User login

Adults with autism, comorbid depression less likely to get talk therapy

Adults with autism spectrum disorders are less likely to receive individual talk therapy, but when they do, they make use of it more than adults without autism.

Using Medicaid data, Brenna B. Maddox, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues presented the results of a study looking at treatment use by 268 adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and 1,072 without, all of whom had depression or anxiety. They published their results in Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Participants with ASD were less likely than those without ASD to receive either individual talk therapy (57.1% vs. 64.3%, P less than .05) or group talk therapy (0.7% vs. 2.9%, P less than .05). However, among those who did receive talk therapy, people with ASD had a significantly higher monthly mean number of visits than those without ASD (0.64 vs. 0.44, P less than .001).

“As predicted, adults with ASD and anxiety/depression were less likely to receive individual talk therapy, consistent with reports that they often experience difficulty accessing mental health services,” wrote Dr. Maddox and her colleagues.

The authors suggested the increased number of talk therapy visits by adults with ASD could reflect a need for more session time for those patients, compared with those without ASD. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy programs are often adapted to ASD patients by increasing the number of sessions.

“An alternative explanation is that talk therapy in the community is less effective with adults with ASD, who therefore stay in therapy for a longer period in pursuit of greater symptom relief,” the authors wrote.

However, they also commented on the fact that both groups received less than one session a month and that it was unlikely that anxiety and depression symptoms would be well addressed with so few visits. “This finding highlights that the problem of limited access to mental health care is not exclusive to adults with ASD.”

Almost twice as many people with ASD used antipsychotics (39.6% vs. 21.5%, P less than .001) and stimulants (11.9% vs. 6.1%, P less than .001), compared with people without ASD. There were similar numbers of benzodiazepine and antidepressant users in both groups, but people with ASD were prescribed all medication types for a significantly higher number of days per month.

Those with ASD also were more likely to be prescribed different classes of medications at the same time. However, they also were less likely to show substance use.

Dr. Maddox and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, the diagnosis of psychiatric and medical conditions was made using ICD-9 codes, and those conditions were not validated using clinical evaluation.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Maddox BB et al. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.009.

Adults with autism spectrum disorders are less likely to receive individual talk therapy, but when they do, they make use of it more than adults without autism.

Using Medicaid data, Brenna B. Maddox, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues presented the results of a study looking at treatment use by 268 adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and 1,072 without, all of whom had depression or anxiety. They published their results in Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Participants with ASD were less likely than those without ASD to receive either individual talk therapy (57.1% vs. 64.3%, P less than .05) or group talk therapy (0.7% vs. 2.9%, P less than .05). However, among those who did receive talk therapy, people with ASD had a significantly higher monthly mean number of visits than those without ASD (0.64 vs. 0.44, P less than .001).

“As predicted, adults with ASD and anxiety/depression were less likely to receive individual talk therapy, consistent with reports that they often experience difficulty accessing mental health services,” wrote Dr. Maddox and her colleagues.

The authors suggested the increased number of talk therapy visits by adults with ASD could reflect a need for more session time for those patients, compared with those without ASD. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy programs are often adapted to ASD patients by increasing the number of sessions.

“An alternative explanation is that talk therapy in the community is less effective with adults with ASD, who therefore stay in therapy for a longer period in pursuit of greater symptom relief,” the authors wrote.

However, they also commented on the fact that both groups received less than one session a month and that it was unlikely that anxiety and depression symptoms would be well addressed with so few visits. “This finding highlights that the problem of limited access to mental health care is not exclusive to adults with ASD.”

Almost twice as many people with ASD used antipsychotics (39.6% vs. 21.5%, P less than .001) and stimulants (11.9% vs. 6.1%, P less than .001), compared with people without ASD. There were similar numbers of benzodiazepine and antidepressant users in both groups, but people with ASD were prescribed all medication types for a significantly higher number of days per month.

Those with ASD also were more likely to be prescribed different classes of medications at the same time. However, they also were less likely to show substance use.

Dr. Maddox and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, the diagnosis of psychiatric and medical conditions was made using ICD-9 codes, and those conditions were not validated using clinical evaluation.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Maddox BB et al. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.009.

