User login

T3 levels are higher in combatants with PTSD

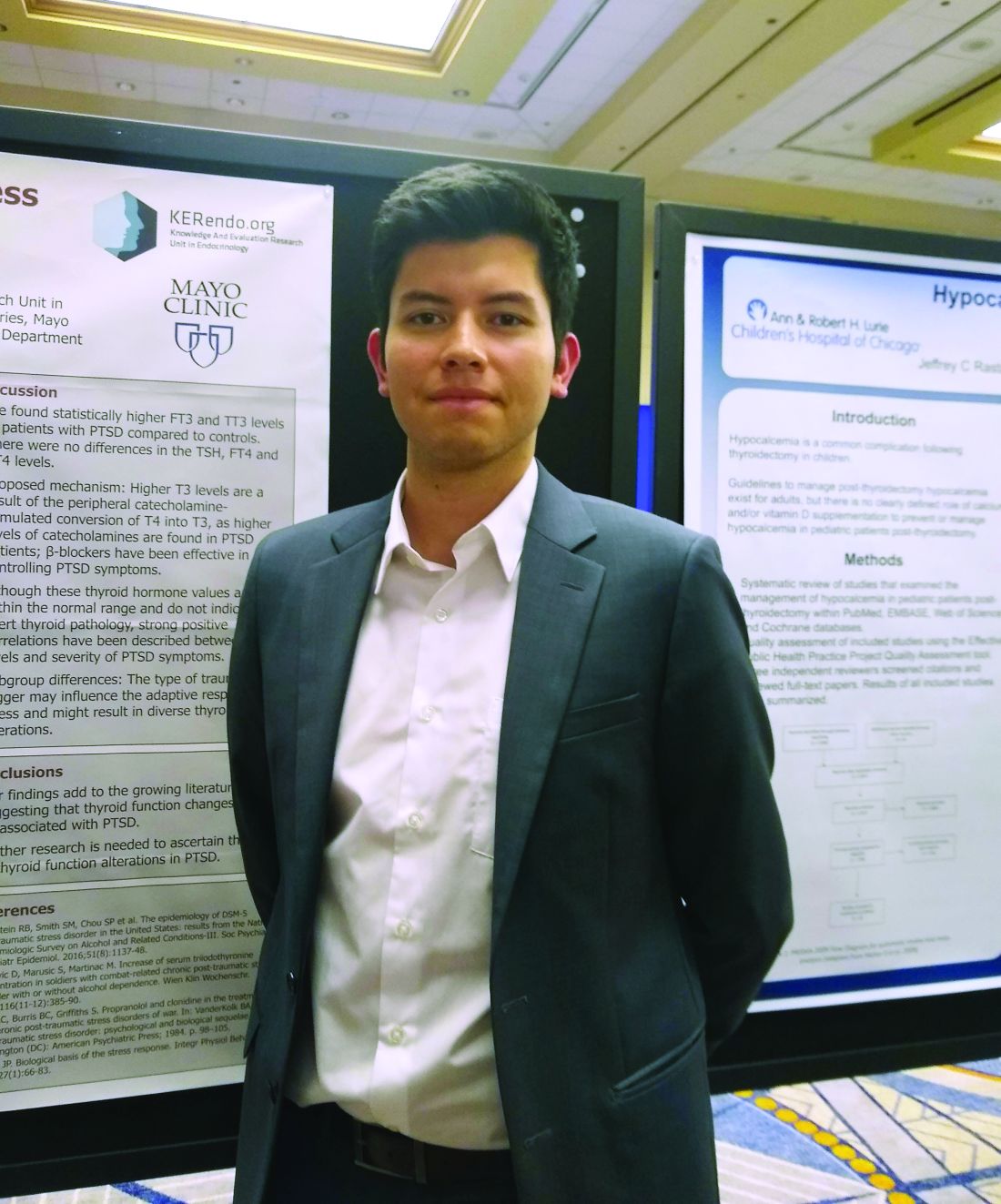

CHICAGO – Higher levels of triiodothyronine (T3) were seen in combatants with PTSD, compared with patients whose PTSD arose from other adverse experiences, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

who had experienced childhood or sexual abuse or were a wartime refugee without PTSD (FT3, 0.36 pg/mL higher, and total T3, 31.6 ng/mL higher, respectively; P = .0004 and P less than .00001).

“We found statistically higher free T3 and total T3 levels in patients with [combat-related] PTSD, compared with controls,” said Freddy J.K. Toloza, MD, in an interview during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

However, he noted that there were no overall differences in thyroid-stimulating hormone, free tetraiodothyronine (T4), and total T4 levels between individuals with PTSD and the non-PTSD control participants. In addition, though free and total T3 levels were significantly higher for the overall PTSD cohort than for control participants, the differences were driven by the studies that included combat-exposed individuals.

Dr. Toloza and colleagues included 10 observational studies in their final review and meta-analysis. Five studies looked at war veterans; the others examined individuals who had experienced child abuse or sexual abuse, who were refugees, or who were from the general population.

For inclusion, the studies had to report both mean values and standard deviations for standard thyroid-hormone test values in patients with PTSD, compared with a non-PTSD control group. These included 373 patients with PTSD and 301 control participants. Just under half (47%) were women. None of the studies, wrote the investigators, “compared rates of overt/subclinical thyroid disease between groups.”

There are known links between many endocrine disorders and psychiatric conditions, said Dr. Toloza, but the interplay between disordered thyroid function and neuropsychiatric problems is still being examined. Looking at PTSD is important because it’s estimated that 6%-9% of the U.S. adult population has experienced PTSD over the course of a lifetime.

Levels of thyroid hormones in the systematic review and meta-analysis were still within normal range for the participants with PTSD, acknowledged Dr. Toloza, a research fellow in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

However, even though there was no sign of frank thyroid disease in the PTSD population, the elevated T3 levels seen in the analysis are consistent with other studies showing a correlation between higher T3 levels and more-severe PTSD.

It is not known exactly why significant increases in the levels of total and free T3 were seen only in the combat-exposed PTSD population, Dr. Toloza said. “The type of trauma trigger may influence the adaptive responses to stress and might result in diverse thyroid alterations.”

Elevated catecholamine levels, seen in individuals with PTSD, can increase peripheral conversion of T4 to T3, explained Dr. Toloza. Ongoing catecholamine elevation may account for the isolated elevation in T3 levels in the PTSD population. Beta1-adrenergic blockade is an accepted pharmacologic strategy to help alleviate PTSD symptoms.

Dr. Toloza and coinvestigators did not have access to data that would have allowed them to ascertain what types of injuries were sustained by individuals with combat-related PTSD, but he noted in response to a question, that it would be worthwhile to see whether combatants who were blast exposed had different thyroid hormone values than those who were not, because hypothalamic injury is common in blast. This is a future direction Dr. Toloza wishes to pursue.

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that thyroid function changes may be associated with PTSD,” the investigators wrote, but “further research is needed to ascertain the role of thyroid function alterations in PTSD.”

