User login

67-year-old woman • excessive flatulence • persistent heartburn • chronic cough • Dx?

THE CASE

A 67-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to our family medicine office for evaluation of excessive flatulence, belching, and bloating that had worsened over the previous 6 months. The patient said the symptoms occurred throughout the day but were most noticeable after eating meals. She had a 5-year history of heartburn and chronic cough. We initially suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, trials with several different proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) over a 3-year period did not provide any relief. Lifestyle modifications such as losing weight; remaining upright for at least 3 hours after eating; and eliminating gluten, dairy, soy, and alcohol from her diet did not alleviate her symptoms.

At the current presentation, the physical examination was normal, and an upper endoscopy was unremarkable except for some mild gastric irritation. A urea breath test was negative for Helicobacter pylori, and a chest radiograph to investigate the cause of the chronic cough was normal. The patient’s increased symptoms after eating indicated that a sensitivity to food antibodies might be at work. The absence of urticaria and anaphylaxis correlated with an IgG-mediated rather than an IgE-mediated reaction.

Due to the high cost of IgG testing, we recommended that the patient start a 6-week elimination diet that excluded the most common culprits for food allergies: dairy, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soy.1 We also recommended that she eliminate alcohol (because of its role in exacerbating GERD); however, excluding these foods from her diet did not provide sufficient relief of her symptoms. We subsequently recommended a serum IgG food antibody test.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The results of the test were positive for IgG-mediated allergy to vegetables in the onion family, as indicated by a high (3+) antibody presence. The patient told us she consumed onions up to 3 times daily in her meals. We recommended that she eliminate onions from her diet. At a follow-up appointment 3 months later, the patient reported that the flatulence, belching, and bloating after eating had resolved and her heartburn had decreased. When we asked about her chronic cough, the patient mentioned she had not experienced it for a few months and had forgotten about it.

DISCUSSION

The most common food sensitivity test is the scratch test, which only measures IgE antibodies. However, past studies have suggested that IgE is not the only mediator in certain symptoms related to food allergy. It is thought that these symptoms may instead be IgG mediated.2 Normally, IgG antibodies do not form in the digestive tract because the epithelium creates a barrier that is impermeable to antigens. However, antigens can bypass the epithelium and reach immune cells in states of inflammation where the epithelium is damaged. This contact with immune cells provides an opportunity for development of IgG antibodies.3 Successive interactions with these antigens leads to defensive and inflammatory processes that manifest as food allergies.

Rather than the typical IgE-mediated presentations (eg, urticaria, anaphylaxis), patients with IgG-mediated allergies experience more subtle symptoms, such as nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, cramping, bloating, heartburn, cough, bronchoconstriction, eczema, stiff joints, headache, and/or increased risk of infection.4 One study showed that eliminating IgG-sensitive foods (eg, dairy, eggs) improved symptoms in migraine patients.5 Likewise, a separate study showed that patients with irritable bowel syndrome experienced improved symptoms after eliminating foods for which they had high IgG sensitivity.6

Casting a wider net. Whereas scratch testing only looks at IgE-mediated allergies, serum IgG food antibody testing looks for both IgE- and IgG-mediated reactions. IgE-mediated food allergies are monitored via the scratch test as a visual expression of a histamine reaction on the skin. However, serum IgG food antibody testing identifies culprit foods via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Continue to: Furthermore, the serum antibody test...

Furthermore, the serum antibody test also identifies allergenic foods whose symptoms have a delayed onset of 4 to 72 hours.7 Without this test, those symptoms may be wrongfully attributed to other conditions, and prescribed treatments will not treat the root cause of the reaction.8 The information provided in the serum antibody test allows the patient to develop a tailored elimination diet and eliminate causative food(s) faster. Without this test, we may not have identified onions as the allergenic food in our patient.

THE TAKEAWAY

Recent guidelines emphasize that IgG testing plays no role in the diagnosis of food allergies or intolerance.1 This may indeed be true for the general population, but other studies have shown IgG testing to be of value for specific diagnoses such as migraines or irritable bowel syndrome.5,6 Given our patient’s unique presentation and lack of response to traditional treatments, IgG testing was warranted. This case demonstrates the importance of IgG food antibody testing as part of a second-tier diagnostic workup when a patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms are not alleviated by traditional interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Khan, MD, Personalized Longevity Medical Center, 1146 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; [email protected].

1. Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1105-1118.

2. Kemeny DM, Urbanek R, Amlot PL, et al. Sub-class of IgG in an allergic disease. I. IgG sub-class antibodies in immediate and non-immediate food allergies. Clin Allergy. 1986;16:571-581.

3. Gocki J, Zbigniew B. Role of immunoglobulin G antibodies in diagnosis of food allergy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:253-256.

4. Shaw W. Clinical usefulness of IgG food allergy testing. Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Web site. www.immh.org/article-source/2016/6/29/clinical-usefulness-of-igg-food-allergy-testing. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. Arroyave Hernández CM, Echavarría Pinto M, Hernández Montiel HL. Food allergy mediated by IgG antibodies associated with migraine in adults. Rev Alerg Mex. 2007;54:162-168.

6. Guo H, Jiang T, Wang J, et al. The value of eliminating foods according to food-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:204-210.

7. IgG food antibodies. Genova Diagnostics Web site. www.gdx.net/product/igg-food-antibodies-food-sensitivity-test-blood. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, et al. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459-1464.

THE CASE

A 67-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to our family medicine office for evaluation of excessive flatulence, belching, and bloating that had worsened over the previous 6 months. The patient said the symptoms occurred throughout the day but were most noticeable after eating meals. She had a 5-year history of heartburn and chronic cough. We initially suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, trials with several different proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) over a 3-year period did not provide any relief. Lifestyle modifications such as losing weight; remaining upright for at least 3 hours after eating; and eliminating gluten, dairy, soy, and alcohol from her diet did not alleviate her symptoms.

At the current presentation, the physical examination was normal, and an upper endoscopy was unremarkable except for some mild gastric irritation. A urea breath test was negative for Helicobacter pylori, and a chest radiograph to investigate the cause of the chronic cough was normal. The patient’s increased symptoms after eating indicated that a sensitivity to food antibodies might be at work. The absence of urticaria and anaphylaxis correlated with an IgG-mediated rather than an IgE-mediated reaction.

Due to the high cost of IgG testing, we recommended that the patient start a 6-week elimination diet that excluded the most common culprits for food allergies: dairy, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soy.1 We also recommended that she eliminate alcohol (because of its role in exacerbating GERD); however, excluding these foods from her diet did not provide sufficient relief of her symptoms. We subsequently recommended a serum IgG food antibody test.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The results of the test were positive for IgG-mediated allergy to vegetables in the onion family, as indicated by a high (3+) antibody presence. The patient told us she consumed onions up to 3 times daily in her meals. We recommended that she eliminate onions from her diet. At a follow-up appointment 3 months later, the patient reported that the flatulence, belching, and bloating after eating had resolved and her heartburn had decreased. When we asked about her chronic cough, the patient mentioned she had not experienced it for a few months and had forgotten about it.

DISCUSSION

The most common food sensitivity test is the scratch test, which only measures IgE antibodies. However, past studies have suggested that IgE is not the only mediator in certain symptoms related to food allergy. It is thought that these symptoms may instead be IgG mediated.2 Normally, IgG antibodies do not form in the digestive tract because the epithelium creates a barrier that is impermeable to antigens. However, antigens can bypass the epithelium and reach immune cells in states of inflammation where the epithelium is damaged. This contact with immune cells provides an opportunity for development of IgG antibodies.3 Successive interactions with these antigens leads to defensive and inflammatory processes that manifest as food allergies.

Rather than the typical IgE-mediated presentations (eg, urticaria, anaphylaxis), patients with IgG-mediated allergies experience more subtle symptoms, such as nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, cramping, bloating, heartburn, cough, bronchoconstriction, eczema, stiff joints, headache, and/or increased risk of infection.4 One study showed that eliminating IgG-sensitive foods (eg, dairy, eggs) improved symptoms in migraine patients.5 Likewise, a separate study showed that patients with irritable bowel syndrome experienced improved symptoms after eliminating foods for which they had high IgG sensitivity.6

Casting a wider net. Whereas scratch testing only looks at IgE-mediated allergies, serum IgG food antibody testing looks for both IgE- and IgG-mediated reactions. IgE-mediated food allergies are monitored via the scratch test as a visual expression of a histamine reaction on the skin. However, serum IgG food antibody testing identifies culprit foods via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Continue to: Furthermore, the serum antibody test...

Furthermore, the serum antibody test also identifies allergenic foods whose symptoms have a delayed onset of 4 to 72 hours.7 Without this test, those symptoms may be wrongfully attributed to other conditions, and prescribed treatments will not treat the root cause of the reaction.8 The information provided in the serum antibody test allows the patient to develop a tailored elimination diet and eliminate causative food(s) faster. Without this test, we may not have identified onions as the allergenic food in our patient.

THE TAKEAWAY

Recent guidelines emphasize that IgG testing plays no role in the diagnosis of food allergies or intolerance.1 This may indeed be true for the general population, but other studies have shown IgG testing to be of value for specific diagnoses such as migraines or irritable bowel syndrome.5,6 Given our patient’s unique presentation and lack of response to traditional treatments, IgG testing was warranted. This case demonstrates the importance of IgG food antibody testing as part of a second-tier diagnostic workup when a patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms are not alleviated by traditional interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Khan, MD, Personalized Longevity Medical Center, 1146 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 67-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension presented to our family medicine office for evaluation of excessive flatulence, belching, and bloating that had worsened over the previous 6 months. The patient said the symptoms occurred throughout the day but were most noticeable after eating meals. She had a 5-year history of heartburn and chronic cough. We initially suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, trials with several different proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) over a 3-year period did not provide any relief. Lifestyle modifications such as losing weight; remaining upright for at least 3 hours after eating; and eliminating gluten, dairy, soy, and alcohol from her diet did not alleviate her symptoms.

At the current presentation, the physical examination was normal, and an upper endoscopy was unremarkable except for some mild gastric irritation. A urea breath test was negative for Helicobacter pylori, and a chest radiograph to investigate the cause of the chronic cough was normal. The patient’s increased symptoms after eating indicated that a sensitivity to food antibodies might be at work. The absence of urticaria and anaphylaxis correlated with an IgG-mediated rather than an IgE-mediated reaction.

