User login

How Do Drug Shortages Affect Dermatologists?

The frequency of drug shortages in the United States has considerably increased over the last decade, affecting different areas of health care practice.1,2 Basic products needed to care for patients in hospitals and clinics are many of the same drugs that are in short supply.3 This issue has become an ongoing public health concern that directly affects health care providers and their patients.4 In dermatology, similar to other specialties, success often is influenced by the efficacy of medications used to treat patients, and lack of appropriate medications has the potential to diminish health outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative for dermatology providers to recognize the factors that contribute to this issue, understand the effects of drug shortages on patients, and learn how they can improve stewardship of scarce resources and contribute to the solution.

Causes of Drug Shortages

Drug shortages can occur due to discontinuations, delays, or manufacturing and quality problems.5 Shortages of the most basic hospital products represent market failure.1 In such cases, a small number of manufacturers supply these products, and if a manufacturer discontinues a particular product—as in the case of lidocaine with epinephrine—a shortage results, as the current system does not have the capacity to deal with such as issue.1,6

An important playmaker affecting the market for medical supplies and drugs are group purchasing organizations (GPOs). The 4 largest GPOs in the United States account for 90% of the medical supply market.7 Although they have simplified the process for hospitals to purchase supplies by taking on the work and expense of dealing with hundreds of manufacturers, GPOs have considerable power to affect the supply chain. By allowing certain manufacturers to become the sole suppliers of products in return for premium fees, GPOs have narrowed the supply chain of key products to sometimes only 1 or 2 manufacturers.7 This practice may lead to decreased capacity of regional and national supply chains, setting up the system to eventual product shortage in scenarios of production problems or a decrease in the already limited number of manufacturers.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) works closely with manufacturers to prevent or reduce the impact of drug shortages. Although the FDA recently has taken more action to address the issue, solutions such as allowing imported products and underlying or approving new suppliers are only temporary fixes.1 The root of the problem needs to be dealt with by ensuring there is a broad competitive supply chain.

Impact on Dermatologists

The nationwide shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine that occurred in 2017 is a specific example of how drug shortages affect dermatologists.6 This product is used in the typical dermatology clinic on a daily basis for biopsies. Possible solutions to decrease usage include drawing up 1.5 mL lidocaine with epinephrine instead of 3 mL and mixing readily available normal saline with lidocaine to produce a 1:200,000 mixture to yield a 0.5% concentration that still maintains good vasoconstrictor effects. Options for dermatologists who run out of lidocaine with epinephrine are to either use lidocaine without epinephrine, which disrupts optimal patient care, or to purchase 1% lidocaine with epinephrine at a much higher cost.6 A study that analyzed changes in drug pricing following shortages in the United States indicated that prices of drugs facing a shortage increased more than twice as quickly as expected between 2015 and 2016 vs those that were not in shortage, which may reflect opportunistic behaviors of drug manufacturers during shortages.8

The American Academy of Dermatology Association has created a letter and encouraged patients to notify their lawmakers about the severity of the drug shortage issue. Given the shortage of local anesthetics and their importance to the practice of dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology Association also has created guidelines discussing local anesthetics that could be an alternative to lidocaine for office-based dermatologic surgery.9

Final Thoughts

Dermatology practitioners should be aware of current shortages impacting their practice and address the potential shortage proactively. We propose that dermatology clinics should keep an emergency reservoir of products routinely used in practice that currently are on the FDA drug shortage list, particularly lidocaine hydrochloride (with and without epinephrine) and sodium bicarbonate,10 which may diminish the negative impact a shortage may have on the high quality of health care we strive to provide. On a bigger scale, providers should be more proactive to have their voices heard and get involved with policymaking given the potential for patient harm and suboptimal care associated with drug shortages.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER, Zocchi MS, et al. Longitudinal trends in US shortages of sterile solutions, 2001-17. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1903-1908.

- Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: a complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:361-373.

- Drug shortages roundtable: minimizing impact on patient care [published online March 15, 2018]. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:816-820.

- Fox ER, McLaughlin MM. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1742-1750.

- Bowles SK. Drug shortages: more than just a background noise [published online February 28, 2018]. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019;72:3-4.

- Bodie B, Brodell RT, Helms SE. Shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine: causes and solutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:392-393.

- Bruhn WE, Fracica EA, Makary MA. Group purchasing organizations, health care costs, and drug shortages. JAMA. 2018;320:1859-1860.

- Hernandez I, Sampathkumar S, Good CB, et al. Changes in drug pricing after drug shortages in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170:74-76.

- AADA, other specialties continue pressing FDA on drug shortages American Academy of Dermatology Association website.

https://www.aad.org/advocacy/news/news/2018/02/aada-other-specialties-continue-pressing-fda-on-drug-shortages. Published February 23, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019. - FDA drug shortages. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.aad.org/advocacy/drug-pricing-and-availability/dermatologic-drug-shortages. Accessed July 24, 2019.

The frequency of drug shortages in the United States has considerably increased over the last decade, affecting different areas of health care practice.1,2 Basic products needed to care for patients in hospitals and clinics are many of the same drugs that are in short supply.3 This issue has become an ongoing public health concern that directly affects health care providers and their patients.4 In dermatology, similar to other specialties, success often is influenced by the efficacy of medications used to treat patients, and lack of appropriate medications has the potential to diminish health outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative for dermatology providers to recognize the factors that contribute to this issue, understand the effects of drug shortages on patients, and learn how they can improve stewardship of scarce resources and contribute to the solution.

Causes of Drug Shortages

Drug shortages can occur due to discontinuations, delays, or manufacturing and quality problems.5 Shortages of the most basic hospital products represent market failure.1 In such cases, a small number of manufacturers supply these products, and if a manufacturer discontinues a particular product—as in the case of lidocaine with epinephrine—a shortage results, as the current system does not have the capacity to deal with such as issue.1,6

An important playmaker affecting the market for medical supplies and drugs are group purchasing organizations (GPOs). The 4 largest GPOs in the United States account for 90% of the medical supply market.7 Although they have simplified the process for hospitals to purchase supplies by taking on the work and expense of dealing with hundreds of manufacturers, GPOs have considerable power to affect the supply chain. By allowing certain manufacturers to become the sole suppliers of products in return for premium fees, GPOs have narrowed the supply chain of key products to sometimes only 1 or 2 manufacturers.7 This practice may lead to decreased capacity of regional and national supply chains, setting up the system to eventual product shortage in scenarios of production problems or a decrease in the already limited number of manufacturers.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) works closely with manufacturers to prevent or reduce the impact of drug shortages. Although the FDA recently has taken more action to address the issue, solutions such as allowing imported products and underlying or approving new suppliers are only temporary fixes.1 The root of the problem needs to be dealt with by ensuring there is a broad competitive supply chain.

Impact on Dermatologists

The nationwide shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine that occurred in 2017 is a specific example of how drug shortages affect dermatologists.6 This product is used in the typical dermatology clinic on a daily basis for biopsies. Possible solutions to decrease usage include drawing up 1.5 mL lidocaine with epinephrine instead of 3 mL and mixing readily available normal saline with lidocaine to produce a 1:200,000 mixture to yield a 0.5% concentration that still maintains good vasoconstrictor effects. Options for dermatologists who run out of lidocaine with epinephrine are to either use lidocaine without epinephrine, which disrupts optimal patient care, or to purchase 1% lidocaine with epinephrine at a much higher cost.6 A study that analyzed changes in drug pricing following shortages in the United States indicated that prices of drugs facing a shortage increased more than twice as quickly as expected between 2015 and 2016 vs those that were not in shortage, which may reflect opportunistic behaviors of drug manufacturers during shortages.8

The American Academy of Dermatology Association has created a letter and encouraged patients to notify their lawmakers about the severity of the drug shortage issue. Given the shortage of local anesthetics and their importance to the practice of dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology Association also has created guidelines discussing local anesthetics that could be an alternative to lidocaine for office-based dermatologic surgery.9

Final Thoughts

Dermatology practitioners should be aware of current shortages impacting their practice and address the potential shortage proactively. We propose that dermatology clinics should keep an emergency reservoir of products routinely used in practice that currently are on the FDA drug shortage list, particularly lidocaine hydrochloride (with and without epinephrine) and sodium bicarbonate,10 which may diminish the negative impact a shortage may have on the high quality of health care we strive to provide. On a bigger scale, providers should be more proactive to have their voices heard and get involved with policymaking given the potential for patient harm and suboptimal care associated with drug shortages.

The frequency of drug shortages in the United States has considerably increased over the last decade, affecting different areas of health care practice.1,2 Basic products needed to care for patients in hospitals and clinics are many of the same drugs that are in short supply.3 This issue has become an ongoing public health concern that directly affects health care providers and their patients.4 In dermatology, similar to other specialties, success often is influenced by the efficacy of medications used to treat patients, and lack of appropriate medications has the potential to diminish health outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative for dermatology providers to recognize the factors that contribute to this issue, understand the effects of drug shortages on patients, and learn how they can improve stewardship of scarce resources and contribute to the solution.

Causes of Drug Shortages

Drug shortages can occur due to discontinuations, delays, or manufacturing and quality problems.5 Shortages of the most basic hospital products represent market failure.1 In such cases, a small number of manufacturers supply these products, and if a manufacturer discontinues a particular product—as in the case of lidocaine with epinephrine—a shortage results, as the current system does not have the capacity to deal with such as issue.1,6

An important playmaker affecting the market for medical supplies and drugs are group purchasing organizations (GPOs). The 4 largest GPOs in the United States account for 90% of the medical supply market.7 Although they have simplified the process for hospitals to purchase supplies by taking on the work and expense of dealing with hundreds of manufacturers, GPOs have considerable power to affect the supply chain. By allowing certain manufacturers to become the sole suppliers of products in return for premium fees, GPOs have narrowed the supply chain of key products to sometimes only 1 or 2 manufacturers.7 This practice may lead to decreased capacity of regional and national supply chains, setting up the system to eventual product shortage in scenarios of production problems or a decrease in the already limited number of manufacturers.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) works closely with manufacturers to prevent or reduce the impact of drug shortages. Although the FDA recently has taken more action to address the issue, solutions such as allowing imported products and underlying or approving new suppliers are only temporary fixes.1 The root of the problem needs to be dealt with by ensuring there is a broad competitive supply chain.

Impact on Dermatologists

The nationwide shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine that occurred in 2017 is a specific example of how drug shortages affect dermatologists.6 This product is used in the typical dermatology clinic on a daily basis for biopsies. Possible solutions to decrease usage include drawing up 1.5 mL lidocaine with epinephrine instead of 3 mL and mixing readily available normal saline with lidocaine to produce a 1:200,000 mixture to yield a 0.5% concentration that still maintains good vasoconstrictor effects. Options for dermatologists who run out of lidocaine with epinephrine are to either use lidocaine without epinephrine, which disrupts optimal patient care, or to purchase 1% lidocaine with epinephrine at a much higher cost.6 A study that analyzed changes in drug pricing following shortages in the United States indicated that prices of drugs facing a shortage increased more than twice as quickly as expected between 2015 and 2016 vs those that were not in shortage, which may reflect opportunistic behaviors of drug manufacturers during shortages.8

The American Academy of Dermatology Association has created a letter and encouraged patients to notify their lawmakers about the severity of the drug shortage issue. Given the shortage of local anesthetics and their importance to the practice of dermatology, the American Academy of Dermatology Association also has created guidelines discussing local anesthetics that could be an alternative to lidocaine for office-based dermatologic surgery.9

Final Thoughts

Dermatology practitioners should be aware of current shortages impacting their practice and address the potential shortage proactively. We propose that dermatology clinics should keep an emergency reservoir of products routinely used in practice that currently are on the FDA drug shortage list, particularly lidocaine hydrochloride (with and without epinephrine) and sodium bicarbonate,10 which may diminish the negative impact a shortage may have on the high quality of health care we strive to provide. On a bigger scale, providers should be more proactive to have their voices heard and get involved with policymaking given the potential for patient harm and suboptimal care associated with drug shortages.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER, Zocchi MS, et al. Longitudinal trends in US shortages of sterile solutions, 2001-17. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1903-1908.

- Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: a complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:361-373.

- Drug shortages roundtable: minimizing impact on patient care [published online March 15, 2018]. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:816-820.

- Fox ER, McLaughlin MM. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1742-1750.

- Bowles SK. Drug shortages: more than just a background noise [published online February 28, 2018]. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019;72:3-4.

- Bodie B, Brodell RT, Helms SE. Shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine: causes and solutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:392-393.

- Bruhn WE, Fracica EA, Makary MA. Group purchasing organizations, health care costs, and drug shortages. JAMA. 2018;320:1859-1860.

- Hernandez I, Sampathkumar S, Good CB, et al. Changes in drug pricing after drug shortages in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170:74-76.

- AADA, other specialties continue pressing FDA on drug shortages American Academy of Dermatology Association website.

https://www.aad.org/advocacy/news/news/2018/02/aada-other-specialties-continue-pressing-fda-on-drug-shortages. Published February 23, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019. - FDA drug shortages. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.aad.org/advocacy/drug-pricing-and-availability/dermatologic-drug-shortages. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER, Zocchi MS, et al. Longitudinal trends in US shortages of sterile solutions, 2001-17. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1903-1908.

- Fox ER, Sweet BV, Jensen V. Drug shortages: a complex health care crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:361-373.

- Drug shortages roundtable: minimizing impact on patient care [published online March 15, 2018]. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:816-820.

- Fox ER, McLaughlin MM. ASHP guidelines on managing drug product shortages. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1742-1750.

- Bowles SK. Drug shortages: more than just a background noise [published online February 28, 2018]. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019;72:3-4.

- Bodie B, Brodell RT, Helms SE. Shortage of lidocaine with epinephrine: causes and solutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:392-393.

- Bruhn WE, Fracica EA, Makary MA. Group purchasing organizations, health care costs, and drug shortages. JAMA. 2018;320:1859-1860.

- Hernandez I, Sampathkumar S, Good CB, et al. Changes in drug pricing after drug shortages in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170:74-76.

- AADA, other specialties continue pressing FDA on drug shortages American Academy of Dermatology Association website.

https://www.aad.org/advocacy/news/news/2018/02/aada-other-specialties-continue-pressing-fda-on-drug-shortages. Published February 23, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019. - FDA drug shortages. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.aad.org/advocacy/drug-pricing-and-availability/dermatologic-drug-shortages. Accessed July 24, 2019.

