User login

FDA gives Orkambi indication for younger patients

(CF), according to its manufacturer, Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Specifically, the drug is meant to treat the most common underlying cause of CF – having two copies of the F508del-CFTR mutation – and is the first drug to treat it.

The approval is based on a phase 3, two-part, open-label, multicenter study that assessed various doses in patents aged 2-5 years. The study demonstrated safety and tolerability in that age group equivalent to that seen in older patients. The drug is expected to be available for this age group within 2-4 weeks of this approval.

Available as oral granules in two doses for weight-based dosing (either lumacaftor 100 mg/ivacaftor 125 mg or lumacaftor 150 mg/ivacaftor 188 mg), the compound targets the defective chloride channels responsible for CF; the two halves work together to increase the number of chloride channels on cell surfaces and also improve their function.

Orkambi should be prescribed only for patients with CF who have the dual F508del-CFTR mutation; it is not indicated for other types of CF. Patients should not take this drug if they are taking drugs such as rifampin, phenytoin, triazolam, or cyclosporine because of possible drug interactions. It can also lead to worsening liver function and elevated blood liver enzymes, increased blood pressure, or cataracts. The most common side effects include breathing problems, nausea, fatigue, and rash. Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

(CF), according to its manufacturer, Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Specifically, the drug is meant to treat the most common underlying cause of CF – having two copies of the F508del-CFTR mutation – and is the first drug to treat it.

The approval is based on a phase 3, two-part, open-label, multicenter study that assessed various doses in patents aged 2-5 years. The study demonstrated safety and tolerability in that age group equivalent to that seen in older patients. The drug is expected to be available for this age group within 2-4 weeks of this approval.

Available as oral granules in two doses for weight-based dosing (either lumacaftor 100 mg/ivacaftor 125 mg or lumacaftor 150 mg/ivacaftor 188 mg), the compound targets the defective chloride channels responsible for CF; the two halves work together to increase the number of chloride channels on cell surfaces and also improve their function.

Orkambi should be prescribed only for patients with CF who have the dual F508del-CFTR mutation; it is not indicated for other types of CF. Patients should not take this drug if they are taking drugs such as rifampin, phenytoin, triazolam, or cyclosporine because of possible drug interactions. It can also lead to worsening liver function and elevated blood liver enzymes, increased blood pressure, or cataracts. The most common side effects include breathing problems, nausea, fatigue, and rash. Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

(CF), according to its manufacturer, Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Specifically, the drug is meant to treat the most common underlying cause of CF – having two copies of the F508del-CFTR mutation – and is the first drug to treat it.

The approval is based on a phase 3, two-part, open-label, multicenter study that assessed various doses in patents aged 2-5 years. The study demonstrated safety and tolerability in that age group equivalent to that seen in older patients. The drug is expected to be available for this age group within 2-4 weeks of this approval.

Available as oral granules in two doses for weight-based dosing (either lumacaftor 100 mg/ivacaftor 125 mg or lumacaftor 150 mg/ivacaftor 188 mg), the compound targets the defective chloride channels responsible for CF; the two halves work together to increase the number of chloride channels on cell surfaces and also improve their function.

Orkambi should be prescribed only for patients with CF who have the dual F508del-CFTR mutation; it is not indicated for other types of CF. Patients should not take this drug if they are taking drugs such as rifampin, phenytoin, triazolam, or cyclosporine because of possible drug interactions. It can also lead to worsening liver function and elevated blood liver enzymes, increased blood pressure, or cataracts. The most common side effects include breathing problems, nausea, fatigue, and rash. Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Hot Topics in Primary Care 2018

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

High Body Mass Index is Related to Increased Perioperative Complications After Periacetabular Osteotomy

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship of body mass index (BMI), age, smoking status, and other comorbid conditions to the rate and type of complications occurring in the perioperative period following periacetabular osteotomy. A retrospective review was performed on 80 hips to determine demographic information as well as pre- and postoperative pain scores, center-edge angle, Tönnis angle, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative complications within 90 days of surgery. Patients were placed into high- (>30) and low- (<30) BMI groups to determine any correlation between complications and BMI. The high-BMI group had a significantly greater rate of perioperative complications than the low-BMI group (30% vs 8%) and, correspondingly, patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). Center-edge angle and Tönnis angle were corrected in both groups. Improvement in postoperative pain scores and radiographically measured acetabular correction can be achieved in high- and low-BMI patients. High-BMI patients have a higher rate of perioperative wound complications.

Continue to: The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy...

The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) has become a widely used procedure for hip preservation in adolescent and young adult patients with symptomatic anatomic aberrancies of the acetabulum due to developmental hip dysplasia, trauma, infection, femoroacetabular impingement, and other causes.1-6 Acetabular dysplasia is one of the most common causes of secondary osteoarthritis, and the goal of PAO is to slow or halt the progression of arthrosis to prolong or potentially eliminate the need for total hip arthroplasty while relieving pain and increasing function and activity.1,7,8

The PAO involves realigning the acetabulum to improve anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head, acetabular anteversion, and medicalization of the joint.5,6 It is preferred over other described acetabular osteotomies due to its inherent stability given that the posterior column is not violated.3,5,6,9 Since its initial description in 1988,5 short-, medium- and long-term outcomes have been reported with excellent patient satisfaction and function.2,7,10-15 The radiographic, functional, and patient satisfaction outcomes are excellent; therefore, this has become an accepted form of treatment for acetabular dysplasia.16 Additional procedures, such as hip arthroscopy, have also been combined with PAO to treat intra-articular pathologies without open arthrotomy.17 Several studies have evaluated preoperative radiographic factors, such as Tönnis grade, previous surgeries, and morphology of the hip; as well as demographic factors, such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbid diseases, and activity level, which seem to play a role in the final outcome.11,18,19 This work has advanced our understanding and allowed surgeons to apply selection criteria to improve patient outcomes.

There are multiple reported complications of the PAO procedure, including infection,2 wound dehiscence,20 periacetabular fracture,21 intra-articular extension of the osteotomy,22 excessive acetabular retroversion,23,24 hardware failure, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy,25 heterotopic ossification, prominent hardware, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism,26 osteonecrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum,24 non-union,24 intrapelvic bleeding,24 incisional hernia,27 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy,20,28 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,2,29 There are also several studies reporting a learning curve phenomenon, in which the proportion of complications is higher in the initial series of surgeries performed by each specific surgeon.22,20,29

Despite the widely reported short-, medium-, and long-term results of this treatment, no study thus far has attempted to correlate preoperative patient factors with early perioperative outcomes and complications. This information would be useful in patient counseling and decision making in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze data from the perioperative period in patients who have undergone the PAO performed by a single surgeon at our institution to determine any correlation between patient characteristics such as age, comorbid disease, hip pathologic diagnosis, BMI, or previous procedures and perioperative complications occurring within the first 90 days.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search was performed on the basis of operative report Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all patients who underwent PAO performed by a single surgeon between 2005 and 2013. Patients were included if they had PAO surgery with at least 90 days of follow-up. There was no exclusion for age, previous surgery, or underlying hip or medical diagnosis. A retrospective review of electronic medical records and radiographic imaging was undertaken to determine pre- and postoperative demographic information, pain scores, center-edge angle of Weiberg and Tönnis angles, intraoperative estimated blood loss, and all perioperative complications. Weight and height were recorded from the immediate preoperative visit and measured in kilograms (kg) and meters (m), respectively. BMI was derived from these measurements. Pain was assessed via visual analog scale at the preoperative visit as well as at 12 weeks postoperatively. Preoperative and 12-week postoperative Tönnis and center-edge angles were measured by a single orthopedic surgeon. All radiographs were deemed adequate in position and penetration for measurement of these parameters. Evidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head was evaluated on all postoperative radiographs within this perioperative period. Estimated blood loss was established by review of operative records and anesthesia notes.