Dr. Toloza reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Higher levels of triiodothyronine (T3) were seen in combatants with PTSD, compared with patients whose PTSD arose from other adverse experiences, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

who had experienced childhood or sexual abuse or were a wartime refugee without PTSD (FT3, 0.36 pg/mL higher, and total T3, 31.6 ng/mL higher, respectively; P = .0004 and P less than .00001).

“We found statistically higher free T3 and total T3 levels in patients with [combat-related] PTSD, compared with controls,” said Freddy J.K. Toloza, MD, in an interview during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

However, he noted that there were no overall differences in thyroid-stimulating hormone, free tetraiodothyronine (T4), and total T4 levels between individuals with PTSD and the non-PTSD control participants. In addition, though free and total T3 levels were significantly higher for the overall PTSD cohort than for control participants, the differences were driven by the studies that included combat-exposed individuals.

Dr. Toloza and colleagues included 10 observational studies in their final review and meta-analysis. Five studies looked at war veterans; the others examined individuals who had experienced child abuse or sexual abuse, who were refugees, or who were from the general population.

For inclusion, the studies had to report both mean values and standard deviations for standard thyroid-hormone test values in patients with PTSD, compared with a non-PTSD control group. These included 373 patients with PTSD and 301 control participants. Just under half (47%) were women. None of the studies, wrote the investigators, “compared rates of overt/subclinical thyroid disease between groups.”

There are known links between many endocrine disorders and psychiatric conditions, said Dr. Toloza, but the interplay between disordered thyroid function and neuropsychiatric problems is still being examined. Looking at PTSD is important because it’s estimated that 6%-9% of the U.S. adult population has experienced PTSD over the course of a lifetime.

Levels of thyroid hormones in the systematic review and meta-analysis were still within normal range for the participants with PTSD, acknowledged Dr. Toloza, a research fellow in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

However, even though there was no sign of frank thyroid disease in the PTSD population, the elevated T3 levels seen in the analysis are consistent with other studies showing a correlation between higher T3 levels and more-severe PTSD.

It is not known exactly why significant increases in the levels of total and free T3 were seen only in the combat-exposed PTSD population, Dr. Toloza said. “The type of trauma trigger may influence the adaptive responses to stress and might result in diverse thyroid alterations.”

Elevated catecholamine levels, seen in individuals with PTSD, can increase peripheral conversion of T4 to T3, explained Dr. Toloza. Ongoing catecholamine elevation may account for the isolated elevation in T3 levels in the PTSD population. Beta1-adrenergic blockade is an accepted pharmacologic strategy to help alleviate PTSD symptoms.

Dr. Toloza and coinvestigators did not have access to data that would have allowed them to ascertain what types of injuries were sustained by individuals with combat-related PTSD, but he noted in response to a question, that it would be worthwhile to see whether combatants who were blast exposed had different thyroid hormone values than those who were not, because hypothalamic injury is common in blast. This is a future direction Dr. Toloza wishes to pursue.

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that thyroid function changes may be associated with PTSD,” the investigators wrote, but “further research is needed to ascertain the role of thyroid function alterations in PTSD.”

Dr. Toloza reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Higher levels of triiodothyronine (T3) were seen in combatants with PTSD, compared with patients whose PTSD arose from other adverse experiences, according to findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis.

who had experienced childhood or sexual abuse or were a wartime refugee without PTSD (FT3, 0.36 pg/mL higher, and total T3, 31.6 ng/mL higher, respectively; P = .0004 and P less than .00001).

“We found statistically higher free T3 and total T3 levels in patients with [combat-related] PTSD, compared with controls,” said Freddy J.K. Toloza, MD, in an interview during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

However, he noted that there were no overall differences in thyroid-stimulating hormone, free tetraiodothyronine (T4), and total T4 levels between individuals with PTSD and the non-PTSD control participants. In addition, though free and total T3 levels were significantly higher for the overall PTSD cohort than for control participants, the differences were driven by the studies that included combat-exposed individuals.

Dr. Toloza and colleagues included 10 observational studies in their final review and meta-analysis. Five studies looked at war veterans; the others examined individuals who had experienced child abuse or sexual abuse, who were refugees, or who were from the general population.

For inclusion, the studies had to report both mean values and standard deviations for standard thyroid-hormone test values in patients with PTSD, compared with a non-PTSD control group. These included 373 patients with PTSD and 301 control participants. Just under half (47%) were women. None of the studies, wrote the investigators, “compared rates of overt/subclinical thyroid disease between groups.”

There are known links between many endocrine disorders and psychiatric conditions, said Dr. Toloza, but the interplay between disordered thyroid function and neuropsychiatric problems is still being examined. Looking at PTSD is important because it’s estimated that 6%-9% of the U.S. adult population has experienced PTSD over the course of a lifetime.

Levels of thyroid hormones in the systematic review and meta-analysis were still within normal range for the participants with PTSD, acknowledged Dr. Toloza, a research fellow in the division of endocrinology and metabolism at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

However, even though there was no sign of frank thyroid disease in the PTSD population, the elevated T3 levels seen in the analysis are consistent with other studies showing a correlation between higher T3 levels and more-severe PTSD.

It is not known exactly why significant increases in the levels of total and free T3 were seen only in the combat-exposed PTSD population, Dr. Toloza said. “The type of trauma trigger may influence the adaptive responses to stress and might result in diverse thyroid alterations.”

Elevated catecholamine levels, seen in individuals with PTSD, can increase peripheral conversion of T4 to T3, explained Dr. Toloza. Ongoing catecholamine elevation may account for the isolated elevation in T3 levels in the PTSD population. Beta1-adrenergic blockade is an accepted pharmacologic strategy to help alleviate PTSD symptoms.

Dr. Toloza and coinvestigators did not have access to data that would have allowed them to ascertain what types of injuries were sustained by individuals with combat-related PTSD, but he noted in response to a question, that it would be worthwhile to see whether combatants who were blast exposed had different thyroid hormone values than those who were not, because hypothalamic injury is common in blast. This is a future direction Dr. Toloza wishes to pursue.

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that thyroid function changes may be associated with PTSD,” the investigators wrote, but “further research is needed to ascertain the role of thyroid function alterations in PTSD.”

Dr. Toloza reported no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM ATA 2019

Blood banking experts nab leadership positions at AABB

Beth Shaz, MD, has started her term as president of AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks). Dr. Shaz, who will be president for the 2019-2020 term, was inaugurated during the 2019 AABB annual meeting. She succeeds Michael Murphy, MD, as president.

Dr. Shaz is the executive vice president and chief medical and scientific officer at the New York Blood Center in New York. She is a scientific member of Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion, an associate editor of Transfusion, and an editorial board member of Blood. She received her medical degree from University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

AABB also has a new president-elect, David Green. Mr. Green is president and chief executive officer of Vitalant, and he is based in Scottsdale, Ariz. Mr. Green previously led the Vitalant blood services division. Before that, he was president and chief executive officer of Mississippi Valley Regional Blood Center in Davenport, Iowa.

