User login

Five genetic variations associated with same-sex sexual behavior

There is no single “gay gene.”

There are, however, signals that nonheterosexual behavior has at least some genetic component, according to Andrea Ganna, PhD, and colleagues.

Five candidate genes found in a half-million subject genetic study each account for less than 1% of the variance in same-sex sexual behavior, the scientists found. Over the entire genome, genetic variants accounted for less than a quarter of such behavior.

None of the genetic signals can reliably predict sexual behavior, Benjamin Neale, PhD, director of genetics in the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in a telebriefing that included Dr. Ganna, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab. Instead, the variability of human sexuality is an entirely natural continuum of human behavior.

“Whether we are attracted exclusively to the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes falls along a spectrum that is an integral, and entirely normal, part of the human experience,” said Dr. Neale. “The choice of a sexual partner and the fraction of partners that are of the same sex are all consistent with this diversity being a key feature of our sexual behavior as a species and this diversity is a natural part of being human.”

The study, published in Science, clarifies findings of smaller, previous studies, which determined that sexual behavior is a combination of genetics and environment – although environment is a much more difficult association to assess.

“[Environment] can range from anything in utero, all the way all the way through who you happen to stand next to on the tube in the morning, right? That’s all potentially environmental factors that can have some influence on complex traits and so we don’t really understand,” Dr. Neale said.

However, he added, the concept of individual choice in sexual behaviors was beyond the scope of the study, which strictly centered on genetic associations with sexual behavior.

The study combined genetic information from three extant databases (the U.K. Biobank, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation, and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden) with newly collected data from 23andMe, the technology company that provides at-home genetics tests largely used to determine ethnic origin.

The primary phenotype investigated was a binary measure: self-reported sexual behavior with someone of the same sex (nonheterosexuality) or someone of the opposite sex (heterosexuality).

“The binary variable also collapses rich and multifaceted diversity among nonheterosexuality individuals, wrote Dr. Ganna and his coauthors. Therefore, “we explored finer-scaled measurements and some of the complexities of the phenotype, although intricacies of the social and cultural influences on sexuality made it impossible to fully explore this complexity.”

The team also performed replication analyses on three smaller datasets: the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation (2,308 U.S. adult males), Add Health (4,755 U.S. young adults), and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (8,093 Swedish adolescents). Data were available for 188,825 males and 220,170 females overall. When broken down by sexual behavior, data were available for 1,766 homosexual and 180,431 heterosexual males, and 693 homosexual and 214,062 heterosexual females.

The team identified two genes that significantly predicted same-sex sexual behavior (rs11114975-12q21.31 and rs10261857-7q31.2). Two more genes predicted same-sex sexual behavior in males only (rs28371400-15q21.3 and rs34730029-11q12.1), and one additional gene predicted the behavior in females only (rs13135637-4p14).

Three of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally replicated those in some of the other datasets, despite the much smaller sample sizes.

“The SNPs that reached genome-wide significance had very small effects (odds ratio, 1.1),” the authors wrote. “For example, in the U.K. Biobank, males with a GT genotype at the rs34730029 locus had 0.4% higher prevalence of same-sex sexual behavior than those with a TT genotype. Nevertheless, the contribution of all measured common SNPs in aggregate was estimated to [account for] 8%-25% of variation in female and male same-sex sexual behavior. … The discrepancy between the variance captured by the significant SNPs and all common SNPs suggests that same-sex sexual behavior, like most complex human traits, is influenced by the small, additive effects of very many genetic variants, most of which cannot be detected at the current sample size.”

The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden contained the youngest subjects. The polygenic scores in this dataset were significantly associated with sexual attraction at age 15 years, “suggesting that at least some of the genetic influences on same-sex sexual behavior manifest early in sexual development.”

The team also investigated the biological pathways associated with the SNPs. Among the male variants, rs34730029-11q12.1 contains numerous olfactory receptor genes.

“Second, rs28371400-15q21.3 had several indications of being involved in sex hormone regulation. The allele positively associated with same-sex sexual behavior is associated with higher rate of male pattern balding, in which sex-hormone sensitivity is implicated,” they wrote.

This is located near the TCF12 gene, related to a normal gonadal development in mice.

Among women, there were inverse associations with the level of sex hormone–binding globulin, which regulates the balance between testosterone and estrogen.

There were significant associations with some mental health traits, including loneliness, openness to experience, and risky behaviors such as smoking and using cannabis. There were also associations with depression and schizophrenia. The genetic correlations for bipolar disorder, cannabis use, and number of sexual partners were significantly higher in females than in males.

“We emphasize that the causal processes underlying these genetic correlations are unclear and could be generated by environmental factors relating to prejudice against individuals engaging in same-sex sexual behavior,” the authors wrote.

In an interview, Jack Drescher, MD, said he was not surprised by the findings and cited the results a twin study by J. Michael Bailey, PhD, and Richard C. Pillard, MD, as evidence of the complexities surrounding sexual orientation. The study examined the likelihood of one twin having a gay twin (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Dec;48[12]:1089-96).

“If you were a gay identical twin, you had a 52% chance of having a gay twin, he said. “If you were a gay fraternal twin, you only had a 22% chance of having a gay twin. The chance of an adoptive brother being gay was 11%. If homosexuality were simply a result of simple genetic transmission, then one would expect closer to 100% gay identical twins, since they both have the same genes.”

Dr. Drescher, clinical professor of psychiatry at the Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research at Columbia University, New York, has written extensively about human sexuality, gender-conversion therapies, and gender.

The study by Dr. Ganna and associates as a whole invalidates several commonly used sexual behavior scales, including the Kinsey Scale, which is solely predicated upon self-reported attraction. The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which measures sexual behavior, fantasies, and sexual identification, is similarly problematic, the authors noted.

“Overall, our findings suggest that the most popular measures are based on a misconception of the underlying structure of sexual orientation and may need to be rethought. In particular, using separate measures of attraction to the opposite sex and attraction to the same sex, such as in the Sell Assessment of Sexual Orientation, would remove the assumption that these variables are perfectly inversely related and would enable more nuanced exploration of the full diversity of sexual orientation, including bisexuality and asexuality,” they wrote.

During the telebriefing discussion, Dr. Neale said the study supports the nuances in sexuality espoused by self-identified sexual orientation communities. “I think those things that we’ve learned include the idea that there is more diversity out there in the world. We see that diversity in the genetic analysis. And we reinforce that sort of message that the expanding acronyms in the LGBTQIA+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other] is justified.”

The study “underscores that there is an element of biology and it underscores that there’s an element of the environment,” he said. “And it underscores that this is a natural part of our species and so these are the things that both matter and there’s no way to get away from that idea.”

