User login

First advance in MDS for decade: Luspatercept for anemia

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved luspatercept (Reblozyl, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Acceleron) for the treatment of anemia in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The green light represents the first treatment advancement in MDS in more than a decade, says an expert in the field.

Luspatercept is the first and so far only erythroid maturation agent (EMA), and was launched last year when it was approved for the treatment of anemia in adults with beta thalassemia, who require regular red blood cell transfusions.

The new approval is for the treatment of anemia in adult patients with very low- to intermediate-risk MDS with ring sideroblasts and patients with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis, after they have progressed on treatment with an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent and who require two or more red blood cell (RBC) units over 8 weeks.

Luspatercept is not a substitute for RBC transfusions in patients who require immediate correction of anemia.

The FDA approval in MDS is based on results from the pivotal, placebo-controlled, phase 3 MEDALIST trial, conducted in 229 patients with very-low–, low- and intermediate-risk non-del(5q) MDS with ring sideroblasts. All patients were RBC transfusion-dependent and had disease that was refractory to, or unlikely to respond to, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Results were published in January in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study was funded by Acceleron Pharma and Celgene, which was later acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

These results were first presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), as reported by Medscape Medical News. At the time, ASH President Alexis Thompson, MD, said it appears that luspatercept can improve the production of endogenous RBCs by enhancing the maturation of these cells in the bone marrow. The drug significantly reduced the need for RBC transfusions, and “this is a very exciting advance for patients who would have few other treatment options,” she said.

“Anemia and the chronic need for transfusions is a very big issue for these patients,” commented lead study author Pierre Fenaux, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, France. “With low hemoglobin levels, patients are tired all the time and have an increased risk of falls and cardiovascular events. When you can improve hemoglobin levels, you really see a difference in quality of life.”

The MEDALIST trial is an important milestone for patients with lower-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS, commented Elizabeth Griffiths, MD, associate professor of oncology and director of MDS, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York.

“No new agents have been approved for MDS in the last 10 years, highlighting this development as a substantial step forward for the MDS community,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Current therapies are time-intensive and only modestly beneficial.”

“The availability of a new, effective drug — particularly relevant to those harboring SF3B1 mutations — is an exciting development and is likely to offer meaningful improvements in quality of life,” Griffiths said. “Since these patients tend to live longer than others with MDS, there are many patients in my clinical practice who would have fit the enrollment criteria for this study. Such patients are eagerly awaiting the opportunity for a decrease in transfusion burden.”

Study Details

In the trial, luspatercept reduced the severity of anemia — 38% of the 153 patients who received luspatercept achieved transfusion independence for 8 weeks or longer compared with 13% of the 76 patients receiving placebo (P < .001).

In the study, patients received luspatercept at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.75 mg/kg, if needed, or placebo, subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 24 weeks.

During the 16 weeks before the initiation of treatment, study patients had received a median of 5 RBC units transfusions during an 8-week period (43.2% of patients had ≥ 6 RBC units, 27.9% had ≥ 4 to < 6 RBC units, and 28.8% had < 4 RBC units). At baseline, 138 (60.3%), 58 (25.3%), and 32 (14%) patients had serum erythropoietin levels less than 200 IU/L, 200-500 IU/L, and greater than 500 IU/L, respectively.

The most common luspatercept-associated adverse events (any grade) in the trial were fatigue, diarrhea, asthenia, nausea, and dizziness. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 42.5% of patients who received luspatercept and 44.7% of patients who received placebo. The incidence of adverse events decreased over time, according to the study authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved luspatercept (Reblozyl, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Acceleron) for the treatment of anemia in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The green light represents the first treatment advancement in MDS in more than a decade, says an expert in the field.

Luspatercept is the first and so far only erythroid maturation agent (EMA), and was launched last year when it was approved for the treatment of anemia in adults with beta thalassemia, who require regular red blood cell transfusions.

The new approval is for the treatment of anemia in adult patients with very low- to intermediate-risk MDS with ring sideroblasts and patients with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis, after they have progressed on treatment with an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent and who require two or more red blood cell (RBC) units over 8 weeks.

Luspatercept is not a substitute for RBC transfusions in patients who require immediate correction of anemia.

The FDA approval in MDS is based on results from the pivotal, placebo-controlled, phase 3 MEDALIST trial, conducted in 229 patients with very-low–, low- and intermediate-risk non-del(5q) MDS with ring sideroblasts. All patients were RBC transfusion-dependent and had disease that was refractory to, or unlikely to respond to, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Results were published in January in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study was funded by Acceleron Pharma and Celgene, which was later acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

These results were first presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), as reported by Medscape Medical News. At the time, ASH President Alexis Thompson, MD, said it appears that luspatercept can improve the production of endogenous RBCs by enhancing the maturation of these cells in the bone marrow. The drug significantly reduced the need for RBC transfusions, and “this is a very exciting advance for patients who would have few other treatment options,” she said.

“Anemia and the chronic need for transfusions is a very big issue for these patients,” commented lead study author Pierre Fenaux, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, France. “With low hemoglobin levels, patients are tired all the time and have an increased risk of falls and cardiovascular events. When you can improve hemoglobin levels, you really see a difference in quality of life.”

The MEDALIST trial is an important milestone for patients with lower-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS, commented Elizabeth Griffiths, MD, associate professor of oncology and director of MDS, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York.

“No new agents have been approved for MDS in the last 10 years, highlighting this development as a substantial step forward for the MDS community,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Current therapies are time-intensive and only modestly beneficial.”

“The availability of a new, effective drug — particularly relevant to those harboring SF3B1 mutations — is an exciting development and is likely to offer meaningful improvements in quality of life,” Griffiths said. “Since these patients tend to live longer than others with MDS, there are many patients in my clinical practice who would have fit the enrollment criteria for this study. Such patients are eagerly awaiting the opportunity for a decrease in transfusion burden.”

Study Details

In the trial, luspatercept reduced the severity of anemia — 38% of the 153 patients who received luspatercept achieved transfusion independence for 8 weeks or longer compared with 13% of the 76 patients receiving placebo (P < .001).

In the study, patients received luspatercept at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.75 mg/kg, if needed, or placebo, subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 24 weeks.

During the 16 weeks before the initiation of treatment, study patients had received a median of 5 RBC units transfusions during an 8-week period (43.2% of patients had ≥ 6 RBC units, 27.9% had ≥ 4 to < 6 RBC units, and 28.8% had < 4 RBC units). At baseline, 138 (60.3%), 58 (25.3%), and 32 (14%) patients had serum erythropoietin levels less than 200 IU/L, 200-500 IU/L, and greater than 500 IU/L, respectively.

The most common luspatercept-associated adverse events (any grade) in the trial were fatigue, diarrhea, asthenia, nausea, and dizziness. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 42.5% of patients who received luspatercept and 44.7% of patients who received placebo. The incidence of adverse events decreased over time, according to the study authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved luspatercept (Reblozyl, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Acceleron) for the treatment of anemia in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The green light represents the first treatment advancement in MDS in more than a decade, says an expert in the field.

Luspatercept is the first and so far only erythroid maturation agent (EMA), and was launched last year when it was approved for the treatment of anemia in adults with beta thalassemia, who require regular red blood cell transfusions.

The new approval is for the treatment of anemia in adult patients with very low- to intermediate-risk MDS with ring sideroblasts and patients with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis, after they have progressed on treatment with an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent and who require two or more red blood cell (RBC) units over 8 weeks.

Luspatercept is not a substitute for RBC transfusions in patients who require immediate correction of anemia.

The FDA approval in MDS is based on results from the pivotal, placebo-controlled, phase 3 MEDALIST trial, conducted in 229 patients with very-low–, low- and intermediate-risk non-del(5q) MDS with ring sideroblasts. All patients were RBC transfusion-dependent and had disease that was refractory to, or unlikely to respond to, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Results were published in January in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study was funded by Acceleron Pharma and Celgene, which was later acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

These results were first presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), as reported by Medscape Medical News. At the time, ASH President Alexis Thompson, MD, said it appears that luspatercept can improve the production of endogenous RBCs by enhancing the maturation of these cells in the bone marrow. The drug significantly reduced the need for RBC transfusions, and “this is a very exciting advance for patients who would have few other treatment options,” she said.

“Anemia and the chronic need for transfusions is a very big issue for these patients,” commented lead study author Pierre Fenaux, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, France. “With low hemoglobin levels, patients are tired all the time and have an increased risk of falls and cardiovascular events. When you can improve hemoglobin levels, you really see a difference in quality of life.”

The MEDALIST trial is an important milestone for patients with lower-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS, commented Elizabeth Griffiths, MD, associate professor of oncology and director of MDS, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, New York.

“No new agents have been approved for MDS in the last 10 years, highlighting this development as a substantial step forward for the MDS community,” she told Medscape Medical News. “Current therapies are time-intensive and only modestly beneficial.”

“The availability of a new, effective drug — particularly relevant to those harboring SF3B1 mutations — is an exciting development and is likely to offer meaningful improvements in quality of life,” Griffiths said. “Since these patients tend to live longer than others with MDS, there are many patients in my clinical practice who would have fit the enrollment criteria for this study. Such patients are eagerly awaiting the opportunity for a decrease in transfusion burden.”

Study Details

In the trial, luspatercept reduced the severity of anemia — 38% of the 153 patients who received luspatercept achieved transfusion independence for 8 weeks or longer compared with 13% of the 76 patients receiving placebo (P < .001).

In the study, patients received luspatercept at a starting dose of 1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.75 mg/kg, if needed, or placebo, subcutaneously every 3 weeks for at least 24 weeks.

During the 16 weeks before the initiation of treatment, study patients had received a median of 5 RBC units transfusions during an 8-week period (43.2% of patients had ≥ 6 RBC units, 27.9% had ≥ 4 to < 6 RBC units, and 28.8% had < 4 RBC units). At baseline, 138 (60.3%), 58 (25.3%), and 32 (14%) patients had serum erythropoietin levels less than 200 IU/L, 200-500 IU/L, and greater than 500 IU/L, respectively.