Mr. Green has served as chairman of Blood Centers of America and president of America’s Blood Centers. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Knox College in Gallesburg, Ill., and a master’s degree from Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant, Mich.

Dana Devine, PhD, is the new vice president of AABB. Dr. Devine is the chief medical and scientific officer at Canadian Blood Services. She is also a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and a founding member of the university’s Centre for Blood Research.

Dr. Devine’s research is focused on platelet biology, complement biochemistry, coagulation, and blood product processing and storage. Dr. Devine is the editor in chief of Vox Sanguinis. She earned her PhD from Duke University in Durham, N.C.

Steven Sloan, MD, PhD, is the new secretary of AABB. Dr. Sloan is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston and blood bank medical director at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Dr. Sloan’s research is focused on intracellular signaling and transcription regulation in B cells during immune responses. Dr. Sloan attended medical school at New York University in New York, and completed his residency and fellowship at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Beth Shaz, MD, has started her term as president of AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks). Dr. Shaz, who will be president for the 2019-2020 term, was inaugurated during the 2019 AABB annual meeting. She succeeds Michael Murphy, MD, as president.

Dr. Shaz is the executive vice president and chief medical and scientific officer at the New York Blood Center in New York. She is a scientific member of Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion, an associate editor of Transfusion, and an editorial board member of Blood. She received her medical degree from University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

AABB also has a new president-elect, David Green. Mr. Green is president and chief executive officer of Vitalant, and he is based in Scottsdale, Ariz. Mr. Green previously led the Vitalant blood services division. Before that, he was president and chief executive officer of Mississippi Valley Regional Blood Center in Davenport, Iowa.

Mr. Green has served as chairman of Blood Centers of America and president of America’s Blood Centers. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Knox College in Gallesburg, Ill., and a master’s degree from Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant, Mich.

Dana Devine, PhD, is the new vice president of AABB. Dr. Devine is the chief medical and scientific officer at Canadian Blood Services. She is also a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and a founding member of the university’s Centre for Blood Research.

Dr. Devine’s research is focused on platelet biology, complement biochemistry, coagulation, and blood product processing and storage. Dr. Devine is the editor in chief of Vox Sanguinis. She earned her PhD from Duke University in Durham, N.C.

Steven Sloan, MD, PhD, is the new secretary of AABB. Dr. Sloan is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston and blood bank medical director at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Dr. Sloan’s research is focused on intracellular signaling and transcription regulation in B cells during immune responses. Dr. Sloan attended medical school at New York University in New York, and completed his residency and fellowship at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Beth Shaz, MD, has started her term as president of AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks). Dr. Shaz, who will be president for the 2019-2020 term, was inaugurated during the 2019 AABB annual meeting. She succeeds Michael Murphy, MD, as president.

Dr. Shaz is the executive vice president and chief medical and scientific officer at the New York Blood Center in New York. She is a scientific member of Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion, an associate editor of Transfusion, and an editorial board member of Blood. She received her medical degree from University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

AABB also has a new president-elect, David Green. Mr. Green is president and chief executive officer of Vitalant, and he is based in Scottsdale, Ariz. Mr. Green previously led the Vitalant blood services division. Before that, he was president and chief executive officer of Mississippi Valley Regional Blood Center in Davenport, Iowa.

Mr. Green has served as chairman of Blood Centers of America and president of America’s Blood Centers. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Knox College in Gallesburg, Ill., and a master’s degree from Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant, Mich.

Dana Devine, PhD, is the new vice president of AABB. Dr. Devine is the chief medical and scientific officer at Canadian Blood Services. She is also a professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and a founding member of the university’s Centre for Blood Research.

Dr. Devine’s research is focused on platelet biology, complement biochemistry, coagulation, and blood product processing and storage. Dr. Devine is the editor in chief of Vox Sanguinis. She earned her PhD from Duke University in Durham, N.C.

Steven Sloan, MD, PhD, is the new secretary of AABB. Dr. Sloan is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston and blood bank medical director at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Dr. Sloan’s research is focused on intracellular signaling and transcription regulation in B cells during immune responses. Dr. Sloan attended medical school at New York University in New York, and completed his residency and fellowship at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Experts address barriers to genetic screening

WASHINGTON – Early diagnosis and intervention for genetic diseases using the latest carrier screening can allow families to be prepared and informed prior to pregnancy, said Aishwarya Arjunan, MS, MPH, a clinical product specialist for carrier screening at Myriad Women’s Health, part of a diagnostic testing company based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Rare diseases are responsible for 35% of deaths in the first year of life,” she said in a panel discussion at the Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit sponsored by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Most patients with rare diseases go through a “diagnostic odyssey” lasting an average of 8 years before they receive an accurate diagnosis, she said. During this time, data suggest that they have likely been misdiagnosed three times and have seen more than 10 specialists, she added.

Barriers to genetic screening include limited access to genetics professionals, lack of patient and provider education about screening, issues of insurance coverage and reimbursement, coding challenges, and misperceptions about the perceived impact of screening, noted Jodie Vento, manager of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

The genetic carrier screening options, often referred to as panethnic expanded carrier screening, represents a change from previous screening protocols based on ethnicity, said Ms. Arjunan. However, guidelines for screening based on ethnicity “misses a significant percentage of pregnancies affected by serious conditions and widens the health disparity gap,” she said.

By contrast, expanded carrier screening allows for standardization of care that gives couples and families information to make decisions and preparations.

Current genetic testing strategies include single gene testing, in which a single gene of interest is tested; multigene panel testing, in which a subset of clinically important genes are tested; whole-exome sequencing, in which the DNA responsible for coding proteins is tested; and whole-genome sequencing, in which the entire human genome is tested for genetic disorders.

Improving access to genetic testing involves a combination of provider education, changes in payer policies, action by advocacy groups, and adjustment of societal guidelines, said Ms. Arjunan. However, the advantages of expanded carrier screening are many and include guiding patients to expert care early and setting up plans for long-term care and follow-up, she noted. In addition, early identification through screening can help patients reduce or eliminate the diagnostic odyssey and connect with advocacy and community groups for support, she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Early diagnosis and intervention for genetic diseases using the latest carrier screening can allow families to be prepared and informed prior to pregnancy, said Aishwarya Arjunan, MS, MPH, a clinical product specialist for carrier screening at Myriad Women’s Health, part of a diagnostic testing company based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Rare diseases are responsible for 35% of deaths in the first year of life,” she said in a panel discussion at the Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit sponsored by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Most patients with rare diseases go through a “diagnostic odyssey” lasting an average of 8 years before they receive an accurate diagnosis, she said. During this time, data suggest that they have likely been misdiagnosed three times and have seen more than 10 specialists, she added.

Barriers to genetic screening include limited access to genetics professionals, lack of patient and provider education about screening, issues of insurance coverage and reimbursement, coding challenges, and misperceptions about the perceived impact of screening, noted Jodie Vento, manager of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

The genetic carrier screening options, often referred to as panethnic expanded carrier screening, represents a change from previous screening protocols based on ethnicity, said Ms. Arjunan. However, guidelines for screening based on ethnicity “misses a significant percentage of pregnancies affected by serious conditions and widens the health disparity gap,” she said.

