User login

Promising efficacy with adavosertib in uterine serous carcinoma

The experimental agent adavosertib showed hints of efficacy against recurrent uterine serous carcinoma in early data from a phase 2 trial.

The overall response rate among 21 patients with advanced uterine serous carcinoma treated with adavosertib monotherapy was 30%, and an additional patient had an unconfirmed response at the time of data cutoff, reported Joyce F. Liu, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues.

“These results were noteworthy for the preliminary response rate of 30% that was observed in the first cohort of patients on this study, especially as, on average, patients on this study had received three prior treatments for their cancer. For us, this was an exciting signal of activity, especially for a targeted therapy used by itself in this type of cancer,” Dr. Liu said in an interview.

Preliminary results of the phase 2 trial were published in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adavosertib is a small molecule that inhibits the Wee1 kinase, a “gatekeeper” of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint that is highly expressed and active in several types of cancer.

“Molecular characterization of these cancers has demonstrated that they have frequent p53 mutations as well as significant alterations in oncogenes,” Dr. Liu said. “These characteristics mean that these are cancers that may both have significant dysregulation of their cell cycle combined with high levels of replication stress. We hypothesized that these cancers could therefore be particularly vulnerable to further dysregulation of the cell cycle, which can be mediated by a drug such as adavosertib, which interrupts regulation of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint by inhibiting the protein Wee1.”

Study details

The study enrolled women with recurrent uterine serous carcinoma. Patients were eligible if any disease component was considered to be serous, except for carcinosarcomas. The patients had a minimum of one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen (median 3, range 1-7), with no upper limit on prior lines of therapy required for eligibility.

Patients with microsatellite high/deficient mismatch repair disease had to have received prior therapy with programmed death-1/ligand-1 inhibitor, or to have been deemed ineligible for immunotherapy with a checkpoint inhibitor.

The patients received adavosertib at 300 mg daily on days 1 through 5 and days 8 through 12 of each 21-day cycle.

The trial would be considered successful if at least of 4 of 35 patients planned for accrual had a confirmed response or if 8 patients were progression free at 6 months. The coprimary endpoints are overall response rate of 20% or more, or a progression-free survival rate at 6 months of 30% or more.

Results and next steps

As of Aug. 20, 2019, the investigators had enrolled 27 patients, of whom 21 were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate was 30%, consisting of six confirmed partial responses. One additional patient had an unconfirmed response. Eleven of the 21 patients had stable disease, and 3 had disease progression.

Eleven patients remained on treatment with adavosertib at the time of data cutoff. Progression-free survival data were not mature.

The most frequent adverse events included anemia and diarrhea in 67% of patients each, nausea in 58%, and fatigue in 50%.

Frequent grade 3 or higher adverse effects included anemia, neutropenia, and syncope, all occurring in 21% of patients.

Dr. Liu said the investigators plan to present updated data from the study at a future meeting.

“We are planning additional cohorts in this study that will allow us to more deeply investigate why certain uterine serous cancer patients had very good responses to adavosertib and to identify potential biomarkers of response,” she said.

“Additionally, we plan to investigate whether adavosertib has similar activity in another type of uterine cancer, uterine carcinosarcoma, that shares many similar molecular characteristics with uterine serous carcinoma, including p53 mutations and oncogenic alterations, that might make it similarly vulnerable to targeting Wee1,” she said.

Dr. Liu disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, which supported the trial, as well as Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Liu JF et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 7.

The experimental agent adavosertib showed hints of efficacy against recurrent uterine serous carcinoma in early data from a phase 2 trial.

The overall response rate among 21 patients with advanced uterine serous carcinoma treated with adavosertib monotherapy was 30%, and an additional patient had an unconfirmed response at the time of data cutoff, reported Joyce F. Liu, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues.

“These results were noteworthy for the preliminary response rate of 30% that was observed in the first cohort of patients on this study, especially as, on average, patients on this study had received three prior treatments for their cancer. For us, this was an exciting signal of activity, especially for a targeted therapy used by itself in this type of cancer,” Dr. Liu said in an interview.

Preliminary results of the phase 2 trial were published in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adavosertib is a small molecule that inhibits the Wee1 kinase, a “gatekeeper” of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint that is highly expressed and active in several types of cancer.

“Molecular characterization of these cancers has demonstrated that they have frequent p53 mutations as well as significant alterations in oncogenes,” Dr. Liu said. “These characteristics mean that these are cancers that may both have significant dysregulation of their cell cycle combined with high levels of replication stress. We hypothesized that these cancers could therefore be particularly vulnerable to further dysregulation of the cell cycle, which can be mediated by a drug such as adavosertib, which interrupts regulation of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint by inhibiting the protein Wee1.”

Study details

The study enrolled women with recurrent uterine serous carcinoma. Patients were eligible if any disease component was considered to be serous, except for carcinosarcomas. The patients had a minimum of one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen (median 3, range 1-7), with no upper limit on prior lines of therapy required for eligibility.

Patients with microsatellite high/deficient mismatch repair disease had to have received prior therapy with programmed death-1/ligand-1 inhibitor, or to have been deemed ineligible for immunotherapy with a checkpoint inhibitor.

The patients received adavosertib at 300 mg daily on days 1 through 5 and days 8 through 12 of each 21-day cycle.

The trial would be considered successful if at least of 4 of 35 patients planned for accrual had a confirmed response or if 8 patients were progression free at 6 months. The coprimary endpoints are overall response rate of 20% or more, or a progression-free survival rate at 6 months of 30% or more.

Results and next steps

As of Aug. 20, 2019, the investigators had enrolled 27 patients, of whom 21 were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate was 30%, consisting of six confirmed partial responses. One additional patient had an unconfirmed response. Eleven of the 21 patients had stable disease, and 3 had disease progression.

Eleven patients remained on treatment with adavosertib at the time of data cutoff. Progression-free survival data were not mature.

The most frequent adverse events included anemia and diarrhea in 67% of patients each, nausea in 58%, and fatigue in 50%.

Frequent grade 3 or higher adverse effects included anemia, neutropenia, and syncope, all occurring in 21% of patients.

Dr. Liu said the investigators plan to present updated data from the study at a future meeting.

“We are planning additional cohorts in this study that will allow us to more deeply investigate why certain uterine serous cancer patients had very good responses to adavosertib and to identify potential biomarkers of response,” she said.

“Additionally, we plan to investigate whether adavosertib has similar activity in another type of uterine cancer, uterine carcinosarcoma, that shares many similar molecular characteristics with uterine serous carcinoma, including p53 mutations and oncogenic alterations, that might make it similarly vulnerable to targeting Wee1,” she said.

