User login

Through the eyes of migraine: Ocular considerations

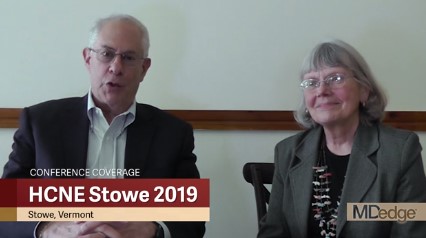

STOWE, VT. – said Kathleen Digre, MD, at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England. Specifically, she said, dry eye and photophobia are two symptoms that have biologic underpinnings, can be diagnosed, and can be treated. Dr. Digre is a professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is the current president of the American Headache Society.

Dr. Digre explained that dry eyes and migraine could have a cyclical relationship where dry eyes provoke the migraine, and the migraine may provoke the feeling of dry eye, regardless of whether it can be objectively measured.

Regarding photophobia, Dr. Digre stressed the importance of an accurate diagnosis that rules out eye disorders and other causes of photophobia. She discussed the problem of patient overreliance on dark glasses and encourages a return to light to break the cycle of dark adapting the retina.

Finally, Dr. Digre discussed how proper treatment of migraine and any associated anxiety or depression can help resolve eye issues that may be contributing to migraine.

STOWE, VT. – said Kathleen Digre, MD, at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England. Specifically, she said, dry eye and photophobia are two symptoms that have biologic underpinnings, can be diagnosed, and can be treated. Dr. Digre is a professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is the current president of the American Headache Society.

Dr. Digre explained that dry eyes and migraine could have a cyclical relationship where dry eyes provoke the migraine, and the migraine may provoke the feeling of dry eye, regardless of whether it can be objectively measured.

Regarding photophobia, Dr. Digre stressed the importance of an accurate diagnosis that rules out eye disorders and other causes of photophobia. She discussed the problem of patient overreliance on dark glasses and encourages a return to light to break the cycle of dark adapting the retina.

Finally, Dr. Digre discussed how proper treatment of migraine and any associated anxiety or depression can help resolve eye issues that may be contributing to migraine.

STOWE, VT. – said Kathleen Digre, MD, at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England. Specifically, she said, dry eye and photophobia are two symptoms that have biologic underpinnings, can be diagnosed, and can be treated. Dr. Digre is a professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is the current president of the American Headache Society.

Dr. Digre explained that dry eyes and migraine could have a cyclical relationship where dry eyes provoke the migraine, and the migraine may provoke the feeling of dry eye, regardless of whether it can be objectively measured.

Regarding photophobia, Dr. Digre stressed the importance of an accurate diagnosis that rules out eye disorders and other causes of photophobia. She discussed the problem of patient overreliance on dark glasses and encourages a return to light to break the cycle of dark adapting the retina.

Finally, Dr. Digre discussed how proper treatment of migraine and any associated anxiety or depression can help resolve eye issues that may be contributing to migraine.

REPORTING FROM HCNE STOWE 2019

CGRP drugs: How is it going?

STOWE, VT. – These are the early days of the “CGRP monoclonal antibody era,”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England, Dr. McAllister said, “We are comforted that we have now 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year data” from clinical trials, but the sample size is small.

In the time since the first three drugs were approved, “we have probably in the ballpark of over 200,000 patients who have received a monoclonal antibody, and so far there has been nothing that makes us stop cold in our tracks and say there’s something wrong here. That is very comforting,” he said. Dr. McAllister is the medical director of the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Conn.

What is still unknown, however, is the long-term safety and efficacy; what happens in a larger pool of patients taking these drugs; what happens in pregnancy and effects on the fetus; how and when to safely switch from one monoclonal antibody to another; the systemic effects of these drugs; and other concerns that may arise in postmarketing studies.

STOWE, VT. – These are the early days of the “CGRP monoclonal antibody era,”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England, Dr. McAllister said, “We are comforted that we have now 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year data” from clinical trials, but the sample size is small.

In the time since the first three drugs were approved, “we have probably in the ballpark of over 200,000 patients who have received a monoclonal antibody, and so far there has been nothing that makes us stop cold in our tracks and say there’s something wrong here. That is very comforting,” he said. Dr. McAllister is the medical director of the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Conn.

What is still unknown, however, is the long-term safety and efficacy; what happens in a larger pool of patients taking these drugs; what happens in pregnancy and effects on the fetus; how and when to safely switch from one monoclonal antibody to another; the systemic effects of these drugs; and other concerns that may arise in postmarketing studies.

STOWE, VT. – These are the early days of the “CGRP monoclonal antibody era,”

In an interview at the annual meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England, Dr. McAllister said, “We are comforted that we have now 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year data” from clinical trials, but the sample size is small.

In the time since the first three drugs were approved, “we have probably in the ballpark of over 200,000 patients who have received a monoclonal antibody, and so far there has been nothing that makes us stop cold in our tracks and say there’s something wrong here. That is very comforting,” he said. Dr. McAllister is the medical director of the New England Institute for Neurology and Headache in Stamford, Conn.

What is still unknown, however, is the long-term safety and efficacy; what happens in a larger pool of patients taking these drugs; what happens in pregnancy and effects on the fetus; how and when to safely switch from one monoclonal antibody to another; the systemic effects of these drugs; and other concerns that may arise in postmarketing studies.