Perioperative complications were classified using the Clavien-Dindo system, which has previously been validated for use in hip preservation surgery.30 This includes 5 grades of complications based on the treatment needed and severity of resulting long-term disability. Grade I complications do not require any change in the postoperative course and were therefore left out of our statistical analysis. Examples include symptomatic hardware, mild heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas tendonitis. Grade II complications are those that require a change in outpatient management, such as delayed wound healing, superficial infection, transient nerve palsy, violation of the posterior column, and intra-articular osteotomy. Grade III complications require invasive or surgical treatment but leave the patient with no long-term disability. Examples include wound dehiscence, hematoma or infection necessitating surgical débridement and irrigation, and revision of the osteotomy due to hardware malposition or hip instability. Grade IV complications involve both surgery and long-term disability. Grade IV complications applicable to hip preservation surgery are osteonecrosis, permanent nerve injury, major vascular injury, or pulmonary embolism. A grade V complication is death.

For analysis and correlation between demographics and perioperative outcomes and complications, patients were grouped into several groups for comparison. Low (<30) vs high (>30) BMI, smokers vs non-smokers, diabetic vs non-diabetic patients, and those who had previous surgery vs those who did not were compared. A two-tailed t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and a Mann-Whitney U test, for non-parametric data to compare postoperative radiographic correction, pain scores, and complication rates between each of these groups.

The operative technique for PAO as described by Ganz and colleagues5 in 1988 was utilized in all patients. When preoperative imaging showed evidence of labral pathology, a Cam lesion of the femoral head and neck junction, abnormal proximal femoral anatomy, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, or an os acetabulum, a concomitant procedure was performed. Seventeen patients underwent débridement of a Cam lesion noted to be impinging following PAO. Seventeen patients underwent labral débridement and 4 underwent labral repair. Four patients underwent intertrochanteric osteotomy and 1 underwent greater trochanteric slide. Two patients underwent free-vascularized fibular grafting to the ipsilateral femoral head and 5 underwent fixation of an os acetabulum.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

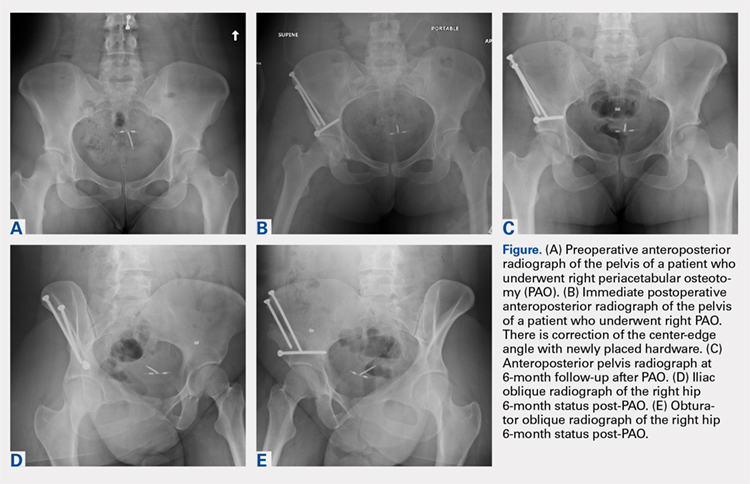

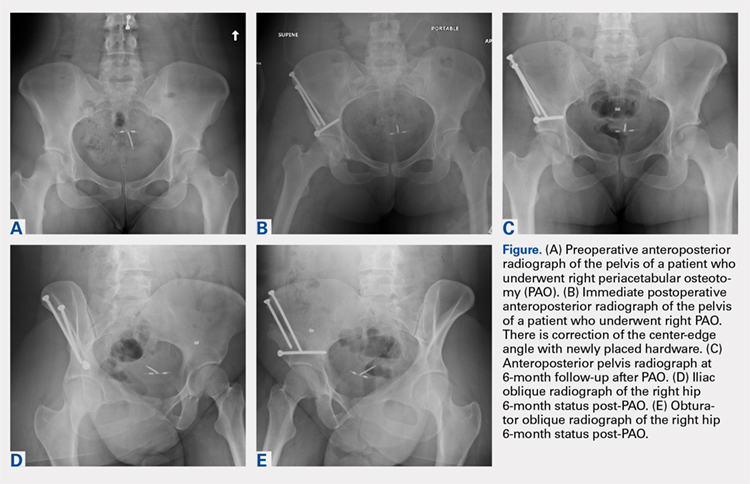

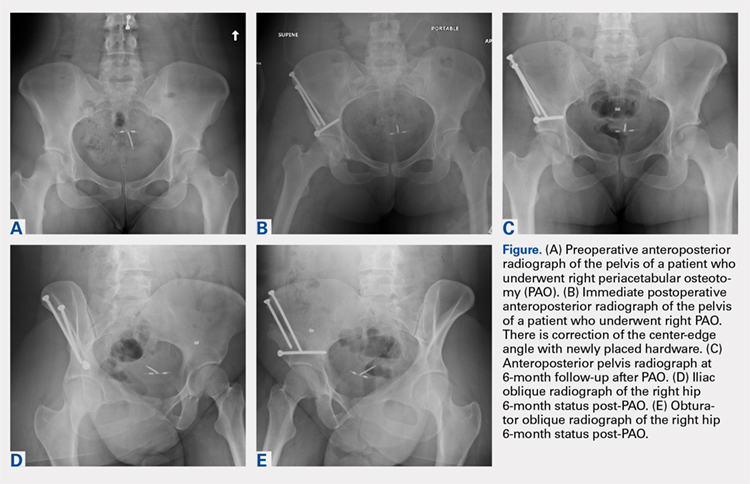

A total of 80 hips in 73 patients underwent PAO with adequate perioperative follow-up and records in the inclusion period. Figures A-E represent a patient pre-procedure, immediately post procedure, and 6 months after successful PAO. The average age was 27.5 years (12.8-43.6 years), and the average BMI was 26.8 (18.7-52.2). Four patients had diabetes, 8 were smokers, and 10 had undergone previous surgeries including arthroscopic labral débridement, 3 open reduction with Salter osteotomy, 3 open reduction with internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture, 1 core decompression for femoral head osteonecrosis, 3 subtrochanteric osteotomy and subsequent non-union treated with cephalomedullary nailing, and 1 previous PAO requiring revision.1

There were 11 perioperative complications in 10 patients (12.5%). The majority of these were infection (n = 10). Overall complications categorized by BMI are summarized in Table 1. Age was similar in patients with complications (27.4 ± 8.8 years) and those without (27.5 ± 8.2 years) (P = .99). Patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9.3 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). There was no effect of concomitant procedures on the complication rate. Of the patients who had complications, 60% (6/10) had concomitant procedures, vs 63% (44/70) of those who had no complications (P = .86) Two of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed complications, both of which were wound infections. One of these required incision and débridement. There were no perioperative complications in any of the 7 smokers.