Adults with autism spectrum disorders are less likely to receive individual talk therapy, but when they do, they make use of it more than adults without autism.

Using Medicaid data, Brenna B. Maddox, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues presented the results of a study looking at treatment use by 268 adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and 1,072 without, all of whom had depression or anxiety. They published their results in Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Participants with ASD were less likely than those without ASD to receive either individual talk therapy (57.1% vs. 64.3%, P less than .05) or group talk therapy (0.7% vs. 2.9%, P less than .05). However, among those who did receive talk therapy, people with ASD had a significantly higher monthly mean number of visits than those without ASD (0.64 vs. 0.44, P less than .001).

“As predicted, adults with ASD and anxiety/depression were less likely to receive individual talk therapy, consistent with reports that they often experience difficulty accessing mental health services,” wrote Dr. Maddox and her colleagues.

The authors suggested the increased number of talk therapy visits by adults with ASD could reflect a need for more session time for those patients, compared with those without ASD. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy programs are often adapted to ASD patients by increasing the number of sessions.

“An alternative explanation is that talk therapy in the community is less effective with adults with ASD, who therefore stay in therapy for a longer period in pursuit of greater symptom relief,” the authors wrote.

However, they also commented on the fact that both groups received less than one session a month and that it was unlikely that anxiety and depression symptoms would be well addressed with so few visits. “This finding highlights that the problem of limited access to mental health care is not exclusive to adults with ASD.”

Almost twice as many people with ASD used antipsychotics (39.6% vs. 21.5%, P less than .001) and stimulants (11.9% vs. 6.1%, P less than .001), compared with people without ASD. There were similar numbers of benzodiazepine and antidepressant users in both groups, but people with ASD were prescribed all medication types for a significantly higher number of days per month.

Those with ASD also were more likely to be prescribed different classes of medications at the same time. However, they also were less likely to show substance use.

Dr. Maddox and her colleagues cited several limitations. For example, the diagnosis of psychiatric and medical conditions was made using ICD-9 codes, and those conditions were not validated using clinical evaluation.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Maddox BB et al. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.009.

FROM RESEARCH IN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS

Key clinical point: Therapists may need more session time for adults with autism spectrum disorder.

Major finding: Among adults with autism who experience anxiety and depression, 57.1% received talk therapy, compared with 64.3% of those without autism.

Study details: A study of Medicaid claims data for 268 adults with autism and 1,072 without.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Maddox BB et al. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.03.009.

AD severity linked to S. aureus clonal complex types

A new study offers insight into the over time.

The research “suggests that different CC types might harbor different virulence factors and that the patient’s immune system needs to adjust to this,” concluded the authors of the study, published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

There is a strong association between disease severity and colonization with S. aureus in patients with AD, and as many as 90% are colonized with the microbe but, the authors pointed out, it’s not entirely clear how S. aureus affects the development of AD.

They added that there’s been little research into the possible effects of changes in S. aureus clonal types over time. Still, “new studies indicate that specific clonal types could be linked to specific host phenotypes, illustrating that host-microbe interactions might be important for colonization of AD skin,” they said.

The authors, led by Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, tracked 63 adult patients with AD at Denmark’s Bispebjerg Hospital from 2013-2015 to a 2016-2017 follow-up period. Their mean age was 36 years.

They analyzed bacterial swabs taken from the nose, lesional skin, and nonlesional skin. Of the 63 participants, 47 (75%) were colonized with S. aureus in at least one location when the study began, and 27 of those (57%) were still colonized at follow-up. Of the 16 patients not colonized at baseline, 7 patients (44%) had become colonized by follow-up.

Of the 27 patients who were colonized at both time points, 14 (52%) had no change in CC type.

Those who were colonized at follow-up in at least one of the three sites sampled had more severe disease, with a mean SCORAD – or disease severity score – of 37, compared with those who were not colonized at that time, with a mean SCORAD of 28 (P = .067).

There was a much bigger gap in mean SCORAD score between the 14 patients who had the same CC type at both baseline and follow-up (a mean score of 30), compared with the 11 patients with different CC types at follow-up (a mean score of 47), a statistically significant difference (P = .03). Mean severity scores went up in those who changed CC types and down in those whose CC types remained the same.

