User login

The Evolution of the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Resident Pearl

- Residents should be aware of recent changes to the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology fellowship: the elimination of fellowship match exemptions for most applicants for the upcoming 2019-2020 academic year, the American Board of Medical Specialties approval of subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, and the likelihood of the first subspecialty certification examination in the next 2 years.

In Memoriam

Decline in CIN2+ in younger women after HPV vaccine introduced

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

FROM MMWR

A Critical Review of Periodic Health Screening Using Specific Screening Criteria: Part 3: Selected Diseases of the Genitourinary System

Back to the drawing board for MPN combo

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of ruxolitinib and decitabine will not proceed to a phase 3 trial in patients with accelerated or blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The combination demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 2 trial, but outcomes were not optimal, according to Raajit K. Rampal, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“[P]erhaps the outcomes might be favorable compared to standard induction chemotherapy regimens,” Dr. Rampal said. “Nonetheless, it’s clear that we still have a lot of work to do, and the outcomes are not optimal in these patients.”

However, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues are investigating the possibility of combining ruxolitinib and decitabine with other agents to treat patients with accelerated or blast phase MPNs.

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues presented results from the phase 2 trial in a poster at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

The trial (NCT02076191) enrolled 25 patients, 10 with accelerated phase MPN (10%-19% blasts) and 15 with blast phase MPN (at least 20% blasts). The patients’ median age was 71 years.

Patients had a median disease duration of 72.9 months. Six patients (25%) had received prior ruxolitinib, and two (8.3%) had received prior decitabine.

Treatment and safety

For the first cycle, patients received decitabine at 20 mg/m2 per day on days 8-12 and ruxolitinib at 25 mg twice a day on days 1-35. For subsequent cycles, patients received the same dose of decitabine on days 1-5 and ruxolitinib at 10 mg twice a day on days 6-28. Patients were treated until progression, withdrawal, or unacceptable toxicity.

“The adverse events we saw in this study were typical for this population, including fevers, mostly neutropenic fevers, as well as anemia and thrombocytopenia,” Dr. Rampal said.

Nonhematologic adverse events (AEs) included fatigue, abdominal pain, pneumonia, diarrhea, dizziness, and constipation. Hematologic AEs included anemia, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Response and survival

Eighteen patients were evaluable for response. Four patients were not evaluable because they withdrew from the study due to secondary AEs and completed one cycle of therapy or less, two patients did not have circulating blasts at baseline, and one patient refused further treatment.

Among the evaluable patients, nine (50%) achieved a partial response, including four patients with accelerated phase MPN and five with blast phase MPN.

Two patients (11.1%), one with accelerated phase MPN and one with blast phase MPN, achieved a complete response with incomplete count recovery.

The remaining seven patients (38.9%), five with blast phase MPN and two with accelerated phase MPN, did not respond.

The median overall survival was 7.6 months for the entire cohort, 9.7 months for patients with blast phase MPN, and 5.8 months for patients with accelerated phase MPN.

Based on these results, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues theorized that ruxolitinib plus decitabine might be improved by the addition of other agents. The researchers are currently investigating this possibility.

“The work for this trial really came out of preclinical work in the laboratory where we combined these drugs and saw efficacy in murine models,” Dr. Rampal said. “So we’re going back to the drawing board and looking at those again to see, ‘Can we come up with new rational combinations?’ ”

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Their study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and Incyte Corporation.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of ruxolitinib and decitabine will not proceed to a phase 3 trial in patients with accelerated or blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The combination demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 2 trial, but outcomes were not optimal, according to Raajit K. Rampal, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“[P]erhaps the outcomes might be favorable compared to standard induction chemotherapy regimens,” Dr. Rampal said. “Nonetheless, it’s clear that we still have a lot of work to do, and the outcomes are not optimal in these patients.”

However, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues are investigating the possibility of combining ruxolitinib and decitabine with other agents to treat patients with accelerated or blast phase MPNs.

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues presented results from the phase 2 trial in a poster at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

The trial (NCT02076191) enrolled 25 patients, 10 with accelerated phase MPN (10%-19% blasts) and 15 with blast phase MPN (at least 20% blasts). The patients’ median age was 71 years.

