User login

The 2021 Medicare proposed rule: The good, the bad, and the ugly

As most of you know, Medicare publishes its proposed rule, which determines the physician fee schedule, around July 1 each year, accepts comments for 60 days, and then publishes a final rule on or around Nov. 1, which becomes final on Jan. 1 of the following year. The proposed rule is watched closely and has great impact, because not only are Medicare fees based on the rule, but most private insurances are based on Medicare.

This year’s proposed rule, announced in early August, is extraordinary by any past standard. It can be found here.

It cuts the conversion factor (which is what the work, practice expense, and malpractice values are multiplied by to get a payment) by 10.6%, from $36.09 to $32.26. This is necessary to maintain “budget neutrality” since there is a fixed pool of money, and payments for cognitive services are increasing. The overall effect on dermatology is a 2% cut, which is mild, compared with other specialties, such as nurse anesthetists and radiologists, both with an 11% decrease; chiropractors, with a 10% decrease; and interventional radiology, pathology, physical and occupational therapy, and cardiac surgery, all with a 9% decrease. General surgery will see a 7% decrease. Those with major increases are endocrinology, with a 17% increase; rheumatology, with a 16% increase; and hematology/oncology, with a 14% increase.

The overall push by CMS (and the relative value update committee) is to improve the pay for cognitive services, that is evaluation and management (E/M) services. Since dermatology also provides such services, the effect of the proposed rule will vary dramatically depending on your case mix. I must also point out that, since existing overhead is relatively fixed, say at 50%, a 10% decrease in revenue may translate into a 20% loss in physician income.

The good

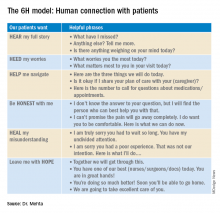

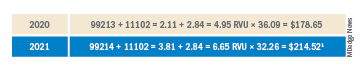

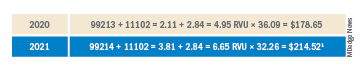

Simplified coding and billing requirements for E/M visits will go into effect Jan. 1, 2021. For dermatology, any visit where a decision to do a minor procedure or prescribe a medication takes place will become a level 4 visit. Most of the useless documentation requirements and need to examine multiple organ systems will be eliminated. The most common E/M code currently used by dermatologists is a level 3, and this will on average move up to a level 4. Thus, general dermatology will benefit from the new rule. For example, if a dermatologist sees a patient and does a tangential biopsy of the skin, the payment will be $214.52, compared with $178.65 in 2020.

The bad

As mentioned above, the impact will vary by case mix. Those doing a lot of surgery will see a much larger cut. Mohs surgeons, for example will see about a 6.5% decrease.1

Aggravating the cuts to surgery is the fact that, while CMS has bolstered the pay for E/M stand-alone codes, they did not increase the reimbursement level of the built-in follow-up visits inside the 10- and 90-day global periods.

The ugly

Procedure codes with a lot of practice expense built into them, such as Mohs and reconstruction, are not hit as hard by the conversion factor cut because the practice expense is generally spared. There is much less practice expense in a pathology code so dermatopathology faces the most severe cuts. Pathology and other specialties that do not generally bill office/outpatient E/M codes are estimated to see the greatest decrease in payment in 2021.

Code 88305, the most common dermatopathology code, will decrease overall from $71.46 to $66.78 (–6.5%). Digging a little deeper, we find that the technical charge (the payment to process and make the slide) actually increases from $32.12 to $32.26, but the professional component (the interpretation of the slide and report generation) decreases from $39.34 to $34.52 (–12.3%).

I must also point out that this proposed rule allows for nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), physician assistants (PAs), and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) to supervise the performance of diagnostic tests in addition to physicians. I wonder if we will see an increase in billing of dermatopathology by the untrained.

Adding more confusion – and an additional hit to hospital-based practices – is the federal appeals court decision affirming the ability of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to mandate site-neutral payments for E/M codes. This means that hospital-affiliated practices, which used to enjoy payment of up to 114% more than offices, will be paid the same as offices. This will save CMS $300 million, but these savings will not be flowing back into the physician fee schedule.

Fixing this will require congressional action since CMS is bound by law to maintain budget neutrality. The specialty societies saw this coming and have already been lobbying furiously to waive budget neutrality requirements, especially in this time of a pandemic that has had an adverse impact on physicians. This is noted in detail on the AADA website, accessible to AAD members.

Since this will take a legislative fix, you should contact your congressional representative or senator and ask them to enact legislation to waive Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements to apply the increased E/M adjustment to all 10- and 90-day global code values. You might also inquire where the $300 million saved by site neutral payment reform will go, and suggest applying it towards restoring the conversion factor to a more normal number.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

1. Calculations and tables courtesy of Brent Moody, M.D., AAD AMA relative value update committee practice expense representative and specialist.

As most of you know, Medicare publishes its proposed rule, which determines the physician fee schedule, around July 1 each year, accepts comments for 60 days, and then publishes a final rule on or around Nov. 1, which becomes final on Jan. 1 of the following year. The proposed rule is watched closely and has great impact, because not only are Medicare fees based on the rule, but most private insurances are based on Medicare.

This year’s proposed rule, announced in early August, is extraordinary by any past standard. It can be found here.

It cuts the conversion factor (which is what the work, practice expense, and malpractice values are multiplied by to get a payment) by 10.6%, from $36.09 to $32.26. This is necessary to maintain “budget neutrality” since there is a fixed pool of money, and payments for cognitive services are increasing. The overall effect on dermatology is a 2% cut, which is mild, compared with other specialties, such as nurse anesthetists and radiologists, both with an 11% decrease; chiropractors, with a 10% decrease; and interventional radiology, pathology, physical and occupational therapy, and cardiac surgery, all with a 9% decrease. General surgery will see a 7% decrease. Those with major increases are endocrinology, with a 17% increase; rheumatology, with a 16% increase; and hematology/oncology, with a 14% increase.

The overall push by CMS (and the relative value update committee) is to improve the pay for cognitive services, that is evaluation and management (E/M) services. Since dermatology also provides such services, the effect of the proposed rule will vary dramatically depending on your case mix. I must also point out that, since existing overhead is relatively fixed, say at 50%, a 10% decrease in revenue may translate into a 20% loss in physician income.

The good

Simplified coding and billing requirements for E/M visits will go into effect Jan. 1, 2021. For dermatology, any visit where a decision to do a minor procedure or prescribe a medication takes place will become a level 4 visit. Most of the useless documentation requirements and need to examine multiple organ systems will be eliminated. The most common E/M code currently used by dermatologists is a level 3, and this will on average move up to a level 4. Thus, general dermatology will benefit from the new rule. For example, if a dermatologist sees a patient and does a tangential biopsy of the skin, the payment will be $214.52, compared with $178.65 in 2020.

The bad

As mentioned above, the impact will vary by case mix. Those doing a lot of surgery will see a much larger cut. Mohs surgeons, for example will see about a 6.5% decrease.1

Aggravating the cuts to surgery is the fact that, while CMS has bolstered the pay for E/M stand-alone codes, they did not increase the reimbursement level of the built-in follow-up visits inside the 10- and 90-day global periods.

The ugly

Procedure codes with a lot of practice expense built into them, such as Mohs and reconstruction, are not hit as hard by the conversion factor cut because the practice expense is generally spared. There is much less practice expense in a pathology code so dermatopathology faces the most severe cuts. Pathology and other specialties that do not generally bill office/outpatient E/M codes are estimated to see the greatest decrease in payment in 2021.

Code 88305, the most common dermatopathology code, will decrease overall from $71.46 to $66.78 (–6.5%). Digging a little deeper, we find that the technical charge (the payment to process and make the slide) actually increases from $32.12 to $32.26, but the professional component (the interpretation of the slide and report generation) decreases from $39.34 to $34.52 (–12.3%).

I must also point out that this proposed rule allows for nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), physician assistants (PAs), and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) to supervise the performance of diagnostic tests in addition to physicians. I wonder if we will see an increase in billing of dermatopathology by the untrained.

Adding more confusion – and an additional hit to hospital-based practices – is the federal appeals court decision affirming the ability of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to mandate site-neutral payments for E/M codes. This means that hospital-affiliated practices, which used to enjoy payment of up to 114% more than offices, will be paid the same as offices. This will save CMS $300 million, but these savings will not be flowing back into the physician fee schedule.

