User login

FDA authorizes new saliva COVID-19 test

The FDA authorized a new type of saliva-based coronavirus test on August 15 that could cut down on the cost of testing and the time it takes to process results.

The emergency use authorization is for SalivaDirect, a diagnostic test created by the Yale School of Public Health. The test doesn’t require a special type of swab or collection tube — saliva can be collected in any sterile container, according to the FDA announcement.

The new test is “yet another testing innovation game changer that will reduce the demand for scarce testing resources,” Admiral Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary for health and the COVID-19 testing coordinator, said in the statement.

The test also doesn’t require a special type of extractor, which is helpful because the extraction kits used to process other tests have faced shortages during the pandemic. The test can be used with different types of reagents and instruments already found in labs.

“Providing this type of flexibility for processing saliva samples to test for COVID-19 infection is groundbreaking in terms of efficiency and avoiding shortages of crucial test components like reagents,” Stephen Hahn, MD, the FDA commissioner, also said in the statement.

Yale will provide the instructions to labs as an “open source” protocol. The test doesn’t require any proprietary equipment or testing components, so labs across the country can assemble and use it based on the FDA guidelines. The testing method is available immediately and could be scaled up quickly in the next few weeks, according to a statement from Yale.

“This is a huge step forward to make testing more accessible,” Chantal Vogels, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale who led the lab development and test validation efforts, said in the statement.

The Yale team is further testing whether the saliva method can be used to find coronavirus cases among people who don’t have any symptoms and has been working with players and staff from the NBA. So far, the results have been accurate and similar to the nasal swabs for COVID-19, according to a preprint study published on medRxiv.

The research team wanted to get rid of the expensive collection tubes that other companies use to preserve the virus during processing, according to the Yale statement. They found that the virus is stable in saliva for long periods of time at warm temperatures and that special tubes aren’t necessary.

The FDA has authorized other saliva-based tests, according to ABC News, but SalivaDirect is the first that doesn’t require the extraction process used to test viral genetic material. Instead, the Yale process breaks down the saliva with an enzyme and applied heat. This type of testing could cost about $10, the Yale researchers said, and people can collect the saliva themselves under supervision.

“This, I hope, is a turning point,” Anne Wyllie, PhD, one of the lead researchers at Yale, told the news station.* “Expand testing capacity, inspire creativity and we can take competition to those labs charging a lot and bring prices down.”

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Correction, 8/25/20: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Wylie's academic degree.

The FDA authorized a new type of saliva-based coronavirus test on August 15 that could cut down on the cost of testing and the time it takes to process results.

The emergency use authorization is for SalivaDirect, a diagnostic test created by the Yale School of Public Health. The test doesn’t require a special type of swab or collection tube — saliva can be collected in any sterile container, according to the FDA announcement.

The new test is “yet another testing innovation game changer that will reduce the demand for scarce testing resources,” Admiral Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary for health and the COVID-19 testing coordinator, said in the statement.

The test also doesn’t require a special type of extractor, which is helpful because the extraction kits used to process other tests have faced shortages during the pandemic. The test can be used with different types of reagents and instruments already found in labs.

“Providing this type of flexibility for processing saliva samples to test for COVID-19 infection is groundbreaking in terms of efficiency and avoiding shortages of crucial test components like reagents,” Stephen Hahn, MD, the FDA commissioner, also said in the statement.

Yale will provide the instructions to labs as an “open source” protocol. The test doesn’t require any proprietary equipment or testing components, so labs across the country can assemble and use it based on the FDA guidelines. The testing method is available immediately and could be scaled up quickly in the next few weeks, according to a statement from Yale.

“This is a huge step forward to make testing more accessible,” Chantal Vogels, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale who led the lab development and test validation efforts, said in the statement.

The Yale team is further testing whether the saliva method can be used to find coronavirus cases among people who don’t have any symptoms and has been working with players and staff from the NBA. So far, the results have been accurate and similar to the nasal swabs for COVID-19, according to a preprint study published on medRxiv.

The research team wanted to get rid of the expensive collection tubes that other companies use to preserve the virus during processing, according to the Yale statement. They found that the virus is stable in saliva for long periods of time at warm temperatures and that special tubes aren’t necessary.

The FDA has authorized other saliva-based tests, according to ABC News, but SalivaDirect is the first that doesn’t require the extraction process used to test viral genetic material. Instead, the Yale process breaks down the saliva with an enzyme and applied heat. This type of testing could cost about $10, the Yale researchers said, and people can collect the saliva themselves under supervision.

“This, I hope, is a turning point,” Anne Wyllie, PhD, one of the lead researchers at Yale, told the news station.* “Expand testing capacity, inspire creativity and we can take competition to those labs charging a lot and bring prices down.”

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Correction, 8/25/20: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Wylie's academic degree.

The FDA authorized a new type of saliva-based coronavirus test on August 15 that could cut down on the cost of testing and the time it takes to process results.

The emergency use authorization is for SalivaDirect, a diagnostic test created by the Yale School of Public Health. The test doesn’t require a special type of swab or collection tube — saliva can be collected in any sterile container, according to the FDA announcement.

The new test is “yet another testing innovation game changer that will reduce the demand for scarce testing resources,” Admiral Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary for health and the COVID-19 testing coordinator, said in the statement.

The test also doesn’t require a special type of extractor, which is helpful because the extraction kits used to process other tests have faced shortages during the pandemic. The test can be used with different types of reagents and instruments already found in labs.

“Providing this type of flexibility for processing saliva samples to test for COVID-19 infection is groundbreaking in terms of efficiency and avoiding shortages of crucial test components like reagents,” Stephen Hahn, MD, the FDA commissioner, also said in the statement.

Yale will provide the instructions to labs as an “open source” protocol. The test doesn’t require any proprietary equipment or testing components, so labs across the country can assemble and use it based on the FDA guidelines. The testing method is available immediately and could be scaled up quickly in the next few weeks, according to a statement from Yale.

“This is a huge step forward to make testing more accessible,” Chantal Vogels, a postdoctoral fellow at Yale who led the lab development and test validation efforts, said in the statement.

The Yale team is further testing whether the saliva method can be used to find coronavirus cases among people who don’t have any symptoms and has been working with players and staff from the NBA. So far, the results have been accurate and similar to the nasal swabs for COVID-19, according to a preprint study published on medRxiv.

The research team wanted to get rid of the expensive collection tubes that other companies use to preserve the virus during processing, according to the Yale statement. They found that the virus is stable in saliva for long periods of time at warm temperatures and that special tubes aren’t necessary.

The FDA has authorized other saliva-based tests, according to ABC News, but SalivaDirect is the first that doesn’t require the extraction process used to test viral genetic material. Instead, the Yale process breaks down the saliva with an enzyme and applied heat. This type of testing could cost about $10, the Yale researchers said, and people can collect the saliva themselves under supervision.

“This, I hope, is a turning point,” Anne Wyllie, PhD, one of the lead researchers at Yale, told the news station.* “Expand testing capacity, inspire creativity and we can take competition to those labs charging a lot and bring prices down.”

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Correction, 8/25/20: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Wylie's academic degree.

