User login

Systemic Epstein-Barr Virus–Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

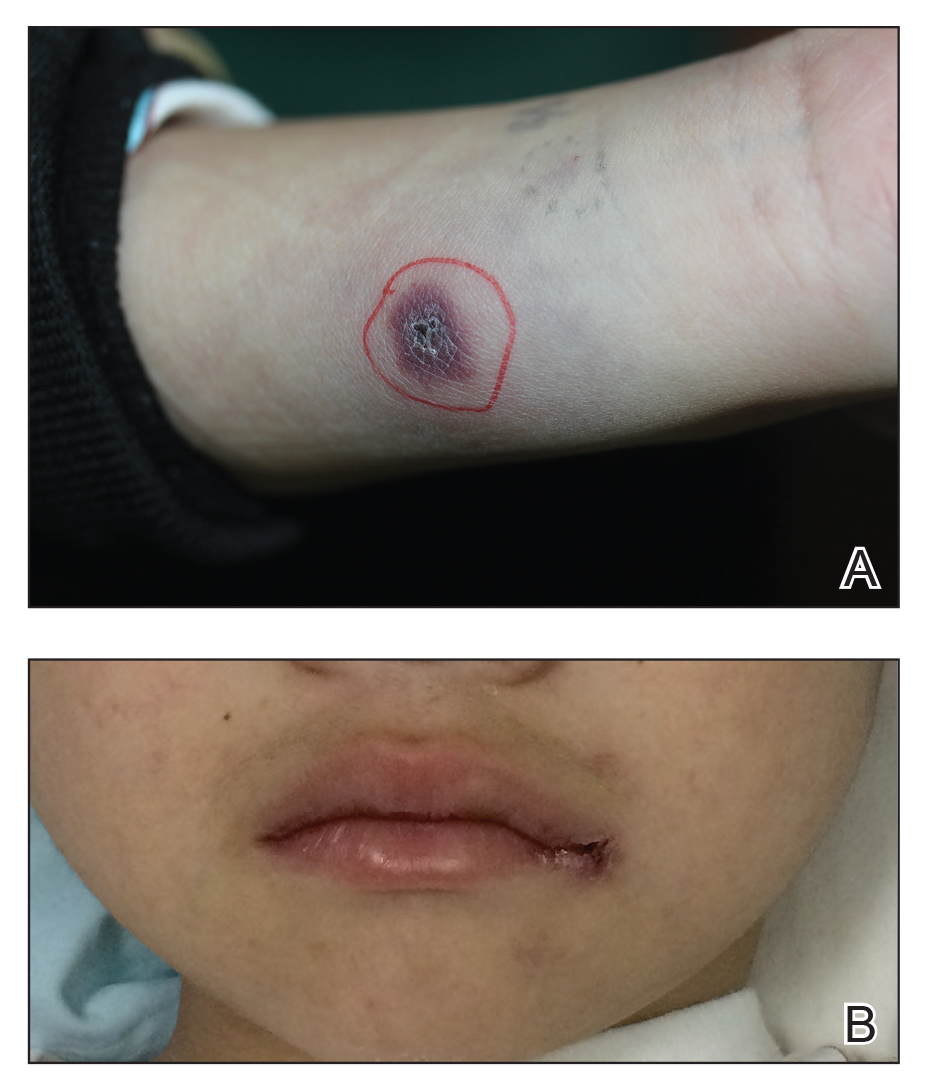

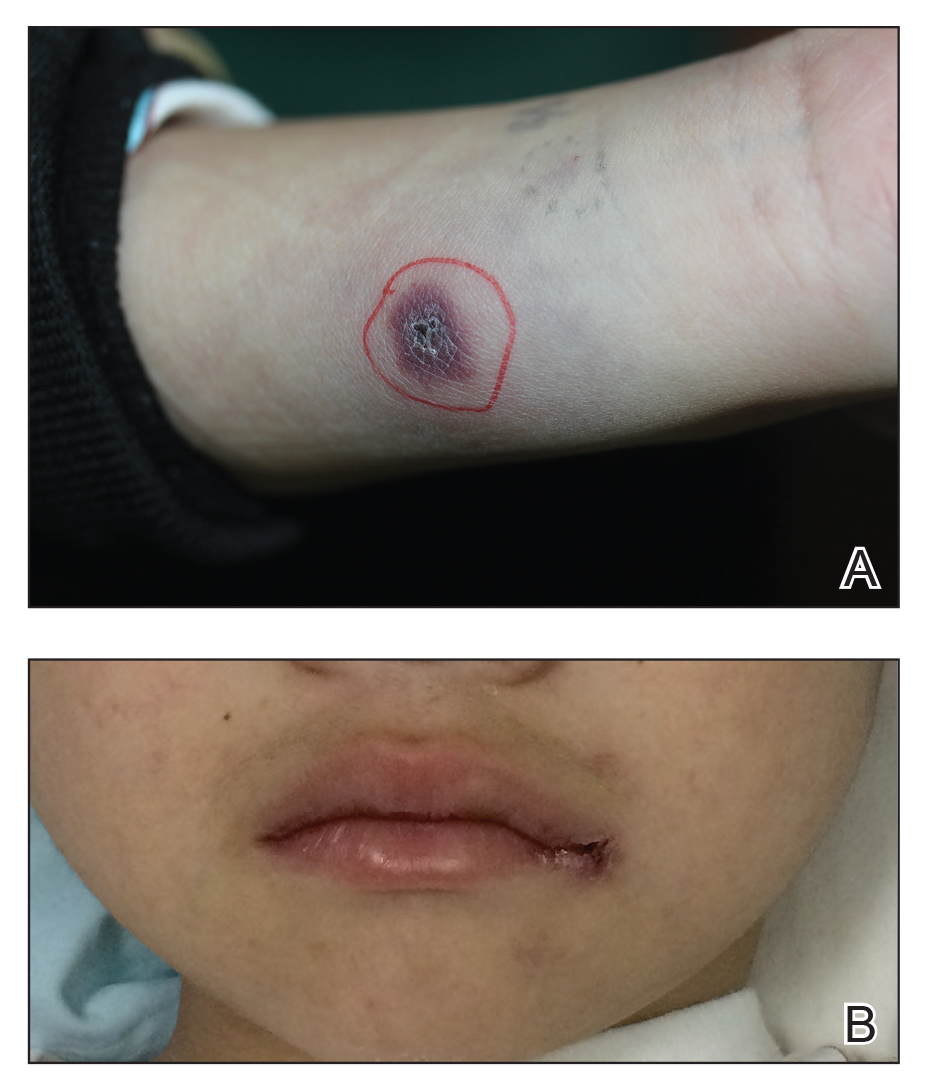

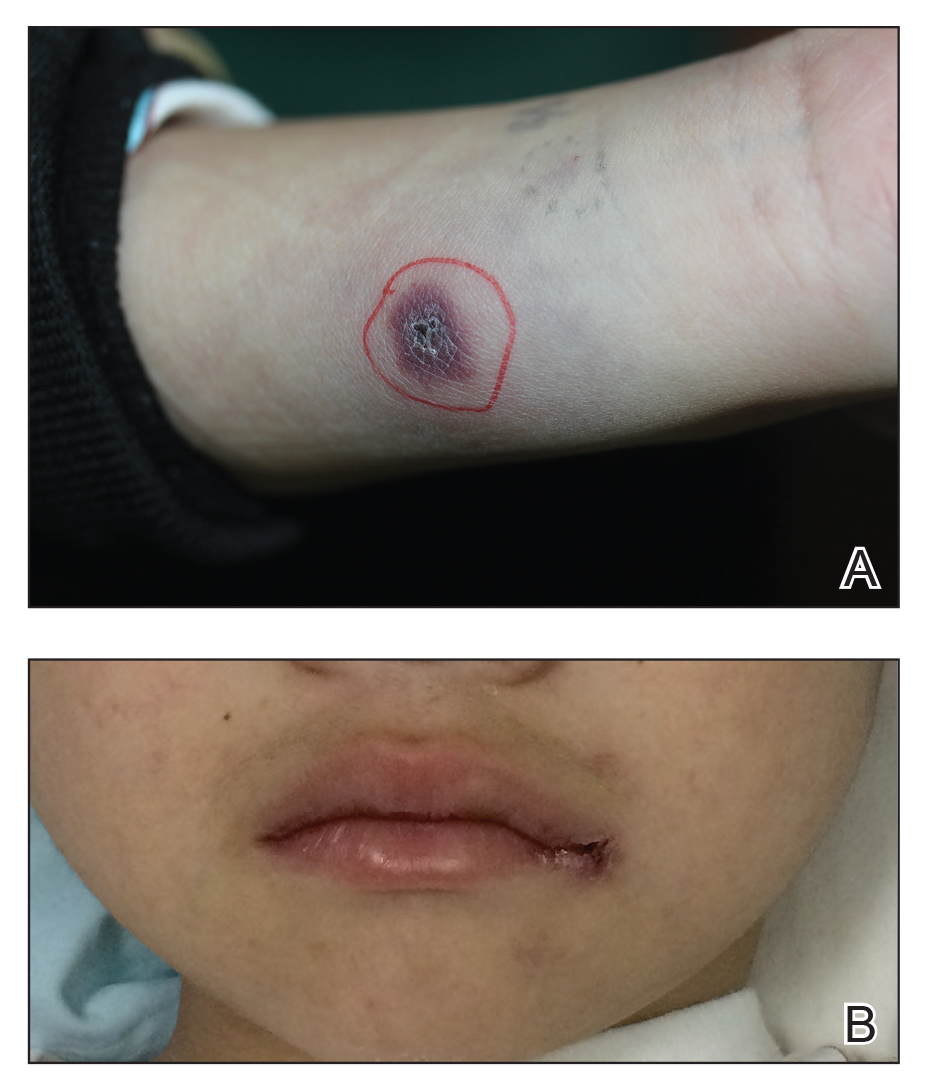

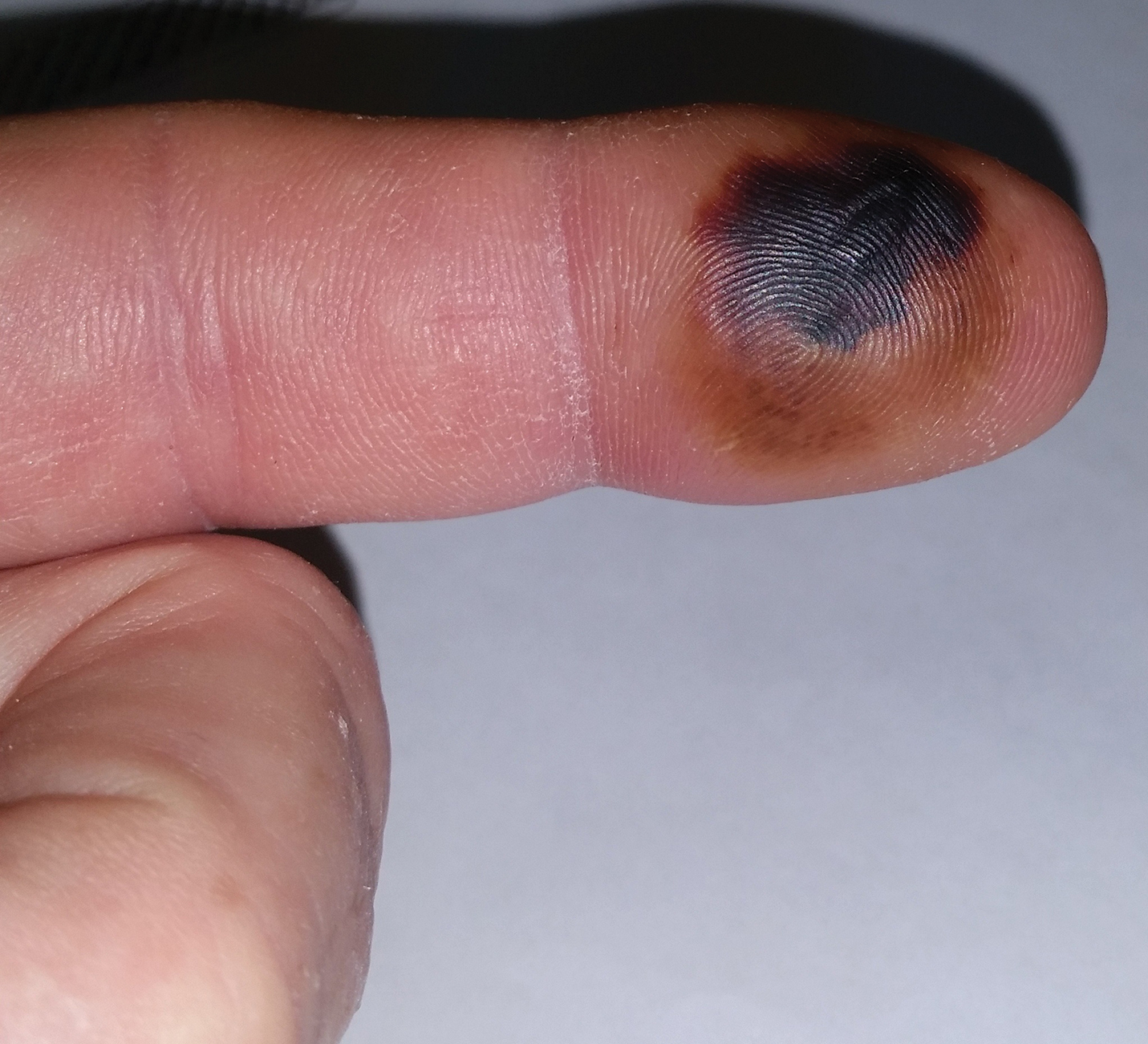

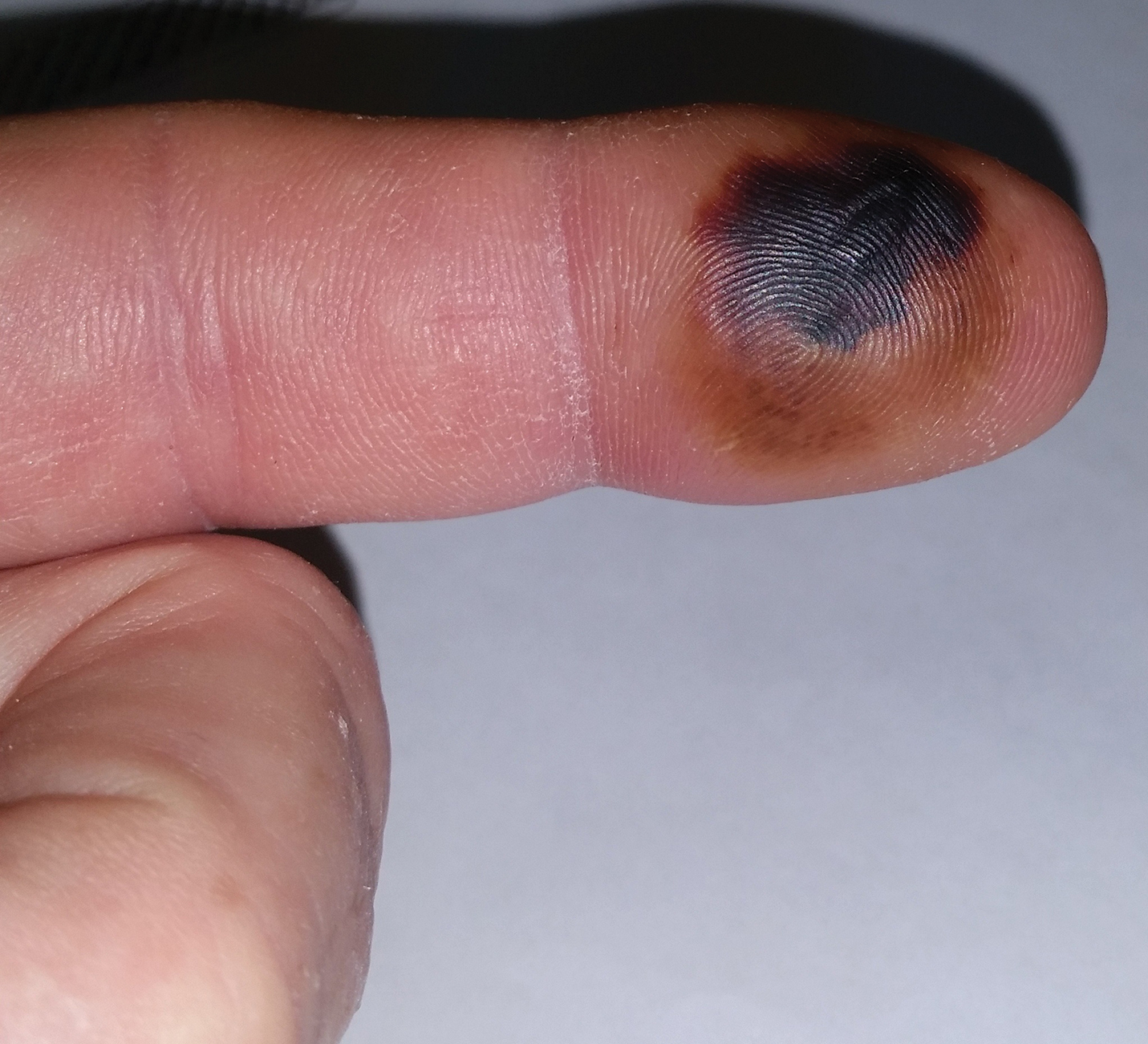

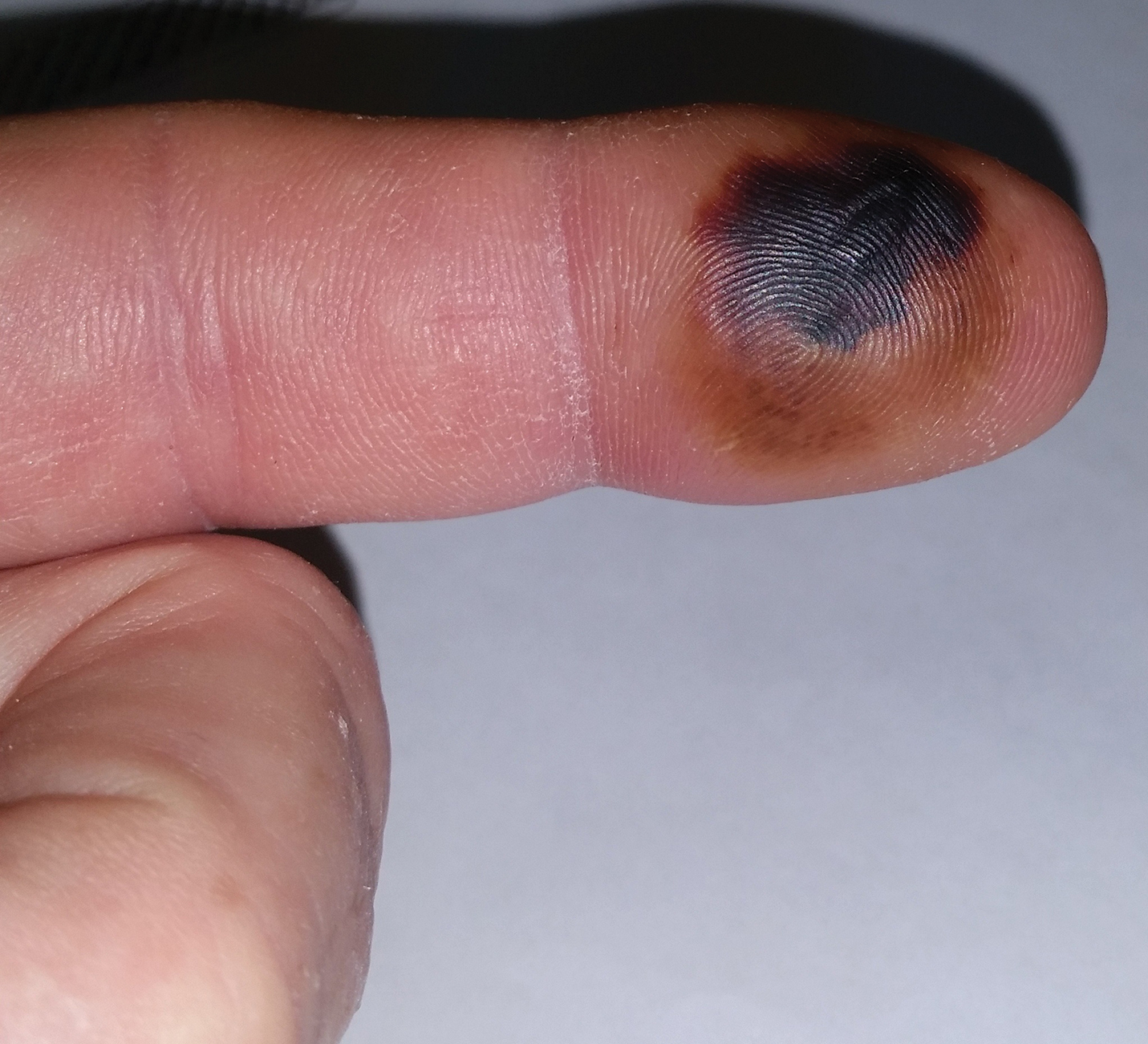

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

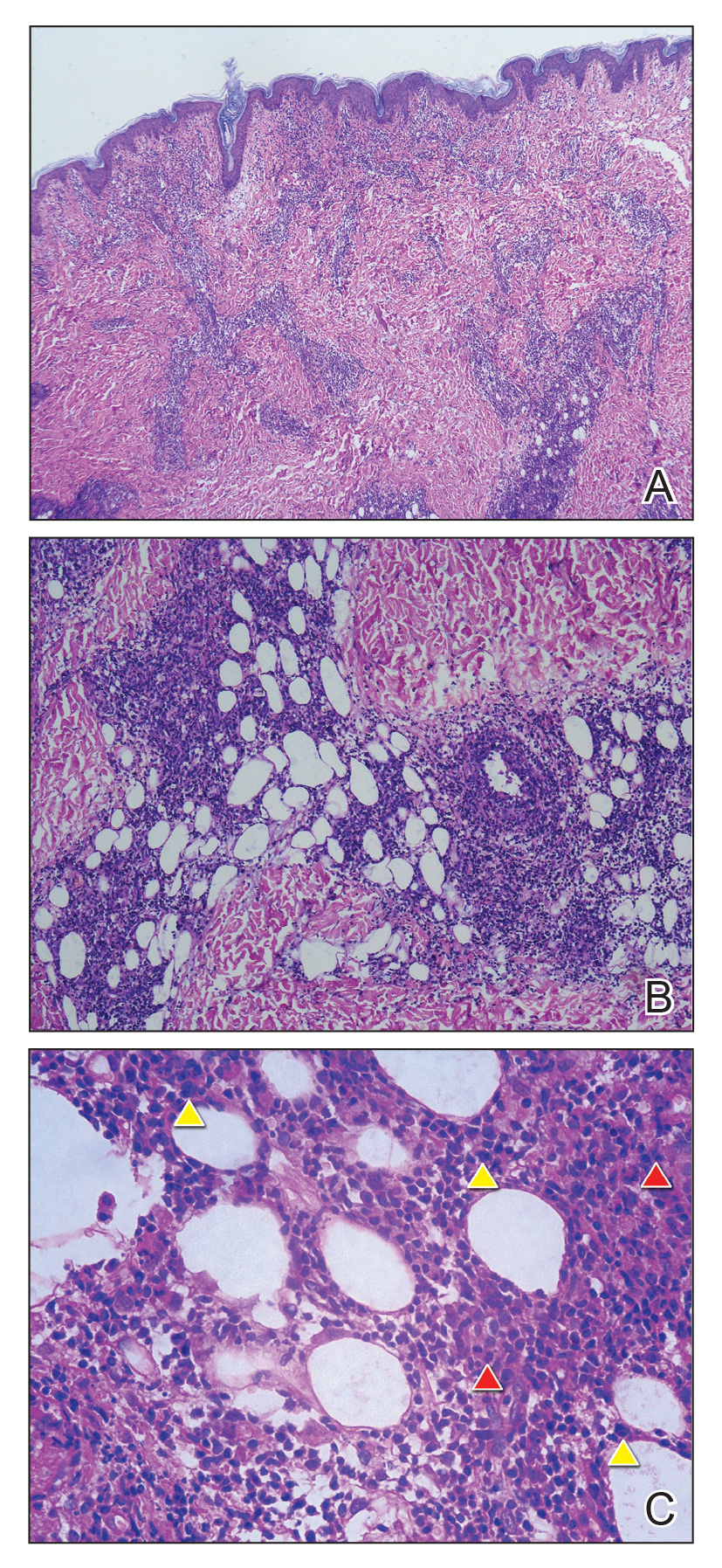

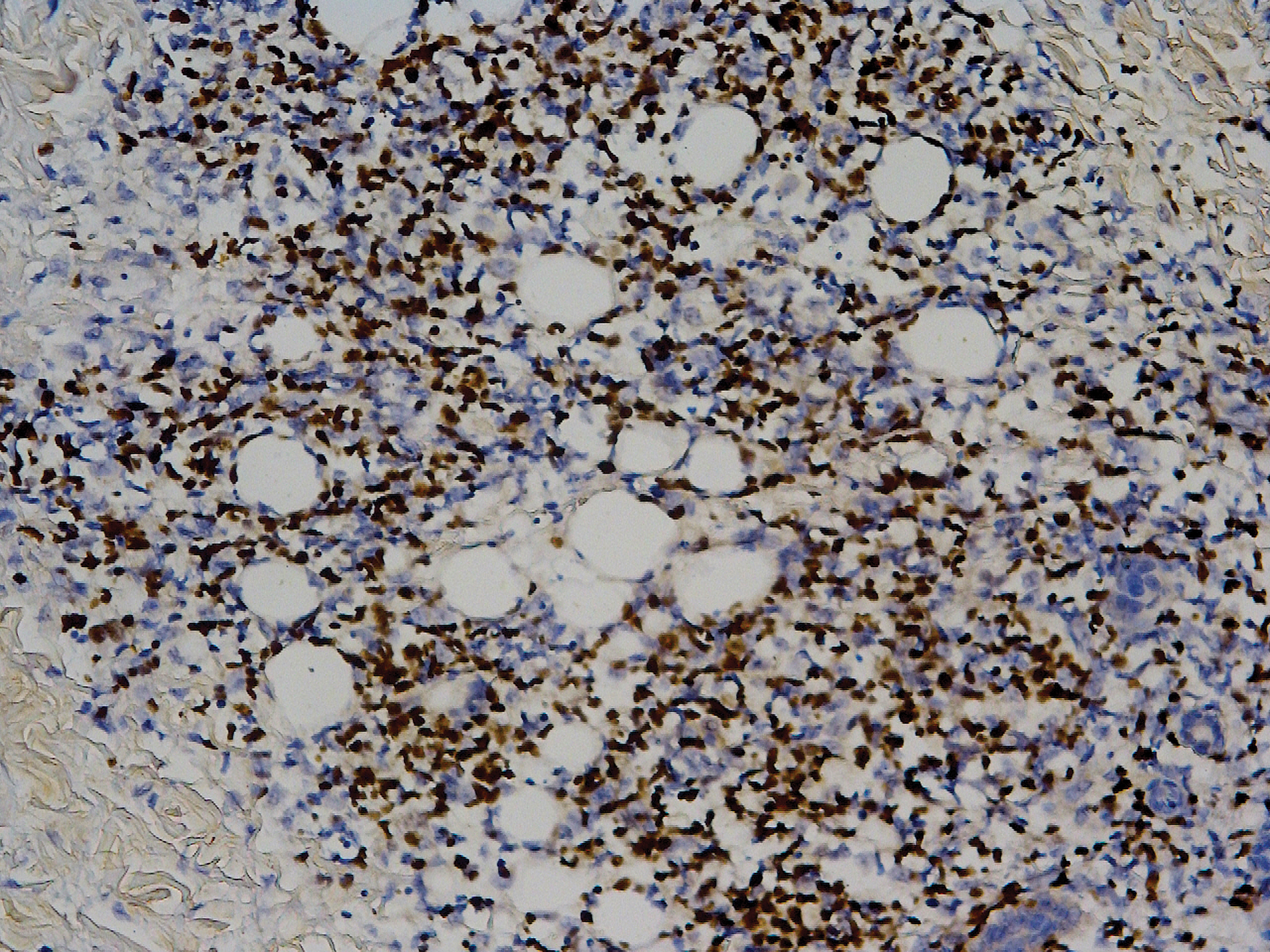

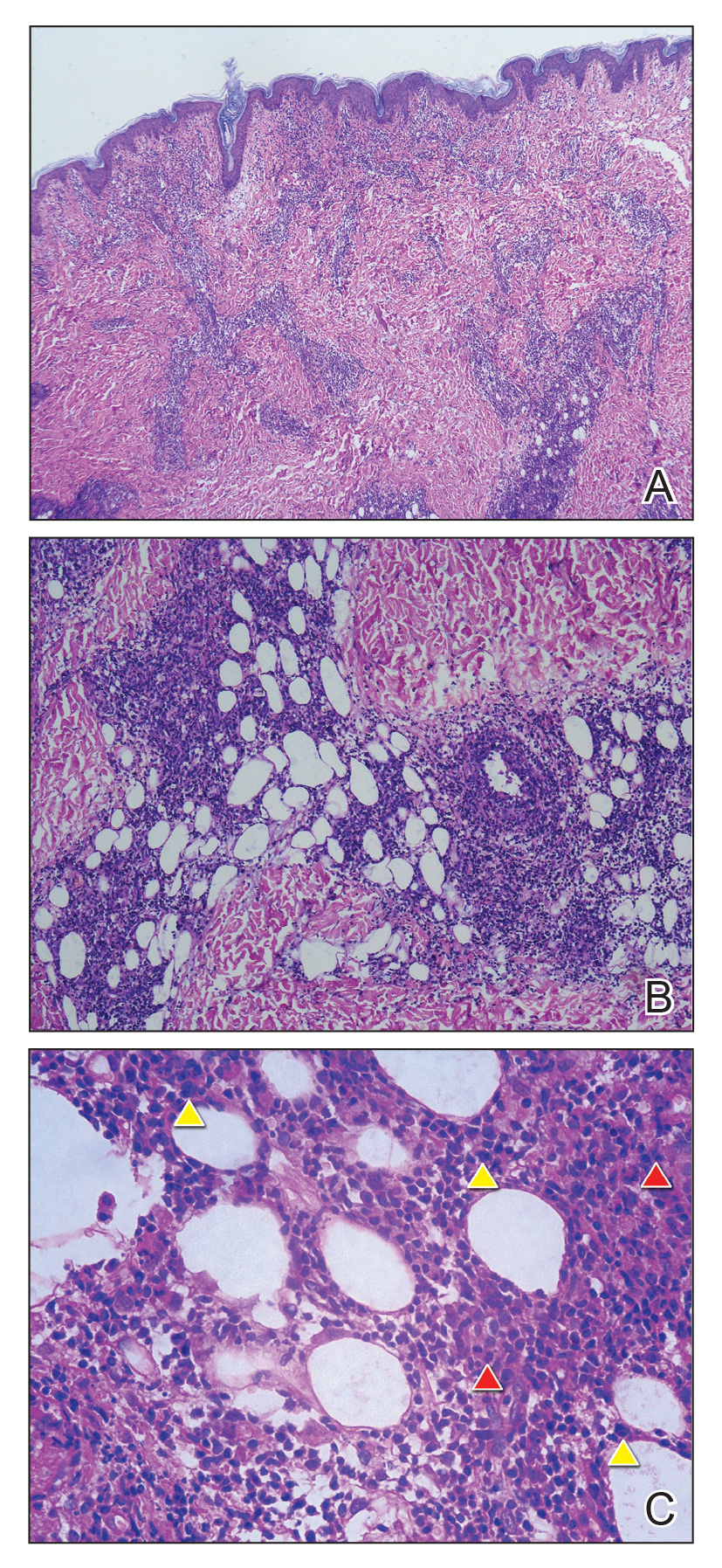

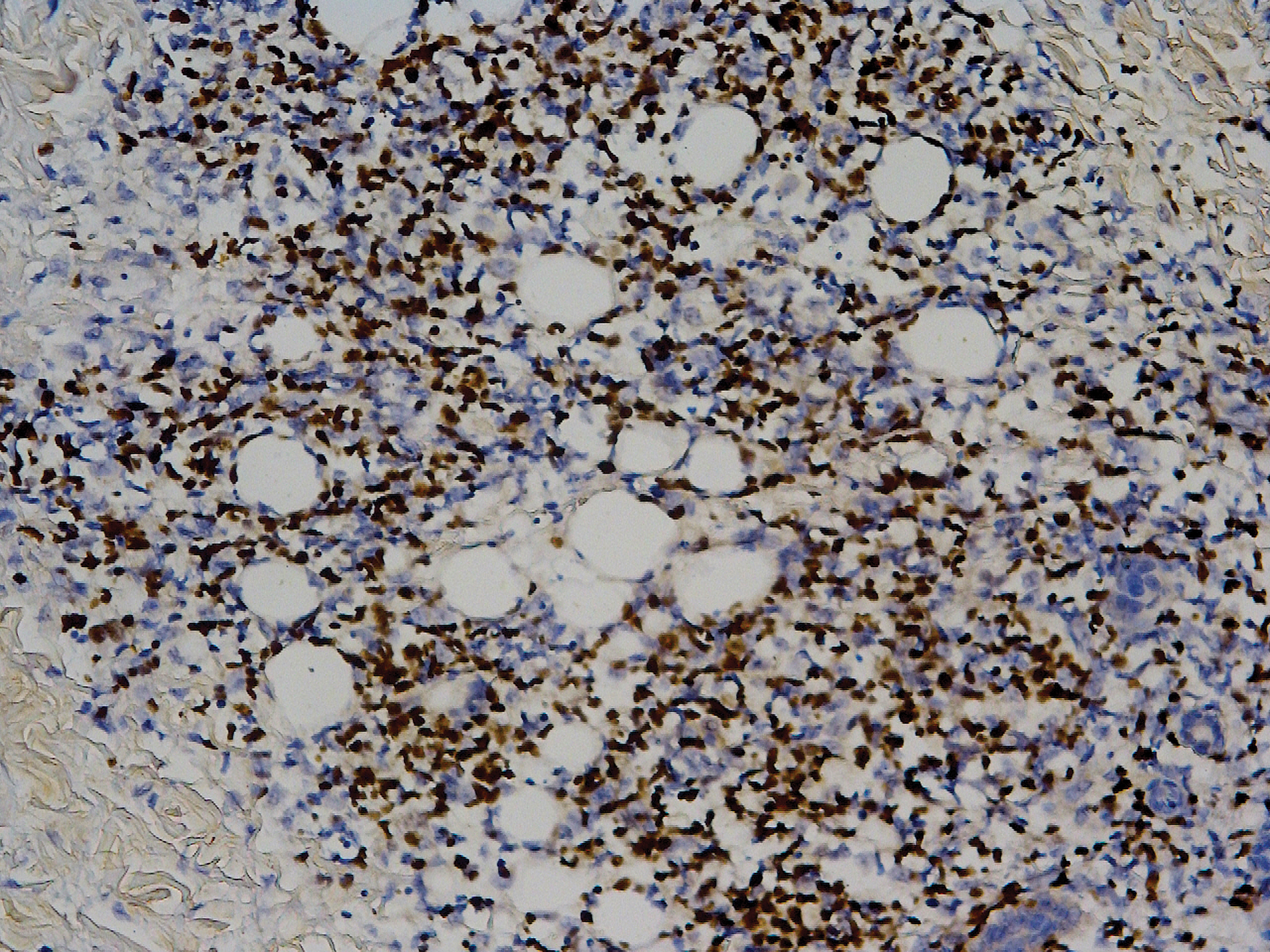

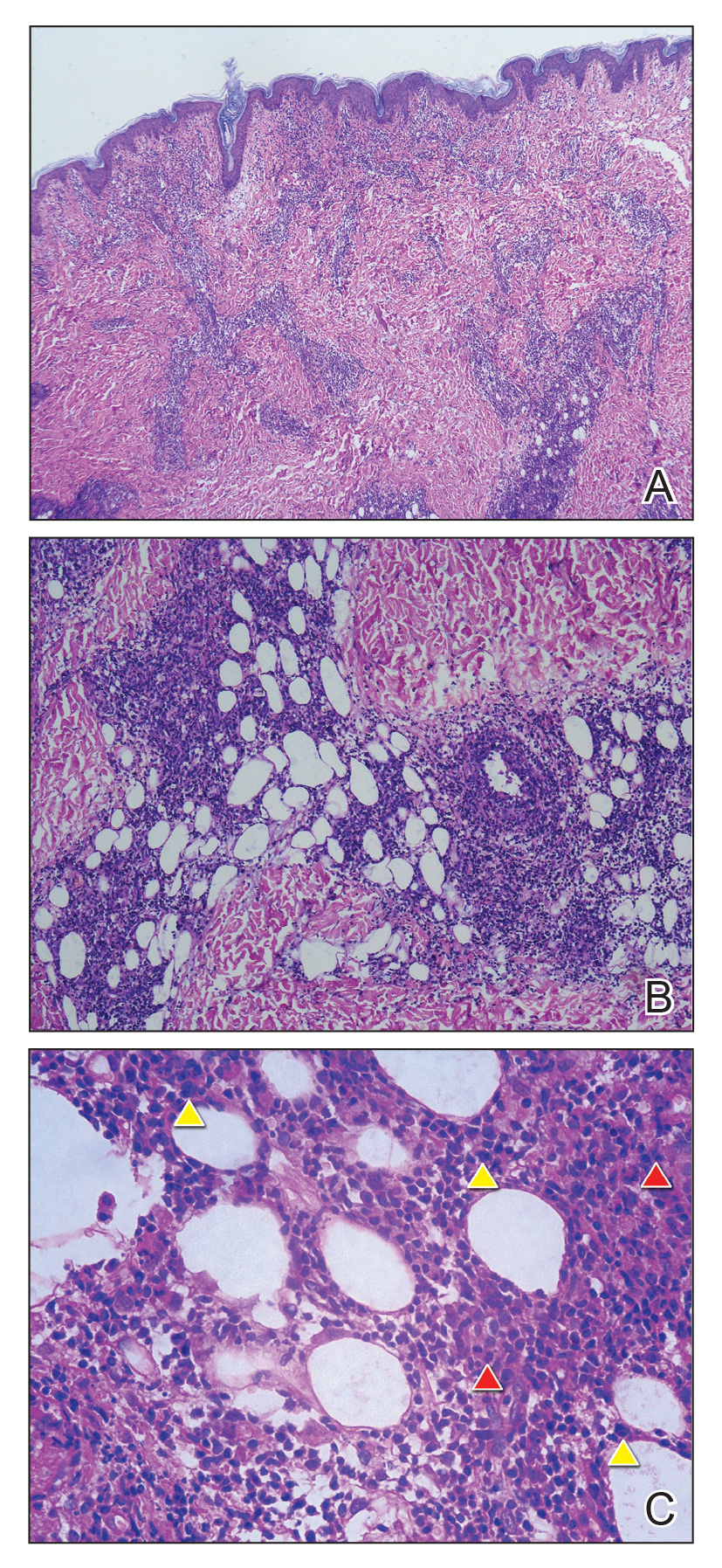

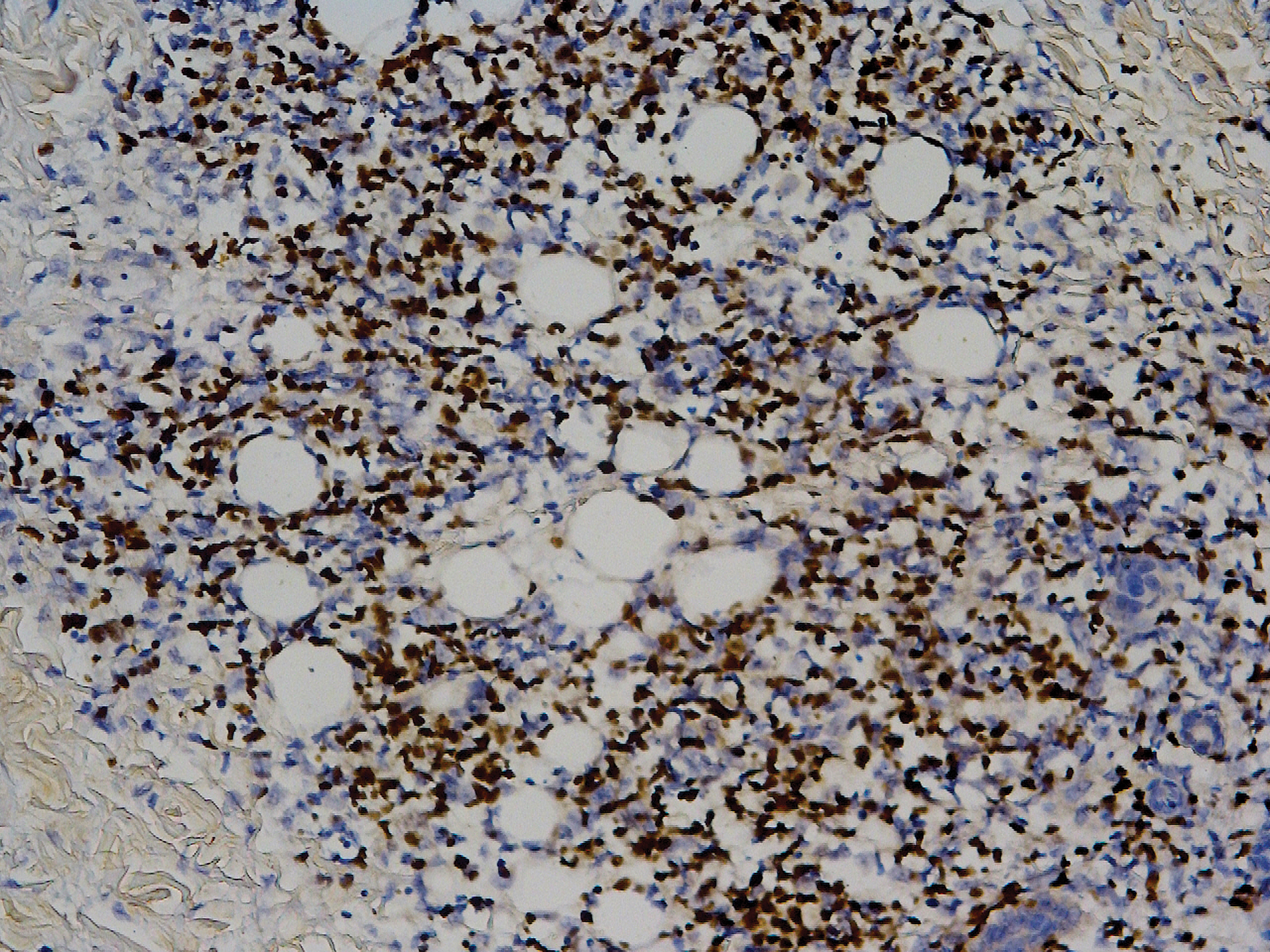

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.

- Huang W, Lv N, Ying J, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of four cases of EBV positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood in China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4991-4999.

- Tabanelli V, Agostinelli C, Sabattini E, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr-virus-positive T cell lymphoproliferative childhood disease in a 22-year-old Caucasian man: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:218.

- Kim DH, Kim M, Kim Y, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with good response to steroid therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:e497-e500.

- Arai A, Yamaguchi T, Komatsu H, et al. Infectious mononucleosis accompanied by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells and infection of CD8-positive cells. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:671-675.

- Smith MC, Cohen DN, Greig B, et al. The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5738-5749.

- Paik JH, Choe JY, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein-Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:53-63.

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.

- Huang W, Lv N, Ying J, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of four cases of EBV positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood in China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4991-4999.

- Tabanelli V, Agostinelli C, Sabattini E, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr-virus-positive T cell lymphoproliferative childhood disease in a 22-year-old Caucasian man: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:218.

- Kim DH, Kim M, Kim Y, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with good response to steroid therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:e497-e500.

- Arai A, Yamaguchi T, Komatsu H, et al. Infectious mononucleosis accompanied by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells and infection of CD8-positive cells. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:671-675.

- Smith MC, Cohen DN, Greig B, et al. The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5738-5749.