Due to the high cost of IgG testing, we recommended that the patient start a 6-week elimination diet that excluded the most common culprits for food allergies: dairy, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soy.1 We also recommended that she eliminate alcohol (because of its role in exacerbating GERD); however, excluding these foods from her diet did not provide sufficient relief of her symptoms. We subsequently recommended a serum IgG food antibody test.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The results of the test were positive for IgG-mediated allergy to vegetables in the onion family, as indicated by a high (3+) antibody presence. The patient told us she consumed onions up to 3 times daily in her meals. We recommended that she eliminate onions from her diet. At a follow-up appointment 3 months later, the patient reported that the flatulence, belching, and bloating after eating had resolved and her heartburn had decreased. When we asked about her chronic cough, the patient mentioned she had not experienced it for a few months and had forgotten about it.

DISCUSSION

The most common food sensitivity test is the scratch test, which only measures IgE antibodies. However, past studies have suggested that IgE is not the only mediator in certain symptoms related to food allergy. It is thought that these symptoms may instead be IgG mediated.2 Normally, IgG antibodies do not form in the digestive tract because the epithelium creates a barrier that is impermeable to antigens. However, antigens can bypass the epithelium and reach immune cells in states of inflammation where the epithelium is damaged. This contact with immune cells provides an opportunity for development of IgG antibodies.3 Successive interactions with these antigens leads to defensive and inflammatory processes that manifest as food allergies.

Rather than the typical IgE-mediated presentations (eg, urticaria, anaphylaxis), patients with IgG-mediated allergies experience more subtle symptoms, such as nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, cramping, bloating, heartburn, cough, bronchoconstriction, eczema, stiff joints, headache, and/or increased risk of infection.4 One study showed that eliminating IgG-sensitive foods (eg, dairy, eggs) improved symptoms in migraine patients.5 Likewise, a separate study showed that patients with irritable bowel syndrome experienced improved symptoms after eliminating foods for which they had high IgG sensitivity.6

Casting a wider net. Whereas scratch testing only looks at IgE-mediated allergies, serum IgG food antibody testing looks for both IgE- and IgG-mediated reactions. IgE-mediated food allergies are monitored via the scratch test as a visual expression of a histamine reaction on the skin. However, serum IgG food antibody testing identifies culprit foods via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Continue to: Furthermore, the serum antibody test...

Furthermore, the serum antibody test also identifies allergenic foods whose symptoms have a delayed onset of 4 to 72 hours.7 Without this test, those symptoms may be wrongfully attributed to other conditions, and prescribed treatments will not treat the root cause of the reaction.8 The information provided in the serum antibody test allows the patient to develop a tailored elimination diet and eliminate causative food(s) faster. Without this test, we may not have identified onions as the allergenic food in our patient.

THE TAKEAWAY

Recent guidelines emphasize that IgG testing plays no role in the diagnosis of food allergies or intolerance.1 This may indeed be true for the general population, but other studies have shown IgG testing to be of value for specific diagnoses such as migraines or irritable bowel syndrome.5,6 Given our patient’s unique presentation and lack of response to traditional treatments, IgG testing was warranted. This case demonstrates the importance of IgG food antibody testing as part of a second-tier diagnostic workup when a patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms are not alleviated by traditional interventions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Khan, MD, Personalized Longevity Medical Center, 1146 South Cedar Crest Boulevard, Allentown, PA 18103; [email protected].

1. Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1105-1118.

2. Kemeny DM, Urbanek R, Amlot PL, et al. Sub-class of IgG in an allergic disease. I. IgG sub-class antibodies in immediate and non-immediate food allergies. Clin Allergy. 1986;16:571-581.

3. Gocki J, Zbigniew B. Role of immunoglobulin G antibodies in diagnosis of food allergy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:253-256.

4. Shaw W. Clinical usefulness of IgG food allergy testing. Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Web site. www.immh.org/article-source/2016/6/29/clinical-usefulness-of-igg-food-allergy-testing. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. Arroyave Hernández CM, Echavarría Pinto M, Hernández Montiel HL. Food allergy mediated by IgG antibodies associated with migraine in adults. Rev Alerg Mex. 2007;54:162-168.

6. Guo H, Jiang T, Wang J, et al. The value of eliminating foods according to food-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:204-210.

7. IgG food antibodies. Genova Diagnostics Web site. www.gdx.net/product/igg-food-antibodies-food-sensitivity-test-blood. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, et al. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459-1464.

1. Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored Expert Panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1105-1118.

2. Kemeny DM, Urbanek R, Amlot PL, et al. Sub-class of IgG in an allergic disease. I. IgG sub-class antibodies in immediate and non-immediate food allergies. Clin Allergy. 1986;16:571-581.

3. Gocki J, Zbigniew B. Role of immunoglobulin G antibodies in diagnosis of food allergy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:253-256.

4. Shaw W. Clinical usefulness of IgG food allergy testing. Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Web site. www.immh.org/article-source/2016/6/29/clinical-usefulness-of-igg-food-allergy-testing. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. Arroyave Hernández CM, Echavarría Pinto M, Hernández Montiel HL. Food allergy mediated by IgG antibodies associated with migraine in adults. Rev Alerg Mex. 2007;54:162-168.

6. Guo H, Jiang T, Wang J, et al. The value of eliminating foods according to food-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:204-210.

7. IgG food antibodies. Genova Diagnostics Web site. www.gdx.net/product/igg-food-antibodies-food-sensitivity-test-blood. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, et al. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459-1464.

COVID vaccine tested in people shows early promise

the company says in a news release.

Researchers also reported some side effects in the 45 people in the phase I study, but no significant safety issues, the news release says.

The vaccine is among hundreds being tested worldwide in an effort to halt the pandemic that has killed nearly 600,000 worldwide.

A researcher testing the vaccine called the results encouraging but cautioned more study is needed. “Importantly, the vaccine resulted in a robust immune response,” Evan Anderson, MD, principal investigator for the trial at Emory University, says in a news release. Emory and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute were the two sites for the study.

The company is already testing the vaccine in a larger group of people, known as a phase II trial. It plans to begin phase III trials in late July. Phase III trials involve testing the vaccine on an even larger group and are the final step before FDA approval.

The study results are published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Moderna’s vaccine uses messenger RNA, also called mRNA. It carries the instruction for making the spike protein, a key protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells when a person is infected. After it’s injected, it goes to the immune cells and instructs them to make copies of the spike protein, acting as if the cells have been infected with the actual coronavirus. This allows other immune cells to develop immunity.

In the study, participants were divided into three groups of 15 people each. All groups received two vaccinations 28 days apart. Each group received a different strength of the vaccine – either 25, 100, or 250 micrograms.

Every person in the study developed antibodies that can block the infection. Most commonly reported side effects after the second vaccination in the 100-microgram group were fatigue, chills, headache, and muscle pains, ranging from mild to moderately severe.

The phase II study has 300 heathy adults ages 18-55, along with another 300 ages 55 and older

Moderna says it hopes to include about 30,000 participants at the 100-microgram dose level in the U.S. for the phase III trial. The estimated start date is July 27.

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

the company says in a news release.

Researchers also reported some side effects in the 45 people in the phase I study, but no significant safety issues, the news release says.

The vaccine is among hundreds being tested worldwide in an effort to halt the pandemic that has killed nearly 600,000 worldwide.

A researcher testing the vaccine called the results encouraging but cautioned more study is needed. “Importantly, the vaccine resulted in a robust immune response,” Evan Anderson, MD, principal investigator for the trial at Emory University, says in a news release. Emory and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute were the two sites for the study.

The company is already testing the vaccine in a larger group of people, known as a phase II trial. It plans to begin phase III trials in late July. Phase III trials involve testing the vaccine on an even larger group and are the final step before FDA approval.

The study results are published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Moderna’s vaccine uses messenger RNA, also called mRNA. It carries the instruction for making the spike protein, a key protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells when a person is infected. After it’s injected, it goes to the immune cells and instructs them to make copies of the spike protein, acting as if the cells have been infected with the actual coronavirus. This allows other immune cells to develop immunity.

In the study, participants were divided into three groups of 15 people each. All groups received two vaccinations 28 days apart. Each group received a different strength of the vaccine – either 25, 100, or 250 micrograms.

Every person in the study developed antibodies that can block the infection. Most commonly reported side effects after the second vaccination in the 100-microgram group were fatigue, chills, headache, and muscle pains, ranging from mild to moderately severe.

The phase II study has 300 heathy adults ages 18-55, along with another 300 ages 55 and older

Moderna says it hopes to include about 30,000 participants at the 100-microgram dose level in the U.S. for the phase III trial. The estimated start date is July 27.

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

the company says in a news release.

Researchers also reported some side effects in the 45 people in the phase I study, but no significant safety issues, the news release says.

The vaccine is among hundreds being tested worldwide in an effort to halt the pandemic that has killed nearly 600,000 worldwide.

A researcher testing the vaccine called the results encouraging but cautioned more study is needed. “Importantly, the vaccine resulted in a robust immune response,” Evan Anderson, MD, principal investigator for the trial at Emory University, says in a news release. Emory and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute were the two sites for the study.

The company is already testing the vaccine in a larger group of people, known as a phase II trial. It plans to begin phase III trials in late July. Phase III trials involve testing the vaccine on an even larger group and are the final step before FDA approval.

The study results are published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Moderna’s vaccine uses messenger RNA, also called mRNA. It carries the instruction for making the spike protein, a key protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells when a person is infected. After it’s injected, it goes to the immune cells and instructs them to make copies of the spike protein, acting as if the cells have been infected with the actual coronavirus. This allows other immune cells to develop immunity.

In the study, participants were divided into three groups of 15 people each. All groups received two vaccinations 28 days apart. Each group received a different strength of the vaccine – either 25, 100, or 250 micrograms.

Every person in the study developed antibodies that can block the infection. Most commonly reported side effects after the second vaccination in the 100-microgram group were fatigue, chills, headache, and muscle pains, ranging from mild to moderately severe.

The phase II study has 300 heathy adults ages 18-55, along with another 300 ages 55 and older

Moderna says it hopes to include about 30,000 participants at the 100-microgram dose level in the U.S. for the phase III trial. The estimated start date is July 27.

