User login

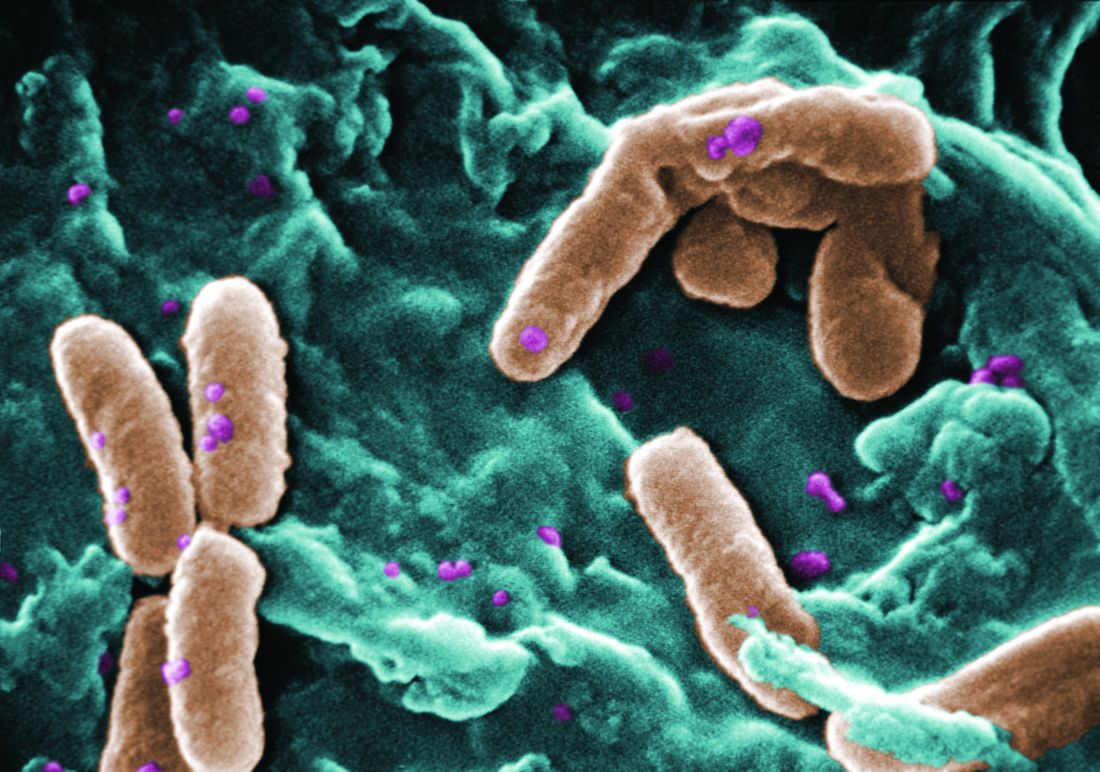

Filamentous bacteriophage linked to lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis

according to a study of the prevalence and clinical relevance of Pf phage in two patient cohorts.

“Our data from both the Stanford and Danish CF cohorts together suggest that either patients with CF acquire Pf phage–producing strains of P. aeruginosa or the Pf phage–negative P. aeruginosa become infected with Pf phage as patients age and their disease progresses,” wrote Elizabeth B. Burgener, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.The study analyzed a previous Danish longitudinal cohort of 34 patients and a prospective cross-sectional cohort of 76 patients at Stanford, 58 of which had P. aeruginosa. The researchers also reviewed a collection of genetic sequences called the Pseudomonas Genome Database to determine the prevalence of Pf phage, finding evidence in 1,159 of 2,226 P. aeruginosa sequences (52.1%).

In the Danish cohort, 21 of the 34 CF patients (61.8%; 95% confidence interval, 43.6%-77.8%) had at least one P. aeruginosa isolate containing Pf phage; 9 (26.5%) of the patients were found to be consistently positive for Pf phage. Those who were consistently positive were also older than those who never had Pf phage detected (19.1 years vs. 13.9 years; P = .046), suggesting that “there may be a tendency for P. aeruginosa strains that produce Pf phage to dominate in the sputum of individual patients with CF over time.”

In the Stanford cohort, the prevalence of Pf phage was 36.2% (21 of 58; 95% CI, 24.0%-49.9%) in patients with P. aeruginosa infection and 27.6% (21 of 76; 95% CI, 18.0%-39.1%) in all patients. No Pf phage was detected in any P. aeruginosa–negative samples. Patients positive for Pf phage in this cohort were also older than patients who were negative.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, describing the methods used to collect and sequence the analyzed samples as “highly heterogeneous.” In addition, the two cohorts were CF specific while the Genome Database is not. Finally, the CF cohorts only had a single dominant strain sampled, though multiple P. aeruginosa lineages are often present in CF patients.

One author reported receiving grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, clinical trial support, and consulting fees from industry. Two other authors are inventors on a patent application that covers the development of a vaccine that targets Pf phage. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burgener EB et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9748.

according to a study of the prevalence and clinical relevance of Pf phage in two patient cohorts.

“Our data from both the Stanford and Danish CF cohorts together suggest that either patients with CF acquire Pf phage–producing strains of P. aeruginosa or the Pf phage–negative P. aeruginosa become infected with Pf phage as patients age and their disease progresses,” wrote Elizabeth B. Burgener, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.The study analyzed a previous Danish longitudinal cohort of 34 patients and a prospective cross-sectional cohort of 76 patients at Stanford, 58 of which had P. aeruginosa. The researchers also reviewed a collection of genetic sequences called the Pseudomonas Genome Database to determine the prevalence of Pf phage, finding evidence in 1,159 of 2,226 P. aeruginosa sequences (52.1%).

In the Danish cohort, 21 of the 34 CF patients (61.8%; 95% confidence interval, 43.6%-77.8%) had at least one P. aeruginosa isolate containing Pf phage; 9 (26.5%) of the patients were found to be consistently positive for Pf phage. Those who were consistently positive were also older than those who never had Pf phage detected (19.1 years vs. 13.9 years; P = .046), suggesting that “there may be a tendency for P. aeruginosa strains that produce Pf phage to dominate in the sputum of individual patients with CF over time.”

In the Stanford cohort, the prevalence of Pf phage was 36.2% (21 of 58; 95% CI, 24.0%-49.9%) in patients with P. aeruginosa infection and 27.6% (21 of 76; 95% CI, 18.0%-39.1%) in all patients. No Pf phage was detected in any P. aeruginosa–negative samples. Patients positive for Pf phage in this cohort were also older than patients who were negative.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, describing the methods used to collect and sequence the analyzed samples as “highly heterogeneous.” In addition, the two cohorts were CF specific while the Genome Database is not. Finally, the CF cohorts only had a single dominant strain sampled, though multiple P. aeruginosa lineages are often present in CF patients.

One author reported receiving grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, clinical trial support, and consulting fees from industry. Two other authors are inventors on a patent application that covers the development of a vaccine that targets Pf phage. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burgener EB et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9748.

according to a study of the prevalence and clinical relevance of Pf phage in two patient cohorts.

“Our data from both the Stanford and Danish CF cohorts together suggest that either patients with CF acquire Pf phage–producing strains of P. aeruginosa or the Pf phage–negative P. aeruginosa become infected with Pf phage as patients age and their disease progresses,” wrote Elizabeth B. Burgener, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors. The study was published in Science Translational Medicine.The study analyzed a previous Danish longitudinal cohort of 34 patients and a prospective cross-sectional cohort of 76 patients at Stanford, 58 of which had P. aeruginosa. The researchers also reviewed a collection of genetic sequences called the Pseudomonas Genome Database to determine the prevalence of Pf phage, finding evidence in 1,159 of 2,226 P. aeruginosa sequences (52.1%).