Table 1. Complications in Low- and High-BMI Patients | ||||

Complications | Total | BMI <30 | BMI >30 | |

Infection | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Superficial | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Deep | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Long screw | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Total | 13 | 5 | 6 | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Twenty hips were in the high-BMI (>30) and 60 were in the low-BMI (<30) patient groups. There were 6 total perioperative complications in the high-BMI group (30%) and 5 in the low-BMI group (8%). The most common complications in the low-BMI group were superficial infections.4 There were 6 total complications in the high-BMI group: 2 deep and 4 superficial infections. There were 3 reoperations (5%) in the low-BMI group during the perioperative period. Two patients underwent successful débridement and irrigation of a superficial wound, and 1 patient required removal of a prominent screw. There were 3 reoperations in the high-BMI group, all of which were débridement and irrigations for wound infections. The rate of wound dehiscence and wound infection was significantly higher in high-BMI patients (30% [6/20]) than in low-BMI patients (8.3% [4/60]) (P = .006). The mean estimated blood loss in the high-BMI group was greater at 923.75 mL vs 779.25 mL in the low-BMI patients; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = .350). Seventy percent (14/20) of patients who were obese had concomitant procedures vs 60% (36/60) of those who had normal BMI (P = .42 by chi-square analysis). There was no difference in estimated blood loss in patients who underwent concomitant procedures (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | |||

| Average EBL | BMI <30 | BMI >30 |

Concomitant procedure | 765 | 759 | 779 |

No concomitant procedure | 900 | 810 | 1263 |

Total | 815 | 779 | 924 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Preoperative pain scores improved from 4.9 (range, 0-10) to 1.9 (range, 0-6) in the high-BMI group and 4.2 (range, 0-10) to 1.2 (range, 0-6) in the low-BMI group (P = .260). The preoperative center-edge angle in the high-BMI group improved from 6.63° ± 6.5° to 28.53° ± 6.7°, and the Tönnis angle from 24.96° ± 6.3° to 10.06° ± 7.7°. In the low-BMI group the center-edge angle improved from 10.53° ± 11.77° to 27.07° ± 13.9°, and the Tönnis angle from 19.00° ± 10.3° to 2.79° ± 8.3°. There was no difference in postoperative center-edge angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .66). There was a trend toward significance in the postoperative Tönnis angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .051).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

There have been 4 previously published articles specifically on complications following PAO. Each of these encompassed follow-up visits including both the perioperative period and at least 2 years of follow-up.20,22,24,29 Davey and Santore29 reported an overall rate of complications of 10% in a series of 70 patients. These authors classified complications into minor, moderate, and major for purposes of research and discussion, and this classification system has been utilized or modified within the literature to discuss complications in most other articles. Complications within the perioperative period included 2 cases of excessive intraoperative bleeding, 2 cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and 1 case each of unresolved sciatic nerve palsy and deep vein thrombosis.29 Hussell and colleagues22 reported on a large series of 508 PAOs and analyzed the technical complications that occurred during the procedure and caused either immediate or longer-term problems for the patients. Notably, they concluded that 85% of the technical complications occurred with the initial 50 PAOs performed, signifying a steep learning curve for this technically demanding procedure. Perioperative complications reported were intra-articular osteotomy in 2.2%, femoral nerve palsy in 0.6%, sciatic nerve palsy in 1.0%, posterior column insufficiency in 1.2%, and symptomatic hardware in 3.0%.22 Biedermann and colleagues20 found that 47 out of 60 PAOs in their series had at least 1 minor complication. The most common perioperative complications were lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysesthesia in 33%, delayed wound healing infection in 15%, major blood loss in 8.3%, sciatic or peroneal nerve palsy in 10%, posterior column discontinuity in 6.7%, and intra-articular osteotomy in 1.6%.20 Most recently, complications of PAO in an adolescent population were evaluated.24 The overall rate of complications was 37%. Major perioperative complications included 1 patient with excessive bleeding due to an aberrant artery at the medial wall of the pelvis thought to be due to revascularization following a previous Dega osteotomy. Two patients required immediate revision of the osteotomy due to excessive anterior coverage noted on postoperative radiographs. There were 5% with superficial stitch abscess causing minor infection, 5% with transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, and 15 patients with symptomatic hardware.24

At 12.5%, our overall complication rate is slightly lower than that previously reported in the literature. This may be due to the difference in the scope of this study, which reported only perioperative complications. We also chose to utilize the modified Clavien-Dindo classification system for reporting our complications rather than classifying them as minor or major as in the above studies. This classification system has been validated for use in reporting complications of hip preservation surgery. We considered only Grade II complications and higher for statistical analysis as these required a change in postoperative management, which may have artificially lowered our complication rate.

The data in this study indicate that, compared with patients with a BMI of <30, obese patients have a higher rate of perioperative complications and reoperations. Additionally, the proportion of Grade II and higher complications, importantly deep infection, was higher in obese patients. We did not have any reported incidence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, intra-articular osteotomy, acetabular or pelvic fracture, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy, or long-term lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy in this series of patients. The most common complication in the low-BMI group was symptomatic hardware. Sixteen patients had this complaint; however, this was not considered a Grade II complication as there would be no change in management during the study period, including the perioperative time frame. Two out of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed wound infections, both of which required reoperation. However, the number of patients with diabetes mellitus was not large enough to draw any conclusions from this information. There were no perioperative complications in smokers. We hypothesized that there may be a higher rate of wound complications in this population, and although the data in our patients did not support this hypothesis, a larger cohort of smokers is needed to make this determination. Another potential complication in smokers is non-union, which was not reported in this study on perioperative complications. Although it did not reach statistical significance, the intraoperative blood loss was almost 150 mL greater in high-BMI patients (924 mL vs 779 mL). Additionally, there appears to be no effect of concomitant procedure on estimated blood loss in either low- or high-BMI groups. Age was not a risk factor for the development of perioperative complications in this cohort. Pain was reliably improved in both the high- and low-BMI groups at the 12-week follow-up visit. The center-edge angle could be normalized in both groups to 28.53° in the high-BMI group and 27.07° in the low-BMI group, with a similar final correction between groups. The Tönnis angle was also improved in both groups, but the final Tönnis angle strongly trended toward statistical significance (2.79° in the low-BMI group vs 10.06° in the high-BMI group).

This study has limitations in that it is a retrospective review of patient information based on medical records and therefore relied on documentation performed at the time of service. There also may have been a difference in the intraoperative or postoperative protocol for wound monitoring or rehabilitation among patients based on body habitus, which we are not able to detect from the medical records. Although the overall number of patients in this cohort is comparable to other studies on the outcomes of patients after PAO, the number of patients in each BMI group was not evenly matched. Without randomization, selection bias occurred at the time of the procedure as some obese patients were not offered this procedure based on the senior surgeon’s discretion. Additionally, when subgroups such as patients with diabetes mellitus or smokers were analyzed, the number of subjects was too small for statistical analysis; therefore, no conclusions could be made as to the risk of perioperative complications in these populations.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations in this study, based on the data from this cohort, we concluded that the goal of PAO of restoring more normal hip joint anatomy can be achieved in both low- and high-BMI patients. However, patients with a BMI >30 should be counseled on their increased risk of major perioperative complications, specifically wound dehiscence and infection, and the higher likelihood of reoperation for treatment of these complications. Diabetic patients can be counseled that they may have a higher risk of infection as well, but future studies with larger numbers will be needed to confirm this. Patients with low BMI should be counseled about the potential for prominent or symptomatic hardware, which may necessitate removal following osteotomy union.

1. Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):254-259. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00887.

2. Clohisy JC, Schutz AL, St John L, Schoenecker PL, Wright RW. Periacetabular osteotomy: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(8):2041-2052. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0842-6.

3. Gillingham BL, Sanchez AA, Wenger DR. Pelvic osteotomies for the treatment of hip dysplasia in children and young adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(5):325-337. doi:10.5435/00124635-199909000-00005.

4. Siebenrock KA, Schoeniger R, Ganz R. Anterior femoro-acetabular impingement due to acetabular retroversion. Treatment with periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):278-286. doi:10.2106/00004623-200302000-00015.

5. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):26-36. doi:10.1097/00003086-198807000-00006.

6. Tibor LM, Sink EL. Periacetabular osteotomy for hip preservation. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(3):343-357. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2012.05.011.

7. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B6.18805.

8. Novais EN, Heyworth B, Murray K, Johnson VM, Kim YJ, Millis MB. Physical activity level improves after periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of symptomatic hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):981-988. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2578-y.

9. Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 1 Pt 1:65-83. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00887.

10. Badra MI, Anand A, Straight JJ, Sala DA, Ruchelsman DE, Feldman DS. Functional outcome in adult patients following Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Orthopedics 2008;31(1):69. doi:10.3928/01477447-20080101-03.

11. Hartig-Andreasen C, Troelsen A, Thillemann TM, Soballe K. What factors predict failure 4 to 12 years after periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(11):2978-2987. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2386-4.

12. Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, Minami A, Matsuno T. Intermediate to long-term results of periacetabular osteotomy in patients younger and older than forty years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(14):1347-1354. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01059.

13. Matheney T, Kim YJ, Zurakowski D, Matero C, Millis M. Intermediate to long-term results following the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of clinical outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2113-2123. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00143.

14. Pogliacomi F, Stark A, Wallensten R. Periacetabular osteotomy. Good pain relief in symptomatic hip dysplasia, 32 patients followed for 4 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(1):67-74. doi:10.1080/00016470510030346.

15. Zhu J, Chen X, Cui Y, Shen C, Cai G. Mid-term results of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of hip in middle aged patients. Int Orthop. 2013;37(4):589-594. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-1790-z.

16. Lehmann CL, Nepple JJ, Baca G, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Do fluoroscopy and postoperative radiographs correlate for periacetabular osteotomy corrections? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3508-3514. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2483-4.

17. Nakayama H, Fukunishi S, Fukui T, Yoshiya S. Arthroscopic labral repair concomitantly performed with curved periacetabular osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):938-941. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2362-x.

18. Sambandam SN, Hull J, Jiranek WA. Factors predicting the failure of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: a meta-regression analysis. Int Orthop. 2009;33(6):1483-1488. doi:10.1007/s00264-008-0643-7.

19. Yasunaga Y, Yamasaki T, Ochi M. Patient selection criteria for periacetabular osteotomy or rotational acetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3342-3354. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2516-z.

20. Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H. Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):611-617. doi:10.1007/s00264-007-0372-3.

21. Espinosa N, Strassberg J, Belzile EL, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Extraarticular fractures after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1645-1651. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0280-x.

22. Hussell JG, Rodriguez JA, Ganz R. Technical complications of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(363):81-92.

23. Tannast M, Pfander G, Steppacher SD, Mast JW, Ganz R. Total acetabular retroversion following pelvic osteotomy: presentation, management, and outcome. Hip Int. 2013;23 Suppl 9:S14-S26. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000089.

24. Thawrani D, Sucato DJ, Podeszwa DA, DeLaRocha A. Complications associated with the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(8):1707-1714. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00829.

25. Sierra RJ, Beaule P, Zaltz I, Millis MB, Clohisy JC, Trousdale RT; ANCHOR Group. Prevention of nerve injury after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2209-2219. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2409-1.

26. Zaltz I, Beaulé P, Clohisy J, et al. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus following periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93 Suppl 2:62-65. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01769.

27. Burmeister H, Kaiser B, Siebenrock KA, Ganz R. Incisional hernia after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(425):177-179. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000130203.28818.da.

28. Kiyama T, Naito M, Shiramizu K, Shinoda T, Maeyama A. Ischemia of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve during periacetabular osteotomy using Smith-Petersen approach. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10(3):123-126. doi:10.1007/s10195-009-0055-5.

29. Davey JP, Santore RF. Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(363):33-37. doi:10.1097/00003086-199906000-00005.

30. Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, Gilbert JC, Clohisy J; Academic Network for Conservational Hip Outcomes Research Group. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2220-2226. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2343-2.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship of body mass index (BMI), age, smoking status, and other comorbid conditions to the rate and type of complications occurring in the perioperative period following periacetabular osteotomy. A retrospective review was performed on 80 hips to determine demographic information as well as pre- and postoperative pain scores, center-edge angle, Tönnis angle, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative complications within 90 days of surgery. Patients were placed into high- (>30) and low- (<30) BMI groups to determine any correlation between complications and BMI. The high-BMI group had a significantly greater rate of perioperative complications than the low-BMI group (30% vs 8%) and, correspondingly, patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). Center-edge angle and Tönnis angle were corrected in both groups. Improvement in postoperative pain scores and radiographically measured acetabular correction can be achieved in high- and low-BMI patients. High-BMI patients have a higher rate of perioperative wound complications.

Continue to: The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy...

The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) has become a widely used procedure for hip preservation in adolescent and young adult patients with symptomatic anatomic aberrancies of the acetabulum due to developmental hip dysplasia, trauma, infection, femoroacetabular impingement, and other causes.1-6 Acetabular dysplasia is one of the most common causes of secondary osteoarthritis, and the goal of PAO is to slow or halt the progression of arthrosis to prolong or potentially eliminate the need for total hip arthroplasty while relieving pain and increasing function and activity.1,7,8

The PAO involves realigning the acetabulum to improve anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head, acetabular anteversion, and medicalization of the joint.5,6 It is preferred over other described acetabular osteotomies due to its inherent stability given that the posterior column is not violated.3,5,6,9 Since its initial description in 1988,5 short-, medium- and long-term outcomes have been reported with excellent patient satisfaction and function.2,7,10-15 The radiographic, functional, and patient satisfaction outcomes are excellent; therefore, this has become an accepted form of treatment for acetabular dysplasia.16 Additional procedures, such as hip arthroscopy, have also been combined with PAO to treat intra-articular pathologies without open arthrotomy.17 Several studies have evaluated preoperative radiographic factors, such as Tönnis grade, previous surgeries, and morphology of the hip; as well as demographic factors, such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbid diseases, and activity level, which seem to play a role in the final outcome.11,18,19 This work has advanced our understanding and allowed surgeons to apply selection criteria to improve patient outcomes.

