User login

Consider triple therapy for the management of COPD

Background: The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (LABA), and long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (LAMA) for patients with severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations despite treatment with a LABA and LAMA. Triple therapy has been shown to improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), but its effect on preventing exacerbations has not been well documented in previous meta-analyses.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Studies published on PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library website, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and ClinicalTrials.gov databases.

Synopsis: 21 randomized, controlled trials of triple therapy in stable cases of moderate to very severe COPD were included in this meta-analysis. Triple therapy was associated with a significantly greater reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations, compared with dual therapy of LAMA and LABA (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.88), inhaled corticosteroid and LABA (rate ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.91), or LAMA monotherapy (rate ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85). Triple therapy was also associated with greater improvement in FEV1.

There was a significantly higher incidence of pneumonia in patients using triple therapy, compared with those using dual therapy (LAMA and LABA), and there also was a trend toward increased pneumonia incidence with triple therapy, compared with LAMA monotherapy. Triple therapy was not shown to improve survival; however, most trials lasted less than 6 months, which limits their analysis of survival outcomes.

Bottom line: In patients with advanced COPD, triple therapy is associated with lower rates of COPD exacerbations and improved lung function, compared with dual therapy or monotherapy.

Citation: Zheng Y et al. Triple therapy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k4388.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (LABA), and long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (LAMA) for patients with severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations despite treatment with a LABA and LAMA. Triple therapy has been shown to improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), but its effect on preventing exacerbations has not been well documented in previous meta-analyses.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Studies published on PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library website, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and ClinicalTrials.gov databases.

Synopsis: 21 randomized, controlled trials of triple therapy in stable cases of moderate to very severe COPD were included in this meta-analysis. Triple therapy was associated with a significantly greater reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations, compared with dual therapy of LAMA and LABA (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.88), inhaled corticosteroid and LABA (rate ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.91), or LAMA monotherapy (rate ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85). Triple therapy was also associated with greater improvement in FEV1.

There was a significantly higher incidence of pneumonia in patients using triple therapy, compared with those using dual therapy (LAMA and LABA), and there also was a trend toward increased pneumonia incidence with triple therapy, compared with LAMA monotherapy. Triple therapy was not shown to improve survival; however, most trials lasted less than 6 months, which limits their analysis of survival outcomes.

Bottom line: In patients with advanced COPD, triple therapy is associated with lower rates of COPD exacerbations and improved lung function, compared with dual therapy or monotherapy.

Citation: Zheng Y et al. Triple therapy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k4388.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Background: The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends triple therapy with inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists (LABA), and long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (LAMA) for patients with severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations despite treatment with a LABA and LAMA. Triple therapy has been shown to improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), but its effect on preventing exacerbations has not been well documented in previous meta-analyses.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Studies published on PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library website, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and ClinicalTrials.gov databases.

Synopsis: 21 randomized, controlled trials of triple therapy in stable cases of moderate to very severe COPD were included in this meta-analysis. Triple therapy was associated with a significantly greater reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations, compared with dual therapy of LAMA and LABA (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.88), inhaled corticosteroid and LABA (rate ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.91), or LAMA monotherapy (rate ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85). Triple therapy was also associated with greater improvement in FEV1.

There was a significantly higher incidence of pneumonia in patients using triple therapy, compared with those using dual therapy (LAMA and LABA), and there also was a trend toward increased pneumonia incidence with triple therapy, compared with LAMA monotherapy. Triple therapy was not shown to improve survival; however, most trials lasted less than 6 months, which limits their analysis of survival outcomes.

Bottom line: In patients with advanced COPD, triple therapy is associated with lower rates of COPD exacerbations and improved lung function, compared with dual therapy or monotherapy.

Citation: Zheng Y et al. Triple therapy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k4388.

Dr. Chace is an associate physician in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Try testosterone for some women with sexual dysfunction, but not others

A new international position statement on testosterone therapy for women concludes that a trial of testosterone is appropriate for postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire dysfunction (HSDD) and that its use for any other condition, symptom, or reason is not supported by available evidence.

The seven-page position statement, developed by an international task force of experts from the Endocrine Society, the American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, and multiple other medical societies, also emphasized that blood concentrations of testosterone should approximate premenopausal physiological conditions.

“When testosterone therapy is given, the resultant blood levels should not be above those seen in healthy young women,” said lead author Susan Ruth Davis, PhD, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, in a press release issued by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Davis is president of the International Menopause Society, which coordinated the panel.

The statement was published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism and three other medical journals.

Margaret E. Wierman, MD, who represented the Endocrine Society on the task force, said in an interview that there has been “growing concern about testosterone being prescribed for a variety of signs and symptoms without data to support” such use. At the same time, there is significant concern about the ongoing lack of approved formulations licensed specifically for women, she said.

In part, the statement is about a renewed “call to industry to make some [female-specific] formulations so that we can examine other potential roles of testosterone in women,” said Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology at the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Aurora.

“Testosterone may be useful [for indications other than HSDD], but we don’t know. There may be no [breast or cardiovascular disease risk], but we don’t know,” she said. “And without a formulation to study potential benefits and risks, it’s good to be cautious. It’s good to really outline where we have data and where we don’t.”

The Endocrine Society’s 2014 clinical practice guideline on androgen therapy in women, for which Dr. Wierman was the lead author, also recommended against the off-label use of testosterone for sexual dysfunction other than HSDD or for any other reason, such as cognitive, cardiovascular, metabolic, or bone health. As with the new statement, the society’s position statement was guided by an international, multisociety task force, albeit a smaller one.

For the new global position statement, the task force’s review of evidence includes a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial data – of at least 12 weeks’ duration – on the use of testosterone for sexual function, cardiometabolic variables, cognitive measures, and musculoskeletal health. Some of the data from the randomized controlled trials were unpublished.

The meta-analysis, led by Dr. Davis and published in July in the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, found that, compared with placebo or a comparator (such as estrogen, with or without progesterone), testosterone in either oral or transdermal form significantly improved sexual function in postmenopausal women. However, data about the effects of testosterone for other indications, its long-term safety, and its use in premenopausal women, were insufficient for drawing any conclusions (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30189-5).

In addition, testosterone administered orally – but not nonorally (patch or cream) – was associated with adverse lipid profiles, Dr. Davis and her colleagues reported.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis, published in Fertility and Sterility in 2017 and included in the task force’s evidence review, focused specifically on transdermal testosterone for menopausal women with HSDD, with or without estrogen and progestin therapy. It also showed short-term efficacy in terms of improvement in sexual function, as well as short-term safety (Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):475-82).

The new position statement warns about the lack of long-term safety data, stating that “safety data for testosterone in physiologic doses are not available beyond 24 months of treatment.”

In the short term, testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women (in doses approximating testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women), is associated with mild increases in acne and body/facial hair growth in some women, but not with alopecia, clitoromegaly, or voice change. Short-term transdermal therapy also does not seem to affect breast cancer risk or have any significant effects on lipid profiles, the statement says.

The panel points out, however, that randomized controlled trials with testosterone therapy have excluded women who are at high risk of cardiometabolic disease, and that women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer have also been excluded from randomized trials of testosterone in women with HSDD. This is a “big issue,” said Dr. Wierman, and means that recommendations regarding the effect of testosterone in postmenopausal women with HSDD may not be generalizable to possible at-risk subpopulations.

The panel endorsed testosterone therapy specifically for women with HSDD because most of the studies reporting on sexual function have recruited women with diagnosed HSDD. Demonstrated benefits of testosterone in these cases include improved sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pleasure, and reduced concerns and distress about sex. HSDD should be diagnosed after formal biopsychosocial assessment, the statement notes.

“We don’t completely understand the control of sexual function in women, but it’s very dependent on estrogen status. And it’s also dependent on psychosocial factors, emotional health, relationship issues, and physical issues,” Dr. Wierman said in the interview.

“In practice, we look at all these issues, and we first optimize estrogen status. Once that’s done, and we’ve looked at all the other components of sexual function, then we can consider off-label use of testosterone,” she said. “If there’s no response in 3-6 months, we stop it.”

