User login

Childhood inflammatory bowel disease linked to increased mortality

Children who developed inflammatory bowel disease before the age of 18 had a three- to fivefold increase in risk of death, compared with others in a large, retrospective registry study.

The study, which spanned a recent 50-year period, found “no evidence that [these] hazard ratios have changed since the introduction of immunomodulators and biologics,” wrote Ola Olén, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital in Sola, Sweden, together with her associates. Malignancy was the most frequent cause of death among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease, followed by digestive diseases and infections. Absolute numbers of premature deaths were low, but the increase in relative risk was highest among patients with childhood-onset ulcerative colitis with primary sclerosing cholangitis and patients who had a first-degree relative with ulcerative colitis. The findings were published in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

Inflammatory bowel disease is thought to be more severe when it begins in childhood, but data on mortality for these patients are lacking. Using national Swedish health registries, Dr. Olén and her associates compared deaths among 9,442 children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease with those among 93,180 others matched by sex, age, and place of residence. Both groups were typically followed through age 30 years, and the study covered 1964 through 2014.

In all, there were 294 deaths among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease (2.1 deaths per 1,000 person-years) and 940 deaths among matched individuals (0.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years), for a statistically significant adjusted hazard ratio of 3.2 (95% confidence interval, 2.8-3.7). For every 694 patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease who were followed through adulthood, there was one additional death per year, compared with a demographically similar population, the researchers determined.

Among the 294 deaths, 133 were because of cancer. Consequently, individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease had a more than sixfold greater risk of dying from cancer than the general population (HR, 6.6; 95% CI, 5.3-8.2). The risk of death from malignancy was higher among individuals with ulcerative colitis (HR, 9.7) than among those with Crohn’s disease (HR, 3.1). Deaths from conditions of the digestive system were next most common, and these included deaths from liver failure.

In all, 27 individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease died before their 18th birthday, for a fivefold increase in the adjusted hazard of death, compared with the general population of children and adolescents (HR, 4.9; 95% CI, 3.0-7.7). There was no significant trend in hazard of death according to calendar period, either among children and adolescents, or young adults (followed through age 25 years), the researchers said.

Additionally, childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease was associated with a 2.2-year shorter life expectancy in patients followed through age 65 years, they reported. Thus, a diagnosis of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease merits careful follow-up, especially if patients have ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, which was the strongest correlate of fatal intestinal cancer in this study.

Funders included the Swedish Medical Society, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Magtarmfonden, the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation, the Mjölkdroppen Foundation, and the Karolinska Institutet Foundation. Dr. Olén disclosed investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Pfizer. Other investigators also disclosed ties to Janssen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Ferring, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Olén O et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.028.

Children who developed inflammatory bowel disease before the age of 18 had a three- to fivefold increase in risk of death, compared with others in a large, retrospective registry study.

The study, which spanned a recent 50-year period, found “no evidence that [these] hazard ratios have changed since the introduction of immunomodulators and biologics,” wrote Ola Olén, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital in Sola, Sweden, together with her associates. Malignancy was the most frequent cause of death among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease, followed by digestive diseases and infections. Absolute numbers of premature deaths were low, but the increase in relative risk was highest among patients with childhood-onset ulcerative colitis with primary sclerosing cholangitis and patients who had a first-degree relative with ulcerative colitis. The findings were published in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

Inflammatory bowel disease is thought to be more severe when it begins in childhood, but data on mortality for these patients are lacking. Using national Swedish health registries, Dr. Olén and her associates compared deaths among 9,442 children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease with those among 93,180 others matched by sex, age, and place of residence. Both groups were typically followed through age 30 years, and the study covered 1964 through 2014.

In all, there were 294 deaths among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease (2.1 deaths per 1,000 person-years) and 940 deaths among matched individuals (0.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years), for a statistically significant adjusted hazard ratio of 3.2 (95% confidence interval, 2.8-3.7). For every 694 patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease who were followed through adulthood, there was one additional death per year, compared with a demographically similar population, the researchers determined.

Among the 294 deaths, 133 were because of cancer. Consequently, individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease had a more than sixfold greater risk of dying from cancer than the general population (HR, 6.6; 95% CI, 5.3-8.2). The risk of death from malignancy was higher among individuals with ulcerative colitis (HR, 9.7) than among those with Crohn’s disease (HR, 3.1). Deaths from conditions of the digestive system were next most common, and these included deaths from liver failure.

In all, 27 individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease died before their 18th birthday, for a fivefold increase in the adjusted hazard of death, compared with the general population of children and adolescents (HR, 4.9; 95% CI, 3.0-7.7). There was no significant trend in hazard of death according to calendar period, either among children and adolescents, or young adults (followed through age 25 years), the researchers said.

Additionally, childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease was associated with a 2.2-year shorter life expectancy in patients followed through age 65 years, they reported. Thus, a diagnosis of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease merits careful follow-up, especially if patients have ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, which was the strongest correlate of fatal intestinal cancer in this study.

Funders included the Swedish Medical Society, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Magtarmfonden, the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation, the Mjölkdroppen Foundation, and the Karolinska Institutet Foundation. Dr. Olén disclosed investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Pfizer. Other investigators also disclosed ties to Janssen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Ferring, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Olén O et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.028.

Children who developed inflammatory bowel disease before the age of 18 had a three- to fivefold increase in risk of death, compared with others in a large, retrospective registry study.

The study, which spanned a recent 50-year period, found “no evidence that [these] hazard ratios have changed since the introduction of immunomodulators and biologics,” wrote Ola Olén, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital in Sola, Sweden, together with her associates. Malignancy was the most frequent cause of death among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease, followed by digestive diseases and infections. Absolute numbers of premature deaths were low, but the increase in relative risk was highest among patients with childhood-onset ulcerative colitis with primary sclerosing cholangitis and patients who had a first-degree relative with ulcerative colitis. The findings were published in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

Inflammatory bowel disease is thought to be more severe when it begins in childhood, but data on mortality for these patients are lacking. Using national Swedish health registries, Dr. Olén and her associates compared deaths among 9,442 children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease with those among 93,180 others matched by sex, age, and place of residence. Both groups were typically followed through age 30 years, and the study covered 1964 through 2014.

In all, there were 294 deaths among patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease (2.1 deaths per 1,000 person-years) and 940 deaths among matched individuals (0.7 deaths per 1,000 person-years), for a statistically significant adjusted hazard ratio of 3.2 (95% confidence interval, 2.8-3.7). For every 694 patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease who were followed through adulthood, there was one additional death per year, compared with a demographically similar population, the researchers determined.