Several entities funded the study, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Ganna reported no financial conflicts. Two of the researchers and members of the 23andMe research team are 23andMe employees or hold stock options in the company. Another researcher is affiliated with Deep Genomics as a member of its scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: Ganna A et al. Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aat769.

A large study that reliably shows a genetic component to nonheterosexuality could have far-reaching societal and legal impact, Melinda C. Mills, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aay2726).

“Studies have indicated that same-sex orientation and behavior has a genetic basis and runs in families, yet specific genetic variants have not been isolated,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Evidence that sexual orientation has a biological component could shape acceptance and legal protection: 4%-10% of individuals report ever engaging in same-sex behavior in the United States, so this could affect a sizable proportion of the population.”

The half-million subject genome-wide association study by Ganna et al. could go a long way toward achieving that goal – much farther than prior studies, all of which were smaller and unreplicated.

“The genetic basis of same-sex orientation and sexual behavior has evaded discovery, largely because of the challenges of using small and nonrepresentative cohorts,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Initial evidence focused mostly on gay men, providing indirect and often speculative evidence of a relationship with fraternal birth order, prenatal exposure to sex hormones, neurodevelopmental traits, or maternal immunization to sex-specific proteins. Work in the 1990s isolated a relationship with the Xq28 region on the X chromosome. Subsequent studies found similarity in the sexual orientation of identical twins, with genetics explaining 18% (for women) and 37% (for men), with the remainder accounted for by directly shared environments (such as family or school) and nonshared environments (such as legalization or norms regarding same-sex behavior).”

Despite these findings, and others hinting at a heritable genetic cause, specific variants have not been identified – until now. The finding of five predictive genes, including two specific to males and one specific to females, is novel and exciting.

Attributing same-sex orientation to genetics could enhance civil rights or reduce stigma, she wrote. “Conversely, there are fears it provides a tool for intervention or ‘cure.’ Same-sex orientation has been classified as pathological and illegal, and remains criminalized in more than 70 countries, some with the death penalty.”

By calculating the overall potential genetic contribution of 8%-25% along with the identification of specific genetic loci, Ganna et al. showed “the potential magnitude of genetic effects that we may eventually measure and a sign that complex behaviors continue to have small, likely polygenic, influences.”

Dr. Mills is the Nuffield Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford (England). She had no relevant financial disclosures.

A large study that reliably shows a genetic component to nonheterosexuality could have far-reaching societal and legal impact, Melinda C. Mills, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aay2726).

“Studies have indicated that same-sex orientation and behavior has a genetic basis and runs in families, yet specific genetic variants have not been isolated,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Evidence that sexual orientation has a biological component could shape acceptance and legal protection: 4%-10% of individuals report ever engaging in same-sex behavior in the United States, so this could affect a sizable proportion of the population.”

The half-million subject genome-wide association study by Ganna et al. could go a long way toward achieving that goal – much farther than prior studies, all of which were smaller and unreplicated.

“The genetic basis of same-sex orientation and sexual behavior has evaded discovery, largely because of the challenges of using small and nonrepresentative cohorts,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Initial evidence focused mostly on gay men, providing indirect and often speculative evidence of a relationship with fraternal birth order, prenatal exposure to sex hormones, neurodevelopmental traits, or maternal immunization to sex-specific proteins. Work in the 1990s isolated a relationship with the Xq28 region on the X chromosome. Subsequent studies found similarity in the sexual orientation of identical twins, with genetics explaining 18% (for women) and 37% (for men), with the remainder accounted for by directly shared environments (such as family or school) and nonshared environments (such as legalization or norms regarding same-sex behavior).”

Despite these findings, and others hinting at a heritable genetic cause, specific variants have not been identified – until now. The finding of five predictive genes, including two specific to males and one specific to females, is novel and exciting.

Attributing same-sex orientation to genetics could enhance civil rights or reduce stigma, she wrote. “Conversely, there are fears it provides a tool for intervention or ‘cure.’ Same-sex orientation has been classified as pathological and illegal, and remains criminalized in more than 70 countries, some with the death penalty.”

By calculating the overall potential genetic contribution of 8%-25% along with the identification of specific genetic loci, Ganna et al. showed “the potential magnitude of genetic effects that we may eventually measure and a sign that complex behaviors continue to have small, likely polygenic, influences.”

Dr. Mills is the Nuffield Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford (England). She had no relevant financial disclosures.

A large study that reliably shows a genetic component to nonheterosexuality could have far-reaching societal and legal impact, Melinda C. Mills, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aay2726).

“Studies have indicated that same-sex orientation and behavior has a genetic basis and runs in families, yet specific genetic variants have not been isolated,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Evidence that sexual orientation has a biological component could shape acceptance and legal protection: 4%-10% of individuals report ever engaging in same-sex behavior in the United States, so this could affect a sizable proportion of the population.”

The half-million subject genome-wide association study by Ganna et al. could go a long way toward achieving that goal – much farther than prior studies, all of which were smaller and unreplicated.

“The genetic basis of same-sex orientation and sexual behavior has evaded discovery, largely because of the challenges of using small and nonrepresentative cohorts,” Dr. Mills wrote. “Initial evidence focused mostly on gay men, providing indirect and often speculative evidence of a relationship with fraternal birth order, prenatal exposure to sex hormones, neurodevelopmental traits, or maternal immunization to sex-specific proteins. Work in the 1990s isolated a relationship with the Xq28 region on the X chromosome. Subsequent studies found similarity in the sexual orientation of identical twins, with genetics explaining 18% (for women) and 37% (for men), with the remainder accounted for by directly shared environments (such as family or school) and nonshared environments (such as legalization or norms regarding same-sex behavior).”

Despite these findings, and others hinting at a heritable genetic cause, specific variants have not been identified – until now. The finding of five predictive genes, including two specific to males and one specific to females, is novel and exciting.

Attributing same-sex orientation to genetics could enhance civil rights or reduce stigma, she wrote. “Conversely, there are fears it provides a tool for intervention or ‘cure.’ Same-sex orientation has been classified as pathological and illegal, and remains criminalized in more than 70 countries, some with the death penalty.”

By calculating the overall potential genetic contribution of 8%-25% along with the identification of specific genetic loci, Ganna et al. showed “the potential magnitude of genetic effects that we may eventually measure and a sign that complex behaviors continue to have small, likely polygenic, influences.”

Dr. Mills is the Nuffield Professor of Sociology at the University of Oxford (England). She had no relevant financial disclosures.

There is no single “gay gene.”

There are, however, signals that nonheterosexual behavior has at least some genetic component, according to Andrea Ganna, PhD, and colleagues.

