User login

Trifluridine/tipiracil effective in metastatic gastric cancer after gastrectomy

Treatment with trifluridine/tipiracil was safe and showed efficacy in patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer regardless of their gastrectomy status, results of a preplanned analysis from the phase 3 randomized TAGS trial showed.

Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) was associated with significantly better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo in patients who had undergone gastrectomy, reported David H. Ilson, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues.

“The benefits of FTD/TPI were especially noteworthy in the subpopulation of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, who tended to be more heavily pretreated and were less tolerant of therapy. The overall safety profile of the drug, including the incidence of severe AEs [adverse events] was similar among patients who had or had not undergone gastrectomy. No new safety concerns were reported in patients who had undergone gastrectomy,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

FTD/TPI is an oral drug combining the thymidine analogue trifluridine and tipiracil, an inhibitor of trifluridine degradation. The drug was approved by the FDA in 2015 under the trade name Lonsurf for the treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer, and in 2019 for patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer (mGC/GEJC) that had been treated with at least two lines of chemotherapy.

In a phase 2 study conducted in Japan with 29 patients with metastatic gastric cancer that had progressed after chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine, platinum, taxanes, or irinotecan, FTD/TPI was associated with a median overall survival of 8.7 months and an investigator-assessed disease control rate of 65.5%,

As previously reported, in the randomized, controlled TAGS (TAS-102 Gastric Study), median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 5.7 months for patients assigned to receive trifluridine/tipiracil, compared with 3.6 months for patients randomized to placebo.

The current study is a preplanned subgroup analysis from the TAGS trial. Of 507 randomized patients, 221 had undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 147 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 74 to placebo. The remaining 286 patients had not undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 190 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 96 to placebo.

Among patients who had undergone gastrectomy, the hazard ratio for OS of patients treated with FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.79), and the HR for PFS was 0.48 (95% CI, 0.35-0.65).

In the no-gastrectomy subgroup, the overall survival HR for patients who received FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.80 (95% CI , 0.60-1.06), and the HR for PFS was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.49-0.85).

Grade 3 or greater adverse events with FTD/TPI occurred in 84.1% of gastrectomy patients and 76.3% of no-gastrectomy patients. Grade 3 or greater neutropenia occurred in 44.1% and 26.3%, respectively; grade 3 or greater anemia in 21.4% vs. 17.4%; and grade 3 or greater leukopenia was observed in 14.5% vs. 5.3%.

Dose modifications because of adverse events were required for 64.8% of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, and in 53.2% of those who had not.

Treatment discontinuations because of AEs occurred in 10.3% and 14.7%, respectively.

The study was funded by Taiho Oncology and Taiho Pharmaceutical Company. Dr. Islon reported grants and advisory role support from Taiho and others. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Ilson DH et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Oct 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3531.

Treatment with trifluridine/tipiracil was safe and showed efficacy in patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer regardless of their gastrectomy status, results of a preplanned analysis from the phase 3 randomized TAGS trial showed.

Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) was associated with significantly better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo in patients who had undergone gastrectomy, reported David H. Ilson, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues.

“The benefits of FTD/TPI were especially noteworthy in the subpopulation of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, who tended to be more heavily pretreated and were less tolerant of therapy. The overall safety profile of the drug, including the incidence of severe AEs [adverse events] was similar among patients who had or had not undergone gastrectomy. No new safety concerns were reported in patients who had undergone gastrectomy,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

FTD/TPI is an oral drug combining the thymidine analogue trifluridine and tipiracil, an inhibitor of trifluridine degradation. The drug was approved by the FDA in 2015 under the trade name Lonsurf for the treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer, and in 2019 for patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer (mGC/GEJC) that had been treated with at least two lines of chemotherapy.

In a phase 2 study conducted in Japan with 29 patients with metastatic gastric cancer that had progressed after chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine, platinum, taxanes, or irinotecan, FTD/TPI was associated with a median overall survival of 8.7 months and an investigator-assessed disease control rate of 65.5%,

As previously reported, in the randomized, controlled TAGS (TAS-102 Gastric Study), median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 5.7 months for patients assigned to receive trifluridine/tipiracil, compared with 3.6 months for patients randomized to placebo.

The current study is a preplanned subgroup analysis from the TAGS trial. Of 507 randomized patients, 221 had undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 147 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 74 to placebo. The remaining 286 patients had not undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 190 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 96 to placebo.

Among patients who had undergone gastrectomy, the hazard ratio for OS of patients treated with FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.79), and the HR for PFS was 0.48 (95% CI, 0.35-0.65).

In the no-gastrectomy subgroup, the overall survival HR for patients who received FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.80 (95% CI , 0.60-1.06), and the HR for PFS was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.49-0.85).

Grade 3 or greater adverse events with FTD/TPI occurred in 84.1% of gastrectomy patients and 76.3% of no-gastrectomy patients. Grade 3 or greater neutropenia occurred in 44.1% and 26.3%, respectively; grade 3 or greater anemia in 21.4% vs. 17.4%; and grade 3 or greater leukopenia was observed in 14.5% vs. 5.3%.

Dose modifications because of adverse events were required for 64.8% of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, and in 53.2% of those who had not.

Treatment discontinuations because of AEs occurred in 10.3% and 14.7%, respectively.

The study was funded by Taiho Oncology and Taiho Pharmaceutical Company. Dr. Islon reported grants and advisory role support from Taiho and others. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Ilson DH et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Oct 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3531.

Treatment with trifluridine/tipiracil was safe and showed efficacy in patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer regardless of their gastrectomy status, results of a preplanned analysis from the phase 3 randomized TAGS trial showed.

Trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) was associated with significantly better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) than placebo in patients who had undergone gastrectomy, reported David H. Ilson, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and colleagues.

“The benefits of FTD/TPI were especially noteworthy in the subpopulation of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, who tended to be more heavily pretreated and were less tolerant of therapy. The overall safety profile of the drug, including the incidence of severe AEs [adverse events] was similar among patients who had or had not undergone gastrectomy. No new safety concerns were reported in patients who had undergone gastrectomy,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

FTD/TPI is an oral drug combining the thymidine analogue trifluridine and tipiracil, an inhibitor of trifluridine degradation. The drug was approved by the FDA in 2015 under the trade name Lonsurf for the treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer, and in 2019 for patients with metastatic gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer (mGC/GEJC) that had been treated with at least two lines of chemotherapy.

In a phase 2 study conducted in Japan with 29 patients with metastatic gastric cancer that had progressed after chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine, platinum, taxanes, or irinotecan, FTD/TPI was associated with a median overall survival of 8.7 months and an investigator-assessed disease control rate of 65.5%,

As previously reported, in the randomized, controlled TAGS (TAS-102 Gastric Study), median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 5.7 months for patients assigned to receive trifluridine/tipiracil, compared with 3.6 months for patients randomized to placebo.

The current study is a preplanned subgroup analysis from the TAGS trial. Of 507 randomized patients, 221 had undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 147 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 74 to placebo. The remaining 286 patients had not undergone gastrectomy, and of this group 190 were randomized to FTD/TPI and 96 to placebo.

Among patients who had undergone gastrectomy, the hazard ratio for OS of patients treated with FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.79), and the HR for PFS was 0.48 (95% CI, 0.35-0.65).

In the no-gastrectomy subgroup, the overall survival HR for patients who received FTD/TPI vs. placebo was 0.80 (95% CI , 0.60-1.06), and the HR for PFS was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.49-0.85).

Grade 3 or greater adverse events with FTD/TPI occurred in 84.1% of gastrectomy patients and 76.3% of no-gastrectomy patients. Grade 3 or greater neutropenia occurred in 44.1% and 26.3%, respectively; grade 3 or greater anemia in 21.4% vs. 17.4%; and grade 3 or greater leukopenia was observed in 14.5% vs. 5.3%.

Dose modifications because of adverse events were required for 64.8% of patients who had undergone gastrectomy, and in 53.2% of those who had not.

Treatment discontinuations because of AEs occurred in 10.3% and 14.7%, respectively.

The study was funded by Taiho Oncology and Taiho Pharmaceutical Company. Dr. Islon reported grants and advisory role support from Taiho and others. Multiple coauthors had similar disclosures.