Among the 294 deaths, 133 were because of cancer. Consequently, individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease had a more than sixfold greater risk of dying from cancer than the general population (HR, 6.6; 95% CI, 5.3-8.2). The risk of death from malignancy was higher among individuals with ulcerative colitis (HR, 9.7) than among those with Crohn’s disease (HR, 3.1). Deaths from conditions of the digestive system were next most common, and these included deaths from liver failure.

In all, 27 individuals with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease died before their 18th birthday, for a fivefold increase in the adjusted hazard of death, compared with the general population of children and adolescents (HR, 4.9; 95% CI, 3.0-7.7). There was no significant trend in hazard of death according to calendar period, either among children and adolescents, or young adults (followed through age 25 years), the researchers said.

Additionally, childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease was associated with a 2.2-year shorter life expectancy in patients followed through age 65 years, they reported. Thus, a diagnosis of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease merits careful follow-up, especially if patients have ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, which was the strongest correlate of fatal intestinal cancer in this study.

Funders included the Swedish Medical Society, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Magtarmfonden, the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation, the Mjölkdroppen Foundation, and the Karolinska Institutet Foundation. Dr. Olén disclosed investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Pfizer. Other investigators also disclosed ties to Janssen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Ferring, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Olén O et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.028.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of death.

Major finding: The risk was approximately threefold higher than in the general population in those with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease aged under 25 years (aHR, 3.2; 95% CI, 2.8-3.7).

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 9,442 patients with childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease and 93,180 individuals from the general population.

Disclosures: Funders included the Swedish Medical Society, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Magtarmfonden, the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundation, the Mjölkdroppen Foundation, and the Karolinska Institutet Foundation. Dr. Olén disclosed investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Pfizer. Other investigators also disclosed ties to Janssen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Ferring, Celgene, and Takeda.

Source: Olén O et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct 17.

Metachronous advanced neoplasia linked to diminutive polyp number, not histology

Among patients with diminutive (1-5 mm) colonic polyps, multiplicity was a significant risk factor for advanced metachronous colonic neoplasia, while advanced histologic features alone were not, according to the results of a pooled analysis of data from 64,344 patients.

Metachronous advanced neoplasia affected similar proportions of patients with and without high-risk diminutive polyps (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively; relative risk, 1.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.61), reported Jasper L.A. Vleugels, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, together with his associates. However, patients with at least three nonadvanced (diminutive or small) adenomas were at significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia, compared with low-risk patients (overall risk ratio, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.89-2.38), the investigators wrote in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

This multicenter study spanned 12 prospectively evaluated cohorts of patients in the United States and Europe. All patients underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test result or for the purpose of screening, surveillance, or evaluation of symptoms. The researchers defined low-risk patients as individuals with one or two diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas. In contrast, “high-risk” patients had a polyp with advanced histology (at least a 25% villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or colonic rectal carcinoma), at least three diminutive (1-5 mm) or small (6-9 mm) nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenomatous or sessile serrated lesion measuring at least 10 mm.

Among more than 50,000 diminutive polyps in the dataset, the prevalence of advanced histologic features was 7.1% among patients who underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test and 1.5% among those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons (P = .04). However, statistically similar proportions of patients in each of these subgroups were classified as “high risk” because of advanced histology (0.8% and 0.4%, respectively) or multiplicity (3.8% and 3.0%, respectively). Because metachronous advanced neoplasia was detected in similar proportions of patients with and without diminutive polyps with advanced histologic features (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively), the presence of such features did not independently predict metachronous advanced neoplasia, either overall (relative risk, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.79-1.61), or in either subgroup.

“On the other hand, multiplicity of diminutive adenomas was associated with increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the researchers wrote. Among these patients, nearly 24% of those in the fecal immunochemical subgroup developed metachronous advanced neoplasia, as did nearly 30% of those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons, yielding risk ratios of 2.45 (95% CI, 1.67-3.58) and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.68-2.20), respectively.

“While multiplicity has been described as a risk factor of metachronous advanced adenomas, we were surprised to find that even if all adenomas are diminutive, the risk was increased,” the investigators commented. Taken together, the findings “underline the importance of correctly classifying diminutive adenomatous lesions, preventing misclassification of patients with at least three adenomas to a low-risk status.”

Partial funding for this study came from PERIS and Fundción Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer. Dr. Vleugels reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Fujifilm, Olympus, Norgine, Clinical Genomics, and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Vleugels J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.050.

When to perform surveillance colonoscopy in patients previously diagnosed with colorectal neoplasms is one of the most significant questions facing experts creating guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. This study by Vleugels et al. provides important information that should better inform this issue.

The authors pooled data from 12 different study cohorts of patients undergoing colonoscopy in either the United States or Europe. The cohorts included patients who underwent colonoscopy to follow up a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or as a primary test for screening, surveillance, or symptom management. The authors found that diminutive adenomas (1-5 mm) rarely contained advanced histology (CRC, high-grade dysplasia, or more than 25% villous features) and that these lesions seldom defined patients regarding risk for metachronous neoplasms. They also found that high-risk patients defined by 1-2 diminutive adenomas with advanced histology were no more likely to develop metachronous advanced neoplasia (adenoma containing advanced histology, at least three diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenoma or sessile serrated lesion at least 10 mm) than were patients defined as low risk by their initial adenoma histology. Interestingly, multiplicity (more than three) of diminutive or small adenomas regardless of histology did predict a significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia. These data support a resect-and-discard strategy (not sending the resected polyp to pathology) for diminutive polyps and polyp surveillance guidelines that employ less frequent colonoscopy to follow patients whose most significant finding at initial colonoscopy is a diminutive adenoma.

Future studies should examine the risk for metachronous neoplasms posed by diminutive adenoma within the milieu of other patient characteristics informing colorectal cancer risk.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor of medicine in the division compliance and a quality expert in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no financial conflicts to disclose.

When to perform surveillance colonoscopy in patients previously diagnosed with colorectal neoplasms is one of the most significant questions facing experts creating guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. This study by Vleugels et al. provides important information that should better inform this issue.

