User login

Hydroxychloroquine adherence in SLE: worse than you thought

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine office measurement of hydroxychloroquine blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients accomplishes two major objectives, Nathalie Costedoat-Chalumeau, MD, asserted at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

First, measuring hydroxychloroquine levels identifies the surprisingly large number of individuals who are severely nonadherent to this cornerstone of lupus therapy despite its excellent benefit/risk ratio. Also, serial measurements coupled with brief counseling have been shown to boost poor adherence rates, noted Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau, professor of rheumatology at Paris Descartes University.

Numerous studies have documented startlingly low adherence to hydroxychloroquine among SLE patients. Some of the same studies show prescribing physicians are often clueless as to their patients’ adherence or lack thereof.

Just how bad is the adherence problem? A recent study of 10,406 Medicaid patients with SLE who started on hydroxychloroquine showed that 85% of them were nonadherent as defined by pharmacy refill data, indicating insufficient medication on hand to cover a minimum of 80% of days during at least 1 year of follow-up.

In a novel finding, the investigators also broke down the Medicaid data month by month and identified four broad patterns of adherence/nonadherence. A total of 17% of patients were persistently adherent throughout the first year after the drug was dispensed. Another 36% were persistent nonadherers right from the get-go. A further 24% remained partially adherent, dropping down to a plateau of 30%-40% monthly adherence after the first couple of months and staying there. And 23% dropped steadily from roughly 50% adherence at month 3 to nearly total nonadherence from month 9 onward. Overall, adherence in the Medicaid cohort declined over the course of the first year (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Oct;48[2]:205-13).

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau was the lead investigator in a large French multicenter clinical trial known as the PLUS Study, which established that increasing the hydroxychloroquine daily dose to raise blood levels to a target of at least 1,000 ng/mL didn’t reduce the risk of flares (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[11]:1786-92).

“So there is no reason to use blood drug measurements to adjust hydroxychloroquine daily dose or blood levels to prevent SLE flares. But drug levels teach us something regarding adherence,” she said.

Why routinely measuring hydroxychloroquine levels matters

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau and other investigators have shown that whole blood drug levels below 200 ng/mL indicate a patient is severely nonadherent. In various studies, that’s 7%-29% of SLE patients who are supposedly on hydroxychloroquine.

Also, investigators at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, have analyzed prospective data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort and determined that at the first clinic visit after going on a maximum of 400 mg/day of hydroxychloroquine, only 44% of participants had a blood drug level above the 500-ng/mL threshold indicative of adherence.

Importantly, however, the Hopkins researchers also demonstrated that with repeated brief counseling of nonadherent patients as to why hydroxychloroquine is the most important medication they take for their SLE, adherence climbed in stepwise fashion with each visit in which the drug blood level was assessed: With no prior measurement, adherence was 56%; with one prior measurement, it jumped to 69%; with two, 77% of patients were adherent to hydroxychloroquine; and with three or more prior blood level checks, adherence rose to 80% (J Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;42[11]:2092-7).

It is well established that hydroxychloroquine prevents SLE flares, protects against thrombotic events, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and lupus-induced organ damage, and improves survival. Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau’s final words on hydroxychloroquine adherence: ”Drugs don’t work in people who don’t take them.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine office measurement of hydroxychloroquine blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients accomplishes two major objectives, Nathalie Costedoat-Chalumeau, MD, asserted at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

First, measuring hydroxychloroquine levels identifies the surprisingly large number of individuals who are severely nonadherent to this cornerstone of lupus therapy despite its excellent benefit/risk ratio. Also, serial measurements coupled with brief counseling have been shown to boost poor adherence rates, noted Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau, professor of rheumatology at Paris Descartes University.

Numerous studies have documented startlingly low adherence to hydroxychloroquine among SLE patients. Some of the same studies show prescribing physicians are often clueless as to their patients’ adherence or lack thereof.

Just how bad is the adherence problem? A recent study of 10,406 Medicaid patients with SLE who started on hydroxychloroquine showed that 85% of them were nonadherent as defined by pharmacy refill data, indicating insufficient medication on hand to cover a minimum of 80% of days during at least 1 year of follow-up.

In a novel finding, the investigators also broke down the Medicaid data month by month and identified four broad patterns of adherence/nonadherence. A total of 17% of patients were persistently adherent throughout the first year after the drug was dispensed. Another 36% were persistent nonadherers right from the get-go. A further 24% remained partially adherent, dropping down to a plateau of 30%-40% monthly adherence after the first couple of months and staying there. And 23% dropped steadily from roughly 50% adherence at month 3 to nearly total nonadherence from month 9 onward. Overall, adherence in the Medicaid cohort declined over the course of the first year (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Oct;48[2]:205-13).

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau was the lead investigator in a large French multicenter clinical trial known as the PLUS Study, which established that increasing the hydroxychloroquine daily dose to raise blood levels to a target of at least 1,000 ng/mL didn’t reduce the risk of flares (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[11]:1786-92).

“So there is no reason to use blood drug measurements to adjust hydroxychloroquine daily dose or blood levels to prevent SLE flares. But drug levels teach us something regarding adherence,” she said.

Why routinely measuring hydroxychloroquine levels matters

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau and other investigators have shown that whole blood drug levels below 200 ng/mL indicate a patient is severely nonadherent. In various studies, that’s 7%-29% of SLE patients who are supposedly on hydroxychloroquine.

Also, investigators at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, have analyzed prospective data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort and determined that at the first clinic visit after going on a maximum of 400 mg/day of hydroxychloroquine, only 44% of participants had a blood drug level above the 500-ng/mL threshold indicative of adherence.

Importantly, however, the Hopkins researchers also demonstrated that with repeated brief counseling of nonadherent patients as to why hydroxychloroquine is the most important medication they take for their SLE, adherence climbed in stepwise fashion with each visit in which the drug blood level was assessed: With no prior measurement, adherence was 56%; with one prior measurement, it jumped to 69%; with two, 77% of patients were adherent to hydroxychloroquine; and with three or more prior blood level checks, adherence rose to 80% (J Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;42[11]:2092-7).

