User login

Reunion

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

We were catching up during our 35th college reunion at our old fraternity house overlooking Cayuga Lake in Ithaca, N.Y. About 50 of us lived in the Tudor-style house, complete with secret basement room, and there was a ladder that allowed access to the relatively flat, painted aluminum roof. When the weather allowed, we climbed the ladder to sun ourselves on top of the house. We also flung water balloons at unsuspecting pedestrians with a sling shot device made by attaching rubber tubing to a funnel. The “funnelator” was very accurate to about 50 yards away. We were kids, and climbing that ladder meant fun, and we climbed it as often as we could.

Despite what many would have predicted when we graduated, my fraternity brothers became a very successful group of CEOs, vice presidents, doctors, lawyers, chairmen, and consultants. Our house was just off Cornell University’s campus at the top of Ithaca Falls, an idyllic setting on a beautiful June evening for my brothers to sit around, laugh about the old times, and philosophize about life. We recounted our life after college and reveled in each others’ accomplishments.

After climbing the roof ladder for fun, we had each climbed a different kind of ladder to success in our respective fields. We all really enjoyed the climb. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of my brothers and I are now done climbing our ladders. Many of us are getting out of the rat race.

One of my friends is resigning as chairman of an academic ENT department. I remember his discipline in college, leaving the house after dinner every night to climb the hill where he studied in the quiet of Uris Library, which is attached to the iconic McGraw Tower. His hard work paid off with an acceptance to a prestigious medical school where he continued to excel. The author of more than 200 published manuscripts, with four senior-authored papers already this year, he is at the pinnacle of his academic success. Yet, he resigned.

Similarly, another of my fraternity brothers had recently resigned from his position as Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for a large health care system. He would have been in line for the CEO position had he stayed. He has written well-received books on leadership and financial acumen for physicians. As a result, he is a frequent public speaker on similar topics. Yet, he resigned.

They were not the only ones resigning positions that others covet. I, too, resigned my position as Department Chairman earlier this year. None of us were fired, none of us were asked to leave, and none of us are burned out. So here we were, three accomplished physicians all resigning from powerful posts at the same time for what turns out to be similar reasons. Our priorities changed as our children moved out.

I would like to say that we all had the wisdom to know that our leadership skills were deteriorating and that we all wanted to get out while we are at the top of our game. Had Arthur Brooks written “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” in The Atlantic (July 2019) before we made our decisions, I may have made that argument, but it would not have been true. All three of us feel like we have accomplished what we sought to achieve when we took our respective roles and now we wanted to leverage that experience into something different, if not better. None of us have settled into new roles yet, and all of us are still trying to define exactly what it is we want to do next, but all of us agree that we are no longer interested in driving ourselves to succeed at the expense of our family, friends, and relationships.

My fraternity brothers and I gushed with pride talking about our children and their success. Our progeny are starting their individual climbs up the ladder of opportunity in whatever field they have chosen. My friends and I, on the other hand, had already climbed a ladder and feel comfortable stopping. Or maybe we just want to start climbing a different ladder.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

Major Depressive Disorder: Unmet Needs and Innovative Treatments

Many of the unmet needs in major depressive disorder (MDD) are modifiable, including improving diagnostic accuracy and offering treatments with faster onset of action, treatments with greater overall efficacy, and treatments that can improve patient functioning.

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 CreditTM by learning about these unmet needs, and innovative strageies working to address them.

Topics include:

- Targeting Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

- Innovative Strategies for Treatments of Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Review of Recent Developments

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

- After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Treat major depression within 2 weeks.

- Use evidence based treatments to achieve remission in major depression.

- Discuss novel targets including glutamate for treating major depression.

- Utilize treatments with innovative mechanisms to treat major depression.

Click here to read the supplement.

Many of the unmet needs in major depressive disorder (MDD) are modifiable, including improving diagnostic accuracy and offering treatments with faster onset of action, treatments with greater overall efficacy, and treatments that can improve patient functioning.

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 CreditTM by learning about these unmet needs, and innovative strageies working to address them.

Topics include:

- Targeting Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

- Innovative Strategies for Treatments of Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Review of Recent Developments

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

- After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Treat major depression within 2 weeks.

- Use evidence based treatments to achieve remission in major depression.

- Discuss novel targets including glutamate for treating major depression.

- Utilize treatments with innovative mechanisms to treat major depression.

Click here to read the supplement.

Many of the unmet needs in major depressive disorder (MDD) are modifiable, including improving diagnostic accuracy and offering treatments with faster onset of action, treatments with greater overall efficacy, and treatments that can improve patient functioning.

Click here to read the supplement and earn 1 AMA Category 1 CreditTM by learning about these unmet needs, and innovative strageies working to address them.

Topics include:

- Targeting Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

- Innovative Strategies for Treatments of Major Depressive Disorder: A Brief Review of Recent Developments

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

- After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Treat major depression within 2 weeks.

- Use evidence based treatments to achieve remission in major depression.

- Discuss novel targets including glutamate for treating major depression.

- Utilize treatments with innovative mechanisms to treat major depression.

Click here to read the supplement.