The authors pooled data from 12 different study cohorts of patients undergoing colonoscopy in either the United States or Europe. The cohorts included patients who underwent colonoscopy to follow up a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or as a primary test for screening, surveillance, or symptom management. The authors found that diminutive adenomas (1-5 mm) rarely contained advanced histology (CRC, high-grade dysplasia, or more than 25% villous features) and that these lesions seldom defined patients regarding risk for metachronous neoplasms. They also found that high-risk patients defined by 1-2 diminutive adenomas with advanced histology were no more likely to develop metachronous advanced neoplasia (adenoma containing advanced histology, at least three diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenoma or sessile serrated lesion at least 10 mm) than were patients defined as low risk by their initial adenoma histology. Interestingly, multiplicity (more than three) of diminutive or small adenomas regardless of histology did predict a significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia. These data support a resect-and-discard strategy (not sending the resected polyp to pathology) for diminutive polyps and polyp surveillance guidelines that employ less frequent colonoscopy to follow patients whose most significant finding at initial colonoscopy is a diminutive adenoma.

Future studies should examine the risk for metachronous neoplasms posed by diminutive adenoma within the milieu of other patient characteristics informing colorectal cancer risk.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor of medicine in the division compliance and a quality expert in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no financial conflicts to disclose.

When to perform surveillance colonoscopy in patients previously diagnosed with colorectal neoplasms is one of the most significant questions facing experts creating guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. This study by Vleugels et al. provides important information that should better inform this issue.

The authors pooled data from 12 different study cohorts of patients undergoing colonoscopy in either the United States or Europe. The cohorts included patients who underwent colonoscopy to follow up a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or as a primary test for screening, surveillance, or symptom management. The authors found that diminutive adenomas (1-5 mm) rarely contained advanced histology (CRC, high-grade dysplasia, or more than 25% villous features) and that these lesions seldom defined patients regarding risk for metachronous neoplasms. They also found that high-risk patients defined by 1-2 diminutive adenomas with advanced histology were no more likely to develop metachronous advanced neoplasia (adenoma containing advanced histology, at least three diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenoma or sessile serrated lesion at least 10 mm) than were patients defined as low risk by their initial adenoma histology. Interestingly, multiplicity (more than three) of diminutive or small adenomas regardless of histology did predict a significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia. These data support a resect-and-discard strategy (not sending the resected polyp to pathology) for diminutive polyps and polyp surveillance guidelines that employ less frequent colonoscopy to follow patients whose most significant finding at initial colonoscopy is a diminutive adenoma.

Future studies should examine the risk for metachronous neoplasms posed by diminutive adenoma within the milieu of other patient characteristics informing colorectal cancer risk.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor of medicine in the division compliance and a quality expert in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no financial conflicts to disclose.

Among patients with diminutive (1-5 mm) colonic polyps, multiplicity was a significant risk factor for advanced metachronous colonic neoplasia, while advanced histologic features alone were not, according to the results of a pooled analysis of data from 64,344 patients.

Metachronous advanced neoplasia affected similar proportions of patients with and without high-risk diminutive polyps (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively; relative risk, 1.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.61), reported Jasper L.A. Vleugels, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, together with his associates. However, patients with at least three nonadvanced (diminutive or small) adenomas were at significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia, compared with low-risk patients (overall risk ratio, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.89-2.38), the investigators wrote in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

This multicenter study spanned 12 prospectively evaluated cohorts of patients in the United States and Europe. All patients underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test result or for the purpose of screening, surveillance, or evaluation of symptoms. The researchers defined low-risk patients as individuals with one or two diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas. In contrast, “high-risk” patients had a polyp with advanced histology (at least a 25% villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or colonic rectal carcinoma), at least three diminutive (1-5 mm) or small (6-9 mm) nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenomatous or sessile serrated lesion measuring at least 10 mm.

Among more than 50,000 diminutive polyps in the dataset, the prevalence of advanced histologic features was 7.1% among patients who underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test and 1.5% among those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons (P = .04). However, statistically similar proportions of patients in each of these subgroups were classified as “high risk” because of advanced histology (0.8% and 0.4%, respectively) or multiplicity (3.8% and 3.0%, respectively). Because metachronous advanced neoplasia was detected in similar proportions of patients with and without diminutive polyps with advanced histologic features (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively), the presence of such features did not independently predict metachronous advanced neoplasia, either overall (relative risk, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.79-1.61), or in either subgroup.

“On the other hand, multiplicity of diminutive adenomas was associated with increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the researchers wrote. Among these patients, nearly 24% of those in the fecal immunochemical subgroup developed metachronous advanced neoplasia, as did nearly 30% of those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons, yielding risk ratios of 2.45 (95% CI, 1.67-3.58) and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.68-2.20), respectively.

“While multiplicity has been described as a risk factor of metachronous advanced adenomas, we were surprised to find that even if all adenomas are diminutive, the risk was increased,” the investigators commented. Taken together, the findings “underline the importance of correctly classifying diminutive adenomatous lesions, preventing misclassification of patients with at least three adenomas to a low-risk status.”

Partial funding for this study came from PERIS and Fundción Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer. Dr. Vleugels reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Fujifilm, Olympus, Norgine, Clinical Genomics, and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Vleugels J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.050.

Among patients with diminutive (1-5 mm) colonic polyps, multiplicity was a significant risk factor for advanced metachronous colonic neoplasia, while advanced histologic features alone were not, according to the results of a pooled analysis of data from 64,344 patients.

Metachronous advanced neoplasia affected similar proportions of patients with and without high-risk diminutive polyps (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively; relative risk, 1.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.61), reported Jasper L.A. Vleugels, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, together with his associates. However, patients with at least three nonadvanced (diminutive or small) adenomas were at significantly increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia, compared with low-risk patients (overall risk ratio, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.89-2.38), the investigators wrote in the February issue of Gastroenterology.

This multicenter study spanned 12 prospectively evaluated cohorts of patients in the United States and Europe. All patients underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test result or for the purpose of screening, surveillance, or evaluation of symptoms. The researchers defined low-risk patients as individuals with one or two diminutive or small nonadvanced adenomas. In contrast, “high-risk” patients had a polyp with advanced histology (at least a 25% villous component, high-grade dysplasia, or colonic rectal carcinoma), at least three diminutive (1-5 mm) or small (6-9 mm) nonadvanced adenomas, or an adenomatous or sessile serrated lesion measuring at least 10 mm.

Among more than 50,000 diminutive polyps in the dataset, the prevalence of advanced histologic features was 7.1% among patients who underwent colonoscopy because of a positive fecal immunochemical test and 1.5% among those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons (P = .04). However, statistically similar proportions of patients in each of these subgroups were classified as “high risk” because of advanced histology (0.8% and 0.4%, respectively) or multiplicity (3.8% and 3.0%, respectively). Because metachronous advanced neoplasia was detected in similar proportions of patients with and without diminutive polyps with advanced histologic features (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively), the presence of such features did not independently predict metachronous advanced neoplasia, either overall (relative risk, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.79-1.61), or in either subgroup.

