlusion would be significantly longer at nonendovascular stroke centers using telestroke neurologists than at endovascular stroke centers with bedside neurologists.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers conducted a retrospective analysis. They compared the NECT–to-CTA time performance interval for consecutive patients with large-vessel occlusion who initially presented to any of 23 hospitals or freestanding emergency departments in a large healthcare system’s stroke network database and were candidates for endovascular treatment.

Over a seven-month period, researchers identified 71 cases of large-vessel occlusion in which patients initially presented to one of 21 nonendovascular stroke centers covered by telestroke neurologists and 62 cases in which patients presented to one of two endovascular stroke centers covered by bedside neurologists. After removing the outliers (ie, those NECT-to-CTA times greater than the 95th percentile for endovascular stroke center cases and greater than the 90th percentile for nonendovascular stroke center cases), researchers retained 64 cases from nonendovascular stroke centers and 59 cases from endovascular stroke centers.

In all, 48.4% of patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers and 45.8% of patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers were female.

NECT-to-CTA Times Were Longer at Nonendovascular Stroke Centers

Overall, patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers had significantly longer NECT-to-CTA performance times, compared with those examined at endovascular stroke centers. The mean NECT–to-CTA time interval was 29.9 minutes for telestroke neurologists, compared with 10 minutes for bedside neurologists. It is unknown, however, what protocol limitations contributed to these longer NECT to CTA performance times at non-endovascular stroke centers, said the researchers.

“Our focus now is to ensure that a sensitive large-vessel occlusion screen is performed on all patients prior to going to CT. For patients that screen positive for a possible large-vessel occlusion, we advocate that a CTA be performed immediately after the NECT,” said

—Erica Tricarico

LOS ANGELES—Among patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion, average time from nonenhanced CT (NECT) to CT angiogram (CTA) was significantly longer for patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers by telestroke neurologists, compared with the average time for patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers by bedside neurologists, according to research presented at the International Stroke Conference 2018.

“Importantly, it may be that the delays at facilities covered by teleneurologists are due to radiology policies and procedures.… Telestroke neurologists should work with emergency department physicians and CT personnel to ensure that patients with suspected large-vessel occlusions have a CTA performed immediately after completion of the NECT,” said Andrew W. Asimos, MD, Medical Director of the Carolina Stroke Network of Carolinas Healthcare System in Charlotte, North Carolina.

“These data suggest that steps should be taken to ensure that NECT-to-CTA times receive the same attention as door-to-needle IV t-PA times in assessing overall telestroke neurologist process performance.”

The 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association stroke management guidelines strongly recommend that if endovascular therapy is considered, CTA should be included in the initial imaging evaluation. A prompt CTA can expedite the identification and transfer of patients with large-vessel occlusion for endovascular treatment, said Dr. Asimos.

Telestroke Neurologists vs Bedside Neurologists

Telestroke neurologists mainly focus on achieving quick door-to-needle IV t-PA times, rather than prompt CTA performance times, however. As a result, the researchers hypothesized that the NECT-to-CTA time interval for patients with large-vessel occlusion would be significantly longer at nonendovascular stroke centers using telestroke neurologists than at endovascular stroke centers with bedside neurologists.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers conducted a retrospective analysis. They compared the NECT–to-CTA time performance interval for consecutive patients with large-vessel occlusion who initially presented to any of 23 hospitals or freestanding emergency departments in a large healthcare system’s stroke network database and were candidates for endovascular treatment.

Over a seven-month period, researchers identified 71 cases of large-vessel occlusion in which patients initially presented to one of 21 nonendovascular stroke centers covered by telestroke neurologists and 62 cases in which patients presented to one of two endovascular stroke centers covered by bedside neurologists. After removing the outliers (ie, those NECT-to-CTA times greater than the 95th percentile for endovascular stroke center cases and greater than the 90th percentile for nonendovascular stroke center cases), researchers retained 64 cases from nonendovascular stroke centers and 59 cases from endovascular stroke centers.

In all, 48.4% of patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers and 45.8% of patients evaluated at endovascular stroke centers were female.

NECT-to-CTA Times Were Longer at Nonendovascular Stroke Centers

Overall, patients evaluated at nonendovascular stroke centers had significantly longer NECT-to-CTA performance times, compared with those examined at endovascular stroke centers. The mean NECT–to-CTA time interval was 29.9 minutes for telestroke neurologists, compared with 10 minutes for bedside neurologists. It is unknown, however, what protocol limitations contributed to these longer NECT to CTA performance times at non-endovascular stroke centers, said the researchers.