Five candidate genes found in a half-million subject genetic study each account for less than 1% of the variance in same-sex sexual behavior, the scientists found. Over the entire genome, genetic variants accounted for less than a quarter of such behavior.

None of the genetic signals can reliably predict sexual behavior, Benjamin Neale, PhD, director of genetics in the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in a telebriefing that included Dr. Ganna, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab. Instead, the variability of human sexuality is an entirely natural continuum of human behavior.

“Whether we are attracted exclusively to the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes falls along a spectrum that is an integral, and entirely normal, part of the human experience,” said Dr. Neale. “The choice of a sexual partner and the fraction of partners that are of the same sex are all consistent with this diversity being a key feature of our sexual behavior as a species and this diversity is a natural part of being human.”

The study, published in Science, clarifies findings of smaller, previous studies, which determined that sexual behavior is a combination of genetics and environment – although environment is a much more difficult association to assess.

“[Environment] can range from anything in utero, all the way all the way through who you happen to stand next to on the tube in the morning, right? That’s all potentially environmental factors that can have some influence on complex traits and so we don’t really understand,” Dr. Neale said.

However, he added, the concept of individual choice in sexual behaviors was beyond the scope of the study, which strictly centered on genetic associations with sexual behavior.

The study combined genetic information from three extant databases (the U.K. Biobank, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation, and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden) with newly collected data from 23andMe, the technology company that provides at-home genetics tests largely used to determine ethnic origin.

The primary phenotype investigated was a binary measure: self-reported sexual behavior with someone of the same sex (nonheterosexuality) or someone of the opposite sex (heterosexuality).

“The binary variable also collapses rich and multifaceted diversity among nonheterosexuality individuals, wrote Dr. Ganna and his coauthors. Therefore, “we explored finer-scaled measurements and some of the complexities of the phenotype, although intricacies of the social and cultural influences on sexuality made it impossible to fully explore this complexity.”

The team also performed replication analyses on three smaller datasets: the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation (2,308 U.S. adult males), Add Health (4,755 U.S. young adults), and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (8,093 Swedish adolescents). Data were available for 188,825 males and 220,170 females overall. When broken down by sexual behavior, data were available for 1,766 homosexual and 180,431 heterosexual males, and 693 homosexual and 214,062 heterosexual females.

The team identified two genes that significantly predicted same-sex sexual behavior (rs11114975-12q21.31 and rs10261857-7q31.2). Two more genes predicted same-sex sexual behavior in males only (rs28371400-15q21.3 and rs34730029-11q12.1), and one additional gene predicted the behavior in females only (rs13135637-4p14).

Three of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally replicated those in some of the other datasets, despite the much smaller sample sizes.

“The SNPs that reached genome-wide significance had very small effects (odds ratio, 1.1),” the authors wrote. “For example, in the U.K. Biobank, males with a GT genotype at the rs34730029 locus had 0.4% higher prevalence of same-sex sexual behavior than those with a TT genotype. Nevertheless, the contribution of all measured common SNPs in aggregate was estimated to [account for] 8%-25% of variation in female and male same-sex sexual behavior. … The discrepancy between the variance captured by the significant SNPs and all common SNPs suggests that same-sex sexual behavior, like most complex human traits, is influenced by the small, additive effects of very many genetic variants, most of which cannot be detected at the current sample size.”

The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden contained the youngest subjects. The polygenic scores in this dataset were significantly associated with sexual attraction at age 15 years, “suggesting that at least some of the genetic influences on same-sex sexual behavior manifest early in sexual development.”

The team also investigated the biological pathways associated with the SNPs. Among the male variants, rs34730029-11q12.1 contains numerous olfactory receptor genes.

“Second, rs28371400-15q21.3 had several indications of being involved in sex hormone regulation. The allele positively associated with same-sex sexual behavior is associated with higher rate of male pattern balding, in which sex-hormone sensitivity is implicated,” they wrote.

This is located near the TCF12 gene, related to a normal gonadal development in mice.

Among women, there were inverse associations with the level of sex hormone–binding globulin, which regulates the balance between testosterone and estrogen.

There were significant associations with some mental health traits, including loneliness, openness to experience, and risky behaviors such as smoking and using cannabis. There were also associations with depression and schizophrenia. The genetic correlations for bipolar disorder, cannabis use, and number of sexual partners were significantly higher in females than in males.

“We emphasize that the causal processes underlying these genetic correlations are unclear and could be generated by environmental factors relating to prejudice against individuals engaging in same-sex sexual behavior,” the authors wrote.

In an interview, Jack Drescher, MD, said he was not surprised by the findings and cited the results a twin study by J. Michael Bailey, PhD, and Richard C. Pillard, MD, as evidence of the complexities surrounding sexual orientation. The study examined the likelihood of one twin having a gay twin (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Dec;48[12]:1089-96).

“If you were a gay identical twin, you had a 52% chance of having a gay twin, he said. “If you were a gay fraternal twin, you only had a 22% chance of having a gay twin. The chance of an adoptive brother being gay was 11%. If homosexuality were simply a result of simple genetic transmission, then one would expect closer to 100% gay identical twins, since they both have the same genes.”

Dr. Drescher, clinical professor of psychiatry at the Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research at Columbia University, New York, has written extensively about human sexuality, gender-conversion therapies, and gender.

The study by Dr. Ganna and associates as a whole invalidates several commonly used sexual behavior scales, including the Kinsey Scale, which is solely predicated upon self-reported attraction. The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which measures sexual behavior, fantasies, and sexual identification, is similarly problematic, the authors noted.

“Overall, our findings suggest that the most popular measures are based on a misconception of the underlying structure of sexual orientation and may need to be rethought. In particular, using separate measures of attraction to the opposite sex and attraction to the same sex, such as in the Sell Assessment of Sexual Orientation, would remove the assumption that these variables are perfectly inversely related and would enable more nuanced exploration of the full diversity of sexual orientation, including bisexuality and asexuality,” they wrote.

During the telebriefing discussion, Dr. Neale said the study supports the nuances in sexuality espoused by self-identified sexual orientation communities. “I think those things that we’ve learned include the idea that there is more diversity out there in the world. We see that diversity in the genetic analysis. And we reinforce that sort of message that the expanding acronyms in the LGBTQIA+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other] is justified.”

The study “underscores that there is an element of biology and it underscores that there’s an element of the environment,” he said. “And it underscores that this is a natural part of our species and so these are the things that both matter and there’s no way to get away from that idea.”

Several entities funded the study, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Ganna reported no financial conflicts. Two of the researchers and members of the 23andMe research team are 23andMe employees or hold stock options in the company. Another researcher is affiliated with Deep Genomics as a member of its scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: Ganna A et al. Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aat769.