- Paik JH, Choe JY, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein-Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:53-63.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.

- Huang W, Lv N, Ying J, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of four cases of EBV positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood in China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4991-4999.

- Tabanelli V, Agostinelli C, Sabattini E, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr-virus-positive T cell lymphoproliferative childhood disease in a 22-year-old Caucasian man: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:218.

- Kim DH, Kim M, Kim Y, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with good response to steroid therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:e497-e500.

- Arai A, Yamaguchi T, Komatsu H, et al. Infectious mononucleosis accompanied by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells and infection of CD8-positive cells. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:671-675.

- Smith MC, Cohen DN, Greig B, et al. The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5738-5749.

- Paik JH, Choe JY, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein-Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:53-63.

Practice Points

- Systemic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a fulminant illness with a predilection for Asians and indigenous populations from Mexico and Central and South America. In most patients, the disease has an aggressive clinical course with high mortality.

- The disease often is complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. When these severe complications are absent, the prognosis might be better.

- In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA and for T-cell receptor gene rearrangements is an important tool to establish the diagnosis as well as for treatment options and predicting the prognosis.

Seborrhea Herpeticum: Cutaneous Herpes Simplex Virus Infection Within Infantile Seborrheic Dermatitis

Classically, eczema herpeticum is associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), but it also has been previously reported in the setting of pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, burns, psoriasis, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Descriptions of cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) in the setting of seborrheic dermatitis are lacking.

Case Report

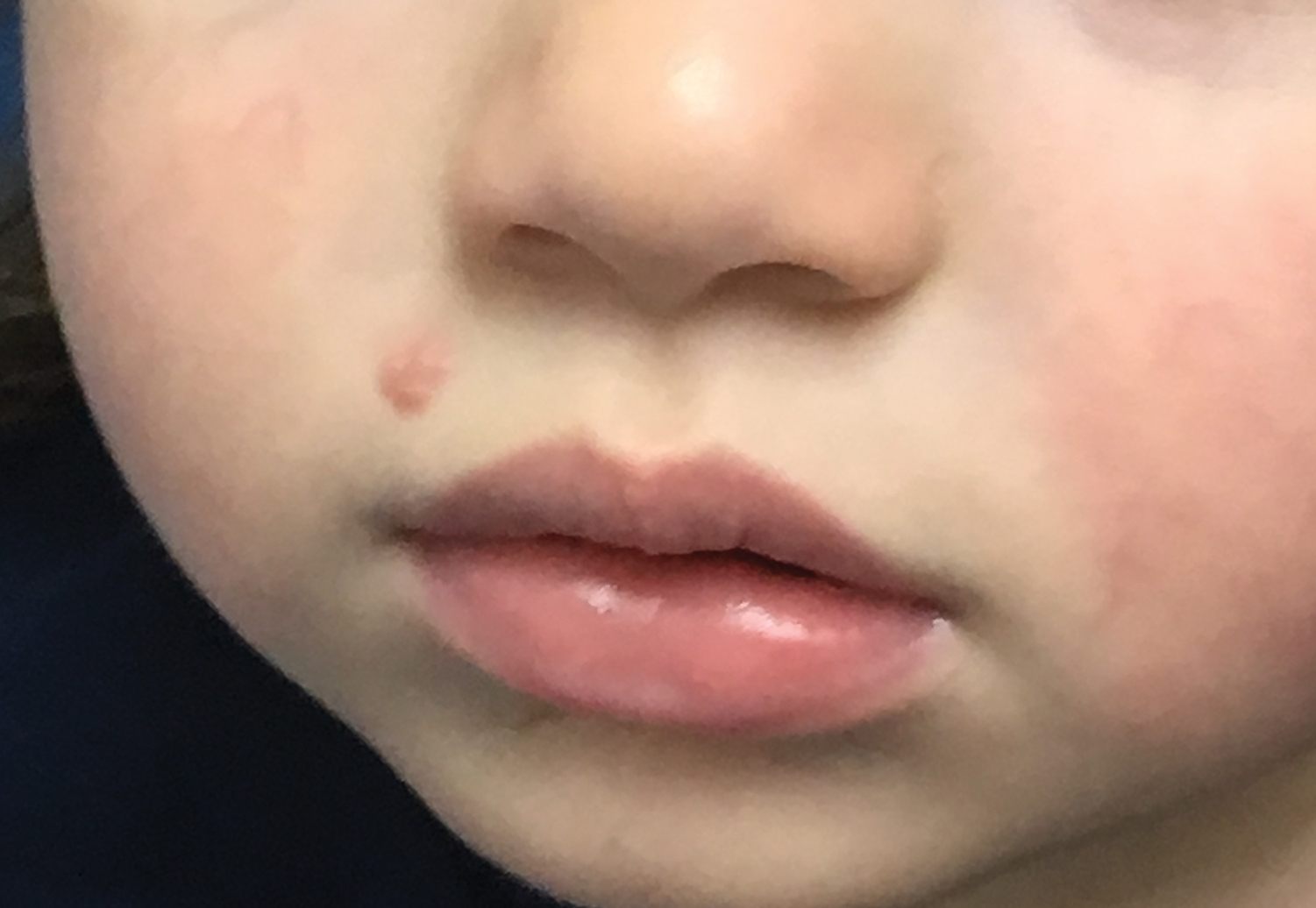

A 2-month-old infant boy who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with a new rash on the scalp. Initially there were a few clusters of small fluid-filled lesions that evolved over several days into diffuse clusters covering the scalp and extending onto the forehead and upper chest (Figure). The patient’s medical history was notable for infantile seborrheic dermatitis and a family history of AD. His grandmother, who was his primary caretaker, had a recent history of herpes labialis.

