User login

Exercise intervention reverses functional decline in elderly patients during acute hospitalization

Background: Acute hospitalization has been associated with functional and cognitive decline, particularly in elderly adults. This decline is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Study design: Single-center, single-blind, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain.

Synopsis: 370 patients aged 75 years or older who were hospitalized in an acute care unit received either individualized moderate intensity exercise regimens (focusing on resistance, balance, and walking) or standard hospital care (with physical rehabilitation as appropriate). Patients who received standard care had a decrease in functional capacity at discharge when compared with their baseline function (mean change of –5.0 points on the Barthel Index of Independence; 95% confidence interval, –6.8 to –3.2 points), while those who received the exercise intervention had no functional decline from baseline on discharge (mean change of 1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7 points).

Patients who received the exercise intervention had significantly higher scores on functional and cognitive assessments at discharge, compared with patients who received standard hospital care alone. Specifically, the study demonstrated a mean increase of 2.2 points (95% CI, 1.7-2.6 points) on the Short Physical Performance Battery, 6.9 points (95% CI, 4.4-9.5 points) on the Barthel Index, and 1.8 points (95% CI, 1.3-2.3 points) on a cognitive assessment, compared with those who received standard hospital care.

Bottom line: An individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention can help reverse functional and cognitive decline associated with acute hospitalization in elderly patients.

Citation: Martinez-Velilla N et al. Effect of exercise intervention on functional decline in very elderly adults during acute hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):28-36.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: Acute hospitalization has been associated with functional and cognitive decline, particularly in elderly adults. This decline is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Study design: Single-center, single-blind, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain.

Synopsis: 370 patients aged 75 years or older who were hospitalized in an acute care unit received either individualized moderate intensity exercise regimens (focusing on resistance, balance, and walking) or standard hospital care (with physical rehabilitation as appropriate). Patients who received standard care had a decrease in functional capacity at discharge when compared with their baseline function (mean change of –5.0 points on the Barthel Index of Independence; 95% confidence interval, –6.8 to –3.2 points), while those who received the exercise intervention had no functional decline from baseline on discharge (mean change of 1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7 points).

Patients who received the exercise intervention had significantly higher scores on functional and cognitive assessments at discharge, compared with patients who received standard hospital care alone. Specifically, the study demonstrated a mean increase of 2.2 points (95% CI, 1.7-2.6 points) on the Short Physical Performance Battery, 6.9 points (95% CI, 4.4-9.5 points) on the Barthel Index, and 1.8 points (95% CI, 1.3-2.3 points) on a cognitive assessment, compared with those who received standard hospital care.

Bottom line: An individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention can help reverse functional and cognitive decline associated with acute hospitalization in elderly patients.

Citation: Martinez-Velilla N et al. Effect of exercise intervention on functional decline in very elderly adults during acute hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):28-36.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: Acute hospitalization has been associated with functional and cognitive decline, particularly in elderly adults. This decline is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Study design: Single-center, single-blind, randomized clinical trial.

Setting: Acute care unit in a tertiary public hospital in Navarra, Spain.

Synopsis: 370 patients aged 75 years or older who were hospitalized in an acute care unit received either individualized moderate intensity exercise regimens (focusing on resistance, balance, and walking) or standard hospital care (with physical rehabilitation as appropriate). Patients who received standard care had a decrease in functional capacity at discharge when compared with their baseline function (mean change of –5.0 points on the Barthel Index of Independence; 95% confidence interval, –6.8 to –3.2 points), while those who received the exercise intervention had no functional decline from baseline on discharge (mean change of 1.9 points; 95% CI, 0.2-3.7 points).

Patients who received the exercise intervention had significantly higher scores on functional and cognitive assessments at discharge, compared with patients who received standard hospital care alone. Specifically, the study demonstrated a mean increase of 2.2 points (95% CI, 1.7-2.6 points) on the Short Physical Performance Battery, 6.9 points (95% CI, 4.4-9.5 points) on the Barthel Index, and 1.8 points (95% CI, 1.3-2.3 points) on a cognitive assessment, compared with those who received standard hospital care.

Bottom line: An individualized, multicomponent exercise intervention can help reverse functional and cognitive decline associated with acute hospitalization in elderly patients.

Citation: Martinez-Velilla N et al. Effect of exercise intervention on functional decline in very elderly adults during acute hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):28-36.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Zulresso: Hope and lingering questions

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

The last decade has brought increasing awareness of the need to effectively screen for postpartum depression, with a majority of states across the country now having some sort of formal program by which women are screened for mood disorder during the postnatal period, typically with scales such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

In addition to effective screening is a pressing need for effective referral networks of clinicians who have both the expertise and time to manage the 10%-15% of women who have been identified and who suffer from postpartum psychiatric disorders – both postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that only a small percentage of postpartum women who score with clinically significant level of depressive symptoms actually get to a clinician or, if they do get to a clinician, receive adequate treatment restoring their emotional well-being (J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-200).

Zulresso (brexanolone), a novel new antidepressant medication which recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of postpartum depression, is a first-in-class molecule to get such approval. Zulresso is a neurosteroid, an analogue of allopregnanolone and a GABAA receptor–positive allosteric modulator, a primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

There is every reason to believe that, as a class, this group of neurosteroid molecules are effective in treating depression in other populations aside from women with postpartum depression and hence may not be specific to the postpartum period. For example, recent presentations of preliminary data suggest other neurosteroids such as zuranolone (an oral medication also developed by Sage Therapeutics) is effective for both men and women who have major depression in addition to women suffering from postpartum depression.

Zulresso is approved through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–restricted program and, per that protocol, needs to be administered by a health care provider in a recognized health care setting intravenously over 2.5 days (60 hours). Because of concerns regarding increased sedation, continuous pulse oximetry is required, and this is outlined in a boxed warning in the prescribing information. Zulresso has been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a Schedule IV injection and is subject to the prescribing regulations for a controlled substance.

Since Zulresso’s approval, my colleagues and I at the Center for Women’s Mental Health have received numerous queries from patients and colleagues about our clinical impression of this new molecule with a different mechanism of action – a welcome addition to the antidepressant pharmacopeia. The question posed to us essentially is: Where does brexanolone fit into our algorithm for treating women who suffer from postpartum depression? And frequently, the follow-up query is: Because subjects in the clinical trials for this medication included women who had onset of depression either late in pregnancy or during the postpartum period, how specific is brexanolone with respect to being a targeted therapy for postpartum depression, compared with depression encountered in other clinical settings.

What clearly can be stated is that Zulresso has a rapid onset of action and was demonstrated across clinical trials to have sustained benefit up to 30 days after IV administration. The question is whether patients have sustained benefit after 30 days or if this is a medicine to be considered as a “bridge” to other treatment. Data answering that critical clinical question are unavailable at this time. From a clinical standpoint, do patients receive this treatment and get sent home on antidepressants, as we would for patients who receive ECT, often discharging them with prophylactic antidepressants to sustain the benefit of the treatment? Or do patients receive this new medicine with the clinician providing close follow-up, assuming a wait-and-see approach? Because data informing the answer to that question are not available, this decision will be made empirically, frequently factoring in the patient’s past clinical history where presumably more liberal use of antidepressant immediately after the administration of Zulresso will be pursued in those with histories of highly recurrent major depression.

So where might this new medicine fit into the treatment of postpartum depression of moderate severity, or modest to moderate severity? It should be kept in mind that for patients with mild to moderate postpartum depression, there are data supporting the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT frequently is pursued with concurrent mobilization of substantial social support with good outcomes. In patients with more severe postpartum depression, there are data supporting the use of antidepressants, and in these patients as well, use of established support from the ever-growing network of community-based support groups and services can be particularly helpful. It is unlikely that Zulresso will be a first-line medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, but it may be particularly appropriate for patients with severe illness who have not responded to other interventions.