There is no single “gay gene.”

There are, however, signals that nonheterosexual behavior has at least some genetic component, according to Andrea Ganna, PhD, and colleagues.

Five candidate genes found in a half-million subject genetic study each account for less than 1% of the variance in same-sex sexual behavior, the scientists found. Over the entire genome, genetic variants accounted for less than a quarter of such behavior.

None of the genetic signals can reliably predict sexual behavior, Benjamin Neale, PhD, director of genetics in the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said in a telebriefing that included Dr. Ganna, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab. Instead, the variability of human sexuality is an entirely natural continuum of human behavior.

“Whether we are attracted exclusively to the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes falls along a spectrum that is an integral, and entirely normal, part of the human experience,” said Dr. Neale. “The choice of a sexual partner and the fraction of partners that are of the same sex are all consistent with this diversity being a key feature of our sexual behavior as a species and this diversity is a natural part of being human.”

The study, published in Science, clarifies findings of smaller, previous studies, which determined that sexual behavior is a combination of genetics and environment – although environment is a much more difficult association to assess.

“[Environment] can range from anything in utero, all the way all the way through who you happen to stand next to on the tube in the morning, right? That’s all potentially environmental factors that can have some influence on complex traits and so we don’t really understand,” Dr. Neale said.

However, he added, the concept of individual choice in sexual behaviors was beyond the scope of the study, which strictly centered on genetic associations with sexual behavior.

The study combined genetic information from three extant databases (the U.K. Biobank, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation, and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden) with newly collected data from 23andMe, the technology company that provides at-home genetics tests largely used to determine ethnic origin.

The primary phenotype investigated was a binary measure: self-reported sexual behavior with someone of the same sex (nonheterosexuality) or someone of the opposite sex (heterosexuality).

“The binary variable also collapses rich and multifaceted diversity among nonheterosexuality individuals, wrote Dr. Ganna and his coauthors. Therefore, “we explored finer-scaled measurements and some of the complexities of the phenotype, although intricacies of the social and cultural influences on sexuality made it impossible to fully explore this complexity.”

The team also performed replication analyses on three smaller datasets: the Molecular Genetic Study of Sexual Orientation (2,308 U.S. adult males), Add Health (4,755 U.S. young adults), and the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (8,093 Swedish adolescents). Data were available for 188,825 males and 220,170 females overall. When broken down by sexual behavior, data were available for 1,766 homosexual and 180,431 heterosexual males, and 693 homosexual and 214,062 heterosexual females.

The team identified two genes that significantly predicted same-sex sexual behavior (rs11114975-12q21.31 and rs10261857-7q31.2). Two more genes predicted same-sex sexual behavior in males only (rs28371400-15q21.3 and rs34730029-11q12.1), and one additional gene predicted the behavior in females only (rs13135637-4p14).

Three of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) nominally replicated those in some of the other datasets, despite the much smaller sample sizes.

“The SNPs that reached genome-wide significance had very small effects (odds ratio, 1.1),” the authors wrote. “For example, in the U.K. Biobank, males with a GT genotype at the rs34730029 locus had 0.4% higher prevalence of same-sex sexual behavior than those with a TT genotype. Nevertheless, the contribution of all measured common SNPs in aggregate was estimated to [account for] 8%-25% of variation in female and male same-sex sexual behavior. … The discrepancy between the variance captured by the significant SNPs and all common SNPs suggests that same-sex sexual behavior, like most complex human traits, is influenced by the small, additive effects of very many genetic variants, most of which cannot be detected at the current sample size.”

The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden contained the youngest subjects. The polygenic scores in this dataset were significantly associated with sexual attraction at age 15 years, “suggesting that at least some of the genetic influences on same-sex sexual behavior manifest early in sexual development.”

The team also investigated the biological pathways associated with the SNPs. Among the male variants, rs34730029-11q12.1 contains numerous olfactory receptor genes.

“Second, rs28371400-15q21.3 had several indications of being involved in sex hormone regulation. The allele positively associated with same-sex sexual behavior is associated with higher rate of male pattern balding, in which sex-hormone sensitivity is implicated,” they wrote.

This is located near the TCF12 gene, related to a normal gonadal development in mice.

Among women, there were inverse associations with the level of sex hormone–binding globulin, which regulates the balance between testosterone and estrogen.

There were significant associations with some mental health traits, including loneliness, openness to experience, and risky behaviors such as smoking and using cannabis. There were also associations with depression and schizophrenia. The genetic correlations for bipolar disorder, cannabis use, and number of sexual partners were significantly higher in females than in males.

“We emphasize that the causal processes underlying these genetic correlations are unclear and could be generated by environmental factors relating to prejudice against individuals engaging in same-sex sexual behavior,” the authors wrote.

In an interview, Jack Drescher, MD, said he was not surprised by the findings and cited the results a twin study by J. Michael Bailey, PhD, and Richard C. Pillard, MD, as evidence of the complexities surrounding sexual orientation. The study examined the likelihood of one twin having a gay twin (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Dec;48[12]:1089-96).

“If you were a gay identical twin, you had a 52% chance of having a gay twin, he said. “If you were a gay fraternal twin, you only had a 22% chance of having a gay twin. The chance of an adoptive brother being gay was 11%. If homosexuality were simply a result of simple genetic transmission, then one would expect closer to 100% gay identical twins, since they both have the same genes.”

Dr. Drescher, clinical professor of psychiatry at the Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research at Columbia University, New York, has written extensively about human sexuality, gender-conversion therapies, and gender.

The study by Dr. Ganna and associates as a whole invalidates several commonly used sexual behavior scales, including the Kinsey Scale, which is solely predicated upon self-reported attraction. The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which measures sexual behavior, fantasies, and sexual identification, is similarly problematic, the authors noted.

“Overall, our findings suggest that the most popular measures are based on a misconception of the underlying structure of sexual orientation and may need to be rethought. In particular, using separate measures of attraction to the opposite sex and attraction to the same sex, such as in the Sell Assessment of Sexual Orientation, would remove the assumption that these variables are perfectly inversely related and would enable more nuanced exploration of the full diversity of sexual orientation, including bisexuality and asexuality,” they wrote.

During the telebriefing discussion, Dr. Neale said the study supports the nuances in sexuality espoused by self-identified sexual orientation communities. “I think those things that we’ve learned include the idea that there is more diversity out there in the world. We see that diversity in the genetic analysis. And we reinforce that sort of message that the expanding acronyms in the LGBTQIA+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other] is justified.”

The study “underscores that there is an element of biology and it underscores that there’s an element of the environment,” he said. “And it underscores that this is a natural part of our species and so these are the things that both matter and there’s no way to get away from that idea.”