The month of new beginnings is here

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

This month’s Letter from the Editor is guest authored by Dr. Megan A. Adams, GI & Hepatology News Associate Editor

September is a month of new beginnings, as summer transitions to fall, kids go back to school, and we return to more consistent work routines, refreshed and reinvigorated after some well-deserved time off with family and friends. Among our cover stories this month is a study showing a novel application of deep learning to inform clinical care of patients with pancreatic cysts. We also feature several high-impact studies from AGA’s journals, including a large randomized controlled trial by Dr. Paul Moayyedi and colleagues, demonstrating that PPI therapy may be unnecessary in the majority of patients on oral anticoagulants, despite current guideline recommendations. This study has the potential to substantially change clinical practice, particularly in the context of the current discussion regarding PPI benefits and harms, and our transition to value-based care.

We also highlight a proof-of-concept study demonstrating a potential role for probiotics (specifically Bifidobacteria) in reducing the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal bleeding, and another study showing a possible role for clopidogrel in chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Both articles are accompanied by expert commentaries highlighting their potential effect on clinical practice.

Our September issue also emphasizes the importance of professional advocacy by chronicling the participation of four AGA leaders (Dr. Carr, Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Ketwaroo, and Dr. Mathews) in the 2019 Alliance of Specialty Medicine Fly In, a multisociety effort to lobby legislators on key issues such as reducing prior authorization burdens and minimizing the strict constraints of step-therapy protocols. We also are pleased to acknowledge the future leaders of gastroenterology by recognizing the 17 exceptional fellows who demonstrated their passion for advancing GI clinical care by presenting their institutional quality improvement projects at a special session at DDW® 2019. We hope you find these stories to be thought provoking, inspiring, and directly relevant to your clinical practice – thank you for reading!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Associate Editor

Brexanolone injection for postpartum depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most prevalent complications associated with pregnancy and childbirth in the United States, affecting more than 400,000 women annually.1 Postpartum depression is most commonly treated with psychotherapy and antidepressants approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Until recently, there was no pharmacologic therapy approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of PPD. Considering the adverse outcomes associated with untreated or inadequately treated PPD, and the limitations of existing therapies, there is a significant unmet need for pharmacologic treatment options for PPD.2 To help address this need, the FDA recently approved brexanolone injection (brand name: ZULRESSO™) (Table 13) as a first-in-class therapy for the treatment of adults with PPD.3

Clinical implications

Postpartum depression can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when under- or untreated, and the need for rapid resolution of symptoms cannot be overstated.2 Suicide is strongly associated with depression and is a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths.4 Additionally, PPD can impact the health, safety, and well-being of the child, with both short- and long-term consequences, including greater rates of psychological or behavioral difficulties among children of patients with PPD.5 Postpartum depression can also have negative effects on the patient’s partner, with 24% to 50% of partners experiencing depression.6 Current PPD management strategies include the use of psychotherapy and pharmacologic interventions for major depressive disorder that may take up to 4 to 6 weeks for some patients, and may not achieve remission for all patients.7-9

Brexanolone injection is a first-in-class medication with a novel mechanism of action. In clinical studies, it achieved rapid (by Hour 60) and sustained (through Day 30) reductions in depressive symptoms and could provide a meaningful new treatment option for adult women with PPD.10,11

How it works

Animal and human studies have established the re

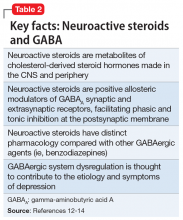

Brexanolone is a neuroactive steroid that is chemically identical to endogenous allopregnanolone produced in the CNS. Brexanolone potentiates GABA-mediated currents from recombinant human GABAARs in mammalian cells expressing α1β2γ2 receptor subunits, α4β3δ receptor subunits, and α6β3δ receptor subunits.3 Positive allosteric modulation of both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAARs differentiates brexanolone from other GABAAR modulators, such as benzodiazepines.10,11

Brexanolone’s mechanism of action in the treatment of PPD is not fully understood, but it is thought to be related to GABAAR PAM activity.3

