User login

Group Clinic for Chemoprevention of Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Pilot Study

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

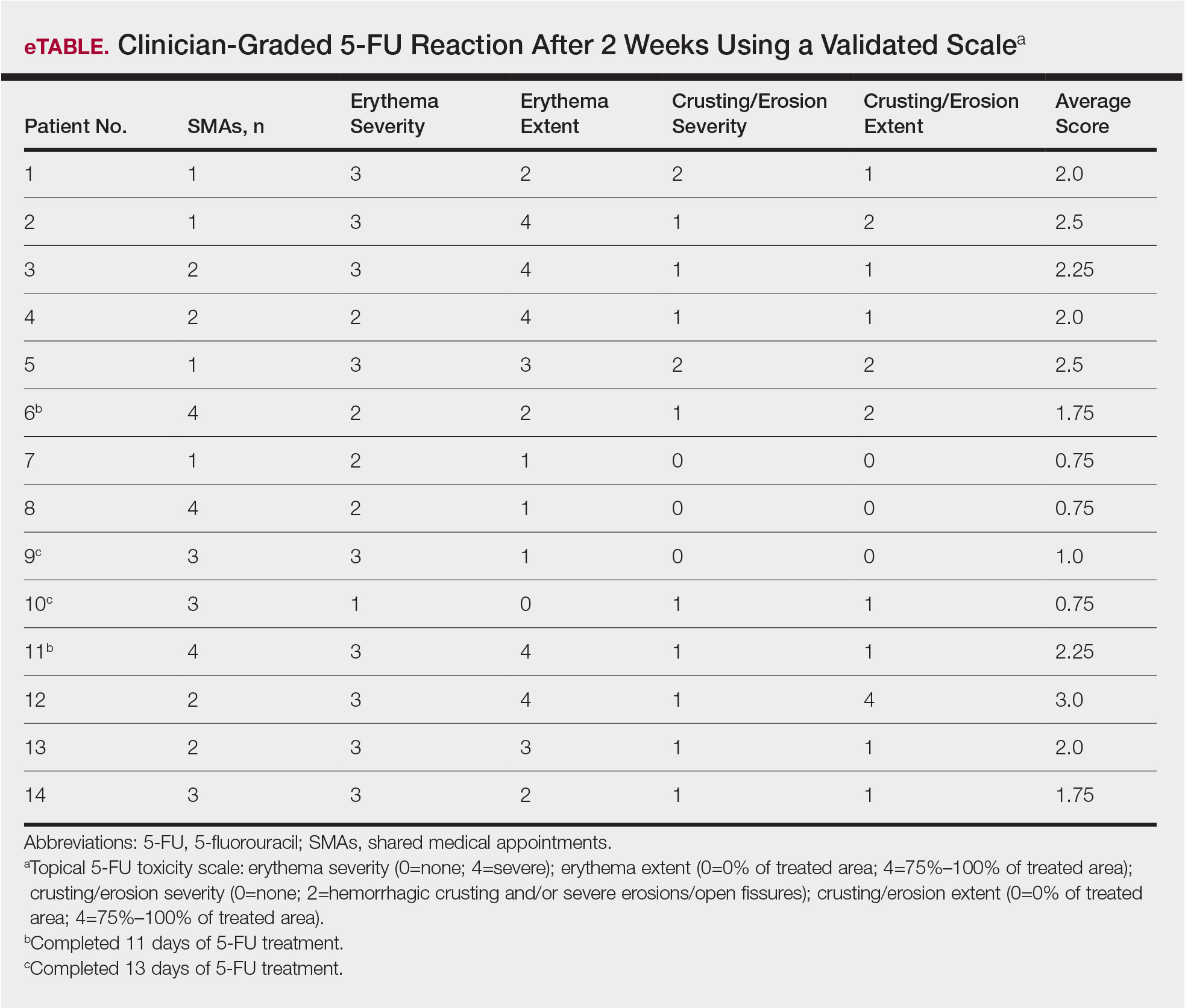

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

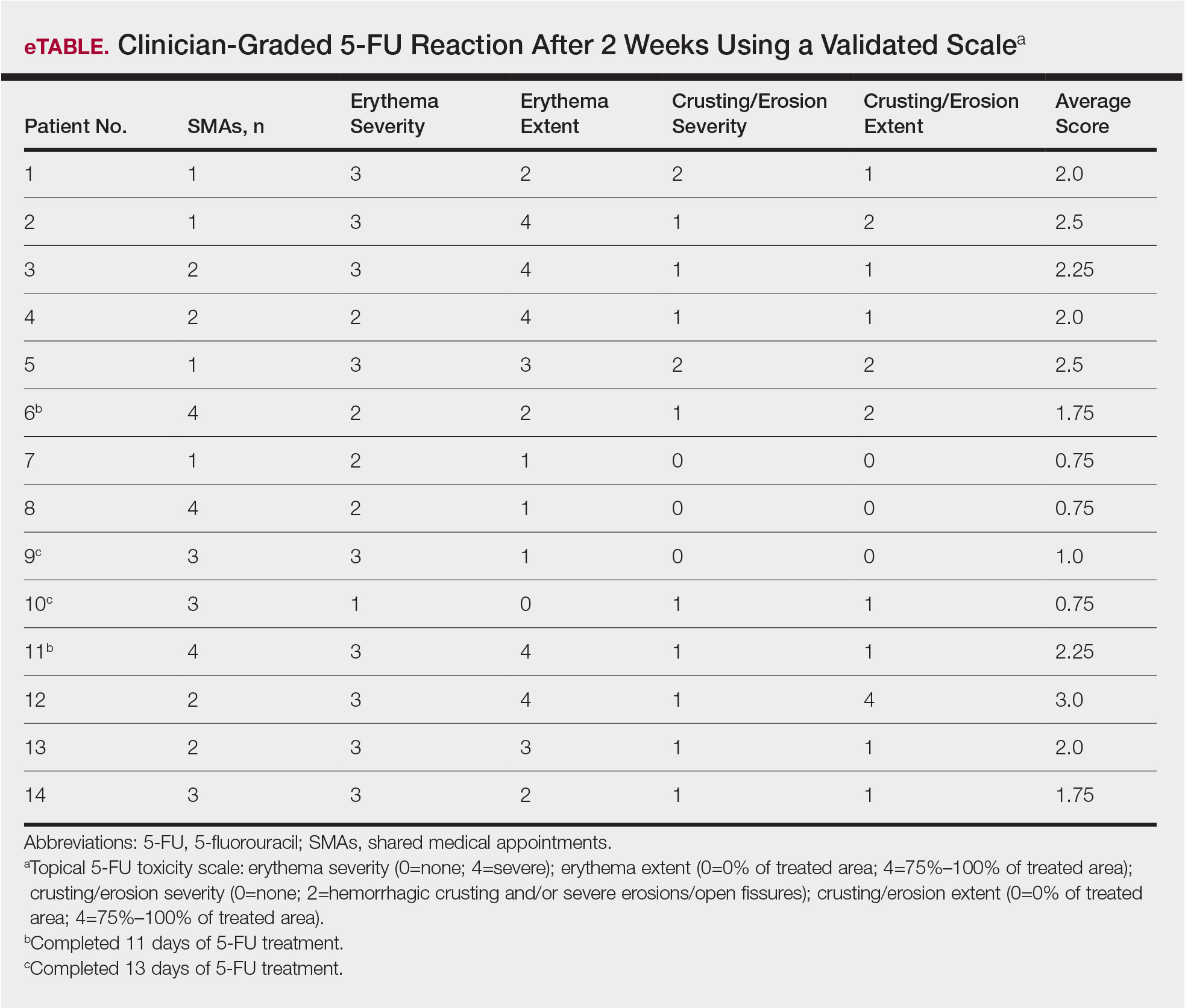

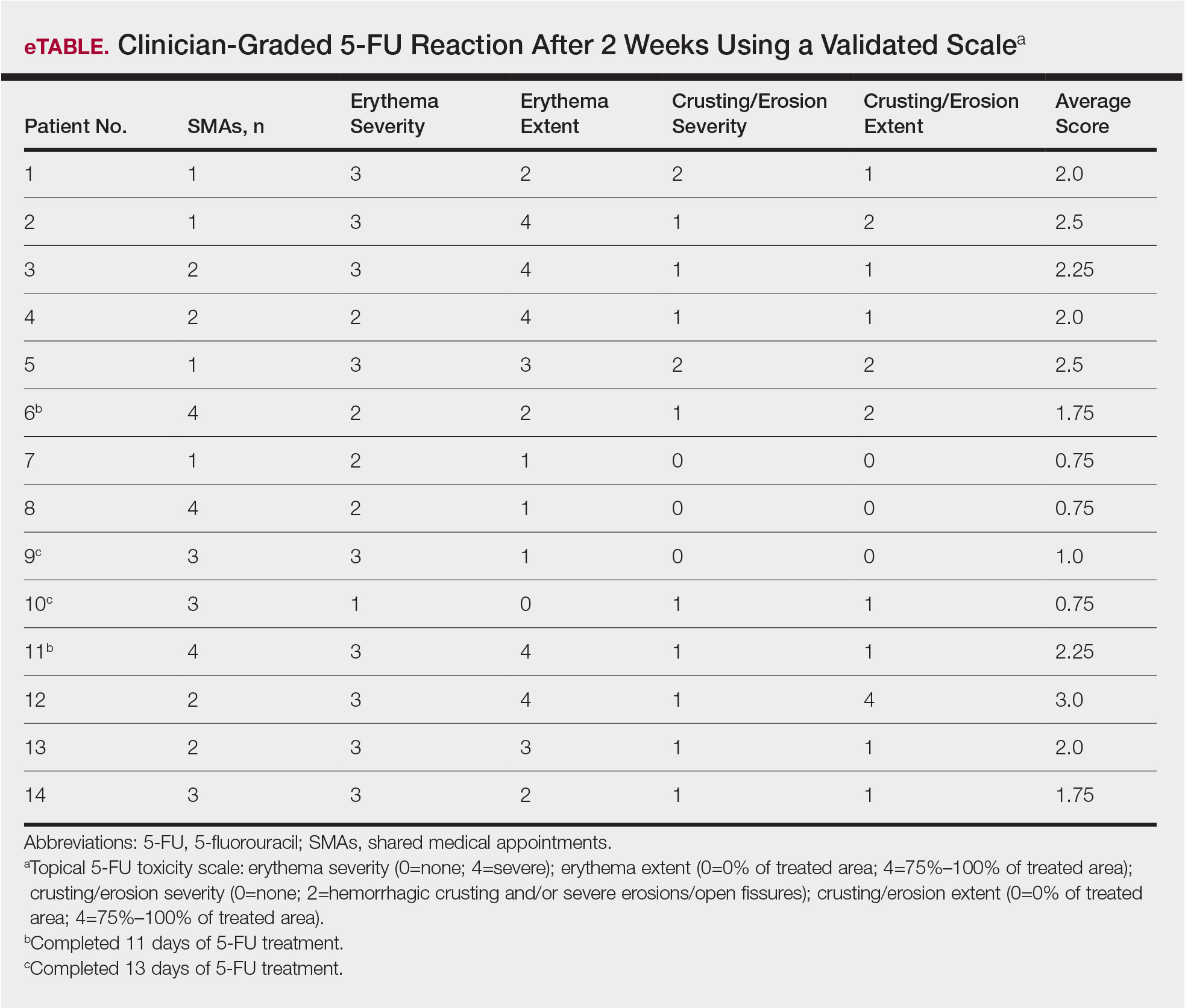

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

Practice Points

- Shared medical appointments (SMAs) enhance patient experience with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment of actinic keratosis (AK).

- Dermatologists should consider utilizing the SMA model for their patients being treated with 5-FU, as patients demonstrated a positive emotional response to 5-FU therapy in the group clinic setting.

What’s Eating You? Bark Scorpions (Centruroides exilicauda and Centruroides sculpturatus)

Epidemiology and Identification

Centruroides is a common genus of bark scorpions in the United States with at least 21 species considered to be medically important, including the closely related Centruroides exilicauda and Centruroides sculpturatus.1 Scorpions can be recognized by a bulbous sac and pointed stinger at the end of a tail-like abdomen. They also have long lobsterlike pedipalps (pincers) for grasping their prey. Identifying