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Taking steps to slow the upswing in oral and pharyngeal cancers

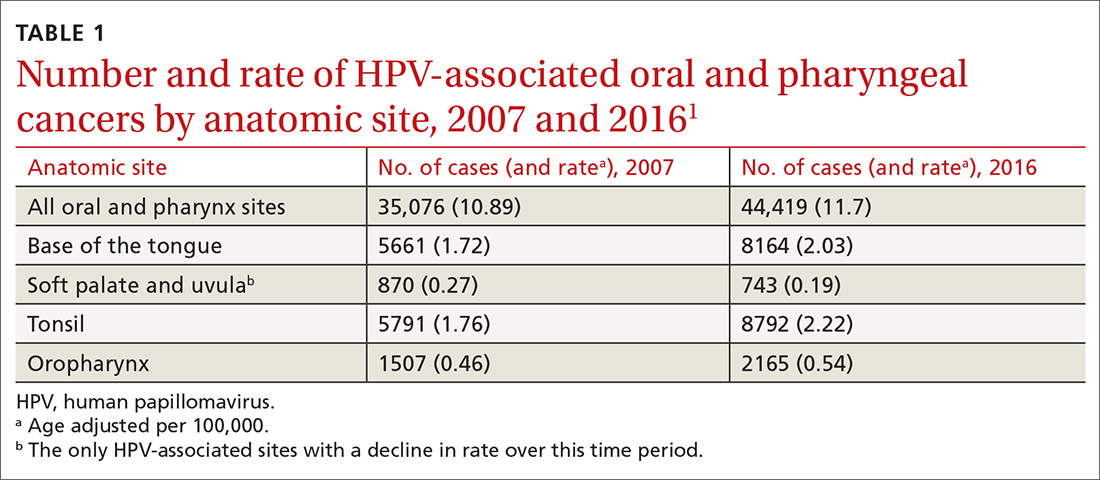

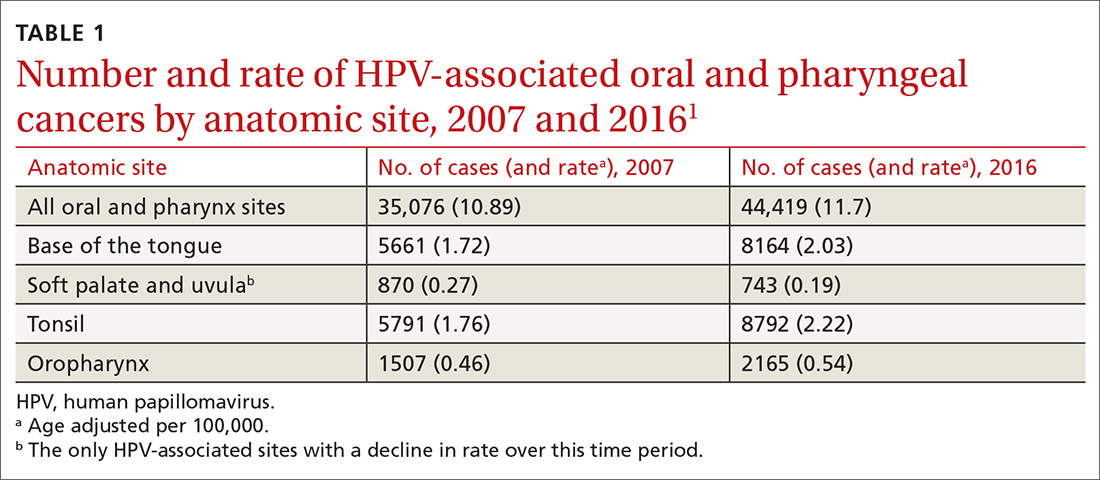

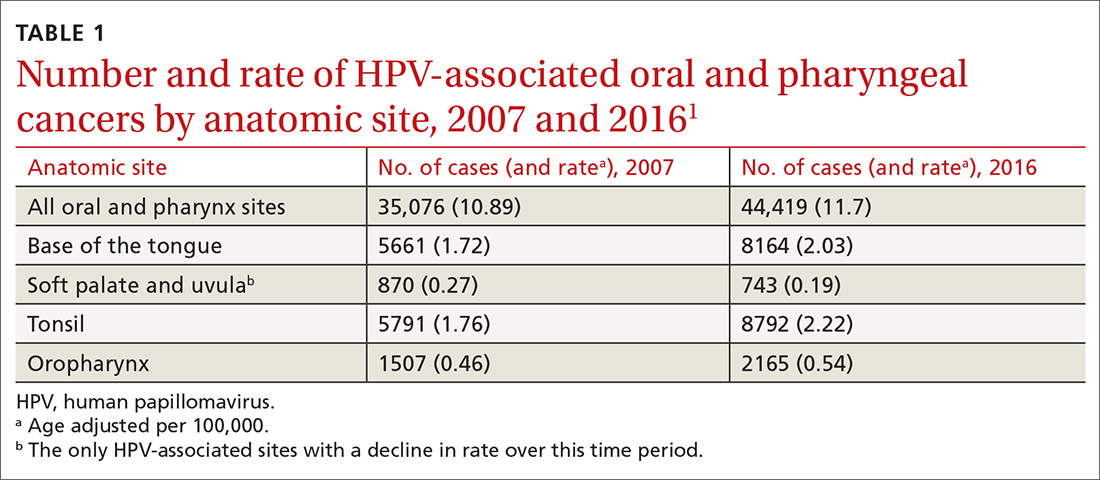

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents the trends in oral and pharyngeal cancers (OPC) in the United States over a 10-year period, 2007-2016.1 The rate of OPC began to increase in 1999 and has been increasing ever since. The age-adjusted rate in 2007 was 10.89/100,000 compared with 11.7/100,000 in 2016 (TABLE 11). This is an annual relative increase of about 6% per year. In absolute numbers, there were 35,076 cases in 2007 and 44,419 in 2016.1 The trends in incidence of OPC vary by anatomical site, with some increasing and others declining.

There are 3 known causal factors related to OPC: tobacco use, alcohol use, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The CDC estimates that, overall, 70% of OPCs are caused by HPV.2 However, while cancers at some oropharyngeal sites are likely related to HPV infection, cancers at other sites are not. The rising overall incidence of OPC is being driven by increases in HPV-related cancers at an average rate of 2.1% per year, while the rates at non-HPV-associated sites have been declining by 0.4% per year.1 It is also important to appreciate that HPV causes cancer at other anatomical sites (TABLE 22) and is responsible for an estimated 35,000 cancers per year.2

Other trends of note in all OPCs combined are increasing rates among non-Hispanic whites and Asian-Pacific Islanders; decreasing rates among Hispanics and African Americans; increasing rates among males with no real change in rates among females; increasing rates in those 50 to 79 years of age; decreasing rates among those 40 to 49 years of age; and unchanged rates in other age groups.1

The role of the family physician

Preventing OPC and all HPV-related cancers begins by encouraging patients to reduce alcohol and tobacco use and by emphasizing the importance of HPV vaccination. Educate teens and parents/guardians about HPV vaccine and its safety. Screen for tobacco and alcohol use, and offer brief clinical interventions as needed to decrease usage.

