User login

Topical budesonide effective for eosinophilic esophagitis in pivotal trial

SAN ANTONIO – An investigational muco-adherent swallowed formulation of budesonide developed specifically for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis aced all primary and secondary endpoints in a pivotal, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial, Ikuo Hirano, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

This is welcome news for patients with this chronic immune-mediated disease, for which no Food and Drug Administration–approved drug therapy exists yet.

“This is the first phase 3 trial to demonstrate efficacy using the validated Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire, the first completed phase 3 trial of any medical therapeutic for eosinophilic esophagitis, and the largest clinical trial for eosinophilic esophagitis conducted to date,” declared Dr. Hirano, professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

This was a 12-week induction therapy study including 318 adolescents and adults randomized 2:1 to 2 mg of budesonide oral suspension (BOS) or placebo twice daily. Patients were instructed not to eat or drink anything for 30 minutes afterward to avoid washing away the medication.

This was a severely affected patient population with high-level inflammatory activity: their mean baseline peak eosinophil count was 75 cells per high-power field, well above the diagnostic threshold of 50 eosinophils per high-power field. In keeping with a requirement for study participation, all patients had failed to respond to at least 6 weeks of high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy. They also had to experience solid food dysphagia on at least 4 days per 2 weeks. More than 40% of subjects had previously undergone esophageal dilation.

One coprimary endpoint addressed histologic response, defined as 6 or fewer eosinophils per high-power field after 12 weeks of double-blind treatment. The histologic response rate was 53% in the BOS group and 1% in placebo-treated controls.

The other coprimary endpoint was symptom response as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score. This was achieved in 53% of patients on BOS and 39% of controls.

The prespecified key secondary endpoint was the absolute reduction in Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score through week 12. From a mean baseline score of 30 out of a possible 84, the swallowed steroid recipients experienced a mean 13-point improvement, compared with a 9.1-improvement for those on placebo.

The topical budesonide group also did significantly better than placebo in terms of all other secondary endpoints. Endoscopic improvement as reflected in the mean Eosinophilic Esophagitis Reference Score was greater in the BOS group by a margin of 4 versus 2.2 points. A high-bar histologic response rate of no more than a single eosinophil per high-power field at week 12 was achieved in one-third of the BOS group and zero controls. The overall peak eosinophil count from baseline to week 12 dropped by an average of 55.2 cells per high-power field in the budesonide group, compared to a 7.6-eosinophil decrease in controls. And the proportion of patients with no more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field at week 12 was 62% with BOS, compared with 1% with placebo.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were similar in the two study arms and were mild to moderate in severity. Of note, however, the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis rate in the topical corticosteroid group was twice that seen in the placebo arm. Adrenal function as assessed by ACTH stimulation testing at baseline and 12 weeks was normal in 88% of the BOS group and 94% of controls.

Dr. Hirano noted that adrenal function will continue to be carefully monitored during an ongoing, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled BOS maintenance study.

He reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Takeda, the study sponsor, as well as a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

This is an exciting abstract from Hirano et al. highlighting the results of the first phase 3 trial for an eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) treatment. Furthermore, the trial design, which included histologic and symptom-based endpoints, may be critical to attaining Food and Drug Administration approval. Given the lack of any FDA-approved therapies for EoE, the results of this trial are welcome news for clinicians who treat patients with EoE.

This study of a topical muco-adherent steroid formulation (budesonide oral suspension) specifically designed to treat EoE significantly improved histologic, symptom, and endoscopic endpoints, compared with placebo. Of note, 62% of patients on the drug achieved a histologic response of less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field (53% achieved less than 6), compared with 1% in the placebo group. This study supplements the existing data supporting the use of swallowed topical steroids in EoE.

It is important to note that the subjects in this study had fairly severe disease, with more than 40% having previously undergone esophageal dilation and all patients experiencing dysphagia, on average, multiple times per week. Given the disease severity in the subject population, there can be even greater enthusiasm regarding the response rates for the budesonide group. Also notable is the relatively high dose of budesonide used in this study (2 mg twice daily), which may have contributed to the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis. Importantly, adrenal function was assessed during the study and will be monitored during the ongoing maintenance portion of the study.

These last points do highlight the challenges of treating more severe EoE given 38% of patients did not achieve histologic remission (less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field) despite the doses of budesonide used in this study. This emphasizes the need for other treatment options for steroid nonresponders.

Taken together, these results are very exciting and will lead to an FDA-approved EoE treatment in short order.

Paul Menard-Katcher, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He has no conflicts of interest.

This is an exciting abstract from Hirano et al. highlighting the results of the first phase 3 trial for an eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) treatment. Furthermore, the trial design, which included histologic and symptom-based endpoints, may be critical to attaining Food and Drug Administration approval. Given the lack of any FDA-approved therapies for EoE, the results of this trial are welcome news for clinicians who treat patients with EoE.

This study of a topical muco-adherent steroid formulation (budesonide oral suspension) specifically designed to treat EoE significantly improved histologic, symptom, and endoscopic endpoints, compared with placebo. Of note, 62% of patients on the drug achieved a histologic response of less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field (53% achieved less than 6), compared with 1% in the placebo group. This study supplements the existing data supporting the use of swallowed topical steroids in EoE.

It is important to note that the subjects in this study had fairly severe disease, with more than 40% having previously undergone esophageal dilation and all patients experiencing dysphagia, on average, multiple times per week. Given the disease severity in the subject population, there can be even greater enthusiasm regarding the response rates for the budesonide group. Also notable is the relatively high dose of budesonide used in this study (2 mg twice daily), which may have contributed to the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis. Importantly, adrenal function was assessed during the study and will be monitored during the ongoing maintenance portion of the study.