By contrast, expanded carrier screening allows for standardization of care that gives couples and families information to make decisions and preparations.

Current genetic testing strategies include single gene testing, in which a single gene of interest is tested; multigene panel testing, in which a subset of clinically important genes are tested; whole-exome sequencing, in which the DNA responsible for coding proteins is tested; and whole-genome sequencing, in which the entire human genome is tested for genetic disorders.

Improving access to genetic testing involves a combination of provider education, changes in payer policies, action by advocacy groups, and adjustment of societal guidelines, said Ms. Arjunan. However, the advantages of expanded carrier screening are many and include guiding patients to expert care early and setting up plans for long-term care and follow-up, she noted. In addition, early identification through screening can help patients reduce or eliminate the diagnostic odyssey and connect with advocacy and community groups for support, she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – Early diagnosis and intervention for genetic diseases using the latest carrier screening can allow families to be prepared and informed prior to pregnancy, said Aishwarya Arjunan, MS, MPH, a clinical product specialist for carrier screening at Myriad Women’s Health, part of a diagnostic testing company based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Rare diseases are responsible for 35% of deaths in the first year of life,” she said in a panel discussion at the Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit sponsored by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Most patients with rare diseases go through a “diagnostic odyssey” lasting an average of 8 years before they receive an accurate diagnosis, she said. During this time, data suggest that they have likely been misdiagnosed three times and have seen more than 10 specialists, she added.

Barriers to genetic screening include limited access to genetics professionals, lack of patient and provider education about screening, issues of insurance coverage and reimbursement, coding challenges, and misperceptions about the perceived impact of screening, noted Jodie Vento, manager of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

The genetic carrier screening options, often referred to as panethnic expanded carrier screening, represents a change from previous screening protocols based on ethnicity, said Ms. Arjunan. However, guidelines for screening based on ethnicity “misses a significant percentage of pregnancies affected by serious conditions and widens the health disparity gap,” she said.

By contrast, expanded carrier screening allows for standardization of care that gives couples and families information to make decisions and preparations.

Current genetic testing strategies include single gene testing, in which a single gene of interest is tested; multigene panel testing, in which a subset of clinically important genes are tested; whole-exome sequencing, in which the DNA responsible for coding proteins is tested; and whole-genome sequencing, in which the entire human genome is tested for genetic disorders.

Improving access to genetic testing involves a combination of provider education, changes in payer policies, action by advocacy groups, and adjustment of societal guidelines, said Ms. Arjunan. However, the advantages of expanded carrier screening are many and include guiding patients to expert care early and setting up plans for long-term care and follow-up, she noted. In addition, early identification through screening can help patients reduce or eliminate the diagnostic odyssey and connect with advocacy and community groups for support, she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NORD 2019

Conflicting psychiatric agendas in our polarized world

A series of case discussions recently engendered discord among colleagues of ours. The conflicts raised questions about systemic biases within our field and their possible ramifications.

The cases discussed, like many in psychiatry, involved patients with severely maladaptive coping skills who lived with punishing friends, had little rewarding purpose, and had dismissive or abusive families. The conflicts involved whether the treating psychiatrists should promote seemingly obvious life choices or whether those perspectives were based in socionormative stereotypes seeped in mistaken traditional values that do not account for the rich array of experiences our patients come from.

One such case involved a seemingly masochistic patient who repeatedly found herself in abusive relationships and whether the psychiatrist should consider criticizing her partner choices. Another case involved a severely suffering veteran who felt paralyzed at home and whether the psychiatrist should encourage employment to diminish isolation. Yet another case involved a suicidal transgender patient who was in despair when feeling little relief after receiving gender-conforming surgery and – whether the psychiatrist should or could discuss perspectives on gender.

Those cases have led to accusations of misunderstanding science on both sides – and questions about the political justifications and consequences of psychiatric recommendations.

The field of psychiatry is appropriately embarrassed by its former association to misogynistic, homophobic, and even racist schools of thought. However, we wonder whether our current attempts at penance are at times discouraging important discussions. In some cases, our lowest-functioning patients living on the fringe of society benefit the most from the stabilizing influences of family, employment, social institutions, or religious worship. This is especially true considering how much social isolation has become an increasing reality of modern life. As such, we worry when colleagues argue that the promotion of common values is inherently suspect.

This problem may be exemplified by the public attacks on Allan Josephson, MD. Dr. Josephson, a child psychiatrist at the University of Louisville (Ky.), contends that he was ostracized and later fired from his position for communicating at a Heritage Foundation forum on his concerns about current recommended treatments and approaches for gender dysphoria. It appears that, despite being a renowned and previously deeply respected expert in the field, his opinions on the subject now go beyond the acceptable discourse of psychiatry. It is not just that the establishment disagrees with him, he allegedly has gone beyond the acceptable bounds of professionalism.

This reaction is surprising from numerous perspectives. First, his opinions would have seemed mainstream to many only a few years ago. Second, there is no large body of scientific evidence that has been generated to confirm that he is promoting an unscientific perspective that should rightly get ostracized by the medical community – such as anti-vaccination. Actually, some evidence suggests that some medical approaches to gender dysphoria have not always ameliorated the distress found in some patients.

After reviewing the evidence on gender reassignment surgery a few years ago, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services concluded: “Based on an extensive assessment of the clinical evidence as described above, there is not enough high-quality evidence to determine whether gender reassignment surgery improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with gender dysphoria and whether patients most likely to benefit from these types of surgical intervention can be identified prospectively.”

Whether such a diagnosis should exist at all in the DSM is a worthy topic of discussion with inclusive arguments on both sides. Pathologizing gender dysphoria is stigmatizing. At the same time, a diagnosis may permit one to receive assistance for a recognized condition. One may rightfully want to discuss the scientific merit of a diagnosis without the interference of arguments based on political or social ramifications of said diagnosis, despite their obvious existence and import.

One should be able to voice scientific opinions in a fair-minded, nonpolitically biased manner that is not designed to intimidate and harass dissenters. One should note that a debate about the appropriateness of having said diagnosis will bring up many philosophical and deeply uncomfortable questions. Those questions point out the apparent nosologic problems inherent in DSM methodology that are extraordinarily difficult to solve. If psychiatry chooses to produce or dismiss psychiatric diagnoses based on the inherent political inconvenience of said diagnoses, rather than their scientific and medical basis, the entire field will rightly be called into question.

One may deplore the static and at times oppressive nature of cultural biases. However, it should be noted that the ability to safely step outside the supportive structure of family, employment, and social and religious institution is itself a privilege, one in which some our patients do not have the luxury of engaging in.