The findings “illustrate that colonization changes over time, and also probably reflect the relapsing course of this disease, as colonization likely occurs in relation to worsening of the eczema,” the study authors wrote. They cautioned that “other factors should be taken into considerations as these are known to influence AD severity, including change in treatment regimens, climate, or other disease.”

Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the study. No relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Clausen, ML et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17033.

A new study offers insight into the over time.

The research “suggests that different CC types might harbor different virulence factors and that the patient’s immune system needs to adjust to this,” concluded the authors of the study, published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

There is a strong association between disease severity and colonization with S. aureus in patients with AD, and as many as 90% are colonized with the microbe but, the authors pointed out, it’s not entirely clear how S. aureus affects the development of AD.

They added that there’s been little research into the possible effects of changes in S. aureus clonal types over time. Still, “new studies indicate that specific clonal types could be linked to specific host phenotypes, illustrating that host-microbe interactions might be important for colonization of AD skin,” they said.

The authors, led by Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, tracked 63 adult patients with AD at Denmark’s Bispebjerg Hospital from 2013-2015 to a 2016-2017 follow-up period. Their mean age was 36 years.

They analyzed bacterial swabs taken from the nose, lesional skin, and nonlesional skin. Of the 63 participants, 47 (75%) were colonized with S. aureus in at least one location when the study began, and 27 of those (57%) were still colonized at follow-up. Of the 16 patients not colonized at baseline, 7 patients (44%) had become colonized by follow-up.

Of the 27 patients who were colonized at both time points, 14 (52%) had no change in CC type.

Those who were colonized at follow-up in at least one of the three sites sampled had more severe disease, with a mean SCORAD – or disease severity score – of 37, compared with those who were not colonized at that time, with a mean SCORAD of 28 (P = .067).

There was a much bigger gap in mean SCORAD score between the 14 patients who had the same CC type at both baseline and follow-up (a mean score of 30), compared with the 11 patients with different CC types at follow-up (a mean score of 47), a statistically significant difference (P = .03). Mean severity scores went up in those who changed CC types and down in those whose CC types remained the same.

The findings “illustrate that colonization changes over time, and also probably reflect the relapsing course of this disease, as colonization likely occurs in relation to worsening of the eczema,” the study authors wrote. They cautioned that “other factors should be taken into considerations as these are known to influence AD severity, including change in treatment regimens, climate, or other disease.”

Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the study. No relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Clausen, ML et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17033.

A new study offers insight into the over time.

The research “suggests that different CC types might harbor different virulence factors and that the patient’s immune system needs to adjust to this,” concluded the authors of the study, published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

There is a strong association between disease severity and colonization with S. aureus in patients with AD, and as many as 90% are colonized with the microbe but, the authors pointed out, it’s not entirely clear how S. aureus affects the development of AD.

They added that there’s been little research into the possible effects of changes in S. aureus clonal types over time. Still, “new studies indicate that specific clonal types could be linked to specific host phenotypes, illustrating that host-microbe interactions might be important for colonization of AD skin,” they said.

The authors, led by Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, tracked 63 adult patients with AD at Denmark’s Bispebjerg Hospital from 2013-2015 to a 2016-2017 follow-up period. Their mean age was 36 years.

They analyzed bacterial swabs taken from the nose, lesional skin, and nonlesional skin. Of the 63 participants, 47 (75%) were colonized with S. aureus in at least one location when the study began, and 27 of those (57%) were still colonized at follow-up. Of the 16 patients not colonized at baseline, 7 patients (44%) had become colonized by follow-up.

Of the 27 patients who were colonized at both time points, 14 (52%) had no change in CC type.

Those who were colonized at follow-up in at least one of the three sites sampled had more severe disease, with a mean SCORAD – or disease severity score – of 37, compared with those who were not colonized at that time, with a mean SCORAD of 28 (P = .067).

There was a much bigger gap in mean SCORAD score between the 14 patients who had the same CC type at both baseline and follow-up (a mean score of 30), compared with the 11 patients with different CC types at follow-up (a mean score of 47), a statistically significant difference (P = .03). Mean severity scores went up in those who changed CC types and down in those whose CC types remained the same.