Testosterone levels do not correlate with sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wierman emphasized, and direct assays for the measurement of total and free testosterone are unreliable. The statement acknowledges that but still recommends measurement of testosterone using direct assays, in cases in which liquid/gas chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry assay (which has “high accuracy and reproducibility”) are not available. This is “to exclude high baseline concentrations and also to exclude supraphysiological concentrations during treatment,” the panel said.

Most endocrinologists and other experts who prescribe testosterone therapy for women use an approved male formulation off label and adjust it – an approach that the panel says is reasonable as long as hormone concentrations are “maintained in the physiologic female range.”

Compounded “bioidentical” testosterone therapy “cannot be recommended for the treatment of HSDD because of the lack of evidence for safety and efficacy,” the statement says.

“A big concern of many endocrinologists,” Dr. Wierman added, “is the recent explosion of using pharmacological levels of both estrogen and testosterone in either [injections] or pellets.” The Endocrine Society and other societies have alerted the Food and Drug Administration to “this new cottage industry, which may have significant side effects and risks for our patients,” she said.

Dr. Wierman reported received funding from Corcept Therapeutics, Novartis, and the Cancer League of Colorado, and honoraria or consultation fees from Pfizer to review ASPIRE grant applications for studies of acromegaly as well as Endocrine Society honorarium for teaching in the Endocrine Board Review and Clinical Endocrine Update. Dr. Davis reported receiving funding from a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant, a National Breast Foundation accelerator grant, and the Grollo-Ruzenne Foundation, as well as honoraria from Besins and Pfizer Australia. She has been a consultant to Besins Healthcare, Mayne Pharmaceuticals, Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and Que Oncology. Disclosures for other authors of the position statement are listed with the statement.

SOURCE: Davis SR et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01603.

A new international position statement on testosterone therapy for women concludes that a trial of testosterone is appropriate for postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire dysfunction (HSDD) and that its use for any other condition, symptom, or reason is not supported by available evidence.

The seven-page position statement, developed by an international task force of experts from the Endocrine Society, the American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, and multiple other medical societies, also emphasized that blood concentrations of testosterone should approximate premenopausal physiological conditions.

“When testosterone therapy is given, the resultant blood levels should not be above those seen in healthy young women,” said lead author Susan Ruth Davis, PhD, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, in a press release issued by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Davis is president of the International Menopause Society, which coordinated the panel.

The statement was published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism and three other medical journals.

Margaret E. Wierman, MD, who represented the Endocrine Society on the task force, said in an interview that there has been “growing concern about testosterone being prescribed for a variety of signs and symptoms without data to support” such use. At the same time, there is significant concern about the ongoing lack of approved formulations licensed specifically for women, she said.

In part, the statement is about a renewed “call to industry to make some [female-specific] formulations so that we can examine other potential roles of testosterone in women,” said Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology at the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Aurora.

“Testosterone may be useful [for indications other than HSDD], but we don’t know. There may be no [breast or cardiovascular disease risk], but we don’t know,” she said. “And without a formulation to study potential benefits and risks, it’s good to be cautious. It’s good to really outline where we have data and where we don’t.”

The Endocrine Society’s 2014 clinical practice guideline on androgen therapy in women, for which Dr. Wierman was the lead author, also recommended against the off-label use of testosterone for sexual dysfunction other than HSDD or for any other reason, such as cognitive, cardiovascular, metabolic, or bone health. As with the new statement, the society’s position statement was guided by an international, multisociety task force, albeit a smaller one.

For the new global position statement, the task force’s review of evidence includes a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial data – of at least 12 weeks’ duration – on the use of testosterone for sexual function, cardiometabolic variables, cognitive measures, and musculoskeletal health. Some of the data from the randomized controlled trials were unpublished.

The meta-analysis, led by Dr. Davis and published in July in the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, found that, compared with placebo or a comparator (such as estrogen, with or without progesterone), testosterone in either oral or transdermal form significantly improved sexual function in postmenopausal women. However, data about the effects of testosterone for other indications, its long-term safety, and its use in premenopausal women, were insufficient for drawing any conclusions (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30189-5).

In addition, testosterone administered orally – but not nonorally (patch or cream) – was associated with adverse lipid profiles, Dr. Davis and her colleagues reported.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis, published in Fertility and Sterility in 2017 and included in the task force’s evidence review, focused specifically on transdermal testosterone for menopausal women with HSDD, with or without estrogen and progestin therapy. It also showed short-term efficacy in terms of improvement in sexual function, as well as short-term safety (Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):475-82).

The new position statement warns about the lack of long-term safety data, stating that “safety data for testosterone in physiologic doses are not available beyond 24 months of treatment.”

In the short term, testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women (in doses approximating testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women), is associated with mild increases in acne and body/facial hair growth in some women, but not with alopecia, clitoromegaly, or voice change. Short-term transdermal therapy also does not seem to affect breast cancer risk or have any significant effects on lipid profiles, the statement says.

The panel points out, however, that randomized controlled trials with testosterone therapy have excluded women who are at high risk of cardiometabolic disease, and that women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer have also been excluded from randomized trials of testosterone in women with HSDD. This is a “big issue,” said Dr. Wierman, and means that recommendations regarding the effect of testosterone in postmenopausal women with HSDD may not be generalizable to possible at-risk subpopulations.

The panel endorsed testosterone therapy specifically for women with HSDD because most of the studies reporting on sexual function have recruited women with diagnosed HSDD. Demonstrated benefits of testosterone in these cases include improved sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pleasure, and reduced concerns and distress about sex. HSDD should be diagnosed after formal biopsychosocial assessment, the statement notes.

“We don’t completely understand the control of sexual function in women, but it’s very dependent on estrogen status. And it’s also dependent on psychosocial factors, emotional health, relationship issues, and physical issues,” Dr. Wierman said in the interview.

“In practice, we look at all these issues, and we first optimize estrogen status. Once that’s done, and we’ve looked at all the other components of sexual function, then we can consider off-label use of testosterone,” she said. “If there’s no response in 3-6 months, we stop it.”

Testosterone levels do not correlate with sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wierman emphasized, and direct assays for the measurement of total and free testosterone are unreliable. The statement acknowledges that but still recommends measurement of testosterone using direct assays, in cases in which liquid/gas chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry assay (which has “high accuracy and reproducibility”) are not available. This is “to exclude high baseline concentrations and also to exclude supraphysiological concentrations during treatment,” the panel said.

Most endocrinologists and other experts who prescribe testosterone therapy for women use an approved male formulation off label and adjust it – an approach that the panel says is reasonable as long as hormone concentrations are “maintained in the physiologic female range.”

Compounded “bioidentical” testosterone therapy “cannot be recommended for the treatment of HSDD because of the lack of evidence for safety and efficacy,” the statement says.

“A big concern of many endocrinologists,” Dr. Wierman added, “is the recent explosion of using pharmacological levels of both estrogen and testosterone in either [injections] or pellets.” The Endocrine Society and other societies have alerted the Food and Drug Administration to “this new cottage industry, which may have significant side effects and risks for our patients,” she said.

Dr. Wierman reported received funding from Corcept Therapeutics, Novartis, and the Cancer League of Colorado, and honoraria or consultation fees from Pfizer to review ASPIRE grant applications for studies of acromegaly as well as Endocrine Society honorarium for teaching in the Endocrine Board Review and Clinical Endocrine Update. Dr. Davis reported receiving funding from a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant, a National Breast Foundation accelerator grant, and the Grollo-Ruzenne Foundation, as well as honoraria from Besins and Pfizer Australia. She has been a consultant to Besins Healthcare, Mayne Pharmaceuticals, Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and Que Oncology. Disclosures for other authors of the position statement are listed with the statement.

SOURCE: Davis SR et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01603.

A new international position statement on testosterone therapy for women concludes that a trial of testosterone is appropriate for postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire dysfunction (HSDD) and that its use for any other condition, symptom, or reason is not supported by available evidence.

The seven-page position statement, developed by an international task force of experts from the Endocrine Society, the American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, and multiple other medical societies, also emphasized that blood concentrations of testosterone should approximate premenopausal physiological conditions.