The most common luspatercept-associated adverse events (any grade) in the trial were fatigue, diarrhea, asthenia, nausea, and dizziness. Grade 3 or 4 treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 42.5% of patients who received luspatercept and 44.7% of patients who received placebo. The incidence of adverse events decreased over time, according to the study authors.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Neurologic symptoms and COVID-19: What’s known, what isn’t

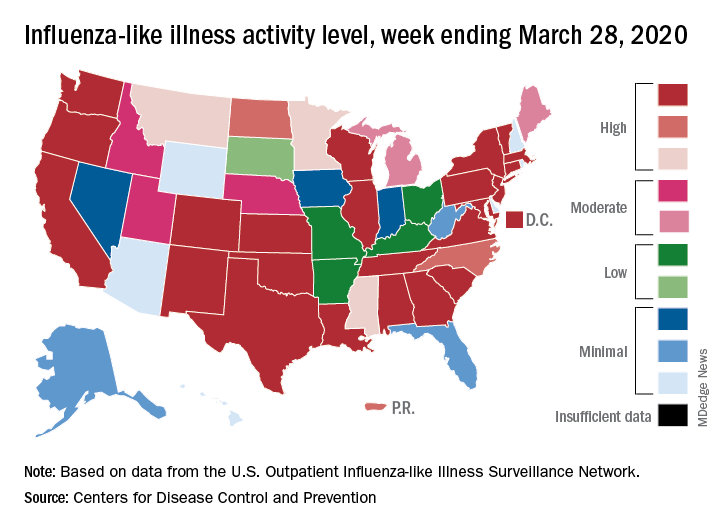

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting tendinopathy treatment (and terminology) right

The vast majority of patients with tendon problems are successfully treated nonoperatively. But which treatments should you try (and when), and which are not quite ready for prime time? This review presents the evidence for the treatment options available to you. But first, it’s important to get our terminology right.

Tendinitis vs tendinosis vs paratenonitis: Words matter

The term “tendinopathy” encompasses many issues related to tendon pathology including tendinitis, tendinosis, and paratenonitis.1,2 The clinical syndrome consists of pain, swelling, and functional impairment associated with activities of daily living or athletic performance.3 Tendinopathy may be acute or chronic, but most cases result from overuse.1

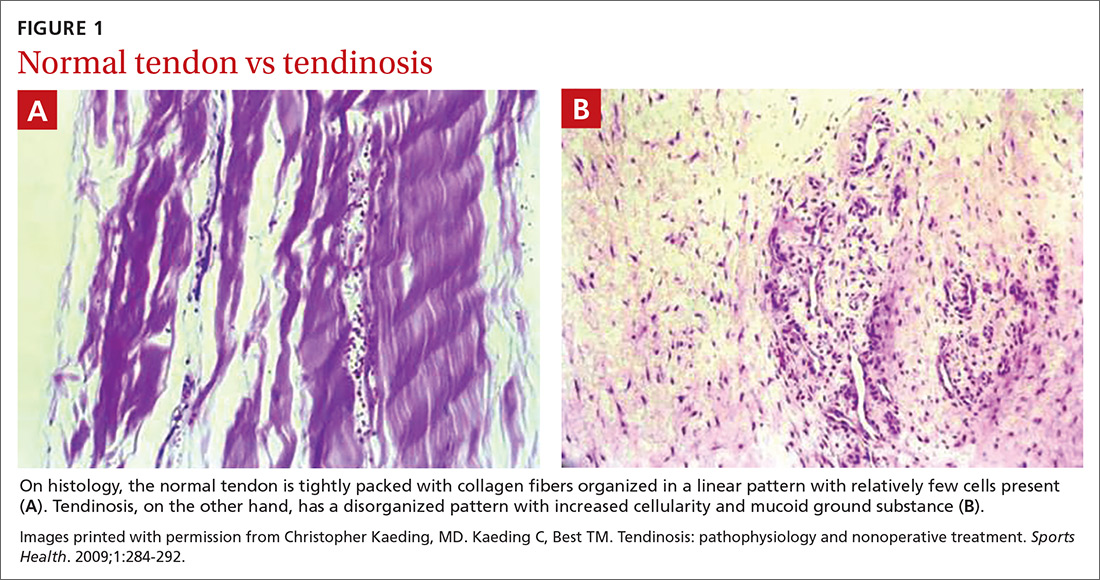

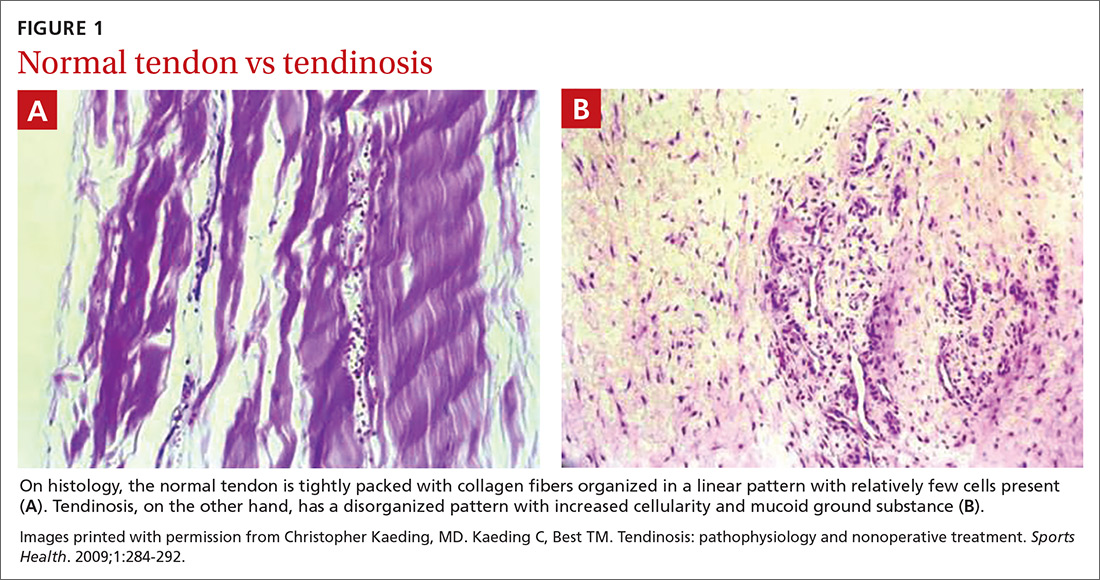

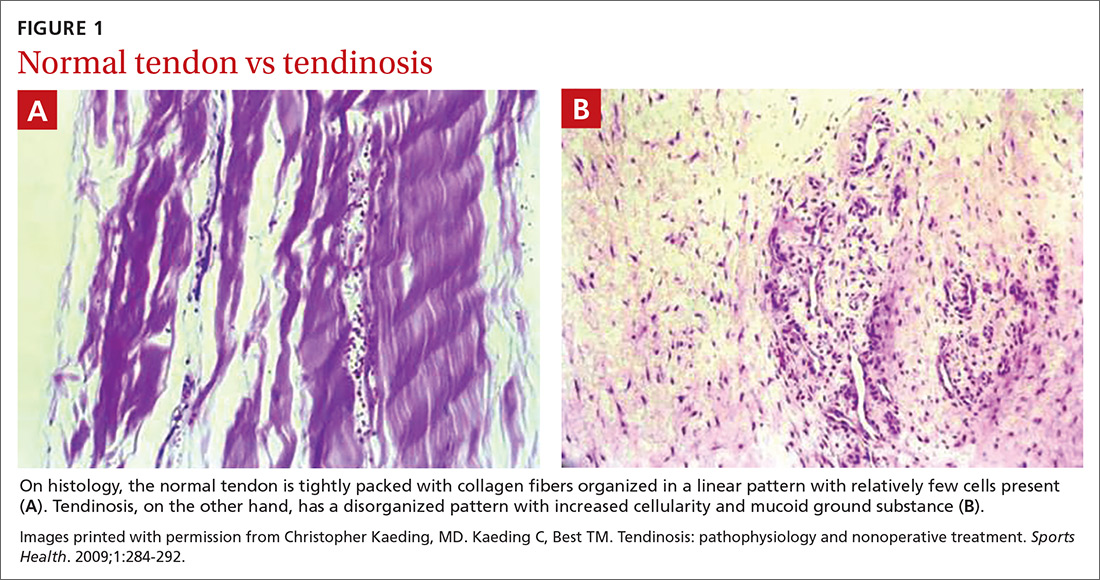

In healthy tendons, the collagen fibers are packed tightly and organized in a linear pattern (FIGURE 1A). However, tendons that are chronically overused develop cumulative microtrauma that leads to a degenerative process within the tendon that is slow (typically measured in months) to heal. This is due to the relative lack of vasculature and the slow rate of tissue turnover in tendons.2,4,5

Sports and manual labor are the most common causes of tendinopathy, but medical conditions including obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol are associated risk factors. Medications, particularly fluoroquinolones and statins, can cause tendon problems, and steroids, particularly those injected intratendinously, have been implicated in tendon rupture.4,6

The term “tendinitis” has long been used for all tendon disorders although it is best reserved for acute inflammatory conditions. For most tendon conditions resulting from overuse, the term “tendinosis” is now more widely recognized and preferred.7,8 Family physicians (FPs) should recognize that tendinitis and tendinosis differ greatly in pathophysiology and treatment.3

Tendinitis: Not as common as you think

Tendinitis is an acute inflammatory condition that accounts for only about 3% of all tendon disorders.3 Patients presenting with tendinitis usually have acute onset of pain and swelling typically either from a new activity or one to which they are unaccustomed (eg, lateral elbow pain after painting a house) or from an acute injury. Partial tearing of the affected tendon is likely, especially following injury.2,3

Tendinosis: A degenerative condition

In contrast to the acute inflammation of tendinitis, tendinosis is a degenerative condition induced by chronic overuse. It is typically encountered in athletes and laborers.2,5,8,9 Tendinotic tissue is generally regarded as noninflammatory, but recent research supports inflammation playing at least a small role, especially in closely associated tissues such as bursae and the paratenon tissue.10

Continue to: Histologically, tendinosis shows...