These last points do highlight the challenges of treating more severe EoE given 38% of patients did not achieve histologic remission (less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field) despite the doses of budesonide used in this study. This emphasizes the need for other treatment options for steroid nonresponders.

Taken together, these results are very exciting and will lead to an FDA-approved EoE treatment in short order.

Paul Menard-Katcher, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He has no conflicts of interest.

This is an exciting abstract from Hirano et al. highlighting the results of the first phase 3 trial for an eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) treatment. Furthermore, the trial design, which included histologic and symptom-based endpoints, may be critical to attaining Food and Drug Administration approval. Given the lack of any FDA-approved therapies for EoE, the results of this trial are welcome news for clinicians who treat patients with EoE.

This study of a topical muco-adherent steroid formulation (budesonide oral suspension) specifically designed to treat EoE significantly improved histologic, symptom, and endoscopic endpoints, compared with placebo. Of note, 62% of patients on the drug achieved a histologic response of less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field (53% achieved less than 6), compared with 1% in the placebo group. This study supplements the existing data supporting the use of swallowed topical steroids in EoE.

It is important to note that the subjects in this study had fairly severe disease, with more than 40% having previously undergone esophageal dilation and all patients experiencing dysphagia, on average, multiple times per week. Given the disease severity in the subject population, there can be even greater enthusiasm regarding the response rates for the budesonide group. Also notable is the relatively high dose of budesonide used in this study (2 mg twice daily), which may have contributed to the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis. Importantly, adrenal function was assessed during the study and will be monitored during the ongoing maintenance portion of the study.

These last points do highlight the challenges of treating more severe EoE given 38% of patients did not achieve histologic remission (less than 15 eosinophils per high-power field) despite the doses of budesonide used in this study. This emphasizes the need for other treatment options for steroid nonresponders.

Taken together, these results are very exciting and will lead to an FDA-approved EoE treatment in short order.

Paul Menard-Katcher, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He has no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – An investigational muco-adherent swallowed formulation of budesonide developed specifically for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis aced all primary and secondary endpoints in a pivotal, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial, Ikuo Hirano, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

This is welcome news for patients with this chronic immune-mediated disease, for which no Food and Drug Administration–approved drug therapy exists yet.

“This is the first phase 3 trial to demonstrate efficacy using the validated Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire, the first completed phase 3 trial of any medical therapeutic for eosinophilic esophagitis, and the largest clinical trial for eosinophilic esophagitis conducted to date,” declared Dr. Hirano, professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

This was a 12-week induction therapy study including 318 adolescents and adults randomized 2:1 to 2 mg of budesonide oral suspension (BOS) or placebo twice daily. Patients were instructed not to eat or drink anything for 30 minutes afterward to avoid washing away the medication.

This was a severely affected patient population with high-level inflammatory activity: their mean baseline peak eosinophil count was 75 cells per high-power field, well above the diagnostic threshold of 50 eosinophils per high-power field. In keeping with a requirement for study participation, all patients had failed to respond to at least 6 weeks of high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy. They also had to experience solid food dysphagia on at least 4 days per 2 weeks. More than 40% of subjects had previously undergone esophageal dilation.

One coprimary endpoint addressed histologic response, defined as 6 or fewer eosinophils per high-power field after 12 weeks of double-blind treatment. The histologic response rate was 53% in the BOS group and 1% in placebo-treated controls.

The other coprimary endpoint was symptom response as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score. This was achieved in 53% of patients on BOS and 39% of controls.

The prespecified key secondary endpoint was the absolute reduction in Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score through week 12. From a mean baseline score of 30 out of a possible 84, the swallowed steroid recipients experienced a mean 13-point improvement, compared with a 9.1-improvement for those on placebo.

The topical budesonide group also did significantly better than placebo in terms of all other secondary endpoints. Endoscopic improvement as reflected in the mean Eosinophilic Esophagitis Reference Score was greater in the BOS group by a margin of 4 versus 2.2 points. A high-bar histologic response rate of no more than a single eosinophil per high-power field at week 12 was achieved in one-third of the BOS group and zero controls. The overall peak eosinophil count from baseline to week 12 dropped by an average of 55.2 cells per high-power field in the budesonide group, compared to a 7.6-eosinophil decrease in controls. And the proportion of patients with no more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field at week 12 was 62% with BOS, compared with 1% with placebo.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were similar in the two study arms and were mild to moderate in severity. Of note, however, the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis rate in the topical corticosteroid group was twice that seen in the placebo arm. Adrenal function as assessed by ACTH stimulation testing at baseline and 12 weeks was normal in 88% of the BOS group and 94% of controls.

Dr. Hirano noted that adrenal function will continue to be carefully monitored during an ongoing, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled BOS maintenance study.

He reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Takeda, the study sponsor, as well as a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN ANTONIO – An investigational muco-adherent swallowed formulation of budesonide developed specifically for treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis aced all primary and secondary endpoints in a pivotal, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial, Ikuo Hirano, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

This is welcome news for patients with this chronic immune-mediated disease, for which no Food and Drug Administration–approved drug therapy exists yet.

“This is the first phase 3 trial to demonstrate efficacy using the validated Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire, the first completed phase 3 trial of any medical therapeutic for eosinophilic esophagitis, and the largest clinical trial for eosinophilic esophagitis conducted to date,” declared Dr. Hirano, professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

This was a 12-week induction therapy study including 318 adolescents and adults randomized 2:1 to 2 mg of budesonide oral suspension (BOS) or placebo twice daily. Patients were instructed not to eat or drink anything for 30 minutes afterward to avoid washing away the medication.