“Our focus now is to ensure that a sensitive large-vessel occlusion screen is performed on all patients prior to going to CT. For patients that screen positive for a possible large-vessel occlusion, we advocate that a CTA be performed immediately after the NECT,” said

—Erica Tricarico

Trauma surgeon shares story of involuntary commitment, redemption

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?

“A few months after I left, I became even more depressed and suicidal. I didn’t go back, and I really hope I’ll never have to be in a hospital again.” Instead,. “They changed my perspective.”

Dr. Weinstein also questions if he should have agreed to ECT. “I was better when I left the hospital, but the treatment itself was crude, and I still wonder if it affects my memory now.”

I wanted to know what psychiatrists might learn from his experiences with involuntary care. Weinstein hesitated. “It wasn’t the best experience, and I felt there had to be a better way, but I know everyone was trying to help me, and I want my overall message to be one of hope. I don’t want to complain, because I’ve ended up in a much better place, I’m back at work, enjoying my family, and I feel joy now.”

For psychiatrists, this is the best outcome from a story such as Dr. Weinstein’s. He’s much better, in a scenario where he could have just as easily have died, and he wasn’t traumatized by his care. However, he avoided returning to inpatient care at a precarious time, and he’s left asking if there weren’t a gentler way this could have transpired. These questions are easier to look at from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback than they are to look at from the perspective of a treatment team dealing with a very sick and combative patient. Still, I hope we all continue to question patients about their experiences and ask if there might be better ways.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?

“A few months after I left, I became even more depressed and suicidal. I didn’t go back, and I really hope I’ll never have to be in a hospital again.” Instead,. “They changed my perspective.”

Dr. Weinstein also questions if he should have agreed to ECT. “I was better when I left the hospital, but the treatment itself was crude, and I still wonder if it affects my memory now.”

I wanted to know what psychiatrists might learn from his experiences with involuntary care. Weinstein hesitated. “It wasn’t the best experience, and I felt there had to be a better way, but I know everyone was trying to help me, and I want my overall message to be one of hope. I don’t want to complain, because I’ve ended up in a much better place, I’m back at work, enjoying my family, and I feel joy now.”

For psychiatrists, this is the best outcome from a story such as Dr. Weinstein’s. He’s much better, in a scenario where he could have just as easily have died, and he wasn’t traumatized by his care. However, he avoided returning to inpatient care at a precarious time, and he’s left asking if there weren’t a gentler way this could have transpired. These questions are easier to look at from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback than they are to look at from the perspective of a treatment team dealing with a very sick and combative patient. Still, I hope we all continue to question patients about their experiences and ask if there might be better ways.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?

“A few months after I left, I became even more depressed and suicidal. I didn’t go back, and I really hope I’ll never have to be in a hospital again.” Instead,. “They changed my perspective.”

Dr. Weinstein also questions if he should have agreed to ECT. “I was better when I left the hospital, but the treatment itself was crude, and I still wonder if it affects my memory now.”

I wanted to know what psychiatrists might learn from his experiences with involuntary care. Weinstein hesitated. “It wasn’t the best experience, and I felt there had to be a better way, but I know everyone was trying to help me, and I want my overall message to be one of hope. I don’t want to complain, because I’ve ended up in a much better place, I’m back at work, enjoying my family, and I feel joy now.”

For psychiatrists, this is the best outcome from a story such as Dr. Weinstein’s. He’s much better, in a scenario where he could have just as easily have died, and he wasn’t traumatized by his care. However, he avoided returning to inpatient care at a precarious time, and he’s left asking if there weren’t a gentler way this could have transpired. These questions are easier to look at from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback than they are to look at from the perspective of a treatment team dealing with a very sick and combative patient. Still, I hope we all continue to question patients about their experiences and ask if there might be better ways.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Counsel children and young adults on skin cancer prevention

(USPSTF). The recommendations, published online March 20 in JAMA, advise clinicians to counsel young adults, children, and parents of young children who are aged 6 months to 24 years and have fair skin types about skin cancer prevention. Counseling for individuals aged 24 years and older should be based on a clinician’s assessment of patient risk.

The recommendations target asymptomatic individuals with no history of skin cancer who might be likely to sunburn easily, wrote David C. Grossman, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, the corresponding author of the USPSTF recommendation statement, and his associates.

The task force found adequate (grade B) evidence to support behavioral counseling for children and young adults aged 6 months to 24 years with no notable risk of harm from this intervention. The task force gave a grade C recommendation for routine skin cancer counseling for adults older than 24 years, citing a small net benefit. In addition, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence (I statement) to evaluate the risks versus benefits of counseling adults about skin self-examination as a way to reduce skin cancer risk.