Other practical considerations regarding use of Zulresso include the requirement that the medicine be administered in hospitals that have established clinical infrastructure to accommodate this particular population of patients and where pharmacists and other relevant parties in hospitals have accepted the medicine into its drug formulary. While coverage by various insurance policies may vary, the cost of this new medication is substantial, between $24,000 and $34,000 per treatment, according to reports.

Where Zulresso fits into the pharmacopeia for treating postpartum depression may fall well beyond the issues of efficacy. Given all of the attention to this first-in-class medicine, Zulresso has reinforced the growing interest in the substantial prevalence and the morbidity associated with postpartum depression. It is hard to imagine Zulresso being used in cases of more mild to moderate depression, in which there is nonemergent opportunity to pursue options that do not require a new mom to absent herself from homelife with a newborn. However, in picking cases of severe new onset or recurrence of depression in postpartum women, the rapid onset of benefit that was noted within days could be an extraordinary relief and be the beginning of a road to wellness for some women.

Ultimately, the collaboration of patients with their doctors, the realities of cost, and the acceptability of use in various clinical settings will determine how Zulresso is incorporated into seeking treatment to mitigate the suffering associated with postpartum depression. We at the Center for Women’s Mental Health are interested in user experience with respect to this medicine and welcome comments from both patients and their doctors at [email protected].

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. This center was an investigator site for one of the studies supported by Sage Therapeutics, the manufacturer of Zulresso. Dr. Cohen is also the Edmund and Carroll Carpenter professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Expert shares tips for laser hair removal prior to gender reassignment surgery

SAN DIEGO – prior to undergoing the procedures.

“In the last year, in terms of hair removal, this has been the biggest change in my practice,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Melanie Grossman, MD, who practices in New York City, developed laser hair removal in the 1990s, and today laser hair removal stands as the most common laser treatment in medicine, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. He described it as “safe and effective in skilled hands,” requiring about six treatments. Indications are for hypertrichosis, hirsutism (sometimes in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome), pseudofolliculitis barbae, pilonidal cysts, and gender reassignment surgery.

Laser hair removal works by the extended theory of selective photothermolysis. “You’re targeting by proxy,” Dr. Avram explained. “The laser targets eumelanin in darkly pigmented hairs, with the secondary target being the follicular stem cells. Pigment is a prerequisite for effective treatment. So if there is no pigment in the hair, with current technology, it’s not going to work.”

He advises clinicians to avoid a cookbook approach to fluences when performing laser hair removal. Even though higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, they are also more likely to cause unexpected side effects. “The recommended treatment fluences are often provided with each individual laser device for nonexperienced operators, but I would not recommend doing that,” he said. “You want to evaluate for the desired clinical endpoint of perifollicular erythema and edema. The highest possible tolerated fluence, which yields this endpoint, without any adverse effects, is often the best fluence for treatment.” In 2016, Dr. Avram and his colleagues published a paper that focuses on desirable and therapeutic endpoints when performing laser and light treatments (J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74[5]:821-33).

The best candidates for laser hair removal are those with light skin color and dark hair. “The more pigment that’s in the hair, the more it’s going to absorb the energy,” he said. Coarse, thick hair responds better than thin vellus hairs, and blond, gray hairs do not respond. A new silver nanoparticle technology is being developed that may improve efficacy for people with blond or gray hair in the future. “Modest initial data showed that it works, but it requires several treatments,” Dr. Avram said.

A past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Avram went on to note that laser hair removal is often delegated to nonphysicians and is the most common cause of lawsuits for laser injury. “The rates of lawsuits rise dramatically when delegated to nonphysicians,” he said. “They even rise higher when performed by nonphysicians without supervision such as in medi-spas. Some of the side effects when performed by nonexperienced users can include temporary hyperpigmentation and longterm hypopigmentation.”

One of his clinical pearls is to never perform laser hair removal on suntanned individuals (“you will get obvious, bizarre-appearing hypopigmentation,” he said) and to exercise caution in patients with darker skin types. “If you do a test spot, give it a couple of weeks to see if hyperpigmentation develops,” he advised. “However, their sun exposure may change, and the area you treat with a test spot may be different than the entire area you intend to treat, so don’t think that a test spot is going to guarantee a particular result. You also have to be aware of paradoxical hypertrichosis, where you get more hair growth rather than less.”

Laser hair removal is mandatory prior to neovaginoplasty surgery. Surgeons use skin from the penile shaft and the midscrotum to create the new vagina, Dr. Avram said, so all hair must be removed prior to surgery so that the inside of the new vagina will be free of hair.

“You can use laser or electrolysis for this,” he said. “Electrolysis takes a lot more treatments and is going to be much more tedious than laser hair removal.” Areas to be targeted include all hair on the scrotum and all hair on the penile shaft, plus one inch around the base. “In the perineum, you want to remove hair from the bottom of the scrotum to one inch above the anus in order to clear a 2.5-inch-wide strip,” he said.

For a phalloplasty, surgeons use skin from the underside of arm to create a urethra. This means that all hair should be removed from the crease of the wrist to 15-18 cm up the arm. “You treat the underside of the arm at 4 cm distally and 5.5 cm proximally,” Dr. Avram said. “It should be 15-18 cm in length, and you cannot have any hair that remains within the new urethra.”

To create a penis, surgeons use skin from the prone arm and around. This requires removing hair at 10 cm distally, 13 cm proximally, and 14 cm in length.

Dr. Avram emphasized the importance of patient and staff education and use of preferred pronouns when performing laser hair removal on patients prior to their gender reassignment surgery. “It requires an explanation that this requires multiple treatments and will not remove all hair,” he said. “You can work with an experienced electrologist for nonresponsive hair.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea and intellectual property rights with Cytrellis.

SAN DIEGO – prior to undergoing the procedures.

“In the last year, in terms of hair removal, this has been the biggest change in my practice,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Melanie Grossman, MD, who practices in New York City, developed laser hair removal in the 1990s, and today laser hair removal stands as the most common laser treatment in medicine, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. He described it as “safe and effective in skilled hands,” requiring about six treatments. Indications are for hypertrichosis, hirsutism (sometimes in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome), pseudofolliculitis barbae, pilonidal cysts, and gender reassignment surgery.

Laser hair removal works by the extended theory of selective photothermolysis. “You’re targeting by proxy,” Dr. Avram explained. “The laser targets eumelanin in darkly pigmented hairs, with the secondary target being the follicular stem cells. Pigment is a prerequisite for effective treatment. So if there is no pigment in the hair, with current technology, it’s not going to work.”

He advises clinicians to avoid a cookbook approach to fluences when performing laser hair removal. Even though higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, they are also more likely to cause unexpected side effects. “The recommended treatment fluences are often provided with each individual laser device for nonexperienced operators, but I would not recommend doing that,” he said. “You want to evaluate for the desired clinical endpoint of perifollicular erythema and edema. The highest possible tolerated fluence, which yields this endpoint, without any adverse effects, is often the best fluence for treatment.” In 2016, Dr. Avram and his colleagues published a paper that focuses on desirable and therapeutic endpoints when performing laser and light treatments (J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74[5]:821-33).

The best candidates for laser hair removal are those with light skin color and dark hair. “The more pigment that’s in the hair, the more it’s going to absorb the energy,” he said. Coarse, thick hair responds better than thin vellus hairs, and blond, gray hairs do not respond. A new silver nanoparticle technology is being developed that may improve efficacy for people with blond or gray hair in the future. “Modest initial data showed that it works, but it requires several treatments,” Dr. Avram said.

A past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Avram went on to note that laser hair removal is often delegated to nonphysicians and is the most common cause of lawsuits for laser injury. “The rates of lawsuits rise dramatically when delegated to nonphysicians,” he said. “They even rise higher when performed by nonphysicians without supervision such as in medi-spas. Some of the side effects when performed by nonexperienced users can include temporary hyperpigmentation and longterm hypopigmentation.”

One of his clinical pearls is to never perform laser hair removal on suntanned individuals (“you will get obvious, bizarre-appearing hypopigmentation,” he said) and to exercise caution in patients with darker skin types. “If you do a test spot, give it a couple of weeks to see if hyperpigmentation develops,” he advised. “However, their sun exposure may change, and the area you treat with a test spot may be different than the entire area you intend to treat, so don’t think that a test spot is going to guarantee a particular result. You also have to be aware of paradoxical hypertrichosis, where you get more hair growth rather than less.”