A pandemic playbook for residency programs in the COVID-19 era: Lessons learned from ObGyn programs at the epicenter

The 2020 pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has presented significant challenges to the health care workforce.1,2 As New York City and its environs became the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States, we continued to care for our patients while simultaneously maintaining the education and well-being of our residents.3 Keeping this balance significantly strained resources and presented new challenges for education and service in residency education. What first emerged as an acute emergency has become a chronic disruption in the clinical learning environment. Programs are working to respond to the critical patient needs while ensuring continued progress toward training goals.

Since pregnancy is one condition for which healthy patients continued to require both outpatient visits and inpatient hospitalization, volume was not anticipated to be significantly decreased on our units. Thus, our ObGyn residency programs sought to expeditiously restructure our workforce and educational methods to address the demands of the pandemic. We were aided in our efforts by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Extraordinary Circumstances policy. Our institutions were deemed to be functioning at Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status, a state in which “the increase in volume and/or severity of illness creates an extraordinary circumstance where routine care, education, and delivery must be reconfigured to focus only on patient care.”4

As of May 18, 2020, 26% of residency and fellowship programs in the United States were under Stage 3 COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency Status.5 Accordingly, our patient care delivery and educational processes were reconfigured within the context of Stage 3 Status, governed by the overriding principles of ensuring appropriate resources and training, adhering to work hour limits, providing adequate supervision, and credentialing fellows to function in our core specialty.

As ObGyn education leaders from 5 academic medical centers within the COVID-19 epicenter, we present a summary of best practices, based on our experiences, for each of the 4 categories of Stage 3 Status outlined by the ACGME. In an era of globalization, we must learn from pandemics, a call made after the Ebola outbreak in 2015.6 We recognize that this type of disruption could happen again with a possible second wave of COVID-19 or another emerging disease.7 Thus, we emphasize “lessons learned” that are applicable to a wide range of residency training programs facing various clinical crises.

Ensuring adequate resources and training

Within the context of Stage 3 Status, residency programs have the flexibility to increase residents’ availability in the clinical care setting. However, programs must ensure the safety of both patients and residents.

Continue to: Measures to decrease risk of infection...

Measures to decrease risk of infection

One critical resource needed to protect patients and residents is personal protective equipment (PPE). Online instruction and in-person training were used to educate residents and staff on appropriate techniques for donning, doffing, and conserving PPE. Surgical teams were limited to 1 surgeon and 1 resident in each case. In an effort to limit direct contact with COVID-19 infected patients, the number of health care providers rounding on inpatients was restricted, and phone or video conversations were used for communication.

The workforce was modified to decrease exposure to infection and maintain a reserve of healthy residents who were working from home—anticipating that some residents would become ill and this reserve would be called for duty. Similar to other specialties, our programs organized the workforce by arranging residents into teams in which residents worked a number of shifts in a row.8-12 Regular block schedules were disrupted and non-core rotations were deferred.

As surgeries were canceled and outpatient visits curtailed, many rotations required less resident coverage. Residents were reassigned from rotations where clinical work was suspended to accommodate increased staffing needs in other areas, while accounting for residents who were ill or on leave for postexposure quarantine. Typically, residents worked 12-hour shifts for 3 to 6 days followed by several days off or days working remotely. This team-based strategy decreased the number of residents exposed to COVID-19 at one time, provided time for recuperation, encouraged camaraderie, and enabled residents working remotely to coordinate care and participate in telehealth without direct patient contact.

To minimize high-risk exposure of pregnant residents or residents with underlying health conditions, these residents also worked remotely. Similar to other specialties, it was important to determine essential resident duties and enlist assistance from other clinicians, such as fellows, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and midwives.

To protect residents and patients, maximizing testing of patients for COVID-19 was an important strategy. Based on early experience at 1 center with patients who were initially asymptomatic but later developed symptoms and tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), universal testing was implemented and endorsed by the New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force.13 Notably, 87.9% of patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of admission had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation. Because the asymptomatic carrier rate appears to be high in obstetric patients, testing of patients is paramount.3,14 Finally, suspending visitation (except for 1 support person) also was instrumental in decreasing the risk of infection to residents.13

Resources for residents with COVID-19

This pandemic placed residency program directors in an unusual situation as frontline caregivers for their own residents. It was imperative to track residents with physical symptoms, conduct testing when possible, and follow the course of residents with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. As serious illness and death have been reported among otherwise healthy young people, we ensured that our homebound residents were frequently monitored.15 At several of our centers, residents with COVID-19 from any program who chose to separate from their families were provided with alternative housing accommodations. In addition, some of our graduate medical education offices identified specific physicians to care for residents with COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization.

Continue to: Deployment to other specialties...

Deployment to other specialties

Several hospitals in the United States redeployed residents because of staffing shortages in high-impact settings.12 It was important for ObGyns to emphasize that the labor and delivery unit functions as the emergency ward for pregnant women, and that ObGyn residents possess skills specific to the care of these patients.

For our departments, we highlighted that external redeployment could adversely affect our workforce restructuring and, ultimately, patient care. We focused efforts on internal deployment or reassignment as much as possible. Some faculty and fellows in nonobstetric subspecialty areas were redirected to provide care on our inpatient obstetric services.

Educating residents

To maintain educational efforts with social distancing, we used videoconferencing to preserve the protected didactic education time that existed for our residents before the pandemic. This regularly scheduled, nonclinical time also was utilized to instruct residents on the rapidly changing clinical guidelines and to disseminate information about new institutional policies and procedures, ensuring that residents were adequately prepared for their new clinical work.

Work hour requirements

The ACGME requires that work hour limitations remain unchanged during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status. As the pandemic presented new challenges and stressors for residents inside and outside the workplace, ensuring adequate time off to rest and recover was critical for maintaining the resident workforce’s health and wellness.

Thus, our workforce restructuring plans accounted for work hour limitations. As detailed above, the restructuring was accomplished by cohorting residents into small teams that remained unchanged for several weeks. Most shifts were limited to 12 hours, residents continued to be assigned at least 1 day off each week, and daily schedules were structured to ensure at least 10 hours off between shifts. Time spent working remotely was included in work hour calculations.

In addition, residents on “jeopardy” who were available for those who needed to be removed from direct patient care were given at least 1 day off per week in which they could not be pulled for clinical duty. Finally, prolonged inpatient assignments were limited; after these assignments, residents were given increased time for rest and recuperation.

Ensuring adequate supervision

The expectation during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status is that residents, with adequate supervision, provide care that is appropriate for their level of training. To adequately and safely supervise residents, faculty needed training to remain well informed about the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. This was accomplished through frequent communication and consultation with colleagues in infectious disease, occupational health, and guidance from national organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and information from our state health departments.

Faculty members were trained in safe donning and doffing of PPE and infection control strategies to ensure they could safely oversee and train residents in these practices. Faculty schedules were significantly altered to ensure an adequate workforce and adequate resident supervision. Faculty efforts were focused on areas of critical need—in our case inpatient obstetrics—with a smaller workforce assigned to outpatient services and inpatient gynecology and gynecologic oncology. Many ObGyn subspecialist faculty were redeployed to general ObGyn inpatient units, thus permitting appropriate resident supervision at all times. In the outpatient setting, faculty adjusted to the changing demands and learned to conduct and supervise telehealth visits.