It is well established that hydroxychloroquine prevents SLE flares, protects against thrombotic events, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and lupus-induced organ damage, and improves survival. Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau’s final words on hydroxychloroquine adherence: ”Drugs don’t work in people who don’t take them.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine office measurement of hydroxychloroquine blood levels in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients accomplishes two major objectives, Nathalie Costedoat-Chalumeau, MD, asserted at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

First, measuring hydroxychloroquine levels identifies the surprisingly large number of individuals who are severely nonadherent to this cornerstone of lupus therapy despite its excellent benefit/risk ratio. Also, serial measurements coupled with brief counseling have been shown to boost poor adherence rates, noted Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau, professor of rheumatology at Paris Descartes University.

Numerous studies have documented startlingly low adherence to hydroxychloroquine among SLE patients. Some of the same studies show prescribing physicians are often clueless as to their patients’ adherence or lack thereof.

Just how bad is the adherence problem? A recent study of 10,406 Medicaid patients with SLE who started on hydroxychloroquine showed that 85% of them were nonadherent as defined by pharmacy refill data, indicating insufficient medication on hand to cover a minimum of 80% of days during at least 1 year of follow-up.

In a novel finding, the investigators also broke down the Medicaid data month by month and identified four broad patterns of adherence/nonadherence. A total of 17% of patients were persistently adherent throughout the first year after the drug was dispensed. Another 36% were persistent nonadherers right from the get-go. A further 24% remained partially adherent, dropping down to a plateau of 30%-40% monthly adherence after the first couple of months and staying there. And 23% dropped steadily from roughly 50% adherence at month 3 to nearly total nonadherence from month 9 onward. Overall, adherence in the Medicaid cohort declined over the course of the first year (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Oct;48[2]:205-13).

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau was the lead investigator in a large French multicenter clinical trial known as the PLUS Study, which established that increasing the hydroxychloroquine daily dose to raise blood levels to a target of at least 1,000 ng/mL didn’t reduce the risk of flares (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72[11]:1786-92).

“So there is no reason to use blood drug measurements to adjust hydroxychloroquine daily dose or blood levels to prevent SLE flares. But drug levels teach us something regarding adherence,” she said.

Why routinely measuring hydroxychloroquine levels matters

Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau and other investigators have shown that whole blood drug levels below 200 ng/mL indicate a patient is severely nonadherent. In various studies, that’s 7%-29% of SLE patients who are supposedly on hydroxychloroquine.

Also, investigators at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, have analyzed prospective data from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort and determined that at the first clinic visit after going on a maximum of 400 mg/day of hydroxychloroquine, only 44% of participants had a blood drug level above the 500-ng/mL threshold indicative of adherence.

Importantly, however, the Hopkins researchers also demonstrated that with repeated brief counseling of nonadherent patients as to why hydroxychloroquine is the most important medication they take for their SLE, adherence climbed in stepwise fashion with each visit in which the drug blood level was assessed: With no prior measurement, adherence was 56%; with one prior measurement, it jumped to 69%; with two, 77% of patients were adherent to hydroxychloroquine; and with three or more prior blood level checks, adherence rose to 80% (J Rheumatol. 2015 Nov;42[11]:2092-7).

It is well established that hydroxychloroquine prevents SLE flares, protects against thrombotic events, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and lupus-induced organ damage, and improves survival. Dr. Costedoat-Chalumeau’s final words on hydroxychloroquine adherence: ”Drugs don’t work in people who don’t take them.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

REPORTING FROM LUPUS 2019

Sorafenib plus GCLAM held safe in AML, MDS phase-1 study

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – A five-drug regimen was deemed safe in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and it appeared to be effective regardless of patients’ FLT3 status.

Researchers tested this regimen – sorafenib plus granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF), cladribine, high-dose cytarabine, and mitoxantrone (GCLAM) – in a phase 1 trial.

Kelsey-Leigh Garcia, a clinical research coordinator at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, and her colleagues presented the results at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

“The background for doing this study was our institutional results of GCLAM [Leukemia. 2018 Nov;32(11):2352-62] that showed a higher minimal residual disease–negative complete response rate than 7+3 [cytarabine continuously for 7 days, along with short infusions of an anthracycline on each of the first 3 days] and an international study by Röllig that showed the addition of sorafenib to 7+3 increased event-free survival versus [7+3 and] placebo [Lancet Oncol. 2015 Dec;16(16):1691-9],” Ms. Garcia said.

“GCLAM is the standard backbone at our institution, and we wanted to ask the question, ‘If we add sorafenib, can this improve upon the results of GCLAM?’ ” said Anna Halpern, MD, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle and principal investigator of the phase 1 trial.

The trial (NCT02728050) included 47 patients, 39 with AML and 8 with MDS. Patients were aged 60 years or younger and had a median age of 48. They had a median treatment-related mortality score of 1.76 (range, 0.19-12.26). A total of 11 patients (23%) had FLT3-ITD, and 4 (9%) had FLT3-TKD.

Treatment and toxicity

For induction, patients received G-CSF at 5 mcg/kg on days 0-5, cladribine at 5 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and cytarabine at 2 g/m2 on days 1-5. Mitoxantrone was given at 10 mg/m2, 12 mg/m2, 15 mg/m2, or 18 mg/m2 on days 1-3. Sorafenib was given at 200 mg twice daily, 400 mg in the morning and 200 mg in the afternoon, or 400 mg b.i.d. on days 10-19.

For consolidation, patients could receive up to four cycles of G-CSF, cladribine, and cytarabine plus sorafenib on days 8-27. Patients who did not proceed to transplant could receive 12 months of sorafenib as maintenance therapy.

There were four dose-limiting toxicities.

- Grade 4 intracranial hemorrhage with mitoxantrone at 12 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 prolonged count recovery with mitoxantrone at 15 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 sepsis, Sweet syndrome, and Bell’s palsy with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 3 cardiomyopathy and acute pericarditis with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 400 mg b.i.d.

However, these toxicities did not define the maximum-tolerated dose. Therefore, the recommended phase 2 dose of mitoxantrone is 18 mg/m2, and the recommended phase 2 dose of sorafenib is 400 mg b.i.d.

There were no grade 5 treatment-related adverse events. Grade 3 events included febrile neutropenia (90%), maculopapular rash (20%), infections (10%), hand-foot syndrome (2%), and diarrhea (1%). Grade 4 events included sepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, and oral mucositis (all 1%).

Response and survival

Among the 46 evaluable patients, 83% achieved a complete response, 78% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response, and 4% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response with incomplete count recovery. A morphological leukemia-free state was achieved by 4% of patients, and 8% had resistant disease.

Fifty-nine percent of patients went on to transplant. The median overall survival had not been reached at a median follow-up of 10 months.