characteristics for C exilicauda and C sculpturatus include a small, slender, yellow to light brown or tan body typically measuring 1.3 to 7.6 cm in length with a subaculear tooth or tubercle at the base of the stinger, a characteristic that is common to all Centruroides species (Figure).2 Some variability in size has been shown, with smaller scorpions found in increased elevations and cooler temperatures.1,3 Both C exilicauda and C sculpturatus are found in northern Mexico as well as the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, California, Nevada).1 They have a preference for residing in or around trees and often are found on the underside of bark, stones, or tables as well as inside shoes or small cracks and crevices. Scorpions typically sting in self-defense, and stings commonly occur when humans attempt to move tables, put on shoes, or walk barefoot in scorpion-infested areas. Most stings occur from the end of spring through the end summer, but many may go unreported.1,4

The venom of the Centruroides genus includes peptides and proteins that play a fundamental role in toxic activity by impairing potassium, sodium, and calcium ion channels.1,3 Toxins have been shown to be species specific, functioning either in capturing prey or deterring predators. Intraspecies variability in toxins has been demonstrated, which may complicate the production of adequate antivenin.3 Many have thought that C exilicauda Wood and C sculpturatus Ewing are the same species, and the names have been used synonymously in the past; however, genetic and biochemical studies of their venom components have shown that they are distinct species and that C sculpturatus is the more dangerous of the two.5 The median lethal dose 50% of C sculpturatus was found to be 22.7 μg in CD1 mice.6

Envenomation and Clinical Manifestations

Stings from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus have been shown to cause fatality in children more often than in adults.7 In the United States, Arizona has the highest frequency of serious symptoms of envenomation as well as the highest hospital and intensive care unit admission rates.6 Envenomation results in an immediate sharp burning pain followed by numbness.4 Wounds can produce some regional lymph node swelling, ecchymosis, paresthesia, and lymphangitis. More often than not, however, wounds have little to no inflammation and are characterized only by pain.4 The puncture wound is too small to be seen, and C exilicauda and C sculpturatus venom do not cause local tissue destruction, an important factor in distinguishing it from other scorpion envenomations.