In the Danish cohort, 21 of the 34 CF patients (61.8%; 95% confidence interval, 43.6%-77.8%) had at least one P. aeruginosa isolate containing Pf phage; 9 (26.5%) of the patients were found to be consistently positive for Pf phage. Those who were consistently positive were also older than those who never had Pf phage detected (19.1 years vs. 13.9 years; P = .046), suggesting that “there may be a tendency for P. aeruginosa strains that produce Pf phage to dominate in the sputum of individual patients with CF over time.”

In the Stanford cohort, the prevalence of Pf phage was 36.2% (21 of 58; 95% CI, 24.0%-49.9%) in patients with P. aeruginosa infection and 27.6% (21 of 76; 95% CI, 18.0%-39.1%) in all patients. No Pf phage was detected in any P. aeruginosa–negative samples. Patients positive for Pf phage in this cohort were also older than patients who were negative.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, describing the methods used to collect and sequence the analyzed samples as “highly heterogeneous.” In addition, the two cohorts were CF specific while the Genome Database is not. Finally, the CF cohorts only had a single dominant strain sampled, though multiple P. aeruginosa lineages are often present in CF patients.

One author reported receiving grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, clinical trial support, and consulting fees from industry. Two other authors are inventors on a patent application that covers the development of a vaccine that targets Pf phage. The others reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burgener EB et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9748.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Ibrexafungerp effective against C. auris in two early case reports

A novel antifungal successfully eradicated Candida auris in two critically ill patients with fungemia, according to data presented in a poster session at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

The case reports, drawn from the phase 3 CARES study of the oral formulation of ibrexafungerp, demonstrated complete response to the glucan synthase inhibitor, according to Deven Juneja, MD, and his coauthors of the Max Super Specialty Hospital, New Delhi.

The first patient was an Asian male, aged 58 years, who had a previous history of diabetes and experienced a protracted ICU stay after acute ischemic stroke. He developed septic shock after aspiration pneumonia, and also experienced a popliteal thrombosis and liver, spleen, and kidney infarcts.

The patient had received empiric antibiotics with the addition of fluconazole; the antifungal was later switched to micafungin after C. auris was identified from blood cultures. Despite clinical improvement on micafungin, blood cultures remained positive for C. auris, so ibrexafungerp was started and continued for 17 days. Blood cultures became negative by day 3 of ibrexafungerp and remained negative for the follow-up period. The patient later developed Klebsiella pneumonia and died.

The second patient, an Asian female, aged 64 years, presented with a lower respiratory tract infection accompanied by fever and hypotension. She had a previous history of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with maintenance hemodialysis. Her fever also persisted despite antibiotics, and C. auris was isolated from her blood cultures with the subsequent initiation of ibrexafungerp. Her blood cultures were still positive at day 3 of ibrexafungerp, but negative at day 9 and 21. She completed 22 days of ibrexafungerp therapy and was asymptomatic with no evidence of C. auris recurrence at a 6-week follow-up visit.

The male patient experienced 2 days of loose stools soon after initiating ibrexafungerp; the female patient had no adverse events.

“These cases provide initial evidence of efficacy and safety of ibrexafungerp in the treatment of candidemia caused by C. auris, including in patients who failed previous therapies,” wrote Dr. Juneja and his coauthors in the late-breaking poster.

Ibrexafungerp belongs to a novel class of glucan synthase inhibitors called triterpenoids. Scynexis funded the CARES study and also is evaluating it alone or in combination with other antifungals for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and refractory invasive and/or severe fungal disease.

SOURCE: Juneja D et al. ECCMID 2019, Poster L0028.

A novel antifungal successfully eradicated Candida auris in two critically ill patients with fungemia, according to data presented in a poster session at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

The case reports, drawn from the phase 3 CARES study of the oral formulation of ibrexafungerp, demonstrated complete response to the glucan synthase inhibitor, according to Deven Juneja, MD, and his coauthors of the Max Super Specialty Hospital, New Delhi.

The first patient was an Asian male, aged 58 years, who had a previous history of diabetes and experienced a protracted ICU stay after acute ischemic stroke. He developed septic shock after aspiration pneumonia, and also experienced a popliteal thrombosis and liver, spleen, and kidney infarcts.

The patient had received empiric antibiotics with the addition of fluconazole; the antifungal was later switched to micafungin after C. auris was identified from blood cultures. Despite clinical improvement on micafungin, blood cultures remained positive for C. auris, so ibrexafungerp was started and continued for 17 days. Blood cultures became negative by day 3 of ibrexafungerp and remained negative for the follow-up period. The patient later developed Klebsiella pneumonia and died.

The second patient, an Asian female, aged 64 years, presented with a lower respiratory tract infection accompanied by fever and hypotension. She had a previous history of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with maintenance hemodialysis. Her fever also persisted despite antibiotics, and C. auris was isolated from her blood cultures with the subsequent initiation of ibrexafungerp. Her blood cultures were still positive at day 3 of ibrexafungerp, but negative at day 9 and 21. She completed 22 days of ibrexafungerp therapy and was asymptomatic with no evidence of C. auris recurrence at a 6-week follow-up visit.

The male patient experienced 2 days of loose stools soon after initiating ibrexafungerp; the female patient had no adverse events.

“These cases provide initial evidence of efficacy and safety of ibrexafungerp in the treatment of candidemia caused by C. auris, including in patients who failed previous therapies,” wrote Dr. Juneja and his coauthors in the late-breaking poster.

Ibrexafungerp belongs to a novel class of glucan synthase inhibitors called triterpenoids. Scynexis funded the CARES study and also is evaluating it alone or in combination with other antifungals for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and refractory invasive and/or severe fungal disease.

SOURCE: Juneja D et al. ECCMID 2019, Poster L0028.

A novel antifungal successfully eradicated Candida auris in two critically ill patients with fungemia, according to data presented in a poster session at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

The case reports, drawn from the phase 3 CARES study of the oral formulation of ibrexafungerp, demonstrated complete response to the glucan synthase inhibitor, according to Deven Juneja, MD, and his coauthors of the Max Super Specialty Hospital, New Delhi.

The first patient was an Asian male, aged 58 years, who had a previous history of diabetes and experienced a protracted ICU stay after acute ischemic stroke. He developed septic shock after aspiration pneumonia, and also experienced a popliteal thrombosis and liver, spleen, and kidney infarcts.

The patient had received empiric antibiotics with the addition of fluconazole; the antifungal was later switched to micafungin after C. auris was identified from blood cultures. Despite clinical improvement on micafungin, blood cultures remained positive for C. auris, so ibrexafungerp was started and continued for 17 days. Blood cultures became negative by day 3 of ibrexafungerp and remained negative for the follow-up period. The patient later developed Klebsiella pneumonia and died.

The second patient, an Asian female, aged 64 years, presented with a lower respiratory tract infection accompanied by fever and hypotension. She had a previous history of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease with maintenance hemodialysis. Her fever also persisted despite antibiotics, and C. auris was isolated from her blood cultures with the subsequent initiation of ibrexafungerp. Her blood cultures were still positive at day 3 of ibrexafungerp, but negative at day 9 and 21. She completed 22 days of ibrexafungerp therapy and was asymptomatic with no evidence of C. auris recurrence at a 6-week follow-up visit.

The male patient experienced 2 days of loose stools soon after initiating ibrexafungerp; the female patient had no adverse events.

“These cases provide initial evidence of efficacy and safety of ibrexafungerp in the treatment of candidemia caused by C. auris, including in patients who failed previous therapies,” wrote Dr. Juneja and his coauthors in the late-breaking poster.

Ibrexafungerp belongs to a novel class of glucan synthase inhibitors called triterpenoids. Scynexis funded the CARES study and also is evaluating it alone or in combination with other antifungals for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, and refractory invasive and/or severe fungal disease.

SOURCE: Juneja D et al. ECCMID 2019, Poster L0028.

FROM ECCMID 2019

Teen junk-food rebels, 3-D printed hearts, and strategic java stockpiles

Sticking it to the (junk-food) man

Fight the power – the power, in this case, being Ronald McDonald and his brethren.