In the evidence report, lead author Nora B. Henrikson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues addressed five topics: the effects of skin cancer prevention counseling on short- and long-term outcomes, the effects of primary care counseling interventions on skin cancer prevention behavior, the association between skin self-examination and skin cancer outcomes, the potential harms of counseling interventions, and the potential harms of skin self-examinations.

“Small to moderate effects of behavioral interventions on increased sun protection behaviors were observed in studies of all age groups, though overall, adult trial results were mixed and fewer studies demonstrated an intervention effect,” the researchers said.

The evidence review was limited by several factors including a focus on primary care intervention only and an exclusion of skin cancer survivors, the researchers noted. Although evidence does not show that sunburns are less frequent as a result of interventions, behavioral intervention can improve sun protection behavior, they said. However, intervention in adults “may lead to increased skin procedures without detecting additional atypical nevi or skin cancers,” they noted.

The recommendations are consistent with the draft recommendations published in 2017 and expand the recommendations from 2012 that advised counseling for individuals aged 10-24 years.

The research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Grossman DC et al. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1134-42.

The term “fair skin types” as used in the USPSTF recommendations is not necessarily helpful in identifying individuals who could benefit from skin cancer prevention counseling, June K. Robinson, MD, and Nina G. Jablonski, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;319[11]:1101-2). Hair and eye color do not predict sun sensitivity, and in general, men and individuals with darker skin don’t think they are at risk for skin cancer even when they sunburn, they noted.

“The terminology that is used by investigators and then incorporated into the USPSTF evidence base needs to evolve to include all persons at risk, without disenfranchising portions of the diverse U.S. population,” they said. In addition to skin type, physicians need to evaluate a patient’s melanoma risk based on lifestyle factors, such as time spent outdoors, photosensitizing medications, and sun protection habits, they added, but primary care clinicians often lack the time to offer personalized sun protection counseling.

“It would be better to encourage people to check the UV Index daily – or consider a mobile application that automatically provides it – and plan outdoor activities, especially physical activities, to be sun safe,” they said. In addition, individuals may be more likely to manage skin cancer risk with a mix of supportive messages via social media to augment in-person counseling from a clinician; furthermore, “normative approval by friends and peers can have a strong reinforcing influence on sun safety behaviors, particularly among youth, who are at a vulnerable age for acquiring melanoma risk,” they emphasized.

Dr. Robinson is a research professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and is the editor of JAMA Dermatology. She is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Jablonski is a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, University Park. Dr. Robinson had no financial conflicts to disclose; Dr. Jablonski has served on the scientific advisory board of the L’Oreal Group.

The term “fair skin types” as used in the USPSTF recommendations is not necessarily helpful in identifying individuals who could benefit from skin cancer prevention counseling, June K. Robinson, MD, and Nina G. Jablonski, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;319[11]:1101-2). Hair and eye color do not predict sun sensitivity, and in general, men and individuals with darker skin don’t think they are at risk for skin cancer even when they sunburn, they noted.

“The terminology that is used by investigators and then incorporated into the USPSTF evidence base needs to evolve to include all persons at risk, without disenfranchising portions of the diverse U.S. population,” they said. In addition to skin type, physicians need to evaluate a patient’s melanoma risk based on lifestyle factors, such as time spent outdoors, photosensitizing medications, and sun protection habits, they added, but primary care clinicians often lack the time to offer personalized sun protection counseling.

“It would be better to encourage people to check the UV Index daily – or consider a mobile application that automatically provides it – and plan outdoor activities, especially physical activities, to be sun safe,” they said. In addition, individuals may be more likely to manage skin cancer risk with a mix of supportive messages via social media to augment in-person counseling from a clinician; furthermore, “normative approval by friends and peers can have a strong reinforcing influence on sun safety behaviors, particularly among youth, who are at a vulnerable age for acquiring melanoma risk,” they emphasized.

Dr. Robinson is a research professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and is the editor of JAMA Dermatology. She is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Jablonski is a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, University Park. Dr. Robinson had no financial conflicts to disclose; Dr. Jablonski has served on the scientific advisory board of the L’Oreal Group.

The term “fair skin types” as used in the USPSTF recommendations is not necessarily helpful in identifying individuals who could benefit from skin cancer prevention counseling, June K. Robinson, MD, and Nina G. Jablonski, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;319[11]:1101-2). Hair and eye color do not predict sun sensitivity, and in general, men and individuals with darker skin don’t think they are at risk for skin cancer even when they sunburn, they noted.