“When testosterone therapy is given, the resultant blood levels should not be above those seen in healthy young women,” said lead author Susan Ruth Davis, PhD, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, in a press release issued by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Davis is president of the International Menopause Society, which coordinated the panel.

The statement was published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism and three other medical journals.

Margaret E. Wierman, MD, who represented the Endocrine Society on the task force, said in an interview that there has been “growing concern about testosterone being prescribed for a variety of signs and symptoms without data to support” such use. At the same time, there is significant concern about the ongoing lack of approved formulations licensed specifically for women, she said.

In part, the statement is about a renewed “call to industry to make some [female-specific] formulations so that we can examine other potential roles of testosterone in women,” said Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology at the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Aurora.

“Testosterone may be useful [for indications other than HSDD], but we don’t know. There may be no [breast or cardiovascular disease risk], but we don’t know,” she said. “And without a formulation to study potential benefits and risks, it’s good to be cautious. It’s good to really outline where we have data and where we don’t.”

The Endocrine Society’s 2014 clinical practice guideline on androgen therapy in women, for which Dr. Wierman was the lead author, also recommended against the off-label use of testosterone for sexual dysfunction other than HSDD or for any other reason, such as cognitive, cardiovascular, metabolic, or bone health. As with the new statement, the society’s position statement was guided by an international, multisociety task force, albeit a smaller one.

For the new global position statement, the task force’s review of evidence includes a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial data – of at least 12 weeks’ duration – on the use of testosterone for sexual function, cardiometabolic variables, cognitive measures, and musculoskeletal health. Some of the data from the randomized controlled trials were unpublished.

The meta-analysis, led by Dr. Davis and published in July in the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, found that, compared with placebo or a comparator (such as estrogen, with or without progesterone), testosterone in either oral or transdermal form significantly improved sexual function in postmenopausal women. However, data about the effects of testosterone for other indications, its long-term safety, and its use in premenopausal women, were insufficient for drawing any conclusions (Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587[19]30189-5).

In addition, testosterone administered orally – but not nonorally (patch or cream) – was associated with adverse lipid profiles, Dr. Davis and her colleagues reported.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis, published in Fertility and Sterility in 2017 and included in the task force’s evidence review, focused specifically on transdermal testosterone for menopausal women with HSDD, with or without estrogen and progestin therapy. It also showed short-term efficacy in terms of improvement in sexual function, as well as short-term safety (Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):475-82).

The new position statement warns about the lack of long-term safety data, stating that “safety data for testosterone in physiologic doses are not available beyond 24 months of treatment.”

In the short term, testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women (in doses approximating testosterone concentrations for premenopausal women), is associated with mild increases in acne and body/facial hair growth in some women, but not with alopecia, clitoromegaly, or voice change. Short-term transdermal therapy also does not seem to affect breast cancer risk or have any significant effects on lipid profiles, the statement says.

The panel points out, however, that randomized controlled trials with testosterone therapy have excluded women who are at high risk of cardiometabolic disease, and that women with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer have also been excluded from randomized trials of testosterone in women with HSDD. This is a “big issue,” said Dr. Wierman, and means that recommendations regarding the effect of testosterone in postmenopausal women with HSDD may not be generalizable to possible at-risk subpopulations.

The panel endorsed testosterone therapy specifically for women with HSDD because most of the studies reporting on sexual function have recruited women with diagnosed HSDD. Demonstrated benefits of testosterone in these cases include improved sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pleasure, and reduced concerns and distress about sex. HSDD should be diagnosed after formal biopsychosocial assessment, the statement notes.

“We don’t completely understand the control of sexual function in women, but it’s very dependent on estrogen status. And it’s also dependent on psychosocial factors, emotional health, relationship issues, and physical issues,” Dr. Wierman said in the interview.

“In practice, we look at all these issues, and we first optimize estrogen status. Once that’s done, and we’ve looked at all the other components of sexual function, then we can consider off-label use of testosterone,” she said. “If there’s no response in 3-6 months, we stop it.”

Testosterone levels do not correlate with sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wierman emphasized, and direct assays for the measurement of total and free testosterone are unreliable. The statement acknowledges that but still recommends measurement of testosterone using direct assays, in cases in which liquid/gas chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry assay (which has “high accuracy and reproducibility”) are not available. This is “to exclude high baseline concentrations and also to exclude supraphysiological concentrations during treatment,” the panel said.

Most endocrinologists and other experts who prescribe testosterone therapy for women use an approved male formulation off label and adjust it – an approach that the panel says is reasonable as long as hormone concentrations are “maintained in the physiologic female range.”

Compounded “bioidentical” testosterone therapy “cannot be recommended for the treatment of HSDD because of the lack of evidence for safety and efficacy,” the statement says.

“A big concern of many endocrinologists,” Dr. Wierman added, “is the recent explosion of using pharmacological levels of both estrogen and testosterone in either [injections] or pellets.” The Endocrine Society and other societies have alerted the Food and Drug Administration to “this new cottage industry, which may have significant side effects and risks for our patients,” she said.

Dr. Wierman reported received funding from Corcept Therapeutics, Novartis, and the Cancer League of Colorado, and honoraria or consultation fees from Pfizer to review ASPIRE grant applications for studies of acromegaly as well as Endocrine Society honorarium for teaching in the Endocrine Board Review and Clinical Endocrine Update. Dr. Davis reported receiving funding from a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant, a National Breast Foundation accelerator grant, and the Grollo-Ruzenne Foundation, as well as honoraria from Besins and Pfizer Australia. She has been a consultant to Besins Healthcare, Mayne Pharmaceuticals, Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and Que Oncology. Disclosures for other authors of the position statement are listed with the statement.

SOURCE: Davis SR et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01603.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Solitary Papule on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

