User login

House passes drug pricing bill, likely ending its journey

The House of Representatives passed a partisan drug pricing bill, a move that likely ends its legislative journey as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has already signaled he will not bring it to the Senate floor.

The Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3) passed Dec. 12 on a near party-line vote of 230-192, with two Republicans crossing the aisle to join the Democrats in support of the bill, and no Democrats voting against it. Four members from each party did not record votes.

“The American people are fed up with paying 3, 4, or 10 times more than people in other countries for the exact same drug,” House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone (D-N.J) said in a statement following the passage. “I’m proud that the House took decisive action today to finally level the playing field and provide real relief to the American people.”

H.R. 3 would give the secretary of Health and Human Services the ability to negotiate with drug manufacturers on the price of pharmaceuticals in Medicare Part D (and available in the commercial markets) using an international pricing benchmark and would penalize manufacturers who do not negotiate or fail to lower prices to be more in line with generally lower costs internationally.

Drug prices would need to be within 120% of the average price in a reference group of six nations: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Savings from the lower costs that result from negotiations would be reinvested into medical research.

Passage of H.R. 3 would “lower ... medication by 65%” per year for women with breast cancer, Rep. Haley Stevens (D-Mich.) said during the floor debate.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the drug price negotiation provision would lower spending on pharmaceuticals by $465 billion over the next 10 years, offset partially by an increase in spending by $358 billion associated with provisions to provide dental, vision, and hearing coverage.

The bill also includes mandatory rebates to the federal government when a drug’s price rises faster than the rate of inflation. It includes an annual cap on out-of-pocket spending on pharmaceuticals of $2,000 for Medicare Part D participants.

The bill was contentious from its introduction, which erased bipartisan work across the committees of jurisdiction, including a number of individual bills that passed at the committee level with bipartisan support.

The price negotiation scheme, using the international benchmark, was a key point of objection, which some argued was more akin to price-setting.

“Government price setting will kill innovation in clinical areas where it is most needed,” Rep. George Holding (R-N.C.) said during the floor debate. “The pricing scheme outlined in H.R. 3 would disincentivize research and development for drugs that are first in their class, such as the future cure for Alzheimer’s.”

The CBO estimates that if the bill were enacted, “8 fewer drugs would be introduced to the U.S. market over the 2020-2029 period, and about 30 fewer drugs over the subsequent decade.”

An amendment offered by House Energy and Commerce Committee Ranking Member Greg Walden (R-Ore.) attempted to replace the language of H.R. 3 with substitute language that collected all the individual drug pricing–related bills that had previously passed with bipartisan support at the committee level, but that was voted down by 223-201 vote with 12 members not voting.

Rep. Walden noted that policies within his substitute “unanimously passed the Energy and Commerce Committee earlier this year. They would have unanimously passed on this House floor had a poison pill not been put in up in the Rules Committee.”

Rep. Katie Porter (D-Calif.) countered that Rep. Walden’s amendment “doesn’t tackle the fundamental problem, which is reducing drug prices. This amendment fails to solve the main problem of actually lowering drug prices.”

The House of Representatives passed a partisan drug pricing bill, a move that likely ends its legislative journey as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has already signaled he will not bring it to the Senate floor.

The Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3) passed Dec. 12 on a near party-line vote of 230-192, with two Republicans crossing the aisle to join the Democrats in support of the bill, and no Democrats voting against it. Four members from each party did not record votes.

“The American people are fed up with paying 3, 4, or 10 times more than people in other countries for the exact same drug,” House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone (D-N.J) said in a statement following the passage. “I’m proud that the House took decisive action today to finally level the playing field and provide real relief to the American people.”

H.R. 3 would give the secretary of Health and Human Services the ability to negotiate with drug manufacturers on the price of pharmaceuticals in Medicare Part D (and available in the commercial markets) using an international pricing benchmark and would penalize manufacturers who do not negotiate or fail to lower prices to be more in line with generally lower costs internationally.

Drug prices would need to be within 120% of the average price in a reference group of six nations: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Savings from the lower costs that result from negotiations would be reinvested into medical research.

Passage of H.R. 3 would “lower ... medication by 65%” per year for women with breast cancer, Rep. Haley Stevens (D-Mich.) said during the floor debate.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the drug price negotiation provision would lower spending on pharmaceuticals by $465 billion over the next 10 years, offset partially by an increase in spending by $358 billion associated with provisions to provide dental, vision, and hearing coverage.

The bill also includes mandatory rebates to the federal government when a drug’s price rises faster than the rate of inflation. It includes an annual cap on out-of-pocket spending on pharmaceuticals of $2,000 for Medicare Part D participants.

The bill was contentious from its introduction, which erased bipartisan work across the committees of jurisdiction, including a number of individual bills that passed at the committee level with bipartisan support.

The price negotiation scheme, using the international benchmark, was a key point of objection, which some argued was more akin to price-setting.

“Government price setting will kill innovation in clinical areas where it is most needed,” Rep. George Holding (R-N.C.) said during the floor debate. “The pricing scheme outlined in H.R. 3 would disincentivize research and development for drugs that are first in their class, such as the future cure for Alzheimer’s.”

The CBO estimates that if the bill were enacted, “8 fewer drugs would be introduced to the U.S. market over the 2020-2029 period, and about 30 fewer drugs over the subsequent decade.”

An amendment offered by House Energy and Commerce Committee Ranking Member Greg Walden (R-Ore.) attempted to replace the language of H.R. 3 with substitute language that collected all the individual drug pricing–related bills that had previously passed with bipartisan support at the committee level, but that was voted down by 223-201 vote with 12 members not voting.

Rep. Walden noted that policies within his substitute “unanimously passed the Energy and Commerce Committee earlier this year. They would have unanimously passed on this House floor had a poison pill not been put in up in the Rules Committee.”

Rep. Katie Porter (D-Calif.) countered that Rep. Walden’s amendment “doesn’t tackle the fundamental problem, which is reducing drug prices. This amendment fails to solve the main problem of actually lowering drug prices.”

The House of Representatives passed a partisan drug pricing bill, a move that likely ends its legislative journey as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has already signaled he will not bring it to the Senate floor.

The Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3) passed Dec. 12 on a near party-line vote of 230-192, with two Republicans crossing the aisle to join the Democrats in support of the bill, and no Democrats voting against it. Four members from each party did not record votes.

“The American people are fed up with paying 3, 4, or 10 times more than people in other countries for the exact same drug,” House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone (D-N.J) said in a statement following the passage. “I’m proud that the House took decisive action today to finally level the playing field and provide real relief to the American people.”

H.R. 3 would give the secretary of Health and Human Services the ability to negotiate with drug manufacturers on the price of pharmaceuticals in Medicare Part D (and available in the commercial markets) using an international pricing benchmark and would penalize manufacturers who do not negotiate or fail to lower prices to be more in line with generally lower costs internationally.

Drug prices would need to be within 120% of the average price in a reference group of six nations: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Savings from the lower costs that result from negotiations would be reinvested into medical research.

Passage of H.R. 3 would “lower ... medication by 65%” per year for women with breast cancer, Rep. Haley Stevens (D-Mich.) said during the floor debate.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the drug price negotiation provision would lower spending on pharmaceuticals by $465 billion over the next 10 years, offset partially by an increase in spending by $358 billion associated with provisions to provide dental, vision, and hearing coverage.

The bill also includes mandatory rebates to the federal government when a drug’s price rises faster than the rate of inflation. It includes an annual cap on out-of-pocket spending on pharmaceuticals of $2,000 for Medicare Part D participants.