“The terminology that is used by investigators and then incorporated into the USPSTF evidence base needs to evolve to include all persons at risk, without disenfranchising portions of the diverse U.S. population,” they said. In addition to skin type, physicians need to evaluate a patient’s melanoma risk based on lifestyle factors, such as time spent outdoors, photosensitizing medications, and sun protection habits, they added, but primary care clinicians often lack the time to offer personalized sun protection counseling.

“It would be better to encourage people to check the UV Index daily – or consider a mobile application that automatically provides it – and plan outdoor activities, especially physical activities, to be sun safe,” they said. In addition, individuals may be more likely to manage skin cancer risk with a mix of supportive messages via social media to augment in-person counseling from a clinician; furthermore, “normative approval by friends and peers can have a strong reinforcing influence on sun safety behaviors, particularly among youth, who are at a vulnerable age for acquiring melanoma risk,” they emphasized.

Dr. Robinson is a research professor of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and is the editor of JAMA Dermatology. She is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Jablonski is a professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University, University Park. Dr. Robinson had no financial conflicts to disclose; Dr. Jablonski has served on the scientific advisory board of the L’Oreal Group.

(USPSTF). The recommendations, published online March 20 in JAMA, advise clinicians to counsel young adults, children, and parents of young children who are aged 6 months to 24 years and have fair skin types about skin cancer prevention. Counseling for individuals aged 24 years and older should be based on a clinician’s assessment of patient risk.

The recommendations target asymptomatic individuals with no history of skin cancer who might be likely to sunburn easily, wrote David C. Grossman, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, the corresponding author of the USPSTF recommendation statement, and his associates.

The task force found adequate (grade B) evidence to support behavioral counseling for children and young adults aged 6 months to 24 years with no notable risk of harm from this intervention. The task force gave a grade C recommendation for routine skin cancer counseling for adults older than 24 years, citing a small net benefit. In addition, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence (I statement) to evaluate the risks versus benefits of counseling adults about skin self-examination as a way to reduce skin cancer risk.

In the evidence report, lead author Nora B. Henrikson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues addressed five topics: the effects of skin cancer prevention counseling on short- and long-term outcomes, the effects of primary care counseling interventions on skin cancer prevention behavior, the association between skin self-examination and skin cancer outcomes, the potential harms of counseling interventions, and the potential harms of skin self-examinations.

“Small to moderate effects of behavioral interventions on increased sun protection behaviors were observed in studies of all age groups, though overall, adult trial results were mixed and fewer studies demonstrated an intervention effect,” the researchers said.

The evidence review was limited by several factors including a focus on primary care intervention only and an exclusion of skin cancer survivors, the researchers noted. Although evidence does not show that sunburns are less frequent as a result of interventions, behavioral intervention can improve sun protection behavior, they said. However, intervention in adults “may lead to increased skin procedures without detecting additional atypical nevi or skin cancers,” they noted.

The recommendations are consistent with the draft recommendations published in 2017 and expand the recommendations from 2012 that advised counseling for individuals aged 10-24 years.

The research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Grossman DC et al. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1134-42.

(USPSTF). The recommendations, published online March 20 in JAMA, advise clinicians to counsel young adults, children, and parents of young children who are aged 6 months to 24 years and have fair skin types about skin cancer prevention. Counseling for individuals aged 24 years and older should be based on a clinician’s assessment of patient risk.

The recommendations target asymptomatic individuals with no history of skin cancer who might be likely to sunburn easily, wrote David C. Grossman, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, the corresponding author of the USPSTF recommendation statement, and his associates.

The task force found adequate (grade B) evidence to support behavioral counseling for children and young adults aged 6 months to 24 years with no notable risk of harm from this intervention. The task force gave a grade C recommendation for routine skin cancer counseling for adults older than 24 years, citing a small net benefit. In addition, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence (I statement) to evaluate the risks versus benefits of counseling adults about skin self-examination as a way to reduce skin cancer risk.

In the evidence report, lead author Nora B. Henrikson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, and her colleagues addressed five topics: the effects of skin cancer prevention counseling on short- and long-term outcomes, the effects of primary care counseling interventions on skin cancer prevention behavior, the association between skin self-examination and skin cancer outcomes, the potential harms of counseling interventions, and the potential harms of skin self-examinations.

“Small to moderate effects of behavioral interventions on increased sun protection behaviors were observed in studies of all age groups, though overall, adult trial results were mixed and fewer studies demonstrated an intervention effect,” the researchers said.