More severe complications that may follow are caused by the neurotoxin released by Centruroides stings. The toxin components can increase the duration and amplitude of the neuronal action potential and enhance the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine.8 Stings can lead to cranial nerve dysfunction and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction as well as autonomic dysfunction, specifically salivation, fever, tongue and muscle fasciculations, opsoclonus, vomiting, bronchoconstriction, diaphoresis, nystagmus, blurred vision, slurred speech, hypertension, rhabdomyolysis, stridor, wheezing, aspiration, anaphylaxis, and tachycardia, leading to cardiac and respiratory compromise.4,8 Some patients have experienced a decreased sense of smell or hearing and decreased fine motor movements.7 Although pancreatitis may occur with scorpion stings, it is not common for C exilicauda.9 Comorbidities such as cardiac disease and substance use disorders contribute to prolonged length of hospital stay and poor outcome.8

Treatment

Most Centruroides stings can be managed at home, but patients with more serious symptoms and children younger than 2 years should be taken to a hospital for treatment.7 If a patient reports only pain but shows no other signs of neurotoxicity, observation and pain relief with rest, ice, and elevation is appropriate management. Patients with severe manifestations have been treated with various combinations of lorazepam, glycopyrrolate, ipratropium bromide, and ondansetron, but the only treatment definitively shown to decrease time to symptom abatement is antivenin.7 It has been demonstrated that C exilicauda and C sculpturatus antivenin is relatively safe.7 Most patients, especially adults, do not die from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus stings; therefore, antivenin more commonly is symptom abating than it is lifesaving.10 In children, time to symptom resolution was decreased to fewer than 4 hours with antivenin, and there is a lower rate of inpatient admission when antivenin is administered.4,10,11 There is a low incidence of anaphylactic reaction after antivenin, but there have been reported cases of self-limited serum sickness after antivenin use that generally can be managed with antihistamines and corticosteroids.4,7

- Gonzalez-Santillan E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Tropica. 2018;187:264-274.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Carcamo-Noriega EN, Olamendi-Portugal T, Restano-Cassulini R, et al. Intraspecific variation of Centruroides sculpturatus scorpion venom from two regions of Arizona. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;638:52-57.

- Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US Poison Control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165.

- Valdez-Cruz N, Dávila S, Licea A, et al. Biochemical, genetic and physiological characterization of venom components from two species of scorpions: Centruroides exilicauda Wood and Centruroides sculpturatus Ewing. Biochimie. 2004;86:387-396.

- Jiménez-Vargas JM, Quintero-Hernández V, Gonzáles-Morales L, et al. Design and expression of recombinant toxins from Mexican scorpions of the genus Centruroides for production of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2017;128:5-14.

- Hurst NB, Lipe DN, Karpen SR, et al. Centruroides sculpturatus envenomation in three adult patients requiring treatment with antivenom. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:294-296.

- O’Connor A, Padilla-Jones A, Ruha A. Severe bark scorpion envenomation in adults. Clin Toxicol. 2018;56:170-174.

- Berg R, Tarantino M. Envenomation by the scorpion Centruroides exilicauda (C sculpturatus): severe and unusual manifestations. Pediatrics. 1991;87:930-933.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Rodrigo C, Gnanathasan A. Management of scorpion envenoming: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Syst Rev. 2017;6:74.

Epidemiology and Identification

Centruroides is a common genus of bark scorpions in the United States with at least 21 species considered to be medically important, including the closely related Centruroides exilicauda and Centruroides sculpturatus.1 Scorpions can be recognized by a bulbous sac and pointed stinger at the end of a tail-like abdomen. They also have long lobsterlike pedipalps (pincers) for grasping their prey. Identifying characteristics for C exilicauda and C sculpturatus include a small, slender, yellow to light brown or tan body typically measuring 1.3 to 7.6 cm in length with a subaculear tooth or tubercle at the base of the stinger, a characteristic that is common to all Centruroides species (Figure).2 Some variability in size has been shown, with smaller scorpions found in increased elevations and cooler temperatures.1,3 Both C exilicauda and C sculpturatus are found in northern Mexico as well as the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, California, Nevada).1 They have a preference for residing in or around trees and often are found on the underside of bark, stones, or tables as well as inside shoes or small cracks and crevices. Scorpions typically sting in self-defense, and stings commonly occur when humans attempt to move tables, put on shoes, or walk barefoot in scorpion-infested areas. Most stings occur from the end of spring through the end summer, but many may go unreported.1,4

