User login

Large measles outbreak reported in Michigan

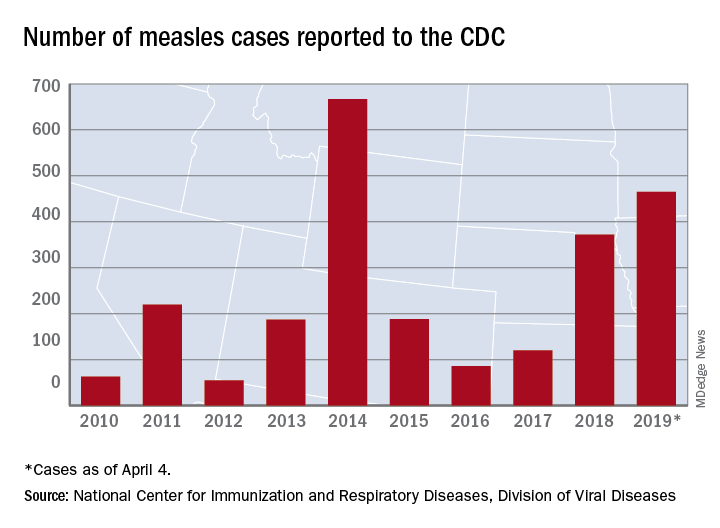

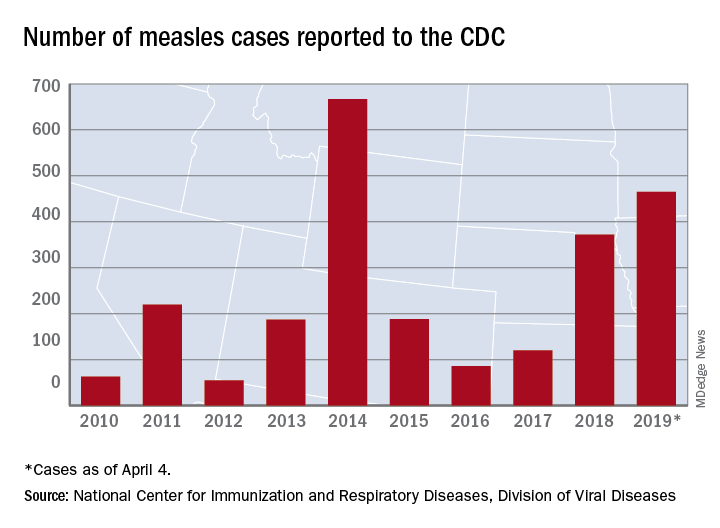

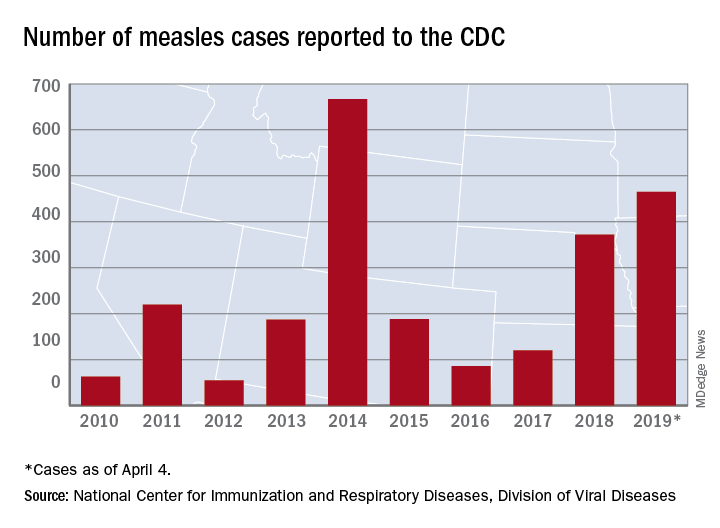

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

Fingernail Abnormalities After a Systemic Illness

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with painless fingernail detachment and cracks on her fingernails that had developed over the previous month. Her medical history was notable for an episode of Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2 months prior that required treatment with prednisone, IV immunoglobulin, etanercept, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine.

A physical examination revealed multiple fingernails on both hands that exhibited 4 mm of proximal painless nail detachment with cream-colored discoloration, friability, and horizontal splitting (Figure). New, healthy nail was visible beneath the affected areas. Toenails were not affected.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis

Based on the timing and characteristics of her nail detachment, the patient was diagnosed with onychomadesis, which is defined as painless detachment of the proximal nail plate from the nail matrix and nail bed after at least 40 days from an initial insult. Air beneath the detached nail plate causes a characteristic creamy-white discoloration. The severity of onychomadesis ranges from transverse furrows that affect a single nail without shedding, known as Beau lines, to multiple nails that are completely shed.1,2 Nail plate shedding is typical because the nail matrix, the site of stem cells and the most proximal portion of the nail apparatus, is damaged and transiently arrested.

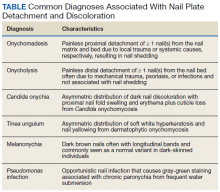

Various etiologies can halt nail plate production abruptly within the matrix. These typically manifest ≥ 40 days after the initial insult (the length of time for a fingernail to emerge from the proximal nail fold).2 The annual incidence of these etiologies ranges from approximately 1 per 1 million people for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare cause of onychomadesis, to 1 per 10 people for onychomycosis, one of the more common causes of onychomadesis.3 The Table compares the characteristics of the diagnoses that are most commonly associated with nail detachment and discoloration.

When a single nail is affected, the etiology of onychomadesis usually is primary and local, including mechanical nail trauma and fungal nail infections (onychomycosis).1,2 Candida onychia is onychomycosis caused by Candida species typically Candida albicans, which result in localized nail darkening, chronic inflammation of the paronychial skin, and cuticle loss. The infection favors immunocompromised people; coinfections are common, and onychomadesis or onycholysis can occur. Unlike onychomadesis, onycholysis is defined by painless detachment of the distal nail plate from the nail bed, but nail shedding typically does not occur because the nail matrix is spared. The preferred treatment for Candida onychia is oral itraconazole, and guided screenings for immunodeficiencies and endocrinopathies, especially diabetes mellitus, should be completed.3,4

Tinea unguium is another form of onychomycosis, but it is caused by dermatophytes, typically Trichophyton rubrum or Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which produce white and yellow nail discoloration followed by distal to proximal nail thickening and softening. Infection usually begins in toenails and demonstrates variable involvement in each nail as well as asymmetric distribution among digits.3 This condition also may eventuate in onychomadesis or onycholysis. Debridement followed by oral terbinafine is the treatment of choice.4

Two other causes of localized nail discoloration with or without nail detachment include melanonychia and nail bed infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). Melanonychia can be linear or diffuse brown discoloration of 1 or more nails caused by melanin deposition. Either pattern is a common finding in dark-skinned people, especially by age 50 years, but melanocyte hyperplasia should be excluded in all individuals along with drug adverse effects, exogenous pigments, infections, and systemic diseases.3,5 P aeruginosa produces pyocyanin, the green pigment responsible for the discoloration seen in this opportunistic infection often localized to a single nail. Prior maceration of the nail apparatus by repeated water submersion is common among affected individuals. Avoidance of submerging fingernails in liquids followed by nail debridement and oral antipseudomonal antibiotics is the preferred treatment course.3

The etiology is usually secondary and systemic when multiple nails demonstrate onychomadesis, but the exact pathophysiology is poorly understood. One of the most studied infectious etiologies of onychomadesis is hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), which typically affects children aged < 10 years. Parents often will recall their child being ill 1 to 2 months prior to the nail findings. Scarlet fever and varicella also can result in onychomadesis. Although not common systemic causes, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis can trigger onychomadesis of multiple nails that usually resolves in several months, but other nail deformities often persist.2,6 Onycholysis also can accompany this finding.7 Autoimmune etiologies of onychomadesis include alopecia areata and pemphigus vulgaris. Inciting medications that are toxic to the nail matrix include chemotherapy agents, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lithium, and azithromycin. Rare congenital disorders and birth trauma also can present with onychomadesis of multiple nails during infancy.2

Systemic etiologies typically affect fingernails more than toenails because of the faster growth rate of fingernails. Once the source of onychomadesis is controlled or eradicated, complete regrowth of fingernails can take from 4 to 6 months. Toenails can take twice as long and older age increases all regrowth periods.5

Our patient was treated with analgesics until her mucosal surfaces fully healed, and topical emollients and keratolytics were used to soften eschars from previous blisters and prevent further scar formation. Her affected fingernails shed and regrew after 6 months without additional interventions.

Conclusion

Although Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare cause of onychomadesis, and the pathophysiology of this sequela is poorly understood, this case illustrates a common nail abnormality with multiple potential etiologies that are discerned by an accurate history and thorough exam. In the absence of decorative nail polish, nails can be easily examined to provide helpful clues for past injuries or underlying diseases. An understanding of nail growth mechanics and associated terminology reveals the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of proximal vs distal nail detachment, the hue of nail discoloration, as well as single vs multiple affected nails.

Onychomadesis in single nails should prompt questions about nail trauma or risk factors for fungal infections. Depending on the etiology, manual activities need to be adjusted, or antifungals need to be initiated while investigating for an immunocompromised state. Onychomadesis in multiple nails in children should raise suspicion for HFMD or even birth trauma and congenital disorders. Multiple affected nails in adults should prompt guided questions for autoimmune diseases and inciting medications. For onycholysis, trauma, psoriasis, or certain infections should be the target. Green nails are easily recognized and treated with a defined regiment, whereas dark nails should be examined closely to differentiate Candida onychia from melanonychia. Whether from a rare cause in an adult to a common illness in a child, primary care providers have sufficient expertise to diagnose and treat various nail disorders and reassure worried patients and parents with an understanding of nail regrowth.

1. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Shedding light on onychomadesis. Cutis. 2017;99(1):33-36.

2. Hardin J, Haber RM. Oncyhomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(3):592-596.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. du Vivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

5. Shemer A, Daniel CR III. Common nail disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(5):578-586.

6. Acharya S, Balachandran C. Onychomadesis in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62(4):264-265.

7. Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):187.e1-e16.

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with painless fingernail detachment and cracks on her fingernails that had developed over the previous month. Her medical history was notable for an episode of Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2 months prior that required treatment with prednisone, IV immunoglobulin, etanercept, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine.