The evidence review was limited by several factors including a focus on primary care intervention only and an exclusion of skin cancer survivors, the researchers noted. Although evidence does not show that sunburns are less frequent as a result of interventions, behavioral intervention can improve sun protection behavior, they said. However, intervention in adults “may lead to increased skin procedures without detecting additional atypical nevi or skin cancers,” they noted.

The recommendations are consistent with the draft recommendations published in 2017 and expand the recommendations from 2012 that advised counseling for individuals aged 10-24 years.

The research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Grossman DC et al. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1134-42.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Moderate evidence supports behavioral counseling to help reduce skin cancer risk in children and young adults.

Major finding: One trial that included 1,356 adults showed no difference in the number of skin cancers and atypical nevi between a control group and patients who received counseling to encourage skin examination.

Study details: The evidence review included 21 trials in 27 publications for a total of 20,561 individuals.

Disclosures: The review was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Source: Grossman DC et al. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1134-42.

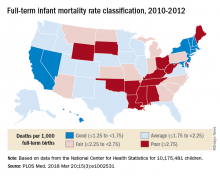

Full-term infant mortality: United States versus Europe

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

according to Neha Bairoliya, PhD, and Günther Fink, PhD.

The United States had an FTIMR of 2.19 per 1,000 full-term live births for that 3-year period, compared with a median of 1.11 for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, said Dr. Bairoliya of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Cambridge, Mass., and Dr. Fink of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland.

A classification system for individual states that rated FTIMR scores from poor (greater than or equal to 2.75) to excellent (greater than 1.25) put Connecticut, with a U.S.–low rate of 1.29 per 1,000 births, in the good (greater than or equal to1.25 to 1.75) category, so no state managed to join the excellent group of European countries, whose highest rate was 1.24, they reported in PLOS Medicine.

Missouri’s FTIMR of 3.77 per 1,000 was the highest among the 50 states. Along with Missouri, 12 other states were classified as poor, while 11 were considered fair (less than or equal to 2.25 to less than 2.75), 16 were average (less than or equal to 1.25 to less than 1.75), and 10 states earned a classification of good, the investigators said.

They used National Center for Health Statistics data for 7,431 deaths among 10,175,481 children born full term – defined as 37-42 weeks’ gestation – between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2012. Data on European births came from the Euro-Peristat database.

Data for preterm births put the United States in a somewhat better light: For births from 32 to 36 weeks, mortality rates were 8.24 per 1,000 in the United States and 8.25 for the six European countries; for births at 24-27 weeks, the rates were 199 in the United States and 213 for the Euro six, Dr. Bairoliya and Dr. Fink said.

The investigators did not receive any specific funding for the study, and they said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bairoliya N, Fink G. PLOS Med. 2018 Mar 20;15(3):e1002531.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Laser tattoo removal clinic closures: Are patients getting scammed?

A patient came into my office recently and informed me that a well-known laser tattoo removal clinic in Los Angeles that she had gone to for years had suddenly shut down. All locations closed. No one answered the phone. No information about the remainder of the money in the package she bought. After researching online, she found that the Better Business Bureau did not yet have much information but doubted she would get her money back. This particular patient had not gone to the clinic in more than a year but had a residual tattoo and had looked into returning for more treatments and using the remainder of her package. She was one of the lucky ones. Other online discussion groups had entries from numerous patients who paid for packages (some costing thousands of dollars) for multiple laser treatments. Some had paid recently and had not yet received a single treatment and were left with no information about their options or where their money had gone.

It turns out in Southern California and Texas. No notification was given to the patients in advance. Nor was any notification given to some of the staff members, who complained online that they suddenly lost their jobs. Ironically, the same clinics had posted a letter online several years ago honoring discounted first treatments and packages for patients of a different laser tattoo clinic that had suddenly shut down.

So how often is this happening? Are all these clinics owned by the same people? And what can our specialty do to protect patients from being scammed and, for that matter, receiving treatment from professionals who may not be properly trained or experienced to provide that treatment?