“On the other hand, multiplicity of diminutive adenomas was associated with increased risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the researchers wrote. Among these patients, nearly 24% of those in the fecal immunochemical subgroup developed metachronous advanced neoplasia, as did nearly 30% of those who had a colonoscopy for other reasons, yielding risk ratios of 2.45 (95% CI, 1.67-3.58) and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.68-2.20), respectively.

“While multiplicity has been described as a risk factor of metachronous advanced adenomas, we were surprised to find that even if all adenomas are diminutive, the risk was increased,” the investigators commented. Taken together, the findings “underline the importance of correctly classifying diminutive adenomatous lesions, preventing misclassification of patients with at least three adenomas to a low-risk status.”

Partial funding for this study came from PERIS and Fundción Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer. Dr. Vleugels reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Fujifilm, Olympus, Norgine, Clinical Genomics, and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Vleugels J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.050.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Among patients with diminutive polyps, multiplicity was a significant risk factor for advanced metachronous colonic neoplasia, while high-risk histologic features alone were not.

Major finding: Metachronous advanced neoplasia was found in similar proportions of patients with and without high-risk diminutive polyps (17.6% vs. 14.6%, respectively; relative risk, 1.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-1.61). Having at least three nonadvanced adenomas was, however, a significant correlate of metachronous advanced neoplasia (risk ratio, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.89-2.38).

Study details: Pooled analysis of data from 12 international cohorts (64,344 patients).

Disclosures: Partial funding came from PERIS and Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer. Dr. Vleugels reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to Fujifilm, Olympus, Norgine, Clinical Genomics, and Boston Scientific.

Source: Vleugels J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.050.

Putting up with abusive patients? That’s not for me.

I’ll put up with a lot in this practice, but I will not tolerate mistreatment of my staff.

Rudeness, while never pleasant, is generally tolerated. Some people just have that sort of personality. Others may be having a crappy day for unrelated reasons. We all have those.

But those who are intentionally abusive of my hardworking assistants aren’t going to get very far here. I have no problem telling them to go elsewhere. (This doesn’t include those with neurologic reasons for such behavior.)

Some doctors are more willing to put up with this than I am. I once shared space with one who routinely told his staff to ignore abusive behaviors. He didn’t want to turn away any potential revenue or risk angering a referring doctor.

I take another view. Life is short, and medical practice is, by nature, hectic. I have little enough time to care for the patients who genuinely appreciate what my staff and I are trying to do for them. People who are abusive and belligerent can find another doctor who’s willing to put up with it. I won’t.

My staff and I don’t expect to be thanked. We all signed up to work here. But we also try to treat patients with concern and respect, and ask the same courtesy in return. Isn’t that the golden rule?

Abusive patients are difficult to deal with, time consuming, and contribute to staff burnout. The two awesome women who work here deserve better than that. If they’re not happy, I’m not happy. All it takes is one bad person to throw the day off kilter and sometimes affect the care of the next patient in line. That person deserves better, too.

Some will argue that, as a doctor, I should care for all who need my help. In the hospital, I do. I understand that people there generally are scared and hurting and do not want to be there. But in my office I expect at least some degree of civility. We have to be at our best for each person who comes in, and having patients we can work with on a polite level helps.

There’s enough insanity in this job on a good day. People who intentionally try to make it worse aren’t welcome in my little world.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ll put up with a lot in this practice, but I will not tolerate mistreatment of my staff.

Rudeness, while never pleasant, is generally tolerated. Some people just have that sort of personality. Others may be having a crappy day for unrelated reasons. We all have those.

But those who are intentionally abusive of my hardworking assistants aren’t going to get very far here. I have no problem telling them to go elsewhere. (This doesn’t include those with neurologic reasons for such behavior.)

Some doctors are more willing to put up with this than I am. I once shared space with one who routinely told his staff to ignore abusive behaviors. He didn’t want to turn away any potential revenue or risk angering a referring doctor.

I take another view. Life is short, and medical practice is, by nature, hectic. I have little enough time to care for the patients who genuinely appreciate what my staff and I are trying to do for them. People who are abusive and belligerent can find another doctor who’s willing to put up with it. I won’t.

My staff and I don’t expect to be thanked. We all signed up to work here. But we also try to treat patients with concern and respect, and ask the same courtesy in return. Isn’t that the golden rule?

Abusive patients are difficult to deal with, time consuming, and contribute to staff burnout. The two awesome women who work here deserve better than that. If they’re not happy, I’m not happy. All it takes is one bad person to throw the day off kilter and sometimes affect the care of the next patient in line. That person deserves better, too.

Some will argue that, as a doctor, I should care for all who need my help. In the hospital, I do. I understand that people there generally are scared and hurting and do not want to be there. But in my office I expect at least some degree of civility. We have to be at our best for each person who comes in, and having patients we can work with on a polite level helps.

There’s enough insanity in this job on a good day. People who intentionally try to make it worse aren’t welcome in my little world.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ll put up with a lot in this practice, but I will not tolerate mistreatment of my staff.

Rudeness, while never pleasant, is generally tolerated. Some people just have that sort of personality. Others may be having a crappy day for unrelated reasons. We all have those.

But those who are intentionally abusive of my hardworking assistants aren’t going to get very far here. I have no problem telling them to go elsewhere. (This doesn’t include those with neurologic reasons for such behavior.)

Some doctors are more willing to put up with this than I am. I once shared space with one who routinely told his staff to ignore abusive behaviors. He didn’t want to turn away any potential revenue or risk angering a referring doctor.

I take another view. Life is short, and medical practice is, by nature, hectic. I have little enough time to care for the patients who genuinely appreciate what my staff and I are trying to do for them. People who are abusive and belligerent can find another doctor who’s willing to put up with it. I won’t.

My staff and I don’t expect to be thanked. We all signed up to work here. But we also try to treat patients with concern and respect, and ask the same courtesy in return. Isn’t that the golden rule?

Abusive patients are difficult to deal with, time consuming, and contribute to staff burnout. The two awesome women who work here deserve better than that. If they’re not happy, I’m not happy. All it takes is one bad person to throw the day off kilter and sometimes affect the care of the next patient in line. That person deserves better, too.

Some will argue that, as a doctor, I should care for all who need my help. In the hospital, I do. I understand that people there generally are scared and hurting and do not want to be there. But in my office I expect at least some degree of civility. We have to be at our best for each person who comes in, and having patients we can work with on a polite level helps.