Laser hair removal is mandatory prior to neovaginoplasty surgery. Surgeons use skin from the penile shaft and the midscrotum to create the new vagina, Dr. Avram said, so all hair must be removed prior to surgery so that the inside of the new vagina will be free of hair.

“You can use laser or electrolysis for this,” he said. “Electrolysis takes a lot more treatments and is going to be much more tedious than laser hair removal.” Areas to be targeted include all hair on the scrotum and all hair on the penile shaft, plus one inch around the base. “In the perineum, you want to remove hair from the bottom of the scrotum to one inch above the anus in order to clear a 2.5-inch-wide strip,” he said.

For a phalloplasty, surgeons use skin from the underside of arm to create a urethra. This means that all hair should be removed from the crease of the wrist to 15-18 cm up the arm. “You treat the underside of the arm at 4 cm distally and 5.5 cm proximally,” Dr. Avram said. “It should be 15-18 cm in length, and you cannot have any hair that remains within the new urethra.”

To create a penis, surgeons use skin from the prone arm and around. This requires removing hair at 10 cm distally, 13 cm proximally, and 14 cm in length.

Dr. Avram emphasized the importance of patient and staff education and use of preferred pronouns when performing laser hair removal on patients prior to their gender reassignment surgery. “It requires an explanation that this requires multiple treatments and will not remove all hair,” he said. “You can work with an experienced electrologist for nonresponsive hair.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea and intellectual property rights with Cytrellis.

SAN DIEGO – prior to undergoing the procedures.

“In the last year, in terms of hair removal, this has been the biggest change in my practice,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Melanie Grossman, MD, who practices in New York City, developed laser hair removal in the 1990s, and today laser hair removal stands as the most common laser treatment in medicine, said Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. He described it as “safe and effective in skilled hands,” requiring about six treatments. Indications are for hypertrichosis, hirsutism (sometimes in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome), pseudofolliculitis barbae, pilonidal cysts, and gender reassignment surgery.

Laser hair removal works by the extended theory of selective photothermolysis. “You’re targeting by proxy,” Dr. Avram explained. “The laser targets eumelanin in darkly pigmented hairs, with the secondary target being the follicular stem cells. Pigment is a prerequisite for effective treatment. So if there is no pigment in the hair, with current technology, it’s not going to work.”

He advises clinicians to avoid a cookbook approach to fluences when performing laser hair removal. Even though higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, they are also more likely to cause unexpected side effects. “The recommended treatment fluences are often provided with each individual laser device for nonexperienced operators, but I would not recommend doing that,” he said. “You want to evaluate for the desired clinical endpoint of perifollicular erythema and edema. The highest possible tolerated fluence, which yields this endpoint, without any adverse effects, is often the best fluence for treatment.” In 2016, Dr. Avram and his colleagues published a paper that focuses on desirable and therapeutic endpoints when performing laser and light treatments (J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74[5]:821-33).

The best candidates for laser hair removal are those with light skin color and dark hair. “The more pigment that’s in the hair, the more it’s going to absorb the energy,” he said. Coarse, thick hair responds better than thin vellus hairs, and blond, gray hairs do not respond. A new silver nanoparticle technology is being developed that may improve efficacy for people with blond or gray hair in the future. “Modest initial data showed that it works, but it requires several treatments,” Dr. Avram said.

A past president of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Avram went on to note that laser hair removal is often delegated to nonphysicians and is the most common cause of lawsuits for laser injury. “The rates of lawsuits rise dramatically when delegated to nonphysicians,” he said. “They even rise higher when performed by nonphysicians without supervision such as in medi-spas. Some of the side effects when performed by nonexperienced users can include temporary hyperpigmentation and longterm hypopigmentation.”

One of his clinical pearls is to never perform laser hair removal on suntanned individuals (“you will get obvious, bizarre-appearing hypopigmentation,” he said) and to exercise caution in patients with darker skin types. “If you do a test spot, give it a couple of weeks to see if hyperpigmentation develops,” he advised. “However, their sun exposure may change, and the area you treat with a test spot may be different than the entire area you intend to treat, so don’t think that a test spot is going to guarantee a particular result. You also have to be aware of paradoxical hypertrichosis, where you get more hair growth rather than less.”

Laser hair removal is mandatory prior to neovaginoplasty surgery. Surgeons use skin from the penile shaft and the midscrotum to create the new vagina, Dr. Avram said, so all hair must be removed prior to surgery so that the inside of the new vagina will be free of hair.

“You can use laser or electrolysis for this,” he said. “Electrolysis takes a lot more treatments and is going to be much more tedious than laser hair removal.” Areas to be targeted include all hair on the scrotum and all hair on the penile shaft, plus one inch around the base. “In the perineum, you want to remove hair from the bottom of the scrotum to one inch above the anus in order to clear a 2.5-inch-wide strip,” he said.

For a phalloplasty, surgeons use skin from the underside of arm to create a urethra. This means that all hair should be removed from the crease of the wrist to 15-18 cm up the arm. “You treat the underside of the arm at 4 cm distally and 5.5 cm proximally,” Dr. Avram said. “It should be 15-18 cm in length, and you cannot have any hair that remains within the new urethra.”

To create a penis, surgeons use skin from the prone arm and around. This requires removing hair at 10 cm distally, 13 cm proximally, and 14 cm in length.

Dr. Avram emphasized the importance of patient and staff education and use of preferred pronouns when performing laser hair removal on patients prior to their gender reassignment surgery. “It requires an explanation that this requires multiple treatments and will not remove all hair,” he said. “You can work with an experienced electrologist for nonresponsive hair.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea and intellectual property rights with Cytrellis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MOA 2019

Two uveitis treatment options yield similar success

in an international, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial.

“The findings of this trial have implications for clinical practice because they provide scientific justification that mycophenolate mofetil is not more effective than methotrexate as a corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis,” wrote S.R. Rathinam, MD, PhD, of Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology, Madurai, India, and colleagues.

Although corticosteroid therapy is the first-line treatment for uveitis, adverse effects limit long-term use. Mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate are options for corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis, but their effectiveness has not been compared until the current study, they said.

In the First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment (FAST) trial published Sept. 10 in JAMA, the researchers randomized 216 adults with uveitis (a total of 407 eyes with uveitis) to 25 mg of weekly oral methotrexate or 1.5 g of twice-daily oral mycophenolate mofetil at nine referral eye care centers in India, the United States, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico; the investigators were masked to the treatment assignment.

Patients with treatment success continued taking their randomized medication for another 6 months. If treatment failed, patients switched to the other antimetabolite with another 6-month follow-up. Overall, 84%-93% in each group had bilateral uveitis. Forty-six patients (21%) had intermediate uveitis only or anterior uveitis and intermediate uveitis, and 170 patients (79%) had posterior uveitis or panuveitis. The median age of the patients was 36 years in the methotrexate group and 41 years in the mycophenolate group; other demographic characteristics were similar between the groups.

Overall, 64 patients given methotrexate (67%) and 56 of those given mycophenolate (57%) achieved treatment success at 6 months. Treatment success included inflammation control defined as “less than or equal to 0.5+ anterior chamber cells by Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria, less than or equal to 0.5+ vitreous haze clinical grading using the National Eye Institute scale, and no active retinal or choroidal lesions,” as well as needing no more than 7.5 mg of prednisone daily and two drops or less of prednisolone acetate 1% per day, and reporting no intolerability or safety concerns requiring study discontinuation.

Adverse events were similar between the groups. The most common nonserious adverse events were fatigue and headaches, and the most common nonserious laboratory adverse event was elevated liver enzymes. Fourteen serious adverse events occurred during the study period; three in the methotrexate group and two in the mycophenolate group were deemed drug related and all were elevated liver function tests.