In a world in which insurance reimbursements keep getting cut, more and more medical professionals – physicians and nonphysicians alike – are looking to fee-for-service procedures and practice models for increasing income. Sometimes, this may involve physicians delegating procedures to nonphysicians. Franchised clinics open up with a physician to “oversee” the clinic, while extenders often perform the procedures (many times without the physician present). Physicians who are neither trained nor specialized to do certain cosmetic procedures start to perform them. Patients get used to receiving treatments from nonphysicians or from physicians who are not specialized to perform cosmetic procedures, and then may devalue the procedure, feeling it’s unnecessary for a physician or a specialized physician to perform it.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

A patient came into my office recently and informed me that a well-known laser tattoo removal clinic in Los Angeles that she had gone to for years had suddenly shut down. All locations closed. No one answered the phone. No information about the remainder of the money in the package she bought. After researching online, she found that the Better Business Bureau did not yet have much information but doubted she would get her money back. This particular patient had not gone to the clinic in more than a year but had a residual tattoo and had looked into returning for more treatments and using the remainder of her package. She was one of the lucky ones. Other online discussion groups had entries from numerous patients who paid for packages (some costing thousands of dollars) for multiple laser treatments. Some had paid recently and had not yet received a single treatment and were left with no information about their options or where their money had gone.

It turns out in Southern California and Texas. No notification was given to the patients in advance. Nor was any notification given to some of the staff members, who complained online that they suddenly lost their jobs. Ironically, the same clinics had posted a letter online several years ago honoring discounted first treatments and packages for patients of a different laser tattoo clinic that had suddenly shut down.

So how often is this happening? Are all these clinics owned by the same people? And what can our specialty do to protect patients from being scammed and, for that matter, receiving treatment from professionals who may not be properly trained or experienced to provide that treatment?

In a world in which insurance reimbursements keep getting cut, more and more medical professionals – physicians and nonphysicians alike – are looking to fee-for-service procedures and practice models for increasing income. Sometimes, this may involve physicians delegating procedures to nonphysicians. Franchised clinics open up with a physician to “oversee” the clinic, while extenders often perform the procedures (many times without the physician present). Physicians who are neither trained nor specialized to do certain cosmetic procedures start to perform them. Patients get used to receiving treatments from nonphysicians or from physicians who are not specialized to perform cosmetic procedures, and then may devalue the procedure, feeling it’s unnecessary for a physician or a specialized physician to perform it.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

A patient came into my office recently and informed me that a well-known laser tattoo removal clinic in Los Angeles that she had gone to for years had suddenly shut down. All locations closed. No one answered the phone. No information about the remainder of the money in the package she bought. After researching online, she found that the Better Business Bureau did not yet have much information but doubted she would get her money back. This particular patient had not gone to the clinic in more than a year but had a residual tattoo and had looked into returning for more treatments and using the remainder of her package. She was one of the lucky ones. Other online discussion groups had entries from numerous patients who paid for packages (some costing thousands of dollars) for multiple laser treatments. Some had paid recently and had not yet received a single treatment and were left with no information about their options or where their money had gone.

It turns out in Southern California and Texas. No notification was given to the patients in advance. Nor was any notification given to some of the staff members, who complained online that they suddenly lost their jobs. Ironically, the same clinics had posted a letter online several years ago honoring discounted first treatments and packages for patients of a different laser tattoo clinic that had suddenly shut down.

So how often is this happening? Are all these clinics owned by the same people? And what can our specialty do to protect patients from being scammed and, for that matter, receiving treatment from professionals who may not be properly trained or experienced to provide that treatment?

In a world in which insurance reimbursements keep getting cut, more and more medical professionals – physicians and nonphysicians alike – are looking to fee-for-service procedures and practice models for increasing income. Sometimes, this may involve physicians delegating procedures to nonphysicians. Franchised clinics open up with a physician to “oversee” the clinic, while extenders often perform the procedures (many times without the physician present). Physicians who are neither trained nor specialized to do certain cosmetic procedures start to perform them. Patients get used to receiving treatments from nonphysicians or from physicians who are not specialized to perform cosmetic procedures, and then may devalue the procedure, feeling it’s unnecessary for a physician or a specialized physician to perform it.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

SGLT2 inhibitors cut cardiovascular outcomes regardless of region

ORLANDO – Cardiovascular outcomes were significantly more favorable with sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, according to data from more than 400,000 type 2 diabetes patients in the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and North America.

Data on cardiovascular outcomes from diabetes treatments in patients outside the United States and Europe are limited, said Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, of Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City.

In fact, most patients with type 2 diabetes reside in the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, he said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Kosiborod was involved in a previous large pharmaco-epidemiologic study known as the Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (CVD-REAL), that showed SGLT2 inhibitor effects in a broad population of type 2 diabetes patients, but that study included only patients from Europe and North America, and focused on just two outcomes: all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure.

The study population included adults aged 18 years and older diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; a total of 235,064 treated with SGLT2 inhibitors and 235,064 treated with other GLDs. The participants were selected from national databases in Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded from the study.