REPORTING FROM HCNE STOWE 2019

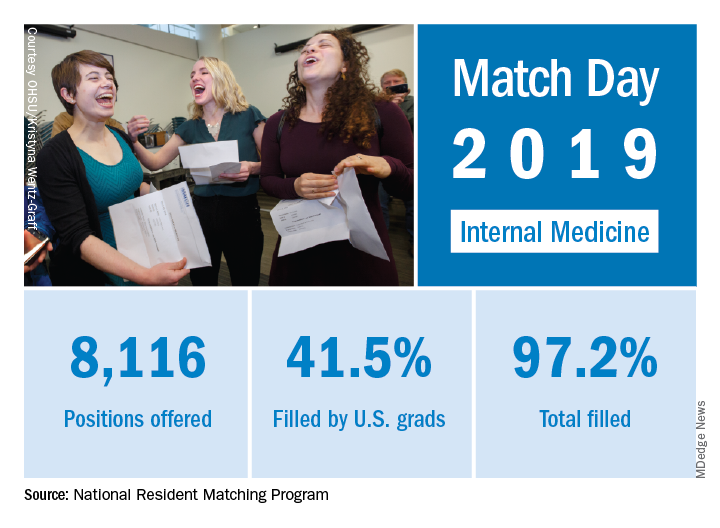

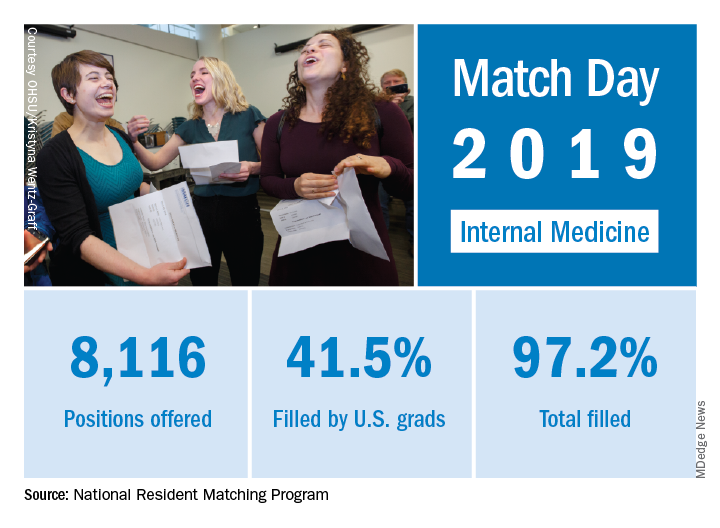

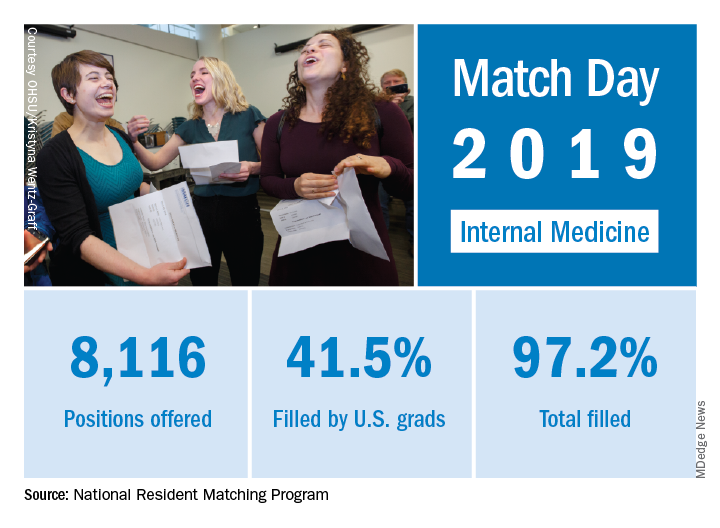

Match Day 2019: Internal medicine slots up by 7.6%

Internal medicine residency positions rose by 7.6% for Match Day 2019, but the number of slots filled by U.S. allopathic seniors dropped for the fourth consecutive year, according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

First-year (PGY-1) IM slots rose from 7,542 to 8,116 as internal medicine manged to exceed the 6.5% increase in PGY-1 positions over 2018 for all specialties combined. The total numbers of applicants (38,376) and positions offered (35,185) were both record highs for the Match, although they were affected, in part, by “increased numbers of osteopathic programs that joined the Main Residency Match as a result of the ongoing transition to a single accreditation system for graduate medical education programs,” the NRMP noted in a statement.

and 44.9% in 2017 and continues a fairly long-term trend of increased participation by international medical graduates. Overall, IM filled 97.2% of all available PGY-1 slots in this year, which was above the 94.9% for all specialties in the Match, the NRMP reported.

The primary care specialties – family medicine, internal medicine, internal medicine–pediatrics, internal medicine–primary, pediatrics, and pediatrics-primary – offered 15,946 first-year positions, just under half of the 32,194 available in this year’s Match. Overall, 7.8% more primary care slots were offered this year, compared with in 2018.

“The results of the Match are closely watched because they can be predictors of future physician workforce supply. There also is significant interest in the competitiveness of specialties, as measured by the percentage of positions filled overall and the percentage filled by senior students in U.S. allopathic medical schools,” the NRMP noted.

Internal medicine residency positions rose by 7.6% for Match Day 2019, but the number of slots filled by U.S. allopathic seniors dropped for the fourth consecutive year, according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

First-year (PGY-1) IM slots rose from 7,542 to 8,116 as internal medicine manged to exceed the 6.5% increase in PGY-1 positions over 2018 for all specialties combined. The total numbers of applicants (38,376) and positions offered (35,185) were both record highs for the Match, although they were affected, in part, by “increased numbers of osteopathic programs that joined the Main Residency Match as a result of the ongoing transition to a single accreditation system for graduate medical education programs,” the NRMP noted in a statement.

and 44.9% in 2017 and continues a fairly long-term trend of increased participation by international medical graduates. Overall, IM filled 97.2% of all available PGY-1 slots in this year, which was above the 94.9% for all specialties in the Match, the NRMP reported.

The primary care specialties – family medicine, internal medicine, internal medicine–pediatrics, internal medicine–primary, pediatrics, and pediatrics-primary – offered 15,946 first-year positions, just under half of the 32,194 available in this year’s Match. Overall, 7.8% more primary care slots were offered this year, compared with in 2018.

“The results of the Match are closely watched because they can be predictors of future physician workforce supply. There also is significant interest in the competitiveness of specialties, as measured by the percentage of positions filled overall and the percentage filled by senior students in U.S. allopathic medical schools,” the NRMP noted.