This was a severely affected patient population with high-level inflammatory activity: their mean baseline peak eosinophil count was 75 cells per high-power field, well above the diagnostic threshold of 50 eosinophils per high-power field. In keeping with a requirement for study participation, all patients had failed to respond to at least 6 weeks of high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy. They also had to experience solid food dysphagia on at least 4 days per 2 weeks. More than 40% of subjects had previously undergone esophageal dilation.

One coprimary endpoint addressed histologic response, defined as 6 or fewer eosinophils per high-power field after 12 weeks of double-blind treatment. The histologic response rate was 53% in the BOS group and 1% in placebo-treated controls.

The other coprimary endpoint was symptom response as defined by at least a 30% reduction from baseline in the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score. This was achieved in 53% of patients on BOS and 39% of controls.

The prespecified key secondary endpoint was the absolute reduction in Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire score through week 12. From a mean baseline score of 30 out of a possible 84, the swallowed steroid recipients experienced a mean 13-point improvement, compared with a 9.1-improvement for those on placebo.

The topical budesonide group also did significantly better than placebo in terms of all other secondary endpoints. Endoscopic improvement as reflected in the mean Eosinophilic Esophagitis Reference Score was greater in the BOS group by a margin of 4 versus 2.2 points. A high-bar histologic response rate of no more than a single eosinophil per high-power field at week 12 was achieved in one-third of the BOS group and zero controls. The overall peak eosinophil count from baseline to week 12 dropped by an average of 55.2 cells per high-power field in the budesonide group, compared to a 7.6-eosinophil decrease in controls. And the proportion of patients with no more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field at week 12 was 62% with BOS, compared with 1% with placebo.

Treatment-emergent adverse events were similar in the two study arms and were mild to moderate in severity. Of note, however, the 3.8% incidence of esophageal candidiasis rate in the topical corticosteroid group was twice that seen in the placebo arm. Adrenal function as assessed by ACTH stimulation testing at baseline and 12 weeks was normal in 88% of the BOS group and 94% of controls.

Dr. Hirano noted that adrenal function will continue to be carefully monitored during an ongoing, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled BOS maintenance study.

He reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Takeda, the study sponsor, as well as a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM ACG 2019

Cost-effective treatment for relapsing MS patients

Key clinical point: Teriflunomide may be more cost effective than interferon beta-1b for relapsing MS patients.

Major finding: Over the course of 20 years, the cost of treatment with teriflunomide would cost $567,767, compared with the cost of treatment for interferon beta of $620,191 for patients in China.

Study details: A Markov cost model was developed for the study. Eleven neurologists were surveyed throughout China about costs related to treatment for RMS including acquisition and administration, patient monitoring, treating relapse, and the management of adverse events.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi China. Two study investigators reported being employees of the company.

Citation: Xu Y, et al. Clin Drug Investig. 2019 Mar;39(3):331-340. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00750-3.

Key clinical point: Teriflunomide may be more cost effective than interferon beta-1b for relapsing MS patients.

Major finding: Over the course of 20 years, the cost of treatment with teriflunomide would cost $567,767, compared with the cost of treatment for interferon beta of $620,191 for patients in China.

Study details: A Markov cost model was developed for the study. Eleven neurologists were surveyed throughout China about costs related to treatment for RMS including acquisition and administration, patient monitoring, treating relapse, and the management of adverse events.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi China. Two study investigators reported being employees of the company.

Citation: Xu Y, et al. Clin Drug Investig. 2019 Mar;39(3):331-340. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00750-3.

Key clinical point: Teriflunomide may be more cost effective than interferon beta-1b for relapsing MS patients.

Major finding: Over the course of 20 years, the cost of treatment with teriflunomide would cost $567,767, compared with the cost of treatment for interferon beta of $620,191 for patients in China.

Study details: A Markov cost model was developed for the study. Eleven neurologists were surveyed throughout China about costs related to treatment for RMS including acquisition and administration, patient monitoring, treating relapse, and the management of adverse events.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi China. Two study investigators reported being employees of the company.

Citation: Xu Y, et al. Clin Drug Investig. 2019 Mar;39(3):331-340. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00750-3.

Fresh RBCs offer no benefit over older cells in pediatric ICU

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Fresh red cells were no better than conventional stored red cells when transfused into critically ill children, and there was some evidence in the ABC PICU trial suggesting that fresh red cells could be associated with a higher incidence of posttransfusion organ dysfunction.

Among 1,461 children randomly assigned to receive RBC transfusions with either fresh cells (stored for 7 days or less) or standard-issue cells (stored anywhere from 2-42 days), there were no differences in the primary endpoint of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), reported Philip Spinella, MD from Washington University, St. Louis.

“Our results do not support current blood management policies that recommend providing fresh red cell units to certain populations of children,” he said at the annual meeting of AABB, the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

The study findings support those of a systematic review (Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:77-88), whose authors found that “transfusion of fresher RBCs is not associated with decreased risk of death but is associated with higher rates of transfusion reactions and possibly infection.” The authors of the review concluded that “the current evidence does not support a change from current usual transfusion practice.”

Is fresh really better?

The launch of the ABC PICU trial was motivated by laboratory and observational evidence suggesting that older RBCs may be less safe or efficacious than fresh RBCs, especially in vulnerable populations such as critically ill children.

Although physician and institutional practice has been to transfuse fresh RBCs to some pediatric patients, the standard practice among blood banks has been to deliver the oldest stored units first, in an effort to prevent product wastage.

Dr. Spinella and colleagues across 50 centers in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, and Israel enrolled patients who were admitted to a pediatric ICU who received their first RBC transfusion within 7 days of admission and had an expected length of stay after transfusion of more than 24 hours.

