User login

ACE inhibitors and ARBs: Managing potassium and renal function

A highly active, water- and alcohol-soluble, basic pressor substance is formed when renin and renin-activator interact, for which we suggest the name “angiotonin.”

—Irvine H. Page and O.M. Helmer, 1940.1

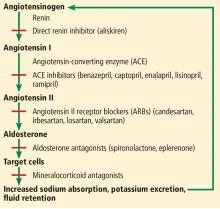

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system regulates salt and, in part, water homeostasis, and therefore blood pressure and fluid balance through its actions on the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels.2 Drugs that target this system—angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)—are used primarily to treat hypertension and also to treat chronic kidney disease and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Controlling blood pressure is important, as hypertension increases the risk of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, and progression of chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, the benefit of these drugs is only partly due to their effect on blood pressure. They also reduce proteinuria, which is a graded risk factor for progression of kidney disease as well as morbidity and death from vascular events.3

Despite the benefits of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, concern about their adverse effects—especially hyperkalemia and a decline in renal function—has led to their underuse in patients likely to derive the greatest benefit.3

ACE INHIBITORS AND ARBs

ACE inhibitors, as their name indicates, inhibit conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II by ACE, resulting in vasodilation of the efferent arteriole and a drop in blood pressure. Inhibition of ACE, a kininase, also results in a rise in kinins. One of these, bradykinin, is associated with some of the side effects of this class of drugs such as cough, which affects 5% to 20% of patients.4 Elevation of bradykinin is also believed to account for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, an uncommon but potentially serious side effect. Kinins are also associated with desirable effects such as lowering blood pressure, increasing insulin sensitivity, and dilating blood vessels.

ARBs were developed as an alternative for patients unable to tolerate the adverse effects of ACE inhibitors. While ACE inhibitors reduce the activity of angiotensin II at both the AT1 and AT2 receptors, ARBs block only the AT1 receptors, thereby inhibiting their vasoconstricting activity on smooth muscle. ARBs also raise the levels of renin, angiotensin I, and angiotensin II as a result of feedback inhibition. Angiotensin II is associated with release of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, cytokines, and chemokines, the consequences of which are also inhibited by ARBs, further preventing renal fibrosis and scarring from chronic inflammation.3

What is the evidence supporting the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs, used singly, reduce blood pressure and proteinuria, slow progression of kidney disease, and improve outcomes in patients who have heart failure, diabetes mellitus, or a history of myocardial infarction.5–11

While dual blockade with the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB lowers blood pressure and proteinuria to a greater degree than monotherapy, dual blockade has been associated with higher rates of complications, including hyperkalemia.12–17

RISK FACTORS FOR HYPERKALEMIA

ACE inhibitors and ARBs raise potassium, especially when used in combination. Other risk factors for hyperkalemia include the following—and note that some of them are also indications for ACE inhibitors and ARBs:

Renal insufficiency. The kidneys are responsible for over 90% of potassium removal in healthy individuals,18,19 and the lower the GFR, the higher the risk of hyperkalemia.3,20,21

Heart failure

Diabetes mellitus6,21–23

Endogenous potassium load due to hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, insulin deficiency, lactic acidosis, or gastrointestinal bleeding

Exogenous potassium load due to dietary consumption or blood products

Other medications, eg, sacubitril-valsartan, aldosterone antagonists, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, potassium-sparing diuretics, beta-adrenergic antagonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin, cyclosporine, trimethoprim, digoxin

Hypertension

Hypoaldosteronism (including type 4 renal tubular acidosis)

Addison disease

Advanced age

Lower body mass index.

Both hypokalemia and hyperkalemia are associated with a higher risk of death,20,21,24 but in patients with heart failure, the survival benefit from ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists outweighs the risk of hyperkalemia.25–27 Weir and Rolfe28 concluded that patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease are at greatest risk of hyperkalemia from renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition, but the increases in potassium levels are small (about 0.1 to 0.3 mmol/L) and unlikely to be clinically significant.

Hyperkalemia tends to recur. Einhorn et al20 found that nearly half of patients with chronic kidney disease who had an episode of hyperkalemia had 1 or more recurrent episodes within a year.

ACE INHIBITORS, ARBs, ABD RENAL FUNCTION

Another concern about using ACE inhibitors and ARBs, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease, is that the serum creatinine level tends to rise when starting these drugs,29 although several studies have shown that an acute rise in creatinine may demonstrate that the drug is actually protecting the kidney.30,31 Hirsch32 described this phenomenon as “prerenal success,” proposing that the decline in GFR is hemodynamic, secondary to a fall in intraglomerular pressure as a result of efferent vasodilation, and therefore should not be reversed.

Schmidt et al,33,34 in a study in 122,363 patients who began ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy, found that cardiorenal outcomes were worse, with higher rates of end-stage renal disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death, in those in whom creatinine rose by 30% or more since starting treatment. This trend was also seen, to a lesser degree, in those with a smaller increase in creatinine, suggesting that even this group of patients should receive close monitoring.

Whether renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors provide a benefit in advanced progressive chronic kidney disease remains unclear.35–37 The Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEi)/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) Withdrawal in Advanced Renal Disease trial (STOP-ACEi),38 currently under way, will provide valuable data to help close this gap in our knowledge. This open-label randomized controlled trial is testing the hypothesis that stopping ACE inhibitor or ARB treatment, or a combination of both, compared with continuing these treatments, will improve or stabilize renal function in patients with progressive stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease.

NEED FOR MONITORING

Taken together, the above data suggest close and regular monitoring is required in patients receiving these drugs. However, monitoring tends to be lax.34,37,39 A 2017 study of adherence to the guidelines for monitoring serum creatinine and potassium after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and subsequent discontinuation found that fewer than 10% of patients had follow-up within the recommended 2 weeks after starting these drugs.34 Most patients with a creatinine rise of 30% or more or a potassium level higher than 6.0 mmol/L continued treatment. There was also no evidence of increased monitoring in those deemed at higher risk of these complications.

WHAT DO THE GUIDELINES SUGGEST?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in chronic kidney disease and hypertension

Target blood pressures vary in guidelines from different organizations.4,40–45 The 2017 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)40 recommend a target blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or less in all patients irrespective of the level of proteinuria and whether they have diabetes mellitus, based on several studies.46–48 In the elderly, other factors such as the risk of hypotension and falls must be taken into consideration in establishing the most appropriate blood pressure target.