Intraoperative Electrosurgical Smoke During Outpatient Surgery: A Survey of Dermatologic Surgeon and Staff Preferences

A growing body of evidence shows that electrosurgical smoke contains both harmful chemicals as well as live material, including blood particles, bacteria, and viruses.1 Both human immunodeficiency virus and human papillomavirus have been identified in surgical smoke plumes, and bacterial colony growth has been demonstrated from electrosurgical smoke specimens, specifically Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria species.2-8 Treating 1 g of tissue with electrocoagulation produces chemical by-products equivalent to burning 6 unfiltered cigarettes,9 which is twice the amount of chemical by-products produced by CO2 laser vaporization of the same quantity of tissue. It is a common misconception that electrosurgical smoke is less hazardous than smoke produced by ablative CO2 procedures.9 Many chemicals are present in electrosurgical smoke plumes, including nitriles, benzenes, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, indoles, phenols, pyridine, pyrrole, styrene, toluene, and xylene.10-12 In animal model studies of rat lungs exposed to surgical smoke, pathologic changes, including interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and emphysema, have been shown in a dose-dependent manner.1,13-16 Diseases and symptoms linked to inhalation of electrosurgical smoke in humans include anemia, eye irritation, hypoxia, dizziness, nasopharyngeal lesions, vomiting, sneezing, throat irritation, and weakness.1,8,17-19 A study of 153 dermatology residents found that more than 70% reported receiving no formal education on the hazards of electrosurgical smoke.20 Approximately 45% were unaware if they had access to smoke evacuation in rooms where electrosurgery was performed. More than 76% were concerned with the infectious risk of electrosurgical smoke, and more than 71% were concerned with its potential carcinogenic risk.20

We surveyed dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

We developed a REDCap survey consisting of 17 questions that was approved by the executive committees of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery for distribution to their dermatologist memberships. It was emailed to eligible participants using their mailing lists. Although the survey was sent directly to member physicians, it was recommended that they forward the survey to their clinical staff to complete.

After responding to an initial set of survey questions, respondents were informed that there is growing evidence of potential harms of inhalation of surgical smoke. They then were asked the same series of survey questions in light of this information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the survey responses was then completed, and free-text responses as a final question of the survey were assessed for themes. Preintervention responses of staff and clinicians noticing smoke and being bothered by smoke were assessed using proportions and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates of the proportions. On most questions, respondents could answer on a scale of 1 to 10. Responses of 5 to 10 on noticing smoke and 5 to 10 on being bothered or troubled by the smoke smell were grouped for analyses. A cross-tabulation using the Bhapkar test for marginal homogeneity was used to assess if information presented on potential smoke hazards changed responses. A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for ordinal responses was used to determine differences between surgeons and staff. A McNemar test was used to determine statistical significance of change in responses to cost. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.

Results

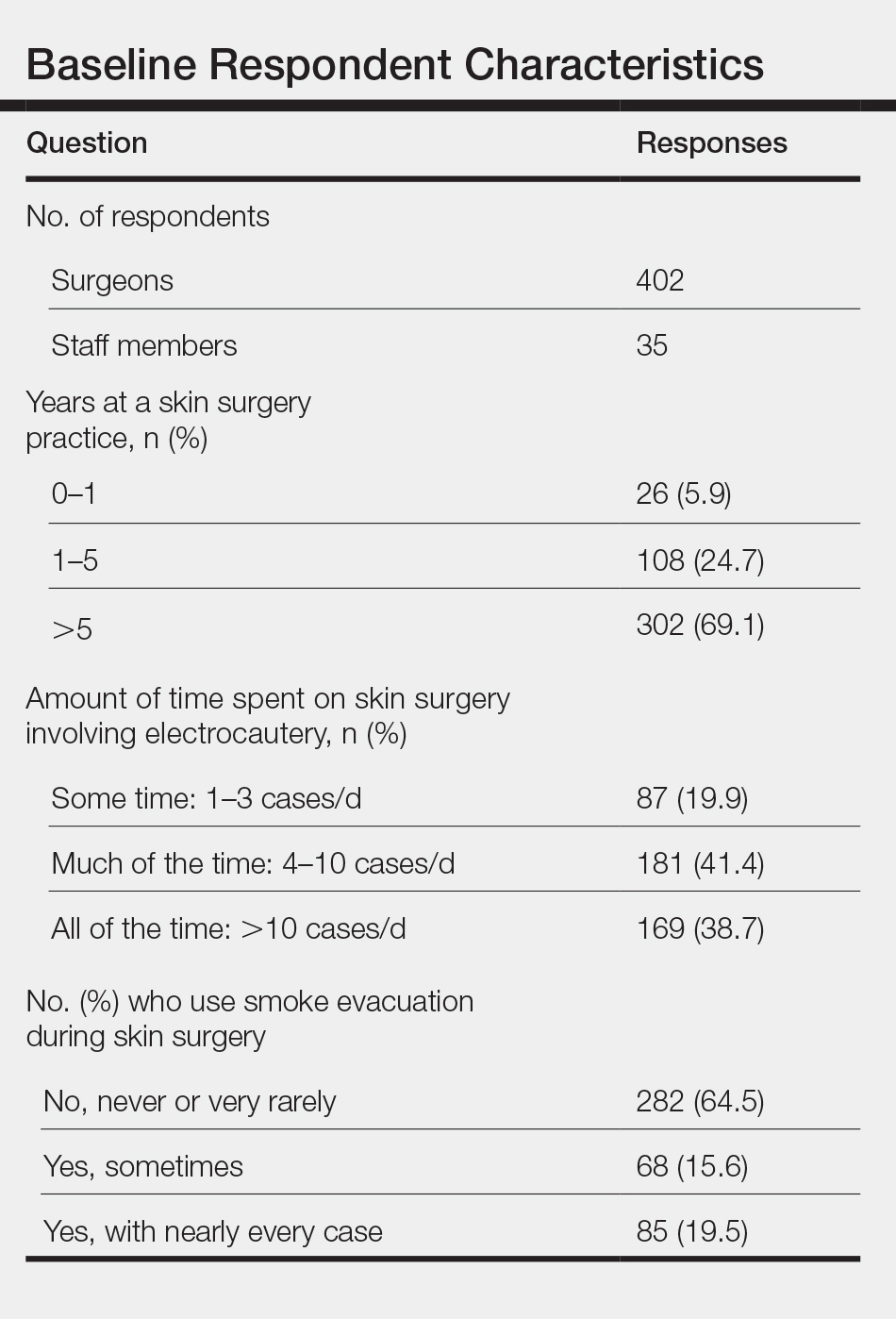

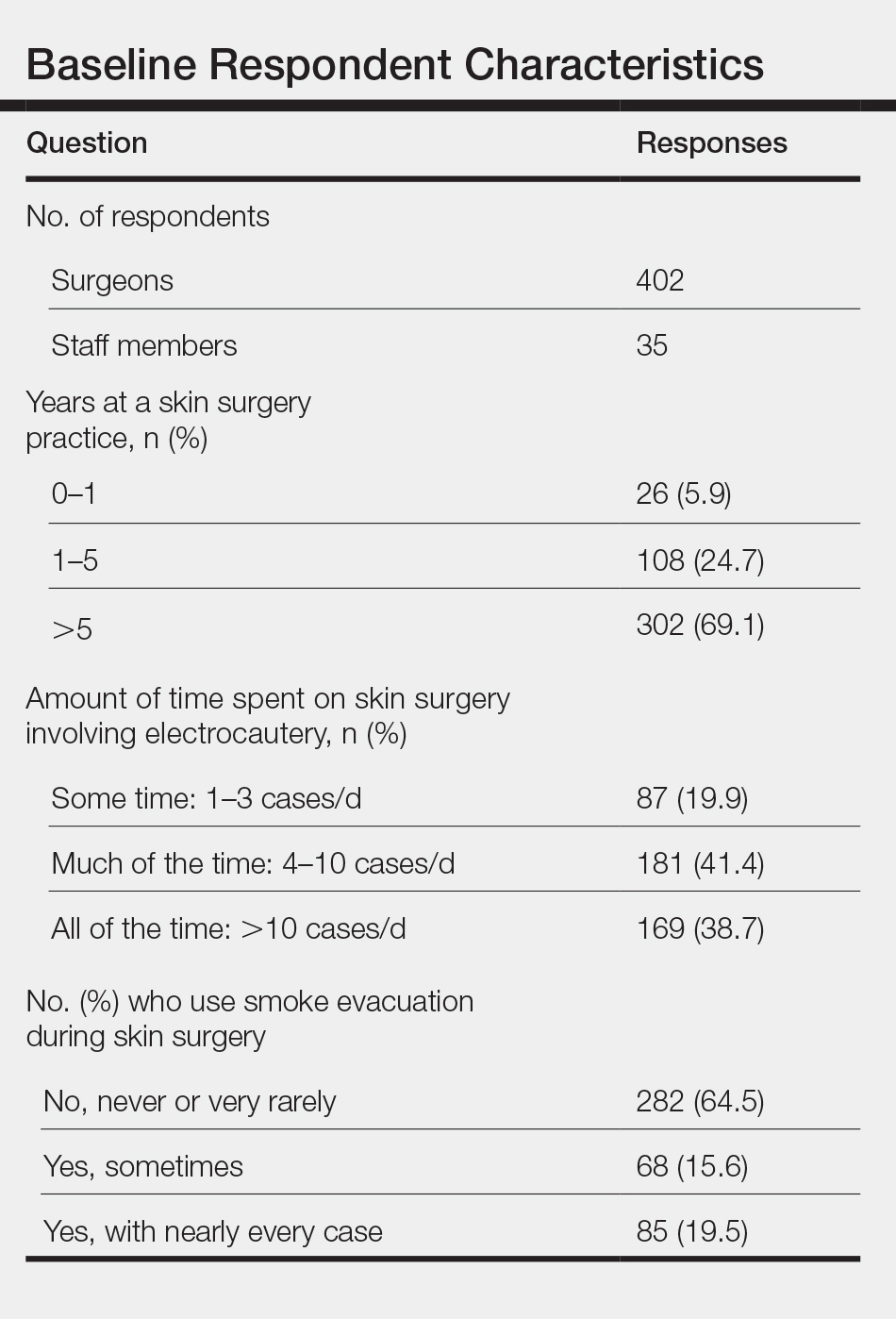

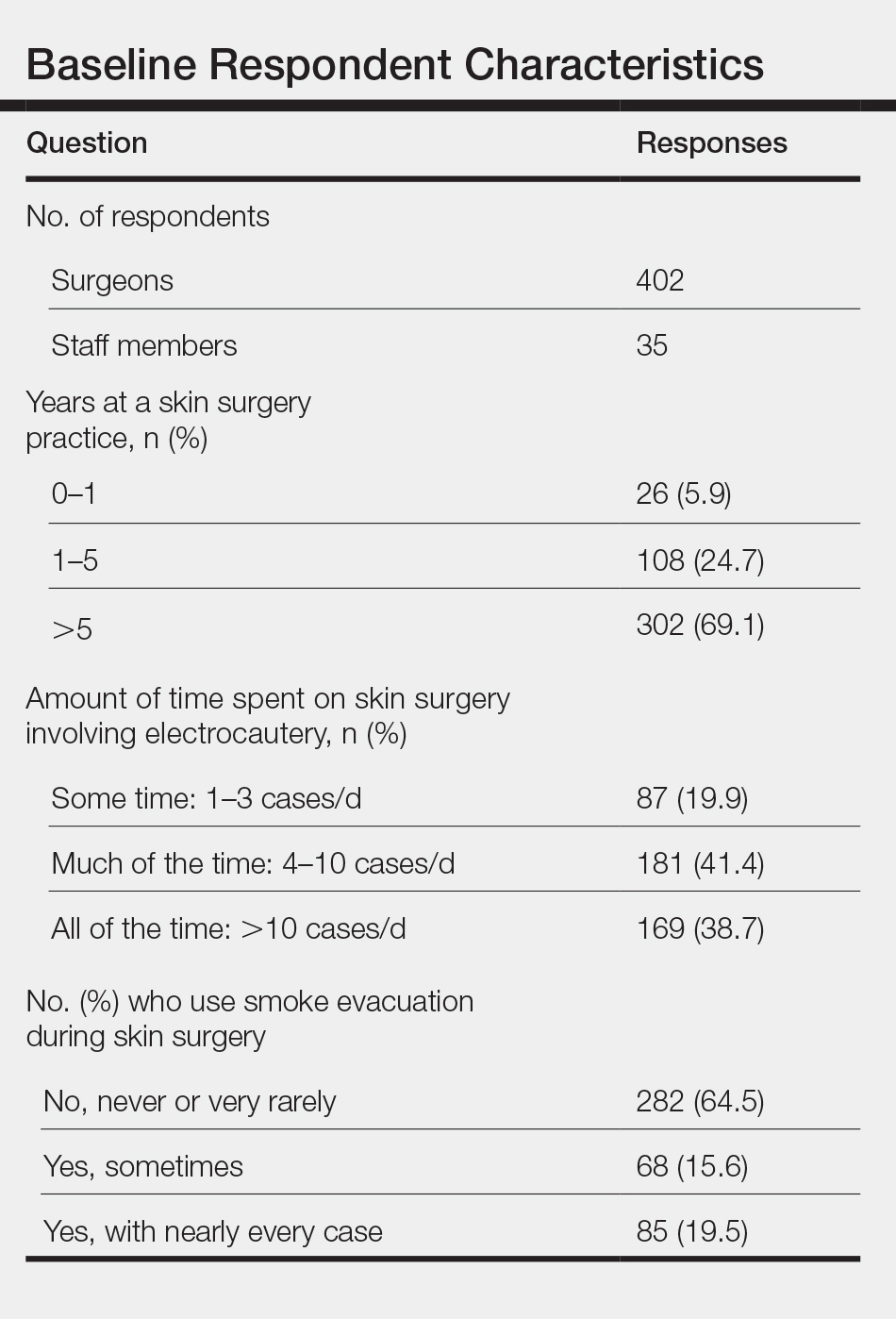

There was a total of 443 responses to our questionnaire. Two respondents answered that they did not work in an office where skin surgery was performed, and 4 respondents did not answer any questions and were therefore excluded, leaving a total of 437 responses (402 physicians and 35 staff members). A summary of the characteristics of the respondents is shown in the Table. Some respondents did not answer each question, leading to fewer than 437 answers for some questions.