Physical examination revealed numerous discrete, erythematous, and punched-out erosions diffusely on the scalp. There were fewer similar erosions on the forehead and upper chest. There were no oral or periocular lesions. There were no areas of lichenification or eczematous plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Laboratory testing was positive for HSV type 1 polymerase chain reaction and positive for HSV type 1 viral culture. Liver enzymes were elevated with alanine aminotransferase at 107 U/L (reference range, 7–52 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase at 94 U/L (reference range, 13–39 U/L).

The patient was admitted to the hospital and was treated by the dermatology and infectious disease services. Intravenous acyclovir 60 mg/kg daily was administered for 3 days until all lesions had crusted over. On the day of discharge, the patient was transitioned to oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily for 7 days with resolution. One month later he developed a recurrence that was within his existing seborrheic dermatitis. After a repeat 7-day course of oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily, he was placed on prophylaxis therapy of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg daily. Gentle skin care precautions also were recommended.

Comment

Eczema herpeticum refers to disseminated cutaneous infection with HSV types 1 or 2 in the setting of underlying dermatosis.2 Although it is classically associated with AD, it has been reported in a number of other chronic skin disorders and can lead to serious complications, including hepatitis, keratoconjunctivitis, and meningitis. In those with AD who develop HSV, presentation may occur in active dermatitis locations because of skin barrier disruption, which may lead to increased susceptibility to viral infection.3

Herpes simplex virus in a background of seborrheic dermatitis has not been well described. Although the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis has not been fully reported, several gene mutations and protein deficiencies have been identified in patients and animal models that are associated with immune response or epidermal differentiation.4 Therefore, it is possible that, as with AD, a disruption in the skin barrier increases susceptibility to viral infection.

It also has been suggested that infantile seborrheic dermatitis and AD represent the same spectrum of disease.5 Given our patient’s family history of AD, it is possible his presentation represents early underlying AD. Providers should be aware that cutaneous HSV can be confined to a seborrheic distribution and may represent underlying epidermal dysfunction secondary to seborrheic dermatitis.