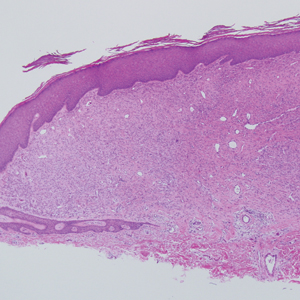

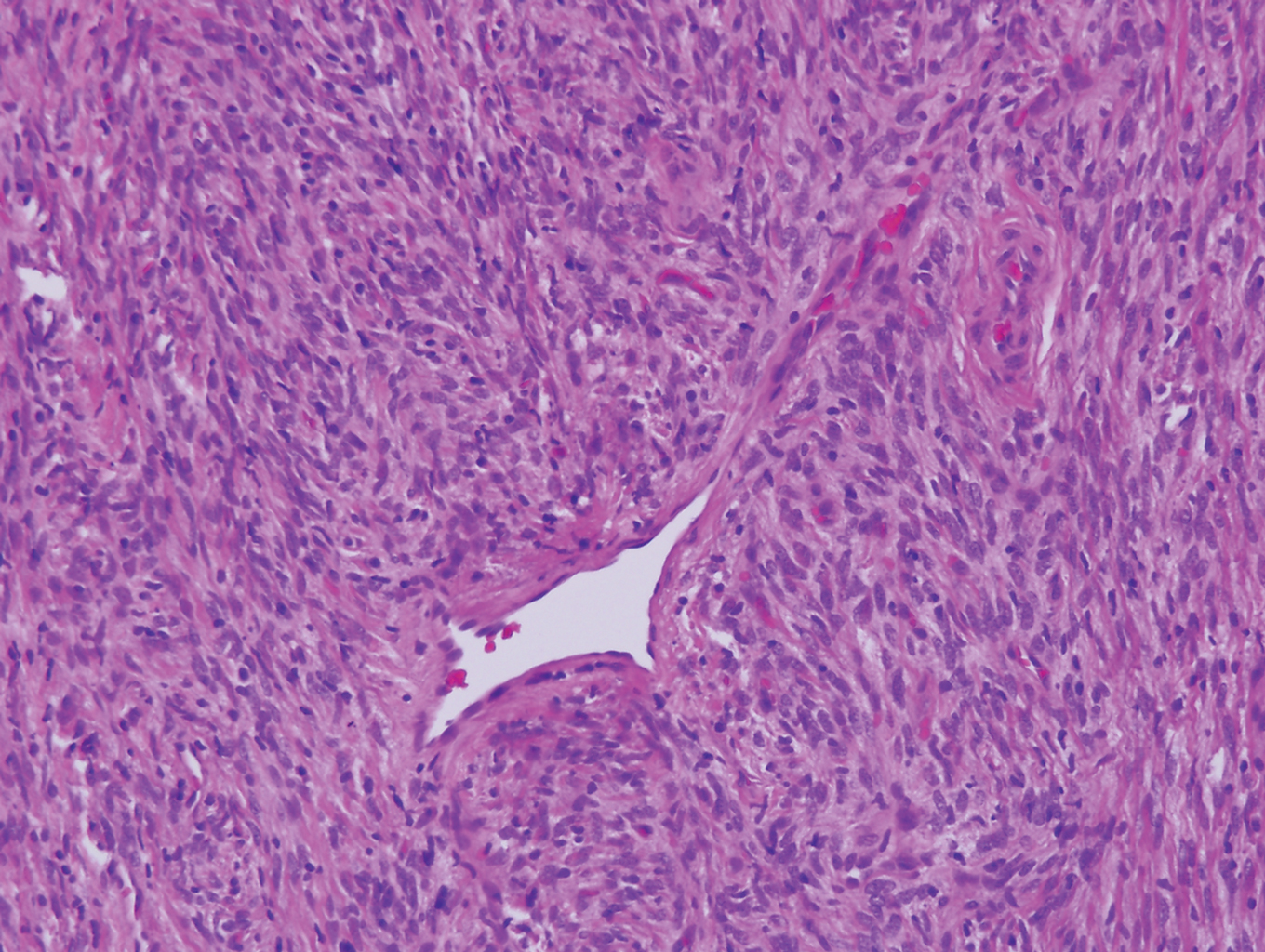

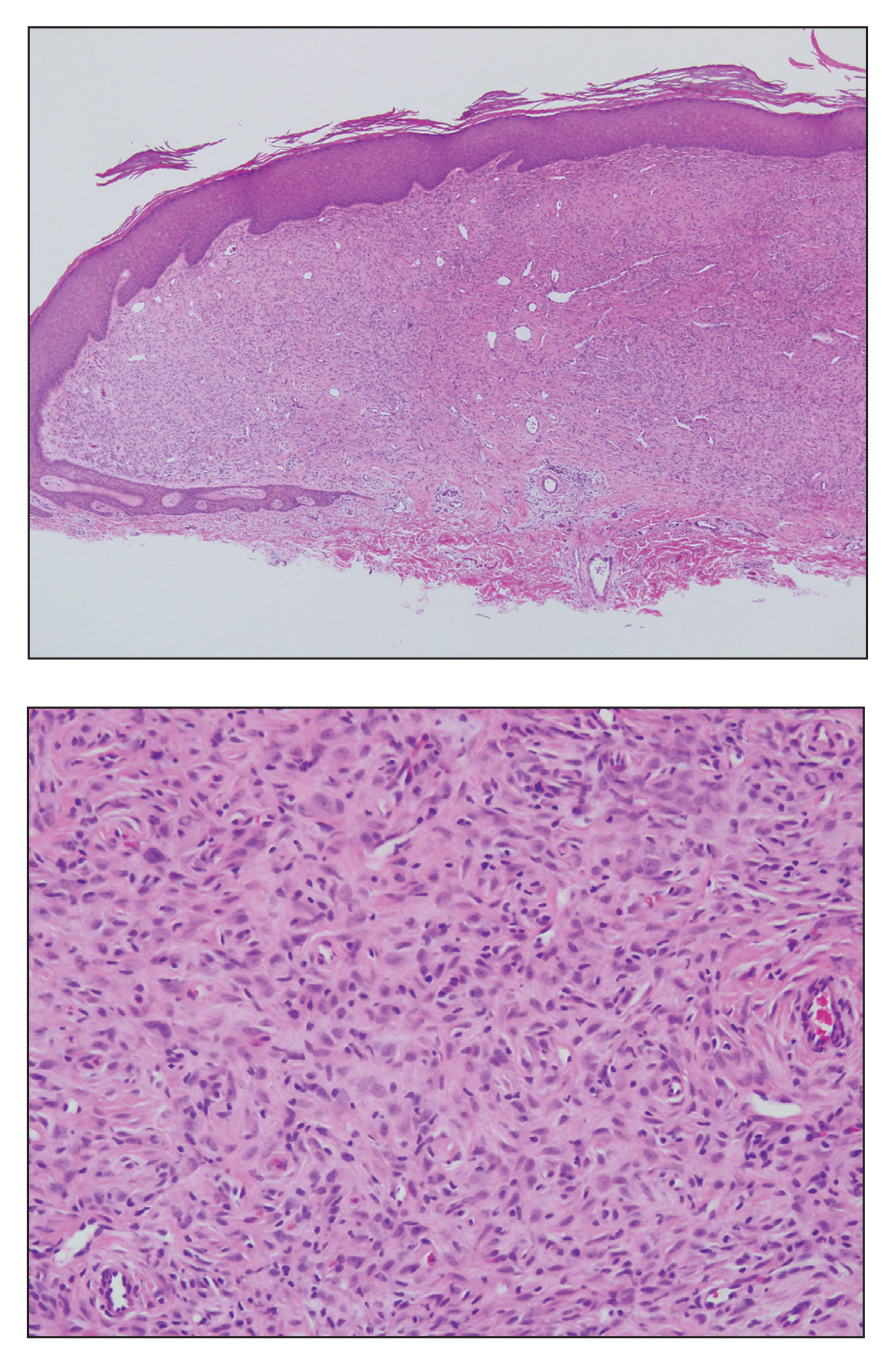

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

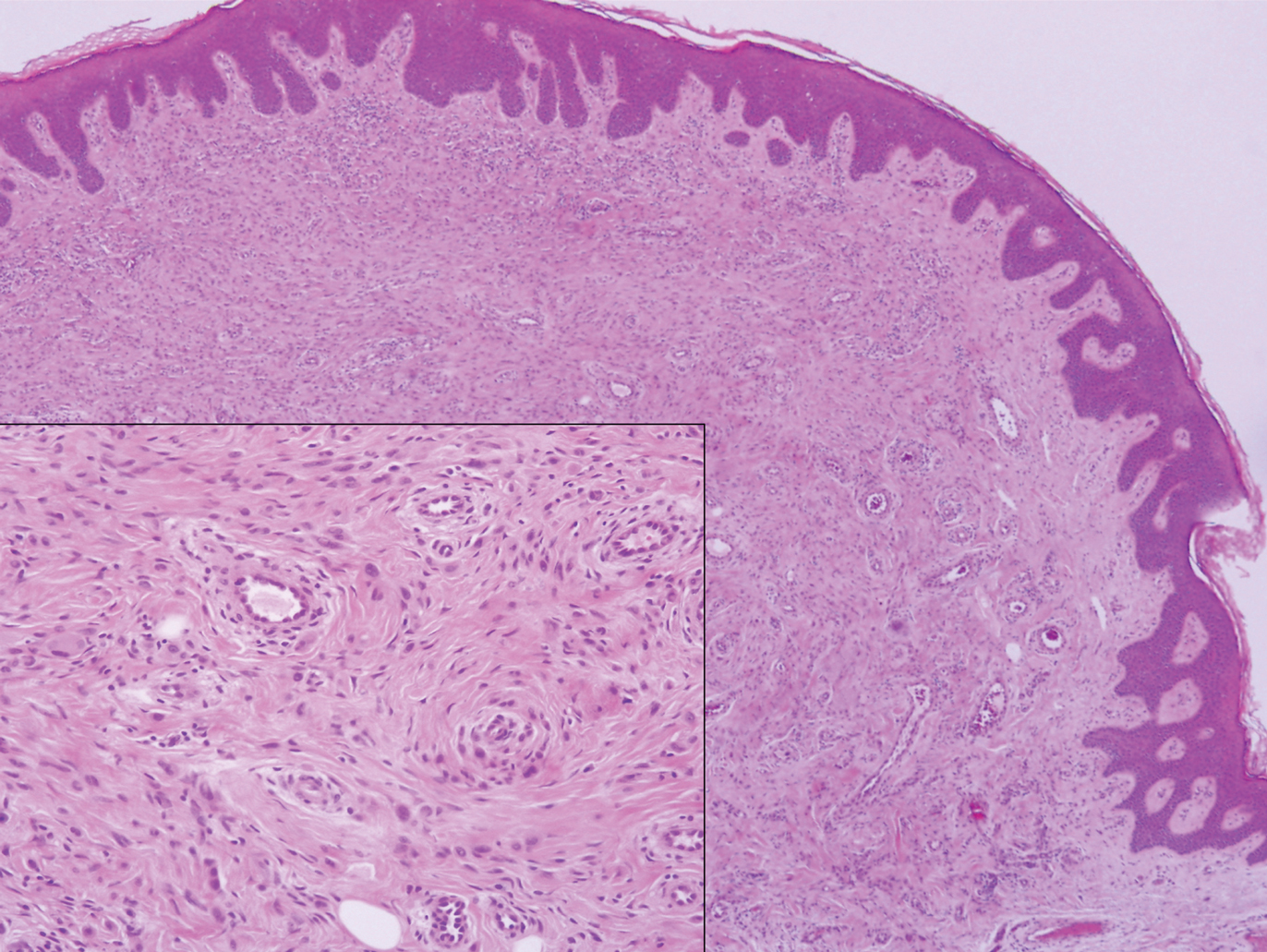

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

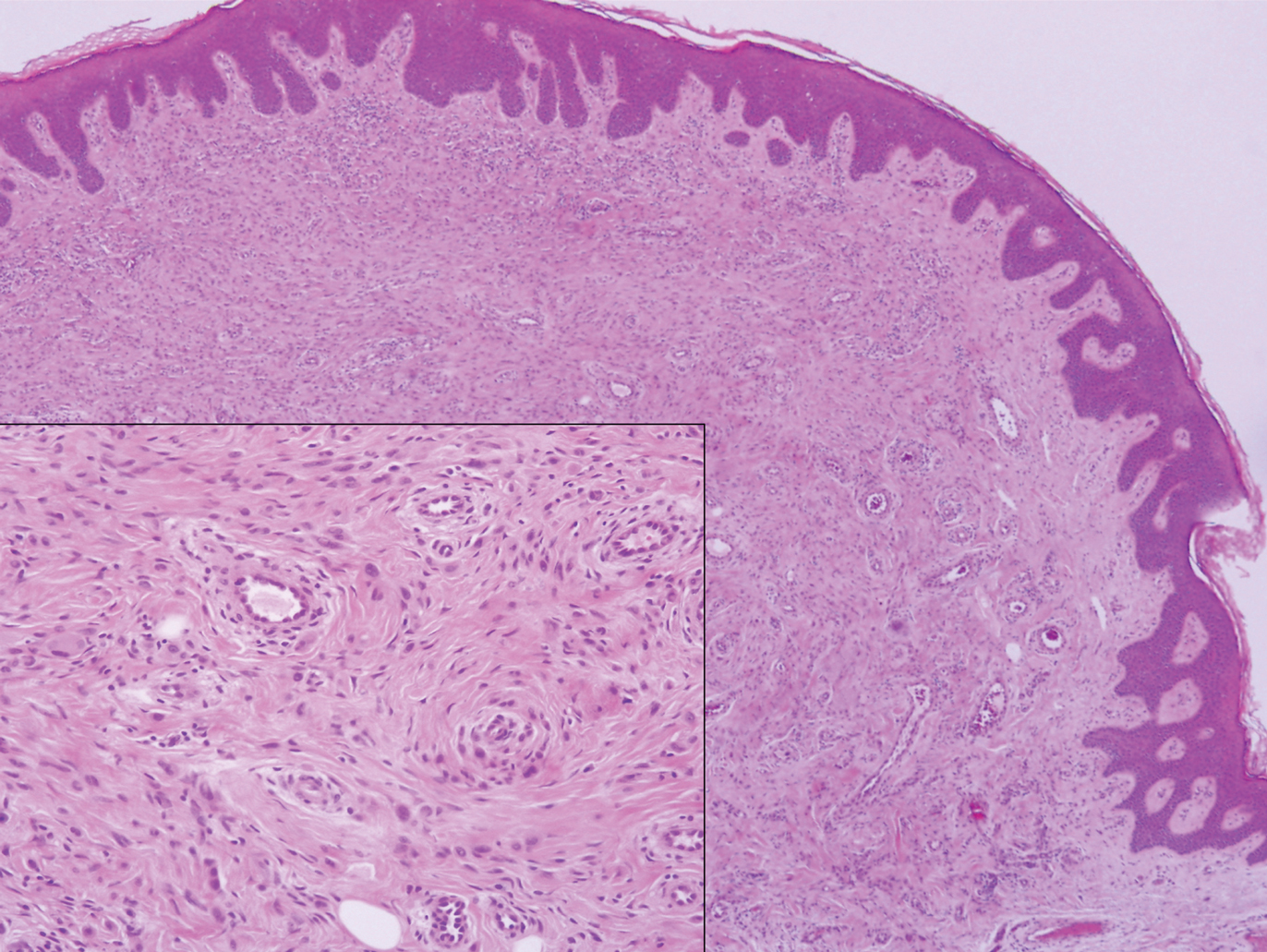

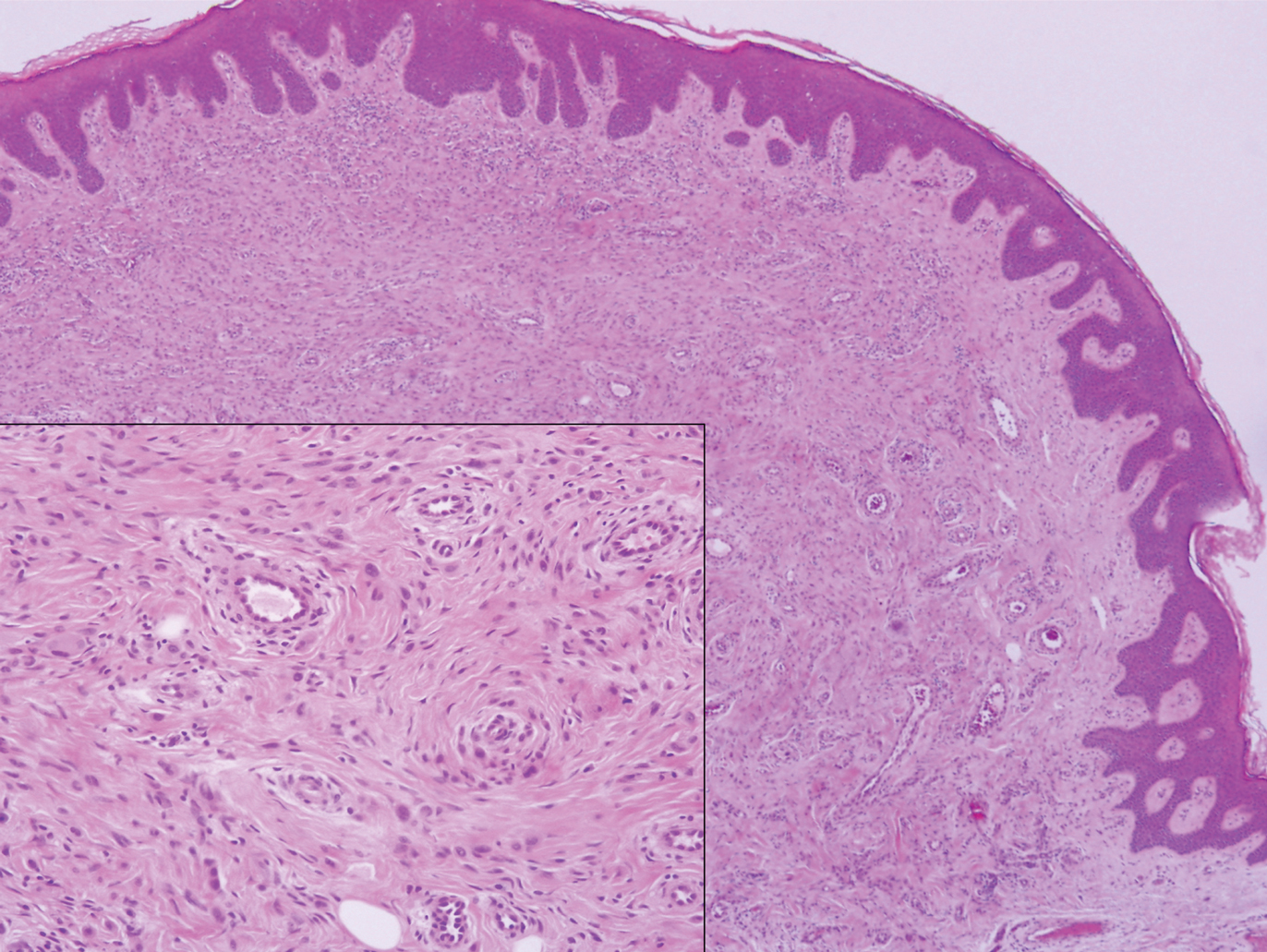

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

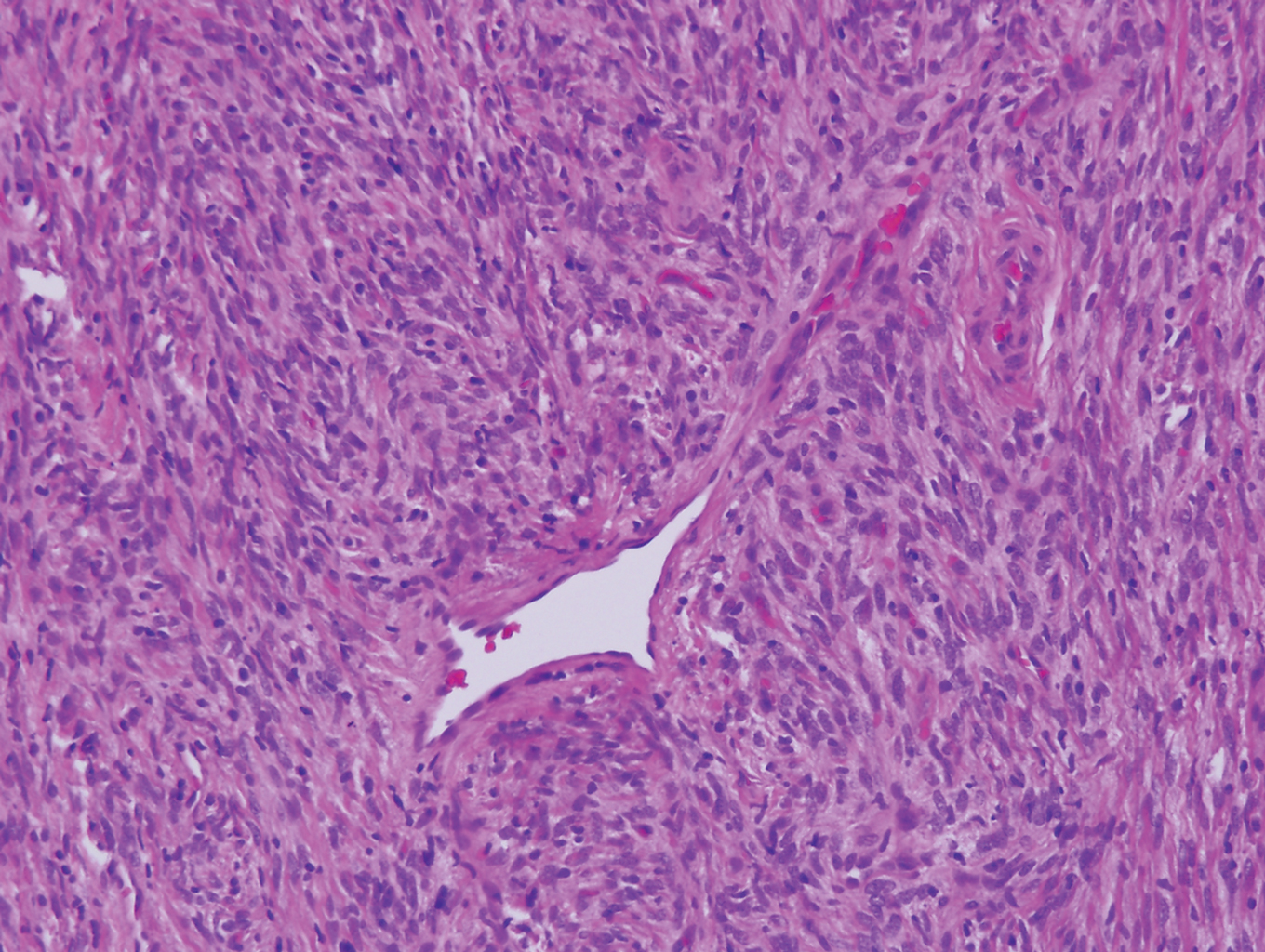

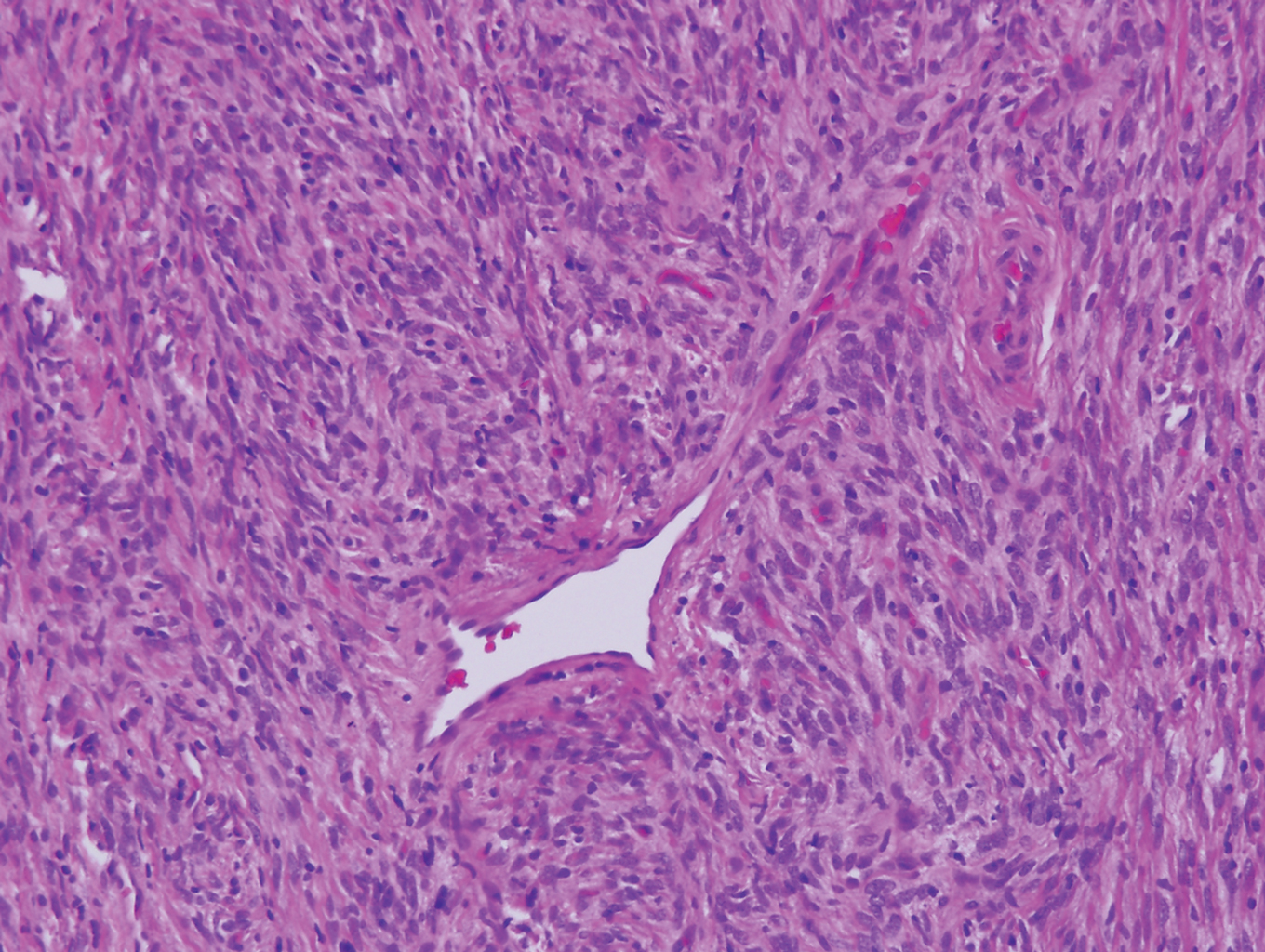

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

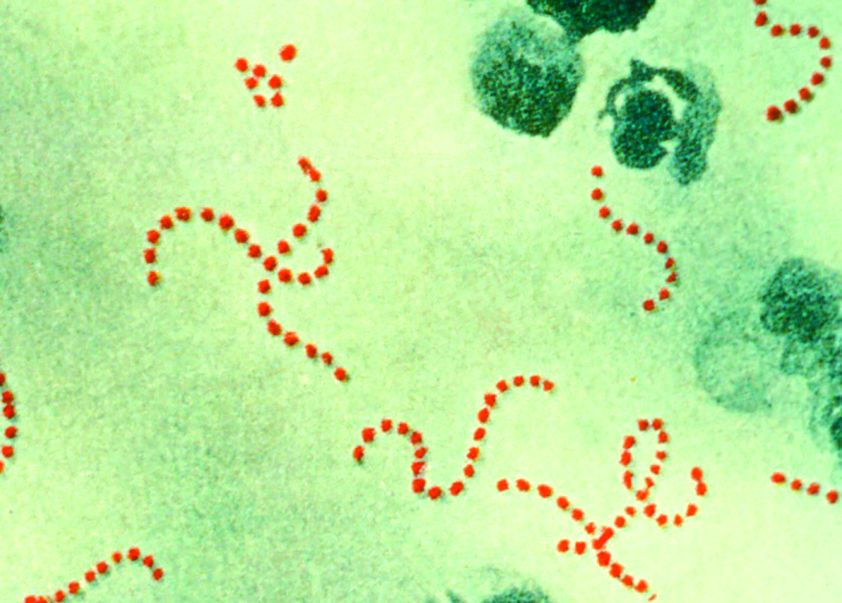

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

A 28-year-old man presented with a growing asymptomatic papule on the right leg.

Ankylosing spondylitis severity, comorbidities higher in blacks than in whites

While ankylosing spondylitis may be more common among whites, black patients have more comorbidities and express higher disease activity, Dilpreet Kaur Singh, MD, and Marina Magrey, MBBS, reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

A retrospective review of a large U.S. medical database conducted by Dr. Singh and Dr. Magrey of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, found that black patients had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein, and a higher prevalence of anterior uveitis, hypertension, diabetes, and depression, compared with white patients. (Dr. Singh, who was a rheumatology fellow at MetroHealth at the time of the study, is now a practicing rheumatologist in Springfield, Mass.)

Disease severity in AS is “thought to be genetically mediated but cultural, social, or economic factors may also be contributing to this racial disparity,” the investigators wrote. “Further research is needed to determine the role of factors other than genetic factors like HLA-B27 positivity that contribute to worsening disease severity.”

The authors extracted data recorded during 1999-2017 from the Explorys platform, a clinical research informatics tool with data from more than 50 million patients in 26 major integrated health care systems in the United States.