In a new effort to convince teens to reject junk food and make healthier choices, researchers found that one surefire way to achieve this was to play on the natural teen desire to reject authority and rebel. Parents of teens across the country don’t know whether to rejoice or groan.

The study, published this week, found that an effective way to combat junk food marketing was to frame companies as corporate overlords and figures of authority who take advantage of vulnerable populations (so, the truth). The teens, who value social justice and autonomy from adults, responded well to this reframing. Instead of snacking on Doritos at lunch, the study subjects chose to really stick it to the man and make healthy food choices instead.

Researchers reported that boys in particular responded positively to the idea of rejecting authority. Which will surprise no one who has ever known a teenage boy.

I heart 3-D printing

Fifty-two years ago, a South African surgeon named Dr. Christiaan Barnard took a heart from one (deceased) human and successfully transplanted it into another (live) human. Now, Israeli researchers could relegate Dr. Barnard’s recycled-cardiac-parts approach to the medical history museum’s hall of obsolete approaches, next to the leeches and the wax barber-surgeon.

In a claimed first, Tel Aviv University scientists have “printed” a fully vascularized, engineered human heart. The organ is crafted from a cellular slurry of a patient’s own fat cells turned into pluripotent stem cells. With collagen and glycoproteins as structural printing “ink,” the researchers mixed in the stem cells and printed their 3-D heart. The cells differentiated into cardiac and endothelial cells, complete with a medical first: vascularized and perfusable heart tissue.

Unlike Barnard’s allogeneic approach, building from a patient’s own cellular material can eliminate the risk of organ rejection, the heart’s creators say.

Next on the heart-printers’ punch list: getting the cells to contract in unison to form a pumping unit. Then testing it in animals. Oh, and creating something a bit larger than their initial rabbit-sized heart.

And then? Who knows? Perhaps even Dorothy’s friend the Tin Man can finally get an autologous, printed replacement for that allogeneic, heart-shaped clock.

Larger portions of food for thought

In the world of nutrition science, there’s a concept known as self-regulation, which suggests that people have an innate ability to consume only as many calories as they need. Studies have shown that, in adults anyway, self-regulation can be circumvented by something known as the portion-size effect, which is the tendency to eat more when larger portions are served.

But is the same thing true for small children? Let’s find out.

Researchers provided a group of 3- to 5-year-old children with all their meals and snacks for two 5-day periods. During one of the periods, the portions were 50% larger than the other period. The children were allowed to eat as much of each meal/snack as they wanted, and any leftovers were weighed to determine actual calorie intake.

The data showed that the children ate 16% more food and consumed 18% more calories when they were given the larger portions.

So, we already knew that if you give adults more food, they’ll eat more. And now we know that if you give children more food, they’ll eat more. Could this be the end of self-regulation?

Maybe it would work if you gave the little tykes something besides food. Maybe you could give them … money. Round up a few hundred children, put them together in a big room, and throw money at them.

Oh, right, that experiment is already underway. It’s called Congress.

It’s the end of the world as we ... zzzzz

Of all the countries to take refuge in during an apocalypse, Switzerland has to be at the top of the list. Its mountainous terrain is a natural barrier to any zombie horde that’s heard that Swiss brains are as delicious as their chocolate. Not only that, the Swiss government stockpiles essential resources to sustain its people during times of war or emergency.

All in all, it’s a pretty good deal.

Well, it’s a good deal so long as you don’t require a morning cup of coffee to stay fresh as you fight off armies of the undead, as the Swiss government has decreed that coffee is nonessential for life and will stop stockpiling it.

According to the Federal Office for National Economic Supply, “Coffee is not vital. ... that is, coffee contains almost no calories and therefore does not make any contribution to food security from a nutritional point of view.” Harsh words for a beverage that the Swiss consume at a rate of 9 kg per year, three times more than the British and twice that of Americans.

If the recommendation passes, the 3-month emergency supply, an amount topping 15,000 tons, would be returned to the corresponding manufacturers, who would pass the corresponding savings back to the consumer.

So, there’s some good news as the zombies breach your defenses because your guards fell asleep: At least the coffee was cheaper before the world ended.

Sticking it to the (junk-food) man

Fight the power – the power, in this case, being Ronald McDonald and his brethren.

In a new effort to convince teens to reject junk food and make healthier choices, researchers found that one surefire way to achieve this was to play on the natural teen desire to reject authority and rebel. Parents of teens across the country don’t know whether to rejoice or groan.

The study, published this week, found that an effective way to combat junk food marketing was to frame companies as corporate overlords and figures of authority who take advantage of vulnerable populations (so, the truth). The teens, who value social justice and autonomy from adults, responded well to this reframing. Instead of snacking on Doritos at lunch, the study subjects chose to really stick it to the man and make healthy food choices instead.

Researchers reported that boys in particular responded positively to the idea of rejecting authority. Which will surprise no one who has ever known a teenage boy.

I heart 3-D printing

Fifty-two years ago, a South African surgeon named Dr. Christiaan Barnard took a heart from one (deceased) human and successfully transplanted it into another (live) human. Now, Israeli researchers could relegate Dr. Barnard’s recycled-cardiac-parts approach to the medical history museum’s hall of obsolete approaches, next to the leeches and the wax barber-surgeon.

In a claimed first, Tel Aviv University scientists have “printed” a fully vascularized, engineered human heart. The organ is crafted from a cellular slurry of a patient’s own fat cells turned into pluripotent stem cells. With collagen and glycoproteins as structural printing “ink,” the researchers mixed in the stem cells and printed their 3-D heart. The cells differentiated into cardiac and endothelial cells, complete with a medical first: vascularized and perfusable heart tissue.

Unlike Barnard’s allogeneic approach, building from a patient’s own cellular material can eliminate the risk of organ rejection, the heart’s creators say.

Next on the heart-printers’ punch list: getting the cells to contract in unison to form a pumping unit. Then testing it in animals. Oh, and creating something a bit larger than their initial rabbit-sized heart.

And then? Who knows? Perhaps even Dorothy’s friend the Tin Man can finally get an autologous, printed replacement for that allogeneic, heart-shaped clock.

Larger portions of food for thought

In the world of nutrition science, there’s a concept known as self-regulation, which suggests that people have an innate ability to consume only as many calories as they need. Studies have shown that, in adults anyway, self-regulation can be circumvented by something known as the portion-size effect, which is the tendency to eat more when larger portions are served.

But is the same thing true for small children? Let’s find out.

Researchers provided a group of 3- to 5-year-old children with all their meals and snacks for two 5-day periods. During one of the periods, the portions were 50% larger than the other period. The children were allowed to eat as much of each meal/snack as they wanted, and any leftovers were weighed to determine actual calorie intake.

The data showed that the children ate 16% more food and consumed 18% more calories when they were given the larger portions.

So, we already knew that if you give adults more food, they’ll eat more. And now we know that if you give children more food, they’ll eat more. Could this be the end of self-regulation?

Maybe it would work if you gave the little tykes something besides food. Maybe you could give them … money. Round up a few hundred children, put them together in a big room, and throw money at them.

Oh, right, that experiment is already underway. It’s called Congress.

It’s the end of the world as we ... zzzzz

Of all the countries to take refuge in during an apocalypse, Switzerland has to be at the top of the list. Its mountainous terrain is a natural barrier to any zombie horde that’s heard that Swiss brains are as delicious as their chocolate. Not only that, the Swiss government stockpiles essential resources to sustain its people during times of war or emergency.

All in all, it’s a pretty good deal.

Well, it’s a good deal so long as you don’t require a morning cup of coffee to stay fresh as you fight off armies of the undead, as the Swiss government has decreed that coffee is nonessential for life and will stop stockpiling it.

