User login

Case Study - Foot and Hand Tapping

Nikesh Ardeshna, MD, MS, FAES

Case

A 73-year-old right-handed male presents with a history of mild depression (since his retirement about 2 years prior to the office visit) and benign prostatic hypertrophy. For about 8 months, the patient had episodes of right hand tapping, or right foot tapping accompanied by staring, and sometimes by what was described as a pronounced swallow/gulp. The total duration of these symptoms was less than one minute. The patient denied having any falls, major illness, or head trauma prior to the onset of symptoms. On initial evaluation the patient was diagnosed with anxiety. He elected not to start any medication.

The symptoms continued, and the patient was not aware that they were occurring. For example, one episode occurred at the dinner table with guests. The patient tapped on the adjacent dinner plate, and the guests thought he was playing a joke. The patient’s wife took him for a re-evaluation, and an episode occurred in the physician’s office.

The physician ordered a routine electroencephalogram (EEG). The EEG showed frequent left frontal temporal sharp and slow waves. No seizures were recorded. The patient was referred to an epileptologist. He was started on lacosamide, with a slowly escalating dose. Since being on a therapeutic dose the patient has not experienced any events, as reported by others.

Question 1: What is the patient’s diagnosis?

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Tics

- Partial epilepsy

- Unknown

Answer: d) Partial Epilepsy

Partial epilepsy (recurrent partial seizures) can manifest with a combination of tapping, chewing, staring, and blinking, but it is not limited to these symptoms. These abnormal, unintended movements are automatisms.

Question 2: Which adverse events may take greater precedence in the elderly and must be considered when choosing which anti-seizure medication to prescribe?

- Drowsiness

- Cognitive slowing/slow processing

- Unsteady gait

- Double vision

- All of the above

Answer: e) All of the above

Different anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) can have different adverse events. But, many potential adverse events are common to all ASDs although to differing extents, including but not limited to sleepiness/drowsiness and cognitive slowing/memory loss. Elderly patients are more prone to falls, and may have preexisting memory or cognitive issues. Adverse events should be minimized to the greatest extent possible in the elderly. Physicians should remember that each individual/case is unique.

Question 3: Which of the following demonstrates the correct match of a cause (etiology) of epilepsy and when seizures may begin due to that cause:

- Stroke – 6 months

- Brain tumor – 3 months

- Dementia – 1 year

- Idiopathic (unknown etiology) – childhood years

- None of the above

Answer: e) None of the above

The above is only a partial list of causes of epilepsy. For symptomatic epilepsy – epilepsy due to a stroke, brain tumor, or dementia, there is not a specific timeframe in which/by which the seizures have to begin. Also, a significant number of cases of epilepsy are of unknown cause (idiopathic), and in these situations seizures can begin at any age, as is the case above.

Nikesh Ardeshna, MD, MS, FAES

Case

A 73-year-old right-handed male presents with a history of mild depression (since his retirement about 2 years prior to the office visit) and benign prostatic hypertrophy. For about 8 months, the patient had episodes of right hand tapping, or right foot tapping accompanied by staring, and sometimes by what was described as a pronounced swallow/gulp. The total duration of these symptoms was less than one minute. The patient denied having any falls, major illness, or head trauma prior to the onset of symptoms. On initial evaluation the patient was diagnosed with anxiety. He elected not to start any medication.

The symptoms continued, and the patient was not aware that they were occurring. For example, one episode occurred at the dinner table with guests. The patient tapped on the adjacent dinner plate, and the guests thought he was playing a joke. The patient’s wife took him for a re-evaluation, and an episode occurred in the physician’s office.

The physician ordered a routine electroencephalogram (EEG). The EEG showed frequent left frontal temporal sharp and slow waves. No seizures were recorded. The patient was referred to an epileptologist. He was started on lacosamide, with a slowly escalating dose. Since being on a therapeutic dose the patient has not experienced any events, as reported by others.

Question 1: What is the patient’s diagnosis?

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Tics

- Partial epilepsy

- Unknown

Answer: d) Partial Epilepsy

Partial epilepsy (recurrent partial seizures) can manifest with a combination of tapping, chewing, staring, and blinking, but it is not limited to these symptoms. These abnormal, unintended movements are automatisms.

Question 2: Which adverse events may take greater precedence in the elderly and must be considered when choosing which anti-seizure medication to prescribe?

- Drowsiness

- Cognitive slowing/slow processing

- Unsteady gait

- Double vision

- All of the above

Answer: e) All of the above

Different anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) can have different adverse events. But, many potential adverse events are common to all ASDs although to differing extents, including but not limited to sleepiness/drowsiness and cognitive slowing/memory loss. Elderly patients are more prone to falls, and may have preexisting memory or cognitive issues. Adverse events should be minimized to the greatest extent possible in the elderly. Physicians should remember that each individual/case is unique.

Question 3: Which of the following demonstrates the correct match of a cause (etiology) of epilepsy and when seizures may begin due to that cause:

- Stroke – 6 months

- Brain tumor – 3 months

- Dementia – 1 year

- Idiopathic (unknown etiology) – childhood years

- None of the above

Answer: e) None of the above

The above is only a partial list of causes of epilepsy. For symptomatic epilepsy – epilepsy due to a stroke, brain tumor, or dementia, there is not a specific timeframe in which/by which the seizures have to begin. Also, a significant number of cases of epilepsy are of unknown cause (idiopathic), and in these situations seizures can begin at any age, as is the case above.

Nikesh Ardeshna, MD, MS, FAES

Case

A 73-year-old right-handed male presents with a history of mild depression (since his retirement about 2 years prior to the office visit) and benign prostatic hypertrophy. For about 8 months, the patient had episodes of right hand tapping, or right foot tapping accompanied by staring, and sometimes by what was described as a pronounced swallow/gulp. The total duration of these symptoms was less than one minute. The patient denied having any falls, major illness, or head trauma prior to the onset of symptoms. On initial evaluation the patient was diagnosed with anxiety. He elected not to start any medication.

The symptoms continued, and the patient was not aware that they were occurring. For example, one episode occurred at the dinner table with guests. The patient tapped on the adjacent dinner plate, and the guests thought he was playing a joke. The patient’s wife took him for a re-evaluation, and an episode occurred in the physician’s office.

The physician ordered a routine electroencephalogram (EEG). The EEG showed frequent left frontal temporal sharp and slow waves. No seizures were recorded. The patient was referred to an epileptologist. He was started on lacosamide, with a slowly escalating dose. Since being on a therapeutic dose the patient has not experienced any events, as reported by others.

Question 1: What is the patient’s diagnosis?

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Tics

- Partial epilepsy

- Unknown

Answer: d) Partial Epilepsy

Partial epilepsy (recurrent partial seizures) can manifest with a combination of tapping, chewing, staring, and blinking, but it is not limited to these symptoms. These abnormal, unintended movements are automatisms.

Question 2: Which adverse events may take greater precedence in the elderly and must be considered when choosing which anti-seizure medication to prescribe?

- Drowsiness

- Cognitive slowing/slow processing

- Unsteady gait

- Double vision

- All of the above

Answer: e) All of the above

Different anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) can have different adverse events. But, many potential adverse events are common to all ASDs although to differing extents, including but not limited to sleepiness/drowsiness and cognitive slowing/memory loss. Elderly patients are more prone to falls, and may have preexisting memory or cognitive issues. Adverse events should be minimized to the greatest extent possible in the elderly. Physicians should remember that each individual/case is unique.