The current study comprised 10,990 AS patients with at least two visits to a rheumatologist. Most (84%) were white; 8% were black. Sex was equally distributed in both groups. Positivity for HLA-B27 was similar among whites (26%) and blacks (20%). A majority of patients smoked (65%), and smoking was more common among whites than among blacks (67% vs. 59%).

Disease characteristics suggested that AS was more severe among blacks. Significantly greater proportions of black patients had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (62% vs. 48% of whites) and C-reactive protein (68% vs. 54%). Blacks also experienced significantly greater rates of anterior uveitis (8% vs. 4%), hypertension (29% vs. 22%), diabetes (27% vs. 17%), and depression (36% vs. 32%).

Blacks experienced higher rates of peripheral arthritis, enthesopathy, dactylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease, although these differences were not statistically significant when compared with whites.

Whites, however, had significantly higher rates of psoriasis (10% vs. 6.5%).

Most of the cohort (87%) received NSAIDs; 39% used tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. There were no significant between-group treatment differences.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest and no source of financial support.

SOURCE: Singh DK et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181019.

While ankylosing spondylitis may be more common among whites, black patients have more comorbidities and express higher disease activity, Dilpreet Kaur Singh, MD, and Marina Magrey, MBBS, reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

A retrospective review of a large U.S. medical database conducted by Dr. Singh and Dr. Magrey of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, found that black patients had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein, and a higher prevalence of anterior uveitis, hypertension, diabetes, and depression, compared with white patients. (Dr. Singh, who was a rheumatology fellow at MetroHealth at the time of the study, is now a practicing rheumatologist in Springfield, Mass.)