- Wheeler CE, Abele DC. Eczema herpeticum, primary and recurrent. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:162-173.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger BR, Nigra TP. Psoriasis herpeticum: three cases of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:52-56.

- Wollenberg A, Wetzel S, Burgdorf WH, et al. Viral infections in atopic dermatitis: pathogenic aspects and clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:667-674.

- Karakadze M, Hirt P, Wikramanayake T. The genetic basis of seborrhoeic dermatitis: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;32:529-536.

- Alexopoulos A, Kakourou T, Orfanou I, et al. Retrospective analysis of the relationship between infantile seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;31:125-130.

Classically, eczema herpeticum is associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), but it also has been previously reported in the setting of pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, burns, psoriasis, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Descriptions of cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) in the setting of seborrheic dermatitis are lacking.

Case Report

A 2-month-old infant boy who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with a new rash on the scalp. Initially there were a few clusters of small fluid-filled lesions that evolved over several days into diffuse clusters covering the scalp and extending onto the forehead and upper chest (Figure). The patient’s medical history was notable for infantile seborrheic dermatitis and a family history of AD. His grandmother, who was his primary caretaker, had a recent history of herpes labialis.

Physical examination revealed numerous discrete, erythematous, and punched-out erosions diffusely on the scalp. There were fewer similar erosions on the forehead and upper chest. There were no oral or periocular lesions. There were no areas of lichenification or eczematous plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Laboratory testing was positive for HSV type 1 polymerase chain reaction and positive for HSV type 1 viral culture. Liver enzymes were elevated with alanine aminotransferase at 107 U/L (reference range, 7–52 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase at 94 U/L (reference range, 13–39 U/L).

The patient was admitted to the hospital and was treated by the dermatology and infectious disease services. Intravenous acyclovir 60 mg/kg daily was administered for 3 days until all lesions had crusted over. On the day of discharge, the patient was transitioned to oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily for 7 days with resolution. One month later he developed a recurrence that was within his existing seborrheic dermatitis. After a repeat 7-day course of oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily, he was placed on prophylaxis therapy of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg daily. Gentle skin care precautions also were recommended.