In general, a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor is recommended if the patient has diabetes, stage 1, 2, or 3 chronic kidney disease, or proteinuria. For example, the guidelines recommend a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor in diabetic patients with albuminuria.

None of the guidelines recommend routine use of combination therapy.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in heart failure

The 2017 ACC/AHA and Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) guidelines for heart failure49 recommend an ACE inhibitor or ARB for patients with stage C (symptomatic) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, in view of the known cardiovascular morbidity and mortality benefits.

The European Society of Cardiology50 recommends ACE inhibitors for patients with symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, as well as those with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In patients with stable coronary artery disease, an ACE inhibitor should be considered even with normal left ventricular function.

ARBs should be used as alternatives in those unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.

Combination therapy should be avoided due to the increased risk of renal impairment and hyperkalemia but may be considered in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in whom other treatments are unsuitable. These include patients on beta-blockers who cannot tolerate mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone. Combination therapy should be done only under strict supervision.50

Starting ACE or ARB therapy

Close monitoring of serum potassium is recommended during ACE inhibitor or ARB use. Those at greatest risk of hyperkalemia include elderly patients, those taking other medications associated with hyperkalemia, and diabetic patients, because of their higher risk of renovascular disease.

Caution is advised when starting ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy in these high-risk groups as well as in patients with potassium levels higher than 5.0 mmol/L at baseline, at high risk of prerenal acute kidney injury, with known renal insufficiency, and with previous deterioration in renal function on these medications.3,41,51

Before starting therapy, ensure that patients are volume-replete and measure baseline serum electrolytes and creatinine.41,51

The ACC/AHA and HFSA recommend starting at a low dose and titrating upward slowly. If maximal doses are not tolerated, then a lower dose should be maintained.49 The European Society of Cardiology guidelines52 suggest increasing the dose at no less than every 2 weeks unless in an inpatient setting. Blood testing should be done 7 to 14 days after starting therapy, after any titration in dosage, and every 4 months thereafter.53

The guidelines generally agree that a rise in creatinine of up to 30% and a fall in eGFR of up to 25% is acceptable, with the need for regular monitoring, particularly in high-risk groups.40–42,51,52

What if serum potassium or creatinine rises during treatment?

If hyperkalemia arises or renal function declines by a significant amount, one should first address contributing factors. If no improvement is seen, then the dose of the ACE inhibitor or ARB should be reduced by 50% and blood work repeated in 1 to 2 weeks. If the laboratory values do not return to an acceptable level, reducing the dose further or stopping the drug is advised.

Give dietary advice to all patients with chronic kidney disease being considered for a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor or for an increase in dose with a potassium level higher than 4.5 mmol/L. A low-potassium diet should aim for potassium intake of less than 50 or 75 mmol/day and sodium intake of less than 60 mmol/day for hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease.

Review the patient’s medications if the baseline potassium level is higher than 5.0 mmol/L. Consider stopping potassium-sparing agents, digoxin, trimethoprim, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Also think about starting a non–potassium-sparing diuretic as well as sodium bicarbonate to reduce potassium levels. Blood work should be repeated within 2 weeks after these changes.

Do not start a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor, or do not increase the dose, if the potassium level is elevated until measures have been taken to reduce the degree of hyperkalemia.51

In renal transplant recipients, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors are often preferred to manage hypertension in those who have proteinuria or cardiovascular disease. However, the risk of hyperkalemia is also greater with concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine. Management of complications should be approached according to guidelines discussed above.51

Monitor renal function, potassium. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline54 advocates that baseline renal function testing should be followed by repeat blood testing 1 to 2 weeks after starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with ischemic heart disease. The advice is similar when starting therapy in patients with chronic heart failure, emphasizing the need to monitor after each dose increment and to use clinical judgment when deciding to start treatment. The AHA advises caution in patients with renal insufficiency or a potassium level above 5.0 mmol/L.49

Sick day rules. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence encourages discussing “sick day rules” with patients starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. This means patients should be advised to temporarily stop taking nephrotoxic medications, including over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, in any potential state of illness or dehydration, such as diarrhea and vomiting. There is, however, little evidence that this advice can actually reduce the incidence of acute kidney injury.55,56

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Our advice for managing patients receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs is summarized in Table 1.

- Page IH, Helmer OM. A crystalline pressor substance (angiotonin) resulting from the reaction between renin and renin-activator. Exp Med 1940; 71(1):29–42. doi:10.1084/jem.71.1.29

- Steddon S, Ashman N, Chesser A, Cunningham J. Oxford Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016:203–206, 508–509.

- Barratt J, Topham P, Harris K. Oxford Desk Reference. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

- International Kidney Foundation. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO_BP_GL.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators; Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(3):145–153. doi:10.1056/NEJM200001203420301

- Swedberg K, Kjekshus J. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). Am J Cardiol 1988; 62(2):60A–66A. pmid:2839019

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(20):1893–1906. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032292

- Epstein M. Reduction of cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3(12):993–1003. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00289-2

- SOLVD Investigators; Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(5):293–302. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108013250501

- Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al; AIPRD Study Group; Angiotensin-Converting Enzymne Inhibition and Progression of Renal Disease. Proteinuria as a modifiable risk factor for the progression of non-diabetic renal disease. Kidney Int 2001; 60(3):1131–1140. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0600031131.x

- Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Navarese E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of blood pressure-lowering agents in adults with diabetes and kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2015; 385(9982):2047–2056. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62459-4

- Ruggenenti P, Perticucci E, Cravedi P, et al. Role of remission clinics in the longitudinal treatment of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19(6):1213–1224. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007090970

- Makani H, Bangalore S, Desouza KA, Shah A, Messerli FH. Efficacy and safety of dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013; 346:f360. doi:10.1136/bmj.f360

- ONTARGET Investigators; Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(15):1547–1559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

- Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al; VA NEPHRON-D Investigators. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(20):1892–1903.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1303154 - Catalá-López F, Macías Saint-Gerons D, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med 2016; 13(3):e1001971. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001971