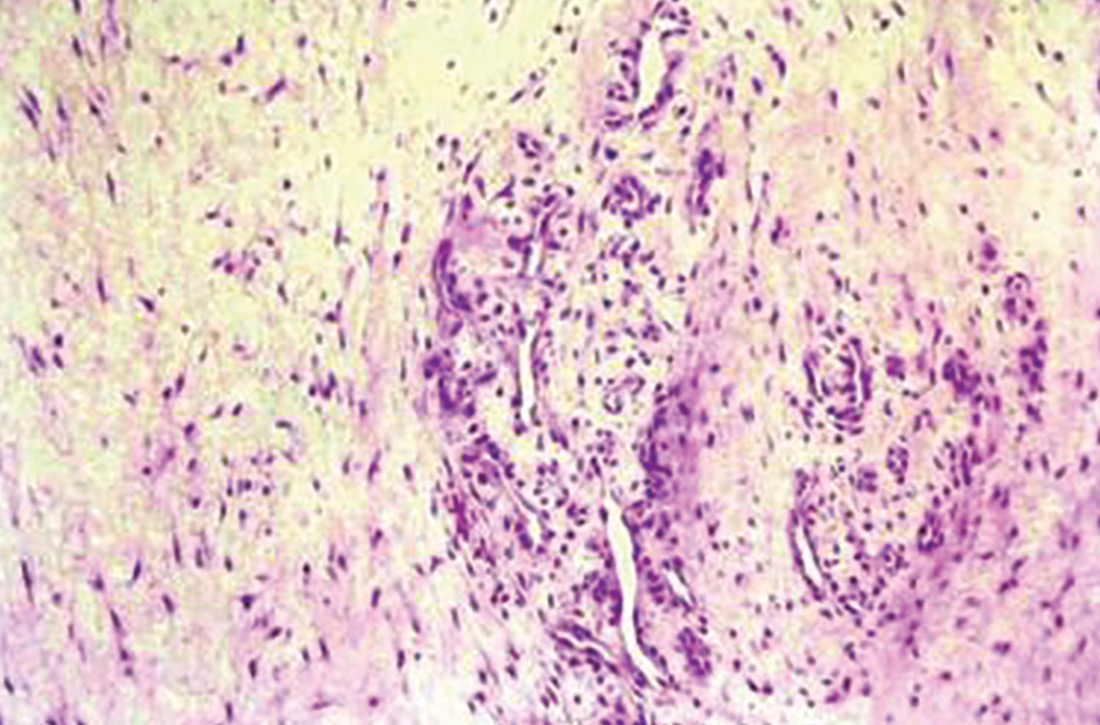

Histologically, tendinosis shows loss of the typical linear collagen fiber organization, increased mucoid ground substance, hypercellularity, and increased growth of nerves and vessels (FIGURE 1B).

Tendinosis is not always symptomatic.5,11 When pain is present, experts have proposed that it is neurogenically derived rather than from local chemical inflammation. This is supported by evidence of increases in the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and its receptor N-methyl-D-aspartate in tendinotic tissue with nerve ingrowth. Tendinotic tissue also contains substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, neuropeptides that are associated with pain and nociceptive nerve endings.2,3,6,10

Patients with tendinosis typically present with an insidious onset of a painful, thickened tendon.11 The most common tendons affected include the Achilles, the patellar, the supraspinatus, and the common extensor tendon of the lateral elbow.2 Lower extremity tendinosis is common in athletes, while upper extremity tendinopathies are more often work-related.3

Paratenonitis: Inflammation surrounding the tendon

Occasionally, tendinosis may be associated with paratenonitis, which is inflammation of the paratenon (tissue surrounding some tendons).2,5,10 Paratendinous tissue contains a higher concentration of sensory nerves than the tendon itself and may generate significant discomfort.10,11

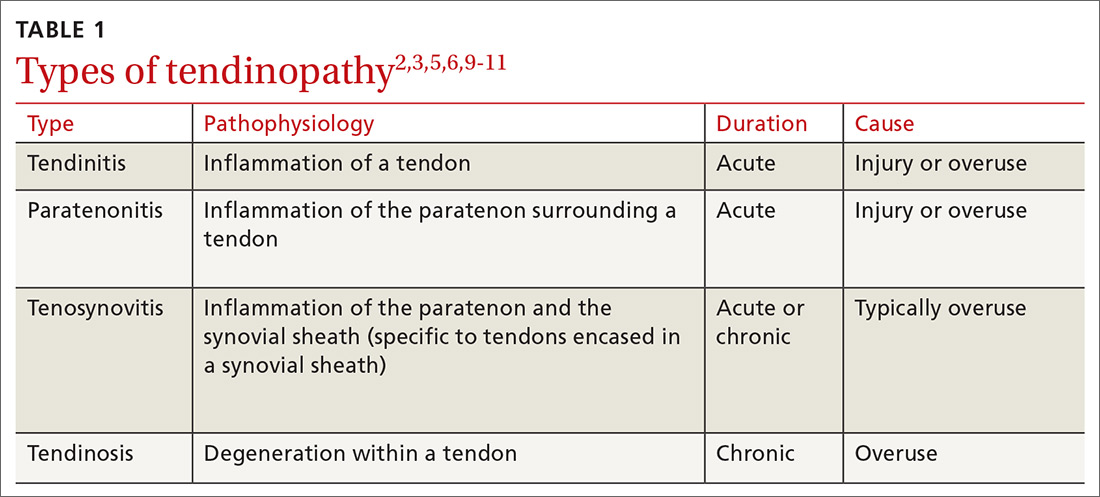

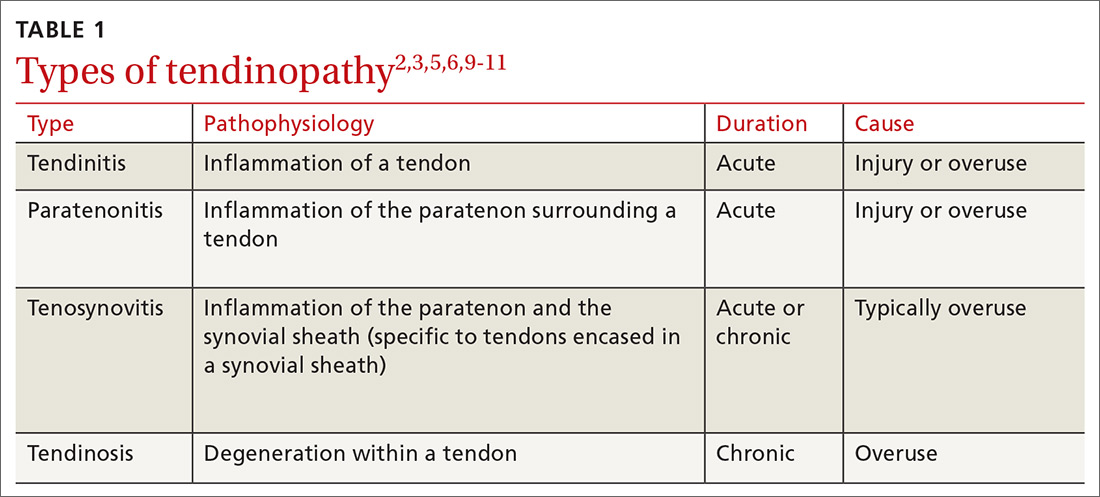

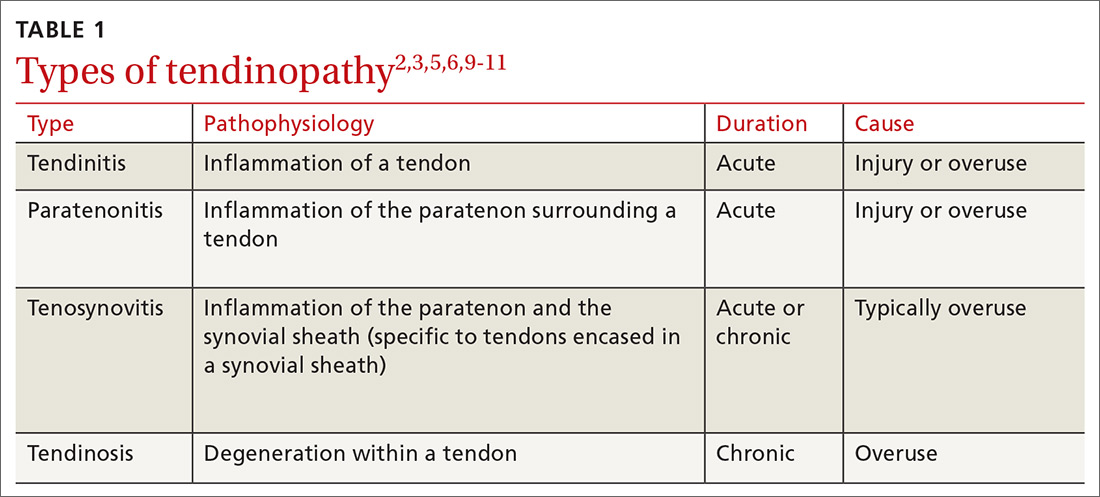

The clinical presentation of paratenonitis includes a swollen and erythematous tendon.5 The classic example—de Quervain disease—involves the first dorsal wrist compartment, in which the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons are encased in a synovial sheath. The term tenosynovitis is commonly used to indicate inflammation of both the paratenon and synovial sheath (TABLE 12,3,5,6,9-11).5