According to the Federal Office for National Economic Supply, “Coffee is not vital. ... that is, coffee contains almost no calories and therefore does not make any contribution to food security from a nutritional point of view.” Harsh words for a beverage that the Swiss consume at a rate of 9 kg per year, three times more than the British and twice that of Americans.

If the recommendation passes, the 3-month emergency supply, an amount topping 15,000 tons, would be returned to the corresponding manufacturers, who would pass the corresponding savings back to the consumer.

So, there’s some good news as the zombies breach your defenses because your guards fell asleep: At least the coffee was cheaper before the world ended.

Sticking it to the (junk-food) man

Fight the power – the power, in this case, being Ronald McDonald and his brethren.

In a new effort to convince teens to reject junk food and make healthier choices, researchers found that one surefire way to achieve this was to play on the natural teen desire to reject authority and rebel. Parents of teens across the country don’t know whether to rejoice or groan.

The study, published this week, found that an effective way to combat junk food marketing was to frame companies as corporate overlords and figures of authority who take advantage of vulnerable populations (so, the truth). The teens, who value social justice and autonomy from adults, responded well to this reframing. Instead of snacking on Doritos at lunch, the study subjects chose to really stick it to the man and make healthy food choices instead.

Researchers reported that boys in particular responded positively to the idea of rejecting authority. Which will surprise no one who has ever known a teenage boy.

I heart 3-D printing

Fifty-two years ago, a South African surgeon named Dr. Christiaan Barnard took a heart from one (deceased) human and successfully transplanted it into another (live) human. Now, Israeli researchers could relegate Dr. Barnard’s recycled-cardiac-parts approach to the medical history museum’s hall of obsolete approaches, next to the leeches and the wax barber-surgeon.

In a claimed first, Tel Aviv University scientists have “printed” a fully vascularized, engineered human heart. The organ is crafted from a cellular slurry of a patient’s own fat cells turned into pluripotent stem cells. With collagen and glycoproteins as structural printing “ink,” the researchers mixed in the stem cells and printed their 3-D heart. The cells differentiated into cardiac and endothelial cells, complete with a medical first: vascularized and perfusable heart tissue.

Unlike Barnard’s allogeneic approach, building from a patient’s own cellular material can eliminate the risk of organ rejection, the heart’s creators say.

Next on the heart-printers’ punch list: getting the cells to contract in unison to form a pumping unit. Then testing it in animals. Oh, and creating something a bit larger than their initial rabbit-sized heart.

And then? Who knows? Perhaps even Dorothy’s friend the Tin Man can finally get an autologous, printed replacement for that allogeneic, heart-shaped clock.

Larger portions of food for thought

In the world of nutrition science, there’s a concept known as self-regulation, which suggests that people have an innate ability to consume only as many calories as they need. Studies have shown that, in adults anyway, self-regulation can be circumvented by something known as the portion-size effect, which is the tendency to eat more when larger portions are served.

But is the same thing true for small children? Let’s find out.

Researchers provided a group of 3- to 5-year-old children with all their meals and snacks for two 5-day periods. During one of the periods, the portions were 50% larger than the other period. The children were allowed to eat as much of each meal/snack as they wanted, and any leftovers were weighed to determine actual calorie intake.

The data showed that the children ate 16% more food and consumed 18% more calories when they were given the larger portions.

So, we already knew that if you give adults more food, they’ll eat more. And now we know that if you give children more food, they’ll eat more. Could this be the end of self-regulation?

Maybe it would work if you gave the little tykes something besides food. Maybe you could give them … money. Round up a few hundred children, put them together in a big room, and throw money at them.

Oh, right, that experiment is already underway. It’s called Congress.

It’s the end of the world as we ... zzzzz

Of all the countries to take refuge in during an apocalypse, Switzerland has to be at the top of the list. Its mountainous terrain is a natural barrier to any zombie horde that’s heard that Swiss brains are as delicious as their chocolate. Not only that, the Swiss government stockpiles essential resources to sustain its people during times of war or emergency.

All in all, it’s a pretty good deal.

Well, it’s a good deal so long as you don’t require a morning cup of coffee to stay fresh as you fight off armies of the undead, as the Swiss government has decreed that coffee is nonessential for life and will stop stockpiling it.

According to the Federal Office for National Economic Supply, “Coffee is not vital. ... that is, coffee contains almost no calories and therefore does not make any contribution to food security from a nutritional point of view.” Harsh words for a beverage that the Swiss consume at a rate of 9 kg per year, three times more than the British and twice that of Americans.

If the recommendation passes, the 3-month emergency supply, an amount topping 15,000 tons, would be returned to the corresponding manufacturers, who would pass the corresponding savings back to the consumer.

So, there’s some good news as the zombies breach your defenses because your guards fell asleep: At least the coffee was cheaper before the world ended.