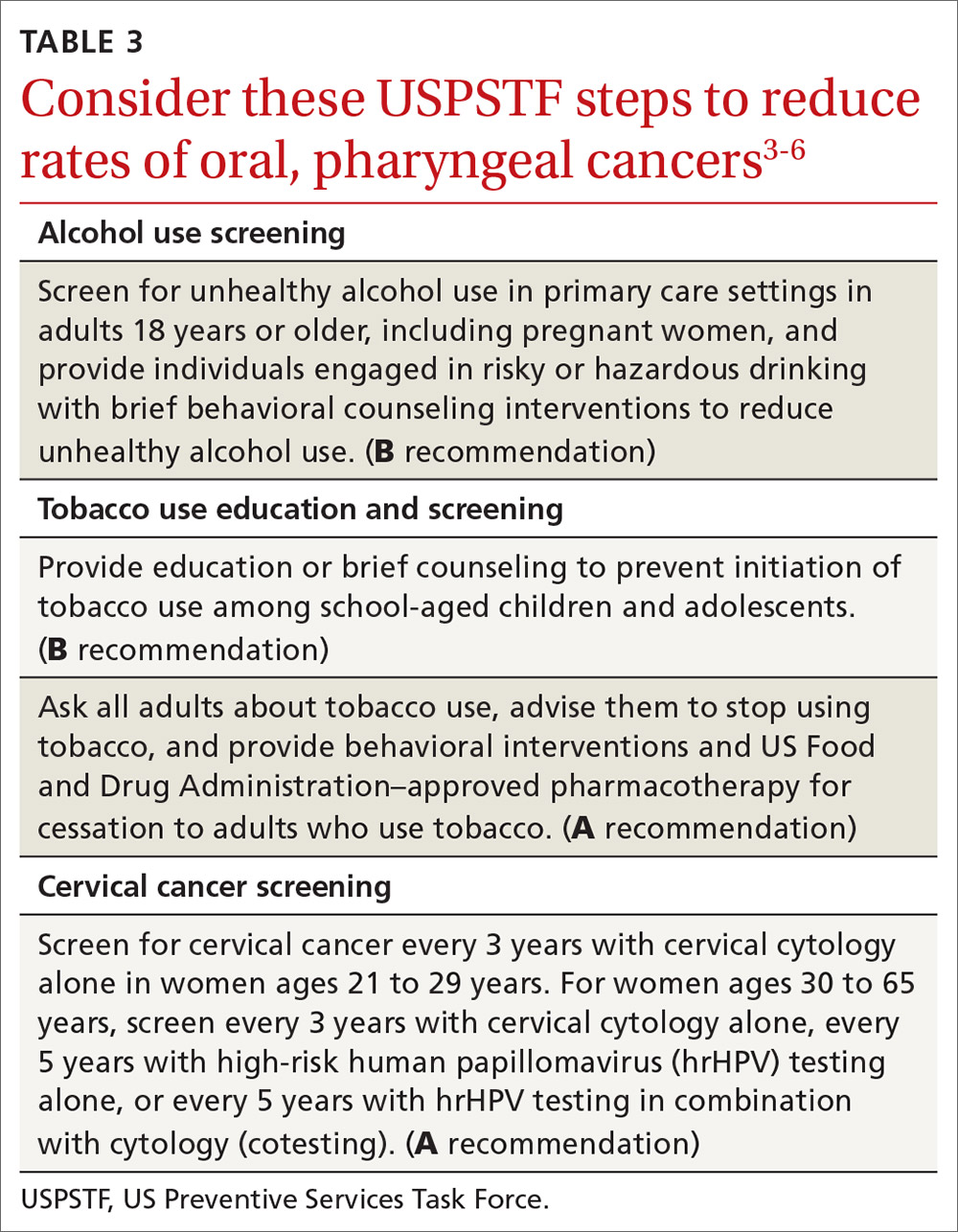

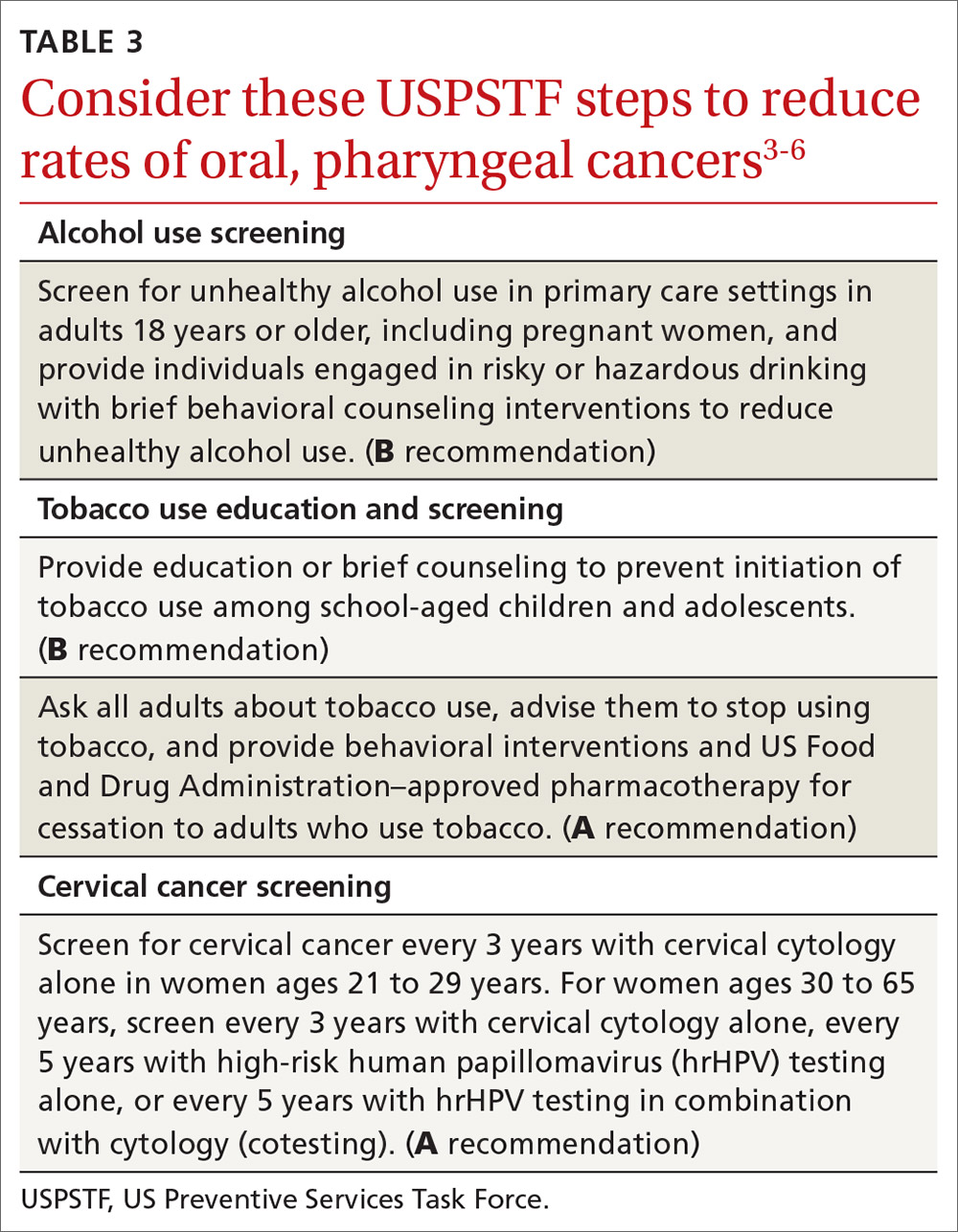

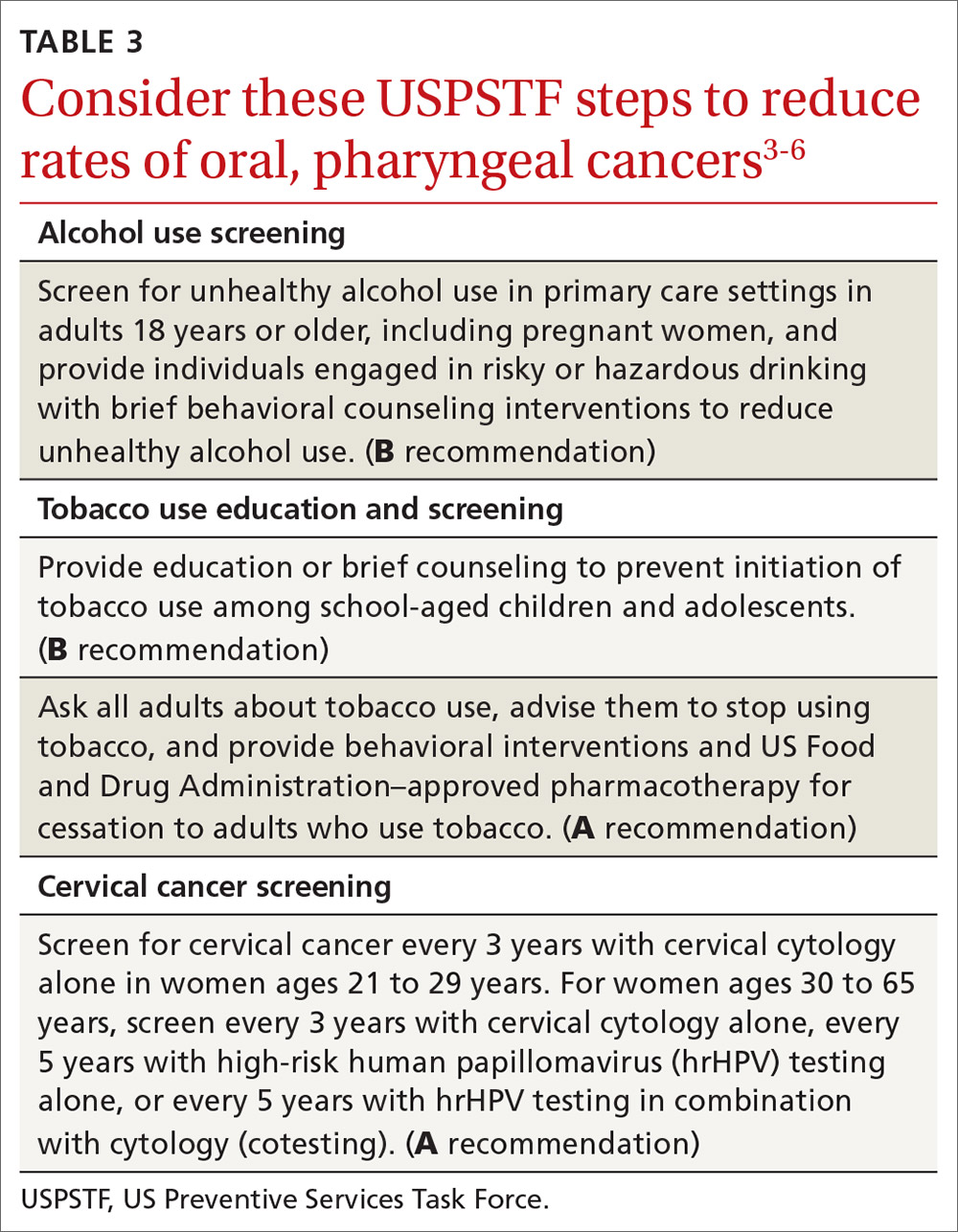

Recommendations by the US Preventive Services Task Force regarding screening for, and reducing use of, tobacco and alcohol, as well as screening for cervical cancer, are listed in TABLE 3.3-6 Remember that cervical cancer screening is both a primary and secondary intervention: It can reduce mortality by preventing cervical cancer (via treatment of precancerous lesions) and by detecting cervical cancer early at more treatable stages.