The median patient age was 1.8 years for those who received fresh cells, and 1.9 years for those who received usual care.

There were 1,630 transfusions of fresh RBCs stored for a median of 5 days and 1,533 transfusions of standard RBCs stored for a median of 18 days. The median volume of red cell units transfused was 17.5 mL/kg in the fresh group and 16.6 mL/kg in the standard group.

The incidence of NPMODS was 20.2% for fresh-RBC recipients and 18.2% for standard-product recipients. The absolute difference of 2.0% was not statistically significant.

There were also no significant differences in the timing of NPMODS occurrence between the groups, and no significant differences by patient age (28 days or younger, 29-365 days old, or older than 1 year).

Similarly, there were no differences in NPMODS incidence between the groups by country, although in Canada there was a trend toward a higher incidence of organ dysfunction in the group that received fresh RBCs, Dr. Spinella noted.

Additionally, there were no significant differences between the groups by admission to the ICU by medical, surgical, cardiac, or trauma services; no differences by quartile of red cell volume transfused; and no differences in mortality rates either in the ICU or the main hospital, or at 28 or 90 days after discharge.

Why no difference?

Seeking explanations for why fresh RBCs did not perform better than older stored cells, Dr. Spinella suggested that changes such as storage lesions that occur over time may not be as clinically relevant as previously supposed.

“Another possibility is that these study patients didn’t need red cells to begin with to improve oxygen delivery,” he said.

Other potential explanations include the possibility that exposure to fresh red cells may be associated with immune suppression because viable white cells may also be present in the product, and that the chronological age of a stored red cell unit may not equate to its biologic or metabolic age or performance, he added.

ABC PICU was supported by Washington University; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian and French governments; and other groups. Dr. Spinella reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2019

Impact of polypharmacy in RRMS

Key clinical point: Polypharmacy frequency can have a negative effect on relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) patients.

Major finding: The proportion of polypharmacy among patients with a secondary illness to RRMS was four times higher than in patients without a secondary illness. Patients with polypharmacy were older, had a lower level of education, and had higher comorbidities than patients without polypharmacy.

Study details: Subgroups of 145 RRMS patients were analyzed. The subgroups were patients with polypharmacy, patients without polypharmacy, patients with secondary illness, and patients without secondary illness.

Disclosures: Michael Hecker support from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Novartis and Teva. Uwe Klaus Zettl received support from Almirall, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva. Niklas Frahm has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Citation: Frahm N, et al. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 24;14(1):e0211120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211120.

Key clinical point: Polypharmacy frequency can have a negative effect on relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) patients.

Major finding: The proportion of polypharmacy among patients with a secondary illness to RRMS was four times higher than in patients without a secondary illness. Patients with polypharmacy were older, had a lower level of education, and had higher comorbidities than patients without polypharmacy.

Study details: Subgroups of 145 RRMS patients were analyzed. The subgroups were patients with polypharmacy, patients without polypharmacy, patients with secondary illness, and patients without secondary illness.

Disclosures: Michael Hecker support from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Novartis and Teva. Uwe Klaus Zettl received support from Almirall, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva. Niklas Frahm has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Citation: Frahm N, et al. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 24;14(1):e0211120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211120.

Key clinical point: Polypharmacy frequency can have a negative effect on relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) patients.

Major finding: The proportion of polypharmacy among patients with a secondary illness to RRMS was four times higher than in patients without a secondary illness. Patients with polypharmacy were older, had a lower level of education, and had higher comorbidities than patients without polypharmacy.

Study details: Subgroups of 145 RRMS patients were analyzed. The subgroups were patients with polypharmacy, patients without polypharmacy, patients with secondary illness, and patients without secondary illness.

Disclosures: Michael Hecker support from Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Novartis and Teva. Uwe Klaus Zettl received support from Almirall, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva. Niklas Frahm has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Citation: Frahm N, et al. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 24;14(1):e0211120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211120.

Algorithms help identify RRMS patients

Key clinical point: Two algorithms identified in a new study can be used for future clinical research of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Major finding: Using EHRs and the coded health care claims of 5,308 patients with possible MS, 837 and 2,271 were identified as having RRMS, respectively. There were also 779 patients identified using both algorithms.

Study details: Two different algorithms “unstructured clinical notes (EHR clinical notes-based algorithm) and structured/coded data (claims-based algorithms)” were used to identify patients with RRMS.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Van Le H, et al. Value Health. 2019 Jan;22(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.06.014.

Key clinical point: Two algorithms identified in a new study can be used for future clinical research of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Major finding: Using EHRs and the coded health care claims of 5,308 patients with possible MS, 837 and 2,271 were identified as having RRMS, respectively. There were also 779 patients identified using both algorithms.

Study details: Two different algorithms “unstructured clinical notes (EHR clinical notes-based algorithm) and structured/coded data (claims-based algorithms)” were used to identify patients with RRMS.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Van Le H, et al. Value Health. 2019 Jan;22(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.06.014.

Key clinical point: Two algorithms identified in a new study can be used for future clinical research of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Major finding: Using EHRs and the coded health care claims of 5,308 patients with possible MS, 837 and 2,271 were identified as having RRMS, respectively. There were also 779 patients identified using both algorithms.

Study details: Two different algorithms “unstructured clinical notes (EHR clinical notes-based algorithm) and structured/coded data (claims-based algorithms)” were used to identify patients with RRMS.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Citation: Van Le H, et al. Value Health. 2019 Jan;22(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.06.014.