The findings “illustrate that colonization changes over time, and also probably reflect the relapsing course of this disease, as colonization likely occurs in relation to worsening of the eczema,” the study authors wrote. They cautioned that “other factors should be taken into considerations as these are known to influence AD severity, including change in treatment regimens, climate, or other disease.”

Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the study. No relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Clausen, ML et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17033.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Changes in skin colonization of Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex (CC) types in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) over time may be related to relapses.

Major finding: Mean SCORAD among the 14 participants with the same CC type at baseline and follow-up was 30, vs. 47 in the 11 patients with different CC types at follow-up (P = .03).

Study details: The study of 63 adults with AD compared the association of disease severity and colonization with S. aureus, and changes in S. aureus clonal complex types over time.

Disclosures: Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the study. No relevant disclosures were reported.

Source: Clausen ML et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Aug 2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17033.

HIV intervention for drug users also benefits injection partners

A combination intervention that included standard of care antiretroviral therapy (ART), systems navigation, and psychosocial counseling showed success in HIV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID), according to the results of a randomized study in the Lancet.

The intervention patients showed an increase in both the use of ART and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for drug use. In addition, they showed a reduced mortality, compared with standard-of-care controls. The study was carried out in one community site in the Ukraine and two health center sites in Vietnam.

A unique aspect of the study was that each HIV-positive PWID recruited one or more HIV-negative injection partners who were followed throughout the study to determine any change in their HIV status, according to a report by William C. Miller, MD, PhD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and his colleagues.

The study included 502 eligible and enrolled HIV-positive PWID along with 806 eligible and enrolled injection partners. The subjects comprised 85% men, with 65% of the participants between the ages of 30-39 years at time of enrollment. Patients were randomized to the intervention group (25%) or the standard of care–only group (75%).

At 1 year, self-reported ART use was higher among the index participants in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (probability ratio,1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9) and viral suppression also was higher with the intervention group than with standard of care (PR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). In addition, MAT use was higher with the intervention than with standard of care (PR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). Seven HIV infections occurred during the study, all in the injection partners of the standard of care group, with none in the intervention group partners, but the study was not powered to determine if this was a significant difference.

Mortality was lower in the intervention group than in the standard of care group with 5.6 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 2.6-10.6) in the intervention group vs. 12.1 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 9.1-15.6) in the standard of care group (hazard ratio, 0.47; 95% CI 0.22-0.90). Similarly, mortality also was lower among injection partners in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (0.46 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.01-2.6 vs. 2.6 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 1.5-4.1, respectively (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.01-0.84).

“This vanguard study provides evidence that a flexible, scalable intervention increases ART and MAT use and reduced mortality among PWID,” according to the authors. “The intervention might have reduced HIV incidence, but incidence was low in both groups of uninfected partners. This low incidence presents a challenge for any similar future trial assessing transmission and precludes a future randomized controlled trial,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the authors reported no conflicts of interest within the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Miller WC et al. Lancet 2018;392:747-59.

Although the study had unexpectedly low incidences of HIV infection in the standard of care population controls, which made it not powered to find a statistically significant difference in HIV incidence in the two groups, given the results, standard of care may be considered substandard in trials such as these, according to Don C. Des Jarlais, MD, and Huong Thi Duong, MD.

Because of this, “we propose that, when an incident case of HIV is identified, ART [antiretroviral therapy] and MAT [medication-assisted therapy] should be offered immediately, and all reasonable attempts should be made to identify potential sources of transmission and people who might have been infected within the person’s injecting and sexual networks,” in any future trials, “even if supplying ethically acceptable standard of care might make the study extremely expensive,” Dr. Des Jarlais and Dr. Duong wrote.

They pointed out that, because combined prevention and care have ended HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs (PWID) in high-income countries, the same should be the case for low- and middle-income settings, especially as MAT has been shown to be quite effective among these latter groups as well.

“Governments and community-based organizations should now unambiguously commit to the goal of using evidence-based interventions to end HIV epidemics among PWID globally,” Dr. Jarlais and Dr. Duong concluded.

Dr. Des Jarlais of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., and Dr. Duong of Hai Phong (Vietnam) University of Medicine and Pharmacy made their comments in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018;392:714-6) .