Several entities funded the study, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Ganna reported no financial conflicts. Two of the researchers and members of the 23andMe research team are 23andMe employees or hold stock options in the company. Another researcher is affiliated with Deep Genomics as a member of its scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: Ganna A et al. Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aat769.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: Genetic variants do appear to contribute to same-sex sexual behaviors.

Major finding: Five single nucleotide polymorphisms each account for about 1% of the variability in sexual behavior, while across a large population, genetic variants account for 8%-25% of the variation.

Study details: The genome-wide association study was made up of about 500,000 subjects.

Disclosures: The study was funded by several entities, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Ganna reported no financial conflicts. Two of the researchers and members of the 23andMe research team are 23andMe employees or hold stock options in the company. Another researcher is affiliated with Deep Genomics as a member of its scientific advisory board.

Source: Ganna A et al. Science. 2019 Aug 30. doi: 10.1126/science.aat769.

HIV drug may enhance efficacy of chemoradiation in locally advanced lung cancer

Administering an HIV drug concurrently with chemoradiotherapy resulted in promising local control and overall survival in patients with unresectable, locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, researchers reported.

There was no overt exacerbation of the toxic effects of chemoradiotherapy with the addition of nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor, in the prospective, open-label, phase 1/2 study, the researchers wrote.

Nelfinavir plus chemoradiotherapy yielded a median progression-free survival of 11.7 months and median survival of 41.1 months, while the cumulative local failure incidence was 39% according to their report.

Those outcomes compare favorably with historical data, the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In benchmark results of the RTOG 0617 study of chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, median overall survival was 28.7 months receiving radiotherapy at a standard dose of 60 Gy, and 20.3 months for those receiving high-dose (74 Gy) radiotherapy.

However, a randomized, phase 3 trial is needed to confirm these latest results with a protease inhibitor added to chemotherapy, according to Ramesh Rengan, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coinvestigators.

“As nelfinavir is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved oral drug, this treatment approach is feasible and is potentially a readily exportable platform for daily clinical use,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that nelfinavir inhibited PI3K and Akt signaling, sensitized tumor cells to ionizing radiation, and improved tumor perfusion in animal models. “We hypothesize that it is these properties that drive the clinical results observed in this study,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

They reported on a total of 35 patients with stage IIIA/IIIB non–small cell lung cancer who received nelfinavir at either 625 mg or 1,250 mg twice daily, starting 7-14 days before starting radiotherapy to 66.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, and throughout the full course of radiotherapy.

There were no dose-limiting toxic effects observed in the study, and toxic effects were “acceptable,” with no grade 4 nonhematologic toxic effects seen, according to investigators. Leukopenia was the primary grade 3-4 hematologic toxic effect, observed in 2 of 5 patients receiving the lower nelfinavir dose and 18 of 30 at the higher dose.

Beyond non–small cell lung cancer, the efficacy and safety nelfinavir given concurrently with radiotherapy has been looked at in other disease settings. Data from those trials suggest that this protease inhibitor could “augment tumor response” not only in non–small cell lung cancer, but in locally advanced pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma, all of which are relatively radioresistant, according to Dr. Rengan and colleagues.

Study support came from grants from the National Institutes of Health and Abramson Cancer Center, and an American Society for Radiation Oncology training award to Dr. Rengan. Study authors reported disclosures related to Pfizer, 511 Pharma, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Siemens, Actinium, AstraZeneca, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and others.

SOURCE: Rengan R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2095.

Administering an HIV drug concurrently with chemoradiotherapy resulted in promising local control and overall survival in patients with unresectable, locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, researchers reported.

There was no overt exacerbation of the toxic effects of chemoradiotherapy with the addition of nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor, in the prospective, open-label, phase 1/2 study, the researchers wrote.

Nelfinavir plus chemoradiotherapy yielded a median progression-free survival of 11.7 months and median survival of 41.1 months, while the cumulative local failure incidence was 39% according to their report.

Those outcomes compare favorably with historical data, the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In benchmark results of the RTOG 0617 study of chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, median overall survival was 28.7 months receiving radiotherapy at a standard dose of 60 Gy, and 20.3 months for those receiving high-dose (74 Gy) radiotherapy.

However, a randomized, phase 3 trial is needed to confirm these latest results with a protease inhibitor added to chemotherapy, according to Ramesh Rengan, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coinvestigators.

“As nelfinavir is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved oral drug, this treatment approach is feasible and is potentially a readily exportable platform for daily clinical use,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that nelfinavir inhibited PI3K and Akt signaling, sensitized tumor cells to ionizing radiation, and improved tumor perfusion in animal models. “We hypothesize that it is these properties that drive the clinical results observed in this study,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

They reported on a total of 35 patients with stage IIIA/IIIB non–small cell lung cancer who received nelfinavir at either 625 mg or 1,250 mg twice daily, starting 7-14 days before starting radiotherapy to 66.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, and throughout the full course of radiotherapy.

There were no dose-limiting toxic effects observed in the study, and toxic effects were “acceptable,” with no grade 4 nonhematologic toxic effects seen, according to investigators. Leukopenia was the primary grade 3-4 hematologic toxic effect, observed in 2 of 5 patients receiving the lower nelfinavir dose and 18 of 30 at the higher dose.

Beyond non–small cell lung cancer, the efficacy and safety nelfinavir given concurrently with radiotherapy has been looked at in other disease settings. Data from those trials suggest that this protease inhibitor could “augment tumor response” not only in non–small cell lung cancer, but in locally advanced pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma, all of which are relatively radioresistant, according to Dr. Rengan and colleagues.

Study support came from grants from the National Institutes of Health and Abramson Cancer Center, and an American Society for Radiation Oncology training award to Dr. Rengan. Study authors reported disclosures related to Pfizer, 511 Pharma, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Siemens, Actinium, AstraZeneca, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and others.

SOURCE: Rengan R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2095.

Administering an HIV drug concurrently with chemoradiotherapy resulted in promising local control and overall survival in patients with unresectable, locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, researchers reported.

There was no overt exacerbation of the toxic effects of chemoradiotherapy with the addition of nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor, in the prospective, open-label, phase 1/2 study, the researchers wrote.

Nelfinavir plus chemoradiotherapy yielded a median progression-free survival of 11.7 months and median survival of 41.1 months, while the cumulative local failure incidence was 39% according to their report.

Those outcomes compare favorably with historical data, the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In benchmark results of the RTOG 0617 study of chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer, median overall survival was 28.7 months receiving radiotherapy at a standard dose of 60 Gy, and 20.3 months for those receiving high-dose (74 Gy) radiotherapy.