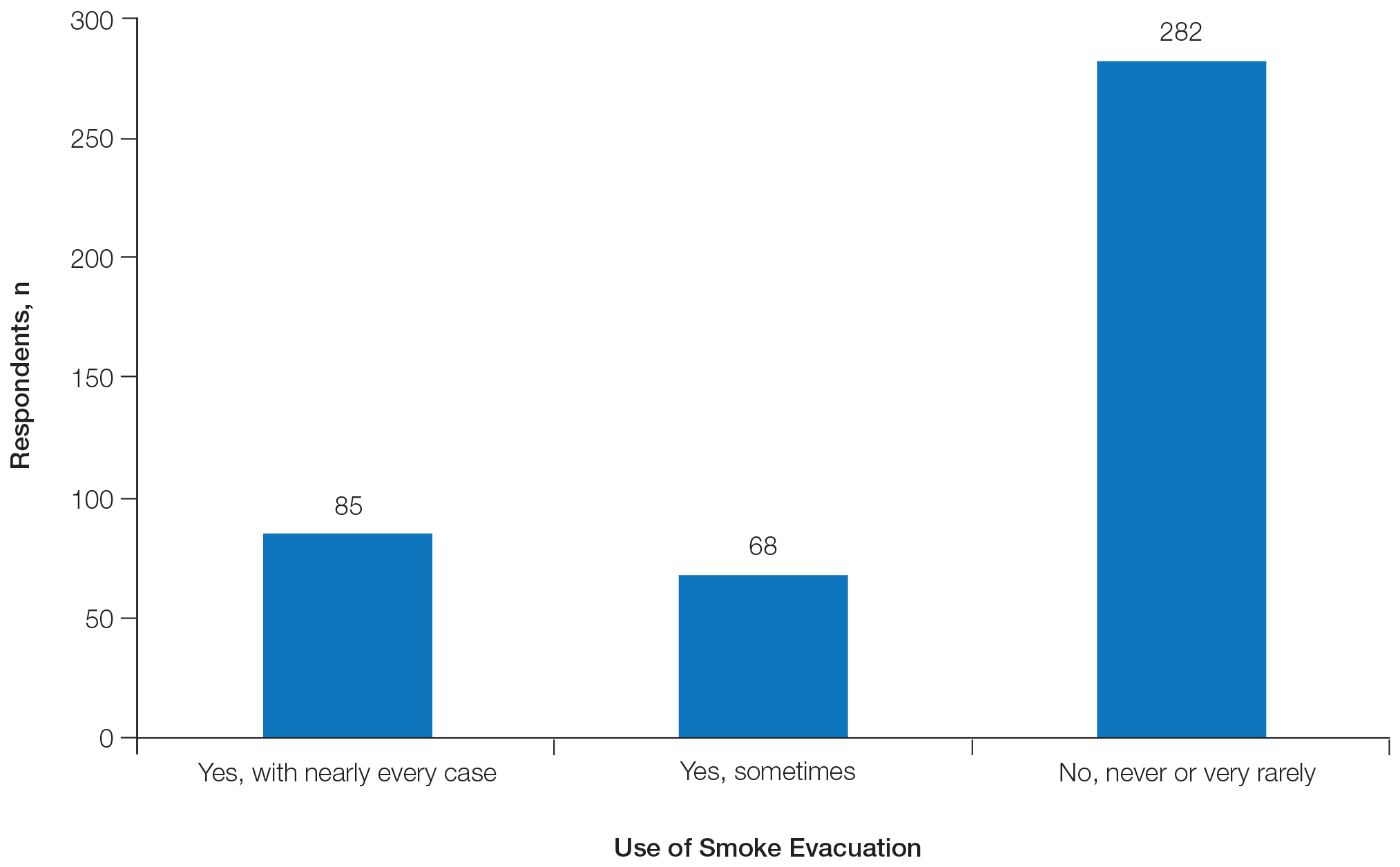

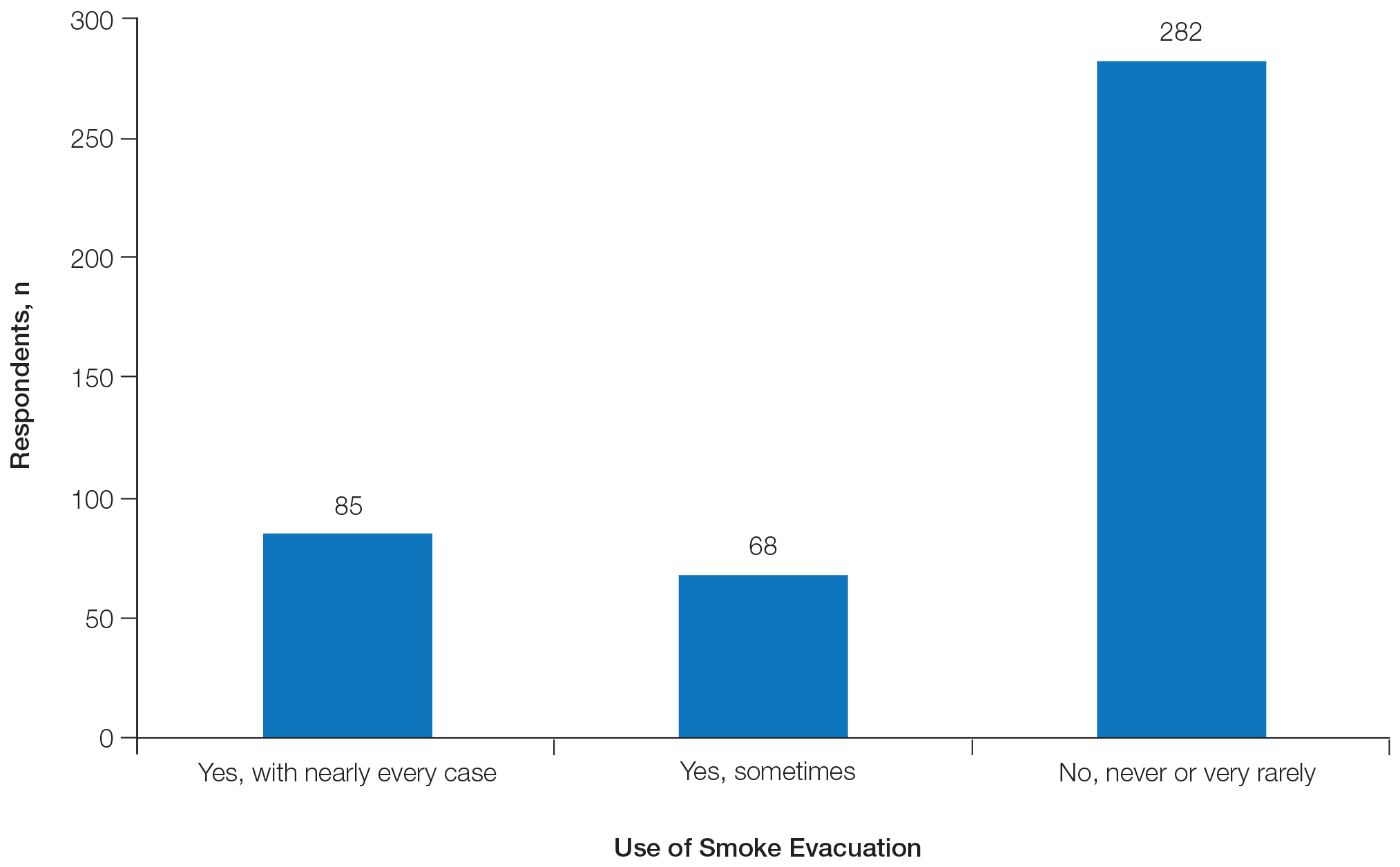

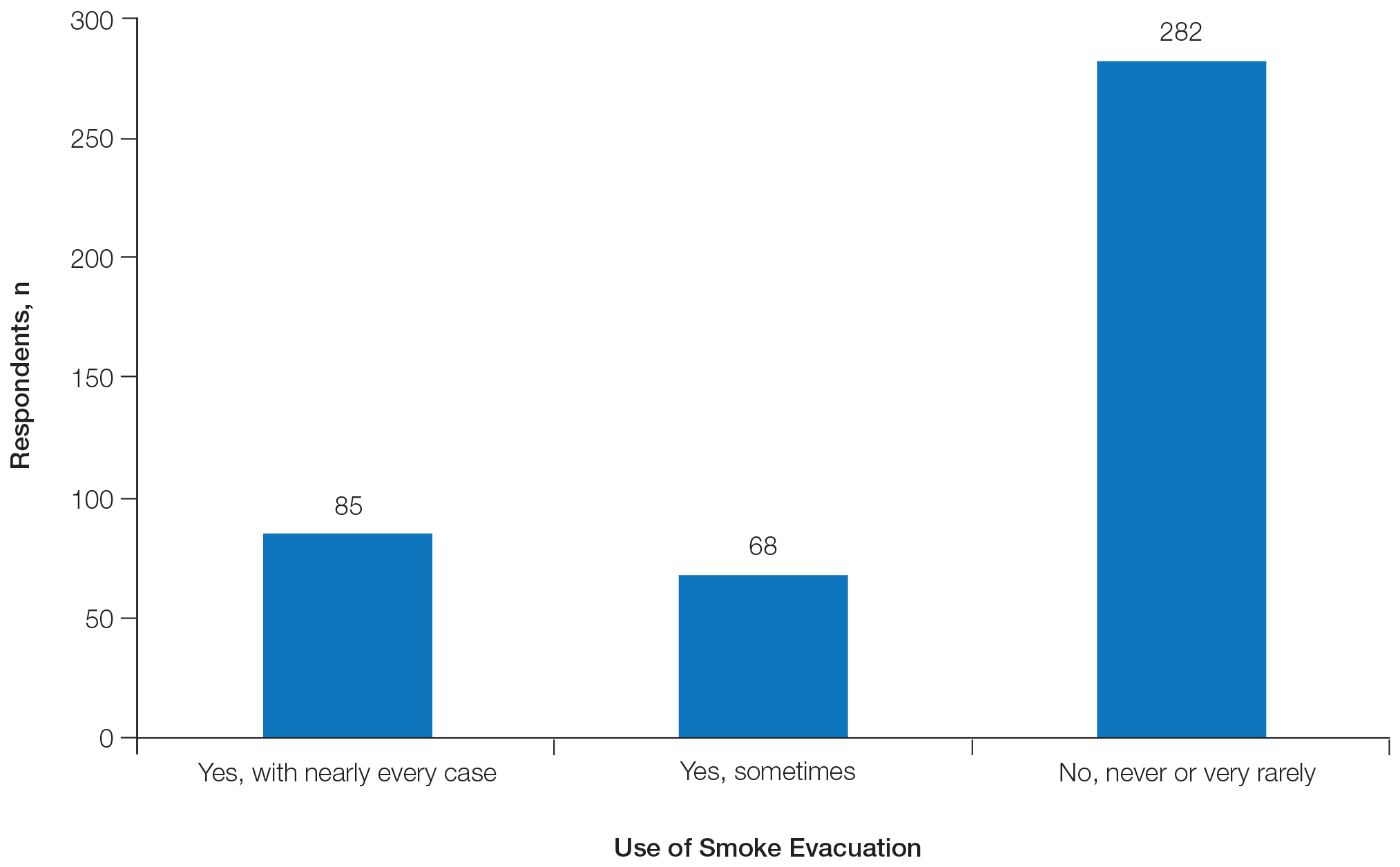

Two hundred eighty-two respondents (64.5%) never or very rarely used smoke evacuation during skin surgical procedures, and only 85 (19.5%) used smoke evacuation with nearly every case. The remaining respondents sometimes used smoke evacuation (Figure 1).

Prior to being presented with the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke and using a value of 5 to 10 to determine if respondents noticed smoke, 54.4% (95% CI, 49.5%-59.1%) did notice intraoperative smoke during procedures. Using a value of 5 to 10 to indicate if respondents were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell, 35.5% (95% CI, 31.0%-40.2%) were bothered or troubled by intraoperative smoke prior to potential hazards being presented.