Dr. Liu disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, which supported the trial, as well as Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Liu JF et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 7.

The experimental agent adavosertib showed hints of efficacy against recurrent uterine serous carcinoma in early data from a phase 2 trial.

The overall response rate among 21 patients with advanced uterine serous carcinoma treated with adavosertib monotherapy was 30%, and an additional patient had an unconfirmed response at the time of data cutoff, reported Joyce F. Liu, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues.

“These results were noteworthy for the preliminary response rate of 30% that was observed in the first cohort of patients on this study, especially as, on average, patients on this study had received three prior treatments for their cancer. For us, this was an exciting signal of activity, especially for a targeted therapy used by itself in this type of cancer,” Dr. Liu said in an interview.

Preliminary results of the phase 2 trial were published in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Adavosertib is a small molecule that inhibits the Wee1 kinase, a “gatekeeper” of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint that is highly expressed and active in several types of cancer.

“Molecular characterization of these cancers has demonstrated that they have frequent p53 mutations as well as significant alterations in oncogenes,” Dr. Liu said. “These characteristics mean that these are cancers that may both have significant dysregulation of their cell cycle combined with high levels of replication stress. We hypothesized that these cancers could therefore be particularly vulnerable to further dysregulation of the cell cycle, which can be mediated by a drug such as adavosertib, which interrupts regulation of the G2-M cell cycle checkpoint by inhibiting the protein Wee1.”

Study details

The study enrolled women with recurrent uterine serous carcinoma. Patients were eligible if any disease component was considered to be serous, except for carcinosarcomas. The patients had a minimum of one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen (median 3, range 1-7), with no upper limit on prior lines of therapy required for eligibility.

Patients with microsatellite high/deficient mismatch repair disease had to have received prior therapy with programmed death-1/ligand-1 inhibitor, or to have been deemed ineligible for immunotherapy with a checkpoint inhibitor.

The patients received adavosertib at 300 mg daily on days 1 through 5 and days 8 through 12 of each 21-day cycle.

The trial would be considered successful if at least of 4 of 35 patients planned for accrual had a confirmed response or if 8 patients were progression free at 6 months. The coprimary endpoints are overall response rate of 20% or more, or a progression-free survival rate at 6 months of 30% or more.

Results and next steps

As of Aug. 20, 2019, the investigators had enrolled 27 patients, of whom 21 were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate was 30%, consisting of six confirmed partial responses. One additional patient had an unconfirmed response. Eleven of the 21 patients had stable disease, and 3 had disease progression.

Eleven patients remained on treatment with adavosertib at the time of data cutoff. Progression-free survival data were not mature.

The most frequent adverse events included anemia and diarrhea in 67% of patients each, nausea in 58%, and fatigue in 50%.

Frequent grade 3 or higher adverse effects included anemia, neutropenia, and syncope, all occurring in 21% of patients.

Dr. Liu said the investigators plan to present updated data from the study at a future meeting.

“We are planning additional cohorts in this study that will allow us to more deeply investigate why certain uterine serous cancer patients had very good responses to adavosertib and to identify potential biomarkers of response,” she said.

“Additionally, we plan to investigate whether adavosertib has similar activity in another type of uterine cancer, uterine carcinosarcoma, that shares many similar molecular characteristics with uterine serous carcinoma, including p53 mutations and oncogenic alterations, that might make it similarly vulnerable to targeting Wee1,” she said.

Dr. Liu disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, which supported the trial, as well as Merck and other companies.

SOURCE: Liu JF et al. SGO 2020, Abstract 7.

FROM SGO 2020

Vascular biomarkers predict pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed pulmonary hypertension (PH) in a prospective cohort of 300 subjects.

However, the associations with PH were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor (PlGF), the sensitivity for future PH was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve (AUC) 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 (sFlt1) – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an AUC of 0.61.

Adding PlGF and sFlt1 elevations to carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and percent forced vital capacity to predict PH increased the AUC modestly, from 0.72 to 0.77.

The data suggest, perhaps, an early warning system for PH. “Once vascular biomarkers are observed to be elevated, the frequency of other screening tests (e.g., NT-proBNP, DLCO) may be increased in a more cost-effective approach,” wrote investigators led by rheumatologist Christopher Mecoli, MD, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“In the end, the authors did not overstate the case and cautiously recommended that using biomarkers might be useful in the future. The finding that when there are increased numbers of abnormalities of vascular markers, there would be an increased probability of pulmonary hypertension, makes sense.” However, “this was a major fishing expedition, and the data are certainly not sufficient to suggest anything clinical but are of some interest with respect to the general hypothesis,” said rheumatologist Daniel Furst, MD, professor of medicine (emeritus) at the University of California, Los Angeles, when asked for comment.

The subjects were followed for at least 5 years and had no evidence of PH at study entry. Levels of P1GF, sFlt-1, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), soluble endoglin, and endostatin were assessed at baseline and at regular intervals thereafter. A total of 46 patients (15%) developed PH after a mean of 3 years.

Risk of PH was associated with baseline elevations of HGF (hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.24-3.17; P = .004); sFlt1 (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.29-7.14; P = .011); and PlGF (HR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.32-5.69; P = .007).

Just 2 of 25 patients (8%) with no biomarkers elevated at baseline developed PH versus 12 of 29 (42%) with all five elevated. That translated to a dose-response relationship, with each additional elevated biomarker increasing the risk of PH by 78% (95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004).

“There [was] no consistent trend of increasing biomarker levels over time as patients approach[ed] a diagnosis of [PH]. ... Serial testing may have value in patients with early disease to first detect elevations in biomarkers,” but “once elevated, the utility of serially monitoring appears low,” the investigators wrote.

It’s not surprising that “a higher number of elevated biomarkers relating to vascular dysfunction would correspond to a higher risk of PH,” the team wrote. However, “while these biomarkers hold promise in the risk stratification of SSc patients, many more vascular molecules exist which may have similar or greater value.”

There was no substantial correlation between any biomarker and disease duration, age at enrollment, or age at diagnosis, and no significant difference in biomarker level based on patient comorbidities. No biomarker was significantly associated with medication use at cohort entry, and none were significantly associated with the risk of ischemic digital lesions.

The majority of patients were white women. At enrollment, the average age was 52 years, and subjects had SSc for a mean of 10 years.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures were not reported.