The venom of the Centruroides genus includes peptides and proteins that play a fundamental role in toxic activity by impairing potassium, sodium, and calcium ion channels.1,3 Toxins have been shown to be species specific, functioning either in capturing prey or deterring predators. Intraspecies variability in toxins has been demonstrated, which may complicate the production of adequate antivenin.3 Many have thought that C exilicauda Wood and C sculpturatus Ewing are the same species, and the names have been used synonymously in the past; however, genetic and biochemical studies of their venom components have shown that they are distinct species and that C sculpturatus is the more dangerous of the two.5 The median lethal dose 50% of C sculpturatus was found to be 22.7 μg in CD1 mice.6

Envenomation and Clinical Manifestations

Stings from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus have been shown to cause fatality in children more often than in adults.7 In the United States, Arizona has the highest frequency of serious symptoms of envenomation as well as the highest hospital and intensive care unit admission rates.6 Envenomation results in an immediate sharp burning pain followed by numbness.4 Wounds can produce some regional lymph node swelling, ecchymosis, paresthesia, and lymphangitis. More often than not, however, wounds have little to no inflammation and are characterized only by pain.4 The puncture wound is too small to be seen, and C exilicauda and C sculpturatus venom do not cause local tissue destruction, an important factor in distinguishing it from other scorpion envenomations.

More severe complications that may follow are caused by the neurotoxin released by Centruroides stings. The toxin components can increase the duration and amplitude of the neuronal action potential and enhance the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine.8 Stings can lead to cranial nerve dysfunction and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction as well as autonomic dysfunction, specifically salivation, fever, tongue and muscle fasciculations, opsoclonus, vomiting, bronchoconstriction, diaphoresis, nystagmus, blurred vision, slurred speech, hypertension, rhabdomyolysis, stridor, wheezing, aspiration, anaphylaxis, and tachycardia, leading to cardiac and respiratory compromise.4,8 Some patients have experienced a decreased sense of smell or hearing and decreased fine motor movements.7 Although pancreatitis may occur with scorpion stings, it is not common for C exilicauda.9 Comorbidities such as cardiac disease and substance use disorders contribute to prolonged length of hospital stay and poor outcome.8

Treatment

Most Centruroides stings can be managed at home, but patients with more serious symptoms and children younger than 2 years should be taken to a hospital for treatment.7 If a patient reports only pain but shows no other signs of neurotoxicity, observation and pain relief with rest, ice, and elevation is appropriate management. Patients with severe manifestations have been treated with various combinations of lorazepam, glycopyrrolate, ipratropium bromide, and ondansetron, but the only treatment definitively shown to decrease time to symptom abatement is antivenin.7 It has been demonstrated that C exilicauda and C sculpturatus antivenin is relatively safe.7 Most patients, especially adults, do not die from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus stings; therefore, antivenin more commonly is symptom abating than it is lifesaving.10 In children, time to symptom resolution was decreased to fewer than 4 hours with antivenin, and there is a lower rate of inpatient admission when antivenin is administered.4,10,11 There is a low incidence of anaphylactic reaction after antivenin, but there have been reported cases of self-limited serum sickness after antivenin use that generally can be managed with antihistamines and corticosteroids.4,7

Epidemiology and Identification

Centruroides is a common genus of bark scorpions in the United States with at least 21 species considered to be medically important, including the closely related Centruroides exilicauda and Centruroides sculpturatus.1 Scorpions can be recognized by a bulbous sac and pointed stinger at the end of a tail-like abdomen. They also have long lobsterlike pedipalps (pincers) for grasping their prey. Identifying characteristics for C exilicauda and C sculpturatus include a small, slender, yellow to light brown or tan body typically measuring 1.3 to 7.6 cm in length with a subaculear tooth or tubercle at the base of the stinger, a characteristic that is common to all Centruroides species (Figure).2 Some variability in size has been shown, with smaller scorpions found in increased elevations and cooler temperatures.1,3 Both C exilicauda and C sculpturatus are found in northern Mexico as well as the southwestern United States (eg, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, California, Nevada).1 They have a preference for residing in or around trees and often are found on the underside of bark, stones, or tables as well as inside shoes or small cracks and crevices. Scorpions typically sting in self-defense, and stings commonly occur when humans attempt to move tables, put on shoes, or walk barefoot in scorpion-infested areas. Most stings occur from the end of spring through the end summer, but many may go unreported.1,4

The venom of the Centruroides genus includes peptides and proteins that play a fundamental role in toxic activity by impairing potassium, sodium, and calcium ion channels.1,3 Toxins have been shown to be species specific, functioning either in capturing prey or deterring predators. Intraspecies variability in toxins has been demonstrated, which may complicate the production of adequate antivenin.3 Many have thought that C exilicauda Wood and C sculpturatus Ewing are the same species, and the names have been used synonymously in the past; however, genetic and biochemical studies of their venom components have shown that they are distinct species and that C sculpturatus is the more dangerous of the two.5 The median lethal dose 50% of C sculpturatus was found to be 22.7 μg in CD1 mice.6

Envenomation and Clinical Manifestations

Stings from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus have been shown to cause fatality in children more often than in adults.7 In the United States, Arizona has the highest frequency of serious symptoms of envenomation as well as the highest hospital and intensive care unit admission rates.6 Envenomation results in an immediate sharp burning pain followed by numbness.4 Wounds can produce some regional lymph node swelling, ecchymosis, paresthesia, and lymphangitis. More often than not, however, wounds have little to no inflammation and are characterized only by pain.4 The puncture wound is too small to be seen, and C exilicauda and C sculpturatus venom do not cause local tissue destruction, an important factor in distinguishing it from other scorpion envenomations.

