User login

Psoriasis & Psoriatic Arthritis - October 2018 Supplement

Psoriasis & Psoriatic Arthritis is a supplement addressing new therapeutic advances and research that will change patient care. “We highlight late-breaking, novel research that will help shape the future of psoriasis therapeutics. Specifically, we discuss psoriasis research that has focused on traditionally overlooked subpopulations,” noted Dr. April W. Armstrong in the supplement’s introduction. Dr. Alan Menter added, “With the introduction of new interleukin (IL)-17 as well as IL-23 biologic drugs for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, as well as IL-17 and IL-23 drugs in the pipeline, we in the field of psoriasis will have an excellent group of quality bio- logic drugs available to us within the next year.

Click here to download this supplement.

Psoriasis & Psoriatic Arthritis is a supplement addressing new therapeutic advances and research that will change patient care. “We highlight late-breaking, novel research that will help shape the future of psoriasis therapeutics. Specifically, we discuss psoriasis research that has focused on traditionally overlooked subpopulations,” noted Dr. April W. Armstrong in the supplement’s introduction. Dr. Alan Menter added, “With the introduction of new interleukin (IL)-17 as well as IL-23 biologic drugs for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, as well as IL-17 and IL-23 drugs in the pipeline, we in the field of psoriasis will have an excellent group of quality bio- logic drugs available to us within the next year.

Click here to download this supplement.

Psoriasis & Psoriatic Arthritis is a supplement addressing new therapeutic advances and research that will change patient care. “We highlight late-breaking, novel research that will help shape the future of psoriasis therapeutics. Specifically, we discuss psoriasis research that has focused on traditionally overlooked subpopulations,” noted Dr. April W. Armstrong in the supplement’s introduction. Dr. Alan Menter added, “With the introduction of new interleukin (IL)-17 as well as IL-23 biologic drugs for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, as well as IL-17 and IL-23 drugs in the pipeline, we in the field of psoriasis will have an excellent group of quality bio- logic drugs available to us within the next year.

Click here to download this supplement.

Opioids don’t treat pain better than ibuprofen after venous ablation surgery

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2018

Key clinical point: Prescribing opioids after venous ablation surgery didn’t improve pain control over ibuprofen.

Major finding:

Study details: Retrospective, single-institution study of 268 patients undergoing venous ablation surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Sacco reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

Recommending HPV vaccination: How would you grade yourself?

A few weeks ago, a patient asked whether he could get my opinion on something unrelated to his yellow fever vaccine visit: He asked what I thought about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. His daughter’s primary care physician (PCP) had recommended it, but he “heard that it wasn’t safe.” We had a brief discussion.

My pediatric training days have long since ended, but I was taught never to miss an opportunity to immunize. In this case, it was to help a parent decide to immunize. This type of encounter is not unusual because, as part of preparing persons for international travel, I review their routine immunizations. When documentation of a vaccine is absent, it is pointed out and often remedied after a brief discussion.

Unfortunately, with HPV, too often parents state “my primary care physician said” it was optional, it was not required, or it was never recommended. Some were told to wait until their child was older, and several have safety concerns as did the parent above. I sometimes hear, “it’s not necessary for my child”; this is usually a clue indicating that the issue is more likely about how HPV is transmitted than what HPV vaccine can prevent. Most have welcomed the opportunity to discuss the vaccine, hear about its benefits, and have their questions answered. All leave with HPV information and are directed to websites that provide accurate information. They are referred to their PCP – hopefully to be immunized.

Three vaccines – meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), Tdap, and HPV vaccine – all are recommended for administration at 11-12 years of age. A booster of MCV is recommended at 16 years. However, let’s focus on HPV. In 2007, HPV administration was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for girls; by 2011, the recommendation was extended to boys. It was a three-dose schedule expected to be completed by age 13 years. In December 2016, a two-dose schedule administered at least 6 months apart was recommended for teens who initiated immunization at less than 15 years. Three doses were still recommended for those initiating HPV after 15 years. This was the only time the number of doses to complete a vaccine series had been decreased based on postlicensure data. So

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually amongst adolescents aged 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from every state, as well as the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2018 Aug 24;67[33]:909-17), HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and MCV in 2018. Among all adolescents, coverage with one or more doses of HPV was 66%, with up-to-date HPV status in 49%. In contrast, 82% received a dose of MCV, and 89% received a dose of Tdap.

Coverage for receiving one or more doses of HPV among females was 69%, and up-to-date HPV status was 53%; among males, coverage with one or more doses was 63%, and up-to-date HPV status was 44%.

Up-to-date HPV coverage status differed geographically, ranging from 29% in Mississippi to 78% in DC. Overall, eight states and the District of Columbia reported increases in up-to-date status (District of Columbia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia). Kudos to Virginia for having the largest increase (20 percentage points).

Coverage also differed between urban and rural areas: one or more doses at 70% vs. 59% and up-to-date status at 52% vs. 42%.

HPV coverage differed by poverty level as well. It was higher for persons living below the poverty level, with one or more doses in 73% and up-to-date status in 54%, compared with persons living at or above poverty level at 63% and 47%, respectively.

HPV-related cancers

The most recent CDC data regarding types of HPV-associated cancers during 2011-2015 suggest that HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical (78%) and oropharyngeal (86%) cancers.

Currently, there are more cases of oropharyngeal cancer than cervical, and we have no screening tool for the former.

Safety

Safety has been well documented. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified, contrary to what has been reported on various social and news media outlets. Yet it remains a concern for many parents who have delayed initiation of vaccine. Efficacy also has been documented in the United States and abroad.

Suggestions for improving HPV immunization coverage

Here are eight suggestions to help you recommend the vaccine and convince hesitant parents of its necessity:

1. Focus on your delivery of the HPV immunization recommendation. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents vaccinate. The tone you use and how you make the recommendation can affect how the parent perceives the importance of this vaccine. The following are components of a high-quality recommendation (Academic Pediatrics. 2018;18:S23-S27):

- Routinely recommend vaccine at 11-12 years.

- Recommend vaccine for all preteens, not just those you feel are at risk for infection.

- Recommend the vaccine be given the same day it is discussed.

- Use language that expresses the importance of the HPV vaccine.

2. Use the “announcement or presumptive approach.” You expect the parent to agree with your recommendation. You don’t want to convey that it is an option.

3. Remind parents that immunizing on time means only two doses of HPV.

4. Revisit the topic again during another visit if a parent declines. Data suggest secondary acceptance can be as high as 66%.

5. Consider using a motivational interviewing approach for parents who are very hesitant to vaccinate. Most people want to comply with recommended health interventions.