Patients had a median disease duration of 72.9 months. Six patients (25%) had received prior ruxolitinib, and two (8.3%) had received prior decitabine.

Treatment and safety

For the first cycle, patients received decitabine at 20 mg/m2 per day on days 8-12 and ruxolitinib at 25 mg twice a day on days 1-35. For subsequent cycles, patients received the same dose of decitabine on days 1-5 and ruxolitinib at 10 mg twice a day on days 6-28. Patients were treated until progression, withdrawal, or unacceptable toxicity.

“The adverse events we saw in this study were typical for this population, including fevers, mostly neutropenic fevers, as well as anemia and thrombocytopenia,” Dr. Rampal said.

Nonhematologic adverse events (AEs) included fatigue, abdominal pain, pneumonia, diarrhea, dizziness, and constipation. Hematologic AEs included anemia, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Response and survival

Eighteen patients were evaluable for response. Four patients were not evaluable because they withdrew from the study due to secondary AEs and completed one cycle of therapy or less, two patients did not have circulating blasts at baseline, and one patient refused further treatment.

Among the evaluable patients, nine (50%) achieved a partial response, including four patients with accelerated phase MPN and five with blast phase MPN.

Two patients (11.1%), one with accelerated phase MPN and one with blast phase MPN, achieved a complete response with incomplete count recovery.

The remaining seven patients (38.9%), five with blast phase MPN and two with accelerated phase MPN, did not respond.

The median overall survival was 7.6 months for the entire cohort, 9.7 months for patients with blast phase MPN, and 5.8 months for patients with accelerated phase MPN.

Based on these results, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues theorized that ruxolitinib plus decitabine might be improved by the addition of other agents. The researchers are currently investigating this possibility.

“The work for this trial really came out of preclinical work in the laboratory where we combined these drugs and saw efficacy in murine models,” Dr. Rampal said. “So we’re going back to the drawing board and looking at those again to see, ‘Can we come up with new rational combinations?’ ”

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Their study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and Incyte Corporation.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – The combination of ruxolitinib and decitabine will not proceed to a phase 3 trial in patients with accelerated or blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The combination demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 2 trial, but outcomes were not optimal, according to Raajit K. Rampal, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“[P]erhaps the outcomes might be favorable compared to standard induction chemotherapy regimens,” Dr. Rampal said. “Nonetheless, it’s clear that we still have a lot of work to do, and the outcomes are not optimal in these patients.”

However, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues are investigating the possibility of combining ruxolitinib and decitabine with other agents to treat patients with accelerated or blast phase MPNs.

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues presented results from the phase 2 trial in a poster at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

The trial (NCT02076191) enrolled 25 patients, 10 with accelerated phase MPN (10%-19% blasts) and 15 with blast phase MPN (at least 20% blasts). The patients’ median age was 71 years.

Patients had a median disease duration of 72.9 months. Six patients (25%) had received prior ruxolitinib, and two (8.3%) had received prior decitabine.

Treatment and safety

For the first cycle, patients received decitabine at 20 mg/m2 per day on days 8-12 and ruxolitinib at 25 mg twice a day on days 1-35. For subsequent cycles, patients received the same dose of decitabine on days 1-5 and ruxolitinib at 10 mg twice a day on days 6-28. Patients were treated until progression, withdrawal, or unacceptable toxicity.

“The adverse events we saw in this study were typical for this population, including fevers, mostly neutropenic fevers, as well as anemia and thrombocytopenia,” Dr. Rampal said.

Nonhematologic adverse events (AEs) included fatigue, abdominal pain, pneumonia, diarrhea, dizziness, and constipation. Hematologic AEs included anemia, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Response and survival

Eighteen patients were evaluable for response. Four patients were not evaluable because they withdrew from the study due to secondary AEs and completed one cycle of therapy or less, two patients did not have circulating blasts at baseline, and one patient refused further treatment.

Among the evaluable patients, nine (50%) achieved a partial response, including four patients with accelerated phase MPN and five with blast phase MPN.