However, a randomized, phase 3 trial is needed to confirm these latest results with a protease inhibitor added to chemotherapy, according to Ramesh Rengan, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coinvestigators.

“As nelfinavir is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved oral drug, this treatment approach is feasible and is potentially a readily exportable platform for daily clinical use,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that nelfinavir inhibited PI3K and Akt signaling, sensitized tumor cells to ionizing radiation, and improved tumor perfusion in animal models. “We hypothesize that it is these properties that drive the clinical results observed in this study,” Dr. Rengan and coauthors wrote.

They reported on a total of 35 patients with stage IIIA/IIIB non–small cell lung cancer who received nelfinavir at either 625 mg or 1,250 mg twice daily, starting 7-14 days before starting radiotherapy to 66.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, and throughout the full course of radiotherapy.

There were no dose-limiting toxic effects observed in the study, and toxic effects were “acceptable,” with no grade 4 nonhematologic toxic effects seen, according to investigators. Leukopenia was the primary grade 3-4 hematologic toxic effect, observed in 2 of 5 patients receiving the lower nelfinavir dose and 18 of 30 at the higher dose.

Beyond non–small cell lung cancer, the efficacy and safety nelfinavir given concurrently with radiotherapy has been looked at in other disease settings. Data from those trials suggest that this protease inhibitor could “augment tumor response” not only in non–small cell lung cancer, but in locally advanced pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma, all of which are relatively radioresistant, according to Dr. Rengan and colleagues.

Study support came from grants from the National Institutes of Health and Abramson Cancer Center, and an American Society for Radiation Oncology training award to Dr. Rengan. Study authors reported disclosures related to Pfizer, 511 Pharma, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Siemens, Actinium, AstraZeneca, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and others.

SOURCE: Rengan R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2095.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

FGF21 could be tied to psychopathology of bipolar mania

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Patients’ fibroblast growth factor–21 levels dropped after 4 weeks of taking antipsychotics

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

Fibroblast growth factor–21 (FGF21), a protein that regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, could be a biomarker in patients with bipolar mania, a new study suggests.

“In addition, our data indicates that FGF21 may monitor and/or prevent metabolic abnormalities induced by psychotropic drugs,” wrote Qing Hu of Xiamen City Xianyue Hospital, in Fujian, China, and associates. The study was published in Psychiatry Research.

To investigate how the expression of FGF21 changes in response to psychotropics taken by patients with bipolar mania, the researchers recruited 99 inpatients with bipolar mania with or without psychosis and 99 healthy controls. Eighty-two of the patients received psychotropics only, and 17 received psychotropics and lipid-lowering or hypotensive agents. Those in the smaller group were later excluded from follow-up.

At baseline, no significant differences were found between the patients and controls on several metabolic measures, such as cholesterol and apolipoprotein. The patients with bipolar mania had higher uric acid and triglyceride levels, although the latter was not statistically significant. However, compared with the FGF21 serum levels of the controls.

After 4 weeks of taking the antipsychotics, the patients experienced increases in several metabolic measures, such as BMI (23.68 kg/m2 vs. 24.02 kg/m2), LDL cholesterol (2.61 mg/dL vs. 2.98 mg/dL), and glucose (4.74 mg/dL vs. 4.88 mg/dL). However, their FGF21 levels declined, from 279.45 pg/mL to 215.12 pg/mL.

“In light of these findings, our future research will focus on investigating whether ... the change in FGF21 expression is a causal factor or a consequence of bipolar disorder,” the investigators wrote.

They cited several limitations. One is that psychotropic dosages were not discussed, and another is that evaluation data from the Young Mania Rating Scale were missing.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hu Q et al. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:643-8.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

Additional physical therapy decreases length of stay

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The optimal quantity of physical therapy provided to hospitalized patients is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the costs of additional physical therapy might be outweighed by a decrease in length of stay. A prior meta-analysis done by the same authors was inconclusive; subsequently, additional large trials were published, prompting the authors to repeat their meta-analysis.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Literature review of English-language studies conducted worldwide.

Synopsis: A total of 24 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3,262 participants was included in this meta-analysis. The primary finding was that additional physical therapy was associated with a 3-day reduction in length of stay in subacute settings (95% confidence interval, –4.6 to –0.9) and a 0.6-day reduction in acute care settings (95% CI, –1.1 to 0.0). Furthermore, additional physical therapy was associated with small improvements in self-care and activities of daily living. One trial included an economic analysis that suggested additional physical therapy was cost effective.

Of note, there was no standard definition of “additional physical therapy” across the heterogeneous group of trials analyzed in this meta-analysis. In all studies, the experimental group received more physical therapy than the control group, either by increased frequency or duration of sessions. Nonetheless, hospitals may consider increasing physical therapy services as a cost-effective means of reducing length of stay.

Bottom line: Additional physical therapy in acute and subacute care settings results in a decreased length of stay and may be cost effective.

Citation: Peiris CL et al. Additional physical therapy services reduce length of stay and improve health outcomes in people with acute and subacute conditions: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2018;99(11):2299-312.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