The researchers compared outcomes in this trial with outcomes in a cohort of patients who had received GCLAM alone, and there were no significant differences in overall survival or event-free survival.

“The trial wasn’t powered, necessarily, for efficacy, but we compared these results to our historical cohort of medically matched and age-matched patients treated with GCLAM alone and, so far, found no differences in survival between the two groups,” Dr. Halpern said.

She noted, however, that follow-up was short in the sorafenib trial, and it included patients treated with all dose levels of sorafenib and mitoxantrone.

A phase 2 study of sorafenib plus GCLAM in newly diagnosed AML or high-risk MDS is now underway.

Dr. Halpern and Ms. Garcia reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The phase 1 trial was sponsored by the University of Washington in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, and funding was provided by Bayer.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – A five-drug regimen was deemed safe in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and it appeared to be effective regardless of patients’ FLT3 status.

Researchers tested this regimen – sorafenib plus granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF), cladribine, high-dose cytarabine, and mitoxantrone (GCLAM) – in a phase 1 trial.

Kelsey-Leigh Garcia, a clinical research coordinator at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, and her colleagues presented the results at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

“The background for doing this study was our institutional results of GCLAM [Leukemia. 2018 Nov;32(11):2352-62] that showed a higher minimal residual disease–negative complete response rate than 7+3 [cytarabine continuously for 7 days, along with short infusions of an anthracycline on each of the first 3 days] and an international study by Röllig that showed the addition of sorafenib to 7+3 increased event-free survival versus [7+3 and] placebo [Lancet Oncol. 2015 Dec;16(16):1691-9],” Ms. Garcia said.

“GCLAM is the standard backbone at our institution, and we wanted to ask the question, ‘If we add sorafenib, can this improve upon the results of GCLAM?’ ” said Anna Halpern, MD, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle and principal investigator of the phase 1 trial.

The trial (NCT02728050) included 47 patients, 39 with AML and 8 with MDS. Patients were aged 60 years or younger and had a median age of 48. They had a median treatment-related mortality score of 1.76 (range, 0.19-12.26). A total of 11 patients (23%) had FLT3-ITD, and 4 (9%) had FLT3-TKD.

Treatment and toxicity

For induction, patients received G-CSF at 5 mcg/kg on days 0-5, cladribine at 5 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and cytarabine at 2 g/m2 on days 1-5. Mitoxantrone was given at 10 mg/m2, 12 mg/m2, 15 mg/m2, or 18 mg/m2 on days 1-3. Sorafenib was given at 200 mg twice daily, 400 mg in the morning and 200 mg in the afternoon, or 400 mg b.i.d. on days 10-19.

For consolidation, patients could receive up to four cycles of G-CSF, cladribine, and cytarabine plus sorafenib on days 8-27. Patients who did not proceed to transplant could receive 12 months of sorafenib as maintenance therapy.

There were four dose-limiting toxicities.

- Grade 4 intracranial hemorrhage with mitoxantrone at 12 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 prolonged count recovery with mitoxantrone at 15 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 sepsis, Sweet syndrome, and Bell’s palsy with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 3 cardiomyopathy and acute pericarditis with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 400 mg b.i.d.

However, these toxicities did not define the maximum-tolerated dose. Therefore, the recommended phase 2 dose of mitoxantrone is 18 mg/m2, and the recommended phase 2 dose of sorafenib is 400 mg b.i.d.

There were no grade 5 treatment-related adverse events. Grade 3 events included febrile neutropenia (90%), maculopapular rash (20%), infections (10%), hand-foot syndrome (2%), and diarrhea (1%). Grade 4 events included sepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, and oral mucositis (all 1%).

Response and survival

Among the 46 evaluable patients, 83% achieved a complete response, 78% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response, and 4% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response with incomplete count recovery. A morphological leukemia-free state was achieved by 4% of patients, and 8% had resistant disease.

Fifty-nine percent of patients went on to transplant. The median overall survival had not been reached at a median follow-up of 10 months.

The researchers compared outcomes in this trial with outcomes in a cohort of patients who had received GCLAM alone, and there were no significant differences in overall survival or event-free survival.

“The trial wasn’t powered, necessarily, for efficacy, but we compared these results to our historical cohort of medically matched and age-matched patients treated with GCLAM alone and, so far, found no differences in survival between the two groups,” Dr. Halpern said.

She noted, however, that follow-up was short in the sorafenib trial, and it included patients treated with all dose levels of sorafenib and mitoxantrone.

A phase 2 study of sorafenib plus GCLAM in newly diagnosed AML or high-risk MDS is now underway.

Dr. Halpern and Ms. Garcia reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The phase 1 trial was sponsored by the University of Washington in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, and funding was provided by Bayer.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – A five-drug regimen was deemed safe in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and it appeared to be effective regardless of patients’ FLT3 status.

Researchers tested this regimen – sorafenib plus granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF), cladribine, high-dose cytarabine, and mitoxantrone (GCLAM) – in a phase 1 trial.

Kelsey-Leigh Garcia, a clinical research coordinator at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, and her colleagues presented the results at the Acute Leukemia Forum of Hemedicus.

“The background for doing this study was our institutional results of GCLAM [Leukemia. 2018 Nov;32(11):2352-62] that showed a higher minimal residual disease–negative complete response rate than 7+3 [cytarabine continuously for 7 days, along with short infusions of an anthracycline on each of the first 3 days] and an international study by Röllig that showed the addition of sorafenib to 7+3 increased event-free survival versus [7+3 and] placebo [Lancet Oncol. 2015 Dec;16(16):1691-9],” Ms. Garcia said.

“GCLAM is the standard backbone at our institution, and we wanted to ask the question, ‘If we add sorafenib, can this improve upon the results of GCLAM?’ ” said Anna Halpern, MD, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle and principal investigator of the phase 1 trial.

The trial (NCT02728050) included 47 patients, 39 with AML and 8 with MDS. Patients were aged 60 years or younger and had a median age of 48. They had a median treatment-related mortality score of 1.76 (range, 0.19-12.26). A total of 11 patients (23%) had FLT3-ITD, and 4 (9%) had FLT3-TKD.

Treatment and toxicity

For induction, patients received G-CSF at 5 mcg/kg on days 0-5, cladribine at 5 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and cytarabine at 2 g/m2 on days 1-5. Mitoxantrone was given at 10 mg/m2, 12 mg/m2, 15 mg/m2, or 18 mg/m2 on days 1-3. Sorafenib was given at 200 mg twice daily, 400 mg in the morning and 200 mg in the afternoon, or 400 mg b.i.d. on days 10-19.