The study findings had several limitations, including lack of masking of the patients to the medication and an inability to compare between types of uveitis, the researchers noted. Avenues for further research include whether one of the drugs is more effective based on the uveitis subtype, they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Eye Institute and study drugs were provided by the University of California San Francisco Pharmacy. Dr. Rathinam disclosed grants from Aravind Eye Hospital, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Novotech, and Bayer.

SOURCE: Rathinam SR et al. JAMA. 2019;322(10):936-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12618.

in an international, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial.

“The findings of this trial have implications for clinical practice because they provide scientific justification that mycophenolate mofetil is not more effective than methotrexate as a corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis,” wrote S.R. Rathinam, MD, PhD, of Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology, Madurai, India, and colleagues.

Although corticosteroid therapy is the first-line treatment for uveitis, adverse effects limit long-term use. Mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate are options for corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis, but their effectiveness has not been compared until the current study, they said.

In the First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment (FAST) trial published Sept. 10 in JAMA, the researchers randomized 216 adults with uveitis (a total of 407 eyes with uveitis) to 25 mg of weekly oral methotrexate or 1.5 g of twice-daily oral mycophenolate mofetil at nine referral eye care centers in India, the United States, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico; the investigators were masked to the treatment assignment.

Patients with treatment success continued taking their randomized medication for another 6 months. If treatment failed, patients switched to the other antimetabolite with another 6-month follow-up. Overall, 84%-93% in each group had bilateral uveitis. Forty-six patients (21%) had intermediate uveitis only or anterior uveitis and intermediate uveitis, and 170 patients (79%) had posterior uveitis or panuveitis. The median age of the patients was 36 years in the methotrexate group and 41 years in the mycophenolate group; other demographic characteristics were similar between the groups.

Overall, 64 patients given methotrexate (67%) and 56 of those given mycophenolate (57%) achieved treatment success at 6 months. Treatment success included inflammation control defined as “less than or equal to 0.5+ anterior chamber cells by Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria, less than or equal to 0.5+ vitreous haze clinical grading using the National Eye Institute scale, and no active retinal or choroidal lesions,” as well as needing no more than 7.5 mg of prednisone daily and two drops or less of prednisolone acetate 1% per day, and reporting no intolerability or safety concerns requiring study discontinuation.

Adverse events were similar between the groups. The most common nonserious adverse events were fatigue and headaches, and the most common nonserious laboratory adverse event was elevated liver enzymes. Fourteen serious adverse events occurred during the study period; three in the methotrexate group and two in the mycophenolate group were deemed drug related and all were elevated liver function tests.

The study findings had several limitations, including lack of masking of the patients to the medication and an inability to compare between types of uveitis, the researchers noted. Avenues for further research include whether one of the drugs is more effective based on the uveitis subtype, they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Eye Institute and study drugs were provided by the University of California San Francisco Pharmacy. Dr. Rathinam disclosed grants from Aravind Eye Hospital, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Novotech, and Bayer.

SOURCE: Rathinam SR et al. JAMA. 2019;322(10):936-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12618.

in an international, multicenter, open-label, randomized trial.

“The findings of this trial have implications for clinical practice because they provide scientific justification that mycophenolate mofetil is not more effective than methotrexate as a corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis,” wrote S.R. Rathinam, MD, PhD, of Aravind Eye Hospital and Postgraduate Institute of Ophthalmology, Madurai, India, and colleagues.

Although corticosteroid therapy is the first-line treatment for uveitis, adverse effects limit long-term use. Mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate are options for corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive therapy for uveitis, but their effectiveness has not been compared until the current study, they said.

In the First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment (FAST) trial published Sept. 10 in JAMA, the researchers randomized 216 adults with uveitis (a total of 407 eyes with uveitis) to 25 mg of weekly oral methotrexate or 1.5 g of twice-daily oral mycophenolate mofetil at nine referral eye care centers in India, the United States, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico; the investigators were masked to the treatment assignment.

Patients with treatment success continued taking their randomized medication for another 6 months. If treatment failed, patients switched to the other antimetabolite with another 6-month follow-up. Overall, 84%-93% in each group had bilateral uveitis. Forty-six patients (21%) had intermediate uveitis only or anterior uveitis and intermediate uveitis, and 170 patients (79%) had posterior uveitis or panuveitis. The median age of the patients was 36 years in the methotrexate group and 41 years in the mycophenolate group; other demographic characteristics were similar between the groups.

Overall, 64 patients given methotrexate (67%) and 56 of those given mycophenolate (57%) achieved treatment success at 6 months. Treatment success included inflammation control defined as “less than or equal to 0.5+ anterior chamber cells by Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria, less than or equal to 0.5+ vitreous haze clinical grading using the National Eye Institute scale, and no active retinal or choroidal lesions,” as well as needing no more than 7.5 mg of prednisone daily and two drops or less of prednisolone acetate 1% per day, and reporting no intolerability or safety concerns requiring study discontinuation.

Adverse events were similar between the groups. The most common nonserious adverse events were fatigue and headaches, and the most common nonserious laboratory adverse event was elevated liver enzymes. Fourteen serious adverse events occurred during the study period; three in the methotrexate group and two in the mycophenolate group were deemed drug related and all were elevated liver function tests.

The study findings had several limitations, including lack of masking of the patients to the medication and an inability to compare between types of uveitis, the researchers noted. Avenues for further research include whether one of the drugs is more effective based on the uveitis subtype, they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Eye Institute and study drugs were provided by the University of California San Francisco Pharmacy. Dr. Rathinam disclosed grants from Aravind Eye Hospital, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Novotech, and Bayer.

SOURCE: Rathinam SR et al. JAMA. 2019;322(10):936-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12618.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate were similar as corticosteroid-sparing treatment in patients with uveitis.

Major finding: Among uveitis patients, 67% of those given methotrexate and 57% of those given mycophenolate achieved corticosteroid-sparing control of inflammation.

Study details: The data come from a randomized trial of 216 adults with noninfectious uveitis at nine referral eye care centers in India, the United States, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the National Eye Institute and study drugs were provided by the University of California San Francisco Pharmacy. Dr. Rathinam disclosed grants from Aravind Eye Hospital, and several coauthors disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Novotech, and Bayer.

Source: Rathinam SR et al. JAMA. 2019;322(10):936-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12618.