The bill was contentious from its introduction, which erased bipartisan work across the committees of jurisdiction, including a number of individual bills that passed at the committee level with bipartisan support.

The price negotiation scheme, using the international benchmark, was a key point of objection, which some argued was more akin to price-setting.

“Government price setting will kill innovation in clinical areas where it is most needed,” Rep. George Holding (R-N.C.) said during the floor debate. “The pricing scheme outlined in H.R. 3 would disincentivize research and development for drugs that are first in their class, such as the future cure for Alzheimer’s.”

The CBO estimates that if the bill were enacted, “8 fewer drugs would be introduced to the U.S. market over the 2020-2029 period, and about 30 fewer drugs over the subsequent decade.”

An amendment offered by House Energy and Commerce Committee Ranking Member Greg Walden (R-Ore.) attempted to replace the language of H.R. 3 with substitute language that collected all the individual drug pricing–related bills that had previously passed with bipartisan support at the committee level, but that was voted down by 223-201 vote with 12 members not voting.

Rep. Walden noted that policies within his substitute “unanimously passed the Energy and Commerce Committee earlier this year. They would have unanimously passed on this House floor had a poison pill not been put in up in the Rules Committee.”

Rep. Katie Porter (D-Calif.) countered that Rep. Walden’s amendment “doesn’t tackle the fundamental problem, which is reducing drug prices. This amendment fails to solve the main problem of actually lowering drug prices.”

CPT® and ICD-10 Coding for Endobronchial Valves

The FDA recently approved endobronchial valves for the bronchoscopic treatment of adult patients with hyperinflation associated with severe emphysema in regions of the lung that have little to no collateral ventilation. There are CPT® and ICD 10 codes that are appropriate to report these new services. CPT® codes typically are not product or device specific and the codes below apply to current and future FDA approved endobronchial valves with similar clinical indications and intent for the treatment of emphysema.

To be a candidate for the currently approved service, patients must have little to no collateral ventilation between the target and adjacent lobes. In some patients, this can be determined by a quantitative CT analysis service to assess emphysematous destruction and fissure completeness.

If the bronchial blocking technique shows evidence of collateral ventilation, the patient would be discharged without valve placement. In that scenario the appropriate CPT® code would be 31634:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

If the patient is determined not to have collateral ventilation, the valve procedure would proceed, followed by a minimum three-day inpatient stay to monitor for possible side effects.

The appropriate CPT codes for placing, and removing FDA approved valves are:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The table below identifies potential ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for emphysema. Applicability and usage of these codes may vary per case. Hospitals and physicians also should check and verify current policies and requirements with the payer for any patient who will be treated with endobronchial valves.

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The CHEST/ATS Clinical Practice Committee provided information for this article.

The FDA recently approved endobronchial valves for the bronchoscopic treatment of adult patients with hyperinflation associated with severe emphysema in regions of the lung that have little to no collateral ventilation. There are CPT® and ICD 10 codes that are appropriate to report these new services. CPT® codes typically are not product or device specific and the codes below apply to current and future FDA approved endobronchial valves with similar clinical indications and intent for the treatment of emphysema.

To be a candidate for the currently approved service, patients must have little to no collateral ventilation between the target and adjacent lobes. In some patients, this can be determined by a quantitative CT analysis service to assess emphysematous destruction and fissure completeness.

If the bronchial blocking technique shows evidence of collateral ventilation, the patient would be discharged without valve placement. In that scenario the appropriate CPT® code would be 31634:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

If the patient is determined not to have collateral ventilation, the valve procedure would proceed, followed by a minimum three-day inpatient stay to monitor for possible side effects.

The appropriate CPT codes for placing, and removing FDA approved valves are:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The table below identifies potential ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for emphysema. Applicability and usage of these codes may vary per case. Hospitals and physicians also should check and verify current policies and requirements with the payer for any patient who will be treated with endobronchial valves.

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The CHEST/ATS Clinical Practice Committee provided information for this article.

The FDA recently approved endobronchial valves for the bronchoscopic treatment of adult patients with hyperinflation associated with severe emphysema in regions of the lung that have little to no collateral ventilation. There are CPT® and ICD 10 codes that are appropriate to report these new services. CPT® codes typically are not product or device specific and the codes below apply to current and future FDA approved endobronchial valves with similar clinical indications and intent for the treatment of emphysema.

To be a candidate for the currently approved service, patients must have little to no collateral ventilation between the target and adjacent lobes. In some patients, this can be determined by a quantitative CT analysis service to assess emphysematous destruction and fissure completeness.

If the bronchial blocking technique shows evidence of collateral ventilation, the patient would be discharged without valve placement. In that scenario the appropriate CPT® code would be 31634:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

If the patient is determined not to have collateral ventilation, the valve procedure would proceed, followed by a minimum three-day inpatient stay to monitor for possible side effects.

The appropriate CPT codes for placing, and removing FDA approved valves are:

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The table below identifies potential ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for emphysema. Applicability and usage of these codes may vary per case. Hospitals and physicians also should check and verify current policies and requirements with the payer for any patient who will be treated with endobronchial valves.

INSERT GRAPHIC HERE

The CHEST/ATS Clinical Practice Committee provided information for this article.

Icosapent ethyl approved for cardiovascular risk reduction

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) has gained an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for reduction of cardiovascular events in patients with high triglycerides who are at high risk for cardiovascular events.

as an add-on to maximally tolerated statin therapy,” the agency said in an announcement.

The decision, announced on Dec. 13, was based primarily on results of REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl-Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. It showed that patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

In a November meeting, the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted unanimously for approval.

The agency notes that, in clinical trials, icosapent ethyl was linked to an increased risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring hospitalization, especially in patients with a history of either condition. The highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid was also associated with an increased risk of bleeding events, particularly in those taking blood-thinning drugs that increase the risk of bleeding, such as aspirin, clopidogrel, or warfarin.

The most common side effects reported in the clinical trials for icosapent ethyl were musculoskeletal pain, peripheral edema, atrial fibrillation, and arthralgia.

The complete indication is “as an adjunct to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and unstable angina requiring hospitalization in adult patients with elevated triglyceride levels (at least 150 mg/dL) and established cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus and two or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease,” according to a statement from Amalin, which markets Vascepa.

The drug was approved in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) has gained an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for reduction of cardiovascular events in patients with high triglycerides who are at high risk for cardiovascular events.

as an add-on to maximally tolerated statin therapy,” the agency said in an announcement.

The decision, announced on Dec. 13, was based primarily on results of REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl-Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. It showed that patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

In a November meeting, the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted unanimously for approval.

The agency notes that, in clinical trials, icosapent ethyl was linked to an increased risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring hospitalization, especially in patients with a history of either condition. The highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid was also associated with an increased risk of bleeding events, particularly in those taking blood-thinning drugs that increase the risk of bleeding, such as aspirin, clopidogrel, or warfarin.

The most common side effects reported in the clinical trials for icosapent ethyl were musculoskeletal pain, peripheral edema, atrial fibrillation, and arthralgia.

The complete indication is “as an adjunct to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and unstable angina requiring hospitalization in adult patients with elevated triglyceride levels (at least 150 mg/dL) and established cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus and two or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease,” according to a statement from Amalin, which markets Vascepa.