A physical examination revealed multiple fingernails on both hands that exhibited 4 mm of proximal painless nail detachment with cream-colored discoloration, friability, and horizontal splitting (Figure). New, healthy nail was visible beneath the affected areas. Toenails were not affected.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis

Based on the timing and characteristics of her nail detachment, the patient was diagnosed with onychomadesis, which is defined as painless detachment of the proximal nail plate from the nail matrix and nail bed after at least 40 days from an initial insult. Air beneath the detached nail plate causes a characteristic creamy-white discoloration. The severity of onychomadesis ranges from transverse furrows that affect a single nail without shedding, known as Beau lines, to multiple nails that are completely shed.1,2 Nail plate shedding is typical because the nail matrix, the site of stem cells and the most proximal portion of the nail apparatus, is damaged and transiently arrested.

Various etiologies can halt nail plate production abruptly within the matrix. These typically manifest ≥ 40 days after the initial insult (the length of time for a fingernail to emerge from the proximal nail fold).2 The annual incidence of these etiologies ranges from approximately 1 per 1 million people for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare cause of onychomadesis, to 1 per 10 people for onychomycosis, one of the more common causes of onychomadesis.3 The Table compares the characteristics of the diagnoses that are most commonly associated with nail detachment and discoloration.

When a single nail is affected, the etiology of onychomadesis usually is primary and local, including mechanical nail trauma and fungal nail infections (onychomycosis).1,2 Candida onychia is onychomycosis caused by Candida species typically Candida albicans, which result in localized nail darkening, chronic inflammation of the paronychial skin, and cuticle loss. The infection favors immunocompromised people; coinfections are common, and onychomadesis or onycholysis can occur. Unlike onychomadesis, onycholysis is defined by painless detachment of the distal nail plate from the nail bed, but nail shedding typically does not occur because the nail matrix is spared. The preferred treatment for Candida onychia is oral itraconazole, and guided screenings for immunodeficiencies and endocrinopathies, especially diabetes mellitus, should be completed.3,4

Tinea unguium is another form of onychomycosis, but it is caused by dermatophytes, typically Trichophyton rubrum or Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which produce white and yellow nail discoloration followed by distal to proximal nail thickening and softening. Infection usually begins in toenails and demonstrates variable involvement in each nail as well as asymmetric distribution among digits.3 This condition also may eventuate in onychomadesis or onycholysis. Debridement followed by oral terbinafine is the treatment of choice.4

Two other causes of localized nail discoloration with or without nail detachment include melanonychia and nail bed infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). Melanonychia can be linear or diffuse brown discoloration of 1 or more nails caused by melanin deposition. Either pattern is a common finding in dark-skinned people, especially by age 50 years, but melanocyte hyperplasia should be excluded in all individuals along with drug adverse effects, exogenous pigments, infections, and systemic diseases.3,5 P aeruginosa produces pyocyanin, the green pigment responsible for the discoloration seen in this opportunistic infection often localized to a single nail. Prior maceration of the nail apparatus by repeated water submersion is common among affected individuals. Avoidance of submerging fingernails in liquids followed by nail debridement and oral antipseudomonal antibiotics is the preferred treatment course.3

The etiology is usually secondary and systemic when multiple nails demonstrate onychomadesis, but the exact pathophysiology is poorly understood. One of the most studied infectious etiologies of onychomadesis is hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), which typically affects children aged < 10 years. Parents often will recall their child being ill 1 to 2 months prior to the nail findings. Scarlet fever and varicella also can result in onychomadesis. Although not common systemic causes, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis can trigger onychomadesis of multiple nails that usually resolves in several months, but other nail deformities often persist.2,6 Onycholysis also can accompany this finding.7 Autoimmune etiologies of onychomadesis include alopecia areata and pemphigus vulgaris. Inciting medications that are toxic to the nail matrix include chemotherapy agents, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lithium, and azithromycin. Rare congenital disorders and birth trauma also can present with onychomadesis of multiple nails during infancy.2

Systemic etiologies typically affect fingernails more than toenails because of the faster growth rate of fingernails. Once the source of onychomadesis is controlled or eradicated, complete regrowth of fingernails can take from 4 to 6 months. Toenails can take twice as long and older age increases all regrowth periods.5

Our patient was treated with analgesics until her mucosal surfaces fully healed, and topical emollients and keratolytics were used to soften eschars from previous blisters and prevent further scar formation. Her affected fingernails shed and regrew after 6 months without additional interventions.

Conclusion

Although Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare cause of onychomadesis, and the pathophysiology of this sequela is poorly understood, this case illustrates a common nail abnormality with multiple potential etiologies that are discerned by an accurate history and thorough exam. In the absence of decorative nail polish, nails can be easily examined to provide helpful clues for past injuries or underlying diseases. An understanding of nail growth mechanics and associated terminology reveals the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of proximal vs distal nail detachment, the hue of nail discoloration, as well as single vs multiple affected nails.

Onychomadesis in single nails should prompt questions about nail trauma or risk factors for fungal infections. Depending on the etiology, manual activities need to be adjusted, or antifungals need to be initiated while investigating for an immunocompromised state. Onychomadesis in multiple nails in children should raise suspicion for HFMD or even birth trauma and congenital disorders. Multiple affected nails in adults should prompt guided questions for autoimmune diseases and inciting medications. For onycholysis, trauma, psoriasis, or certain infections should be the target. Green nails are easily recognized and treated with a defined regiment, whereas dark nails should be examined closely to differentiate Candida onychia from melanonychia. Whether from a rare cause in an adult to a common illness in a child, primary care providers have sufficient expertise to diagnose and treat various nail disorders and reassure worried patients and parents with an understanding of nail regrowth.

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with painless fingernail detachment and cracks on her fingernails that had developed over the previous month. Her medical history was notable for an episode of Stevens-Johnson syndrome 2 months prior that required treatment with prednisone, IV immunoglobulin, etanercept, acetaminophen, and diphenhydramine.

A physical examination revealed multiple fingernails on both hands that exhibited 4 mm of proximal painless nail detachment with cream-colored discoloration, friability, and horizontal splitting (Figure). New, healthy nail was visible beneath the affected areas. Toenails were not affected.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis

Based on the timing and characteristics of her nail detachment, the patient was diagnosed with onychomadesis, which is defined as painless detachment of the proximal nail plate from the nail matrix and nail bed after at least 40 days from an initial insult. Air beneath the detached nail plate causes a characteristic creamy-white discoloration. The severity of onychomadesis ranges from transverse furrows that affect a single nail without shedding, known as Beau lines, to multiple nails that are completely shed.1,2 Nail plate shedding is typical because the nail matrix, the site of stem cells and the most proximal portion of the nail apparatus, is damaged and transiently arrested.

Various etiologies can halt nail plate production abruptly within the matrix. These typically manifest ≥ 40 days after the initial insult (the length of time for a fingernail to emerge from the proximal nail fold).2 The annual incidence of these etiologies ranges from approximately 1 per 1 million people for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a rare cause of onychomadesis, to 1 per 10 people for onychomycosis, one of the more common causes of onychomadesis.3 The Table compares the characteristics of the diagnoses that are most commonly associated with nail detachment and discoloration.

When a single nail is affected, the etiology of onychomadesis usually is primary and local, including mechanical nail trauma and fungal nail infections (onychomycosis).1,2 Candida onychia is onychomycosis caused by Candida species typically Candida albicans, which result in localized nail darkening, chronic inflammation of the paronychial skin, and cuticle loss. The infection favors immunocompromised people; coinfections are common, and onychomadesis or onycholysis can occur. Unlike onychomadesis, onycholysis is defined by painless detachment of the distal nail plate from the nail bed, but nail shedding typically does not occur because the nail matrix is spared. The preferred treatment for Candida onychia is oral itraconazole, and guided screenings for immunodeficiencies and endocrinopathies, especially diabetes mellitus, should be completed.3,4

Tinea unguium is another form of onychomycosis, but it is caused by dermatophytes, typically Trichophyton rubrum or Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which produce white and yellow nail discoloration followed by distal to proximal nail thickening and softening. Infection usually begins in toenails and demonstrates variable involvement in each nail as well as asymmetric distribution among digits.3 This condition also may eventuate in onychomadesis or onycholysis. Debridement followed by oral terbinafine is the treatment of choice.4

Two other causes of localized nail discoloration with or without nail detachment include melanonychia and nail bed infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P aeruginosa). Melanonychia can be linear or diffuse brown discoloration of 1 or more nails caused by melanin deposition. Either pattern is a common finding in dark-skinned people, especially by age 50 years, but melanocyte hyperplasia should be excluded in all individuals along with drug adverse effects, exogenous pigments, infections, and systemic diseases.3,5 P aeruginosa produces pyocyanin, the green pigment responsible for the discoloration seen in this opportunistic infection often localized to a single nail. Prior maceration of the nail apparatus by repeated water submersion is common among affected individuals. Avoidance of submerging fingernails in liquids followed by nail debridement and oral antipseudomonal antibiotics is the preferred treatment course.3

The etiology is usually secondary and systemic when multiple nails demonstrate onychomadesis, but the exact pathophysiology is poorly understood. One of the most studied infectious etiologies of onychomadesis is hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), which typically affects children aged < 10 years. Parents often will recall their child being ill 1 to 2 months prior to the nail findings. Scarlet fever and varicella also can result in onychomadesis. Although not common systemic causes, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis can trigger onychomadesis of multiple nails that usually resolves in several months, but other nail deformities often persist.2,6 Onycholysis also can accompany this finding.7 Autoimmune etiologies of onychomadesis include alopecia areata and pemphigus vulgaris. Inciting medications that are toxic to the nail matrix include chemotherapy agents, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lithium, and azithromycin. Rare congenital disorders and birth trauma also can present with onychomadesis of multiple nails during infancy.2

Systemic etiologies typically affect fingernails more than toenails because of the faster growth rate of fingernails. Once the source of onychomadesis is controlled or eradicated, complete regrowth of fingernails can take from 4 to 6 months. Toenails can take twice as long and older age increases all regrowth periods.5

Our patient was treated with analgesics until her mucosal surfaces fully healed, and topical emollients and keratolytics were used to soften eschars from previous blisters and prevent further scar formation. Her affected fingernails shed and regrew after 6 months without additional interventions.