Fixing this will require congressional action since CMS is bound by law to maintain budget neutrality. The specialty societies saw this coming and have already been lobbying furiously to waive budget neutrality requirements, especially in this time of a pandemic that has had an adverse impact on physicians. This is noted in detail on the AADA website, accessible to AAD members.

Since this will take a legislative fix, you should contact your congressional representative or senator and ask them to enact legislation to waive Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements to apply the increased E/M adjustment to all 10- and 90-day global code values. You might also inquire where the $300 million saved by site neutral payment reform will go, and suggest applying it towards restoring the conversion factor to a more normal number.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

1. Calculations and tables courtesy of Brent Moody, M.D., AAD AMA relative value update committee practice expense representative and specialist.

As most of you know, Medicare publishes its proposed rule, which determines the physician fee schedule, around July 1 each year, accepts comments for 60 days, and then publishes a final rule on or around Nov. 1, which becomes final on Jan. 1 of the following year. The proposed rule is watched closely and has great impact, because not only are Medicare fees based on the rule, but most private insurances are based on Medicare.

This year’s proposed rule, announced in early August, is extraordinary by any past standard. It can be found here.

It cuts the conversion factor (which is what the work, practice expense, and malpractice values are multiplied by to get a payment) by 10.6%, from $36.09 to $32.26. This is necessary to maintain “budget neutrality” since there is a fixed pool of money, and payments for cognitive services are increasing. The overall effect on dermatology is a 2% cut, which is mild, compared with other specialties, such as nurse anesthetists and radiologists, both with an 11% decrease; chiropractors, with a 10% decrease; and interventional radiology, pathology, physical and occupational therapy, and cardiac surgery, all with a 9% decrease. General surgery will see a 7% decrease. Those with major increases are endocrinology, with a 17% increase; rheumatology, with a 16% increase; and hematology/oncology, with a 14% increase.

The overall push by CMS (and the relative value update committee) is to improve the pay for cognitive services, that is evaluation and management (E/M) services. Since dermatology also provides such services, the effect of the proposed rule will vary dramatically depending on your case mix. I must also point out that, since existing overhead is relatively fixed, say at 50%, a 10% decrease in revenue may translate into a 20% loss in physician income.

The good

Simplified coding and billing requirements for E/M visits will go into effect Jan. 1, 2021. For dermatology, any visit where a decision to do a minor procedure or prescribe a medication takes place will become a level 4 visit. Most of the useless documentation requirements and need to examine multiple organ systems will be eliminated. The most common E/M code currently used by dermatologists is a level 3, and this will on average move up to a level 4. Thus, general dermatology will benefit from the new rule. For example, if a dermatologist sees a patient and does a tangential biopsy of the skin, the payment will be $214.52, compared with $178.65 in 2020.

The bad

As mentioned above, the impact will vary by case mix. Those doing a lot of surgery will see a much larger cut. Mohs surgeons, for example will see about a 6.5% decrease.1

Aggravating the cuts to surgery is the fact that, while CMS has bolstered the pay for E/M stand-alone codes, they did not increase the reimbursement level of the built-in follow-up visits inside the 10- and 90-day global periods.

The ugly

Procedure codes with a lot of practice expense built into them, such as Mohs and reconstruction, are not hit as hard by the conversion factor cut because the practice expense is generally spared. There is much less practice expense in a pathology code so dermatopathology faces the most severe cuts. Pathology and other specialties that do not generally bill office/outpatient E/M codes are estimated to see the greatest decrease in payment in 2021.

Code 88305, the most common dermatopathology code, will decrease overall from $71.46 to $66.78 (–6.5%). Digging a little deeper, we find that the technical charge (the payment to process and make the slide) actually increases from $32.12 to $32.26, but the professional component (the interpretation of the slide and report generation) decreases from $39.34 to $34.52 (–12.3%).

I must also point out that this proposed rule allows for nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), physician assistants (PAs), and certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) to supervise the performance of diagnostic tests in addition to physicians. I wonder if we will see an increase in billing of dermatopathology by the untrained.

Adding more confusion – and an additional hit to hospital-based practices – is the federal appeals court decision affirming the ability of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to mandate site-neutral payments for E/M codes. This means that hospital-affiliated practices, which used to enjoy payment of up to 114% more than offices, will be paid the same as offices. This will save CMS $300 million, but these savings will not be flowing back into the physician fee schedule.

Fixing this will require congressional action since CMS is bound by law to maintain budget neutrality. The specialty societies saw this coming and have already been lobbying furiously to waive budget neutrality requirements, especially in this time of a pandemic that has had an adverse impact on physicians. This is noted in detail on the AADA website, accessible to AAD members.

Since this will take a legislative fix, you should contact your congressional representative or senator and ask them to enact legislation to waive Medicare’s budget neutrality requirements to apply the increased E/M adjustment to all 10- and 90-day global code values. You might also inquire where the $300 million saved by site neutral payment reform will go, and suggest applying it towards restoring the conversion factor to a more normal number.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Reference

1. Calculations and tables courtesy of Brent Moody, M.D., AAD AMA relative value update committee practice expense representative and specialist.