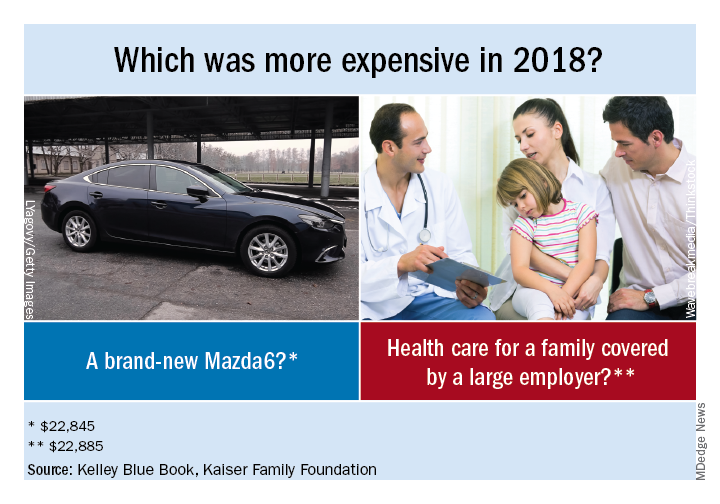

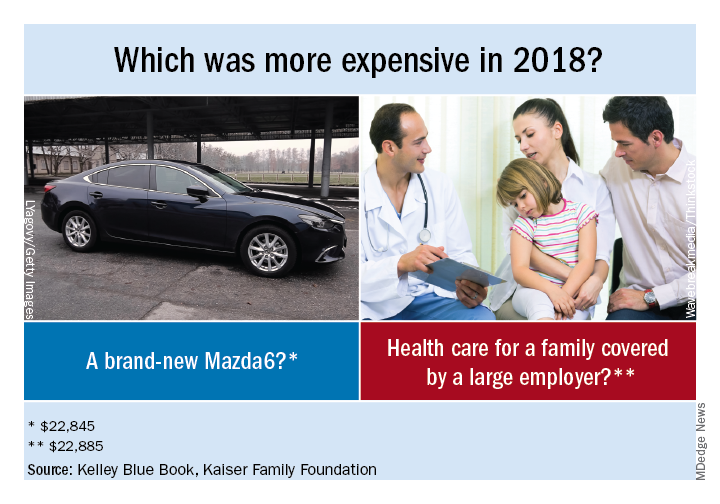

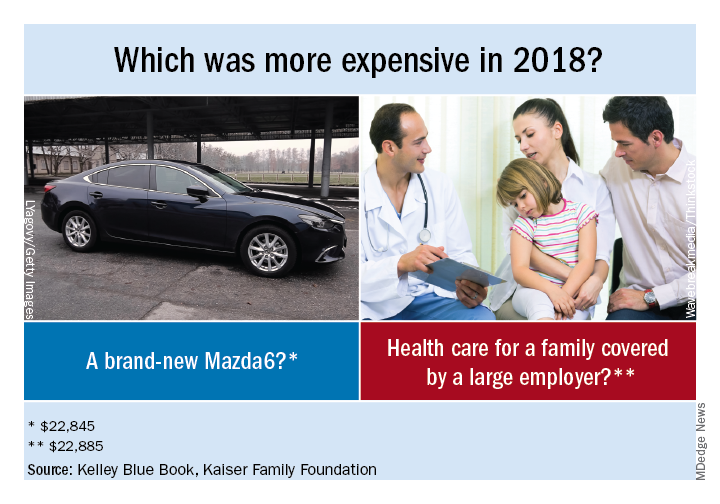

Health spending nears $23,000 per family

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

That average cost represents the employer’s contribution to the insurance premium ($15,159), along with the employee’s premium ($4,706) and the family’s out-of-pocket spending ($3,020), according to a KFF analysis of IBM MarketScan data and the 2018 KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey.

“Buying a new car every year would be a very impractical expense. It would also be cheaper than a year’s worth of health care for a family,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman, PhD, wrote in his Axios column.

A little searching on the Kelley Blue Book Car Finder shows that the average family could have purchased a pretty nice new vehicle for the $22,885 that was spent on their health care in 2018:

- Mazda6 sedan: $22,845.

- Mini 2-door hatchback: $22,450.

- Jeep Renegade SUV: $21,040.

- Nissan Frontier king cab pickup: $20,035.

“The cost-shifting and complexity of health insurance can hide its high cost, which crowds out families’ other needs and depresses workers’ wages,” Dr. Altman said.

Molecular profiling a must in advanced NSCLC

All patients with locally advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) should undergo molecular testing for targetable mutations and for tumor expression of the programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) protein, authors of a review of systemic therapies for NSCLC recommend.

Their opinion is based on evidence showing that 5-year overall survival rate for patients whose tumors have high levels of PD-L1 expression now exceeds 25%, and that patients with ALK-positive tumors have 5-year overall survival rates over 40%. In contrast, 5-year survival rates for patients with metastatic NSCLC prior to the 21st century were less than 5%, according to Kathryn C. Arbour, MD, and Gregory J. Riely, MD, PhD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Improved understanding of the biology and molecular subtypes of non–small cell lung cancer have led to more biomarker-directed therapies for patients with metastatic disease. These biomarker-directed therapies and newer empirical treatment regimens have improved overall survival for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer,” they wrote in JAMA.

The authors reviewed published studies of clinical trials of medical therapies for NSCLC, including articles on randomized trials, nonrandomized trials leading to practice changes or regulatory approval of new therapies for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, and clinical practice guidelines.

Their review showed that approximately 30% of patients with NSCLC have molecular alterations predictive of response to treatment, such as mutations in EGFR, the gene encoding for epidermal growth factor receptor; rearrangements in the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) and ROS1 genes; and mutations in BRAF V600E.

Patients with somatic activating mutations in EGFR, which occur in approximately 20% of those with advanced NSCLC, have better progression-free survival when treated with an EGFR-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor such as gefitinib (Iressa), erlotinib (Tarceva), or afatinib (Gilotrif), compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Similarly, they noted, patients with ALK rearrangements leading to overexpression of the ALK protein had better overall response rates and progression-free survival when treated with the ALK inhibitor crizotinib (Xalkori), compared with patients with ALK rearrangements treated with pemetrexed and a platinum agent.

For some patients without targetable mutations, immune checkpoint inhibitors either alone or in combination with chemotherapy have resulted in improvements in overall survival.

“These advances are substantial, but long-term durable responses remain uncommon for most patients. These insights into treating metastatic disease have informed the design of trials for new treatment strategies among patients with early-stage disease. The goal of NSCLC research is to understand and address mechanisms of resistant and refractory disease in patients with advanced disease and, ultimately, to increase cure rates,” the reviewers wrote.

The review was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering. Dr. Arbour reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and nonfinancial research support from Novartis and Takeda. Dr. Riely reported grants and nonfinancial support from Pfizer, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, Novartis, Merck, and Takeda; a patent pending for an alternate dosing of erlotinib for which he has no right to royalties; and payments from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to participate in a committee overseeing solicitation and selection of grants to be awarded by AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Arbour KC and Riely GJ. JAMA. 2019;322(8):764-74.

All patients with locally advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) should undergo molecular testing for targetable mutations and for tumor expression of the programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) protein, authors of a review of systemic therapies for NSCLC recommend.

Their opinion is based on evidence showing that 5-year overall survival rate for patients whose tumors have high levels of PD-L1 expression now exceeds 25%, and that patients with ALK-positive tumors have 5-year overall survival rates over 40%. In contrast, 5-year survival rates for patients with metastatic NSCLC prior to the 21st century were less than 5%, according to Kathryn C. Arbour, MD, and Gregory J. Riely, MD, PhD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Improved understanding of the biology and molecular subtypes of non–small cell lung cancer have led to more biomarker-directed therapies for patients with metastatic disease. These biomarker-directed therapies and newer empirical treatment regimens have improved overall survival for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer,” they wrote in JAMA.

The authors reviewed published studies of clinical trials of medical therapies for NSCLC, including articles on randomized trials, nonrandomized trials leading to practice changes or regulatory approval of new therapies for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, and clinical practice guidelines.