Two patients (11.1%), one with accelerated phase MPN and one with blast phase MPN, achieved a complete response with incomplete count recovery.

The remaining seven patients (38.9%), five with blast phase MPN and two with accelerated phase MPN, did not respond.

The median overall survival was 7.6 months for the entire cohort, 9.7 months for patients with blast phase MPN, and 5.8 months for patients with accelerated phase MPN.

Based on these results, Dr. Rampal and his colleagues theorized that ruxolitinib plus decitabine might be improved by the addition of other agents. The researchers are currently investigating this possibility.

“The work for this trial really came out of preclinical work in the laboratory where we combined these drugs and saw efficacy in murine models,” Dr. Rampal said. “So we’re going back to the drawing board and looking at those again to see, ‘Can we come up with new rational combinations?’ ”

Dr. Rampal and his colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest. Their study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and Incyte Corporation.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

REPORTING FROM ALF 2019

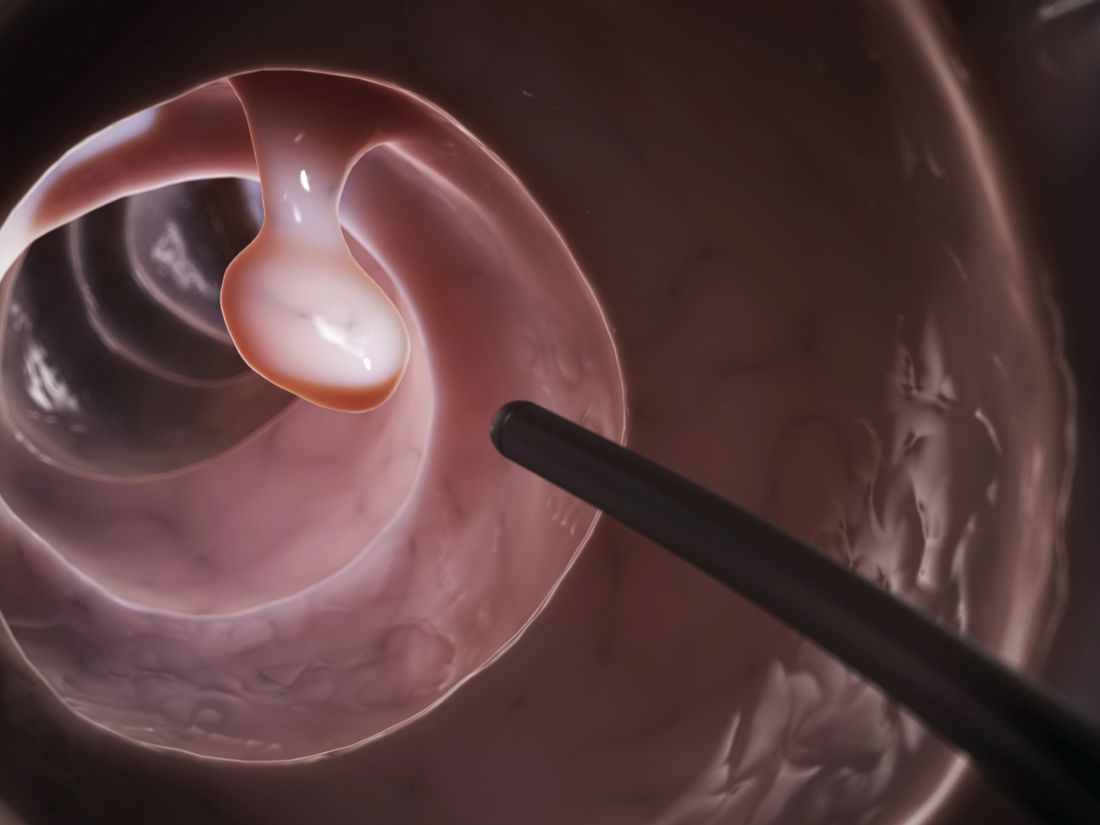

Polyp detection rates during colonoscopy similar among endoscopists

“We sought to assess the association between endoscopist characteristics and adenoma detection rates [ADRs] and proximal sessile serrated polyp detection rates [pSSPDRs],” wrote Shashank Sarvepalli, MD, MS, of the Cleveland Clinic along with his colleagues. The findings were reported in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 16,089 patients who underwent screening colonoscopies that were conducted by 56 endoscopists. Data were obtained from the Cleveland Clinic health system during 2015-2017.