Although the study had unexpectedly low incidences of HIV infection in the standard of care population controls, which made it not powered to find a statistically significant difference in HIV incidence in the two groups, given the results, standard of care may be considered substandard in trials such as these, according to Don C. Des Jarlais, MD, and Huong Thi Duong, MD.

Because of this, “we propose that, when an incident case of HIV is identified, ART [antiretroviral therapy] and MAT [medication-assisted therapy] should be offered immediately, and all reasonable attempts should be made to identify potential sources of transmission and people who might have been infected within the person’s injecting and sexual networks,” in any future trials, “even if supplying ethically acceptable standard of care might make the study extremely expensive,” Dr. Des Jarlais and Dr. Duong wrote.

They pointed out that, because combined prevention and care have ended HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs (PWID) in high-income countries, the same should be the case for low- and middle-income settings, especially as MAT has been shown to be quite effective among these latter groups as well.

“Governments and community-based organizations should now unambiguously commit to the goal of using evidence-based interventions to end HIV epidemics among PWID globally,” Dr. Jarlais and Dr. Duong concluded.

Dr. Des Jarlais of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., and Dr. Duong of Hai Phong (Vietnam) University of Medicine and Pharmacy made their comments in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018;392:714-6) .

Although the study had unexpectedly low incidences of HIV infection in the standard of care population controls, which made it not powered to find a statistically significant difference in HIV incidence in the two groups, given the results, standard of care may be considered substandard in trials such as these, according to Don C. Des Jarlais, MD, and Huong Thi Duong, MD.

Because of this, “we propose that, when an incident case of HIV is identified, ART [antiretroviral therapy] and MAT [medication-assisted therapy] should be offered immediately, and all reasonable attempts should be made to identify potential sources of transmission and people who might have been infected within the person’s injecting and sexual networks,” in any future trials, “even if supplying ethically acceptable standard of care might make the study extremely expensive,” Dr. Des Jarlais and Dr. Duong wrote.

They pointed out that, because combined prevention and care have ended HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs (PWID) in high-income countries, the same should be the case for low- and middle-income settings, especially as MAT has been shown to be quite effective among these latter groups as well.

“Governments and community-based organizations should now unambiguously commit to the goal of using evidence-based interventions to end HIV epidemics among PWID globally,” Dr. Jarlais and Dr. Duong concluded.

Dr. Des Jarlais of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., and Dr. Duong of Hai Phong (Vietnam) University of Medicine and Pharmacy made their comments in an accompanying editorial (Lancet 2018;392:714-6) .

A combination intervention that included standard of care antiretroviral therapy (ART), systems navigation, and psychosocial counseling showed success in HIV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID), according to the results of a randomized study in the Lancet.

The intervention patients showed an increase in both the use of ART and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for drug use. In addition, they showed a reduced mortality, compared with standard-of-care controls. The study was carried out in one community site in the Ukraine and two health center sites in Vietnam.

A unique aspect of the study was that each HIV-positive PWID recruited one or more HIV-negative injection partners who were followed throughout the study to determine any change in their HIV status, according to a report by William C. Miller, MD, PhD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and his colleagues.

The study included 502 eligible and enrolled HIV-positive PWID along with 806 eligible and enrolled injection partners. The subjects comprised 85% men, with 65% of the participants between the ages of 30-39 years at time of enrollment. Patients were randomized to the intervention group (25%) or the standard of care–only group (75%).

At 1 year, self-reported ART use was higher among the index participants in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (probability ratio,1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9) and viral suppression also was higher with the intervention group than with standard of care (PR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). In addition, MAT use was higher with the intervention than with standard of care (PR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). Seven HIV infections occurred during the study, all in the injection partners of the standard of care group, with none in the intervention group partners, but the study was not powered to determine if this was a significant difference.

Mortality was lower in the intervention group than in the standard of care group with 5.6 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 2.6-10.6) in the intervention group vs. 12.1 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 9.1-15.6) in the standard of care group (hazard ratio, 0.47; 95% CI 0.22-0.90). Similarly, mortality also was lower among injection partners in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (0.46 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.01-2.6 vs. 2.6 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 1.5-4.1, respectively (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.01-0.84).