Disease severity in AS is “thought to be genetically mediated but cultural, social, or economic factors may also be contributing to this racial disparity,” the investigators wrote. “Further research is needed to determine the role of factors other than genetic factors like HLA-B27 positivity that contribute to worsening disease severity.”

The authors extracted data recorded during 1999-2017 from the Explorys platform, a clinical research informatics tool with data from more than 50 million patients in 26 major integrated health care systems in the United States.

The current study comprised 10,990 AS patients with at least two visits to a rheumatologist. Most (84%) were white; 8% were black. Sex was equally distributed in both groups. Positivity for HLA-B27 was similar among whites (26%) and blacks (20%). A majority of patients smoked (65%), and smoking was more common among whites than among blacks (67% vs. 59%).

Disease characteristics suggested that AS was more severe among blacks. Significantly greater proportions of black patients had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (62% vs. 48% of whites) and C-reactive protein (68% vs. 54%). Blacks also experienced significantly greater rates of anterior uveitis (8% vs. 4%), hypertension (29% vs. 22%), diabetes (27% vs. 17%), and depression (36% vs. 32%).

Blacks experienced higher rates of peripheral arthritis, enthesopathy, dactylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease, although these differences were not statistically significant when compared with whites.

Whites, however, had significantly higher rates of psoriasis (10% vs. 6.5%).

Most of the cohort (87%) received NSAIDs; 39% used tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. There were no significant between-group treatment differences.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest and no source of financial support.

SOURCE: Singh DK et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181019.