Tips for helping children improve adherence to asthma treatment

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”

Studies have demonstrated that the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a decreased risk of death from asthma (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-6). “I suspect that most parents would trade 1 cm of height to reduce the risk of death in their child,” Dr. Laubach said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”

Studies have demonstrated that the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a decreased risk of death from asthma (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-6). “I suspect that most parents would trade 1 cm of height to reduce the risk of death in their child,” Dr. Laubach said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Up to 50% of children with asthma struggle to control their condition, yet fewer than 5% of pediatric asthma is severe and truly resistant to therapy, according to Susan Laubach, MD.

Other factors may make asthma difficult to control and may be modifiable, especially nonadherence to recommended treatment. In fact, up to 70% of patients report poor adherence to recommended treatment, Dr. Laubach said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Barriers to adherence may be related to the treatments themselves,” she said. “These include complex treatment schedules, lack of an immediately discernible beneficial effect, adverse effects of the medication, and prohibitive costs.”

Dr. Laubach, who directs the allergy clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, said that clinician-related barriers also influence patient adherence to recommended treatment, including difficulty scheduling appointments or seeing the same physician, a perceived lack of empathy, or failure to discuss the family’s concerns or answer questions. Common patient-related barriers include poor understanding of how the medication may help or how to use the inhalers.

“Some families have a lack of trust in the health care system, or certain beliefs about illness or medication that may hamper motivation to adhere,” she added. “Social issues such as poverty, lack of insurance, or a chaotic home environment may make it difficult for a patient to adhere to recommended treatment.”

In 2013, researchers led by Ted Klok, MD, PhD, of Princess Amalia Children’s Clinic in the Netherlands, explored practical ways to improve treatment adherence in children with pediatric respiratory disease (Breathe. 2013;9:268-77). One of their recommendations involves “five E’s” of ensuring optimal adherence. They include:

Ensure close and repeated follow-up to help build trust and partnership. “I’ll often follow up every month until I know a patient has gained good control of his or her asthma,” said Dr. Laubach, who was not involved in developing the recommendations. “Then I’ll follow up every 3 months.”

Explore the patient’s views, beliefs, and preferences. “You can do this by inviting questions or following up on comments or remarks made about the treatment plan,” she said. “This doesn’t have to take long. You can simply ask, ‘What are you concerned might happen if your child uses an inhaled corticosteroid?’ Or, ‘What have you heard about inhaled steroids?’ ”

Express empathy using active listening techniques tailored to the patient’s needs. Consider phrasing like, “I understand what you’re saying. In a perfect world, your child would not have to use any medications. But when he can’t sleep because he’s coughing so much, the benefit of this medication probably outweighs any potential risks.”

Exercise shared decision making. For example, if the parent of one of your patients has to leave for work very early in the morning, “maybe find a way to adjust to once-daily dosing so that appropriate doses can be given at bedtime when the parent is consistently available,” Dr. Laubach said.

Evaluate adherence in a nonjudgmental fashion. Evidence suggests that most patients with asthma miss a couple of medication doses now and then. She makes it a point to ask patients, “If you’re supposed to take 14 doses a week, how many do you think you actually take?” Their response “gives me an idea about their level of adherence and it opens a discussion into why they may miss doses, so that we can find a solution to help improve adherence.”

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study found a significant reduction in height velocity in patients treated with budesonide, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2012;367[10]:904-12). “However, most of this reduction occurred in the first year of treatment, was not additive over time, and led in average to a 1-cm difference in height as an adult,” said Dr. Laubach, who is also of the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “So while it must be acknowledged that high-dose inhaled corticosteroids may affect growth, who do we put on inhaled corticosteroids? People who can’t breathe.”

Studies have demonstrated that the regular use of inhaled corticosteroids is associated with a decreased risk of death from asthma (N Engl J Med. 2000;343:332-6). “I suspect that most parents would trade 1 cm of height to reduce the risk of death in their child,” Dr. Laubach said.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2019

Levofloxacin prophylaxis improves survival in newly diagnosed myeloma

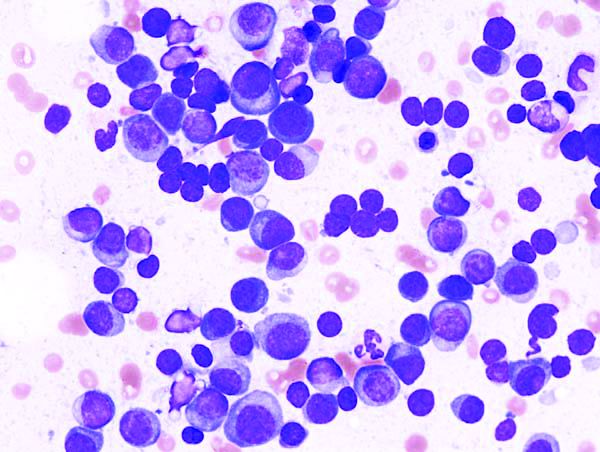

Adding levofloxacin to antimyeloma therapy improved survival and reduced infections in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, findings from a phase 3 trial suggest.

The advantages of levofloxacin prophylaxis appear to offset the potential risks in patients with newly diagnosed disease, explained Mark T. Drayson, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues. The study was published in the Lancet Oncology.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 TEAMM study enrolled 977 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. The effects of antimicrobial prophylaxis on infection risk and infection-related mortality were evaluated across 93 hospitals throughout the United Kingdom.

Study patients were randomly assigned to receive 500 mg of oral levofloxacin once daily or placebo for a total of 12 weeks. If applicable, dose adjustments were made based on estimated glomerular filtration rate.

At baseline, the team collected stool samples and nasal swabs, and follow-up assessment occurred every 4 weeks for up to 1 year. The primary endpoint was time to death (all causes) or first febrile event from the start of prophylactic therapy to 12 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 12 months, first febrile episodes or deaths were significantly lower for patients in the levofloxacin arm (19%), compared with the placebo arm (27%) for a hazard ratio for time to first event of 0.66 (95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.86; P = .0018).