Painful and Pruritic Erosions on the Back

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

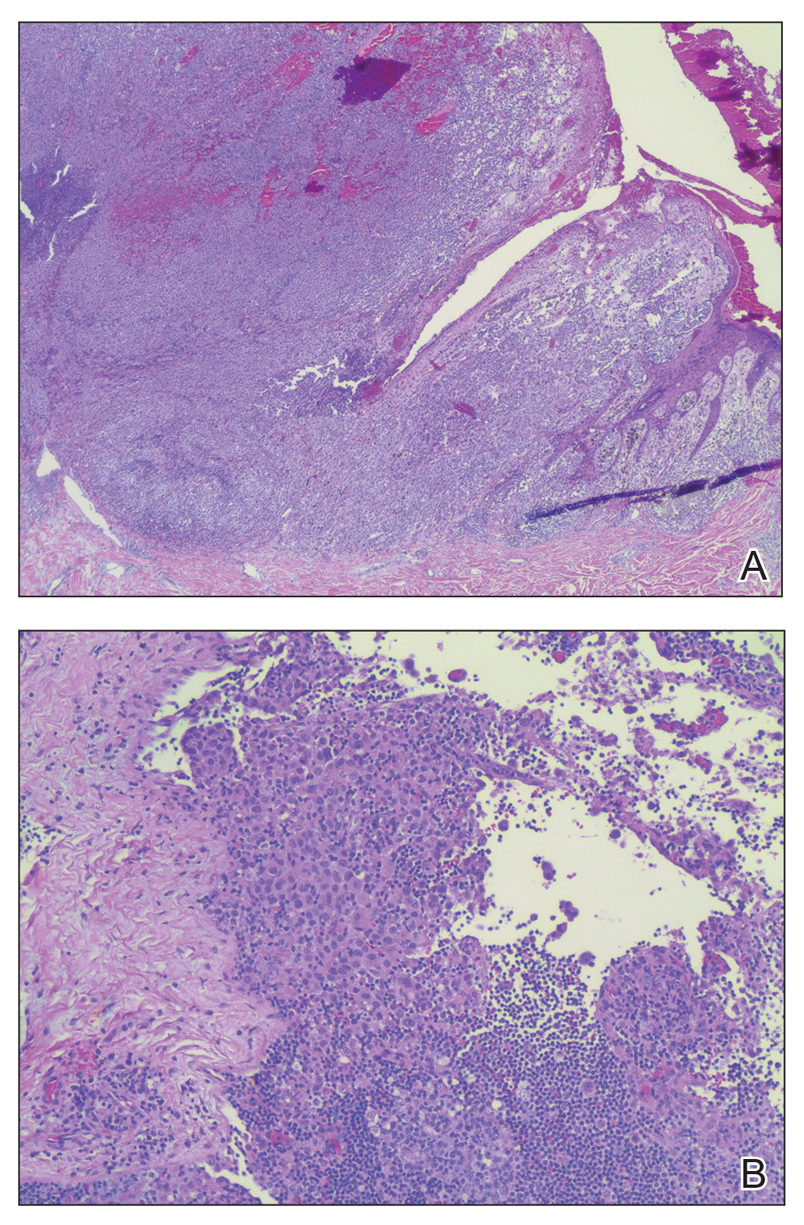

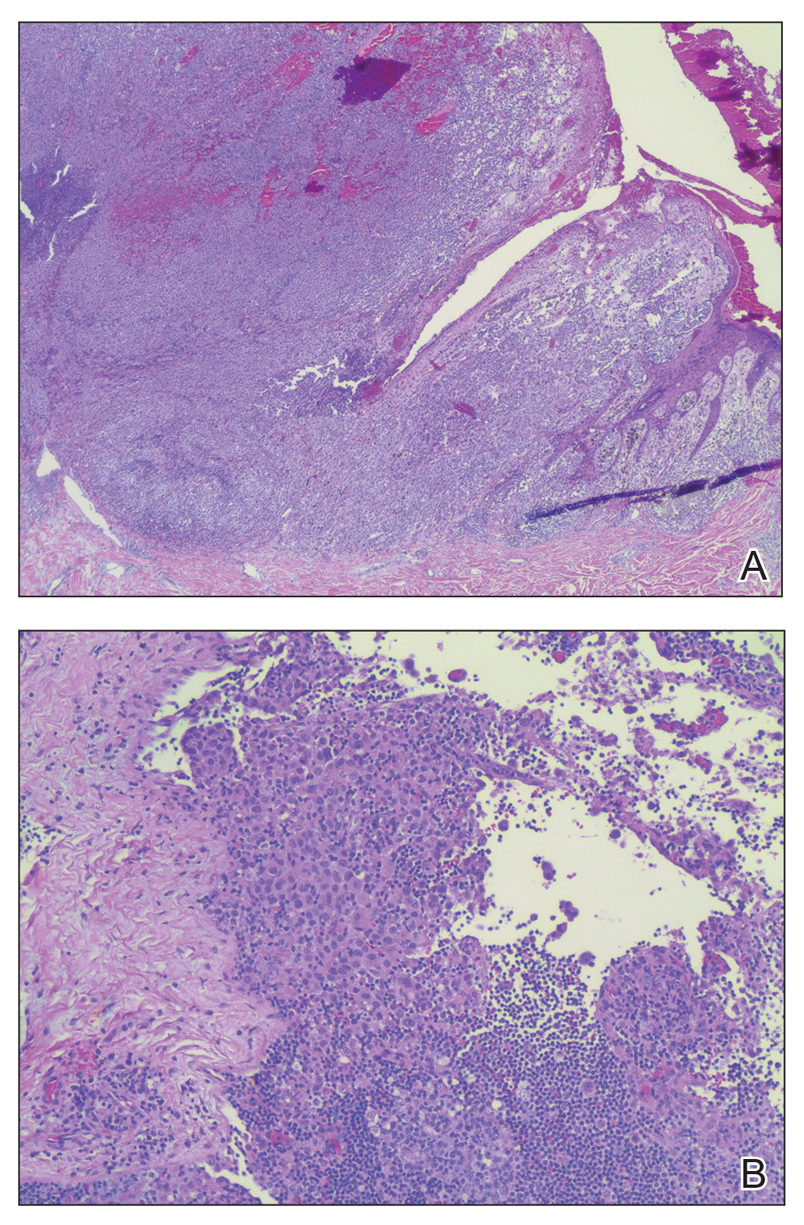

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

A 51-year-old black woman presented to the dermatology clinic with painful and pruritic erosions on the back, abdomen, neck, and arms of approximately 2 months' duration. The lesions started on the back and spread in a cephalocaudal manner. The patient denied any new changes in medication. Physical examination revealed large erosions with mild weeping of serosanguineous fluid on the back, abdomen, neck, and upper extremities. A few tense bullae were present on the dorsal aspect of the right hand. She had experienced a similar flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. At that time, 2 shave biopsies from vesiculobullous lesions on the right side of the neck were sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Biopsy results showed a subepidermal blister that extended along the course of the hair follicle and was associated with an infiltrate of neutrophilic granulocytes that also extended along the course of the hair follicle. Direct immunofluorescence showed IgG and C3 deposition in the basement membrane zone extending along the floor of the blister where the epidermis was separated from the dermis.

Sniffing Out Malignant Melanoma: A Case of Canine Olfactory Detection

To the Editor:

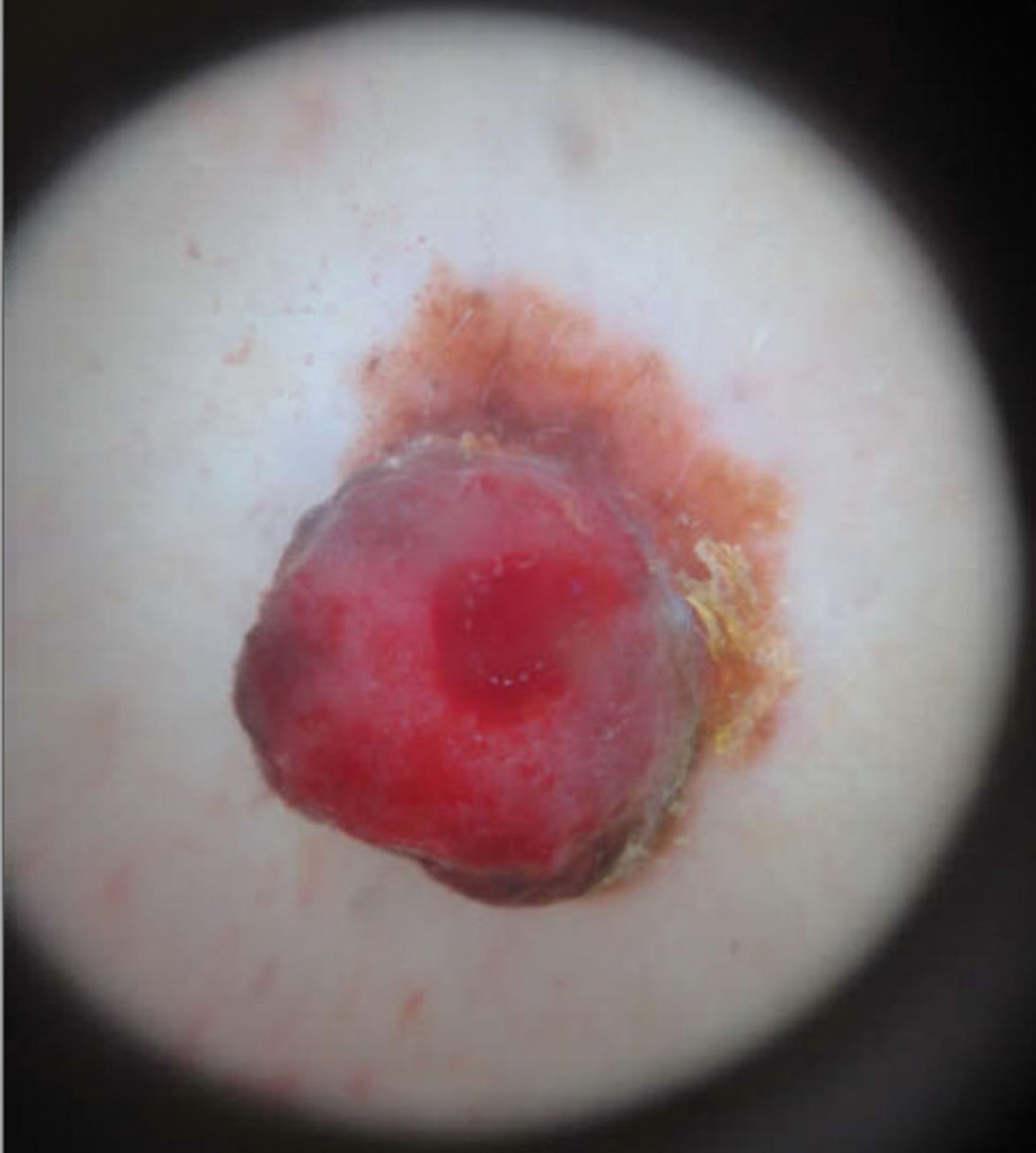

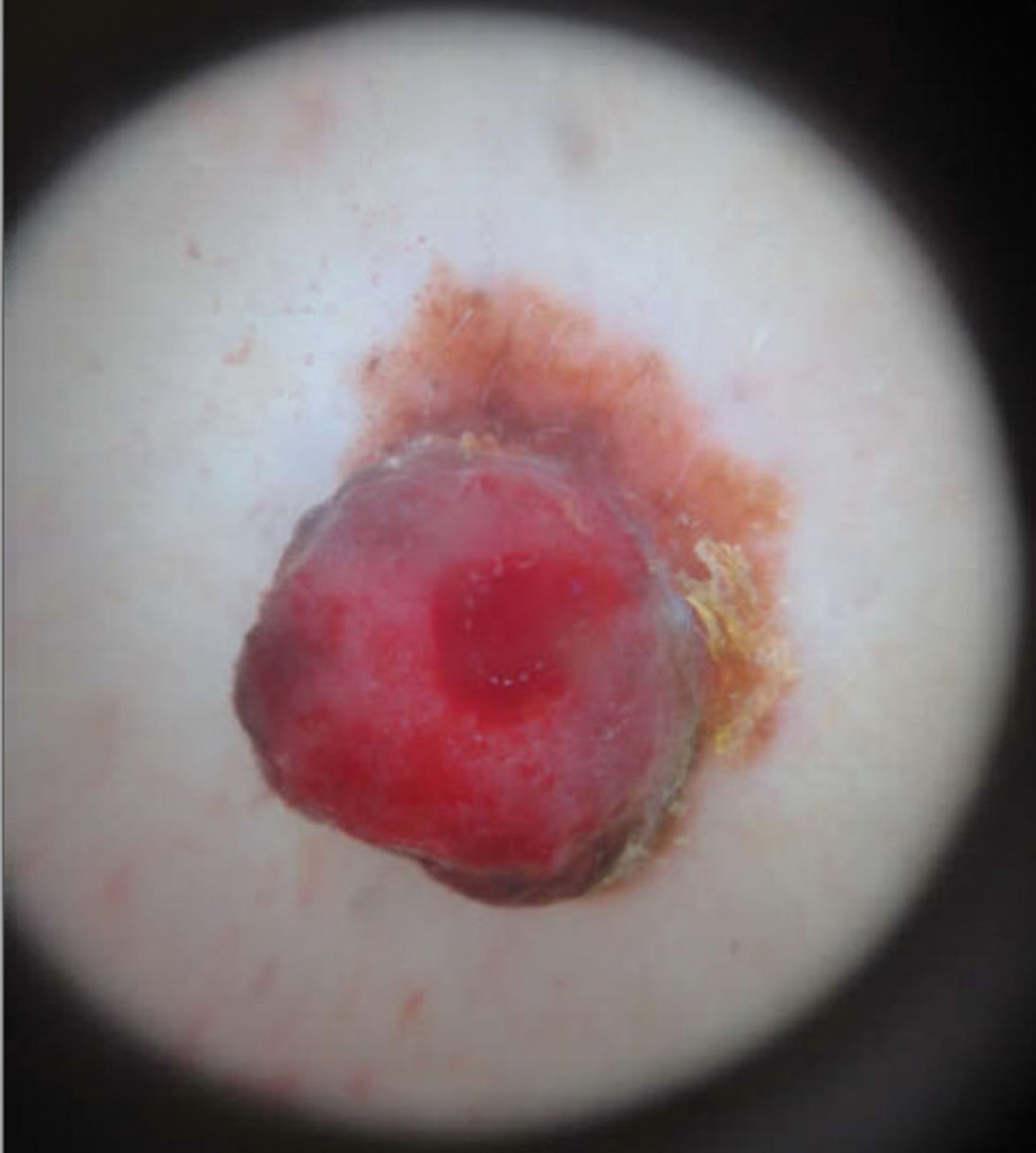

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