- Agarwal R, Afzalpurkar R, Fordtran JS. Pathophysiology of potassium absorption and secretion by the human intestine. Gastroenterology 1994; 107(2):548–571. pmid:8039632

- Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10(6):1050–1060. doi:10.2215/CJN.08580813

- Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1156–1162. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.132

- Nakhoul GN, Huang H, Arrigain S, et al. Serum potassium, end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2015; 41(6):456–463. doi:10.1159/000437151

- Acker CG, Johnson JP, Palevsky PM, Greenberg A. Hyperkalemia in hospitalized patients: causes, adequacy of treatment, and results of an attempt to improve physician compliance with published therapy guidelines. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(8):917–924. pmid:9570179

- Desai AS, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, et al; CHARM Program Investigators. Incidence and predictors of hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the CHARM Program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50(20):1959–1966. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.067

- Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Kittanamongkolchai W, Sakhuja A, Mao MA, Erickson SB. Impact of admission serum potassium on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. QJM 2017; 110(11):713–719. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx118

- Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al; EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(1):11–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009492

- Rossignol P, Dobre D, McMurray JJ, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic significance of hyperkalemia and worsening renal function in patients with heart failure receiving the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone or placebo in addition to optimal medical therapy: results from the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF). Circ Heart Fail 2014; 7(1):51–58. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000792

- Testani JM, Kimmel SE, Dries DL, Coca SG. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4(6):685–691. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963256

- Weir M, Rolfe M. Potassium homeostasis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5(3):531–548. doi:10.2215/CJN.07821109

- Valente M, Bhandari S. Renal function after new treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers. BMJ 2017; 356:j1122. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1122

- Bakris G, Weir M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated elevations in serum creatinine. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(5):685–693. pmid:10724055

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Hirsch S. Pre-renal success. Kidney Int 2012; 81(6):596. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.418

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Serum creatinine elevation after renin-angiotensin system blockade and long term cardiorenal risks: cohort study. BMJ 2017; 356:j791. doi:10.1136/bmj.j791

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Adherence to guidelines for creatinine and potassium monitoring and discontinuation following renin–angiotensin system blockade: a UK general practice-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2017; 7(1):e012818. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012818

- Lund LH, Carrero JJ, Farahmand B, et al. Association between enrollment in a heart failure quality registry and subsequent mortality—a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19(9):1107–1116. doi:10.1002/ejhf.762

- Edner M, Benson L, Dahlstrom U, Lund LH. Association between renin-angiotensin system antagonist use and mortality in heart failure with severe renal insuffuciency: a prospective propensity score-matched cohort study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36(34):2318–2326. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv268

- Epstein M, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Oestreicher N, Knispel J. Evaluation of the treatment gap between clinical guidelines and the utilization of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2015; 21(suppl 11):S212–S220. pmid:26619183

- Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31(2):255–261. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv346

- Raebel MA, Ross C, Xu S, et al. Diabetes and drug-associated hyperkalemia: effect of potassium monitoring. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25(4):326–333. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1228-x

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018; 71(6):e13–e115. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065

- The Renal Association. The UK eCKD Guide. https://renal.org/information-resources/the-uk-eckd-guide. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG127. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013; 34(28):2159–2219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151

- International Kidney Foundation. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/kidney-international-supplements/vol/3/issue/1. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(22):2103–2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Wright J, Bakris G, Greene T. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease. Results from the AASK trial. ACC Current Journal Review 2003; 12(2):37–38. doi:10.1016/s1062-1458(03)00035-7

- Ku E, Bakris G, Johansen K, et al. Acute declines in renal function during intensive BP lowering: implications for future ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28(9):2794–2801. doi:10.1681/ASN.2017010040

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017; 136(6):e137–e161. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(27):2129–2200. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

- Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43(suppl 51):S1–S290. pmid:15114537

- Asenjo RM, Bueno H, Mcintosh M. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). ACE inhibitors and ARBs, a cornerstone in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. www.escardio.org/Education/ESC-Prevention-of-CVD-Programme/Treatment-goals/Cardio-Protective-drugs/angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibitors-ace-inhibitors-and-angiotensin-ii-rec. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- López-Sendón J, Swedberg K, McMurray J, et al; Task Force on ACE-inhibitors of the European Society of Cardiology. Expert consensus document on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. The Task Force on ACE-inhibitors of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004; 25(16):1454–1470. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.003

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG172. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG169. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Think Kidneys. “Sick day” guidance in patients at risk of acute kidney injury: a position statement from the Think Kidneys Board. https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/aki/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/01/Think-Kidneys-Sick-Day-Guidance-2018.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Meaney CJ, Beccari MV, Yang Y, Zhao J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate: a new armamentarium for the treatment of hyperkalemia. Pharmacotherapy 2017; 37(4):401–411. doi:10.1002/phar.1906

A highly active, water- and alcohol-soluble, basic pressor substance is formed when renin and renin-activator interact, for which we suggest the name “angiotonin.”

—Irvine H. Page and O.M. Helmer, 1940.1

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system regulates salt and, in part, water homeostasis, and therefore blood pressure and fluid balance through its actions on the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels.2 Drugs that target this system—angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)—are used primarily to treat hypertension and also to treat chronic kidney disease and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Controlling blood pressure is important, as hypertension increases the risk of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, and progression of chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, the benefit of these drugs is only partly due to their effect on blood pressure. They also reduce proteinuria, which is a graded risk factor for progression of kidney disease as well as morbidity and death from vascular events.3

Despite the benefits of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, concern about their adverse effects—especially hyperkalemia and a decline in renal function—has led to their underuse in patients likely to derive the greatest benefit.3

ACE INHIBITORS AND ARBs

ACE inhibitors, as their name indicates, inhibit conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II by ACE, resulting in vasodilation of the efferent arteriole and a drop in blood pressure. Inhibition of ACE, a kininase, also results in a rise in kinins. One of these, bradykinin, is associated with some of the side effects of this class of drugs such as cough, which affects 5% to 20% of patients.4 Elevation of bradykinin is also believed to account for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, an uncommon but potentially serious side effect. Kinins are also associated with desirable effects such as lowering blood pressure, increasing insulin sensitivity, and dilating blood vessels.

