User login

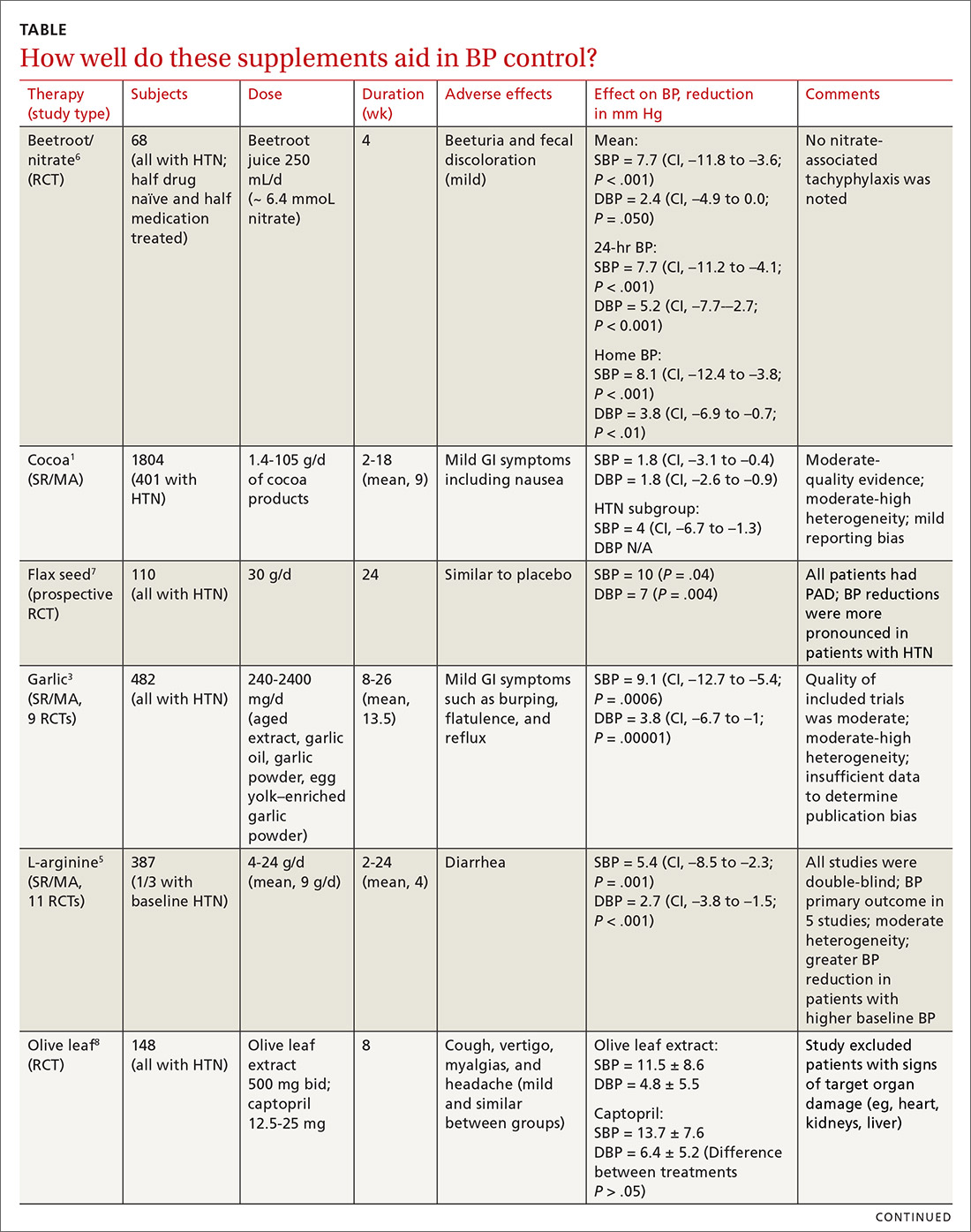

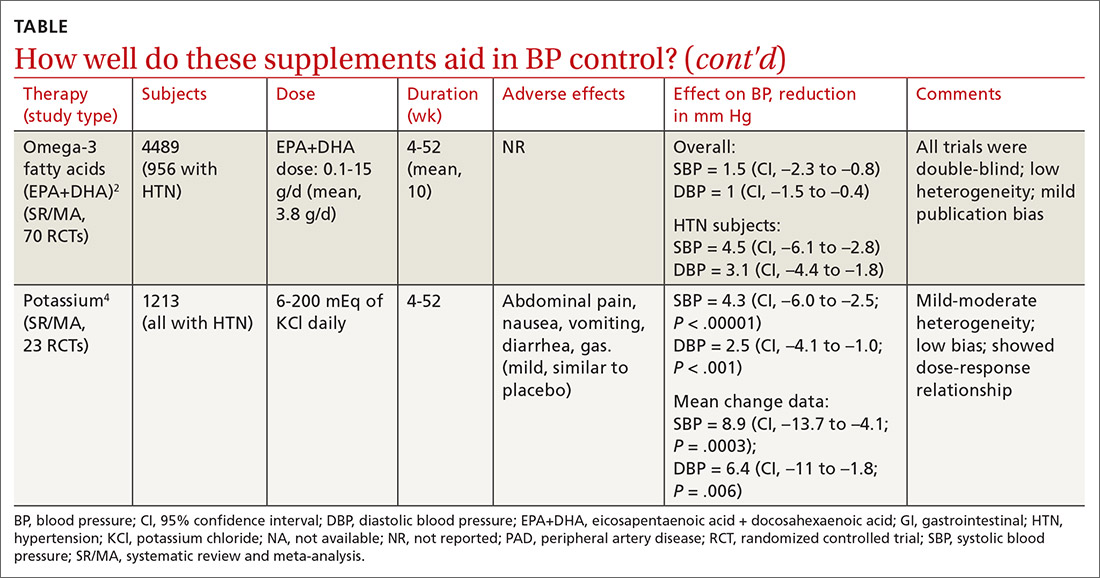

Does evidence support the use of supplements to aid in BP control?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