Question 3: Which of the following demonstrates the correct match of a cause (etiology) of epilepsy and when seizures may begin due to that cause:

- Stroke – 6 months

- Brain tumor – 3 months

- Dementia – 1 year

- Idiopathic (unknown etiology) – childhood years

- None of the above

Answer: e) None of the above

The above is only a partial list of causes of epilepsy. For symptomatic epilepsy – epilepsy due to a stroke, brain tumor, or dementia, there is not a specific timeframe in which/by which the seizures have to begin. Also, a significant number of cases of epilepsy are of unknown cause (idiopathic), and in these situations seizures can begin at any age, as is the case above.

MDedge Daily News: Where the latest HCV drug combos fit in

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Psychiatrists urged to take lead in recognizing physician burnout

NEW YORK – The proportion of physicians who commit suicide each year is greater than the proportion of Americans who die of an opioid overdose, according to a series of sobering statistics on physician burnout presented at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

“There are about 400 physician suicides very year, which is proportional rate that is about twice the suicide rate in the general population,” reported Darrell G. Kirch, MD, president and chief executive officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington.

Burnout is variably defined, but characterizations typically include emotional exhaustion, a high sense of depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. In the 2015 study, the overall rate of burnout when assessed via the Maslach Burnout Inventory was 54.4%.

At 40%, the rate of burnout found among psychiatrists is lower than the mean and places them toward the bottom of the list in the rank order among specialists. Yet, 40% is still a large proportion. Moreover, Dr. Kirch believes that psychiatrists have an important role to play in recognizing and addressing this condition in others.

“ in the organization you work in,” Dr. Kirch said. The campaign to which he referred was a call to action launched last year by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Led by NAM, it is called the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience.

In the 18 months since it was launched, “more than 150 organizations, including the APA, have made commitment statements and are supporting the work of the collaborative around improving clinician well-being,” Dr. Kirch reported.

Many tools already generated by this collaboration can be found in the NAM website at nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing. This section of the website not only includes data about burnout as well as presentation slides for download on the topic, but it is expected to be “a growing repository for solutions that work,” Dr. Kirch said.

This was not news to those who attended the APA symposium. When Dr. Kirch asked the audience who had treated a colleague for burnout, almost every hand was raised. This would not be surprising, except that the leaders in this field so far have typically not been psychiatrists, Dr. Kirch said.

For example, an increasing number of medical centers are following the lead of Stanford (Calif.) University, which appointed Tate D. Shanafelt, MD, as its first chief wellness officer. However, to the knowledge of Dr. Kirch, none of the appointments have gone to a psychiatrist.

“It strikes me that if you need a chief wellness officer who not only can understand the dynamics of burnout but can understand what a short path it is from being burned out to being depressed, suicidal, or addicted, who would be better suited than a psychiatrist? I really think that in many ways, this may be a career path for psychiatrists,” Dr. Kirch said.

Even with the appointment of chief wellness officers, the problem will not soon go away. Although Dr. Kirch believes interventions are needed from the beginning of medical training, he acknowledged that eliminating burnout “is a heavy lift, because there is no single solution.” Listing regulatory burdens, administrative burdens, lack of support staff, and a sense of isolation among documented causes of burnout, he believes identifying all of the solutions to relieve stress and improve clinical satisfaction “will be a journey.”

Dr. Kirch reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK – The proportion of physicians who commit suicide each year is greater than the proportion of Americans who die of an opioid overdose, according to a series of sobering statistics on physician burnout presented at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

“There are about 400 physician suicides very year, which is proportional rate that is about twice the suicide rate in the general population,” reported Darrell G. Kirch, MD, president and chief executive officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington.

Burnout is variably defined, but characterizations typically include emotional exhaustion, a high sense of depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. In the 2015 study, the overall rate of burnout when assessed via the Maslach Burnout Inventory was 54.4%.

At 40%, the rate of burnout found among psychiatrists is lower than the mean and places them toward the bottom of the list in the rank order among specialists. Yet, 40% is still a large proportion. Moreover, Dr. Kirch believes that psychiatrists have an important role to play in recognizing and addressing this condition in others.

“ in the organization you work in,” Dr. Kirch said. The campaign to which he referred was a call to action launched last year by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Led by NAM, it is called the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience.

In the 18 months since it was launched, “more than 150 organizations, including the APA, have made commitment statements and are supporting the work of the collaborative around improving clinician well-being,” Dr. Kirch reported.

Many tools already generated by this collaboration can be found in the NAM website at nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing. This section of the website not only includes data about burnout as well as presentation slides for download on the topic, but it is expected to be “a growing repository for solutions that work,” Dr. Kirch said.

This was not news to those who attended the APA symposium. When Dr. Kirch asked the audience who had treated a colleague for burnout, almost every hand was raised. This would not be surprising, except that the leaders in this field so far have typically not been psychiatrists, Dr. Kirch said.

For example, an increasing number of medical centers are following the lead of Stanford (Calif.) University, which appointed Tate D. Shanafelt, MD, as its first chief wellness officer. However, to the knowledge of Dr. Kirch, none of the appointments have gone to a psychiatrist.

“It strikes me that if you need a chief wellness officer who not only can understand the dynamics of burnout but can understand what a short path it is from being burned out to being depressed, suicidal, or addicted, who would be better suited than a psychiatrist? I really think that in many ways, this may be a career path for psychiatrists,” Dr. Kirch said.

Even with the appointment of chief wellness officers, the problem will not soon go away. Although Dr. Kirch believes interventions are needed from the beginning of medical training, he acknowledged that eliminating burnout “is a heavy lift, because there is no single solution.” Listing regulatory burdens, administrative burdens, lack of support staff, and a sense of isolation among documented causes of burnout, he believes identifying all of the solutions to relieve stress and improve clinical satisfaction “will be a journey.”

Dr. Kirch reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK – The proportion of physicians who commit suicide each year is greater than the proportion of Americans who die of an opioid overdose, according to a series of sobering statistics on physician burnout presented at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting.

“There are about 400 physician suicides very year, which is proportional rate that is about twice the suicide rate in the general population,” reported Darrell G. Kirch, MD, president and chief executive officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington.

Burnout is variably defined, but characterizations typically include emotional exhaustion, a high sense of depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. In the 2015 study, the overall rate of burnout when assessed via the Maslach Burnout Inventory was 54.4%.

At 40%, the rate of burnout found among psychiatrists is lower than the mean and places them toward the bottom of the list in the rank order among specialists. Yet, 40% is still a large proportion. Moreover, Dr. Kirch believes that psychiatrists have an important role to play in recognizing and addressing this condition in others.

“ in the organization you work in,” Dr. Kirch said. The campaign to which he referred was a call to action launched last year by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Led by NAM, it is called the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience.

In the 18 months since it was launched, “more than 150 organizations, including the APA, have made commitment statements and are supporting the work of the collaborative around improving clinician well-being,” Dr. Kirch reported.

Many tools already generated by this collaboration can be found in the NAM website at nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing. This section of the website not only includes data about burnout as well as presentation slides for download on the topic, but it is expected to be “a growing repository for solutions that work,” Dr. Kirch said.

This was not news to those who attended the APA symposium. When Dr. Kirch asked the audience who had treated a colleague for burnout, almost every hand was raised. This would not be surprising, except that the leaders in this field so far have typically not been psychiatrists, Dr. Kirch said.

For example, an increasing number of medical centers are following the lead of Stanford (Calif.) University, which appointed Tate D. Shanafelt, MD, as its first chief wellness officer. However, to the knowledge of Dr. Kirch, none of the appointments have gone to a psychiatrist.