Comment

Eczema herpeticum refers to disseminated cutaneous infection with HSV types 1 or 2 in the setting of underlying dermatosis.2 Although it is classically associated with AD, it has been reported in a number of other chronic skin disorders and can lead to serious complications, including hepatitis, keratoconjunctivitis, and meningitis. In those with AD who develop HSV, presentation may occur in active dermatitis locations because of skin barrier disruption, which may lead to increased susceptibility to viral infection.3

Herpes simplex virus in a background of seborrheic dermatitis has not been well described. Although the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis has not been fully reported, several gene mutations and protein deficiencies have been identified in patients and animal models that are associated with immune response or epidermal differentiation.4 Therefore, it is possible that, as with AD, a disruption in the skin barrier increases susceptibility to viral infection.

It also has been suggested that infantile seborrheic dermatitis and AD represent the same spectrum of disease.5 Given our patient’s family history of AD, it is possible his presentation represents early underlying AD. Providers should be aware that cutaneous HSV can be confined to a seborrheic distribution and may represent underlying epidermal dysfunction secondary to seborrheic dermatitis.

Classically, eczema herpeticum is associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), but it also has been previously reported in the setting of pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, ichthyosis vulgaris, burns, psoriasis, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Descriptions of cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) in the setting of seborrheic dermatitis are lacking.

Case Report

A 2-month-old infant boy who was otherwise healthy presented to the emergency department with a new rash on the scalp. Initially there were a few clusters of small fluid-filled lesions that evolved over several days into diffuse clusters covering the scalp and extending onto the forehead and upper chest (Figure). The patient’s medical history was notable for infantile seborrheic dermatitis and a family history of AD. His grandmother, who was his primary caretaker, had a recent history of herpes labialis.

Physical examination revealed numerous discrete, erythematous, and punched-out erosions diffusely on the scalp. There were fewer similar erosions on the forehead and upper chest. There were no oral or periocular lesions. There were no areas of lichenification or eczematous plaques on the remainder of the trunk or extremities. Laboratory testing was positive for HSV type 1 polymerase chain reaction and positive for HSV type 1 viral culture. Liver enzymes were elevated with alanine aminotransferase at 107 U/L (reference range, 7–52 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase at 94 U/L (reference range, 13–39 U/L).

The patient was admitted to the hospital and was treated by the dermatology and infectious disease services. Intravenous acyclovir 60 mg/kg daily was administered for 3 days until all lesions had crusted over. On the day of discharge, the patient was transitioned to oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily for 7 days with resolution. One month later he developed a recurrence that was within his existing seborrheic dermatitis. After a repeat 7-day course of oral valacyclovir 20 mg/kg daily, he was placed on prophylaxis therapy of oral acyclovir 10 mg/kg daily. Gentle skin care precautions also were recommended.

Comment

Eczema herpeticum refers to disseminated cutaneous infection with HSV types 1 or 2 in the setting of underlying dermatosis.2 Although it is classically associated with AD, it has been reported in a number of other chronic skin disorders and can lead to serious complications, including hepatitis, keratoconjunctivitis, and meningitis. In those with AD who develop HSV, presentation may occur in active dermatitis locations because of skin barrier disruption, which may lead to increased susceptibility to viral infection.3

Herpes simplex virus in a background of seborrheic dermatitis has not been well described. Although the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis has not been fully reported, several gene mutations and protein deficiencies have been identified in patients and animal models that are associated with immune response or epidermal differentiation.4 Therefore, it is possible that, as with AD, a disruption in the skin barrier increases susceptibility to viral infection.

It also has been suggested that infantile seborrheic dermatitis and AD represent the same spectrum of disease.5 Given our patient’s family history of AD, it is possible his presentation represents early underlying AD. Providers should be aware that cutaneous HSV can be confined to a seborrheic distribution and may represent underlying epidermal dysfunction secondary to seborrheic dermatitis.

- Wheeler CE, Abele DC. Eczema herpeticum, primary and recurrent. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:162-173.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger BR, Nigra TP. Psoriasis herpeticum: three cases of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:52-56.

- Wollenberg A, Wetzel S, Burgdorf WH, et al. Viral infections in atopic dermatitis: pathogenic aspects and clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:667-674.

- Karakadze M, Hirt P, Wikramanayake T. The genetic basis of seborrhoeic dermatitis: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;32:529-536.

- Alexopoulos A, Kakourou T, Orfanou I, et al. Retrospective analysis of the relationship between infantile seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;31:125-130.

- Wheeler CE, Abele DC. Eczema herpeticum, primary and recurrent. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:162-173.

- Santmyire-Rosenberger BR, Nigra TP. Psoriasis herpeticum: three cases of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:52-56.

- Wollenberg A, Wetzel S, Burgdorf WH, et al. Viral infections in atopic dermatitis: pathogenic aspects and clinical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:667-674.

- Karakadze M, Hirt P, Wikramanayake T. The genetic basis of seborrhoeic dermatitis: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;32:529-536.

- Alexopoulos A, Kakourou T, Orfanou I, et al. Retrospective analysis of the relationship between infantile seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;31:125-130.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous herpes simplex virus may present in a seborrheic distribution within infantile seborrheic dermatitis, suggesting underlying dysfunction secondary to seborrheic dermatitis.

- Treatment of seborrhea herpeticum involves antiviral therapy to treat the secondary viral infection and gentle skin care precautions for the primary condition.

Pediatric Molluscum: An Update

Molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) infection causes the cutaneous lesions we call molluscum. Molluscum has become common in the last 30 years. Deciding the best course of therapy requires some fundamental understanding about how MCV relates to the following factors: epidemiology, childhood immunity and vaccination, clinical features, comorbidities, and quality of life. Treatment depends on many factors, including presence or absence of atopic dermatitis (AD) and/or pruritus, other symptoms, cosmetic location, and the child’s concern about the lesions. Therapeutics include destructive and immunologic therapies, the latter geared toward increasing immune response.

Epidemiology

Molluscum contagiosum virus is the solo member of the Molluscipoxvirus genus. Infection with MCV causes benign growth or tumors in the skin (ie, molluscum). The infection is slow to clear because the virus reduces the host’s immunity.1,2 Molluscum contagiosum virus is a double-stranded DNA virus that affects keratinocytes and genetically carries the tools for its own replication (ie, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase). The virus has a few subtypes—I/Ia, II, III, and IV—with MCV-I predominating in children and healthy humans and MCV-II in patients with human immunodeficiency virus.1,2 Typing is experimental and is not standardly performed in clinical practice. Molluscum contagiosum virus produces a variety of factors that block the host’s immune response, prolonging infection and preventing erythema and inflammatory response.3

Molluscum contagiosum virus is transmitted through skin-to-skin contact and fomites, including shared towels, bathtubs, spas, bath sponges, and pool equipment.2,4,5 Transmission from household contact and bathing together has been noted in pediatric patients with MCV. Based on the data it can be posited that the lesions are softer when wet and more readily release viral particles or fomites, and fomites may be left on surfaces, especially when a child is wet.6,7 Propensity for infection occurs in patients with AD and in immunosuppressed hosts, including children with human immunodeficiency virus and iatrogenic immunosuppression caused by chemotherapy.1,2,8 Contact sports can increase the risk of transmission, and outbreaks have occurred in pools,5,9 day-care facilities,10 and sports settings.11 Cases of congenital and vertically transmitted molluscum have been documented.12,13 Sexual transmission of MCV may be seen in adolescents who are sexually active. Although child-to-child transmission can occur in the groin area from shared equipment, transmission via sexual abuse also is possible.14 Bargman15 has mentioned the isolated genital location and lack of contact with other infected children as concerning features. Latency of new lesion appearance is anywhere from 1 to 50 days from the date of inoculation; therefore, new lesions are possible and expected even after therapy has been effective in eradicating visible lesions.10 Although clearance has been reported in 6 to 12 months, one pediatric study demonstrated 70% clearance by 1.5 years, suggesting the disease often is more prolonged.16 One-third of children will experience signs of inflammation, such as pruritus and/or erythema. Rare side effects include bacterial superinfection and hypersensitivity.2

One Dutch study from 1994, the largest database survey of children to date, cited a 17% cumulative incidence of molluscum in children by reviewing the data from 103 general practices.17 In a survey and review of molluscum by Braue et al,18 annual rates in populations vary but seem to maximize at approximately 6% to 7%. Sturt et al19 reviewed the prevalence in the indigenous West Sepik section of New Guinea and noted annual incidence rates of 6% in children younger than 10 years (range, 1.8%–10.9%). Epidemics occur and can produce large numbers of cases in a short time period.18 The cumulative prevalence in early childhood may be as high as 22%, as Sturt et al19 observed in children younger than 10 years.

Rising incidence and therefore rising lifetime prevalence appear to have been an issue in the last few decades. Data from the Indian Health Service have demonstrated increases in MCV in Native American children between 2001 and 2005.20 In adults, the data support a steady increase of molluscum from 1988-2007, with a 3-fold increase from 1988-1997 to 1998-2007 in a Spanish study.21 Better population-based data are needed.

Childhood Immunity and Vaccination

Sequence homology between MC133L, a protein of MCV, with vaccinia virus suggests overlapping genes.22 Therefore, it is conceptually possible that the rise in incidence of MCV since the 1980s relates to the loss of herd immunity to variola due to lack of vaccination for smallpox, which has not been offered in the United States since 1972.23 Childhood immunity to MCV varies among studies, but it appears that children do develop antibodies to molluscum in the setting of forming an immune response. Because the rise in molluscum incidence began after the smallpox vaccine was discontinued, the factors appear related; however, the scientific data do not support the theory of a relationship. Mitchell24 has shown that a patient can develop antibodies in response to ground molluscum bodies inoculated into the skin; however, vaccination against molluscum and natural infection do not appear to produce antibodies that would cross-react and protect against other poxviruses, including vaccinia or fowl pox infections.25 Cell-mediated immunity also is required to clear MCV and may account for the inflammatory appearance of lesions as they resolve.26

Demonstrated factors that account for the rise in MCV incidence, aside from alterations in vaccination practices, include spread through sports,9 swimming,11 and AD,7 which have become more commonplace in the United States in the last few decades, supporting the theory that they may be the cause of the increase in childhood MCV infections. Another cause may be the ability of MCV to create factors that stem host immune response.1