More severe complications that may follow are caused by the neurotoxin released by Centruroides stings. The toxin components can increase the duration and amplitude of the neuronal action potential and enhance the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine.8 Stings can lead to cranial nerve dysfunction and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction as well as autonomic dysfunction, specifically salivation, fever, tongue and muscle fasciculations, opsoclonus, vomiting, bronchoconstriction, diaphoresis, nystagmus, blurred vision, slurred speech, hypertension, rhabdomyolysis, stridor, wheezing, aspiration, anaphylaxis, and tachycardia, leading to cardiac and respiratory compromise.4,8 Some patients have experienced a decreased sense of smell or hearing and decreased fine motor movements.7 Although pancreatitis may occur with scorpion stings, it is not common for C exilicauda.9 Comorbidities such as cardiac disease and substance use disorders contribute to prolonged length of hospital stay and poor outcome.8

Treatment

Most Centruroides stings can be managed at home, but patients with more serious symptoms and children younger than 2 years should be taken to a hospital for treatment.7 If a patient reports only pain but shows no other signs of neurotoxicity, observation and pain relief with rest, ice, and elevation is appropriate management. Patients with severe manifestations have been treated with various combinations of lorazepam, glycopyrrolate, ipratropium bromide, and ondansetron, but the only treatment definitively shown to decrease time to symptom abatement is antivenin.7 It has been demonstrated that C exilicauda and C sculpturatus antivenin is relatively safe.7 Most patients, especially adults, do not die from C exilicauda and C sculpturatus stings; therefore, antivenin more commonly is symptom abating than it is lifesaving.10 In children, time to symptom resolution was decreased to fewer than 4 hours with antivenin, and there is a lower rate of inpatient admission when antivenin is administered.4,10,11 There is a low incidence of anaphylactic reaction after antivenin, but there have been reported cases of self-limited serum sickness after antivenin use that generally can be managed with antihistamines and corticosteroids.4,7

- Gonzalez-Santillan E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Tropica. 2018;187:264-274.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Carcamo-Noriega EN, Olamendi-Portugal T, Restano-Cassulini R, et al. Intraspecific variation of Centruroides sculpturatus scorpion venom from two regions of Arizona. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;638:52-57.

- Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US Poison Control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165.

- Valdez-Cruz N, Dávila S, Licea A, et al. Biochemical, genetic and physiological characterization of venom components from two species of scorpions: Centruroides exilicauda Wood and Centruroides sculpturatus Ewing. Biochimie. 2004;86:387-396.

- Jiménez-Vargas JM, Quintero-Hernández V, Gonzáles-Morales L, et al. Design and expression of recombinant toxins from Mexican scorpions of the genus Centruroides for production of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2017;128:5-14.

- Hurst NB, Lipe DN, Karpen SR, et al. Centruroides sculpturatus envenomation in three adult patients requiring treatment with antivenom. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:294-296.

- O’Connor A, Padilla-Jones A, Ruha A. Severe bark scorpion envenomation in adults. Clin Toxicol. 2018;56:170-174.

- Berg R, Tarantino M. Envenomation by the scorpion Centruroides exilicauda (C sculpturatus): severe and unusual manifestations. Pediatrics. 1991;87:930-933.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Rodrigo C, Gnanathasan A. Management of scorpion envenoming: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Syst Rev. 2017;6:74.

- Gonzalez-Santillan E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Tropica. 2018;187:264-274.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Carcamo-Noriega EN, Olamendi-Portugal T, Restano-Cassulini R, et al. Intraspecific variation of Centruroides sculpturatus scorpion venom from two regions of Arizona. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;638:52-57.

- Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US Poison Control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165.

- Valdez-Cruz N, Dávila S, Licea A, et al. Biochemical, genetic and physiological characterization of venom components from two species of scorpions: Centruroides exilicauda Wood and Centruroides sculpturatus Ewing. Biochimie. 2004;86:387-396.

- Jiménez-Vargas JM, Quintero-Hernández V, Gonzáles-Morales L, et al. Design and expression of recombinant toxins from Mexican scorpions of the genus Centruroides for production of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2017;128:5-14.

