User login

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

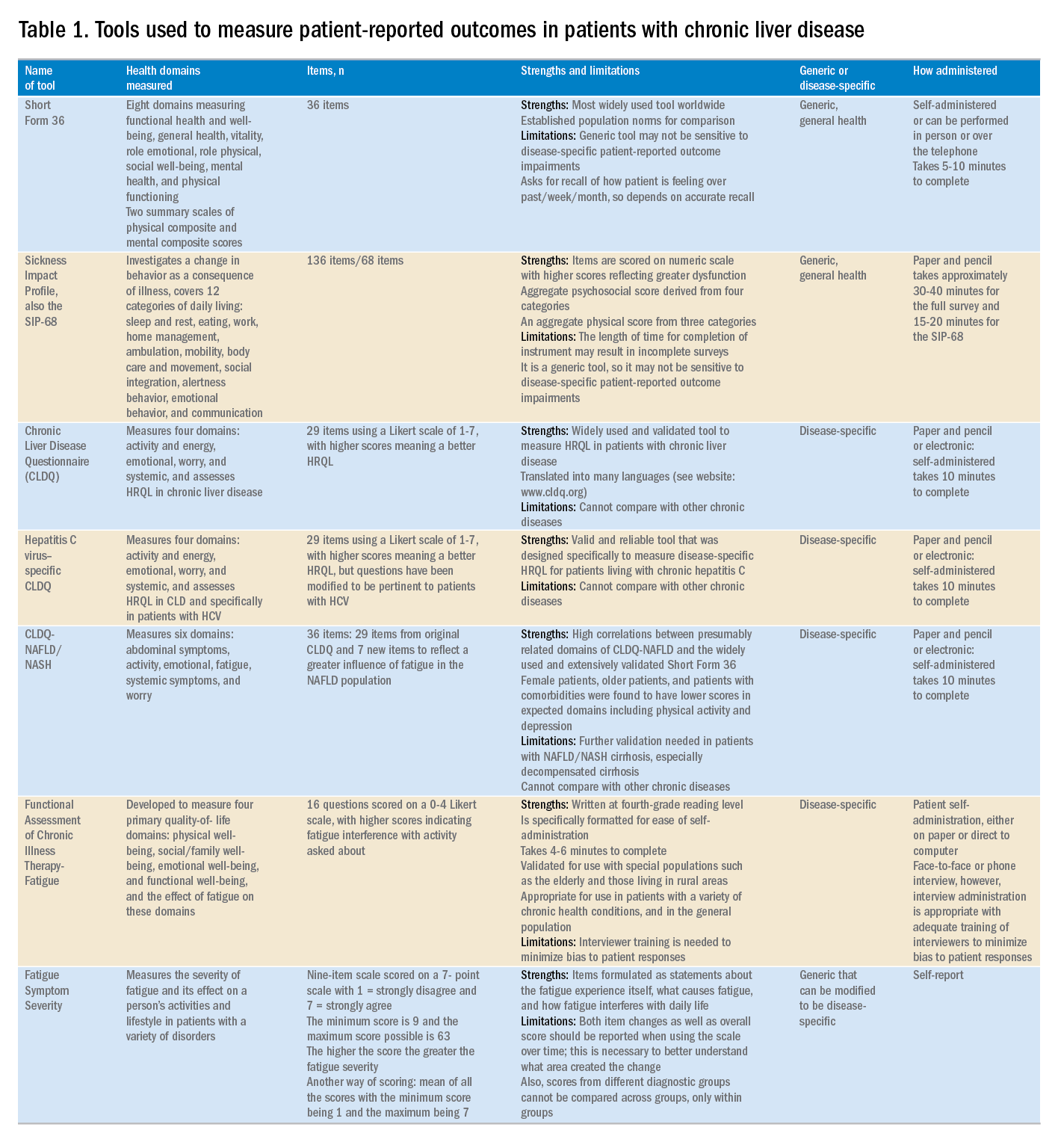

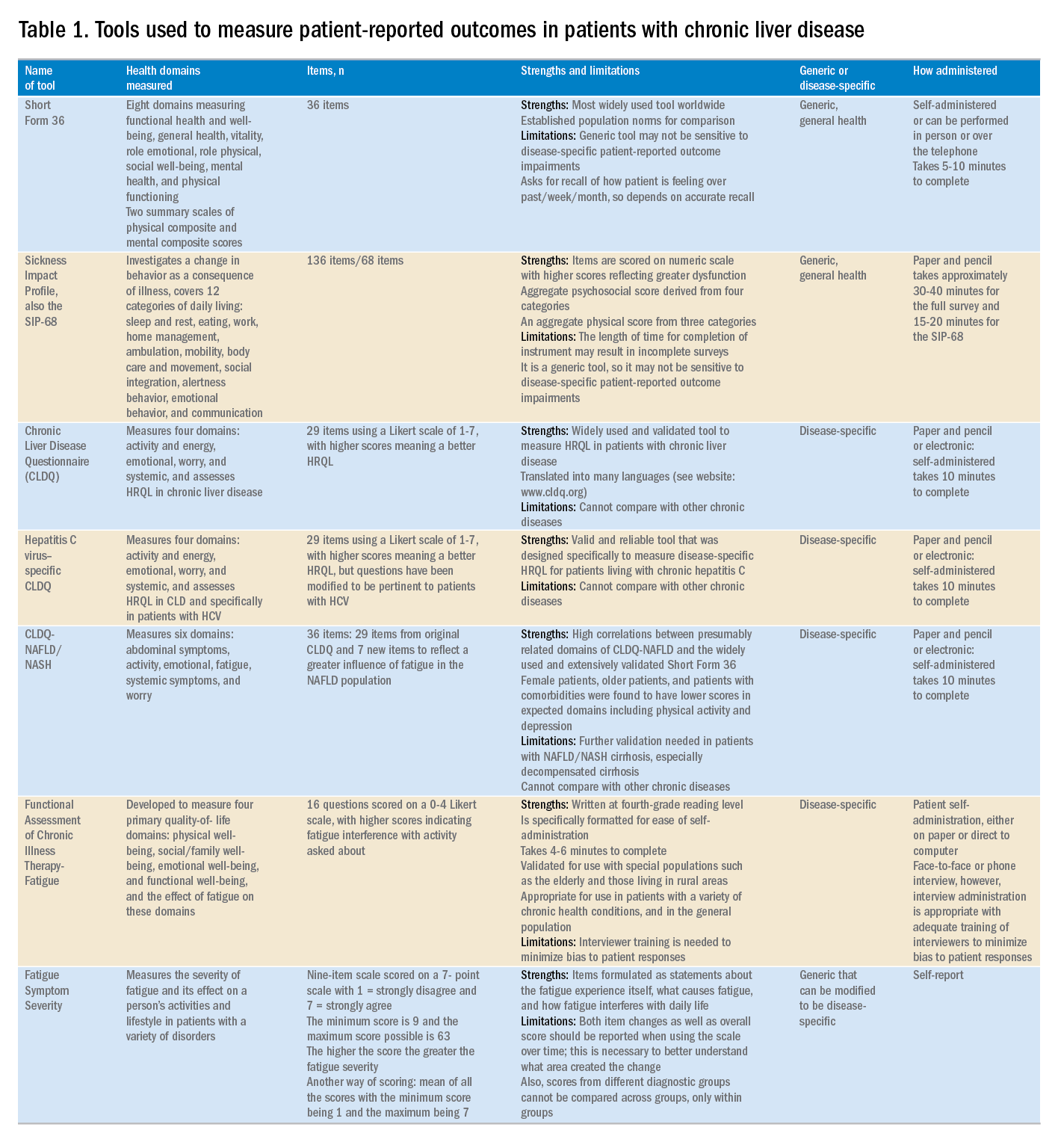