Candida auris: Dangerous and here to stay

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

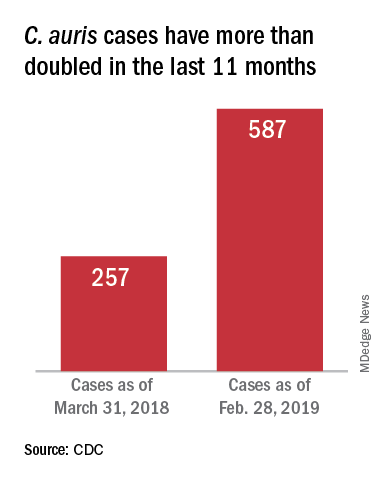

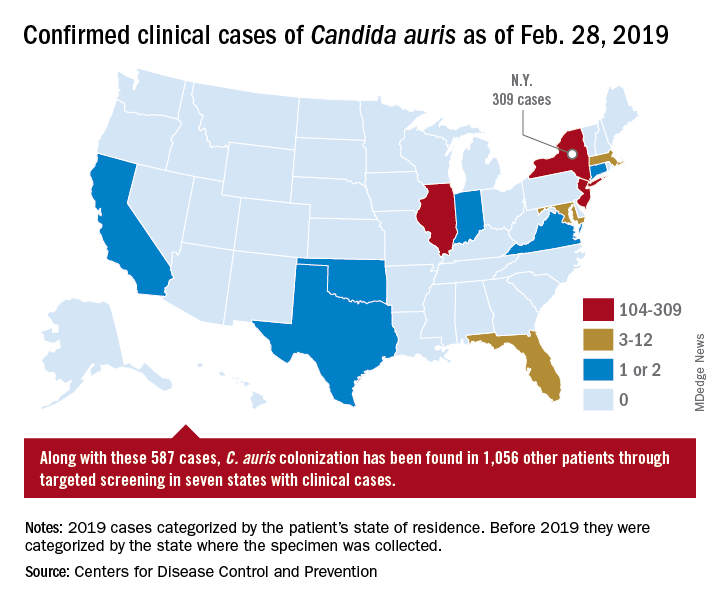

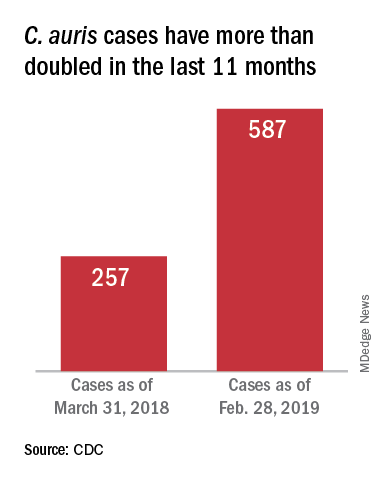

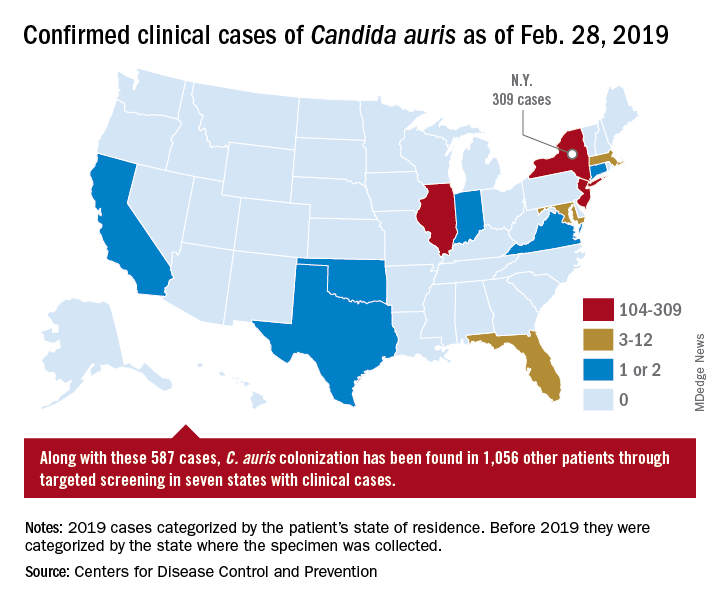

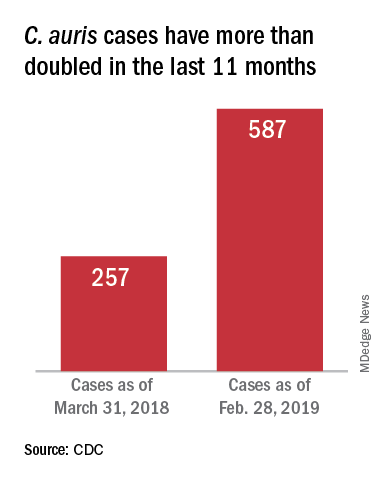

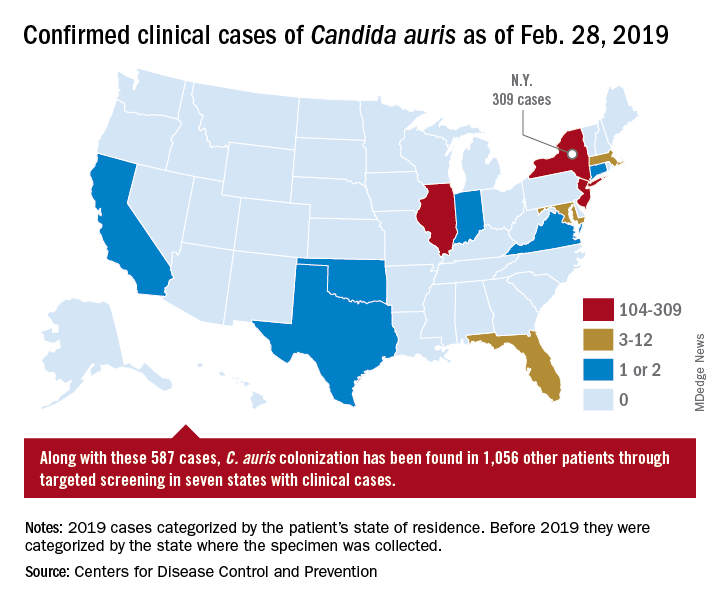

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

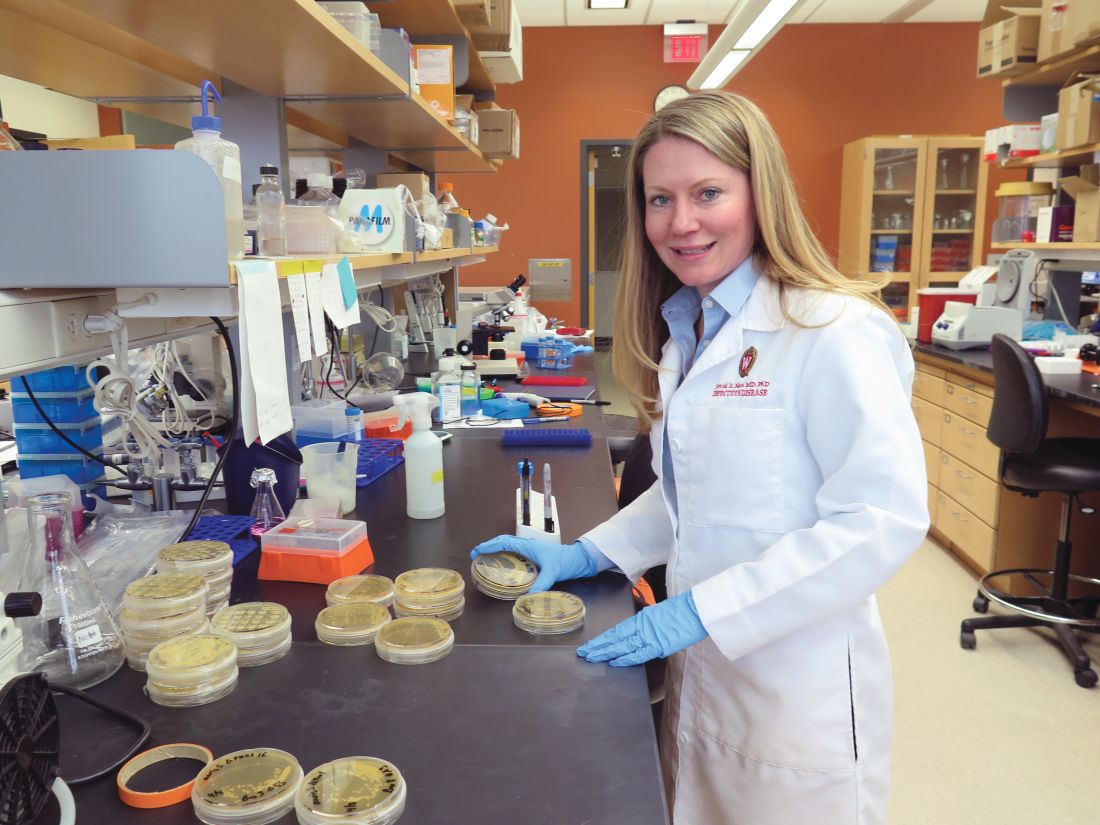

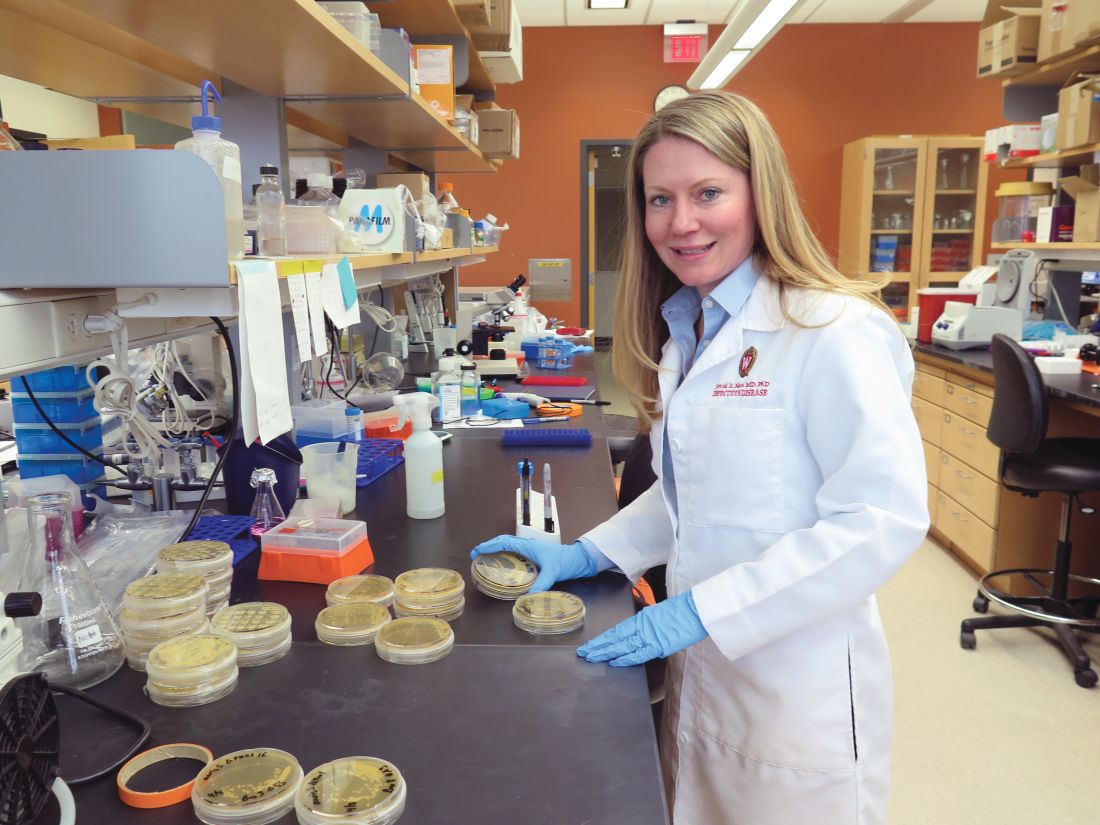

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at [email protected], and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at [email protected], and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.

Critical care units and long-term care facilities are on alert for cases of Candida auris, a novel fungal infection that is both dangerous to vulnerable patients and difficult to eradicate. The increased profile of C. auris is not a welcome development but is no surprise to critical care physicians.

This pathogen was first identified in 2009 and has since been found in increasing numbers of patients all over the world. As expected, cases of C. auris are on the rise in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated “Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat.” This is an opportunistic pathogen that hits critically ill patients and those with compromised immunity.

On March 29, 2019, CDC reported that confirmed clinical cases of C. auris in the United States have more than doubled over the past year, from 257 cases in 2018 to 587 cases with an additional 1,056 colonized patients identified as of February 2019. “Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Strains of C. auris in the United States have been linked to other parts of the world. U.S. C. auris cases are a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who recently received health care in a country where C. auris has been reported or a result of local spread after such an introduction.”

Case reports have found a mortality rate of up to 50% in patients with C. auris candidemia. The total number of cases is still small, but the trajectory is clear. The hunt is on in labs all over the world for optimal treatments and processes to handle outbreaks.

Jeniel Nett, MD, an infectious disease specialist, and a team of investigators at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have focused their research on the characteristics of C. auris and its progression in patients and in medical facilities.

According to Dr. Nett, it’s not clear why this emerging threat has cropped up in multiple locations globally. “Candida auris was first recognized in 2009, in Japan, and relatively quickly we saw emergence of this species in relatively distant locations,” she said, adding that independent clades in these locations ruled out transmission as the source of the multiple outbreaks. Antifungal resistance is an epidemiologic area of concern and increased antifungal use may be a contributor, she said.

Once established, the organism is persistent: “It is found on mattresses, on bedsheets, IV poles, and a lot of reusable equipment,” said Dr. Nett in an interview. “It appears to persist in the environment for weeks – maybe longer.” In addition, “it seems to behave differently than a lot of the Candida species that we see; it readily colonizes the skin” to a much greater extent than does other Candida species, she said. “This allows it to be transmitted readily person to person, particularly in the hospitalized setting.” However, it can also colonize both the urinary and respiratory tracts, she said.

Which patients are susceptible to C. auris candidemia? “Many of these patients have undergone multiple procedures; they may have undergone mechanical ventilation as well as different surgical procedures,” said Dr. Nett. Affected patients often have received many rounds of antibiotic and antifungal treatment as well, she said, and may have an underlying illness like diabetes or malignancy.

Studies of C. auris outbreaks have begun to appear in the literature and give clinicians some perspective on the progression of an outbreak and potential strategies for containment. A prospective cohort study of a large outbreak of C. auris was conducted by Alba Ruiz-Gaitán, MD, and her colleagues at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia, Spain (Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019 Apr;17[4]:295-305). The researchers followed 114 patients who were colonized with C. auris or had C. auris candidemia. The patients were compared with 114 case-matched controls within the hospital’s adult surgical and medical intensive care units over an 11-month period during the hospital’s protracted outbreak.