Continue to: Treatment demands time and patience

Treatment demands time and patience

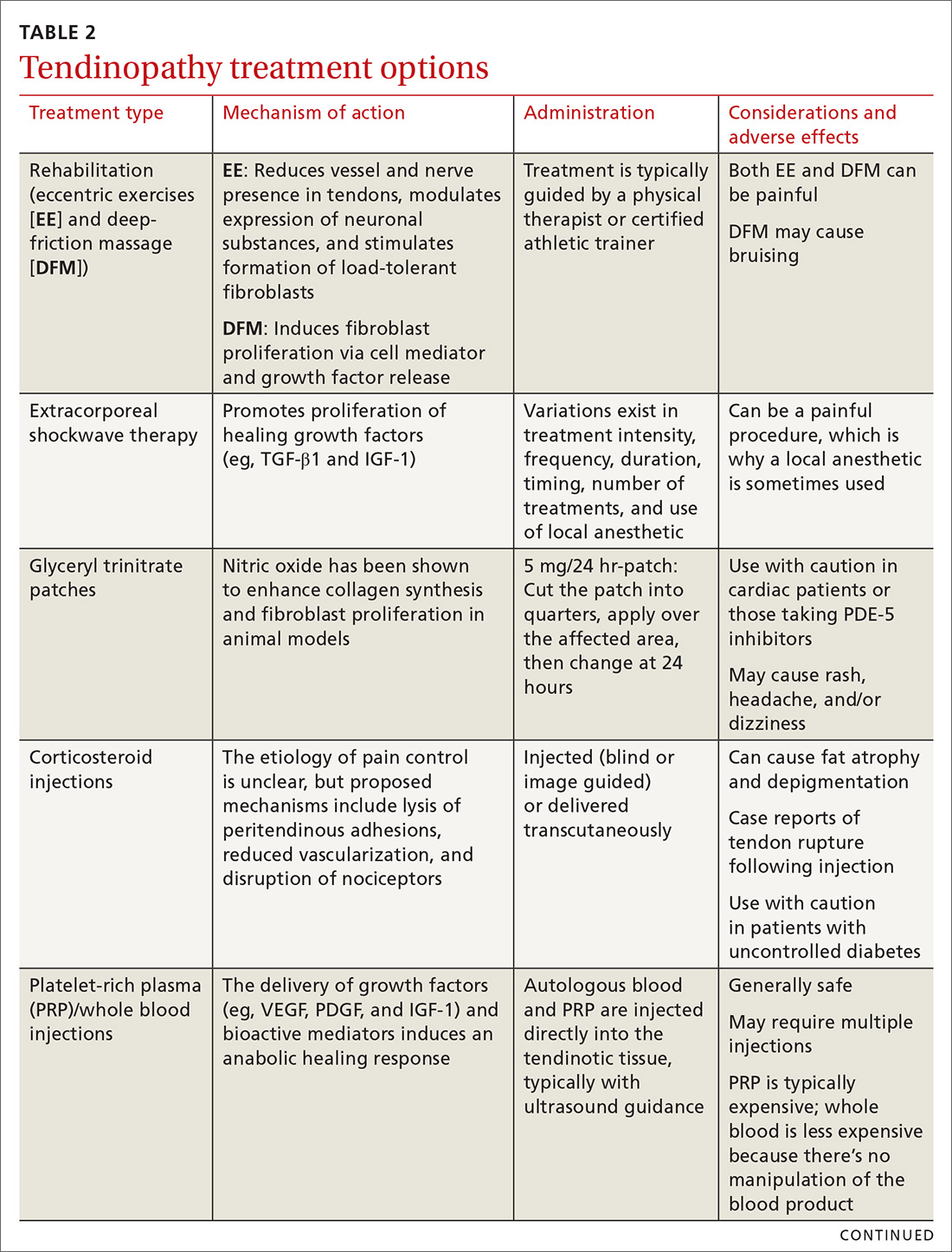

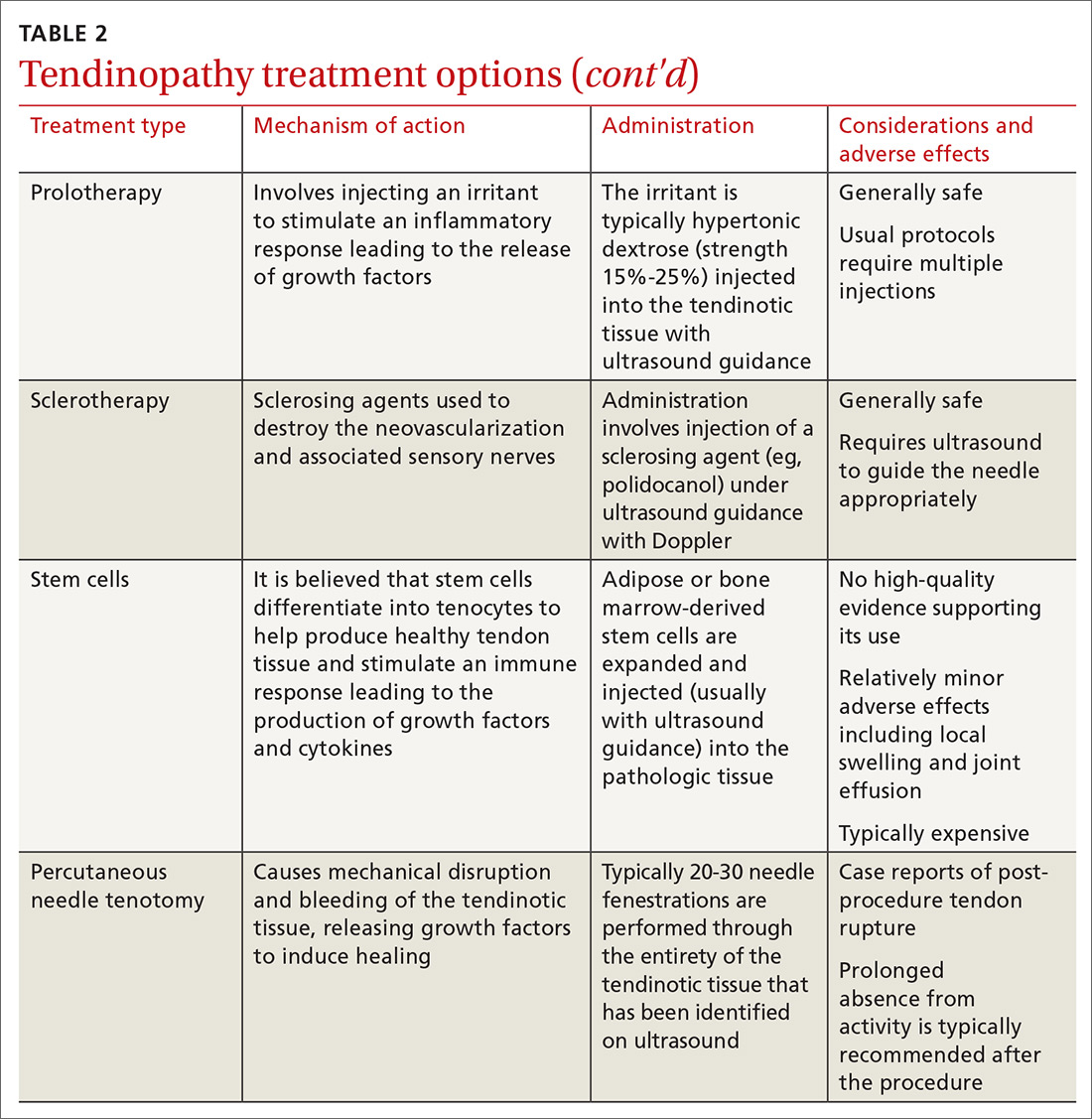

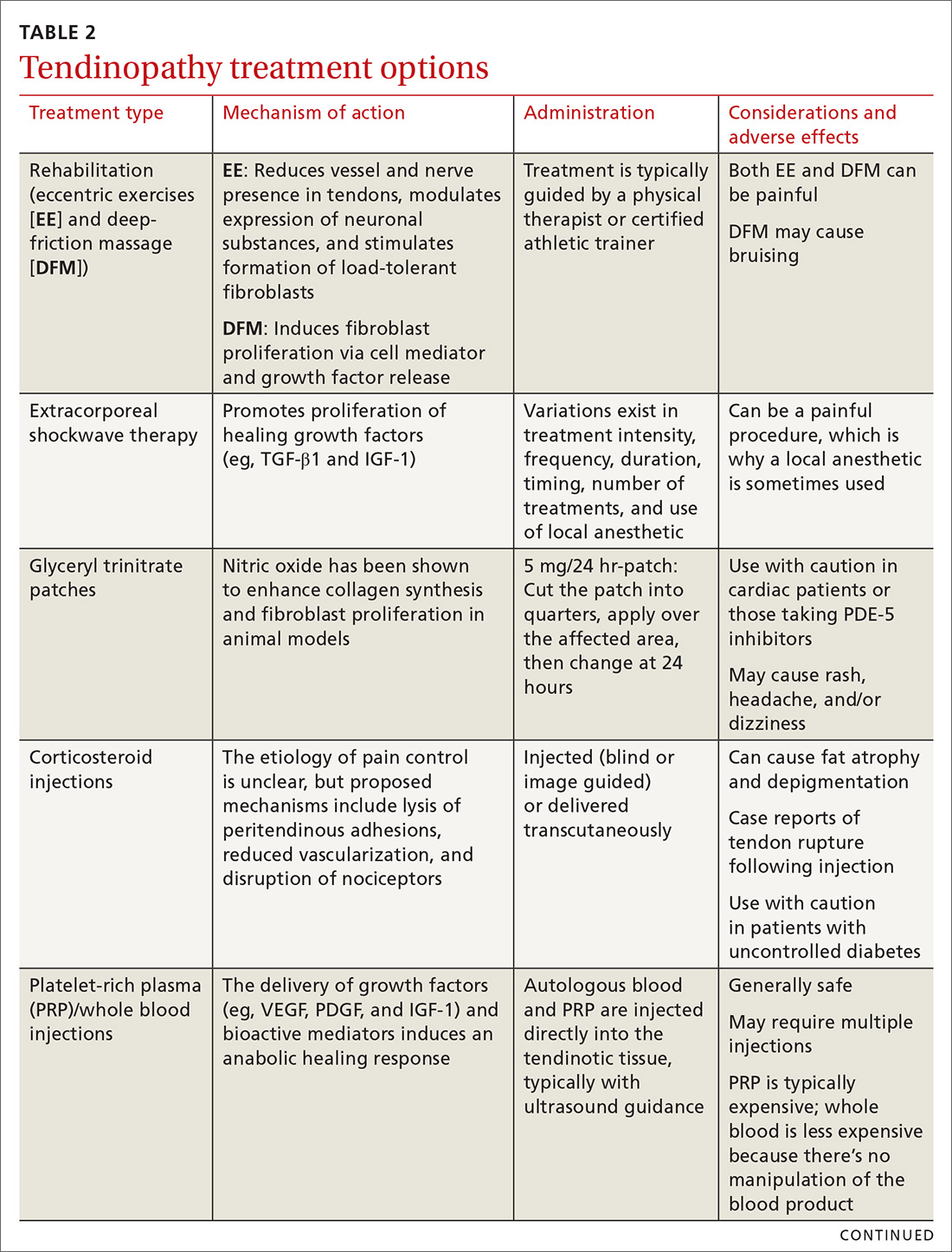

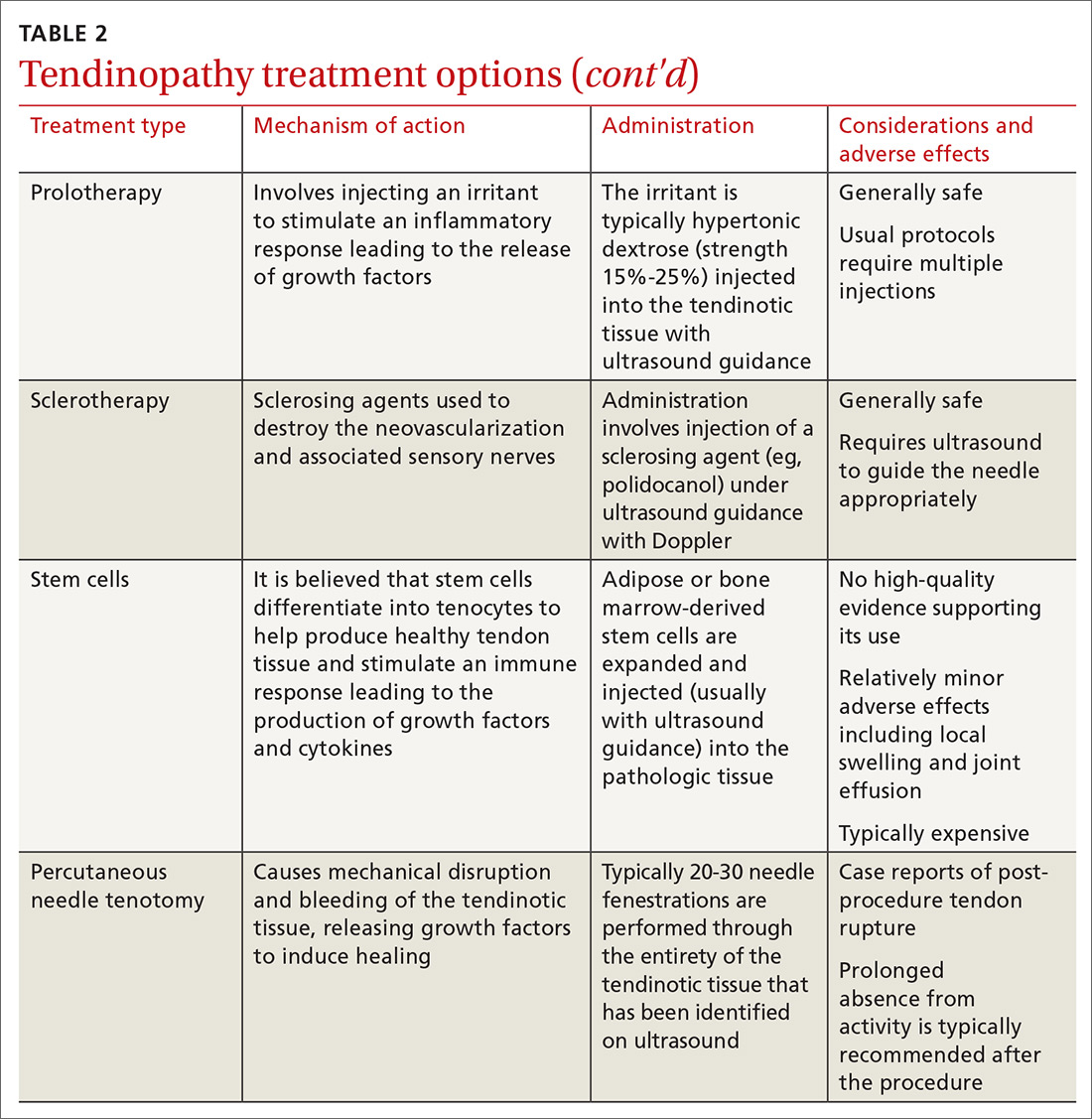

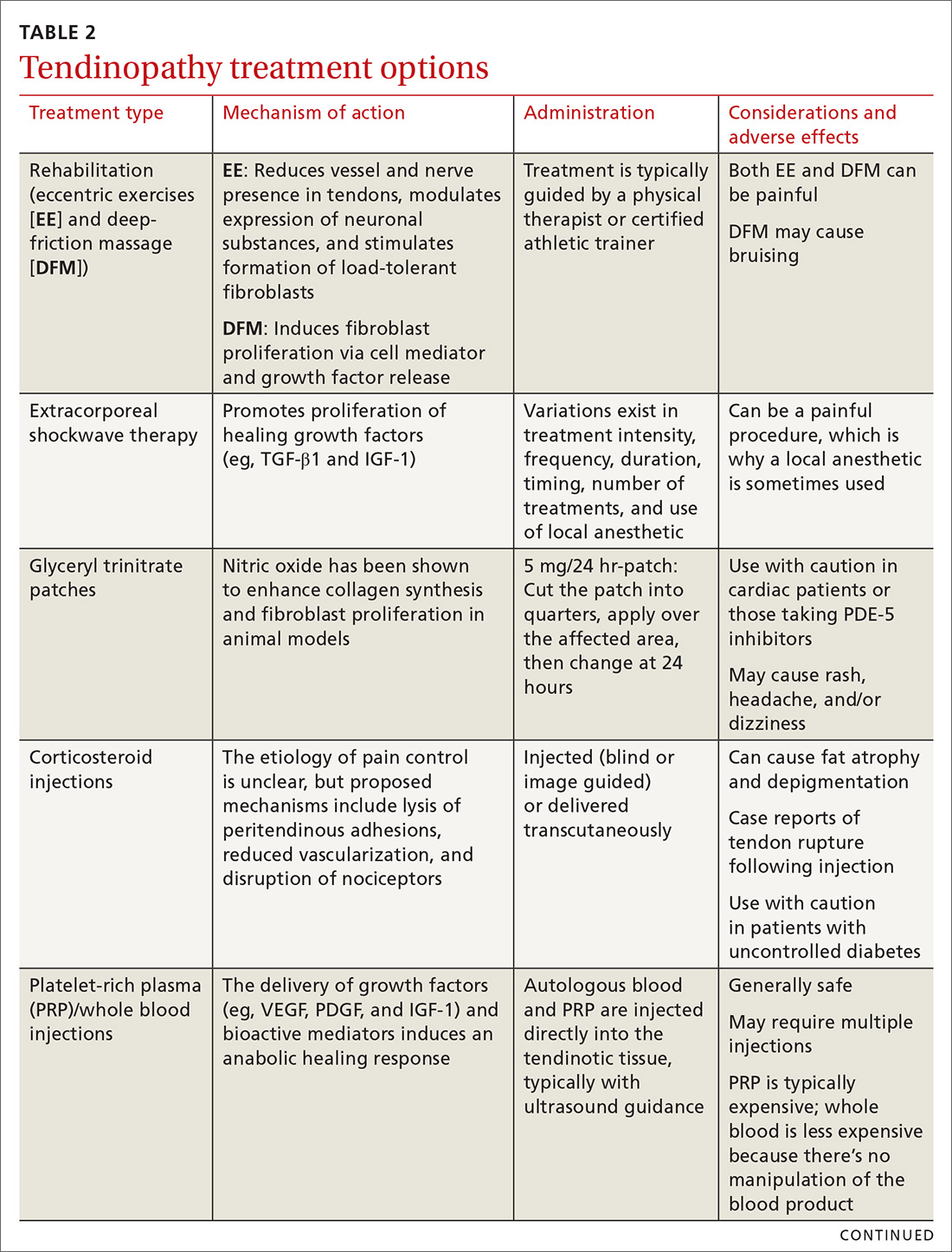

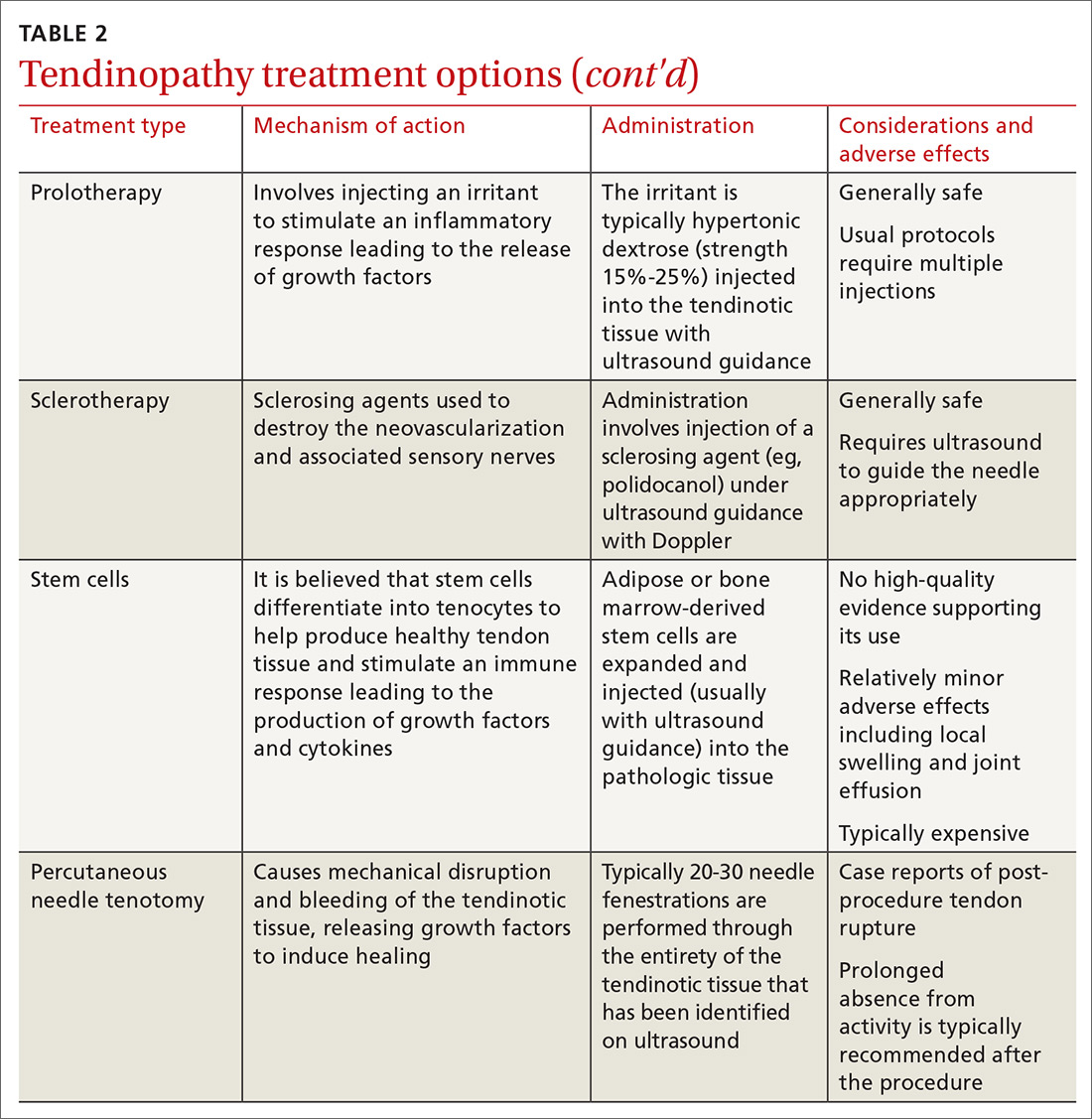

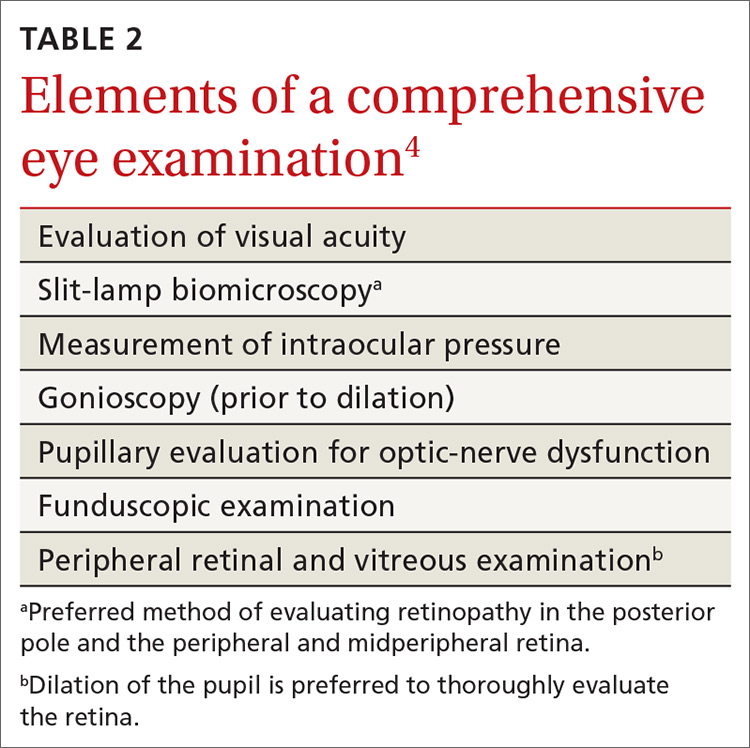

Treating tendon conditions is challenging for both the patient and the clinician. Improvement takes time and several different treatment strategies may be required for success. Given the large number of available treatment options and the often weak or limited supporting evidence of their efficacy, designing a treatment plan can be difficult. TABLE 2 summarizes the information detailed below about specific treatment options.