- Hurst NB, Lipe DN, Karpen SR, et al. Centruroides sculpturatus envenomation in three adult patients requiring treatment with antivenom. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:294-296.

- O’Connor A, Padilla-Jones A, Ruha A. Severe bark scorpion envenomation in adults. Clin Toxicol. 2018;56:170-174.

- Berg R, Tarantino M. Envenomation by the scorpion Centruroides exilicauda (C sculpturatus): severe and unusual manifestations. Pediatrics. 1991;87:930-933.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Rodrigo C, Gnanathasan A. Management of scorpion envenoming: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Syst Rev. 2017;6:74.

Practice Points

- Centruroides scorpions can inflict painful stings.

- Children are at greatest risk for systemic toxicity.

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in the Armed Forces

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory disorder most commonly involving the occipital scalp and posterior neck characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques. If left untreated, this condition may progress to scarring alopecia. It primarily affects males of African descent, but it also may occur in females and in other ethnic groups. Although the exact underlying pathogenesis is unclear, close haircuts and chronic mechanical irritation to the posterior neck and scalp are known inciting factors. For this reason, AKN disproportionately affects active-duty military servicemembers who are held to strict grooming standards. The US Military maintains these grooming standards to ensure uniformity, self-discipline, and serviceability in operational settings.1 Regulations dictate short tapered hair, particularly on the back of the neck, which can require weekly to biweekly haircuts to maintain.1-5

First-line treatment of AKN is prevention by avoiding short haircuts and other forms of mechanical irritation.1,6,7 However, there are considerable barriers to this strategy within the military due to uniform regulations as well as personal appearance and grooming standards. Early identification and treatment are of utmost importance in managing AKN in the military population to ensure reduction of morbidity, prevention of late-stage disease, and continued fitness for duty. This article reviews the clinical features, epidemiology, and treatments available for management of AKN, with a special focus on the active-duty military population.

Clinical Features and Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by the development of keloidlike papules, pustules, and plaques on the posterior neck and occipital scalp.6 Also known as folliculitis keloidalis nuchae, AKN is seen primarily in men of African descent, though cases also have been reported in females and in a few other ethnic groups.6,7 In black males, the AKN prevalence worldwide ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%. The male to female ratio is 20 to 1.7 Although the exact cause is unknown, AKN appears to develop from chronic irritation and inflammation following localized skin injury and/or trauma. Chronic irritation from close-shaved haircuts, tight-fitting shirt collars, caps, and helmets have all been implicated as considerable risk factors.6-8

Symptoms generally develop hours to days following a close haircut and begin with the early formation of inflamed irritated papules and notable erythema.6,7 These papules may become secondarily infected and develop into pustules and/or abscesses, especially in cases in which the affected individual continues to have the hair shaved. Continued use of shared razors increases the risk for secondary infection and also raises the concern for transmission of blood-borne pathogens, as AKN lesions are quick to bleed with minor trauma.7

Over time, chronic inflammation and continued trauma of the AKN papules leads to widespread fibrosis and scar formation, as the papules coalesce into larger plaques and nodules. If left untreated, these later stages of disease can progress to chronic scarring alopecia.6

Prevention

In the general population, first-line therapy of AKN is preventative. The goal is to break the cycle of chronic inflammation, thereby preventing the development of additional lesions and subsequent scarring.7 Patients should be encouraged to avoid frequent haircuts, close shaves, hats, helmets, and tight shirt collars.6-8

A 2017 cross-sectional study by Adotama et al9 investigated recognition and management of AKN in predominantly black barbershops in an urban setting. Fifty barbers from barbershops in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, were enrolled and interviewed for the study. Of these barbers, only 44% (22/50) were able to properly identify AKN from a photograph. Although the vast majority (94% [47/50]) were aware that razor use would aggravate the condition, only 46% (23/50) reported avoidance of cutting hair for clients with active AKN.9 This study, while limited by its small sample size, showed that many barbers may be unaware of AKN and therefore unknowingly contribute to the disease process by performing haircuts on actively inflamed scalps. For this reason, it is important to educate patients about their condition and strongly recommend lifestyle and hairstyle modifications in the management of their disease.

Acne keloidalis nuchae that is severe enough to interfere with the proper use and wear of military equipment (eg, Kevlar helmets) or maintenance of regulation grooming standards does not meet military admission standards.10,11 However, mild undiagnosed cases may be overlooked during entrance physical examinations, while many servicemembers develop AKN after entering the military.10 For these individuals, long-term avoidance of haircuts is not a realistic or obtainable therapeutic option.