Depressed Shiny Scars and Crusted Erosions

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

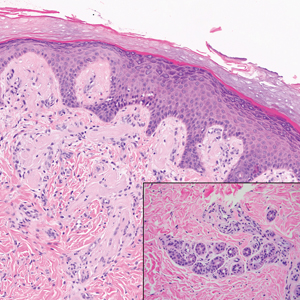

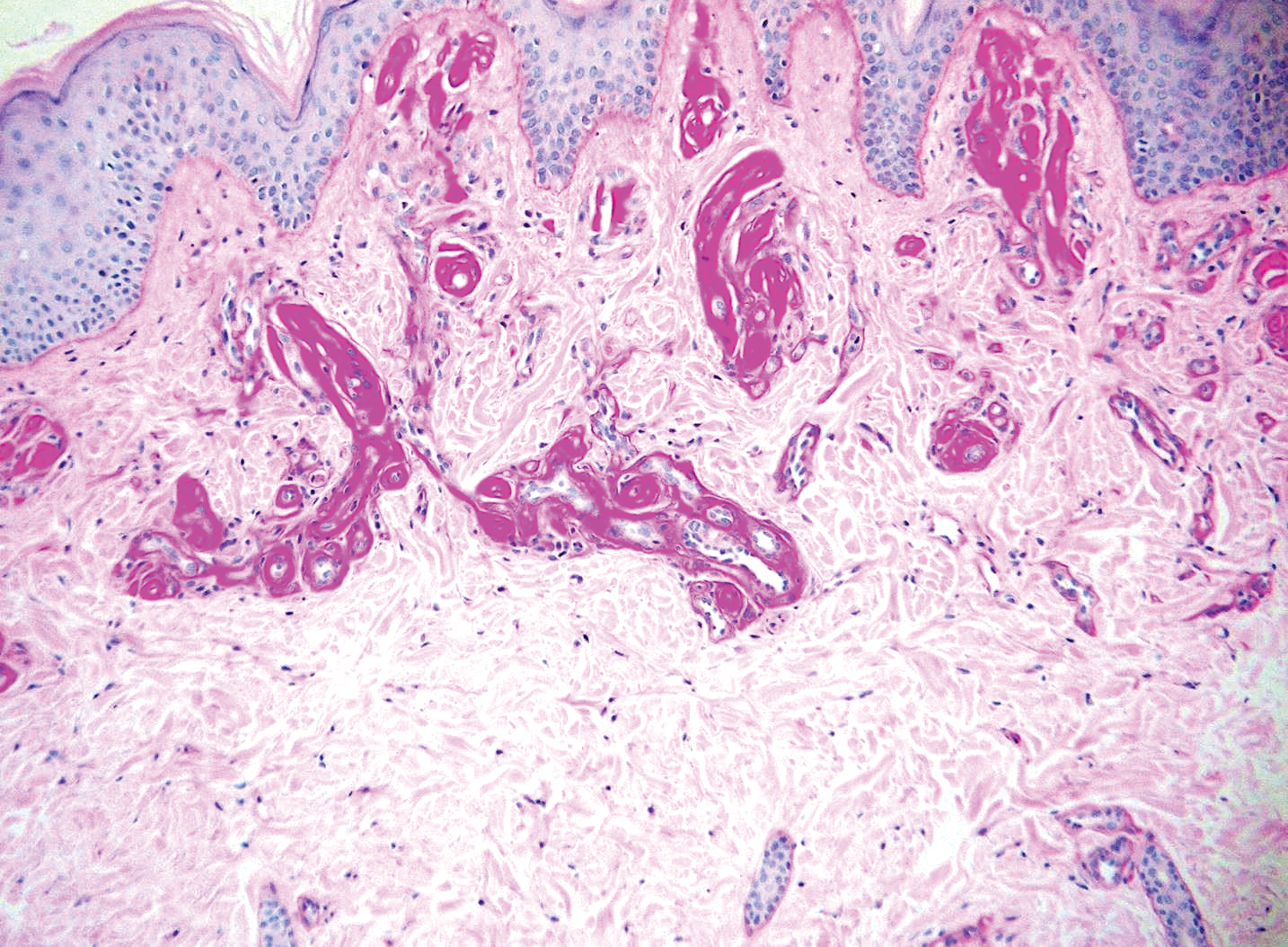

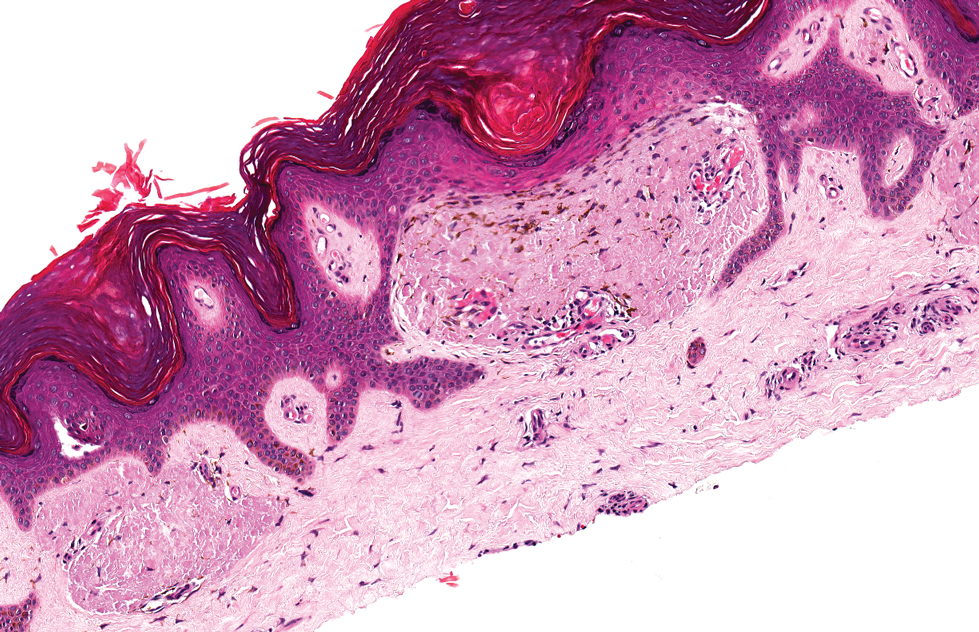

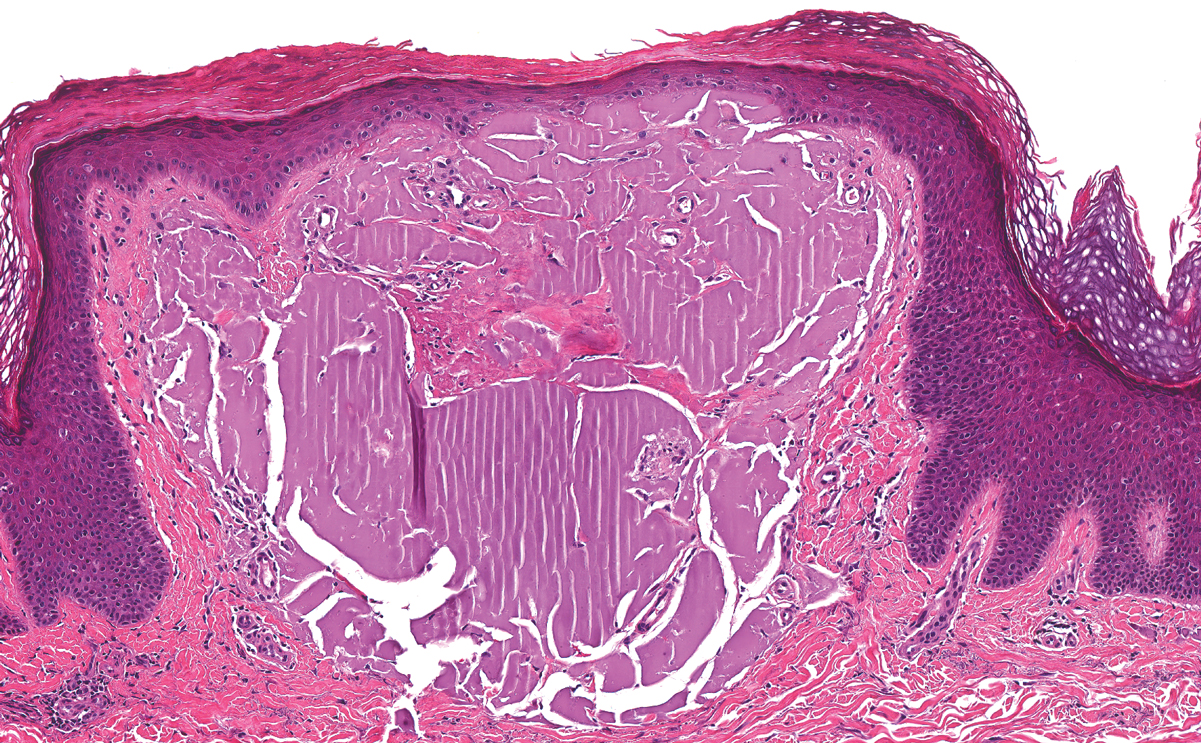

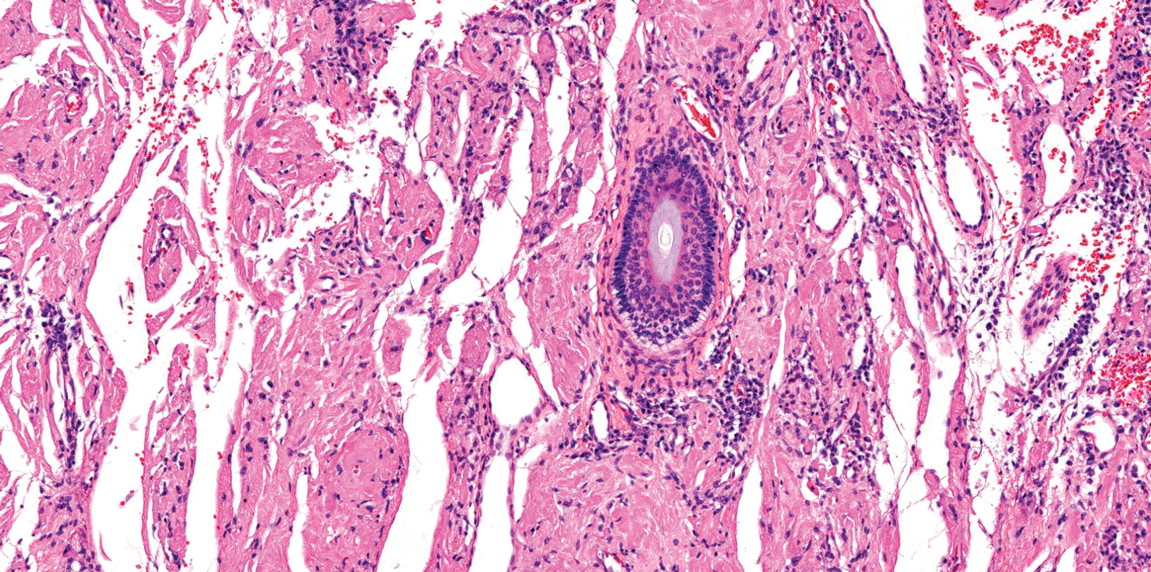

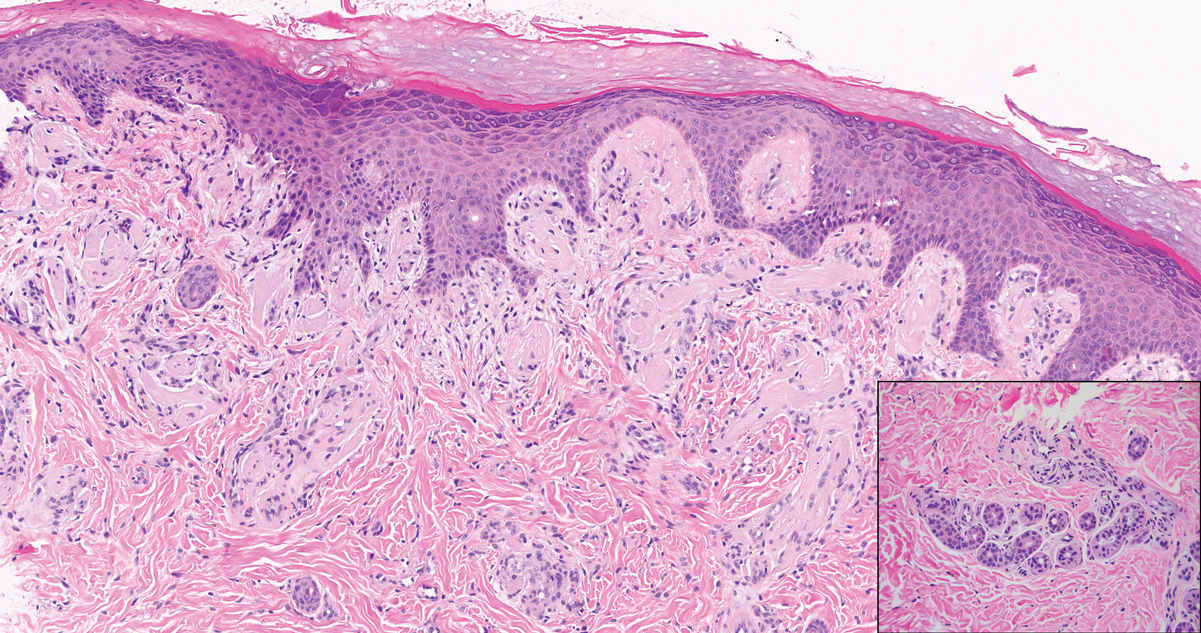