First-line treatments. The vast majority of patients with tendon problems are successfully treated nonoperatively. Reasonable first-line treatments, especially for inflammatory conditions like tendinitis, tenosynovitis, and paratenonitis, include relative rest, activity modification, cryotherapy, and bracing.12-14

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control are somewhat controversial. At best, they provide pain relief in the short term (7-14 days); at worst, some studies suggest potential detrimental effects to the tendon.14 If considered, NSAIDs should be used for no longer than 2 weeks. They are ideally reserved for pain control in patients with acute injuries when an inflammatory condition is likely. An alternative for pain control in inflammatory cases is a short course of oral steroids, but the adverse effects of these medications may be challenging for some patients.

Other options. If these more conservative treatments fail, or the patient is experiencing significant and debilitating pain, FPs may consider a corticosteroid injection. If this fails, or the condition is clearly past an inflammatory stage, then physical therapy should be considered. More advanced treatments, such as platelet-rich plasma injections and percutaneous needle tenotomies, are typically reserved for chronic, recalcitrant cases of tendinosis. Various other treatment options are detailed below and can be used on a case-by-case basis. Surgical management should be considered only as a last resort.

Realize that certain barriers may exist to some of these treatments. With extracorporeal shockwave therapy, for example, access to a machine can be challenging, as they are typically only found in major metropolitan areas. Polidocanol, used during sclerotherapy, can be difficult to obtain in the United States. Another challenge is cost. Not all of these procedures are covered by insurance, and they can be expensive when paying out of pocket.

Continue to: Rehabilitation...

Rehabilitation: Eccentric exercises and deep-friction massage

Studies show that eccentric exercises (EEs) help to decrease vascularity and nerve presence in affected tendons, modulate expression of neuronal substances, and may stimulate formation of load-tolerant fibroblasts.2,3

For Achilles tendinosis, EE is a well-established treatment supported by multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Improvements in patient satisfaction and pain range from 60% to 90%; evidence suggests greater success in midsubstance vs insertional Achilles tendinosis.15 The addition of deep-friction massage (DFM), which we’ll discuss in a moment, to EE appears to improve outcomes even more than EE alone.16

EE is also a beneficial treatment for patellar tendinosis,3,14 and it appears to benefit rotator cuff tendinosis,3 but research has shown EE for lateral epicondylosis to be no more effective than stretching alone.17

DFM is for treating tendinosis—not inflammatory conditions. Mechanical stimulation of the tissue being massaged releases cell mediators and growth factors that activate fibroblasts. It is typically performed with plastic or metal tools.16 DFM appears to be a reliable treatment option for the lateral elbow.18

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy appears promising; evidence is limited

Research has shown that extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) promotes the production of TGF-β1 and IGF-1 in rat models,2 and it is believed to be able to disintegrate calcium deposits and stimulate tissue repair.14 Research is generally supportive of its effectiveness in treating tendinosis; however, evidence is limited by great variability in studies in terms of treatment intensity, frequency, duration, timing, number of treatments, and use of a local anesthetic.14 ESWT appears to be useful in augmenting treatment with EE, particularly with regard to the rotator cuff.19

Continue to: A review of 10 RCTs...

A review of 10 RCTs demonstrated the effectiveness of ESWT for tennis elbow.2 ESWT for greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS, formerly known as trochanteric bursitis) appears to be more effective than corticosteroids and home exercises for outcomes at 4 months and equivalent to home exercises at 15 months.20 In patellar tendinosis, ESWT has been shown to be an effective treatment, especially under ultrasound guidance.12 Studies involving the use of ESWT for Achilles tendinosis have had mixed results for midsubstance tendinosis, and more positive results for insertional tendinosis.15 For a video on how the therapy is administered, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq5yqiWByX4.

Glyceryl trinitrate patches: Mixed results

Basic science studies have shown that nitric oxide modulates tendon healing by enhancing fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis,2,14 but that it should be used with caution in cardiac patients and in those who take PDE-5 inhibitors. Common adverse effects include rash, headache, and dizziness.

In clinical studies, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) patches show mixed results. For the upper extremity, GTN appears to be helpful for pain in the short term when combined with physical therapy, but long-term positive outcomes have been absent.21 In one Level 1 study for patellar tendinosis comparing GTN patches with EE to a placebo patch with EE, no significant difference was noted at 24 weeks.22 Benefit for Achilles tendinosis also appears to be lacking.3,23

Corticosteroid injections: Mechanism unknown

The mechanism for the beneficial effects of corticosteroid injections (CSIs) for tendinosis remains controversial. Proposed mechanisms include lysis of peritendinous adhesions, disruption of the nociceptors in the region of the injection, and decreased vascularization.10,15 Given tendinosis is generally regarded as a noninflammatory condition, and the fact that these medications have demonstrated potential negative effects on tendon healing, exercise caution when considering CSIs.2,24

Although steroids can effectively reduce pain in the short term, intermediate- and long-term studies generally show no difference or worse outcomes when they are compared to no treatment, placebo, or other treatment modalities. In fact, strong evidence exists for negative effects of steroids on lateral epicondylosis in both the intermediate (6 months) and long (1 year) term.24 Particular care is required when administering a CSI for medial epicondylosis, as the ulnar nerve is immediately posterior to the medial epicondyle.25

Continue to: In contrast...

In contrast, CSIs appear to be a reliable treatment option for de Quervain disease.26 Landmark-guided injections for GTPS can improve pain in the short term (< 1 month), but are inferior to either home exercises or ESWT beyond a few months. Thus, CSIs are a reasonable option for pain control in GTPS, but should not be the sole treatment modality.20

Studies regarding corticosteroid use for Achilles and patellar tendinosis have had mixed results. Patients can hope for mild improvement in pain at best, and the risk for relapse and tendon rupture is ever present.27 This is especially concerning given the significant load-bearing of the patellar and Achilles tendons.14,15 If you are considering a CSI for these purposes, use imaging guidance to ensure the injection is not placed intratendinously.

Platelet-rich plasma and whole blood: Inducing an anabolic healing response

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and whole blood injections both aim to deliver autologous growth factors (eg, VEGF, PDGF, and IGF-1) and bioactive mediators to the site of tendinosis to induce an anabolic healing response. PRP therapy differs from whole blood therapy in that it is withdrawn and then concentrated in a centrifuge before being injected. Patients are typically injected under ultrasound guidance. The great variation in PRP preparation, platelet concentration, use of adjunctive treatments, leukocyte concentration, and number and technique of injections makes it difficult to determine the optimal PRP treatment protocol.10,28,29

In 1 prospective RCT comparing subacromial PRP injections to CSI for the shoulder, the PRP group had better outcomes at 3 months, but similar outcomes at 6 months. The suggestion was made that PRP therapy could be an alternative treatment for individuals with a contraindication to CSIs.30

PRP therapy appears to be an effective treatment option for patellar tendinopathy.28,31 A Level 1 study comparing dry needle tenotomy and EE to dry needle tenotomy with both PRP therapy and EE found faster recovery in the PRP group.32 In another patellar tendon study comparing ESWT to PRP therapy, both were found to be effective, but PRP performed better in terms of pain, function, and satisfaction at 6 and 12 months.12 For Achilles tendons, however, the evidence is mixed; case series have had generally positive outcomes, but the only double-blind RCT found no benefit.28,31

Continue to: In lateral epicondylosis...

In lateral epicondylosis, the use of auto-logous whole blood or PRP injections appears to help both pain and function, with several studies failing to demonstrate superiority of 1 modality over the other.24,25,28,33 This raises the issue of whether PRP therapy is any more effective than whole blood for the treatment of other tendinopathies. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of studies comparing the effectiveness of 1 modality to the other, apart from those for lateral epicondylosis.

Prolotherapy: An option for these 3 conditions

Prolotherapy involves the injection of hypertonic dextrose and local anesthetic, which is believed to lead to an upregulation of inflammatory mediators and growth factors. This treatment usually involves several injections spaced 2 to 6 weeks apart over several months. High-quality studies are not available to clarify the optimal dextrose concentration or number of injections required. The few high-quality studies available support prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis, rotator cuff tendinopathy, and Osgood Schlatter disease. Lesser-quality studies support its use for refractory pain of the Achilles, hip adductors, and plantar fascia.24,34

Sclerotherapy: Not just for veins

As discussed earlier, tendinotic tissue can have neovascularization that is easily detected on Doppler ultrasound. Sensory nerves typically grow alongside the new vessels. Sclerosing agents, such as polidocanol, can be injected with ultrasound guidance into areas of neovascularization, with the intention of causing denervation and pain relief.15 Neovascularization does not always correlate with pathology, so careful patient selection is necessary.35

Studies of sclerotherapy for patellar tendinopathy are generally favorable. One comparing sclerotherapy to arthroscopic debridement showed improvement in pain from both treatments at 6 and 12 months, but the arthroscopy group had less pain, better satisfaction scores, and a faster return to sport.14 Sclerotherapy is also effective for Achilles tendinosis.15

Stem cells: Not at this time

Stem cell use for tendinosis is based on the theory that these cells possess the capability to differentiate into tenocytes to produce new, healthy tendon tissue. Additionally, stem cell injections are believed to create a local immune response, recruiting local growth factors and cytokines to aide in tendon repair. A recent systematic review failed to identify any high-quality studies (Level 4 data at best) supporting the use of stem cells in tendinopathy, and the researchers did not recommend stem cell use outside of clinical trials at this time.36

Continue to: Percutaneous needle tenotomy...