Internal medicine residency positions rose by 7.6% for Match Day 2019, but the number of slots filled by U.S. allopathic seniors dropped for the fourth consecutive year, according to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

First-year (PGY-1) IM slots rose from 7,542 to 8,116 as internal medicine manged to exceed the 6.5% increase in PGY-1 positions over 2018 for all specialties combined. The total numbers of applicants (38,376) and positions offered (35,185) were both record highs for the Match, although they were affected, in part, by “increased numbers of osteopathic programs that joined the Main Residency Match as a result of the ongoing transition to a single accreditation system for graduate medical education programs,” the NRMP noted in a statement.

and 44.9% in 2017 and continues a fairly long-term trend of increased participation by international medical graduates. Overall, IM filled 97.2% of all available PGY-1 slots in this year, which was above the 94.9% for all specialties in the Match, the NRMP reported.

The primary care specialties – family medicine, internal medicine, internal medicine–pediatrics, internal medicine–primary, pediatrics, and pediatrics-primary – offered 15,946 first-year positions, just under half of the 32,194 available in this year’s Match. Overall, 7.8% more primary care slots were offered this year, compared with in 2018.

“The results of the Match are closely watched because they can be predictors of future physician workforce supply. There also is significant interest in the competitiveness of specialties, as measured by the percentage of positions filled overall and the percentage filled by senior students in U.S. allopathic medical schools,” the NRMP noted.

Combo may improve PFS, OS for certain ovarian cancer patients

HONOLULU – Combining avelumab with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) may provide a survival benefit in certain patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer, a phase 3 trial suggests.

In the overall study population, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were not significantly different for patients who received avelumab plus PLD and those who received avelumab or PLD alone.

However, some subgroups did experience survival benefits with the combination, including patients who were positive for programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) and those who had received two or three prior lines of therapy.

Eric Pujade-Lauraine, MD, PhD, of ARCAGY-GINECO in Paris, presented these results from the JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The trial enrolled 566 patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. They were not preselected for PD-L1 expression.

Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive avelumab at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks (n = 188), avelumab plus PLD at 40 mg/m2 every 4 weeks (n = 188), or PLD (n = 190).

Baseline characteristics were similar across the treatment arms. The median age was 61 in the avelumab arm and 60 in the other two arms (range, 26-86 years). In each arm, about 37% of patients had bulky disease, and all but two patients (both in the avelumab arm) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1.

Nearly half of patients had received one line of prior therapy, and the rest had received two or three prior lines of therapy. About 75% of patients had platinum-resistant disease, and 25% were platinum refractory.

The median duration of study treatment was 10.1 weeks in the avelumab arm and 16.0 weeks in the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) arm. In the combination arm, the median treatment duration was 16.9 weeks for avelumab and 16.3 weeks for PLD. In each arm, the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression.

Safety

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said no new safety signals were observed with avelumab alone or in combination.

Serious treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 7.5% of patients in the avelumab arm, 17.6% of patients in the combination arm, and 10.7% of patients in the PLD arm. Discontinuation because of a treatment-related AE occurred in 6.4%, 4.4%, and 7.3% of patients, respectively.

There was one treatment-related AE leading to death in the avelumab arm and one in the PLD arm.

AEs that were more common in the combination arm than in the avelumab and PLD arms (respectively) were fatigue/asthenia (42.3%, 26.7%, and 28.8%), rash (34.1%, 8.0%, and 16.9%), stomatitis (28.0%, 2.1%, and 20.3%), and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (33.0%, 0.5%, and 22.6%).

Response

The objective response rate was 3.7% in the avelumab arm, 13.3% in the combination arm, and 4.2% in the PLD arm. There were two complete responses; both occurred in the combination arm.

The response rate was significantly higher in the combination arm (odds ratio, 3.458, P = .0018) than in the PLD arm, but there was no significant difference in response rate between the avelumab arm and the PLD arm (OR, 0.890, P = .8280).

The median duration of response was 9.2 months in the avelumab arm, 8.5 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

Survival

There was a trend toward improved PFS with avelumab plus PLD, but the significance threshold was not met.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm, 3.7 months in the combination arm, and 3.5 months in the PLD arm. With the PLD arm as a reference, the stratified hazard ratio was 1.68 for the avelumab arm (P greater than .999) and 0.78 for the combination arm (P = .0301).

The median OS was 11.8 months in the avelumab arm, 15.7 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm. The HR was 1.14 for the avelumab arm (P = .8253) and 0.89 for the combination arm (P = .2082).

“[A]velumab plus PLD showed clinical activity, but, in this unselected population, the trial did not meet the primary objective [of improving PFS or OS compared to PLD alone],” Dr. Pujade-Lauraine noted. “However, prespecified analyses indicate a potential role of PD-L1 expression as a predictor of clinical benefit.”

When Dr. Pujade-Lauraine and his colleagues looked at patients who were positive for PD-L1 (57%), the researchers found a significant improvement in PFS, but not OS, with avelumab plus PLD.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm (HR,1.45, P = .0303), 3.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.65, P = .0143), and 3.0 months in the PLD arm.

The median OS was 13.7 months in the avelumab arm (HR, 0.83, P = .3580), 17.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.72, P = .0842), and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

The researchers also found that PFS and OS were better with avelumab plus PLD versus PLD alone among patients who had received two or three prior treatment regimens at baseline. The HR was 0.62 for PFS and 0.64 for OS.

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said further subgroup analyses are ongoing.

This trial was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Pujade-Lauraine reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Incyte, Pfizer, Roche, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Pujade-Lauraine E et al. SGO 2019, Abstract LBA1.

HONOLULU – Combining avelumab with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) may provide a survival benefit in certain patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer, a phase 3 trial suggests.

In the overall study population, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were not significantly different for patients who received avelumab plus PLD and those who received avelumab or PLD alone.

However, some subgroups did experience survival benefits with the combination, including patients who were positive for programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) and those who had received two or three prior lines of therapy.

Eric Pujade-Lauraine, MD, PhD, of ARCAGY-GINECO in Paris, presented these results from the JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The trial enrolled 566 patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. They were not preselected for PD-L1 expression.

Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive avelumab at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks (n = 188), avelumab plus PLD at 40 mg/m2 every 4 weeks (n = 188), or PLD (n = 190).

Baseline characteristics were similar across the treatment arms. The median age was 61 in the avelumab arm and 60 in the other two arms (range, 26-86 years). In each arm, about 37% of patients had bulky disease, and all but two patients (both in the avelumab arm) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1.

Nearly half of patients had received one line of prior therapy, and the rest had received two or three prior lines of therapy. About 75% of patients had platinum-resistant disease, and 25% were platinum refractory.

The median duration of study treatment was 10.1 weeks in the avelumab arm and 16.0 weeks in the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) arm. In the combination arm, the median treatment duration was 16.9 weeks for avelumab and 16.3 weeks for PLD. In each arm, the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression.

Safety

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said no new safety signals were observed with avelumab alone or in combination.

Serious treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 7.5% of patients in the avelumab arm, 17.6% of patients in the combination arm, and 10.7% of patients in the PLD arm. Discontinuation because of a treatment-related AE occurred in 6.4%, 4.4%, and 7.3% of patients, respectively.

There was one treatment-related AE leading to death in the avelumab arm and one in the PLD arm.

AEs that were more common in the combination arm than in the avelumab and PLD arms (respectively) were fatigue/asthenia (42.3%, 26.7%, and 28.8%), rash (34.1%, 8.0%, and 16.9%), stomatitis (28.0%, 2.1%, and 20.3%), and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (33.0%, 0.5%, and 22.6%).

Response

The objective response rate was 3.7% in the avelumab arm, 13.3% in the combination arm, and 4.2% in the PLD arm. There were two complete responses; both occurred in the combination arm.

The response rate was significantly higher in the combination arm (odds ratio, 3.458, P = .0018) than in the PLD arm, but there was no significant difference in response rate between the avelumab arm and the PLD arm (OR, 0.890, P = .8280).

The median duration of response was 9.2 months in the avelumab arm, 8.5 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

Survival

There was a trend toward improved PFS with avelumab plus PLD, but the significance threshold was not met.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm, 3.7 months in the combination arm, and 3.5 months in the PLD arm. With the PLD arm as a reference, the stratified hazard ratio was 1.68 for the avelumab arm (P greater than .999) and 0.78 for the combination arm (P = .0301).

The median OS was 11.8 months in the avelumab arm, 15.7 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm. The HR was 1.14 for the avelumab arm (P = .8253) and 0.89 for the combination arm (P = .2082).

“[A]velumab plus PLD showed clinical activity, but, in this unselected population, the trial did not meet the primary objective [of improving PFS or OS compared to PLD alone],” Dr. Pujade-Lauraine noted. “However, prespecified analyses indicate a potential role of PD-L1 expression as a predictor of clinical benefit.”

When Dr. Pujade-Lauraine and his colleagues looked at patients who were positive for PD-L1 (57%), the researchers found a significant improvement in PFS, but not OS, with avelumab plus PLD.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm (HR,1.45, P = .0303), 3.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.65, P = .0143), and 3.0 months in the PLD arm.

The median OS was 13.7 months in the avelumab arm (HR, 0.83, P = .3580), 17.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.72, P = .0842), and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

The researchers also found that PFS and OS were better with avelumab plus PLD versus PLD alone among patients who had received two or three prior treatment regimens at baseline. The HR was 0.62 for PFS and 0.64 for OS.

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said further subgroup analyses are ongoing.

This trial was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Pujade-Lauraine reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Incyte, Pfizer, Roche, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Pujade-Lauraine E et al. SGO 2019, Abstract LBA1.

HONOLULU – Combining avelumab with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) may provide a survival benefit in certain patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer, a phase 3 trial suggests.

In the overall study population, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were not significantly different for patients who received avelumab plus PLD and those who received avelumab or PLD alone.

However, some subgroups did experience survival benefits with the combination, including patients who were positive for programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) and those who had received two or three prior lines of therapy.

Eric Pujade-Lauraine, MD, PhD, of ARCAGY-GINECO in Paris, presented these results from the JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer.

The trial enrolled 566 patients with platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. They were not preselected for PD-L1 expression.

Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive avelumab at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks (n = 188), avelumab plus PLD at 40 mg/m2 every 4 weeks (n = 188), or PLD (n = 190).

Baseline characteristics were similar across the treatment arms. The median age was 61 in the avelumab arm and 60 in the other two arms (range, 26-86 years). In each arm, about 37% of patients had bulky disease, and all but two patients (both in the avelumab arm) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1.

Nearly half of patients had received one line of prior therapy, and the rest had received two or three prior lines of therapy. About 75% of patients had platinum-resistant disease, and 25% were platinum refractory.

The median duration of study treatment was 10.1 weeks in the avelumab arm and 16.0 weeks in the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) arm. In the combination arm, the median treatment duration was 16.9 weeks for avelumab and 16.3 weeks for PLD. In each arm, the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression.

Safety

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said no new safety signals were observed with avelumab alone or in combination.

Serious treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 7.5% of patients in the avelumab arm, 17.6% of patients in the combination arm, and 10.7% of patients in the PLD arm. Discontinuation because of a treatment-related AE occurred in 6.4%, 4.4%, and 7.3% of patients, respectively.

There was one treatment-related AE leading to death in the avelumab arm and one in the PLD arm.

AEs that were more common in the combination arm than in the avelumab and PLD arms (respectively) were fatigue/asthenia (42.3%, 26.7%, and 28.8%), rash (34.1%, 8.0%, and 16.9%), stomatitis (28.0%, 2.1%, and 20.3%), and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (33.0%, 0.5%, and 22.6%).

Response

The objective response rate was 3.7% in the avelumab arm, 13.3% in the combination arm, and 4.2% in the PLD arm. There were two complete responses; both occurred in the combination arm.

The response rate was significantly higher in the combination arm (odds ratio, 3.458, P = .0018) than in the PLD arm, but there was no significant difference in response rate between the avelumab arm and the PLD arm (OR, 0.890, P = .8280).