Dr. Sarvepalli and his colleagues analyzed seven surgeon characteristics, including time since completion of training, number of colonoscopies performed annually, specialty, and practice setting. Subsequently, they examined the relationships between ADRs and pSSPDRs and these parameters.

“Only patients undergoing normal-risk screening colonoscopies and colonoscopies performed by clinicians who performed more than 100 normal-risk screening colonoscopies during the study period were included,” the researchers wrote.

After analysis, the researchers found that ADR was not significantly associated with any of the characteristics, while pSSPDR was significantly associated with number of years in practice (odds ratio per increment of 10 years, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.89; P less than .001) and annual colonoscopies completed (OR per 50 colonoscopies annually, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09; P = .02).

“After adjusting for additional factors, no difference in detection based on endoscopist characteristics was found,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, the team reported that the findings could be prone to exclusions and misreporting.

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sarvepalli S et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0564.

“We sought to assess the association between endoscopist characteristics and adenoma detection rates [ADRs] and proximal sessile serrated polyp detection rates [pSSPDRs],” wrote Shashank Sarvepalli, MD, MS, of the Cleveland Clinic along with his colleagues. The findings were reported in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 16,089 patients who underwent screening colonoscopies that were conducted by 56 endoscopists. Data were obtained from the Cleveland Clinic health system during 2015-2017.

Dr. Sarvepalli and his colleagues analyzed seven surgeon characteristics, including time since completion of training, number of colonoscopies performed annually, specialty, and practice setting. Subsequently, they examined the relationships between ADRs and pSSPDRs and these parameters.

“Only patients undergoing normal-risk screening colonoscopies and colonoscopies performed by clinicians who performed more than 100 normal-risk screening colonoscopies during the study period were included,” the researchers wrote.

After analysis, the researchers found that ADR was not significantly associated with any of the characteristics, while pSSPDR was significantly associated with number of years in practice (odds ratio per increment of 10 years, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.89; P less than .001) and annual colonoscopies completed (OR per 50 colonoscopies annually, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09; P = .02).

“After adjusting for additional factors, no difference in detection based on endoscopist characteristics was found,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, the team reported that the findings could be prone to exclusions and misreporting.

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sarvepalli S et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0564.

“We sought to assess the association between endoscopist characteristics and adenoma detection rates [ADRs] and proximal sessile serrated polyp detection rates [pSSPDRs],” wrote Shashank Sarvepalli, MD, MS, of the Cleveland Clinic along with his colleagues. The findings were reported in JAMA Surgery.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 16,089 patients who underwent screening colonoscopies that were conducted by 56 endoscopists. Data were obtained from the Cleveland Clinic health system during 2015-2017.

Dr. Sarvepalli and his colleagues analyzed seven surgeon characteristics, including time since completion of training, number of colonoscopies performed annually, specialty, and practice setting. Subsequently, they examined the relationships between ADRs and pSSPDRs and these parameters.

“Only patients undergoing normal-risk screening colonoscopies and colonoscopies performed by clinicians who performed more than 100 normal-risk screening colonoscopies during the study period were included,” the researchers wrote.

After analysis, the researchers found that ADR was not significantly associated with any of the characteristics, while pSSPDR was significantly associated with number of years in practice (odds ratio per increment of 10 years, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.89; P less than .001) and annual colonoscopies completed (OR per 50 colonoscopies annually, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09; P = .02).

“After adjusting for additional factors, no difference in detection based on endoscopist characteristics was found,” they added.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, the team reported that the findings could be prone to exclusions and misreporting.

No funding sources were reported, and the authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sarvepalli S et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Apr 17. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0564.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Reviews of Audiovisual Materials

Physicians discuss bringing cultural humility to medicine

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019