SOURCE: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Levels of three vascular biomarkers – hepatocyte growth factor, soluble Flt-1, and platelet-derived growth factor – were elevated a mean of 3 years before systemic sclerosis patients developed pulmonary hypertension.

Major finding: The associations with pulmonary hypertension were not very robust. For instance, above an optimal cut point of 9.89 pg/mL for platelet-derived growth factor, the sensitivity for future pulmonary hypertension was 82%, specificity 56%, and area under the curve 0.69. An elevation above the optimal cut point for soluble Flt-1 – 93.8 pg/mL – was 71% specific and 51% sensitive, with an area under the curve of 0.61.

Study details: A prospective cohort of 300 patients

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Investigator disclosures weren’t reported.

Source: Mecoli C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar 21. doi: 10.1002/art.41265.

April 2020 Advances in Multiple Sclerosis Care

Click here to access April 2020 Advances in Multiple Sclerosis Care

Table of Contents

- The Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence: A Model of Excellence in the VA

- The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: A Novel Interactive Database Within the Veterans Health Administration

- Behavioral Interventions in Multiple Sclerosis

- Multiple Sclerosis Medications in the VHA: Delivering Specialty, High-Cost, Pharmacy Care in a National System

- The Future of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Therapies

Click here to access April 2020 Advances in Multiple Sclerosis Care

Table of Contents

- The Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence: A Model of Excellence in the VA

- The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: A Novel Interactive Database Within the Veterans Health Administration

- Behavioral Interventions in Multiple Sclerosis

- Multiple Sclerosis Medications in the VHA: Delivering Specialty, High-Cost, Pharmacy Care in a National System

- The Future of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Therapies

Click here to access April 2020 Advances in Multiple Sclerosis Care

Table of Contents

- The Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence: A Model of Excellence in the VA

- The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: A Novel Interactive Database Within the Veterans Health Administration

- Behavioral Interventions in Multiple Sclerosis

- Multiple Sclerosis Medications in the VHA: Delivering Specialty, High-Cost, Pharmacy Care in a National System

- The Future of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Therapies

VOYAGER PAD: Clopidogrel adds no benefit to rivaroxaban plus aspirin after PAD interventions

The VOYAGER PAD results from more than 6,500 patients created the biggest evidence base by far ever collected from patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) who underwent a vascular intervention, and showed that the combination of twice-daily rivaroxaban and once-daily aspirin was safe and more effective than aspirin alone for reducing future thrombotic and ischemic events.

Following that report on March 28, a prespecified subgroup analysis presented the next day showed that adding clopidogrel to this two-drug combination produced no added efficacy but caused additional bleeding episodes, suggesting that the common practice of using clopidogrel plus aspirin in these patients, especially those who receive a stent in a peripheral artery, should either fall by the wayside or be used very briefly.

“In the absence of clear benefit, clopidogrel exposure along with aspirin and rivaroxaban should be minimized or avoided to reduce this risk,” William R. Hiatt, MD, said at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But he also cautioned that “we did not control for clopidogrel use, and so the patients who received clopidogrel look different [from patients who did not receive clopidogrel]. We must be cautious in interpreting differences between patients on or off clopidogrel,” warned Dr. Hiatt, a lead investigator for VOYAGER PAD, professor for cardiovascular research at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora and president of the affiliated Colorado Prevention Center.

In addition to this substantial caveat, the finding that clopidogrel appeared to add no extra benefit to the rivaroxaban/aspirin regimen “contradicts some dogmas that have been in the field for decades,” Dr. Hiatt said. Use of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in this setting usually aspirin and clopidogrel, in patients who have just undergone lower-extremity revascularization is “current dogma,” even though it is not based on any direct evidence for efficacy, but instead came on the scene as “an extrapolation from the coronary artery literature, where it does have some benefit, particularly after percutaneous coronary intervention,” he explained.

The only reported study results to examine use of DAPT in patients who underwent peripheral artery revascularization focused entirely on patients who had a surgical procedure and showed no added benefit from DAPT over aspirin only in a multicenter, randomized trial with 851 patients (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Oct;52[4]:825-33), Dr. Hiatt noted. In VOYAGER PAD, two-thirds of all patients underwent an endovascular, not surgical, peripheral intervention, and among those treated with clopidogrel, 91% had endovascular treatment.

“We’re not saying don’t use DAPT, but patients on three drugs are at higher bleeding risk than patients on two drugs. I think our data also suggest starting rivaroxaban immediately after a procedure [as was done in VOYAGER PAD], and not waiting to complete a course of DAPT,” Dr. Hiatt said.

Other experts embraced Dr. Hiatt’s take on these findings, while warning that it may take some time for the message to penetrate into practice.

The overall VOYAGER PAD results “are practice changing for vascular interventions; it was by an order of magnitude the largest vascular intervention trial ever conducted,” commented Sahil A. Parikh, MD, a designated discussant, interventional cardiologist, and director of endovascular services at New York–Presbyterian Medical Center. “The data suggest that the value of clopidogrel is questionable, but the added hazard is not questionable” when given to patients on top of rivaroxaban and aspirin. The results “certainly beg the question of whether one should use DAPT at all, and if so, for how long.”

Use of DAPT in patients undergoing peripheral revascularization, especially patients receiving a stent, has been “dogma,” Dr. Parikh agreed. “It’s been pounded into our heads that DAPT is standard care, so it will take some time to penetrate into the practicing community.”

“Could there be patients who could benefit from triple therapy? That’s possible, but it needs testing,” commented Mark A. Creager, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H. “We’ve made terrific strides with the results from VOYAGER PAD,” and from the earlier COMPASS trial, which proved the benefit of rivaroxaban and aspirin in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease including many PAD patients (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). Use of rivaroxaban and aspirin in PAD patients based on the COMPASS results “is beginning to make an impact, but has a long way to go,” Dr. Creager said in an interview.

In late 2018, the Food and Drug Administration gave rivaroxaban a revised labeling that included an indication for patients with PAD based on the COMPASS findings. The VOYAGER PAD and COMPASS trials are especially noteworthy because “they opened a whole area [of study] in patients with peripheral vascular disease, ” he added.

The prespecified analysis that Dr. Hiatt reported analyzed outcomes among the 51% of patients enrolled in VOYAGER PAD (Vascular Outcomes Study of Acetylsalicylic Acid Along With Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for Peripheral Artery Disease) who received clopidogrel during follow-up at the discretion of their treating physician and the outcomes among the remainder who did not. The two subgroups showed several statistically significant differences in the prevalence of various comorbidities and in some baseline demographic and clinical metrics, and the analyses that Dr. Hiatt reported did not attempt to correct for these differences. Patients who received clopidogrel had the drug on board for a median of 29 days, and about 58% received it for 30 days or less.