The median duration of response was 9.2 months in the avelumab arm, 8.5 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

Survival

There was a trend toward improved PFS with avelumab plus PLD, but the significance threshold was not met.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm, 3.7 months in the combination arm, and 3.5 months in the PLD arm. With the PLD arm as a reference, the stratified hazard ratio was 1.68 for the avelumab arm (P greater than .999) and 0.78 for the combination arm (P = .0301).

The median OS was 11.8 months in the avelumab arm, 15.7 months in the combination arm, and 13.1 months in the PLD arm. The HR was 1.14 for the avelumab arm (P = .8253) and 0.89 for the combination arm (P = .2082).

“[A]velumab plus PLD showed clinical activity, but, in this unselected population, the trial did not meet the primary objective [of improving PFS or OS compared to PLD alone],” Dr. Pujade-Lauraine noted. “However, prespecified analyses indicate a potential role of PD-L1 expression as a predictor of clinical benefit.”

When Dr. Pujade-Lauraine and his colleagues looked at patients who were positive for PD-L1 (57%), the researchers found a significant improvement in PFS, but not OS, with avelumab plus PLD.

The median PFS was 1.9 months in the avelumab arm (HR,1.45, P = .0303), 3.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.65, P = .0143), and 3.0 months in the PLD arm.

The median OS was 13.7 months in the avelumab arm (HR, 0.83, P = .3580), 17.7 months in the combination arm (HR, 0.72, P = .0842), and 13.1 months in the PLD arm.

The researchers also found that PFS and OS were better with avelumab plus PLD versus PLD alone among patients who had received two or three prior treatment regimens at baseline. The HR was 0.62 for PFS and 0.64 for OS.

Dr. Pujade-Lauraine said further subgroup analyses are ongoing.

This trial was sponsored by Pfizer. Dr. Pujade-Lauraine reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Incyte, Pfizer, Roche, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Pujade-Lauraine E et al. SGO 2019, Abstract LBA1.

REPORTING FROM SGO 2019

Comment on Reporting Standards

The Society for Vascular Surgeons and the Society for Thoracic Surgeons are seeking comments on draft Reporting Standards for Type-B Aortic Dissection. Reports focusing on type-B aortic dissection have become increasingly common in recent years, but there is currently no guidance for investigators on reporting. Submit your comments here and direct questions to Kristin Hitchcock, the SVS senior manager for guidelines & quality.

The Society for Vascular Surgeons and the Society for Thoracic Surgeons are seeking comments on draft Reporting Standards for Type-B Aortic Dissection. Reports focusing on type-B aortic dissection have become increasingly common in recent years, but there is currently no guidance for investigators on reporting. Submit your comments here and direct questions to Kristin Hitchcock, the SVS senior manager for guidelines & quality.

The Society for Vascular Surgeons and the Society for Thoracic Surgeons are seeking comments on draft Reporting Standards for Type-B Aortic Dissection. Reports focusing on type-B aortic dissection have become increasingly common in recent years, but there is currently no guidance for investigators on reporting. Submit your comments here and direct questions to Kristin Hitchcock, the SVS senior manager for guidelines & quality.

Immediate angiography after non-STEMI cardiac arrest confers no survival benefit

Immediate angiography after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest does not improve survival compared to delaying angiography until neurologic recovery in patients with no evidence of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial involved 552 patients who had been successfully resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, without signs of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The study also excluded patients with shock and severe renal dysfunction, and was not blinded, so this may have influenced treatment decisions.

Patients were randomized either to immediate coronary angiography after resuscitation, while still unconscious, or delayed coronary angiography until they had recovered neurologically, which was generally after discharge from intensive care.

Overall, 97.1% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 64.9% of the delayed angiography group underwent coronary angiography, with the median time until angiography being 0.8 hours in the immediate group and 119.9 hours in the delayed group.

In the immediate angiography group, 3.4% of patients were found to have an acute coronary occlusion, while in the delayed group that figure was 7.6%. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 33% of the immediate angiography group and 24.2% of the delayed angiography group.

Survival rates at 90 days were not significantly different between the two groups; 64.5% of the immediate angiography group and 67.2% of the delayed angiography group survived to 90 days (OR 0.89, P = 0.51). The two groups also did not significantly differ in the secondary endpoints of survival with good cerebral performance or mild-to-moderate disability (62.9% vs. 64.4%).

“Our findings do not corroborate findings of previous observational studies, which showed a survival benefit with immediate coronary angiography in patients who had cardiac arrest without STEMI,” wrote Dr. Jorrit S. Lemkes, from the department of cardiology at Amsterdam University Medical Center VUmc, and co-authors. “This difference could be related to the observational nature of the previous studies, which may have resulted in selection bias that favored treating patients who had a presumed better prognosis with a strategy of immediate angiography.”

They also suggested the lack of benefit from early coronary angiography could relate to the fact that majority of those who died did so as a result of neurological complications, as has been seen in other studies of resuscitation.

The authors did note that the vast majority of patients in the study had stable coronary artery lesions, and only 5% showed thrombotic occlusions. They suggested this could explain their results, as percutaneous coronary intervention was not associated with improved outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery lesions – only in patients with acute thrombotic coronary occlusions.

However, they did see the suggestion of a treatment effect in patients over 70 years old and those with a history of coronary artery disease.

The study also revealed differences in subsequent treatment between patients who underwent immediate coronary angiography and those who had delayed angiography. Those in the delayed group were significantly more likely to be treated with salicylates or a P2Y12 inhibitor than those in the immediate angiography group.

“This observation illustrates how the result of immediate coronary angiography can influence treatment, since patients who did not have evidence of coronary artery disease on angiography do not require antiplatelet therapy,” the authors wrote.

Conversely, patients in the immediate angiography were more likely to receive a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. However the authors said these different strategies did not translate to any significant difference in major bleeding.

The COACT trial results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine simultaneously with Dr.Lemkes's presentation.