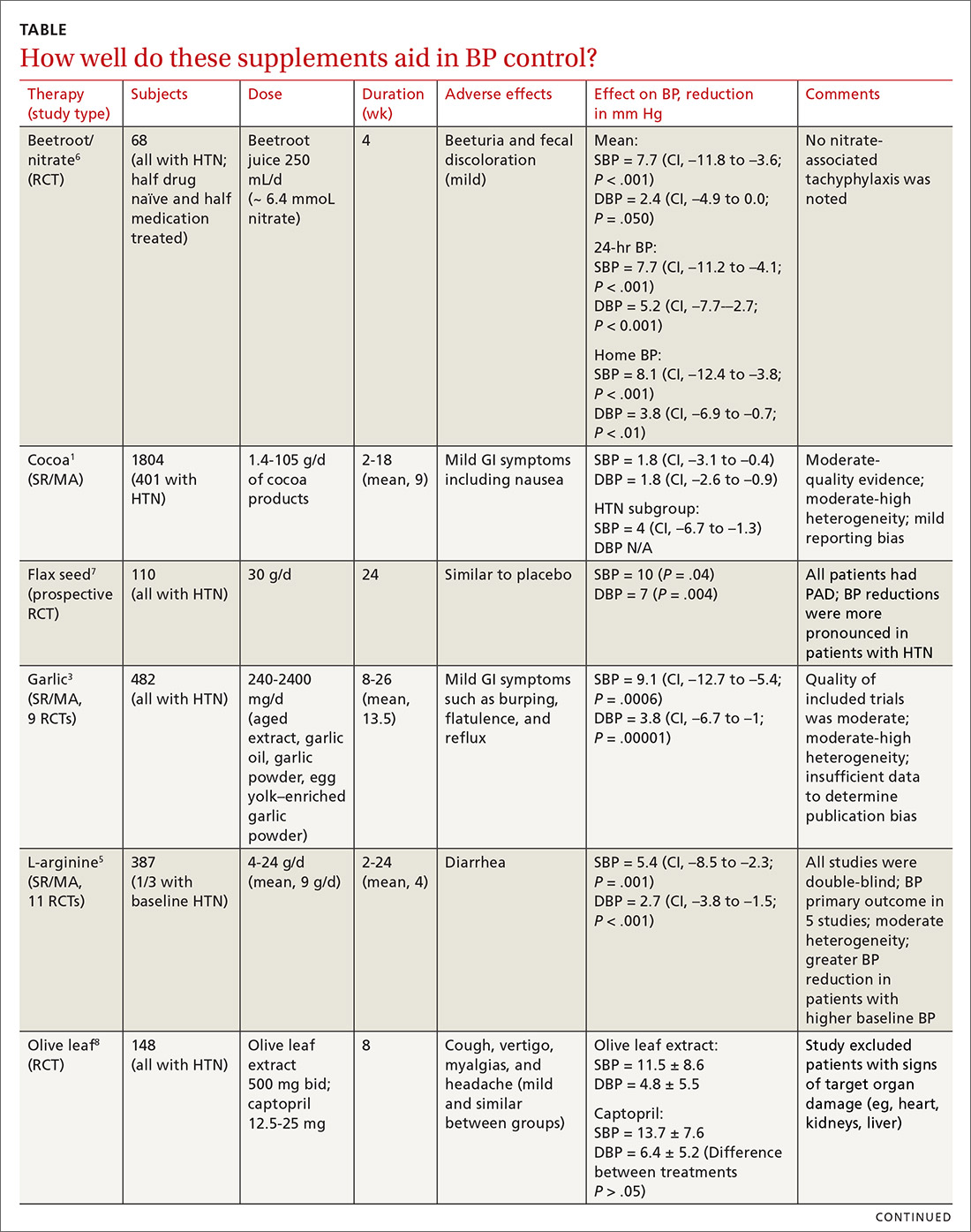

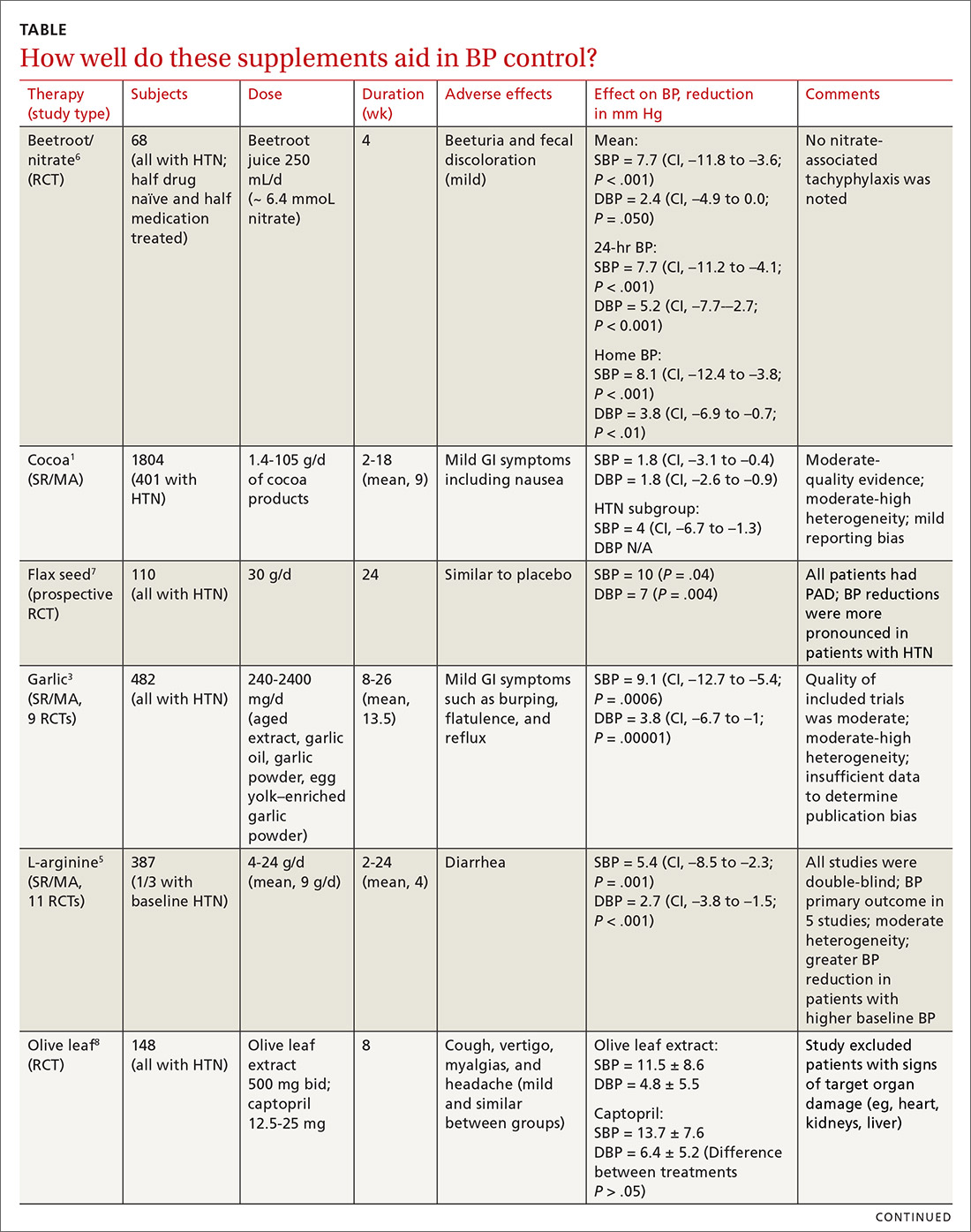

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

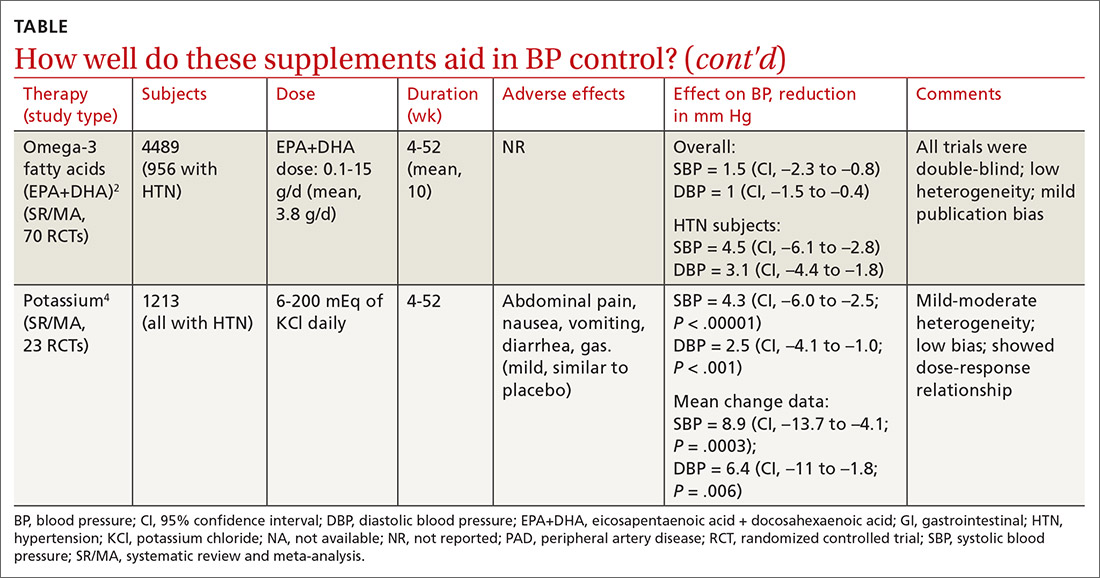

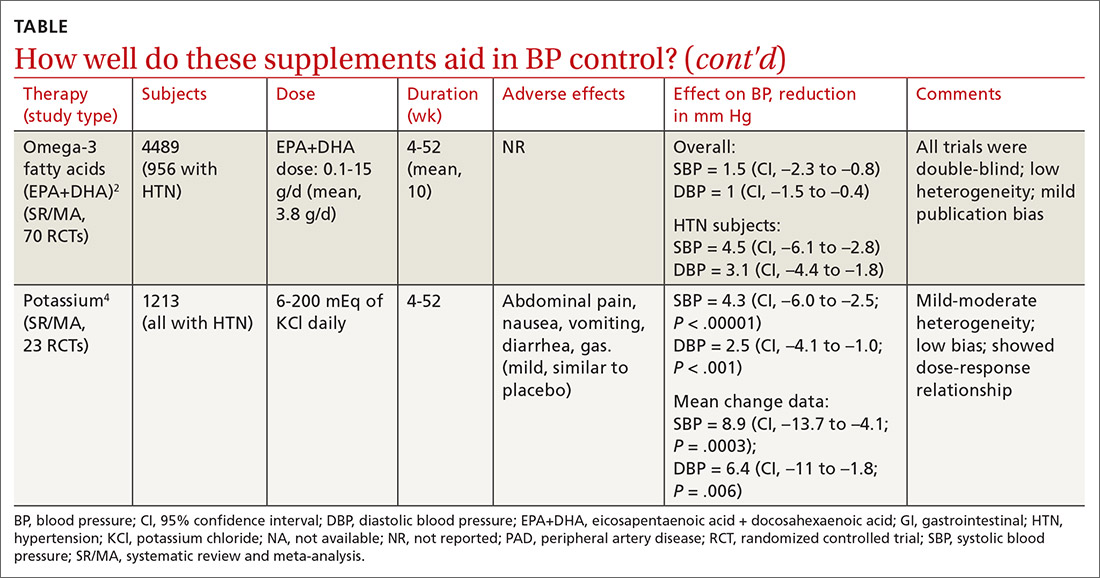

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

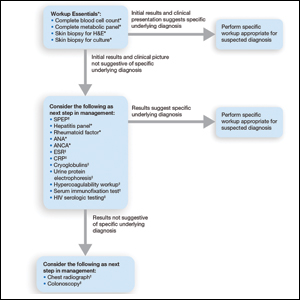

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. A number of well-tolerated natural therapies have been shown to reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP). (See Table1-8 for summary.) However, the studies don’t provide direct evidence of whether the decrease in BP is linked to patient-oriented outcomes. Nor do they allow definitive conclusions concerning the lasting nature of the reductions, because most studies were fewer than 6 months in duration (strength of recommendation: C, disease-oriented evidence).

AI can pinpoint COVID-19 from chest x-rays

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Conventional chest x-rays combined with artificial intelligence (AI) can identify lung damage from COVID-19 and differentiate coronavirus patients from other patients, improving triage efforts, new research suggests.

The AI tool – developed by Jason Fleischer, PhD, and graduate student Mohammad Tariqul Islam, both from Princeton (N.J.) University – can distinguish COVID-19 patients from those with pneumonia or normal lung tissue with an accuracy of more than 95%.

“We were able to separate the COVID-19 patients with very high fidelity,” Dr. Fleischer said in an interview. “If you give me an x-ray now, I can say with very high confidence whether a patient has COVID-19.”

The diagnostic tool pinpoints patterns on x-ray images that are too subtle for even trained experts to notice. The precision of CT scanning is similar to that of the AI tool, but CT costs much more and has other disadvantages, said Dr. Fleischer, who presented his findings at the virtual European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020.

“CT is more expensive and uses higher doses of radiation,” he said. “Another big thing is that not everyone has tomography facilities – including a lot of rural places and developing countries – so you need something that’s on the spot.”

With machine learning, Dr. Fleischer analyzed 2,300 x-ray images: 1,018 “normal” images from patients who had neither pneumonia nor COVID-19, 1,011 from patients with pneumonia, and 271 from patients with COVID-19.

The AI tool uses a neural network to refine the number and type of lung features being tracked. A UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) clustering algorithm then looks for similarities and differences in those images, he explained.

“We, as users, knew which type each x-ray was – normal, pneumonia positive, or COVID-19 positive – but the network did not,” he added.

Clinicians have observed two basic types of lung problems in COVID-19 patients: pneumonia that fills lung air sacs with fluid and dangerously low blood-oxygen levels despite nearly normal breathing patterns. Because treatment can vary according to type, it would be beneficial to quickly distinguish between them, Dr. Fleischer said.