ARBs were developed as an alternative for patients unable to tolerate the adverse effects of ACE inhibitors. While ACE inhibitors reduce the activity of angiotensin II at both the AT1 and AT2 receptors, ARBs block only the AT1 receptors, thereby inhibiting their vasoconstricting activity on smooth muscle. ARBs also raise the levels of renin, angiotensin I, and angiotensin II as a result of feedback inhibition. Angiotensin II is associated with release of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, cytokines, and chemokines, the consequences of which are also inhibited by ARBs, further preventing renal fibrosis and scarring from chronic inflammation.3

What is the evidence supporting the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs, used singly, reduce blood pressure and proteinuria, slow progression of kidney disease, and improve outcomes in patients who have heart failure, diabetes mellitus, or a history of myocardial infarction.5–11

While dual blockade with the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB lowers blood pressure and proteinuria to a greater degree than monotherapy, dual blockade has been associated with higher rates of complications, including hyperkalemia.12–17

RISK FACTORS FOR HYPERKALEMIA

ACE inhibitors and ARBs raise potassium, especially when used in combination. Other risk factors for hyperkalemia include the following—and note that some of them are also indications for ACE inhibitors and ARBs:

Renal insufficiency. The kidneys are responsible for over 90% of potassium removal in healthy individuals,18,19 and the lower the GFR, the higher the risk of hyperkalemia.3,20,21

Heart failure

Diabetes mellitus6,21–23

Endogenous potassium load due to hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, insulin deficiency, lactic acidosis, or gastrointestinal bleeding

Exogenous potassium load due to dietary consumption or blood products

Other medications, eg, sacubitril-valsartan, aldosterone antagonists, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, potassium-sparing diuretics, beta-adrenergic antagonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin, cyclosporine, trimethoprim, digoxin

Hypertension

Hypoaldosteronism (including type 4 renal tubular acidosis)

Addison disease

Advanced age

Lower body mass index.

Both hypokalemia and hyperkalemia are associated with a higher risk of death,20,21,24 but in patients with heart failure, the survival benefit from ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists outweighs the risk of hyperkalemia.25–27 Weir and Rolfe28 concluded that patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease are at greatest risk of hyperkalemia from renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition, but the increases in potassium levels are small (about 0.1 to 0.3 mmol/L) and unlikely to be clinically significant.

Hyperkalemia tends to recur. Einhorn et al20 found that nearly half of patients with chronic kidney disease who had an episode of hyperkalemia had 1 or more recurrent episodes within a year.

ACE INHIBITORS, ARBs, ABD RENAL FUNCTION

Another concern about using ACE inhibitors and ARBs, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease, is that the serum creatinine level tends to rise when starting these drugs,29 although several studies have shown that an acute rise in creatinine may demonstrate that the drug is actually protecting the kidney.30,31 Hirsch32 described this phenomenon as “prerenal success,” proposing that the decline in GFR is hemodynamic, secondary to a fall in intraglomerular pressure as a result of efferent vasodilation, and therefore should not be reversed.

Schmidt et al,33,34 in a study in 122,363 patients who began ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy, found that cardiorenal outcomes were worse, with higher rates of end-stage renal disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death, in those in whom creatinine rose by 30% or more since starting treatment. This trend was also seen, to a lesser degree, in those with a smaller increase in creatinine, suggesting that even this group of patients should receive close monitoring.

Whether renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors provide a benefit in advanced progressive chronic kidney disease remains unclear.35–37 The Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEi)/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) Withdrawal in Advanced Renal Disease trial (STOP-ACEi),38 currently under way, will provide valuable data to help close this gap in our knowledge. This open-label randomized controlled trial is testing the hypothesis that stopping ACE inhibitor or ARB treatment, or a combination of both, compared with continuing these treatments, will improve or stabilize renal function in patients with progressive stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease.

NEED FOR MONITORING

Taken together, the above data suggest close and regular monitoring is required in patients receiving these drugs. However, monitoring tends to be lax.34,37,39 A 2017 study of adherence to the guidelines for monitoring serum creatinine and potassium after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and subsequent discontinuation found that fewer than 10% of patients had follow-up within the recommended 2 weeks after starting these drugs.34 Most patients with a creatinine rise of 30% or more or a potassium level higher than 6.0 mmol/L continued treatment. There was also no evidence of increased monitoring in those deemed at higher risk of these complications.

WHAT DO THE GUIDELINES SUGGEST?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in chronic kidney disease and hypertension

Target blood pressures vary in guidelines from different organizations.4,40–45 The 2017 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)40 recommend a target blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or less in all patients irrespective of the level of proteinuria and whether they have diabetes mellitus, based on several studies.46–48 In the elderly, other factors such as the risk of hypotension and falls must be taken into consideration in establishing the most appropriate blood pressure target.

In general, a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor is recommended if the patient has diabetes, stage 1, 2, or 3 chronic kidney disease, or proteinuria. For example, the guidelines recommend a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor in diabetic patients with albuminuria.

None of the guidelines recommend routine use of combination therapy.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in heart failure

The 2017 ACC/AHA and Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) guidelines for heart failure49 recommend an ACE inhibitor or ARB for patients with stage C (symptomatic) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, in view of the known cardiovascular morbidity and mortality benefits.

The European Society of Cardiology50 recommends ACE inhibitors for patients with symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, as well as those with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In patients with stable coronary artery disease, an ACE inhibitor should be considered even with normal left ventricular function.

ARBs should be used as alternatives in those unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.

Combination therapy should be avoided due to the increased risk of renal impairment and hyperkalemia but may be considered in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in whom other treatments are unsuitable. These include patients on beta-blockers who cannot tolerate mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone. Combination therapy should be done only under strict supervision.50

Starting ACE or ARB therapy

Close monitoring of serum potassium is recommended during ACE inhibitor or ARB use. Those at greatest risk of hyperkalemia include elderly patients, those taking other medications associated with hyperkalemia, and diabetic patients, because of their higher risk of renovascular disease.