The drug was approved in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

Icosapent ethyl (Vascepa) has gained an indication from the Food and Drug Administration for reduction of cardiovascular events in patients with high triglycerides who are at high risk for cardiovascular events.

as an add-on to maximally tolerated statin therapy,” the agency said in an announcement.

The decision, announced on Dec. 13, was based primarily on results of REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl-Intervention Trial), which tested icosapent ethyl in 8,179 patients with either established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor. It showed that patients who received icosapent ethyl had a statistically significant 25% relative risk reduction in the trial’s primary, composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 3;380[1]:11-22).

In a November meeting, the FDA’s Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee voted unanimously for approval.

The agency notes that, in clinical trials, icosapent ethyl was linked to an increased risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring hospitalization, especially in patients with a history of either condition. The highly purified form of the ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid was also associated with an increased risk of bleeding events, particularly in those taking blood-thinning drugs that increase the risk of bleeding, such as aspirin, clopidogrel, or warfarin.

The most common side effects reported in the clinical trials for icosapent ethyl were musculoskeletal pain, peripheral edema, atrial fibrillation, and arthralgia.

The complete indication is “as an adjunct to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and unstable angina requiring hospitalization in adult patients with elevated triglyceride levels (at least 150 mg/dL) and established cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus and two or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease,” according to a statement from Amalin, which markets Vascepa.

The drug was approved in 2012 for the indication of cutting triglyceride levels once they reached at least 500 mg/dL.

Medtwitter embraces incoming student’s excitement

When Melissa Gonzalez excitedly tweeted that she had been accepted to medical school earlier this year, she had no idea the tweet would draw attention and responses from people across the country.

The tweet, which shared that Ms. Gonzalez was the daughter of Mexican immigrants, received more than 300,000 likes and another 23,000 retweets from physicians, medical associations, students, and graduates alike. In this video, Ms. Gonzalez, who was accepted to Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, speaks of her journey to medical school.

When Melissa Gonzalez excitedly tweeted that she had been accepted to medical school earlier this year, she had no idea the tweet would draw attention and responses from people across the country.

The tweet, which shared that Ms. Gonzalez was the daughter of Mexican immigrants, received more than 300,000 likes and another 23,000 retweets from physicians, medical associations, students, and graduates alike. In this video, Ms. Gonzalez, who was accepted to Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, speaks of her journey to medical school.

When Melissa Gonzalez excitedly tweeted that she had been accepted to medical school earlier this year, she had no idea the tweet would draw attention and responses from people across the country.

The tweet, which shared that Ms. Gonzalez was the daughter of Mexican immigrants, received more than 300,000 likes and another 23,000 retweets from physicians, medical associations, students, and graduates alike. In this video, Ms. Gonzalez, who was accepted to Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, speaks of her journey to medical school.

Clinic goes to bat for bullied kids

NEW ORLEANS – After Massachusetts passed antibullying legislation in 2009, Peter C. Raffalli, MD, saw an opportunity to improve care for the increasing numbers of children presenting to his neurology practice at Boston Children’s Hospital who were victims of bullying – especially those with developmental disabilities.

“I had been thinking of a clinic to help kids with these issues, aside from just helping them deal with the fallout: the depression, anxiety, et cetera, that comes with being bullied,” Dr. Raffalli recalled at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “I wanted to do something to help present to families the evidence-based strategies regarding bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that might help to stop the bullying.”

This led him to launch the Bullying and Cyberbullying Prevention and Advocacy Collaborative (BACPAC) at Boston Children’s Hospital, which began in 2009 as an educational resource for families, medical colleagues, and schools. Dr. Raffalli also formed an alliance with the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University (Ann Neurol. 2016;79[2]:167-8).

Two years later in 2011, BACPAC became a formal clinic at Boston Children’s that serves as a subspecialty consult service for victims of bullying and their families. The clinic team consists of a child neurologist, a social worker, and an education resource specialist who meet with the bullying victim and his/her family in initial consultation for 90 minutes. The goal is to develop an evidence-based plan for bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that is individualized to the patient’s developmental and social needs.

“We tell families that bullying is recognized medically and legally as a form of abuse,” said Dr. Raffalli. “The medical and psychological consequences are similar to other forms of abuse. You’d be surprised how often patients do think the bullying is their fault.”

The extent of the problem

Researchers estimate that 25%-30% of children will experience some form of bullying between kindergarten and grade 12, and about 8% will engage in bullying themselves. When BACPAC began in 2009, Dr. Raffalli conducted an informal search of peer-reviewed literature on bullying in children with special needs; it yielded just four articles. “Since then, there’s been an exponential explosion of literature on various aspects of bullying,” he said. Now there is ample evidence in the peer-reviewed literature to show the increased risk for bullying/cyberbullying in children/teens, not just with neurodevelopmental disorders, but also for kids with other medical disorders such as obesity, asthma, and allergies.

“We’ve had a good number of kids over the years with peanut allergy who were literally threatened physically with peanut butter at school,” he said. “It’s incredible how callous some kids can be. Kids with oppositional defiant disorder, impulse control disorder, and callous/unemotional traits from a psychological standpoint are hardest to reach when it comes to getting them to stop bullying. You’d be surprised how frequently bullies use the phrase [to their victims], ‘You should kill yourself.’ They don’t realize the damage they’re doing to people. Bullying can lead to severe psychological but also long-term medical problems, including suicidal ideation.”

Published studies show that the highest incidences of bullying occur in children with neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD, autistic spectrum disorders, Tourette syndrome, and other learning disabilities (Eur J Spec Needs Ed. 2010;25[1]:77-91). This population of children is overrepresented in bullying “because the services they receive at school make their disabilities more visible,” explained Dr. Raffalli, who is also an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They stand out, and they have social information–processing deficits or distortions that exacerbate bullying involvement. They also have difficulty interpreting social cues or attributing hostile characteristics to their peer’s behavior.”

The consequences of bullying

The psychological and educational consequences of bullying among children in general include being more likely to develop depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, alcohol and drug abuse, sleeping difficulties, self-harm, and suicidal ideation and attempts. “We’re social creatures, and when we don’t have those social connections, we get very depressed.”

Bullying victims also are more likely to develop school avoidance and absence, decreased school performance, poor concentration, high anxiety, and social withdrawal – all of which limit their opportunities to learn. “The No. 1 thing you can do to help these kids is to believe their story – to explain to them that it’s not their fault, and to explain that you are there for them and that you support them,” he said. “When a kid gets the feeling that someone is willing to listen to them and believe them, it does an enormous good for their emotional state.”

Dr. Raffalli added that a toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity – such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship – without adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment well into the adult years.

In the Harvard Review of Psychiatry, researchers set out to investigate what’s known about the long-term health effects of childhood bullying. They found that bullying can induce “aspects of the stress response, via epigenetic, inflammatory, and metabolic mediators [that] have the capacity to compromise mental and physical health, and to increase the risk of disease.” The researchers advised clinicians who care for children to assess the mental and physical health effects of bullying (Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25[2]:89-95).

Additional vulnerabilities for bullying victims include parents and children whose primary language is not English, as well as parents with mental illness or substance abuse and families living in poverty. “We have to keep in mind how much additional stress they may be dealing with. This can make it harder for them to cope. Bullies also are shown to be at higher risk for psychological and legal trouble into adulthood, so we should be trying to help them too. We have to keep in mind that these are all developing kids.”