Finally, for those whose residents were deployed to other services (for example, internal medicine, emergency medicine, or critical care), supervision became paramount. We checked in with our deployed residents daily to be sure that their supervision on those services was adequate. Considering the extreme complexity, rapidly changing understanding of the disease, and often tragic patient outcomes, it was essential to ensure appropriate support and supervision on “off service” deployment.

Continue to: Fellows functioning in core specialty...

Fellows functioning in core specialty

Anticipating the increased need for clinicians on the obstetric services, fellows in subspecialty areas were granted emergency privileges to act as attending faculty in the core specialty, supervising residents and providing patient care. On the other hand, some of those fellows, primarily in gynecologic oncology, were externally redeployed out of core specialty to internal medicine and critical care units. Careful consideration of the fellows’ needs for supervision and support in these roles was essential, and similar support measures that were put in place for our residents were offered to fellows.

In conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented diverse and complex challenges to the entire health care workforce. Because this crisis is widespread and likely will be lengthy, a sustained and organized response is required.16 We have highlighted unique challenges specific to residency programs and presented collective best practices from our experiences in ObGyn navigating these obstacles, which are applicable to many other programs.

The flexibility and relief afforded by the ACGME Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status designation allowed us to meet the needs of the surge of patients that required care while we maintained our educational framework and tenets of providing adequate resources and training, working within the confines of safe work hours, ensuring proper supervision, and granting attending privileges to fellows in their core specialty. ●

- Panahi L, Amiri M, Pouy S. Risks of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy; a narrative review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8e34.

- Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:415-426.

- Sutton D, Fuchs K, D'Alton M, et al. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163-2164.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Three stages of GME during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.acgme.org/COVID-19/Three-Stages-of-GME-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Emergency category maps/5-18-20: percentage of residents in each state/territory under pandemic emergency status. Percentage of residency and fellowship programs under ACGME COVID-19 pandemic emergency status (stage 3). https://dl.acgme.org/learn/course/sponsoring-institution-idea-exchange/emergency-category-maps/5-18-20-percentage-of-residents-in-each-state-territory-under-pandemic-emergency-status. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Gates B. The next epidemic--lessons from Ebola. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1381-1384.

- Pepe D, Martinello RA, Juthani-Mehta M. Involving physicians-in-training in the care of patients during epidemics. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:632-634.

- Crosby DL, Sharma A. Insights on otolaryngology residency training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:38-41.

- Kim CS, Lynch JB, Seth C, et al. One academic health system's early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95:1146-1148.

- Kogan M, Klein SE, Hannon CP, et al. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020; 28:e456-e464.

- Vargo E, Ali M, Henry F, et al. Cleveland Clinic Akron general urology residency program's COVID-19 experience. Urology. 2020;140:1-3.

- Zarzaur BL, Stahl CC, Greenberg JA, et al. Blueprint for restructuring a department of surgery in concert with the health care system during a pandemic: the University of Wisconsin experience. JAMA Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1386.

- New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force. Recommendations to the governor to promote increased choice and access to safe maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/governor.ny.gov/files/atoms/files/042920_CMTF_Recommendations.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Campbell KH, Tornatore JM, Lawrence KE, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among patients admitted for childbirth in southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520-2522.

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)--United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343-346.

- Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860-868.

The 2020 pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has presented significant challenges to the health care workforce.1,2 As New York City and its environs became the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States, we continued to care for our patients while simultaneously maintaining the education and well-being of our residents.3 Keeping this balance significantly strained resources and presented new challenges for education and service in residency education. What first emerged as an acute emergency has become a chronic disruption in the clinical learning environment. Programs are working to respond to the critical patient needs while ensuring continued progress toward training goals.

Since pregnancy is one condition for which healthy patients continued to require both outpatient visits and inpatient hospitalization, volume was not anticipated to be significantly decreased on our units. Thus, our ObGyn residency programs sought to expeditiously restructure our workforce and educational methods to address the demands of the pandemic. We were aided in our efforts by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Extraordinary Circumstances policy. Our institutions were deemed to be functioning at Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status, a state in which “the increase in volume and/or severity of illness creates an extraordinary circumstance where routine care, education, and delivery must be reconfigured to focus only on patient care.”4

As of May 18, 2020, 26% of residency and fellowship programs in the United States were under Stage 3 COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency Status.5 Accordingly, our patient care delivery and educational processes were reconfigured within the context of Stage 3 Status, governed by the overriding principles of ensuring appropriate resources and training, adhering to work hour limits, providing adequate supervision, and credentialing fellows to function in our core specialty.

As ObGyn education leaders from 5 academic medical centers within the COVID-19 epicenter, we present a summary of best practices, based on our experiences, for each of the 4 categories of Stage 3 Status outlined by the ACGME. In an era of globalization, we must learn from pandemics, a call made after the Ebola outbreak in 2015.6 We recognize that this type of disruption could happen again with a possible second wave of COVID-19 or another emerging disease.7 Thus, we emphasize “lessons learned” that are applicable to a wide range of residency training programs facing various clinical crises.

Ensuring adequate resources and training

Within the context of Stage 3 Status, residency programs have the flexibility to increase residents’ availability in the clinical care setting. However, programs must ensure the safety of both patients and residents.

Continue to: Measures to decrease risk of infection...

Measures to decrease risk of infection

One critical resource needed to protect patients and residents is personal protective equipment (PPE). Online instruction and in-person training were used to educate residents and staff on appropriate techniques for donning, doffing, and conserving PPE. Surgical teams were limited to 1 surgeon and 1 resident in each case. In an effort to limit direct contact with COVID-19 infected patients, the number of health care providers rounding on inpatients was restricted, and phone or video conversations were used for communication.

The workforce was modified to decrease exposure to infection and maintain a reserve of healthy residents who were working from home—anticipating that some residents would become ill and this reserve would be called for duty. Similar to other specialties, our programs organized the workforce by arranging residents into teams in which residents worked a number of shifts in a row.8-12 Regular block schedules were disrupted and non-core rotations were deferred.

As surgeries were canceled and outpatient visits curtailed, many rotations required less resident coverage. Residents were reassigned from rotations where clinical work was suspended to accommodate increased staffing needs in other areas, while accounting for residents who were ill or on leave for postexposure quarantine. Typically, residents worked 12-hour shifts for 3 to 6 days followed by several days off or days working remotely. This team-based strategy decreased the number of residents exposed to COVID-19 at one time, provided time for recuperation, encouraged camaraderie, and enabled residents working remotely to coordinate care and participate in telehealth without direct patient contact.

To minimize high-risk exposure of pregnant residents or residents with underlying health conditions, these residents also worked remotely. Similar to other specialties, it was important to determine essential resident duties and enlist assistance from other clinicians, such as fellows, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and midwives.