It is not clear to us how we got to this juncture. Part of psychiatric and medical training does involve learning nonjudgmental approaches to human suffering and an identification with individual needs over societal demands. Our suspicion is that a nonjudgmental approach to the understanding of the human condition may be exaggerated into a desire to solve the human condition without challenging patients’ fundamental need for a well-rounded biologic, psychological, and social recovery. It is also possible that our desire to promote utopian hopes for society has blinded us from accepting the idea that, for many of our lowest-functioning patients, fitting in and participating in society can be their best path to recovery.

Psychiatry attempts to define and alleviate the suffering that accompanies some behaviors. As such, psychiatry has always and will always address and confront behaviors that society may condemn. At times, psychiatrists will be in sync or clash with societal trends. Sometimes science will contradict societal wishes. And ultimately, psychiatrists will hopefully make decisions informed in biopsychosocial constructs that best suit the patient in front of them no matter what society may want. In a polarized environment, psychiatry should remind itself that we cannot always or ever fix society, and that maintaining reasonable cultural norms and societal stability – while avoiding the traps of superficial culture wars and utopian visions – is often the wisest path.

Dr. Lehman is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He also is the course director for the UCSD third-year medical student psychiatry clerkship. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at UCSD and the University of San Diego. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

A series of case discussions recently engendered discord among colleagues of ours. The conflicts raised questions about systemic biases within our field and their possible ramifications.

The cases discussed, like many in psychiatry, involved patients with severely maladaptive coping skills who lived with punishing friends, had little rewarding purpose, and had dismissive or abusive families. The conflicts involved whether the treating psychiatrists should promote seemingly obvious life choices or whether those perspectives were based in socionormative stereotypes seeped in mistaken traditional values that do not account for the rich array of experiences our patients come from.

One such case involved a seemingly masochistic patient who repeatedly found herself in abusive relationships and whether the psychiatrist should consider criticizing her partner choices. Another case involved a severely suffering veteran who felt paralyzed at home and whether the psychiatrist should encourage employment to diminish isolation. Yet another case involved a suicidal transgender patient who was in despair when feeling little relief after receiving gender-conforming surgery and – whether the psychiatrist should or could discuss perspectives on gender.

Those cases have led to accusations of misunderstanding science on both sides – and questions about the political justifications and consequences of psychiatric recommendations.

The field of psychiatry is appropriately embarrassed by its former association to misogynistic, homophobic, and even racist schools of thought. However, we wonder whether our current attempts at penance are at times discouraging important discussions. In some cases, our lowest-functioning patients living on the fringe of society benefit the most from the stabilizing influences of family, employment, social institutions, or religious worship. This is especially true considering how much social isolation has become an increasing reality of modern life. As such, we worry when colleagues argue that the promotion of common values is inherently suspect.

This problem may be exemplified by the public attacks on Allan Josephson, MD. Dr. Josephson, a child psychiatrist at the University of Louisville (Ky.), contends that he was ostracized and later fired from his position for communicating at a Heritage Foundation forum on his concerns about current recommended treatments and approaches for gender dysphoria. It appears that, despite being a renowned and previously deeply respected expert in the field, his opinions on the subject now go beyond the acceptable discourse of psychiatry. It is not just that the establishment disagrees with him, he allegedly has gone beyond the acceptable bounds of professionalism.

This reaction is surprising from numerous perspectives. First, his opinions would have seemed mainstream to many only a few years ago. Second, there is no large body of scientific evidence that has been generated to confirm that he is promoting an unscientific perspective that should rightly get ostracized by the medical community – such as anti-vaccination. Actually, some evidence suggests that some medical approaches to gender dysphoria have not always ameliorated the distress found in some patients.

After reviewing the evidence on gender reassignment surgery a few years ago, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services concluded: “Based on an extensive assessment of the clinical evidence as described above, there is not enough high-quality evidence to determine whether gender reassignment surgery improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with gender dysphoria and whether patients most likely to benefit from these types of surgical intervention can be identified prospectively.”

Whether such a diagnosis should exist at all in the DSM is a worthy topic of discussion with inclusive arguments on both sides. Pathologizing gender dysphoria is stigmatizing. At the same time, a diagnosis may permit one to receive assistance for a recognized condition. One may rightfully want to discuss the scientific merit of a diagnosis without the interference of arguments based on political or social ramifications of said diagnosis, despite their obvious existence and import.

One should be able to voice scientific opinions in a fair-minded, nonpolitically biased manner that is not designed to intimidate and harass dissenters. One should note that a debate about the appropriateness of having said diagnosis will bring up many philosophical and deeply uncomfortable questions. Those questions point out the apparent nosologic problems inherent in DSM methodology that are extraordinarily difficult to solve. If psychiatry chooses to produce or dismiss psychiatric diagnoses based on the inherent political inconvenience of said diagnoses, rather than their scientific and medical basis, the entire field will rightly be called into question.

One may deplore the static and at times oppressive nature of cultural biases. However, it should be noted that the ability to safely step outside the supportive structure of family, employment, and social and religious institution is itself a privilege, one in which some our patients do not have the luxury of engaging in.

It is not clear to us how we got to this juncture. Part of psychiatric and medical training does involve learning nonjudgmental approaches to human suffering and an identification with individual needs over societal demands. Our suspicion is that a nonjudgmental approach to the understanding of the human condition may be exaggerated into a desire to solve the human condition without challenging patients’ fundamental need for a well-rounded biologic, psychological, and social recovery. It is also possible that our desire to promote utopian hopes for society has blinded us from accepting the idea that, for many of our lowest-functioning patients, fitting in and participating in society can be their best path to recovery.

Psychiatry attempts to define and alleviate the suffering that accompanies some behaviors. As such, psychiatry has always and will always address and confront behaviors that society may condemn. At times, psychiatrists will be in sync or clash with societal trends. Sometimes science will contradict societal wishes. And ultimately, psychiatrists will hopefully make decisions informed in biopsychosocial constructs that best suit the patient in front of them no matter what society may want. In a polarized environment, psychiatry should remind itself that we cannot always or ever fix society, and that maintaining reasonable cultural norms and societal stability – while avoiding the traps of superficial culture wars and utopian visions – is often the wisest path.

Dr. Lehman is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He also is the course director for the UCSD third-year medical student psychiatry clerkship. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at UCSD and the University of San Diego. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

A series of case discussions recently engendered discord among colleagues of ours. The conflicts raised questions about systemic biases within our field and their possible ramifications.

The cases discussed, like many in psychiatry, involved patients with severely maladaptive coping skills who lived with punishing friends, had little rewarding purpose, and had dismissive or abusive families. The conflicts involved whether the treating psychiatrists should promote seemingly obvious life choices or whether those perspectives were based in socionormative stereotypes seeped in mistaken traditional values that do not account for the rich array of experiences our patients come from.

One such case involved a seemingly masochistic patient who repeatedly found herself in abusive relationships and whether the psychiatrist should consider criticizing her partner choices. Another case involved a severely suffering veteran who felt paralyzed at home and whether the psychiatrist should encourage employment to diminish isolation. Yet another case involved a suicidal transgender patient who was in despair when feeling little relief after receiving gender-conforming surgery and – whether the psychiatrist should or could discuss perspectives on gender.