6. Educate your staff about the importance of HPV vaccine and how it prevents cancer.

7. Determine how well your practice immunizes adolescents. This would be a perfect quality improvement project.

8. Explore “Answering Parents’ Questions” and other resources at www.cdc.gov/hpv to find quick answers to HPV vaccine–related questions .

Why is HPV coverage, a vaccine to prevent cancer, still lagging behind Tdap and MCV? I am as puzzled as others. What I do know is this: Our children will mature and one day become sexually active. They can be exposed to and get infected with HPV, and we can’t predict which ones will not clear the virus and end up developing an HPV-related cancer in the future. At the end of the day, HPV vaccination is cancer prevention.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A few weeks ago, a patient asked whether he could get my opinion on something unrelated to his yellow fever vaccine visit: He asked what I thought about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. His daughter’s primary care physician (PCP) had recommended it, but he “heard that it wasn’t safe.” We had a brief discussion.

My pediatric training days have long since ended, but I was taught never to miss an opportunity to immunize. In this case, it was to help a parent decide to immunize. This type of encounter is not unusual because, as part of preparing persons for international travel, I review their routine immunizations. When documentation of a vaccine is absent, it is pointed out and often remedied after a brief discussion.

Unfortunately, with HPV, too often parents state “my primary care physician said” it was optional, it was not required, or it was never recommended. Some were told to wait until their child was older, and several have safety concerns as did the parent above. I sometimes hear, “it’s not necessary for my child”; this is usually a clue indicating that the issue is more likely about how HPV is transmitted than what HPV vaccine can prevent. Most have welcomed the opportunity to discuss the vaccine, hear about its benefits, and have their questions answered. All leave with HPV information and are directed to websites that provide accurate information. They are referred to their PCP – hopefully to be immunized.

Three vaccines – meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), Tdap, and HPV vaccine – all are recommended for administration at 11-12 years of age. A booster of MCV is recommended at 16 years. However, let’s focus on HPV. In 2007, HPV administration was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for girls; by 2011, the recommendation was extended to boys. It was a three-dose schedule expected to be completed by age 13 years. In December 2016, a two-dose schedule administered at least 6 months apart was recommended for teens who initiated immunization at less than 15 years. Three doses were still recommended for those initiating HPV after 15 years. This was the only time the number of doses to complete a vaccine series had been decreased based on postlicensure data. So

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually amongst adolescents aged 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from every state, as well as the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2018 Aug 24;67[33]:909-17), HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and MCV in 2018. Among all adolescents, coverage with one or more doses of HPV was 66%, with up-to-date HPV status in 49%. In contrast, 82% received a dose of MCV, and 89% received a dose of Tdap.

Coverage for receiving one or more doses of HPV among females was 69%, and up-to-date HPV status was 53%; among males, coverage with one or more doses was 63%, and up-to-date HPV status was 44%.

Up-to-date HPV coverage status differed geographically, ranging from 29% in Mississippi to 78% in DC. Overall, eight states and the District of Columbia reported increases in up-to-date status (District of Columbia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia). Kudos to Virginia for having the largest increase (20 percentage points).

Coverage also differed between urban and rural areas: one or more doses at 70% vs. 59% and up-to-date status at 52% vs. 42%.

HPV coverage differed by poverty level as well. It was higher for persons living below the poverty level, with one or more doses in 73% and up-to-date status in 54%, compared with persons living at or above poverty level at 63% and 47%, respectively.

HPV-related cancers

The most recent CDC data regarding types of HPV-associated cancers during 2011-2015 suggest that HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical (78%) and oropharyngeal (86%) cancers.

Currently, there are more cases of oropharyngeal cancer than cervical, and we have no screening tool for the former.

Safety

Safety has been well documented. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified, contrary to what has been reported on various social and news media outlets. Yet it remains a concern for many parents who have delayed initiation of vaccine. Efficacy also has been documented in the United States and abroad.

Suggestions for improving HPV immunization coverage

Here are eight suggestions to help you recommend the vaccine and convince hesitant parents of its necessity:

1. Focus on your delivery of the HPV immunization recommendation. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents vaccinate. The tone you use and how you make the recommendation can affect how the parent perceives the importance of this vaccine. The following are components of a high-quality recommendation (Academic Pediatrics. 2018;18:S23-S27):

- Routinely recommend vaccine at 11-12 years.

- Recommend vaccine for all preteens, not just those you feel are at risk for infection.

- Recommend the vaccine be given the same day it is discussed.

- Use language that expresses the importance of the HPV vaccine.

2. Use the “announcement or presumptive approach.” You expect the parent to agree with your recommendation. You don’t want to convey that it is an option.

3. Remind parents that immunizing on time means only two doses of HPV.

4. Revisit the topic again during another visit if a parent declines. Data suggest secondary acceptance can be as high as 66%.

5. Consider using a motivational interviewing approach for parents who are very hesitant to vaccinate. Most people want to comply with recommended health interventions.

6. Educate your staff about the importance of HPV vaccine and how it prevents cancer.

7. Determine how well your practice immunizes adolescents. This would be a perfect quality improvement project.

8. Explore “Answering Parents’ Questions” and other resources at www.cdc.gov/hpv to find quick answers to HPV vaccine–related questions .

Why is HPV coverage, a vaccine to prevent cancer, still lagging behind Tdap and MCV? I am as puzzled as others. What I do know is this: Our children will mature and one day become sexually active. They can be exposed to and get infected with HPV, and we can’t predict which ones will not clear the virus and end up developing an HPV-related cancer in the future. At the end of the day, HPV vaccination is cancer prevention.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A few weeks ago, a patient asked whether he could get my opinion on something unrelated to his yellow fever vaccine visit: He asked what I thought about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. His daughter’s primary care physician (PCP) had recommended it, but he “heard that it wasn’t safe.” We had a brief discussion.

My pediatric training days have long since ended, but I was taught never to miss an opportunity to immunize. In this case, it was to help a parent decide to immunize. This type of encounter is not unusual because, as part of preparing persons for international travel, I review their routine immunizations. When documentation of a vaccine is absent, it is pointed out and often remedied after a brief discussion.

Unfortunately, with HPV, too often parents state “my primary care physician said” it was optional, it was not required, or it was never recommended. Some were told to wait until their child was older, and several have safety concerns as did the parent above. I sometimes hear, “it’s not necessary for my child”; this is usually a clue indicating that the issue is more likely about how HPV is transmitted than what HPV vaccine can prevent. Most have welcomed the opportunity to discuss the vaccine, hear about its benefits, and have their questions answered. All leave with HPV information and are directed to websites that provide accurate information. They are referred to their PCP – hopefully to be immunized.