Cyberbullying

In Dr. Raffalli’s clinical experience, cyberbullying has become the bully’s weapon of choice. “I call it the stealth bomber of bullying,” he said. “Cyberbullying can start as early as the second or third grade. Most parents are not giving phones to second-graders. I’m worried that it’s going to get worse, though, with the excuse that ‘I feel safer if they have a cell phone so they can call me.’ I tell parents that they still make flip phones. You don’t have to get a smartphone for a second- or third-grader, or even for a sixth-grader.”

By the time kids reach fourth and fifth grade, he continued, they begin to form their opinion “about what they believe is cool and not cool, and they begin to get into cliques that have similar beliefs, and support each other, and may break off from old friends.” He added that, while adult predation “makes the news and is certainly something we should all be concerned about, the incidence of being harassed and bullied by someone in your own age group at school is actually much higher and still has serious outcomes, including the possibility of death.”

The Massachusetts antibullying law stipulates that all teachers and all school personnel have to participate in mandatory bullying training. Schools also are required to draft and follow a bullying investigative protocol.

“Apparently the schools have all done this, yet the number of times that schools use interventions that are not advisable, such as mediation, is incredible to me,” Dr. Raffalli said. “Bringing the bully and the victim together for a ‘cup of coffee and a handshake’ is not advisable. Mediation has been shown in a number of studies to be detrimental in bullying situations. Things can easily get worse.”

Often, family members who bring their child to the BACPAC “feel that their child’s school is not helping them,” he said. “We should try to figure out why those schools are having such a hard time and see if we can help them.”

Dr. Raffalli reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – After Massachusetts passed antibullying legislation in 2009, Peter C. Raffalli, MD, saw an opportunity to improve care for the increasing numbers of children presenting to his neurology practice at Boston Children’s Hospital who were victims of bullying – especially those with developmental disabilities.

“I had been thinking of a clinic to help kids with these issues, aside from just helping them deal with the fallout: the depression, anxiety, et cetera, that comes with being bullied,” Dr. Raffalli recalled at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “I wanted to do something to help present to families the evidence-based strategies regarding bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that might help to stop the bullying.”

This led him to launch the Bullying and Cyberbullying Prevention and Advocacy Collaborative (BACPAC) at Boston Children’s Hospital, which began in 2009 as an educational resource for families, medical colleagues, and schools. Dr. Raffalli also formed an alliance with the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University (Ann Neurol. 2016;79[2]:167-8).

Two years later in 2011, BACPAC became a formal clinic at Boston Children’s that serves as a subspecialty consult service for victims of bullying and their families. The clinic team consists of a child neurologist, a social worker, and an education resource specialist who meet with the bullying victim and his/her family in initial consultation for 90 minutes. The goal is to develop an evidence-based plan for bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that is individualized to the patient’s developmental and social needs.

“We tell families that bullying is recognized medically and legally as a form of abuse,” said Dr. Raffalli. “The medical and psychological consequences are similar to other forms of abuse. You’d be surprised how often patients do think the bullying is their fault.”

The extent of the problem

Researchers estimate that 25%-30% of children will experience some form of bullying between kindergarten and grade 12, and about 8% will engage in bullying themselves. When BACPAC began in 2009, Dr. Raffalli conducted an informal search of peer-reviewed literature on bullying in children with special needs; it yielded just four articles. “Since then, there’s been an exponential explosion of literature on various aspects of bullying,” he said. Now there is ample evidence in the peer-reviewed literature to show the increased risk for bullying/cyberbullying in children/teens, not just with neurodevelopmental disorders, but also for kids with other medical disorders such as obesity, asthma, and allergies.

“We’ve had a good number of kids over the years with peanut allergy who were literally threatened physically with peanut butter at school,” he said. “It’s incredible how callous some kids can be. Kids with oppositional defiant disorder, impulse control disorder, and callous/unemotional traits from a psychological standpoint are hardest to reach when it comes to getting them to stop bullying. You’d be surprised how frequently bullies use the phrase [to their victims], ‘You should kill yourself.’ They don’t realize the damage they’re doing to people. Bullying can lead to severe psychological but also long-term medical problems, including suicidal ideation.”

Published studies show that the highest incidences of bullying occur in children with neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD, autistic spectrum disorders, Tourette syndrome, and other learning disabilities (Eur J Spec Needs Ed. 2010;25[1]:77-91). This population of children is overrepresented in bullying “because the services they receive at school make their disabilities more visible,” explained Dr. Raffalli, who is also an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They stand out, and they have social information–processing deficits or distortions that exacerbate bullying involvement. They also have difficulty interpreting social cues or attributing hostile characteristics to their peer’s behavior.”

The consequences of bullying

The psychological and educational consequences of bullying among children in general include being more likely to develop depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, alcohol and drug abuse, sleeping difficulties, self-harm, and suicidal ideation and attempts. “We’re social creatures, and when we don’t have those social connections, we get very depressed.”

Bullying victims also are more likely to develop school avoidance and absence, decreased school performance, poor concentration, high anxiety, and social withdrawal – all of which limit their opportunities to learn. “The No. 1 thing you can do to help these kids is to believe their story – to explain to them that it’s not their fault, and to explain that you are there for them and that you support them,” he said. “When a kid gets the feeling that someone is willing to listen to them and believe them, it does an enormous good for their emotional state.”

Dr. Raffalli added that a toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity – such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship – without adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment well into the adult years.

In the Harvard Review of Psychiatry, researchers set out to investigate what’s known about the long-term health effects of childhood bullying. They found that bullying can induce “aspects of the stress response, via epigenetic, inflammatory, and metabolic mediators [that] have the capacity to compromise mental and physical health, and to increase the risk of disease.” The researchers advised clinicians who care for children to assess the mental and physical health effects of bullying (Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25[2]:89-95).

Additional vulnerabilities for bullying victims include parents and children whose primary language is not English, as well as parents with mental illness or substance abuse and families living in poverty. “We have to keep in mind how much additional stress they may be dealing with. This can make it harder for them to cope. Bullies also are shown to be at higher risk for psychological and legal trouble into adulthood, so we should be trying to help them too. We have to keep in mind that these are all developing kids.”

Cyberbullying

In Dr. Raffalli’s clinical experience, cyberbullying has become the bully’s weapon of choice. “I call it the stealth bomber of bullying,” he said. “Cyberbullying can start as early as the second or third grade. Most parents are not giving phones to second-graders. I’m worried that it’s going to get worse, though, with the excuse that ‘I feel safer if they have a cell phone so they can call me.’ I tell parents that they still make flip phones. You don’t have to get a smartphone for a second- or third-grader, or even for a sixth-grader.”

By the time kids reach fourth and fifth grade, he continued, they begin to form their opinion “about what they believe is cool and not cool, and they begin to get into cliques that have similar beliefs, and support each other, and may break off from old friends.” He added that, while adult predation “makes the news and is certainly something we should all be concerned about, the incidence of being harassed and bullied by someone in your own age group at school is actually much higher and still has serious outcomes, including the possibility of death.”

The Massachusetts antibullying law stipulates that all teachers and all school personnel have to participate in mandatory bullying training. Schools also are required to draft and follow a bullying investigative protocol.

“Apparently the schools have all done this, yet the number of times that schools use interventions that are not advisable, such as mediation, is incredible to me,” Dr. Raffalli said. “Bringing the bully and the victim together for a ‘cup of coffee and a handshake’ is not advisable. Mediation has been shown in a number of studies to be detrimental in bullying situations. Things can easily get worse.”

Often, family members who bring their child to the BACPAC “feel that their child’s school is not helping them,” he said. “We should try to figure out why those schools are having such a hard time and see if we can help them.”