Supporting evidence

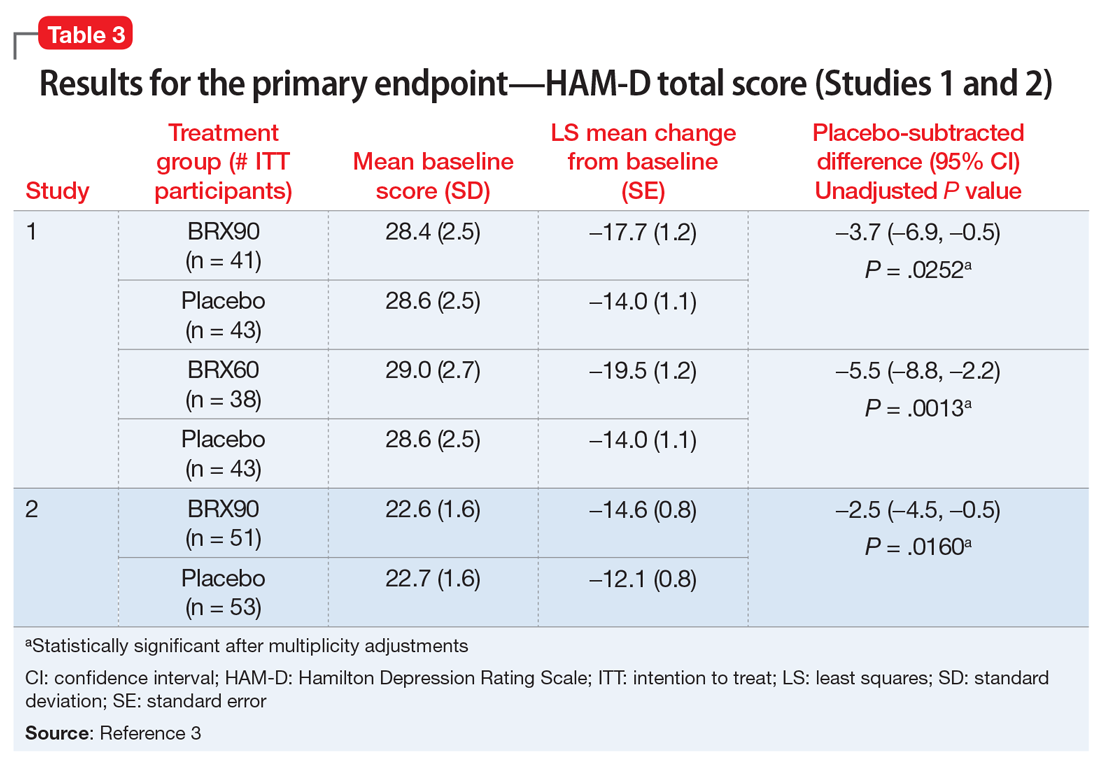

The FDA approval of brexanolone injection was based on the efficacy demonstrated in 2 Phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in adult women (age 18 to 45) with PPD (defined by DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, with onset of symptoms in the third trimester or within 4 weeks of delivery). Exclusion criteria included the presence of bipolar disorder or psychosis. In these studies, 60-hour continuous IV infusions of brexanolone or placebo were given, followed by 4 weeks of observation. Study 1 (202B) enrolled patients with severe PPD (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] total score ≥26), and Study 2 (202C) enrolled patients with moderate PPD (HAM-D score 20 to 25). A titration to the recommended target dosage of 90 μg/kg/hour was evaluated in both studies. BRX90 patients received 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours, 60 μg/kg/hour for 20 hours, 90 μg/kg/hour for 28 hours, followed by a taper to 60 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours and then 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours. The primary endpoint in both studies was the mean change from baseline in depressive symptoms as measured by HAM-D total score at the end of the 60-hour infusion. A pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoint was the mean change from baseline in HAM-D total score at Day 30.

Continue to: Efficacy

Efficacy. In both placebo-controlled studies, titration to a target dose of brexanolone 90 μg/kg/hour was superior to placebo in improvement of depressive symptoms (Table 33).

Pharmacological profile

Brexanolone exposure-response relationships and the time course of pharmacodynamic response are unknown.3

Adverse reactions. Safety was evaluated from all patients receiving brexanolone injection, regardless of dosing regimen (N = 140, including patients from a Phase IIb study, 202A).3,11

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were sedation/somnolence, dry mouth, loss of consciousness, and flushing/hot flush.3 The incidence of patients discontinuing due to any adverse reaction was 2% for brexanolone vs 1% for placebo.3

Sedation, somnolence, and loss of consciousness. In clinical studies, brexanolone caused sedation and somnolence that required dose interruption or reduction in some patients during the infusion (5% of brexanolone-treated patients compared with 0% of placebo-treated patients).3 Some patients were also reported to have loss of consciousness or altered state of consciousness during the brexanolone infusion (4% of patients treated with brexanolone compared with 0% of patients treated with placebo).3 All patients with loss of or altered state of consciousness recovered fully 15 to 60 minutes after dose interruption.3 There was no clear association between loss or alteration of consciousness and pattern or timing of dose, and not all patients who experienced a loss or alteration of consciousness reported sedation or somnolence before the episode.

Continue to: Suicidality

Suicidality. The risk of developing suicidal thoughts and behaviors with brexanolone is unknown, due to the relatively low number of exposures to brexanolone injection during clinical development and a mechanism of action distinct from that of existing antidepressant medications.3

Pharmacokinetics

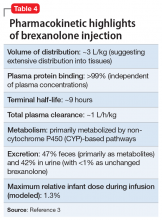

In clinical trials, brexanolone exhibited dose-proportional pharmacokinetics, and the terminal half-life is approximately 9 hours (Table 43). Brexanolone is metabolized by non-cytochrome P450 (CYP)-based pathways, including keto-reduction, glucuronidation, and sulfation.3 No clinically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of brexanolone were observed based on renal or hepatic impairment, and no studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of other drugs on brexanolone.3

Lactation. A population pharmacokinetics model constructed from studies in the clinical development program calculated the maximum relative infant dose for brexanolone during infusion as 1.3%.3 Given the low oral bioavailability of brexanolone (<5%) in adults, the potential for breastfed infant exposure is considered low.3