Clinical Features

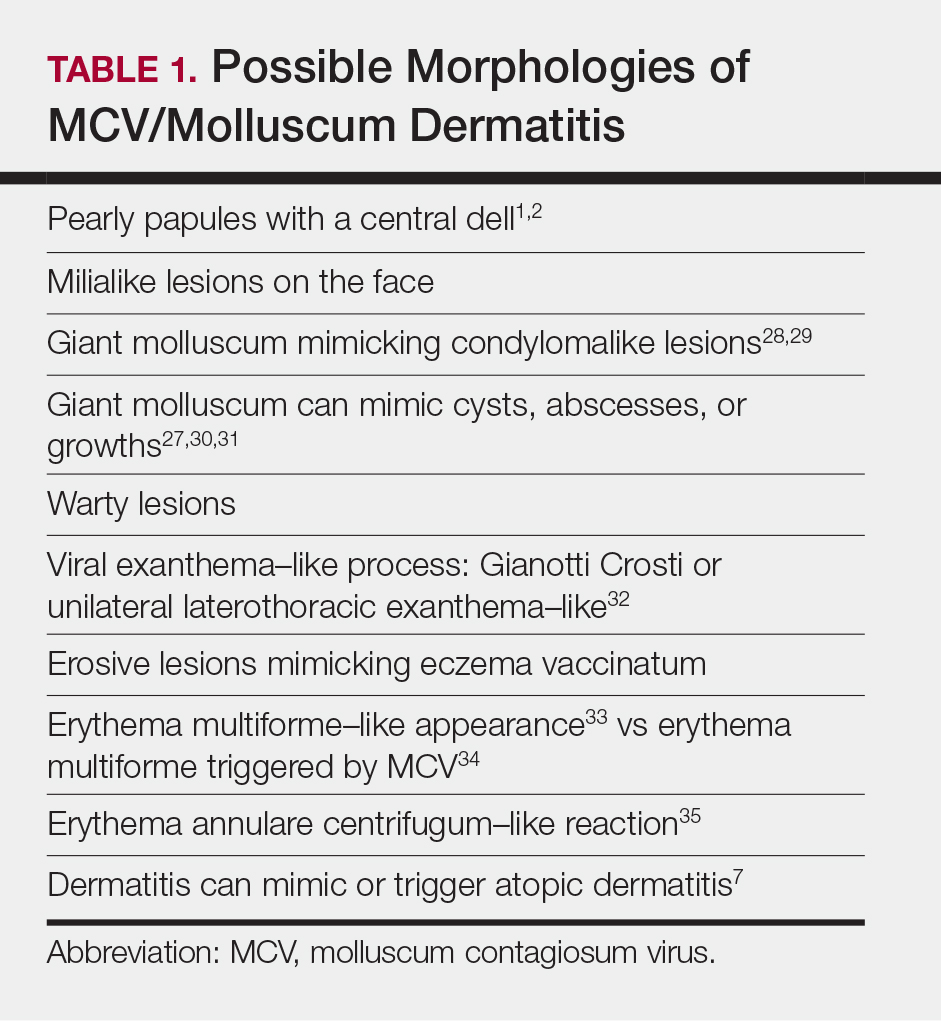

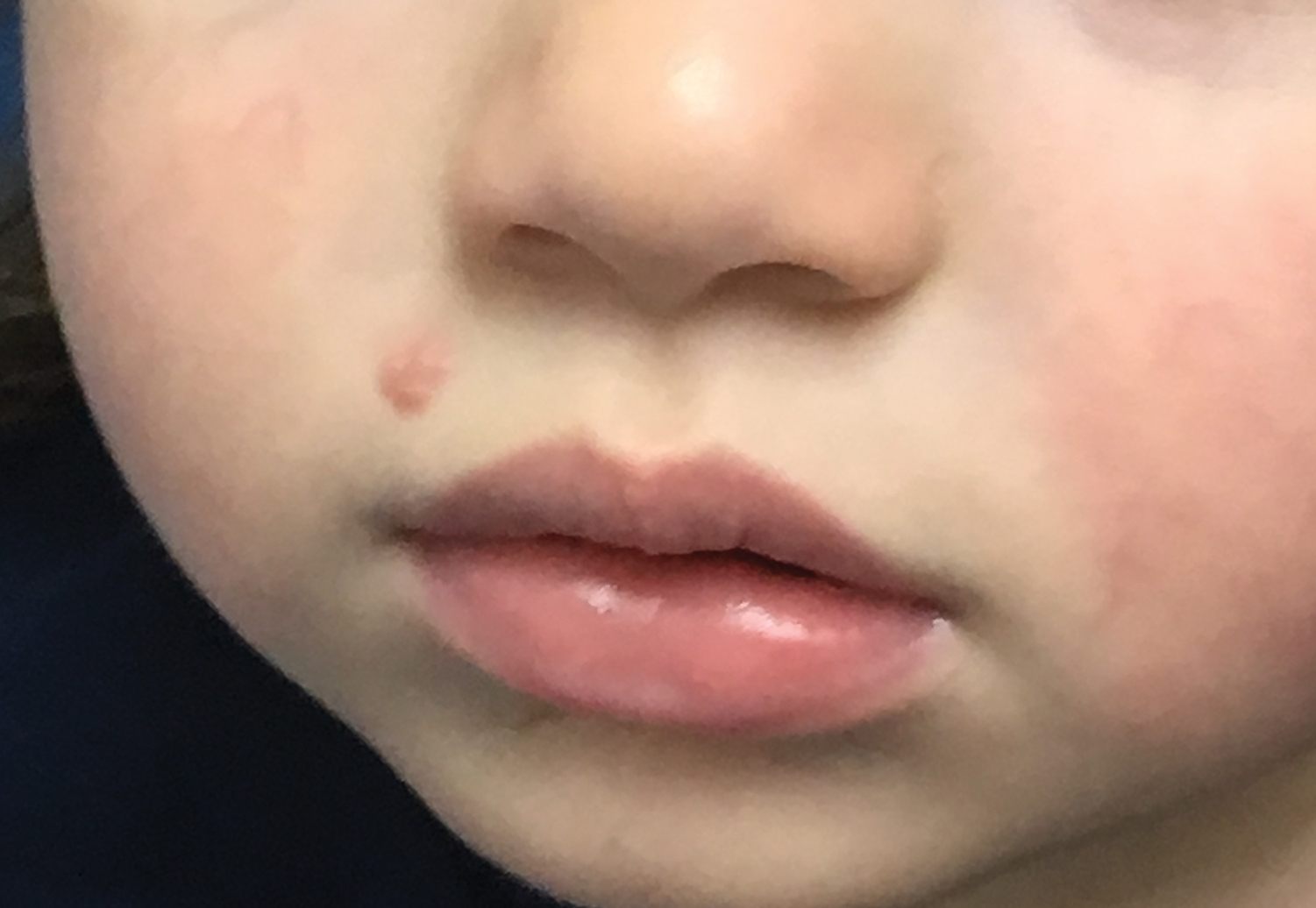

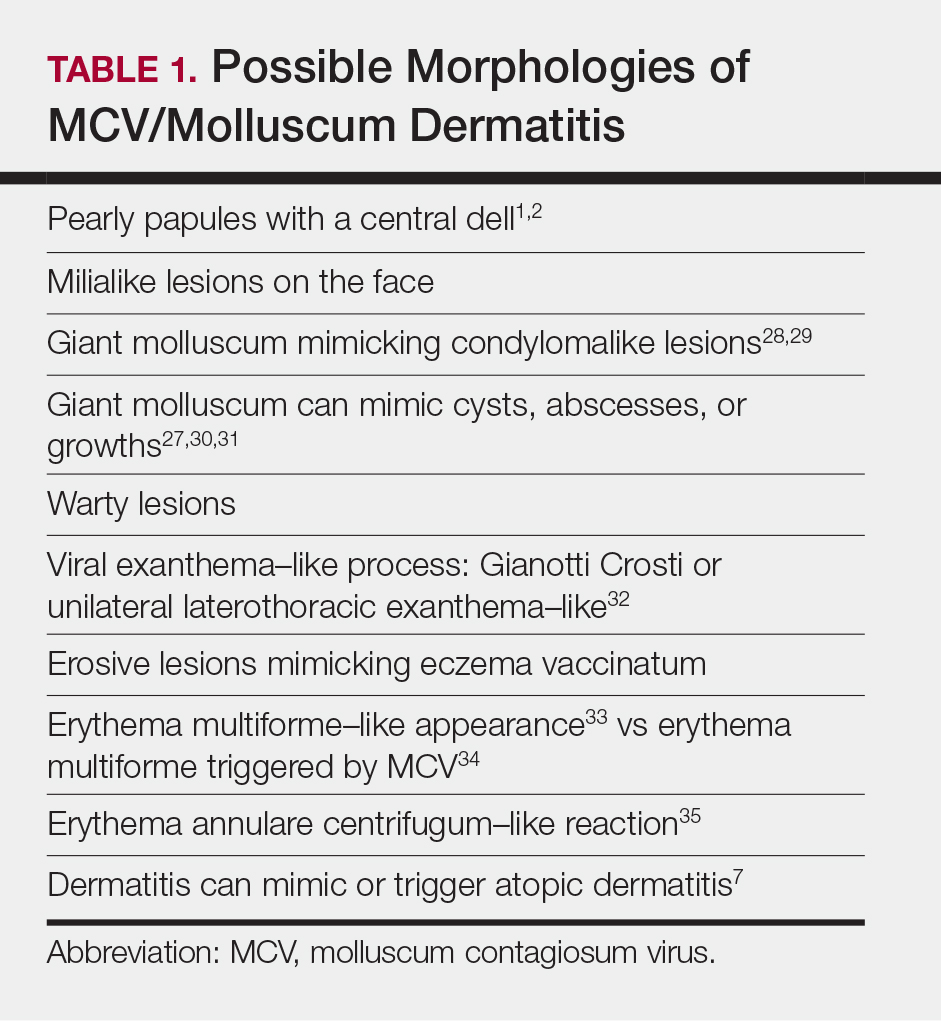

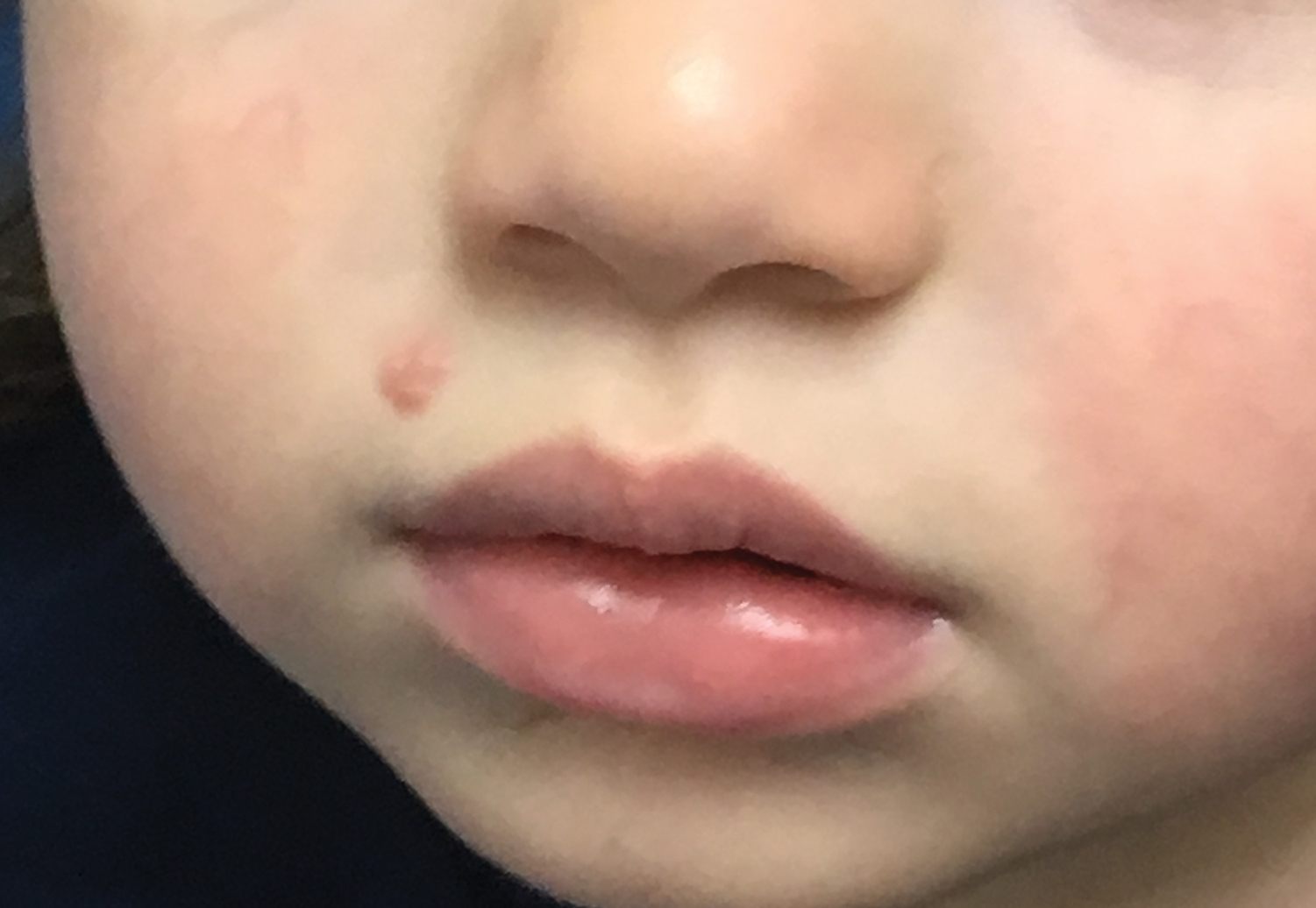

Molluscum lesions have a typical appearance of pearly papules with a central dell. These lesions are lighter to flesh colored and measure 1 to 3 mm.2,4,5 The lesions cluster in the axillae and extremities and average from 10 to 20 per child.6 Lesions clear spontaneously, but new ones will continue to form until immunity is developed. Specific clinical appearances of lesions that are not pearly papules are not infrequent. Table 1 contains a short list of the manifold clinical appearances of molluscum lesions in children.1,2,7,27-35 In particular, certain clinical appearances should be considered. In small children, head and neck lesions resembling milia are not uncommon. Giant or wartlike lesions can appear on the head, neck, or gluteal region in children and are clinical mimics of condyloma or other warts (Figure 1). Giant lesions also can grow in the subcutaneous space and mimic a cyst or abscess.27 Erosive lesions mimicking eczema vaccinatum can be seen (Figure 2), but dermoscopy may demonstrate central dells in some lesions. Other viral processes mimicked include Gianotti Crosti–like lesions (Figure 3) that appear when a papular id reaction forms over the extremities or a localized version in the axilla, mimicking unilateral laterothoracic exanthema.2,36,37 Hypersensitivity reactions are commonly noted with clearance and can be papular or demonstrate swelling and erythema, termed the beginning-of-the-end sign.38

Pruritus, erythema, and swelling can occur with clearance but do not appear in all patients. Addressing pruritus is important to prevent disease spread, as patients are likely to inoculate other areas of the skin with virus when they scratch, and lesion number is reduced with dermatitis interventions.36

Comorbidities

Molluscum lesions can occur in any child; however, the impaired immunologic status and skin barrier in patients with AD is ripe for the extensive spread of lesions that is associated with higher lesion count.36 Children with molluscum infection can experience new-onset dermatitis or triggering of AD flares, especially on the extremities, such as the antecubital and popliteal regions.7 A study of children with MCV infection demonstrated that treatment of active dermatitis reduced spread. The authors mentioned autoinoculation as the mechanism; however, these data also suggest supporting barrier state as a factor in disease spread.36 Superinfection can occur prior to6 or after therapy for lesions,37 but it is unclear if this relates to the underlying atopic diathesis. Children with molluscum have been described to have warts, psoriasis, family history of atopy, diabetes mellitus, and pityriasis alba,7 while immunosuppression of any kind is associated with molluscum and high lesion count or prolonged disease in childhood.1,2