To protect residents and patients, maximizing testing of patients for COVID-19 was an important strategy. Based on early experience at 1 center with patients who were initially asymptomatic but later developed symptoms and tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), universal testing was implemented and endorsed by the New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force.13 Notably, 87.9% of patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of admission had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation. Because the asymptomatic carrier rate appears to be high in obstetric patients, testing of patients is paramount.3,14 Finally, suspending visitation (except for 1 support person) also was instrumental in decreasing the risk of infection to residents.13

Resources for residents with COVID-19

This pandemic placed residency program directors in an unusual situation as frontline caregivers for their own residents. It was imperative to track residents with physical symptoms, conduct testing when possible, and follow the course of residents with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. As serious illness and death have been reported among otherwise healthy young people, we ensured that our homebound residents were frequently monitored.15 At several of our centers, residents with COVID-19 from any program who chose to separate from their families were provided with alternative housing accommodations. In addition, some of our graduate medical education offices identified specific physicians to care for residents with COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization.

Continue to: Deployment to other specialties...

Deployment to other specialties

Several hospitals in the United States redeployed residents because of staffing shortages in high-impact settings.12 It was important for ObGyns to emphasize that the labor and delivery unit functions as the emergency ward for pregnant women, and that ObGyn residents possess skills specific to the care of these patients.

For our departments, we highlighted that external redeployment could adversely affect our workforce restructuring and, ultimately, patient care. We focused efforts on internal deployment or reassignment as much as possible. Some faculty and fellows in nonobstetric subspecialty areas were redirected to provide care on our inpatient obstetric services.

Educating residents

To maintain educational efforts with social distancing, we used videoconferencing to preserve the protected didactic education time that existed for our residents before the pandemic. This regularly scheduled, nonclinical time also was utilized to instruct residents on the rapidly changing clinical guidelines and to disseminate information about new institutional policies and procedures, ensuring that residents were adequately prepared for their new clinical work.

Work hour requirements

The ACGME requires that work hour limitations remain unchanged during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status. As the pandemic presented new challenges and stressors for residents inside and outside the workplace, ensuring adequate time off to rest and recover was critical for maintaining the resident workforce’s health and wellness.

Thus, our workforce restructuring plans accounted for work hour limitations. As detailed above, the restructuring was accomplished by cohorting residents into small teams that remained unchanged for several weeks. Most shifts were limited to 12 hours, residents continued to be assigned at least 1 day off each week, and daily schedules were structured to ensure at least 10 hours off between shifts. Time spent working remotely was included in work hour calculations.

In addition, residents on “jeopardy” who were available for those who needed to be removed from direct patient care were given at least 1 day off per week in which they could not be pulled for clinical duty. Finally, prolonged inpatient assignments were limited; after these assignments, residents were given increased time for rest and recuperation.

Ensuring adequate supervision

The expectation during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status is that residents, with adequate supervision, provide care that is appropriate for their level of training. To adequately and safely supervise residents, faculty needed training to remain well informed about the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. This was accomplished through frequent communication and consultation with colleagues in infectious disease, occupational health, and guidance from national organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and information from our state health departments.

Faculty members were trained in safe donning and doffing of PPE and infection control strategies to ensure they could safely oversee and train residents in these practices. Faculty schedules were significantly altered to ensure an adequate workforce and adequate resident supervision. Faculty efforts were focused on areas of critical need—in our case inpatient obstetrics—with a smaller workforce assigned to outpatient services and inpatient gynecology and gynecologic oncology. Many ObGyn subspecialist faculty were redeployed to general ObGyn inpatient units, thus permitting appropriate resident supervision at all times. In the outpatient setting, faculty adjusted to the changing demands and learned to conduct and supervise telehealth visits.

Finally, for those whose residents were deployed to other services (for example, internal medicine, emergency medicine, or critical care), supervision became paramount. We checked in with our deployed residents daily to be sure that their supervision on those services was adequate. Considering the extreme complexity, rapidly changing understanding of the disease, and often tragic patient outcomes, it was essential to ensure appropriate support and supervision on “off service” deployment.

Continue to: Fellows functioning in core specialty...

Fellows functioning in core specialty

Anticipating the increased need for clinicians on the obstetric services, fellows in subspecialty areas were granted emergency privileges to act as attending faculty in the core specialty, supervising residents and providing patient care. On the other hand, some of those fellows, primarily in gynecologic oncology, were externally redeployed out of core specialty to internal medicine and critical care units. Careful consideration of the fellows’ needs for supervision and support in these roles was essential, and similar support measures that were put in place for our residents were offered to fellows.

In conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented diverse and complex challenges to the entire health care workforce. Because this crisis is widespread and likely will be lengthy, a sustained and organized response is required.16 We have highlighted unique challenges specific to residency programs and presented collective best practices from our experiences in ObGyn navigating these obstacles, which are applicable to many other programs.

The flexibility and relief afforded by the ACGME Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status designation allowed us to meet the needs of the surge of patients that required care while we maintained our educational framework and tenets of providing adequate resources and training, working within the confines of safe work hours, ensuring proper supervision, and granting attending privileges to fellows in their core specialty. ●

The 2020 pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has presented significant challenges to the health care workforce.1,2 As New York City and its environs became the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States, we continued to care for our patients while simultaneously maintaining the education and well-being of our residents.3 Keeping this balance significantly strained resources and presented new challenges for education and service in residency education. What first emerged as an acute emergency has become a chronic disruption in the clinical learning environment. Programs are working to respond to the critical patient needs while ensuring continued progress toward training goals.

Since pregnancy is one condition for which healthy patients continued to require both outpatient visits and inpatient hospitalization, volume was not anticipated to be significantly decreased on our units. Thus, our ObGyn residency programs sought to expeditiously restructure our workforce and educational methods to address the demands of the pandemic. We were aided in our efforts by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Extraordinary Circumstances policy. Our institutions were deemed to be functioning at Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status, a state in which “the increase in volume and/or severity of illness creates an extraordinary circumstance where routine care, education, and delivery must be reconfigured to focus only on patient care.”4

As of May 18, 2020, 26% of residency and fellowship programs in the United States were under Stage 3 COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency Status.5 Accordingly, our patient care delivery and educational processes were reconfigured within the context of Stage 3 Status, governed by the overriding principles of ensuring appropriate resources and training, adhering to work hour limits, providing adequate supervision, and credentialing fellows to function in our core specialty.

As ObGyn education leaders from 5 academic medical centers within the COVID-19 epicenter, we present a summary of best practices, based on our experiences, for each of the 4 categories of Stage 3 Status outlined by the ACGME. In an era of globalization, we must learn from pandemics, a call made after the Ebola outbreak in 2015.6 We recognize that this type of disruption could happen again with a possible second wave of COVID-19 or another emerging disease.7 Thus, we emphasize “lessons learned” that are applicable to a wide range of residency training programs facing various clinical crises.

Ensuring adequate resources and training

Within the context of Stage 3 Status, residency programs have the flexibility to increase residents’ availability in the clinical care setting. However, programs must ensure the safety of both patients and residents.

Continue to: Measures to decrease risk of infection...

Measures to decrease risk of infection

One critical resource needed to protect patients and residents is personal protective equipment (PPE). Online instruction and in-person training were used to educate residents and staff on appropriate techniques for donning, doffing, and conserving PPE. Surgical teams were limited to 1 surgeon and 1 resident in each case. In an effort to limit direct contact with COVID-19 infected patients, the number of health care providers rounding on inpatients was restricted, and phone or video conversations were used for communication.