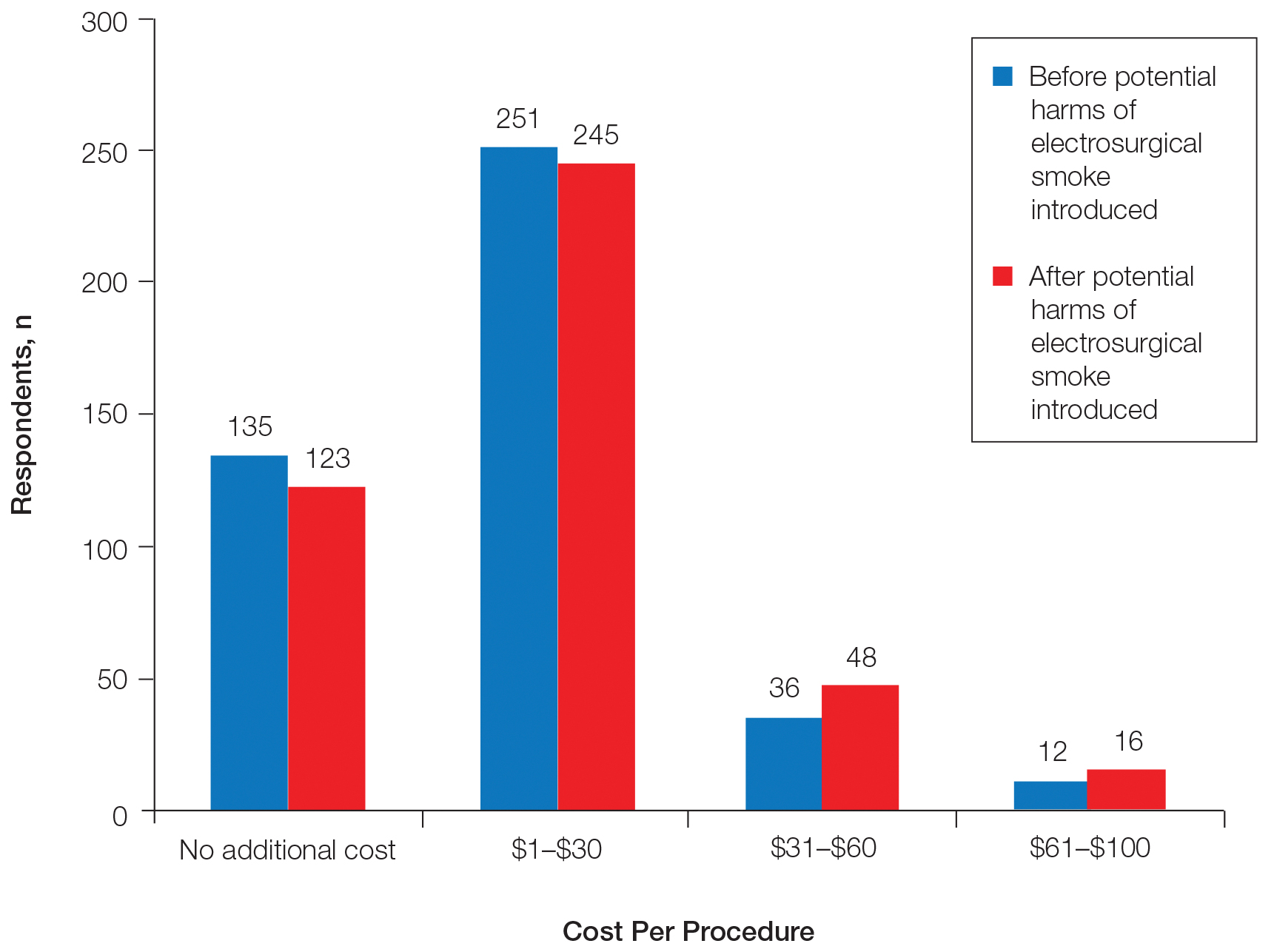

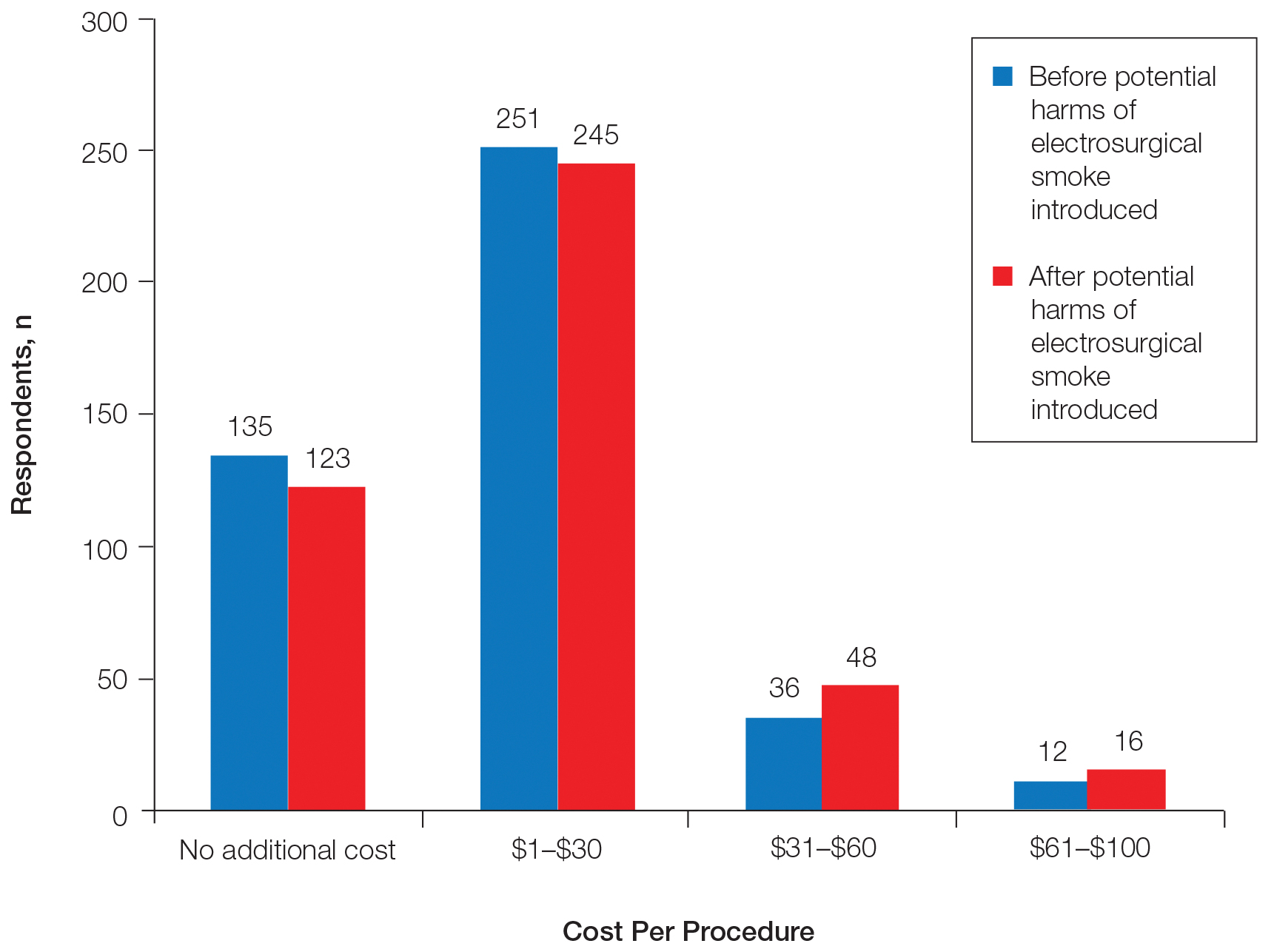

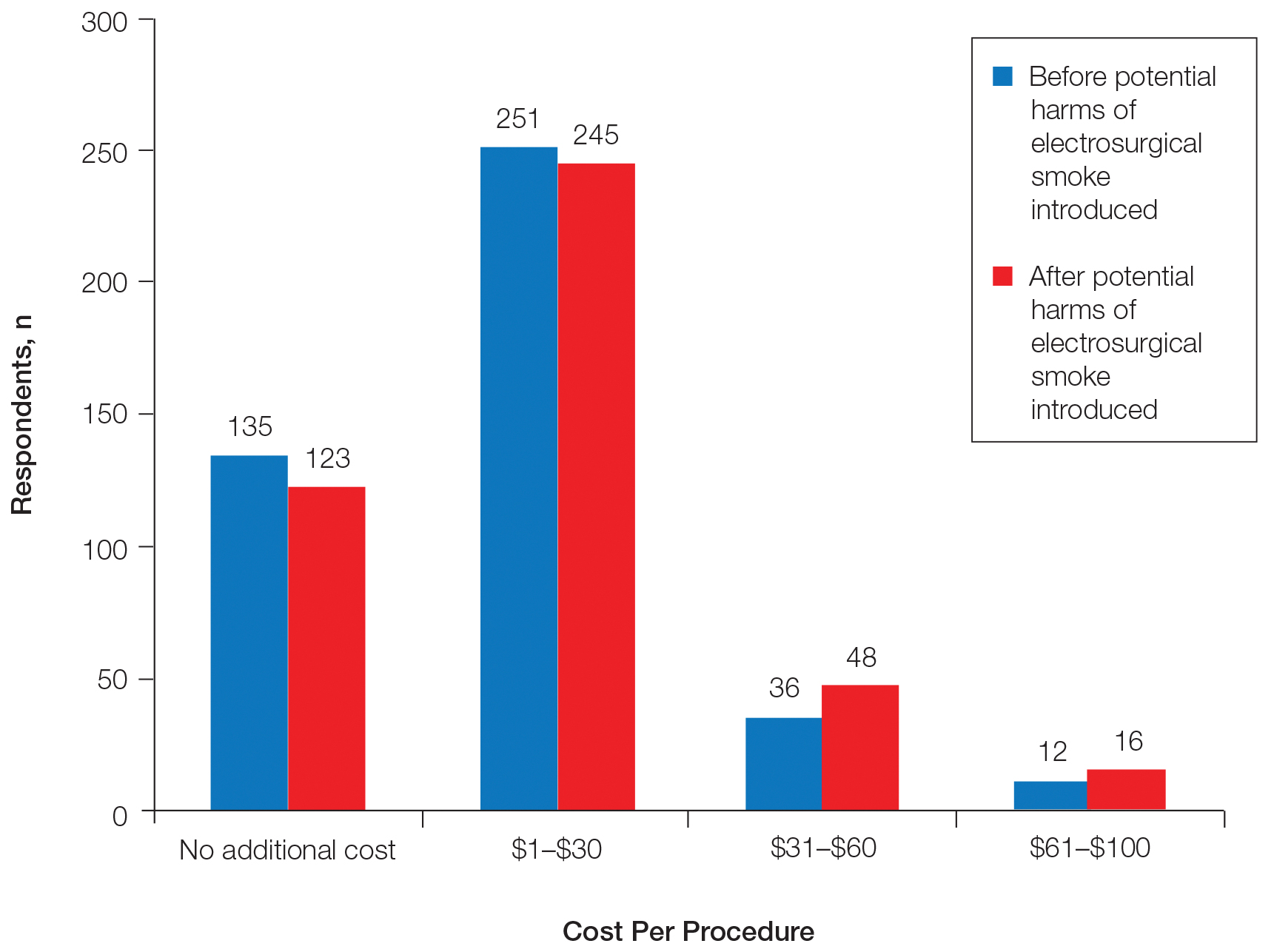

Regarding acceptable increase in cost per procedure for smoke evacuation at baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost; 57.8% of respondents chose the lowest cost grouping of $1 to $30. After being presented with information about the potential harm of intraoperative smoke, the respondents in favor of additional cost increased to 71.5%, which was a small but statistically significant change (P=.0075)(Figure 2).

Respondents were sorted into groups consisting of those who never used smoke evacuation, those who used it occasionally, and those who used it with all smoke-producing procedures. The degree to which respondents noticed intraoperative smoke was strongly correlated with their use of smoke evacuation; those who never used smoke evacuation noticed the presence of smoke more, and those who always used smoke evacuation noticed it less (P=.0002). Similar trends were noted regarding if the smoke smell bothered or troubled respondents (P=.0014).