“It strikes me that if you need a chief wellness officer who not only can understand the dynamics of burnout but can understand what a short path it is from being burned out to being depressed, suicidal, or addicted, who would be better suited than a psychiatrist? I really think that in many ways, this may be a career path for psychiatrists,” Dr. Kirch said.

Even with the appointment of chief wellness officers, the problem will not soon go away. Although Dr. Kirch believes interventions are needed from the beginning of medical training, he acknowledged that eliminating burnout “is a heavy lift, because there is no single solution.” Listing regulatory burdens, administrative burdens, lack of support staff, and a sense of isolation among documented causes of burnout, he believes identifying all of the solutions to relieve stress and improve clinical satisfaction “will be a journey.”

Dr. Kirch reported no potential conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM APA

Small-Cell Lung Cancer

From the Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI (Dr. Mamdani) and the Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN (Dr. Jalal).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the clinical aspects and current practices of management of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: SCLC is an aggressive cancer of neuroendocrine origin with a very strong association with smoking. Approximately 25% of patients present with limited-stage disease while the remaining majority of patients have extensive-stage disease, defined as disease extending beyond one hemithorax at the time of diagnosis. SCLC is often associated with endocrine or neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes. The treatment of limited-stage disease consists of platinum-based chemotherapy administered concurrently with radiation. Patients with partial or complete response should be offered prophylactic cranial radiation (PCI). Extensive-stage disease is largely treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and the role of PCI is more controversial. The efficacy of second-line chemotherapy after disease progression on platinum based chemotherapy is limited.

- Conclusion: Despite a number of advances in the treatment of various malignancies over the period of past several years, the prognosis of patients with SCLC remains poor. There have been a number of clinical trials utilizing novel therapeutic agents to improve outcomes of these patients; however, few of them have shown marginal success in a very select subgroup of patients.

Key words: lung cancer; small-cell lung cancer.

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive cancer of neuroendocrine origin, accounting for approximately 15% of all lung cancer cases, with approximately 33,000 patients diagnosed annually [1]. The incidence of SCLC in the United States has steadily declined over the past 30 years presumably because of decrease in the percentage of smokers and change to low-tar filter cigarettes [2]. Although the incidence of SCLC has been decreasing, the incidence in women is increasing and the male-to-female incidence ratio is now 1:1 [3]. Nearly all cases of SCLC are associated with heavy tobacco exposure, making it a heterogeneous disease with complex genomic landscape consisting of thousands of mutations [4,5]. Despite a number of advances in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer over the past decade, the therapeutic landscape of SCLC remains narrow with median overall survival (OS) of 9 months in patients with advanced disease.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 61-year-old man presents to the emergency department with progressive shortness of breath and cough over the period of past 6 weeks. He also reports having had 20-lb weight loss over the same period of time. He is a current smoker and has been smoking one pack of cigarettes per day since the age of 18 years. A chest x-ray performed in the emergency department shows a right hilar mass. Computed tomography (CT) scan confirms the presence of a 4.5 cm right hilar mass with presence of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes bilaterally.

What are the next steps in diagnosis?

SCLC is characterized by rapid growth and early hematogenous metastases. Consequently, only 25% of patients have limited-stage disease at the time of diagnosis. According to the VA staging system, limited-stage disease is defined as tumor that is confined to one hemithorax and can be encompassed within one radiation field. This typically includes mediastinal lymph nodes and ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes. Extensive-stage disease is the presentation in 75% of the patients where the disease extends beyond one hemithorax. Extensive-stage disease includes presence of malignant pleural effusion and/or distant metastasis [6]. The Veterans Administration Lung Study Group (VALG) classification and staging system is more commonly used compared to the AJCC TNM staging system since it is less complex, directs treatment decisions, and correlates closely with prognosis. Given its propensity to metastasize quickly, none of the currently available screening methods have proven to be successful in early detection of SCLC. Eighty-six percent of the 125 patients that were diagnosed with SCLC while undergoing annual low-dose chest CT scans on National Lung Cancer Screening Trial had advanced disease at diagnosis [7,8]. These results highlight the fact that he majority of the SCLC develop in the interval between annual screening imaging.

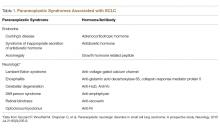

SCLC frequently presents with a large hilar mass that is symptomatic. In addition, SCLC usually presents with centrally located tumors and bulky mediastinal adenopathy. Common symptoms include shortness of breath and cough. SCLC is commonly located submucosally in the bronchus and therefore hemoptysis is not a very common symptom at the time of presentation. Patients may present with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome from local compression by the tumor. Not infrequently, SCLC is associated with paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) owing to the ectopic secretion of hormones or antibodies by the tumor cells. The PNS can be broadly categorized into endocrine and neurologic; and are summarized in Table 1.

The common sites of metastases include brain, liver, and bone. Therefore, the staging workup should include fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of chest and abdomen and bone scan can be obtained for staging in lieu of PET scan. Due to the physiologic FDG uptake, cerebral metastases cannot be assessed with sufficient certainty using the PET-CT. Therefore, brain imaging with contrast enhanced CT or MRI is also necessary. Although the incidence of metastasis to bone marrow is less than 10%, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is warranted in case of unexplained cytopenias, especially when associated with teardrop red cells or nucleated red cells on peripheral blood smear indicative of marrow infiltrative process. The tissue diagnosis is established by obtaining a biopsy of the primary tumor or one of the metastatic sites. In case of localized disease, bronchoscopy (if necessary, with endobronchial ultrasound) with biopsy of centrally located tumor and/or lymph node is required. Histologically, SCLC consists of monomorphic cells, a high nucleus:cytoplasmic ratio, and confluent necrosis. The tumor cells are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56 by immunohistochemistry. Very frequently the cells are also positive for TTF1. Although serum tumor markers, including neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and progastrin-releasing peptide (prGRP), are frequently elevated in patients with SCLC, they are of limited value in clinical practice owing to their lack of sensitivity and specificity.

Case Continued

The patient underwent FDG-PET scan that showed the presence of hypermetabolic right hilar mass in addition to enlarged and hypermetabolic bilateral mediastinal lymph nodes. There were no other areas of FDG avidity. His brain MRI did not show any evidence of brain metastasis. Thus, he was confirmed to have limited-stage SCLC.

What is the standard of care for limited-stage SCLC?

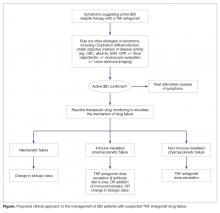

SCLC is exquisitely sensitive to both chemotherapy and radiation, especially at the time of initial presentation. The standard of care for the treatment of limited stage SCLC is 4 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with thoracic radiation started within the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy (Figure 1).

Choice of Chemotherapy

Etoposide and cisplatin is the most commonly used initial combination chemotherapy regimen [9]. This combination has largely replaced anthracycline-based regimens given its favorable efficacy and toxicity profile [10–12]. Several small randomized trials have shown comparable efficacy of carboplatin and etoposide in extensive stage SCLC [13–15]. A meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials, including 663 patients with SCLC, comparing cisplatin-based versus carboplatin-based regimens where 32% of patients had limited stage disease and 68% had extensive stage disease showed no statistically significant difference in the response rate, progression free survival (PFS), or OS between the two regimens [16]. Therefore, in clinical practice carboplatin is frequently used instead of cisplatin in patients with extensive-stage disease. In patients with limited-stage disease, cisplatin is still the drug of choice. However, the toxicity profile of the two regimens is different. Cisplatin based regimens are more commonly associated with neuropathy, nephrotoxicity, and chemotherapy induced nausea/vomiting [13], while carboplatin-based regimens are more myelosuppressive [17]. In addition, the combination of thoracic radiation with either of these regiments is associated with higher risk of esophagitis, pneumonitis, and myelosuppression [18]. The use of myeloid growth factors is not recommended in patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiation [19]. Of note, intravenous (IV) etoposide is always preferred over oral etoposide, especially in curative setting given unreliable absorption and bioavailability of oral formulations.