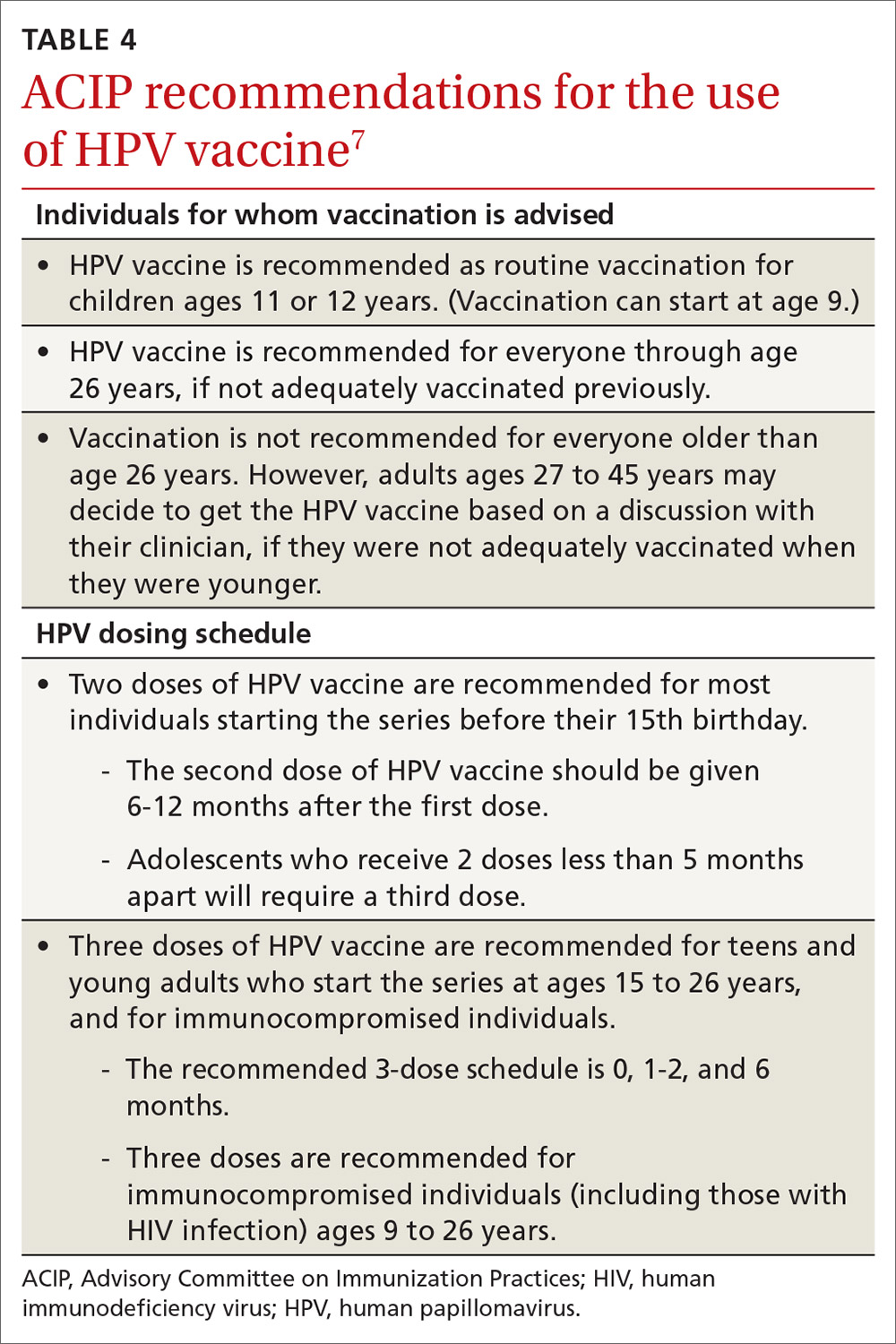

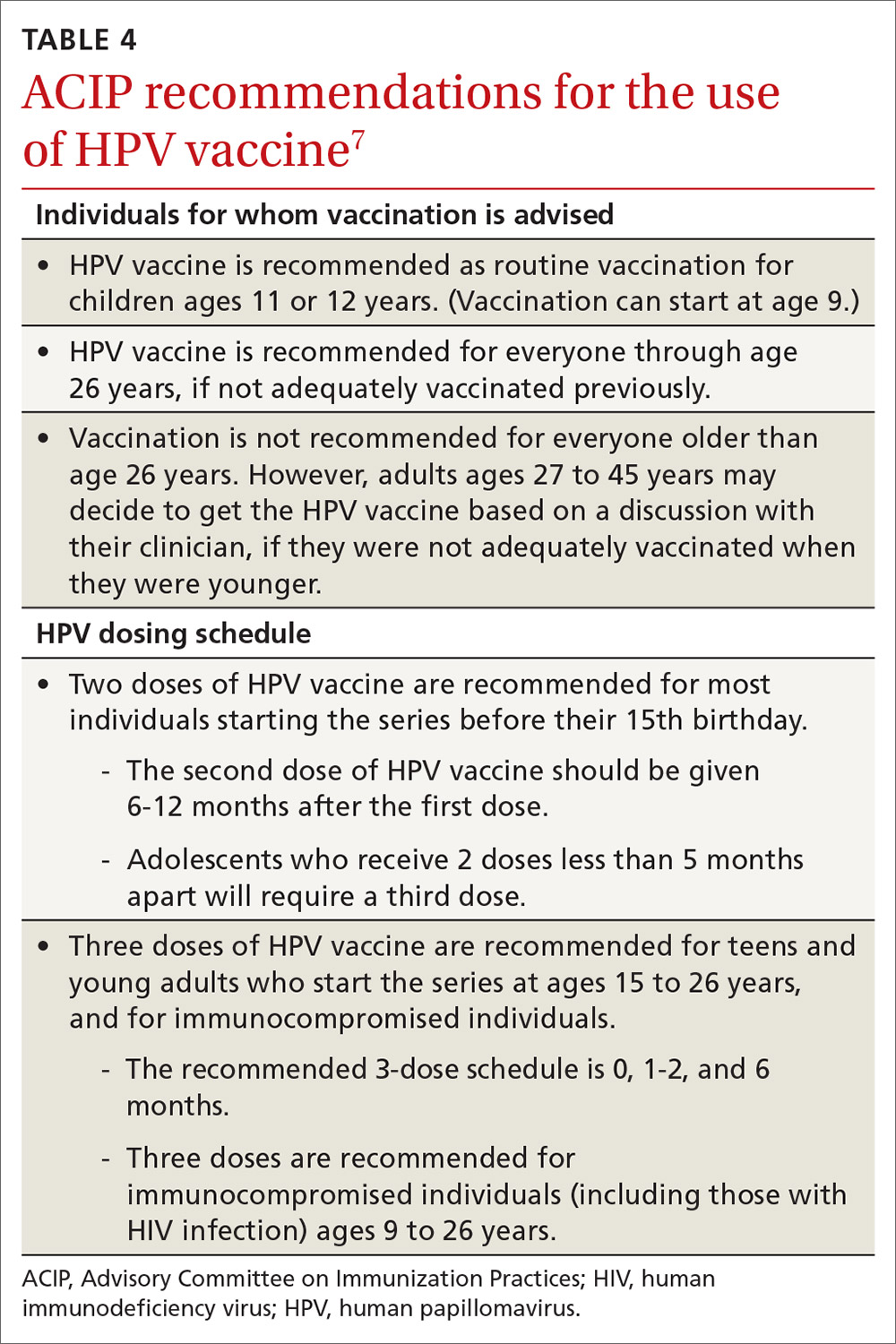

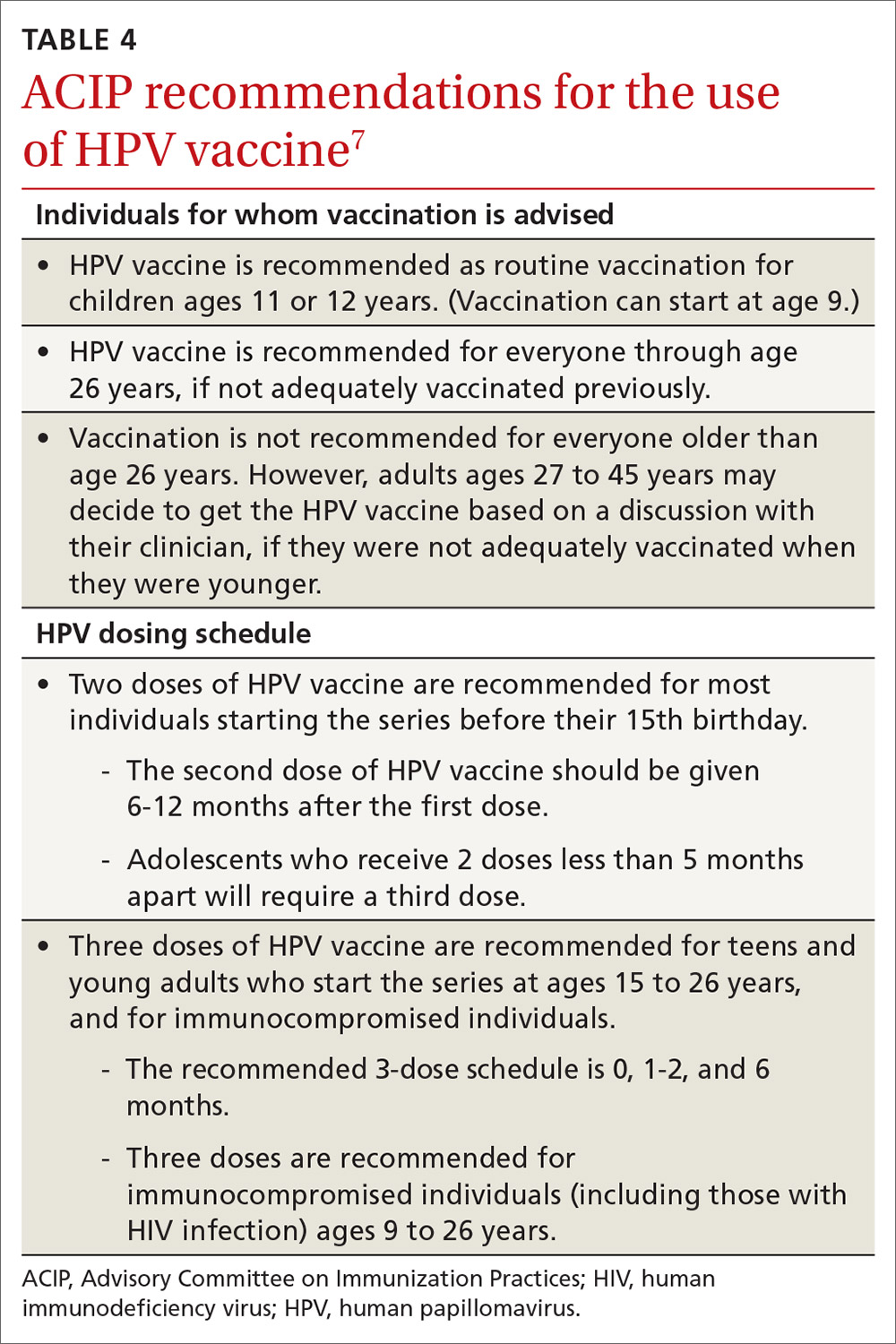

HPV vaccination essentials. CDC recommendations for the use of HPV vaccine and the vaccine dosing schedule appear in TABLE 4.7 While it is true that the best evidence for HPV vaccine’s prevention of cancer comes from the study of cervical and anal cancers, it is reasonable to expect that it will also be proven over time to prevent other HPV-caused cancers as the rate of HPV infections declines.

HPV vaccine is underused. In a 2018 survey, only 68.1% of adolescents had received 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine, and only 51.1% were up to date.8 In contrast, 86.6% had received 1 or more doses of quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine; 88.9% had received 1 or more doses of tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis vaccine; 91.9% were up to date with 2 or more doses of measles, mumps & rubella vaccine; and 92.1% were up to date with hepatitis B vaccine, with 3 or more doses.8

Continue to: Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

One study found 5 major false beliefs parents hold about HPV vaccine9:

- Vaccination is not effective at preventing cancer.

- Pap smears are sufficient to prevent cervical cancer.

- HPV vaccination is not safe.

- HPV vaccination is not needed since most infections are naturally cleared by the immune system.

- Eleven to 12 years of age is too young to vaccinate.

There is some evidence that if clinicians actively engage with parents about these concerns and address them head on, same-day vaccination rates can improve.10

We can expect to see HPV-associated OPC decline in the coming years due to the delayed effects on cancer incidence by the HPV vaccine. These anticipated declines will be more dramatic if we can increase the uptake of the HPV vaccine.

1. Ellington TD, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx—United States 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:433-438.

2. CDC. HPV and cancer. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

3. USPSTF. Unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: screening and behavioral counseling interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

4. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed June 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Vaccines and preventable diseases. HPV vaccine recommendations. 2020. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years-United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019:68:718-723.