Three vaccines – meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), Tdap, and HPV vaccine – all are recommended for administration at 11-12 years of age. A booster of MCV is recommended at 16 years. However, let’s focus on HPV. In 2007, HPV administration was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for girls; by 2011, the recommendation was extended to boys. It was a three-dose schedule expected to be completed by age 13 years. In December 2016, a two-dose schedule administered at least 6 months apart was recommended for teens who initiated immunization at less than 15 years. Three doses were still recommended for those initiating HPV after 15 years. This was the only time the number of doses to complete a vaccine series had been decreased based on postlicensure data. So

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually amongst adolescents aged 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from every state, as well as the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2018 Aug 24;67[33]:909-17), HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and MCV in 2018. Among all adolescents, coverage with one or more doses of HPV was 66%, with up-to-date HPV status in 49%. In contrast, 82% received a dose of MCV, and 89% received a dose of Tdap.

Coverage for receiving one or more doses of HPV among females was 69%, and up-to-date HPV status was 53%; among males, coverage with one or more doses was 63%, and up-to-date HPV status was 44%.

Up-to-date HPV coverage status differed geographically, ranging from 29% in Mississippi to 78% in DC. Overall, eight states and the District of Columbia reported increases in up-to-date status (District of Columbia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia). Kudos to Virginia for having the largest increase (20 percentage points).

Coverage also differed between urban and rural areas: one or more doses at 70% vs. 59% and up-to-date status at 52% vs. 42%.

HPV coverage differed by poverty level as well. It was higher for persons living below the poverty level, with one or more doses in 73% and up-to-date status in 54%, compared with persons living at or above poverty level at 63% and 47%, respectively.

HPV-related cancers

The most recent CDC data regarding types of HPV-associated cancers during 2011-2015 suggest that HPV types 16 and 18 account for the majority of cervical (78%) and oropharyngeal (86%) cancers.

Currently, there are more cases of oropharyngeal cancer than cervical, and we have no screening tool for the former.

Safety

Safety has been well documented. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified, contrary to what has been reported on various social and news media outlets. Yet it remains a concern for many parents who have delayed initiation of vaccine. Efficacy also has been documented in the United States and abroad.

Suggestions for improving HPV immunization coverage

Here are eight suggestions to help you recommend the vaccine and convince hesitant parents of its necessity:

1. Focus on your delivery of the HPV immunization recommendation. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents vaccinate. The tone you use and how you make the recommendation can affect how the parent perceives the importance of this vaccine. The following are components of a high-quality recommendation (Academic Pediatrics. 2018;18:S23-S27):

- Routinely recommend vaccine at 11-12 years.

- Recommend vaccine for all preteens, not just those you feel are at risk for infection.

- Recommend the vaccine be given the same day it is discussed.

- Use language that expresses the importance of the HPV vaccine.

2. Use the “announcement or presumptive approach.” You expect the parent to agree with your recommendation. You don’t want to convey that it is an option.

3. Remind parents that immunizing on time means only two doses of HPV.

4. Revisit the topic again during another visit if a parent declines. Data suggest secondary acceptance can be as high as 66%.

5. Consider using a motivational interviewing approach for parents who are very hesitant to vaccinate. Most people want to comply with recommended health interventions.

6. Educate your staff about the importance of HPV vaccine and how it prevents cancer.

7. Determine how well your practice immunizes adolescents. This would be a perfect quality improvement project.

8. Explore “Answering Parents’ Questions” and other resources at www.cdc.gov/hpv to find quick answers to HPV vaccine–related questions .

Why is HPV coverage, a vaccine to prevent cancer, still lagging behind Tdap and MCV? I am as puzzled as others. What I do know is this: Our children will mature and one day become sexually active. They can be exposed to and get infected with HPV, and we can’t predict which ones will not clear the virus and end up developing an HPV-related cancer in the future. At the end of the day, HPV vaccination is cancer prevention.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: Indications and Techniques Across the World

ABSTRACT

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is a common treatment for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. We performed a systematic review of all the RTSA literature to answer if we are treating the same patients with RTSA, across the world.

A systematic review was registered with PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, and performed with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using 3 publicly available free databases. Therapeutic clinical outcome investigations reporting RTSA outcomes with levels of evidence I to IV were eligible for inclusion. All study, subject, and surgical technique demographics were analyzed and compared between continents. Statistical comparisons were conducted using linear regression, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Fisher's exact test, and Pearson's chi-square test.

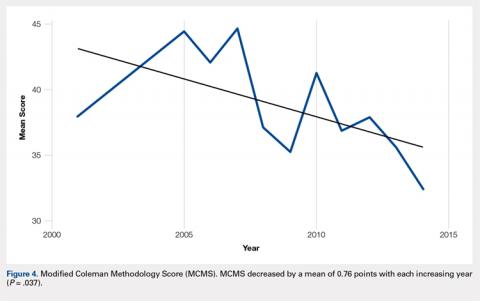

There were 103 studies included in the analysis (8973 patients; 62% female; mean age, 70.9 ± 6.7 years; mean length of follow-up, 34.3 ± 19.3 months) that had a low Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS) (mean, 36.9 ± 8.7: poor). Most patients (60.8%) underwent RTSA for a diagnosis of rotator cuff arthropathy, whereas 1% underwent RTSA for fracture; indications varied by continent. There were no consistent reports of preopeartive or postoperative scores from studies in any region. Studies from North America reported significantly higher postoperative external rotation (34.1° ± 13.3° vs 19.3° ± 8.9°) (P < .001) and a greater change in flexion (69.0° ± 24.5° vs 56.3° ± 11.3°) (P = .004) compared with studies from Europe. North America had the greatest total number of publications followed by Europe. The total yearly number of publications increased each year (P < .001), whereas the MCMS decreased each year (P = .037).

The quantity, but not the quality of RTSA studies is increasing. Indications for RTSA varied by continent, although most patients underwent RTSA for rotator cuff arthropathy. The majority of patients undergoing RTSA are female over the age of 60 years for a diagnosis of rotator cuff arthropathy with pseudoparalysis.

Continue to: Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty...