While ankylosing spondylitis may be more common among whites, black patients have more comorbidities and express higher disease activity, Dilpreet Kaur Singh, MD, and Marina Magrey, MBBS, reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

A retrospective review of a large U.S. medical database conducted by Dr. Singh and Dr. Magrey of MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, found that black patients had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates and C-reactive protein, and a higher prevalence of anterior uveitis, hypertension, diabetes, and depression, compared with white patients. (Dr. Singh, who was a rheumatology fellow at MetroHealth at the time of the study, is now a practicing rheumatologist in Springfield, Mass.)

Disease severity in AS is “thought to be genetically mediated but cultural, social, or economic factors may also be contributing to this racial disparity,” the investigators wrote. “Further research is needed to determine the role of factors other than genetic factors like HLA-B27 positivity that contribute to worsening disease severity.”

The authors extracted data recorded during 1999-2017 from the Explorys platform, a clinical research informatics tool with data from more than 50 million patients in 26 major integrated health care systems in the United States.

The current study comprised 10,990 AS patients with at least two visits to a rheumatologist. Most (84%) were white; 8% were black. Sex was equally distributed in both groups. Positivity for HLA-B27 was similar among whites (26%) and blacks (20%). A majority of patients smoked (65%), and smoking was more common among whites than among blacks (67% vs. 59%).

Disease characteristics suggested that AS was more severe among blacks. Significantly greater proportions of black patients had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (62% vs. 48% of whites) and C-reactive protein (68% vs. 54%). Blacks also experienced significantly greater rates of anterior uveitis (8% vs. 4%), hypertension (29% vs. 22%), diabetes (27% vs. 17%), and depression (36% vs. 32%).