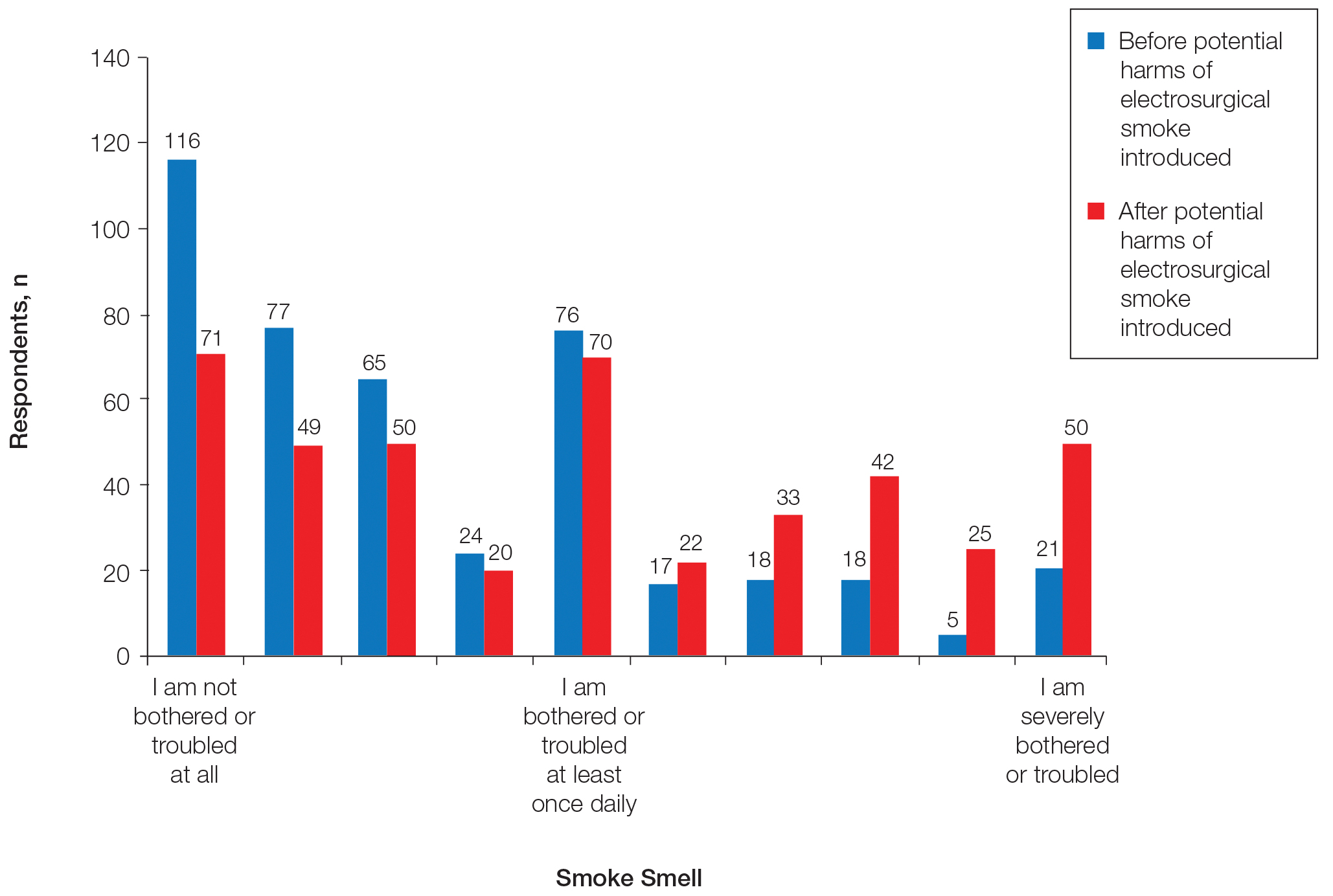

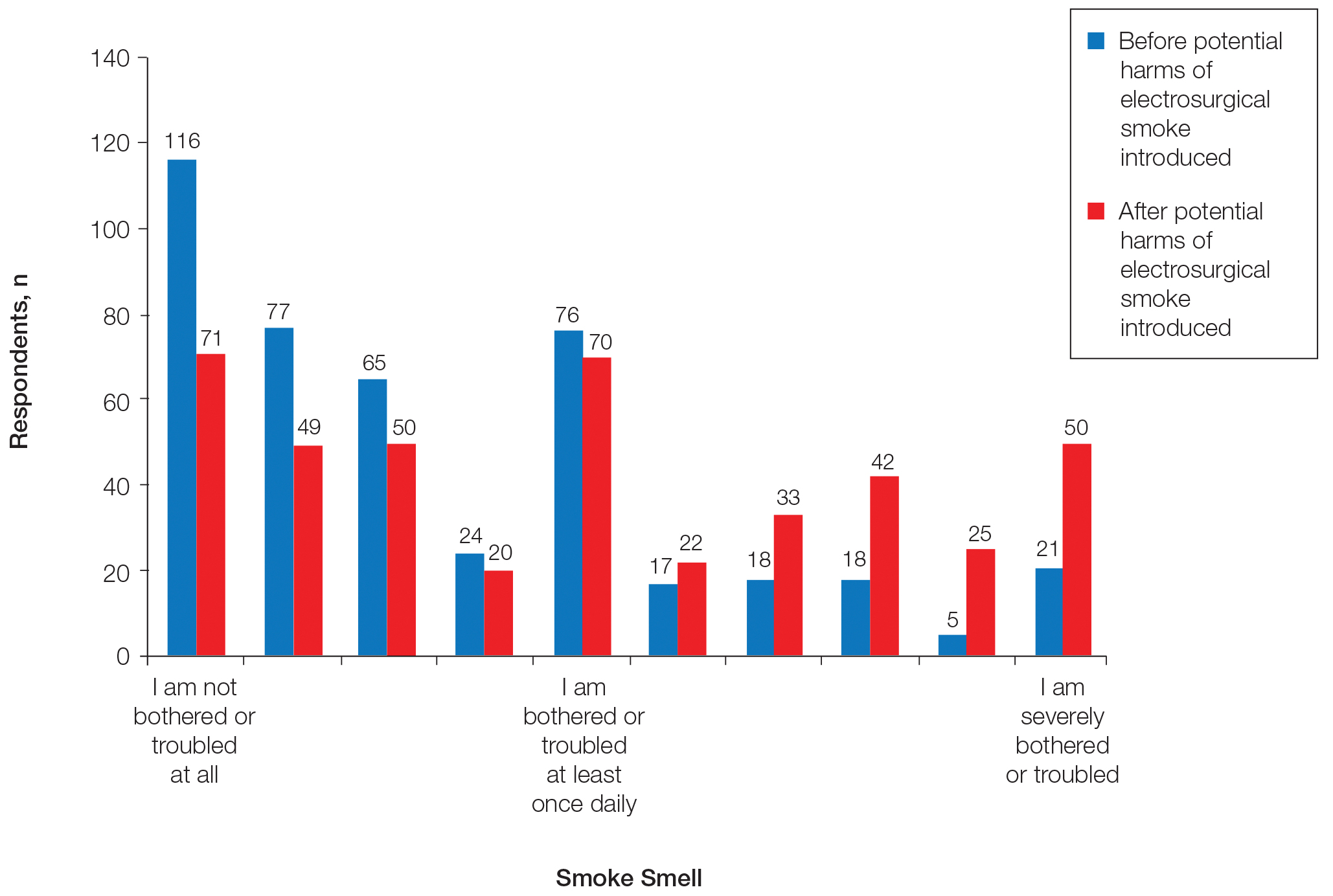

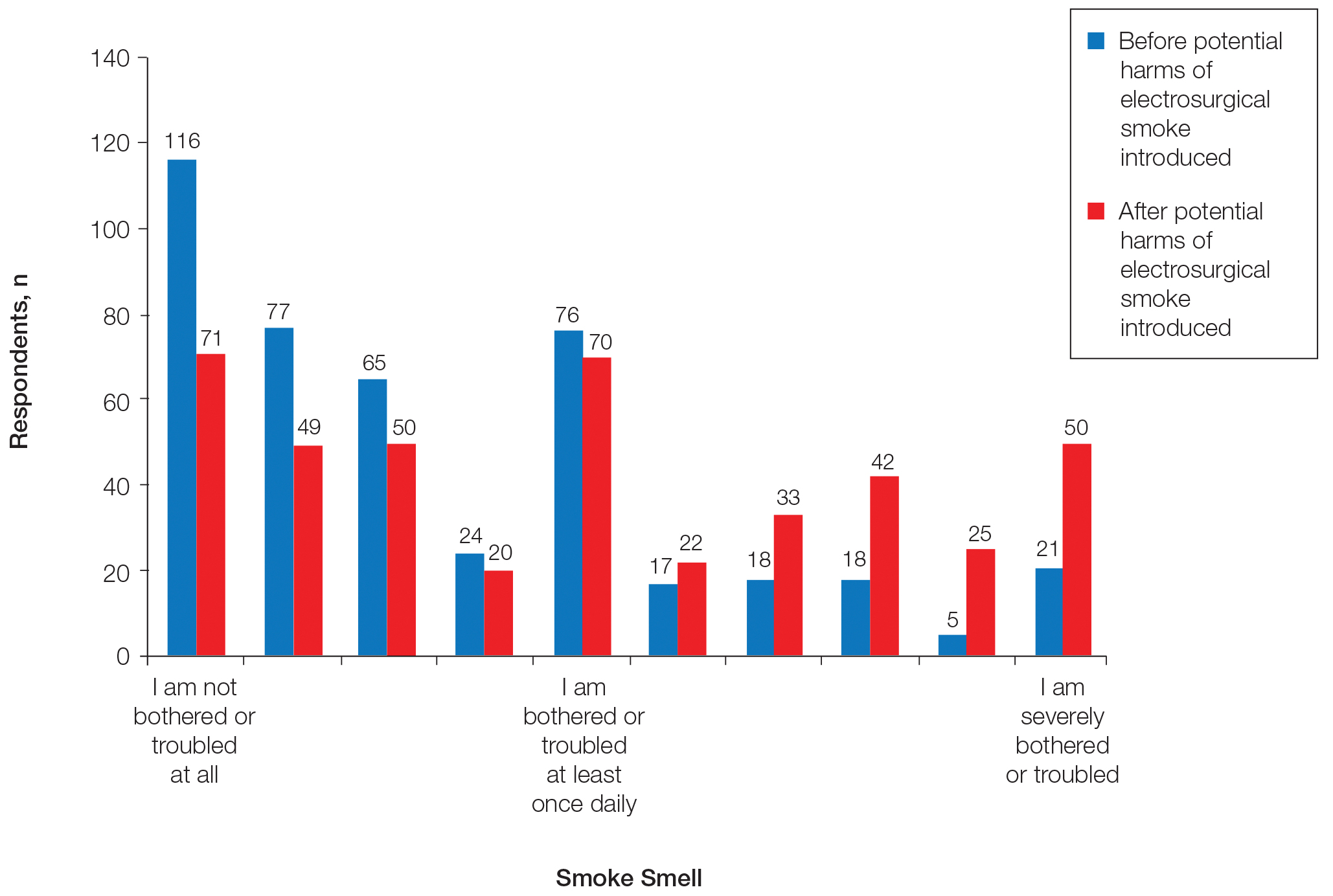

After being presented with the potential risks of electrosurgical smoke, 29 more respondents answered that they were severely bothered by electrosurgical smoke, whereas 45 fewer respondents selected that they were not bothered or troubled at all by electrosurgical smoke (Figure 3). This difference was statistically significant (P<.0001). Fifteen more respondents answered that they would be much more likely to choose to work at a practice with smoke evacuation once the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke was introduced, and 11 were somewhat more likely to choose a practice with smoke evacuation (P<.0001).