SOURCE: Ilson DH et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Oct 10. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3531.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Opioid-free regimen after neck dissection keeps patients comfortable

CHICAGO – Many patients with thyroid cancer can be sent home after lateral neck dissections with few or no opioids, in the experience of an institution that made a sea change in opioid prescribing practices.

Between 2012 to mid-2019, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, saw 243 patients who received lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer and were opioid naive. Before a shift in prescribing practices in early 2017, 5.3% of patients were discharged without opioids after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, whereas after the shift, 41.7% of patients went home on an opioid-free regimen, James Y. Lim, MD, an endocrine surgeon and assistant professor at the university, said during a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

The initiative, led by Maisie L. Shindo, MD, was started at the OHSU Thyroid and Parathyroid Center in late 2016 in an effort to reduce the number of opioid prescriptions in postoperative patients, Dr. Lim explained in an interview after his presentation. Dr. Shindo, coauthor of the study, directs the thyroid and parathyroid surgery department at the university.

“Before the initiative, standard postoperative pain control consisted of opioids. However, it was common for patients to mention that they did not need them at all,” said Dr. Lim. “Our prescribing practices today reflect the ability to maintain patient comfort without having to resort to opioids. We are able to keep more than 90% of our patients comfortable with a multimodal approach to pain,” he said.

Dr. Lim and colleagues used a retrospective record review to tally how many opioids were initially prescribed at discharge after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, along with the number and quantity of refills for opioids after discharge. Opioid doses were converted to morphine milligram equivalents (MME), and dosing patterns were compared for the periods before and after Feb. 1, 2017, when operating surgeons changed opioid prescribing patterns. These two subgroups were termed group 1 and group 2, respectively.

In all, 143 of the total 243 patients included in the study were women, and the mean age at the time of surgery was 47 years. Patients in group 1 had 170 surgeries, and those in group 2 had 103 surgeries.

Group 1 patients received a mean 295.4 MME after surgery, and group 2 patients received a mean 85.89 MME, though there was wide variation in discharge prescribing within each group. The absolute difference between the pre- and postinitiative groups was 209.51 MME (95% confidence interval, 157.8-261.2), for an effect size of 1.08. The MME figures for each group reflected both discharge medication and any refills or rescue prescriptions that were required.

“Decreasing the volume of opioids prescribed at discharge will decrease waste and reduce potential for addiction,” the authors noted.

As far as is known, “this is the first study that seeks to identify the extent of opioid needs after an extensive neck dissection for thyroid cancer operation,” said Dr. Lim, who added that he has been surprised at how well patients do after surgery. He said he and other surgeons had expected patients to have more pain from lateral neck dissections than they seem to experience.

“There have been studies, including from our own institution, that reported the relatively small need for opioids after a central neck procedure, such as a total thyroidectomy,” Dr. Lim said. “Our study showed that those requirements remain low even with more extensive lateral neck dissections. In the last 8 months of the study, more than 70% of patients with lateral neck dissections did not require opioids on discharge.”

Dr. Lim said that he and the rest of the care team advise patients to ramp up nonpharmacologic options, including ibuprofen, acetaminophen, ice packs, and throat lozenges – all of which can make a big difference in postoperative comfort.

Paying attention to how patients fare during an inpatient stay or even same-day procedures can help physicians estimate postdischarge needs, said Dr. Lim: “For our lateral neck dissections, patients usually stay overnight, and we can get a pretty good estimate of how their pain is being managed off opioids. For same-day procedures, it requires evaluating the patient before discharge and reassessing the pain needs at that time.”

Helping patients and their families understand the postoperative course and what level of discomfort they can expect has helped in the effort to minimize opioid use, Dr. Lim said. Overall, patients, family, and staff have received the changes “very well,” he added.

Practices that are considering a move toward opioid-free or opioid-sparing regimens after surgery should know that “it does require buy-in from all members of the medical team as well as the patients,” Dr. Lim emphasized.

“It starts at the initial surgical consultation, with surgeons educating patients on what to expect in terms of postoperative discomfort and pain. Patients are informed that they will have some discomfort and mild pain that is generally controlled with nonopioid, over-the-counter medications and cold therapy to the surgical site,” he explained.

“It requires education of the nurses and residents to encourage moving away from using opioids as a first-line therapy,” but it’s worth the hard work to get to a point where patients are going home with few, or no, opioids, said Dr. Lim. “Ultimately, patients are happier and are often relieved that their pain can be controlled without opioids,” he said.

Dr. Shindo is the senior author of a related study examining opioid reduction in neck dissection for a variety of head and neck cancers. In that study, she and her coauthors found that opioid requirements vary by cancer type. In an upcoming manuscript, the researchers are aiming to characterize typical opioid requirements for commonly performed procedures, to provide surgeons with evidence-based baselines for appropriate, but not excessive, opioid prescribing.

Dr. Lim reported no outside sources of funding. He, Dr. Shindo, and a third author reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lim J et al. ATA 2019, Poster 401.

CHICAGO – Many patients with thyroid cancer can be sent home after lateral neck dissections with few or no opioids, in the experience of an institution that made a sea change in opioid prescribing practices.

Between 2012 to mid-2019, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, saw 243 patients who received lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer and were opioid naive. Before a shift in prescribing practices in early 2017, 5.3% of patients were discharged without opioids after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, whereas after the shift, 41.7% of patients went home on an opioid-free regimen, James Y. Lim, MD, an endocrine surgeon and assistant professor at the university, said during a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

The initiative, led by Maisie L. Shindo, MD, was started at the OHSU Thyroid and Parathyroid Center in late 2016 in an effort to reduce the number of opioid prescriptions in postoperative patients, Dr. Lim explained in an interview after his presentation. Dr. Shindo, coauthor of the study, directs the thyroid and parathyroid surgery department at the university.

“Before the initiative, standard postoperative pain control consisted of opioids. However, it was common for patients to mention that they did not need them at all,” said Dr. Lim. “Our prescribing practices today reflect the ability to maintain patient comfort without having to resort to opioids. We are able to keep more than 90% of our patients comfortable with a multimodal approach to pain,” he said.

Dr. Lim and colleagues used a retrospective record review to tally how many opioids were initially prescribed at discharge after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, along with the number and quantity of refills for opioids after discharge. Opioid doses were converted to morphine milligram equivalents (MME), and dosing patterns were compared for the periods before and after Feb. 1, 2017, when operating surgeons changed opioid prescribing patterns. These two subgroups were termed group 1 and group 2, respectively.

In all, 143 of the total 243 patients included in the study were women, and the mean age at the time of surgery was 47 years. Patients in group 1 had 170 surgeries, and those in group 2 had 103 surgeries.

Group 1 patients received a mean 295.4 MME after surgery, and group 2 patients received a mean 85.89 MME, though there was wide variation in discharge prescribing within each group. The absolute difference between the pre- and postinitiative groups was 209.51 MME (95% confidence interval, 157.8-261.2), for an effect size of 1.08. The MME figures for each group reflected both discharge medication and any refills or rescue prescriptions that were required.

“Decreasing the volume of opioids prescribed at discharge will decrease waste and reduce potential for addiction,” the authors noted.

As far as is known, “this is the first study that seeks to identify the extent of opioid needs after an extensive neck dissection for thyroid cancer operation,” said Dr. Lim, who added that he has been surprised at how well patients do after surgery. He said he and other surgeons had expected patients to have more pain from lateral neck dissections than they seem to experience.

“There have been studies, including from our own institution, that reported the relatively small need for opioids after a central neck procedure, such as a total thyroidectomy,” Dr. Lim said. “Our study showed that those requirements remain low even with more extensive lateral neck dissections. In the last 8 months of the study, more than 70% of patients with lateral neck dissections did not require opioids on discharge.”

Dr. Lim said that he and the rest of the care team advise patients to ramp up nonpharmacologic options, including ibuprofen, acetaminophen, ice packs, and throat lozenges – all of which can make a big difference in postoperative comfort.

Paying attention to how patients fare during an inpatient stay or even same-day procedures can help physicians estimate postdischarge needs, said Dr. Lim: “For our lateral neck dissections, patients usually stay overnight, and we can get a pretty good estimate of how their pain is being managed off opioids. For same-day procedures, it requires evaluating the patient before discharge and reassessing the pain needs at that time.”