There’s enough insanity in this job on a good day. People who intentionally try to make it worse aren’t welcome in my little world.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Higher AML, MDS risk linked to solid tumor chemotherapy

There is an increased risk for therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML) following chemotherapy for the majority of solid tumor types, according to an analysis of cancer registry data.

These findings suggest a substantial expansion in the patients at risk for tMDS/AML because, in the past, excess risks were established only after chemotherapy for cancers of the lung, ovary, breast, soft tissue, testis, and brain or central nervous system,” Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 1,619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013. Data came from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and Medicare claims.

Study participants were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data [does] not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Oncology.

After statistical analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly elevated following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer. They reported a 1.5-fold to more than 10-fold increased relative risk for tMDS/AML in those patients who received chemotherapy for those 22 solid cancer types, compared with the general population.

The relative risks were highest after chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testis cancers.

The researchers found that the absolute risk of developing tMDS/AML was low. Excess absolute risks ranged from 1.4 to greater than 15 cases per 10,000 person-years, compared with the general population, in those 22 solid cancer types. The greatest absolute risks were for peritoneum, small-cell lung, bone, soft-tissue, and fallopian tube cancers.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the limited data on dosing and patient-specific chemotherapy. As a result, Dr. Morton and her colleagues called for a cautious interpretation of the magnitude of the risk.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Morton LM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5625.

Possibly the most clinical relevant finding of the study by Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, and her colleagues is that patients who received chemotherapy for solid tumor treatment at a younger age were at the highest relative risk for tMDS/AML.

The incidence of tMDS/AML was highest among patients treated with chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testicular cancers, where the median age of onset is often by 30 years, and the mean onset occurs before age 50.

The researchers also noted an increased risk for tMDS/AML associated with prolonged survival from primary tumors.

Going forward, research should consider those patients at highest risk for tMDS/AML and risk-assessment models for these therapy-related myeloid neoplasms should take into account the clonal evolution of subclinical mutations into overt disease.

The study findings point to the unanswered question of how best to perform risk assessment of chemotherapy in solid tumors. That risk stratification could include the probability of the specific chemotherapy agent initiating disease, the benefit of tumor regression from chemotherapy, and the potential consequences of tumor progression if chemotherapy is not administered.

Shyam A. Patel, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5617 ).

Possibly the most clinical relevant finding of the study by Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, and her colleagues is that patients who received chemotherapy for solid tumor treatment at a younger age were at the highest relative risk for tMDS/AML.

The incidence of tMDS/AML was highest among patients treated with chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testicular cancers, where the median age of onset is often by 30 years, and the mean onset occurs before age 50.

The researchers also noted an increased risk for tMDS/AML associated with prolonged survival from primary tumors.

Going forward, research should consider those patients at highest risk for tMDS/AML and risk-assessment models for these therapy-related myeloid neoplasms should take into account the clonal evolution of subclinical mutations into overt disease.

The study findings point to the unanswered question of how best to perform risk assessment of chemotherapy in solid tumors. That risk stratification could include the probability of the specific chemotherapy agent initiating disease, the benefit of tumor regression from chemotherapy, and the potential consequences of tumor progression if chemotherapy is not administered.

Shyam A. Patel, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5617 ).

Possibly the most clinical relevant finding of the study by Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, and her colleagues is that patients who received chemotherapy for solid tumor treatment at a younger age were at the highest relative risk for tMDS/AML.

The incidence of tMDS/AML was highest among patients treated with chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testicular cancers, where the median age of onset is often by 30 years, and the mean onset occurs before age 50.

The researchers also noted an increased risk for tMDS/AML associated with prolonged survival from primary tumors.

Going forward, research should consider those patients at highest risk for tMDS/AML and risk-assessment models for these therapy-related myeloid neoplasms should take into account the clonal evolution of subclinical mutations into overt disease.

The study findings point to the unanswered question of how best to perform risk assessment of chemotherapy in solid tumors. That risk stratification could include the probability of the specific chemotherapy agent initiating disease, the benefit of tumor regression from chemotherapy, and the potential consequences of tumor progression if chemotherapy is not administered.

Shyam A. Patel, MD, PhD, is with the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Patel reported having no financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5617 ).

There is an increased risk for therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML) following chemotherapy for the majority of solid tumor types, according to an analysis of cancer registry data.

These findings suggest a substantial expansion in the patients at risk for tMDS/AML because, in the past, excess risks were established only after chemotherapy for cancers of the lung, ovary, breast, soft tissue, testis, and brain or central nervous system,” Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 1,619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013. Data came from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and Medicare claims.

Study participants were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data [does] not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Oncology.

After statistical analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly elevated following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer. They reported a 1.5-fold to more than 10-fold increased relative risk for tMDS/AML in those patients who received chemotherapy for those 22 solid cancer types, compared with the general population.

The relative risks were highest after chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testis cancers.

The researchers found that the absolute risk of developing tMDS/AML was low. Excess absolute risks ranged from 1.4 to greater than 15 cases per 10,000 person-years, compared with the general population, in those 22 solid cancer types. The greatest absolute risks were for peritoneum, small-cell lung, bone, soft-tissue, and fallopian tube cancers.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the limited data on dosing and patient-specific chemotherapy. As a result, Dr. Morton and her colleagues called for a cautious interpretation of the magnitude of the risk.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Morton LM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5625.

There is an increased risk for therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia (tMDS/AML) following chemotherapy for the majority of solid tumor types, according to an analysis of cancer registry data.

These findings suggest a substantial expansion in the patients at risk for tMDS/AML because, in the past, excess risks were established only after chemotherapy for cancers of the lung, ovary, breast, soft tissue, testis, and brain or central nervous system,” Lindsay M. Morton, PhD, of the National Institutes of Health, and her colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 1,619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013. Data came from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and Medicare claims.

Study participants were given initial chemotherapy and lived for at least 1 year after treatment. Subsequently, Dr. Morton and her colleagues linked patient database records with Medicare insurance claim information to confirm the accuracy of chemotherapy data.

“Because registry data [does] not include treatment details, we used an alternative database to provide descriptive information on population-based patterns of chemotherapeutic drug use,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Oncology.

After statistical analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing tMDS/AML was significantly elevated following chemotherapy administration for 22 of 23 solid tumor types, excluding colon cancer. They reported a 1.5-fold to more than 10-fold increased relative risk for tMDS/AML in those patients who received chemotherapy for those 22 solid cancer types, compared with the general population.

The relative risks were highest after chemotherapy for bone, soft-tissue, and testis cancers.