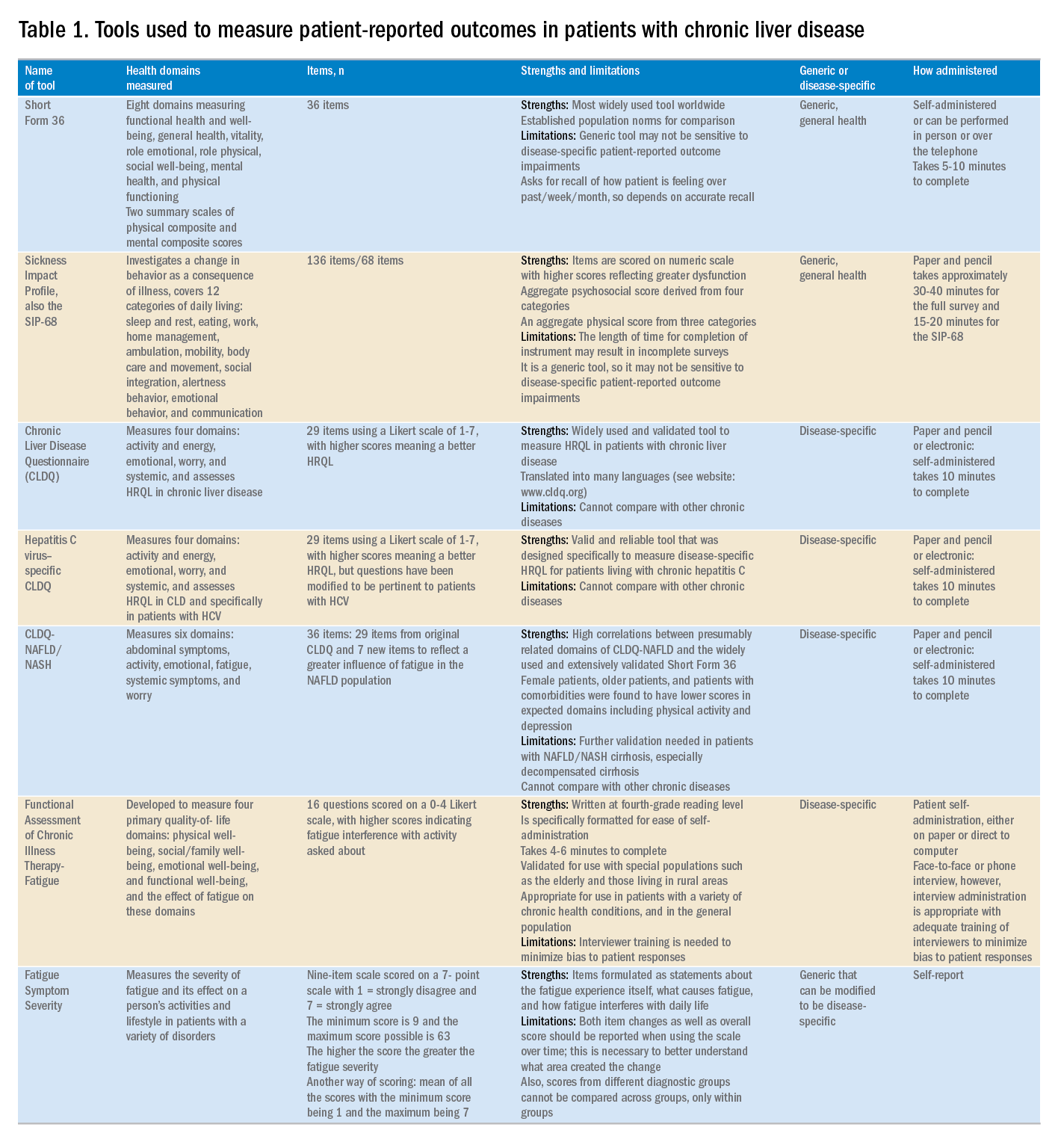

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.