Caution is advised when starting ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy in these high-risk groups as well as in patients with potassium levels higher than 5.0 mmol/L at baseline, at high risk of prerenal acute kidney injury, with known renal insufficiency, and with previous deterioration in renal function on these medications.3,41,51

Before starting therapy, ensure that patients are volume-replete and measure baseline serum electrolytes and creatinine.41,51

The ACC/AHA and HFSA recommend starting at a low dose and titrating upward slowly. If maximal doses are not tolerated, then a lower dose should be maintained.49 The European Society of Cardiology guidelines52 suggest increasing the dose at no less than every 2 weeks unless in an inpatient setting. Blood testing should be done 7 to 14 days after starting therapy, after any titration in dosage, and every 4 months thereafter.53

The guidelines generally agree that a rise in creatinine of up to 30% and a fall in eGFR of up to 25% is acceptable, with the need for regular monitoring, particularly in high-risk groups.40–42,51,52

What if serum potassium or creatinine rises during treatment?

If hyperkalemia arises or renal function declines by a significant amount, one should first address contributing factors. If no improvement is seen, then the dose of the ACE inhibitor or ARB should be reduced by 50% and blood work repeated in 1 to 2 weeks. If the laboratory values do not return to an acceptable level, reducing the dose further or stopping the drug is advised.

Give dietary advice to all patients with chronic kidney disease being considered for a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor or for an increase in dose with a potassium level higher than 4.5 mmol/L. A low-potassium diet should aim for potassium intake of less than 50 or 75 mmol/day and sodium intake of less than 60 mmol/day for hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease.

Review the patient’s medications if the baseline potassium level is higher than 5.0 mmol/L. Consider stopping potassium-sparing agents, digoxin, trimethoprim, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Also think about starting a non–potassium-sparing diuretic as well as sodium bicarbonate to reduce potassium levels. Blood work should be repeated within 2 weeks after these changes.

Do not start a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor, or do not increase the dose, if the potassium level is elevated until measures have been taken to reduce the degree of hyperkalemia.51

In renal transplant recipients, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors are often preferred to manage hypertension in those who have proteinuria or cardiovascular disease. However, the risk of hyperkalemia is also greater with concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine. Management of complications should be approached according to guidelines discussed above.51

Monitor renal function, potassium. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline54 advocates that baseline renal function testing should be followed by repeat blood testing 1 to 2 weeks after starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with ischemic heart disease. The advice is similar when starting therapy in patients with chronic heart failure, emphasizing the need to monitor after each dose increment and to use clinical judgment when deciding to start treatment. The AHA advises caution in patients with renal insufficiency or a potassium level above 5.0 mmol/L.49

Sick day rules. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence encourages discussing “sick day rules” with patients starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. This means patients should be advised to temporarily stop taking nephrotoxic medications, including over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, in any potential state of illness or dehydration, such as diarrhea and vomiting. There is, however, little evidence that this advice can actually reduce the incidence of acute kidney injury.55,56

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Our advice for managing patients receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs is summarized in Table 1.

A highly active, water- and alcohol-soluble, basic pressor substance is formed when renin and renin-activator interact, for which we suggest the name “angiotonin.”

—Irvine H. Page and O.M. Helmer, 1940.1

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system regulates salt and, in part, water homeostasis, and therefore blood pressure and fluid balance through its actions on the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels.2 Drugs that target this system—angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)—are used primarily to treat hypertension and also to treat chronic kidney disease and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Controlling blood pressure is important, as hypertension increases the risk of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, and progression of chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, the benefit of these drugs is only partly due to their effect on blood pressure. They also reduce proteinuria, which is a graded risk factor for progression of kidney disease as well as morbidity and death from vascular events.3

Despite the benefits of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, concern about their adverse effects—especially hyperkalemia and a decline in renal function—has led to their underuse in patients likely to derive the greatest benefit.3

ACE INHIBITORS AND ARBs

ACE inhibitors, as their name indicates, inhibit conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II by ACE, resulting in vasodilation of the efferent arteriole and a drop in blood pressure. Inhibition of ACE, a kininase, also results in a rise in kinins. One of these, bradykinin, is associated with some of the side effects of this class of drugs such as cough, which affects 5% to 20% of patients.4 Elevation of bradykinin is also believed to account for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema, an uncommon but potentially serious side effect. Kinins are also associated with desirable effects such as lowering blood pressure, increasing insulin sensitivity, and dilating blood vessels.

ARBs were developed as an alternative for patients unable to tolerate the adverse effects of ACE inhibitors. While ACE inhibitors reduce the activity of angiotensin II at both the AT1 and AT2 receptors, ARBs block only the AT1 receptors, thereby inhibiting their vasoconstricting activity on smooth muscle. ARBs also raise the levels of renin, angiotensin I, and angiotensin II as a result of feedback inhibition. Angiotensin II is associated with release of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, cytokines, and chemokines, the consequences of which are also inhibited by ARBs, further preventing renal fibrosis and scarring from chronic inflammation.3

What is the evidence supporting the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs, used singly, reduce blood pressure and proteinuria, slow progression of kidney disease, and improve outcomes in patients who have heart failure, diabetes mellitus, or a history of myocardial infarction.5–11

While dual blockade with the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB lowers blood pressure and proteinuria to a greater degree than monotherapy, dual blockade has been associated with higher rates of complications, including hyperkalemia.12–17

RISK FACTORS FOR HYPERKALEMIA

ACE inhibitors and ARBs raise potassium, especially when used in combination. Other risk factors for hyperkalemia include the following—and note that some of them are also indications for ACE inhibitors and ARBs:

Renal insufficiency. The kidneys are responsible for over 90% of potassium removal in healthy individuals,18,19 and the lower the GFR, the higher the risk of hyperkalemia.3,20,21

Heart failure

Diabetes mellitus6,21–23

Endogenous potassium load due to hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, insulin deficiency, lactic acidosis, or gastrointestinal bleeding

Exogenous potassium load due to dietary consumption or blood products

Other medications, eg, sacubitril-valsartan, aldosterone antagonists, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, potassium-sparing diuretics, beta-adrenergic antagonists, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin, cyclosporine, trimethoprim, digoxin

Hypertension

Hypoaldosteronism (including type 4 renal tubular acidosis)

Addison disease

Advanced age

Lower body mass index.

Both hypokalemia and hyperkalemia are associated with a higher risk of death,20,21,24 but in patients with heart failure, the survival benefit from ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists outweighs the risk of hyperkalemia.25–27 Weir and Rolfe28 concluded that patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease are at greatest risk of hyperkalemia from renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition, but the increases in potassium levels are small (about 0.1 to 0.3 mmol/L) and unlikely to be clinically significant.