Percutaneous needle tenotomy: Consider it for difficult cases

Percutaneous needle tenotomy is thought to benefit tendinosis by disrupting the tendinotic tissue via needling, while simultaneously causing bleeding and the release of growth factors to aid in healing. Unlike surgical tenotomy, the procedure is typically performed with ultrasound guidance in the office or other ambulatory setting. After local anesthesia is administered, a needle is passed multiple times through the entire region of abnormality noted on ultrasound. Generally, around 20 to 30 needle fenestrations are performed.37,38

In one retrospective study evaluating 47 patellar tendons, 81% had excellent or good results.38 In a retrospective study for lateral epicondylosis, 80% had good to excellent results.39

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyle Goerl, MD, CAQSM, Lafene Health Center, 1105 Sunset Avenue, Manhattan, KS, 66502-3761; [email protected].

1. Andres BM, Murrell GAC. Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1539-1554.

2. Kaeding C, Best TM. Tendinosis: pathophysiology and nonoperative treatment. Sports Health. 2009;1:284-292.

3. Ackermann PW, Renstrom P. Tendinopathy in sport. Sports Health. 2012;4:193-201.

4. Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med. 1999;27:393-408.

5. Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC. Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22:675-692.

6. Scott A, Backman LJ, Speed C. Tendinopathy: update on pathophysiology. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2015;45:833-841.

7. Puddu G, Ippolito E, Postacchini F. A classification of achilles tendon disease. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4:145-150.

8. Maffulli N, Khan KM, Puddu G. Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:840-843.

9. Kraushaar B, Nirschl R. Current concepts review: tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow). J Bone Jt Surg. 1999;81:259-278.

10. Rees JD, Stride M, Scott A. Tendons—time to revisit inflammation. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1553-1557.

11. Scott A, Docking S, Vicenzino B, et al. Sports and exercise-related tendinopathies: a review of selected topical issues by participants of the second International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium (ISTS) Vancouver 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:536-544.

12. Smith J, Sellon J. Comparing PRP injections with ESWT for athletes with chronic patellar tendinopathy. Clin J Sport Med. 2014;24:88-89.

13. Mallow M, Nazarian LN. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome diagnosis and treatment. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25:279-289.

14. Schwartz A, Watson JN, Hutchinson MR. Patellar tendinopathy. Sports Health. 2015;7:415-420.

15. Magnussen RA, Dunn WR, Thomson AB. Nonoperative treatment of midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:54-64.

16. Mccormack JR, Underwood FB, Slaven EJ, et al. Eccentric exercise versus eccentric exercise and soft tissue treatment (Astym) in the management of insertional Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Sports Health. 2016;8:230-237.

17. Wen DY, Schultz BJ, Schaal B, et al. Eccentric strengthening for chronic lateral epicondylosis: a prospective randomized study. Sports Health. 2011;3:500-503.

18. Yi R, Bratchenko WW, Tan V. Deep friction massage versus steroid injection in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Hand (N Y). 2018;13:56-59.

19. Su X, Li Z, Liu Z, et al. Effects of high- and low-energy radial shock waves therapy combined with physiotherapy in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a retrospective study. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:2488-2494.

20. Barratt PA, Brookes N, Newson A. Conservative treatments for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:97-104.

21. Nguyen L, Kelsberg G, Beecher D, et al. Clinical inquiries: are topical nitrates safe and effective for upper extremity tendinopathies? J Fam Pract. 2014;63:469-470.

22. Steunebrink M, Zwerver J, Brandsema R, et al. Topical glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:34-39.

23. Kane TPC, Ismail M, Calder JDF. Topical glyceryl trinitrate and noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1160-1163.

24. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1751-1767.

25. Taylor SA, Hannafin JA. Evaluation and management of elbow tendinopathy. Sports Health. 2012;4:384-393.

26. Sawaizumi T, Nanno M, Ito H. De Quervain’s disease: efficacy of intra-sheath triamcinolone injection. Int Orthop. 2007;31:265-268.

27. Chen SK, Lu CC, Chou PH, et al. Patellar tendon ruptures in weight lifters after local steroid injections. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:369-372.

28. Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Kon E, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in tendon-related disorders: results and indications. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:1984-1999.

29. Cong GT, Carballo C, Camp CL, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in treating patellar tendinopathy. Oper Tech Orthop. 2016;26:110-116.

30. Shams A, El-Sayed M, Gamal O, et al. Subacromial injection of autologous platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid for the treatment of symptomatic partial rotator cuff tears. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:837-842.

31. DiMatteo B, Filardo G, Kon E, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence for the treatment of patellar and Achilles tendinopathy — a systematic review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2015;99:1-9.

32. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618.

33. Ellenbecker TS, Nirschl R, Renstrom P. Current concepts in examination and treatment of elbow tendon injury. Sports Health. 2013;5:186-194.

34. Rabago D, Nourani B. Prolotherapy for osteoarthritis and tendinopathy: a descriptive review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19:34.

35. Kardouni JR, Seitz AL, Walsworth MK, et al. Neovascularization prevalence in the supraspinatus of patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23:444-449.

36. Pas HIMFL, Moen MH, Haisma HJ, et al. No evidence for the use of stem cell therapy for tendon disorders: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:996-1002.

37. Housner JA, Jacobson JA, Misko R. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle tenotomy for the treatment of chronic tendinosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1187-1192.

38. Housner JA, Jacobson JA, Morag Y, et al. Should ultrasound-guided needle fenestration be considered as a treatment option for recalcitrant patellar tendinopathy? A retrospective study of 47 cases. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20:488-490.

39. McShane JM, Nazarian LN, Harwood MI. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle tenotomy for treatment of common extensor tendinosis in the elbow. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1281-1289.

The vast majority of patients with tendon problems are successfully treated nonoperatively. But which treatments should you try (and when), and which are not quite ready for prime time? This review presents the evidence for the treatment options available to you. But first, it’s important to get our terminology right.

Tendinitis vs tendinosis vs paratenonitis: Words matter

The term “tendinopathy” encompasses many issues related to tendon pathology including tendinitis, tendinosis, and paratenonitis.1,2 The clinical syndrome consists of pain, swelling, and functional impairment associated with activities of daily living or athletic performance.3 Tendinopathy may be acute or chronic, but most cases result from overuse.1

In healthy tendons, the collagen fibers are packed tightly and organized in a linear pattern (FIGURE 1A). However, tendons that are chronically overused develop cumulative microtrauma that leads to a degenerative process within the tendon that is slow (typically measured in months) to heal. This is due to the relative lack of vasculature and the slow rate of tissue turnover in tendons.2,4,5

Sports and manual labor are the most common causes of tendinopathy, but medical conditions including obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol are associated risk factors. Medications, particularly fluoroquinolones and statins, can cause tendon problems, and steroids, particularly those injected intratendinously, have been implicated in tendon rupture.4,6

The term “tendinitis” has long been used for all tendon disorders although it is best reserved for acute inflammatory conditions. For most tendon conditions resulting from overuse, the term “tendinosis” is now more widely recognized and preferred.7,8 Family physicians (FPs) should recognize that tendinitis and tendinosis differ greatly in pathophysiology and treatment.3

Tendinitis: Not as common as you think

Tendinitis is an acute inflammatory condition that accounts for only about 3% of all tendon disorders.3 Patients presenting with tendinitis usually have acute onset of pain and swelling typically either from a new activity or one to which they are unaccustomed (eg, lateral elbow pain after painting a house) or from an acute injury. Partial tearing of the affected tendon is likely, especially following injury.2,3

Tendinosis: A degenerative condition

In contrast to the acute inflammation of tendinitis, tendinosis is a degenerative condition induced by chronic overuse. It is typically encountered in athletes and laborers.2,5,8,9 Tendinotic tissue is generally regarded as noninflammatory, but recent research supports inflammation playing at least a small role, especially in closely associated tissues such as bursae and the paratenon tissue.10

Continue to: Histologically, tendinosis shows...

Histologically, tendinosis shows loss of the typical linear collagen fiber organization, increased mucoid ground substance, hypercellularity, and increased growth of nerves and vessels (FIGURE 1B).

Tendinosis is not always symptomatic.5,11 When pain is present, experts have proposed that it is neurogenically derived rather than from local chemical inflammation. This is supported by evidence of increases in the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and its receptor N-methyl-D-aspartate in tendinotic tissue with nerve ingrowth. Tendinotic tissue also contains substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, neuropeptides that are associated with pain and nociceptive nerve endings.2,3,6,10

Patients with tendinosis typically present with an insidious onset of a painful, thickened tendon.11 The most common tendons affected include the Achilles, the patellar, the supraspinatus, and the common extensor tendon of the lateral elbow.2 Lower extremity tendinosis is common in athletes, while upper extremity tendinopathies are more often work-related.3

Paratenonitis: Inflammation surrounding the tendon

Occasionally, tendinosis may be associated with paratenonitis, which is inflammation of the paratenon (tissue surrounding some tendons).2,5,10 Paratendinous tissue contains a higher concentration of sensory nerves than the tendon itself and may generate significant discomfort.10,11

The clinical presentation of paratenonitis includes a swollen and erythematous tendon.5 The classic example—de Quervain disease—involves the first dorsal wrist compartment, in which the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons are encased in a synovial sheath. The term tenosynovitis is commonly used to indicate inflammation of both the paratenon and synovial sheath (TABLE 12,3,5,6,9-11).5

Continue to: Treatment demands time and patience

Treatment demands time and patience

Treating tendon conditions is challenging for both the patient and the clinician. Improvement takes time and several different treatment strategies may be required for success. Given the large number of available treatment options and the often weak or limited supporting evidence of their efficacy, designing a treatment plan can be difficult. TABLE 2 summarizes the information detailed below about specific treatment options.

First-line treatments. The vast majority of patients with tendon problems are successfully treated nonoperatively. Reasonable first-line treatments, especially for inflammatory conditions like tendinitis, tenosynovitis, and paratenonitis, include relative rest, activity modification, cryotherapy, and bracing.12-14

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control are somewhat controversial. At best, they provide pain relief in the short term (7-14 days); at worst, some studies suggest potential detrimental effects to the tendon.14 If considered, NSAIDs should be used for no longer than 2 weeks. They are ideally reserved for pain control in patients with acute injuries when an inflammatory condition is likely. An alternative for pain control in inflammatory cases is a short course of oral steroids, but the adverse effects of these medications may be challenging for some patients.