Thoracic Radiation

The addition of thoracic radiation to platinum-etoposide chemotherapy improves local control and OS. Two meta-analyses of 13 trials including more than 2000 patients have shown 25% to 30% decrease in local failure and 5% to 7% increase in 2-year OS with chemoradiation compared to chemotherapy alone in limited stage SCLC [20,21]. Early (with the first 2 cycles) concurrent thoracic radiation is superior to delayed and/or sequential radiation in terms of local control and OS [18,22,23]. The dose and fractionation of thoracic radiation in limited-stage SCLC has remained a controversial issue. The ECOG/RTOG randomized trial compared 45 Gy radiation delivered twice daily over a period of 3 weeks with once a day over 5 weeks, concurrently with chemotherapy. The twice a day regimen led to 10% improvement in 5-year OS (26% vs 16%), but higher incidence of grade 3 and 4 adverse events [24]. Despite the survival advantage demonstrated by hyperfractionated radiotherapy, the results need to be interpreted with caution because the radiation doses are not biologically equivalent. In addition the difficult logistics of patients receiving radiation twice a day has limited the routine implementation of this strategy. Subsequently, another randomized phase III trial (CONVERT) compared 45 Gy twice daily with 66 Gy once daily radiation in this setting. This trial did not show any difference in OS. The patients in twice daily arm had higher incidence of grade 4 neutropenia [25]. Considering the results of these trials, both strategies—45 Gy fractionated twice daily or 60 Gy fractionated once daily, delivered concurrently with chemotherapy—are acceptable in the setting of limited-stage SCLC. However, quite often hyperfractionated regimen is not feasible for the patients and many radiation oncology centers. Hopefully the CALBG 30610 study, which is ongoing, will clarify the optimal radiation schedule for limited-stage disease.

Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation

Approximately 75% of patients with limited-stage disease experience disease recurrence and brain is the site of recurrence in approximately half of these patients. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) consisting of 25 Gy radiation delivered in 10 fractions has been shown to be effective in decreasing the incidence of cerebral metastases [26–28]. Although individual small studies have not shown survival benefit of PCI because of small sample size and limited power, a meta-analysis of these studies has shown 25% decrease in the 3-year incidence of brain metastasis and 5.4% increase in 3-year OS [27]. The majority of patients included in these studies had limited-stage disease. Therefore, PCI is the standard of care for patients with limited-stage disease who attain a partial or complete response to chemoradiation.

Role of Surgery

Surgical resection may be an acceptable choice in a very limited subset of patients with peripherally located small (< 5 cm) tumors where mediastinal lymph nodes have been confirmed to be uninvolved with complete mediastinal staging [29,30]. Most of the data in this setting are derived from retrospective studies [31,32]. A 5-year OS of 40% to 60% has been has been reported with this strategy in patients with clinical stage I disease. In general, when surgery is considered, lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection followed by chemotherapy (if no nodal involvement) or chemoradiation (if nodal involvement) is recommended [33,34]. Wedge or segmental resections are not considered to be optimum surgical options.

Case Continued

The patient received 4 cycles of cisplatin and etoposide along with 70 Gy radiation concurrently with the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy. His post-treatment CT scans showed partial response (PR). The patient underwent PCI 6 weeks after completion of treatment. Eighteen months later, the patient comes to the clinic for routine follow-up. He is doing generally well except for mildly decreased appetite and unintentional loss of 5 lb weight. His CT scans demonstrate multiple hypodense liver lesions ranging from 7 mm to 2 cm in size and a 2 cm left adrenal gland lesion highly concerning for metastasis. FDG PET scan confirmed the adrenal and liver lesions to be hypermetabolic. In addition, the PET showed multiple FDG avid bone lesions throughout the spine. Brain MRI was negative for any brain metastasis.

What is the standard of care for extensive-stage SCLC?

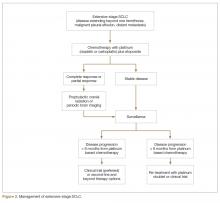

For extensive-stage SCLC, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, with the goals of treatment being prolongation of survival, prevention or alleviation of cancer-related symptoms, and improvement in quality of life. The combination of etoposide with a platinum agent (carboplatin or cisplatin) is the preferred first-line treatment option (Figure 2).

Multiple attempts at improving first-line chemotherapy in extensive-stage disease have failed to show any meaningful difference in OS. For example, addition of ifosfamide, palifosfamide, cyclophosphamide, taxane, or anthracycline to platinum doublet failed to show improvement in OS and led to more toxicity [39–42]. Additionally, the use of alternating or cyclic chemotherapies in an attempt to curb drug resistance has also failed to show survival benefit [43–45]. The addition of antiangiogenic agent bevacizumab to standard platinum-based doublet has not yielded prolongation of OS in SCLC and led to unacceptably higher rate of tracheoesophageal fistula when used in conjunction with chemoradiation in limited-stage disease [46–51]. Finally, the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab in combination with platinum plus etoposide failed to improve PFS or OS compared to platinum plus etoposide alone in a recent phase III trial and maintenance pembrolizumab after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy did not improve PFS [52,53].

Patients with extensive-stage disease who have brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis can be treated with systemic chemotherapy first if brain metastases are asymptomatic and there is significant extracranial disease burden. In that case, whole brain radiotherapy should be given after completion of systemic therapy.

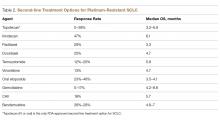

Second-Line Therapy

Despite being exquisitely chemo-sensitive, SCLC is associated with very poor prognosis largely because of invariable disease progression following first-line therapy and lack of effective second-line treatment options that can lead to appreciable disease control. The choice of second-line treatment is predominantly determined by the time of disease relapse since first-line platinum based therapy. If this interval is 6 months or longer, re-treatment utilizing the same platinum doublet is appropriate. However, if the interval is 6 months or less, second-line systemic therapy options should be explored. Unfortunately, the response rate tends to be less than 10% with most of the second-line therapies in platinum-resistant disease (defined as disease progression within 3 months of receiving platinum-based therapy). If the disease progression occurs between 3 to 6 months since platinum-based therapy, the response rate with second-line chemotherapy is in the range of 25% [54,55]. A number of second-line chemotherapy options have been explored in small studies, including topotecan, irinotecan, paclitaxel, docetaxel, temozolomide, vinorelbine, oral etoposide, gemcitabine, bendamustine, and CAV (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine) (Table 2).

Immunotherapy

The role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of SCLC is evolving and currently there are no FDA-approved immunotherapy agents in SCLC. A recently conducted phase I/II trial (CheckMate 032) of anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab with or without anti-CTLA-1 antibody ipilimumab in patients with relapsed SCLC reported a response rate of 10% with nivolumab 3 mg/kg and 21% with nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg. The 2-year OS was 26% with the combination and 14% with single agent nivolumab [56,57]. Only 18% of patients had PD-L1 expression of ≥ 1% and the response rate did not correlate with PD-L1 status. The rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was approximately 20% and only 10% of patients discontinued treatment because of toxicity. Based on these data, nivolumab plus ipilimumab is now included in the NCCN guidelines as one of the options for patients with SCLC who experience disease relapse within 6 months of receiving platinum-based therapy; however, it is questionable whether routine use of this combination is justified based on currently available data. However the evidence for the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab remains limited. This efficacy and toxicity data of both randomized and nonrandomized cohorts were presented together making it hard to interpret the results.