9. Bednarczyk RA. Addressing HPV vaccine myths: practical information for healthcare providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1628-1638.

10. Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-provider communication of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172312.

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents the trends in oral and pharyngeal cancers (OPC) in the United States over a 10-year period, 2007-2016.1 The rate of OPC began to increase in 1999 and has been increasing ever since. The age-adjusted rate in 2007 was 10.89/100,000 compared with 11.7/100,000 in 2016 (TABLE 11). This is an annual relative increase of about 6% per year. In absolute numbers, there were 35,076 cases in 2007 and 44,419 in 2016.1 The trends in incidence of OPC vary by anatomical site, with some increasing and others declining.

There are 3 known causal factors related to OPC: tobacco use, alcohol use, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The CDC estimates that, overall, 70% of OPCs are caused by HPV.2 However, while cancers at some oropharyngeal sites are likely related to HPV infection, cancers at other sites are not. The rising overall incidence of OPC is being driven by increases in HPV-related cancers at an average rate of 2.1% per year, while the rates at non-HPV-associated sites have been declining by 0.4% per year.1 It is also important to appreciate that HPV causes cancer at other anatomical sites (TABLE 22) and is responsible for an estimated 35,000 cancers per year.2

Other trends of note in all OPCs combined are increasing rates among non-Hispanic whites and Asian-Pacific Islanders; decreasing rates among Hispanics and African Americans; increasing rates among males with no real change in rates among females; increasing rates in those 50 to 79 years of age; decreasing rates among those 40 to 49 years of age; and unchanged rates in other age groups.1

The role of the family physician

Preventing OPC and all HPV-related cancers begins by encouraging patients to reduce alcohol and tobacco use and by emphasizing the importance of HPV vaccination. Educate teens and parents/guardians about HPV vaccine and its safety. Screen for tobacco and alcohol use, and offer brief clinical interventions as needed to decrease usage.

Recommendations by the US Preventive Services Task Force regarding screening for, and reducing use of, tobacco and alcohol, as well as screening for cervical cancer, are listed in TABLE 3.3-6 Remember that cervical cancer screening is both a primary and secondary intervention: It can reduce mortality by preventing cervical cancer (via treatment of precancerous lesions) and by detecting cervical cancer early at more treatable stages.

HPV vaccination essentials. CDC recommendations for the use of HPV vaccine and the vaccine dosing schedule appear in TABLE 4.7 While it is true that the best evidence for HPV vaccine’s prevention of cancer comes from the study of cervical and anal cancers, it is reasonable to expect that it will also be proven over time to prevent other HPV-caused cancers as the rate of HPV infections declines.

HPV vaccine is underused. In a 2018 survey, only 68.1% of adolescents had received 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine, and only 51.1% were up to date.8 In contrast, 86.6% had received 1 or more doses of quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine; 88.9% had received 1 or more doses of tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis vaccine; 91.9% were up to date with 2 or more doses of measles, mumps & rubella vaccine; and 92.1% were up to date with hepatitis B vaccine, with 3 or more doses.8

Continue to: Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

One study found 5 major false beliefs parents hold about HPV vaccine9:

- Vaccination is not effective at preventing cancer.

- Pap smears are sufficient to prevent cervical cancer.

- HPV vaccination is not safe.

- HPV vaccination is not needed since most infections are naturally cleared by the immune system.

- Eleven to 12 years of age is too young to vaccinate.

There is some evidence that if clinicians actively engage with parents about these concerns and address them head on, same-day vaccination rates can improve.10

We can expect to see HPV-associated OPC decline in the coming years due to the delayed effects on cancer incidence by the HPV vaccine. These anticipated declines will be more dramatic if we can increase the uptake of the HPV vaccine.

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents the trends in oral and pharyngeal cancers (OPC) in the United States over a 10-year period, 2007-2016.1 The rate of OPC began to increase in 1999 and has been increasing ever since. The age-adjusted rate in 2007 was 10.89/100,000 compared with 11.7/100,000 in 2016 (TABLE 11). This is an annual relative increase of about 6% per year. In absolute numbers, there were 35,076 cases in 2007 and 44,419 in 2016.1 The trends in incidence of OPC vary by anatomical site, with some increasing and others declining.

There are 3 known causal factors related to OPC: tobacco use, alcohol use, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The CDC estimates that, overall, 70% of OPCs are caused by HPV.2 However, while cancers at some oropharyngeal sites are likely related to HPV infection, cancers at other sites are not. The rising overall incidence of OPC is being driven by increases in HPV-related cancers at an average rate of 2.1% per year, while the rates at non-HPV-associated sites have been declining by 0.4% per year.1 It is also important to appreciate that HPV causes cancer at other anatomical sites (TABLE 22) and is responsible for an estimated 35,000 cancers per year.2

Other trends of note in all OPCs combined are increasing rates among non-Hispanic whites and Asian-Pacific Islanders; decreasing rates among Hispanics and African Americans; increasing rates among males with no real change in rates among females; increasing rates in those 50 to 79 years of age; decreasing rates among those 40 to 49 years of age; and unchanged rates in other age groups.1

The role of the family physician

Preventing OPC and all HPV-related cancers begins by encouraging patients to reduce alcohol and tobacco use and by emphasizing the importance of HPV vaccination. Educate teens and parents/guardians about HPV vaccine and its safety. Screen for tobacco and alcohol use, and offer brief clinical interventions as needed to decrease usage.

Recommendations by the US Preventive Services Task Force regarding screening for, and reducing use of, tobacco and alcohol, as well as screening for cervical cancer, are listed in TABLE 3.3-6 Remember that cervical cancer screening is both a primary and secondary intervention: It can reduce mortality by preventing cervical cancer (via treatment of precancerous lesions) and by detecting cervical cancer early at more treatable stages.

HPV vaccination essentials. CDC recommendations for the use of HPV vaccine and the vaccine dosing schedule appear in TABLE 4.7 While it is true that the best evidence for HPV vaccine’s prevention of cancer comes from the study of cervical and anal cancers, it is reasonable to expect that it will also be proven over time to prevent other HPV-caused cancers as the rate of HPV infections declines.

HPV vaccine is underused. In a 2018 survey, only 68.1% of adolescents had received 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine, and only 51.1% were up to date.8 In contrast, 86.6% had received 1 or more doses of quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine; 88.9% had received 1 or more doses of tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis vaccine; 91.9% were up to date with 2 or more doses of measles, mumps & rubella vaccine; and 92.1% were up to date with hepatitis B vaccine, with 3 or more doses.8

Continue to: Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

One study found 5 major false beliefs parents hold about HPV vaccine9:

- Vaccination is not effective at preventing cancer.

- Pap smears are sufficient to prevent cervical cancer.

- HPV vaccination is not safe.

- HPV vaccination is not needed since most infections are naturally cleared by the immune system.

- Eleven to 12 years of age is too young to vaccinate.

There is some evidence that if clinicians actively engage with parents about these concerns and address them head on, same-day vaccination rates can improve.10

We can expect to see HPV-associated OPC decline in the coming years due to the delayed effects on cancer incidence by the HPV vaccine. These anticipated declines will be more dramatic if we can increase the uptake of the HPV vaccine.

1. Ellington TD, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx—United States 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:433-438.

2. CDC. HPV and cancer. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

3. USPSTF. Unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: screening and behavioral counseling interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

4. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed June 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Vaccines and preventable diseases. HPV vaccine recommendations. 2020. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years-United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019:68:718-723.

9. Bednarczyk RA. Addressing HPV vaccine myths: practical information for healthcare providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1628-1638.

10. Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-provider communication of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172312.

1. Ellington TD, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx—United States 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:433-438.

2. CDC. HPV and cancer. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

3. USPSTF. Unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: screening and behavioral counseling interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

4. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed June 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Vaccines and preventable diseases. HPV vaccine recommendations. 2020. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years-United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019:68:718-723.

9. Bednarczyk RA. Addressing HPV vaccine myths: practical information for healthcare providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1628-1638.

10. Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-provider communication of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172312.

Even mild obesity raises severe COVID-19 risks

People with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above are at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19, while a BMI of 35 and higher dramatically increases the risk for death, new research suggests.

The data, from nearly 500 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in March and April 2020, were published in the European Journal of Endocrinology by Matteo Rottoli, MD, of the Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna (Italy), and colleagues.

The data support the recent change by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lower the cutoff for categorizing a person at increased risk from COVID-19 from a BMI of 40 down to 30. However, in the United Kingdom, the National Health Service still lists only a BMI of 40 or above as placing a person at “moderate risk (clinically vulnerable).”

“This finding calls for prevention and treatment strategies to reduce the risk of infection and hospitalization in patients with relevant degrees of obesity, supporting a revision of the BMI cutoff of 40 kg/m2, which was proposed as an independent risk factor for an adverse outcome of COVID-19 in the ... guidelines for social distancing in the United Kingdom: It may be appropriate to include patients with BMI >30 among those at higher risk for COVID-19 severe progression,” the authors wrote.

The study included 482 adults admitted with confirmed COVID-19 to a single Italian hospital between March 1 and April 20, 2020. Of those, 41.9% had a BMI of less than 25 (normal weight), 36.5% had a BMI of 25-29.9 (overweight), and 21.6% had BMI of at least 30 (obese). Of the obese group, 20 (4.1%) had BMIs of at least 35, while 18 patients (3.7%) had BMIs of less than 20 (underweight).

Among those with obesity, 51.9% experienced respiratory failure, 36.4% were admitted to the ICU, 25% required mechanical ventilation, and 29.8% died within 30 days of symptom onset.

Patients with BMIs of at least 30 had significantly increased risks for respiratory failure (odds ratio, 2.48; P = .001), ICU admission (OR, 5.28; P < .001), and death (2.35, P = .017), compared with those with lower BMIs. Within the group classified as obese, the risks of respiratory failure and ICU admission were higher, with BMIs of 30-34.9 (OR, 2.32; P = .004 and OR, 4.96; P < .001, respectively) and for BMIs of at least 35 (OR, 3.24; P = .019 and OR, 6.58; P < .001, respectively).

The risk of death was significantly higher among patients with a BMI of at least 35 (OR, 12.1; P < .001).

Every 1-unit increase in BMI was significantly associated with all outcomes, but there was no significant difference in any outcome between the 25-29.9 BMI category and normal weight. In all models, the BMI cutoff for increased risk was 30.

The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottoli M et al. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-054.

People with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above are at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19, while a BMI of 35 and higher dramatically increases the risk for death, new research suggests.