Helping patients and their families understand the postoperative course and what level of discomfort they can expect has helped in the effort to minimize opioid use, Dr. Lim said. Overall, patients, family, and staff have received the changes “very well,” he added.

Practices that are considering a move toward opioid-free or opioid-sparing regimens after surgery should know that “it does require buy-in from all members of the medical team as well as the patients,” Dr. Lim emphasized.

“It starts at the initial surgical consultation, with surgeons educating patients on what to expect in terms of postoperative discomfort and pain. Patients are informed that they will have some discomfort and mild pain that is generally controlled with nonopioid, over-the-counter medications and cold therapy to the surgical site,” he explained.

“It requires education of the nurses and residents to encourage moving away from using opioids as a first-line therapy,” but it’s worth the hard work to get to a point where patients are going home with few, or no, opioids, said Dr. Lim. “Ultimately, patients are happier and are often relieved that their pain can be controlled without opioids,” he said.

Dr. Shindo is the senior author of a related study examining opioid reduction in neck dissection for a variety of head and neck cancers. In that study, she and her coauthors found that opioid requirements vary by cancer type. In an upcoming manuscript, the researchers are aiming to characterize typical opioid requirements for commonly performed procedures, to provide surgeons with evidence-based baselines for appropriate, but not excessive, opioid prescribing.

Dr. Lim reported no outside sources of funding. He, Dr. Shindo, and a third author reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lim J et al. ATA 2019, Poster 401.

CHICAGO – Many patients with thyroid cancer can be sent home after lateral neck dissections with few or no opioids, in the experience of an institution that made a sea change in opioid prescribing practices.

Between 2012 to mid-2019, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), Portland, saw 243 patients who received lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer and were opioid naive. Before a shift in prescribing practices in early 2017, 5.3% of patients were discharged without opioids after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, whereas after the shift, 41.7% of patients went home on an opioid-free regimen, James Y. Lim, MD, an endocrine surgeon and assistant professor at the university, said during a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association.

The initiative, led by Maisie L. Shindo, MD, was started at the OHSU Thyroid and Parathyroid Center in late 2016 in an effort to reduce the number of opioid prescriptions in postoperative patients, Dr. Lim explained in an interview after his presentation. Dr. Shindo, coauthor of the study, directs the thyroid and parathyroid surgery department at the university.

“Before the initiative, standard postoperative pain control consisted of opioids. However, it was common for patients to mention that they did not need them at all,” said Dr. Lim. “Our prescribing practices today reflect the ability to maintain patient comfort without having to resort to opioids. We are able to keep more than 90% of our patients comfortable with a multimodal approach to pain,” he said.

Dr. Lim and colleagues used a retrospective record review to tally how many opioids were initially prescribed at discharge after lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer, along with the number and quantity of refills for opioids after discharge. Opioid doses were converted to morphine milligram equivalents (MME), and dosing patterns were compared for the periods before and after Feb. 1, 2017, when operating surgeons changed opioid prescribing patterns. These two subgroups were termed group 1 and group 2, respectively.

In all, 143 of the total 243 patients included in the study were women, and the mean age at the time of surgery was 47 years. Patients in group 1 had 170 surgeries, and those in group 2 had 103 surgeries.

Group 1 patients received a mean 295.4 MME after surgery, and group 2 patients received a mean 85.89 MME, though there was wide variation in discharge prescribing within each group. The absolute difference between the pre- and postinitiative groups was 209.51 MME (95% confidence interval, 157.8-261.2), for an effect size of 1.08. The MME figures for each group reflected both discharge medication and any refills or rescue prescriptions that were required.

“Decreasing the volume of opioids prescribed at discharge will decrease waste and reduce potential for addiction,” the authors noted.

As far as is known, “this is the first study that seeks to identify the extent of opioid needs after an extensive neck dissection for thyroid cancer operation,” said Dr. Lim, who added that he has been surprised at how well patients do after surgery. He said he and other surgeons had expected patients to have more pain from lateral neck dissections than they seem to experience.

“There have been studies, including from our own institution, that reported the relatively small need for opioids after a central neck procedure, such as a total thyroidectomy,” Dr. Lim said. “Our study showed that those requirements remain low even with more extensive lateral neck dissections. In the last 8 months of the study, more than 70% of patients with lateral neck dissections did not require opioids on discharge.”

Dr. Lim said that he and the rest of the care team advise patients to ramp up nonpharmacologic options, including ibuprofen, acetaminophen, ice packs, and throat lozenges – all of which can make a big difference in postoperative comfort.

Paying attention to how patients fare during an inpatient stay or even same-day procedures can help physicians estimate postdischarge needs, said Dr. Lim: “For our lateral neck dissections, patients usually stay overnight, and we can get a pretty good estimate of how their pain is being managed off opioids. For same-day procedures, it requires evaluating the patient before discharge and reassessing the pain needs at that time.”

Helping patients and their families understand the postoperative course and what level of discomfort they can expect has helped in the effort to minimize opioid use, Dr. Lim said. Overall, patients, family, and staff have received the changes “very well,” he added.

Practices that are considering a move toward opioid-free or opioid-sparing regimens after surgery should know that “it does require buy-in from all members of the medical team as well as the patients,” Dr. Lim emphasized.

“It starts at the initial surgical consultation, with surgeons educating patients on what to expect in terms of postoperative discomfort and pain. Patients are informed that they will have some discomfort and mild pain that is generally controlled with nonopioid, over-the-counter medications and cold therapy to the surgical site,” he explained.

“It requires education of the nurses and residents to encourage moving away from using opioids as a first-line therapy,” but it’s worth the hard work to get to a point where patients are going home with few, or no, opioids, said Dr. Lim. “Ultimately, patients are happier and are often relieved that their pain can be controlled without opioids,” he said.

Dr. Shindo is the senior author of a related study examining opioid reduction in neck dissection for a variety of head and neck cancers. In that study, she and her coauthors found that opioid requirements vary by cancer type. In an upcoming manuscript, the researchers are aiming to characterize typical opioid requirements for commonly performed procedures, to provide surgeons with evidence-based baselines for appropriate, but not excessive, opioid prescribing.

Dr. Lim reported no outside sources of funding. He, Dr. Shindo, and a third author reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lim J et al. ATA 2019, Poster 401.

REPORTING FROM ATA 2019

Should frequency of prenatal visits be reduced for low-risk women?

In their article, “Feasibility—and safety—of reducing the traditional 14 prenatal visits to 8 or 10” (July 2019), Erin Clark, MD, Yvonne Butler-Tobah, MD, and Lauren D. Demosthenes, MD, argued as to why a “one-size-fits all” approach to prenatal care should be redesigned for low-risk expectant mothers. They highlighted 3 institutions that developed a reduced-visit prenatal care model incorporating remote monitoring and mobile health app technology. Women who used the reduced visit option were overall satisfied with the technology employed and with their health care experience.