Another phase Ib study (KEYNOTE-028) utilizing anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks in patients with relapsed SCLC after receiving one or more prior lines of therapy and PD-L1 expression of ≥ 1% showed a response rate of 33% with median duration of response of 19 months and 1-year OS of 38% [58]. Although only 28% of screened patients had PD-L1 expression of ≥ 1% , these results indicated that at least a subset of SCLC patients are able to achieve durable responses with immune checkpoint inhibition. A number of clinical trials utilizing immune checkpoint inhibitors in various combinations and settings are currently underway.

Role of Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation

The role of PCI in extensive-stage SCLC is not clearly defined. A randomized phase III trial conducted by EORTC comparing PCI with no PCI in patients with extensive-stage SCLC who had attained partial or complete response to initial platinum-based chemotherapy showed decrease in the incidence of symptomatic brain metastasis and improvement in 1-year OS with PCI. However, this trial did not require mandatory brain imaging prior to PCI and therefore it is unclear if some patients in the PCI group had asymptomatic brain metastasis prior to enrollment and therefore received therapeutic benefit from brain radiation. Additionally, the dose and fractionation of PCI was not standardized across patient groups. A more recent phase III study conducted in Japan that compared PCI (25Gy in 10 fractions) with no PCI reported no difference in survival between the two groups. As opposed to EORTC study, the Japanese study did require baseline brain imaging to confirm absence of brain metastasis prior to enrollment. In addition, the patients in the control arm underwent periodic brain MRI to allow early detection of brain metastasis [59]. Given the emergence of the new data, the impact of PCI on survival in patients with extensive-stage SCLC is unproven and PCI likely has a role in a highly select small group of patients with extensive-stage SCLC. PCI is not recommended for patients with poor performance status (ECOG PS 3–4) or underlying neurocognitive disorders [33,60]. NMDA receptor antagonist memantine can be used in patients undergoing PCI to delay the occurrence of cognitive dysfunction [61]. Memantine 20 mg daily delayed time to cognitive decline and reduced the rate of decline in memory, executive function, and processing speed compared to placebo in patients receiving whole brain radiation [61].

Role of Radiation

A subset of patients with extensive-stage SCLC may benefit from consolidative thoracic radiation after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy. A randomized trial including patients who achieved complete or near complete response after 3 cycles of cisplatin plus etoposide compared thoracic radiation in combination with continued chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone [62]. The median OS was longer with the addition of thoracic radiation compared to chemotherapy alone. Another phase III trial did not show improvement in 1-year OS with consolidative thoracic radiation, but 2-year OS and 6-month PFS were longer [63]. In general, consolidative thoracic radiation benefits patients who have residual thoracic disease and low-bulk extrathoracic disease that has responded to systemic therapy [64]. In addition, patients who initially presented with bulky symptomatic thoracic disease should also be considered for consolidative radiation.

Similar to other solid tumors, radiation should be utilized for palliative purposes in patients with painful bone metastasis, spine cord compression, or brain metastasis. Surgery is generally not recommended for spinal cord compression given the short life expectancy with extensive stage disease. Whole brain radiotherapy is preferred over SRS because of frequent presence of micrometastasis even in the setting of one or two radiographically evident brain metastasis.

Novel Therapies

A very complex genetic landscape of SCLC accounts for its resistance to conventional therapy and a high recurrence rate; however, at the same time this complexity can form the basis for effective targeted therapy for the disease. One of the major limitations to the development of targeted therapies in SCLC is limited availability of tissue owing to small tissue samples and frequent presence of significant necrosis in the samples. In recent years, several different therapeutic strategies and targeted agents have been under investigation for their potential role in SCLC. Several of them, including EGFR TKIs, BCR-ABL TKIs, mTOR inhibitors, and VEGF inhibitors, have been unsuccessful in showing a survival advantage in this disease. Several others including PARP inhibitors, cellular developmental pathway inhibitors and antibody drug conjugates are being tested. A phase I study of veliparib combined with cisplatin and etoposide in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage SCLC demonstrated complete response in 14.3%, partial response in 57.1%, and stable disease in 28.6% of patients with acceptable safety profile [65]. So far, none of these agents are approved for use in SCLC and the majority are in early phase clinical trials [66].

One of the emerging targets in the treatment of SCLC is DLL3. DLL3 is expressed on > 80% SCLCL tumor cells and cancer stem cells. Rovalpituzumab tesirine (ROVA-T) is an antibody drug conjugate consisting of humanized anti-DLL3 monoclonal antibody linked to SC-DR002, a DNA-crosslinking agent. A phase I trial of ROVA-T in patients with relapsed SCLC after 1 or 2 prior lines of therapies reported a response rate of 31% in patients with DLL3 expression of ≥ 50%. The median duration of response and mPFS were 4.6 months [67]. ROVA-T is currently in later phases of clinical trials and has a potential to serve as one of the options for patients with extensive-stage disease after disease progression on platinum-based therapy.

Response Assessment/Surveillance

For patients undergoing treatment for limited-stage SCLC, response assessment with contrast-enhanced CT of the chest/abdomen should be performed after completion of 4 cycles of chemotherapy and thoracic radiation. The surveillance guidelines consist of history, physical exam, and imaging every 3 months during 1st 2 years, every 6 months during the 3rdyear, and annually thereafter. If PCI is not performed, brain MRI or contrast enhanced CT scan should be performed every 3 to 4 months during the first 2 years of follow-up. For extensive-stage disease, response assessment should be performed after every 2 cycles of therapy. After completion of therapy, history, physical exam, and imaging should be done every 2 months during the 1st year, every 3 to 4 months during year 2 and 3, every 6 months during years 4 and 5, and annually thereafter. Routine use of PET scan for surveillance is not recommended. Any new pulmonary nodule should prompt evaluation for a second primary lung malignancy. Finally, smoking cessation counseling is an integral part of management of any patient with SCLC and should be included with every clinic visit.

Corresponding author: Hirva Mamdani, MD, Karmanos Cancer Institute, 4100 John R, Detroit, MI 48201, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed April 11, 2018.

2. Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4539–44.

3. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Updated April 2, 2018. Accessed April 11, 2018.

4. Varghese AM, Zakowski MF, Yu HA, et al. Small-cell lung cancers in patients who never smoked cigarettes. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:892–6.

5. Pleasance ED, Stephens PJ, O’Meara S, et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature 2010;463:184–90.

6. Green RA, Humphrey E, Close H, Patno ME. Alkylating agents in bronchogenic carcinoma. Am J Med 1969;46:516–25.

7. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395–409.

8. Aberle DR, DeMello S, Berg CD, et al. Results of the two incidence screenings in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med 2013;369:920–31.

9. Evans WK, Shepherd FA, Feld R, et al. VP-16 and cisplatin as first-line therapy for small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1471–7.

10. Pujol JL, Carestia L, Daurés JP. Is there a case for cisplatin in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer? A meta-analysis of randomized trials of a cisplatin-containing regimen versus a regimen without this alkylating agent. Br J Cancer 2000;83:8–15.

11. Mascaux C, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, et al; European Lung Cancer Working Party (ELCWP). A systematic review of the role of etoposide and cisplatin in the chemotherapy of small cell lung cancer with methodology assessment and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2000;30:23–36.

12. Sundstrøm S, Bremnes RM, Kaasa S, et al; Norwegian Lung Cancer Study Group. Cisplatin and etoposide regimen is superior to cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and vincristine regimen in small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized phase III trial with 5 years’ follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4665–72.