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

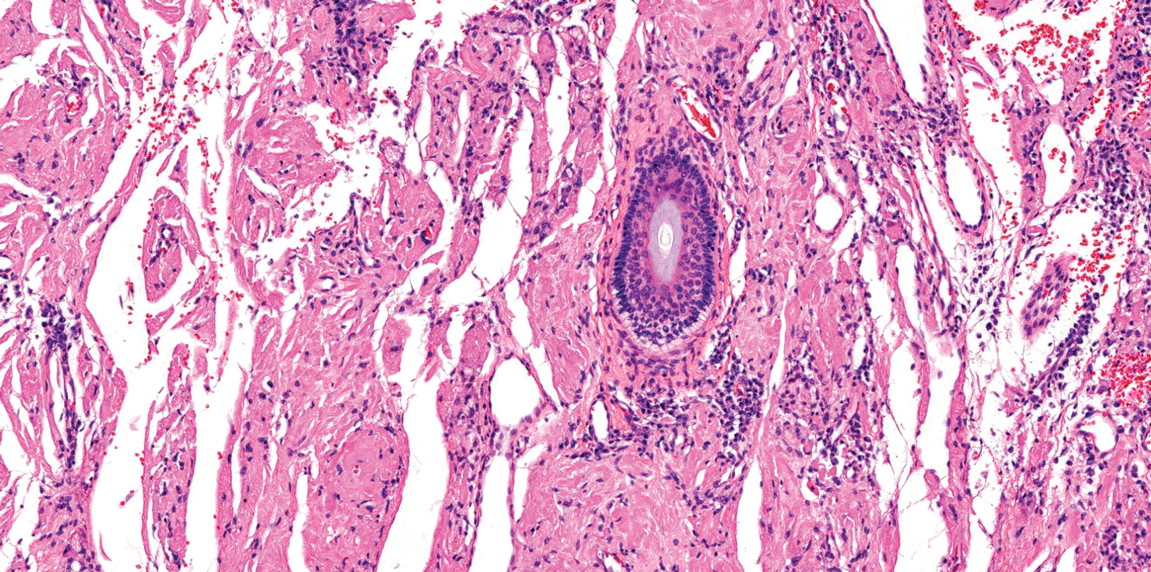

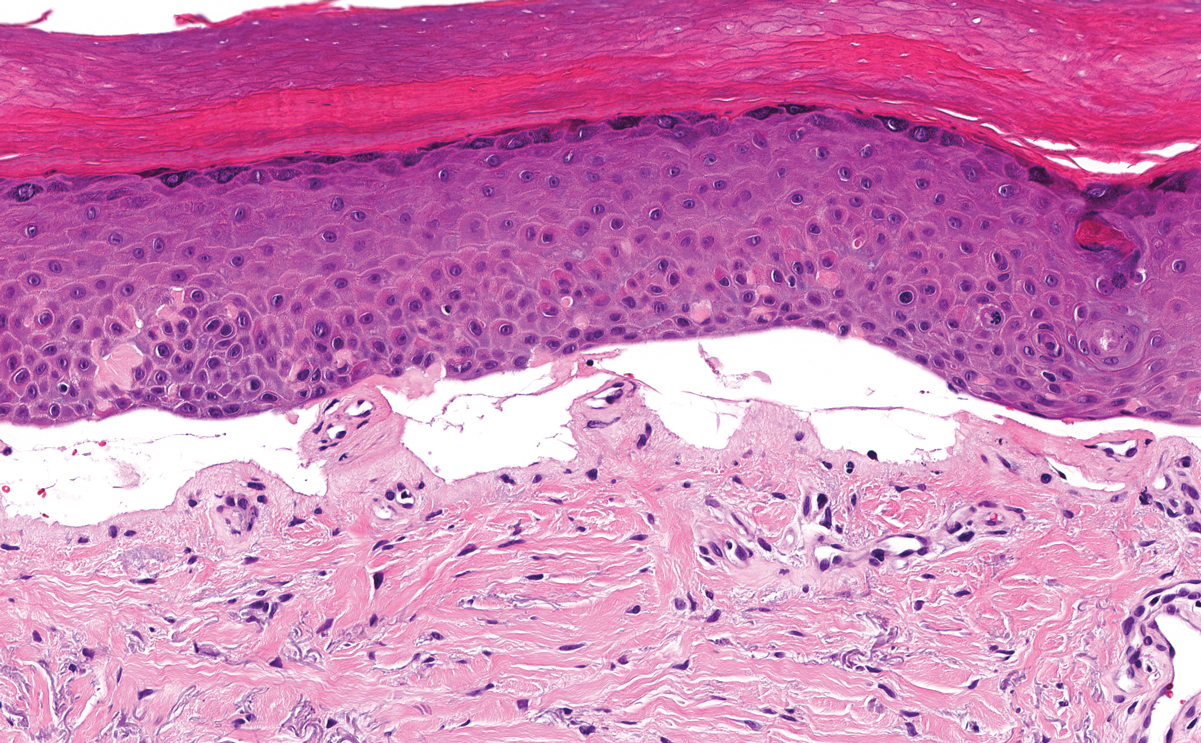

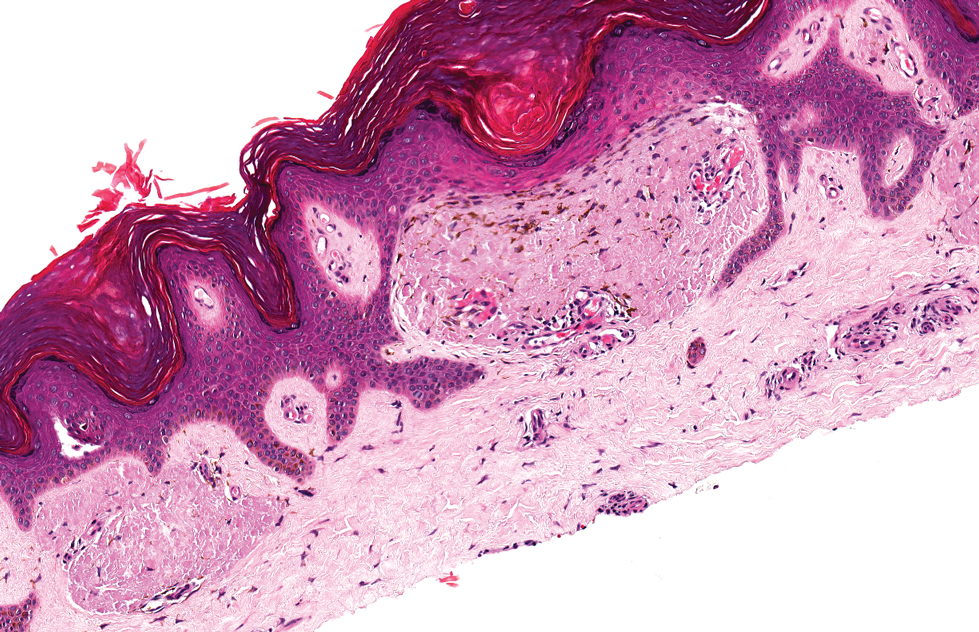

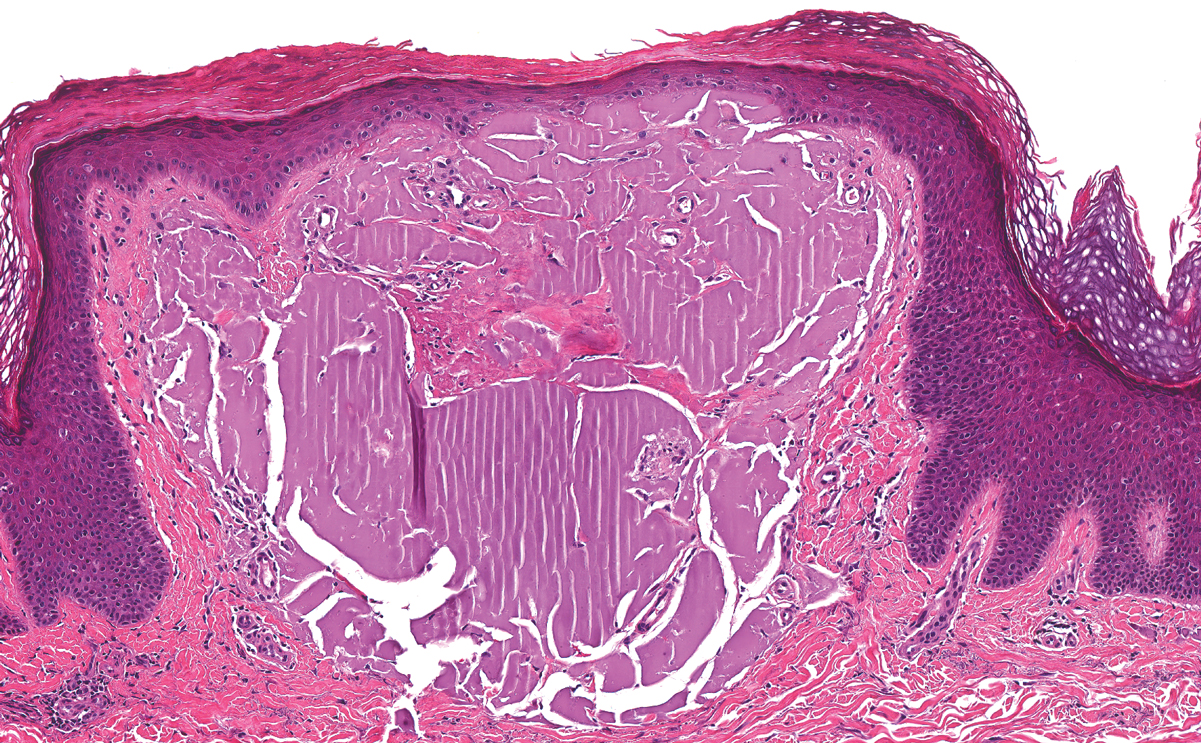

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

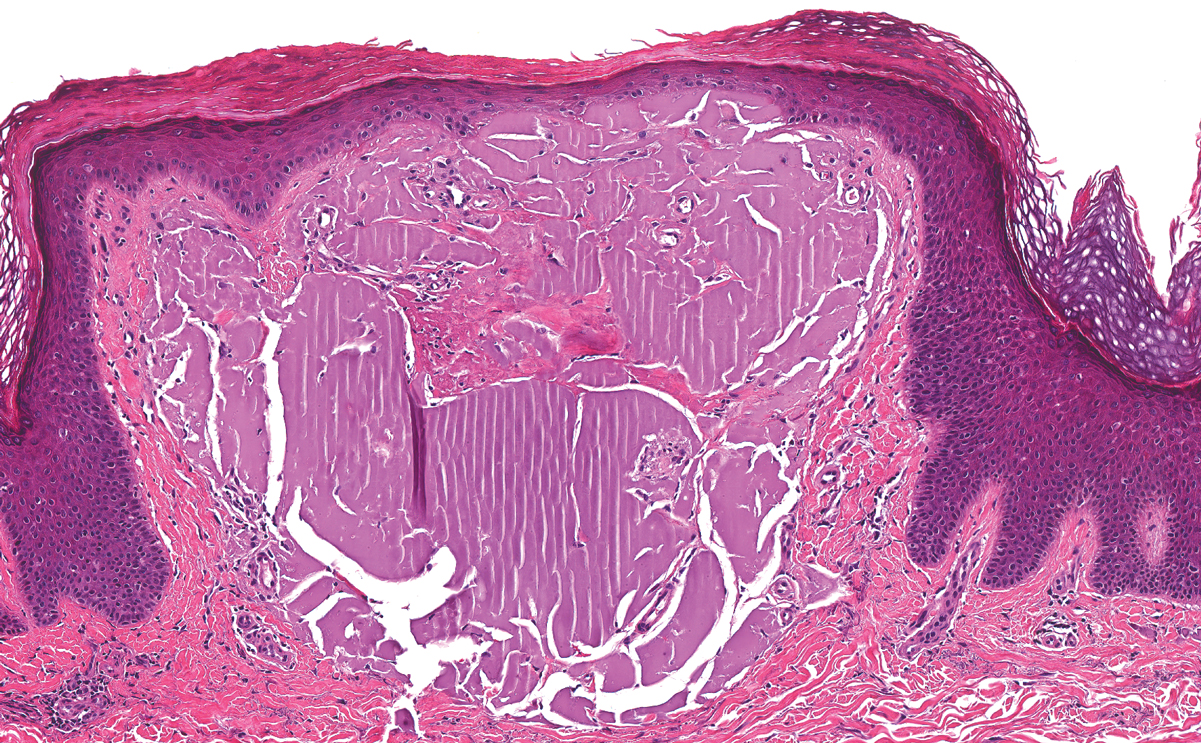