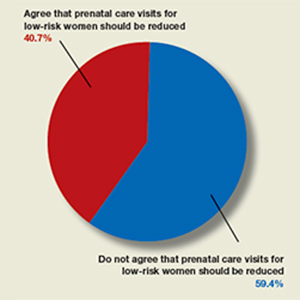

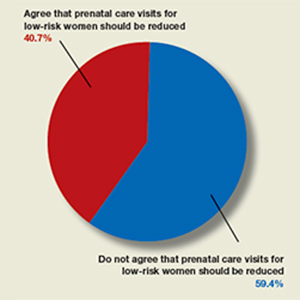

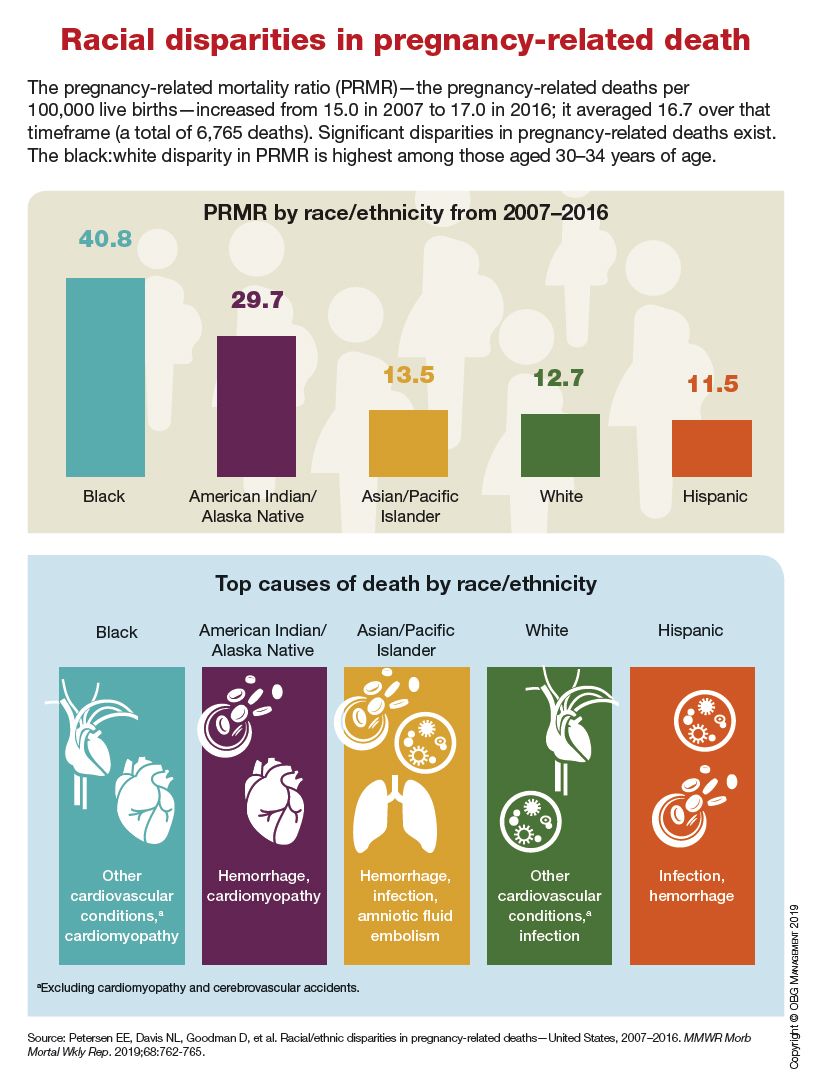

OBG Management polled readers with this question: “Do you agree that the number of prenatal care visits for low-risk women should be reduced?”

A total of 123 readers cast their vote:

- 40.7% (50 readers) said yes

- 59.4% (73 readers) said no

In their article, “Feasibility—and safety—of reducing the traditional 14 prenatal visits to 8 or 10” (July 2019), Erin Clark, MD, Yvonne Butler-Tobah, MD, and Lauren D. Demosthenes, MD, argued as to why a “one-size-fits all” approach to prenatal care should be redesigned for low-risk expectant mothers. They highlighted 3 institutions that developed a reduced-visit prenatal care model incorporating remote monitoring and mobile health app technology. Women who used the reduced visit option were overall satisfied with the technology employed and with their health care experience.

OBG Management polled readers with this question: “Do you agree that the number of prenatal care visits for low-risk women should be reduced?”

A total of 123 readers cast their vote:

- 40.7% (50 readers) said yes

- 59.4% (73 readers) said no

In their article, “Feasibility—and safety—of reducing the traditional 14 prenatal visits to 8 or 10” (July 2019), Erin Clark, MD, Yvonne Butler-Tobah, MD, and Lauren D. Demosthenes, MD, argued as to why a “one-size-fits all” approach to prenatal care should be redesigned for low-risk expectant mothers. They highlighted 3 institutions that developed a reduced-visit prenatal care model incorporating remote monitoring and mobile health app technology. Women who used the reduced visit option were overall satisfied with the technology employed and with their health care experience.

OBG Management polled readers with this question: “Do you agree that the number of prenatal care visits for low-risk women should be reduced?”

A total of 123 readers cast their vote:

- 40.7% (50 readers) said yes

- 59.4% (73 readers) said no

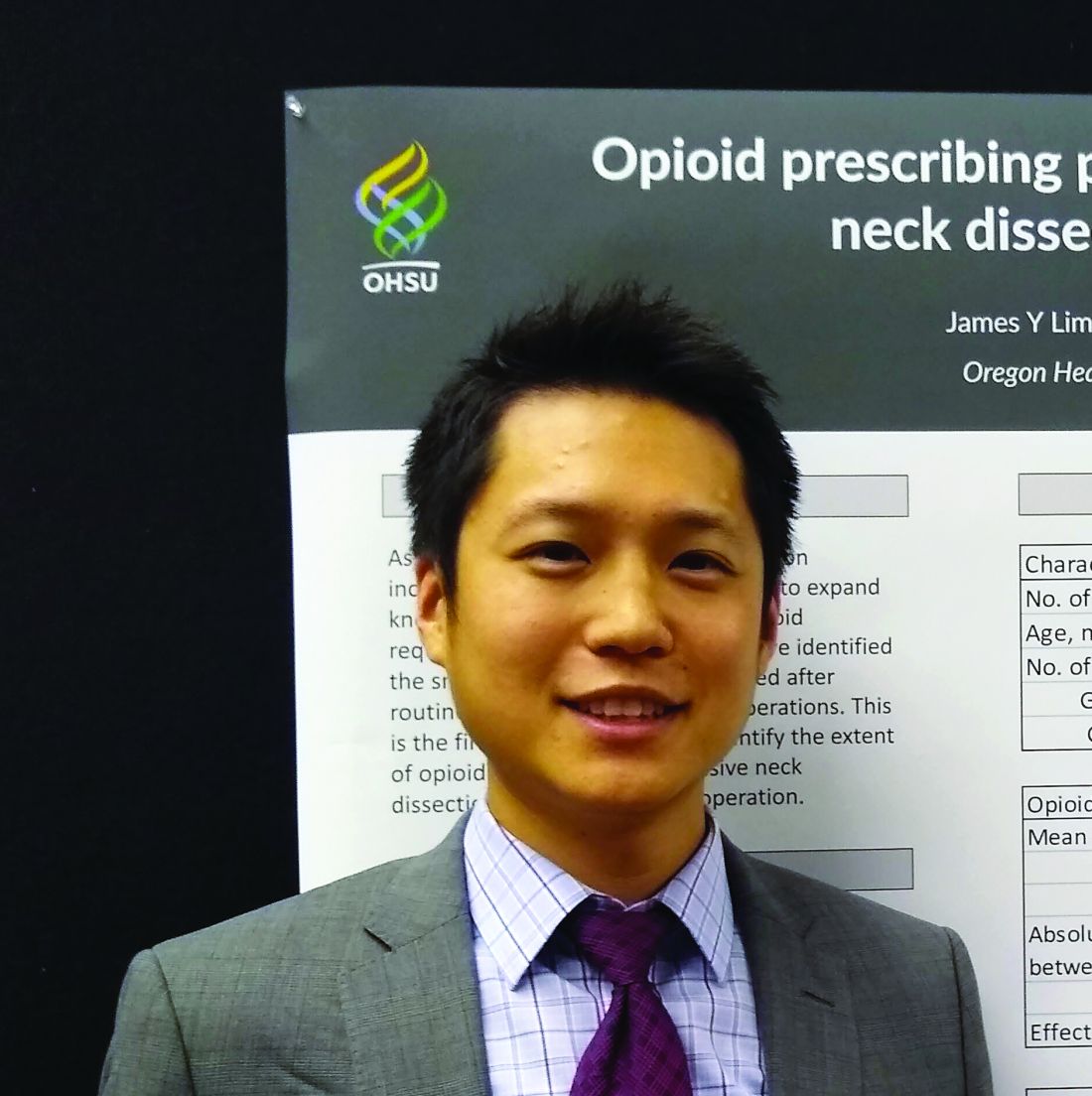

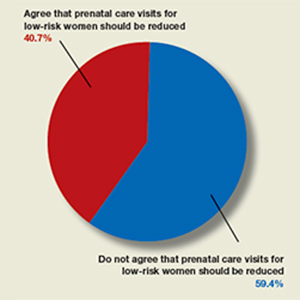

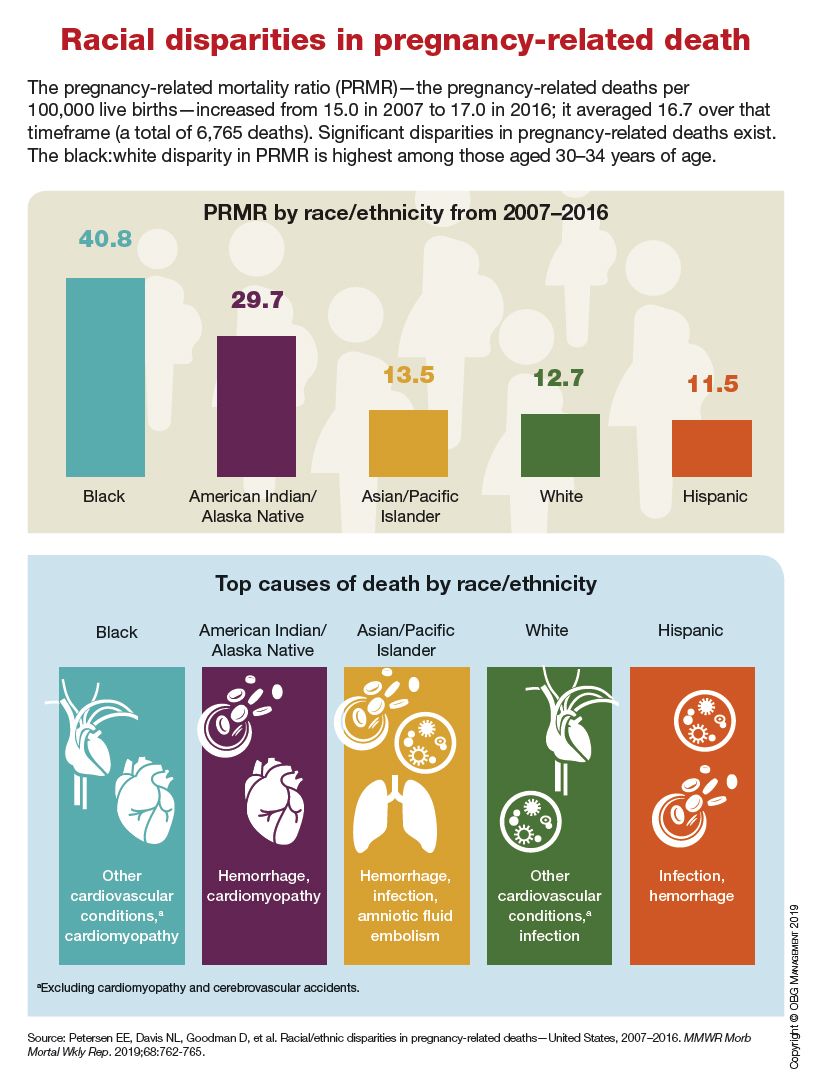

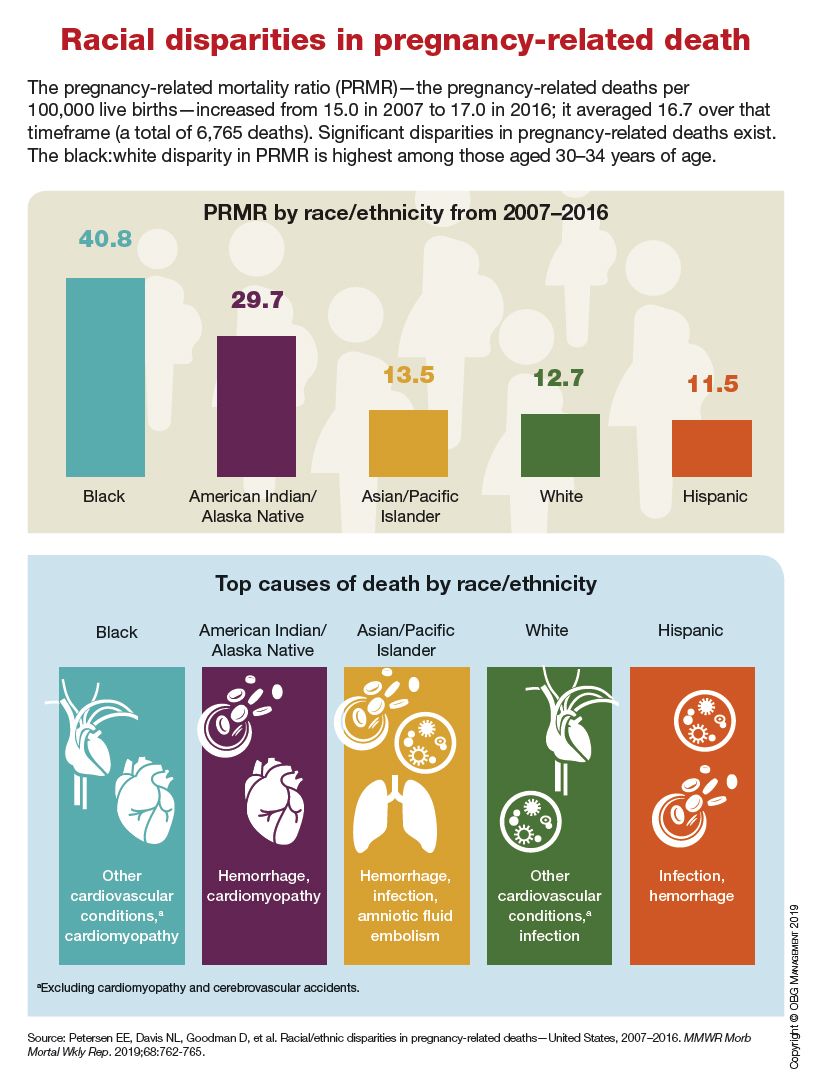

Racial disparities in pregnancy-related death

Product Update: Addyi alcohol ban lifted, fezolinetant trial, outcomes tracker, comfort gown

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

FDA REMOVES ALCOHOL BAN WITH ADDYI

Sprout Pharmaceuticals announced that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed their contraindication on alcohol use with Addyi® (flibanserin). Addyi was approved in 2015 and is an oral nonhormonal pill for acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women. Patients are advised to discontinue drinking alcohol at least 2 hours before taking Addyi at bedtime or skip the Addyi dose that evening.

The FDA also removed the requirement, under its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, for health care practitioners or pharmacies to be certified to prescribe or dispense Addyi. Sprout says that to make all labeling elements consistent with the FDA’s findings the boxed warning will change and the medication guide will be updated and included under the REMS.

The most commonly reported adverse events among patients taking Addyi are dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth. Addyi is contraindicated in patients taking moderate or strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) inhibitors and in those with hepatic impairment.

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND THE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION AND MEDICATION GUIDE, VISIT: www.addyi.com

FEZOLINETANT FOR VMS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, TRIAL IDENTIFIERS NCT04003155, NCT04003142, AND NCT04003389

SOLUTIONS FOR OUTCOME TRACKING

DrChrono and OutcomeMD announce a partnership to track and analyze patient outcome data and confounding factors. DrChrono is an electronic health record (EHR) system, and OutcomeMD is a software solution that uses literature-validated patient-reported outcome instruments to score and track a patient’s symptom severity and inform treatment decisions for users.

Via a HIPAA compliant process, patients answer a list of questions that are accessed through a web link on their mobile or desktop devices. OutcomeMD summarizes the symptoms into a score that displays to both the physician and patient. Patients’ answers and scores are pushed to the clinician’s DrChrono EHR medical note.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.outcomemd.com

Continue to: NEW MATERNITY GOWN...

NEW MATERNITY GOWN

ImageFIRST launched a new maternity gown for expecting mothers. The Comfort Care® Maternity Gown is a lightweight, premium polyester/nylon fabric that front snaps to allow for skin-to-skin access and optional breastfeeding. The gown also includes shoulder snaps and a full cut for extra coverage and to accommodate a variety of body types, says ImageFIRST.

ImageFIRST is a national linen rental provider. It developed the Comfort Care® Maternity Gown with input from labor and delivery departments to best meet the needs of expecting mothers. It also says that a portion of the proceeds from each gown rental will be donated to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.imagefirst.com

President to nominate oncologist to lead FDA

Stephen M. Hahn, MD, a radiation oncologist and researcher, may soon take the reins of the Food and Drug Administration.