For consolidation, patients could receive up to four cycles of G-CSF, cladribine, and cytarabine plus sorafenib on days 8-27. Patients who did not proceed to transplant could receive 12 months of sorafenib as maintenance therapy.

There were four dose-limiting toxicities.

- Grade 4 intracranial hemorrhage with mitoxantrone at 12 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 prolonged count recovery with mitoxantrone at 15 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 4 sepsis, Sweet syndrome, and Bell’s palsy with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 200 mg b.i.d.

- Grade 3 cardiomyopathy and acute pericarditis with mitoxantrone at 18 mg/m2 and sorafenib at 400 mg b.i.d.

However, these toxicities did not define the maximum-tolerated dose. Therefore, the recommended phase 2 dose of mitoxantrone is 18 mg/m2, and the recommended phase 2 dose of sorafenib is 400 mg b.i.d.

There were no grade 5 treatment-related adverse events. Grade 3 events included febrile neutropenia (90%), maculopapular rash (20%), infections (10%), hand-foot syndrome (2%), and diarrhea (1%). Grade 4 events included sepsis, intracranial hemorrhage, and oral mucositis (all 1%).

Response and survival

Among the 46 evaluable patients, 83% achieved a complete response, 78% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response, and 4% had a minimal residual disease–negative complete response with incomplete count recovery. A morphological leukemia-free state was achieved by 4% of patients, and 8% had resistant disease.

Fifty-nine percent of patients went on to transplant. The median overall survival had not been reached at a median follow-up of 10 months.

The researchers compared outcomes in this trial with outcomes in a cohort of patients who had received GCLAM alone, and there were no significant differences in overall survival or event-free survival.

“The trial wasn’t powered, necessarily, for efficacy, but we compared these results to our historical cohort of medically matched and age-matched patients treated with GCLAM alone and, so far, found no differences in survival between the two groups,” Dr. Halpern said.

She noted, however, that follow-up was short in the sorafenib trial, and it included patients treated with all dose levels of sorafenib and mitoxantrone.

A phase 2 study of sorafenib plus GCLAM in newly diagnosed AML or high-risk MDS is now underway.

Dr. Halpern and Ms. Garcia reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The phase 1 trial was sponsored by the University of Washington in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, and funding was provided by Bayer.

The Acute Leukemia Forum is held by Hemedicus, which is owned by the same company as this news organization.

REPORTING FROM ALF 2019

‘Type II’ SLE assessment catches what matters to patients

SAN FRANCISCO – For almost a year, lupus patients at Duke University in Durham, N.C., have been getting two physician global assessments, the usual one for classic “type I” disease, and a new one for nonspecific “type II” symptoms: fatigue, widespread pain, depression, sleep disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction.

It’s often the type II problems that affect patients the most, and what they are most concerned about; formally assessing them with the type II physician global assessment (PGA) – a 0- to 3-point visual analog scale – ensures they aren’t overlooked, said Jennifer Rogers, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology at Duke.

It “forces us to address these symptoms,” she said, and the approach seems to be working, according to a study Dr. Rogers presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

In the 5 months leading up to implementation of the PGA II in late spring 2018, type II problems had treatment recommendations in patients’ charts just 53% of the time; the number rose to 89% of the time during the PGA II’s first 5 months (P = .03). Type II PGA scores correlated strongly with patient-reported fibromyalgia and depression symptoms, but did not correlate with PGA scores for type I symptoms, such as nephritis and arthritis.

Type II problems are common in lupus. Patients’ joints might be fine, and their kidney disease in remission, but they can still feel miserable, and will often blame it on a lupus flare. Physicians who disagree end up at odds with their patients, Dr. Rogers explained.

“We decided to rethink how we address these patients, and came up with this new type I, type II categorization.” Now, when paints complain of brain fog, for example, “I say ‘yes, this is your lupus. I believe you,’ but we don’t need to give you more steroids or very expensive immunosuppressives for this. What you need to do is take your Cymbalta, work on your exercise, and maybe see your therapist,” she said.

It validates what people are going through, and builds trust. “Patients like it; they feel heard, and I walk out of the room, and I feel better,” she said.

During its first 5 months, 197 patients had PGAs for type II symptoms, along with type I PGAs. The average age of the patients was 46 years, and 92% were women.

Patients with predominately type II symptoms were more likely than were those with predominately type I disease to be depressed (84% versus 39%), and they reported higher lupus activity, greater symptom severity, and more severe fibromyalgia. The differences were statistically significant.

Type II treatments included medications in 60% of cases, exercise or physical therapy in almost 60% of cases, sleep studies or help with sleep hygiene in about 35%, and psychiatric or psychological referral in almost 20%. Less than 5% of patients were referred to a pain clinic.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Rogers didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rogers J et al. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6[suppl 1]: Abstract 102. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2019-lsm.102

SAN FRANCISCO – For almost a year, lupus patients at Duke University in Durham, N.C., have been getting two physician global assessments, the usual one for classic “type I” disease, and a new one for nonspecific “type II” symptoms: fatigue, widespread pain, depression, sleep disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction.

It’s often the type II problems that affect patients the most, and what they are most concerned about; formally assessing them with the type II physician global assessment (PGA) – a 0- to 3-point visual analog scale – ensures they aren’t overlooked, said Jennifer Rogers, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology at Duke.

It “forces us to address these symptoms,” she said, and the approach seems to be working, according to a study Dr. Rogers presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

In the 5 months leading up to implementation of the PGA II in late spring 2018, type II problems had treatment recommendations in patients’ charts just 53% of the time; the number rose to 89% of the time during the PGA II’s first 5 months (P = .03). Type II PGA scores correlated strongly with patient-reported fibromyalgia and depression symptoms, but did not correlate with PGA scores for type I symptoms, such as nephritis and arthritis.

Type II problems are common in lupus. Patients’ joints might be fine, and their kidney disease in remission, but they can still feel miserable, and will often blame it on a lupus flare. Physicians who disagree end up at odds with their patients, Dr. Rogers explained.

“We decided to rethink how we address these patients, and came up with this new type I, type II categorization.” Now, when paints complain of brain fog, for example, “I say ‘yes, this is your lupus. I believe you,’ but we don’t need to give you more steroids or very expensive immunosuppressives for this. What you need to do is take your Cymbalta, work on your exercise, and maybe see your therapist,” she said.