The main finding of his analysis was that “adding clopidogrel did not modify benefit at all” from the perspective of the primary endpoint of VOYAGER PAD, the incidence of a five-item list of adverse events (acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular cause, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular death) during a median follow-up of 28 months (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000052), said Dr. Hiatt. Among patients on clopidogrel, those treated with both rivaroxaban and aspirin had a 16.0% incidence of the primary endpoint, compared with an 18.3% rate among patients on aspirin only, for a 15% relative risk reduction, identical to the study’s primary result. Among patients not on clopidogrel, the primary endpoint occurred in 18.7% of patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin and in 21.5% of those on aspirin only, a 14% relative risk reduction. The analyses also showed that adding clopidogrel appeared to increase the rate of bleeding episodes, particularly the incidence of major bleeds by the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), which rose among patients on aspirin alone from 3.3% without clopidogrel treatment to 4.9% with clopidogrel, and in patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin these major bleeds increased from 5.4% with no clopidogrel to 6.5% with clopidogrel.

An especially revealing further analysis showed that, among those who also received rivaroxaban and aspirin, clopidogrel treatment for more than 30 days led to substantially more bleeding problems, compared with patients who received the drug for 30 days or less. Patients who received clopidogrel for more than 30 days as part of a triple-drug regimen had a 3.0% rate of major ISTH bleeds during 180 days of follow-up, compared with a 0.9% rate for patients in the aspirin-alone group who also received clopidogrel, a 2.1% between-group difference. In contrast, the difference in major ISTH bleeds between the two treatment arms in the subgroup who received clopidogrel for 30 days or less was 0.7%.

“What’s inarguable is that the course of clopidogrel should be as short as possible, probably not more than 30 days unless there is a real extenuating rationale,” commented designated discussant Gregory Piazza, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

VOYAGER PAD was sponsored by Bayer and Janssen, the companies that market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). The institution that Dr. Hiatt leads has received research funding from Bayer and Janssen and from Amgen. Dr. Parikh has been a consultant to Terumo; has received research funding from Shockwave, Surmodics, and Trireme; has worked on trial monitoring for Boston Scientific and Silk Road; and has had other financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Creager had no disclosures. Dr. Piazza has received research grants from Bayer and Janssen, as well as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Diiachi, EKOS, and Portola, and he has been a consultant to Optum, Pfizer, and Thrombolex.

SOURCE: Hiatt WR et al. ACC 20, Abstract 406-13.

The VOYAGER PAD results from more than 6,500 patients created the biggest evidence base by far ever collected from patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) who underwent a vascular intervention, and showed that the combination of twice-daily rivaroxaban and once-daily aspirin was safe and more effective than aspirin alone for reducing future thrombotic and ischemic events.

Following that report on March 28, a prespecified subgroup analysis presented the next day showed that adding clopidogrel to this two-drug combination produced no added efficacy but caused additional bleeding episodes, suggesting that the common practice of using clopidogrel plus aspirin in these patients, especially those who receive a stent in a peripheral artery, should either fall by the wayside or be used very briefly.

“In the absence of clear benefit, clopidogrel exposure along with aspirin and rivaroxaban should be minimized or avoided to reduce this risk,” William R. Hiatt, MD, said at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But he also cautioned that “we did not control for clopidogrel use, and so the patients who received clopidogrel look different [from patients who did not receive clopidogrel]. We must be cautious in interpreting differences between patients on or off clopidogrel,” warned Dr. Hiatt, a lead investigator for VOYAGER PAD, professor for cardiovascular research at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora and president of the affiliated Colorado Prevention Center.

In addition to this substantial caveat, the finding that clopidogrel appeared to add no extra benefit to the rivaroxaban/aspirin regimen “contradicts some dogmas that have been in the field for decades,” Dr. Hiatt said. Use of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in this setting usually aspirin and clopidogrel, in patients who have just undergone lower-extremity revascularization is “current dogma,” even though it is not based on any direct evidence for efficacy, but instead came on the scene as “an extrapolation from the coronary artery literature, where it does have some benefit, particularly after percutaneous coronary intervention,” he explained.

The only reported study results to examine use of DAPT in patients who underwent peripheral artery revascularization focused entirely on patients who had a surgical procedure and showed no added benefit from DAPT over aspirin only in a multicenter, randomized trial with 851 patients (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Oct;52[4]:825-33), Dr. Hiatt noted. In VOYAGER PAD, two-thirds of all patients underwent an endovascular, not surgical, peripheral intervention, and among those treated with clopidogrel, 91% had endovascular treatment.

“We’re not saying don’t use DAPT, but patients on three drugs are at higher bleeding risk than patients on two drugs. I think our data also suggest starting rivaroxaban immediately after a procedure [as was done in VOYAGER PAD], and not waiting to complete a course of DAPT,” Dr. Hiatt said.

Other experts embraced Dr. Hiatt’s take on these findings, while warning that it may take some time for the message to penetrate into practice.

The overall VOYAGER PAD results “are practice changing for vascular interventions; it was by an order of magnitude the largest vascular intervention trial ever conducted,” commented Sahil A. Parikh, MD, a designated discussant, interventional cardiologist, and director of endovascular services at New York–Presbyterian Medical Center. “The data suggest that the value of clopidogrel is questionable, but the added hazard is not questionable” when given to patients on top of rivaroxaban and aspirin. The results “certainly beg the question of whether one should use DAPT at all, and if so, for how long.”

Use of DAPT in patients undergoing peripheral revascularization, especially patients receiving a stent, has been “dogma,” Dr. Parikh agreed. “It’s been pounded into our heads that DAPT is standard care, so it will take some time to penetrate into the practicing community.”

“Could there be patients who could benefit from triple therapy? That’s possible, but it needs testing,” commented Mark A. Creager, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H. “We’ve made terrific strides with the results from VOYAGER PAD,” and from the earlier COMPASS trial, which proved the benefit of rivaroxaban and aspirin in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease including many PAD patients (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). Use of rivaroxaban and aspirin in PAD patients based on the COMPASS results “is beginning to make an impact, but has a long way to go,” Dr. Creager said in an interview.

In late 2018, the Food and Drug Administration gave rivaroxaban a revised labeling that included an indication for patients with PAD based on the COMPASS findings. The VOYAGER PAD and COMPASS trials are especially noteworthy because “they opened a whole area [of study] in patients with peripheral vascular disease, ” he added.