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is a common procedure with indications including rotator cuff tear arthropathy, proximal humerus fractures, and others.1,2 Studies have shown excellent, reliable, short- and mid-term outcomes in patients treated with RTSA for various indications.3-5 Al-Hadithy and colleagues6 reviewed 41 patients who underwent RTSA for pseudoparalysis secondary to rotator cuff tear arthropathy and, at a mean follow-up of 5 years, found significant improvements in range of motion (ROM) as well as age-adjusted Constant and Oxford Outcome scores. Similarly, Ross and colleagues7 evaluated outcomes of RTSA in 28 patients in whom RTSA was performed for 3- or 4-part proximal humerus fractures, and found both good clinical and radiographic outcomes with no revision surgeries at a mean follow-up of 54.9 months. RTSA is performed across the world, with specific implant designs, specifically humeral head inclination, but is more common in some areas when compared with others.3,8,9

The number of RTSAs performed has steadily increased over the past 20 years, with recent estimates of approximately 20,000 RTSAs performed in the United States in 2011.10,11 However, there is little information about the similarities and differences between those patients undergoing RTSA in various parts of the world regarding surgical indications, patient demographics, and outcomes. The purpose of this study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the RTSA body of literature to both identify and compare characteristics of studies published (level of evidence, whether a conflict of interest existed), patients analyzed (age, gender), and surgical indications performed across both continents and countries. Essentially, the study aims to answer the question, "Across the world, are we treating the same patients?" The authors hypothesized that there would be no significant differences in RTSA publications, subjects, and indications based on both the continent and country of publication.

METHODS

A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.12 A systematic review registration was performed using PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42014010578).13Two reviewers independently conducted the search on March 25, 2014, using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm utilized was: (((((reverse[Title/Abstract]) AND shoulder[Title/Abstract]) AND arthroplasty[Title/Abstract]) NOT arthroscopic[Title/Abstract]) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract]) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract]. English language Level I to IV evidence (2011 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine14) clinical studies were eligible. Medical conference abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references within included studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if missed by the initial search with any additionally located studies screened for inclusion. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice, but rather the study with longer duration follow-up or, if follow-up was equal, the study with the greater number of patients was included. Level V evidence reviews, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical and cadaver studies, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) papers, arthroscopic shoulder surgery papers, imaging, surgical techniques, and classification studies were excluded.

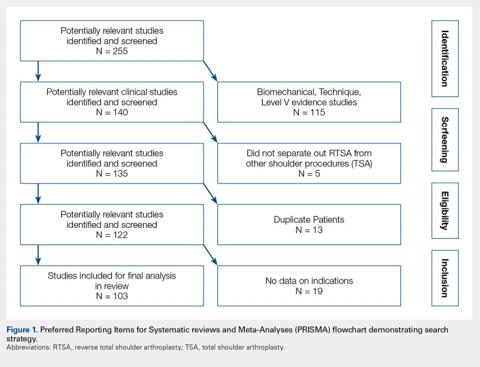

A total of 255 studies were identified, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 103 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Subjects of interest in this systematic review underwent RTSA for one of many indications including rotator cuff tear arthropathy, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, instability, revision from a previous RTSA for instability, infection, acute proximal humerus fracture, revision from a prior proximal humerus fracture, revision from a prior hemiarthroplasty, revision from a prior TSA, osteonecrosis, pseudoparalysis, tumor, and a locked shoulder dislocation. There was no minimum follow-up or rehabilitation requirement. Study and subject demographic parameters analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and shoulders, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, and surgical positioning. Clinical outcome scores sought were the DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index), Absolute Constant, ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Score), KSS (Korean Shoulder Score), SST-12 (Simple Shoulder Test), SF-12 (12-item Short Form), SF-36 (36-item Short Form), SSV (Subjective Shoulder Value), EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Dimension), SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), Rowe Score for Instability, Oxford Instability Score, UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) activity score, Penn Shoulder Score, and VAS (visual analog scale). In addition, ROM (forward elevation, abduction, external rotation, internal rotation) was analyzed. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging data were extracted when available. The methodological quality of the study was evaluated using the MCMS (Modified Coleman Methodology Score).15

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

First, the number of publications per year, level of evidence, and Modified Coleman Methodology Score were tested for association with the calendar year using linear regression. Second, demographic data were tested for association with the continent using Pearson’s chi-square test or ANOVA. Third, indications were tested for association with the continent using Fisher’s exact test. Finally, clinical outcome scores and ROM were tested for association with the continent using ANOVA. Statistical significance was extracted from studies when available. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

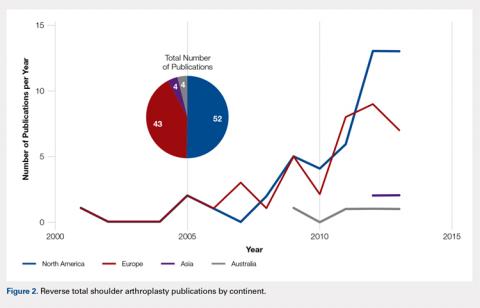

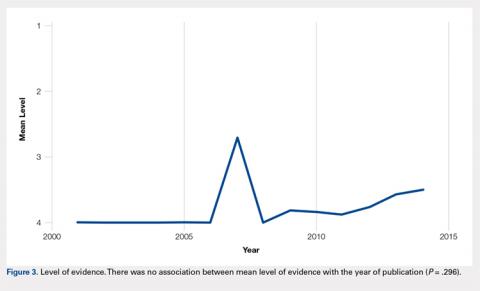

There were 103 studies included in the analysis (Figure 1). A total of 8973 patients were included, 62% of whom were female with a mean age of 70.9 ± 6.7 years (Table 1). The average follow-up was 34.3 ± 19.3 months. North America had the overall greatest total number of publications on RTSA, followed by Europe (Figure 2). The total yearly number of publications increased by a mean of 1.95 publications each year (P < .001). There was no association between the mean level of evidence with the year of publication (P = .296) (Figure 3). Overall, the rating of studies was poor for the MCMS (mean 36.9 ± 8.7). The MCMS decreased each year by a mean of 0.76 points (P = .037) (Figure 4).

Table 1. Demographic Data by Continent

| North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | Total | P-value |

Number of studies | 52 | 43 | 4 | 4 | 103 | - |

Number of subjects | 6158 | 2609 | 51 | 155 | 8973 | - |

Level of evidence |

|

|

|

|

| 0.693 |

II | 5 (10%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (8%) |

|

III | 10 (19%) | 4 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 15 (15%) |

|

IV | 37 (71%) | 36 (84%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 80 (78%) |

|

Mean MCMS | 34.6 ± 8.4 | 40.2 ± 8.0 | 32.5 12.4 | 34.5 ± 6.6 | 36.9 ± 8.7 | 0.010 |

Institutional collaboration |

|

|

|

|

| 1.000 |

Multi-center | 7 (14%) | 6 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (13%) |

|

Single-center | 45 (86%) | 37 (86%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 90 (87%) |

|

Financial conflict of interest |

|

|

|

|

| 0.005 |

Present | 28 (54%) | 15 (35%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 43 (42%) |

|

Not present | 19 (37%) | 16 (37%) | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 43 (42%) |

|

Not reported | 5 (10%) | 12 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 17 (17%) |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

| N/A |

Male | 2157 (38%) | 1026 (39%) | 13 (25%) | 61 (39%) | 3257 (38%) |

|

Female | 3520 (62%) | 1622 (61%) | 38 (75%) | 94 (61%) | 5274 (62%) |

|

Mean age (years) | 71.3 ± 5.6 | 70.1 ± 7.9 | 68.1 ± 5.3 | 76.9 ± 3.0 | 70.9 ± 6.7 | 0.191 |