Those cases have led to accusations of misunderstanding science on both sides – and questions about the political justifications and consequences of psychiatric recommendations.

The field of psychiatry is appropriately embarrassed by its former association to misogynistic, homophobic, and even racist schools of thought. However, we wonder whether our current attempts at penance are at times discouraging important discussions. In some cases, our lowest-functioning patients living on the fringe of society benefit the most from the stabilizing influences of family, employment, social institutions, or religious worship. This is especially true considering how much social isolation has become an increasing reality of modern life. As such, we worry when colleagues argue that the promotion of common values is inherently suspect.

This problem may be exemplified by the public attacks on Allan Josephson, MD. Dr. Josephson, a child psychiatrist at the University of Louisville (Ky.), contends that he was ostracized and later fired from his position for communicating at a Heritage Foundation forum on his concerns about current recommended treatments and approaches for gender dysphoria. It appears that, despite being a renowned and previously deeply respected expert in the field, his opinions on the subject now go beyond the acceptable discourse of psychiatry. It is not just that the establishment disagrees with him, he allegedly has gone beyond the acceptable bounds of professionalism.

This reaction is surprising from numerous perspectives. First, his opinions would have seemed mainstream to many only a few years ago. Second, there is no large body of scientific evidence that has been generated to confirm that he is promoting an unscientific perspective that should rightly get ostracized by the medical community – such as anti-vaccination. Actually, some evidence suggests that some medical approaches to gender dysphoria have not always ameliorated the distress found in some patients.

After reviewing the evidence on gender reassignment surgery a few years ago, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services concluded: “Based on an extensive assessment of the clinical evidence as described above, there is not enough high-quality evidence to determine whether gender reassignment surgery improves health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with gender dysphoria and whether patients most likely to benefit from these types of surgical intervention can be identified prospectively.”

Whether such a diagnosis should exist at all in the DSM is a worthy topic of discussion with inclusive arguments on both sides. Pathologizing gender dysphoria is stigmatizing. At the same time, a diagnosis may permit one to receive assistance for a recognized condition. One may rightfully want to discuss the scientific merit of a diagnosis without the interference of arguments based on political or social ramifications of said diagnosis, despite their obvious existence and import.

One should be able to voice scientific opinions in a fair-minded, nonpolitically biased manner that is not designed to intimidate and harass dissenters. One should note that a debate about the appropriateness of having said diagnosis will bring up many philosophical and deeply uncomfortable questions. Those questions point out the apparent nosologic problems inherent in DSM methodology that are extraordinarily difficult to solve. If psychiatry chooses to produce or dismiss psychiatric diagnoses based on the inherent political inconvenience of said diagnoses, rather than their scientific and medical basis, the entire field will rightly be called into question.

One may deplore the static and at times oppressive nature of cultural biases. However, it should be noted that the ability to safely step outside the supportive structure of family, employment, and social and religious institution is itself a privilege, one in which some our patients do not have the luxury of engaging in.

It is not clear to us how we got to this juncture. Part of psychiatric and medical training does involve learning nonjudgmental approaches to human suffering and an identification with individual needs over societal demands. Our suspicion is that a nonjudgmental approach to the understanding of the human condition may be exaggerated into a desire to solve the human condition without challenging patients’ fundamental need for a well-rounded biologic, psychological, and social recovery. It is also possible that our desire to promote utopian hopes for society has blinded us from accepting the idea that, for many of our lowest-functioning patients, fitting in and participating in society can be their best path to recovery.

Psychiatry attempts to define and alleviate the suffering that accompanies some behaviors. As such, psychiatry has always and will always address and confront behaviors that society may condemn. At times, psychiatrists will be in sync or clash with societal trends. Sometimes science will contradict societal wishes. And ultimately, psychiatrists will hopefully make decisions informed in biopsychosocial constructs that best suit the patient in front of them no matter what society may want. In a polarized environment, psychiatry should remind itself that we cannot always or ever fix society, and that maintaining reasonable cultural norms and societal stability – while avoiding the traps of superficial culture wars and utopian visions – is often the wisest path.

Dr. Lehman is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. He is codirector of all acute and intensive psychiatric treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego, where he practices clinical psychiatry. He also is the course director for the UCSD third-year medical student psychiatry clerkship. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at UCSD and the University of San Diego. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com.

Six strengths identified in adult men with ADHD

A qualitative investigation based on interviews with successful adults with ADHD identified six core themes that are positive aspects of ADHD.

Under a phenomenology framework, purposive sampling was used to enroll six successful male participants with ADHD diagnoses. The participants were interviewed in an open-ended way and were assessed with theme content analysis, reported Jane Ann Sedgwick, a PhD candidate within the MRC Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Center at King’s College London, and coauthors. The six core themes identified were cognitive dynamism, courage, energy, humanity, resilience, and transcendence. They then compared those themes with attributes cataloged in a handbook by Christopher Petersen and Marten E.P. Seligman (Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press, 2004). The study was published in ADHD: Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders.

Because energy and cognitive dynamism as discussed in the present research were not cataloged in that handbook, they were unique to ADHD, according to Ms. Sedgwick and coauthors. The theme of energy described “participants’ reports about internal experiences and capacity for action,” with subthemes of spirit, which embraces higher aspects of self, sense of purpose, and meaning in life; psychological energy, including drive and volition; and physical energy, which can manifest as interest in and enjoyment of activities such as sports. Meanwhile, cognitive dynamism describes the “ceaseless mental activity that was reported by all participants,” including subthemes of divergent thinking, hyperfocus, creativity, and curiosity.

Limitations of the study included the shortcomings within the phenomenological framework, which requires participants who are capable of being articulate, expressive, and reflective. Another is the small sample size and absence of female participants.

“Too often people with lived experience hear about ADHD in relation to deficits, functional impairments, and associations with substance misuse, criminality, or other disadvantages on almost every level of life (school, work, relationships),” Ms. Sedgwick and her coauthors wrote.

A qualitative investigation based on interviews with successful adults with ADHD identified six core themes that are positive aspects of ADHD.

Under a phenomenology framework, purposive sampling was used to enroll six successful male participants with ADHD diagnoses. The participants were interviewed in an open-ended way and were assessed with theme content analysis, reported Jane Ann Sedgwick, a PhD candidate within the MRC Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Center at King’s College London, and coauthors. The six core themes identified were cognitive dynamism, courage, energy, humanity, resilience, and transcendence. They then compared those themes with attributes cataloged in a handbook by Christopher Petersen and Marten E.P. Seligman (Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press, 2004). The study was published in ADHD: Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders.

Because energy and cognitive dynamism as discussed in the present research were not cataloged in that handbook, they were unique to ADHD, according to Ms. Sedgwick and coauthors. The theme of energy described “participants’ reports about internal experiences and capacity for action,” with subthemes of spirit, which embraces higher aspects of self, sense of purpose, and meaning in life; psychological energy, including drive and volition; and physical energy, which can manifest as interest in and enjoyment of activities such as sports. Meanwhile, cognitive dynamism describes the “ceaseless mental activity that was reported by all participants,” including subthemes of divergent thinking, hyperfocus, creativity, and curiosity.