There are multiple reported complications of the PAO procedure, including infection,2 wound dehiscence,20 periacetabular fracture,21 intra-articular extension of the osteotomy,22 excessive acetabular retroversion,23,24 hardware failure, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy,25 heterotopic ossification, prominent hardware, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism,26 osteonecrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum,24 non-union,24 intrapelvic bleeding,24 incisional hernia,27 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy,20,28 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,2,29 There are also several studies reporting a learning curve phenomenon, in which the proportion of complications is higher in the initial series of surgeries performed by each specific surgeon.22,20,29

Despite the widely reported short-, medium-, and long-term results of this treatment, no study thus far has attempted to correlate preoperative patient factors with early perioperative outcomes and complications. This information would be useful in patient counseling and decision making in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze data from the perioperative period in patients who have undergone the PAO performed by a single surgeon at our institution to determine any correlation between patient characteristics such as age, comorbid disease, hip pathologic diagnosis, BMI, or previous procedures and perioperative complications occurring within the first 90 days.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search was performed on the basis of operative report Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all patients who underwent PAO performed by a single surgeon between 2005 and 2013. Patients were included if they had PAO surgery with at least 90 days of follow-up. There was no exclusion for age, previous surgery, or underlying hip or medical diagnosis. A retrospective review of electronic medical records and radiographic imaging was undertaken to determine pre- and postoperative demographic information, pain scores, center-edge angle of Weiberg and Tönnis angles, intraoperative estimated blood loss, and all perioperative complications. Weight and height were recorded from the immediate preoperative visit and measured in kilograms (kg) and meters (m), respectively. BMI was derived from these measurements. Pain was assessed via visual analog scale at the preoperative visit as well as at 12 weeks postoperatively. Preoperative and 12-week postoperative Tönnis and center-edge angles were measured by a single orthopedic surgeon. All radiographs were deemed adequate in position and penetration for measurement of these parameters. Evidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head was evaluated on all postoperative radiographs within this perioperative period. Estimated blood loss was established by review of operative records and anesthesia notes.

Perioperative complications were classified using the Clavien-Dindo system, which has previously been validated for use in hip preservation surgery.30 This includes 5 grades of complications based on the treatment needed and severity of resulting long-term disability. Grade I complications do not require any change in the postoperative course and were therefore left out of our statistical analysis. Examples include symptomatic hardware, mild heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas tendonitis. Grade II complications are those that require a change in outpatient management, such as delayed wound healing, superficial infection, transient nerve palsy, violation of the posterior column, and intra-articular osteotomy. Grade III complications require invasive or surgical treatment but leave the patient with no long-term disability. Examples include wound dehiscence, hematoma or infection necessitating surgical débridement and irrigation, and revision of the osteotomy due to hardware malposition or hip instability. Grade IV complications involve both surgery and long-term disability. Grade IV complications applicable to hip preservation surgery are osteonecrosis, permanent nerve injury, major vascular injury, or pulmonary embolism. A grade V complication is death.

For analysis and correlation between demographics and perioperative outcomes and complications, patients were grouped into several groups for comparison. Low (<30) vs high (>30) BMI, smokers vs non-smokers, diabetic vs non-diabetic patients, and those who had previous surgery vs those who did not were compared. A two-tailed t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and a Mann-Whitney U test, for non-parametric data to compare postoperative radiographic correction, pain scores, and complication rates between each of these groups.

The operative technique for PAO as described by Ganz and colleagues5 in 1988 was utilized in all patients. When preoperative imaging showed evidence of labral pathology, a Cam lesion of the femoral head and neck junction, abnormal proximal femoral anatomy, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, or an os acetabulum, a concomitant procedure was performed. Seventeen patients underwent débridement of a Cam lesion noted to be impinging following PAO. Seventeen patients underwent labral débridement and 4 underwent labral repair. Four patients underwent intertrochanteric osteotomy and 1 underwent greater trochanteric slide. Two patients underwent free-vascularized fibular grafting to the ipsilateral femoral head and 5 underwent fixation of an os acetabulum.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

A total of 80 hips in 73 patients underwent PAO with adequate perioperative follow-up and records in the inclusion period. Figures A-E represent a patient pre-procedure, immediately post procedure, and 6 months after successful PAO. The average age was 27.5 years (12.8-43.6 years), and the average BMI was 26.8 (18.7-52.2). Four patients had diabetes, 8 were smokers, and 10 had undergone previous surgeries including arthroscopic labral débridement, 3 open reduction with Salter osteotomy, 3 open reduction with internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture, 1 core decompression for femoral head osteonecrosis, 3 subtrochanteric osteotomy and subsequent non-union treated with cephalomedullary nailing, and 1 previous PAO requiring revision.1

There were 11 perioperative complications in 10 patients (12.5%). The majority of these were infection (n = 10). Overall complications categorized by BMI are summarized in Table 1. Age was similar in patients with complications (27.4 ± 8.8 years) and those without (27.5 ± 8.2 years) (P = .99). Patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9.3 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). There was no effect of concomitant procedures on the complication rate. Of the patients who had complications, 60% (6/10) had concomitant procedures, vs 63% (44/70) of those who had no complications (P = .86) Two of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed complications, both of which were wound infections. One of these required incision and débridement. There were no perioperative complications in any of the 7 smokers.

Table 1. Complications in Low- and High-BMI Patients | ||||

Complications | Total | BMI <30 | BMI >30 | |

Infection | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Superficial | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Deep | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Long screw | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Total | 13 | 5 | 6 | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Twenty hips were in the high-BMI (>30) and 60 were in the low-BMI (<30) patient groups. There were 6 total perioperative complications in the high-BMI group (30%) and 5 in the low-BMI group (8%). The most common complications in the low-BMI group were superficial infections.4 There were 6 total complications in the high-BMI group: 2 deep and 4 superficial infections. There were 3 reoperations (5%) in the low-BMI group during the perioperative period. Two patients underwent successful débridement and irrigation of a superficial wound, and 1 patient required removal of a prominent screw. There were 3 reoperations in the high-BMI group, all of which were débridement and irrigations for wound infections. The rate of wound dehiscence and wound infection was significantly higher in high-BMI patients (30% [6/20]) than in low-BMI patients (8.3% [4/60]) (P = .006). The mean estimated blood loss in the high-BMI group was greater at 923.75 mL vs 779.25 mL in the low-BMI patients; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = .350). Seventy percent (14/20) of patients who were obese had concomitant procedures vs 60% (36/60) of those who had normal BMI (P = .42 by chi-square analysis). There was no difference in estimated blood loss in patients who underwent concomitant procedures (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | |||

| Average EBL | BMI <30 | BMI >30 |

Concomitant procedure | 765 | 759 | 779 |

No concomitant procedure | 900 | 810 | 1263 |

Total | 815 | 779 | 924 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Preoperative pain scores improved from 4.9 (range, 0-10) to 1.9 (range, 0-6) in the high-BMI group and 4.2 (range, 0-10) to 1.2 (range, 0-6) in the low-BMI group (P = .260). The preoperative center-edge angle in the high-BMI group improved from 6.63° ± 6.5° to 28.53° ± 6.7°, and the Tönnis angle from 24.96° ± 6.3° to 10.06° ± 7.7°. In the low-BMI group the center-edge angle improved from 10.53° ± 11.77° to 27.07° ± 13.9°, and the Tönnis angle from 19.00° ± 10.3° to 2.79° ± 8.3°. There was no difference in postoperative center-edge angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .66). There was a trend toward significance in the postoperative Tönnis angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .051).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