COACT was supported by the Netherlands Heart Institute, Biotronik and AstraZeneca. Two authors declared grants and support from the study supporters, both in and outside the context of the study. One author declared grants from private industry outside the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lemkes J et al. NEJM, 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816897

The results of the COACT trial are consistent with other studies in patients with acute coronary syndromes but without evidence of STEMI or cardiac arrest, showing that immediate coronary angiography is not associated with improved outcomes.

However, less than 20% of the COACT cohort had unstable coronary lesions and less than 40% underwent coronary interventions, so relatively few patients would have been affected by the timing of coronary angiography or the procedure itself. In this trial, more than 60% of deaths were due to neurologic injury rather than cardiac complications.

Enriching the study population with patients with probable coronary disease might have led to a different result. A substudy analysis of patients over age 70 with a history of coronary disease showed they were more likely to benefit from immediate coronary angiography than were younger patients without a history of coronary disease.

Prioritizing interventions also had an impact on targeted temperature managemen, which also may have played into the results. The median time to achieve target temperature was 5.4 hours in the immediate angiography group and 4.7 hours in the delayed angiography group.

Additional insights may come from two ongoing clinical trials, ACCESS and DISCO (Direct or Subacute Coronary Angiography in Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest), may shed additional light on how interventions after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest affect patient outcomes.

Dr. Benjamin S. Abella is from the Center for Resuscitation Science and Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and Dr. David F. Gaieski is from the Department of Emergency Medicine at Jefferson Medical College. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe1901651). Both authors declared grants, personal support and other support from private industry outside the submitted work.

The results of the COACT trial are consistent with other studies in patients with acute coronary syndromes but without evidence of STEMI or cardiac arrest, showing that immediate coronary angiography is not associated with improved outcomes.

However, less than 20% of the COACT cohort had unstable coronary lesions and less than 40% underwent coronary interventions, so relatively few patients would have been affected by the timing of coronary angiography or the procedure itself. In this trial, more than 60% of deaths were due to neurologic injury rather than cardiac complications.

Enriching the study population with patients with probable coronary disease might have led to a different result. A substudy analysis of patients over age 70 with a history of coronary disease showed they were more likely to benefit from immediate coronary angiography than were younger patients without a history of coronary disease.

Prioritizing interventions also had an impact on targeted temperature managemen, which also may have played into the results. The median time to achieve target temperature was 5.4 hours in the immediate angiography group and 4.7 hours in the delayed angiography group.

Additional insights may come from two ongoing clinical trials, ACCESS and DISCO (Direct or Subacute Coronary Angiography in Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest), may shed additional light on how interventions after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest affect patient outcomes.

Dr. Benjamin S. Abella is from the Center for Resuscitation Science and Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and Dr. David F. Gaieski is from the Department of Emergency Medicine at Jefferson Medical College. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe1901651). Both authors declared grants, personal support and other support from private industry outside the submitted work.

The results of the COACT trial are consistent with other studies in patients with acute coronary syndromes but without evidence of STEMI or cardiac arrest, showing that immediate coronary angiography is not associated with improved outcomes.

However, less than 20% of the COACT cohort had unstable coronary lesions and less than 40% underwent coronary interventions, so relatively few patients would have been affected by the timing of coronary angiography or the procedure itself. In this trial, more than 60% of deaths were due to neurologic injury rather than cardiac complications.

Enriching the study population with patients with probable coronary disease might have led to a different result. A substudy analysis of patients over age 70 with a history of coronary disease showed they were more likely to benefit from immediate coronary angiography than were younger patients without a history of coronary disease.

Prioritizing interventions also had an impact on targeted temperature managemen, which also may have played into the results. The median time to achieve target temperature was 5.4 hours in the immediate angiography group and 4.7 hours in the delayed angiography group.

Additional insights may come from two ongoing clinical trials, ACCESS and DISCO (Direct or Subacute Coronary Angiography in Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest), may shed additional light on how interventions after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest affect patient outcomes.

Dr. Benjamin S. Abella is from the Center for Resuscitation Science and Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and Dr. David F. Gaieski is from the Department of Emergency Medicine at Jefferson Medical College. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (NEJM 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe1901651). Both authors declared grants, personal support and other support from private industry outside the submitted work.

Immediate angiography after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest does not improve survival compared to delaying angiography until neurologic recovery in patients with no evidence of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial involved 552 patients who had been successfully resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, without signs of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The study also excluded patients with shock and severe renal dysfunction, and was not blinded, so this may have influenced treatment decisions.

Patients were randomized either to immediate coronary angiography after resuscitation, while still unconscious, or delayed coronary angiography until they had recovered neurologically, which was generally after discharge from intensive care.

Overall, 97.1% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 64.9% of the delayed angiography group underwent coronary angiography, with the median time until angiography being 0.8 hours in the immediate group and 119.9 hours in the delayed group.

In the immediate angiography group, 3.4% of patients were found to have an acute coronary occlusion, while in the delayed group that figure was 7.6%. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 33% of the immediate angiography group and 24.2% of the delayed angiography group.

Survival rates at 90 days were not significantly different between the two groups; 64.5% of the immediate angiography group and 67.2% of the delayed angiography group survived to 90 days (OR 0.89, P = 0.51). The two groups also did not significantly differ in the secondary endpoints of survival with good cerebral performance or mild-to-moderate disability (62.9% vs. 64.4%).

“Our findings do not corroborate findings of previous observational studies, which showed a survival benefit with immediate coronary angiography in patients who had cardiac arrest without STEMI,” wrote Dr. Jorrit S. Lemkes, from the department of cardiology at Amsterdam University Medical Center VUmc, and co-authors. “This difference could be related to the observational nature of the previous studies, which may have resulted in selection bias that favored treating patients who had a presumed better prognosis with a strategy of immediate angiography.”

They also suggested the lack of benefit from early coronary angiography could relate to the fact that majority of those who died did so as a result of neurological complications, as has been seen in other studies of resuscitation.

The authors did note that the vast majority of patients in the study had stable coronary artery lesions, and only 5% showed thrombotic occlusions. They suggested this could explain their results, as percutaneous coronary intervention was not associated with improved outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery lesions – only in patients with acute thrombotic coronary occlusions.