Conclusion

Although Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare cause of onychomadesis, and the pathophysiology of this sequela is poorly understood, this case illustrates a common nail abnormality with multiple potential etiologies that are discerned by an accurate history and thorough exam. In the absence of decorative nail polish, nails can be easily examined to provide helpful clues for past injuries or underlying diseases. An understanding of nail growth mechanics and associated terminology reveals the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of proximal vs distal nail detachment, the hue of nail discoloration, as well as single vs multiple affected nails.

Onychomadesis in single nails should prompt questions about nail trauma or risk factors for fungal infections. Depending on the etiology, manual activities need to be adjusted, or antifungals need to be initiated while investigating for an immunocompromised state. Onychomadesis in multiple nails in children should raise suspicion for HFMD or even birth trauma and congenital disorders. Multiple affected nails in adults should prompt guided questions for autoimmune diseases and inciting medications. For onycholysis, trauma, psoriasis, or certain infections should be the target. Green nails are easily recognized and treated with a defined regiment, whereas dark nails should be examined closely to differentiate Candida onychia from melanonychia. Whether from a rare cause in an adult to a common illness in a child, primary care providers have sufficient expertise to diagnose and treat various nail disorders and reassure worried patients and parents with an understanding of nail regrowth.

1. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Shedding light on onychomadesis. Cutis. 2017;99(1):33-36.

2. Hardin J, Haber RM. Oncyhomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(3):592-596.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. du Vivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

5. Shemer A, Daniel CR III. Common nail disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(5):578-586.

6. Acharya S, Balachandran C. Onychomadesis in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62(4):264-265.

7. Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):187.e1-e16.

1. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Shedding light on onychomadesis. Cutis. 2017;99(1):33-36.

2. Hardin J, Haber RM. Oncyhomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(3):592-596.

3. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

4. du Vivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

5. Shemer A, Daniel CR III. Common nail disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(5):578-586.

6. Acharya S, Balachandran C. Onychomadesis in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62(4):264-265.

7. Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):187.e1-e16.

Clinical Pharmacist Credentialing and Privileging: A Process for Ensuring High-Quality Patient Care

The Red Lake Indian Health Service (IHS) health care facility is in north-central Minnesota within the Red Lake Nation. The facility supports primary care, emergency, urgent care, pharmacy, inpatient, optometry, dental, radiology, laboratory, physical therapy, and behavioral health services to about 10,000 Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indian patients. The Red Lake pharmacy provides inpatient and outpatient medication services and pharmacist-managed clinical patient care.

In 2013, the Red Lake IHS medical staff endorsed the implementation of comprehensive clinical pharmacy services to increase health care access and optimize clinical outcomes for patients. During the evolution of pharmacy-based patient-centric care, the clinical programs offered by Red Lake IHS pharmacy expanded from 1 anticoagulation clinic to multiple advanced-practice clinical pharmacy services. This included pharmacy primary care, medication-assisted therapy, naloxone, hepatitis C, and behavioral health medication management clinics.

The immense clinical growth of the pharmacy department demonstrated a need to assess and monitor pharmacist competency to ensure the delivery of quality patient care. Essential quality improvement processes were lacking. To fill these quality improvement gaps, a robust pharmacist credentialing and privileging program was implemented in 2015.

Patient Care

As efforts within health care establishments across the US focus on the delivery of efficient, high-quality, affordable health care, pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing patient care within expanded clinical roles.1-8 Many clinical pharmacy models have evolved into interdisciplinary approaches to care.9 Within these models, abiding by state and federal laws, pharmacists practice under the indirect supervision of licensed independent practitioners (LIPs), such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.8 Under collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), patients are initially diagnosed by LIPs, then referred to clinical pharmacists for therapeutic management.5,7

Clinical pharmacist functions encompass comprehensive medication management (ie, prescribing, monitoring, and adjustment of medications), nonpharmacologic guidance, and coordination of care. Interdisciplinary collaboration allows pharmacists opportunities to provide direct patient care or consultations by telecommunication in many different clinical environments, including disease management, primary care, or specialty care. Pharmacists may manage chronic or acute illnesses associated with endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or other systems.

Pharmacists may also provide comprehensive medication review services, such as medication therapy management (MTM), transitions of care, or chronic care management. Examples of specialized areas include psychiatric, opioid use disorder, palliative care, infectious disease, chronic pain, or oncology services. For hospitalized patients, pharmacists may monitor pharmacokinetics and adjust dosing, transition patients from IV to oral medications, or complete medication reconciliation.10 Within these clinical roles, pharmacists assist in providing patient care during shortages of other health care providers (HCPs), improve patient outcomes, decrease health care-associated costs by preventing emergency department and hospital admissions or readmissions, increase access to patient care, and increase revenue through pharmacist-managed clinics and services.11

Pharmacist Credentialing

With the advancement of modern clinical pharmacy practice, many pharmacists have undertaken responsibilities to fulfill the complex duties of clinical care and diverse patient situations, but with few or no requirements to prove initial or ongoing clinical competency.2 Traditionally, pharmacist credentialing is limited to a onetime or periodic review of education and licensure, with little to no involvement in privileging and ongoing monitoring of clinical proficiency.10 These quality assurance disparities can be met and satisfied through credentialing and privileging processes. Credentialing and privileging are systematic, evidence-based processes that provide validation to HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified to practice clinically. 2,9 According to the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, clinical pharmacists should be held accountable for demonstrating competency and providing quality care through credentialing and privileging, as required for other HCPs.2,12

Credentialing and recredentialing is a primary source verification process. These processes ensure that there are no license restrictions or revocations; certifications are current; mandatory courses, certificates, and continuing education are complete; training and orientation are satisfactory; and any disciplinary action, malpractice claims, or history of impairment is reported. Privileging is the review of credentials and evaluation of clinical training and competence by the Clinical Director and Medical Executive Committee to determine whether a clinical pharmacist is competent to practice within requested privileges.11

Credentialing and privileging processes are designed not only to initially confirm that a pharmacist is competent to practice clinically, but also monitor ongoing performance.2,13 Participation in professional practice evaluations, which includes peer reviews, ongoing professional practice evaluations, and focused professional practice evaluations, is required for all credentialed and privileged practitioners. These evaluations are used to identify, assess, and correct unsatisfactory trends. Individual practices, documentation, and processes are evaluated against existing department standards (eg, CPAs, policies, processes)11,13 The results of individual professional practice evaluations are reviewed with practitioners on a regular basis and performance improvement plans implemented as needed.

Since 2015, 17 pharmacists at the Red Lake IHS health care facility have been granted membership to the medical staff as credentialed and privileged practitioners. In a retrospective review of professional practice evaluations by the Red Lake IHS pharmacy clinical coordinator, 971 outpatient clinical peer reviews, including the evaluation of 21,526 peer-review elements were completed by pharmacists from fiscal year 2015 through 2018. Peer-review elements assessed

Conclusion

Pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing effective, cost-efficient, and accessible clinical services by continuing to move toward expanding and evolving roles within comprehensive, patient-centered clinical pharmacy practice settings.5,6 Multifaceted clinical responsibilities associated with health care delivery necessitate assessment and monitoring of pharmacist performance. Credentialing and privileging is an established and trusted systematic process that assures HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified and competent to practice clinically.2,4,12 Implementation of professional practice evaluations suggest improved staff compliance with visit documentation, patient care standards, and clinic processes required by CPAs, policies, and department standards to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality patient care.

1. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed March 15, 2019.

2. Rouse MJ, Vlasses PH, Webb CE; Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists: a resource paper from the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(21):e109-e118.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769.

4. Blair MM, Carmichael J, Young E, Thrasher K; Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Pharmacist privileging in a health system: report of the Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(22):2373-2381.

5. Claxton KI, Wojtal P. Design and implementation of a credentialing and privileging model for ambulatory care pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(17):1627-1632.

6. Jordan TA, Hennenfent JA, Lewin JJ III, Nesbit TW, Weber R. Elevating pharmacists’ scope of practice through a health-system clinical privileging process. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1395-1405.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Collaborative practice agreements and pharmacists’ patient care services: a resource for doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and other providers. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/Translational_Tools_Providers.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, Albanese NP, Rouse MJ. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of practitioners and pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2010;50(2):e35-e69.

9. Philip B, Weber R. Enhancing pharmacy practice models through pharmacists’ privileging. Hosp Pharm. 2013; 48(2):160-165.

10. Galt KA. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(7):661-670.

11. Smith ML, Gemelas MF; US Public Health Service; Indian Health Service. Indian Health Service medical staff credentialing and privileging guide. https://www.ihs.gov/riskmanagement/includes/themes/newihstheme/display_objects/documents/IHS-Medical-Staff-Credentialing-and-Privileging-Guide.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed March 15, 2019.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Indian health manual: medical credentials and privileges review process. https://www.ihs.gov/ihm/pc/part-3/p3c1. Accessed March 15, 2019.

13. Holley SL, Ketel C. Ongoing professional practice evaluation and focused professional practice evaluation: an overview for advanced practice clinicians. J Midwifery Women Health. 2014;59(4):452-459.

The Red Lake Indian Health Service (IHS) health care facility is in north-central Minnesota within the Red Lake Nation. The facility supports primary care, emergency, urgent care, pharmacy, inpatient, optometry, dental, radiology, laboratory, physical therapy, and behavioral health services to about 10,000 Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indian patients. The Red Lake pharmacy provides inpatient and outpatient medication services and pharmacist-managed clinical patient care.

In 2013, the Red Lake IHS medical staff endorsed the implementation of comprehensive clinical pharmacy services to increase health care access and optimize clinical outcomes for patients. During the evolution of pharmacy-based patient-centric care, the clinical programs offered by Red Lake IHS pharmacy expanded from 1 anticoagulation clinic to multiple advanced-practice clinical pharmacy services. This included pharmacy primary care, medication-assisted therapy, naloxone, hepatitis C, and behavioral health medication management clinics.

The immense clinical growth of the pharmacy department demonstrated a need to assess and monitor pharmacist competency to ensure the delivery of quality patient care. Essential quality improvement processes were lacking. To fill these quality improvement gaps, a robust pharmacist credentialing and privileging program was implemented in 2015.