Dr. Raffalli reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – After Massachusetts passed antibullying legislation in 2009, Peter C. Raffalli, MD, saw an opportunity to improve care for the increasing numbers of children presenting to his neurology practice at Boston Children’s Hospital who were victims of bullying – especially those with developmental disabilities.

“I had been thinking of a clinic to help kids with these issues, aside from just helping them deal with the fallout: the depression, anxiety, et cetera, that comes with being bullied,” Dr. Raffalli recalled at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “I wanted to do something to help present to families the evidence-based strategies regarding bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that might help to stop the bullying.”

This led him to launch the Bullying and Cyberbullying Prevention and Advocacy Collaborative (BACPAC) at Boston Children’s Hospital, which began in 2009 as an educational resource for families, medical colleagues, and schools. Dr. Raffalli also formed an alliance with the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University (Ann Neurol. 2016;79[2]:167-8).

Two years later in 2011, BACPAC became a formal clinic at Boston Children’s that serves as a subspecialty consult service for victims of bullying and their families. The clinic team consists of a child neurologist, a social worker, and an education resource specialist who meet with the bullying victim and his/her family in initial consultation for 90 minutes. The goal is to develop an evidence-based plan for bullying prevention, detection, and intervention that is individualized to the patient’s developmental and social needs.

“We tell families that bullying is recognized medically and legally as a form of abuse,” said Dr. Raffalli. “The medical and psychological consequences are similar to other forms of abuse. You’d be surprised how often patients do think the bullying is their fault.”

The extent of the problem

Researchers estimate that 25%-30% of children will experience some form of bullying between kindergarten and grade 12, and about 8% will engage in bullying themselves. When BACPAC began in 2009, Dr. Raffalli conducted an informal search of peer-reviewed literature on bullying in children with special needs; it yielded just four articles. “Since then, there’s been an exponential explosion of literature on various aspects of bullying,” he said. Now there is ample evidence in the peer-reviewed literature to show the increased risk for bullying/cyberbullying in children/teens, not just with neurodevelopmental disorders, but also for kids with other medical disorders such as obesity, asthma, and allergies.

“We’ve had a good number of kids over the years with peanut allergy who were literally threatened physically with peanut butter at school,” he said. “It’s incredible how callous some kids can be. Kids with oppositional defiant disorder, impulse control disorder, and callous/unemotional traits from a psychological standpoint are hardest to reach when it comes to getting them to stop bullying. You’d be surprised how frequently bullies use the phrase [to their victims], ‘You should kill yourself.’ They don’t realize the damage they’re doing to people. Bullying can lead to severe psychological but also long-term medical problems, including suicidal ideation.”

Published studies show that the highest incidences of bullying occur in children with neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD, autistic spectrum disorders, Tourette syndrome, and other learning disabilities (Eur J Spec Needs Ed. 2010;25[1]:77-91). This population of children is overrepresented in bullying “because the services they receive at school make their disabilities more visible,” explained Dr. Raffalli, who is also an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They stand out, and they have social information–processing deficits or distortions that exacerbate bullying involvement. They also have difficulty interpreting social cues or attributing hostile characteristics to their peer’s behavior.”

The consequences of bullying

The psychological and educational consequences of bullying among children in general include being more likely to develop depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, alcohol and drug abuse, sleeping difficulties, self-harm, and suicidal ideation and attempts. “We’re social creatures, and when we don’t have those social connections, we get very depressed.”

Bullying victims also are more likely to develop school avoidance and absence, decreased school performance, poor concentration, high anxiety, and social withdrawal – all of which limit their opportunities to learn. “The No. 1 thing you can do to help these kids is to believe their story – to explain to them that it’s not their fault, and to explain that you are there for them and that you support them,” he said. “When a kid gets the feeling that someone is willing to listen to them and believe them, it does an enormous good for their emotional state.”

Dr. Raffalli added that a toxic stress response can occur when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity – such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, exposure to violence, and/or the accumulated burdens of family economic hardship – without adequate adult support. This kind of prolonged activation of the stress response systems can disrupt the development of brain architecture and other organ systems, and increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment well into the adult years.

In the Harvard Review of Psychiatry, researchers set out to investigate what’s known about the long-term health effects of childhood bullying. They found that bullying can induce “aspects of the stress response, via epigenetic, inflammatory, and metabolic mediators [that] have the capacity to compromise mental and physical health, and to increase the risk of disease.” The researchers advised clinicians who care for children to assess the mental and physical health effects of bullying (Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25[2]:89-95).

Additional vulnerabilities for bullying victims include parents and children whose primary language is not English, as well as parents with mental illness or substance abuse and families living in poverty. “We have to keep in mind how much additional stress they may be dealing with. This can make it harder for them to cope. Bullies also are shown to be at higher risk for psychological and legal trouble into adulthood, so we should be trying to help them too. We have to keep in mind that these are all developing kids.”

Cyberbullying

In Dr. Raffalli’s clinical experience, cyberbullying has become the bully’s weapon of choice. “I call it the stealth bomber of bullying,” he said. “Cyberbullying can start as early as the second or third grade. Most parents are not giving phones to second-graders. I’m worried that it’s going to get worse, though, with the excuse that ‘I feel safer if they have a cell phone so they can call me.’ I tell parents that they still make flip phones. You don’t have to get a smartphone for a second- or third-grader, or even for a sixth-grader.”

By the time kids reach fourth and fifth grade, he continued, they begin to form their opinion “about what they believe is cool and not cool, and they begin to get into cliques that have similar beliefs, and support each other, and may break off from old friends.” He added that, while adult predation “makes the news and is certainly something we should all be concerned about, the incidence of being harassed and bullied by someone in your own age group at school is actually much higher and still has serious outcomes, including the possibility of death.”

The Massachusetts antibullying law stipulates that all teachers and all school personnel have to participate in mandatory bullying training. Schools also are required to draft and follow a bullying investigative protocol.

“Apparently the schools have all done this, yet the number of times that schools use interventions that are not advisable, such as mediation, is incredible to me,” Dr. Raffalli said. “Bringing the bully and the victim together for a ‘cup of coffee and a handshake’ is not advisable. Mediation has been shown in a number of studies to be detrimental in bullying situations. Things can easily get worse.”

Often, family members who bring their child to the BACPAC “feel that their child’s school is not helping them,” he said. “We should try to figure out why those schools are having such a hard time and see if we can help them.”