Minimum age (mean across studies) | 56.9 ± 12.8 | 52.8 ± 15.7 | 62.8 ± 6.2 | 68.0 ± 12.1 | 55.6 ± 14.3 | 0.160 |

Maximum age (mean across studies) | 82.1 ± 8.6 | 83.0 ± 5.5 | 73.0 ± 9.4 | 85.0 ± 7.9 | 82.2 ± 7.6 | 0.079 |

Mean length of follow-up (months) | 26.5 ± 13.7 | 43.1 ± 21.7 | 29.4 ± 7.9 | 34.2 ± 16.6 | 34.3 ± 19.3 | <0.001 |

Prosthesis type |

|

|

|

|

| N/A |

Cemented | 988 (89%) | 969 (72%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (16%) | 1965 (78%) |

|

Press fit | 120 (11%) | 379 (28%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (84%) | 540 (22%) |

|

Abbreviations: MCMS, Modified Coleman Methodology Score; N/A, not available.

In studies that reported press-fit vs cemented prostheses, the highest percentage of press-fit prostheses compared with cemented prostheses was seen in Australia (84% press-fit), whereas the highest percentage of cemented prostheses was seen in North America (89% cemented). A higher percentage of studies from North America had a financial conflict of interest (COI) than did those from other countries (54% had a COI).

Continue to: Rotator cuff tear arthropathy...

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy was the most common indication for RTSA overall in 5459 patients, followed by pseudoparalysis in 1352 patients (Tables 2 and 3). While studies in North America reported rotator cuff tear arthropathy as the indication for RTSA in 4418 (75.8%) patients, and pseudoparalysis as the next most common indication in 535 (9.2%) patients, studies from Europe reported rotator cuff tear arthropathy as the indication in 895 (33.5%) patients, and pseudoparalysis as the indication in 795 (29.7%) patients. Studies from Asia also had a relatively even split between rotator cuff tear arthropathy and pseudoparalysis (45.3% vs 37.8%), whereas those from Australia were mostly rotator cuff tear arthropathy (77.7%).

Table 2. Number (Percent) of Studies With Each Indication by Continent

| North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | Total | P-value |

Rotator cuff arthropathy | 29 (56%) | 19 (44%) | 3 (75%) | 3 (75%) | 54 (52%) | 0.390 |

Osteoarthritis | 4 (8%) | 10 (23%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 16 (16%) | 0.072 |

Rheumatoid arthritis | 9 (17%) | 10 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 21 (20%) | 0.278 |

Post-traumatic arthritis | 3 (6%) | 5 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 9 (9%) | 0.358 |

Instability | 6 (12%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 10 (10%) | 0.450 |

Revision of previous RTSA for instability | 5 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 7 (7%) | 0.192 |

Infection | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) | 0.207 |

Unclassified acute proximal humerus fracture | 9 (17%) | 5 (12%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 16 (16%) | 0.443 |

Acute 2-part proximal humerus fracture | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N/A |

Acute 3-part proximal humerus fracture | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0.574 |

Acute 4-part proximal humerus fracture | 5 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (5%) | 0.183 |

Acute 3- or 4-part proximal humerus fracture | 6 (12%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (8%) | 0.635 |

Revised from previous nonop proximal humerus fracture | 7 (13%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (10%) | 0.787 |

Revised from ORIF | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 1.000 |

Revised from CRPP | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.495 |

Revised from hemi | 8 (15%) | 4 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 13 (13%) | 0.528 |

Revised from TSA | 15 (29%) | 11 (26%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 28 (27%) | 0.492 |

Osteonecrosis | 4 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (7%) | 0.401 |

Pseudoparalysis irreparable tear without arthritis | 20 (38%) | 18 (42%) | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 41 (40%) | 0.919 |

Bone tumors | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (4%) | 0.120 |

Locked shoulder dislocation | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.078 |

Abbreviations: CRPP, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning; ORIF, open reduction internal fixation; RTSA, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

Table 3. Number of Patients With Each Indication as Reported by Individual Studies by Continent

| North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | Total |

Rotator cuff arthropathy | 4418 | 895 | 24 | 122 | 5459 |

Osteoarthritis | 90 | 251 | 1 | 14 | 356 |

Rheumatoid arthritis | 59 | 87 | 0 | 2 | 148 |

Post-traumatic arthritis | 62 | 136 | 0 | 1 | 199 |

Instability | 23 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 39 |

Revision of previous RTSA for instability | 29 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 32 |

Infection | 28 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 41 |

Unclassified acute proximal humerus fracture | 42 | 30 | 4 | 8 | 84 |

Acute 3-part proximal humerus fracture | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

Acute 4-part proximal humerus fracture | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42 |

Acute 3- or 4-part proximal humerus fracture | 92 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 138 |

Revised from previous nonop proximal humerus fracture | 43 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

Revised from ORIF | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

Revised from CRPP | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

Revised from hemi | 105 | 51 | 0 | 1 | 157 |

Revised from TSA | 192 | 246 | 0 | 5 | 443 |

Osteonecrosis | 9 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

Pseudoparalysis irreparable tear without arthritis | 535 | 795 | 20 | 2 | 1352 |

Bone tumors | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 38 |

Locked shoulder dislocation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviations: CRPP, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning; ORIF, open reduction internal fixation; RTSA, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

The ASES, SST-12, and VAS scores were the most frequently reported outcome scores in studies from North America, whereas the Absolute Constant score was the most common score reported in studies from Europe (Table 4). Studies from North America reported significantly higher postoperative external rotation (34.1° ± 13.3° vs 19.3° ± 8.9°) (P < .001) and a greater change in flexion (69.0° ± 24.5° vs 56.3° +/- 11.3°) (P = .004) compared with studies from Europe (Table 5).