The prespecified analysis that Dr. Hiatt reported analyzed outcomes among the 51% of patients enrolled in VOYAGER PAD (Vascular Outcomes Study of Acetylsalicylic Acid Along With Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for Peripheral Artery Disease) who received clopidogrel during follow-up at the discretion of their treating physician and the outcomes among the remainder who did not. The two subgroups showed several statistically significant differences in the prevalence of various comorbidities and in some baseline demographic and clinical metrics, and the analyses that Dr. Hiatt reported did not attempt to correct for these differences. Patients who received clopidogrel had the drug on board for a median of 29 days, and about 58% received it for 30 days or less.

The main finding of his analysis was that “adding clopidogrel did not modify benefit at all” from the perspective of the primary endpoint of VOYAGER PAD, the incidence of a five-item list of adverse events (acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular cause, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular death) during a median follow-up of 28 months (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000052), said Dr. Hiatt. Among patients on clopidogrel, those treated with both rivaroxaban and aspirin had a 16.0% incidence of the primary endpoint, compared with an 18.3% rate among patients on aspirin only, for a 15% relative risk reduction, identical to the study’s primary result. Among patients not on clopidogrel, the primary endpoint occurred in 18.7% of patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin and in 21.5% of those on aspirin only, a 14% relative risk reduction. The analyses also showed that adding clopidogrel appeared to increase the rate of bleeding episodes, particularly the incidence of major bleeds by the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), which rose among patients on aspirin alone from 3.3% without clopidogrel treatment to 4.9% with clopidogrel, and in patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin these major bleeds increased from 5.4% with no clopidogrel to 6.5% with clopidogrel.

An especially revealing further analysis showed that, among those who also received rivaroxaban and aspirin, clopidogrel treatment for more than 30 days led to substantially more bleeding problems, compared with patients who received the drug for 30 days or less. Patients who received clopidogrel for more than 30 days as part of a triple-drug regimen had a 3.0% rate of major ISTH bleeds during 180 days of follow-up, compared with a 0.9% rate for patients in the aspirin-alone group who also received clopidogrel, a 2.1% between-group difference. In contrast, the difference in major ISTH bleeds between the two treatment arms in the subgroup who received clopidogrel for 30 days or less was 0.7%.

“What’s inarguable is that the course of clopidogrel should be as short as possible, probably not more than 30 days unless there is a real extenuating rationale,” commented designated discussant Gregory Piazza, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

VOYAGER PAD was sponsored by Bayer and Janssen, the companies that market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). The institution that Dr. Hiatt leads has received research funding from Bayer and Janssen and from Amgen. Dr. Parikh has been a consultant to Terumo; has received research funding from Shockwave, Surmodics, and Trireme; has worked on trial monitoring for Boston Scientific and Silk Road; and has had other financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Creager had no disclosures. Dr. Piazza has received research grants from Bayer and Janssen, as well as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Diiachi, EKOS, and Portola, and he has been a consultant to Optum, Pfizer, and Thrombolex.

SOURCE: Hiatt WR et al. ACC 20, Abstract 406-13.

The VOYAGER PAD results from more than 6,500 patients created the biggest evidence base by far ever collected from patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD) who underwent a vascular intervention, and showed that the combination of twice-daily rivaroxaban and once-daily aspirin was safe and more effective than aspirin alone for reducing future thrombotic and ischemic events.

Following that report on March 28, a prespecified subgroup analysis presented the next day showed that adding clopidogrel to this two-drug combination produced no added efficacy but caused additional bleeding episodes, suggesting that the common practice of using clopidogrel plus aspirin in these patients, especially those who receive a stent in a peripheral artery, should either fall by the wayside or be used very briefly.

“In the absence of clear benefit, clopidogrel exposure along with aspirin and rivaroxaban should be minimized or avoided to reduce this risk,” William R. Hiatt, MD, said at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But he also cautioned that “we did not control for clopidogrel use, and so the patients who received clopidogrel look different [from patients who did not receive clopidogrel]. We must be cautious in interpreting differences between patients on or off clopidogrel,” warned Dr. Hiatt, a lead investigator for VOYAGER PAD, professor for cardiovascular research at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora and president of the affiliated Colorado Prevention Center.

In addition to this substantial caveat, the finding that clopidogrel appeared to add no extra benefit to the rivaroxaban/aspirin regimen “contradicts some dogmas that have been in the field for decades,” Dr. Hiatt said. Use of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), in this setting usually aspirin and clopidogrel, in patients who have just undergone lower-extremity revascularization is “current dogma,” even though it is not based on any direct evidence for efficacy, but instead came on the scene as “an extrapolation from the coronary artery literature, where it does have some benefit, particularly after percutaneous coronary intervention,” he explained.

The only reported study results to examine use of DAPT in patients who underwent peripheral artery revascularization focused entirely on patients who had a surgical procedure and showed no added benefit from DAPT over aspirin only in a multicenter, randomized trial with 851 patients (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Oct;52[4]:825-33), Dr. Hiatt noted. In VOYAGER PAD, two-thirds of all patients underwent an endovascular, not surgical, peripheral intervention, and among those treated with clopidogrel, 91% had endovascular treatment.

“We’re not saying don’t use DAPT, but patients on three drugs are at higher bleeding risk than patients on two drugs. I think our data also suggest starting rivaroxaban immediately after a procedure [as was done in VOYAGER PAD], and not waiting to complete a course of DAPT,” Dr. Hiatt said.

Other experts embraced Dr. Hiatt’s take on these findings, while warning that it may take some time for the message to penetrate into practice.

The overall VOYAGER PAD results “are practice changing for vascular interventions; it was by an order of magnitude the largest vascular intervention trial ever conducted,” commented Sahil A. Parikh, MD, a designated discussant, interventional cardiologist, and director of endovascular services at New York–Presbyterian Medical Center. “The data suggest that the value of clopidogrel is questionable, but the added hazard is not questionable” when given to patients on top of rivaroxaban and aspirin. The results “certainly beg the question of whether one should use DAPT at all, and if so, for how long.”

Use of DAPT in patients undergoing peripheral revascularization, especially patients receiving a stent, has been “dogma,” Dr. Parikh agreed. “It’s been pounded into our heads that DAPT is standard care, so it will take some time to penetrate into the practicing community.”