The data, from nearly 500 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in March and April 2020, were published in the European Journal of Endocrinology by Matteo Rottoli, MD, of the Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna (Italy), and colleagues.

The data support the recent change by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lower the cutoff for categorizing a person at increased risk from COVID-19 from a BMI of 40 down to 30. However, in the United Kingdom, the National Health Service still lists only a BMI of 40 or above as placing a person at “moderate risk (clinically vulnerable).”

“This finding calls for prevention and treatment strategies to reduce the risk of infection and hospitalization in patients with relevant degrees of obesity, supporting a revision of the BMI cutoff of 40 kg/m2, which was proposed as an independent risk factor for an adverse outcome of COVID-19 in the ... guidelines for social distancing in the United Kingdom: It may be appropriate to include patients with BMI >30 among those at higher risk for COVID-19 severe progression,” the authors wrote.

The study included 482 adults admitted with confirmed COVID-19 to a single Italian hospital between March 1 and April 20, 2020. Of those, 41.9% had a BMI of less than 25 (normal weight), 36.5% had a BMI of 25-29.9 (overweight), and 21.6% had BMI of at least 30 (obese). Of the obese group, 20 (4.1%) had BMIs of at least 35, while 18 patients (3.7%) had BMIs of less than 20 (underweight).

Among those with obesity, 51.9% experienced respiratory failure, 36.4% were admitted to the ICU, 25% required mechanical ventilation, and 29.8% died within 30 days of symptom onset.

Patients with BMIs of at least 30 had significantly increased risks for respiratory failure (odds ratio, 2.48; P = .001), ICU admission (OR, 5.28; P < .001), and death (2.35, P = .017), compared with those with lower BMIs. Within the group classified as obese, the risks of respiratory failure and ICU admission were higher, with BMIs of 30-34.9 (OR, 2.32; P = .004 and OR, 4.96; P < .001, respectively) and for BMIs of at least 35 (OR, 3.24; P = .019 and OR, 6.58; P < .001, respectively).

The risk of death was significantly higher among patients with a BMI of at least 35 (OR, 12.1; P < .001).

Every 1-unit increase in BMI was significantly associated with all outcomes, but there was no significant difference in any outcome between the 25-29.9 BMI category and normal weight. In all models, the BMI cutoff for increased risk was 30.

The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottoli M et al. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-054.

People with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above are at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19, while a BMI of 35 and higher dramatically increases the risk for death, new research suggests.

The data, from nearly 500 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in March and April 2020, were published in the European Journal of Endocrinology by Matteo Rottoli, MD, of the Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna (Italy), and colleagues.

The data support the recent change by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lower the cutoff for categorizing a person at increased risk from COVID-19 from a BMI of 40 down to 30. However, in the United Kingdom, the National Health Service still lists only a BMI of 40 or above as placing a person at “moderate risk (clinically vulnerable).”

“This finding calls for prevention and treatment strategies to reduce the risk of infection and hospitalization in patients with relevant degrees of obesity, supporting a revision of the BMI cutoff of 40 kg/m2, which was proposed as an independent risk factor for an adverse outcome of COVID-19 in the ... guidelines for social distancing in the United Kingdom: It may be appropriate to include patients with BMI >30 among those at higher risk for COVID-19 severe progression,” the authors wrote.

The study included 482 adults admitted with confirmed COVID-19 to a single Italian hospital between March 1 and April 20, 2020. Of those, 41.9% had a BMI of less than 25 (normal weight), 36.5% had a BMI of 25-29.9 (overweight), and 21.6% had BMI of at least 30 (obese). Of the obese group, 20 (4.1%) had BMIs of at least 35, while 18 patients (3.7%) had BMIs of less than 20 (underweight).

Among those with obesity, 51.9% experienced respiratory failure, 36.4% were admitted to the ICU, 25% required mechanical ventilation, and 29.8% died within 30 days of symptom onset.

Patients with BMIs of at least 30 had significantly increased risks for respiratory failure (odds ratio, 2.48; P = .001), ICU admission (OR, 5.28; P < .001), and death (2.35, P = .017), compared with those with lower BMIs. Within the group classified as obese, the risks of respiratory failure and ICU admission were higher, with BMIs of 30-34.9 (OR, 2.32; P = .004 and OR, 4.96; P < .001, respectively) and for BMIs of at least 35 (OR, 3.24; P = .019 and OR, 6.58; P < .001, respectively).

The risk of death was significantly higher among patients with a BMI of at least 35 (OR, 12.1; P < .001).

Every 1-unit increase in BMI was significantly associated with all outcomes, but there was no significant difference in any outcome between the 25-29.9 BMI category and normal weight. In all models, the BMI cutoff for increased risk was 30.

The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Rottoli M et al. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-054.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGY

Consider adverse childhood experiences during the pandemic

We live in historic times. A worldwide pandemic is surging in the United States, with millions infected and the world’s highest death rate. Many of our hospitals are overwhelmed. Schools have been closed for months. Businesses are struggling, and unemployment is at record levels. The murder of George Floyd unleashed an outpouring of grief and rage over police brutality and structural racism.

It is ironic that this age of adversity emerged at the same time that efforts to assess and address childhood adversity are gaining momentum. The effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been well known for decades, but only recently have efforts at universal screening been initiated in primary care offices around the country. The multiple crises we face have made this work more pressing than ever. And

While there has long been awareness, especially among pediatricians, of the social determinants of health, it was only 1995 when Robert F. Anda, MD, and Vincent J. Felitti, MD, set about studying over 13,000 adult patients at Kaiser Permanente to understand the relationship between childhood trauma and chronic health problems in adulthood. In 1998 they published the results of this landmark study, establishing that childhood trauma was common and that it predicted chronic diseases and psychosocial problems in adulthood1.

They detailed 10 specific ACEs, and a patient’s ACE score was determined by how many of these experiences they had before they turned 18 years: neglect (emotional or physical), abuse (emotional, physical or sexual), and household dysfunction (parental divorce, incarceration of a parent, domestic violence, parental mental illness, or parental substance abuse). They found that more than half of adults studied had a score of at least 1, and 6% had scores of 4 or more. Those adults with an ACE score of 4 or more are twice as likely to be obese, twice as likely to smoke, and seven times as likely to abuse alcohol as the rest of the population. They are 4 times as likely to have emphysema, 5 times as likely to have depression, and 12 times as likely to attempt suicide. They have higher rates of heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. Those with ACE scores of 6 or more have their life expectancy shortened by an average of 20 years.

The value of knowing about these risk factors would seem self-evident; it would inform a patient’s health care from screening for cancer or heart disease, referral for mild depressive symptoms, and counseling about alcohol consumption. But this research did not lead to the establishment of routine screening for childhood adversity in primary care practices. There are multiple reasons for this, including growing pressure on physician time and discomfort with starting conversations about potentially traumatic material. But perhaps the greatest obstacle has been uncertainty about what to offer patients who screened in. What is the treatment for a high ACE score?

Even without treatments, we have learned much about childhood adversity since Dr. Anda and Dr. Felitti published their landmark study. Other more chronic adverse childhood experiences also contribute to adult health risk, such as poverty, homelessness, discrimination, community violence, parental chronic illness, or disability or placement in foster care. Having a high ACE score does not only affect health in adulthood. Children with an ACE score of 4 are 2 times as likely to have asthma2,3 and allergies3, 2 times as likely to be obese4, 3 times as likely to have headaches3 and dental problems5,6, 4 times as likely to have depression7,8, 5 times as likely to have ADHD8,9, 7 times as likely to have high rates of school absenteeism3 and aggression10, and over 30 times as likely to have learning or behavioral problems at school4. There is a growing body of knowledge about how chronic, severe stress in childhood affects can lead to pathological alterations in neuroendocrine and immune function. But this has not led to any concrete treatments that may be preventive or reparative.

Movement toward expanding screening nonetheless has accelerated. In California, Nadine Burke-Harris, MD, a pediatrician who studied ACEs and children’s health was named the state’s first Surgeon General in 2019 and spearheaded an effort to make screening for ACEs easier. Starting in 2020, MediCal will pay for annual screenings, and the state is offering training and resources on how to screen and what to do with the information to help patients and families.

The coronavirus pandemic has only highlighted the risks of childhood adversity. The burden of infection and mortality has been borne disproportionately by people of color and those with multiple chronic medical conditions (obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, etc.). While viruses do not discriminate, they are more likely to infect those with higher risk of exposure and to kill those who are physiologically vulnerable.

And the pandemic increases the risk for adversity for today’s children and families. When children cannot attend school, financially vulnerable parents may have to choose between supervising them or feeding them. Families who suddenly are all in a small apartment together without school or other outside supports may be at higher risk for domestic violence and child abuse. Unemployment and financial uncertainty will increase the rates of substance abuse and depression amongst parents. And the serious illness or death of a parent will be a more common event for children in the year ahead. One of these risk factors may increase the likelihood of others.

Beyond the obvious need for substantial policy changes focused on housing, education, and health care, And resilience can build on itself, as children face subsequent challenges with the support of caring connected adults.

The critical first step is asking. Then listen calmly and supportively, normalizing for parents and children how common these experiences are. Explain how they affect health and well-being. Explain that adversity and its consequences are not their fault. Then educate them about what is in their control: the skills they can practice to buffer against the consequences of adversity and build resilience. They sound simple, but still require effort and work. And the pandemic has created some difficulty (social distancing) and opportunity (more family time, fewer school demands).

Sleep

Help parents establish and protect consistent, restful sleep for their children. They can set a consistent bedtime and a calm routine, with screens all off at least 30 minutes before sleep and reading before sleep. Restful sleep is physiologically and psychologically protective to everyone in a family.

Movement

Beyond directly improving physical health, establishing habits of exercise – especially outside – every day can effectively manage ongoing stress, build skills of self-regulation, and help with sleep.

Find out what parents and their children like to do together (walking the dog, shooting hoops, even dancing) and help them devise ways to create family routines around exercise.

Nutrition

Food should be a source of pleasure, but stress can make food into a source of comfort or escape. Help parents to create realistic ways to consistently offer healthy family meals and discourage unhealthy habits.

Even small changes like water instead of soda can help, and there are nutritional and emotional benefits to eating a healthy breakfast or dinner together as a family.

Connections

Nourishing social connections are protective. Help parents think about protecting time to spend with their children for talking, playing games, or even singing.

They should support their children’s connections to other caring adults, through community organizations (church, community centers, or sports), and they should know who their children’s reliable friends are. Parents will benefit from these supports for themselves, which in turn will benefit the full family.