Table 4. Outcomes by Continent

Metric (number of studies) | North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | P-value |

DASH | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 54.0 | 62.0 ± 8.5 | - | - | 0.582 |

Postoperative | 24.0 | 32.0 ± 2.8 | - | - | 0.260 |

Change | -30.0 | -30.0 ± 11.3 | - | - | 1.000 |

SPADI | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 80.0 ± 4.2 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 34.8 ± 1.1 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | -45.3 ± 3.2 | - | - | - | N/A |

Absolute constant | 2 | 27 | 0 | 1 |

|

Preopeartive | 33.0 ± 0.0 | 28.2 ± 7.1 | - | 20.0 | 0.329 |

Postoperative | 54.5 ± 7.8 | 62.9 ± 9.0 | - | 65.0 | 0.432 |

Change | +21.5 ± 7.8 | +34.7 ± 8.0 | - | +45.0 | 0.044 |

ASES | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 33.2 ± 5.4 | - | 32.5 ± 3.5 | - | 0.867 |

Postoperative | 73.9 ± 6.8 | - | 75.7 ± 10.8 | - | 0.752 |

Change | +40.7 ± 6.5 | - | +43.2 ± 14.4 | - | 0.670 |

UCLA | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 10.1 ± 3.4 | 11.2 ± 5.7 | 12.0 | - | 0.925 |

Postoperative | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 24.3 ± 3.7 | 24.0 | - | 0.991 |

Change | +14.4 ± 1.6 | +13.1 ± 2.0 | +12.0 | - | 0.524 |

KSS | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

|

Preopeartive | - | - | 38.2 ± 1.1 | - | N/A |

Postoperative | - | - | 72.3 ± 6.0 | - | N/A |

Change | - | - | +34.1 ± 7.1 | - | N/A |

SST-12 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.2 | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 5.6 | - | - | N/A |

Change | +5.3 ± 1.2 | +4.4 | - | - | N/A |

SF-12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 34.5 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 38.5 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | +4.0 | - | - | - | N/A |

SSV | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preopeartive | - | 22.0 ± 7.4 | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | - | 63.4 ± 7.9 | - | - | N/A |

Change | - | +41.4 ± 2.1 | - | - | N/A |

EQ-5D | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | - | 0.5 ± 0.2 | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | - | 0.8 ± 0.1 | - | - | N/A |

Change | - | +0.3 ± 0.1 | - | - | N/A |

OOS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 24.7 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 14.9 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | -9.9 | - | - | - | N/A |

Rowe | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | - | 50.2 | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | - | 82.1 | - | - | N/A |

Change | - | 31.9 | - | - | N/A |

Oxford | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | - | 119.9 ± 138.8 | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | - | 39.9 ± 3.3 | - | - | N/A |

Change | - | -80.6 ± 142.2 | - | - | N/A |

Penn | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 24.9 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 66.4 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | +41.5 | - | - | - | N/A |

VAS | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

Preoperative | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 7.0 | 8.4 | 7.0 | N/A |

Postoperative | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | N/A |

Change | -4.6 ± 0.8 | -6.0 | -7.6 | -6.2 | N/A |

SF-36 physical | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 32.7 ± 1.2 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 39.6 ± 4.0 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | +7.0 ± 2.8 | - | - | - | N/A |

SF-36 mental | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 43.6 ± 2.8 | - | - | - | N/A |

Postoperative | 48.1 ± 1.0 | - | - | - | N/A |

Change | +4.5 ± 1.8 | - | - | - | N/A |

Abbreviations: ASES, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeon score; DASH, Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; KSS, Korean Shoulder Scoring system; N/A, not available; OOS, Orthopaedic Outcome Score; SF, short form; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; SST, Simple Shoulder Test; SSV, Subjective Shoulder Value; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; VAS, visual analog scale.

Table 5. Shoulder Range of Motion, by Continent

Metric (number of studies) | North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | P-value |

Flexion | 18 | 22 | 1 | 1 |

|

Preoperative | 57.6 ± 17.9 | 65.5 ± 17.2 | 91.0 | 30.0 | 0.060 |

Postoperative | 126.6 ± 14.4 | 121.8 ± 19.0 | 133.0 | 150.0 | 0.360 |

Change | +69.0 ± 24.5 | +56.3 ± 11.3 | +42.0 | 120.0 | 0.004 |

Abduction | 11 | 12 | 1 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 53.7 ± 25.0 | 52.0 ± 19.0 | 88.0 | - | 0.311 |

Postoperative | 109.3 ± 15.1 | 105.4 ± 19.8 | 131.0 | - | 0.386 |

Change | 55.5 ± 25.5 | 53.3 ± 8.3 | 43.0 | - | 0.804 |

External rotation | 17 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

|

Preoperative | 19.4 ± 9.9 | 11.2 ± 6.1 | - | - | 0.005 |

Postoperative | 34.1 ± 13.3 | 19.3 ± 8.9 | - | - | <0.001 |

Change | +14.7 ± 13.2 | +8.1 ± 8.5 | - | - | 0.079 |

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

RTSA is a common procedure performed in many different areas of the world for a variety of indications. The study hypotheses were partially confirmed, as there were no significant differences seen in the characteristics of the studies published and patients analyzed; although, the majority of studies from North America reported rotator cuff tear arthropathy as the primary indication for RTSA, whereas studies from Europe were split between rotator cuff tear arthropathy and pseudoparalysis as the primary indication. Hence, based on the current literature the study proved that we are treating the same patients. Despite this finding, we may be treating them for different reasons with an RTSA.

RTSA has become a standard procedure in the United States, with >20,000 RTSAs performed in 2011.10 This number will continue to increase as it has over the past 20 years given the aging population in the United States, as well as the expanding indications for RTSA.11 Indications of RTSA have become broad, although the main indication remains as rotator cuff tear arthropathy (>60% of all patients included in this study), and pseudoparalysis (>15% of all patients included in this study). Results for RTSA for rotator cuff tear arthropathy and pseudoparalysis have been encouraging.16,17 Frankle and colleagues16 evaluated 60 patients who underwent RTSA for rotator cuff tear arthropathy at a minimum of 2 years follow-up (average, 33 months). The authors found significant improvements in all measured clinical outcome variables (P < .0001) (ASES, mean function score, mean pain score, and VAS) as well as ROM, specifically forward flexion increased from 55° to 105.1°, and abduction increased from 41.4° to 101.8°. Similarly, Werner and colleagues17 evaluated 58 consecutive patients who underwent RTSA for pseudoparalysis secondary to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction at a mean follow-up of 38 months. Overall, significant improvements (P < .0001) were seen in the SSV score, relative Constant score, and Constant score for pain, active anterior elevation (42° to 100° following RTSA), and active abduction (43° to 90° following RTSA).