The AI tool showed that there is a distinct difference in chest x-rays from pneumonia-positive patients and healthy people, he said. It also demonstrated two distinct clusters of COVID-19–positive chest x-rays: those that looked like pneumonia and those with a more normal presentation.

The fact that “the AI system recognizes something unique in chest x-rays from COVID-19–positive patients” indicates that the computer is able to identify visual markers for coronavirus, he explained. “We currently do not know what these markers are.”

Dr. Fleischer said his goal is not to replace physician decision-making, but to supplement it.

“I’m uncomfortable with having computers make the final decision,” he said. “They often have a narrow focus, whereas doctors have the big picture in mind.”

This AI tool is “very interesting,” especially in the context of expanding AI applications in various specialties, said Thierry Fumeaux, MD, from Nyon (Switzerland) Hospital. Some physicians currently disagree on whether a chest x-ray or CT scan is the better tool to help diagnose COVID-19.

“It seems better than the human eye and brain” to pinpoint COVID-19 lung damage, “so it’s very attractive as a technology,” Dr. Fumeaux said in an interview.

And AI can be used to supplement the efforts of busy and fatigued clinicians who might be stretched thin by large caseloads. “I cannot read 200 chest x-rays in a day, but a computer can do that in 2 minutes,” he said.

But Dr. Fumeaux offered a caveat: “Pattern recognition is promising, but at the moment I’m not aware of papers showing that, by using AI, you’re changing anything in the outcome of a patient.”

Ideally, Dr. Fleischer said he hopes that AI will soon be able to accurately indicate which treatments are most effective for individual COVID-19 patients. And the technology might eventually be used to help with treatment decisions for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he noted.

But he needs more data before results indicate whether a COVID-19 patient would benefit from ventilator support, for example, and the tool can be used more widely. To contribute data or collaborate with Dr. Fleischer’s efforts, contact him.

“Machine learning is all about data, so you can find these correlations,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to use it to reassure a worried patient that their prognosis is good; to say that most of the people with symptoms like yours will be just fine.”

Dr. Fleischer and Dr. Fumeaux have declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Small weight loss produces impressive drop in type 2 diabetes risk

Intentional loss of a median of just 13% of body weight reduces the relative risk of developing type 2 diabetes by around 40% in people with obesity, among many other health benefits, shows a large real-world study in half a million adults.

Other findings associated with the same modest weight loss included a reduction in the risk of sleep apnea by 22%-27%, hypertension by 18%-25%, and dyslipidemia by 20%-22%.

Christiane Haase, PhD, of Novo Nordisk, led the work together with Nick Finer, MD, senior principal clinical scientist, Novo Nordisk.

“This is powerful evidence to say it is worthwhile to help people lose weight and that it is hugely beneficial. These are not small effects, and they show that weight loss has a huge impact on health. It’s extraordinary,” Dr. Finer asserted.

“These data show that if we treat obesity first, rather than the complications, we actually get big results in terms of health. This really should be a game-changer for those health care systems that are still prevaricating about treating obesity seriously,” he added.

The size of the study, of over 550,000 U.K. adults in primary care, makes it unique. In the real-world cohort, people who had lost 10%-25% of their body weight were followed for a mean 8 years to see how this affected their subsequent risk of obesity-related conditions. The results were presented during the virtual European and International Congress on Obesity.

“Weight loss was real-world without any artificial intervention and they experienced a real-life reduction in risk of various obesity-related conditions,” Dr. Haase said in an interview.

Carel Le Roux, MD, PhD, from the Diabetes Complications Research Centre, University College Dublin, welcomed the study because it showed those with obesity who maintained more than 10% weight loss experienced a significant reduction in the complications of obesity.

“In the study, intentional weight loss was achieved using mainly diets and exercise, but also some medications and surgical treatments. However, it did not matter how patients were able to maintain the 10% or more weight loss as regards the positive impact on complications of obesity,” he highlighted.

From a clinician standpoint, “it helps to consider all the weight-loss options available, but also for those who are not able to achieve weight-loss maintenance, to escalate treatment. This is now possible as we gain access to more effective treatments,” he added.

Also commenting on the findings, Matt Petersen, vice president of medical information and professional engagement at the American Diabetes Association, said: “It’s helpful to have further evidence that weight loss reduces risk for type 2 diabetes.”

However, “finding effective strategies to achieve and maintain long-term weight loss and maintenance remains a significant challenge,” he observed.

Large database of half a million people with obesity

For the research, anonymized data from over half a million patients documented in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink database, which holds information from 674 general practices in the United Kingdom, were linked to Hospital Episode Statistics and prescribing data to determine comorbidity outcomes.

At baseline, characteristics for the full study population included a median age of 54 years, around 50% of participants had hypertension, around 40% had dyslipidemia, and around 20% had type 2 diabetes. Less than 10% had sleep apnea, hip/knee osteoarthritis, or history of cardiovascular disease. All participants had a body mass index (BMI) of 25.0-50.0 kg/m2 at the start of the follow-up, between January 2001 and December 2010.

Patients may have been advised to lose weight, or take more exercise, or have been referred to a dietitian. Some had been prescribed antiobesity medications available between 2001 and 2010. (Novo Nordisk medications for obesity were unavailable during this period.) Less than 1% had been referred for bariatric surgery.

“This is typical of real-world management of obesity,” Dr. Haase pointed out.

Participants were divided into two categories based on their weight pattern during the 4-year period: one whose weight remained stable (492,380 individuals with BMI change within –5% to 5%) and one who lost weight (60,573 with BMI change –10% to –25%).

The median change in BMI in the weight-loss group was –13%. The researchers also extracted information on weight loss interventions and dietary advice to confirm intention to lose weight.

The benefits of losing 13% of body weight were then determined for three risk profiles: BMI reduction from 34.5 to 30 (obesity class I level); from 40.3 to 35 (obesity class II level), and from46 to 40 (obesity class III level).

Individuals with a baseline history of any particular outcome were excluded from the risk analysis for that same outcome. All analyses were adjusted for BMI, age, gender, smoking status, and baseline comorbidities.

Study strengths include the large number of participants and the relatively long follow-up period. But the observational nature of the study limits the ability to know the ways in which the participants who lost weight may have differed from those who maintained or gained weight, the authors said.

Type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea showed greatest risk reductions

The researchers looked at the risk reduction for various comorbidities after weight loss, compared with before weight loss. They also examined the risk reductions after weight loss, compared with someone who had always had a median 13% lower weight.

Effectively, the analysis provided a measure of the effect of risk reduction because of weight loss, compared with having that lower weight as a stable weight.

“The analysis asks if the person’s risk was reversed by the weight loss to the risk associated with that of the lower weight level,” explained Dr. Haase.

“We found that the risks of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were reversed while the risk of sleep apnea and hip/knee osteoarthritis showed some residual risk,” she added.