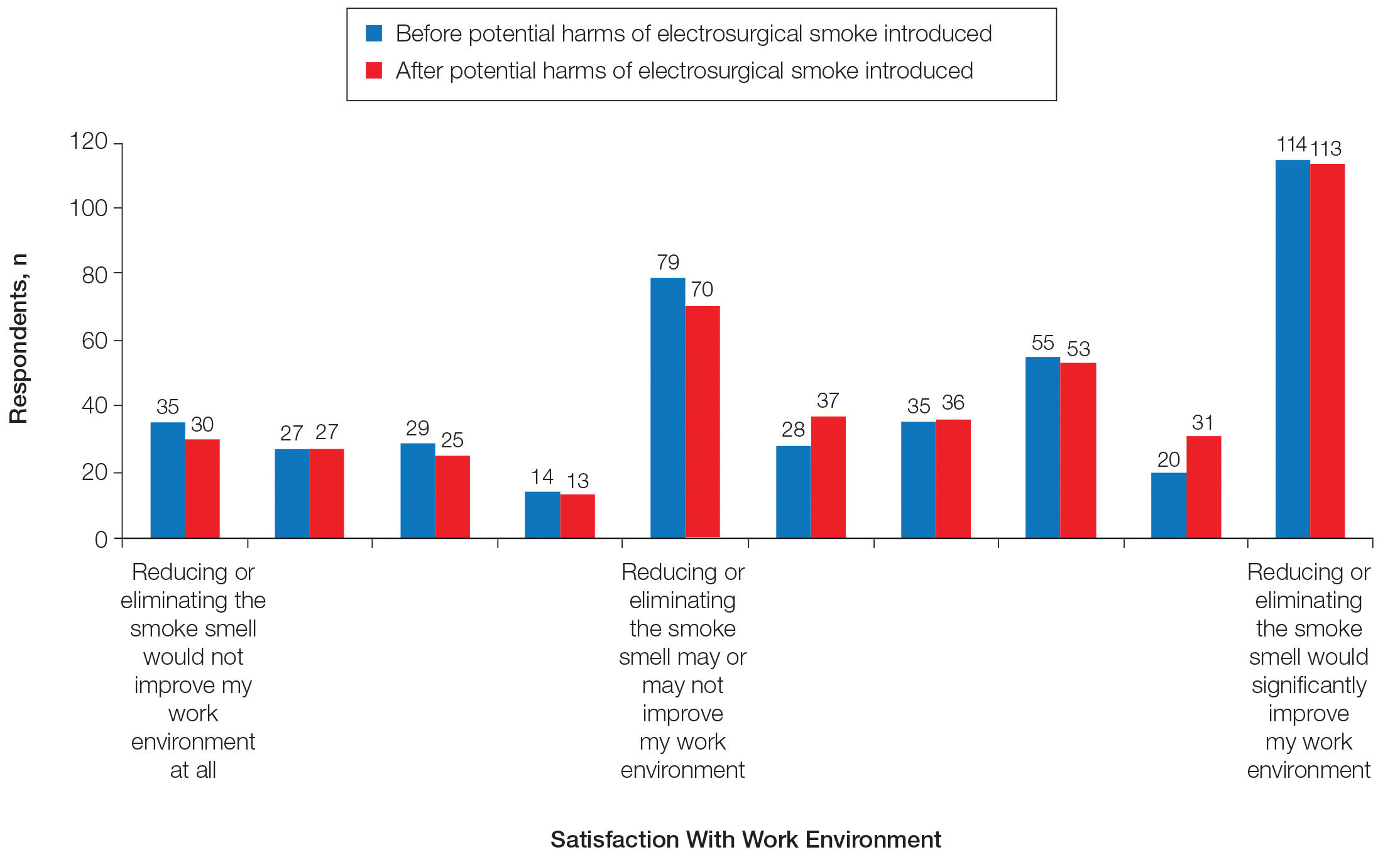

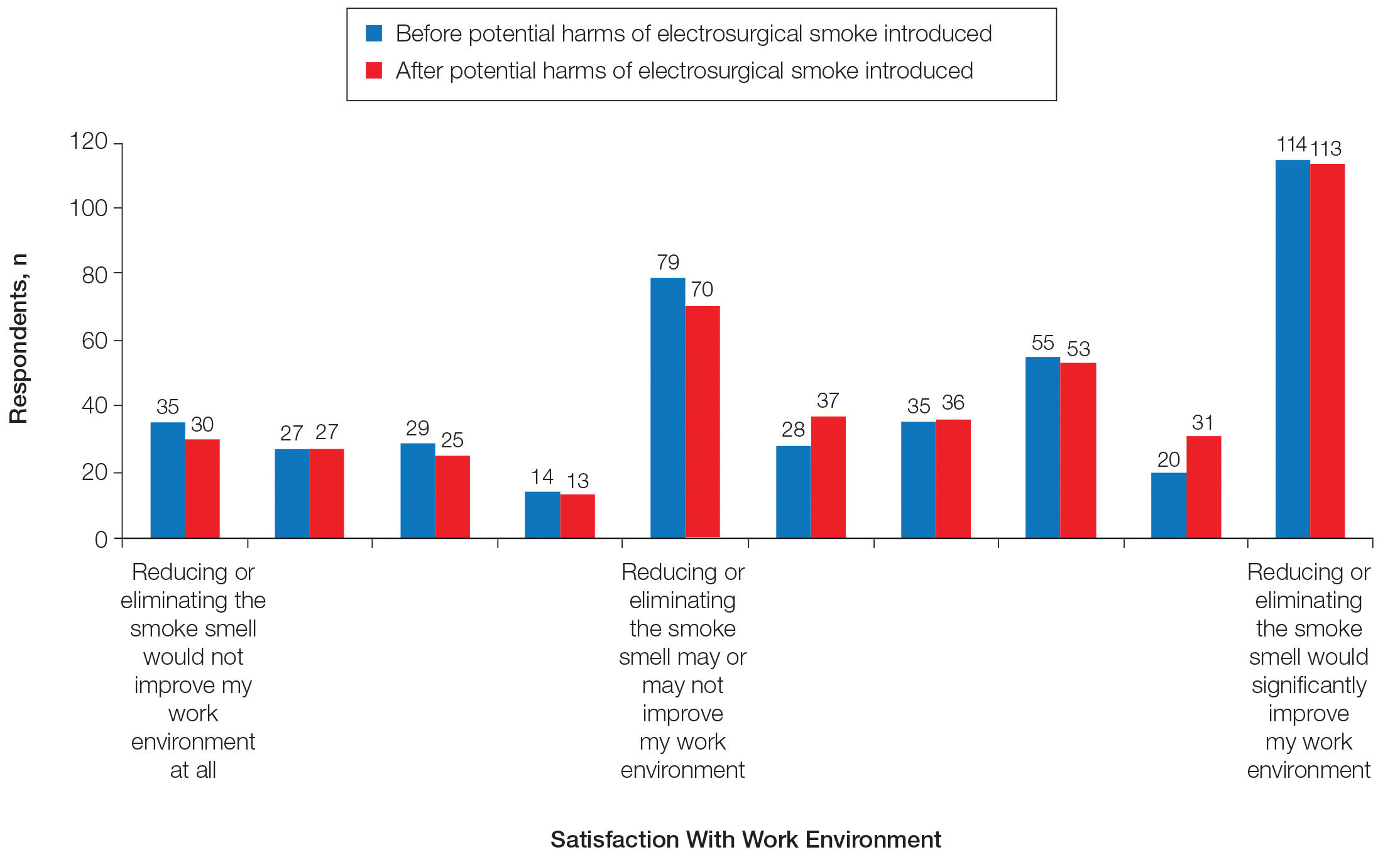

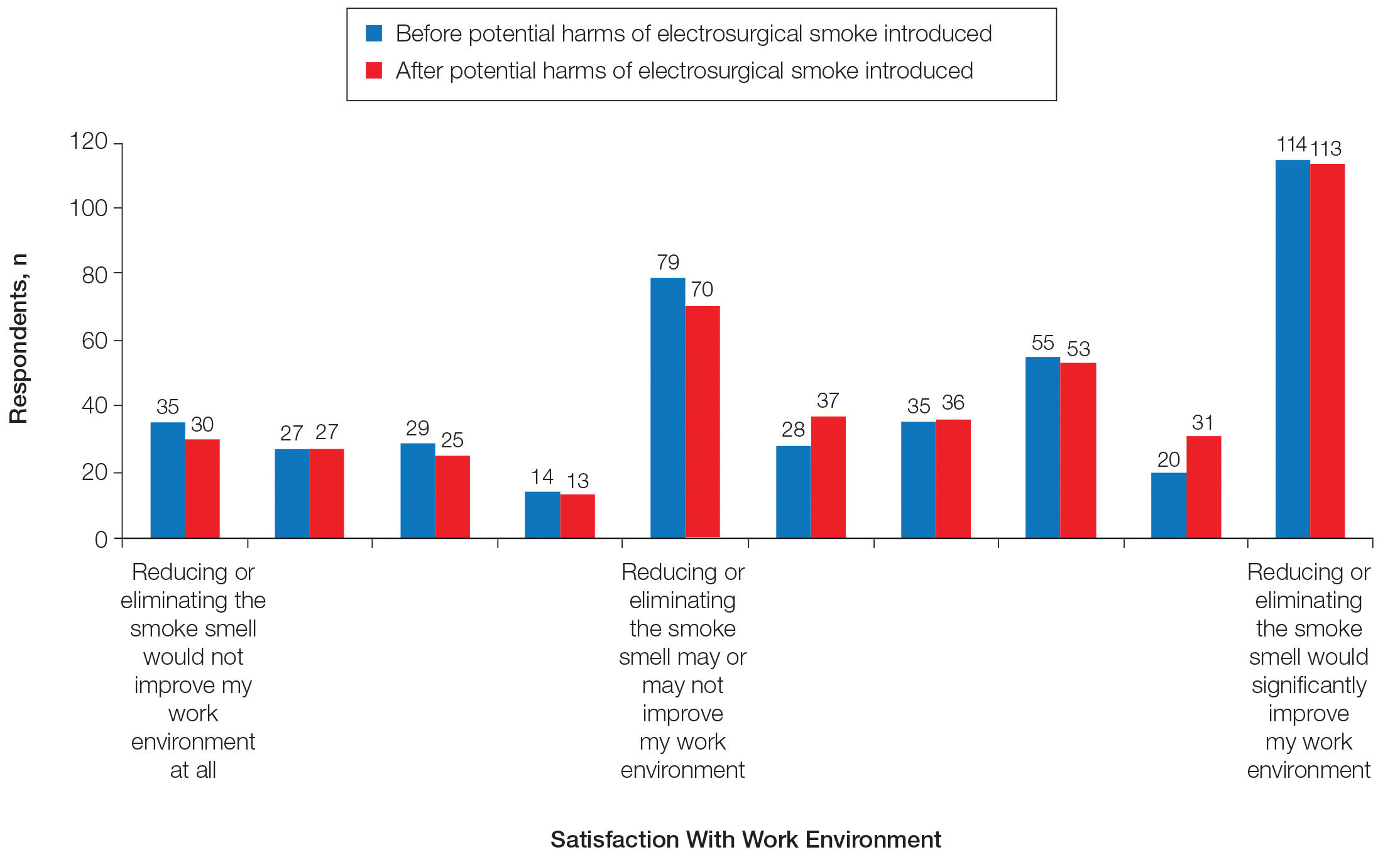

Information about the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke did not statistically significantly affect satisfaction with work environment (P=.3139)(Figure 4).

There were no statistically significant differences between surgeon and staff responses on any questions.

Comment

Developing evidence of health risks associated with electrosurgical smoke plumes has led to an increasing interest in the use of smoke protection or remediation tools during surgical procedures. High-filtration face masks and smoke-evacuation devices protect physicians, staff members, and patients, as well as improve the patient’s clinical experience.

Our study was designed to query dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences. We received 437 responses to our survey (Table). At baseline, 54.4% of respondents noticed and 35.5% were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell produced during skin electrosurgery. These data were intuitively associated in a statistically significant manner with the use of smoke evacuation for respondents; those respondents who more commonly used smoke evacuation were bothered less by electrosurgical smoke, and those respondents who used smoke evacuation less often were more likely to notice and be bothered by surgical smoke.

Once our respondents were presented with the potentially harmful effects of electrosurgical smoke, they became significantly more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke and to want to work in a practice where smoke evacuation was available. This information, however, did not change respondents’ satisfaction with their work environment, and no statistically significant differences were noted between physicians and staff.

At baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost for smoke evacuation, with approximately 58% favoring the lowest cost category we presented ($1–$30). After being presented with information about the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke, 71.5% were in favor of increased cost for smoke evacuation, which was a small but statistically significant increase.

The open-comment section of the survey provided interesting insight into the opinions of our respondents on smoke remediation. It is important to note that statistical analysis cannot be performed with these data, and firm generalizable conclusions cannot be drawn from them; however, they reveal topics that may guide further research and policy and certainly merit mention. Of 437 respondents, 108 left free-text comments. Twenty-six percent were categorized as unqualified proponents (in favor of smoke remediation) and 45% as qualified proponents (defined as an individual who verbalized a desire for smoke remediation but also cited a factor limiting their ability to use it, such as cost or staff availability). Only 12% were firmly against smoke remediation, while the remaining 17% did not comment discernibly for or against smoke remediation, indicating that a majority (71% of our comment section respondents) were in favor of some type of smoke remediation, especially if obstacles such as cost could be addressed. Only a small minority was firmly against smoke remediation.

The comments section of our survey highlighted some of the concerns that dermatologic surgeons and their staff have with electrosurgical smoke evacuation. Thirty percent cited cost as an obstacle to use of these devices, and several comments raised concern about increasing overhead and regulatory demands placed on practices. Many indicated that, without sufficient evidence of the harm caused by electrosurgical smoke, regulation that forces use of smoke remediation devices would represent a costly unfunded mandate. Others referenced the logistical challenges of smoke evacuation and the need for staff assistance. Newer smoke-evacuation wands built into cautery pens address much of this concern regarding logistical and staff challenges and further allow the evacuator tip to be located where it is most effective: 1 cm to 2 in from the point of cautery.21,22

Additionally, 12% of commenters noted that their patients were bothered by the smell of electrosurgical smoke, which is a point that requires further research and is the focus of a current randomized trial at our institution (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02958826).

Our current study is limited in that it is a survey and therefore is subject to response bias. Further, some may assert that the hazards of electrosurgical smoke are not settled science, and although we agree with this point on some level, the study aim was not to prove risk but rather to assess current attitudes and see if awareness of a potential risk influenced those attitudes. Additionally, most responses were from physicians—only 35 responses were from nonphysician staff—so it may be difficult to generalize the findings of this study to staff. The large number of physician respondents, however, can be seen as a strength, and the findings are likely much more generalizable to providers who routinely perform clinic-based surgical procedures involving electrosurgery.

Conclusion

Our study shows that most dermatologists who perform skin surgery notice and are bothered by the smoke produced by electrosurgery to at least some extent. When presented with the possibility that inhaling electrosurgical smoke may be harmful, dermatologists were more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke, more likely to prefer a practice environment where smoke evacuation was available, and more likely to be willing to bear additional cost for smoke evacuation. The free-text comments on our survey highlighted that many dermatologic surgeons are proponents of smoke evacuation but have concerns about cost and potential regulatory challenges associated with smoke evacuation, especially if the potential risks are not settled science. Many logistical concerns for smoke evacuation are addressed with the use of integrated devices. More research is needed to determine the health effects of the surgical smoke we are exposed to daily and the optimal way to limit any risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Richard W. Madsen, PhD (Columbia, Missouri), biostatistician, for his valuable guidance in the statistical analysis of data, interpretation of results, and editorial support in finalizing the manuscript.

- Lewin J, Brauer J, Ostad A. Surgical smoke and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:636-641.

- Garden JM, O’Banion MK, Shelnitz LS, et al. Papillomavirus in the vapor of carbon dioxide laser-treated verrucae. JAMA. 1988;259:1199-1202.

- Sawchuk WS, Weber PJ, Lowy DR, et al. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: detection and protection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:41-49.

- Baggish MS, Poiesz BJ, Joret D, et al. Presence of human immunodeficiency virus DNA in laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:197-203.

- Capizzi PJ, Clay RP, Battey MJ. Microbiologic activity in laser resurfacing plume and debris. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;23:172-174.

- Sebben JE. The hazards of electrosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:869-872.

- Bigony L. Risks associated with exposure to surgical smoke plume: a review of the literature. AORN J. 2007;86:1013-1020.

- Barrett WL, Garber SM. Surgical smoke: a review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:979-987.

- Tomita Y, Mihashi S, Nagata K, et al. Mutagenicity of smoke condensates induced by CO2-laser irradiation and electrocauterization. Mutat Res. 1981;89:145-149.

- Hollmann R, Hort CE, Kammer E, et al. Smoke in the operating theater: an unregarded source of danger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:458-463.

- Hensman C, Baty D, Willis RG, et al. Chemical composition of smoke produced by high-frequency electrosurgery in a closed gaseous environment. An in vitro study. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1017-1019.

- Ulmer B. The hazards of surgical smoke. AORN J. 2008;87:721-734; quiz 735-738.

- Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P, Sze E. Protection of the rat lung from the harmful effects of laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1988;8:248-253.

- Baggish MS, Elbakry M. The effects of laser smoke on the lungs of rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1260-1265.

- Freitag L, Chapman GA, Sielczak M, et al. Laser smoke effect on the bronchial system. Lasers Surg Med. 1987;7:283-288.

- Gracie KW. Hazards of vaporized tissue plume. Surgical Technologist. 2001;33:20-26.

- Giordano BP. Don’t be a victim of surgical smoke. AORN J. 1996;63:520, 522.

- Dikes CN. Is it safe to allow smoke in our operating room? Todays Surg Nurse. 1999;21:15-21; quiz 38-39.

- Wu MP, Ou CS, Chen SL, et al. Complications and recommended practices for electrosurgery in laparoscopy. Am J Surg. 2000;179:67-73.

- Chapman LW, Korta DZ, Lee PK, et al. Awareness of surgical smoke risks and assessment of safety practices during electrosurgery among US dermatology residents. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:467-468.

- Trevor M. Presence of virus in CO2 laser plumes raises infection concern. Hosp Infect Control. 1987;14:166-167.

- Smith JP, Moss CE, Bryant CJ, et al. Evaluation of a smoke evacuator used for laser surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1989;9:276-281.

A growing body of evidence shows that electrosurgical smoke contains both harmful chemicals as well as live material, including blood particles, bacteria, and viruses.1 Both human immunodeficiency virus and human papillomavirus have been identified in surgical smoke plumes, and bacterial colony growth has been demonstrated from electrosurgical smoke specimens, specifically Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria species.2-8 Treating 1 g of tissue with electrocoagulation produces chemical by-products equivalent to burning 6 unfiltered cigarettes,9 which is twice the amount of chemical by-products produced by CO2 laser vaporization of the same quantity of tissue. It is a common misconception that electrosurgical smoke is less hazardous than smoke produced by ablative CO2 procedures.9 Many chemicals are present in electrosurgical smoke plumes, including nitriles, benzenes, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, indoles, phenols, pyridine, pyrrole, styrene, toluene, and xylene.10-12 In animal model studies of rat lungs exposed to surgical smoke, pathologic changes, including interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and emphysema, have been shown in a dose-dependent manner.1,13-16 Diseases and symptoms linked to inhalation of electrosurgical smoke in humans include anemia, eye irritation, hypoxia, dizziness, nasopharyngeal lesions, vomiting, sneezing, throat irritation, and weakness.1,8,17-19 A study of 153 dermatology residents found that more than 70% reported receiving no formal education on the hazards of electrosurgical smoke.20 Approximately 45% were unaware if they had access to smoke evacuation in rooms where electrosurgery was performed. More than 76% were concerned with the infectious risk of electrosurgical smoke, and more than 71% were concerned with its potential carcinogenic risk.20

We surveyed dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

We developed a REDCap survey consisting of 17 questions that was approved by the executive committees of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery for distribution to their dermatologist memberships. It was emailed to eligible participants using their mailing lists. Although the survey was sent directly to member physicians, it was recommended that they forward the survey to their clinical staff to complete.

After responding to an initial set of survey questions, respondents were informed that there is growing evidence of potential harms of inhalation of surgical smoke. They then were asked the same series of survey questions in light of this information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the survey responses was then completed, and free-text responses as a final question of the survey were assessed for themes. Preintervention responses of staff and clinicians noticing smoke and being bothered by smoke were assessed using proportions and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates of the proportions. On most questions, respondents could answer on a scale of 1 to 10. Responses of 5 to 10 on noticing smoke and 5 to 10 on being bothered or troubled by the smoke smell were grouped for analyses. A cross-tabulation using the Bhapkar test for marginal homogeneity was used to assess if information presented on potential smoke hazards changed responses. A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for ordinal responses was used to determine differences between surgeons and staff. A McNemar test was used to determine statistical significance of change in responses to cost. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.

Results

There was a total of 443 responses to our questionnaire. Two respondents answered that they did not work in an office where skin surgery was performed, and 4 respondents did not answer any questions and were therefore excluded, leaving a total of 437 responses (402 physicians and 35 staff members). A summary of the characteristics of the respondents is shown in the Table. Some respondents did not answer each question, leading to fewer than 437 answers for some questions.