Dr. Raffalli reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2019

Flu activity dropped in early December

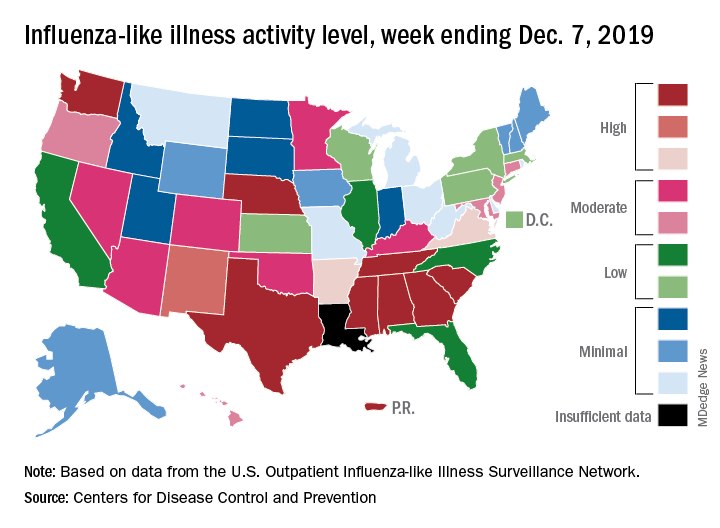

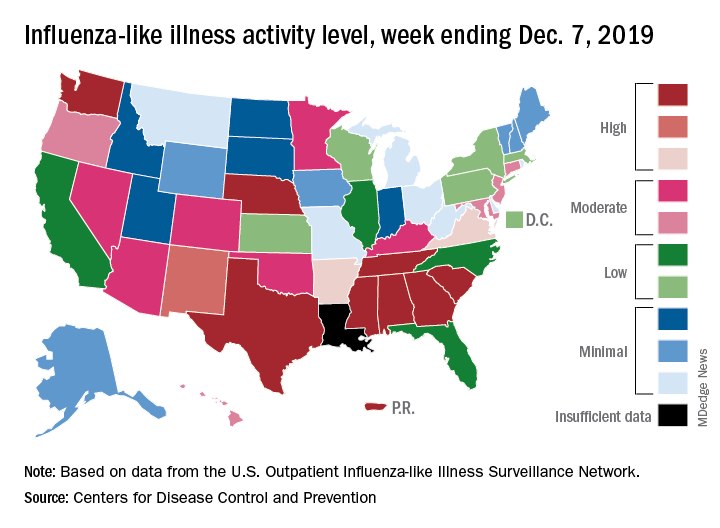

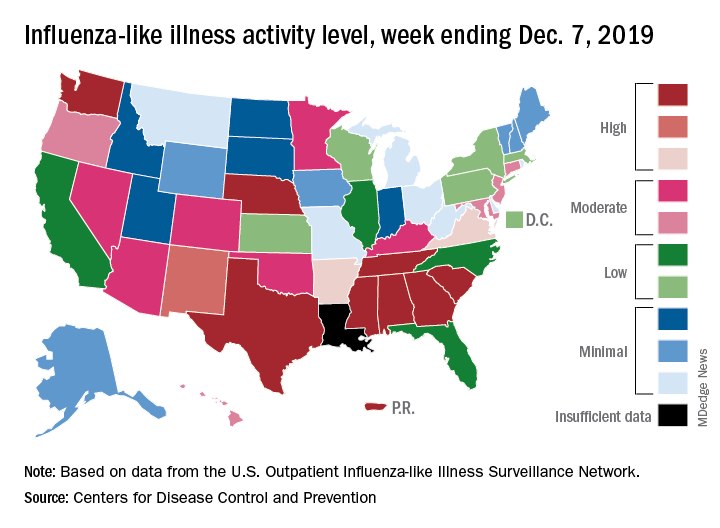

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 3.2% of outpatient visits were for influenza-like illness (ILI) during the week of Dec. 1-7, the CDC reported. That is down from 3.4% the week before, which was the highest November rate in 10 years. The national baseline rate is 2.4%, and the current 3.2% marks the fifth consecutive week that the outpatient ILI rate has been at or above the baseline level, the CDC report noted.

The drop in activity “may be influenced in part by a reduction in routine healthcare visits surrounding the Thanksgiving holiday. … as has occurred during previous seasons,” the CDC influenza division said Dec. 13 in its weekly flu report.

The early spike in “activity is being caused mostly by influenza B/Victoria viruses, which is unusual for this time of year,” the report said. Since the beginning of the 2019-2020 season a little over 2 months ago, almost 70% of specimens that have been positive for influenza have been identified as type B.

The nationwide decline in activity doesn’t, however, show up at the state level. For the week ending Dec. 7, there were eight states along with Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of flu activity, as there were the previous week. Washington state moved up from 9 to 10, but Louisiana, which was at level 10 last week, had insufficient data to be included this week, the CDC data show.

There were four flu-related pediatric deaths reported to the CDC during the week ending Dec. 7, all occurring in previous weeks, which brings the total to 10 for the season. In 2018-2019, there were 143 pediatric deaths caused by influenza, the CDC said.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 3.2% of outpatient visits were for influenza-like illness (ILI) during the week of Dec. 1-7, the CDC reported. That is down from 3.4% the week before, which was the highest November rate in 10 years. The national baseline rate is 2.4%, and the current 3.2% marks the fifth consecutive week that the outpatient ILI rate has been at or above the baseline level, the CDC report noted.

The drop in activity “may be influenced in part by a reduction in routine healthcare visits surrounding the Thanksgiving holiday. … as has occurred during previous seasons,” the CDC influenza division said Dec. 13 in its weekly flu report.

The early spike in “activity is being caused mostly by influenza B/Victoria viruses, which is unusual for this time of year,” the report said. Since the beginning of the 2019-2020 season a little over 2 months ago, almost 70% of specimens that have been positive for influenza have been identified as type B.

The nationwide decline in activity doesn’t, however, show up at the state level. For the week ending Dec. 7, there were eight states along with Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of flu activity, as there were the previous week. Washington state moved up from 9 to 10, but Louisiana, which was at level 10 last week, had insufficient data to be included this week, the CDC data show.

There were four flu-related pediatric deaths reported to the CDC during the week ending Dec. 7, all occurring in previous weeks, which brings the total to 10 for the season. In 2018-2019, there were 143 pediatric deaths caused by influenza, the CDC said.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 3.2% of outpatient visits were for influenza-like illness (ILI) during the week of Dec. 1-7, the CDC reported. That is down from 3.4% the week before, which was the highest November rate in 10 years. The national baseline rate is 2.4%, and the current 3.2% marks the fifth consecutive week that the outpatient ILI rate has been at or above the baseline level, the CDC report noted.

The drop in activity “may be influenced in part by a reduction in routine healthcare visits surrounding the Thanksgiving holiday. … as has occurred during previous seasons,” the CDC influenza division said Dec. 13 in its weekly flu report.

The early spike in “activity is being caused mostly by influenza B/Victoria viruses, which is unusual for this time of year,” the report said. Since the beginning of the 2019-2020 season a little over 2 months ago, almost 70% of specimens that have been positive for influenza have been identified as type B.

The nationwide decline in activity doesn’t, however, show up at the state level. For the week ending Dec. 7, there were eight states along with Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of flu activity, as there were the previous week. Washington state moved up from 9 to 10, but Louisiana, which was at level 10 last week, had insufficient data to be included this week, the CDC data show.

There were four flu-related pediatric deaths reported to the CDC during the week ending Dec. 7, all occurring in previous weeks, which brings the total to 10 for the season. In 2018-2019, there were 143 pediatric deaths caused by influenza, the CDC said.

FDA authorizes customizable automated glycemic controller

The Food and Drug Administration has authorized marketing of the Tandem Diabetes Care Control-IQ Technology, an interoperable automated glycemic controller, for use in a customizable glucose control system, according to a release from the agency.

The move also paves the way for the review and authorization of similar devices in the future.

The Control-IQ Technology controller coordinates with an alternate controller-enabled insulin pump and an integrated continuous glucose monitor, which can be made by other manufacturers as long they are compatible with this modular technology.

The agency reviewed data from a clinical study of 168 patients with type 1 diabetes who were randomized to use either the Control-IQ Technology controller installed on a Tandem t:slim X2 insulin pump, or a continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump without the Control-IQ controller. The findings showed that,

However, the agency noted that, although the system has been assessed for reliability, delays in insulin delivery remain possible and care should be taken when using it.