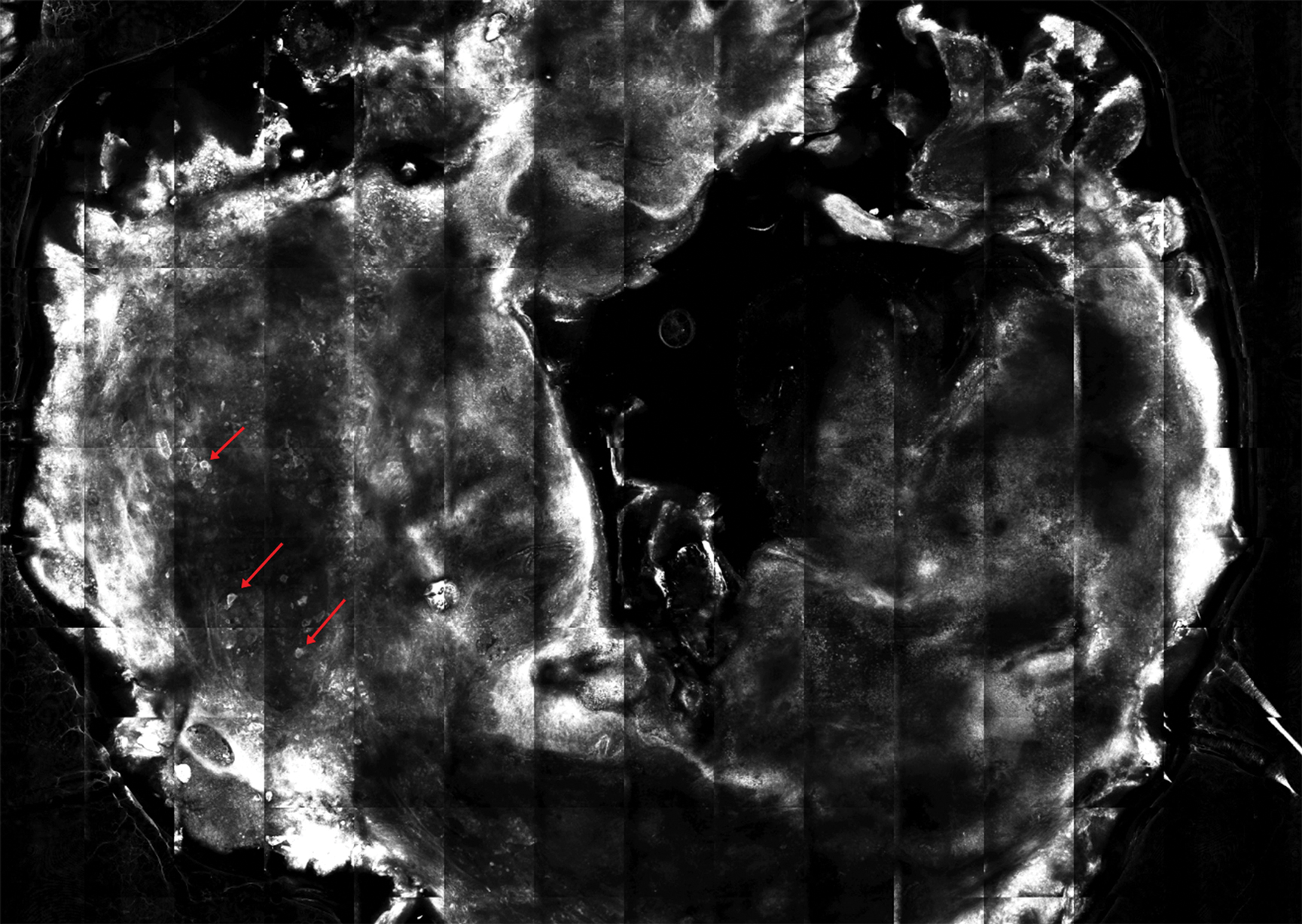

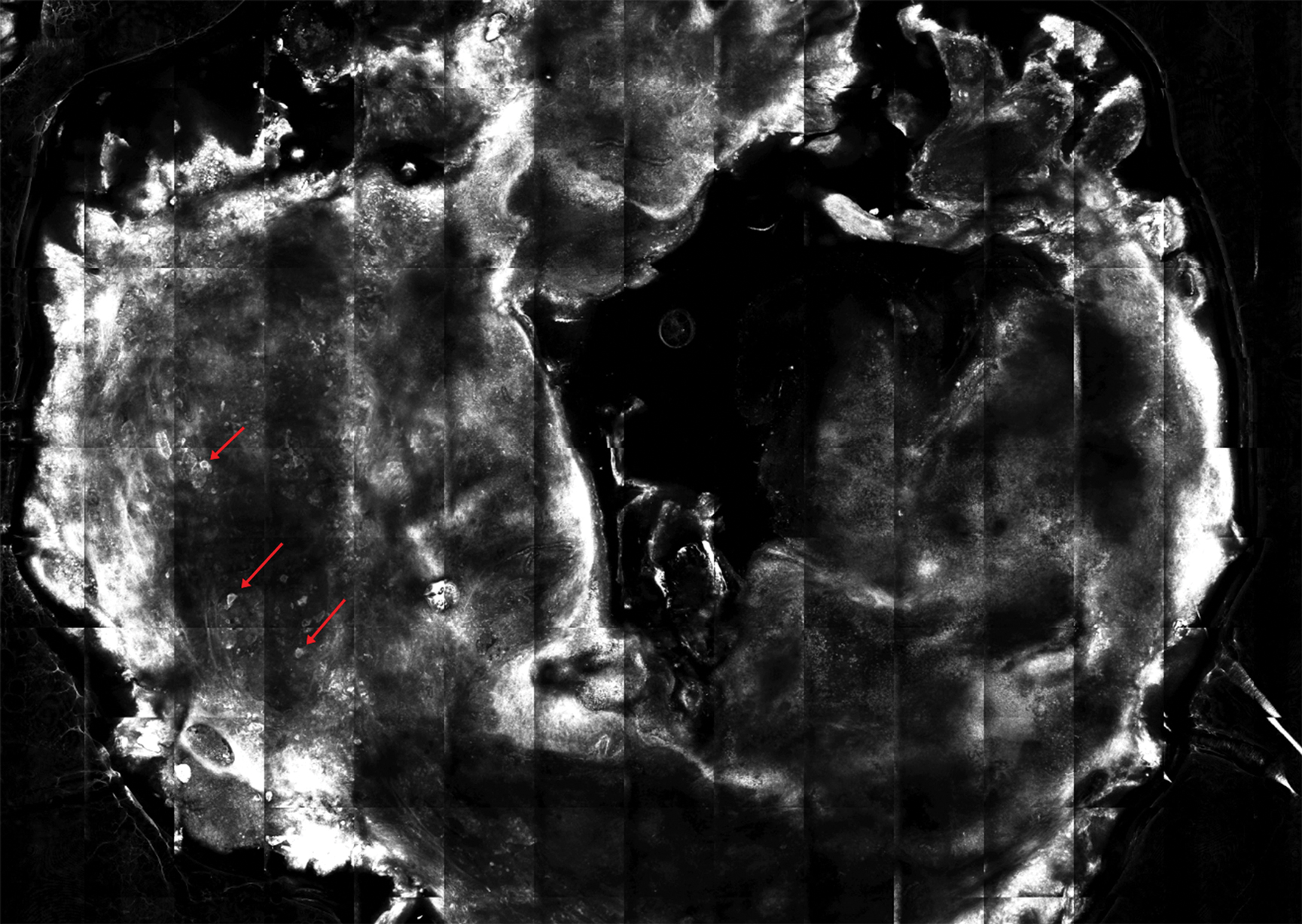

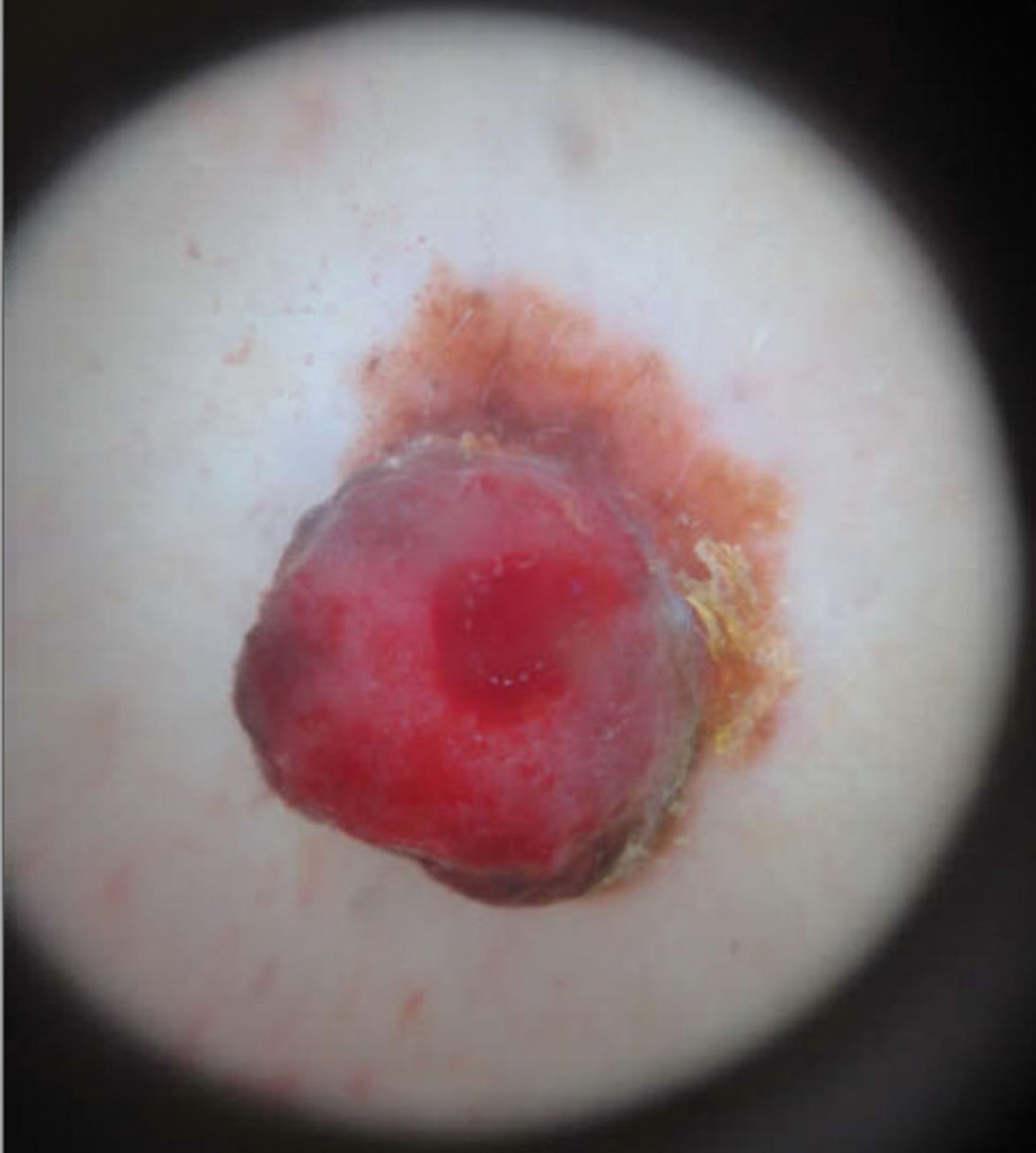

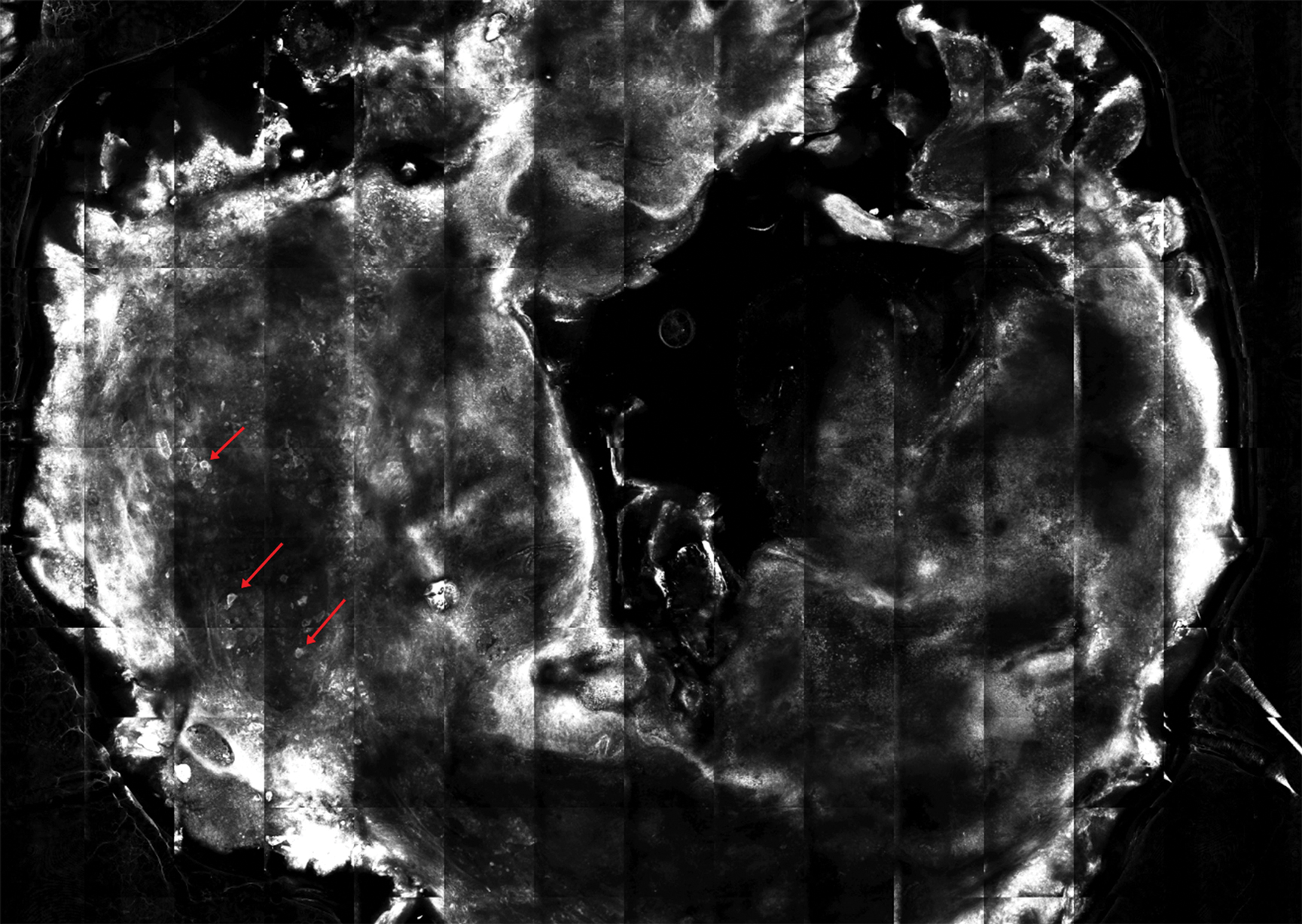