Their review showed that approximately 30% of patients with NSCLC have molecular alterations predictive of response to treatment, such as mutations in EGFR, the gene encoding for epidermal growth factor receptor; rearrangements in the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) and ROS1 genes; and mutations in BRAF V600E.

Patients with somatic activating mutations in EGFR, which occur in approximately 20% of those with advanced NSCLC, have better progression-free survival when treated with an EGFR-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor such as gefitinib (Iressa), erlotinib (Tarceva), or afatinib (Gilotrif), compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Similarly, they noted, patients with ALK rearrangements leading to overexpression of the ALK protein had better overall response rates and progression-free survival when treated with the ALK inhibitor crizotinib (Xalkori), compared with patients with ALK rearrangements treated with pemetrexed and a platinum agent.

For some patients without targetable mutations, immune checkpoint inhibitors either alone or in combination with chemotherapy have resulted in improvements in overall survival.

“These advances are substantial, but long-term durable responses remain uncommon for most patients. These insights into treating metastatic disease have informed the design of trials for new treatment strategies among patients with early-stage disease. The goal of NSCLC research is to understand and address mechanisms of resistant and refractory disease in patients with advanced disease and, ultimately, to increase cure rates,” the reviewers wrote.

The review was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering. Dr. Arbour reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and nonfinancial research support from Novartis and Takeda. Dr. Riely reported grants and nonfinancial support from Pfizer, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, Novartis, Merck, and Takeda; a patent pending for an alternate dosing of erlotinib for which he has no right to royalties; and payments from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to participate in a committee overseeing solicitation and selection of grants to be awarded by AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Arbour KC and Riely GJ. JAMA. 2019;322(8):764-74.

All patients with locally advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) should undergo molecular testing for targetable mutations and for tumor expression of the programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) protein, authors of a review of systemic therapies for NSCLC recommend.

Their opinion is based on evidence showing that 5-year overall survival rate for patients whose tumors have high levels of PD-L1 expression now exceeds 25%, and that patients with ALK-positive tumors have 5-year overall survival rates over 40%. In contrast, 5-year survival rates for patients with metastatic NSCLC prior to the 21st century were less than 5%, according to Kathryn C. Arbour, MD, and Gregory J. Riely, MD, PhD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“Improved understanding of the biology and molecular subtypes of non–small cell lung cancer have led to more biomarker-directed therapies for patients with metastatic disease. These biomarker-directed therapies and newer empirical treatment regimens have improved overall survival for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer,” they wrote in JAMA.

The authors reviewed published studies of clinical trials of medical therapies for NSCLC, including articles on randomized trials, nonrandomized trials leading to practice changes or regulatory approval of new therapies for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, and clinical practice guidelines.

Their review showed that approximately 30% of patients with NSCLC have molecular alterations predictive of response to treatment, such as mutations in EGFR, the gene encoding for epidermal growth factor receptor; rearrangements in the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) and ROS1 genes; and mutations in BRAF V600E.

Patients with somatic activating mutations in EGFR, which occur in approximately 20% of those with advanced NSCLC, have better progression-free survival when treated with an EGFR-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor such as gefitinib (Iressa), erlotinib (Tarceva), or afatinib (Gilotrif), compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Similarly, they noted, patients with ALK rearrangements leading to overexpression of the ALK protein had better overall response rates and progression-free survival when treated with the ALK inhibitor crizotinib (Xalkori), compared with patients with ALK rearrangements treated with pemetrexed and a platinum agent.

For some patients without targetable mutations, immune checkpoint inhibitors either alone or in combination with chemotherapy have resulted in improvements in overall survival.

“These advances are substantial, but long-term durable responses remain uncommon for most patients. These insights into treating metastatic disease have informed the design of trials for new treatment strategies among patients with early-stage disease. The goal of NSCLC research is to understand and address mechanisms of resistant and refractory disease in patients with advanced disease and, ultimately, to increase cure rates,” the reviewers wrote.

The review was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering. Dr. Arbour reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and nonfinancial research support from Novartis and Takeda. Dr. Riely reported grants and nonfinancial support from Pfizer, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, Novartis, Merck, and Takeda; a patent pending for an alternate dosing of erlotinib for which he has no right to royalties; and payments from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to participate in a committee overseeing solicitation and selection of grants to be awarded by AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Arbour KC and Riely GJ. JAMA. 2019;322(8):764-74.

FROM JAMA

Before the die is cast

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.

If I was going to spend my time and effort becoming a physician, I decided I wanted to be working with patients with the high potential for positive change and ones who had yet to accumulate a several decades long list of bad health habits. I wanted to be practicing in situations well before the die had been cast.

With this background in mind, you can understand why I was drawn to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette titled “Social spending on kids yields the biggest bang for the buck,” by Clea Simon. The article describes a recent study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute of policy analysts and social scientists (“A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies” by Nathaniel Hendren, PhD, and Ben Sprung-Keyser). Using computer algorithms capable of mining large pools of data, the researchers looked at 133 government policy changes over the last 50 years and compared the long-term results of those changes by assessing dollars spent against those returned in the form of tax revenue.

The Harvard article quotes Dr. Hendren as saying, This association was most impressive for children who came from lower-income families. This was especially true for programs that aimed at improving child health and increasing educational attainment.

Of course, these observations don’t come as a surprise to those of us who have accepted the challenge of improving the health of children. But it’s always nice to hear some new data that warms our hearts and reinforces our commitment to building healthy communities by focusing our efforts on its youngest members.

However, the paper did provide a finding that disappointed me. This big data analysis revealed that programs aimed at encouraging young people to attend college produced higher future earnings than did those focused on job training. I guess this shouldn’t be much of a surprise, but I believe we have been overemphasizing college track programs when we should be destigmatizing a career path in one of the trades. It may be that job training has been poorly done or at least not flexible enough to meet the changing demands of industry.

The investigators were surprised that their analysis demonstrated that policy changes targeted at children through their middle and high school years and even into college yielded return on investment at least as great if not greater than some successful preschool programs. Dr. Hendren responded to this finding by observing that “it’s never too late.” However, I think his comment deserves the loud and clear caveat, “as long as we are still talking about children.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

When asked about my decision to choose pediatrics over the other specialty opportunities I was being offered, I have always answered that my choice was primarily based on my desire to work with children. That affinity certainly didn’t stem from my experience with my sister who is 7 years my junior. By her own admission, she was a bratty little thing and a major annoyance during my journey through adolescence. However, during the summers of high school and college I worked as a lifeguard, and one of my duties was to teach swimming classes. The joy and reward of watching children overcome their fear of the water and become competent swimmers left a positive impression, which was in stark contrast to the few classes of adult nonswimmers my coworkers and I taught. Our success rate with adults was pretty close to zero.