This authorization comes along with establishment of criteria and regulatory requirements that create a new regulatory classification for this type of device, whereby future devices of the same type and with the same purpose can go through the FDA’s 510(k) premarket process. Such a process would mean that, going forward, similar devices can “obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a predicate device.”

More information can be found in the full release, available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has authorized marketing of the Tandem Diabetes Care Control-IQ Technology, an interoperable automated glycemic controller, for use in a customizable glucose control system, according to a release from the agency.

The move also paves the way for the review and authorization of similar devices in the future.

The Control-IQ Technology controller coordinates with an alternate controller-enabled insulin pump and an integrated continuous glucose monitor, which can be made by other manufacturers as long they are compatible with this modular technology.

The agency reviewed data from a clinical study of 168 patients with type 1 diabetes who were randomized to use either the Control-IQ Technology controller installed on a Tandem t:slim X2 insulin pump, or a continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump without the Control-IQ controller. The findings showed that,

However, the agency noted that, although the system has been assessed for reliability, delays in insulin delivery remain possible and care should be taken when using it.

This authorization comes along with establishment of criteria and regulatory requirements that create a new regulatory classification for this type of device, whereby future devices of the same type and with the same purpose can go through the FDA’s 510(k) premarket process. Such a process would mean that, going forward, similar devices can “obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a predicate device.”

More information can be found in the full release, available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has authorized marketing of the Tandem Diabetes Care Control-IQ Technology, an interoperable automated glycemic controller, for use in a customizable glucose control system, according to a release from the agency.

The move also paves the way for the review and authorization of similar devices in the future.

The Control-IQ Technology controller coordinates with an alternate controller-enabled insulin pump and an integrated continuous glucose monitor, which can be made by other manufacturers as long they are compatible with this modular technology.

The agency reviewed data from a clinical study of 168 patients with type 1 diabetes who were randomized to use either the Control-IQ Technology controller installed on a Tandem t:slim X2 insulin pump, or a continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump without the Control-IQ controller. The findings showed that,

However, the agency noted that, although the system has been assessed for reliability, delays in insulin delivery remain possible and care should be taken when using it.

This authorization comes along with establishment of criteria and regulatory requirements that create a new regulatory classification for this type of device, whereby future devices of the same type and with the same purpose can go through the FDA’s 510(k) premarket process. Such a process would mean that, going forward, similar devices can “obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a predicate device.”

More information can be found in the full release, available on the FDA website.

ASH releases guidelines on managing cardiopulmonary and kidney disease in SCD

ORLANDO – It is good practice to consult with a pulmonary hypertension (PH) expert before referring a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD) for right-heart catheterization or PH evaluation, according to new American Society of Hematology guidelines for the screening and management of cardiopulmonary and kidney disease in patients with SCD.

That “Good Practice” recommendation is one of several included in the evidence-based guidelines published Dec. 10 in Blood Advances and highlighted during a Special Education Session at the annual ASH meeting.

The guidelines provide 10 main recommendations intended to “support patients, clinicians, and other health care professionals in their decisions about screening, diagnosis, and management of cardiopulmonary and renal complications of SCD,” wrote Robert I. Liem, MD, of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and colleagues.

The recommendations, agreed upon by a multidisciplinary guideline panel, relate to screening, diagnosis, and management of PH, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), hypertension, proteinuria and chronic kidney disease, and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Most are “conditional,” as opposed to “strong,” because of a paucity of direct, high-quality outcomes data, and they are accompanied by the Good Practice Statements, descriptive remarks and caveats based on the available data, as well as suggestions for future research.

At the special ASH session, Ankit A. Desai, MD, highlighted some of the recommendations and discussed considerations for their practical application.

The Good Practice Statement on consulting a specialist before referring a patient for PH relates specifically to Recommendations 2a and 2b on the management of abnormal echocardiography, explained Dr. Desai of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

For asymptomatic children and adults with SCD and an isolated peak tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRJV) of at least 2.5-2.9 m/s on echocardiography, the panel recommends against right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2a, conditional), he said.

For children and adults with SCD and a peak TRJV of at least 2.5 m/s who also have a reduced 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and/or elevated N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), the panel supports right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2b, conditional).

Dr. Desai noted that the 2.5 m/s threshold was found to be suboptimal when used as the sole criteria for right-heart catheterization. Using that threshold alone is associated with “moderate to large” harms, such as starting inappropriate PH-specific therapies and/or performing unnecessary right-heart catheterization. However, when used in combination with 6MWD, the predictive capacity improved significantly, and the risk for potential harm was low, he explained.

Another Good Practice Statement included in the guidelines, and relevant to these recommendations on managing abnormal echocardiography, addresses the importance of basing decisions about the need for right-heart catheterization on echocardiograms obtained at steady state rather than during acute illness, such as during hospitalization for pain or acute chest syndrome.

This is in part because of technical factors, Dr. Desai said.

“We know that repeating [echocardiography] is something that should be considered in patients because ... results vary – sometimes quite a bit – from study to study,” he said.

As for the cutoff values for 6MWD and NT-proBNP, “a decent amount of literature” suggests that less than 333 m and less than 160 pg/ml, respectively, are good thresholds, he said.

“Importantly, this should all be taken in the context of good clinical judgment ... along with discussion with a PH expert,” he added.

The full guidelines are available, along with additional ASH guidelines on immune thrombocytopenia and prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients, at the ASH publications website.

Of note, the SCD guidelines on cardiopulmonary disease and kidney disease are one of five sets of SCD guidelines that have been in development; these are the first of those to be published. The remaining four sets of guidelines will address pain, cerebrovascular complications, transfusion, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant. All will be published in Blood Advances, and according to Dr. Liem, the transfusion medicine guidelines have been accepted and should be published in January 2020, followed by those for cerebrovascular complications. Publication of the pain and transplant guidelines are anticipated later in 2020.

Dr. Liem and Dr. Desai reported having no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – It is good practice to consult with a pulmonary hypertension (PH) expert before referring a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD) for right-heart catheterization or PH evaluation, according to new American Society of Hematology guidelines for the screening and management of cardiopulmonary and kidney disease in patients with SCD.

That “Good Practice” recommendation is one of several included in the evidence-based guidelines published Dec. 10 in Blood Advances and highlighted during a Special Education Session at the annual ASH meeting.

The guidelines provide 10 main recommendations intended to “support patients, clinicians, and other health care professionals in their decisions about screening, diagnosis, and management of cardiopulmonary and renal complications of SCD,” wrote Robert I. Liem, MD, of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and colleagues.

The recommendations, agreed upon by a multidisciplinary guideline panel, relate to screening, diagnosis, and management of PH, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), hypertension, proteinuria and chronic kidney disease, and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Most are “conditional,” as opposed to “strong,” because of a paucity of direct, high-quality outcomes data, and they are accompanied by the Good Practice Statements, descriptive remarks and caveats based on the available data, as well as suggestions for future research.

At the special ASH session, Ankit A. Desai, MD, highlighted some of the recommendations and discussed considerations for their practical application.

The Good Practice Statement on consulting a specialist before referring a patient for PH relates specifically to Recommendations 2a and 2b on the management of abnormal echocardiography, explained Dr. Desai of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

For asymptomatic children and adults with SCD and an isolated peak tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRJV) of at least 2.5-2.9 m/s on echocardiography, the panel recommends against right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2a, conditional), he said.