Two hundred eighty-two respondents (64.5%) never or very rarely used smoke evacuation during skin surgical procedures, and only 85 (19.5%) used smoke evacuation with nearly every case. The remaining respondents sometimes used smoke evacuation (Figure 1).

Prior to being presented with the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke and using a value of 5 to 10 to determine if respondents noticed smoke, 54.4% (95% CI, 49.5%-59.1%) did notice intraoperative smoke during procedures. Using a value of 5 to 10 to indicate if respondents were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell, 35.5% (95% CI, 31.0%-40.2%) were bothered or troubled by intraoperative smoke prior to potential hazards being presented.

Regarding acceptable increase in cost per procedure for smoke evacuation at baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost; 57.8% of respondents chose the lowest cost grouping of $1 to $30. After being presented with information about the potential harm of intraoperative smoke, the respondents in favor of additional cost increased to 71.5%, which was a small but statistically significant change (P=.0075)(Figure 2).

Respondents were sorted into groups consisting of those who never used smoke evacuation, those who used it occasionally, and those who used it with all smoke-producing procedures. The degree to which respondents noticed intraoperative smoke was strongly correlated with their use of smoke evacuation; those who never used smoke evacuation noticed the presence of smoke more, and those who always used smoke evacuation noticed it less (P=.0002). Similar trends were noted regarding if the smoke smell bothered or troubled respondents (P=.0014).

After being presented with the potential risks of electrosurgical smoke, 29 more respondents answered that they were severely bothered by electrosurgical smoke, whereas 45 fewer respondents selected that they were not bothered or troubled at all by electrosurgical smoke (Figure 3). This difference was statistically significant (P<.0001). Fifteen more respondents answered that they would be much more likely to choose to work at a practice with smoke evacuation once the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke was introduced, and 11 were somewhat more likely to choose a practice with smoke evacuation (P<.0001).

Information about the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke did not statistically significantly affect satisfaction with work environment (P=.3139)(Figure 4).

There were no statistically significant differences between surgeon and staff responses on any questions.

Comment

Developing evidence of health risks associated with electrosurgical smoke plumes has led to an increasing interest in the use of smoke protection or remediation tools during surgical procedures. High-filtration face masks and smoke-evacuation devices protect physicians, staff members, and patients, as well as improve the patient’s clinical experience.

Our study was designed to query dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences. We received 437 responses to our survey (Table). At baseline, 54.4% of respondents noticed and 35.5% were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell produced during skin electrosurgery. These data were intuitively associated in a statistically significant manner with the use of smoke evacuation for respondents; those respondents who more commonly used smoke evacuation were bothered less by electrosurgical smoke, and those respondents who used smoke evacuation less often were more likely to notice and be bothered by surgical smoke.

Once our respondents were presented with the potentially harmful effects of electrosurgical smoke, they became significantly more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke and to want to work in a practice where smoke evacuation was available. This information, however, did not change respondents’ satisfaction with their work environment, and no statistically significant differences were noted between physicians and staff.

At baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost for smoke evacuation, with approximately 58% favoring the lowest cost category we presented ($1–$30). After being presented with information about the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke, 71.5% were in favor of increased cost for smoke evacuation, which was a small but statistically significant increase.

The open-comment section of the survey provided interesting insight into the opinions of our respondents on smoke remediation. It is important to note that statistical analysis cannot be performed with these data, and firm generalizable conclusions cannot be drawn from them; however, they reveal topics that may guide further research and policy and certainly merit mention. Of 437 respondents, 108 left free-text comments. Twenty-six percent were categorized as unqualified proponents (in favor of smoke remediation) and 45% as qualified proponents (defined as an individual who verbalized a desire for smoke remediation but also cited a factor limiting their ability to use it, such as cost or staff availability). Only 12% were firmly against smoke remediation, while the remaining 17% did not comment discernibly for or against smoke remediation, indicating that a majority (71% of our comment section respondents) were in favor of some type of smoke remediation, especially if obstacles such as cost could be addressed. Only a small minority was firmly against smoke remediation.

The comments section of our survey highlighted some of the concerns that dermatologic surgeons and their staff have with electrosurgical smoke evacuation. Thirty percent cited cost as an obstacle to use of these devices, and several comments raised concern about increasing overhead and regulatory demands placed on practices. Many indicated that, without sufficient evidence of the harm caused by electrosurgical smoke, regulation that forces use of smoke remediation devices would represent a costly unfunded mandate. Others referenced the logistical challenges of smoke evacuation and the need for staff assistance. Newer smoke-evacuation wands built into cautery pens address much of this concern regarding logistical and staff challenges and further allow the evacuator tip to be located where it is most effective: 1 cm to 2 in from the point of cautery.21,22

Additionally, 12% of commenters noted that their patients were bothered by the smell of electrosurgical smoke, which is a point that requires further research and is the focus of a current randomized trial at our institution (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02958826).

Our current study is limited in that it is a survey and therefore is subject to response bias. Further, some may assert that the hazards of electrosurgical smoke are not settled science, and although we agree with this point on some level, the study aim was not to prove risk but rather to assess current attitudes and see if awareness of a potential risk influenced those attitudes. Additionally, most responses were from physicians—only 35 responses were from nonphysician staff—so it may be difficult to generalize the findings of this study to staff. The large number of physician respondents, however, can be seen as a strength, and the findings are likely much more generalizable to providers who routinely perform clinic-based surgical procedures involving electrosurgery.

Conclusion

Our study shows that most dermatologists who perform skin surgery notice and are bothered by the smoke produced by electrosurgery to at least some extent. When presented with the possibility that inhaling electrosurgical smoke may be harmful, dermatologists were more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke, more likely to prefer a practice environment where smoke evacuation was available, and more likely to be willing to bear additional cost for smoke evacuation. The free-text comments on our survey highlighted that many dermatologic surgeons are proponents of smoke evacuation but have concerns about cost and potential regulatory challenges associated with smoke evacuation, especially if the potential risks are not settled science. Many logistical concerns for smoke evacuation are addressed with the use of integrated devices. More research is needed to determine the health effects of the surgical smoke we are exposed to daily and the optimal way to limit any risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Richard W. Madsen, PhD (Columbia, Missouri), biostatistician, for his valuable guidance in the statistical analysis of data, interpretation of results, and editorial support in finalizing the manuscript.

A growing body of evidence shows that electrosurgical smoke contains both harmful chemicals as well as live material, including blood particles, bacteria, and viruses.1 Both human immunodeficiency virus and human papillomavirus have been identified in surgical smoke plumes, and bacterial colony growth has been demonstrated from electrosurgical smoke specimens, specifically Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria species.2-8 Treating 1 g of tissue with electrocoagulation produces chemical by-products equivalent to burning 6 unfiltered cigarettes,9 which is twice the amount of chemical by-products produced by CO2 laser vaporization of the same quantity of tissue. It is a common misconception that electrosurgical smoke is less hazardous than smoke produced by ablative CO2 procedures.9 Many chemicals are present in electrosurgical smoke plumes, including nitriles, benzenes, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, indoles, phenols, pyridine, pyrrole, styrene, toluene, and xylene.10-12 In animal model studies of rat lungs exposed to surgical smoke, pathologic changes, including interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and emphysema, have been shown in a dose-dependent manner.1,13-16 Diseases and symptoms linked to inhalation of electrosurgical smoke in humans include anemia, eye irritation, hypoxia, dizziness, nasopharyngeal lesions, vomiting, sneezing, throat irritation, and weakness.1,8,17-19 A study of 153 dermatology residents found that more than 70% reported receiving no formal education on the hazards of electrosurgical smoke.20 Approximately 45% were unaware if they had access to smoke evacuation in rooms where electrosurgery was performed. More than 76% were concerned with the infectious risk of electrosurgical smoke, and more than 71% were concerned with its potential carcinogenic risk.20

We surveyed dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

We developed a REDCap survey consisting of 17 questions that was approved by the executive committees of the American College of Mohs Surgery and the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery for distribution to their dermatologist memberships. It was emailed to eligible participants using their mailing lists. Although the survey was sent directly to member physicians, it was recommended that they forward the survey to their clinical staff to complete.

After responding to an initial set of survey questions, respondents were informed that there is growing evidence of potential harms of inhalation of surgical smoke. They then were asked the same series of survey questions in light of this information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the survey responses was then completed, and free-text responses as a final question of the survey were assessed for themes. Preintervention responses of staff and clinicians noticing smoke and being bothered by smoke were assessed using proportions and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates of the proportions. On most questions, respondents could answer on a scale of 1 to 10. Responses of 5 to 10 on noticing smoke and 5 to 10 on being bothered or troubled by the smoke smell were grouped for analyses. A cross-tabulation using the Bhapkar test for marginal homogeneity was used to assess if information presented on potential smoke hazards changed responses. A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for ordinal responses was used to determine differences between surgeons and staff. A McNemar test was used to determine statistical significance of change in responses to cost. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.

Results

There was a total of 443 responses to our questionnaire. Two respondents answered that they did not work in an office where skin surgery was performed, and 4 respondents did not answer any questions and were therefore excluded, leaving a total of 437 responses (402 physicians and 35 staff members). A summary of the characteristics of the respondents is shown in the Table. Some respondents did not answer each question, leading to fewer than 437 answers for some questions.

Two hundred eighty-two respondents (64.5%) never or very rarely used smoke evacuation during skin surgical procedures, and only 85 (19.5%) used smoke evacuation with nearly every case. The remaining respondents sometimes used smoke evacuation (Figure 1).

Prior to being presented with the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke and using a value of 5 to 10 to determine if respondents noticed smoke, 54.4% (95% CI, 49.5%-59.1%) did notice intraoperative smoke during procedures. Using a value of 5 to 10 to indicate if respondents were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell, 35.5% (95% CI, 31.0%-40.2%) were bothered or troubled by intraoperative smoke prior to potential hazards being presented.

Regarding acceptable increase in cost per procedure for smoke evacuation at baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost; 57.8% of respondents chose the lowest cost grouping of $1 to $30. After being presented with information about the potential harm of intraoperative smoke, the respondents in favor of additional cost increased to 71.5%, which was a small but statistically significant change (P=.0075)(Figure 2).

Respondents were sorted into groups consisting of those who never used smoke evacuation, those who used it occasionally, and those who used it with all smoke-producing procedures. The degree to which respondents noticed intraoperative smoke was strongly correlated with their use of smoke evacuation; those who never used smoke evacuation noticed the presence of smoke more, and those who always used smoke evacuation noticed it less (P=.0002). Similar trends were noted regarding if the smoke smell bothered or troubled respondents (P=.0014).

After being presented with the potential risks of electrosurgical smoke, 29 more respondents answered that they were severely bothered by electrosurgical smoke, whereas 45 fewer respondents selected that they were not bothered or troubled at all by electrosurgical smoke (Figure 3). This difference was statistically significant (P<.0001). Fifteen more respondents answered that they would be much more likely to choose to work at a practice with smoke evacuation once the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke was introduced, and 11 were somewhat more likely to choose a practice with smoke evacuation (P<.0001).

Information about the potential harm of electrosurgical smoke did not statistically significantly affect satisfaction with work environment (P=.3139)(Figure 4).

There were no statistically significant differences between surgeon and staff responses on any questions.

Comment

Developing evidence of health risks associated with electrosurgical smoke plumes has led to an increasing interest in the use of smoke protection or remediation tools during surgical procedures. High-filtration face masks and smoke-evacuation devices protect physicians, staff members, and patients, as well as improve the patient’s clinical experience.

Our study was designed to query dermatologists who perform skin surgery as well as staff members with respect to their experiences with electrosurgical smoke and to observe any difference that information on the potential hazards of electrosurgical smoke may have on their attitudes and preferences. We received 437 responses to our survey (Table). At baseline, 54.4% of respondents noticed and 35.5% were bothered or troubled by the smoke smell produced during skin electrosurgery. These data were intuitively associated in a statistically significant manner with the use of smoke evacuation for respondents; those respondents who more commonly used smoke evacuation were bothered less by electrosurgical smoke, and those respondents who used smoke evacuation less often were more likely to notice and be bothered by surgical smoke.

Once our respondents were presented with the potentially harmful effects of electrosurgical smoke, they became significantly more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke and to want to work in a practice where smoke evacuation was available. This information, however, did not change respondents’ satisfaction with their work environment, and no statistically significant differences were noted between physicians and staff.

At baseline, 68.9% of respondents favored additional cost for smoke evacuation, with approximately 58% favoring the lowest cost category we presented ($1–$30). After being presented with information about the potential dangers of electrosurgical smoke, 71.5% were in favor of increased cost for smoke evacuation, which was a small but statistically significant increase.

The open-comment section of the survey provided interesting insight into the opinions of our respondents on smoke remediation. It is important to note that statistical analysis cannot be performed with these data, and firm generalizable conclusions cannot be drawn from them; however, they reveal topics that may guide further research and policy and certainly merit mention. Of 437 respondents, 108 left free-text comments. Twenty-six percent were categorized as unqualified proponents (in favor of smoke remediation) and 45% as qualified proponents (defined as an individual who verbalized a desire for smoke remediation but also cited a factor limiting their ability to use it, such as cost or staff availability). Only 12% were firmly against smoke remediation, while the remaining 17% did not comment discernibly for or against smoke remediation, indicating that a majority (71% of our comment section respondents) were in favor of some type of smoke remediation, especially if obstacles such as cost could be addressed. Only a small minority was firmly against smoke remediation.

The comments section of our survey highlighted some of the concerns that dermatologic surgeons and their staff have with electrosurgical smoke evacuation. Thirty percent cited cost as an obstacle to use of these devices, and several comments raised concern about increasing overhead and regulatory demands placed on practices. Many indicated that, without sufficient evidence of the harm caused by electrosurgical smoke, regulation that forces use of smoke remediation devices would represent a costly unfunded mandate. Others referenced the logistical challenges of smoke evacuation and the need for staff assistance. Newer smoke-evacuation wands built into cautery pens address much of this concern regarding logistical and staff challenges and further allow the evacuator tip to be located where it is most effective: 1 cm to 2 in from the point of cautery.21,22

Additionally, 12% of commenters noted that their patients were bothered by the smell of electrosurgical smoke, which is a point that requires further research and is the focus of a current randomized trial at our institution (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02958826).