Other options. If these more conservative treatments fail, or the patient is experiencing significant and debilitating pain, FPs may consider a corticosteroid injection. If this fails, or the condition is clearly past an inflammatory stage, then physical therapy should be considered. More advanced treatments, such as platelet-rich plasma injections and percutaneous needle tenotomies, are typically reserved for chronic, recalcitrant cases of tendinosis. Various other treatment options are detailed below and can be used on a case-by-case basis. Surgical management should be considered only as a last resort.

Realize that certain barriers may exist to some of these treatments. With extracorporeal shockwave therapy, for example, access to a machine can be challenging, as they are typically only found in major metropolitan areas. Polidocanol, used during sclerotherapy, can be difficult to obtain in the United States. Another challenge is cost. Not all of these procedures are covered by insurance, and they can be expensive when paying out of pocket.

Continue to: Rehabilitation...

Rehabilitation: Eccentric exercises and deep-friction massage

Studies show that eccentric exercises (EEs) help to decrease vascularity and nerve presence in affected tendons, modulate expression of neuronal substances, and may stimulate formation of load-tolerant fibroblasts.2,3

For Achilles tendinosis, EE is a well-established treatment supported by multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Improvements in patient satisfaction and pain range from 60% to 90%; evidence suggests greater success in midsubstance vs insertional Achilles tendinosis.15 The addition of deep-friction massage (DFM), which we’ll discuss in a moment, to EE appears to improve outcomes even more than EE alone.16

EE is also a beneficial treatment for patellar tendinosis,3,14 and it appears to benefit rotator cuff tendinosis,3 but research has shown EE for lateral epicondylosis to be no more effective than stretching alone.17

DFM is for treating tendinosis—not inflammatory conditions. Mechanical stimulation of the tissue being massaged releases cell mediators and growth factors that activate fibroblasts. It is typically performed with plastic or metal tools.16 DFM appears to be a reliable treatment option for the lateral elbow.18

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy appears promising; evidence is limited

Research has shown that extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) promotes the production of TGF-β1 and IGF-1 in rat models,2 and it is believed to be able to disintegrate calcium deposits and stimulate tissue repair.14 Research is generally supportive of its effectiveness in treating tendinosis; however, evidence is limited by great variability in studies in terms of treatment intensity, frequency, duration, timing, number of treatments, and use of a local anesthetic.14 ESWT appears to be useful in augmenting treatment with EE, particularly with regard to the rotator cuff.19

Continue to: A review of 10 RCTs...

A review of 10 RCTs demonstrated the effectiveness of ESWT for tennis elbow.2 ESWT for greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS, formerly known as trochanteric bursitis) appears to be more effective than corticosteroids and home exercises for outcomes at 4 months and equivalent to home exercises at 15 months.20 In patellar tendinosis, ESWT has been shown to be an effective treatment, especially under ultrasound guidance.12 Studies involving the use of ESWT for Achilles tendinosis have had mixed results for midsubstance tendinosis, and more positive results for insertional tendinosis.15 For a video on how the therapy is administered, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq5yqiWByX4.

Glyceryl trinitrate patches: Mixed results

Basic science studies have shown that nitric oxide modulates tendon healing by enhancing fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis,2,14 but that it should be used with caution in cardiac patients and in those who take PDE-5 inhibitors. Common adverse effects include rash, headache, and dizziness.

In clinical studies, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) patches show mixed results. For the upper extremity, GTN appears to be helpful for pain in the short term when combined with physical therapy, but long-term positive outcomes have been absent.21 In one Level 1 study for patellar tendinosis comparing GTN patches with EE to a placebo patch with EE, no significant difference was noted at 24 weeks.22 Benefit for Achilles tendinosis also appears to be lacking.3,23

Corticosteroid injections: Mechanism unknown

The mechanism for the beneficial effects of corticosteroid injections (CSIs) for tendinosis remains controversial. Proposed mechanisms include lysis of peritendinous adhesions, disruption of the nociceptors in the region of the injection, and decreased vascularization.10,15 Given tendinosis is generally regarded as a noninflammatory condition, and the fact that these medications have demonstrated potential negative effects on tendon healing, exercise caution when considering CSIs.2,24

Although steroids can effectively reduce pain in the short term, intermediate- and long-term studies generally show no difference or worse outcomes when they are compared to no treatment, placebo, or other treatment modalities. In fact, strong evidence exists for negative effects of steroids on lateral epicondylosis in both the intermediate (6 months) and long (1 year) term.24 Particular care is required when administering a CSI for medial epicondylosis, as the ulnar nerve is immediately posterior to the medial epicondyle.25

Continue to: In contrast...

In contrast, CSIs appear to be a reliable treatment option for de Quervain disease.26 Landmark-guided injections for GTPS can improve pain in the short term (< 1 month), but are inferior to either home exercises or ESWT beyond a few months. Thus, CSIs are a reasonable option for pain control in GTPS, but should not be the sole treatment modality.20

Studies regarding corticosteroid use for Achilles and patellar tendinosis have had mixed results. Patients can hope for mild improvement in pain at best, and the risk for relapse and tendon rupture is ever present.27 This is especially concerning given the significant load-bearing of the patellar and Achilles tendons.14,15 If you are considering a CSI for these purposes, use imaging guidance to ensure the injection is not placed intratendinously.

Platelet-rich plasma and whole blood: Inducing an anabolic healing response

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and whole blood injections both aim to deliver autologous growth factors (eg, VEGF, PDGF, and IGF-1) and bioactive mediators to the site of tendinosis to induce an anabolic healing response. PRP therapy differs from whole blood therapy in that it is withdrawn and then concentrated in a centrifuge before being injected. Patients are typically injected under ultrasound guidance. The great variation in PRP preparation, platelet concentration, use of adjunctive treatments, leukocyte concentration, and number and technique of injections makes it difficult to determine the optimal PRP treatment protocol.10,28,29

In 1 prospective RCT comparing subacromial PRP injections to CSI for the shoulder, the PRP group had better outcomes at 3 months, but similar outcomes at 6 months. The suggestion was made that PRP therapy could be an alternative treatment for individuals with a contraindication to CSIs.30

PRP therapy appears to be an effective treatment option for patellar tendinopathy.28,31 A Level 1 study comparing dry needle tenotomy and EE to dry needle tenotomy with both PRP therapy and EE found faster recovery in the PRP group.32 In another patellar tendon study comparing ESWT to PRP therapy, both were found to be effective, but PRP performed better in terms of pain, function, and satisfaction at 6 and 12 months.12 For Achilles tendons, however, the evidence is mixed; case series have had generally positive outcomes, but the only double-blind RCT found no benefit.28,31

Continue to: In lateral epicondylosis...

In lateral epicondylosis, the use of auto-logous whole blood or PRP injections appears to help both pain and function, with several studies failing to demonstrate superiority of 1 modality over the other.24,25,28,33 This raises the issue of whether PRP therapy is any more effective than whole blood for the treatment of other tendinopathies. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of studies comparing the effectiveness of 1 modality to the other, apart from those for lateral epicondylosis.

Prolotherapy: An option for these 3 conditions

Prolotherapy involves the injection of hypertonic dextrose and local anesthetic, which is believed to lead to an upregulation of inflammatory mediators and growth factors. This treatment usually involves several injections spaced 2 to 6 weeks apart over several months. High-quality studies are not available to clarify the optimal dextrose concentration or number of injections required. The few high-quality studies available support prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis, rotator cuff tendinopathy, and Osgood Schlatter disease. Lesser-quality studies support its use for refractory pain of the Achilles, hip adductors, and plantar fascia.24,34

Sclerotherapy: Not just for veins

As discussed earlier, tendinotic tissue can have neovascularization that is easily detected on Doppler ultrasound. Sensory nerves typically grow alongside the new vessels. Sclerosing agents, such as polidocanol, can be injected with ultrasound guidance into areas of neovascularization, with the intention of causing denervation and pain relief.15 Neovascularization does not always correlate with pathology, so careful patient selection is necessary.35

Studies of sclerotherapy for patellar tendinopathy are generally favorable. One comparing sclerotherapy to arthroscopic debridement showed improvement in pain from both treatments at 6 and 12 months, but the arthroscopy group had less pain, better satisfaction scores, and a faster return to sport.14 Sclerotherapy is also effective for Achilles tendinosis.15

Stem cells: Not at this time

Stem cell use for tendinosis is based on the theory that these cells possess the capability to differentiate into tenocytes to produce new, healthy tendon tissue. Additionally, stem cell injections are believed to create a local immune response, recruiting local growth factors and cytokines to aide in tendon repair. A recent systematic review failed to identify any high-quality studies (Level 4 data at best) supporting the use of stem cells in tendinopathy, and the researchers did not recommend stem cell use outside of clinical trials at this time.36

Continue to: Percutaneous needle tenotomy...

Percutaneous needle tenotomy: Consider it for difficult cases

Percutaneous needle tenotomy is thought to benefit tendinosis by disrupting the tendinotic tissue via needling, while simultaneously causing bleeding and the release of growth factors to aid in healing. Unlike surgical tenotomy, the procedure is typically performed with ultrasound guidance in the office or other ambulatory setting. After local anesthesia is administered, a needle is passed multiple times through the entire region of abnormality noted on ultrasound. Generally, around 20 to 30 needle fenestrations are performed.37,38

In one retrospective study evaluating 47 patellar tendons, 81% had excellent or good results.38 In a retrospective study for lateral epicondylosis, 80% had good to excellent results.39

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyle Goerl, MD, CAQSM, Lafene Health Center, 1105 Sunset Avenue, Manhattan, KS, 66502-3761; [email protected].

The vast majority of patients with tendon problems are successfully treated nonoperatively. But which treatments should you try (and when), and which are not quite ready for prime time? This review presents the evidence for the treatment options available to you. But first, it’s important to get our terminology right.

Tendinitis vs tendinosis vs paratenonitis: Words matter

The term “tendinopathy” encompasses many issues related to tendon pathology including tendinitis, tendinosis, and paratenonitis.1,2 The clinical syndrome consists of pain, swelling, and functional impairment associated with activities of daily living or athletic performance.3 Tendinopathy may be acute or chronic, but most cases result from overuse.1

In healthy tendons, the collagen fibers are packed tightly and organized in a linear pattern (FIGURE 1A). However, tendons that are chronically overused develop cumulative microtrauma that leads to a degenerative process within the tendon that is slow (typically measured in months) to heal. This is due to the relative lack of vasculature and the slow rate of tissue turnover in tendons.2,4,5