The investigators found a crude mortality rate of 58.5% at 30 days for patients with C. auris candidemia. All isolates in the study were completely resistant to fluconazole and had reduced susceptibility to voriconazole.

In critical care units at Hospital La Fe, investigators found C. auris on 25% of blood pressure cuffs, 10% of patient tables and keyboards, and 8% of infusion pumps.

Among the patients at Hospital La Fe, multivariable analysis revealed that those most likely to develop C. auris colonization or candidemia were individuals with polytrauma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Patients receiving parenteral nutrition (odds ratio, 3.49), mechanical ventilation (OR, 2.43), and especially those having indwelling central venous catheters (OR, 13.48) were more likely to be colonized or have candidemia as well, according to Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her coauthors.

Once identified, how should C. auris be treated? “The majority of strains – upward of 90% – are resistant to fluconazole,” said Dr. Nett. “Moreover, 30%-50% of them are resistant to another antifungal, often amphotericin B. The isolates that we see in the United States are most often susceptible to an echinocandin, and echinocandins remain the choice for treatment of Candida auris pending susceptibility tests.”

However, in Valencia, “The susceptibility to echinocandins presented interesting features. These antifungals were not fungicidal against C. auris,” wrote Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues. They found that for caspofungin, “most isolates presented a clear paradoxical growth after 24 hours of incubation.” Additionally, fungal growth was inhibited at lower caspofungin concentrations, but rebounded at higher levels. Similar patterns were seen for anidulafungin and micafungin, they said.

These findings meant that Hospital La Fe patients received initial treatment with echinocandins, with the addition of liposomal amphotericin B or isavuconazole if candidemia persisted or clinical response was not seen, wrote the investigators.

Patient presentation is similar to other forms of candidiasis, said Dr. Nett. “Patients often have fever, chills, leukocytosis, and this persists despite antibacterial therapy… If Candida auris is suspected, the first course of action would be to place the patient in isolation, and laboratory staff should be alerted regarding the diagnosis.”

Most large clinical laboratories, she said, can now detect C. auris. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight is the identification technique of choice, provided that the databases are updated.

Smaller laboratories that use phenotypic tests may misidentify C. auris as another Candida species, or even as Saccharomyces cerevisiae – common beer yeast. Facilities without matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization can find guidance for interpretation of phenotypic testing on the CDC website as well, said Dr. Nett.

After experiencing what they believe to be the largest C. auris outbreak at a single European hospital, Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her colleagues offered best-practice tips for treatment of patients with C. auris candidemia. These include removing mechanical devices as early as is safely practical; performing ophthalmologic examinations for endophthalmitis, a known C. auris complication; obtaining blood cultures every other day to track antimicrobial therapy to the point of sterilization; and searching for metastatic foci if blood cultures remain positive.

All instances of C. auris laboratory identification should be reported to the CDC at [email protected], and to local and state health agencies. The CDC recommends strict isolation and cleaning protocols, similar to those used for the spore-forming Clostridium difficile.

Dr. Nett reported funding support from the National Institutes of Health, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. She reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ruiz-Gaitán and her collaborators reported funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and University. They reported no conflicts of interest.

During Flu Season Risk of Heart Failure Rises

A study of > 450,000 adults has “confirmed the long-held notion” that flu and heart failure are connected. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (ARIC), led by a VA researcher, found influenza significantly increased the risk of hospitalization for heart failure.

Every flu season about 36,000 people die, and > 200,000 are hospitalized due to flu, which is known to be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Several mechanisms likely contribute: Some form of immunocompromise is thought to be a key link. But few studies, the researchers note, have explored the temporal association between influenza activity and hospitalizations, particularly those caused by heart failure.