Our current study is limited in that it is a survey and therefore is subject to response bias. Further, some may assert that the hazards of electrosurgical smoke are not settled science, and although we agree with this point on some level, the study aim was not to prove risk but rather to assess current attitudes and see if awareness of a potential risk influenced those attitudes. Additionally, most responses were from physicians—only 35 responses were from nonphysician staff—so it may be difficult to generalize the findings of this study to staff. The large number of physician respondents, however, can be seen as a strength, and the findings are likely much more generalizable to providers who routinely perform clinic-based surgical procedures involving electrosurgery.

Conclusion

Our study shows that most dermatologists who perform skin surgery notice and are bothered by the smoke produced by electrosurgery to at least some extent. When presented with the possibility that inhaling electrosurgical smoke may be harmful, dermatologists were more likely to be bothered by electrosurgical smoke, more likely to prefer a practice environment where smoke evacuation was available, and more likely to be willing to bear additional cost for smoke evacuation. The free-text comments on our survey highlighted that many dermatologic surgeons are proponents of smoke evacuation but have concerns about cost and potential regulatory challenges associated with smoke evacuation, especially if the potential risks are not settled science. Many logistical concerns for smoke evacuation are addressed with the use of integrated devices. More research is needed to determine the health effects of the surgical smoke we are exposed to daily and the optimal way to limit any risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Richard W. Madsen, PhD (Columbia, Missouri), biostatistician, for his valuable guidance in the statistical analysis of data, interpretation of results, and editorial support in finalizing the manuscript.

- Lewin J, Brauer J, Ostad A. Surgical smoke and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:636-641.

- Garden JM, O’Banion MK, Shelnitz LS, et al. Papillomavirus in the vapor of carbon dioxide laser-treated verrucae. JAMA. 1988;259:1199-1202.

- Sawchuk WS, Weber PJ, Lowy DR, et al. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: detection and protection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:41-49.

- Baggish MS, Poiesz BJ, Joret D, et al. Presence of human immunodeficiency virus DNA in laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:197-203.

- Capizzi PJ, Clay RP, Battey MJ. Microbiologic activity in laser resurfacing plume and debris. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;23:172-174.

- Sebben JE. The hazards of electrosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:869-872.

- Bigony L. Risks associated with exposure to surgical smoke plume: a review of the literature. AORN J. 2007;86:1013-1020.

- Barrett WL, Garber SM. Surgical smoke: a review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:979-987.

- Tomita Y, Mihashi S, Nagata K, et al. Mutagenicity of smoke condensates induced by CO2-laser irradiation and electrocauterization. Mutat Res. 1981;89:145-149.

- Hollmann R, Hort CE, Kammer E, et al. Smoke in the operating theater: an unregarded source of danger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:458-463.

- Hensman C, Baty D, Willis RG, et al. Chemical composition of smoke produced by high-frequency electrosurgery in a closed gaseous environment. An in vitro study. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1017-1019.

- Ulmer B. The hazards of surgical smoke. AORN J. 2008;87:721-734; quiz 735-738.

- Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P, Sze E. Protection of the rat lung from the harmful effects of laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1988;8:248-253.

- Baggish MS, Elbakry M. The effects of laser smoke on the lungs of rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1260-1265.

- Freitag L, Chapman GA, Sielczak M, et al. Laser smoke effect on the bronchial system. Lasers Surg Med. 1987;7:283-288.

- Gracie KW. Hazards of vaporized tissue plume. Surgical Technologist. 2001;33:20-26.

- Giordano BP. Don’t be a victim of surgical smoke. AORN J. 1996;63:520, 522.

- Dikes CN. Is it safe to allow smoke in our operating room? Todays Surg Nurse. 1999;21:15-21; quiz 38-39.

- Wu MP, Ou CS, Chen SL, et al. Complications and recommended practices for electrosurgery in laparoscopy. Am J Surg. 2000;179:67-73.

- Chapman LW, Korta DZ, Lee PK, et al. Awareness of surgical smoke risks and assessment of safety practices during electrosurgery among US dermatology residents. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:467-468.

- Trevor M. Presence of virus in CO2 laser plumes raises infection concern. Hosp Infect Control. 1987;14:166-167.

- Smith JP, Moss CE, Bryant CJ, et al. Evaluation of a smoke evacuator used for laser surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1989;9:276-281.

- Lewin J, Brauer J, Ostad A. Surgical smoke and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:636-641.

- Garden JM, O’Banion MK, Shelnitz LS, et al. Papillomavirus in the vapor of carbon dioxide laser-treated verrucae. JAMA. 1988;259:1199-1202.

- Sawchuk WS, Weber PJ, Lowy DR, et al. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: detection and protection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:41-49.

- Baggish MS, Poiesz BJ, Joret D, et al. Presence of human immunodeficiency virus DNA in laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:197-203.

- Capizzi PJ, Clay RP, Battey MJ. Microbiologic activity in laser resurfacing plume and debris. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;23:172-174.

- Sebben JE. The hazards of electrosurgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:869-872.

- Bigony L. Risks associated with exposure to surgical smoke plume: a review of the literature. AORN J. 2007;86:1013-1020.

- Barrett WL, Garber SM. Surgical smoke: a review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:979-987.

- Tomita Y, Mihashi S, Nagata K, et al. Mutagenicity of smoke condensates induced by CO2-laser irradiation and electrocauterization. Mutat Res. 1981;89:145-149.

- Hollmann R, Hort CE, Kammer E, et al. Smoke in the operating theater: an unregarded source of danger. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:458-463.

- Hensman C, Baty D, Willis RG, et al. Chemical composition of smoke produced by high-frequency electrosurgery in a closed gaseous environment. An in vitro study. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1017-1019.

- Ulmer B. The hazards of surgical smoke. AORN J. 2008;87:721-734; quiz 735-738.

- Baggish MS, Baltoyannis P, Sze E. Protection of the rat lung from the harmful effects of laser smoke. Lasers Surg Med. 1988;8:248-253.

- Baggish MS, Elbakry M. The effects of laser smoke on the lungs of rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1260-1265.

- Freitag L, Chapman GA, Sielczak M, et al. Laser smoke effect on the bronchial system. Lasers Surg Med. 1987;7:283-288.

- Gracie KW. Hazards of vaporized tissue plume. Surgical Technologist. 2001;33:20-26.

- Giordano BP. Don’t be a victim of surgical smoke. AORN J. 1996;63:520, 522.

- Dikes CN. Is it safe to allow smoke in our operating room? Todays Surg Nurse. 1999;21:15-21; quiz 38-39.

- Wu MP, Ou CS, Chen SL, et al. Complications and recommended practices for electrosurgery in laparoscopy. Am J Surg. 2000;179:67-73.

- Chapman LW, Korta DZ, Lee PK, et al. Awareness of surgical smoke risks and assessment of safety practices during electrosurgery among US dermatology residents. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:467-468.

- Trevor M. Presence of virus in CO2 laser plumes raises infection concern. Hosp Infect Control. 1987;14:166-167.

- Smith JP, Moss CE, Bryant CJ, et al. Evaluation of a smoke evacuator used for laser surgery. Lasers Surg Med. 1989;9:276-281.

Practice Points

- Growing evidence suggests that the surgical smoke plume generated during electrosurgery may be harmful if inhaled.

- Our survey indicates that this information may affect clinician and staff perceptions about exposure to electrosurgical smoke and its remediation.

Diversity and Inclusivity Are Essential to the Future of Dermatology

Over the last 5 years, there has been an important dialogue among dermatologists about diversity in our specialty that has shifted the mind-set of the dermatology community and highlighted an intent to build a diverse workforce. It is important to reflect on this effort and acknowledge the progress that has been made. Additionally, it also is important to envision what our ideal specialty will look like 10 years from now and to discuss specific ways that we can achieve that vision for the future of dermatology.

At the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), Bruce E. Wintroub, MD, highlighted the importance of diversity in dermatology when he presented the Clarence S. Livingood lecture.1 His discussion was followed by a call to action from Pandya et al2 in 2016, which described the lack of diversity in our specialty (the second least diverse specialty in medicine) and proposed specific steps that can be taken by individuals and organizations to address the issue. In line with this effort, the AAD’s Diversity Task Force, Diversity Mentorship Program,3 and Diversity Champion Initiative were created. The latter program enlisted dermatology residency programs across the country to select a diversity champion who would lead efforts to increase diversity in each participating department, including mentorship of underrepresented-in-medicine college and medical students. The AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop4 (September 12–13, 2019) will be held for the first time prior to the Association of Professors of Dermatology Annual Meeting (September 13–14, 2019) in an attempt to scale up the Diversity Champion Initiative. This workshop has galvanized widespread support and will be collaboratively hosted by the AAD, Association of Professors of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Society for Investigative Dermatology, and Women’s Dermatologic Society.

Current diversity efforts have largely focused on increasing representation in the dermatology workforce. A publication in 2017 challenged the tenets of dermatology resident selection and advocated for holistic review of residency program applicants as one way to address the lack of diversity in dermatology.5 This viewpoint highlighted that dermatology’s traditional focus on US Medical Licensing Examination scores and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership leads to bias6-8; the viewpoint proposed several ways to change the resident selection process to enhance diversity.5 A recent proposal to eliminate numerical scores on the US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and move to a pass/fail grading system aligns well with this viewpoint.9 Defining best practices to perform holistic reviews is an ongoing effort and challenge for many programs, one that will be discussed at the AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop. Implementing best practices will require individual residency programs to develop review processes tailored to departmental resources and strengths. Achieving increased representation must be an active process starting with an explicit commitment to improving diversity.

Through these efforts, we are poised to improve our specialty; however, it is critical to recognize that simply increasing the number of underrepresented dermatologists is not enough to improve diversity in dermatology. What does meaningful change look like? In 10 years, we hope that, in addition to a more inclusive workforce, we will see expanded diversity efforts beyond race and ethnicity; improved cultural competence within dermatology departments and organizations that creates more inclusive places to work, learn, and practice medicine; intentional broader representation in dermatology leadership; high-quality, evidence-based, inclusive, and culturally competent education, patient care, and research; and equal and improved outcomes for all of our patients, particularly those who traditionally experience health care disparities. To this end, ensuring diversity in research and publications is paramount. Academic journals should be actively working to include articles in the literature that help us better understand health care differences, including research that examines the presentations of skin disease in a broad spectrum of study populations, as well as to spotlight and solicit content from diverse voices. Inclusion of a diverse range of participants in research based on human subjects should be a requirement for publication, which would ensure more generalizable data. Diversity in clinical trials is improving,10 but more effort should be devoted to further increasing diversity in medical research. In particular, we need to broaden the inclusivity of dermatology research efforts and outcomes data to include more patients with skin of color as well as other underrepresented groups, thus helping to improve our understanding of the differential effects of certain interventions.

We also must educate trainees and practicing dermatologists to better understand the diagnosis and management of skin diseases in all populations; to this end, it is essential to develop a culturally competent curriculum and continuing medical education on diseases of the skin and hair that affect patients with skin of color as well as cutaneous conditions that present in groups such as sexual and gender minorities.11,12 All dermatologists—not just the experts in academic skin of color and other specialty clinics—should have expertise in the dermatologic care of diverse patients.

We have made notable and important strides with regard to diversity in dermatology by beginning this conversation, identifying problems, coming up with solutions, and implementing them.13 This progress has been made relatively quickly and is commendable; however, we have more work to do before our specialty is inclusive of underrepresented-in-medicine physicians and provides excellent care to all patients.

- Wintroub BE. Dermatology: insuring the future for the patients we serve. Presented at: 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 20-24, 2015; San Francisco, California.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Diversity Mentorship Program: current mentors. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/members/leadership-institute/mentoring/diversity-mentorship-program-current-mentors. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Diversity Champion Workshop. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/meetings/diversity-champion-workshop. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Wayne DB. Are United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 and 2 scores valid measures for postgraduate medical residency selection decisions? Acad Med. 2011;86:48-52.

- Edmond MB, Deschenes JL, Eckler M, et al. Racial bias in using USMLE step 1 scores to grant internal medicine residency interviews. Acad Med. 2001;76:1253-1256.

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659-665.

- The conversation continues: exploring possible changes to USMLE score reporting. US Medical Licensing Examination website. https://www.usmle.org/usmlescoring/. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, et al. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193-198.

- Vashi NA, Patzelt N, Wirya S, et al. Dermatoses caused by cultural practices: therapeutic cultural practices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1-16.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

Over the last 5 years, there has been an important dialogue among dermatologists about diversity in our specialty that has shifted the mind-set of the dermatology community and highlighted an intent to build a diverse workforce. It is important to reflect on this effort and acknowledge the progress that has been made. Additionally, it also is important to envision what our ideal specialty will look like 10 years from now and to discuss specific ways that we can achieve that vision for the future of dermatology.

At the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), Bruce E. Wintroub, MD, highlighted the importance of diversity in dermatology when he presented the Clarence S. Livingood lecture.1 His discussion was followed by a call to action from Pandya et al2 in 2016, which described the lack of diversity in our specialty (the second least diverse specialty in medicine) and proposed specific steps that can be taken by individuals and organizations to address the issue. In line with this effort, the AAD’s Diversity Task Force, Diversity Mentorship Program,3 and Diversity Champion Initiative were created. The latter program enlisted dermatology residency programs across the country to select a diversity champion who would lead efforts to increase diversity in each participating department, including mentorship of underrepresented-in-medicine college and medical students. The AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop4 (September 12–13, 2019) will be held for the first time prior to the Association of Professors of Dermatology Annual Meeting (September 13–14, 2019) in an attempt to scale up the Diversity Champion Initiative. This workshop has galvanized widespread support and will be collaboratively hosted by the AAD, Association of Professors of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Society for Investigative Dermatology, and Women’s Dermatologic Society.

Current diversity efforts have largely focused on increasing representation in the dermatology workforce. A publication in 2017 challenged the tenets of dermatology resident selection and advocated for holistic review of residency program applicants as one way to address the lack of diversity in dermatology.5 This viewpoint highlighted that dermatology’s traditional focus on US Medical Licensing Examination scores and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership leads to bias6-8; the viewpoint proposed several ways to change the resident selection process to enhance diversity.5 A recent proposal to eliminate numerical scores on the US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and move to a pass/fail grading system aligns well with this viewpoint.9 Defining best practices to perform holistic reviews is an ongoing effort and challenge for many programs, one that will be discussed at the AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop. Implementing best practices will require individual residency programs to develop review processes tailored to departmental resources and strengths. Achieving increased representation must be an active process starting with an explicit commitment to improving diversity.