Patient Care

As efforts within health care establishments across the US focus on the delivery of efficient, high-quality, affordable health care, pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing patient care within expanded clinical roles.1-8 Many clinical pharmacy models have evolved into interdisciplinary approaches to care.9 Within these models, abiding by state and federal laws, pharmacists practice under the indirect supervision of licensed independent practitioners (LIPs), such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.8 Under collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), patients are initially diagnosed by LIPs, then referred to clinical pharmacists for therapeutic management.5,7

Clinical pharmacist functions encompass comprehensive medication management (ie, prescribing, monitoring, and adjustment of medications), nonpharmacologic guidance, and coordination of care. Interdisciplinary collaboration allows pharmacists opportunities to provide direct patient care or consultations by telecommunication in many different clinical environments, including disease management, primary care, or specialty care. Pharmacists may manage chronic or acute illnesses associated with endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or other systems.

Pharmacists may also provide comprehensive medication review services, such as medication therapy management (MTM), transitions of care, or chronic care management. Examples of specialized areas include psychiatric, opioid use disorder, palliative care, infectious disease, chronic pain, or oncology services. For hospitalized patients, pharmacists may monitor pharmacokinetics and adjust dosing, transition patients from IV to oral medications, or complete medication reconciliation.10 Within these clinical roles, pharmacists assist in providing patient care during shortages of other health care providers (HCPs), improve patient outcomes, decrease health care-associated costs by preventing emergency department and hospital admissions or readmissions, increase access to patient care, and increase revenue through pharmacist-managed clinics and services.11

Pharmacist Credentialing

With the advancement of modern clinical pharmacy practice, many pharmacists have undertaken responsibilities to fulfill the complex duties of clinical care and diverse patient situations, but with few or no requirements to prove initial or ongoing clinical competency.2 Traditionally, pharmacist credentialing is limited to a onetime or periodic review of education and licensure, with little to no involvement in privileging and ongoing monitoring of clinical proficiency.10 These quality assurance disparities can be met and satisfied through credentialing and privileging processes. Credentialing and privileging are systematic, evidence-based processes that provide validation to HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified to practice clinically. 2,9 According to the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, clinical pharmacists should be held accountable for demonstrating competency and providing quality care through credentialing and privileging, as required for other HCPs.2,12

Credentialing and recredentialing is a primary source verification process. These processes ensure that there are no license restrictions or revocations; certifications are current; mandatory courses, certificates, and continuing education are complete; training and orientation are satisfactory; and any disciplinary action, malpractice claims, or history of impairment is reported. Privileging is the review of credentials and evaluation of clinical training and competence by the Clinical Director and Medical Executive Committee to determine whether a clinical pharmacist is competent to practice within requested privileges.11

Credentialing and privileging processes are designed not only to initially confirm that a pharmacist is competent to practice clinically, but also monitor ongoing performance.2,13 Participation in professional practice evaluations, which includes peer reviews, ongoing professional practice evaluations, and focused professional practice evaluations, is required for all credentialed and privileged practitioners. These evaluations are used to identify, assess, and correct unsatisfactory trends. Individual practices, documentation, and processes are evaluated against existing department standards (eg, CPAs, policies, processes)11,13 The results of individual professional practice evaluations are reviewed with practitioners on a regular basis and performance improvement plans implemented as needed.

Since 2015, 17 pharmacists at the Red Lake IHS health care facility have been granted membership to the medical staff as credentialed and privileged practitioners. In a retrospective review of professional practice evaluations by the Red Lake IHS pharmacy clinical coordinator, 971 outpatient clinical peer reviews, including the evaluation of 21,526 peer-review elements were completed by pharmacists from fiscal year 2015 through 2018. Peer-review elements assessed

Conclusion

Pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing effective, cost-efficient, and accessible clinical services by continuing to move toward expanding and evolving roles within comprehensive, patient-centered clinical pharmacy practice settings.5,6 Multifaceted clinical responsibilities associated with health care delivery necessitate assessment and monitoring of pharmacist performance. Credentialing and privileging is an established and trusted systematic process that assures HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified and competent to practice clinically.2,4,12 Implementation of professional practice evaluations suggest improved staff compliance with visit documentation, patient care standards, and clinic processes required by CPAs, policies, and department standards to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality patient care.

The Red Lake Indian Health Service (IHS) health care facility is in north-central Minnesota within the Red Lake Nation. The facility supports primary care, emergency, urgent care, pharmacy, inpatient, optometry, dental, radiology, laboratory, physical therapy, and behavioral health services to about 10,000 Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indian patients. The Red Lake pharmacy provides inpatient and outpatient medication services and pharmacist-managed clinical patient care.

In 2013, the Red Lake IHS medical staff endorsed the implementation of comprehensive clinical pharmacy services to increase health care access and optimize clinical outcomes for patients. During the evolution of pharmacy-based patient-centric care, the clinical programs offered by Red Lake IHS pharmacy expanded from 1 anticoagulation clinic to multiple advanced-practice clinical pharmacy services. This included pharmacy primary care, medication-assisted therapy, naloxone, hepatitis C, and behavioral health medication management clinics.

The immense clinical growth of the pharmacy department demonstrated a need to assess and monitor pharmacist competency to ensure the delivery of quality patient care. Essential quality improvement processes were lacking. To fill these quality improvement gaps, a robust pharmacist credentialing and privileging program was implemented in 2015.

Patient Care

As efforts within health care establishments across the US focus on the delivery of efficient, high-quality, affordable health care, pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing patient care within expanded clinical roles.1-8 Many clinical pharmacy models have evolved into interdisciplinary approaches to care.9 Within these models, abiding by state and federal laws, pharmacists practice under the indirect supervision of licensed independent practitioners (LIPs), such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants.8 Under collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), patients are initially diagnosed by LIPs, then referred to clinical pharmacists for therapeutic management.5,7

Clinical pharmacist functions encompass comprehensive medication management (ie, prescribing, monitoring, and adjustment of medications), nonpharmacologic guidance, and coordination of care. Interdisciplinary collaboration allows pharmacists opportunities to provide direct patient care or consultations by telecommunication in many different clinical environments, including disease management, primary care, or specialty care. Pharmacists may manage chronic or acute illnesses associated with endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or other systems.

Pharmacists may also provide comprehensive medication review services, such as medication therapy management (MTM), transitions of care, or chronic care management. Examples of specialized areas include psychiatric, opioid use disorder, palliative care, infectious disease, chronic pain, or oncology services. For hospitalized patients, pharmacists may monitor pharmacokinetics and adjust dosing, transition patients from IV to oral medications, or complete medication reconciliation.10 Within these clinical roles, pharmacists assist in providing patient care during shortages of other health care providers (HCPs), improve patient outcomes, decrease health care-associated costs by preventing emergency department and hospital admissions or readmissions, increase access to patient care, and increase revenue through pharmacist-managed clinics and services.11

Pharmacist Credentialing

With the advancement of modern clinical pharmacy practice, many pharmacists have undertaken responsibilities to fulfill the complex duties of clinical care and diverse patient situations, but with few or no requirements to prove initial or ongoing clinical competency.2 Traditionally, pharmacist credentialing is limited to a onetime or periodic review of education and licensure, with little to no involvement in privileging and ongoing monitoring of clinical proficiency.10 These quality assurance disparities can be met and satisfied through credentialing and privileging processes. Credentialing and privileging are systematic, evidence-based processes that provide validation to HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified to practice clinically. 2,9 According to the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, clinical pharmacists should be held accountable for demonstrating competency and providing quality care through credentialing and privileging, as required for other HCPs.2,12

Credentialing and recredentialing is a primary source verification process. These processes ensure that there are no license restrictions or revocations; certifications are current; mandatory courses, certificates, and continuing education are complete; training and orientation are satisfactory; and any disciplinary action, malpractice claims, or history of impairment is reported. Privileging is the review of credentials and evaluation of clinical training and competence by the Clinical Director and Medical Executive Committee to determine whether a clinical pharmacist is competent to practice within requested privileges.11

Credentialing and privileging processes are designed not only to initially confirm that a pharmacist is competent to practice clinically, but also monitor ongoing performance.2,13 Participation in professional practice evaluations, which includes peer reviews, ongoing professional practice evaluations, and focused professional practice evaluations, is required for all credentialed and privileged practitioners. These evaluations are used to identify, assess, and correct unsatisfactory trends. Individual practices, documentation, and processes are evaluated against existing department standards (eg, CPAs, policies, processes)11,13 The results of individual professional practice evaluations are reviewed with practitioners on a regular basis and performance improvement plans implemented as needed.

Since 2015, 17 pharmacists at the Red Lake IHS health care facility have been granted membership to the medical staff as credentialed and privileged practitioners. In a retrospective review of professional practice evaluations by the Red Lake IHS pharmacy clinical coordinator, 971 outpatient clinical peer reviews, including the evaluation of 21,526 peer-review elements were completed by pharmacists from fiscal year 2015 through 2018. Peer-review elements assessed

Conclusion

Pharmacists have become increasingly instrumental in providing effective, cost-efficient, and accessible clinical services by continuing to move toward expanding and evolving roles within comprehensive, patient-centered clinical pharmacy practice settings.5,6 Multifaceted clinical responsibilities associated with health care delivery necessitate assessment and monitoring of pharmacist performance. Credentialing and privileging is an established and trusted systematic process that assures HCPs, employers, and patients that pharmacists are qualified and competent to practice clinically.2,4,12 Implementation of professional practice evaluations suggest improved staff compliance with visit documentation, patient care standards, and clinic processes required by CPAs, policies, and department standards to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality patient care.

1. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed March 15, 2019.

2. Rouse MJ, Vlasses PH, Webb CE; Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists: a resource paper from the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(21):e109-e118.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769.

4. Blair MM, Carmichael J, Young E, Thrasher K; Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Pharmacist privileging in a health system: report of the Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(22):2373-2381.

5. Claxton KI, Wojtal P. Design and implementation of a credentialing and privileging model for ambulatory care pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(17):1627-1632.

6. Jordan TA, Hennenfent JA, Lewin JJ III, Nesbit TW, Weber R. Elevating pharmacists’ scope of practice through a health-system clinical privileging process. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1395-1405.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Collaborative practice agreements and pharmacists’ patient care services: a resource for doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and other providers. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/Translational_Tools_Providers.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, Albanese NP, Rouse MJ. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of practitioners and pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2010;50(2):e35-e69.