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

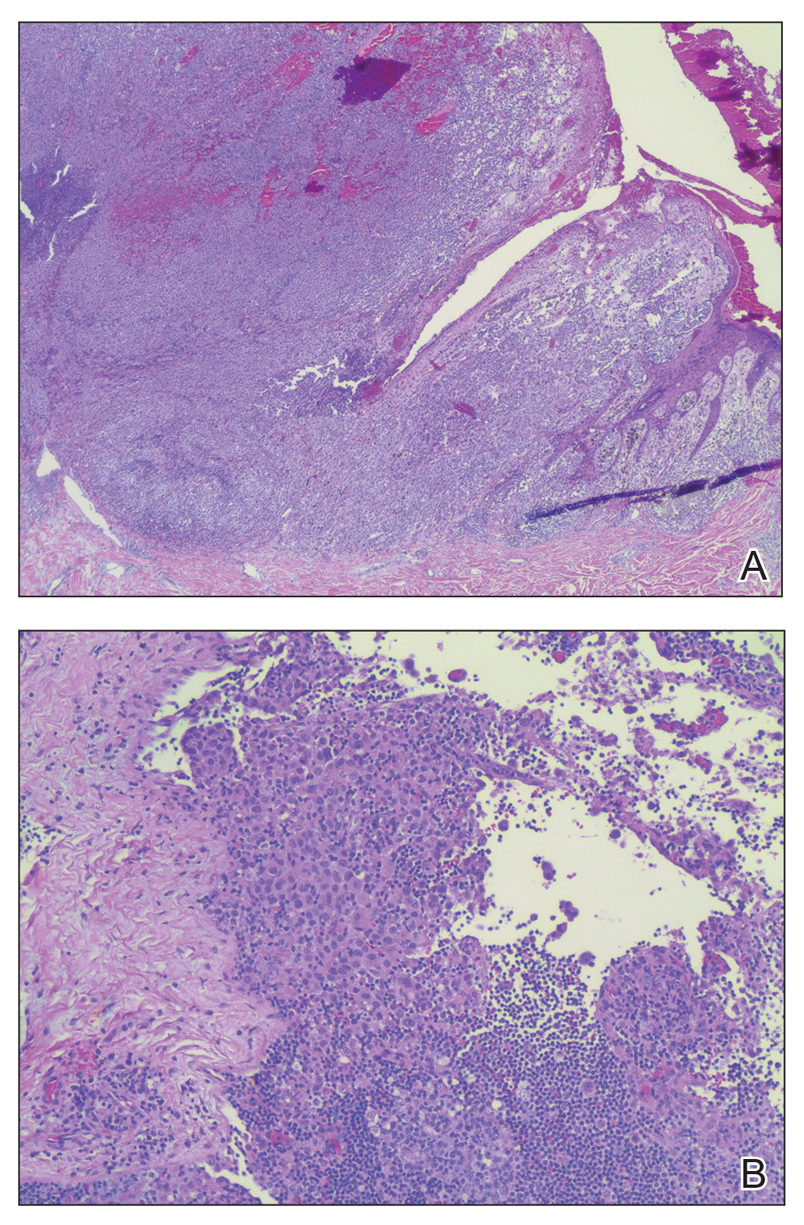

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1