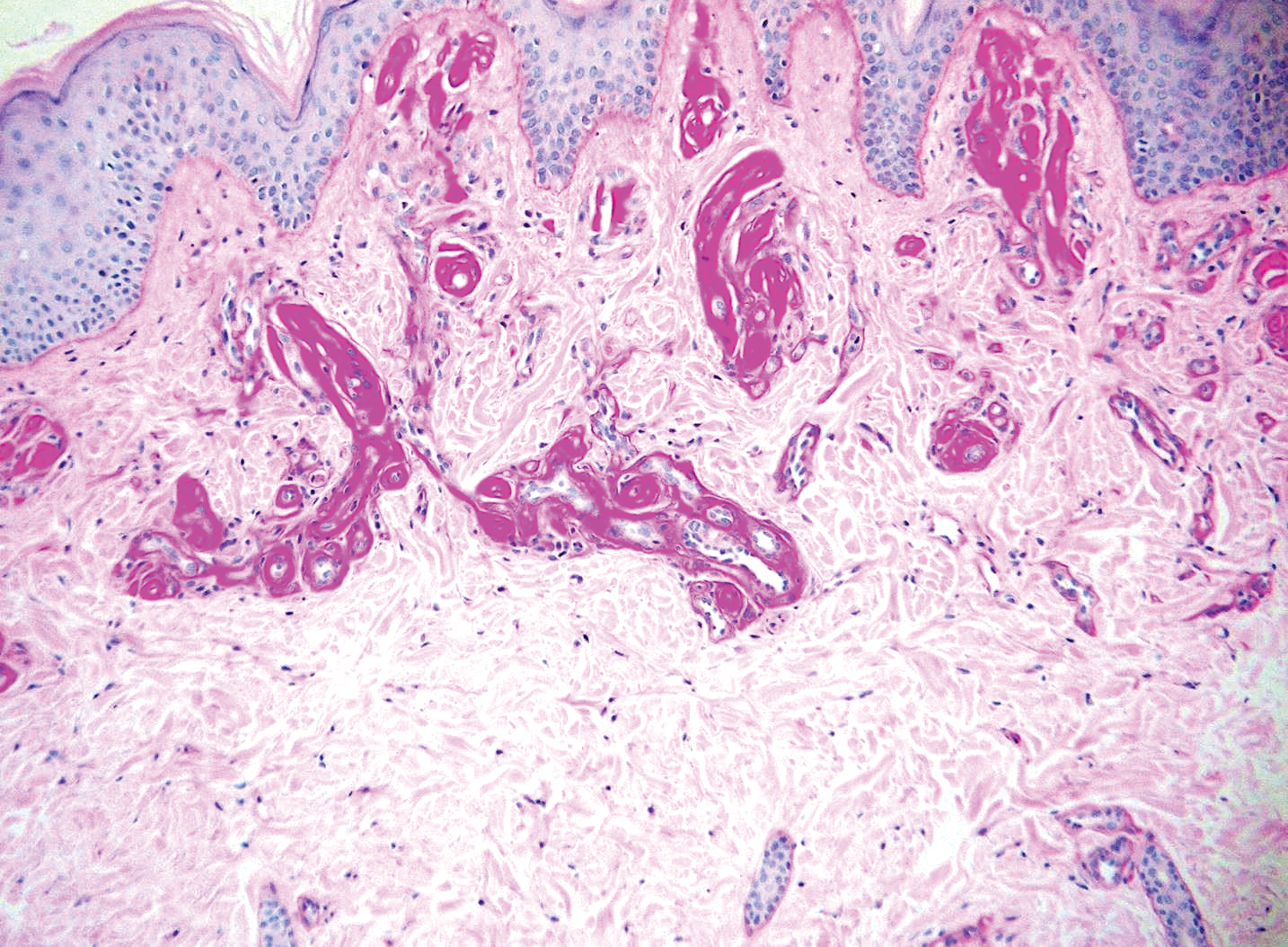

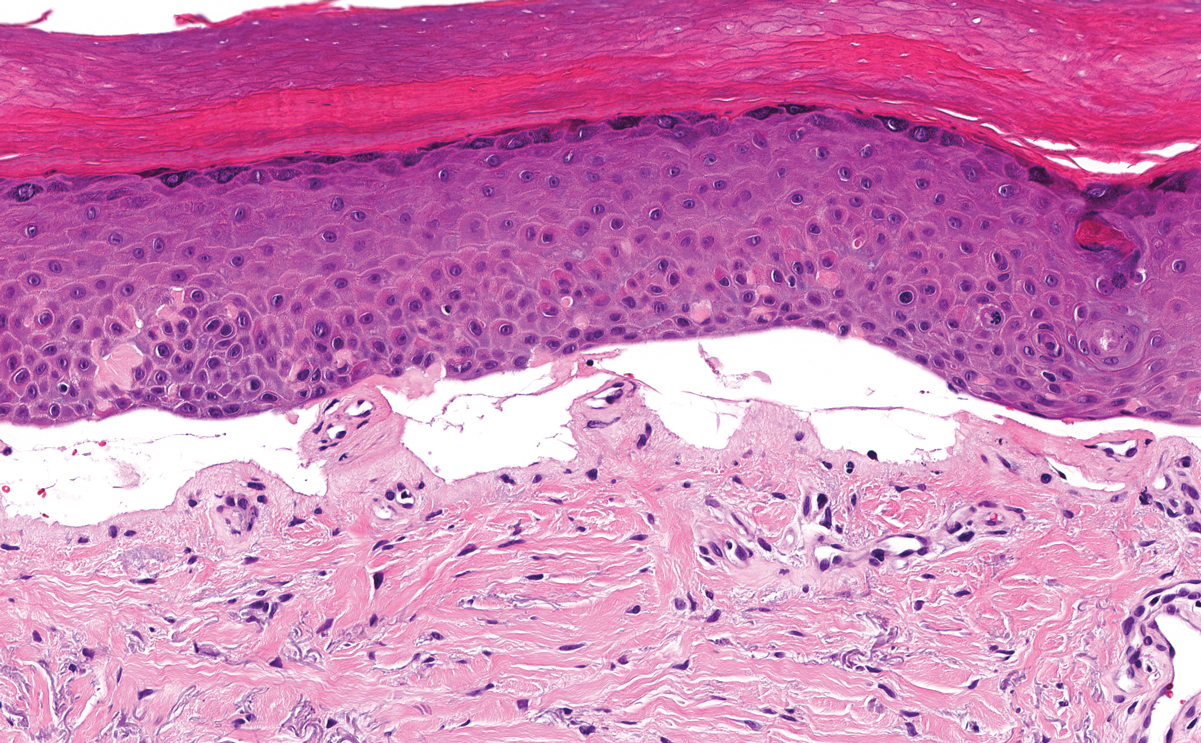

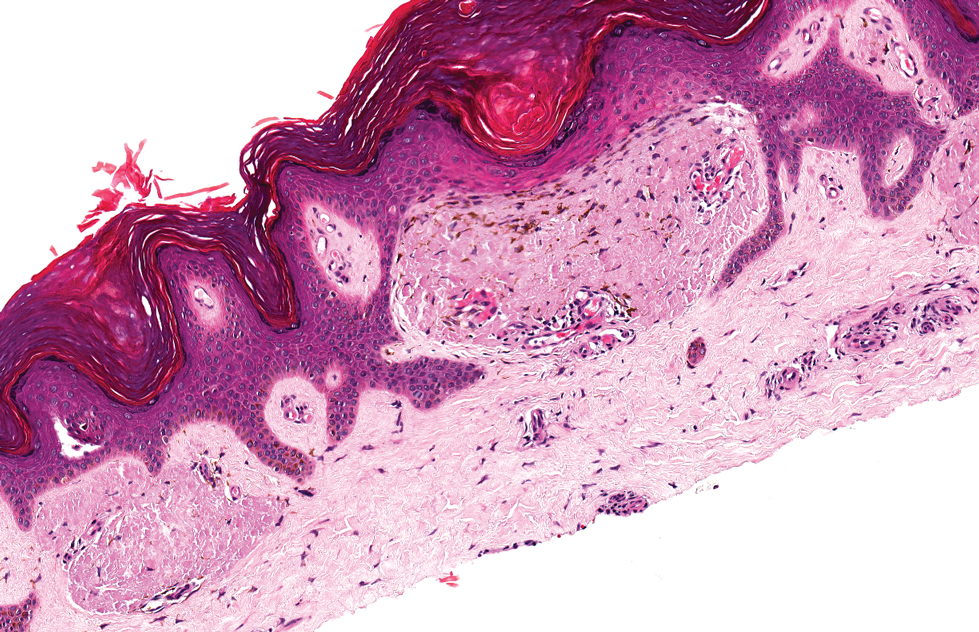

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

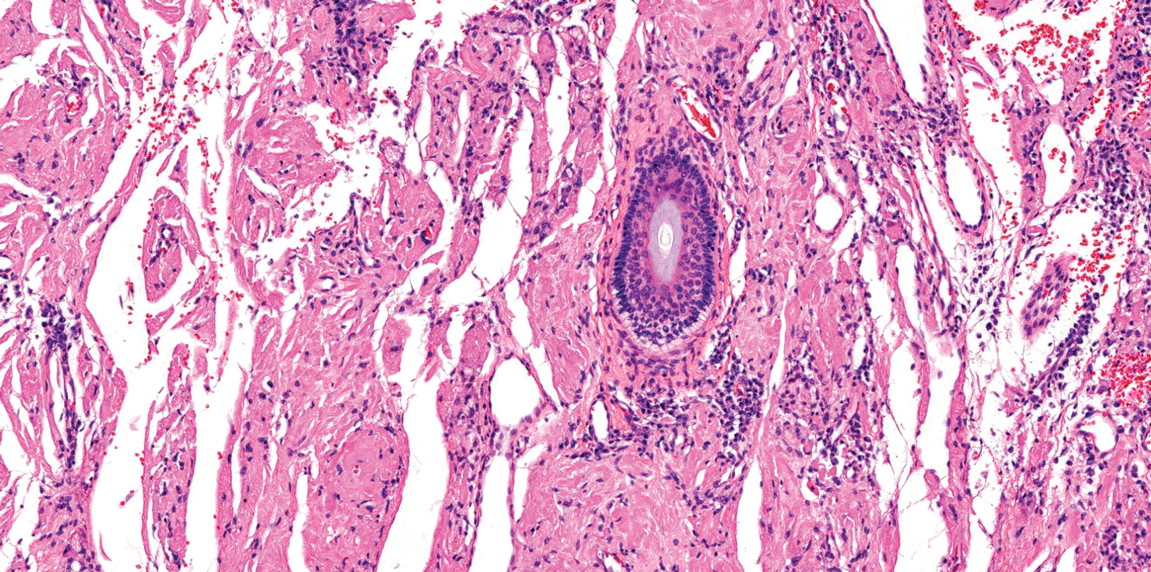

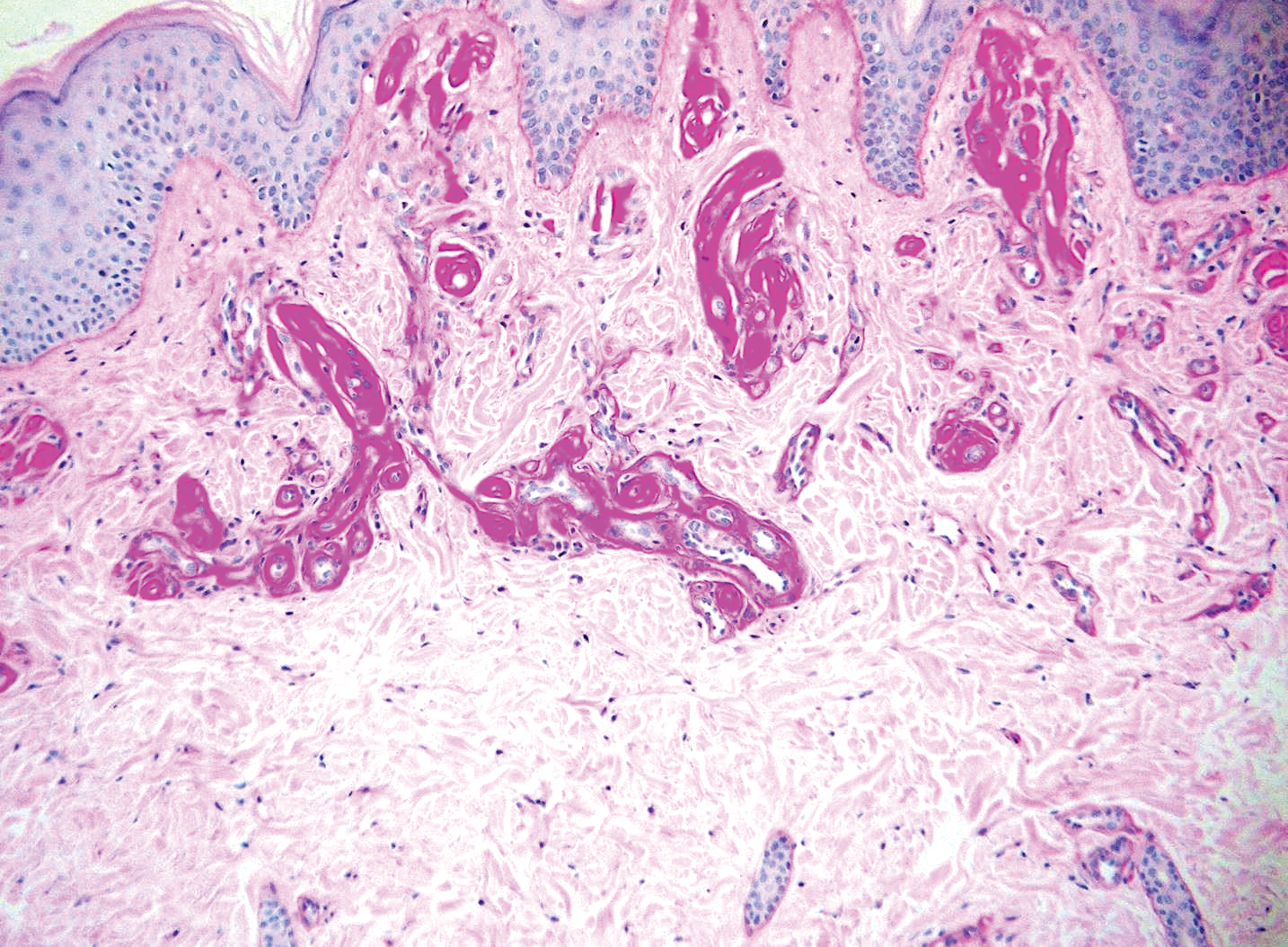

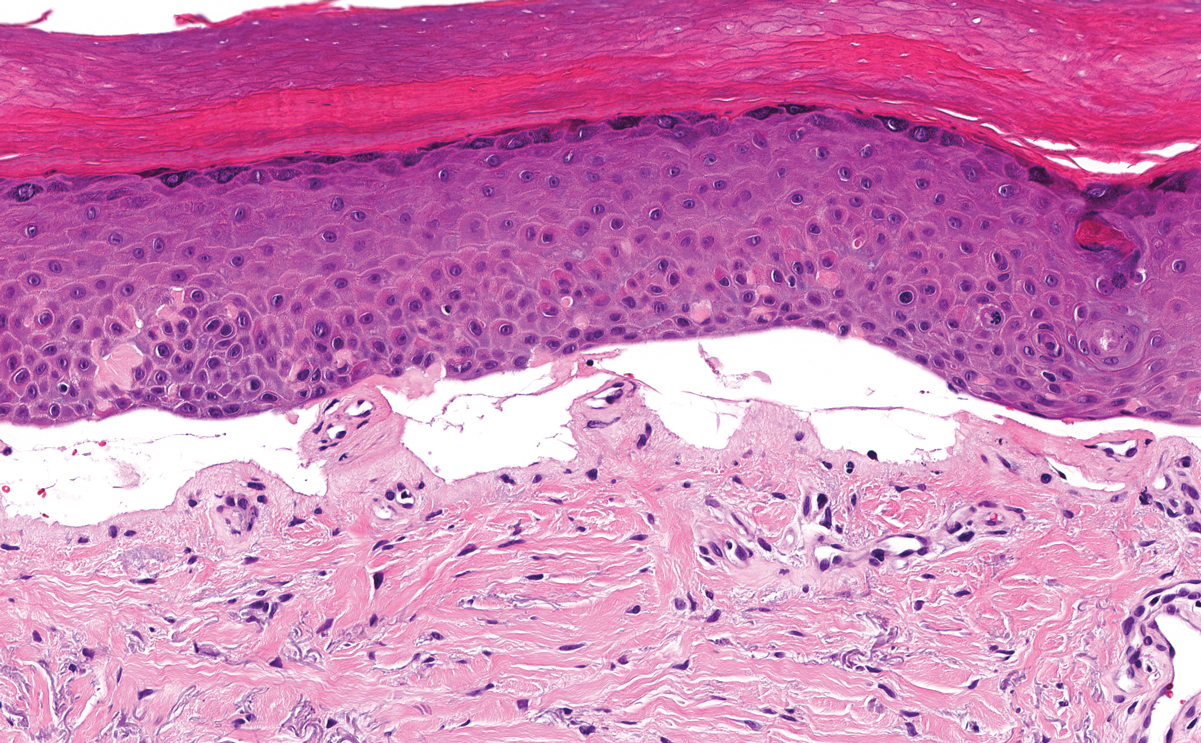

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

The Diagnosis: Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is an autosomal-recessive photodermatosis that results from loss of activity of ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway.1 Erythropoietic protoporphyria normally involves sun-exposed areas of the body. Skin that is exposed to sunlight develops intense burning and stinging pain followed by erythema, edema, crusting, and petechiae that develops into waxy scarring over time. In contrast to other porphyrias, blistering generally is not seen.2 Accurate diagnosis often can be delayed by a decade or more following symptom onset due to the prominence of subjective pain as the presenting sign.