With sleep apnea there was a risk reduction of up to 27%, compared with before weight loss.

“This is a condition that can’t be easily reversed except with mechanical sleeping devices and it is underrecognized and causes a lot of distress. There’s actually a link between sleep apnea, diabetes, and hypertension in a two-way connection,” noted Dr. Finer, who is also honorary professor of cardiovascular medicine at University College London.

“A reduction of this proportion is impressive,” he stressed.

Dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes are well-known cardiovascular risk factors. “We did not see any impact on myocardial infarction,” which “might be due to length of follow-up,” noted Dr. Haase.

Response of type 2 diabetes to weight loss

Most patients in the study did not have type 2 diabetes at baseline, and Dr. Finer commented on how weight loss might affect type 2 diabetes risk.

“The complications of obesity resolve with weight loss at different speeds,” he said.

“Type 2 diabetes is very sensitive to weight loss and improvements are obvious in weeks to months.”

In contrast, reductions in risk of obstructive sleep apnea “take longer and might depend on the amount of weight lost.” And with osteoarthritis, “It’s hard to show improvement with weight loss because irreparable damage has [already] been done,” he explained.

The degree of improvement in diabetes because of weight loss is partly dependent on how long the person has had diabetes, Dr. Finer further explained. “If someone has less excess weight then the diabetes might have had a shorter duration and therefore response might be greater.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK, said: “We’ve known for a long time that carrying extra weight can increase your risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and this new study adds to the extensive body of evidence showing that losing some of this weight is associated with reduced risk.”

She acknowledged, however, that losing weight is difficult and that support is important: “We need government to urgently review provision of weight management services and take action to address the barriers to accessing them.”

Dr. Finer and Dr. Haase are both employees of Novo Nordisk. Dr. Le Roux reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intentional loss of a median of just 13% of body weight reduces the relative risk of developing type 2 diabetes by around 40% in people with obesity, among many other health benefits, shows a large real-world study in half a million adults.

Other findings associated with the same modest weight loss included a reduction in the risk of sleep apnea by 22%-27%, hypertension by 18%-25%, and dyslipidemia by 20%-22%.

Christiane Haase, PhD, of Novo Nordisk, led the work together with Nick Finer, MD, senior principal clinical scientist, Novo Nordisk.

“This is powerful evidence to say it is worthwhile to help people lose weight and that it is hugely beneficial. These are not small effects, and they show that weight loss has a huge impact on health. It’s extraordinary,” Dr. Finer asserted.

“These data show that if we treat obesity first, rather than the complications, we actually get big results in terms of health. This really should be a game-changer for those health care systems that are still prevaricating about treating obesity seriously,” he added.

The size of the study, of over 550,000 U.K. adults in primary care, makes it unique. In the real-world cohort, people who had lost 10%-25% of their body weight were followed for a mean 8 years to see how this affected their subsequent risk of obesity-related conditions. The results were presented during the virtual European and International Congress on Obesity.

“Weight loss was real-world without any artificial intervention and they experienced a real-life reduction in risk of various obesity-related conditions,” Dr. Haase said in an interview.

Carel Le Roux, MD, PhD, from the Diabetes Complications Research Centre, University College Dublin, welcomed the study because it showed those with obesity who maintained more than 10% weight loss experienced a significant reduction in the complications of obesity.

“In the study, intentional weight loss was achieved using mainly diets and exercise, but also some medications and surgical treatments. However, it did not matter how patients were able to maintain the 10% or more weight loss as regards the positive impact on complications of obesity,” he highlighted.

From a clinician standpoint, “it helps to consider all the weight-loss options available, but also for those who are not able to achieve weight-loss maintenance, to escalate treatment. This is now possible as we gain access to more effective treatments,” he added.

Also commenting on the findings, Matt Petersen, vice president of medical information and professional engagement at the American Diabetes Association, said: “It’s helpful to have further evidence that weight loss reduces risk for type 2 diabetes.”

However, “finding effective strategies to achieve and maintain long-term weight loss and maintenance remains a significant challenge,” he observed.

Large database of half a million people with obesity

For the research, anonymized data from over half a million patients documented in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink database, which holds information from 674 general practices in the United Kingdom, were linked to Hospital Episode Statistics and prescribing data to determine comorbidity outcomes.

At baseline, characteristics for the full study population included a median age of 54 years, around 50% of participants had hypertension, around 40% had dyslipidemia, and around 20% had type 2 diabetes. Less than 10% had sleep apnea, hip/knee osteoarthritis, or history of cardiovascular disease. All participants had a body mass index (BMI) of 25.0-50.0 kg/m2 at the start of the follow-up, between January 2001 and December 2010.

Patients may have been advised to lose weight, or take more exercise, or have been referred to a dietitian. Some had been prescribed antiobesity medications available between 2001 and 2010. (Novo Nordisk medications for obesity were unavailable during this period.) Less than 1% had been referred for bariatric surgery.

“This is typical of real-world management of obesity,” Dr. Haase pointed out.

Participants were divided into two categories based on their weight pattern during the 4-year period: one whose weight remained stable (492,380 individuals with BMI change within –5% to 5%) and one who lost weight (60,573 with BMI change –10% to –25%).

The median change in BMI in the weight-loss group was –13%. The researchers also extracted information on weight loss interventions and dietary advice to confirm intention to lose weight.

The benefits of losing 13% of body weight were then determined for three risk profiles: BMI reduction from 34.5 to 30 (obesity class I level); from 40.3 to 35 (obesity class II level), and from46 to 40 (obesity class III level).

Individuals with a baseline history of any particular outcome were excluded from the risk analysis for that same outcome. All analyses were adjusted for BMI, age, gender, smoking status, and baseline comorbidities.

Study strengths include the large number of participants and the relatively long follow-up period. But the observational nature of the study limits the ability to know the ways in which the participants who lost weight may have differed from those who maintained or gained weight, the authors said.

Type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea showed greatest risk reductions

The researchers looked at the risk reduction for various comorbidities after weight loss, compared with before weight loss. They also examined the risk reductions after weight loss, compared with someone who had always had a median 13% lower weight.

Effectively, the analysis provided a measure of the effect of risk reduction because of weight loss, compared with having that lower weight as a stable weight.

“The analysis asks if the person’s risk was reversed by the weight loss to the risk associated with that of the lower weight level,” explained Dr. Haase.

“We found that the risks of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were reversed while the risk of sleep apnea and hip/knee osteoarthritis showed some residual risk,” she added.

With sleep apnea there was a risk reduction of up to 27%, compared with before weight loss.

“This is a condition that can’t be easily reversed except with mechanical sleeping devices and it is underrecognized and causes a lot of distress. There’s actually a link between sleep apnea, diabetes, and hypertension in a two-way connection,” noted Dr. Finer, who is also honorary professor of cardiovascular medicine at University College London.