The workforce was modified to decrease exposure to infection and maintain a reserve of healthy residents who were working from home—anticipating that some residents would become ill and this reserve would be called for duty. Similar to other specialties, our programs organized the workforce by arranging residents into teams in which residents worked a number of shifts in a row.8-12 Regular block schedules were disrupted and non-core rotations were deferred.

As surgeries were canceled and outpatient visits curtailed, many rotations required less resident coverage. Residents were reassigned from rotations where clinical work was suspended to accommodate increased staffing needs in other areas, while accounting for residents who were ill or on leave for postexposure quarantine. Typically, residents worked 12-hour shifts for 3 to 6 days followed by several days off or days working remotely. This team-based strategy decreased the number of residents exposed to COVID-19 at one time, provided time for recuperation, encouraged camaraderie, and enabled residents working remotely to coordinate care and participate in telehealth without direct patient contact.

To minimize high-risk exposure of pregnant residents or residents with underlying health conditions, these residents also worked remotely. Similar to other specialties, it was important to determine essential resident duties and enlist assistance from other clinicians, such as fellows, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and midwives.

To protect residents and patients, maximizing testing of patients for COVID-19 was an important strategy. Based on early experience at 1 center with patients who were initially asymptomatic but later developed symptoms and tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), universal testing was implemented and endorsed by the New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force.13 Notably, 87.9% of patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of admission had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation. Because the asymptomatic carrier rate appears to be high in obstetric patients, testing of patients is paramount.3,14 Finally, suspending visitation (except for 1 support person) also was instrumental in decreasing the risk of infection to residents.13

Resources for residents with COVID-19

This pandemic placed residency program directors in an unusual situation as frontline caregivers for their own residents. It was imperative to track residents with physical symptoms, conduct testing when possible, and follow the course of residents with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. As serious illness and death have been reported among otherwise healthy young people, we ensured that our homebound residents were frequently monitored.15 At several of our centers, residents with COVID-19 from any program who chose to separate from their families were provided with alternative housing accommodations. In addition, some of our graduate medical education offices identified specific physicians to care for residents with COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization.

Continue to: Deployment to other specialties...

Deployment to other specialties

Several hospitals in the United States redeployed residents because of staffing shortages in high-impact settings.12 It was important for ObGyns to emphasize that the labor and delivery unit functions as the emergency ward for pregnant women, and that ObGyn residents possess skills specific to the care of these patients.

For our departments, we highlighted that external redeployment could adversely affect our workforce restructuring and, ultimately, patient care. We focused efforts on internal deployment or reassignment as much as possible. Some faculty and fellows in nonobstetric subspecialty areas were redirected to provide care on our inpatient obstetric services.

Educating residents

To maintain educational efforts with social distancing, we used videoconferencing to preserve the protected didactic education time that existed for our residents before the pandemic. This regularly scheduled, nonclinical time also was utilized to instruct residents on the rapidly changing clinical guidelines and to disseminate information about new institutional policies and procedures, ensuring that residents were adequately prepared for their new clinical work.

Work hour requirements

The ACGME requires that work hour limitations remain unchanged during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status. As the pandemic presented new challenges and stressors for residents inside and outside the workplace, ensuring adequate time off to rest and recover was critical for maintaining the resident workforce’s health and wellness.

Thus, our workforce restructuring plans accounted for work hour limitations. As detailed above, the restructuring was accomplished by cohorting residents into small teams that remained unchanged for several weeks. Most shifts were limited to 12 hours, residents continued to be assigned at least 1 day off each week, and daily schedules were structured to ensure at least 10 hours off between shifts. Time spent working remotely was included in work hour calculations.

In addition, residents on “jeopardy” who were available for those who needed to be removed from direct patient care were given at least 1 day off per week in which they could not be pulled for clinical duty. Finally, prolonged inpatient assignments were limited; after these assignments, residents were given increased time for rest and recuperation.

Ensuring adequate supervision

The expectation during Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status is that residents, with adequate supervision, provide care that is appropriate for their level of training. To adequately and safely supervise residents, faculty needed training to remain well informed about the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. This was accomplished through frequent communication and consultation with colleagues in infectious disease, occupational health, and guidance from national organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and information from our state health departments.

Faculty members were trained in safe donning and doffing of PPE and infection control strategies to ensure they could safely oversee and train residents in these practices. Faculty schedules were significantly altered to ensure an adequate workforce and adequate resident supervision. Faculty efforts were focused on areas of critical need—in our case inpatient obstetrics—with a smaller workforce assigned to outpatient services and inpatient gynecology and gynecologic oncology. Many ObGyn subspecialist faculty were redeployed to general ObGyn inpatient units, thus permitting appropriate resident supervision at all times. In the outpatient setting, faculty adjusted to the changing demands and learned to conduct and supervise telehealth visits.

Finally, for those whose residents were deployed to other services (for example, internal medicine, emergency medicine, or critical care), supervision became paramount. We checked in with our deployed residents daily to be sure that their supervision on those services was adequate. Considering the extreme complexity, rapidly changing understanding of the disease, and often tragic patient outcomes, it was essential to ensure appropriate support and supervision on “off service” deployment.

Continue to: Fellows functioning in core specialty...

Fellows functioning in core specialty

Anticipating the increased need for clinicians on the obstetric services, fellows in subspecialty areas were granted emergency privileges to act as attending faculty in the core specialty, supervising residents and providing patient care. On the other hand, some of those fellows, primarily in gynecologic oncology, were externally redeployed out of core specialty to internal medicine and critical care units. Careful consideration of the fellows’ needs for supervision and support in these roles was essential, and similar support measures that were put in place for our residents were offered to fellows.

In conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented diverse and complex challenges to the entire health care workforce. Because this crisis is widespread and likely will be lengthy, a sustained and organized response is required.16 We have highlighted unique challenges specific to residency programs and presented collective best practices from our experiences in ObGyn navigating these obstacles, which are applicable to many other programs.

The flexibility and relief afforded by the ACGME Stage 3 Pandemic Emergency Status designation allowed us to meet the needs of the surge of patients that required care while we maintained our educational framework and tenets of providing adequate resources and training, working within the confines of safe work hours, ensuring proper supervision, and granting attending privileges to fellows in their core specialty. ●

- Panahi L, Amiri M, Pouy S. Risks of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy; a narrative review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8e34.

- Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:415-426.

- Sutton D, Fuchs K, D'Alton M, et al. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163-2164.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Three stages of GME during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.acgme.org/COVID-19/Three-Stages-of-GME-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Emergency category maps/5-18-20: percentage of residents in each state/territory under pandemic emergency status. Percentage of residency and fellowship programs under ACGME COVID-19 pandemic emergency status (stage 3). https://dl.acgme.org/learn/course/sponsoring-institution-idea-exchange/emergency-category-maps/5-18-20-percentage-of-residents-in-each-state-territory-under-pandemic-emergency-status. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Gates B. The next epidemic--lessons from Ebola. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1381-1384.