However, they did see the suggestion of a treatment effect in patients over 70 years old and those with a history of coronary artery disease.

The study also revealed differences in subsequent treatment between patients who underwent immediate coronary angiography and those who had delayed angiography. Those in the delayed group were significantly more likely to be treated with salicylates or a P2Y12 inhibitor than those in the immediate angiography group.

“This observation illustrates how the result of immediate coronary angiography can influence treatment, since patients who did not have evidence of coronary artery disease on angiography do not require antiplatelet therapy,” the authors wrote.

Conversely, patients in the immediate angiography were more likely to receive a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. However the authors said these different strategies did not translate to any significant difference in major bleeding.

The COACT trial results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine simultaneously with Dr.Lemkes's presentation.

COACT was supported by the Netherlands Heart Institute, Biotronik and AstraZeneca. Two authors declared grants and support from the study supporters, both in and outside the context of the study. One author declared grants from private industry outside the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lemkes J et al. NEJM, 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816897

Immediate angiography after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest does not improve survival compared to delaying angiography until neurologic recovery in patients with no evidence of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest (COACT) trial involved 552 patients who had been successfully resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, without signs of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The study also excluded patients with shock and severe renal dysfunction, and was not blinded, so this may have influenced treatment decisions.

Patients were randomized either to immediate coronary angiography after resuscitation, while still unconscious, or delayed coronary angiography until they had recovered neurologically, which was generally after discharge from intensive care.

Overall, 97.1% of patients in the immediate angiography group and 64.9% of the delayed angiography group underwent coronary angiography, with the median time until angiography being 0.8 hours in the immediate group and 119.9 hours in the delayed group.

In the immediate angiography group, 3.4% of patients were found to have an acute coronary occlusion, while in the delayed group that figure was 7.6%. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 33% of the immediate angiography group and 24.2% of the delayed angiography group.

Survival rates at 90 days were not significantly different between the two groups; 64.5% of the immediate angiography group and 67.2% of the delayed angiography group survived to 90 days (OR 0.89, P = 0.51). The two groups also did not significantly differ in the secondary endpoints of survival with good cerebral performance or mild-to-moderate disability (62.9% vs. 64.4%).

“Our findings do not corroborate findings of previous observational studies, which showed a survival benefit with immediate coronary angiography in patients who had cardiac arrest without STEMI,” wrote Dr. Jorrit S. Lemkes, from the department of cardiology at Amsterdam University Medical Center VUmc, and co-authors. “This difference could be related to the observational nature of the previous studies, which may have resulted in selection bias that favored treating patients who had a presumed better prognosis with a strategy of immediate angiography.”

They also suggested the lack of benefit from early coronary angiography could relate to the fact that majority of those who died did so as a result of neurological complications, as has been seen in other studies of resuscitation.

The authors did note that the vast majority of patients in the study had stable coronary artery lesions, and only 5% showed thrombotic occlusions. They suggested this could explain their results, as percutaneous coronary intervention was not associated with improved outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery lesions – only in patients with acute thrombotic coronary occlusions.

However, they did see the suggestion of a treatment effect in patients over 70 years old and those with a history of coronary artery disease.

The study also revealed differences in subsequent treatment between patients who underwent immediate coronary angiography and those who had delayed angiography. Those in the delayed group were significantly more likely to be treated with salicylates or a P2Y12 inhibitor than those in the immediate angiography group.

“This observation illustrates how the result of immediate coronary angiography can influence treatment, since patients who did not have evidence of coronary artery disease on angiography do not require antiplatelet therapy,” the authors wrote.

Conversely, patients in the immediate angiography were more likely to receive a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. However the authors said these different strategies did not translate to any significant difference in major bleeding.

The COACT trial results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine simultaneously with Dr.Lemkes's presentation.

COACT was supported by the Netherlands Heart Institute, Biotronik and AstraZeneca. Two authors declared grants and support from the study supporters, both in and outside the context of the study. One author declared grants from private industry outside the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Lemkes J et al. NEJM, 2019, March 18. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816897

FROM ACC 19

Is a telehospitalist service right for you and your group?

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

Telemedicine “ripe for adoption” by hospitalists

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

For medical inpatients, the advent of virtual care began decades ago with telephones and the ability of physicians to give “verbal orders” while outside the hospital. It evolved into widespread adoption of pagers and is now ubiquitous through smart phones, texting, and HIPPA-compliant applications. In the past few years, inpatient telemedicine programs have been developed and studied including tele-ICU, telestroke, and now the telehospitalist.

Telemedicine is not new and has seen rapid adoption in the outpatient setting over the past decade,1 especially since the passing of telemedicine parity laws in 35 states to support equal reimbursement with face-to-face visits.2 In addition, 24 states have joined the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC).3 This voluntary program provides an expedited pathway to licensure for qualified physicians who practice in multiple states. The goal is to increase access to care for patients in underserved and rural areas and to allow easier consultation through telemedicine. Combined, these two federal initiatives have lowered two major barriers to entry for telemedicine: reimbursement and credentialing.

Only a handful of papers have been published on the telehospitalist model with one of the first in 2007 in The Hospitalist reporting on the intersection between tele-ICU and telehospitalist care.4 More recent work describes the implementation of a telehospitalist program between a large university hospitalist program and a rural, critical access hospital.5 A key goal of this program, developed by Dr. Ethan Kuperman and colleagues at the University of Iowa, was to keep patients at the critical access hospital that previously would have been transferred. This has obvious benefits for patients, the critical access hospital, and the local community. It also benefited the tertiary care referral center, which was dealing with high occupancy rates. Keeping lower acuity patients at the critical access hospital helps maintain access for more complex patients at the referral center. This same principle has applied to the use of the tele-ICU where lower acuity ICU patients could remain in the small, rural ICU, and only those patients who the intensivist believes would benefit from a higher level of care in a tertiary center would be transferred.