Treatment

Topical Therapy

Early mild to moderate cases of AKN—papules less than 3 mm, no nodules present—may be treated with potent topical steroids. Studies have shown 2-week alternating cycles of high-potency topical steroids (2 weeks of twice-daily application followed by 2 weeks without application) for 8 to 12 weeks to be effective in reducing AKN lesions.8,12 Topical clindamycin also may be added and has demonstrated efficacy particularly when pustules are present.7,8

Intralesional Steroids

For moderate cases of AKN—papules more than 3 mm, plaques, and nodules—intralesional steroid injections may be considered. Triamcinolone may be used at a dose of 5 to 40 mg/mL administered at 4-week intervals.7 More concentrated doses will produce faster responses but also carry the known risk of side effects such as hypopigmentation in darker-skinned individuals and skin atrophy.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy with oral antibiotics may be warranted as an adjunct to mild to moderate cases of AKN or in cases with clear evidence of secondary infection. Long-term tetracycline antibiotics, such as minocycline and doxycycline, may be used concurrently with topical and/or intralesional steroids.6,7 Their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects are useful in controlling secondary infections and reducing overall chronic inflammation.

When selecting an appropriate antibiotic for long-term use in active-duty military patients, it is important to consider their effects on duty status. Doxycycline is preferred for active-duty servicemembers because it is not duty limiting or medically disqualifying.10,13-15 However, minocycline, is restricted for use in aviators and aircrew members due to the risk for central nervous system side effects, which may include light-headedness, dizziness, and vertigo.

UV Light Therapy

UV radiation has known anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and antifibrotic effects and commonly is used in the treatment of many dermatologic conditions.16 Within the last decade, targeted UVB (tUVB) radiation has shown promise as an effective alternative therapy for AKN. In 2014, Okoye et al16 conducted a prospective, randomized, split-scalp study in 11 patients with AKN. Each patient underwent treatment with a tUVB device (with peaks at 303 and 313 nm) to a randomly selected side of the scalp 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. Significant reductions in lesion count were seen on the treated side after 8 (P=.03) and 16 weeks (P=.04), with no change noted on the control side. Aside from objective lesion counts, patients completed questionnaires (n=6) regarding their treatment outcomes. Notably, 83.3% (5/6) reported marked improvement in their condition. Aside from mild transient burning and erythema of the treated area, no serious side effects were reported.16

Targeted UVB phototherapy has limited utility in an operational setting due to accessibility and operational tempo. Phototherapy units typically are available only at commands in close proximity to large medical treatment facilities. Further, the vast majority of servicemembers have duty hours that are not amenable to multiple treatment sessions per week for several months. For servicemembers in administrative roles or serving in garrison or shore billets, tUVB or narrowband UV phototherapy may be viable treatment options.

Laser Therapy

Various lasers have been used to treat AKN, including the CO2 laser, pulsed dye laser, 810-nm diode laser, and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6 Kantor et al17 utilized a CO2 laser with a focused beam for surgical excision of a late-stage AKN case as early as 1986. In these patients, it was demonstrated that focused CO2 laser could be used to remove fibrotic lesions in an outpatient setting with only local anesthesia. Although only 8 patients were treated in this report, no relapses occurred.17

CO2 laser evaporation using the unfocused beam setting with 130 to 150 J/cm2 has been less successful, with relapses reported in multiple cases.6 Dragoni et al18 attempted treatment with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser with 6.5-J/cm2 fluence and 0.5-millisecond pulse but faced similar results, with lesions returning within 1 month.

There have been numerous reports of clinical improvement of AKN with the use of the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,19 Esmat et al19 treated 16 patients with a fluence of 35 to 45 J/cm2 and pulse duration of 10 to 30 milliseconds adjusted to skin type and hair thickness. An overall 82% reduction in lesion count was observed after 5 treatment sessions. Biopsies following the treatment course demonstrated a significant reduction in papule and plaque count (P=.001 and P=.011, respectively), and no clinical recurrences were noted at 12 months posttreatment.19 Similarly, Woo et al20 conducted a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the Nd:YAG laser in combination with topical corticosteroid therapy vs topical corticosteroid monotherapy. Of the 20 patients treated, there was a statistically significant improvement in patients with papule-only AKN who received the laser and topical combination treatment (P=.031).20

Laser therapy may be an available treatment option for military servicemembers stationed within close proximity to military treatment facilities, with the Nd:YAG laser typically having the widest availability. Although laser therapy may be effective in early stages of disease, servicemembers would have to be amenable to limitation of future hair growth in the treated areas.

Surgical Excision

Surgical excision may be considered for large, extensive, disfiguring, and/or refractory lesions. Excision is a safe and effective method to remove tender, inflamed, keloidlike masses. Techniques for excision include electrosurgical excision with secondary intention healing, excision of a horizontal ellipse involving the posterior hairline with either primary closure or secondary intention healing, and use of a semilunar tissue expander prior to excision and closure.6 Regardless of the technique, it is important to ensure that affected tissue is excised at a depth that includes the base of the hair follicles to prevent recurrence.21

Final Thoughts