“A reduction of this proportion is impressive,” he stressed.

Dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes are well-known cardiovascular risk factors. “We did not see any impact on myocardial infarction,” which “might be due to length of follow-up,” noted Dr. Haase.

Response of type 2 diabetes to weight loss

Most patients in the study did not have type 2 diabetes at baseline, and Dr. Finer commented on how weight loss might affect type 2 diabetes risk.

“The complications of obesity resolve with weight loss at different speeds,” he said.

“Type 2 diabetes is very sensitive to weight loss and improvements are obvious in weeks to months.”

In contrast, reductions in risk of obstructive sleep apnea “take longer and might depend on the amount of weight lost.” And with osteoarthritis, “It’s hard to show improvement with weight loss because irreparable damage has [already] been done,” he explained.

The degree of improvement in diabetes because of weight loss is partly dependent on how long the person has had diabetes, Dr. Finer further explained. “If someone has less excess weight then the diabetes might have had a shorter duration and therefore response might be greater.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK, said: “We’ve known for a long time that carrying extra weight can increase your risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and this new study adds to the extensive body of evidence showing that losing some of this weight is associated with reduced risk.”

She acknowledged, however, that losing weight is difficult and that support is important: “We need government to urgently review provision of weight management services and take action to address the barriers to accessing them.”

Dr. Finer and Dr. Haase are both employees of Novo Nordisk. Dr. Le Roux reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intentional loss of a median of just 13% of body weight reduces the relative risk of developing type 2 diabetes by around 40% in people with obesity, among many other health benefits, shows a large real-world study in half a million adults.

Other findings associated with the same modest weight loss included a reduction in the risk of sleep apnea by 22%-27%, hypertension by 18%-25%, and dyslipidemia by 20%-22%.

Christiane Haase, PhD, of Novo Nordisk, led the work together with Nick Finer, MD, senior principal clinical scientist, Novo Nordisk.

“This is powerful evidence to say it is worthwhile to help people lose weight and that it is hugely beneficial. These are not small effects, and they show that weight loss has a huge impact on health. It’s extraordinary,” Dr. Finer asserted.

“These data show that if we treat obesity first, rather than the complications, we actually get big results in terms of health. This really should be a game-changer for those health care systems that are still prevaricating about treating obesity seriously,” he added.

The size of the study, of over 550,000 U.K. adults in primary care, makes it unique. In the real-world cohort, people who had lost 10%-25% of their body weight were followed for a mean 8 years to see how this affected their subsequent risk of obesity-related conditions. The results were presented during the virtual European and International Congress on Obesity.

“Weight loss was real-world without any artificial intervention and they experienced a real-life reduction in risk of various obesity-related conditions,” Dr. Haase said in an interview.

Carel Le Roux, MD, PhD, from the Diabetes Complications Research Centre, University College Dublin, welcomed the study because it showed those with obesity who maintained more than 10% weight loss experienced a significant reduction in the complications of obesity.

“In the study, intentional weight loss was achieved using mainly diets and exercise, but also some medications and surgical treatments. However, it did not matter how patients were able to maintain the 10% or more weight loss as regards the positive impact on complications of obesity,” he highlighted.

From a clinician standpoint, “it helps to consider all the weight-loss options available, but also for those who are not able to achieve weight-loss maintenance, to escalate treatment. This is now possible as we gain access to more effective treatments,” he added.

Also commenting on the findings, Matt Petersen, vice president of medical information and professional engagement at the American Diabetes Association, said: “It’s helpful to have further evidence that weight loss reduces risk for type 2 diabetes.”

However, “finding effective strategies to achieve and maintain long-term weight loss and maintenance remains a significant challenge,” he observed.

Large database of half a million people with obesity

For the research, anonymized data from over half a million patients documented in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink database, which holds information from 674 general practices in the United Kingdom, were linked to Hospital Episode Statistics and prescribing data to determine comorbidity outcomes.

At baseline, characteristics for the full study population included a median age of 54 years, around 50% of participants had hypertension, around 40% had dyslipidemia, and around 20% had type 2 diabetes. Less than 10% had sleep apnea, hip/knee osteoarthritis, or history of cardiovascular disease. All participants had a body mass index (BMI) of 25.0-50.0 kg/m2 at the start of the follow-up, between January 2001 and December 2010.

Patients may have been advised to lose weight, or take more exercise, or have been referred to a dietitian. Some had been prescribed antiobesity medications available between 2001 and 2010. (Novo Nordisk medications for obesity were unavailable during this period.) Less than 1% had been referred for bariatric surgery.

“This is typical of real-world management of obesity,” Dr. Haase pointed out.

Participants were divided into two categories based on their weight pattern during the 4-year period: one whose weight remained stable (492,380 individuals with BMI change within –5% to 5%) and one who lost weight (60,573 with BMI change –10% to –25%).

The median change in BMI in the weight-loss group was –13%. The researchers also extracted information on weight loss interventions and dietary advice to confirm intention to lose weight.

The benefits of losing 13% of body weight were then determined for three risk profiles: BMI reduction from 34.5 to 30 (obesity class I level); from 40.3 to 35 (obesity class II level), and from46 to 40 (obesity class III level).

Individuals with a baseline history of any particular outcome were excluded from the risk analysis for that same outcome. All analyses were adjusted for BMI, age, gender, smoking status, and baseline comorbidities.

Study strengths include the large number of participants and the relatively long follow-up period. But the observational nature of the study limits the ability to know the ways in which the participants who lost weight may have differed from those who maintained or gained weight, the authors said.

Type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea showed greatest risk reductions

The researchers looked at the risk reduction for various comorbidities after weight loss, compared with before weight loss. They also examined the risk reductions after weight loss, compared with someone who had always had a median 13% lower weight.

Effectively, the analysis provided a measure of the effect of risk reduction because of weight loss, compared with having that lower weight as a stable weight.

“The analysis asks if the person’s risk was reversed by the weight loss to the risk associated with that of the lower weight level,” explained Dr. Haase.

“We found that the risks of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were reversed while the risk of sleep apnea and hip/knee osteoarthritis showed some residual risk,” she added.

With sleep apnea there was a risk reduction of up to 27%, compared with before weight loss.

“This is a condition that can’t be easily reversed except with mechanical sleeping devices and it is underrecognized and causes a lot of distress. There’s actually a link between sleep apnea, diabetes, and hypertension in a two-way connection,” noted Dr. Finer, who is also honorary professor of cardiovascular medicine at University College London.

“A reduction of this proportion is impressive,” he stressed.

Dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes are well-known cardiovascular risk factors. “We did not see any impact on myocardial infarction,” which “might be due to length of follow-up,” noted Dr. Haase.

Response of type 2 diabetes to weight loss

Most patients in the study did not have type 2 diabetes at baseline, and Dr. Finer commented on how weight loss might affect type 2 diabetes risk.