With respect to safety, the rates of serious adverse events were similar between the study arms, with the exception of tendinitis in the levofloxacin group (1%). Among all patients, a total of 597 serious toxicities were observed from baseline to 16 weeks (52% in the levofloxacin arm vs. 48% in the placebo arm).

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that the use of prophylactic antibiotics has shown a survival benefit in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma,” the researchers reported.

One key limitation of the study was the younger patient population relative to the general population. As a result, differences in survival estimates could exist between the trial and real-world populations, they noted.

“Patients with newly diagnosed myeloma could benefit from levofloxacin prophylaxis, although local antibiotic resistance proportions must be considered,” the researchers cautioned.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported financial affiliations with Actelion, Astellas, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and other companies.

SOURCE: Drayson MT et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30506-6.

Adding levofloxacin to antimyeloma therapy improved survival and reduced infections in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, findings from a phase 3 trial suggest.

The advantages of levofloxacin prophylaxis appear to offset the potential risks in patients with newly diagnosed disease, explained Mark T. Drayson, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues. The study was published in the Lancet Oncology.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 TEAMM study enrolled 977 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. The effects of antimicrobial prophylaxis on infection risk and infection-related mortality were evaluated across 93 hospitals throughout the United Kingdom.

Study patients were randomly assigned to receive 500 mg of oral levofloxacin once daily or placebo for a total of 12 weeks. If applicable, dose adjustments were made based on estimated glomerular filtration rate.

At baseline, the team collected stool samples and nasal swabs, and follow-up assessment occurred every 4 weeks for up to 1 year. The primary endpoint was time to death (all causes) or first febrile event from the start of prophylactic therapy to 12 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 12 months, first febrile episodes or deaths were significantly lower for patients in the levofloxacin arm (19%), compared with the placebo arm (27%) for a hazard ratio for time to first event of 0.66 (95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.86; P = .0018).

With respect to safety, the rates of serious adverse events were similar between the study arms, with the exception of tendinitis in the levofloxacin group (1%). Among all patients, a total of 597 serious toxicities were observed from baseline to 16 weeks (52% in the levofloxacin arm vs. 48% in the placebo arm).

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that the use of prophylactic antibiotics has shown a survival benefit in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma,” the researchers reported.

One key limitation of the study was the younger patient population relative to the general population. As a result, differences in survival estimates could exist between the trial and real-world populations, they noted.

“Patients with newly diagnosed myeloma could benefit from levofloxacin prophylaxis, although local antibiotic resistance proportions must be considered,” the researchers cautioned.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported financial affiliations with Actelion, Astellas, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and other companies.

SOURCE: Drayson MT et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30506-6.

Adding levofloxacin to antimyeloma therapy improved survival and reduced infections in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma, findings from a phase 3 trial suggest.

The advantages of levofloxacin prophylaxis appear to offset the potential risks in patients with newly diagnosed disease, explained Mark T. Drayson, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues. The study was published in the Lancet Oncology.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 TEAMM study enrolled 977 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. The effects of antimicrobial prophylaxis on infection risk and infection-related mortality were evaluated across 93 hospitals throughout the United Kingdom.

Study patients were randomly assigned to receive 500 mg of oral levofloxacin once daily or placebo for a total of 12 weeks. If applicable, dose adjustments were made based on estimated glomerular filtration rate.

At baseline, the team collected stool samples and nasal swabs, and follow-up assessment occurred every 4 weeks for up to 1 year. The primary endpoint was time to death (all causes) or first febrile event from the start of prophylactic therapy to 12 weeks.

After a median follow-up of 12 months, first febrile episodes or deaths were significantly lower for patients in the levofloxacin arm (19%), compared with the placebo arm (27%) for a hazard ratio for time to first event of 0.66 (95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.86; P = .0018).

With respect to safety, the rates of serious adverse events were similar between the study arms, with the exception of tendinitis in the levofloxacin group (1%). Among all patients, a total of 597 serious toxicities were observed from baseline to 16 weeks (52% in the levofloxacin arm vs. 48% in the placebo arm).

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that the use of prophylactic antibiotics has shown a survival benefit in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma,” the researchers reported.

One key limitation of the study was the younger patient population relative to the general population. As a result, differences in survival estimates could exist between the trial and real-world populations, they noted.

“Patients with newly diagnosed myeloma could benefit from levofloxacin prophylaxis, although local antibiotic resistance proportions must be considered,” the researchers cautioned.

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors reported financial affiliations with Actelion, Astellas, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and other companies.

SOURCE: Drayson MT et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct 23. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30506-6.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Sacubitril/valsartan suggests HFpEF benefit in neutral PARAGON-HF

PARIS – but that didn’t stop some experts from seeing a practice-changing message in its findings.

The results of PARAGON-HF, a major trial of sacubitril/valsartan – a compound already approved for treating heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction – in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), showed a statistically neutral result for the study’s primary endpoint, but with an excruciatingly close near miss for statistical significance and clear benefit in a subgroup of HFpEF patients with a modestly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. These findings seemed to convince some experts to soon try using sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) to treat selected patients with HFpEF, driven in large part by the lack of any other agent clearly proven to benefit the large number of patients with this form of heart failure.

HFpEF is “a huge unmet need,” and data from the PARAGON-HF trial “suggest that sacubitril/valsartan may be beneficial in some patients with HFpEF, particularly those with a left ventricular ejection fraction that is not frankly reduced, but less than normal,” specifically patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%-57%, Scott D. Solomon, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology as he reported the primary PARAGON-HF results.