Blacks experienced higher rates of peripheral arthritis, enthesopathy, dactylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease, although these differences were not statistically significant when compared with whites.

Whites, however, had significantly higher rates of psoriasis (10% vs. 6.5%).

Most of the cohort (87%) received NSAIDs; 39% used tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. There were no significant between-group treatment differences.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest and no source of financial support.

SOURCE: Singh DK et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181019.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

For trans children, early gender ID conversion efforts damage lifelong mental health

Gender identity conversion efforts during early childhood quadruple lifetime risk of suicidal behavior for transgender people, a study of almost 28,000 adults has determined.

The findings prompted the authors to issue a blanket warning against the controversial treatment, which already has been decried by several medical associations.

“Our results support policy positions … which state that gender identity–conversion therapy should not be conducted for transgender patients at any age, Jack L. Turban, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Psychiatry.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Medical Association all strongly warn against any kind of gender conversion efforts.

The significantly increased risk of suicidal behavior was similar whether the gender identity–conversion effort (GICE) was administered by a clinician or a cleric. “This suggests that any process of intervening to alter gender identity is associated with poorer mental health regardless of whether the intervention occurred within a secular or religious framework,” wrote Dr. Turban of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

The study – the largest of its kind thus far – comprised 27,715 transgender adults included in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

In the current study, investigators focused on the question: “Did any professional (such as a psychologist, counselor, or religious advisor) try to make you identify only with your sex assigned at birth (in other words, try to stop you being trans)?”

They compared responses among subjects who reported exposure to GICE before age 10 years with those who did not.

Subjects were aged a mean of 31 years when they participated in the survey. Slightly less than half (42.8%) were assigned male sex at birth. Most (19,751) had discussed their gender identity with a professional. Nearly 20% (3,869) reported some exposure to GICE; 35% said a religious adviser had conducted the effort.

In this group, exposure had significant negative lifetime effects on mental health. These subjects were at a 56% increased risk of psychological distress within the month before taking the survey (odds ratio, 1.56), and more than twice as likely to have tried at least once to end their lives by suicide (OR, 2.27).

But the negative effects were even more pronounced among the small group of 206 who reported exposure to GICE before they were 10 years old. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for demographics, GICE before age 10 more than quadrupled the risk of lifetime suicide attempts (OR, 4.15). Again, it didn’t matter whether a medical or religious professional administered GICE.

“A plausible association of these practices with poor mental health outcomes can be conceptualized through the minority stress framework; that is, elevated stigma-related stress from exposure to GICE may increase general emotion dysregulation, interpersonal dysfunction, and maladaptive cognitions,” the investigators wrote. “Although this study suggests that exposure to GICE is associated with increased odds of suicide attempts, GICE are not the only way in which minority group stress manifests, and thus, other factors are also likely to be associated with suicidality among gender-diverse people.”

“One potential explanation for this is that, compared with persons in the sexual-minority group, many persons in the gender-minority group must interact with clinical professionals to be medically and surgically affirmed in their identities. This higher prevalence of interactions with clinical professionals among people in the gender minority group may lead to greater risk of experiencing conversion effort.”

The authors cited the sample size of the study as one of its many strengths. One limitation includes the study’s cross-sectional design.

Dr. Turban reported collecting royalties from Springer for an upcoming textbook about pediatric gender identity. The other coauthors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Turban JL et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2285.

Gender identity conversion efforts during early childhood quadruple lifetime risk of suicidal behavior for transgender people, a study of almost 28,000 adults has determined.

The findings prompted the authors to issue a blanket warning against the controversial treatment, which already has been decried by several medical associations.

“Our results support policy positions … which state that gender identity–conversion therapy should not be conducted for transgender patients at any age, Jack L. Turban, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Psychiatry.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Medical Association all strongly warn against any kind of gender conversion efforts.

The significantly increased risk of suicidal behavior was similar whether the gender identity–conversion effort (GICE) was administered by a clinician or a cleric. “This suggests that any process of intervening to alter gender identity is associated with poorer mental health regardless of whether the intervention occurred within a secular or religious framework,” wrote Dr. Turban of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

The study – the largest of its kind thus far – comprised 27,715 transgender adults included in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

In the current study, investigators focused on the question: “Did any professional (such as a psychologist, counselor, or religious advisor) try to make you identify only with your sex assigned at birth (in other words, try to stop you being trans)?”

They compared responses among subjects who reported exposure to GICE before age 10 years with those who did not.

Subjects were aged a mean of 31 years when they participated in the survey. Slightly less than half (42.8%) were assigned male sex at birth. Most (19,751) had discussed their gender identity with a professional. Nearly 20% (3,869) reported some exposure to GICE; 35% said a religious adviser had conducted the effort.

In this group, exposure had significant negative lifetime effects on mental health. These subjects were at a 56% increased risk of psychological distress within the month before taking the survey (odds ratio, 1.56), and more than twice as likely to have tried at least once to end their lives by suicide (OR, 2.27).

But the negative effects were even more pronounced among the small group of 206 who reported exposure to GICE before they were 10 years old. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for demographics, GICE before age 10 more than quadrupled the risk of lifetime suicide attempts (OR, 4.15). Again, it didn’t matter whether a medical or religious professional administered GICE.

“A plausible association of these practices with poor mental health outcomes can be conceptualized through the minority stress framework; that is, elevated stigma-related stress from exposure to GICE may increase general emotion dysregulation, interpersonal dysfunction, and maladaptive cognitions,” the investigators wrote. “Although this study suggests that exposure to GICE is associated with increased odds of suicide attempts, GICE are not the only way in which minority group stress manifests, and thus, other factors are also likely to be associated with suicidality among gender-diverse people.”

“One potential explanation for this is that, compared with persons in the sexual-minority group, many persons in the gender-minority group must interact with clinical professionals to be medically and surgically affirmed in their identities. This higher prevalence of interactions with clinical professionals among people in the gender minority group may lead to greater risk of experiencing conversion effort.”

The authors cited the sample size of the study as one of its many strengths. One limitation includes the study’s cross-sectional design.

Dr. Turban reported collecting royalties from Springer for an upcoming textbook about pediatric gender identity. The other coauthors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Turban JL et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2285.

Gender identity conversion efforts during early childhood quadruple lifetime risk of suicidal behavior for transgender people, a study of almost 28,000 adults has determined.

The findings prompted the authors to issue a blanket warning against the controversial treatment, which already has been decried by several medical associations.

“Our results support policy positions … which state that gender identity–conversion therapy should not be conducted for transgender patients at any age, Jack L. Turban, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Psychiatry.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Medical Association all strongly warn against any kind of gender conversion efforts.

The significantly increased risk of suicidal behavior was similar whether the gender identity–conversion effort (GICE) was administered by a clinician or a cleric. “This suggests that any process of intervening to alter gender identity is associated with poorer mental health regardless of whether the intervention occurred within a secular or religious framework,” wrote Dr. Turban of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and coauthors.

The study – the largest of its kind thus far – comprised 27,715 transgender adults included in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

In the current study, investigators focused on the question: “Did any professional (such as a psychologist, counselor, or religious advisor) try to make you identify only with your sex assigned at birth (in other words, try to stop you being trans)?”

They compared responses among subjects who reported exposure to GICE before age 10 years with those who did not.

Subjects were aged a mean of 31 years when they participated in the survey. Slightly less than half (42.8%) were assigned male sex at birth. Most (19,751) had discussed their gender identity with a professional. Nearly 20% (3,869) reported some exposure to GICE; 35% said a religious adviser had conducted the effort.

In this group, exposure had significant negative lifetime effects on mental health. These subjects were at a 56% increased risk of psychological distress within the month before taking the survey (odds ratio, 1.56), and more than twice as likely to have tried at least once to end their lives by suicide (OR, 2.27).

But the negative effects were even more pronounced among the small group of 206 who reported exposure to GICE before they were 10 years old. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for demographics, GICE before age 10 more than quadrupled the risk of lifetime suicide attempts (OR, 4.15). Again, it didn’t matter whether a medical or religious professional administered GICE.