9. Philip B, Weber R. Enhancing pharmacy practice models through pharmacists’ privileging. Hosp Pharm. 2013; 48(2):160-165.

10. Galt KA. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(7):661-670.

11. Smith ML, Gemelas MF; US Public Health Service; Indian Health Service. Indian Health Service medical staff credentialing and privileging guide. https://www.ihs.gov/riskmanagement/includes/themes/newihstheme/display_objects/documents/IHS-Medical-Staff-Credentialing-and-Privileging-Guide.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed March 15, 2019.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Indian health manual: medical credentials and privileges review process. https://www.ihs.gov/ihm/pc/part-3/p3c1. Accessed March 15, 2019.

13. Holley SL, Ketel C. Ongoing professional practice evaluation and focused professional practice evaluation: an overview for advanced practice clinicians. J Midwifery Women Health. 2014;59(4):452-459.

1. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/Improving_Patient_and_Health_System_Outcomes.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed March 15, 2019.

2. Rouse MJ, Vlasses PH, Webb CE; Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists: a resource paper from the Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(21):e109-e118.

3. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769.

4. Blair MM, Carmichael J, Young E, Thrasher K; Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Pharmacist privileging in a health system: report of the Qualified Provider Model Ad Hoc Committee. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(22):2373-2381.

5. Claxton KI, Wojtal P. Design and implementation of a credentialing and privileging model for ambulatory care pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(17):1627-1632.

6. Jordan TA, Hennenfent JA, Lewin JJ III, Nesbit TW, Weber R. Elevating pharmacists’ scope of practice through a health-system clinical privileging process. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1395-1405.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Collaborative practice agreements and pharmacists’ patient care services: a resource for doctors, nurses, physician assistants, and other providers. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/Translational_Tools_Providers.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy, Albanese NP, Rouse MJ. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of practitioners and pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2010;50(2):e35-e69.

9. Philip B, Weber R. Enhancing pharmacy practice models through pharmacists’ privileging. Hosp Pharm. 2013; 48(2):160-165.

10. Galt KA. Credentialing and privileging of pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(7):661-670.

11. Smith ML, Gemelas MF; US Public Health Service; Indian Health Service. Indian Health Service medical staff credentialing and privileging guide. https://www.ihs.gov/riskmanagement/includes/themes/newihstheme/display_objects/documents/IHS-Medical-Staff-Credentialing-and-Privileging-Guide.pdf. Published September 2005. Accessed March 15, 2019.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. Indian health manual: medical credentials and privileges review process. https://www.ihs.gov/ihm/pc/part-3/p3c1. Accessed March 15, 2019.

13. Holley SL, Ketel C. Ongoing professional practice evaluation and focused professional practice evaluation: an overview for advanced practice clinicians. J Midwifery Women Health. 2014;59(4):452-459.

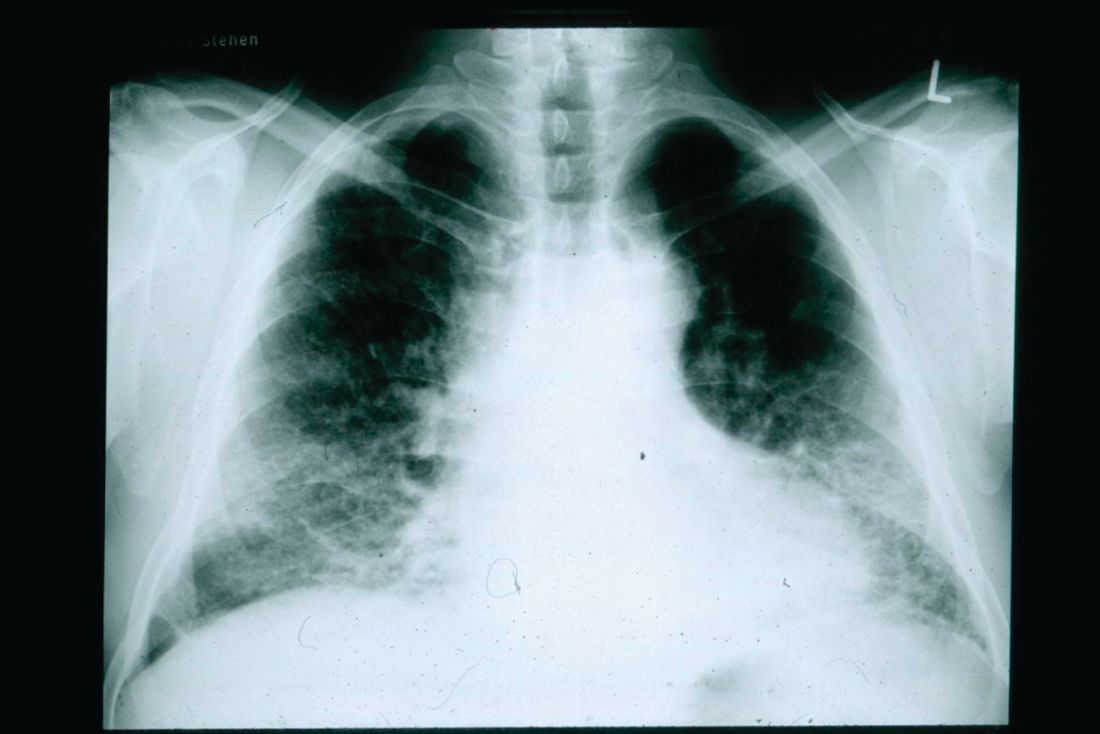

Don’t delay palliative care for IPF patients

and indicates that early, integrated palliative care should be a priority, according to the finding of a survey study.

“Patients with IPF suffer from exceptionally low [health-related quality of life] together with severe breathlessness and fatigue already two years before death. In addition, physical and emotional well-being further deteriorates near death concurrently with escalating overall symptom burden,” wrote Kaisa Rajala, MD, and her colleagues at Helsinki University Hospital.

They conducted a substudy of patients in the larger FinnishIPF study to assess health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and symptom burden in the period before death. Among 300 patients invited to participate, 247 agreed. Patient disease and sociodemographic data were collected from the FinnishIPF records and the study group completed questionnaires five times at 6 month intervals. The study began in April 2015 and continued until August 2017, by which time 92 (37%) of the patients had died (BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2018;18:172; doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x).

The investigators used self-reporting tools to look at HRQOL and symptom burden: RAND 36-item Health Survey (RAND-36), the Modified Medical Research and Council Dyspnea Scale (MMRC), the Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

About 35% of these patients were being treated with antifibrotic medication. Most of the patients had comorbidities, with cardiovascular disease being the most common.

The dimensions of HRQOL studied were physical function, general health, vitality, mental health, social function, and bodily pain. These patients experienced a gradual impairment in HRQOL similar to that of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but with a pronounced, rapid deterioration beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The symptom burden also intensified in the last 2 years of life and ramped up significantly in the last 6 months before death. NRS scores are on a scale of 0-10, from no symptoms to worst symptoms. In most clinical situations, NRS scores equal to greater than 4 trigger more comprehensive symptom assessment. The scores for symptoms for these patients during the last 6 months were dyspnea, 7.1 (standard deviation 2.8); tiredness, 6.0 (SD 2.5), cough, 5.0 (SD 3.5), pain with movement, 3.9 (SD 3.1), insomnia, 3.9 (SD 2.9), anxiety, 3.9 (SD 2.9), and depression, 3.6 (SD 3.1).

Investigators noted the steep change in the proportion of patients with MMRC scores greater than or equal to 3 (needing to stop walking after approximately 100 m or a few minutes because of breathlessness) beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The study limitations are its relatively small size, the self-reported data, and the lack of lung function measurements in most patients in the last 6 months of life.

The findings point to the urgent need for early palliative care in IPF patients, the investigators concluded. They noted that the sharp decline in HRQOL is similar to that seen in lung cancer patients, in contrast to the more gradual trend seen in COPD patients.

But there are common benefits of an early palliative program for all of these patients, they stressed. “Early integrated palliative care for patients with lung cancer has shown substantial benefits, such as lower depression scores, higher HRQOL, better communication of end-of-life care preferences, less aggressive care at the end of life, and longer overall survival. Similarly, a randomized trial demonstrated better control of dyspnea and a survival benefit with integrated palliative care in patients with COPD and interstitial lung disease. In addition to cancer patients, early integrated palliative care may reduce end-of-life acute care utilization, and allow patients with IPF to die in their preferred locations. Integrated palliative care in IPF patients seems to lower respiratory-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations and may allow more patients to die at home.”

The study was funded by The Academy of Finland and various Finnish nonprofit organizations funded the study.

SOURCE: Rajala K et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:172. doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x.

and indicates that early, integrated palliative care should be a priority, according to the finding of a survey study.

“Patients with IPF suffer from exceptionally low [health-related quality of life] together with severe breathlessness and fatigue already two years before death. In addition, physical and emotional well-being further deteriorates near death concurrently with escalating overall symptom burden,” wrote Kaisa Rajala, MD, and her colleagues at Helsinki University Hospital.

They conducted a substudy of patients in the larger FinnishIPF study to assess health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and symptom burden in the period before death. Among 300 patients invited to participate, 247 agreed. Patient disease and sociodemographic data were collected from the FinnishIPF records and the study group completed questionnaires five times at 6 month intervals. The study began in April 2015 and continued until August 2017, by which time 92 (37%) of the patients had died (BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2018;18:172; doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x).

The investigators used self-reporting tools to look at HRQOL and symptom burden: RAND 36-item Health Survey (RAND-36), the Modified Medical Research and Council Dyspnea Scale (MMRC), the Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

About 35% of these patients were being treated with antifibrotic medication. Most of the patients had comorbidities, with cardiovascular disease being the most common.

The dimensions of HRQOL studied were physical function, general health, vitality, mental health, social function, and bodily pain. These patients experienced a gradual impairment in HRQOL similar to that of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but with a pronounced, rapid deterioration beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The symptom burden also intensified in the last 2 years of life and ramped up significantly in the last 6 months before death. NRS scores are on a scale of 0-10, from no symptoms to worst symptoms. In most clinical situations, NRS scores equal to greater than 4 trigger more comprehensive symptom assessment. The scores for symptoms for these patients during the last 6 months were dyspnea, 7.1 (standard deviation 2.8); tiredness, 6.0 (SD 2.5), cough, 5.0 (SD 3.5), pain with movement, 3.9 (SD 3.1), insomnia, 3.9 (SD 2.9), anxiety, 3.9 (SD 2.9), and depression, 3.6 (SD 3.1).