Limitations of the study included the shortcomings within the phenomenological framework, which requires participants who are capable of being articulate, expressive, and reflective. Another is the small sample size and absence of female participants.

“Too often people with lived experience hear about ADHD in relation to deficits, functional impairments, and associations with substance misuse, criminality, or other disadvantages on almost every level of life (school, work, relationships),” Ms. Sedgwick and her coauthors wrote.

A qualitative investigation based on interviews with successful adults with ADHD identified six core themes that are positive aspects of ADHD.

Under a phenomenology framework, purposive sampling was used to enroll six successful male participants with ADHD diagnoses. The participants were interviewed in an open-ended way and were assessed with theme content analysis, reported Jane Ann Sedgwick, a PhD candidate within the MRC Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Center at King’s College London, and coauthors. The six core themes identified were cognitive dynamism, courage, energy, humanity, resilience, and transcendence. They then compared those themes with attributes cataloged in a handbook by Christopher Petersen and Marten E.P. Seligman (Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press, 2004). The study was published in ADHD: Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders.

Because energy and cognitive dynamism as discussed in the present research were not cataloged in that handbook, they were unique to ADHD, according to Ms. Sedgwick and coauthors. The theme of energy described “participants’ reports about internal experiences and capacity for action,” with subthemes of spirit, which embraces higher aspects of self, sense of purpose, and meaning in life; psychological energy, including drive and volition; and physical energy, which can manifest as interest in and enjoyment of activities such as sports. Meanwhile, cognitive dynamism describes the “ceaseless mental activity that was reported by all participants,” including subthemes of divergent thinking, hyperfocus, creativity, and curiosity.

Limitations of the study included the shortcomings within the phenomenological framework, which requires participants who are capable of being articulate, expressive, and reflective. Another is the small sample size and absence of female participants.

“Too often people with lived experience hear about ADHD in relation to deficits, functional impairments, and associations with substance misuse, criminality, or other disadvantages on almost every level of life (school, work, relationships),” Ms. Sedgwick and her coauthors wrote.

FROM ADHD: ATTENTION DEFICIT AND HYPERACTIVITY DISORDERS

After Residency, Then What?

A Psychological Systems Review

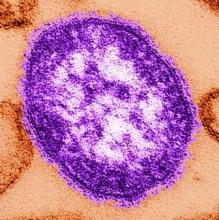

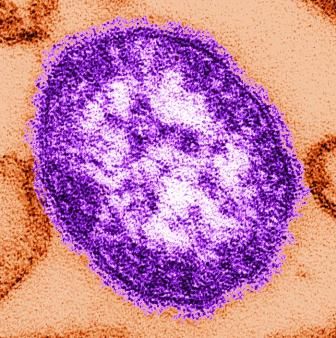

Measles causes B-cell changes, leading to ‘immune amnesia’

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

“Our findings provide a biological explanation for the observed increase in childhood mortality and secondary infections several years after an episode of measles,” said Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, and coauthors. The study was published in Science Immunology.

To determine if B-cell impairment can lead to measles-associated immunosuppression, the researchers investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. Their antibody genes were sequenced before any symptoms of measles developed and roughly 40 days after rash. Two control groups also were sequenced accordingly: vaccinated adults and three unvaccinated children from the same community who were not infected with measles.

Naive B cells from individuals in the vaccinated and uninfected control groups showed high correlation of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV-J) gene frequencies across time periods (R2 = 0.96 and 0.92, respectively) but no significant differences in gene expression (P greater than .05). At the same time, although B cell frequencies in measles patients recovered to levels before infection, they had significant changes in IGHV-J gene frequencies (P = .01) and decreased correlation in gene expression (R2 = 0.78).

In addition, individuals in the control groups had “a stable genetic composition of B memory cells” but no significant changes in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) lengths or mutational frequency of IGHV genes (P greater than .05). B memory cells in measles patients, however, showed increases in mutational frequency (P = .0008) and a reduction in CDR3 length (P = .017) of IGHV genes, Dr. Petrova and associates said.

Finally, the researchers confirmed a hypothesis about the depletion of B memory cell clones during measles and a repopulation of new cells with less clonal expansion. The frequency of individual IGHV-J gene combinations before infection was correlated with a reduction after infection, “with the most frequent combinations undergoing the most marked depletion” and the result being an increase in genetic diversity.

To further test their findings, the researchers vaccinated two groups of four ferrets with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and at 4 weeks infected one of the groups with canine distemper virus (CDV), a surrogate for MeV. At 14 weeks after vaccination, the uninfected group maintained high levels of influenza-specific neutralizing antibodies while the infected group saw impaired B cells and a subsequent reduction in neutralizing antibodies.

Understanding the impact of measles on the immune system

“How measles infection has such a long-lasting deleterious effect on the immune system while allowing robust immunity against itself has been a burning immunological question,” Duane R. Wesemann, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an accompanying editorial. The research from Petrova et al. begins to answer that question.

Among the observations he found most interesting was how “post-measles memory cells were more diverse than the pre-measles memory pool,” despite expectations that measles immunity would be dominant. He speculated that the void in memory cells is filled by a set of clones binding to unidentified or nonnative antigens, which may bring polyclonal diversity into B memory cells.

More research is needed to determine just what these findings mean, including looking beyond memory cell depletion and focusing on the impact of immature immunoglobulin repertoires in naive cells. But his broad takeaway is that measles remains both a public health concern and an opportunity to understand how the human body counters disease.

“The unique relationship measles has with the human immune system,” he said, “can illuminate aspects of its inner workings.”

The study was funded by grants to the investigators the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education, the Wellcome Trust, the German Centre for Infection Research, the Collaborative Research Centre of the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Health, and the Royal Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Wesemann reported receiving support from National Institutes of Health grants and an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; he also reports being a consultant for OpenBiome.

SOURCE: Petrova VN et al. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6125; Wesemann DR. Sci Immunol. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4195.

FROM SCIENCE IMMUNOTHERAPY

Body weight influences SGLT2-inhibitor effects in type 1 diabetes

BARCELONA – Individuals with type 1 diabetes and a high body mass index gain the most benefit with the least risk when sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are added to insulin therapy, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Results from new analyses of the inTandem 1 and inTandem 2 trials with sotagliflozin (Zynquista), and the DEPICT-1 and DEPICT-2 trials with dapagliflozin (Farxiga), support the recent decision of the European Medicines Agency to license the use of the drugs only in patients with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher.

inTandem with sotagliflozin

Weight gain is a challenge in patients with type 1 diabetes, said Thomas Danne, MD, who presented post hoc data from the two inTandem studies. “It’s a little bit counterintuitive,” he acknowledged, “but you have to realize, particularly in patients who have hypoglycemia, that they have to take in extra carbohydrates,” which may tip them to becoming overweight or obese.