Hyperkalemia tends to recur. Einhorn et al20 found that nearly half of patients with chronic kidney disease who had an episode of hyperkalemia had 1 or more recurrent episodes within a year.

ACE INHIBITORS, ARBs, ABD RENAL FUNCTION

Another concern about using ACE inhibitors and ARBs, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease, is that the serum creatinine level tends to rise when starting these drugs,29 although several studies have shown that an acute rise in creatinine may demonstrate that the drug is actually protecting the kidney.30,31 Hirsch32 described this phenomenon as “prerenal success,” proposing that the decline in GFR is hemodynamic, secondary to a fall in intraglomerular pressure as a result of efferent vasodilation, and therefore should not be reversed.

Schmidt et al,33,34 in a study in 122,363 patients who began ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy, found that cardiorenal outcomes were worse, with higher rates of end-stage renal disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death, in those in whom creatinine rose by 30% or more since starting treatment. This trend was also seen, to a lesser degree, in those with a smaller increase in creatinine, suggesting that even this group of patients should receive close monitoring.

Whether renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors provide a benefit in advanced progressive chronic kidney disease remains unclear.35–37 The Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEi)/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) Withdrawal in Advanced Renal Disease trial (STOP-ACEi),38 currently under way, will provide valuable data to help close this gap in our knowledge. This open-label randomized controlled trial is testing the hypothesis that stopping ACE inhibitor or ARB treatment, or a combination of both, compared with continuing these treatments, will improve or stabilize renal function in patients with progressive stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease.

NEED FOR MONITORING

Taken together, the above data suggest close and regular monitoring is required in patients receiving these drugs. However, monitoring tends to be lax.34,37,39 A 2017 study of adherence to the guidelines for monitoring serum creatinine and potassium after starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and subsequent discontinuation found that fewer than 10% of patients had follow-up within the recommended 2 weeks after starting these drugs.34 Most patients with a creatinine rise of 30% or more or a potassium level higher than 6.0 mmol/L continued treatment. There was also no evidence of increased monitoring in those deemed at higher risk of these complications.

WHAT DO THE GUIDELINES SUGGEST?

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in chronic kidney disease and hypertension

Target blood pressures vary in guidelines from different organizations.4,40–45 The 2017 joint guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)40 recommend a target blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or less in all patients irrespective of the level of proteinuria and whether they have diabetes mellitus, based on several studies.46–48 In the elderly, other factors such as the risk of hypotension and falls must be taken into consideration in establishing the most appropriate blood pressure target.

In general, a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor is recommended if the patient has diabetes, stage 1, 2, or 3 chronic kidney disease, or proteinuria. For example, the guidelines recommend a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor in diabetic patients with albuminuria.

None of the guidelines recommend routine use of combination therapy.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs in heart failure

The 2017 ACC/AHA and Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) guidelines for heart failure49 recommend an ACE inhibitor or ARB for patients with stage C (symptomatic) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, in view of the known cardiovascular morbidity and mortality benefits.

The European Society of Cardiology50 recommends ACE inhibitors for patients with symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, as well as those with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. In patients with stable coronary artery disease, an ACE inhibitor should be considered even with normal left ventricular function.

ARBs should be used as alternatives in those unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors.

Combination therapy should be avoided due to the increased risk of renal impairment and hyperkalemia but may be considered in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in whom other treatments are unsuitable. These include patients on beta-blockers who cannot tolerate mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone. Combination therapy should be done only under strict supervision.50

Starting ACE or ARB therapy

Close monitoring of serum potassium is recommended during ACE inhibitor or ARB use. Those at greatest risk of hyperkalemia include elderly patients, those taking other medications associated with hyperkalemia, and diabetic patients, because of their higher risk of renovascular disease.

Caution is advised when starting ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy in these high-risk groups as well as in patients with potassium levels higher than 5.0 mmol/L at baseline, at high risk of prerenal acute kidney injury, with known renal insufficiency, and with previous deterioration in renal function on these medications.3,41,51

Before starting therapy, ensure that patients are volume-replete and measure baseline serum electrolytes and creatinine.41,51

The ACC/AHA and HFSA recommend starting at a low dose and titrating upward slowly. If maximal doses are not tolerated, then a lower dose should be maintained.49 The European Society of Cardiology guidelines52 suggest increasing the dose at no less than every 2 weeks unless in an inpatient setting. Blood testing should be done 7 to 14 days after starting therapy, after any titration in dosage, and every 4 months thereafter.53

The guidelines generally agree that a rise in creatinine of up to 30% and a fall in eGFR of up to 25% is acceptable, with the need for regular monitoring, particularly in high-risk groups.40–42,51,52

What if serum potassium or creatinine rises during treatment?

If hyperkalemia arises or renal function declines by a significant amount, one should first address contributing factors. If no improvement is seen, then the dose of the ACE inhibitor or ARB should be reduced by 50% and blood work repeated in 1 to 2 weeks. If the laboratory values do not return to an acceptable level, reducing the dose further or stopping the drug is advised.

Give dietary advice to all patients with chronic kidney disease being considered for a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor or for an increase in dose with a potassium level higher than 4.5 mmol/L. A low-potassium diet should aim for potassium intake of less than 50 or 75 mmol/day and sodium intake of less than 60 mmol/day for hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease.

Review the patient’s medications if the baseline potassium level is higher than 5.0 mmol/L. Consider stopping potassium-sparing agents, digoxin, trimethoprim, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Also think about starting a non–potassium-sparing diuretic as well as sodium bicarbonate to reduce potassium levels. Blood work should be repeated within 2 weeks after these changes.