The researchers found that the absolute risk of developing tMDS/AML was low. Excess absolute risks ranged from 1.4 to greater than 15 cases per 10,000 person-years, compared with the general population, in those 22 solid cancer types. The greatest absolute risks were for peritoneum, small-cell lung, bone, soft-tissue, and fallopian tube cancers.

“For patients treated with chemotherapy at the present time, approximately three-quarters of tMDS/AML cases expected to occur within the next 5 years will be attributable to chemotherapy,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged a key limitation of the study was the limited data on dosing and patient-specific chemotherapy. As a result, Dr. Morton and her colleagues called for a cautious interpretation of the magnitude of the risk.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Morton LM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5625.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Treatment with chemotherapy was linked with a 1.5-fold to more than 10-fold increased risk for tMDS/AML.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 1,619 patients with tMDS/AML who were diagnosed with an initial primary solid tumor from 2000 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Morton LM et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5625.

Immediate acting inhibitors complicate hemophilia A diagnosis

A small but substantial proportion of patients with hemophilia A develop immediate acting factor VIII inhibitors, the diversity and complexity of which create a diagnostic challenge in the laboratory, according to authors of a recent observational study.

The great majority of the inhibitor-positive patients in the 4,900-patient study had classical FVIII inhibitors, which are typically time- and temperature-dependent and react more slowly in mixing studies, the researchers reported.

By contrast, about 1 in 10 patients demonstrated immediate acting inhibitors, and of those, some had lupus anticoagulants, some had factor VIII inhibitors, and some had both, according to Shrimati Shetty, PhD, of the National Institute of Immunohaematology in Mumbai, India, and her colleagues.

“There is a possibility of misdiagnosis of the patient when they present for the first time,” the researchers wrote. The report is in Thrombosis Research.

In the case of immediate-acting inhibitors, use of ELISA or chromogenic assays alongside lupus anticoagulant testing may help clarify the diagnosis; however, those tests are costly and may not be routinely available.

In the study by Dr. Shetty and her colleagues, patients in India with congenital hemophilia were initially screened for inhibitors. A total of 451 were found to be positive, and of those, 398 were observed to have classical factor VIII inhibitors, while the remaining 53 had immediate-acting inhibitors.

Looking specifically at hemophilia A patients with immediate-acting inhibitors, which comprised 48 of those 53 patients, the majority, or 42 patients, were positive for lupus anticoagulants, and of those, 38 were positive for both lupus anticoagulants and factor VIII inhibitors, while 4 patients were positive for lupus anticoagulants only.

“These are a heterogeneous group of antibodies interfering with all phospholipid dependent reactions,” the researchers wrote.

Properly interpreting factor inhibitor assays is an important step that helps guide later management of inhibitor-positive patients, according to Dr. Shetty and her coauthors.

“Once the patients become positive for inhibitors, they have to opt for alternate modalities of treatment, i.e. bypassing agents like activated prothrombin complex concentrate and activated recombinant factor VII, which are much more expensive,” they wrote.

In light of the diagnostic difficulties they highlighted, Dr. Shetty and her coauthors recommended a “systematic approach” to testing. Both factor VIII and factor IX assays need to be conducted, along with a lupus anticoagulant test. For inhibitor titer, either chromogenic assays or ELISA tests are recommended, they wrote.

Dr. Shetty and her coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Patil R et al. Thromb Res. 2018 Dec;172:29-35.

A small but substantial proportion of patients with hemophilia A develop immediate acting factor VIII inhibitors, the diversity and complexity of which create a diagnostic challenge in the laboratory, according to authors of a recent observational study.

The great majority of the inhibitor-positive patients in the 4,900-patient study had classical FVIII inhibitors, which are typically time- and temperature-dependent and react more slowly in mixing studies, the researchers reported.

By contrast, about 1 in 10 patients demonstrated immediate acting inhibitors, and of those, some had lupus anticoagulants, some had factor VIII inhibitors, and some had both, according to Shrimati Shetty, PhD, of the National Institute of Immunohaematology in Mumbai, India, and her colleagues.

“There is a possibility of misdiagnosis of the patient when they present for the first time,” the researchers wrote. The report is in Thrombosis Research.

In the case of immediate-acting inhibitors, use of ELISA or chromogenic assays alongside lupus anticoagulant testing may help clarify the diagnosis; however, those tests are costly and may not be routinely available.

In the study by Dr. Shetty and her colleagues, patients in India with congenital hemophilia were initially screened for inhibitors. A total of 451 were found to be positive, and of those, 398 were observed to have classical factor VIII inhibitors, while the remaining 53 had immediate-acting inhibitors.

Looking specifically at hemophilia A patients with immediate-acting inhibitors, which comprised 48 of those 53 patients, the majority, or 42 patients, were positive for lupus anticoagulants, and of those, 38 were positive for both lupus anticoagulants and factor VIII inhibitors, while 4 patients were positive for lupus anticoagulants only.

“These are a heterogeneous group of antibodies interfering with all phospholipid dependent reactions,” the researchers wrote.

Properly interpreting factor inhibitor assays is an important step that helps guide later management of inhibitor-positive patients, according to Dr. Shetty and her coauthors.

“Once the patients become positive for inhibitors, they have to opt for alternate modalities of treatment, i.e. bypassing agents like activated prothrombin complex concentrate and activated recombinant factor VII, which are much more expensive,” they wrote.

In light of the diagnostic difficulties they highlighted, Dr. Shetty and her coauthors recommended a “systematic approach” to testing. Both factor VIII and factor IX assays need to be conducted, along with a lupus anticoagulant test. For inhibitor titer, either chromogenic assays or ELISA tests are recommended, they wrote.

Dr. Shetty and her coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Patil R et al. Thromb Res. 2018 Dec;172:29-35.

A small but substantial proportion of patients with hemophilia A develop immediate acting factor VIII inhibitors, the diversity and complexity of which create a diagnostic challenge in the laboratory, according to authors of a recent observational study.

The great majority of the inhibitor-positive patients in the 4,900-patient study had classical FVIII inhibitors, which are typically time- and temperature-dependent and react more slowly in mixing studies, the researchers reported.

By contrast, about 1 in 10 patients demonstrated immediate acting inhibitors, and of those, some had lupus anticoagulants, some had factor VIII inhibitors, and some had both, according to Shrimati Shetty, PhD, of the National Institute of Immunohaematology in Mumbai, India, and her colleagues.

“There is a possibility of misdiagnosis of the patient when they present for the first time,” the researchers wrote. The report is in Thrombosis Research.

In the case of immediate-acting inhibitors, use of ELISA or chromogenic assays alongside lupus anticoagulant testing may help clarify the diagnosis; however, those tests are costly and may not be routinely available.