“I’m not speaking for regulators or for guidelines, but I suspect that in this group of patients [with HFpEF and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%-57%] there is at least some rationale to use this treatment,” said Dr. Solomon, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of noninvasive cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

His suggestion, which cut against the standard rules that govern the interpretation of trial results, met a substantial level of receptivity at the congress.

Trial results “are not black and white, where a P value of .049 means the trial was totally positive, and a P of .051 means it’s totally neutral. That’s misleading, and it’s why the field is moving to different types of [statistical] analysis that give us more leeway in interpreting data,” commented Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

“Everything in this trial points to substantial potential benefit. I’m not impressed by the P value that just missed significance. I think this is a very important advance,” said Dr. Steg, who had no involvement in the study, during a press conference at the congress.

“I agree. I look at the totality of evidence, and to me the PARAGON-HF results were positive in patients with an ejection fraction of 50%, which is not a normal level. The way I interpret the results is, the treatment works in patients with an ejection fraction that is ‘lowish,’ but not at the conventional level of reduced ejection fraction,” commented Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who also had no involvement with PARAGON-HF.

Stuart J. Connolly, MD, designated discussant for the report at the congress and professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., struck similar notes during his discussion of the report, and called the subgroup analysis by baseline ejection fraction “compelling,” and supported by several secondary findings of the study, the biological plausibility of a link between ejection fraction and treatment response, and by suggestions of a similar effect caused by related drugs in prior studies.

The argument in favor of sacubitril/valsartan’s efficacy in a subgroup of PARAGON-HF patients was also taken up by Mariell Jessup, MD, a heart failure specialist and chief science and medical officer of the American Heart Association in Dallas. “I think it’s legitimate to say that there are HFpEF subgroups that might benefit” from sacubitril/valsartan, such as women. “I think it’s appropriate in this disease to look at subgroups because we have to find something that works for these patients,” she added in a video interview.

But Dr. Jessup also urged caution in interpreting the link between modestly reduced ejection fraction and response to sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF patients because ejection fraction measurements by echocardiography, as done in the trial, are notoriously unreliable. “We need more precise markers of who responds to this drug and who does not,” she said.

PARAGON-HF randomized 4,796 patients at 848 sites in 43 countries who were aged at least 50 years, had signs and symptoms of heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction of at least 45%, had evidence on echocardiography of either left atrial enlargement or left ventricular hypertrophy, and had an elevated blood level of natriuretic peptides.

The study’s primary endpoint was the composite rate of total (both first and recurrent) hospitalizations for heart failure and cardiovascular death. That outcome occurred at a rate of 12.8 events/100 patient-years in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan and a rate of 14.6 events/100 patient-years in control patients treated with the angiotensin receptor blocking drug valsartan alone. Those results yielded a relative risk reduction by sacubitril/valsartan of 13% with a P value of .059, just missing statistical significance. Concurrently with Dr. Solomon’s report the results appeared in an article online and then subsequently in print (N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 24;381[17]:1609-20). The primary endpoint was driven primarily by a 15% relative risk reduction in hospitalizations for heart failure; the two treatment arms showed nearly identical rates of cardiovascular disease death.

Notable secondary findings that reached statistical significance included a 16% relative decrease in total heart failure hospitalizations, cardiovascular deaths, and urgent heart failure visits with sacubitril/valsartan treatment, as well as a 16% reduction in all investigator-reported events. Other significant benefits linked with sacubitril/valsartan treatment were a 45% relative improvement in functional class, a 30% relative improvement in patients achieving a meaningful increase in a quality of life measure, and a halving of the incidence of worsening renal function with sacubitril/valsartan.

The safety profile of sacubitril/valsartan in the study matched previous reports on the drug in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, an approved indication since 2015.

The key subgroup analysis detailed by Dr. Solomon was the incidence of the primary endpoint by baseline ejection fraction. Among the 2,495 patients (52% of the study population) with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 57% or less when they entered the study, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan cut the primary endpoint incidence by 22%, compared with valsartan alone, a statistically significant difference. Among patients with a baseline ejection fraction of 58% or greater, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan had no effect on the primary endpoint, compared with control patients. Dr. Solomon also reported a statistically significant 22% relative improvement in the primary endpoint among the 2,479 women in the study (52% of the total study cohort) while the drug had no discernible impact among men, but he did not highlight any immediate implication of this finding.

Despite how suggestive the finding related to ejection fraction may be for practice, a major impediment to prescribing sacubitril/valsartan to HFpEF patients may come from pharmacy managers, suggested Douglas L. Mann, MD, a heart failure specialist and professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

“The study did not hit its primary endpoint, so pharmacy managers will face no moral issue by withholding the drug” from HFpEF patients, Dr. Mann said in an interview. Because sacubitril/valsartan is substantially costlier than other renin-angiotensin system inhibitor drugs, which are mostly generic, patients may often find it difficult to pay for sacubitril/valsartan themselves if it receives no insurance coverage.

“It’s heartbreaking that the endpoint missed for a disease with no proven treatment. The study may have narrowly missed, but it still missed, and a lot of us had hoped it would be positive. It’s a slippery slope” when investigators try to qualify a trial result that failed to meet the study’s prespecified definition of a statistically significant effect. “The primary endpoint is the primary endpoint, and we should not overinterpret the data,” Dr. Mann warned.

PARAGON-HF was sponsored by Novartis, which markets sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto). Dr. Solomon has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Novartis and from several other companies. Dr. Steg has received personal fees from Novartis and has received personal fees and research funding from several other companies. Dr. Bhatt has been a consultant to and received research funding from several companies but has had no recent relationship with Novartis. Dr. Connolly and Dr. Jessup had no disclosures. Dr. Mann has been a consultant to Novartis, as well as Bristol-Myers Squibb, LivaNova, and Tenaya Therapeutics.