In ARIC, the researchers analyzed hospitalization data for adults aged 35 to 84 years between 2010 and 2014 in geographically diverse communities in Mississippi, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Maryland. They correlated those data with reports of influenza activity from the CDC Surveillance Network.

A 5% monthly increase in influenza activity was associated with a 24% relative increase in heart failure hospitalization rates. Myocardial infarction hospitalizations did not rise significantly. The most pneumonia and influenza-associated deaths were during the 2012-2013 season, when influenza-like illness (ILI) activity was highest, and the fewest deaths occurred during 2011-2012, when ILI activity was lowest. The model suggests that in a month with high influenza activity, about 19% of hospitalizations could be attributable to influenza, the researchers say.

“The study’s findings support VA’s aggressive effort every year to provide veterans with influenza vaccine,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. Although the flu season is winding down, he added, it is not too late for veterans—and others—to get vaccinated.

A study of > 450,000 adults has “confirmed the long-held notion” that flu and heart failure are connected. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (ARIC), led by a VA researcher, found influenza significantly increased the risk of hospitalization for heart failure.

Every flu season about 36,000 people die, and > 200,000 are hospitalized due to flu, which is known to be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Several mechanisms likely contribute: Some form of immunocompromise is thought to be a key link. But few studies, the researchers note, have explored the temporal association between influenza activity and hospitalizations, particularly those caused by heart failure.

In ARIC, the researchers analyzed hospitalization data for adults aged 35 to 84 years between 2010 and 2014 in geographically diverse communities in Mississippi, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Maryland. They correlated those data with reports of influenza activity from the CDC Surveillance Network.

A 5% monthly increase in influenza activity was associated with a 24% relative increase in heart failure hospitalization rates. Myocardial infarction hospitalizations did not rise significantly. The most pneumonia and influenza-associated deaths were during the 2012-2013 season, when influenza-like illness (ILI) activity was highest, and the fewest deaths occurred during 2011-2012, when ILI activity was lowest. The model suggests that in a month with high influenza activity, about 19% of hospitalizations could be attributable to influenza, the researchers say.

“The study’s findings support VA’s aggressive effort every year to provide veterans with influenza vaccine,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. Although the flu season is winding down, he added, it is not too late for veterans—and others—to get vaccinated.

A study of > 450,000 adults has “confirmed the long-held notion” that flu and heart failure are connected. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (ARIC), led by a VA researcher, found influenza significantly increased the risk of hospitalization for heart failure.

Every flu season about 36,000 people die, and > 200,000 are hospitalized due to flu, which is known to be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events. Several mechanisms likely contribute: Some form of immunocompromise is thought to be a key link. But few studies, the researchers note, have explored the temporal association between influenza activity and hospitalizations, particularly those caused by heart failure.

In ARIC, the researchers analyzed hospitalization data for adults aged 35 to 84 years between 2010 and 2014 in geographically diverse communities in Mississippi, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Maryland. They correlated those data with reports of influenza activity from the CDC Surveillance Network.

A 5% monthly increase in influenza activity was associated with a 24% relative increase in heart failure hospitalization rates. Myocardial infarction hospitalizations did not rise significantly. The most pneumonia and influenza-associated deaths were during the 2012-2013 season, when influenza-like illness (ILI) activity was highest, and the fewest deaths occurred during 2011-2012, when ILI activity was lowest. The model suggests that in a month with high influenza activity, about 19% of hospitalizations could be attributable to influenza, the researchers say.

“The study’s findings support VA’s aggressive effort every year to provide veterans with influenza vaccine,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. Although the flu season is winding down, he added, it is not too late for veterans—and others—to get vaccinated.

Coughing Won’t Pay the Bills

ANSWER

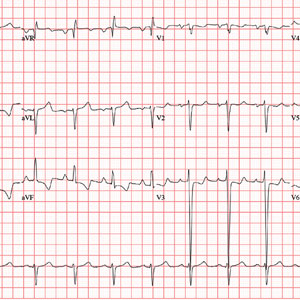

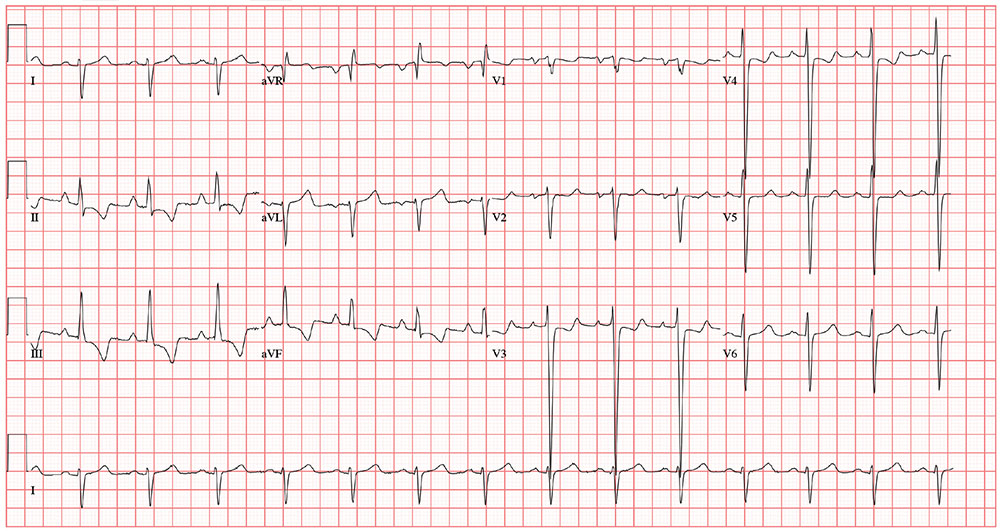

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, and right-axis deviation. Other findings include a prolonged QT interval and ST-T wave abnormalities in inferior and anterior distributions.

A P wave

A normal QTc interval is generally 350 to 440 ms; the patient’s QTc interval (477 ms) meets the criteria for prolonged QT. There are ST- and T-wave inversions in leads II, III, and aVF, consistent with inferior ischemia, with ST depressions in leads V3 and V4, which could suggest anterior ischemia. Such findings are also seen in a pulmonary disease pattern.

Further workup included a chest x-ray, laboratory testing, and an echocardiogram. The last revealed right lower lobe consolidation and a diffuse, dilated cardiomyopathy with mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, and right-axis deviation. Other findings include a prolonged QT interval and ST-T wave abnormalities in inferior and anterior distributions.

A P wave

A normal QTc interval is generally 350 to 440 ms; the patient’s QTc interval (477 ms) meets the criteria for prolonged QT. There are ST- and T-wave inversions in leads II, III, and aVF, consistent with inferior ischemia, with ST depressions in leads V3 and V4, which could suggest anterior ischemia. Such findings are also seen in a pulmonary disease pattern.

Further workup included a chest x-ray, laboratory testing, and an echocardiogram. The last revealed right lower lobe consolidation and a diffuse, dilated cardiomyopathy with mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, and right-axis deviation. Other findings include a prolonged QT interval and ST-T wave abnormalities in inferior and anterior distributions.

A P wave

A normal QTc interval is generally 350 to 440 ms; the patient’s QTc interval (477 ms) meets the criteria for prolonged QT. There are ST- and T-wave inversions in leads II, III, and aVF, consistent with inferior ischemia, with ST depressions in leads V3 and V4, which could suggest anterior ischemia. Such findings are also seen in a pulmonary disease pattern.

Further workup included a chest x-ray, laboratory testing, and an echocardiogram. The last revealed right lower lobe consolidation and a diffuse, dilated cardiomyopathy with mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

For the past 5 days, a 57-year-old man with “the flu” hasn’t been able to work. This morning, he awoke with chest tightness but denies chest pain. Because work has been busy lately, he just wants an antibiotic to help get him back on the job.