There have been 4 previously published articles specifically on complications following PAO. Each of these encompassed follow-up visits including both the perioperative period and at least 2 years of follow-up.20,22,24,29 Davey and Santore29 reported an overall rate of complications of 10% in a series of 70 patients. These authors classified complications into minor, moderate, and major for purposes of research and discussion, and this classification system has been utilized or modified within the literature to discuss complications in most other articles. Complications within the perioperative period included 2 cases of excessive intraoperative bleeding, 2 cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and 1 case each of unresolved sciatic nerve palsy and deep vein thrombosis.29 Hussell and colleagues22 reported on a large series of 508 PAOs and analyzed the technical complications that occurred during the procedure and caused either immediate or longer-term problems for the patients. Notably, they concluded that 85% of the technical complications occurred with the initial 50 PAOs performed, signifying a steep learning curve for this technically demanding procedure. Perioperative complications reported were intra-articular osteotomy in 2.2%, femoral nerve palsy in 0.6%, sciatic nerve palsy in 1.0%, posterior column insufficiency in 1.2%, and symptomatic hardware in 3.0%.22 Biedermann and colleagues20 found that 47 out of 60 PAOs in their series had at least 1 minor complication. The most common perioperative complications were lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysesthesia in 33%, delayed wound healing infection in 15%, major blood loss in 8.3%, sciatic or peroneal nerve palsy in 10%, posterior column discontinuity in 6.7%, and intra-articular osteotomy in 1.6%.20 Most recently, complications of PAO in an adolescent population were evaluated.24 The overall rate of complications was 37%. Major perioperative complications included 1 patient with excessive bleeding due to an aberrant artery at the medial wall of the pelvis thought to be due to revascularization following a previous Dega osteotomy. Two patients required immediate revision of the osteotomy due to excessive anterior coverage noted on postoperative radiographs. There were 5% with superficial stitch abscess causing minor infection, 5% with transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, and 15 patients with symptomatic hardware.24

At 12.5%, our overall complication rate is slightly lower than that previously reported in the literature. This may be due to the difference in the scope of this study, which reported only perioperative complications. We also chose to utilize the modified Clavien-Dindo classification system for reporting our complications rather than classifying them as minor or major as in the above studies. This classification system has been validated for use in reporting complications of hip preservation surgery. We considered only Grade II complications and higher for statistical analysis as these required a change in postoperative management, which may have artificially lowered our complication rate.

The data in this study indicate that, compared with patients with a BMI of <30, obese patients have a higher rate of perioperative complications and reoperations. Additionally, the proportion of Grade II and higher complications, importantly deep infection, was higher in obese patients. We did not have any reported incidence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, intra-articular osteotomy, acetabular or pelvic fracture, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy, or long-term lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy in this series of patients. The most common complication in the low-BMI group was symptomatic hardware. Sixteen patients had this complaint; however, this was not considered a Grade II complication as there would be no change in management during the study period, including the perioperative time frame. Two out of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed wound infections, both of which required reoperation. However, the number of patients with diabetes mellitus was not large enough to draw any conclusions from this information. There were no perioperative complications in smokers. We hypothesized that there may be a higher rate of wound complications in this population, and although the data in our patients did not support this hypothesis, a larger cohort of smokers is needed to make this determination. Another potential complication in smokers is non-union, which was not reported in this study on perioperative complications. Although it did not reach statistical significance, the intraoperative blood loss was almost 150 mL greater in high-BMI patients (924 mL vs 779 mL). Additionally, there appears to be no effect of concomitant procedure on estimated blood loss in either low- or high-BMI groups. Age was not a risk factor for the development of perioperative complications in this cohort. Pain was reliably improved in both the high- and low-BMI groups at the 12-week follow-up visit. The center-edge angle could be normalized in both groups to 28.53° in the high-BMI group and 27.07° in the low-BMI group, with a similar final correction between groups. The Tönnis angle was also improved in both groups, but the final Tönnis angle strongly trended toward statistical significance (2.79° in the low-BMI group vs 10.06° in the high-BMI group).

This study has limitations in that it is a retrospective review of patient information based on medical records and therefore relied on documentation performed at the time of service. There also may have been a difference in the intraoperative or postoperative protocol for wound monitoring or rehabilitation among patients based on body habitus, which we are not able to detect from the medical records. Although the overall number of patients in this cohort is comparable to other studies on the outcomes of patients after PAO, the number of patients in each BMI group was not evenly matched. Without randomization, selection bias occurred at the time of the procedure as some obese patients were not offered this procedure based on the senior surgeon’s discretion. Additionally, when subgroups such as patients with diabetes mellitus or smokers were analyzed, the number of subjects was too small for statistical analysis; therefore, no conclusions could be made as to the risk of perioperative complications in these populations.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations in this study, based on the data from this cohort, we concluded that the goal of PAO of restoring more normal hip joint anatomy can be achieved in both low- and high-BMI patients. However, patients with a BMI >30 should be counseled on their increased risk of major perioperative complications, specifically wound dehiscence and infection, and the higher likelihood of reoperation for treatment of these complications. Diabetic patients can be counseled that they may have a higher risk of infection as well, but future studies with larger numbers will be needed to confirm this. Patients with low BMI should be counseled about the potential for prominent or symptomatic hardware, which may necessitate removal following osteotomy union.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine the relationship of body mass index (BMI), age, smoking status, and other comorbid conditions to the rate and type of complications occurring in the perioperative period following periacetabular osteotomy. A retrospective review was performed on 80 hips to determine demographic information as well as pre- and postoperative pain scores, center-edge angle, Tönnis angle, intraoperative blood loss, and perioperative complications within 90 days of surgery. Patients were placed into high- (>30) and low- (<30) BMI groups to determine any correlation between complications and BMI. The high-BMI group had a significantly greater rate of perioperative complications than the low-BMI group (30% vs 8%) and, correspondingly, patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). Center-edge angle and Tönnis angle were corrected in both groups. Improvement in postoperative pain scores and radiographically measured acetabular correction can be achieved in high- and low-BMI patients. High-BMI patients have a higher rate of perioperative wound complications.

Continue to: The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy...

The Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) has become a widely used procedure for hip preservation in adolescent and young adult patients with symptomatic anatomic aberrancies of the acetabulum due to developmental hip dysplasia, trauma, infection, femoroacetabular impingement, and other causes.1-6 Acetabular dysplasia is one of the most common causes of secondary osteoarthritis, and the goal of PAO is to slow or halt the progression of arthrosis to prolong or potentially eliminate the need for total hip arthroplasty while relieving pain and increasing function and activity.1,7,8

The PAO involves realigning the acetabulum to improve anterior and lateral coverage of the femoral head, acetabular anteversion, and medicalization of the joint.5,6 It is preferred over other described acetabular osteotomies due to its inherent stability given that the posterior column is not violated.3,5,6,9 Since its initial description in 1988,5 short-, medium- and long-term outcomes have been reported with excellent patient satisfaction and function.2,7,10-15 The radiographic, functional, and patient satisfaction outcomes are excellent; therefore, this has become an accepted form of treatment for acetabular dysplasia.16 Additional procedures, such as hip arthroscopy, have also been combined with PAO to treat intra-articular pathologies without open arthrotomy.17 Several studies have evaluated preoperative radiographic factors, such as Tönnis grade, previous surgeries, and morphology of the hip; as well as demographic factors, such as age, body mass index (BMI), comorbid diseases, and activity level, which seem to play a role in the final outcome.11,18,19 This work has advanced our understanding and allowed surgeons to apply selection criteria to improve patient outcomes.