13. Hatfield LA, Huskamp HA, Lamont EB. Survival and toxicity after cisplatin plus etoposide versus carboplatin plus etoposide for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer in elderly patients. J Oncol Pract 2016;12(7):666–73.

14. Okamoto H, Watanabe K, Kunikane H, et al. Randomised phase III trial of carboplatin plus etoposide vs split doses of cisplatin plus etoposide in elderly or poor-risk patients with extensive disease small-cell lung cancer: JCOG 9702. Br J Cancer 2007;97:162–9.

15. Skarlos DV, Samantas E, Kosmidis P, et al. Randomized comparison of etoposide-cisplatin vs. etoposide-carboplatin and irradiation in small-cell lung cancer. A Hellenic Co-operative Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol 1994;5:601–7.

16. Rossi A, Di Maio M, Chiodini P, et al. Carboplatin- or cisplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of small-cell lung cancer: the COCIS meta-analysis of individual patient data J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1692–8.

17. Bishop JF, Raghavan D, Stuart-Harris R, et al. Carboplatin (CBDCA, JM-8) and VP-16-213 in previously untreated patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:1574–8.

18. Takada M, Fukuoka M, Kawahara M, Sugiura T, Yokoyama A, Yokota S, et al. Phase III study of concurrent versus sequential thoracic radiotherapy in combination with cisplatin and etoposide for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: results of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study 9104. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3054–60.

19. Bunn PA Jr, Crowley J, Kelly K, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: a prospective phase III randomized study of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1632–41.

20. Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1618–24.

21. Warde P, Payne D. Does thoracic irradiation improve survival and local control in limited-stage small-cell carcinoma of the lung? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 1992;10(6):890–5.

22. Murray N, Coy P, Pater JL, Hodson I, Arnold A, Zee BC, et al. Importance of timing for thoracic irradiation in the combined modality treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer. The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:336–44.

23. De Ruysscher D, Lueza B, Le Péchoux C, et al. Impact of thoracic radiotherapy timing in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: usefulness of the individual patient data meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2016;27(10):1818–28.

24. Turrisi AT 3rd, Kim K, Blum R, et al. Twice-daily compared with once-daily thoracic radiotherapy in limited small-cell lung cancer treated concurrently with cisplatin and etoposide. N Engl J Med 1999;340(4):265–71.

25. Faivre-Finn C, Snee M, Ashcroft L, et al. Concurrent once-daily versus twice-daily chemoradiotherapy in patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer (CONVERT): an open-label, phase 3, randomised, superiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18(8):1116–25.

26. Arriagada R, Le Chevalier T, Borie F, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87(3):183–90.

27. Aupérin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, Le Pechoux C, Gregor A, Stephens RJ, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med 1999;341:476–84.

28. Le Péchoux C, Dunant A, Senan S, et al; Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation (PCI) Collaborative Group. Standard-dose versus higher-dose prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) in patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer in complete remission after chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy (PCI 99-01, EORTC 22003-08004, RTOG 0212, and IFCT 99-01): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10(5):467–74.

29. Schneider BJ, Saxena A, Downey RJ. Surgery for early-stage small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;9(10):1132–9.

30. Inoue M, Nakagawa K, Fujiwara K, et al. Results of preoperative mediastinoscopy for small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1620–3.

31. Lim E, Belcher E, Yap YK, et al. The role of surgery in the treatment of limited disease small cell lung cancer: time to reevaluate. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1267–71.

32. Inoue M, Miyoshi S, Yasumitsu T, et al. Surgical results for small cell lung cancer based on the new TNM staging system. Thoracic Surgery Study Group of Osaka University, Osaka, Japan. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1615–9.

33. Yang CF, Chan DY, Speicher PJ, Gulack BC, Wang X, Hartwig MG, et al. Role of adjuvant therapy in a population-based cohort of patients with early-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1057–64.

34. Shepherd FA, Evans WK, Feld R, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy following surgical resection for small-cell carcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:832–8.

35. Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, et al; Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;346:85–91.

36. Lara PN Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2530–5.

37. Chute JP, Chen T, Feigal E, et al. Twenty years of phase III trials for patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: perceptible progress. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1794–801.

38. Zhou H, Zeng C, Wei Y, Zhou J, Yao W. Duration of chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. PloS One 2013;8:e73805.

39. Loehrer PJ Sr, Ansari R, Gonin R, et al. Cisplatin plus etoposide with and without ifosfamide in extensive small-cell lung cancer: a Hoosier Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1995 Oct;13:2594–9.

40. Pujol JL, Daurés JP, Riviére A, et al. Etoposide plus cisplatin with or without the combination of 4’-epidoxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide in treatment of extensive small-cell lung cancer: a French Federation of Cancer Institutes multicenter phase III randomized study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:300–8.

41. Berghmans T, Scherpereel A, Meert AP, et al; European Lung Cancer Working Party (ELCWP). A phase III randomized study comparing a chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide to a etoposide regimen without cisplatin for patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer. Front Oncol 2017;7:217.

42. Jalal SI, Lavin P, Lo G, et al. Carboplatin and etoposide with or without palifosfamide in untreated extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a Multicenter, Adaptive, Randomized Phase III Study (MATISSE). J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2619–23.

43. Fukuoka M, Furuse K, Saijo N, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus cisplatin and etoposide versus alternation of these regimens in small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:855–61.

44. Roth BJ, Johnson DH, Einhorn LH, et al. Randomized study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus etoposide and cisplatin versus alternation of these two regimens in extensive small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Southeastern Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1992;10(2):282–91.

45. Miles DW, Earl HM, Souhami RL, Harper PG, Rudd R, Ash CM, et al. Intensive weekly chemotherapy for good-prognosis patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:280–5.

46. Petrioli R, Roviello G, Laera L, et al. Cisplatin, etoposide, and bevacizumab regimen followed by oral etoposide and bevacizumab maintenance treatment in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: a single-institution experience. Clin Lung Cancer 2015;16:e229–34.

47. Spigel DR, Greco FA, Zubkus JD, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in the treatment of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4(12):1555–60.

48. Spigel DR, Townley PM, Waterhouse DM, et al. Randomized phase II study of bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in previously untreated extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: results from the SALUTE trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(16):2215–22.

49. Horn L, Dahlberg SE, Sandler AB, et al. Phase II study of cisplatin plus etoposide and bevacizumab for previously untreated, extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3501. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(35):6006–11.

50. Tiseo M, Boni L, Ambrosio F, et al. Italian, multicenter, phase III, randomized study of cisplatin plus etoposide with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment in extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: the GOIRC-AIFA FARM6PMFJM trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1281–7.

51. Pujol JL, Lavole A, Quoix E, et al. Randomized phase II-III study of bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in previously untreated extensive small-cell lung cancer: results from the IFCT-0802 trialdagger. Ann Oncol 2015;26:908–14.

52. Gadgeel SM, Ventimiglia J, Kalemkerian GP, et al. Phase II study of maintenance pembrolizumab (pembro) in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) patients (pts). J Clin Oncol 2017;35(15_suppl):8504-. [Can’t find the rest of the reference]

53. Reck M, Luft A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III randomized trial of ipilimumab plus etoposide and platinum versus placebo plus etoposide and platinum in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3740–8.

54. Owonikoko TK, Behera M, Chen Z, et al. A systematic analysis of efficacy of second-line chemotherapy in sensitive and refractory small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:866–72.

55. Postmus PE, Berendsen HH, van Zandwijk N, et al. Retreatment with the induction regimen in small cell lung cancer relapsing after an initial response to short term chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987;23:1409–11.