Self-awareness

Activities that cultivate mindfulness are protective. Parents can simply ask how their children are feeling, physically or emotionally, and be able to bear it when it is uncomfortable. Work towards nonjudgmental awareness of how they are feeling. Learning what is relaxing or recharging for them (exercise, music, a hot bath, a good book, time with a friend) will protect against defaulting into maladaptive coping such as escape, numbing, or avoidance.

Of course, if you learn about symptoms that suggest PTSD, depression, or addiction, you should help your patient connect with effective treatment. The difficulty of referring to a mental health provider does not mean you should not try and bring as many people onto the team and into the orbit of the child and family at risk. It may be easier to access some therapy given the new availability of telemedicine visits across many more systems of care. Although the heaviest burdens of adversity are not being borne equally, the fact that adversity is currently a shared experience makes this a moment of promise.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Swick and Dr. Jellinek had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245-58.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114: 379-84.

3. BMC Public Health. 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5699-8.

4. Child Abuse Negl. 2011 Jun;35(6):408-13.

5. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:193-9.

6. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018 Oct;46(5): 442-8.

7. Pediatrics 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4016.

8. Matern Child Health J. 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1915-7.

9. Acad Pediatr. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013.

10. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597.

This article was updated 7/27/2020.

We live in historic times. A worldwide pandemic is surging in the United States, with millions infected and the world’s highest death rate. Many of our hospitals are overwhelmed. Schools have been closed for months. Businesses are struggling, and unemployment is at record levels. The murder of George Floyd unleashed an outpouring of grief and rage over police brutality and structural racism.

It is ironic that this age of adversity emerged at the same time that efforts to assess and address childhood adversity are gaining momentum. The effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been well known for decades, but only recently have efforts at universal screening been initiated in primary care offices around the country. The multiple crises we face have made this work more pressing than ever. And

While there has long been awareness, especially among pediatricians, of the social determinants of health, it was only 1995 when Robert F. Anda, MD, and Vincent J. Felitti, MD, set about studying over 13,000 adult patients at Kaiser Permanente to understand the relationship between childhood trauma and chronic health problems in adulthood. In 1998 they published the results of this landmark study, establishing that childhood trauma was common and that it predicted chronic diseases and psychosocial problems in adulthood1.

They detailed 10 specific ACEs, and a patient’s ACE score was determined by how many of these experiences they had before they turned 18 years: neglect (emotional or physical), abuse (emotional, physical or sexual), and household dysfunction (parental divorce, incarceration of a parent, domestic violence, parental mental illness, or parental substance abuse). They found that more than half of adults studied had a score of at least 1, and 6% had scores of 4 or more. Those adults with an ACE score of 4 or more are twice as likely to be obese, twice as likely to smoke, and seven times as likely to abuse alcohol as the rest of the population. They are 4 times as likely to have emphysema, 5 times as likely to have depression, and 12 times as likely to attempt suicide. They have higher rates of heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. Those with ACE scores of 6 or more have their life expectancy shortened by an average of 20 years.

The value of knowing about these risk factors would seem self-evident; it would inform a patient’s health care from screening for cancer or heart disease, referral for mild depressive symptoms, and counseling about alcohol consumption. But this research did not lead to the establishment of routine screening for childhood adversity in primary care practices. There are multiple reasons for this, including growing pressure on physician time and discomfort with starting conversations about potentially traumatic material. But perhaps the greatest obstacle has been uncertainty about what to offer patients who screened in. What is the treatment for a high ACE score?

Even without treatments, we have learned much about childhood adversity since Dr. Anda and Dr. Felitti published their landmark study. Other more chronic adverse childhood experiences also contribute to adult health risk, such as poverty, homelessness, discrimination, community violence, parental chronic illness, or disability or placement in foster care. Having a high ACE score does not only affect health in adulthood. Children with an ACE score of 4 are 2 times as likely to have asthma2,3 and allergies3, 2 times as likely to be obese4, 3 times as likely to have headaches3 and dental problems5,6, 4 times as likely to have depression7,8, 5 times as likely to have ADHD8,9, 7 times as likely to have high rates of school absenteeism3 and aggression10, and over 30 times as likely to have learning or behavioral problems at school4. There is a growing body of knowledge about how chronic, severe stress in childhood affects can lead to pathological alterations in neuroendocrine and immune function. But this has not led to any concrete treatments that may be preventive or reparative.

Movement toward expanding screening nonetheless has accelerated. In California, Nadine Burke-Harris, MD, a pediatrician who studied ACEs and children’s health was named the state’s first Surgeon General in 2019 and spearheaded an effort to make screening for ACEs easier. Starting in 2020, MediCal will pay for annual screenings, and the state is offering training and resources on how to screen and what to do with the information to help patients and families.

The coronavirus pandemic has only highlighted the risks of childhood adversity. The burden of infection and mortality has been borne disproportionately by people of color and those with multiple chronic medical conditions (obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, etc.). While viruses do not discriminate, they are more likely to infect those with higher risk of exposure and to kill those who are physiologically vulnerable.

And the pandemic increases the risk for adversity for today’s children and families. When children cannot attend school, financially vulnerable parents may have to choose between supervising them or feeding them. Families who suddenly are all in a small apartment together without school or other outside supports may be at higher risk for domestic violence and child abuse. Unemployment and financial uncertainty will increase the rates of substance abuse and depression amongst parents. And the serious illness or death of a parent will be a more common event for children in the year ahead. One of these risk factors may increase the likelihood of others.

Beyond the obvious need for substantial policy changes focused on housing, education, and health care, And resilience can build on itself, as children face subsequent challenges with the support of caring connected adults.

The critical first step is asking. Then listen calmly and supportively, normalizing for parents and children how common these experiences are. Explain how they affect health and well-being. Explain that adversity and its consequences are not their fault. Then educate them about what is in their control: the skills they can practice to buffer against the consequences of adversity and build resilience. They sound simple, but still require effort and work. And the pandemic has created some difficulty (social distancing) and opportunity (more family time, fewer school demands).

Sleep

Help parents establish and protect consistent, restful sleep for their children. They can set a consistent bedtime and a calm routine, with screens all off at least 30 minutes before sleep and reading before sleep. Restful sleep is physiologically and psychologically protective to everyone in a family.

Movement

Beyond directly improving physical health, establishing habits of exercise – especially outside – every day can effectively manage ongoing stress, build skills of self-regulation, and help with sleep.

Find out what parents and their children like to do together (walking the dog, shooting hoops, even dancing) and help them devise ways to create family routines around exercise.

Nutrition

Food should be a source of pleasure, but stress can make food into a source of comfort or escape. Help parents to create realistic ways to consistently offer healthy family meals and discourage unhealthy habits.

Even small changes like water instead of soda can help, and there are nutritional and emotional benefits to eating a healthy breakfast or dinner together as a family.

Connections

Nourishing social connections are protective. Help parents think about protecting time to spend with their children for talking, playing games, or even singing.

They should support their children’s connections to other caring adults, through community organizations (church, community centers, or sports), and they should know who their children’s reliable friends are. Parents will benefit from these supports for themselves, which in turn will benefit the full family.

Self-awareness

Activities that cultivate mindfulness are protective. Parents can simply ask how their children are feeling, physically or emotionally, and be able to bear it when it is uncomfortable. Work towards nonjudgmental awareness of how they are feeling. Learning what is relaxing or recharging for them (exercise, music, a hot bath, a good book, time with a friend) will protect against defaulting into maladaptive coping such as escape, numbing, or avoidance.

Of course, if you learn about symptoms that suggest PTSD, depression, or addiction, you should help your patient connect with effective treatment. The difficulty of referring to a mental health provider does not mean you should not try and bring as many people onto the team and into the orbit of the child and family at risk. It may be easier to access some therapy given the new availability of telemedicine visits across many more systems of care. Although the heaviest burdens of adversity are not being borne equally, the fact that adversity is currently a shared experience makes this a moment of promise.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Swick and Dr. Jellinek had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245-58.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114: 379-84.

3. BMC Public Health. 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5699-8.

4. Child Abuse Negl. 2011 Jun;35(6):408-13.

5. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:193-9.

6. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018 Oct;46(5): 442-8.

7. Pediatrics 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4016.

8. Matern Child Health J. 2016 Apr. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1915-7.

9. Acad Pediatr. 2017 May-Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.08.013.

10. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597.

This article was updated 7/27/2020.

We live in historic times. A worldwide pandemic is surging in the United States, with millions infected and the world’s highest death rate. Many of our hospitals are overwhelmed. Schools have been closed for months. Businesses are struggling, and unemployment is at record levels. The murder of George Floyd unleashed an outpouring of grief and rage over police brutality and structural racism.

It is ironic that this age of adversity emerged at the same time that efforts to assess and address childhood adversity are gaining momentum. The effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been well known for decades, but only recently have efforts at universal screening been initiated in primary care offices around the country. The multiple crises we face have made this work more pressing than ever. And

While there has long been awareness, especially among pediatricians, of the social determinants of health, it was only 1995 when Robert F. Anda, MD, and Vincent J. Felitti, MD, set about studying over 13,000 adult patients at Kaiser Permanente to understand the relationship between childhood trauma and chronic health problems in adulthood. In 1998 they published the results of this landmark study, establishing that childhood trauma was common and that it predicted chronic diseases and psychosocial problems in adulthood1.

They detailed 10 specific ACEs, and a patient’s ACE score was determined by how many of these experiences they had before they turned 18 years: neglect (emotional or physical), abuse (emotional, physical or sexual), and household dysfunction (parental divorce, incarceration of a parent, domestic violence, parental mental illness, or parental substance abuse). They found that more than half of adults studied had a score of at least 1, and 6% had scores of 4 or more. Those adults with an ACE score of 4 or more are twice as likely to be obese, twice as likely to smoke, and seven times as likely to abuse alcohol as the rest of the population. They are 4 times as likely to have emphysema, 5 times as likely to have depression, and 12 times as likely to attempt suicide. They have higher rates of heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. Those with ACE scores of 6 or more have their life expectancy shortened by an average of 20 years.

The value of knowing about these risk factors would seem self-evident; it would inform a patient’s health care from screening for cancer or heart disease, referral for mild depressive symptoms, and counseling about alcohol consumption. But this research did not lead to the establishment of routine screening for childhood adversity in primary care practices. There are multiple reasons for this, including growing pressure on physician time and discomfort with starting conversations about potentially traumatic material. But perhaps the greatest obstacle has been uncertainty about what to offer patients who screened in. What is the treatment for a high ACE score?