President Trump indicated his intent to nominate Dr. Hahn as FDA Commissioner in a brief Nov.1 statement that outlined Dr. Hahn’s background. Dr. Hahn currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, where he heads the radiology oncology division.

Dr. Hahn specializes in treating lung cancer and sarcoma and has authored 220 peer-reviewed original research articles, according to his biography. He was previously chair of the department of radiology oncology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and also served as a senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute.

Dr. Hahn completed his residency in radiation oncology at NCI and his residency in internal medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Margaret Foti, PhD, chief executive officer for the American Association for Cancer Research called Dr. Hahn a renowned expert in radiation oncology and research, an experienced and highly effective administrator, and an innovative leader.

“I have seen firsthand Dr. Hahn’s extraordinary dedication and commitment to cancer patients, and the AACR is extremely confident that he will be an outstanding leader for the FDA,” Dr. Foti said in a statement. “Dr. Hahn, who is board certified in both radiation and medical oncology, is esteemed for the breadth and depth of his scientific knowledge and expertise, and he has consistently advocated for a drug review process at the FDA that is both science-directed and patient-focused.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology also congratulated Dr. Hahn on the upcoming nomination, noting that he has a strong grasp of the drug development process and understands the realities of working in a complex clinical care environment.

“The role of FDA commissioner requires a strong commitment to advancing the agency’s mission to protect public health across the United States, and an understanding of how to help speed innovations to get new treatments to patients, while also ensuring the safety and efficacy of the medical products that millions of Americans rely on to manage, treat, and cure their cancer,” the society stated. “ASCO has a long and productive history of collaborating with FDA, including with current acting Commissioner Norman E. “Ned” Sharpless, MD, in support of the agency’s important role in reducing cancer incidence, advancing treatment options, and improving the lives of individuals with cancer. We look forward to continuing our close collaboration to make it possible for every American with cancer to have access to medical products that are safe and effective.”

Dr. Sharpless will return to his position as NCI director; he served as interim FDA commissioner from the April departure of then-FDA commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“As one of the nation’s leading oncologists who has devoted his entire professional career to helping patients in the fight against cancer, Ned is returning home to NCI to continue this work and we look forward to working closely with him once again,” Francis S. Collins, MD, director of the National Institutes of Health, said in a statement. “I want to thank Dr. Doug Lowy, principal deputy director of NCI, for having stepped in, once again, to take the helm at NCI and lead the institute so skillfully while Ned was at FDA.”

At press time, neither Dr. Hahn nor MD Anderson Cancer Center had returned messages seeking comment about his nomination.

Stephen M. Hahn, MD, a radiation oncologist and researcher, may soon take the reins of the Food and Drug Administration.

President Trump indicated his intent to nominate Dr. Hahn as FDA Commissioner in a brief Nov.1 statement that outlined Dr. Hahn’s background. Dr. Hahn currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, where he heads the radiology oncology division.

Dr. Hahn specializes in treating lung cancer and sarcoma and has authored 220 peer-reviewed original research articles, according to his biography. He was previously chair of the department of radiology oncology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and also served as a senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute.

Dr. Hahn completed his residency in radiation oncology at NCI and his residency in internal medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Margaret Foti, PhD, chief executive officer for the American Association for Cancer Research called Dr. Hahn a renowned expert in radiation oncology and research, an experienced and highly effective administrator, and an innovative leader.

“I have seen firsthand Dr. Hahn’s extraordinary dedication and commitment to cancer patients, and the AACR is extremely confident that he will be an outstanding leader for the FDA,” Dr. Foti said in a statement. “Dr. Hahn, who is board certified in both radiation and medical oncology, is esteemed for the breadth and depth of his scientific knowledge and expertise, and he has consistently advocated for a drug review process at the FDA that is both science-directed and patient-focused.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology also congratulated Dr. Hahn on the upcoming nomination, noting that he has a strong grasp of the drug development process and understands the realities of working in a complex clinical care environment.

“The role of FDA commissioner requires a strong commitment to advancing the agency’s mission to protect public health across the United States, and an understanding of how to help speed innovations to get new treatments to patients, while also ensuring the safety and efficacy of the medical products that millions of Americans rely on to manage, treat, and cure their cancer,” the society stated. “ASCO has a long and productive history of collaborating with FDA, including with current acting Commissioner Norman E. “Ned” Sharpless, MD, in support of the agency’s important role in reducing cancer incidence, advancing treatment options, and improving the lives of individuals with cancer. We look forward to continuing our close collaboration to make it possible for every American with cancer to have access to medical products that are safe and effective.”

Dr. Sharpless will return to his position as NCI director; he served as interim FDA commissioner from the April departure of then-FDA commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“As one of the nation’s leading oncologists who has devoted his entire professional career to helping patients in the fight against cancer, Ned is returning home to NCI to continue this work and we look forward to working closely with him once again,” Francis S. Collins, MD, director of the National Institutes of Health, said in a statement. “I want to thank Dr. Doug Lowy, principal deputy director of NCI, for having stepped in, once again, to take the helm at NCI and lead the institute so skillfully while Ned was at FDA.”

At press time, neither Dr. Hahn nor MD Anderson Cancer Center had returned messages seeking comment about his nomination.

Stephen M. Hahn, MD, a radiation oncologist and researcher, may soon take the reins of the Food and Drug Administration.

President Trump indicated his intent to nominate Dr. Hahn as FDA Commissioner in a brief Nov.1 statement that outlined Dr. Hahn’s background. Dr. Hahn currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, where he heads the radiology oncology division.

Dr. Hahn specializes in treating lung cancer and sarcoma and has authored 220 peer-reviewed original research articles, according to his biography. He was previously chair of the department of radiology oncology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and also served as a senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute.

Dr. Hahn completed his residency in radiation oncology at NCI and his residency in internal medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Margaret Foti, PhD, chief executive officer for the American Association for Cancer Research called Dr. Hahn a renowned expert in radiation oncology and research, an experienced and highly effective administrator, and an innovative leader.

“I have seen firsthand Dr. Hahn’s extraordinary dedication and commitment to cancer patients, and the AACR is extremely confident that he will be an outstanding leader for the FDA,” Dr. Foti said in a statement. “Dr. Hahn, who is board certified in both radiation and medical oncology, is esteemed for the breadth and depth of his scientific knowledge and expertise, and he has consistently advocated for a drug review process at the FDA that is both science-directed and patient-focused.”

The American Society of Clinical Oncology also congratulated Dr. Hahn on the upcoming nomination, noting that he has a strong grasp of the drug development process and understands the realities of working in a complex clinical care environment.

“The role of FDA commissioner requires a strong commitment to advancing the agency’s mission to protect public health across the United States, and an understanding of how to help speed innovations to get new treatments to patients, while also ensuring the safety and efficacy of the medical products that millions of Americans rely on to manage, treat, and cure their cancer,” the society stated. “ASCO has a long and productive history of collaborating with FDA, including with current acting Commissioner Norman E. “Ned” Sharpless, MD, in support of the agency’s important role in reducing cancer incidence, advancing treatment options, and improving the lives of individuals with cancer. We look forward to continuing our close collaboration to make it possible for every American with cancer to have access to medical products that are safe and effective.”

Dr. Sharpless will return to his position as NCI director; he served as interim FDA commissioner from the April departure of then-FDA commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“As one of the nation’s leading oncologists who has devoted his entire professional career to helping patients in the fight against cancer, Ned is returning home to NCI to continue this work and we look forward to working closely with him once again,” Francis S. Collins, MD, director of the National Institutes of Health, said in a statement. “I want to thank Dr. Doug Lowy, principal deputy director of NCI, for having stepped in, once again, to take the helm at NCI and lead the institute so skillfully while Ned was at FDA.”

At press time, neither Dr. Hahn nor MD Anderson Cancer Center had returned messages seeking comment about his nomination.

Patient-reported complications regarding PICC lines after inpatient discharge

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Background: Despite the rise in utilization of PICC lines, few studies have addressed complications experienced by patients following PICC placement, especially subsequent to discharge from the inpatient setting.

Study design: Prospective longitudinal study.

Setting: Medical inpatient wards at four U.S. hospitals in Michigan and Texas.