SGLT2-inhibitor therapy with sotagliflozin or dapagliflozin added to insulin therapy has been shown to reduce body weight in individuals with type 1 diabetes, but there is an increased risk for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). That risk, however, seems to be lower in the higher body-weight categories.

Dr. Danne, director of the department of general pediatrics, endocrinology, and diabetology, and clinical research at the Auf der Bult Hospital for Children and Adolescents, at the Hannover (Germany) Medical School, presented data looking at the outcomes of patients treated with sotagliflozin or placebo based on their BMI.

In all, 1,575 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 659 were of normal weight (BMI of less than 27 kg/m2; average mean, 24 kg/m2 at baseline), and 916 had a higher weight (BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher; average mean, 32 kg/m2 at baseline). The mean age of patients at study entry was 42 years for those with the lower BMI, and 45 years for those with the higher BMI.

Patients in the two inTandem trials had been treated with insulin plus placebo (n = 228, BMI less than 27 kg/m2; n = 298, BMI 27 kg/m2 or higher), or insulin plus sotagliflozin at a dose of 200 mg (n = 219, BMI less than 27 kg/m2; n = 305, BMI 27 kg/m2 or higher) or 400 mg (n = 212; BMI less than 27 kg/m2; n = 313, BMI 27 kg/m2 or higher).

Glycemic control and body weight

Greater reductions in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were seen with sotagliflozin versus placebo, and even more so, if the BMI was 27 kg/m2 or higher. At week 24, the least-squares mean difference in HbA1c comparing sotagliflozin 200 mg and placebo was –0.32 in patients with the lower BMI, compared with –0.39 in those with the higher BMI. Corresponding values for the 400-mg sotagliflozin group in the higher-BMI group were –0.27 and –0.45, respectively (P less than .001 for all comparisons).

In the lower-BMI group, week 24 least-squares mean differences in body weight comparing sotagliflozin and placebo were –2.06 kg for the 200-mg group and –2.55 kg for the 400-mg group, and –2.27 kg and 3.32 kg in the higher-BMI group (P less than .001 for all comparisons).

“This is why this class of drugs holds so much of a promise, [because] it’s not only one good effect regarding improvement of glycemia judged by A1c,” Dr. Danne said.

He also reported that treatment with sotagliflozin was associated with an increased time in range, compared with placebo, again, with greater effects seen in the higher- versus lower-BMI groups. In those with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or more, there was an additional 1 hour 58 minutes time in range for the 200-mg dose, and 3 hours 37 minutes for the 200-mg dose, compared with an extra 24 minutes and 1 hour 31 minutes, respectively, in the lower-BMI category.

“We also see a trend to improved reduction in systolic blood pressure in those with the higher BMI,” Dr. Danne said.

Risk for DKA

“The big charm of these drugs is that not only do you improve A1c and all the other good things, but also you do this without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia,” said Dr. Danne. “Again, you can see a trend of a lower risk of severe hypoglycemia for both sotagliflozin doses [compared with placebo] in the group with the body mass index of greater than 27 kg/m2 [versus BMI of less than 27 kg/m2].”

The risk of DKA was higher than placebo in both BMI groups, but the number of DKA events was very small when comparing the low and high body weight categories (0 and 1 events, respectively, in the placebo groups; 7 and 9, in the sotagliflozin 200-mg group; and 9 and 11, in the 400-mg group. The absolute risk difference in the exposure adjusted incidence rate was slightly lower in the lower-BMI group, he said, but the numbers were so small that it is difficult to draw conclusions from that finding.

“There is no doubt that we have an increase for the risk of DKA with this class of drugs in general ... but it is futile to discuss whether or not, just on the basis of a body mass index or something else, we will be able to reduce it in a big fashion,” Dr. Danne suggested.

Body weight and composition

Other data on the long-term effect of sotagliflozin on body weight and composition were presented by Sangeeta Sawhney, MD, vice-president of clinical development at Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

She presented data from the DEXA substudy of the inTandem phase 3 studies in which 243 patients underwent fat mass and bone density scanning.

SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with weight loss through glycuresis and net caloric loss, Dr. Sawhney reminded the audience. As sotagliflozin is a dual inhibitor of SGLT1 and SGLT2, however, it is important to estimate the contribution of changes in fat mass and lean mass to the weight loss that could be achieved with the drug.

Pooled data from the inTandem 1 and inTandem 2 studies showed that at week 24, there were reductions in body weight of –1.7 kg and –2.6 kg with sotagliflozin 200 mg and 400 mg, respectively, and at 52 weeks, reductions of –1.9 kg and –2.9 kg. However, there was an increase in body weight with placebo (+0.5 and +0.8 kg, respectively).

For the substudy, patients underwent dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at baseline and weeks 24 and 52. Fat mass was measured at all three time points, and bone density was evaluated at the start and end of the study.

The least-square mean change in total fat mass from baseline to week 24 and week 52 were +0.6 and +0.1 kg, respectively, for placebo, –1.6 and –1.6 kg for the sotagliflozin 200-mg dose; and –1.9 and –2.1 kg for the 400-mg dose, “which really parallels the reduction in total body weight,” Dr. Sawhney observed.

The changes in total lean mass were much smaller for sotagliflozin, she added, at –0.6 kg at week 24 and 0.3 kg at week 52 for the 200-mg dose, and –0.7 kg and –0.4 kg, respectively, for the 400-mg dose, and rises in lean mass of 0.2 kg and 0.4 kg, respectively, in placebo.

Taken together, these data show that “about 80% of the body weight reduction is really from the fat mass, and a much smaller proportion of the total body weight reduction is really coming from the lean fat mass,” said Dr. Sawhney.

DEPICT with dapagliflozin

In a poster, Paresh Dandona, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and associates presented data from a pooled analysis of the DEPICT-1 and DEPICT-2 studies looking at safety and efficacy outcomes with dapagliflozin according to five BMI categories: less than or equal to 23 kg/m2; greater than 23 kg/m2 to less than or equal to 25 kg/m2; greater than 25 kg/m2 to less than or equal to 27 kg/m2; greater than 27 kg/m2 to less than or equal to 30 kg/m2; and greater than 30 kg/m2.

The pooled analysis included 548 patients treated with dapagliflozin 5 mg and 532 who received placebo. The investigators found that patients with higher BMIs who were treated with dapagliflozin had greater weight loss, showed a trend toward achieving an HbA1c reduction of 5.5 mmol/mol (greater than or equal to 0.5%) or more without the risk of severe hypoglycemia, and had fewer episodes of definite DKA, compared with those with those with lower BMIs.

The adjusted mean percentage change from baseline in body weight in the lowest BMI (less than or equal to 23 kg/m2) group at week 24 was +0.06 kg for placebo and –2.71 kg for dapagliflozin, and at week 52, +0.33 kg and –2.91 kg, respectively. Corresponding values comparing placebo and dapagliflozin at 24 and 52 weeks in the highest BMI group (greater than 30 kg/m2) were –0.30 kg and –3.03 kg, and +0.56 and –3.58 kg.