“This vanguard study provides evidence that a flexible, scalable intervention increases ART and MAT use and reduced mortality among PWID,” according to the authors. “The intervention might have reduced HIV incidence, but incidence was low in both groups of uninfected partners. This low incidence presents a challenge for any similar future trial assessing transmission and precludes a future randomized controlled trial,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the authors reported no conflicts of interest within the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Miller WC et al. Lancet 2018;392:747-59.

A combination intervention that included standard of care antiretroviral therapy (ART), systems navigation, and psychosocial counseling showed success in HIV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID), according to the results of a randomized study in the Lancet.

The intervention patients showed an increase in both the use of ART and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for drug use. In addition, they showed a reduced mortality, compared with standard-of-care controls. The study was carried out in one community site in the Ukraine and two health center sites in Vietnam.

A unique aspect of the study was that each HIV-positive PWID recruited one or more HIV-negative injection partners who were followed throughout the study to determine any change in their HIV status, according to a report by William C. Miller, MD, PhD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and his colleagues.

The study included 502 eligible and enrolled HIV-positive PWID along with 806 eligible and enrolled injection partners. The subjects comprised 85% men, with 65% of the participants between the ages of 30-39 years at time of enrollment. Patients were randomized to the intervention group (25%) or the standard of care–only group (75%).

At 1 year, self-reported ART use was higher among the index participants in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (probability ratio,1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9) and viral suppression also was higher with the intervention group than with standard of care (PR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). In addition, MAT use was higher with the intervention than with standard of care (PR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). Seven HIV infections occurred during the study, all in the injection partners of the standard of care group, with none in the intervention group partners, but the study was not powered to determine if this was a significant difference.

Mortality was lower in the intervention group than in the standard of care group with 5.6 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 2.6-10.6) in the intervention group vs. 12.1 deaths/100 person-years (95% CI, 9.1-15.6) in the standard of care group (hazard ratio, 0.47; 95% CI 0.22-0.90). Similarly, mortality also was lower among injection partners in the intervention group than in the standard of care group (0.46 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.01-2.6 vs. 2.6 deaths/100 person-years; 95% CI, 1.5-4.1, respectively (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.01-0.84).

“This vanguard study provides evidence that a flexible, scalable intervention increases ART and MAT use and reduced mortality among PWID,” according to the authors. “The intervention might have reduced HIV incidence, but incidence was low in both groups of uninfected partners. This low incidence presents a challenge for any similar future trial assessing transmission and precludes a future randomized controlled trial,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the authors reported no conflicts of interest within the scope of the study.

SOURCE: Miller WC et al. Lancet 2018;392:747-59.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Mortality was lower in the intervention group and among their injection partners, compared with the standard of care group.

Major finding: Seven HIV infections occurred in injection partners of the standard-of-care group, with none in those of the intervention group, although this result was underpowered to detect significance.

Study details: Randomized, controlled vanguard study in 502 index HIV-infected participants and 806 uninfected injection partners in one Ukraine community site and two Vietnam health center sites.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest within the scope of the study.

Source: Miller WC et al. Lancet 2018;392:747-59.

How Is the Colorectal Cancer Control Program Doing?

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma responds to checkpoint inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

FROM CANCER IMMUNOLOGY RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma.

Major finding: Two-thirds of patients (67%) with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma achieved partial or complete remission when treated with immune checkpoint blockade.

Study details: A retrospective study involving nine patients with Kaposi sarcoma treated with either nivolumab or pembrolizumab at the Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) from August 2013 through December 2017.

Disclosures: Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Source: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 Sept 7. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

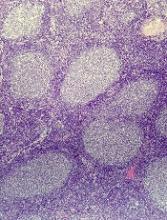

First CAR T-cell therapy approved in Canada

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

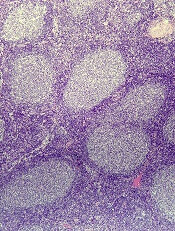

Regimens produce similar results in FL

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

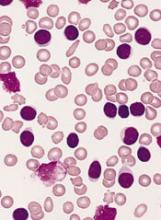

Ibrutinib maintains efficacy over time

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.