There are multiple reported complications of the PAO procedure, including infection,2 wound dehiscence,20 periacetabular fracture,21 intra-articular extension of the osteotomy,22 excessive acetabular retroversion,23,24 hardware failure, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy,25 heterotopic ossification, prominent hardware, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism,26 osteonecrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum,24 non-union,24 intrapelvic bleeding,24 incisional hernia,27 lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy,20,28 and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.1,2,29 There are also several studies reporting a learning curve phenomenon, in which the proportion of complications is higher in the initial series of surgeries performed by each specific surgeon.22,20,29

Despite the widely reported short-, medium-, and long-term results of this treatment, no study thus far has attempted to correlate preoperative patient factors with early perioperative outcomes and complications. This information would be useful in patient counseling and decision making in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze data from the perioperative period in patients who have undergone the PAO performed by a single surgeon at our institution to determine any correlation between patient characteristics such as age, comorbid disease, hip pathologic diagnosis, BMI, or previous procedures and perioperative complications occurring within the first 90 days.

Continue to: MATERIALS AND METHODS...

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, a search was performed on the basis of operative report Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for all patients who underwent PAO performed by a single surgeon between 2005 and 2013. Patients were included if they had PAO surgery with at least 90 days of follow-up. There was no exclusion for age, previous surgery, or underlying hip or medical diagnosis. A retrospective review of electronic medical records and radiographic imaging was undertaken to determine pre- and postoperative demographic information, pain scores, center-edge angle of Weiberg and Tönnis angles, intraoperative estimated blood loss, and all perioperative complications. Weight and height were recorded from the immediate preoperative visit and measured in kilograms (kg) and meters (m), respectively. BMI was derived from these measurements. Pain was assessed via visual analog scale at the preoperative visit as well as at 12 weeks postoperatively. Preoperative and 12-week postoperative Tönnis and center-edge angles were measured by a single orthopedic surgeon. All radiographs were deemed adequate in position and penetration for measurement of these parameters. Evidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head was evaluated on all postoperative radiographs within this perioperative period. Estimated blood loss was established by review of operative records and anesthesia notes.

Perioperative complications were classified using the Clavien-Dindo system, which has previously been validated for use in hip preservation surgery.30 This includes 5 grades of complications based on the treatment needed and severity of resulting long-term disability. Grade I complications do not require any change in the postoperative course and were therefore left out of our statistical analysis. Examples include symptomatic hardware, mild heterotopic ossification, and iliopsoas tendonitis. Grade II complications are those that require a change in outpatient management, such as delayed wound healing, superficial infection, transient nerve palsy, violation of the posterior column, and intra-articular osteotomy. Grade III complications require invasive or surgical treatment but leave the patient with no long-term disability. Examples include wound dehiscence, hematoma or infection necessitating surgical débridement and irrigation, and revision of the osteotomy due to hardware malposition or hip instability. Grade IV complications involve both surgery and long-term disability. Grade IV complications applicable to hip preservation surgery are osteonecrosis, permanent nerve injury, major vascular injury, or pulmonary embolism. A grade V complication is death.

For analysis and correlation between demographics and perioperative outcomes and complications, patients were grouped into several groups for comparison. Low (<30) vs high (>30) BMI, smokers vs non-smokers, diabetic vs non-diabetic patients, and those who had previous surgery vs those who did not were compared. A two-tailed t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables and a Mann-Whitney U test, for non-parametric data to compare postoperative radiographic correction, pain scores, and complication rates between each of these groups.

The operative technique for PAO as described by Ganz and colleagues5 in 1988 was utilized in all patients. When preoperative imaging showed evidence of labral pathology, a Cam lesion of the femoral head and neck junction, abnormal proximal femoral anatomy, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, or an os acetabulum, a concomitant procedure was performed. Seventeen patients underwent débridement of a Cam lesion noted to be impinging following PAO. Seventeen patients underwent labral débridement and 4 underwent labral repair. Four patients underwent intertrochanteric osteotomy and 1 underwent greater trochanteric slide. Two patients underwent free-vascularized fibular grafting to the ipsilateral femoral head and 5 underwent fixation of an os acetabulum.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

A total of 80 hips in 73 patients underwent PAO with adequate perioperative follow-up and records in the inclusion period. Figures A-E represent a patient pre-procedure, immediately post procedure, and 6 months after successful PAO. The average age was 27.5 years (12.8-43.6 years), and the average BMI was 26.8 (18.7-52.2). Four patients had diabetes, 8 were smokers, and 10 had undergone previous surgeries including arthroscopic labral débridement, 3 open reduction with Salter osteotomy, 3 open reduction with internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture, 1 core decompression for femoral head osteonecrosis, 3 subtrochanteric osteotomy and subsequent non-union treated with cephalomedullary nailing, and 1 previous PAO requiring revision.1

There were 11 perioperative complications in 10 patients (12.5%). The majority of these were infection (n = 10). Overall complications categorized by BMI are summarized in Table 1. Age was similar in patients with complications (27.4 ± 8.8 years) and those without (27.5 ± 8.2 years) (P = .99). Patients with complications had significantly higher BMI than those without (30.9.3 ± 9.5, 26.2 ± 5.6) (P = .03). There was no effect of concomitant procedures on the complication rate. Of the patients who had complications, 60% (6/10) had concomitant procedures, vs 63% (44/70) of those who had no complications (P = .86) Two of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed complications, both of which were wound infections. One of these required incision and débridement. There were no perioperative complications in any of the 7 smokers.

Table 1. Complications in Low- and High-BMI Patients | ||||

Complications | Total | BMI <30 | BMI >30 | |

Infection | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Superficial | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Deep | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Long screw | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Total | 13 | 5 | 6 | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Twenty hips were in the high-BMI (>30) and 60 were in the low-BMI (<30) patient groups. There were 6 total perioperative complications in the high-BMI group (30%) and 5 in the low-BMI group (8%). The most common complications in the low-BMI group were superficial infections.4 There were 6 total complications in the high-BMI group: 2 deep and 4 superficial infections. There were 3 reoperations (5%) in the low-BMI group during the perioperative period. Two patients underwent successful débridement and irrigation of a superficial wound, and 1 patient required removal of a prominent screw. There were 3 reoperations in the high-BMI group, all of which were débridement and irrigations for wound infections. The rate of wound dehiscence and wound infection was significantly higher in high-BMI patients (30% [6/20]) than in low-BMI patients (8.3% [4/60]) (P = .006). The mean estimated blood loss in the high-BMI group was greater at 923.75 mL vs 779.25 mL in the low-BMI patients; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = .350). Seventy percent (14/20) of patients who were obese had concomitant procedures vs 60% (36/60) of those who had normal BMI (P = .42 by chi-square analysis). There was no difference in estimated blood loss in patients who underwent concomitant procedures (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | |||

| Average EBL | BMI <30 | BMI >30 |

Concomitant procedure | 765 | 759 | 779 |

No concomitant procedure | 900 | 810 | 1263 |

Total | 815 | 779 | 924 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EBL, estimated blood loss.