“The complications of obesity resolve with weight loss at different speeds,” he said.

“Type 2 diabetes is very sensitive to weight loss and improvements are obvious in weeks to months.”

In contrast, reductions in risk of obstructive sleep apnea “take longer and might depend on the amount of weight lost.” And with osteoarthritis, “It’s hard to show improvement with weight loss because irreparable damage has [already] been done,” he explained.

The degree of improvement in diabetes because of weight loss is partly dependent on how long the person has had diabetes, Dr. Finer further explained. “If someone has less excess weight then the diabetes might have had a shorter duration and therefore response might be greater.”

Lucy Chambers, PhD, head of research communications at Diabetes UK, said: “We’ve known for a long time that carrying extra weight can increase your risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and this new study adds to the extensive body of evidence showing that losing some of this weight is associated with reduced risk.”

She acknowledged, however, that losing weight is difficult and that support is important: “We need government to urgently review provision of weight management services and take action to address the barriers to accessing them.”

Dr. Finer and Dr. Haase are both employees of Novo Nordisk. Dr. Le Roux reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

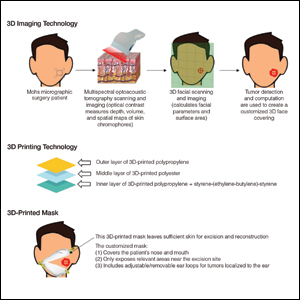

Use of 3D Technology to Support Dermatologists Returning to Practice Amid COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Practice Points

- Coronavirus disease 19 has overwhelmed our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology.

- There are concerns about shortages of personal protective equipment to safely care for patients.

- 3-Dimensional imaging and printing technologies can be harnessed to create face coverings and face shields for the dermatology outpatient setting.

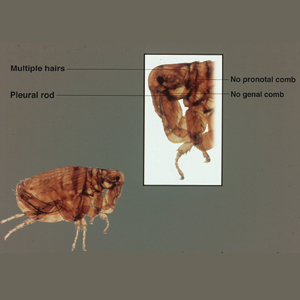

What’s Eating You? Oriental Rat Flea (Xenopsylla cheopis)