It validates what people are going through, and builds trust. “Patients like it; they feel heard, and I walk out of the room, and I feel better,” she said.

During its first 5 months, 197 patients had PGAs for type II symptoms, along with type I PGAs. The average age of the patients was 46 years, and 92% were women.

Patients with predominately type II symptoms were more likely than were those with predominately type I disease to be depressed (84% versus 39%), and they reported higher lupus activity, greater symptom severity, and more severe fibromyalgia. The differences were statistically significant.

Type II treatments included medications in 60% of cases, exercise or physical therapy in almost 60% of cases, sleep studies or help with sleep hygiene in about 35%, and psychiatric or psychological referral in almost 20%. Less than 5% of patients were referred to a pain clinic.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Rogers didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rogers J et al. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6[suppl 1]: Abstract 102. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2019-lsm.102

SAN FRANCISCO – For almost a year, lupus patients at Duke University in Durham, N.C., have been getting two physician global assessments, the usual one for classic “type I” disease, and a new one for nonspecific “type II” symptoms: fatigue, widespread pain, depression, sleep disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction.

It’s often the type II problems that affect patients the most, and what they are most concerned about; formally assessing them with the type II physician global assessment (PGA) – a 0- to 3-point visual analog scale – ensures they aren’t overlooked, said Jennifer Rogers, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology at Duke.

It “forces us to address these symptoms,” she said, and the approach seems to be working, according to a study Dr. Rogers presented at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

In the 5 months leading up to implementation of the PGA II in late spring 2018, type II problems had treatment recommendations in patients’ charts just 53% of the time; the number rose to 89% of the time during the PGA II’s first 5 months (P = .03). Type II PGA scores correlated strongly with patient-reported fibromyalgia and depression symptoms, but did not correlate with PGA scores for type I symptoms, such as nephritis and arthritis.

Type II problems are common in lupus. Patients’ joints might be fine, and their kidney disease in remission, but they can still feel miserable, and will often blame it on a lupus flare. Physicians who disagree end up at odds with their patients, Dr. Rogers explained.

“We decided to rethink how we address these patients, and came up with this new type I, type II categorization.” Now, when paints complain of brain fog, for example, “I say ‘yes, this is your lupus. I believe you,’ but we don’t need to give you more steroids or very expensive immunosuppressives for this. What you need to do is take your Cymbalta, work on your exercise, and maybe see your therapist,” she said.

It validates what people are going through, and builds trust. “Patients like it; they feel heard, and I walk out of the room, and I feel better,” she said.

During its first 5 months, 197 patients had PGAs for type II symptoms, along with type I PGAs. The average age of the patients was 46 years, and 92% were women.

Patients with predominately type II symptoms were more likely than were those with predominately type I disease to be depressed (84% versus 39%), and they reported higher lupus activity, greater symptom severity, and more severe fibromyalgia. The differences were statistically significant.

Type II treatments included medications in 60% of cases, exercise or physical therapy in almost 60% of cases, sleep studies or help with sleep hygiene in about 35%, and psychiatric or psychological referral in almost 20%. Less than 5% of patients were referred to a pain clinic.

There was no external funding for the study, and Dr. Rogers didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Rogers J et al. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6[suppl 1]: Abstract 102. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2019-lsm.102

AT LUPUS 2019

Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Perineural Involvement in Nevus Sebaceus

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

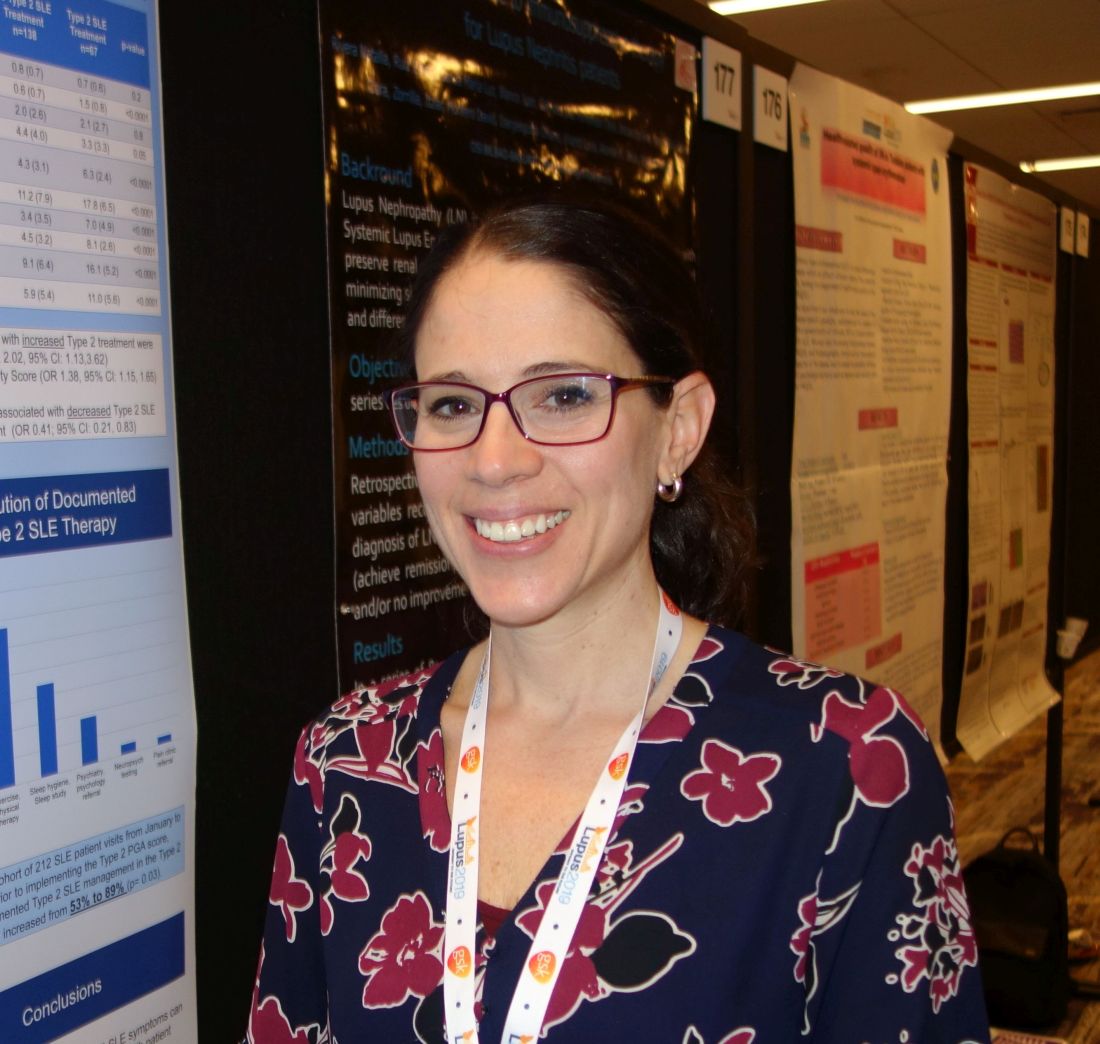

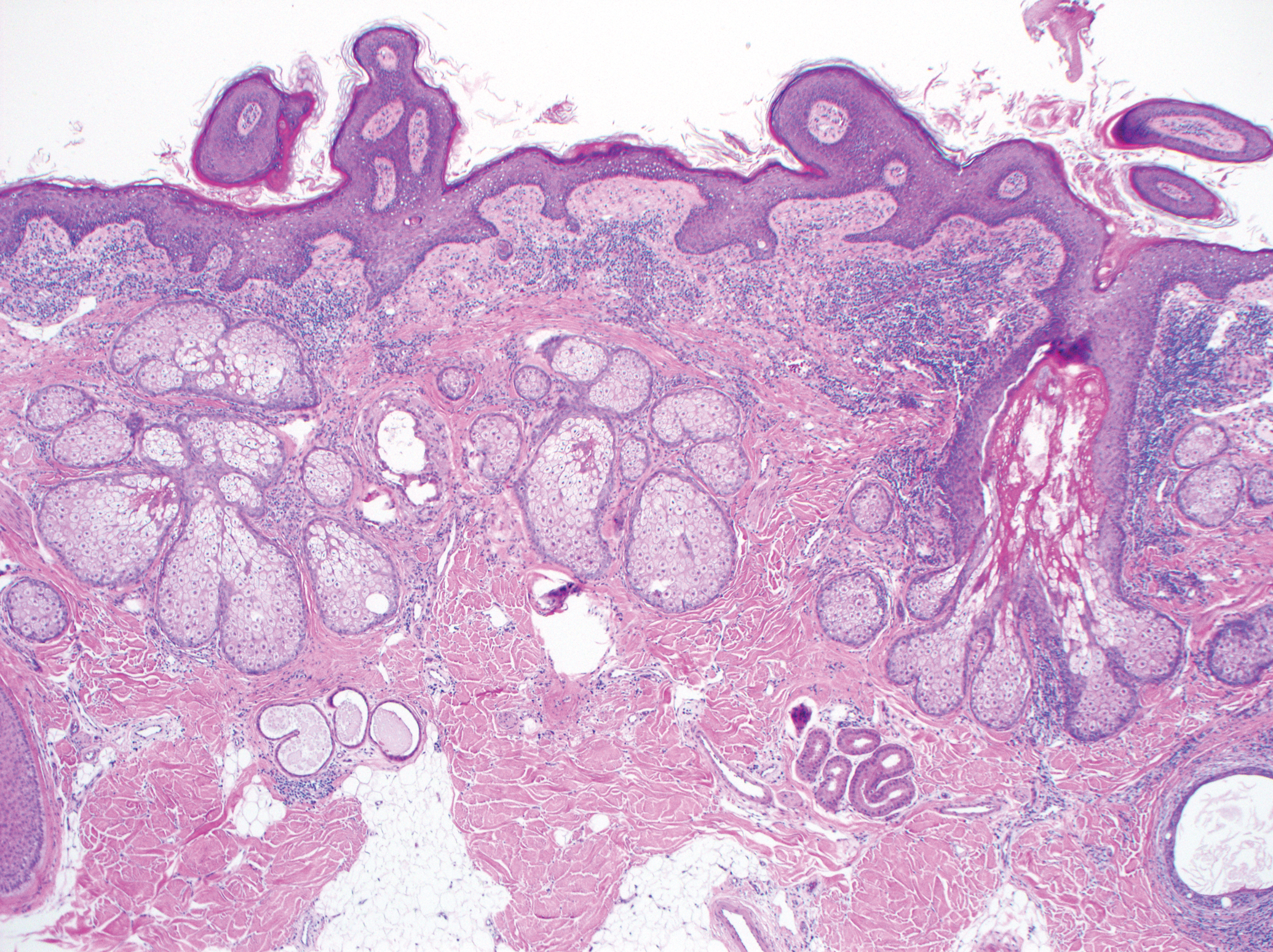

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

Practice Points

- Nevus sebaceus (NS) is frequently found on the scalp and may increase in size during puberty.

- Commonly found additional neoplasms within NS include trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Malignancies are possible but rare.

Donate Auction Items for Gala

The ‘Vascular Spectacular’ Gala has officially sold out, but it’s not too late to donate auction items for the live and silent auctions. So far donations consist of vacation stays, tickets to sporting events, entertainment, travel and time shares, chef and other classes, sports memorabilia, wine tastings and much more. All are welcome to participate as bidders in the silent auction. Get the full details here.

The ‘Vascular Spectacular’ Gala has officially sold out, but it’s not too late to donate auction items for the live and silent auctions. So far donations consist of vacation stays, tickets to sporting events, entertainment, travel and time shares, chef and other classes, sports memorabilia, wine tastings and much more. All are welcome to participate as bidders in the silent auction. Get the full details here.

The ‘Vascular Spectacular’ Gala has officially sold out, but it’s not too late to donate auction items for the live and silent auctions. So far donations consist of vacation stays, tickets to sporting events, entertainment, travel and time shares, chef and other classes, sports memorabilia, wine tastings and much more. All are welcome to participate as bidders in the silent auction. Get the full details here.

Programming for PAs Slated

The SVS will once again host an afternoon of education programming specifically for physician assistants. The afternoon session will be from 1 to 5 p.m. Thursday, June 13. Topics include discussions of PAs in different team settings, vascular diagnostics, venous disease and wound management, and dialysis access. Attendees can also earn additional credits. VAM is designated for 30 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. Register for VAM today.

The SVS will once again host an afternoon of education programming specifically for physician assistants. The afternoon session will be from 1 to 5 p.m. Thursday, June 13. Topics include discussions of PAs in different team settings, vascular diagnostics, venous disease and wound management, and dialysis access. Attendees can also earn additional credits. VAM is designated for 30 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. Register for VAM today.

The SVS will once again host an afternoon of education programming specifically for physician assistants. The afternoon session will be from 1 to 5 p.m. Thursday, June 13. Topics include discussions of PAs in different team settings, vascular diagnostics, venous disease and wound management, and dialysis access. Attendees can also earn additional credits. VAM is designated for 30 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. Register for VAM today.

Register for VAM by Tomorrow for a Chance to Win

The Society for Vascular Surgery will provide complimentary meeting registration to a lucky attendee. To be eligible, all you must do is register for the meeting before 5 p.m. CDT tomorrow, April 24. The winner will be selected at random. This year’s meeting will be June 12 to 15 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington D.C. Read more about the VAM contest, and more, in the latest SVS VAMail.

The Society for Vascular Surgery will provide complimentary meeting registration to a lucky attendee. To be eligible, all you must do is register for the meeting before 5 p.m. CDT tomorrow, April 24. The winner will be selected at random. This year’s meeting will be June 12 to 15 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington D.C. Read more about the VAM contest, and more, in the latest SVS VAMail.

The Society for Vascular Surgery will provide complimentary meeting registration to a lucky attendee. To be eligible, all you must do is register for the meeting before 5 p.m. CDT tomorrow, April 24. The winner will be selected at random. This year’s meeting will be June 12 to 15 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington D.C. Read more about the VAM contest, and more, in the latest SVS VAMail.

Losing a patient to suicide

Join us Wednesday, April 24, 2019, at 6:00 p.m. Eastern/5:00 p.m. Central as we open a lively Twitter discussion in psychiatry on the topic of losing a patient to suicide. Our special guests include physicians with expertise on the topic of patient suicide, Dinah Miller, MD, (@shrinkrapdinah) and Eric Plakun, MD, (@EricPlakunMD). We hope you join us April 24 at 6 p.m. ET. #MDedgeChats.

Suicides in the United States are on the rise; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide was the cause of death of almost 45,000 people in 2016. Overall, it was the 10th leading cause of death, and the second leading cause of death among people aged 10-34 years. Twice as many people completed suicide as were victims of homicides.

Losing a patient to suicide is one of the most difficult and painful experiences a psychiatrist will face. In addition to concern for the patient and his or her family, psychiatrists may experience thoughts of responsibility and what they could have done differently to prevent the suicide. Although often trained in helping patients address grief, psychiatrists may not be as comfortable processing their own grief after the loss of a patient to suicide.

Topics of conversation

Q1: Have you ever lost a patient to suicide?

Q2: How do you think the loss of your patient changed your approach to psychiatry?

Q3: How did the loss change you?

Q4: If you did not discuss the suicide with your colleagues, what held you back?

Q5: How can you support medical professionals who lose patients to suicide?

Resources

Preventing suicide: What should clinicians do differently?

Individualized intervention key to reducing suicide attempts

Helping survivors in the aftermath of suicide loss

The blinding lies of depression

Suicide symposium: A multidisciplinary approach to risk assessment and the emotional aftermath of patient suicide

About Dr. Miller

Dr. Miller is the author of numerous books and articles, including “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), which she wrote with Dr. Annette Hanson (@clinkshrink), and “When a Patient Dies by Suicide – The Physician’s Silent Sorrow” in the New England Journal of Medicine (@NEJM) (2019;380:311-13). She has a private practice in Baltimore and is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University (@HopkinsMedicine).

About Dr. Plakun

Dr. Plakun is the medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center (@Austen Riggs), a “top 10” U.S. News and World Report “Best Hospital” in psychiatry based in Stockbridge, Mass. He also serves on the board of trustees of the American Psychiatric Association (@APA Psychiatric) representing New England and Eastern Canada, and was the founding leader of the APA Psychotherapy Caucus. Dr. Plakun is a board-certified psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, former member of the Harvard Medical School clinical faculty, and author of more than 50 publications.

Are you new to Twitter chats? We have included simple steps below to help you join and participate in the conversation.

Join us Wednesday, April 24, 2019, at 6:00 p.m. Eastern/5:00 p.m. Central as we open a lively Twitter discussion in psychiatry on the topic of losing a patient to suicide. Our special guests include physicians with expertise on the topic of patient suicide, Dinah Miller, MD, (@shrinkrapdinah) and Eric Plakun, MD, (@EricPlakunMD). We hope you join us April 24 at 6 p.m. ET. #MDedgeChats.

Suicides in the United States are on the rise; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide was the cause of death of almost 45,000 people in 2016. Overall, it was the 10th leading cause of death, and the second leading cause of death among people aged 10-34 years. Twice as many people completed suicide as were victims of homicides.

Losing a patient to suicide is one of the most difficult and painful experiences a psychiatrist will face. In addition to concern for the patient and his or her family, psychiatrists may experience thoughts of responsibility and what they could have done differently to prevent the suicide. Although often trained in helping patients address grief, psychiatrists may not be as comfortable processing their own grief after the loss of a patient to suicide.

Topics of conversation

Q1: Have you ever lost a patient to suicide?

Q2: How do you think the loss of your patient changed your approach to psychiatry?

Q3: How did the loss change you?

Q4: If you did not discuss the suicide with your colleagues, what held you back?

Q5: How can you support medical professionals who lose patients to suicide?

Resources

Preventing suicide: What should clinicians do differently?

Individualized intervention key to reducing suicide attempts

Helping survivors in the aftermath of suicide loss

The blinding lies of depression

Suicide symposium: A multidisciplinary approach to risk assessment and the emotional aftermath of patient suicide

About Dr. Miller

Dr. Miller is the author of numerous books and articles, including “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), which she wrote with Dr. Annette Hanson (@clinkshrink), and “When a Patient Dies by Suicide – The Physician’s Silent Sorrow” in the New England Journal of Medicine (@NEJM) (2019;380:311-13). She has a private practice in Baltimore and is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University (@HopkinsMedicine).

About Dr. Plakun

Dr. Plakun is the medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center (@Austen Riggs), a “top 10” U.S. News and World Report “Best Hospital” in psychiatry based in Stockbridge, Mass. He also serves on the board of trustees of the American Psychiatric Association (@APA Psychiatric) representing New England and Eastern Canada, and was the founding leader of the APA Psychotherapy Caucus. Dr. Plakun is a board-certified psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, former member of the Harvard Medical School clinical faculty, and author of more than 50 publications.

Are you new to Twitter chats? We have included simple steps below to help you join and participate in the conversation.

Join us Wednesday, April 24, 2019, at 6:00 p.m. Eastern/5:00 p.m. Central as we open a lively Twitter discussion in psychiatry on the topic of losing a patient to suicide. Our special guests include physicians with expertise on the topic of patient suicide, Dinah Miller, MD, (@shrinkrapdinah) and Eric Plakun, MD, (@EricPlakunMD). We hope you join us April 24 at 6 p.m. ET. #MDedgeChats.

Suicides in the United States are on the rise; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide was the cause of death of almost 45,000 people in 2016. Overall, it was the 10th leading cause of death, and the second leading cause of death among people aged 10-34 years. Twice as many people completed suicide as were victims of homicides.

Losing a patient to suicide is one of the most difficult and painful experiences a psychiatrist will face. In addition to concern for the patient and his or her family, psychiatrists may experience thoughts of responsibility and what they could have done differently to prevent the suicide. Although often trained in helping patients address grief, psychiatrists may not be as comfortable processing their own grief after the loss of a patient to suicide.

Topics of conversation

Q1: Have you ever lost a patient to suicide?

Q2: How do you think the loss of your patient changed your approach to psychiatry?

Q3: How did the loss change you?

Q4: If you did not discuss the suicide with your colleagues, what held you back?

Q5: How can you support medical professionals who lose patients to suicide?

Resources

Preventing suicide: What should clinicians do differently?

Individualized intervention key to reducing suicide attempts

Helping survivors in the aftermath of suicide loss

The blinding lies of depression

Suicide symposium: A multidisciplinary approach to risk assessment and the emotional aftermath of patient suicide

About Dr. Miller

Dr. Miller is the author of numerous books and articles, including “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), which she wrote with Dr. Annette Hanson (@clinkshrink), and “When a Patient Dies by Suicide – The Physician’s Silent Sorrow” in the New England Journal of Medicine (@NEJM) (2019;380:311-13). She has a private practice in Baltimore and is affiliated with Johns Hopkins University (@HopkinsMedicine).

About Dr. Plakun

Dr. Plakun is the medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center (@Austen Riggs), a “top 10” U.S. News and World Report “Best Hospital” in psychiatry based in Stockbridge, Mass. He also serves on the board of trustees of the American Psychiatric Association (@APA Psychiatric) representing New England and Eastern Canada, and was the founding leader of the APA Psychotherapy Caucus. Dr. Plakun is a board-certified psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, former member of the Harvard Medical School clinical faculty, and author of more than 50 publications.

Are you new to Twitter chats? We have included simple steps below to help you join and participate in the conversation.

Referral system aims to slash axial spondyloarthritis diagnostic delay

Low back pain. A bane of human existence.

Almost everyone – 90% of us in fact – will have at least one bout of it. Snow shoveling, too much weight on the barbell, a strange twist while carrying in the groceries. A quick visit to a primary care doc, a prescription NSAID, a few days or weeks of rest, and a gradual resolution of symptoms is the usual course.

But in Toronto, a small group of clinicians aims to change this clinical picture. They’ve developed a secondary screening program to identify back pain patients at risk of axSpA, potentially bypassing the diagnostic merry-go-round, years of pain, and disease progression. Success relies on the alertness of primary care and the expertise of advanced practice physical therapists to make sure the right patients arrive in the rheumatologist’s office.

“We know the delay is on average 8-10 years, and often by the time a patient does show up in a rheumatology office, much damage has occurred,” Laura Passalent, a clinician researcher at University Health Network, Toronto, said in an interview. “But spondyloarthritis gets lost in the background noise of mechanical and musculoskeletal back pain, so it’s hard for primary care to accurately diagnose, and patients often bounce around the health care system for years before someone finally suspects. We are trying to change that paradigm, reduce the time to diagnosis, and identify patients earlier. If we can, we can treat earlier, and the evidence suggests that, like early treatment in RA, we can prevent disease progression.”

As in rheumatoid arthritis, getting patients on biologics sooner rather than later improves radiologic outcomes, daily function, and quality of life. Studies bear that out, including one by Ms. Passalent’s rheumatologist colleagues, Robert Inman, MD, and Nigel Haroon, MD, PhD, also with UHN. Their study of 334 patients with ankylosing spondylitis found that early treatment with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor reduced the odds of disease progression by up to 50% and was especially effective in those who got early treatment (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Oct;65[10]:2645-54). Those who started at least 10 years after symptom onset were twice as likely to progress. Those who were on biologics for more than 50% of their disease duration were three times less likely to progress.

“It’s known that biologics improve the signs and symptoms of SpA, and the great majority of patients feel better on them,” Dr. Inman said in an interview. “But the really important outcomes are preventing structural damage, a finding already well established in RA. This study changed our thoughts on altering the natural history of this disease.”

Diagnostic delays worsen long-term outcomes in axSpA, just as in RA, but unlike RA, axSpA has no stepwise diagnostic algorithm, Dr. Inman said. “We had a real problem identifying a simple, reliable pathway for referrals. One of the strategies we investigated was this screening clinic model to facilitate appropriate and early referrals that are no longer dependent on primary care physicians.”

Community back pain clinics

Raja Rampersaud, MD, a spine surgeon at UHN, developed the first model – a community clinic that triages and treats people with low back pain. Primary care providers refer into the clinics, and advanced practice clinicians work with patients to create care plans. These might include low-level medical therapy, exercise, and other self-management techniques.

Ms. Passalent and her team partnered with these clinics in a pilot project to identify axSpA patients. The team provided clinician education and referral criteria for patients. These include back pain of more than 3 months’ duration in patients younger than 50 years who have other signs of inflammatory back pain. Primary care providers can refer such patients to a secondary screening program, run by an advanced care clinician, that further refines the diagnosis.

The clinic work-up includes the following:

- History, involving a description of back pain, peripheral joint involvement, and extra-articular manifestations.

- Physical exam looking at spinal mobility and vital signs, as well as tender/swollen joints, enthesitis, and dactylitis.

- Investigations that include pelvis and lateral lumbar and cervical spine radiographs, HLA-B27 testing, and measurements of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.