Clinical considerations

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) requirements. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. It has a “black-box” warning regarding excessive sedation and sudden loss of consciousness, which has been taken into account within the REMS drug safety program. Health care facilities and pharmacies must enroll in the REMS program and ensure that brexanolone is administered only to patients who are enrolled in the REMS program. Staff must be trained on the processes and procedures to administer brexanolone, and the facility must have a fall precautions protocol in place and be equipped with a programmable peristaltic IV infusion pump and continuous pulse oximetry with alarms.3

Monitoring. A REMS-trained clinician must be available continuously on-site to oversee each patient for the duration of the continuous IV infusion, which lasts 60 hours (2.5 days) and should be initiated early enough in the day to allow for recognition of excessive sedation. Patients must be monitored for hypoxia using continuous pulse oximetry equipped with an alarm and should also be assessed for excessive sedation every 2 hours during planned, non-sleep periods. If excessive sedation occurs, the infusion should be stopped until symptoms resolve, after which the infusion may be resumed at the same or a lower dose as clinically appropriate. In case of overdosage, the infusion should be stopped immediately and supportive measures initiated as necessary. Patients must not be the primary caregiver of dependents, and must be accompanied during interactions with their child(ren).

Continue to: Contraindications

Contraindications. There are no contraindications for the use of brexanolone in adults with PPD.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD). Avoid using brexanolone in patients with ESRD because of the potential accumulation of the solubilizing agent, betadex sulfobutyl ether sodium.

Pregnancy. Brexanolone has not been studied in pregnant patients. Pregnant women and women of reproductive age should be informed of the potential risk to a fetus based on data from other drugs that enhance GABAergic inhibition.

Breastfeeding. There are no data on the effects of brexanolone on a breastfed infant. Breastfeeding should be a discussion of risk and benefit between the patient and her doctor. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered, along with the mother’s clinical need for brexanolone and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed child from brexanolone or from the underlying maternal condition. However, based on the low relative infant dose (<2%) and the low oral bioavailability in adults, the risk to breastfed infants is thought to be low.16

Potential for abuse. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. Although it was not possible to assess physical dependency in the registrational trials due to dose tapering at the end of treatment, clinicians should advise patients about the theoretical possibility for brexanolone to be abused or lead to dependence based on other medications with similar primary pharmacology.

Continue to: Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications. Caution patients that taking opioids or other CNS depressants, such as benzodiazepines, in combination with brexanolone may increase the severity of sedative effects.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Advise patients and caregivers to look for the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behavior and instruct them to report such symptoms to their clinician. Consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including discontinuing brexanolone, in patients whose depression becomes worse or who experience emergent suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Why Rx?

Postpartum depression is a common and often devastating medical complication of childbirth that can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when left undertreated or untreated. There is a great need to identify and treat women who develop PPD. Rapid and sustained resolution of symptoms in women who experience PPD should be the goal of treatment, and consequently, brexanolone injection presents an important new tool in available treatment options for PPD.

Bottom Line

Brexanolone injection is a neuroactive steroid gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor positive allosteric modulator that’s been FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). It is administered as a continuous IV infusion over 60 hours. The rapid and sustained improvement of PPD observed in clinical trials with brexanolone injection may support a new treatment paradigm for women with PPD.

1. Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, et al. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms - 27 states, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(6):153-158.

2. Frieder A, Fersh M, Hainline R, et al. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: current approaches and novel drug development. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(3):265-282.

3. Brexanolone injection [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Sage Therapeutics, Inc.; 2019.

4. Bodnar-Deren S, Klipstein K, Fersh M, et al. Suicidal ideation during the postpartum period. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(12):1219-1224.

5. Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, et al. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247-253.

6. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26-35.

7. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al; American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

8. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

9. Molyneaux E, Telesia LA, Henshaw C, et al. Antidepressants for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD004363.

10. Kanes S, Colquhoun H, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):480-489.

11. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

12. Melon LC, Hooper A, Yang X, et al. Inability to suppress the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis during the peripartum period engenders deficits in postpartum behaviors in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;90:182-193.

13. Deligiannidis KM, Fales CL, Kroll-Desrosiers AR, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity, cortical GABA, and neuroactive steroids in peripartum and peripartum depressed women: a functional magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):546-554.

14. Licheri V, Talani G, Gorule AA, et al. Plasticity of GABAA receptors during pregnancy and postpartum period: from gene to function. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:170435. doi: 10.1155/2015/170435.

15. Luisi S, Petraglia F, Benedetto C, et al. Serum allopregnanolone levels in pregnant women: changes during pregnancy, at delivery, and in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2429-2433.