56. Hellmann MD, Ott PA, Zugazagoitia J, Ready NE, Hann CL, Braud FGD, et al. Nivolumab (nivo) ± ipilimumab (ipi) in advanced small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): First report of a randomized expansion cohort from CheckMate 032. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(15_suppl):8503-. [Can’t find the rest of the reference]

57. Antonia SJ, López-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:883–95.

58. Ott PA, Elez E, Hiret S, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: results from the Phase Ib KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3823–9.

59. Takahashi T, Yamanaka T, Seto T, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation versus observation in patients with extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:663–71.

60. Slotman BJ, Mauer ME, Bottomley A, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in extensive disease small-cell lung cancer: short-term health-related quality of life and patient reported symptoms: results of an international Phase III randomized controlled trial by the EORTC Radiation Oncology and Lung Cancer Groups. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(1):78–84.

61. Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, et al; Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG). Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro Oncol 2013;15:1429–37.

62. Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Nikolic N, et al. Role of radiation therapy in the combined-modality treatment of patients with extensive disease small-cell lung cancer: a randomized study. J Clin Oncol 1999;17(7):2092–9.

63. Slotman BJ, van Tinteren H, Praag JO, et al. Use of thoracic radiotherapy for extensive stage small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:36–42.

64. Slotman BJ, van Tinteren H, Praag JO, Knegjens JL, El Sharouni SY, Hatton M, et al. Radiotherapy for extensive stage small-cell lung cancer - authors’ reply. Lancet 2015;385:1292–3.

65. Owonikoko TK, Dahlberg SE, Khan SA, et al. A phase 1 safety study of veliparib combined with cisplatin and etoposide in extensive stage small cell lung cancer: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2511). Lung Cancer. 2015 ;89:66–70.

66. Mamdani H, Induru R, Jalal SI. Novel therapies in small cell lung cancer. Translational lung cancer research. 2015;4:533–44.

67. Rudin CM, Pietanza MC, Bauer TM, et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: a first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:42–51.

From the Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI (Dr. Mamdani) and the Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN (Dr. Jalal).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the clinical aspects and current practices of management of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: SCLC is an aggressive cancer of neuroendocrine origin with a very strong association with smoking. Approximately 25% of patients present with limited-stage disease while the remaining majority of patients have extensive-stage disease, defined as disease extending beyond one hemithorax at the time of diagnosis. SCLC is often associated with endocrine or neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes. The treatment of limited-stage disease consists of platinum-based chemotherapy administered concurrently with radiation. Patients with partial or complete response should be offered prophylactic cranial radiation (PCI). Extensive-stage disease is largely treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and the role of PCI is more controversial. The efficacy of second-line chemotherapy after disease progression on platinum based chemotherapy is limited.

- Conclusion: Despite a number of advances in the treatment of various malignancies over the period of past several years, the prognosis of patients with SCLC remains poor. There have been a number of clinical trials utilizing novel therapeutic agents to improve outcomes of these patients; however, few of them have shown marginal success in a very select subgroup of patients.

Key words: lung cancer; small-cell lung cancer.

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive cancer of neuroendocrine origin, accounting for approximately 15% of all lung cancer cases, with approximately 33,000 patients diagnosed annually [1]. The incidence of SCLC in the United States has steadily declined over the past 30 years presumably because of decrease in the percentage of smokers and change to low-tar filter cigarettes [2]. Although the incidence of SCLC has been decreasing, the incidence in women is increasing and the male-to-female incidence ratio is now 1:1 [3]. Nearly all cases of SCLC are associated with heavy tobacco exposure, making it a heterogeneous disease with complex genomic landscape consisting of thousands of mutations [4,5]. Despite a number of advances in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer over the past decade, the therapeutic landscape of SCLC remains narrow with median overall survival (OS) of 9 months in patients with advanced disease.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 61-year-old man presents to the emergency department with progressive shortness of breath and cough over the period of past 6 weeks. He also reports having had 20-lb weight loss over the same period of time. He is a current smoker and has been smoking one pack of cigarettes per day since the age of 18 years. A chest x-ray performed in the emergency department shows a right hilar mass. Computed tomography (CT) scan confirms the presence of a 4.5 cm right hilar mass with presence of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes bilaterally.

What are the next steps in diagnosis?

SCLC is characterized by rapid growth and early hematogenous metastases. Consequently, only 25% of patients have limited-stage disease at the time of diagnosis. According to the VA staging system, limited-stage disease is defined as tumor that is confined to one hemithorax and can be encompassed within one radiation field. This typically includes mediastinal lymph nodes and ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes. Extensive-stage disease is the presentation in 75% of the patients where the disease extends beyond one hemithorax. Extensive-stage disease includes presence of malignant pleural effusion and/or distant metastasis [6]. The Veterans Administration Lung Study Group (VALG) classification and staging system is more commonly used compared to the AJCC TNM staging system since it is less complex, directs treatment decisions, and correlates closely with prognosis. Given its propensity to metastasize quickly, none of the currently available screening methods have proven to be successful in early detection of SCLC. Eighty-six percent of the 125 patients that were diagnosed with SCLC while undergoing annual low-dose chest CT scans on National Lung Cancer Screening Trial had advanced disease at diagnosis [7,8]. These results highlight the fact that he majority of the SCLC develop in the interval between annual screening imaging.

SCLC frequently presents with a large hilar mass that is symptomatic. In addition, SCLC usually presents with centrally located tumors and bulky mediastinal adenopathy. Common symptoms include shortness of breath and cough. SCLC is commonly located submucosally in the bronchus and therefore hemoptysis is not a very common symptom at the time of presentation. Patients may present with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome from local compression by the tumor. Not infrequently, SCLC is associated with paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) owing to the ectopic secretion of hormones or antibodies by the tumor cells. The PNS can be broadly categorized into endocrine and neurologic; and are summarized in Table 1.

The common sites of metastases include brain, liver, and bone. Therefore, the staging workup should include fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of chest and abdomen and bone scan can be obtained for staging in lieu of PET scan. Due to the physiologic FDG uptake, cerebral metastases cannot be assessed with sufficient certainty using the PET-CT. Therefore, brain imaging with contrast enhanced CT or MRI is also necessary. Although the incidence of metastasis to bone marrow is less than 10%, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is warranted in case of unexplained cytopenias, especially when associated with teardrop red cells or nucleated red cells on peripheral blood smear indicative of marrow infiltrative process. The tissue diagnosis is established by obtaining a biopsy of the primary tumor or one of the metastatic sites. In case of localized disease, bronchoscopy (if necessary, with endobronchial ultrasound) with biopsy of centrally located tumor and/or lymph node is required. Histologically, SCLC consists of monomorphic cells, a high nucleus:cytoplasmic ratio, and confluent necrosis. The tumor cells are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and CD56 by immunohistochemistry. Very frequently the cells are also positive for TTF1. Although serum tumor markers, including neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and progastrin-releasing peptide (prGRP), are frequently elevated in patients with SCLC, they are of limited value in clinical practice owing to their lack of sensitivity and specificity.

Case Continued

The patient underwent FDG-PET scan that showed the presence of hypermetabolic right hilar mass in addition to enlarged and hypermetabolic bilateral mediastinal lymph nodes. There were no other areas of FDG avidity. His brain MRI did not show any evidence of brain metastasis. Thus, he was confirmed to have limited-stage SCLC.

What is the standard of care for limited-stage SCLC?

SCLC is exquisitely sensitive to both chemotherapy and radiation, especially at the time of initial presentation. The standard of care for the treatment of limited stage SCLC is 4 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with thoracic radiation started within the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy (Figure 1).