In the study by Dr. Shetty and her colleagues, patients in India with congenital hemophilia were initially screened for inhibitors. A total of 451 were found to be positive, and of those, 398 were observed to have classical factor VIII inhibitors, while the remaining 53 had immediate-acting inhibitors.

Looking specifically at hemophilia A patients with immediate-acting inhibitors, which comprised 48 of those 53 patients, the majority, or 42 patients, were positive for lupus anticoagulants, and of those, 38 were positive for both lupus anticoagulants and factor VIII inhibitors, while 4 patients were positive for lupus anticoagulants only.

“These are a heterogeneous group of antibodies interfering with all phospholipid dependent reactions,” the researchers wrote.

Properly interpreting factor inhibitor assays is an important step that helps guide later management of inhibitor-positive patients, according to Dr. Shetty and her coauthors.

“Once the patients become positive for inhibitors, they have to opt for alternate modalities of treatment, i.e. bypassing agents like activated prothrombin complex concentrate and activated recombinant factor VII, which are much more expensive,” they wrote.

In light of the diagnostic difficulties they highlighted, Dr. Shetty and her coauthors recommended a “systematic approach” to testing. Both factor VIII and factor IX assays need to be conducted, along with a lupus anticoagulant test. For inhibitor titer, either chromogenic assays or ELISA tests are recommended, they wrote.

Dr. Shetty and her coauthors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Patil R et al. Thromb Res. 2018 Dec;172:29-35.

FROM THROMBOSIS RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 48 inhibitor-positive hemophilia A patients with immediate acting inhibitors, 42 were positive for lupus anticoagulants.

Study details: An analysis of 4,900 patients in India with confirmed or suspected congenital hemophilia.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Patil R et al. Thromb Res. 2018 Dec;172:29-35.