“Could there be patients who could benefit from triple therapy? That’s possible, but it needs testing,” commented Mark A. Creager, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H. “We’ve made terrific strides with the results from VOYAGER PAD,” and from the earlier COMPASS trial, which proved the benefit of rivaroxaban and aspirin in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease including many PAD patients (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30). Use of rivaroxaban and aspirin in PAD patients based on the COMPASS results “is beginning to make an impact, but has a long way to go,” Dr. Creager said in an interview.

In late 2018, the Food and Drug Administration gave rivaroxaban a revised labeling that included an indication for patients with PAD based on the COMPASS findings. The VOYAGER PAD and COMPASS trials are especially noteworthy because “they opened a whole area [of study] in patients with peripheral vascular disease, ” he added.

The prespecified analysis that Dr. Hiatt reported analyzed outcomes among the 51% of patients enrolled in VOYAGER PAD (Vascular Outcomes Study of Acetylsalicylic Acid Along With Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for Peripheral Artery Disease) who received clopidogrel during follow-up at the discretion of their treating physician and the outcomes among the remainder who did not. The two subgroups showed several statistically significant differences in the prevalence of various comorbidities and in some baseline demographic and clinical metrics, and the analyses that Dr. Hiatt reported did not attempt to correct for these differences. Patients who received clopidogrel had the drug on board for a median of 29 days, and about 58% received it for 30 days or less.

The main finding of his analysis was that “adding clopidogrel did not modify benefit at all” from the perspective of the primary endpoint of VOYAGER PAD, the incidence of a five-item list of adverse events (acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular cause, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular death) during a median follow-up of 28 months (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000052), said Dr. Hiatt. Among patients on clopidogrel, those treated with both rivaroxaban and aspirin had a 16.0% incidence of the primary endpoint, compared with an 18.3% rate among patients on aspirin only, for a 15% relative risk reduction, identical to the study’s primary result. Among patients not on clopidogrel, the primary endpoint occurred in 18.7% of patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin and in 21.5% of those on aspirin only, a 14% relative risk reduction. The analyses also showed that adding clopidogrel appeared to increase the rate of bleeding episodes, particularly the incidence of major bleeds by the criteria of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), which rose among patients on aspirin alone from 3.3% without clopidogrel treatment to 4.9% with clopidogrel, and in patients on rivaroxaban plus aspirin these major bleeds increased from 5.4% with no clopidogrel to 6.5% with clopidogrel.

An especially revealing further analysis showed that, among those who also received rivaroxaban and aspirin, clopidogrel treatment for more than 30 days led to substantially more bleeding problems, compared with patients who received the drug for 30 days or less. Patients who received clopidogrel for more than 30 days as part of a triple-drug regimen had a 3.0% rate of major ISTH bleeds during 180 days of follow-up, compared with a 0.9% rate for patients in the aspirin-alone group who also received clopidogrel, a 2.1% between-group difference. In contrast, the difference in major ISTH bleeds between the two treatment arms in the subgroup who received clopidogrel for 30 days or less was 0.7%.

“What’s inarguable is that the course of clopidogrel should be as short as possible, probably not more than 30 days unless there is a real extenuating rationale,” commented designated discussant Gregory Piazza, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

VOYAGER PAD was sponsored by Bayer and Janssen, the companies that market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). The institution that Dr. Hiatt leads has received research funding from Bayer and Janssen and from Amgen. Dr. Parikh has been a consultant to Terumo; has received research funding from Shockwave, Surmodics, and Trireme; has worked on trial monitoring for Boston Scientific and Silk Road; and has had other financial relationships with Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Creager had no disclosures. Dr. Piazza has received research grants from Bayer and Janssen, as well as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Diiachi, EKOS, and Portola, and he has been a consultant to Optum, Pfizer, and Thrombolex.

SOURCE: Hiatt WR et al. ACC 20, Abstract 406-13.

FROM ACC 2020

COVID-19: Mental health pros come to the aid of frontline comrades

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers across North America are dealing with unprecedented stress, but mental health therapists in both Canada and the US are doing their part to ensure the psychological well-being of their colleagues on the frontlines of the pandemic.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of licensed psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers have signed up to offer free therapy sessions to healthcare professionals who find themselves psychologically overwhelmed by the pandemic’s economic, social, and financial fallout.

In Canada, the movement was started by Toronto psychotherapist Karen Dougherty, MA, who saw a social media post from someone in New York asking mental health workers to volunteer their time.

Inspired by this, Dougherty reached out to some of her close colleagues with a social media post of her own. A few days later, 450 people had signed up to volunteer and Ontario COVID-19 Therapists was born.

The sessions are provided by licensed Canadian psychotherapists and are free of charge to healthcare workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. After signing up online, users can choose from one of three therapists who will provide up to five free phone sessions.

In New York state, a similar initiative — which is not limited to healthcare workers — has gained incredible momentum. On March 21, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the creation of a statewide hotline [844-863-9314] to provide free mental health services to individuals sheltering at home who may be experiencing stress and anxiety as a result of COVID-19.

The governor called on mental-health professionals to volunteer their time and provide telephone and/or telehealth counseling. The New York State Psychiatric Association quickly got on board and encouraged its members to participate.

Just four days later, more than 6,000 mental health workers had volunteered their services, making New York the first state to address the mental health consequences of the pandemic in this way.

Self-care is vital for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as stress mounts and workdays become longer and grimmer. Dougherty recommended that frontline workers manage overwhelming thoughts by limiting their intake of information about the virus.

Self-Care a “Selfless Act”

Clinicians need to balance the need to stay informed with the potential for information overload, which can contribute to anxiety, she said.

She also recommended that individuals continue to connect with loved ones while practicing social distancing. Equally important is talking to someone about the struggles people may be facing at work.

For Amin Azzam MD, MA, the benefits of these initiatives are obvious.

“There is always value in providing additional mental health services and tending to psychological well-being,” Azzam, adjunct professor of psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and UC Berkeley, told Medscape Medical News.

“If there ever were a time when we can use all the emotional support possible, then it would be during a global pandemic,” added Azzam, who is also director of Open Learning Initiatives at Osmosis, a nonprofit health education company.

Azzam urged healthcare professionals to avail themselves of such resources as often as necessary.

“Taking care of ourselves is not a selfish act. When the oxygen masks come down on airplanes we are always instructed to put our own masks on first before helping those in need. It’s a sign of strength, not weakness, to seek emotional support,” he said.

However, it isn’t always easy. The longstanding stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues has not stopped for COVID-19. Even workers who are in close daily contact with people infected with the virus are finding they’re not immune to the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment, Azzam added.