Choice of Chemotherapy

Etoposide and cisplatin is the most commonly used initial combination chemotherapy regimen [9]. This combination has largely replaced anthracycline-based regimens given its favorable efficacy and toxicity profile [10–12]. Several small randomized trials have shown comparable efficacy of carboplatin and etoposide in extensive stage SCLC [13–15]. A meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials, including 663 patients with SCLC, comparing cisplatin-based versus carboplatin-based regimens where 32% of patients had limited stage disease and 68% had extensive stage disease showed no statistically significant difference in the response rate, progression free survival (PFS), or OS between the two regimens [16]. Therefore, in clinical practice carboplatin is frequently used instead of cisplatin in patients with extensive-stage disease. In patients with limited-stage disease, cisplatin is still the drug of choice. However, the toxicity profile of the two regimens is different. Cisplatin based regimens are more commonly associated with neuropathy, nephrotoxicity, and chemotherapy induced nausea/vomiting [13], while carboplatin-based regimens are more myelosuppressive [17]. In addition, the combination of thoracic radiation with either of these regiments is associated with higher risk of esophagitis, pneumonitis, and myelosuppression [18]. The use of myeloid growth factors is not recommended in patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiation [19]. Of note, intravenous (IV) etoposide is always preferred over oral etoposide, especially in curative setting given unreliable absorption and bioavailability of oral formulations.

Thoracic Radiation

The addition of thoracic radiation to platinum-etoposide chemotherapy improves local control and OS. Two meta-analyses of 13 trials including more than 2000 patients have shown 25% to 30% decrease in local failure and 5% to 7% increase in 2-year OS with chemoradiation compared to chemotherapy alone in limited stage SCLC [20,21]. Early (with the first 2 cycles) concurrent thoracic radiation is superior to delayed and/or sequential radiation in terms of local control and OS [18,22,23]. The dose and fractionation of thoracic radiation in limited-stage SCLC has remained a controversial issue. The ECOG/RTOG randomized trial compared 45 Gy radiation delivered twice daily over a period of 3 weeks with once a day over 5 weeks, concurrently with chemotherapy. The twice a day regimen led to 10% improvement in 5-year OS (26% vs 16%), but higher incidence of grade 3 and 4 adverse events [24]. Despite the survival advantage demonstrated by hyperfractionated radiotherapy, the results need to be interpreted with caution because the radiation doses are not biologically equivalent. In addition the difficult logistics of patients receiving radiation twice a day has limited the routine implementation of this strategy. Subsequently, another randomized phase III trial (CONVERT) compared 45 Gy twice daily with 66 Gy once daily radiation in this setting. This trial did not show any difference in OS. The patients in twice daily arm had higher incidence of grade 4 neutropenia [25]. Considering the results of these trials, both strategies—45 Gy fractionated twice daily or 60 Gy fractionated once daily, delivered concurrently with chemotherapy—are acceptable in the setting of limited-stage SCLC. However, quite often hyperfractionated regimen is not feasible for the patients and many radiation oncology centers. Hopefully the CALBG 30610 study, which is ongoing, will clarify the optimal radiation schedule for limited-stage disease.

Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation

Approximately 75% of patients with limited-stage disease experience disease recurrence and brain is the site of recurrence in approximately half of these patients. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) consisting of 25 Gy radiation delivered in 10 fractions has been shown to be effective in decreasing the incidence of cerebral metastases [26–28]. Although individual small studies have not shown survival benefit of PCI because of small sample size and limited power, a meta-analysis of these studies has shown 25% decrease in the 3-year incidence of brain metastasis and 5.4% increase in 3-year OS [27]. The majority of patients included in these studies had limited-stage disease. Therefore, PCI is the standard of care for patients with limited-stage disease who attain a partial or complete response to chemoradiation.

Role of Surgery

Surgical resection may be an acceptable choice in a very limited subset of patients with peripherally located small (< 5 cm) tumors where mediastinal lymph nodes have been confirmed to be uninvolved with complete mediastinal staging [29,30]. Most of the data in this setting are derived from retrospective studies [31,32]. A 5-year OS of 40% to 60% has been has been reported with this strategy in patients with clinical stage I disease. In general, when surgery is considered, lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection followed by chemotherapy (if no nodal involvement) or chemoradiation (if nodal involvement) is recommended [33,34]. Wedge or segmental resections are not considered to be optimum surgical options.

Case Continued

The patient received 4 cycles of cisplatin and etoposide along with 70 Gy radiation concurrently with the first 2 cycles of chemotherapy. His post-treatment CT scans showed partial response (PR). The patient underwent PCI 6 weeks after completion of treatment. Eighteen months later, the patient comes to the clinic for routine follow-up. He is doing generally well except for mildly decreased appetite and unintentional loss of 5 lb weight. His CT scans demonstrate multiple hypodense liver lesions ranging from 7 mm to 2 cm in size and a 2 cm left adrenal gland lesion highly concerning for metastasis. FDG PET scan confirmed the adrenal and liver lesions to be hypermetabolic. In addition, the PET showed multiple FDG avid bone lesions throughout the spine. Brain MRI was negative for any brain metastasis.

What is the standard of care for extensive-stage SCLC?

For extensive-stage SCLC, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, with the goals of treatment being prolongation of survival, prevention or alleviation of cancer-related symptoms, and improvement in quality of life. The combination of etoposide with a platinum agent (carboplatin or cisplatin) is the preferred first-line treatment option (Figure 2).

Multiple attempts at improving first-line chemotherapy in extensive-stage disease have failed to show any meaningful difference in OS. For example, addition of ifosfamide, palifosfamide, cyclophosphamide, taxane, or anthracycline to platinum doublet failed to show improvement in OS and led to more toxicity [39–42]. Additionally, the use of alternating or cyclic chemotherapies in an attempt to curb drug resistance has also failed to show survival benefit [43–45]. The addition of antiangiogenic agent bevacizumab to standard platinum-based doublet has not yielded prolongation of OS in SCLC and led to unacceptably higher rate of tracheoesophageal fistula when used in conjunction with chemoradiation in limited-stage disease [46–51]. Finally, the immune checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab in combination with platinum plus etoposide failed to improve PFS or OS compared to platinum plus etoposide alone in a recent phase III trial and maintenance pembrolizumab after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy did not improve PFS [52,53].

Patients with extensive-stage disease who have brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis can be treated with systemic chemotherapy first if brain metastases are asymptomatic and there is significant extracranial disease burden. In that case, whole brain radiotherapy should be given after completion of systemic therapy.

Second-Line Therapy

Despite being exquisitely chemo-sensitive, SCLC is associated with very poor prognosis largely because of invariable disease progression following first-line therapy and lack of effective second-line treatment options that can lead to appreciable disease control. The choice of second-line treatment is predominantly determined by the time of disease relapse since first-line platinum based therapy. If this interval is 6 months or longer, re-treatment utilizing the same platinum doublet is appropriate. However, if the interval is 6 months or less, second-line systemic therapy options should be explored. Unfortunately, the response rate tends to be less than 10% with most of the second-line therapies in platinum-resistant disease (defined as disease progression within 3 months of receiving platinum-based therapy). If the disease progression occurs between 3 to 6 months since platinum-based therapy, the response rate with second-line chemotherapy is in the range of 25% [54,55]. A number of second-line chemotherapy options have been explored in small studies, including topotecan, irinotecan, paclitaxel, docetaxel, temozolomide, vinorelbine, oral etoposide, gemcitabine, bendamustine, and CAV (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine) (Table 2).

Immunotherapy