Do not start a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor, or do not increase the dose, if the potassium level is elevated until measures have been taken to reduce the degree of hyperkalemia.51

In renal transplant recipients, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors are often preferred to manage hypertension in those who have proteinuria or cardiovascular disease. However, the risk of hyperkalemia is also greater with concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine. Management of complications should be approached according to guidelines discussed above.51

Monitor renal function, potassium. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline54 advocates that baseline renal function testing should be followed by repeat blood testing 1 to 2 weeks after starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with ischemic heart disease. The advice is similar when starting therapy in patients with chronic heart failure, emphasizing the need to monitor after each dose increment and to use clinical judgment when deciding to start treatment. The AHA advises caution in patients with renal insufficiency or a potassium level above 5.0 mmol/L.49

Sick day rules. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence encourages discussing “sick day rules” with patients starting renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. This means patients should be advised to temporarily stop taking nephrotoxic medications, including over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, in any potential state of illness or dehydration, such as diarrhea and vomiting. There is, however, little evidence that this advice can actually reduce the incidence of acute kidney injury.55,56

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

Our advice for managing patients receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs is summarized in Table 1.

- Page IH, Helmer OM. A crystalline pressor substance (angiotonin) resulting from the reaction between renin and renin-activator. Exp Med 1940; 71(1):29–42. doi:10.1084/jem.71.1.29

- Steddon S, Ashman N, Chesser A, Cunningham J. Oxford Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016:203–206, 508–509.

- Barratt J, Topham P, Harris K. Oxford Desk Reference. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

- International Kidney Foundation. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO_BP_GL.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators; Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(3):145–153. doi:10.1056/NEJM200001203420301

- Swedberg K, Kjekshus J. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). Am J Cardiol 1988; 62(2):60A–66A. pmid:2839019

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(20):1893–1906. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032292

- Epstein M. Reduction of cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3(12):993–1003. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00289-2

- SOLVD Investigators; Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(5):293–302. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108013250501

- Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al; AIPRD Study Group; Angiotensin-Converting Enzymne Inhibition and Progression of Renal Disease. Proteinuria as a modifiable risk factor for the progression of non-diabetic renal disease. Kidney Int 2001; 60(3):1131–1140. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0600031131.x

- Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Navarese E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of blood pressure-lowering agents in adults with diabetes and kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2015; 385(9982):2047–2056. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62459-4

- Ruggenenti P, Perticucci E, Cravedi P, et al. Role of remission clinics in the longitudinal treatment of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19(6):1213–1224. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007090970

- Makani H, Bangalore S, Desouza KA, Shah A, Messerli FH. Efficacy and safety of dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013; 346:f360. doi:10.1136/bmj.f360

- ONTARGET Investigators; Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(15):1547–1559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

- Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al; VA NEPHRON-D Investigators. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(20):1892–1903.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1303154 - Catalá-López F, Macías Saint-Gerons D, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med 2016; 13(3):e1001971. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001971

- Agarwal R, Afzalpurkar R, Fordtran JS. Pathophysiology of potassium absorption and secretion by the human intestine. Gastroenterology 1994; 107(2):548–571. pmid:8039632

- Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10(6):1050–1060. doi:10.2215/CJN.08580813

- Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1156–1162. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.132

- Nakhoul GN, Huang H, Arrigain S, et al. Serum potassium, end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2015; 41(6):456–463. doi:10.1159/000437151

- Acker CG, Johnson JP, Palevsky PM, Greenberg A. Hyperkalemia in hospitalized patients: causes, adequacy of treatment, and results of an attempt to improve physician compliance with published therapy guidelines. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(8):917–924. pmid:9570179

- Desai AS, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, et al; CHARM Program Investigators. Incidence and predictors of hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the CHARM Program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50(20):1959–1966. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.067

- Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Kittanamongkolchai W, Sakhuja A, Mao MA, Erickson SB. Impact of admission serum potassium on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. QJM 2017; 110(11):713–719. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx118

- Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al; EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(1):11–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009492

- Rossignol P, Dobre D, McMurray JJ, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic significance of hyperkalemia and worsening renal function in patients with heart failure receiving the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone or placebo in addition to optimal medical therapy: results from the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF). Circ Heart Fail 2014; 7(1):51–58. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000792

- Testani JM, Kimmel SE, Dries DL, Coca SG. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4(6):685–691. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963256

- Weir M, Rolfe M. Potassium homeostasis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5(3):531–548. doi:10.2215/CJN.07821109

- Valente M, Bhandari S. Renal function after new treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers. BMJ 2017; 356:j1122. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1122

- Bakris G, Weir M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated elevations in serum creatinine. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(5):685–693. pmid:10724055

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Hirsch S. Pre-renal success. Kidney Int 2012; 81(6):596. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.418

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Serum creatinine elevation after renin-angiotensin system blockade and long term cardiorenal risks: cohort study. BMJ 2017; 356:j791. doi:10.1136/bmj.j791

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Adherence to guidelines for creatinine and potassium monitoring and discontinuation following renin–angiotensin system blockade: a UK general practice-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2017; 7(1):e012818. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012818

- Lund LH, Carrero JJ, Farahmand B, et al. Association between enrollment in a heart failure quality registry and subsequent mortality—a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19(9):1107–1116. doi:10.1002/ejhf.762

- Edner M, Benson L, Dahlstrom U, Lund LH. Association between renin-angiotensin system antagonist use and mortality in heart failure with severe renal insuffuciency: a prospective propensity score-matched cohort study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36(34):2318–2326. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv268

- Epstein M, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Oestreicher N, Knispel J. Evaluation of the treatment gap between clinical guidelines and the utilization of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2015; 21(suppl 11):S212–S220. pmid:26619183

- Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31(2):255–261. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv346

- Raebel MA, Ross C, Xu S, et al. Diabetes and drug-associated hyperkalemia: effect of potassium monitoring. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25(4):326–333. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1228-x

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018; 71(6):e13–e115. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065

- The Renal Association. The UK eCKD Guide. https://renal.org/information-resources/the-uk-eckd-guide. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG127. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2013; 34(28):2159–2219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151

- International Kidney Foundation. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/kidney-international-supplements/vol/3/issue/1. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- SPRINT Research Group; Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(22):2103–2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Wright J, Bakris G, Greene T. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease. Results from the AASK trial. ACC Current Journal Review 2003; 12(2):37–38. doi:10.1016/s1062-1458(03)00035-7

- Ku E, Bakris G, Johansen K, et al. Acute declines in renal function during intensive BP lowering: implications for future ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28(9):2794–2801. doi:10.1681/ASN.2017010040

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017; 136(6):e137–e161. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(27):2129–2200. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

- Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43(suppl 51):S1–S290. pmid:15114537

- Asenjo RM, Bueno H, Mcintosh M. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). ACE inhibitors and ARBs, a cornerstone in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. www.escardio.org/Education/ESC-Prevention-of-CVD-Programme/Treatment-goals/Cardio-Protective-drugs/angiotensin-converting-enzyme-inhibitors-ace-inhibitors-and-angiotensin-ii-rec. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- López-Sendón J, Swedberg K, McMurray J, et al; Task Force on ACE-inhibitors of the European Society of Cardiology. Expert consensus document on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. The Task Force on ACE-inhibitors of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004; 25(16):1454–1470. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.003

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG172. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG169. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Think Kidneys. “Sick day” guidance in patients at risk of acute kidney injury: a position statement from the Think Kidneys Board. https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/aki/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/01/Think-Kidneys-Sick-Day-Guidance-2018.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Meaney CJ, Beccari MV, Yang Y, Zhao J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate: a new armamentarium for the treatment of hyperkalemia. Pharmacotherapy 2017; 37(4):401–411. doi:10.1002/phar.1906

- Page IH, Helmer OM. A crystalline pressor substance (angiotonin) resulting from the reaction between renin and renin-activator. Exp Med 1940; 71(1):29–42. doi:10.1084/jem.71.1.29

- Steddon S, Ashman N, Chesser A, Cunningham J. Oxford Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016:203–206, 508–509.

- Barratt J, Topham P, Harris K. Oxford Desk Reference. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

- International Kidney Foundation. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/pdf/KDIGO_BP_GL.pdf. Accessed April 3, 2019.

- Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators; Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(3):145–153. doi:10.1056/NEJM200001203420301

- Swedberg K, Kjekshus J. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). Am J Cardiol 1988; 62(2):60A–66A. pmid:2839019

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(20):1893–1906. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032292

- Epstein M. Reduction of cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease by mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3(12):993–1003. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00289-2

- SOLVD Investigators; Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991; 325(5):293–302. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108013250501

- Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al; AIPRD Study Group; Angiotensin-Converting Enzymne Inhibition and Progression of Renal Disease. Proteinuria as a modifiable risk factor for the progression of non-diabetic renal disease. Kidney Int 2001; 60(3):1131–1140. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0600031131.x

- Palmer SC, Mavridis D, Navarese E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of blood pressure-lowering agents in adults with diabetes and kidney disease: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2015; 385(9982):2047–2056. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62459-4

- Ruggenenti P, Perticucci E, Cravedi P, et al. Role of remission clinics in the longitudinal treatment of CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19(6):1213–1224. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007090970

- Makani H, Bangalore S, Desouza KA, Shah A, Messerli FH. Efficacy and safety of dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013; 346:f360. doi:10.1136/bmj.f360

- ONTARGET Investigators; Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(15):1547–1559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

- Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al; VA NEPHRON-D Investigators. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(20):1892–1903.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1303154 - Catalá-López F, Macías Saint-Gerons D, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med 2016; 13(3):e1001971. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001971

- Agarwal R, Afzalpurkar R, Fordtran JS. Pathophysiology of potassium absorption and secretion by the human intestine. Gastroenterology 1994; 107(2):548–571. pmid:8039632

- Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10(6):1050–1060. doi:10.2215/CJN.08580813

- Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1156–1162. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.132

- Nakhoul GN, Huang H, Arrigain S, et al. Serum potassium, end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2015; 41(6):456–463. doi:10.1159/000437151

- Acker CG, Johnson JP, Palevsky PM, Greenberg A. Hyperkalemia in hospitalized patients: causes, adequacy of treatment, and results of an attempt to improve physician compliance with published therapy guidelines. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(8):917–924. pmid:9570179

- Desai AS, Swedberg K, McMurray JJ, et al; CHARM Program Investigators. Incidence and predictors of hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the CHARM Program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50(20):1959–1966. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.067

- Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Kittanamongkolchai W, Sakhuja A, Mao MA, Erickson SB. Impact of admission serum potassium on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. QJM 2017; 110(11):713–719. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx118

- Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al; EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(1):11–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009492

- Rossignol P, Dobre D, McMurray JJ, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic significance of hyperkalemia and worsening renal function in patients with heart failure receiving the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone or placebo in addition to optimal medical therapy: results from the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF). Circ Heart Fail 2014; 7(1):51–58. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000792

- Testani JM, Kimmel SE, Dries DL, Coca SG. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail 2011; 4(6):685–691. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963256

- Weir M, Rolfe M. Potassium homeostasis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5(3):531–548. doi:10.2215/CJN.07821109

- Valente M, Bhandari S. Renal function after new treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers. BMJ 2017; 356:j1122. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1122

- Bakris G, Weir M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated elevations in serum creatinine. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(5):685–693. pmid:10724055

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(12):861–869. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011161

- Hirsch S. Pre-renal success. Kidney Int 2012; 81(6):596. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.418

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Serum creatinine elevation after renin-angiotensin system blockade and long term cardiorenal risks: cohort study. BMJ 2017; 356:j791. doi:10.1136/bmj.j791

- Schmidt M, Mansfield KE, Bhaskaran K, et al. Adherence to guidelines for creatinine and potassium monitoring and discontinuation following renin–angiotensin system blockade: a UK general practice-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2017; 7(1):e012818. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012818

- Lund LH, Carrero JJ, Farahmand B, et al. Association between enrollment in a heart failure quality registry and subsequent mortality—a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19(9):1107–1116. doi:10.1002/ejhf.762

- Edner M, Benson L, Dahlstrom U, Lund LH. Association between renin-angiotensin system antagonist use and mortality in heart failure with severe renal insuffuciency: a prospective propensity score-matched cohort study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36(34):2318–2326. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv268

- Epstein M, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Oestreicher N, Knispel J. Evaluation of the treatment gap between clinical guidelines and the utilization of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2015; 21(suppl 11):S212–S220. pmid:26619183

- Bhandari S, Ives N, Brettell EA, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker withdrawal in advanced renal disease: the STOP-ACEi trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31(2):255–261. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv346

- Raebel MA, Ross C, Xu S, et al. Diabetes and drug-associated hyperkalemia: effect of potassium monitoring. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25(4):326–333. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1228-x