PARAGON-HF was a well-designed and well-conducted trial that unfortunately showed a modest treatment effect, with sacubitril/valsartan treatment reducing the overall primary endpoint by 13%, compared with control patients, a difference that was not statistically significant. One factor to consider when interpreting this outcome was that the study used an active control arm in which patients received valsartan even though no treatment is specifically approved for or is considered to have proven efficacy in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The investigators felt compelled to use this active control because many patients with this form of heart failure receive a drug that inhibits the renin-angiotensin system. It’s possible that if sacubitril/valsartan had been compared with placebo the treatment effect would have been greater.

Although caution is required when interpreting subgroup outcomes in a study that lacks a positive primary endpoint, the data indicate a positive signal in the subgroup analysis that Dr. Solomon presented that took into account left ventricular ejection fraction at entry into the study. Patients with a baseline ejection fraction of 57% or less, roughly half the entire study group, showed a statistically significant benefit in a prespecified analysis, and a finding with some level of biological plausibility. This was a compelling analysis, and it suggested that with this treatment it may be possible to reduce a key outcome – the incidence of heart failure hospitalizations – in patients with modestly reduced ejection fractions.

Stuart J. Connolly, MD , is a professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as the designated discussant for PARAGON-HF.

PARAGON-HF was a well-designed and well-conducted trial that unfortunately showed a modest treatment effect, with sacubitril/valsartan treatment reducing the overall primary endpoint by 13%, compared with control patients, a difference that was not statistically significant. One factor to consider when interpreting this outcome was that the study used an active control arm in which patients received valsartan even though no treatment is specifically approved for or is considered to have proven efficacy in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The investigators felt compelled to use this active control because many patients with this form of heart failure receive a drug that inhibits the renin-angiotensin system. It’s possible that if sacubitril/valsartan had been compared with placebo the treatment effect would have been greater.

Although caution is required when interpreting subgroup outcomes in a study that lacks a positive primary endpoint, the data indicate a positive signal in the subgroup analysis that Dr. Solomon presented that took into account left ventricular ejection fraction at entry into the study. Patients with a baseline ejection fraction of 57% or less, roughly half the entire study group, showed a statistically significant benefit in a prespecified analysis, and a finding with some level of biological plausibility. This was a compelling analysis, and it suggested that with this treatment it may be possible to reduce a key outcome – the incidence of heart failure hospitalizations – in patients with modestly reduced ejection fractions.

Stuart J. Connolly, MD , is a professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as the designated discussant for PARAGON-HF.

PARAGON-HF was a well-designed and well-conducted trial that unfortunately showed a modest treatment effect, with sacubitril/valsartan treatment reducing the overall primary endpoint by 13%, compared with control patients, a difference that was not statistically significant. One factor to consider when interpreting this outcome was that the study used an active control arm in which patients received valsartan even though no treatment is specifically approved for or is considered to have proven efficacy in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The investigators felt compelled to use this active control because many patients with this form of heart failure receive a drug that inhibits the renin-angiotensin system. It’s possible that if sacubitril/valsartan had been compared with placebo the treatment effect would have been greater.

Although caution is required when interpreting subgroup outcomes in a study that lacks a positive primary endpoint, the data indicate a positive signal in the subgroup analysis that Dr. Solomon presented that took into account left ventricular ejection fraction at entry into the study. Patients with a baseline ejection fraction of 57% or less, roughly half the entire study group, showed a statistically significant benefit in a prespecified analysis, and a finding with some level of biological plausibility. This was a compelling analysis, and it suggested that with this treatment it may be possible to reduce a key outcome – the incidence of heart failure hospitalizations – in patients with modestly reduced ejection fractions.

Stuart J. Connolly, MD , is a professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as the designated discussant for PARAGON-HF.

PARIS – but that didn’t stop some experts from seeing a practice-changing message in its findings.

The results of PARAGON-HF, a major trial of sacubitril/valsartan – a compound already approved for treating heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction – in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), showed a statistically neutral result for the study’s primary endpoint, but with an excruciatingly close near miss for statistical significance and clear benefit in a subgroup of HFpEF patients with a modestly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. These findings seemed to convince some experts to soon try using sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) to treat selected patients with HFpEF, driven in large part by the lack of any other agent clearly proven to benefit the large number of patients with this form of heart failure.

HFpEF is “a huge unmet need,” and data from the PARAGON-HF trial “suggest that sacubitril/valsartan may be beneficial in some patients with HFpEF, particularly those with a left ventricular ejection fraction that is not frankly reduced, but less than normal,” specifically patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%-57%, Scott D. Solomon, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology as he reported the primary PARAGON-HF results.

“I’m not speaking for regulators or for guidelines, but I suspect that in this group of patients [with HFpEF and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%-57%] there is at least some rationale to use this treatment,” said Dr. Solomon, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of noninvasive cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

His suggestion, which cut against the standard rules that govern the interpretation of trial results, met a substantial level of receptivity at the congress.

Trial results “are not black and white, where a P value of .049 means the trial was totally positive, and a P of .051 means it’s totally neutral. That’s misleading, and it’s why the field is moving to different types of [statistical] analysis that give us more leeway in interpreting data,” commented Philippe Gabriel Steg, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

“Everything in this trial points to substantial potential benefit. I’m not impressed by the P value that just missed significance. I think this is a very important advance,” said Dr. Steg, who had no involvement in the study, during a press conference at the congress.