16. Hoffmann E, Wald J, Dray D, et al. Brexanolone injection administration to lactating women: breast milk allopregnanolone levels [30J]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;133:115S.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most prevalent complications associated with pregnancy and childbirth in the United States, affecting more than 400,000 women annually.1 Postpartum depression is most commonly treated with psychotherapy and antidepressants approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Until recently, there was no pharmacologic therapy approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of PPD. Considering the adverse outcomes associated with untreated or inadequately treated PPD, and the limitations of existing therapies, there is a significant unmet need for pharmacologic treatment options for PPD.2 To help address this need, the FDA recently approved brexanolone injection (brand name: ZULRESSO™) (Table 13) as a first-in-class therapy for the treatment of adults with PPD.3

Clinical implications

Postpartum depression can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when under- or untreated, and the need for rapid resolution of symptoms cannot be overstated.2 Suicide is strongly associated with depression and is a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths.4 Additionally, PPD can impact the health, safety, and well-being of the child, with both short- and long-term consequences, including greater rates of psychological or behavioral difficulties among children of patients with PPD.5 Postpartum depression can also have negative effects on the patient’s partner, with 24% to 50% of partners experiencing depression.6 Current PPD management strategies include the use of psychotherapy and pharmacologic interventions for major depressive disorder that may take up to 4 to 6 weeks for some patients, and may not achieve remission for all patients.7-9

Brexanolone injection is a first-in-class medication with a novel mechanism of action. In clinical studies, it achieved rapid (by Hour 60) and sustained (through Day 30) reductions in depressive symptoms and could provide a meaningful new treatment option for adult women with PPD.10,11

How it works

Animal and human studies have established the re

Brexanolone is a neuroactive steroid that is chemically identical to endogenous allopregnanolone produced in the CNS. Brexanolone potentiates GABA-mediated currents from recombinant human GABAARs in mammalian cells expressing α1β2γ2 receptor subunits, α4β3δ receptor subunits, and α6β3δ receptor subunits.3 Positive allosteric modulation of both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAARs differentiates brexanolone from other GABAAR modulators, such as benzodiazepines.10,11

Brexanolone’s mechanism of action in the treatment of PPD is not fully understood, but it is thought to be related to GABAAR PAM activity.3

Supporting evidence

The FDA approval of brexanolone injection was based on the efficacy demonstrated in 2 Phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in adult women (age 18 to 45) with PPD (defined by DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, with onset of symptoms in the third trimester or within 4 weeks of delivery). Exclusion criteria included the presence of bipolar disorder or psychosis. In these studies, 60-hour continuous IV infusions of brexanolone or placebo were given, followed by 4 weeks of observation. Study 1 (202B) enrolled patients with severe PPD (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] total score ≥26), and Study 2 (202C) enrolled patients with moderate PPD (HAM-D score 20 to 25). A titration to the recommended target dosage of 90 μg/kg/hour was evaluated in both studies. BRX90 patients received 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours, 60 μg/kg/hour for 20 hours, 90 μg/kg/hour for 28 hours, followed by a taper to 60 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours and then 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours. The primary endpoint in both studies was the mean change from baseline in depressive symptoms as measured by HAM-D total score at the end of the 60-hour infusion. A pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoint was the mean change from baseline in HAM-D total score at Day 30.

Continue to: Efficacy

Efficacy. In both placebo-controlled studies, titration to a target dose of brexanolone 90 μg/kg/hour was superior to placebo in improvement of depressive symptoms (Table 33).

Pharmacological profile

Brexanolone exposure-response relationships and the time course of pharmacodynamic response are unknown.3

Adverse reactions. Safety was evaluated from all patients receiving brexanolone injection, regardless of dosing regimen (N = 140, including patients from a Phase IIb study, 202A).3,11

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were sedation/somnolence, dry mouth, loss of consciousness, and flushing/hot flush.3 The incidence of patients discontinuing due to any adverse reaction was 2% for brexanolone vs 1% for placebo.3

Sedation, somnolence, and loss of consciousness. In clinical studies, brexanolone caused sedation and somnolence that required dose interruption or reduction in some patients during the infusion (5% of brexanolone-treated patients compared with 0% of placebo-treated patients).3 Some patients were also reported to have loss of consciousness or altered state of consciousness during the brexanolone infusion (4% of patients treated with brexanolone compared with 0% of patients treated with placebo).3 All patients with loss of or altered state of consciousness recovered fully 15 to 60 minutes after dose interruption.3 There was no clear association between loss or alteration of consciousness and pattern or timing of dose, and not all patients who experienced a loss or alteration of consciousness reported sedation or somnolence before the episode.

Continue to: Suicidality

Suicidality. The risk of developing suicidal thoughts and behaviors with brexanolone is unknown, due to the relatively low number of exposures to brexanolone injection during clinical development and a mechanism of action distinct from that of existing antidepressant medications.3

Pharmacokinetics

In clinical trials, brexanolone exhibited dose-proportional pharmacokinetics, and the terminal half-life is approximately 9 hours (Table 43). Brexanolone is metabolized by non-cytochrome P450 (CYP)-based pathways, including keto-reduction, glucuronidation, and sulfation.3 No clinically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of brexanolone were observed based on renal or hepatic impairment, and no studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of other drugs on brexanolone.3

Lactation. A population pharmacokinetics model constructed from studies in the clinical development program calculated the maximum relative infant dose for brexanolone during infusion as 1.3%.3 Given the low oral bioavailability of brexanolone (<5%) in adults, the potential for breastfed infant exposure is considered low.3