“Nevertheless, the burden these frontline workers are facing is real…and often crushing. Some Ontario doctors have reported pretraumatic stress disorder, which they attribute to having watched the virus wreak havoc in other countries, and knowing that similar difficulties are headed their way,” he said.

A Growing Movement

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, the CEO of Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), said the province’s nurses are under intense pressure at work, then fear infecting family members once they come home. Some are even staying at hotels to ensure they don’t infect others, as reported by CBC News.

However, she added, most recognize the important role that psychotherapy can play, especially since many frontline healthcare workers find it difficult to speak with their families about the issues they face at work, for fear of adding stress to their family life as well.

“None of us are superhuman and immune to stress. When healthcare workers are facing workplace challenges never before seen in their lifetimes, they need opportunities to decompress to maintain their own health and well-being. This will help them pace themselves for the marathon — not sprint — to continue doing the important work of helping others,” said Azzam.

Given the attention it has garnered in such a short time, Azzam is hopeful that the free therapy movement will spread.

In Canada, mental health professionals in other provinces have already reached out to Dougherty, lending credence to the notion of a pan-Canadian network of therapists offering free services to healthcare workers during the outbreak.

In the US, other local initiatives are already underway.

“The one that I’m personally aware of is at my home institution at the University of California, San Francisco,” Azzam said. “We have a Care for the Caregiver program that is being greatly expanded at this time. As part of that initiative, the institution’s psychiatry department has solicited licensed mental health care providers to volunteer their time to provide those additional services.”

Azzam has also worked with colleagues developing a series of mental health tools that Osmosis has made available free of charge.

These include a central site with educational material about COVID-19, a video about supporting educators’ mental health during high-stress periods; a video about managing students’ mental health during public health emergencies; a summary of recommended resources for psychological health in distressing times; and a YouTube Live event he held regarding tips for maximizing psychological health during stressful times.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