Investigators noted the steep change in the proportion of patients with MMRC scores greater than or equal to 3 (needing to stop walking after approximately 100 m or a few minutes because of breathlessness) beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The study limitations are its relatively small size, the self-reported data, and the lack of lung function measurements in most patients in the last 6 months of life.

The findings point to the urgent need for early palliative care in IPF patients, the investigators concluded. They noted that the sharp decline in HRQOL is similar to that seen in lung cancer patients, in contrast to the more gradual trend seen in COPD patients.

But there are common benefits of an early palliative program for all of these patients, they stressed. “Early integrated palliative care for patients with lung cancer has shown substantial benefits, such as lower depression scores, higher HRQOL, better communication of end-of-life care preferences, less aggressive care at the end of life, and longer overall survival. Similarly, a randomized trial demonstrated better control of dyspnea and a survival benefit with integrated palliative care in patients with COPD and interstitial lung disease. In addition to cancer patients, early integrated palliative care may reduce end-of-life acute care utilization, and allow patients with IPF to die in their preferred locations. Integrated palliative care in IPF patients seems to lower respiratory-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations and may allow more patients to die at home.”

The study was funded by The Academy of Finland and various Finnish nonprofit organizations funded the study.

SOURCE: Rajala K et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:172. doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x.

and indicates that early, integrated palliative care should be a priority, according to the finding of a survey study.

“Patients with IPF suffer from exceptionally low [health-related quality of life] together with severe breathlessness and fatigue already two years before death. In addition, physical and emotional well-being further deteriorates near death concurrently with escalating overall symptom burden,” wrote Kaisa Rajala, MD, and her colleagues at Helsinki University Hospital.

They conducted a substudy of patients in the larger FinnishIPF study to assess health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and symptom burden in the period before death. Among 300 patients invited to participate, 247 agreed. Patient disease and sociodemographic data were collected from the FinnishIPF records and the study group completed questionnaires five times at 6 month intervals. The study began in April 2015 and continued until August 2017, by which time 92 (37%) of the patients had died (BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2018;18:172; doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x).

The investigators used self-reporting tools to look at HRQOL and symptom burden: RAND 36-item Health Survey (RAND-36), the Modified Medical Research and Council Dyspnea Scale (MMRC), the Modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).

About 35% of these patients were being treated with antifibrotic medication. Most of the patients had comorbidities, with cardiovascular disease being the most common.

The dimensions of HRQOL studied were physical function, general health, vitality, mental health, social function, and bodily pain. These patients experienced a gradual impairment in HRQOL similar to that of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but with a pronounced, rapid deterioration beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The symptom burden also intensified in the last 2 years of life and ramped up significantly in the last 6 months before death. NRS scores are on a scale of 0-10, from no symptoms to worst symptoms. In most clinical situations, NRS scores equal to greater than 4 trigger more comprehensive symptom assessment. The scores for symptoms for these patients during the last 6 months were dyspnea, 7.1 (standard deviation 2.8); tiredness, 6.0 (SD 2.5), cough, 5.0 (SD 3.5), pain with movement, 3.9 (SD 3.1), insomnia, 3.9 (SD 2.9), anxiety, 3.9 (SD 2.9), and depression, 3.6 (SD 3.1).

Investigators noted the steep change in the proportion of patients with MMRC scores greater than or equal to 3 (needing to stop walking after approximately 100 m or a few minutes because of breathlessness) beginning in the last 2 years of life.

The study limitations are its relatively small size, the self-reported data, and the lack of lung function measurements in most patients in the last 6 months of life.

The findings point to the urgent need for early palliative care in IPF patients, the investigators concluded. They noted that the sharp decline in HRQOL is similar to that seen in lung cancer patients, in contrast to the more gradual trend seen in COPD patients.

But there are common benefits of an early palliative program for all of these patients, they stressed. “Early integrated palliative care for patients with lung cancer has shown substantial benefits, such as lower depression scores, higher HRQOL, better communication of end-of-life care preferences, less aggressive care at the end of life, and longer overall survival. Similarly, a randomized trial demonstrated better control of dyspnea and a survival benefit with integrated palliative care in patients with COPD and interstitial lung disease. In addition to cancer patients, early integrated palliative care may reduce end-of-life acute care utilization, and allow patients with IPF to die in their preferred locations. Integrated palliative care in IPF patients seems to lower respiratory-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations and may allow more patients to die at home.”

The study was funded by The Academy of Finland and various Finnish nonprofit organizations funded the study.

SOURCE: Rajala K et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:172. doi: 0.1186/s12890-018-0738-x.

FROM BMC PULMONARY MEDICINE

New Diagnostic Procedure Codes and Reimbursement

As the US population continues to grow and patients become more aware of their health needs, payers are beginning to recognize the benefits of more efficient and cost-effective health care. With the implementation of the new Medicare Physician Fee Schedule on January 1, 2019, some old billing codes were revalued while others were replaced entirely with new codes.1 The restructuring of the standard biopsy codes now takes the complexity of different sampling techniques into consideration. Furthermore, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Category III tracking codes for some imaging devices (eg, optical coherence tomography) added in 2017 require more data before obtaining a Category I reimbursable code, while codes for other imaging devices such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) remain relatively the same.2-4 Notably, the majority of the new 2019 telemedicine codes are applicable to dermatology.2,3 In this article, we discuss the new CPT codes for reporting diagnostic procedures, including biopsy, noninvasive imaging, and telemedicine services. We also provide a summary of the national average reimbursement rates for these procedures.

Background on Reimbursement

To better understand how reimbursement works, it is important to know that all billing codes are provided a relative value unit (RVU), a number representing the value of the work involved and cost of providing a service relative to other services.5 The total RVU consists of the work RVU (wRVU), practice expense RVU (peRVU), and malpractice expense RVU (mRVU). The wRVU represents the time, effort, and complexity involved in performing the service. The peRVU reflects the direct cost of supplies, personnel, and durable equipment involved in providing the service, excluding typical office overhead costs such as rent, utilities, and administrative staff. The mRVU is to cover the cost of malpractice insurance.5 The peRVU can be further specified as facility versus nonfacility services depending on where the service is performed.6 A facility peRVU is for services completed in a facility such as a hospital, outpatient hospital setting, or nursing home. The facility provides some of the involved supplies, personnel, and equipment for which they can recapture costs by separate reporting, resulting in a lower total RVU for the provider charges compared with nonfacility locations where the physician must provide these items.6 Many physicians may not be aware of how critical their role is in determining their own reimbursement rates by understanding RVUs and properly filling out Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) surveys. If surveys sent to practitioners are accurately completed, RVUs have the potential to be fairly valued; however, if respondents are unaware of all of the components that are inherent to a procedure, they may end up minimizing the effort or time involved, which would skew the results and hurt those who perform the procedure. Rather than inputting appropriate preoperative and postoperative service times, many respondents often put 0s and 1s throughout the survey, which misrepresents the amount of time involved for a procedure. For example, inputting a preoperative time as 0 or 1 minute may severely underestimate the work involved for a procedure if the true preoperative time is 5 minutes. Such survey responses affect whether or not RVUs are valued appropriately.