The histologic appearance of EPP differs depending on the chronicity of lesions. Biopsies of acute lesions show vacuolization of epidermal cells with intercellular edema, vacuolization and cytolysis of endothelial cells in superficial blood vessels, and focal red blood cell extravasation.3,4 A largely neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate can be present.5 Hyaline cuffing develops over time in and around vessels in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis with notable sparing of adnexal structures. The perivascular deposits are strongly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence shows mainly IgG and some IgM, fibrinogen, and C3 outlining characteristic donut-shaped blood vessels in the papillary dermis.6 The prominent thickness of the perivascular hyaline material depositions and the absence of subepidermal blistering can help differentiate EPP from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) and pseudoporphyria.6,7 When the deposition is extensive and involves the surrounding dermis, EPP can mimic colloid milium. Additional histologic differential diagnoses of EPP include other dermal depositional diseases such as lipoid proteinosis and amyloidosis.

Lipoid proteinosis is an autosomal-recessive multisystem genodermatosis caused by mutations in extracellular matrix gene 1, ECM1. The first clinical sign can be a hoarse cry in infancy due to infiltration of vocal cords.3 Development of papulonodular lesions along the eyelids can result in a string-of-beads appearance called moniliform blepharosis, which is pathognomonic for lipoid proteinosis.6 With chronicity, the involved skin can become yellow, waxy, and thickened, particularly in the flexures or areas of trauma. Histologically, the dermis in lipoid proteinosis becomes diffusely thickened due to deposition of PAS-positive eosinophilic hyaline material that stains weakly with Congo red and thioflavin T.6 Early lesions demonstrate pale pink, hyalinelike thickening of the papillary dermal capillaries. Chronic lesions reveal an acanthotic epidermis, occasional papillomatosis with overlying hyperkeratosis, and a thickened dermis where diffuse thick bundles of pink hyaline deposits are oriented perpendicularly to the dermoepidermal junction.1,6 Lipoid proteinosis can be differentiated from EPP by the involvement of adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles (Figure 2), as opposed to EPP where adnexal structures are spared.1 Additionally, depositions in lipoid proteinosis are centered around both superficial and deep vessels with an onion skin-like pattern, while EPP involves mainly superficial vessels with more mild and focal hyalinization.

Juvenile colloid milium (JCM) is a rare condition that presents before puberty with discrete, yellow-brown, translucent papules predominantly located on the cheeks and nose and around the mouth. A gelatinous material can be expressed after puncturing a lesion.6 Gingival deposits and ligneous conjunctivitis also can be present. On histopathology, JCM shows degeneration of epidermal keratinocytes that form colloid bodies within the superficial dermis following apoptosis.6 Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows amorphous, fissured, pale pink deposits completely filling and expanding the superficial to mid dermis with clefting and no inflammation (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped fibroblasts may be seen within the lines of colloid fissuring and dispersed throughout the deposits.1 Histologically, JCM can be differentiated from EPP because deposits in EPP are distributed around and within superficial blood vessel walls, causing prominent vascular thickening not seen in JCM.6 The adult variant of colloid milium also can be distinguished from EPP by the presence of solar elastosis, which is absent in EPP due to a history of sun avoidance.3,7

Lichen amyloidosis presents with highly pruritic, red-brown, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly are found on the anterior lower legs and extensor forearms.1 The calves, ankles, dorsal aspects of the feet, thighs, and trunk also may be affected. Excoriations, lichenification, and nodular prurigo-like lesions due to chronic scratching can be present.6 Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by large, pink, amorphous deposits in the papillary dermis with epidermal acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis (Figure 4).6 Perivascular deposits are not a feature of primary cutaneous localized amyloid lesions.6 The diagnosis can be confirmed with Congo red staining under polarized light, which classically demonstrates apple green birefringence.1 For cases of amyloid that are not detected by Congo red or are not clear-cut, direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry can be used as adjuncts for diagnosis. Amyloid deposits fluoresce positively for immunoglobulins or complements, particularly IgM and C3,8 and immunohistochemistry confirms the presence of keratin epitopes in deposits.9

Porphyria cutanea tarda can appear histologically similar to EPP. Caterpillar bodies, or linearly arranged eosinophilic PAS-positive globules in the epidermis overlying subepidermal bullae, are a diagnostic histopathologic finding in both PCT and EPP but are seen in less than half of both cases.7,10 Compared to EPP, the perivascular deposits in PCT typically are less pronounced and limited to the vessel wall with smaller hyaline cuffs (Figure 5).7 Additionally, solar elastosis can be seen in PCT lesions but not in EPP, as patients with PCT tend to be older and have increased cumulative sun damage.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171; quiz 172-144.

- Lim HW. Pathogenesis of photosensitivity in the cutaneous porphyrias. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:xvi-xvii.

- In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Horner ME, Alikhan A, Tintle S, et al. Cutaneous porphyrias part I: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and histopathology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1464-1480.

- Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2016.

- MacDonald DM, Black MM, Ramnarain N. Immunofluorescence studies in primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1977;96:635-641.

- Ortiz-Romero PL, Ballestin-Carcavilla C, Lopez-Estebaranz JL, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on lichen amyloidosis and macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1559-1560.

- Raso DS, Greene WB, Maize JC, et al. Caterpillar bodies of porphyria cutanea tarda ultrastructurally represent a unique arrangement of colloid and basement membrane bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:24-29.

A 9-year-old girl presented with unexplained burning pain on the face, hands, and feet of 3 years' duration. Physical examination showed depressed shiny scars and crusted erosions on the dorsal aspect of the nose, arms, hands, and fingers. A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right hand.

Pooled COVID-19 testing feasible, greatly reduces supply use

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 and the myth of the super doctor

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

AGA releases iron-deficiency anemia guideline

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has released a clinical practice guideline for gastrointestinal evaluation of iron-deficiency anemia.

The seven recommendations aim to improve quality of care and reduce practice variability, according to lead author Cynthia W. Ko, MD, of the University of Washington , Seattle, and four copanelists.

First, the panel recommended that iron deficiency be defined by a serum ferritin level less than 45 ng/mL, instead of 15 ng/mL. Data from 55 studies showed that the higher cutoff value had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 92%, compared with respective values of 59% and 99% for the lower threshold.

“Optimizing the threshold ferritin level with high sensitivity will detect the great majority of patients who are truly iron deficient, minimize delays in diagnostic workup, and minimize the number of patients in whom serious underlying etiologies such as gastrointestinal malignancy might be missed,” the panelists wrote. The guideline was published in Gastroenterology.

For asymptomatic postmenopausal women and men with iron-deficiency anemia, the panel recommended bidirectional endoscopy instead of no endoscopy. A similar recommendation was given for premenopausal women, calling for bidirectional endoscopy instead of iron-replacement therapy alone.

Dr. Ko and colleagues noted that these recommendations differ from those issued by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG).

For postmenopausal women and men, the BSG suggests that symptoms and local availability of endoscopy should inform diagnostic workup, with either colonoscopy or CT colonography used for assessment. The BSG recommends against bidirectional endoscopy in premenopausal women, unless they are older than 50 years, have a family history of colorectal cancer, or show symptoms of gastrointestinal disease.

“In contrast, the AGA recommends bidirectional endoscopy as the mainstay for gastrointestinal evaluation, particularly in men and in postmenopausal women where no other unequivocal source of iron deficiency has been identified,” the panelists wrote.

When bidirectional endoscopy does not reveal an etiology, the panelists recommended noninvasive testing for Helicobacter pylori.

“An association between H. pylori infection and iron deficiency has been demonstrated in observational studies,” noted Dr. Ko and colleagues.