Quality of Life

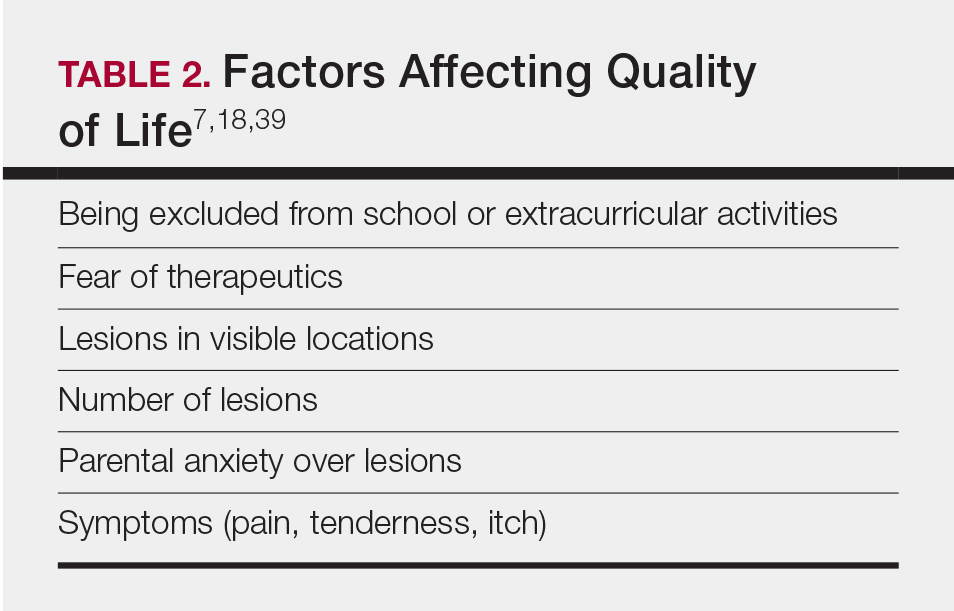

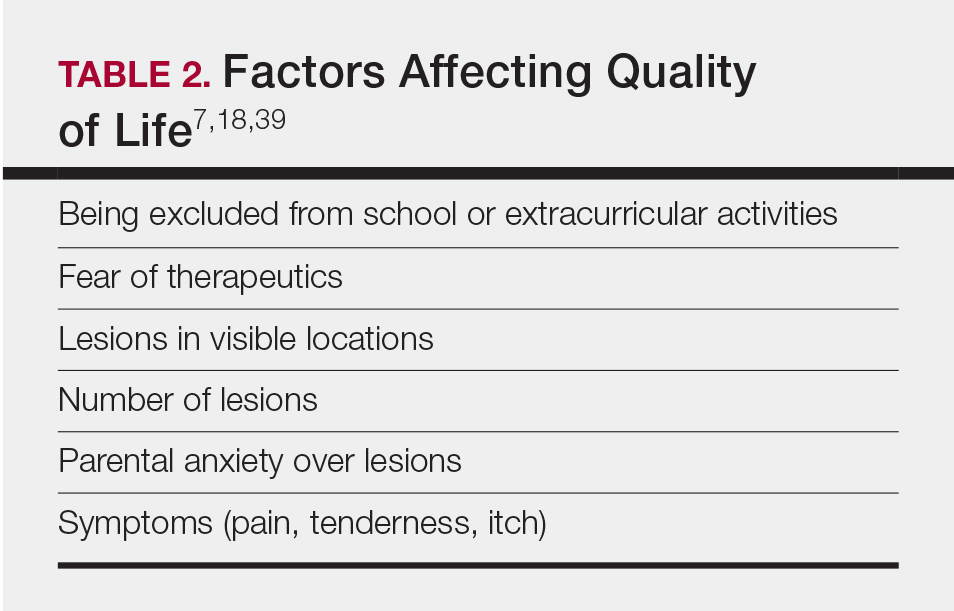

Children with molluscum who have higher lesion counts appear to be at risk for severe effects on their quality of life. Approximately 10% of children with MCV infection have been documented to have severe impairments on quality of life.39 In my practice, quality of life in children with MCV appears to be affected by many factors (Table 2).7,18,39

Treatments

Proper Skin Care and Treatment of AD

Therapy for AD and/or pruritus appears to limit lesion number in children with MCV and rashes or itch.7,36 I recommend barrier repair agents, including emollients and syndet bar cleansers, to prevent small breaks in the skin that occur with xerosis and AD and that increase itch and risk of spread. Therapy for AD and molluscum dermatitis is similar and overlapping. There is always a concern about the spread of MCV when using topical calcineurin inhibitors. I, therefore, focus the dermatitis therapeutics on topical corticosteroid–based care.6,40

Prevention of Spread

Prevention of spread begins with hygiene interventions. Cobathing is common in children with MCV and should be held off when possible. It is important for the child with MCV to avoid sharing bath towels and equipment23 and having bare skin come in contact with mats in sports. I request that children with MCV wear bathing suits that cover the areas affected.

Reassurance

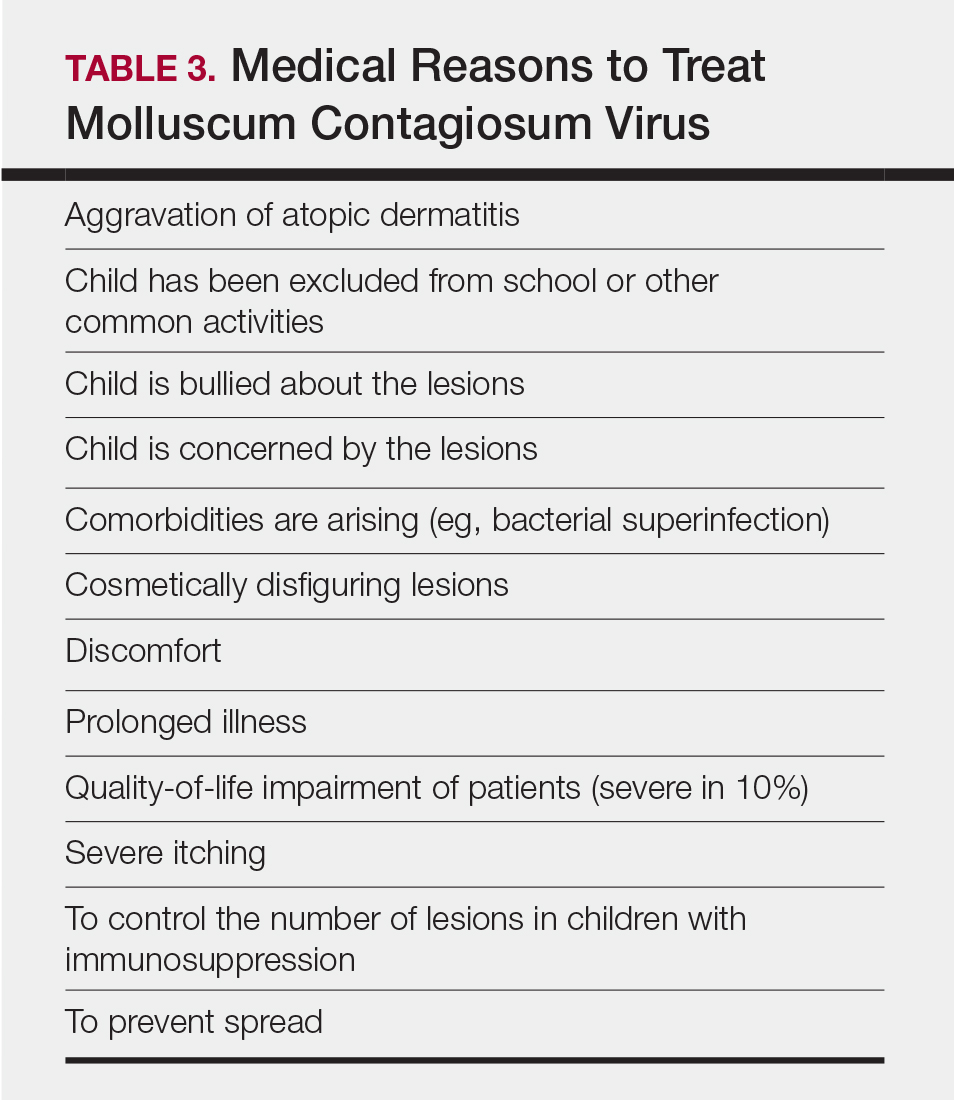

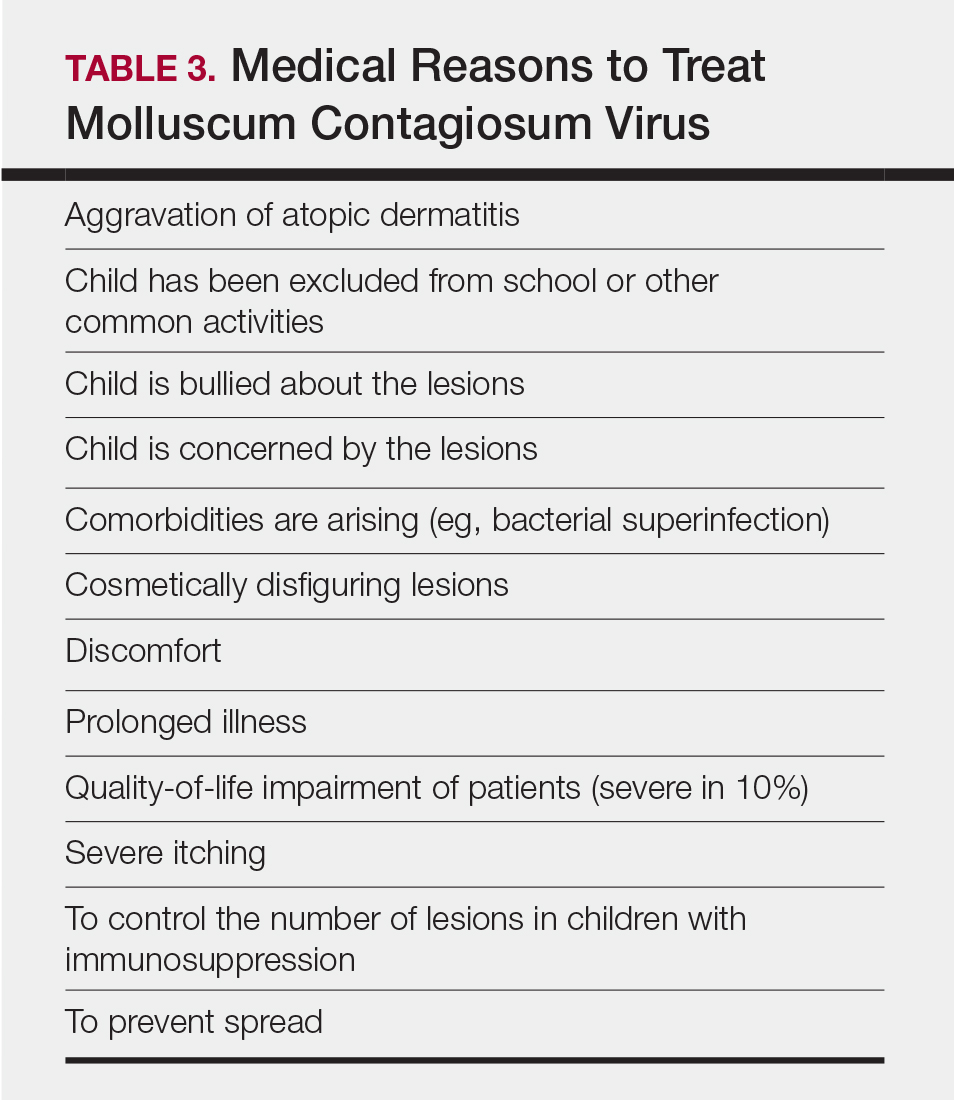

The most important therapy is reassurance.41 Many parents/guardians are truly unaware that the MCV infection can last for more than a year and therefore worry over normal disease course. When counseled as to the benign course of illness and given instructions on proper skin care, the parent/guardian of a child with MCV will often opt against therapy of uncomplicated cases. On the other hand, there are medical reasons for treatment, and they support the need for intervention (Table 3). Seventy percent of lesions resolve in 1.5 years; however, of the residual infections, some may last as long as 4 years.16 It is not recommended to stop children from attending school because of MCV.