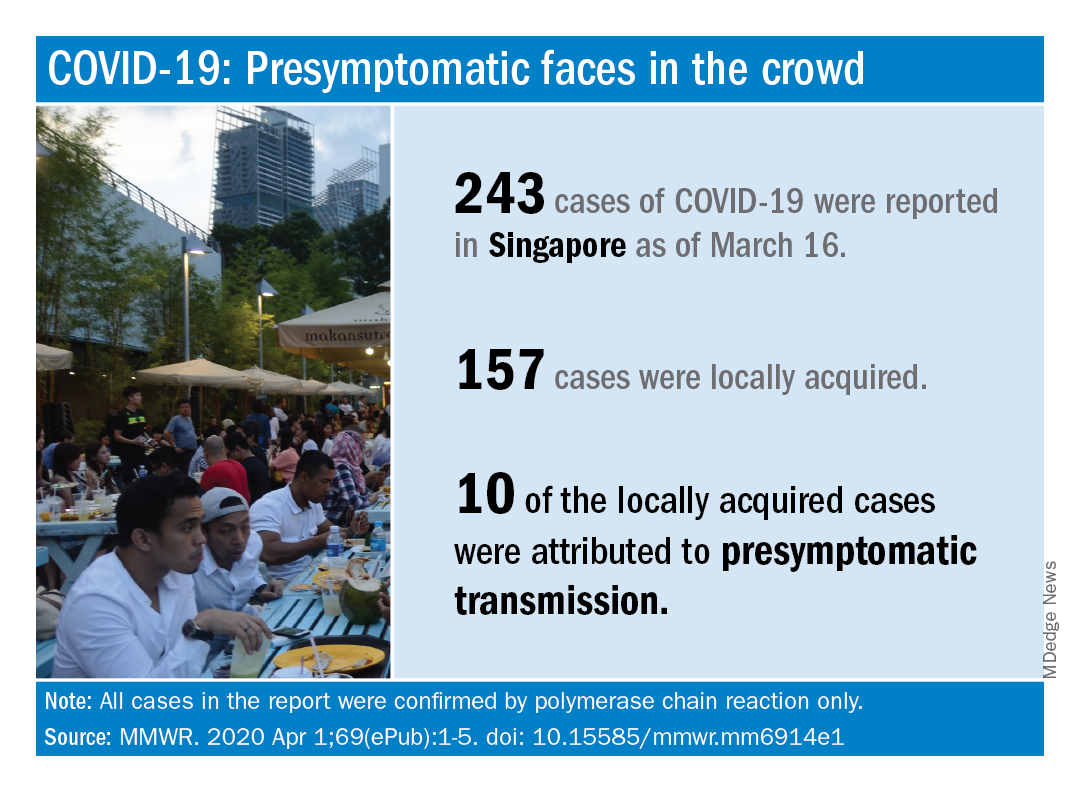

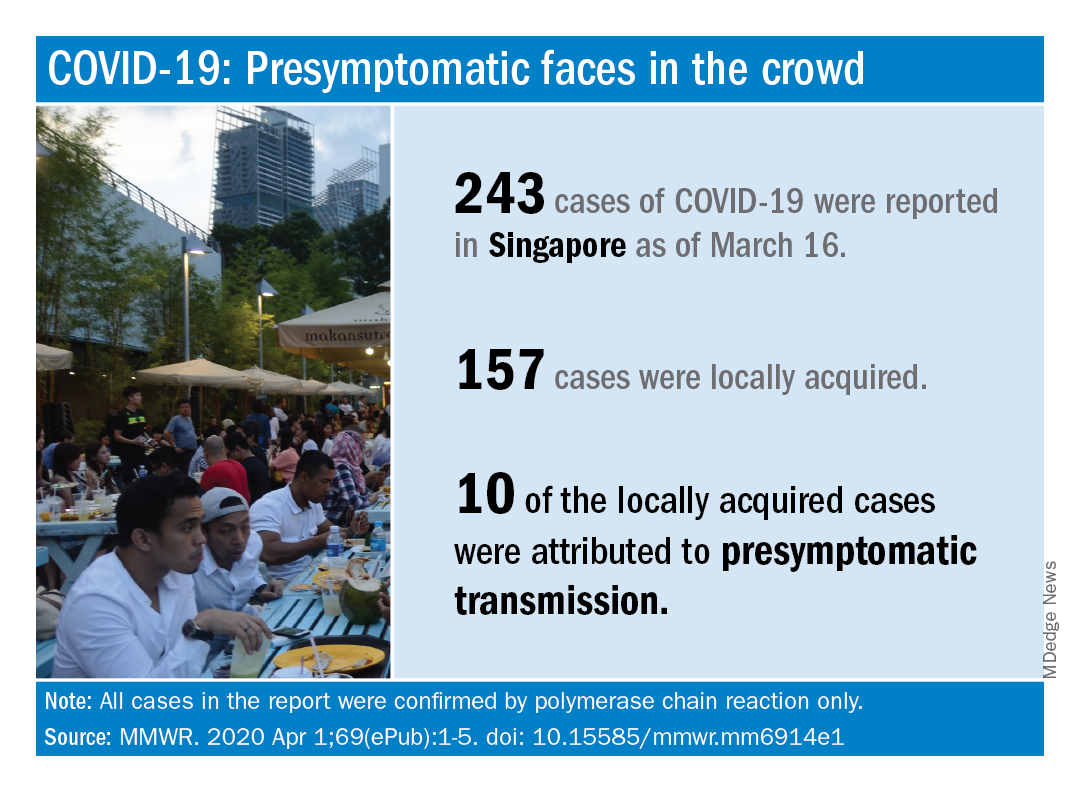

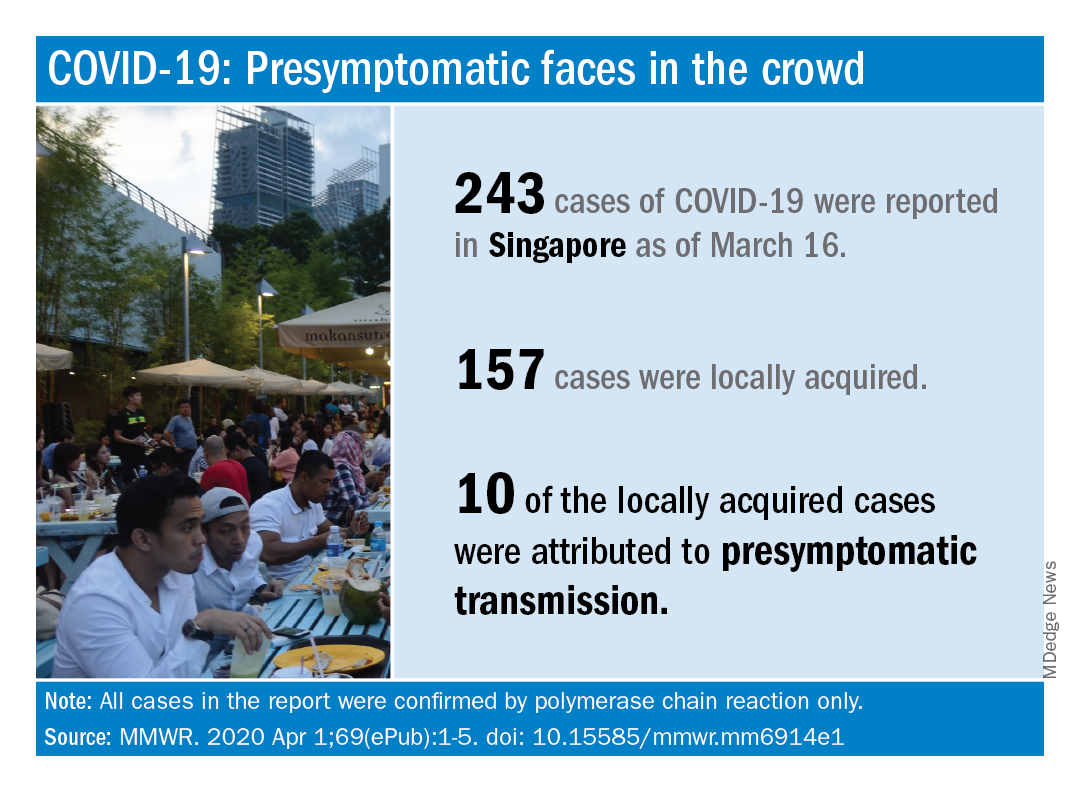

COVID-19 transmission can occur before symptom onset

based on clinical and epidemiologic data for all cases reported in the country by March 16.

As of that date, there had been 243 cases of COVID-19, of which 157 were locally acquired. Among those 157 were 10 cases (6.4%) that involved probable presymptomatic transmission, Wycliffe E. Wei, MPH, and associates said April 1 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

They defined presymptomatic transmission “as the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected person (source patient) to a secondary patient before the source patient developed symptoms, as ascertained by exposure and symptom onset dates, with no evidence that the secondary patient had been exposed to anyone else with COVID-19.”

Investigation of all 243 cases in Singapore identified seven clusters, each involving two to five patients, as sources of presymptomatic transmission. In four of the clusters, the “exposure occurred 1-3 days before the source patient developed symptoms,” said Mr. Wei of the Singapore Ministry of Health and associates.

These findings, along with evidence from Chinese studies – one of which reported presymptomatic transmission in 12.6% of cases – support “the likelihood that viral shedding can occur in the absence of symptoms and before symptom onset,” they said.

SOURCE: Wei WE et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 1;69(ePub):1-5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1.

based on clinical and epidemiologic data for all cases reported in the country by March 16.

As of that date, there had been 243 cases of COVID-19, of which 157 were locally acquired. Among those 157 were 10 cases (6.4%) that involved probable presymptomatic transmission, Wycliffe E. Wei, MPH, and associates said April 1 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

They defined presymptomatic transmission “as the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected person (source patient) to a secondary patient before the source patient developed symptoms, as ascertained by exposure and symptom onset dates, with no evidence that the secondary patient had been exposed to anyone else with COVID-19.”

Investigation of all 243 cases in Singapore identified seven clusters, each involving two to five patients, as sources of presymptomatic transmission. In four of the clusters, the “exposure occurred 1-3 days before the source patient developed symptoms,” said Mr. Wei of the Singapore Ministry of Health and associates.

These findings, along with evidence from Chinese studies – one of which reported presymptomatic transmission in 12.6% of cases – support “the likelihood that viral shedding can occur in the absence of symptoms and before symptom onset,” they said.

SOURCE: Wei WE et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 1;69(ePub):1-5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1.

based on clinical and epidemiologic data for all cases reported in the country by March 16.

As of that date, there had been 243 cases of COVID-19, of which 157 were locally acquired. Among those 157 were 10 cases (6.4%) that involved probable presymptomatic transmission, Wycliffe E. Wei, MPH, and associates said April 1 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

They defined presymptomatic transmission “as the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected person (source patient) to a secondary patient before the source patient developed symptoms, as ascertained by exposure and symptom onset dates, with no evidence that the secondary patient had been exposed to anyone else with COVID-19.”