Patient-reported outcomes for patients with chronic liver disease

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

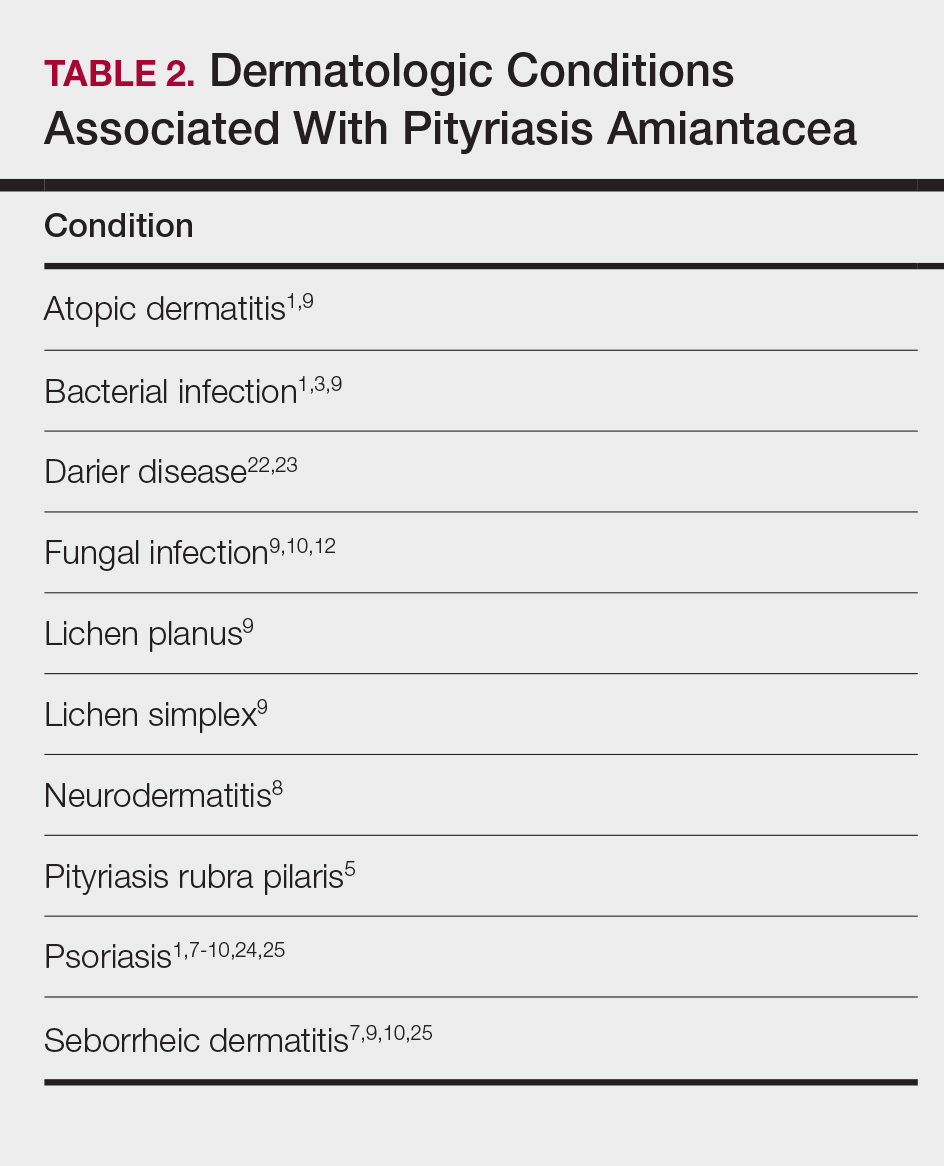

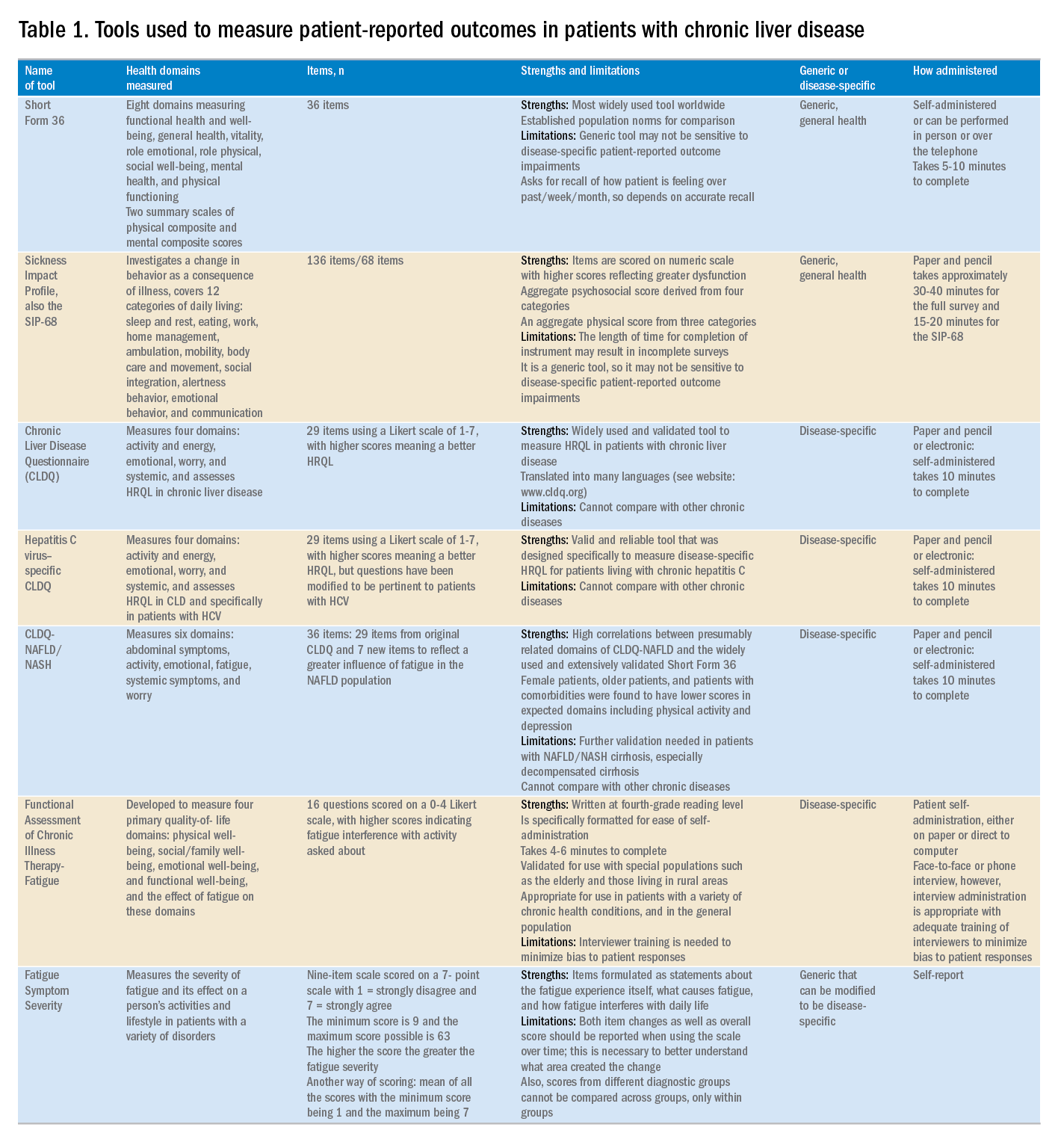

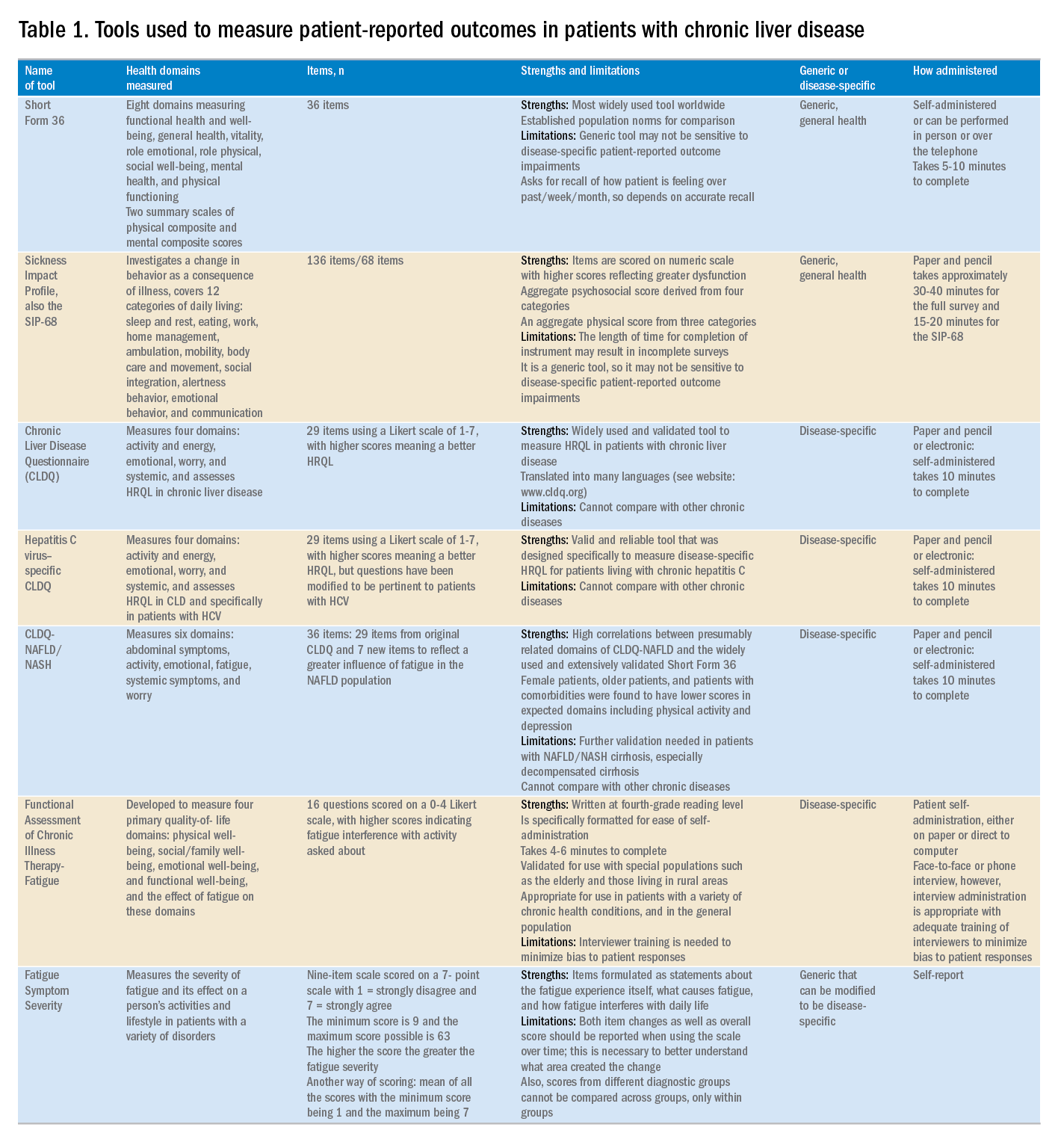

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes