User login

Inadequate glycemic control in type 1 diabetes leads to increased fracture risk

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

FROM DIABETIC MEDICINE

Migrant children need safety net

ACEs tied to traumas threaten the emotional, physical health of a generation

An 11-year-old was caring for his toddler brother. Both were fending for themselves in a cell with dozens of other children. The little one was quiet with matted hair, a hacking cough, muddy pants, and eyes that fluttered with fatigue.

As the two brothers were reportedly interviewed, one fell asleep on two office chairs drawn together, probably the most comfortable bed he had used in weeks. They had been separated from an 18-year-old uncle and sent to the Clint Border Patrol Station in Texas. When they were interviewed in the news report, they had been there 3 weeks and counting.

Per news reports this summer, preteen migrant children have been asked to care for toddlers not related to them with no assistance from adults, and no beds, no food, and no change of clothing. Children were sleeping on concrete floors and eating the same unpalatable and unhealthy foods for close to a month: instant oatmeal, instant soup, and previously frozen burritos. Babies were roaming around in dirty diapers, fending for themselves, foraging for food. Two- and 3-year-old toddlers were sick with no adult comforting them.

When some people visited the border patrol station, they said they saw children trapped in cages like animals. Some were keening in pain while pining for their parents from whom they had been separated.

These children were forcibly separated from parents. In addition, they face living conditions that include hunger, dehydration, and lack of hygiene, to name a few. This sounds like some fantastical nightmare from a war-torn third-world country – but no these circumstances are real, and they are here in the USA.

We witness helplessly the helplessness created by a man-made disaster striking the world’s most vulnerable creature: the human child. This specter afflicting thousands of migrant children either seeking asylum or an immigrant status has far-reaching implications. This is even more ironic, given that, as a nation, we have embraced the concept of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their impact on lifelong health challenges. Most of us reel with horror as these tales make their way to national headlines. But are we as a nation complicit in watching like bystanders while a generation of children is placed at risk from experiencing the long-term effects of ACEs on their physical and emotional health?

Surely if the psychological implications of ACEs do not warrant a change in course, the mere economics of the costs arising from the suffering caused by totally preventable medical problems in adulthood should be considered in policy decisions. However, that is beyond the scope of this commentary.

The human child is so utterly dependent on parents. He does not have the fairly quick physical independence from parents that we see in the animal kingdom. As soon as a child is born, a curious process of attachment begins within the mom and baby dyad, and eventually, this bond engulfs the father as well. The baby depends on the parent to understand his needs: be it when to eat, when he wants to be touched, when he needs to be left alone, when he needs to be cleaned or fed. Optimum crying serves so many purposes, and most parents are exquisitely attuned to the baby’s cry. From this relationship emerges a stable worldview, and, among many things, a stable neuroendocrine system.

Unique cultural backgrounds of individuals create the scaffolding for human variability, which in turn, confers a richness to the human race. However, development proceeds in a fairly uniform and universal fashion for children, regardless of where they come from. The progression of brain and body development moves lockstep with each other responding to a complex interplay between genetics, environment, and neurohormonal factors. It is remarkable just how resilient the human baby is in the face of the challenges that it often faces: accidental injury, illness, and even benign neglect.

However, there comes a breaking point similar to that described in the stories above, where the stress is toxic and intolerable. It is continuous, and it is relentless in its capacity to bathe the developing brain and body of the child with noxious endogenous substances that cause cell death and subsequent atrophy that is potentially irreversible.

We see such children in our clinics downstream: at ages 8, 13, or 16, after they have lost their ability to modulate emotions and are highly aggressive, or are withdrawn and depressed – or in the juvenile justice system after having repeatedly but impulsively violated the law. In other words, repeated trauma changes the wiring of the brain and neuromodulatory capacity. There is literature suggesting that traumatized children carry within them modified genes that affect their capacity to be nurturing parents. In other words, trauma has the potential to lead to multigenerational transmission of the experiences of suffering and often a psychological incapacity to parent – putting subsequent generations at risk.

So what should we do? Be bystanders, or become involved professionals?

The need to create a supportive safety net for these children is essential. Ideally, they should be reunited with their parents. The reunification of children with their parents is an absolute must if it can be done. Their parents are alive somewhere – and the best mitigators of the emotional damage already done. A strong case needs to be made for reunification, otherwise parental separation, deprivation on multiple levels, such as what these children are experiencing, will create a generation of compromised children.

A second-best option is that an emotional and physical safety net should be created that mimics a family for each child. Children need predictability and stability of caregivers with whom they can form an affective bond. This is essential for them to negotiate the cycle of inconsolable weeping, searching for their parent/s, reconciling the loss, and either reaching a level of adaptation or being engulfed in the despair that these toddlers, children, and teens continually face. In addition, these individuals/teams first and foremost should plan on giving equal consideration to the physical and emotional needs of the children.

The damage is done in the form of subjecting children to all that is detrimental to development. Now, steady, regular presence of shift workers who understand the importance of the continuity of relationships and who cannot only advocate for but also provide for the nutritional, sleep, and hygiene needs of the child concurrently is necessary. The children need soft and nurturing touch, predictability of routines, adequate sleep, adequate wholesome nutrition, and familiarity of faces who should make a commitment of spending no less than 6 to 9 months at a stretch in these camps.

Although the task appears herculean, drastic problems need drastic remedies, as the entire life of every child is at stake. These workers should be trained in mental health and physical health first aid, so they can recognize the gradations of despair, detachment, and acting out in children and know how to triage the children to appropriate trained mental health and medical clinicians. It is to be expected that both medical and mental health problems will be concentrated in this population, and planning for staffing such camps should anticipate that. This safety net should be created in all facilities accepting these children.

Dr. Sood is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, and senior professor of child mental health policy at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

ACEs tied to traumas threaten the emotional, physical health of a generation

ACEs tied to traumas threaten the emotional, physical health of a generation

An 11-year-old was caring for his toddler brother. Both were fending for themselves in a cell with dozens of other children. The little one was quiet with matted hair, a hacking cough, muddy pants, and eyes that fluttered with fatigue.

As the two brothers were reportedly interviewed, one fell asleep on two office chairs drawn together, probably the most comfortable bed he had used in weeks. They had been separated from an 18-year-old uncle and sent to the Clint Border Patrol Station in Texas. When they were interviewed in the news report, they had been there 3 weeks and counting.

Per news reports this summer, preteen migrant children have been asked to care for toddlers not related to them with no assistance from adults, and no beds, no food, and no change of clothing. Children were sleeping on concrete floors and eating the same unpalatable and unhealthy foods for close to a month: instant oatmeal, instant soup, and previously frozen burritos. Babies were roaming around in dirty diapers, fending for themselves, foraging for food. Two- and 3-year-old toddlers were sick with no adult comforting them.

When some people visited the border patrol station, they said they saw children trapped in cages like animals. Some were keening in pain while pining for their parents from whom they had been separated.

These children were forcibly separated from parents. In addition, they face living conditions that include hunger, dehydration, and lack of hygiene, to name a few. This sounds like some fantastical nightmare from a war-torn third-world country – but no these circumstances are real, and they are here in the USA.

We witness helplessly the helplessness created by a man-made disaster striking the world’s most vulnerable creature: the human child. This specter afflicting thousands of migrant children either seeking asylum or an immigrant status has far-reaching implications. This is even more ironic, given that, as a nation, we have embraced the concept of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their impact on lifelong health challenges. Most of us reel with horror as these tales make their way to national headlines. But are we as a nation complicit in watching like bystanders while a generation of children is placed at risk from experiencing the long-term effects of ACEs on their physical and emotional health?

Surely if the psychological implications of ACEs do not warrant a change in course, the mere economics of the costs arising from the suffering caused by totally preventable medical problems in adulthood should be considered in policy decisions. However, that is beyond the scope of this commentary.

The human child is so utterly dependent on parents. He does not have the fairly quick physical independence from parents that we see in the animal kingdom. As soon as a child is born, a curious process of attachment begins within the mom and baby dyad, and eventually, this bond engulfs the father as well. The baby depends on the parent to understand his needs: be it when to eat, when he wants to be touched, when he needs to be left alone, when he needs to be cleaned or fed. Optimum crying serves so many purposes, and most parents are exquisitely attuned to the baby’s cry. From this relationship emerges a stable worldview, and, among many things, a stable neuroendocrine system.

Unique cultural backgrounds of individuals create the scaffolding for human variability, which in turn, confers a richness to the human race. However, development proceeds in a fairly uniform and universal fashion for children, regardless of where they come from. The progression of brain and body development moves lockstep with each other responding to a complex interplay between genetics, environment, and neurohormonal factors. It is remarkable just how resilient the human baby is in the face of the challenges that it often faces: accidental injury, illness, and even benign neglect.

However, there comes a breaking point similar to that described in the stories above, where the stress is toxic and intolerable. It is continuous, and it is relentless in its capacity to bathe the developing brain and body of the child with noxious endogenous substances that cause cell death and subsequent atrophy that is potentially irreversible.

We see such children in our clinics downstream: at ages 8, 13, or 16, after they have lost their ability to modulate emotions and are highly aggressive, or are withdrawn and depressed – or in the juvenile justice system after having repeatedly but impulsively violated the law. In other words, repeated trauma changes the wiring of the brain and neuromodulatory capacity. There is literature suggesting that traumatized children carry within them modified genes that affect their capacity to be nurturing parents. In other words, trauma has the potential to lead to multigenerational transmission of the experiences of suffering and often a psychological incapacity to parent – putting subsequent generations at risk.

So what should we do? Be bystanders, or become involved professionals?

The need to create a supportive safety net for these children is essential. Ideally, they should be reunited with their parents. The reunification of children with their parents is an absolute must if it can be done. Their parents are alive somewhere – and the best mitigators of the emotional damage already done. A strong case needs to be made for reunification, otherwise parental separation, deprivation on multiple levels, such as what these children are experiencing, will create a generation of compromised children.

A second-best option is that an emotional and physical safety net should be created that mimics a family for each child. Children need predictability and stability of caregivers with whom they can form an affective bond. This is essential for them to negotiate the cycle of inconsolable weeping, searching for their parent/s, reconciling the loss, and either reaching a level of adaptation or being engulfed in the despair that these toddlers, children, and teens continually face. In addition, these individuals/teams first and foremost should plan on giving equal consideration to the physical and emotional needs of the children.

The damage is done in the form of subjecting children to all that is detrimental to development. Now, steady, regular presence of shift workers who understand the importance of the continuity of relationships and who cannot only advocate for but also provide for the nutritional, sleep, and hygiene needs of the child concurrently is necessary. The children need soft and nurturing touch, predictability of routines, adequate sleep, adequate wholesome nutrition, and familiarity of faces who should make a commitment of spending no less than 6 to 9 months at a stretch in these camps.

Although the task appears herculean, drastic problems need drastic remedies, as the entire life of every child is at stake. These workers should be trained in mental health and physical health first aid, so they can recognize the gradations of despair, detachment, and acting out in children and know how to triage the children to appropriate trained mental health and medical clinicians. It is to be expected that both medical and mental health problems will be concentrated in this population, and planning for staffing such camps should anticipate that. This safety net should be created in all facilities accepting these children.

Dr. Sood is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, and senior professor of child mental health policy at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

An 11-year-old was caring for his toddler brother. Both were fending for themselves in a cell with dozens of other children. The little one was quiet with matted hair, a hacking cough, muddy pants, and eyes that fluttered with fatigue.

As the two brothers were reportedly interviewed, one fell asleep on two office chairs drawn together, probably the most comfortable bed he had used in weeks. They had been separated from an 18-year-old uncle and sent to the Clint Border Patrol Station in Texas. When they were interviewed in the news report, they had been there 3 weeks and counting.

Per news reports this summer, preteen migrant children have been asked to care for toddlers not related to them with no assistance from adults, and no beds, no food, and no change of clothing. Children were sleeping on concrete floors and eating the same unpalatable and unhealthy foods for close to a month: instant oatmeal, instant soup, and previously frozen burritos. Babies were roaming around in dirty diapers, fending for themselves, foraging for food. Two- and 3-year-old toddlers were sick with no adult comforting them.

When some people visited the border patrol station, they said they saw children trapped in cages like animals. Some were keening in pain while pining for their parents from whom they had been separated.

These children were forcibly separated from parents. In addition, they face living conditions that include hunger, dehydration, and lack of hygiene, to name a few. This sounds like some fantastical nightmare from a war-torn third-world country – but no these circumstances are real, and they are here in the USA.

We witness helplessly the helplessness created by a man-made disaster striking the world’s most vulnerable creature: the human child. This specter afflicting thousands of migrant children either seeking asylum or an immigrant status has far-reaching implications. This is even more ironic, given that, as a nation, we have embraced the concept of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their impact on lifelong health challenges. Most of us reel with horror as these tales make their way to national headlines. But are we as a nation complicit in watching like bystanders while a generation of children is placed at risk from experiencing the long-term effects of ACEs on their physical and emotional health?

Surely if the psychological implications of ACEs do not warrant a change in course, the mere economics of the costs arising from the suffering caused by totally preventable medical problems in adulthood should be considered in policy decisions. However, that is beyond the scope of this commentary.

The human child is so utterly dependent on parents. He does not have the fairly quick physical independence from parents that we see in the animal kingdom. As soon as a child is born, a curious process of attachment begins within the mom and baby dyad, and eventually, this bond engulfs the father as well. The baby depends on the parent to understand his needs: be it when to eat, when he wants to be touched, when he needs to be left alone, when he needs to be cleaned or fed. Optimum crying serves so many purposes, and most parents are exquisitely attuned to the baby’s cry. From this relationship emerges a stable worldview, and, among many things, a stable neuroendocrine system.

Unique cultural backgrounds of individuals create the scaffolding for human variability, which in turn, confers a richness to the human race. However, development proceeds in a fairly uniform and universal fashion for children, regardless of where they come from. The progression of brain and body development moves lockstep with each other responding to a complex interplay between genetics, environment, and neurohormonal factors. It is remarkable just how resilient the human baby is in the face of the challenges that it often faces: accidental injury, illness, and even benign neglect.

However, there comes a breaking point similar to that described in the stories above, where the stress is toxic and intolerable. It is continuous, and it is relentless in its capacity to bathe the developing brain and body of the child with noxious endogenous substances that cause cell death and subsequent atrophy that is potentially irreversible.

We see such children in our clinics downstream: at ages 8, 13, or 16, after they have lost their ability to modulate emotions and are highly aggressive, or are withdrawn and depressed – or in the juvenile justice system after having repeatedly but impulsively violated the law. In other words, repeated trauma changes the wiring of the brain and neuromodulatory capacity. There is literature suggesting that traumatized children carry within them modified genes that affect their capacity to be nurturing parents. In other words, trauma has the potential to lead to multigenerational transmission of the experiences of suffering and often a psychological incapacity to parent – putting subsequent generations at risk.

So what should we do? Be bystanders, or become involved professionals?

The need to create a supportive safety net for these children is essential. Ideally, they should be reunited with their parents. The reunification of children with their parents is an absolute must if it can be done. Their parents are alive somewhere – and the best mitigators of the emotional damage already done. A strong case needs to be made for reunification, otherwise parental separation, deprivation on multiple levels, such as what these children are experiencing, will create a generation of compromised children.

A second-best option is that an emotional and physical safety net should be created that mimics a family for each child. Children need predictability and stability of caregivers with whom they can form an affective bond. This is essential for them to negotiate the cycle of inconsolable weeping, searching for their parent/s, reconciling the loss, and either reaching a level of adaptation or being engulfed in the despair that these toddlers, children, and teens continually face. In addition, these individuals/teams first and foremost should plan on giving equal consideration to the physical and emotional needs of the children.

The damage is done in the form of subjecting children to all that is detrimental to development. Now, steady, regular presence of shift workers who understand the importance of the continuity of relationships and who cannot only advocate for but also provide for the nutritional, sleep, and hygiene needs of the child concurrently is necessary. The children need soft and nurturing touch, predictability of routines, adequate sleep, adequate wholesome nutrition, and familiarity of faces who should make a commitment of spending no less than 6 to 9 months at a stretch in these camps.

Although the task appears herculean, drastic problems need drastic remedies, as the entire life of every child is at stake. These workers should be trained in mental health and physical health first aid, so they can recognize the gradations of despair, detachment, and acting out in children and know how to triage the children to appropriate trained mental health and medical clinicians. It is to be expected that both medical and mental health problems will be concentrated in this population, and planning for staffing such camps should anticipate that. This safety net should be created in all facilities accepting these children.

Dr. Sood is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, and senior professor of child mental health policy at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

Sexual Dysfunction in MS

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

A 37-year-old woman presents to her primary care clinic with a chief complaint of depression. She was diagnosed with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29 and is currently taking an injectable preventive therapy. Over the past 6 months, she has had increased marital strain secondary to losing her job because “I couldn’t mentally keep up with the work anymore.” This has caused financial difficulties for her family. In addition, she tires easily and has been napping in the afternoon. She and her husband are experiencing intimacy difficulties, and she confirms problems with vaginal dryness and a general loss of her sexual drive.

Sexual dysfunction in MS is common, affecting 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men with MS. It is an “invisible” symptom, similar to fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and pain.1-3

There are three ways that MS patients can be affected by sexual dysfunction, and they are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sexual dysfunction results from demyelination/axonal destruction of the central nervous system, which potentially leads to altered genital sensation or paresthesia. Secondary sexual dysfunction stems from nonsexual MS symptoms, such as fatigue, spasticity, tremor, impairments in concentration/attention, and iatrogenic causes (eg, adverse effects of medication). Tertiary sexual dysfunction involves the psychosocial/cultural aspects of the disease that can impact a patient’s sexual drive.

SYMPTOMS

Like many other symptoms associated with MS, the symptoms of sexual dysfunction are highly variable. In women, the most common complaints are fatigue, decrease in genital sensation (27%-47%), decrease in libido (31%-74%) and vaginal lubrication (36%-48%), and difficulty with orgasm.4 In men with MS, in addition to erectile problems, surveys have identified decreased genital sensation, fatigue (75%), difficulty with ejaculation (18%-50%), decreased interest or arousal (39%), and anorgasmia (37%) as fairly common complaints.2

TREATMENT

Managing sexual dysfunction in a patient with MS is dependent on the underlying problem. Some examples include

- For many patients, their disease causes significant anxiety and worry about current and potentially future disability—which can make intimacy more difficult. Sometimes, referral to a mental health professional may be required to help the patient

with individual and/or couples counseling to further elucidate underlying intimacy issues. - For patients experiencing MS-associated fatigue, suggest planning for sexual activity in the morning, since fatigue is known to worsen throughout the day.

- For those who qualify for antidepressant medications, remember that some (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can further decrease libido and therefore should be avoided if possible.

- For women who have difficulty with lubrication, a nonpetroleum-based lubricant may reduce vaginal dryness, while use of a vibrator may assist with genital stimulation.

- For men who cannot maintain erection, phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs (eg, sildenafil) can be helpful; other options include alprostadil urethral suppositories and intracavernous injections.

The patient is screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire, which yields a score of 17 (moderately severe). You discuss the need for active treatment with her, and she agrees to start an antidepressant medication. Bupropion is chosen, given its effectiveness and lack of adverse effects (including sexual dysfunction). The patient also is encouraged to use nonpetroleum-based lubricants. Finally, a referral is made for couples counseling, and a 6-week follow-up appointment is scheduled.

CONCLUSION

Sexual dysfunction in MS is quite common in both women and men, and the related symptoms are often multifactorial. Strategies to address sexual dysfunction in MS require a tailored approach. Fortunately, any treatments for sexual dysfunction initiated by the patient’s primary care provider will not have an adverse effect on the patient’s outcome with MS. For more complicated cases of MS-associated sexual dysfunction, urology referral is recommended.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

1. Foley FW, Sander A. Sexuality, multiple sclerosis and women. Mult Scler Manage. 1997;4:1-9.

2. Calabro RS, De Luca R, Conti-Nibali V, et al. Sexual dysfunction in male patients with multiple sclerosis: a need for counseling! Int J Neurosci. 2014;124(8):547-557.

3. Gava G, Visconti M, Salvi F, et al. Prevalence and psychopathological determinants of sexual dysfunction and related distress in women with and without multiple sclerosis. J Sex Med. 2019;16(6):833-842.

4. Cordeau D, Courtois, F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57(5):337-47.

The ABCs of COCs: A Guide for Dermatology Residents on Combined Oral Contraceptives

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

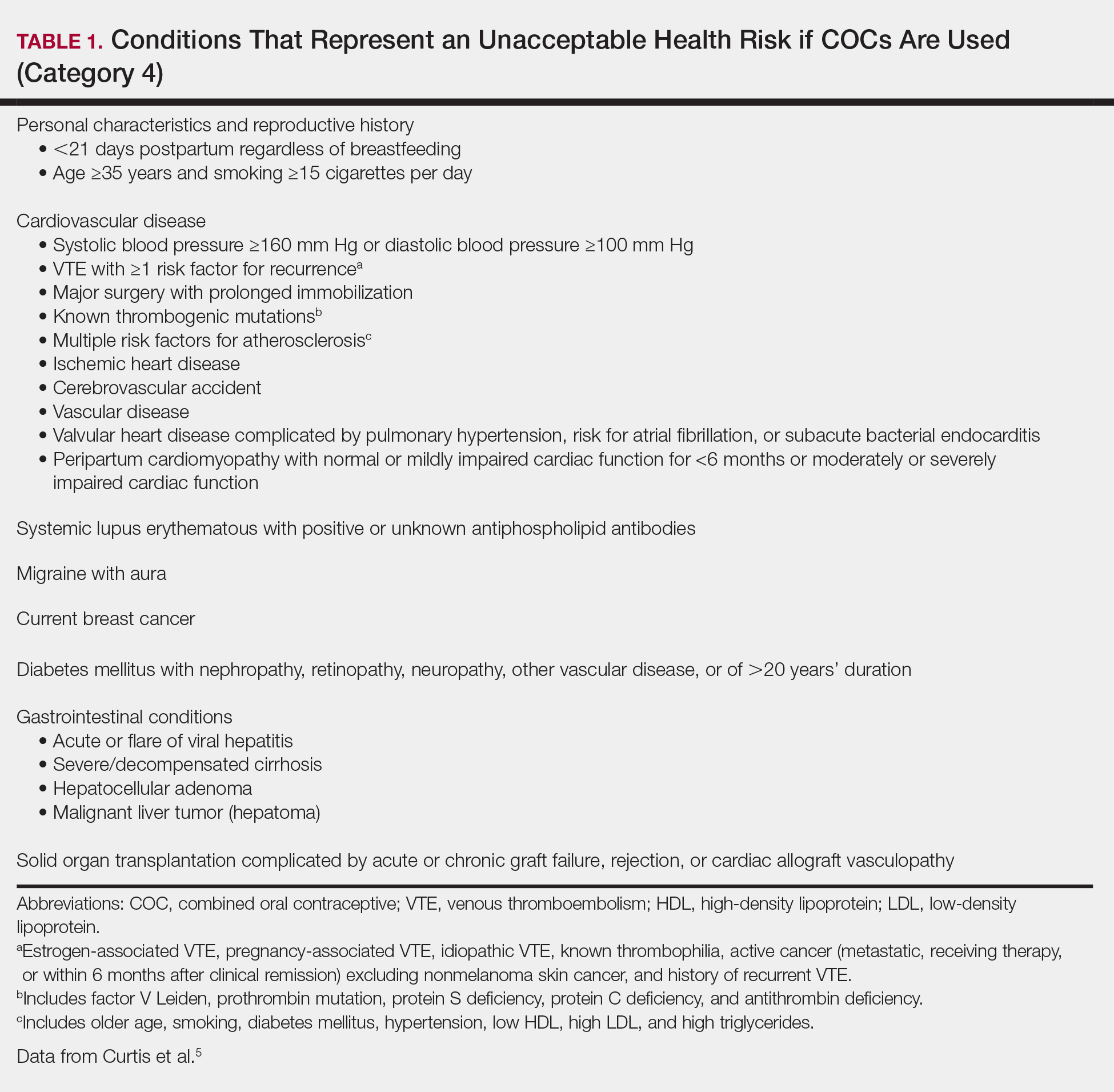

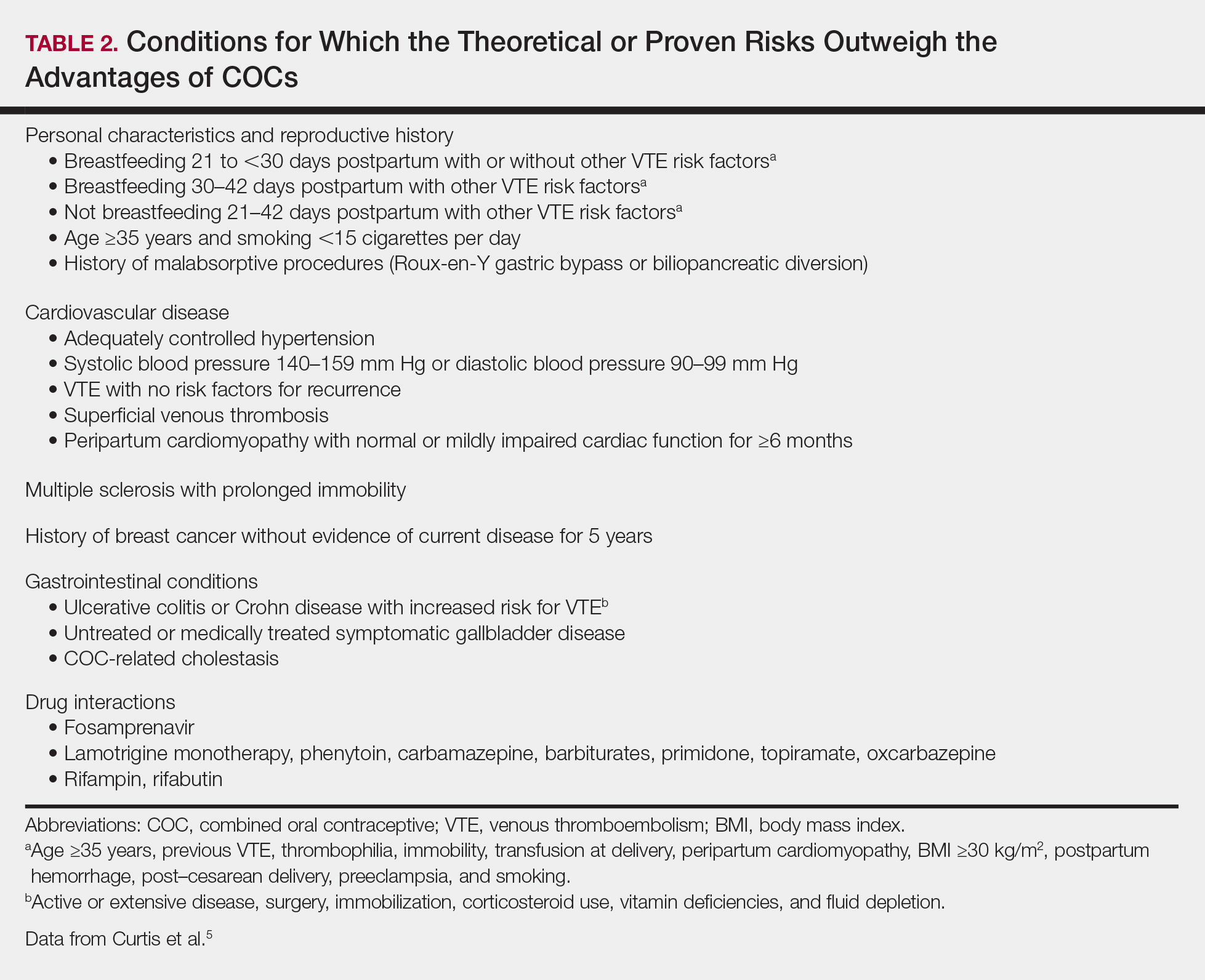

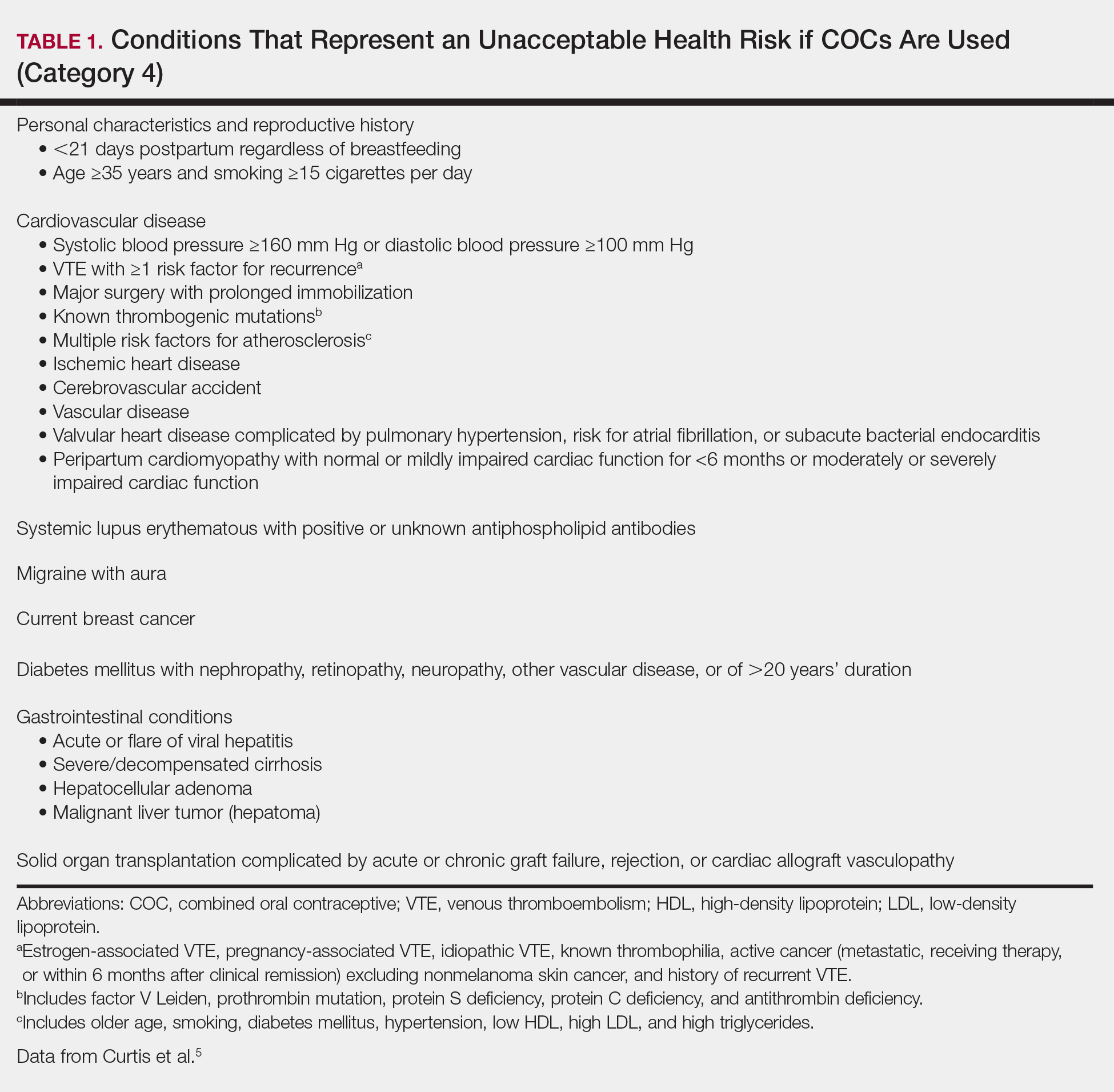

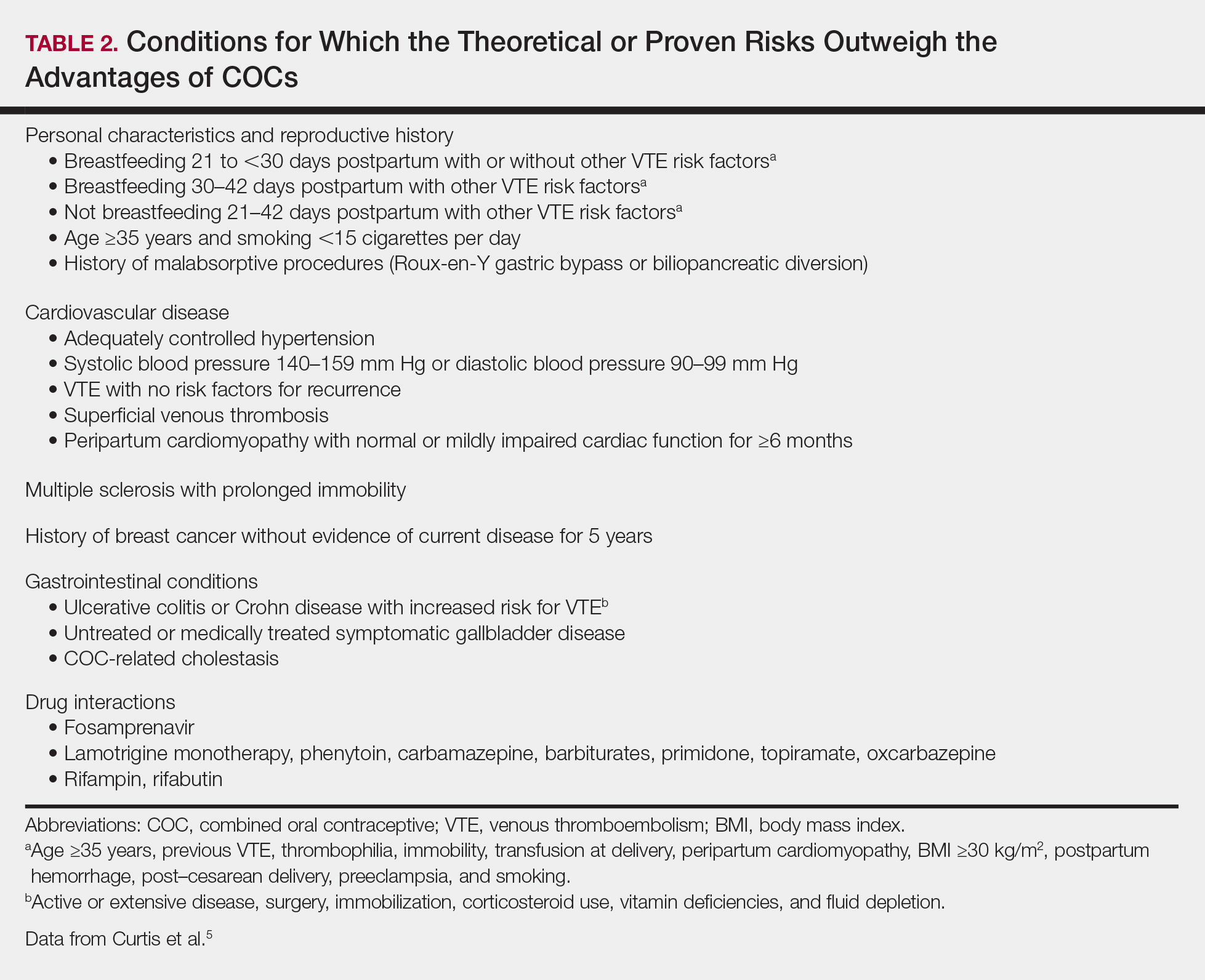

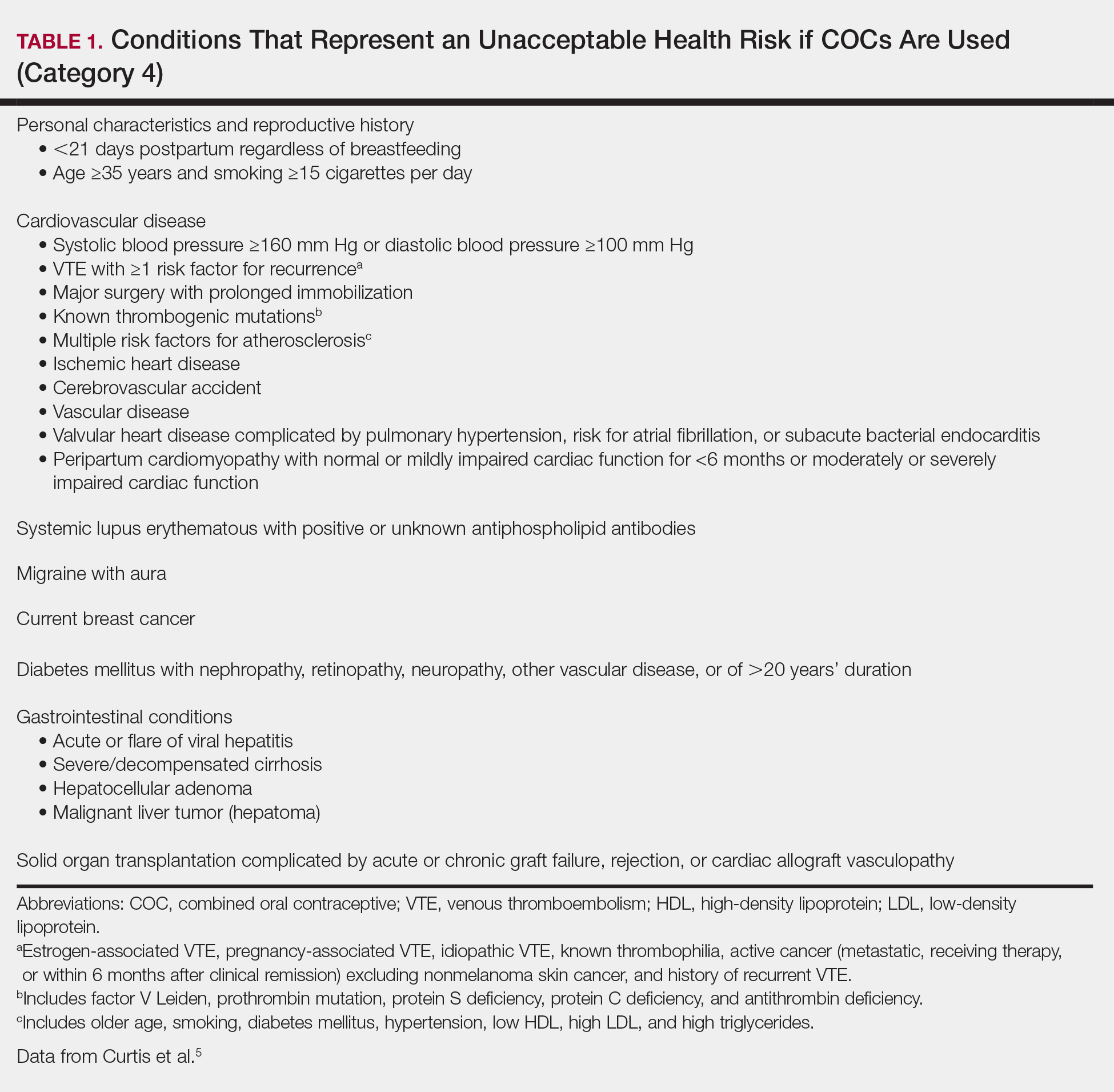

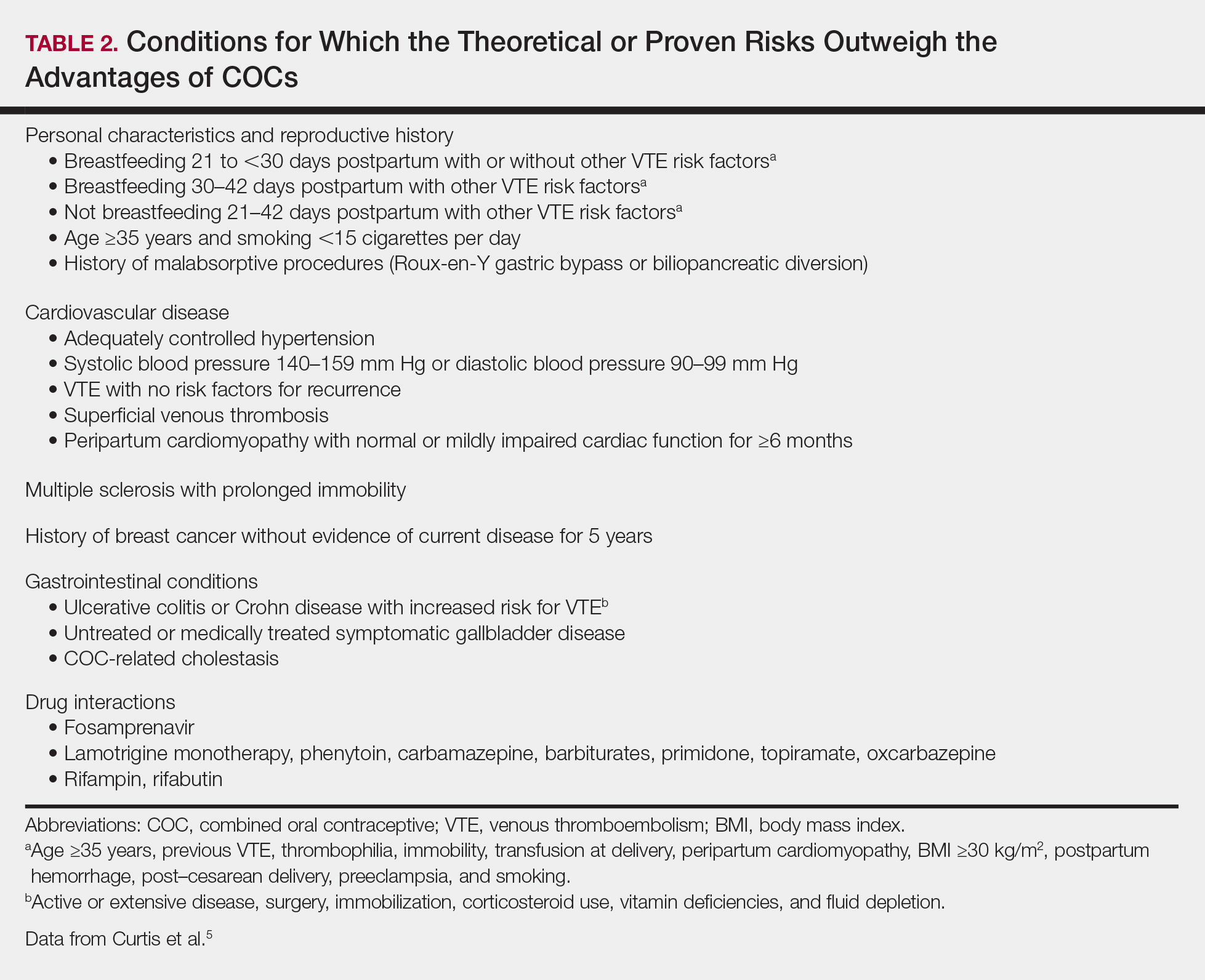

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e933.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Fitzpatrick L, Mauer E, Chen CL. Oral contraceptives for acne treatment: US dermatologists’ knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices. Cutis. 2017;99:195-201.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003553.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:6-11.

- McKinney K. Understanding the options: a guide to oral contraceptives. https://www.cecentral.com/assets/2097/022%20Oral%20Contraceptives%2010-26-09.pdf. Published November 5, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 microg versus >20 microg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- Terki F, Malhotra U. Medical and Service Delivery Guidelines for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. London, United Kingdom: International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2004.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- Pastor Z, Holla K, Chmel R. The influence of combined oral contraceptives on female sexual desire: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:27-43.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Birth control pills for acne: tips from Julie Harper at the Summer AAD. Cutis. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/144550/acne/birth-control-pills-acne-tips-julie-harper-summer-aad. Published August 14, 2017. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:31-34.

- Roach RE, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD011054.

- Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international multicentre case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1997;349:1202-1209.

- Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drugs. JAMA. 1967;199:601-605.

- Boukari F, Jourdan E, Fontas E, et al. Prevention of melasma relapses with sunscreen combining protection against UV and short wavelengths of visible light: a prospective randomized comparative trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:189-190.e181.

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e933.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Fitzpatrick L, Mauer E, Chen CL. Oral contraceptives for acne treatment: US dermatologists’ knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices. Cutis. 2017;99:195-201.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003553.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:6-11.