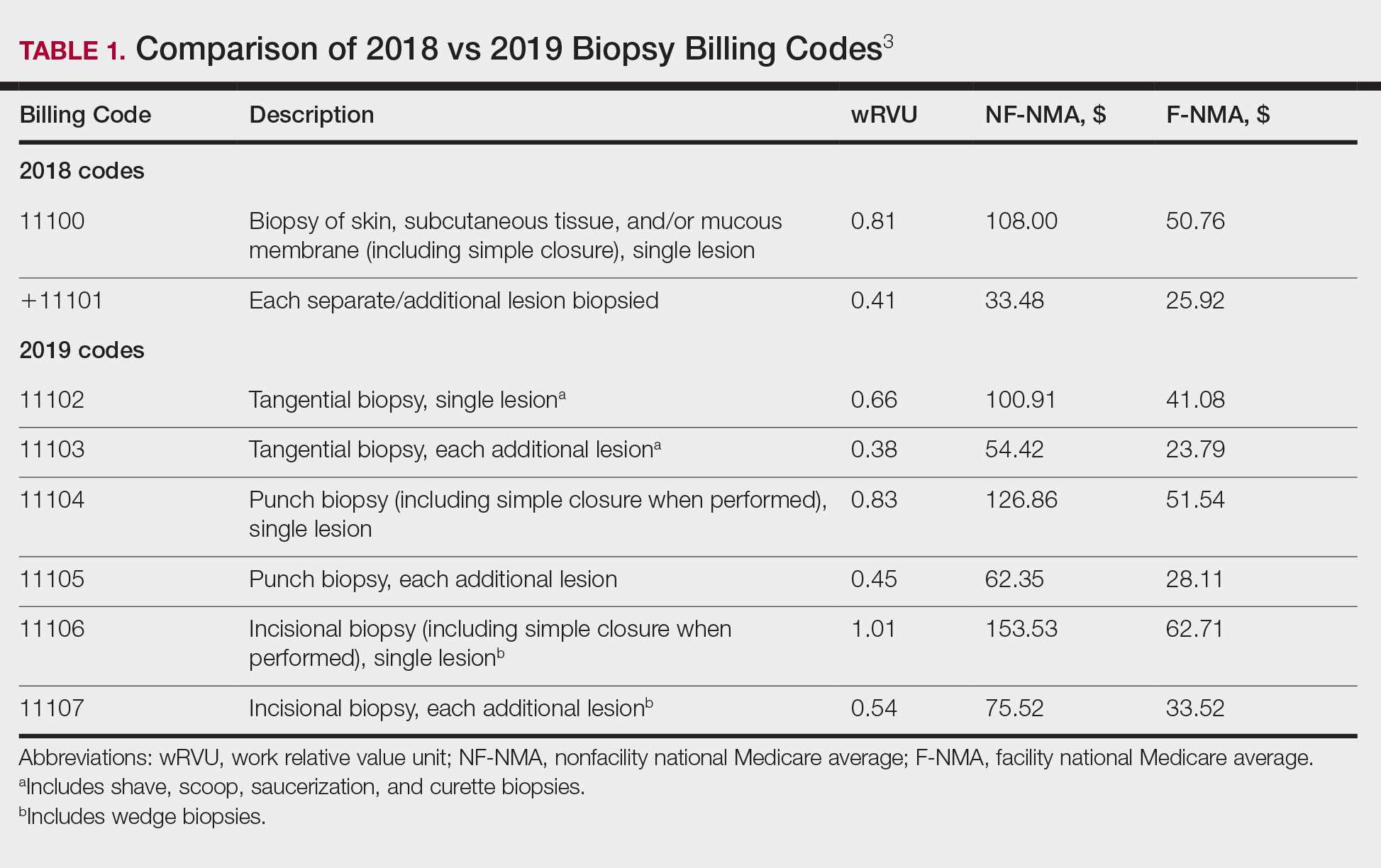

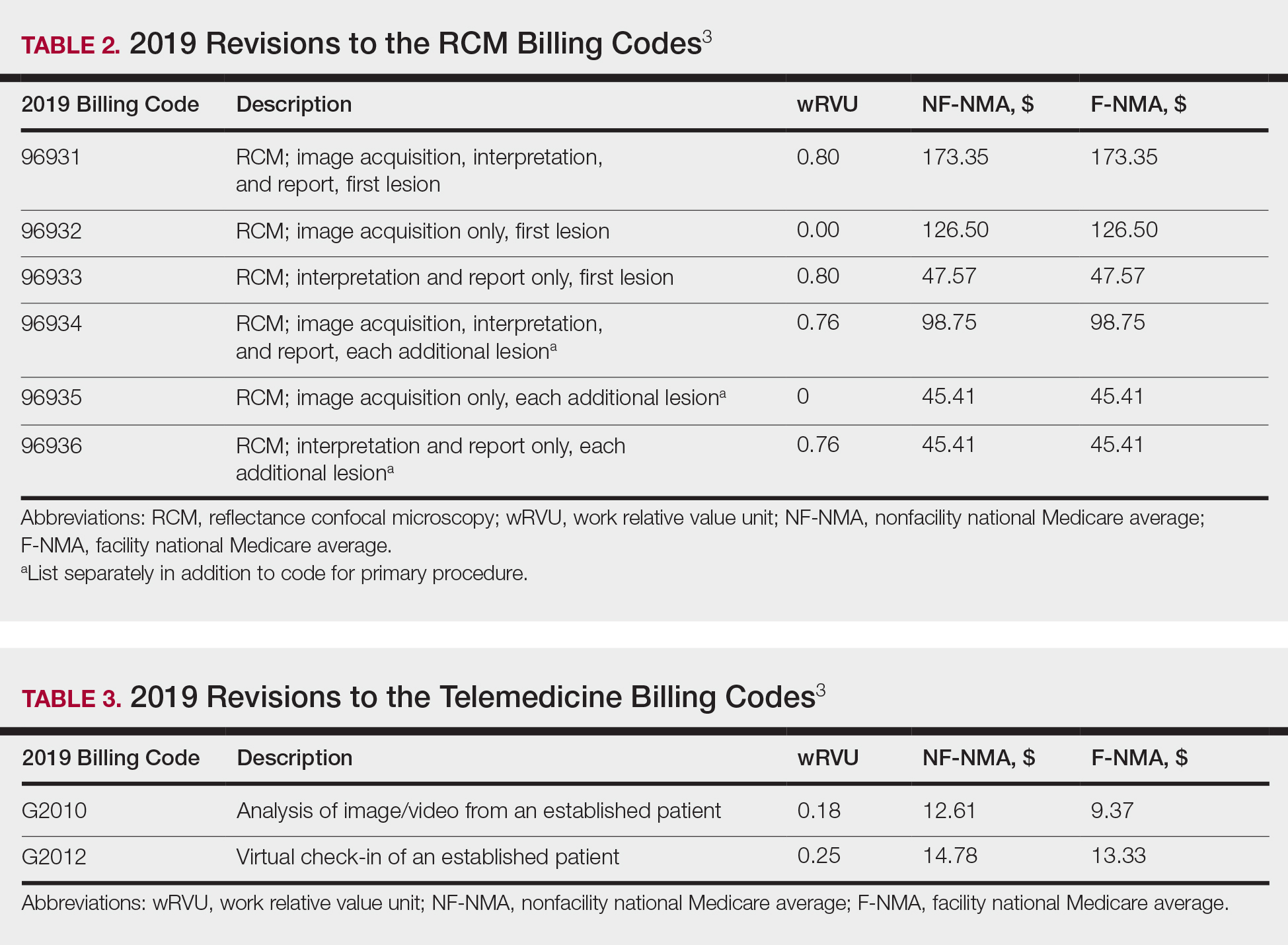

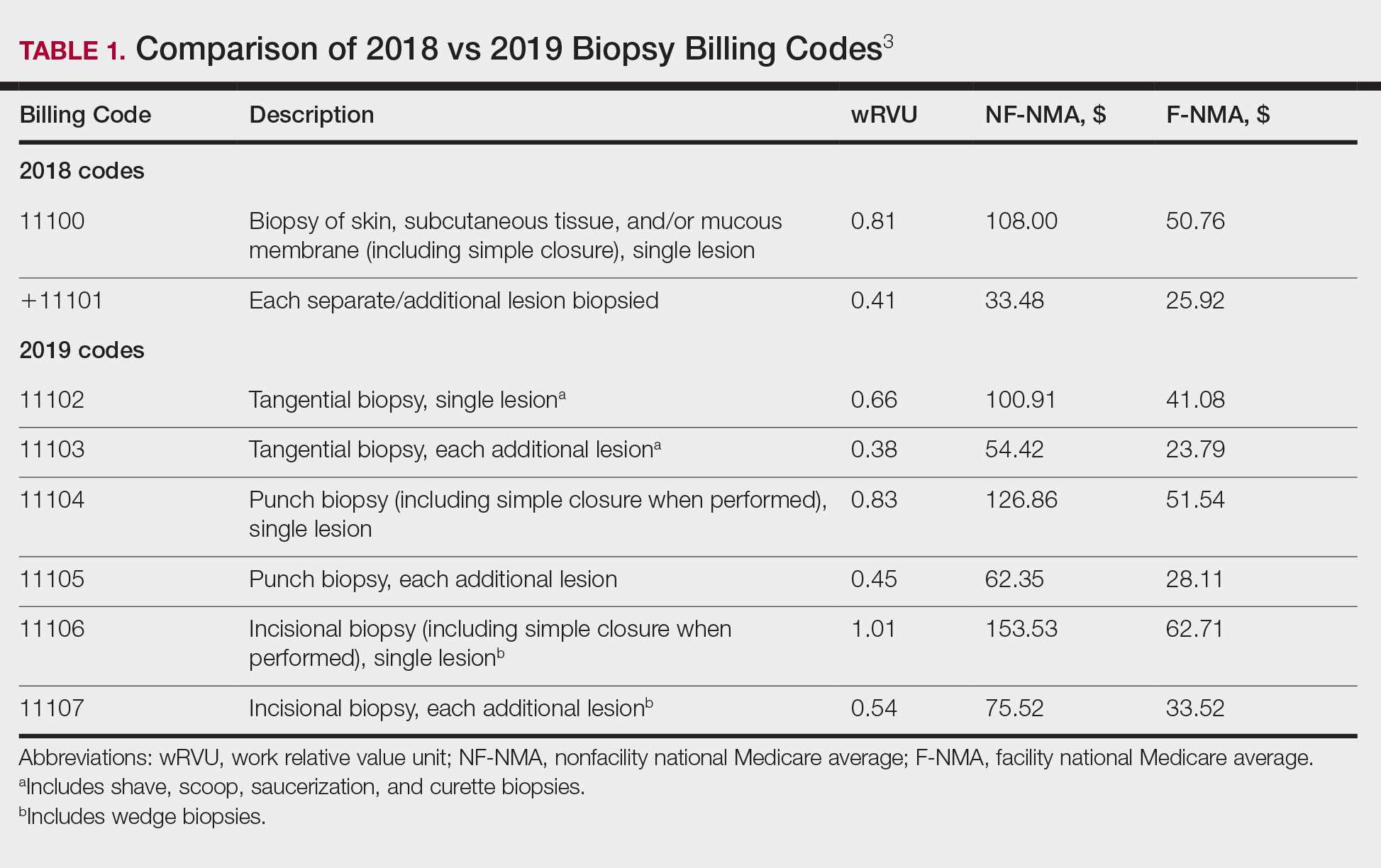

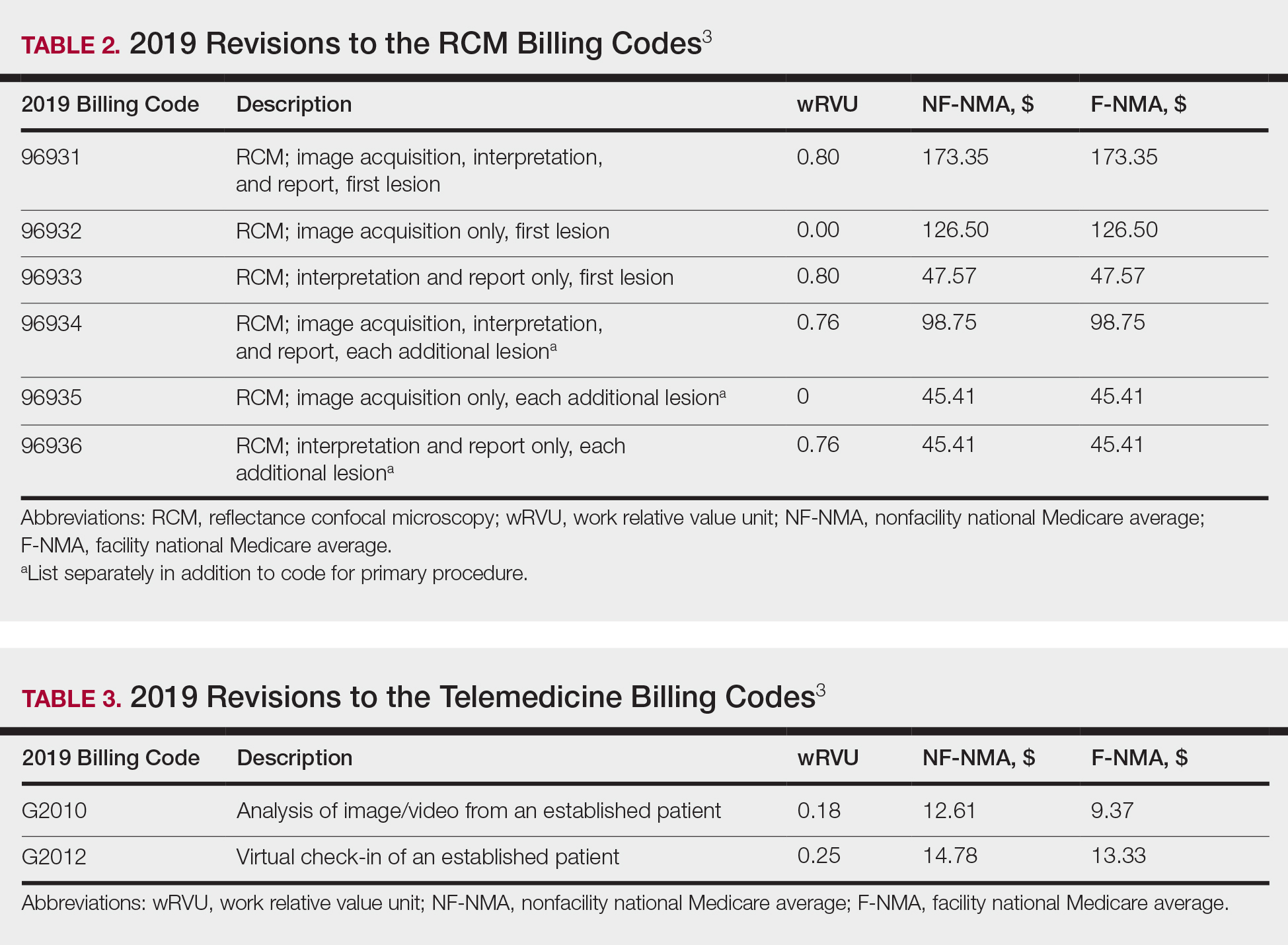

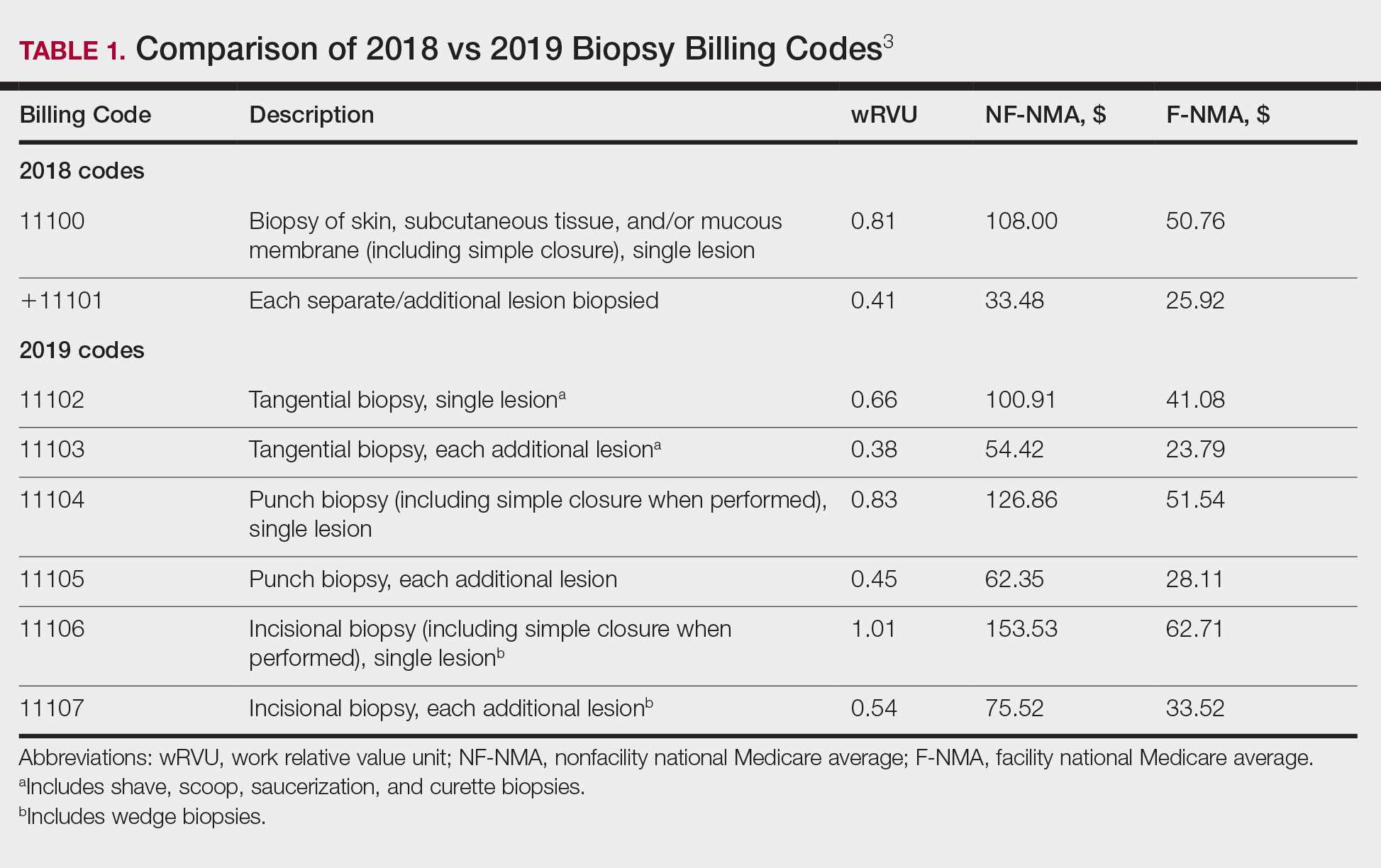

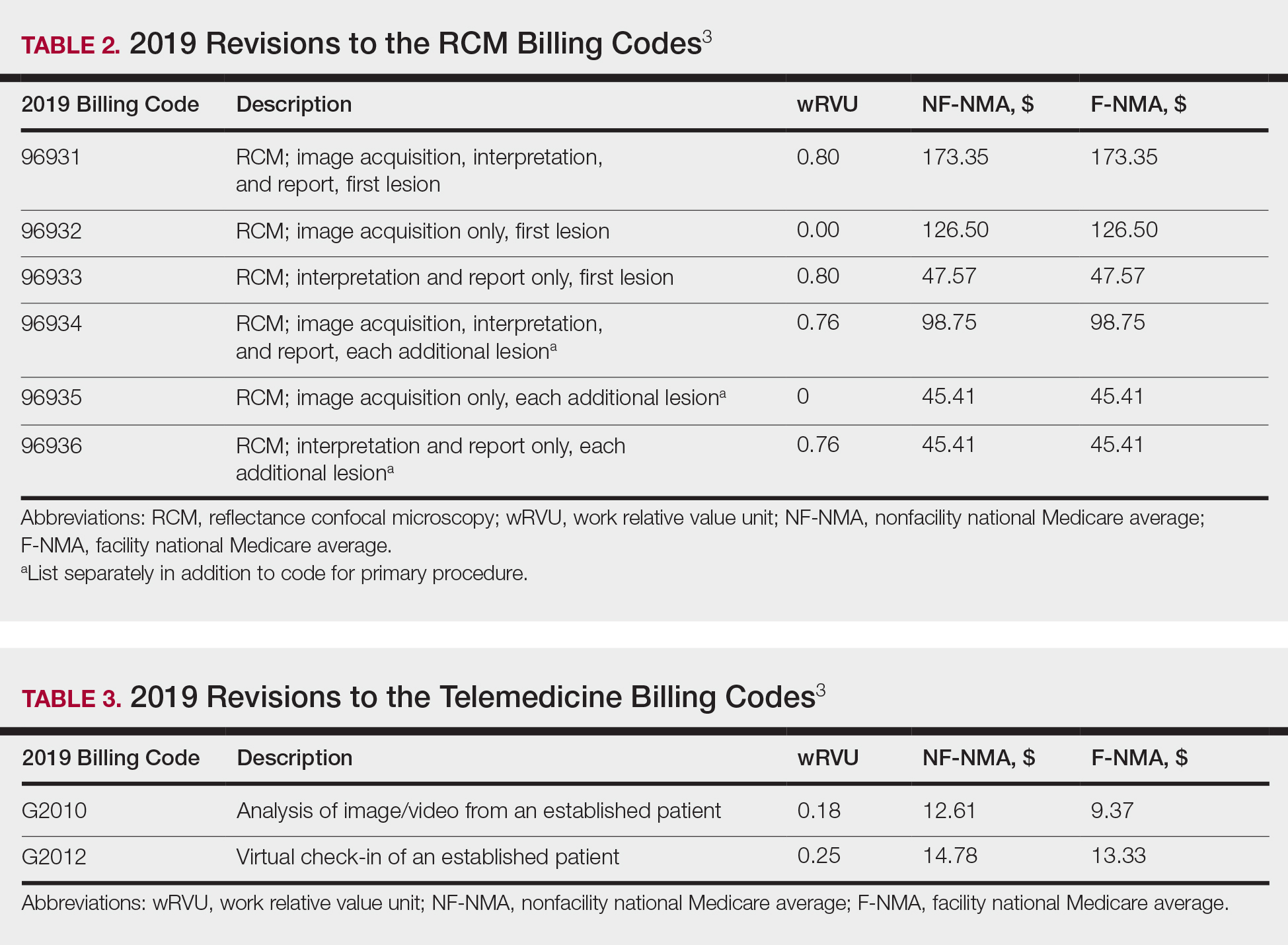

The billing codes and their RVUs as well as Medicare payment values in your area can be found on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website.2,3 Table 1 provides a comparison of the old and new biopsy codes, and Table 2 shows the new RCM codes.

Biopsy Codes