Outcomes comparing SGLT2 inhibitors and other GLDs included all-cause death, all-cause death or hospitalization for heart failure, hospitalization for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups. Exposure time for patients in the SGLT2-inhibitor group was highest by far for dapagliflozin (75%), followed by empagliflozin, ipragliflozin, canagliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin at 9%, 8%, 4%, 3%, and 1%, respectively. (Ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin are approved only in Japan.)

The researchers identified 5,216 deaths from any cause. Overall, treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with significantly lower risks of death (hazard ratio, 0.51), hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.64), death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 0.81), and stroke (HR, 0.68).

The findings remained consistent across countries and patient subgroups, and in patients with and without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Kosiborod noted.

The results were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study and incomplete mortality data, Dr. Kosiborod said. However, the results suggest that the SGLT2 inhibitors’ impacts on cardiovascular outcomes persist across categories of ethnicity, geography, and cardiovascular disease.

AstraZeneca supported the study. Dr. Kosiborod disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Glytec, and ZS Pharma. The findings were simultaneously published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.009).

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 2018.

ORLANDO – Cardiovascular outcomes were significantly more favorable with sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, according to data from more than 400,000 type 2 diabetes patients in the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and North America.

Data on cardiovascular outcomes from diabetes treatments in patients outside the United States and Europe are limited, said Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, of Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City.

In fact, most patients with type 2 diabetes reside in the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, he said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Kosiborod was involved in a previous large pharmaco-epidemiologic study known as the Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (CVD-REAL), that showed SGLT2 inhibitor effects in a broad population of type 2 diabetes patients, but that study included only patients from Europe and North America, and focused on just two outcomes: all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure.

The study population included adults aged 18 years and older diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; a total of 235,064 treated with SGLT2 inhibitors and 235,064 treated with other GLDs. The participants were selected from national databases in Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded from the study.

Outcomes comparing SGLT2 inhibitors and other GLDs included all-cause death, all-cause death or hospitalization for heart failure, hospitalization for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups. Exposure time for patients in the SGLT2-inhibitor group was highest by far for dapagliflozin (75%), followed by empagliflozin, ipragliflozin, canagliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin at 9%, 8%, 4%, 3%, and 1%, respectively. (Ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin are approved only in Japan.)

The researchers identified 5,216 deaths from any cause. Overall, treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with significantly lower risks of death (hazard ratio, 0.51), hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.64), death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 0.81), and stroke (HR, 0.68).

The findings remained consistent across countries and patient subgroups, and in patients with and without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Kosiborod noted.

The results were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study and incomplete mortality data, Dr. Kosiborod said. However, the results suggest that the SGLT2 inhibitors’ impacts on cardiovascular outcomes persist across categories of ethnicity, geography, and cardiovascular disease.

AstraZeneca supported the study. Dr. Kosiborod disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Glytec, and ZS Pharma. The findings were simultaneously published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.009).

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 2018.

ORLANDO – Cardiovascular outcomes were significantly more favorable with sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors compared with other glucose-lowering drugs, according to data from more than 400,000 type 2 diabetes patients in the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and North America.

Data on cardiovascular outcomes from diabetes treatments in patients outside the United States and Europe are limited, said Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, of Saint Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City.

In fact, most patients with type 2 diabetes reside in the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, he said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Kosiborod was involved in a previous large pharmaco-epidemiologic study known as the Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (CVD-REAL), that showed SGLT2 inhibitor effects in a broad population of type 2 diabetes patients, but that study included only patients from Europe and North America, and focused on just two outcomes: all-cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure.

The study population included adults aged 18 years and older diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; a total of 235,064 treated with SGLT2 inhibitors and 235,064 treated with other GLDs. The participants were selected from national databases in Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded from the study.

Outcomes comparing SGLT2 inhibitors and other GLDs included all-cause death, all-cause death or hospitalization for heart failure, hospitalization for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups. Exposure time for patients in the SGLT2-inhibitor group was highest by far for dapagliflozin (75%), followed by empagliflozin, ipragliflozin, canagliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin at 9%, 8%, 4%, 3%, and 1%, respectively. (Ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, and luseogliflozin are approved only in Japan.)

The researchers identified 5,216 deaths from any cause. Overall, treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor was associated with significantly lower risks of death (hazard ratio, 0.51), hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.64), death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 0.81), and stroke (HR, 0.68).

The findings remained consistent across countries and patient subgroups, and in patients with and without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Kosiborod noted.

The results were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study and incomplete mortality data, Dr. Kosiborod said. However, the results suggest that the SGLT2 inhibitors’ impacts on cardiovascular outcomes persist across categories of ethnicity, geography, and cardiovascular disease.