Clinical considerations

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) requirements. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. It has a “black-box” warning regarding excessive sedation and sudden loss of consciousness, which has been taken into account within the REMS drug safety program. Health care facilities and pharmacies must enroll in the REMS program and ensure that brexanolone is administered only to patients who are enrolled in the REMS program. Staff must be trained on the processes and procedures to administer brexanolone, and the facility must have a fall precautions protocol in place and be equipped with a programmable peristaltic IV infusion pump and continuous pulse oximetry with alarms.3

Monitoring. A REMS-trained clinician must be available continuously on-site to oversee each patient for the duration of the continuous IV infusion, which lasts 60 hours (2.5 days) and should be initiated early enough in the day to allow for recognition of excessive sedation. Patients must be monitored for hypoxia using continuous pulse oximetry equipped with an alarm and should also be assessed for excessive sedation every 2 hours during planned, non-sleep periods. If excessive sedation occurs, the infusion should be stopped until symptoms resolve, after which the infusion may be resumed at the same or a lower dose as clinically appropriate. In case of overdosage, the infusion should be stopped immediately and supportive measures initiated as necessary. Patients must not be the primary caregiver of dependents, and must be accompanied during interactions with their child(ren).

Continue to: Contraindications

Contraindications. There are no contraindications for the use of brexanolone in adults with PPD.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD). Avoid using brexanolone in patients with ESRD because of the potential accumulation of the solubilizing agent, betadex sulfobutyl ether sodium.

Pregnancy. Brexanolone has not been studied in pregnant patients. Pregnant women and women of reproductive age should be informed of the potential risk to a fetus based on data from other drugs that enhance GABAergic inhibition.

Breastfeeding. There are no data on the effects of brexanolone on a breastfed infant. Breastfeeding should be a discussion of risk and benefit between the patient and her doctor. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered, along with the mother’s clinical need for brexanolone and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed child from brexanolone or from the underlying maternal condition. However, based on the low relative infant dose (<2%) and the low oral bioavailability in adults, the risk to breastfed infants is thought to be low.16

Potential for abuse. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. Although it was not possible to assess physical dependency in the registrational trials due to dose tapering at the end of treatment, clinicians should advise patients about the theoretical possibility for brexanolone to be abused or lead to dependence based on other medications with similar primary pharmacology.

Continue to: Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications. Caution patients that taking opioids or other CNS depressants, such as benzodiazepines, in combination with brexanolone may increase the severity of sedative effects.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Advise patients and caregivers to look for the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behavior and instruct them to report such symptoms to their clinician. Consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including discontinuing brexanolone, in patients whose depression becomes worse or who experience emergent suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Why Rx?

Postpartum depression is a common and often devastating medical complication of childbirth that can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when left undertreated or untreated. There is a great need to identify and treat women who develop PPD. Rapid and sustained resolution of symptoms in women who experience PPD should be the goal of treatment, and consequently, brexanolone injection presents an important new tool in available treatment options for PPD.

Bottom Line

Brexanolone injection is a neuroactive steroid gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor positive allosteric modulator that’s been FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). It is administered as a continuous IV infusion over 60 hours. The rapid and sustained improvement of PPD observed in clinical trials with brexanolone injection may support a new treatment paradigm for women with PPD.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most prevalent complications associated with pregnancy and childbirth in the United States, affecting more than 400,000 women annually.1 Postpartum depression is most commonly treated with psychotherapy and antidepressants approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Until recently, there was no pharmacologic therapy approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of PPD. Considering the adverse outcomes associated with untreated or inadequately treated PPD, and the limitations of existing therapies, there is a significant unmet need for pharmacologic treatment options for PPD.2 To help address this need, the FDA recently approved brexanolone injection (brand name: ZULRESSO™) (Table 13) as a first-in-class therapy for the treatment of adults with PPD.3

Clinical implications

Postpartum depression can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when under- or untreated, and the need for rapid resolution of symptoms cannot be overstated.2 Suicide is strongly associated with depression and is a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths.4 Additionally, PPD can impact the health, safety, and well-being of the child, with both short- and long-term consequences, including greater rates of psychological or behavioral difficulties among children of patients with PPD.5 Postpartum depression can also have negative effects on the patient’s partner, with 24% to 50% of partners experiencing depression.6 Current PPD management strategies include the use of psychotherapy and pharmacologic interventions for major depressive disorder that may take up to 4 to 6 weeks for some patients, and may not achieve remission for all patients.7-9

Brexanolone injection is a first-in-class medication with a novel mechanism of action. In clinical studies, it achieved rapid (by Hour 60) and sustained (through Day 30) reductions in depressive symptoms and could provide a meaningful new treatment option for adult women with PPD.10,11

How it works

Animal and human studies have established the re

Brexanolone is a neuroactive steroid that is chemically identical to endogenous allopregnanolone produced in the CNS. Brexanolone potentiates GABA-mediated currents from recombinant human GABAARs in mammalian cells expressing α1β2γ2 receptor subunits, α4β3δ receptor subunits, and α6β3δ receptor subunits.3 Positive allosteric modulation of both synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAARs differentiates brexanolone from other GABAAR modulators, such as benzodiazepines.10,11