It is essential to understand the similarities and differences between patients undergoing RTSA in different parts of the world so the literature from various countries can be compared between regions, and conclusions extrapolated to the correct patients. For example, an interesting finding in this study is that the majority of patients in North America have their prosthesis cemented whereas the majority of patients in Australia have their prosthesis press-fit. While the patients each continent is treating are not significantly different (mostly older women), the difference in surgical technique could have implications in long- or short-term functional outcomes. Prior studies have shown no difference in axial micromotion between cemented and press-fit humeral components, but the clinical implications surrounding this are not well defined.18 Small series comparing cementless to cemented humeral prosthesis in RTSA have found no significant differences in clinical outcomes or postoperative ROM, but larger series are necessary to validate these outcomes.19 However, studies have shown lower rates of postoperative infections in patients who receive antibiotic-loaded cement compared with those who receive plain bone cement following RTSA.20

Similarly, as the vast majority of patients in North America had an RTSA for rotator cuff arthropathy (75.8%) whereas those from Europe had RTSA almost equally for rotator cuff arthropathy (33.5%) and pseudoparalysis (29.7%), one must ensure similar patient populations before attempting to extrapolate results of a study from a different country to patients in other areas. Fortunately, the clinical results following RTSA for either indication have been good.6,21,22

One final point to consider is the cost effectiveness of the implant. Recent evidence has shown that RTSA is associated with a higher risk for in-hospital death, multiple perioperative complications, prolonged hospital stay, and increased hospital cost when compared with TSA.23 This data may be biased as the patient selection for RTSA varies from that of TSA, but it is a point that must be considered. Other studies have shown that an RTSA is a cost-effective treatment option for treating patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, and is a more cost-effective option in treating rotator cuff tear arthropathy than hemiarthroplasty.24,25 Similarly, RTSA offers a more cost-effective treatment option with better outcomes for patients with acute proximal humerus fractures when compared with open reduction internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty.26 However, TSA is a more cost-effective treatment option than RTSA for patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis.27 With changing reimbursement in healthcare, surgeons must scrutinize not only anticipated outcomes with specific implants but the cost effectiveness of these implants as well. Further cost analysis studies are necessary to determine the ideal candidate for an RTSA.

LIMITATIONS

Despite its extensive review of the literature, this study had several limitations. While 2 independent authors searched for studies, it is possible that some studies were missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. No abstracts or unpublished works were included which could have introduced publication bias. Several studies did not report all variables the authors examined, and this could have skewed some of the results since the reporting of additional variables could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. As outcome measures for various pathologies were not compared, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment option for various indications. As case reports were included, this could have lowered both the MCMS as well as the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, given the overall poor quality of the underlying data available for this study, the validity/generalizability of the results could be limited as the level of evidence of this systematic review is only as high as the studies it includes. There are subtle differences between rotator cuff arthropathy and pseudoparalysis, and some studies may have classified patients differently than others, causing differences in indications. Finally, as the primary goal of this study was to report on demographics, no evaluation of concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols was performed.

CONCLUSION

The quantity, but not the quality of RTSA studies is increasing. Indications for RTSA varied by continent although most patients underwent RTSA for rotator cuff arthropathy. The majority of patients undergoing RTSA are female over the age of 60 years for a diagnosis of rotator cuff arthropathy with pseudoparalysis.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y, O'Shea K. Bony increased-offset reversed shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2558-2567. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1775-4.

2. Gupta AK, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, et al. Surgical management of complex proximal humerus fractures-a systematic review of 92 studies including 4,500 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;29(1):54-59.

3. Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Grammont reversed prosthesis for acute complex fracture of the proximal humerus in an elderly population with 5 to 12 years follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(1):93-97. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2013.12.005.

4. Clark JC, Ritchie J, Song FS, et al. Complication rates, dislocation, pain, and postoperative range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with and without repair of the subscapularis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):36-41. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.009.

5. De Biase CF, Delcogliano M, Borroni M, Castagna A. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: radiological and clinical result using an eccentric glenosphere. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96(suppl 1):S27-SS34. doi:10.1007/s12306-012-0193-4.

6. Al-Hadithy N, Domos P, Sewell MD, Pandit R. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in 41 patients with cuff tear arthropathy with a mean follow-up period of 5 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(11):1662-1668. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.03.001.

7. Ross M, Hope B, Stokes A, Peters SE, McLeod I, Duke PF. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three-part and four-part proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):215-222. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.022.

8. Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544-2556. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00912.

9. Erickson BJ, Frank RM, Harris JD, Mall N, Romeo AA. The influence of humeral head inclination in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):988-993. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.01.001.

10. Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, Craig EV, Gulotta LV. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):91-97. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.026.

11. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01994.

12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

13. University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, National Institute for Health Research. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews. University of York Web site. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed November 1, 2016.

14. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of evidence (March 2009). University of Oxford Web site: https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed November 1, 2016.

15. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderón S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00858.

16. Frankle M, Levy JC, Pupello D, et al. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 1 Pt 2):178-190. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00123.

17. Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1476-1486. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02342.

18. Peppers TA, Jobe CM, Dai QG, Williams PA, Libanati C. Fixation of humeral prostheses and axial micromotion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(4):414-418. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90034-9.

19. Wiater JM, Moravek JE Jr, Budge MD, Koueiter DM, Marcantonio D, Wiater BP. Clinical and radiographic results of cementless reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a comparative study with 2 to 5 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):1208-1214. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.032.

20. Nowinski RJ, Gillespie RJ, Shishani Y, Cohen B, Walch G, Gobezie R. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement reduces deep infection rates for primary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a retrospective, cohort study of 501 shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):324-328. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.072.

21. Favard L, Levigne C, Nerot C, Gerber C, De Wilde L, Mole D. Reverse prostheses in arthropathies with cuff tear: are survivorship and function maintained over time? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2469-2475. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1833-y.

22. Naveed MA, Kitson J, Bunker TD. The Delta III reverse shoulder replacement for cuff tear arthropathy: a single-centre study of 50 consecutive procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):57-61. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24218.

23. Ponce BA, Oladeji LO, Rogers ME, Menendez ME. Comparative analysis of anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: in-hospital outcomes and costs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(3):460-467. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.016.

24. Coe MP, Greiwe RM, Joshi R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1278-1288. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.010.

25. Renfree KJ, Hattrup SJ, Chang YH. Cost utility analysis of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1656-1661. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.08.002.

26. Chalmers PN, Slikker W, 3rd, Mall NA, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fracture: comparison to open reduction-internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):197-204. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.044.

27. Steen BM, Cabezas AF, Santoni BG, et al. Outcome and value of reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a matched cohort. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(9):1433-1441. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.01.005.

ABSTRACT

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is a common treatment for rotator cuff tear arthropathy. We performed a systematic review of all the RTSA literature to answer if we are treating the same patients with RTSA, across the world.

A systematic review was registered with PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, and performed with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using 3 publicly available free databases. Therapeutic clinical outcome investigations reporting RTSA outcomes with levels of evidence I to IV were eligible for inclusion. All study, subject, and surgical technique demographics were analyzed and compared between continents. Statistical comparisons were conducted using linear regression, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Fisher's exact test, and Pearson's chi-square test.