AstraZeneca supported the study. Dr. Kosiborod disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Glytec, and ZS Pharma. The findings were simultaneously published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.009).

SOURCE: Kosiborod M. ACC 2018.

REPORTING FROM ACC 18

Key clinical point: SGLT2 inhibitor use was linked to a lower risk of all-cause death, hospitalization for heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke in a large, multinational study of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: All-cause mortality was significantly lower in patients treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor compared with other glucose lowering drugs (HR 0.51).

Study details: The data come from more than 400,000 adults with type 2 diabetes via databases in the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and North America.

Disclosures: AstraZeneca supported the study. Dr. Kosiborod disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Glytec, and ZS Pharma.

Source: Kosiborod M. ACC 2018.

Congress tackles the opioid epidemic. But how much will it help?

The nation’s opioid epidemic has been called today’s version of the 1980s AIDS crisis.

In a New Hampshire speech on March 19, President Donald Trump pushed for a tougher federal response, emphasizing a tough-on-crime approach for drug dealers and more funding for treatment. And Congress is upping the ante, via a series of hearings – including one scheduled to last March 21-22 – to study legislation that might tackle the unyielding scourge, which has cost an estimated $1 trillion in premature deaths, health care costs, and lost wages since 2001.

Dr. Leana Wen, an emergency physician by training and the health commissioner for hard-hit Baltimore, said Capitol Hill has to help communities at risk of becoming overwhelmed.

“We haven’t seen the peak of the epidemic. We are seeing the numbers climb year after year,” she said.

Provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that almost 45,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in the 12-month period ending July 2017, up from about 38,000 in the previous cycle. (Those data are likely to change, since many death certificates have not yet been reported to the CDC.)

“It’s not going to get any better unless we take dramatic action,” Dr. Wen said.

And the time for most meaningful change could be dwindling. Advocates say what they need most is money, which would most likely come through the government spending bill that’s due March 23. But they aren’t holding their breath.

Show me the money

The federal budget deal, which was signed into law in early February, promised $6 billion over 2 years for initiatives to fight opioid abuse. Congress is still figuring out how to divvy up those funds. The blueprint is expected to be included in the spending bill this week.

In February, a bipartisan group of senators introduced a bill that would add another $1 billion in funding to support expanded treatment and also limit clinicians to prescribing no more than 3 days’ worth of opioids at a time.

That legislation is likely to have wide support in the Senate, but its path through the House is less certain.

This cash infusion is still not going to be enough, predicted Daniel Raymond, policy director for the Harm Reduction Coalition, a national organization that works on overdose prevention.

“It’s not clear whether there’s a real appetite to go as far as we need to see Congress go,” he said. “To have a fighting chance, we need a long-term commitment of at least $10 billion per year.” Academic experts said that assessment sounded on target.

The figure is more than 3 times what’s allocated in the budget and 10 times what even the new Senate bill would provide, and far beyond the spending levels put forth by any previous packages to fight the opioid epidemic.

The difficulty in getting funding – and a key reason why the bipartisan Senate bill might stall in the House – in part goes to the heart of Republicans’ philosophy about budgeting.

The GOP, which controls both chambers of Congress, has “always been very focused on pay-fors,” said a Republican aide to the House Energy and Commerce Committee, explaining that new funding is generally expected to be accompanied by cuts in current expenditures so that overall government spending doesn’t rise. And that could limit how much money lawmakers are ultimately willing to commit to fight opioid abuse.

Some observers worry this notion is pound-foolish.

“We have an enormous set of costs ahead of us if we don’t invest now,” said Dr. Traci Green, an associate professor of emergency medicine and community health science at Boston University, who has extensively researched the epidemic.

Ahead in Congress

Meanwhile, the House could take up its version of a separate Senate-passed proposal designed to, in certain cases, make more prominent any opioid history in a patient’s medical record. The idea is to prevent doctors from prescribing opioids to at-risk patients.

In addition, the House’s Energy and Commerce Committee in late February held a hearing focused on “enforcement” – discussing, for instance, giving the federal Drug Enforcement Administration more power in drug trafficking, and whether to treat fentanyl, a particularly potent synthetic opioid, as a controlled substance. The hearings March 21-22 will tackle a slew of public health–oriented bills, such as making sure overdose patients in the emergency room get appropriate medication and treatment upon discharge, or expanding access to buprenorphine, which is used to treat addiction.

And the House Ways and Means Committee, which has jurisdiction over Medicare – the federal insurance plan for seniors and disabled people – is working to develop strategies that limit access to opioids and make treatment more available.