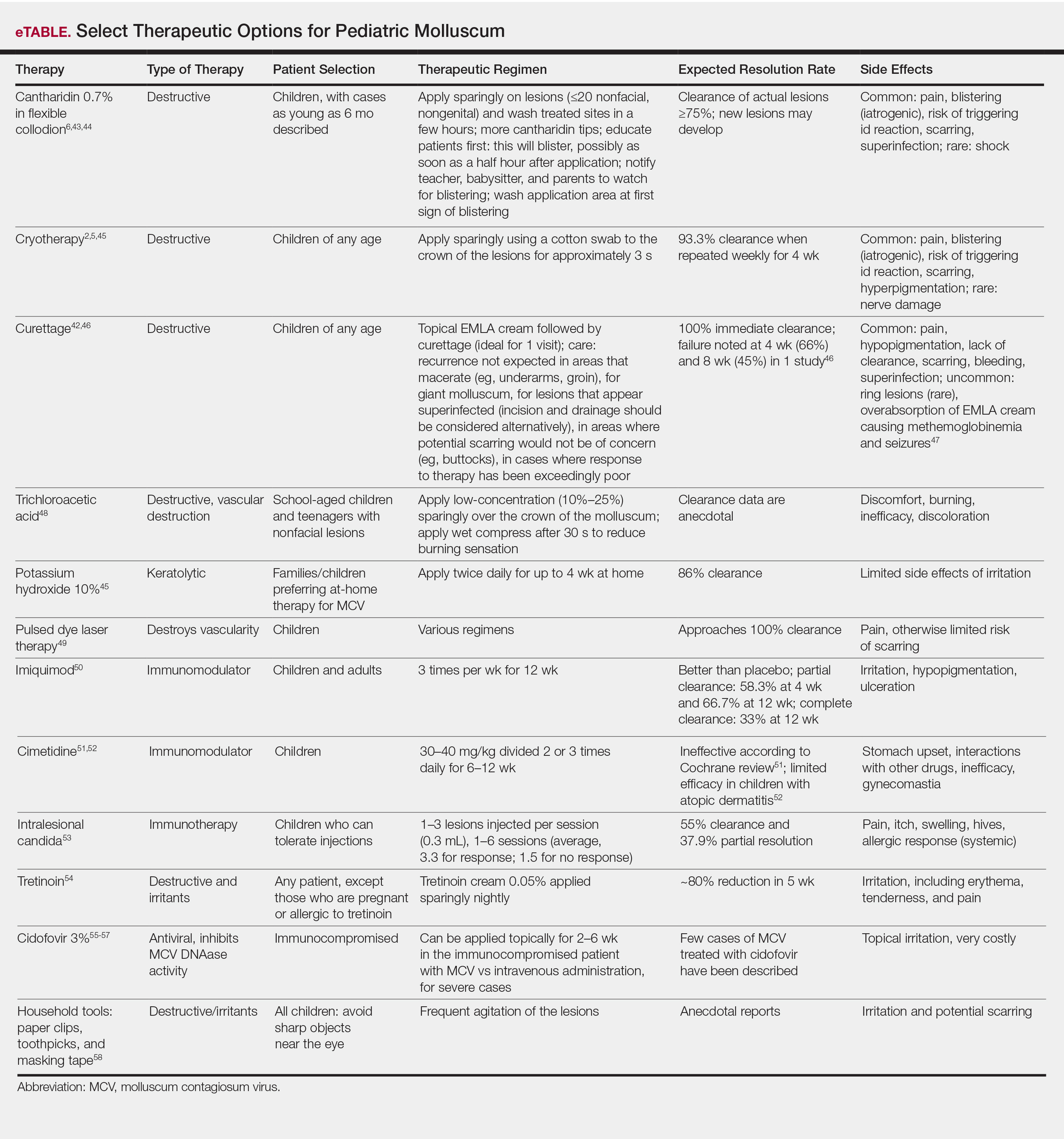

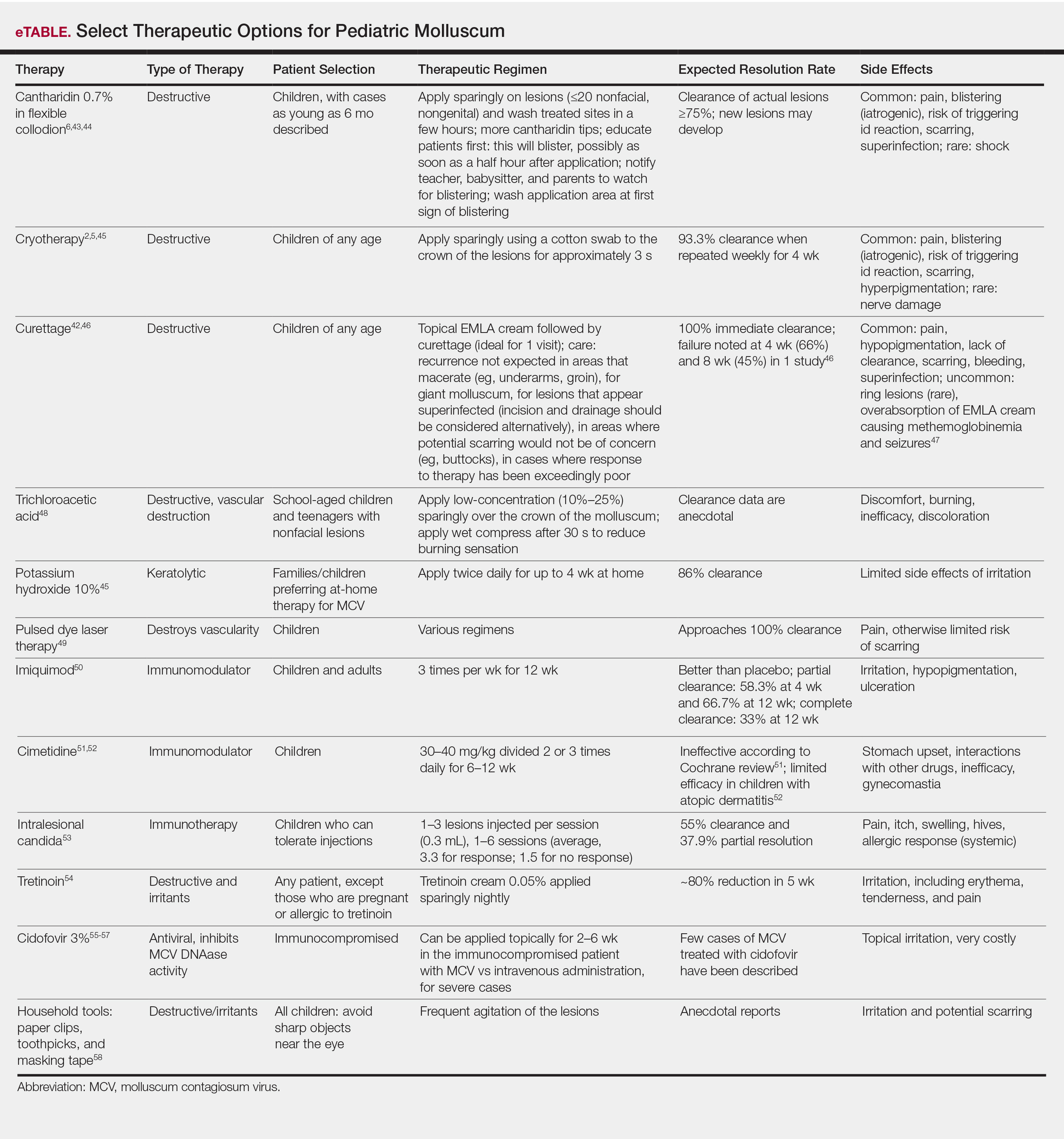

Interventional Therapy

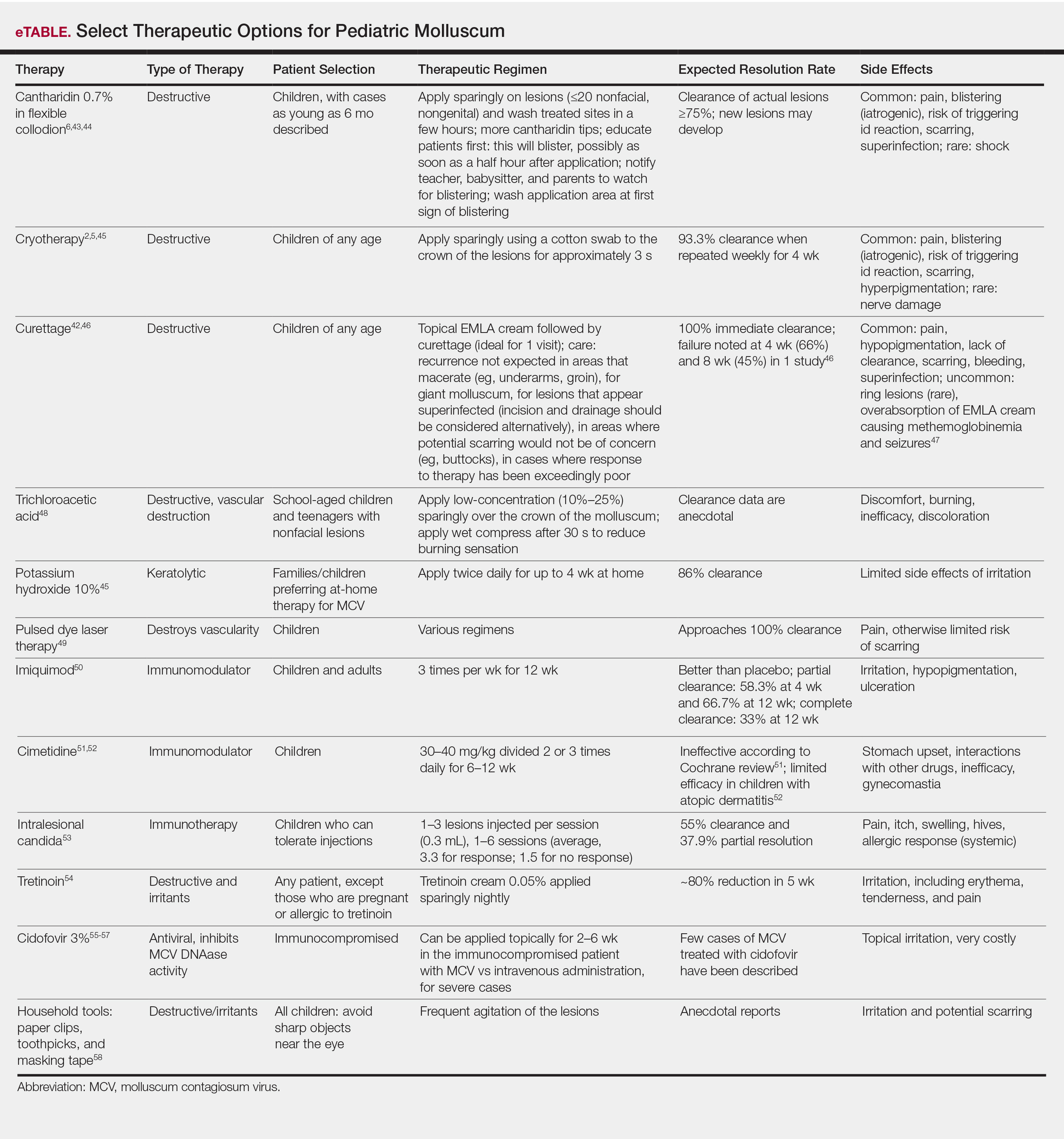

Therapeutics of MCV include destructive therapies in office (ie, cantharidin, cryotherapy, curettage, trichloroacetic acid, and glycolic acid) and at-home therapies (ie, topical retinoids, nitric oxide releasers)(eTable).2,5,6,42-58 When there are many lesions or spread is noted, immunotherapies can be used, including topical imiquimod, oral cimetidine, and intralesional Candida antigen.2,4,7 Pulsed dye laser cuts off the lesion vascular supply, while cidofovir is directly antiviral both topically and systemically, the latter reserved for severe cases in immunosuppressed adults.59 Head-to-head studies of cantharidin, curettage, topical peeling agents, and imiquimod demonstrated better satisfaction and fewer office visits with topical anesthetic and curettage on the first visit. Side effects were greatest for salicylic acid and glycolic acid; therefore, these agents are less desirable.42

Conclusion

Molluscum is a cutaneous viral infection that is common in children and has associated morbidities, including AD, pruritus, poor quality of life in some cases, and risk of contagion. Addressing the disease includes understanding its natural history and explaining it to parents/guardians. Therapeutics can be offered in cases where need is demonstrated, such as with lesions that spread and cause discomfort. Choice of therapeutics depends on the practitioner’s experience, the child’s clinical appearance, availability of therapy, and review of options with the parents/guardians. When avoidance of intervention is desired, barrier enhancement and treatment of symptomatic dermatitis are still beneficial, as are household (eg, not sharing towels) and activity (eg, adhesive bandages over active lesions) interventions to reduce transmission.

- Shisler JL. Immune evasion strategies of molluscum contagiosum virus. Adv Virus Res. 2015;92:201-252.

- Brown J, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, et al. Childhood molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:93-99.

- Moss B, Shisler JL, Xiang Y, et al. Immune-defense molecules of molluscum contagiosum virus, a human poxvirus. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:473-477.

- Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

- Choong KY, Roberts LJ. Molluscum contagiosum, swimming and bathing: a clinical analysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:89-92.

- Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:503-507.

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018;102:191-194.

- Ajithkumar VT, Sasidharanpillai S, Muhammed K, et al. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum following chemotherapy: a therapeutic challenge. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:516.

- Oren B, Wende SO. An outbreak of molluscum contagiosum in a kibbutz. Infection. 1991;19:159-161.

- Molluscum contagiosum. Healthy Children website. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/skin/Pages/Molluscum-Contagiosum.aspx. Updated November 21, 2015. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- Peterson AR, Nash E, Anderson BJ. Infectious disease in contact sports. Sports Health. 2019;11:47-58.

- Connell CO, Oranje A, Van Gysel D, et al. Congenital molluscum contagiosum: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:553-556.

- Luke JD, Silverberg NB. Vertically transmitted molluscum contagiosum infection. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E423-E425.

- Mendiratta V, Agarwal S, Chander R. Reappraisal of sexually transmitted infections in children: a hospital-based study from an urban area. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2014;35:25-28.

- Bargman H. Genital molluscum contagiosum in children: evidence of sexual abuse? CMAJ. 1986;135:432-433.

- Basdag H, Rainer BM, Cohen BA. Molluscum contagiosum: to treat or not to treat? experience with 170 children in an outpatient clinic setting in the northeastern United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:353-357.

- Koning S, Bruijnzeels MA, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in Dutch general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:417-419.

- Braue A, Ross G, Varigos G, et al. Epidemiology and impact of childhood molluscum contagiosum: a case series and critical review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:287-294.

- Sturt RJ, Muller HK, Francis GD. Molluscum contagiosum in villages of the West Sepik District of New Guinea. Med J Aust. 1971;2:751-754.

- Reynolds MG, Homan RC, Yorita Christensen KL, et al. The incidence of molluscum contagiosum among American Indians and Alaska Natives. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5255.

- Villa L, Varela JA, Otero L, et al. Molluscum contagiosum: a 20-year study in a sexually transmitted infections unit. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:423-424.

- Watanabe T, Morikawa S, Suzuki K, et al. Two major antigenic polypeptides of molluscum contagiosum virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:284-292.

- Vaccine basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccine-basics/index.html. Updated July 12, 2017. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- Mitchell JC. Observations on the virus of molluscum contagiosum. Br J Exp Pathol. 1953;34:44-49.

- Konya J, Thompson CH. Molluscum contagiosum virus: antibody responses in patients with clinical lesions and its sero-epidemiology in a representative Australian population. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:701-704.