Brexanolone’s mechanism of action in the treatment of PPD is not fully understood, but it is thought to be related to GABAAR PAM activity.3

Supporting evidence

The FDA approval of brexanolone injection was based on the efficacy demonstrated in 2 Phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in adult women (age 18 to 45) with PPD (defined by DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, with onset of symptoms in the third trimester or within 4 weeks of delivery). Exclusion criteria included the presence of bipolar disorder or psychosis. In these studies, 60-hour continuous IV infusions of brexanolone or placebo were given, followed by 4 weeks of observation. Study 1 (202B) enrolled patients with severe PPD (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] total score ≥26), and Study 2 (202C) enrolled patients with moderate PPD (HAM-D score 20 to 25). A titration to the recommended target dosage of 90 μg/kg/hour was evaluated in both studies. BRX90 patients received 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours, 60 μg/kg/hour for 20 hours, 90 μg/kg/hour for 28 hours, followed by a taper to 60 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours and then 30 μg/kg/hour for 4 hours. The primary endpoint in both studies was the mean change from baseline in depressive symptoms as measured by HAM-D total score at the end of the 60-hour infusion. A pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoint was the mean change from baseline in HAM-D total score at Day 30.

Continue to: Efficacy

Efficacy. In both placebo-controlled studies, titration to a target dose of brexanolone 90 μg/kg/hour was superior to placebo in improvement of depressive symptoms (Table 33).

Pharmacological profile

Brexanolone exposure-response relationships and the time course of pharmacodynamic response are unknown.3

Adverse reactions. Safety was evaluated from all patients receiving brexanolone injection, regardless of dosing regimen (N = 140, including patients from a Phase IIb study, 202A).3,11

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were sedation/somnolence, dry mouth, loss of consciousness, and flushing/hot flush.3 The incidence of patients discontinuing due to any adverse reaction was 2% for brexanolone vs 1% for placebo.3

Sedation, somnolence, and loss of consciousness. In clinical studies, brexanolone caused sedation and somnolence that required dose interruption or reduction in some patients during the infusion (5% of brexanolone-treated patients compared with 0% of placebo-treated patients).3 Some patients were also reported to have loss of consciousness or altered state of consciousness during the brexanolone infusion (4% of patients treated with brexanolone compared with 0% of patients treated with placebo).3 All patients with loss of or altered state of consciousness recovered fully 15 to 60 minutes after dose interruption.3 There was no clear association between loss or alteration of consciousness and pattern or timing of dose, and not all patients who experienced a loss or alteration of consciousness reported sedation or somnolence before the episode.

Continue to: Suicidality

Suicidality. The risk of developing suicidal thoughts and behaviors with brexanolone is unknown, due to the relatively low number of exposures to brexanolone injection during clinical development and a mechanism of action distinct from that of existing antidepressant medications.3

Pharmacokinetics

In clinical trials, brexanolone exhibited dose-proportional pharmacokinetics, and the terminal half-life is approximately 9 hours (Table 43). Brexanolone is metabolized by non-cytochrome P450 (CYP)-based pathways, including keto-reduction, glucuronidation, and sulfation.3 No clinically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of brexanolone were observed based on renal or hepatic impairment, and no studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of other drugs on brexanolone.3

Lactation. A population pharmacokinetics model constructed from studies in the clinical development program calculated the maximum relative infant dose for brexanolone during infusion as 1.3%.3 Given the low oral bioavailability of brexanolone (<5%) in adults, the potential for breastfed infant exposure is considered low.3

Clinical considerations

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) requirements. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. It has a “black-box” warning regarding excessive sedation and sudden loss of consciousness, which has been taken into account within the REMS drug safety program. Health care facilities and pharmacies must enroll in the REMS program and ensure that brexanolone is administered only to patients who are enrolled in the REMS program. Staff must be trained on the processes and procedures to administer brexanolone, and the facility must have a fall precautions protocol in place and be equipped with a programmable peristaltic IV infusion pump and continuous pulse oximetry with alarms.3

Monitoring. A REMS-trained clinician must be available continuously on-site to oversee each patient for the duration of the continuous IV infusion, which lasts 60 hours (2.5 days) and should be initiated early enough in the day to allow for recognition of excessive sedation. Patients must be monitored for hypoxia using continuous pulse oximetry equipped with an alarm and should also be assessed for excessive sedation every 2 hours during planned, non-sleep periods. If excessive sedation occurs, the infusion should be stopped until symptoms resolve, after which the infusion may be resumed at the same or a lower dose as clinically appropriate. In case of overdosage, the infusion should be stopped immediately and supportive measures initiated as necessary. Patients must not be the primary caregiver of dependents, and must be accompanied during interactions with their child(ren).

Continue to: Contraindications

Contraindications. There are no contraindications for the use of brexanolone in adults with PPD.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD). Avoid using brexanolone in patients with ESRD because of the potential accumulation of the solubilizing agent, betadex sulfobutyl ether sodium.