- Pepe D, Martinello RA, Juthani-Mehta M. Involving physicians-in-training in the care of patients during epidemics. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:632-634.

- Crosby DL, Sharma A. Insights on otolaryngology residency training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:38-41.

- Kim CS, Lynch JB, Seth C, et al. One academic health system's early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95:1146-1148.

- Kogan M, Klein SE, Hannon CP, et al. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020; 28:e456-e464.

- Vargo E, Ali M, Henry F, et al. Cleveland Clinic Akron general urology residency program's COVID-19 experience. Urology. 2020;140:1-3.

- Zarzaur BL, Stahl CC, Greenberg JA, et al. Blueprint for restructuring a department of surgery in concert with the health care system during a pandemic: the University of Wisconsin experience. JAMA Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1386.

- New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force. Recommendations to the governor to promote increased choice and access to safe maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/governor.ny.gov/files/atoms/files/042920_CMTF_Recommendations.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Campbell KH, Tornatore JM, Lawrence KE, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among patients admitted for childbirth in southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520-2522.

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)--United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343-346.

- Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860-868.

- Panahi L, Amiri M, Pouy S. Risks of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy; a narrative review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8e34.

- Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:415-426.

- Sutton D, Fuchs K, D'Alton M, et al. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163-2164.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Three stages of GME during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.acgme.org/COVID-19/Three-Stages-of-GME-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Emergency category maps/5-18-20: percentage of residents in each state/territory under pandemic emergency status. Percentage of residency and fellowship programs under ACGME COVID-19 pandemic emergency status (stage 3). https://dl.acgme.org/learn/course/sponsoring-institution-idea-exchange/emergency-category-maps/5-18-20-percentage-of-residents-in-each-state-territory-under-pandemic-emergency-status. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Gates B. The next epidemic--lessons from Ebola. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1381-1384.

- Pepe D, Martinello RA, Juthani-Mehta M. Involving physicians-in-training in the care of patients during epidemics. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:632-634.

- Crosby DL, Sharma A. Insights on otolaryngology residency training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:38-41.

- Kim CS, Lynch JB, Seth C, et al. One academic health system's early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95:1146-1148.

- Kogan M, Klein SE, Hannon CP, et al. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020; 28:e456-e464.

- Vargo E, Ali M, Henry F, et al. Cleveland Clinic Akron general urology residency program's COVID-19 experience. Urology. 2020;140:1-3.

- Zarzaur BL, Stahl CC, Greenberg JA, et al. Blueprint for restructuring a department of surgery in concert with the health care system during a pandemic: the University of Wisconsin experience. JAMA Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1386.

- New York State COVID-19 Maternity Task Force. Recommendations to the governor to promote increased choice and access to safe maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/governor.ny.gov/files/atoms/files/042920_CMTF_Recommendations.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Campbell KH, Tornatore JM, Lawrence KE, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among patients admitted for childbirth in southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520-2522.

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)--United States, February 12-March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343-346.

- Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860-868.

Comment & Controversy

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

How do you feel about expectantly managing a well-dated pregnancy past 41 weeks’ gestation?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; FEBRUARY 2019)

Is it reasonable to choose the age of 40 for proposing an anticipation of labor induction?

In physiologic ongoing pregnancies (whether they are spontaneous or autologous in vitro fertilization [IVF] or heterologous IVF), the evidence for anticipating labor induction based upon the only factor of age (after 40 years) is missing. Nonetheless, the number of women becoming pregnant at an older age is expected to increase, and from my perspective, to induce all physiologic pregnancies at term by 41 weeks and 5 days’ gestation does not appear to be best practice. I favor the idea of all women aged 40 and older to start labor induction earlier (for instance, to offer labor induction, with proper informed consent, by 41+ 0 and not 41+ 5 through 42+ 0 weeks of pregnancy).

Luca Bernardini, MD

La Spezia, Italy

Dr. Barbieri responds

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, our approach is to offer women ≥40 years of age induction of labor (IOL) at 39 weeks’ gestation, unless there is an obstetric contraindication to IOL. We believe that IOL at 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with a reduced risk of both cesarean delivery and a new diagnosis of hypertension.1

Reference

- Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy, UM, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513-523.

What is the optimal hormonal treatment for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD

(EDITORIAL; JANUARY 2020)

OCs and spironolactone study

I often recommend oral contraceptives (OCs) containing drospirenone for patients with polycyctic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-associated mild acne and hirsutism—since OCs are already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for acne, with similar effects as spironolactone. My patients seem to do well on an OC, and require only one medication. Of course, I would add spironolactone to the treatment regimen and switch OCs if she was not responding well.

Michael T. Cane, MD

Arlington, Texas

Dr. Barbieri responds

The Endocrine Society agrees with Dr. Cane’s approach, recommending the initiation of monotherapy with an estrogen-progestin followed by the addition of spironolactone if 6 months of monotherapy produces insufficient improvement in dermatologic symptoms of PCOS, including hirsutism and acne. Most contraceptives contain 3 mg or 4 mg of drospirenone, which is thought to have antiandrogenic effects similar to spironolactone 25 mg. I believe that spironolactone 100 mg provides more complete and rapid resolution of the dermatologic symptoms caused by PCOS. Hence, I initiate both an estrogen-progestin contraceptive with spironolactone.

Pregnancy of unknown location: Evidence-based evaluation and management

CASE Woman with bleeding in early pregnancy

A 31-year-old woman (G1P0) presents to the local emergency department (ED) due to bleeding in pregnancy. She reports a prior open appendectomy for ruptured appendix; she denies a history of sexually transmitted infections, smoking, and contraception use. She reports having regular menstrual cycles and trying to conceive with her husband for 18 months without success until now.

The patient reports that the previous week she took a home pregnancy test that was positive; she endorses having dark brown spotting for the past 2 days but denies pain. Based on the date of her last menstrual period, gestational age is estimated to be 5 weeks and 1 day. Her human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level is 1,670 mIU/mL. Transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrates a normal uterus with an endometrial thickness of 10 mm, no evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), normal adnexa bilaterally, and scant free fluid in the pelvis.

Identifying and evaluating pregnancy of unknown location

A pregnancy of unknown location (PUL) is defined by a positive serum hCG level in the absence of a visualized IUP or ectopic pregnancy (EP) by pelvic ultrasonography.

Because of variations in screening tools and clinical practices between institutions and care settings (for example, EDs versus specialized outpatient offices), the incidence of PUL is difficult to capture. In specialized early pregnancy clinics, the rate is 8% to 10%, whereas in the ED setting, the PUL rate has been reported to be as high as 42%.1-6 While approximately 98% to 99% of all pregnancies are intrauterine, only 30% of PULs will continue to develop as viable ongoing intrauterine gestations.7-9 The remainder are revealed as failing IUPs or EPs. To counsel patients, set expectations, and triage to appropriate management, it is critical to diagnose pregnancy location as efficiently as possible.

Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancies represent only 1% to 2% of conceptions (both spontaneous and through assisted reproduction) and occur most commonly in the fallopian tube, although EPs also can implant in the cornua of the uterus, the cervix, cesarean scar, and more rarely on the ovary or abdominal viscera.10,11 Least common, heterotopic pregnancies—in which an IUP coexists with an EP—occur in 1 in 4,000 to 30,000 pregnancies, more commonly in women who used assisted reproduction.11

Major risk factors for EP include a history of tubal surgery, sexually transmitted infections (particularly Chlamydia trachomatis), pelvic inflammatory disease, conception with an intrauterine device in situ, and a history of prior EP or tubal surgery, particularly prior tubal ligation; minor risk factors include a history of infertility (excluding known tubal factor infertility) or smoking (in a dose-dependent manner).11,12 The concern for an EP is heightened in patients with these risk factors.

Because of the possibility of rupture and life-threatening hemorrhage, EP carries a risk of significant morbidity and mortality.13 Ruptured EPs account for approximately 2.7% of all maternal deaths each year.14 When diagnosed sufficiently early in a stable patient, most EPs can be managed medically with methotrexate, a folic acid antagonist.15 Ectopic pregnancies also may be managed surgically, and emergency surgery is indicated in women with evidence of EP rupture and intraperitoneal bleeding.

Continue to: Intrauterine pregnancy...

Intrauterine pregnancy

While excluding EP is critical, it is equally important to diagnose an IUP as expeditiously as possible to avoid inadvertent, destructive intervention. Diagnosis and management of a PUL can involve endometrial aspiration, which would interrupt an IUP and should be avoided until the possibility of a viable IUP has been eliminated in desired pregnancies. The inadvertent administration of methotrexate, a known teratogen, to a patient with an undiagnosed viable IUP can result in miscarriage, elective termination, or a live-born infant with significant malformations, all of which expose the administering physician to malpractice litigation.16,17

In desired pregnancies, it is essential to differentiate between a viable IUP, a nonviable IUP, and an EP to guide appropriate management and ensure patient safety, whereas exclusion of EP is the priority in undesired pregnancies.

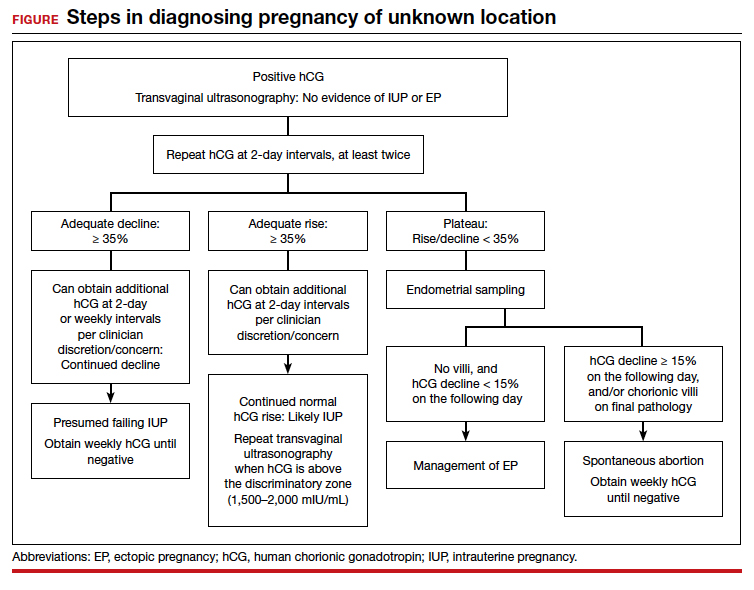

Tools for diagnosing pregnancy location

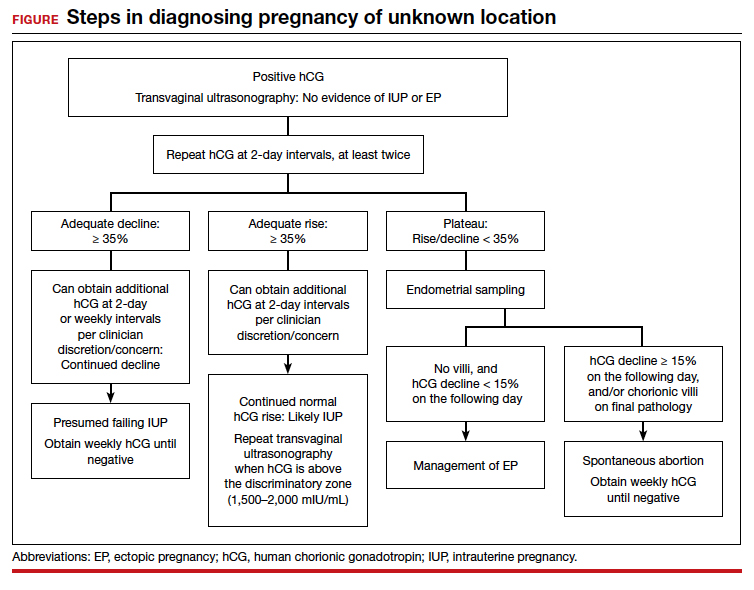

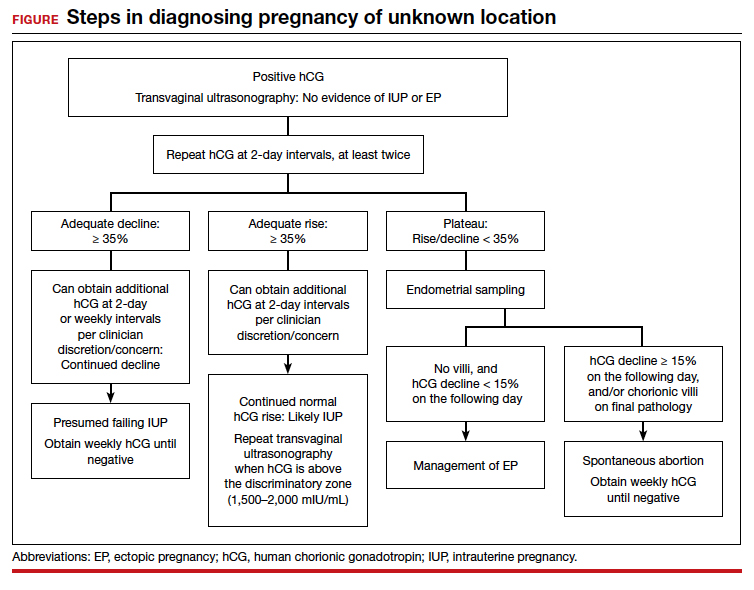

For diagnosing pregnancy location, serial hCG measurement, transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography, and outpatient endometrial aspiration are all relevant clinical tools. Pregnancy location can be diagnosed with either direct visualization of an IUP or EP by ultrasonography or with confirmed pathology (chorionic villi or trophoblast cells) from endometrial aspiration (FIGURE). A decline in hCG to an undetectable level following endometrial aspiration also is considered sufficient to diagnose a failed IUP, even in the absence of a confirmatory ultrasonography.

Trending hCG values

In stable patients with PUL, serum hCG levels are commonly measured at 2-day intervals, ideally for a minimum of 3 values. Conventional wisdom dictates that in viable IUPs, the hCG level should roughly double every 2 days. However, more recent data suggest that the threshold for minimum expected hCG rise for an ongoing IUP should be far lower when the pregnancy is desired.18 A less conservative cutoff can be considered when a pregnancy is not desired.