Synopsis: Standardized questionnaires were completed by 438 patients who underwent PICC line placement during inpatient hospitalization within 3 days of placement and at 14, 30, and 70 days. The authors found that 61.4% of patients reported at least one possible PICC-related complication or complaint. A total of 17.6% reported signs and symptoms associated with a possible bloodstream infection; however, a central line–associated bloodstream infection was documented in only 1.6% of patients in the medical record. Furthermore, 30.6% of patients reported possible symptoms associated with deep venous thrombosis (DVT), which was documented in the medical record in 7.1% of patients. These data highlight that the frequency of PICC-related complications may be underestimated when relying solely on the medical record, especially when patients receive follow-up care at different facilities. Functionally, 26% of patients reported restrictions in activities of daily living and 19.2% reported difficulty with flushing and operating the PICC.

Bottom line: More than 60% of patients with PICC lines report signs or symptoms of a PICC-related complication or an adverse impact on physical or social function.

Citation: Krein SL et al. Patient-reported complications related to peripherally inserted central catheters: A multicenter prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008726.

Dr. Cooke is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Multiple Myeloma: A New Treatment Option for Newly Diagnosed, Transplant-Ineligible Patients

Hospitalists finding their role in hospital quality ratings

CMS considers how to assess socioeconomic factors

Since 2005 the government website Hospital Compare has publicly reported quality data on hospitals, with periodic updates of their performance, including specific measures of quality. But how accurately do the ratings reflect a hospital’s actual quality of care, and what do the ratings mean for hospitalists?

Hospital Compare provides searchable, comparable information to consumers on reported quality of care data submitted by more than 4,000 Medicare-certified hospitals, along with Veterans Administration and military health system hospitals. It is designed to allow consumers to select hospitals and directly compare their mortality, complication, infection, and other performance measures on conditions such as heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, and surgical outcomes.

The Overall Hospital Quality Star Ratings, which began in 2016, combine data from more than 50 quality measures publicly reported on Hospital Compare into an overall rating of one to five stars for each hospital. These ratings are designed to enhance and supplement existing quality measures with a more “customer-centric” measure that makes it easier for consumers to act on the information. Obviously, this would be helpful to consumers who feel overwhelmed by the volume of data on the Hospital Compare website, and by the complexity of some of the measures.

A posted call in spring 2019 by CMS for public comment on possible methodological changes to the Overall Hospital Quality Star Ratings received more than 800 comments from 150 different organizations. And this past summer, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services decided to delay posting the refreshed Star Ratings in its Hospital Compare data preview reports for July 2019. The agency says it intends to release the updated information in early 2020. Meanwhile, the reported data – particularly the overall star ratings – continue to generate controversy for the hospital field.

Hospitalists’ critical role

Hospitalists are not rated individually on Hospital Compare, but they play important roles in the quality of care their hospital provides – and thus ultimately the hospital’s publicly reported rankings. Hospitalists typically are not specifically incentivized or penalized for their hospital’s performance, but this does happen in some cases.

“Hospital administrators absolutely take note of their hospital’s star ratings. These are the people hospitalists work for, and this is definitely top of their minds,” said Kate Goodrich, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Clinical Standards and Quality at CMS. “I recently spoke at an SHM annual conference and every question I was asked was about hospital ratings and the star system,” noted Dr. Goodrich, herself a practicing hospitalist at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington.

The government’s aim for Hospital Compare is to give consumers easy-to-understand indicators of the quality of care provided by hospitals, especially where they might have a choice of hospitals, such as for an elective surgery. Making that information public is also viewed as a motivator to help drive improvements in hospital performance, Dr. Goodrich said.

“In terms of what we measure, we try to make sure it’s important to patients and to clinicians. We have frontline practicing physicians, patients, and families advising us, along with methodologists and PhD researchers. These stakeholders tell us what is important to measure and why,” she said. “Hospitals and all health providers need more actionable and timely data to improve their quality of care, especially if they want to participate in accountable care organizations. And we need to make the information easy to understand.”

Dr. Goodrich sees two main themes in the public response to its request for comment. “People say the methodology we use to calculate star ratings is frustrating for hospitals, which have found it difficult to model their performance, predict their star ratings, or explain the discrepancies.” Hospitals taking care of sicker patients with lower socioeconomic status also say the ratings unfairly penalize them. “I work in a large urban hospital, and I understand this. They say we don’t take that sufficiently into account in the ratings,” she said.

“While our modeling shows that current ratings highly correlate with performance on individual measures, we have asked for comment on if and how we could adjust for socioeconomic factors. We are actively considering how to make changes to address these concerns,” Dr. Goodrich said.

In August 2019, CMS acknowledged that it plans to change the methodology used to calculate hospital star ratings in early 2021, but has not yet revealed specific details about the nature of the changes. The agency intends to propose the changes through the public rule-making process sometime in 2020.

Continuing controversy

The American Hospital Association – which has had strong concerns about the methodology and the usefulness of hospital star ratings – is pushing back on some of the changes to the system being considered by CMS. In its submitted comments, AHA supported only three of the 14 potential star ratings methodology changes being considered. AHA and the American Association of Medical Colleges, among others, have urged taking down the star ratings until major changes can be made.

“When the star ratings were first implemented, a lot of challenges became apparent right away,” said Akin Demehin, MPH, AHA’s director of quality policy. “We began to see that those hospitals that treat more complicated patients and poorer patients tended to perform more poorly on the ratings. So there was something wrong with the methodology. Then, starting in 2018, hospitals began seeing real shifts in their performance ratings when the underlying data hadn’t really changed.”

CMS uses a statistical approach called latent variable modeling. Its underlying assumption is that you can say something about a hospital’s underlying quality based on the data you already have, Mr. Demehin said, but noted “that can be a questionable assumption.” He also emphasized the need for ratings that compare hospitals that are similar in size and model to each other.

Suparna Dutta, MD, division chief, hospital medicine, Rush University, Chicago, said analyses done at Rush showed that the statistical model CMS used in calculating the star ratings was dynamically changing the weighting of certain measures in every release. “That meant one specific performance measure could play an outsized role in determining a final rating,” she said. In particular the methodology inadvertently penalized large hospitals, academic medical centers, and institutions that provide heroic care.

“We fundamentally believe that consumers should have meaningful information about hospital quality,” said Nancy Foster, AHA’s vice president for quality and patient safety policy at AHA. “We understand the complexities of Hospital Compare and the challenges of getting simple information for consumers. To its credit, CMS is thinking about how to do that, and we support them in that effort.”

Getting a handle on quality

Hospitalists are responsible for ensuring that their hospitals excel in the care of patients, said Julius Yang, MD, hospitalist and director of quality at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. That also requires keeping up on the primary public ways these issues are addressed through reporting of quality data and through reimbursement policy. “That should be part of our core competencies as hospitalists.”

Some of the measures on Hospital Compare don’t overlap much with the work of hospitalists, he noted. But for others, such as for pneumonia, COPD, and care of patients with stroke, or for mortality and 30-day readmissions rates, “we are involved, even if not directly, and certainly responsible for contributing to the outcomes and the opportunity to add value,” he said.

“When it comes to 30-day readmission rates, do we really understand the risk factors for readmissions and the barriers to patients remaining in the community after their hospital stay? Are our patients stable enough to be discharged, and have we worked with the care coordination team to make sure they have the resources they need? And have we communicated adequately with the outpatient doctor? All of these things are within the wheelhouse of the hospitalist,” Dr. Yang said. “Let’s accept that the readmissions rate, for example, is not a perfect measure of quality. But as an imperfect measure, it can point us in the right direction.”

Jose Figueroa, MD, MPH, hospitalist and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, has been studying for his health system the impact of hospital penalties such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on health equity. In general, hospitalists play an important role in dictating processes of care and serving on quality-oriented committees across multiple realms of the hospital, he said.

“What’s hard from the hospitalist’s perspective is that there don’t seem to be simple solutions to move the dial on many of these measures,” Dr. Figueroa said. “If the hospital is at three stars, can we say, okay, if we do X, Y, and Z, then our hospital will move from three to five stars? Some of these measures are so broad and not in our purview. Which ones apply to me as a hospitalist and my care processes?”