Pregnancy. Brexanolone has not been studied in pregnant patients. Pregnant women and women of reproductive age should be informed of the potential risk to a fetus based on data from other drugs that enhance GABAergic inhibition.

Breastfeeding. There are no data on the effects of brexanolone on a breastfed infant. Breastfeeding should be a discussion of risk and benefit between the patient and her doctor. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered, along with the mother’s clinical need for brexanolone and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed child from brexanolone or from the underlying maternal condition. However, based on the low relative infant dose (<2%) and the low oral bioavailability in adults, the risk to breastfed infants is thought to be low.16

Potential for abuse. Brexanolone injection is a Schedule IV controlled substance. Although it was not possible to assess physical dependency in the registrational trials due to dose tapering at the end of treatment, clinicians should advise patients about the theoretical possibility for brexanolone to be abused or lead to dependence based on other medications with similar primary pharmacology.

Continue to: Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications. Caution patients that taking opioids or other CNS depressants, such as benzodiazepines, in combination with brexanolone may increase the severity of sedative effects.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Advise patients and caregivers to look for the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behavior and instruct them to report such symptoms to their clinician. Consider changing the therapeutic regimen, including discontinuing brexanolone, in patients whose depression becomes worse or who experience emergent suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Why Rx?

Postpartum depression is a common and often devastating medical complication of childbirth that can result in adverse outcomes for the patient, baby, and family when left undertreated or untreated. There is a great need to identify and treat women who develop PPD. Rapid and sustained resolution of symptoms in women who experience PPD should be the goal of treatment, and consequently, brexanolone injection presents an important new tool in available treatment options for PPD.

Bottom Line

Brexanolone injection is a neuroactive steroid gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor positive allosteric modulator that’s been FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). It is administered as a continuous IV infusion over 60 hours. The rapid and sustained improvement of PPD observed in clinical trials with brexanolone injection may support a new treatment paradigm for women with PPD.

1. Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, et al. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms - 27 states, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(6):153-158.

2. Frieder A, Fersh M, Hainline R, et al. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: current approaches and novel drug development. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(3):265-282.

3. Brexanolone injection [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Sage Therapeutics, Inc.; 2019.

4. Bodnar-Deren S, Klipstein K, Fersh M, et al. Suicidal ideation during the postpartum period. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(12):1219-1224.

5. Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, et al. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247-253.

6. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26-35.

7. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al; American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

8. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

9. Molyneaux E, Telesia LA, Henshaw C, et al. Antidepressants for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD004363.

10. Kanes S, Colquhoun H, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):480-489.

11. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

12. Melon LC, Hooper A, Yang X, et al. Inability to suppress the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis during the peripartum period engenders deficits in postpartum behaviors in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;90:182-193.

13. Deligiannidis KM, Fales CL, Kroll-Desrosiers AR, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity, cortical GABA, and neuroactive steroids in peripartum and peripartum depressed women: a functional magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):546-554.

14. Licheri V, Talani G, Gorule AA, et al. Plasticity of GABAA receptors during pregnancy and postpartum period: from gene to function. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:170435. doi: 10.1155/2015/170435.

15. Luisi S, Petraglia F, Benedetto C, et al. Serum allopregnanolone levels in pregnant women: changes during pregnancy, at delivery, and in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2429-2433.

16. Hoffmann E, Wald J, Dray D, et al. Brexanolone injection administration to lactating women: breast milk allopregnanolone levels [30J]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;133:115S.

1. Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, et al. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms - 27 states, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(6):153-158.

2. Frieder A, Fersh M, Hainline R, et al. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: current approaches and novel drug development. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(3):265-282.

3. Brexanolone injection [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Sage Therapeutics, Inc.; 2019.

4. Bodnar-Deren S, Klipstein K, Fersh M, et al. Suicidal ideation during the postpartum period. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(12):1219-1224.

5. Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, et al. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247-253.

6. Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26-35.

7. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al; American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

8. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917.

9. Molyneaux E, Telesia LA, Henshaw C, et al. Antidepressants for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD004363.

10. Kanes S, Colquhoun H, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):480-489.

11. Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058-1070.

12. Melon LC, Hooper A, Yang X, et al. Inability to suppress the stress-induced activation of the HPA axis during the peripartum period engenders deficits in postpartum behaviors in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;90:182-193.

13. Deligiannidis KM, Fales CL, Kroll-Desrosiers AR, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity, cortical GABA, and neuroactive steroids in peripartum and peripartum depressed women: a functional magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(3):546-554.

14. Licheri V, Talani G, Gorule AA, et al. Plasticity of GABAA receptors during pregnancy and postpartum period: from gene to function. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:170435. doi: 10.1155/2015/170435.

15. Luisi S, Petraglia F, Benedetto C, et al. Serum allopregnanolone levels in pregnant women: changes during pregnancy, at delivery, and in hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2429-2433.

16. Hoffmann E, Wald J, Dray D, et al. Brexanolone injection administration to lactating women: breast milk allopregnanolone levels [30J]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;133:115S.

‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.