In a multisite cohort study of 1,005 women with PUL, a minimum hCG rise of 35% in 2 days captured the majority of IUPs, with a negative predictive value of 97.2% for IUP.19 Of note, although the cutoff of 35% was selected to reduce the risk of misdiagnosing an IUP as an EP, 7.7% of IUPs (and 16.8% of EPs) were still misclassified, showing that hCG trends must be interpreted in the context of other clinical data, including ultrasonography findings and patient symptoms and history.

A follow-up study demonstrated that hCG rises are lower (but still within this normal range) when the initial hCG value is higher, particularly greater than 3,000 mIU/mL.20

Studies show that the rate of spontaneous hCG decline in failing IUPs ranges from 12% to 47% in 2 days, falling more rapidly from higher starting hCG values.19,21 In a retrospective review of 443 women with spontaneously resolving PUL (presumed to be failing IUPs), the minimum 2-day decline in hCG was 35%.22 Any spontaneous hCG decline less than 35% in 2 days in a PUL should raise physician concern for EP.

Conversely, EPs do not demonstrate predictable hCG trends and can mimic the hCG trends of viable or failing IUPs. Although typically half of EPs present with an increasing hCG value and half present with a decreasing hCG value, the majority (71%) demonstrate a slower rate of change than either a viable IUP or a miscarriage.11 This slower change (plateau) should heighten the clinician’s suspicion for an EP.

Continue to: Progesterone levels...

Progesterone levels

A progesterone level often is used to attempt to determine pregnancy viability in women who are not receiving progesterone supplementation, although it ultimately has limited utility. While far less sensitive than an hCG value trend, a serum progesterone level of less than 5 to 10 ng/mL is a rough marker of nonviable pregnancy.23

In a large meta-analysis of women with pain and bleeding, 96.8% of pregnancies with a single progesterone level of less than 10 ng/mL were nonviable.23 When an inconclusive ultrasonography was documented in addition to symptoms of pain and bleeding, 99.2% of pregnancies with a progesterone level of less than 3.2 to 6 ng/mL were nonviable.

Progesterone’s usefulness in assessing for a PUL is limited: While progesterone levels may indicate nonviability, they provide no indication of pregnancy location (intrauterine or ectopic).

Alternative serologic markers

Various other reproductive and pregnancy-related hormones have been investigated for use in the diagnosis of pregnancy location in PULs, including activin A, inhibin A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A), placental-like growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, follistatin, and various microRNAs.24,25 While research into these biomarkers is ongoing, none have been studied in prospective trials, and they are not for use in current clinical care.

Pelvic ultrasonography

Pelvic ultrasonography is a crucial part of PUL assessment. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be interpreted in the context of the estimated gestational age of the pregnancy and serial hCG values, if available; the patient’s symptoms; and the sensitivity of the ultrasonography equipment, which also may be affected by variables that can reduce visualization, such as uterine fibroids and obesity.

The “discriminatory zone” refers to the hCG value above which an IUP should be visualized by ultrasonography. Generally, with an hCG value of 1,500 to 2,000 mIU/mL or greater, an IUP is expected to be seen with transvaginal sonography.3,26 Many exceptions to the discriminatory zone have been reported, however, including multiple pregnancies, which will have a higher hCG value at an earlier gestational age. Even in singleton pregnancies, viable IUPs have been documented as developing from PULs with an elevated initial hCG value as high as 4,300 mIU/mL.27 The discriminatory zone may vary among clinical hCG assays, and it also is affected by the quality and modernity of the ultrasonography equipment as well as by the ultrasonography operator’s experience and skill.28,29

The estimated gestational age, based on either the last menstrual period or assisted reproduction procedure, provides a helpful data point to guide expectations for ultrasonography findings.30 Using transvaginal ultrasonography in a normally progressing IUP, a gestational sac—typically measuring 2 to 3 mm—should be visualized at 5 weeks.15,30 At approximately 5.5 weeks, a yolk sac measuring 3 to 5 mm should appear. At 6 weeks, an embryo with cardiac activity should be visualized.

In a pregnancy reliably dated beyond 5 weeks, the lack of an intrauterine gestational sac is suspicious for, but not diagnostic of, an EP. Conversely, the visualization of a gestational sac alone (without a yolk sac) is insufficient to definitively exclude an EP, since a small fluid collection in the endometrium (a “pseudosac”) can convincingly mimic the appearance of a gestational sac, and a follow-up ultrasonography should be performed in such cases.

Among patients without ultrasonographic evidence of an IUP, endometrial thickness has been posited as a way to differentiate between IUP and EP.31,32 Evidence suggests that an endometrial stripe of at least 8 to 10 mm may be somewhat predictive of an IUP, while endometrial thickness below 8 mm is more concerning for EP. This clinical variable, however, has been shown repeatedly to lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for IUP and should be considered only within the entire clinical context.

Continue to: Endometrial aspiration...

Endometrial aspiration

A persistently abnormal hCG trend and an ultrasonography without evidence of an IUP—particularly with an hCG value above the discriminatory zone and/or with reliable pregnancy dating beyond 5 to 6 weeks—is highly concerning for either a failing IUP or an EP. Once a viable desired IUP is excluded beyond reasonable doubt through these measures, endometrial aspiration to determine pregnancy location is a reasonable next step in PUL management.

Endometrial aspiration can identify a failing IUP by detection of trophoblasts or chorionic villi on pathology and/or by a decline of at least 15% in hCG, measured on the day of endometrial aspiration and again the following day. Endometrial aspiration is effective even in clinical care settings that do not have rapid pathologic analysis available, as hCG measurement before and within 24 hours after the procedure still can be performed.

Vacuum aspiration (electric or manual) in an operating room or office setting is an effective tool for diagnosing pregnancy location.33,34 The use of an endometrial Pipelle for endometrial sampling (typically used for an office endometrial biopsy to diagnose hyperplasia or malignancy) is insufficient for determining pregnancy location.35 For all patients managed with this protocol, the hCG value ideally should be followed until it is undetectable, regardless of whether an EP or failing IUP was diagnosed. In rare cases, an EP may be diagnosed by a late plateau in hCG values, following an initial decline consistent with a failing IUP.

Utility for diagnosis. Retrospective studies in patients with PUL following in vitro fertilization have established the utility of outpatient endometrial aspiration with a Karman cannula, followed by a repeat hCG measurement on the day after the procedure.34,36 These data demonstrate that between 42% and 69% of women were ultimately diagnosed with a failed IUP following endometrial aspiration, thereby sparing them unnecessary exposure to methotrexate.

A decline in hCG levels of at least 15% within 24 hours after the procedure indicates that a failed IUP is the most likely diagnosis and further intervention is not indicated (although falling hCG values should be monitored for confirmation); confirmatory pathology with chorionic villi or trophoblasts was present in less than half of these women and is not necessary to diagnose a failed IUP.36 Women diagnosed with a failed IUP after endometrial aspiration also benefitted from a shorter time to resolution of the nonviable pregnancy by approximately 2 weeks.36