There were 103 studies included in the analysis (8973 patients; 62% female; mean age, 70.9 ± 6.7 years; mean length of follow-up, 34.3 ± 19.3 months) that had a low Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS) (mean, 36.9 ± 8.7: poor). Most patients (60.8%) underwent RTSA for a diagnosis of rotator cuff arthropathy, whereas 1% underwent RTSA for fracture; indications varied by continent. There were no consistent reports of preopeartive or postoperative scores from studies in any region. Studies from North America reported significantly higher postoperative external rotation (34.1° ± 13.3° vs 19.3° ± 8.9°) (P < .001) and a greater change in flexion (69.0° ± 24.5° vs 56.3° ± 11.3°) (P = .004) compared with studies from Europe. North America had the greatest total number of publications followed by Europe. The total yearly number of publications increased each year (P < .001), whereas the MCMS decreased each year (P = .037).

The quantity, but not the quality of RTSA studies is increasing. Indications for RTSA varied by continent, although most patients underwent RTSA for rotator cuff arthropathy. The majority of patients undergoing RTSA are female over the age of 60 years for a diagnosis of rotator cuff arthropathy with pseudoparalysis.

Continue to: Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty...

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) is a common procedure with indications including rotator cuff tear arthropathy, proximal humerus fractures, and others.1,2 Studies have shown excellent, reliable, short- and mid-term outcomes in patients treated with RTSA for various indications.3-5 Al-Hadithy and colleagues6 reviewed 41 patients who underwent RTSA for pseudoparalysis secondary to rotator cuff tear arthropathy and, at a mean follow-up of 5 years, found significant improvements in range of motion (ROM) as well as age-adjusted Constant and Oxford Outcome scores. Similarly, Ross and colleagues7 evaluated outcomes of RTSA in 28 patients in whom RTSA was performed for 3- or 4-part proximal humerus fractures, and found both good clinical and radiographic outcomes with no revision surgeries at a mean follow-up of 54.9 months. RTSA is performed across the world, with specific implant designs, specifically humeral head inclination, but is more common in some areas when compared with others.3,8,9

The number of RTSAs performed has steadily increased over the past 20 years, with recent estimates of approximately 20,000 RTSAs performed in the United States in 2011.10,11 However, there is little information about the similarities and differences between those patients undergoing RTSA in various parts of the world regarding surgical indications, patient demographics, and outcomes. The purpose of this study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of the RTSA body of literature to both identify and compare characteristics of studies published (level of evidence, whether a conflict of interest existed), patients analyzed (age, gender), and surgical indications performed across both continents and countries. Essentially, the study aims to answer the question, "Across the world, are we treating the same patients?" The authors hypothesized that there would be no significant differences in RTSA publications, subjects, and indications based on both the continent and country of publication.

METHODS

A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.12 A systematic review registration was performed using PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42014010578).13Two reviewers independently conducted the search on March 25, 2014, using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm utilized was: (((((reverse[Title/Abstract]) AND shoulder[Title/Abstract]) AND arthroplasty[Title/Abstract]) NOT arthroscopic[Title/Abstract]) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract]) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract]. English language Level I to IV evidence (2011 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine14) clinical studies were eligible. Medical conference abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references within included studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if missed by the initial search with any additionally located studies screened for inclusion. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice, but rather the study with longer duration follow-up or, if follow-up was equal, the study with the greater number of patients was included. Level V evidence reviews, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical and cadaver studies, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) papers, arthroscopic shoulder surgery papers, imaging, surgical techniques, and classification studies were excluded.

A total of 255 studies were identified, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 103 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Subjects of interest in this systematic review underwent RTSA for one of many indications including rotator cuff tear arthropathy, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, instability, revision from a previous RTSA for instability, infection, acute proximal humerus fracture, revision from a prior proximal humerus fracture, revision from a prior hemiarthroplasty, revision from a prior TSA, osteonecrosis, pseudoparalysis, tumor, and a locked shoulder dislocation. There was no minimum follow-up or rehabilitation requirement. Study and subject demographic parameters analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and shoulders, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, and surgical positioning. Clinical outcome scores sought were the DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index), Absolute Constant, ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Score), KSS (Korean Shoulder Score), SST-12 (Simple Shoulder Test), SF-12 (12-item Short Form), SF-36 (36-item Short Form), SSV (Subjective Shoulder Value), EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Dimension), SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), Rowe Score for Instability, Oxford Instability Score, UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) activity score, Penn Shoulder Score, and VAS (visual analog scale). In addition, ROM (forward elevation, abduction, external rotation, internal rotation) was analyzed. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging data were extracted when available. The methodological quality of the study was evaluated using the MCMS (Modified Coleman Methodology Score).15

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

First, the number of publications per year, level of evidence, and Modified Coleman Methodology Score were tested for association with the calendar year using linear regression. Second, demographic data were tested for association with the continent using Pearson’s chi-square test or ANOVA. Third, indications were tested for association with the continent using Fisher’s exact test. Finally, clinical outcome scores and ROM were tested for association with the continent using ANOVA. Statistical significance was extracted from studies when available. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

There were 103 studies included in the analysis (Figure 1). A total of 8973 patients were included, 62% of whom were female with a mean age of 70.9 ± 6.7 years (Table 1). The average follow-up was 34.3 ± 19.3 months. North America had the overall greatest total number of publications on RTSA, followed by Europe (Figure 2). The total yearly number of publications increased by a mean of 1.95 publications each year (P < .001). There was no association between the mean level of evidence with the year of publication (P = .296) (Figure 3). Overall, the rating of studies was poor for the MCMS (mean 36.9 ± 8.7). The MCMS decreased each year by a mean of 0.76 points (P = .037) (Figure 4).

Table 1. Demographic Data by Continent

| North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | Total | P-value |

Number of studies | 52 | 43 | 4 | 4 | 103 | - |

Number of subjects | 6158 | 2609 | 51 | 155 | 8973 | - |

Level of evidence |

|

|

|

|

| 0.693 |

II | 5 (10%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (8%) |

|

III | 10 (19%) | 4 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 15 (15%) |

|

IV | 37 (71%) | 36 (84%) | 4 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 80 (78%) |

|

Mean MCMS | 34.6 ± 8.4 | 40.2 ± 8.0 | 32.5 12.4 | 34.5 ± 6.6 | 36.9 ± 8.7 | 0.010 |

Institutional collaboration |

|

|

|

|

| 1.000 |

Multi-center | 7 (14%) | 6 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (13%) |

|