Dr. Dutta sits on the SHM Policy Committee, which has been working to bring these issues to the attention of frontline hospitalists. “Hospitalists are always going to be aligned with their hospital’s priorities. We’re in it to provide high-quality care, but there’s no magic way to do that,” she said.

Hospital Compare measures sometimes end up in hospitalist incentives plans – for example, the readmission penalty rates – even though that is a fairly arbitrary measure and hard to pin to one doctor, Dr. Dutta explained. “If you look at the evidence regarding these metrics, there are not a lot of data to show that the metrics lead to what we really want, which is better care for patients.”

A recent study in the British Medical Journal, for example, examined the association between the penalties on hospitals in the Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program and clinical outcome.1 The researchers concluded that the penalties were not associated with significant change or found to drive meaningful clinical improvement.

How can hospitalists engage with Compare?

Dr. Goodrich refers hospitalists seeking quality resources to their local quality improvement organizations (QIO) and to Hospital Improvement Innovation Networks at the regional, state, national, or hospital system level.

One helpful thing that any group of hospitalists could do, added Dr. Figueroa, is to examine the measures closely and determine which ones they think they can influence. “Then look for the hospitals that resemble ours and care for similar patients, based on the demographics. We can then say: ‘Okay, that’s a fair comparison. This can be a benchmark with our peers,’” he said. Then it’s important to ask how your hospital is doing over time on these measures, and use that to prioritize.

“You also have to appreciate that these are broad quality measures, and to impact them you have to do broad quality improvement efforts. Another piece of this is getting good at collecting and analyzing data internally in a timely fashion. You don’t want to wait 2-3 years to find out in Hospital Compare that you’re not performing well. You care about the care you provided today, not 2 or 3 years ago. Without this internal check, it’s impossible to know what to invest in – and to see if things you do are having an impact,” Dr. Figueroa said.

“As physician leaders, this is a real opportunity for us to trigger a conversation with our hospital’s administration around what we went into medicine for in the first place – to improve our patients’ care,” said Dr. Goodrich. She said Hospital Compare is one tool for sparking systemic quality improvement across the hospital – which is an important part of the hospitalist’s job. “If you want to be a bigger star within your hospital, show that level of commitment. It likely would be welcomed by your hospital.”

Reference

1. Sankaran R et al. Changes in hospital safety following penalties in the US Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2019 Jul 3 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4109.

CMS considers how to assess socioeconomic factors

CMS considers how to assess socioeconomic factors

Since 2005 the government website Hospital Compare has publicly reported quality data on hospitals, with periodic updates of their performance, including specific measures of quality. But how accurately do the ratings reflect a hospital’s actual quality of care, and what do the ratings mean for hospitalists?

Hospital Compare provides searchable, comparable information to consumers on reported quality of care data submitted by more than 4,000 Medicare-certified hospitals, along with Veterans Administration and military health system hospitals. It is designed to allow consumers to select hospitals and directly compare their mortality, complication, infection, and other performance measures on conditions such as heart attacks, heart failure, pneumonia, and surgical outcomes.

The Overall Hospital Quality Star Ratings, which began in 2016, combine data from more than 50 quality measures publicly reported on Hospital Compare into an overall rating of one to five stars for each hospital. These ratings are designed to enhance and supplement existing quality measures with a more “customer-centric” measure that makes it easier for consumers to act on the information. Obviously, this would be helpful to consumers who feel overwhelmed by the volume of data on the Hospital Compare website, and by the complexity of some of the measures.

A posted call in spring 2019 by CMS for public comment on possible methodological changes to the Overall Hospital Quality Star Ratings received more than 800 comments from 150 different organizations. And this past summer, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services decided to delay posting the refreshed Star Ratings in its Hospital Compare data preview reports for July 2019. The agency says it intends to release the updated information in early 2020. Meanwhile, the reported data – particularly the overall star ratings – continue to generate controversy for the hospital field.

Hospitalists’ critical role

Hospitalists are not rated individually on Hospital Compare, but they play important roles in the quality of care their hospital provides – and thus ultimately the hospital’s publicly reported rankings. Hospitalists typically are not specifically incentivized or penalized for their hospital’s performance, but this does happen in some cases.

“Hospital administrators absolutely take note of their hospital’s star ratings. These are the people hospitalists work for, and this is definitely top of their minds,” said Kate Goodrich, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Clinical Standards and Quality at CMS. “I recently spoke at an SHM annual conference and every question I was asked was about hospital ratings and the star system,” noted Dr. Goodrich, herself a practicing hospitalist at George Washington University Medical Center in Washington.

The government’s aim for Hospital Compare is to give consumers easy-to-understand indicators of the quality of care provided by hospitals, especially where they might have a choice of hospitals, such as for an elective surgery. Making that information public is also viewed as a motivator to help drive improvements in hospital performance, Dr. Goodrich said.

“In terms of what we measure, we try to make sure it’s important to patients and to clinicians. We have frontline practicing physicians, patients, and families advising us, along with methodologists and PhD researchers. These stakeholders tell us what is important to measure and why,” she said. “Hospitals and all health providers need more actionable and timely data to improve their quality of care, especially if they want to participate in accountable care organizations. And we need to make the information easy to understand.”

Dr. Goodrich sees two main themes in the public response to its request for comment. “People say the methodology we use to calculate star ratings is frustrating for hospitals, which have found it difficult to model their performance, predict their star ratings, or explain the discrepancies.” Hospitals taking care of sicker patients with lower socioeconomic status also say the ratings unfairly penalize them. “I work in a large urban hospital, and I understand this. They say we don’t take that sufficiently into account in the ratings,” she said.

“While our modeling shows that current ratings highly correlate with performance on individual measures, we have asked for comment on if and how we could adjust for socioeconomic factors. We are actively considering how to make changes to address these concerns,” Dr. Goodrich said.

In August 2019, CMS acknowledged that it plans to change the methodology used to calculate hospital star ratings in early 2021, but has not yet revealed specific details about the nature of the changes. The agency intends to propose the changes through the public rule-making process sometime in 2020.

Continuing controversy

The American Hospital Association – which has had strong concerns about the methodology and the usefulness of hospital star ratings – is pushing back on some of the changes to the system being considered by CMS. In its submitted comments, AHA supported only three of the 14 potential star ratings methodology changes being considered. AHA and the American Association of Medical Colleges, among others, have urged taking down the star ratings until major changes can be made.

“When the star ratings were first implemented, a lot of challenges became apparent right away,” said Akin Demehin, MPH, AHA’s director of quality policy. “We began to see that those hospitals that treat more complicated patients and poorer patients tended to perform more poorly on the ratings. So there was something wrong with the methodology. Then, starting in 2018, hospitals began seeing real shifts in their performance ratings when the underlying data hadn’t really changed.”

CMS uses a statistical approach called latent variable modeling. Its underlying assumption is that you can say something about a hospital’s underlying quality based on the data you already have, Mr. Demehin said, but noted “that can be a questionable assumption.” He also emphasized the need for ratings that compare hospitals that are similar in size and model to each other.

Suparna Dutta, MD, division chief, hospital medicine, Rush University, Chicago, said analyses done at Rush showed that the statistical model CMS used in calculating the star ratings was dynamically changing the weighting of certain measures in every release. “That meant one specific performance measure could play an outsized role in determining a final rating,” she said. In particular the methodology inadvertently penalized large hospitals, academic medical centers, and institutions that provide heroic care.

“We fundamentally believe that consumers should have meaningful information about hospital quality,” said Nancy Foster, AHA’s vice president for quality and patient safety policy at AHA. “We understand the complexities of Hospital Compare and the challenges of getting simple information for consumers. To its credit, CMS is thinking about how to do that, and we support them in that effort.”

Getting a handle on quality

Hospitalists are responsible for ensuring that their hospitals excel in the care of patients, said Julius Yang, MD, hospitalist and director of quality at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. That also requires keeping up on the primary public ways these issues are addressed through reporting of quality data and through reimbursement policy. “That should be part of our core competencies as hospitalists.”

Some of the measures on Hospital Compare don’t overlap much with the work of hospitalists, he noted. But for others, such as for pneumonia, COPD, and care of patients with stroke, or for mortality and 30-day readmissions rates, “we are involved, even if not directly, and certainly responsible for contributing to the outcomes and the opportunity to add value,” he said.