His primary symptom is a persistent, nonproductive cough that prevents him from getting a good night’s sleep. Associated symptoms include rhinorrhea, myalgias and arthralgias, and (for the first 3 days of illness) a low-grade fever. He’s been coughing so hard and for so long that his chest has begun to hurt. His cough is aggravated when lying down and somewhat relieved when sitting upright. He denies wheezing. He presents with specific requests: a chest x-ray to rule out pneumonia and prescriptions for azithromycin and codeine/acetaminophen (the latter for cough suppression).

Past medical history is remarkable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic bronchitis. Six months ago, a pulmonary function test revealed an FEV1 of 76% and an FEV1/FVC of 60%. He has chronic, mild to moderate shortness of breath with exertion. He has never had pneumonia or any anginal symptoms. Past surgical history is remarkable for an open reduction and internal fixation repair of his right tibia and an appendectomy. Current medications include acetaminophen for fever. He has used an albuterol inhaler in the past but has not had one for more than a year. He has no known drug allergies.

The patient is a crane operator for a large construction business. He is divorced and has an adult son with whom he has no contact. He’s been smoking 1.5 to 2 packs a day since he was 16. He used recreational marijuana until his employer began conducting random drug screenings 3 years ago. He drinks about 2 six-packs of beer a week—most of it on the weekends.

Family history is positive for COPD (mother), acute abdominal aortic dissection (father), and myocardial infarction (paternal grandfather).

The review of systems is positive for myalgias and arthralgias, which have been exacerbated by his recent illness. He denies a productive cough and any changes in heart rhythm and bowel or bladder function. He has no neurologic symptoms.

His vital signs include a blood pressure of 164/96 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 92% on room air; and temperature, 99.8°F.

Physical exam reveals an anxious, tired man in mild distress. His weight is 164 lb and his height, 70 in. The HEENT exam reveals ill-fitting corrective contact lenses, disheveled hair, and a nicotine-stained beard and mustache. His teeth are in poor repair; however, none are loose or missing. The neck is supple, and there is no thyromegaly. There is jugular venous distention, but not to the angle of the jaw. His respirations are shallow, requiring the use of accessory muscles. Deep inhalation causes uncontrollable coughing. Although there is anterior-posterior chest wall enlargement, it is insufficient to consider the patient barrel chested. Auscultation reveals diffuse, coarse rhonchi and end-expiratory wheezing.

The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm of 80 beats/min, with a soft diastolic murmur (grade II/VI) that is best heard along the left sternal border. There are no extra heart sounds or rubs. The abdomen is tender to deep palpation in the right upper quadrant, with no evidence of rebound to suggest peritonitis. There are no abdominal or femoral arterial bruits. The extremities demonstrate 2+ pulses bilaterally with 1+ pitting edema in the lower legs. The neurologic exam is grossly intact.

The previously undocumented murmur prompts you to order an ECG. It shows a ventricular rate of 83 beats/min; PR interval, 178 ms; QRS duration, 110 ms; QT/QTc interval, 406/477 ms; P axis, 67°; R axis, 126°; and T axis, –57°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

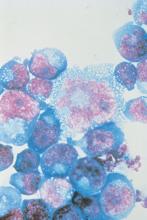

Dark spots in multiple locations

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Epinephrine linked with more refractory cardiogenic shock after acute MI

Background: Norepinephrine and epinephrine are the most commonly used vasopressors in clinical practice and in septic shock have been found to be equivalent in effectiveness. Their different physiological effects may influence their effectiveness in cardiogenic shock, and previous retrospective studies have suggested that epinephrine may have worse clinical outcomes in this setting.

Study design: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind study.

Setting: ICUs in nine French hospitals.

Synopsis: Adults (older than 18 years old) who suffered cardiogenic shock following successful revascularization after AMI were enrolled. Fifty-seven patients were randomly assigned to receive either norepinephrine or epinephrine with patients, nurses, and physicians unaware of which study drug was being used. The primary outcome variable was change in cardiac index within the first 72 hours, and refractory cardiogenic shock served as the main safety endpoint. This study was stopped early because of the higher risk of refractory cardiogenic shock noted in the epinephrine group, compared with that seen in the norepinephrine group (10 of 27 vs. 2 of 30; P = .011). There was no difference in evolution of cardiac index (P = .43) between the two groups. Potentially harmful metabolic and physiologic changes were noted in the epinephrine group including greater lactic acidosis and increased heart rate.

This study was underpowered for clinical endpoints because of the study’s early termination. It also did not include patients in cardiogenic shock from other causes, such as myositis or postcardiopulmonary bypass.

Bottom line: For patients in cardiogenic shock after AMI with successful reperfusion, epinephrine use was associated with increased refractory cardiogenic shock, compared with norepinephrine use.

Citation: Levy B et al. Epinephrine versus norepinephrine for cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 10;72(2):173-82.

Dr. Witt is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: Norepinephrine and epinephrine are the most commonly used vasopressors in clinical practice and in septic shock have been found to be equivalent in effectiveness. Their different physiological effects may influence their effectiveness in cardiogenic shock, and previous retrospective studies have suggested that epinephrine may have worse clinical outcomes in this setting.

Study design: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind study.

Setting: ICUs in nine French hospitals.

Synopsis: Adults (older than 18 years old) who suffered cardiogenic shock following successful revascularization after AMI were enrolled. Fifty-seven patients were randomly assigned to receive either norepinephrine or epinephrine with patients, nurses, and physicians unaware of which study drug was being used. The primary outcome variable was change in cardiac index within the first 72 hours, and refractory cardiogenic shock served as the main safety endpoint. This study was stopped early because of the higher risk of refractory cardiogenic shock noted in the epinephrine group, compared with that seen in the norepinephrine group (10 of 27 vs. 2 of 30; P = .011). There was no difference in evolution of cardiac index (P = .43) between the two groups. Potentially harmful metabolic and physiologic changes were noted in the epinephrine group including greater lactic acidosis and increased heart rate.

This study was underpowered for clinical endpoints because of the study’s early termination. It also did not include patients in cardiogenic shock from other causes, such as myositis or postcardiopulmonary bypass.

Bottom line: For patients in cardiogenic shock after AMI with successful reperfusion, epinephrine use was associated with increased refractory cardiogenic shock, compared with norepinephrine use.

Citation: Levy B et al. Epinephrine versus norepinephrine for cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 10;72(2):173-82.

Dr. Witt is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: Norepinephrine and epinephrine are the most commonly used vasopressors in clinical practice and in septic shock have been found to be equivalent in effectiveness. Their different physiological effects may influence their effectiveness in cardiogenic shock, and previous retrospective studies have suggested that epinephrine may have worse clinical outcomes in this setting.

Study design: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind study.

Setting: ICUs in nine French hospitals.

Synopsis: Adults (older than 18 years old) who suffered cardiogenic shock following successful revascularization after AMI were enrolled. Fifty-seven patients were randomly assigned to receive either norepinephrine or epinephrine with patients, nurses, and physicians unaware of which study drug was being used. The primary outcome variable was change in cardiac index within the first 72 hours, and refractory cardiogenic shock served as the main safety endpoint. This study was stopped early because of the higher risk of refractory cardiogenic shock noted in the epinephrine group, compared with that seen in the norepinephrine group (10 of 27 vs. 2 of 30; P = .011). There was no difference in evolution of cardiac index (P = .43) between the two groups. Potentially harmful metabolic and physiologic changes were noted in the epinephrine group including greater lactic acidosis and increased heart rate.

This study was underpowered for clinical endpoints because of the study’s early termination. It also did not include patients in cardiogenic shock from other causes, such as myositis or postcardiopulmonary bypass.

Bottom line: For patients in cardiogenic shock after AMI with successful reperfusion, epinephrine use was associated with increased refractory cardiogenic shock, compared with norepinephrine use.

Citation: Levy B et al. Epinephrine versus norepinephrine for cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jul 10;72(2):173-82.

Dr. Witt is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

ICYMI: Anti-CD4 antibody maintains viral suppression in HIV patients post ART