As this study and others have shown, telemedicine is ripe for adoption by hospitalists. The bigger question is how should it fit into the current model of hospital medicine? There are several different applications we are familiar with and each has unique considerations. The first model, as applied in the Kuperman paper, is for a larger hospitalist program to provide a telehospitalist service to a smaller, unaffiliated hospital (for example, critical access hospitals) that employs nurse practitioners or physician assistants on site but can’t recruit or retain full-time hospitalist coverage. In this collaborative model of care, the local provider performs the physical exam but provides care under the guidance and supervision of a hospital medicine specialist. This is expected to improve outcomes and bring the benefits of hospital medicine, including improved outcomes and decreased hospital spending, to smaller communities.6 In this model, the critical access hospital pays a fee for the service and retains the billing to third party payers.

A variation on that model would provide telehospitalist services to other hospitals within an existing health care network (such as Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain Healthcare, government hospitals) that have different financial models with incentives to collaborate. The Veterans Health Administration is embarking on a pilot through the VA Office of Rural Health to provide a telehospitalist service to small rural VA hospitals using the consultative model during the day with a nurse practitioner at the local site and physician backup from the emergency department. Although existing night cross-coverage will be maintained by a physician on call, this telehospitalist service may also evolve into providing cross-coverage on nights and weekends.

A third would be like a locum tenens model in which telehospitalist services are contracted for short periods of time when coverage is needed for vacations or staff shortages. A fourth model of telehospitalist care would be to international areas in need of hospitalist expertise, like a medical mission model but without the expense or time required to travel. Other models will likely evolve based on the demand for services, supply of hospitalists, changes in regulations, and reimbursement.

Another important consideration is how this will evolve for the practicing hospitalist. Will we have dedicated virtual hospitalists, akin to the “nocturnist” who covers nights and weekends? Or will working on the telehospitalist service be in the rotation of duties like many programs have with teaching and “nonteaching” services, medical consultation, and even transition clinics and emergency department triage responsibilities? It could serve as a lower-intensity service that can be staffed during office-based time that would include scholarly work, quality improvement, and administrative duties. If financially viable, it could be mutually beneficial for both the provider and recipient sides of telehospitalist care.

For any of these models to work, technical aspects must be ironed-out. It is indispensable for the provider to have remote access to the electronic health record for data review, documentation, and placing orders if needed. Adequate broadband for effective video connection, accompanied by the appropriate HIPPA-compliant software and hardware must be in place. Although highly specialized hardware has been developed, including remote stethoscopes and otoscopes, the key component is a good camera and video screen on each end of the interaction. Based upon prior experience with telemedicine programs, establishment of trusting relationships with the receiving hospital staff, physicians, and nurse practitioners is also critical. Optimally, the telehospitalist would have an opportunity to travel to the remote site to meet with the local care team and learn about the local resources and community. Many other operational and logistical issues need to be considered and will be supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine through publications, online resources, and national and regional meeting educational content on telehospitalist programs.

As hospital medicine adopts the telehospitalist model, it brings with it important considerations. First, is how we embrace the concept of the medical virtualist, a term used to describe physicians who spend the majority or all of their time caring for patients using a virtual medium.7 We find it difficult to imagine spending all or the majority of our time as a virtual hospitalist, but years ago many could not imagine someone being a full-time hospitalist or nocturnist. Some individuals will see this as a career opportunity that allows them to work as a hospitalist regardless of where they live or where the hospital is located. That has obvious advantages for both career choice and the provision of hospital medicine expertise to low-resourced or low-volume settings, such as rural or international locations and nights and weekends.

Second, the telehospitalist model will require professional standards, training, reimbursement and coding adjustments, hardware and software development, and managing patient expectations for care.

Lastly, hospitals, health care systems, hospitalist groups, and even individual hospitalists will have to determine how best to take advantage of this innovative model of care to provide the highest possible quality, in a cost-efficient manner, that supports professional satisfaction and development.

Dr. Kaboli and Dr. Gutierrez are based at the Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) at the Iowa City VA Healthcare System, the Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City, VA Office of Rural Health, and the department of internal medicine, University of Iowa, both in Iowa City.

References

1. Barnett ML et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147-9.

2. American Telemedicine Association State Policy Resource Center. 2018; http://www.americantelemed.org/main/policy-page/state-policy-resource-center. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

3. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact 2018; https://imlcc.org/. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

4. Hengehold D. The telehospitalist. The Hospitalist. 2007;7(July). https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/123381/telehospitalist. Accessed 2018 Dec 14.

5. Kuperman EF et al. The virtual hospitalist: A single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-63.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84(3):248-54.

7. Nochomovitz M, Sharma R. Is it time for a new medical specialty?: The medical virtualist. JAMA. 2018;319(5):437-8.

Infant survival rate after HCT remains flat

High rates of relapse and toxicities among infants who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (allo-HCT) contribute to survival rates that have remained largely unchanged from 2000-2014, based on a retrospective study of almost 2,500 cases.

Although survival rates improved from 2000 to 2004 among children aged 1 and younger who underwent allo-HCT for nonmalignant conditions, rates plateaued thereafter, reported lead author Suhag H. Parikh, MD, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and his colleagues. Still more disappointing, survival rates for infants with malignant conditions remained relatively flat throughout the 15-year study period.

For adult patients, allo-HCT survival rates have improved over time, but data for infants are rare. This is a concerning blind spot because infants are a particularly vulnerable population in the transplant setting.

“Infants may be at higher risk for toxicities than adults,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Pediatrics. “Although children are considered to have better tolerance to high-intensity or myeloablative conditioning regimens and perhaps better immune reconstitution owing to a functional thymus, infants may be at higher risk of transplant-associated complications.”

The present study involved 2,498 infants,1 year old or younger (median age 7 months), who underwent allo-HCT for malignant or nonmalignant conditions between 2000 and 2014. Information was drawn from The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), which consists of data from more than 450 transplant centers across the world.

The investigators assessed overall survival trends among infants undergoing allo-HCT; in addition, they analyzed factors contributing to mortality and rates of two major organ toxicities: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Cases were divided into 2 cohorts: malignant and nonmalignant. Time-analysis was divided into three periods: 2000-2004, 2005-2009, and 2010-2014.