For children and adults with SCD and a peak TRJV of at least 2.5 m/s who also have a reduced 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and/or elevated N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), the panel supports right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2b, conditional).

Dr. Desai noted that the 2.5 m/s threshold was found to be suboptimal when used as the sole criteria for right-heart catheterization. Using that threshold alone is associated with “moderate to large” harms, such as starting inappropriate PH-specific therapies and/or performing unnecessary right-heart catheterization. However, when used in combination with 6MWD, the predictive capacity improved significantly, and the risk for potential harm was low, he explained.

Another Good Practice Statement included in the guidelines, and relevant to these recommendations on managing abnormal echocardiography, addresses the importance of basing decisions about the need for right-heart catheterization on echocardiograms obtained at steady state rather than during acute illness, such as during hospitalization for pain or acute chest syndrome.

This is in part because of technical factors, Dr. Desai said.

“We know that repeating [echocardiography] is something that should be considered in patients because ... results vary – sometimes quite a bit – from study to study,” he said.

As for the cutoff values for 6MWD and NT-proBNP, “a decent amount of literature” suggests that less than 333 m and less than 160 pg/ml, respectively, are good thresholds, he said.

“Importantly, this should all be taken in the context of good clinical judgment ... along with discussion with a PH expert,” he added.

The full guidelines are available, along with additional ASH guidelines on immune thrombocytopenia and prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients, at the ASH publications website.

Of note, the SCD guidelines on cardiopulmonary disease and kidney disease are one of five sets of SCD guidelines that have been in development; these are the first of those to be published. The remaining four sets of guidelines will address pain, cerebrovascular complications, transfusion, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant. All will be published in Blood Advances, and according to Dr. Liem, the transfusion medicine guidelines have been accepted and should be published in January 2020, followed by those for cerebrovascular complications. Publication of the pain and transplant guidelines are anticipated later in 2020.

Dr. Liem and Dr. Desai reported having no conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – It is good practice to consult with a pulmonary hypertension (PH) expert before referring a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD) for right-heart catheterization or PH evaluation, according to new American Society of Hematology guidelines for the screening and management of cardiopulmonary and kidney disease in patients with SCD.

That “Good Practice” recommendation is one of several included in the evidence-based guidelines published Dec. 10 in Blood Advances and highlighted during a Special Education Session at the annual ASH meeting.

The guidelines provide 10 main recommendations intended to “support patients, clinicians, and other health care professionals in their decisions about screening, diagnosis, and management of cardiopulmonary and renal complications of SCD,” wrote Robert I. Liem, MD, of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and colleagues.

The recommendations, agreed upon by a multidisciplinary guideline panel, relate to screening, diagnosis, and management of PH, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), hypertension, proteinuria and chronic kidney disease, and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Most are “conditional,” as opposed to “strong,” because of a paucity of direct, high-quality outcomes data, and they are accompanied by the Good Practice Statements, descriptive remarks and caveats based on the available data, as well as suggestions for future research.

At the special ASH session, Ankit A. Desai, MD, highlighted some of the recommendations and discussed considerations for their practical application.

The Good Practice Statement on consulting a specialist before referring a patient for PH relates specifically to Recommendations 2a and 2b on the management of abnormal echocardiography, explained Dr. Desai of Indiana University, Indianapolis.

For asymptomatic children and adults with SCD and an isolated peak tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRJV) of at least 2.5-2.9 m/s on echocardiography, the panel recommends against right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2a, conditional), he said.

For children and adults with SCD and a peak TRJV of at least 2.5 m/s who also have a reduced 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and/or elevated N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), the panel supports right-heart catheterization (Recommendation 2b, conditional).

Dr. Desai noted that the 2.5 m/s threshold was found to be suboptimal when used as the sole criteria for right-heart catheterization. Using that threshold alone is associated with “moderate to large” harms, such as starting inappropriate PH-specific therapies and/or performing unnecessary right-heart catheterization. However, when used in combination with 6MWD, the predictive capacity improved significantly, and the risk for potential harm was low, he explained.

Another Good Practice Statement included in the guidelines, and relevant to these recommendations on managing abnormal echocardiography, addresses the importance of basing decisions about the need for right-heart catheterization on echocardiograms obtained at steady state rather than during acute illness, such as during hospitalization for pain or acute chest syndrome.

This is in part because of technical factors, Dr. Desai said.

“We know that repeating [echocardiography] is something that should be considered in patients because ... results vary – sometimes quite a bit – from study to study,” he said.

As for the cutoff values for 6MWD and NT-proBNP, “a decent amount of literature” suggests that less than 333 m and less than 160 pg/ml, respectively, are good thresholds, he said.

“Importantly, this should all be taken in the context of good clinical judgment ... along with discussion with a PH expert,” he added.

The full guidelines are available, along with additional ASH guidelines on immune thrombocytopenia and prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients, at the ASH publications website.

Of note, the SCD guidelines on cardiopulmonary disease and kidney disease are one of five sets of SCD guidelines that have been in development; these are the first of those to be published. The remaining four sets of guidelines will address pain, cerebrovascular complications, transfusion, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant. All will be published in Blood Advances, and according to Dr. Liem, the transfusion medicine guidelines have been accepted and should be published in January 2020, followed by those for cerebrovascular complications. Publication of the pain and transplant guidelines are anticipated later in 2020.

Dr. Liem and Dr. Desai reported having no conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASH 2019

Paid (and unpaid) time off

Many medical offices are following a popular trend in the business world: They are replacing employee sick leave, vacation, and any other miscellaneous time benefits with a combination of all of them, collectively referred to as “, and you should carefully consider all the pros and cons before adopting it.

Employees generally like the concept because most never use all their sick leave. Allowing them to take the difference as extra vacation time makes them happy, and makes your office more attractive to excellent prospects. They also appreciate being treated more like adults who can make time off decisions for themselves.

Employers like it because there is less paperwork and less abuse of sick leave. They don’t have to make any decisions about whether an employee is really sick or not; reasons for absence are now irrelevant, so feigned illnesses are a thing of the past. If an employee requests a day off with adequate notice, and there is adequate coverage of that employee’s duties, you don’t need to know (or care) about the reason for the request.

Critics say employees are absent more frequently under a PTO system, since employees who never used their full allotment of sick leave will typically use all of their PTO; but that, in a sense, is the idea. Time off is necessary and important for good office morale, and should be taken by all employees, as well as by all employers. (Remember Eastern’s First Law: Your last words will NOT be, “I wish I had spent more time in the office.”)

Besides, you should be suspicious of any employee who won’t take vacations. They are often embezzlers who fear that their illicit modus operandi will be discovered during their absence. (More on that next month.)

Most extra absences can be controlled by requiring prior approval for any time off, except emergencies. Critics point out that you are then replacing decisions about what constitutes an illness with decisions about what constitutes an emergency; but many criteria for emergencies can be settled upon in advance.

Some experts suggest dealing with increased absenteeism by allowing employees to take salary in exchange for unused PTO. I disagree because again, time off should be taken. If you want to allow PTO to be paid as salary, set a limit – say, 10%. Use the rest, or lose it.

A major issue with PTO is the possibility that employees will resist staying home when they are actually sick. Some businesses have found that employees tend to view all PTO as vacation time, and don’t want to “waste” any of it on illness. You should make it very clear that sick employees must stay home, and if they come to work sick, they will be sent home. You have an obligation to protect the rest of your employees, not to mention your patients (especially those who are elderly or immunocompromised) from a staff member with a potentially communicable illness.