Preoperative pain scores improved from 4.9 (range, 0-10) to 1.9 (range, 0-6) in the high-BMI group and 4.2 (range, 0-10) to 1.2 (range, 0-6) in the low-BMI group (P = .260). The preoperative center-edge angle in the high-BMI group improved from 6.63° ± 6.5° to 28.53° ± 6.7°, and the Tönnis angle from 24.96° ± 6.3° to 10.06° ± 7.7°. In the low-BMI group the center-edge angle improved from 10.53° ± 11.77° to 27.07° ± 13.9°, and the Tönnis angle from 19.00° ± 10.3° to 2.79° ± 8.3°. There was no difference in postoperative center-edge angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .66). There was a trend toward significance in the postoperative Tönnis angle between the high-BMI and low-BMI groups (P = .051).

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

There have been 4 previously published articles specifically on complications following PAO. Each of these encompassed follow-up visits including both the perioperative period and at least 2 years of follow-up.20,22,24,29 Davey and Santore29 reported an overall rate of complications of 10% in a series of 70 patients. These authors classified complications into minor, moderate, and major for purposes of research and discussion, and this classification system has been utilized or modified within the literature to discuss complications in most other articles. Complications within the perioperative period included 2 cases of excessive intraoperative bleeding, 2 cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and 1 case each of unresolved sciatic nerve palsy and deep vein thrombosis.29 Hussell and colleagues22 reported on a large series of 508 PAOs and analyzed the technical complications that occurred during the procedure and caused either immediate or longer-term problems for the patients. Notably, they concluded that 85% of the technical complications occurred with the initial 50 PAOs performed, signifying a steep learning curve for this technically demanding procedure. Perioperative complications reported were intra-articular osteotomy in 2.2%, femoral nerve palsy in 0.6%, sciatic nerve palsy in 1.0%, posterior column insufficiency in 1.2%, and symptomatic hardware in 3.0%.22 Biedermann and colleagues20 found that 47 out of 60 PAOs in their series had at least 1 minor complication. The most common perioperative complications were lateral femoral cutaneous nerve dysesthesia in 33%, delayed wound healing infection in 15%, major blood loss in 8.3%, sciatic or peroneal nerve palsy in 10%, posterior column discontinuity in 6.7%, and intra-articular osteotomy in 1.6%.20 Most recently, complications of PAO in an adolescent population were evaluated.24 The overall rate of complications was 37%. Major perioperative complications included 1 patient with excessive bleeding due to an aberrant artery at the medial wall of the pelvis thought to be due to revascularization following a previous Dega osteotomy. Two patients required immediate revision of the osteotomy due to excessive anterior coverage noted on postoperative radiographs. There were 5% with superficial stitch abscess causing minor infection, 5% with transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, and 15 patients with symptomatic hardware.24

At 12.5%, our overall complication rate is slightly lower than that previously reported in the literature. This may be due to the difference in the scope of this study, which reported only perioperative complications. We also chose to utilize the modified Clavien-Dindo classification system for reporting our complications rather than classifying them as minor or major as in the above studies. This classification system has been validated for use in reporting complications of hip preservation surgery. We considered only Grade II complications and higher for statistical analysis as these required a change in postoperative management, which may have artificially lowered our complication rate.

The data in this study indicate that, compared with patients with a BMI of <30, obese patients have a higher rate of perioperative complications and reoperations. Additionally, the proportion of Grade II and higher complications, importantly deep infection, was higher in obese patients. We did not have any reported incidence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, intra-articular osteotomy, acetabular or pelvic fracture, femoral or sciatic nerve palsy, or long-term lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy in this series of patients. The most common complication in the low-BMI group was symptomatic hardware. Sixteen patients had this complaint; however, this was not considered a Grade II complication as there would be no change in management during the study period, including the perioperative time frame. Two out of 4 patients with diabetes mellitus developed wound infections, both of which required reoperation. However, the number of patients with diabetes mellitus was not large enough to draw any conclusions from this information. There were no perioperative complications in smokers. We hypothesized that there may be a higher rate of wound complications in this population, and although the data in our patients did not support this hypothesis, a larger cohort of smokers is needed to make this determination. Another potential complication in smokers is non-union, which was not reported in this study on perioperative complications. Although it did not reach statistical significance, the intraoperative blood loss was almost 150 mL greater in high-BMI patients (924 mL vs 779 mL). Additionally, there appears to be no effect of concomitant procedure on estimated blood loss in either low- or high-BMI groups. Age was not a risk factor for the development of perioperative complications in this cohort. Pain was reliably improved in both the high- and low-BMI groups at the 12-week follow-up visit. The center-edge angle could be normalized in both groups to 28.53° in the high-BMI group and 27.07° in the low-BMI group, with a similar final correction between groups. The Tönnis angle was also improved in both groups, but the final Tönnis angle strongly trended toward statistical significance (2.79° in the low-BMI group vs 10.06° in the high-BMI group).

This study has limitations in that it is a retrospective review of patient information based on medical records and therefore relied on documentation performed at the time of service. There also may have been a difference in the intraoperative or postoperative protocol for wound monitoring or rehabilitation among patients based on body habitus, which we are not able to detect from the medical records. Although the overall number of patients in this cohort is comparable to other studies on the outcomes of patients after PAO, the number of patients in each BMI group was not evenly matched. Without randomization, selection bias occurred at the time of the procedure as some obese patients were not offered this procedure based on the senior surgeon’s discretion. Additionally, when subgroups such as patients with diabetes mellitus or smokers were analyzed, the number of subjects was too small for statistical analysis; therefore, no conclusions could be made as to the risk of perioperative complications in these populations.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations in this study, based on the data from this cohort, we concluded that the goal of PAO of restoring more normal hip joint anatomy can be achieved in both low- and high-BMI patients. However, patients with a BMI >30 should be counseled on their increased risk of major perioperative complications, specifically wound dehiscence and infection, and the higher likelihood of reoperation for treatment of these complications. Diabetic patients can be counseled that they may have a higher risk of infection as well, but future studies with larger numbers will be needed to confirm this. Patients with low BMI should be counseled about the potential for prominent or symptomatic hardware, which may necessitate removal following osteotomy union.

1. Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):254-259. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00887.

2. Clohisy JC, Schutz AL, St John L, Schoenecker PL, Wright RW. Periacetabular osteotomy: a systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(8):2041-2052. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0842-6.

3. Gillingham BL, Sanchez AA, Wenger DR. Pelvic osteotomies for the treatment of hip dysplasia in children and young adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7(5):325-337. doi:10.5435/00124635-199909000-00005.

4. Siebenrock KA, Schoeniger R, Ganz R. Anterior femoro-acetabular impingement due to acetabular retroversion. Treatment with periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):278-286. doi:10.2106/00004623-200302000-00015.

5. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):26-36. doi:10.1097/00003086-198807000-00006.

6. Tibor LM, Sink EL. Periacetabular osteotomy for hip preservation. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(3):343-357. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2012.05.011.

7. Garras DN, Crowder TT, Olson SA. Medium-term results of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy in the treatment of symptomatic developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(6):721-724. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B6.18805.

8. Novais EN, Heyworth B, Murray K, Johnson VM, Kim YJ, Millis MB. Physical activity level improves after periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of symptomatic hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(3):981-988. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2578-y.