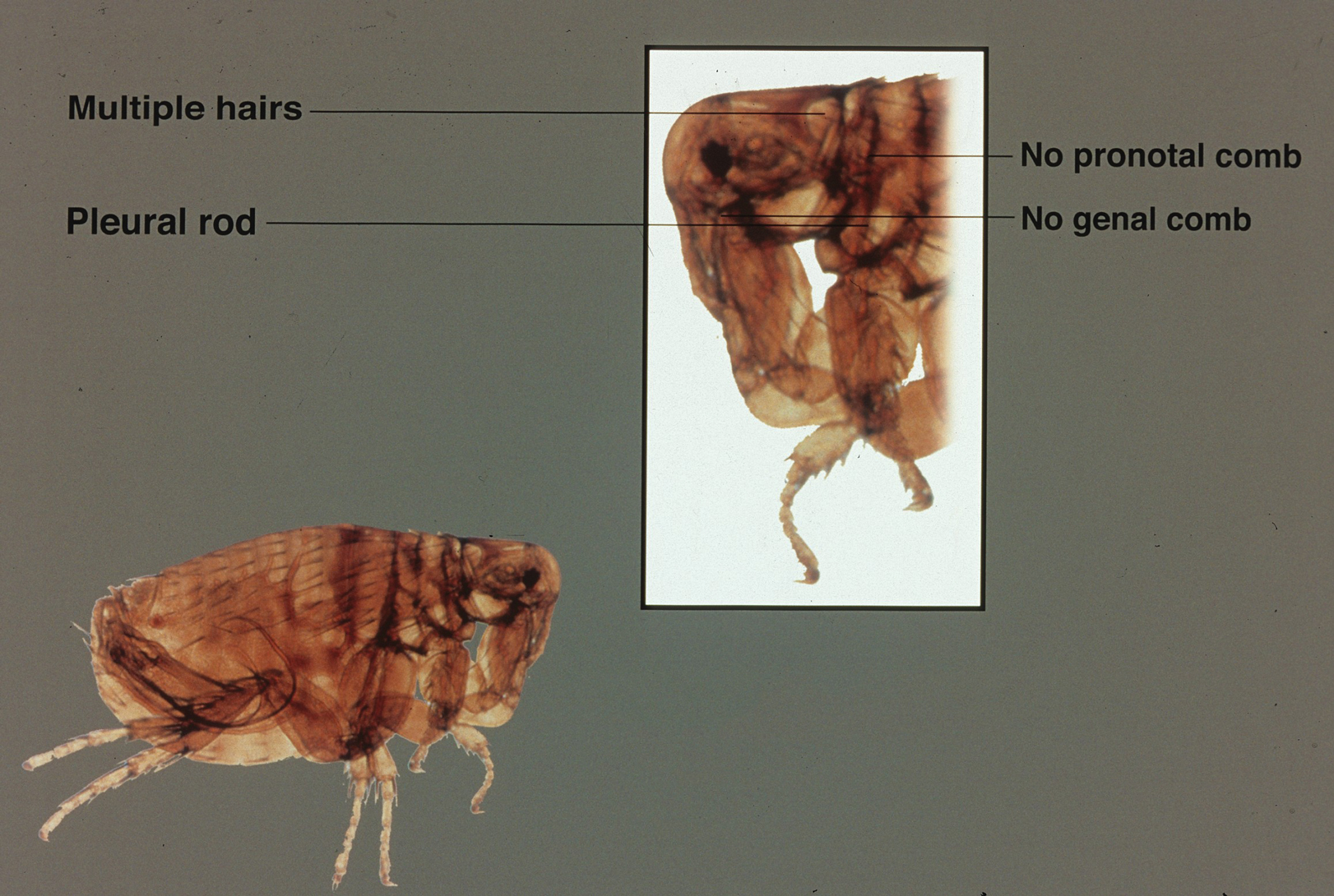

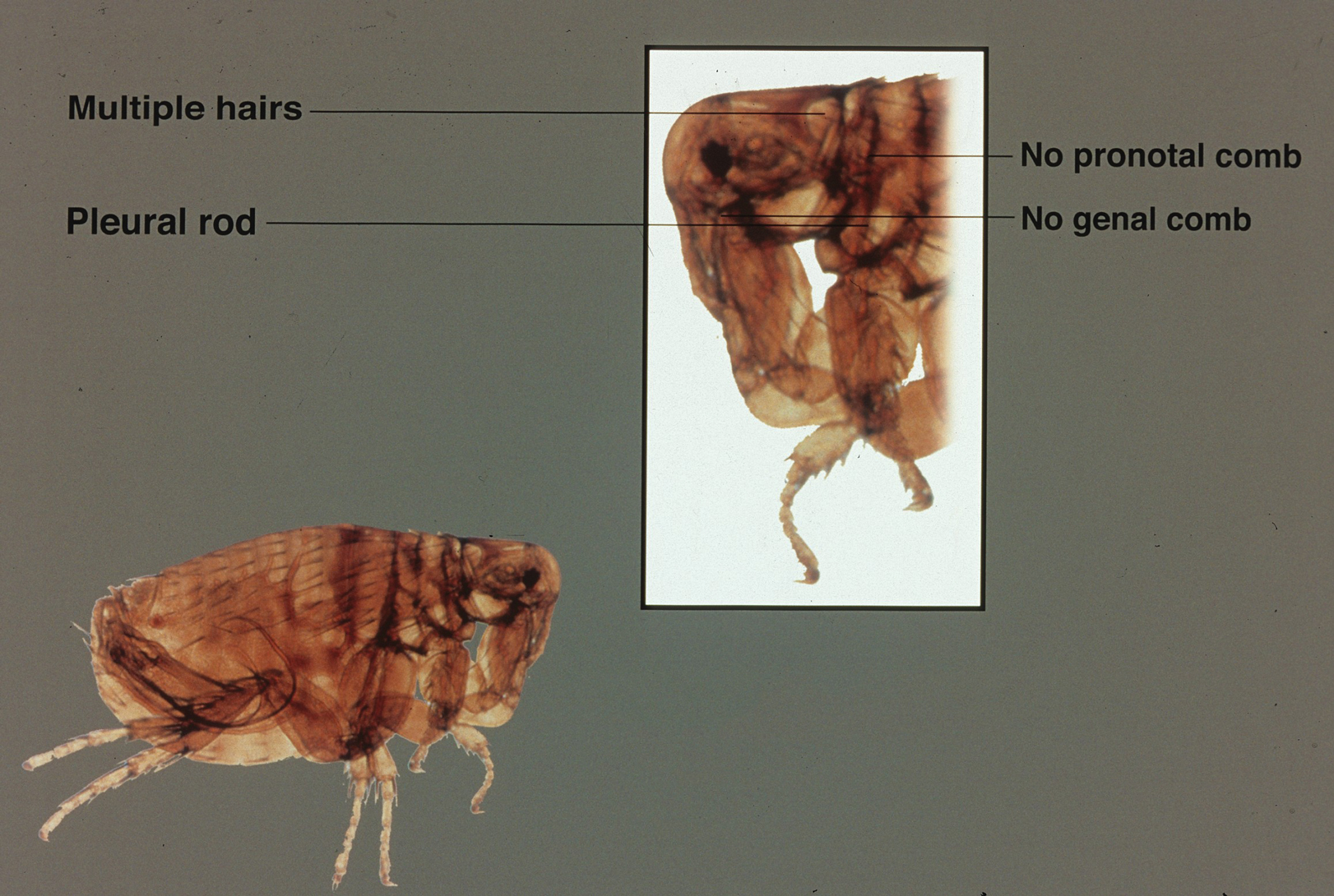

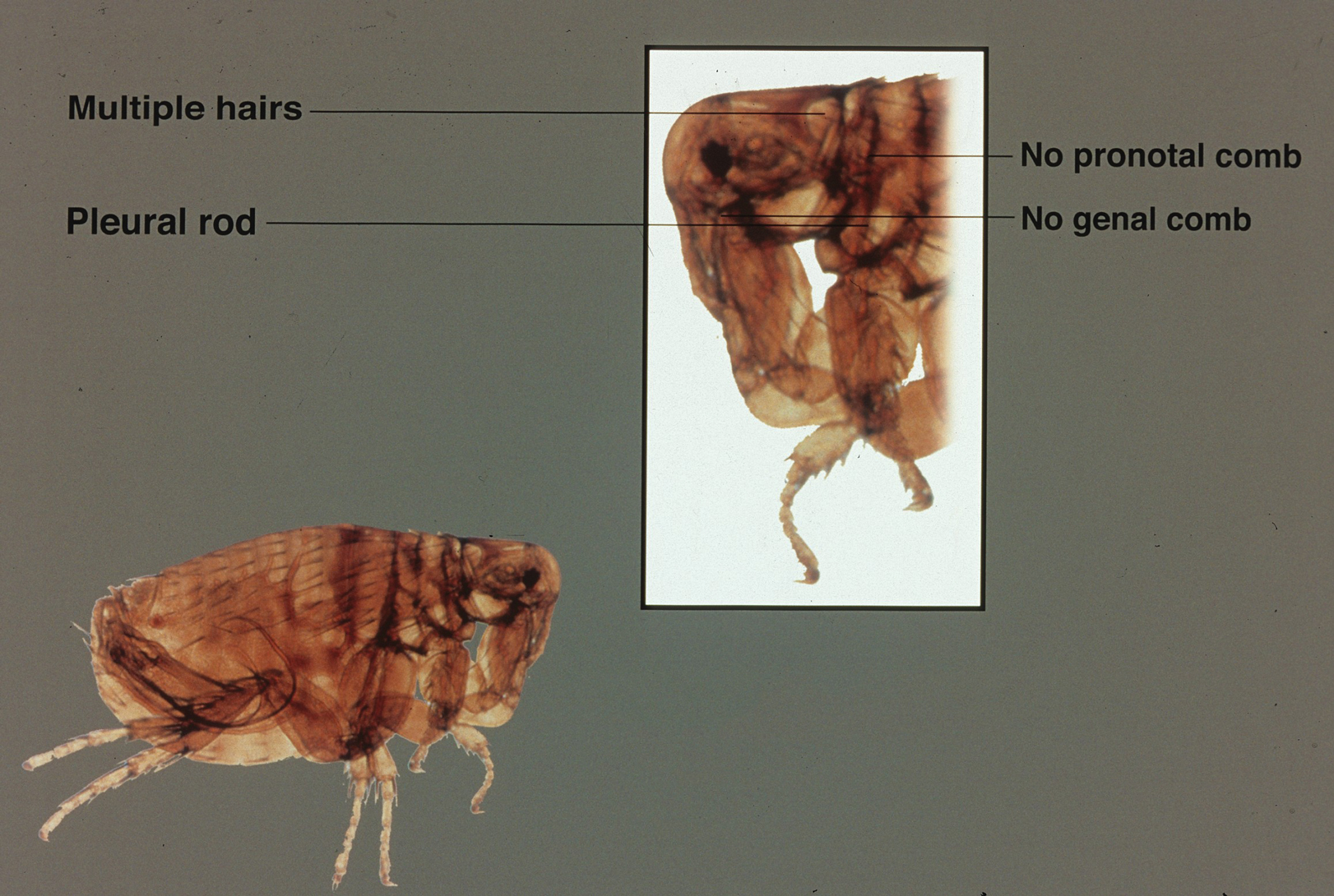

A dult Siphonaptera (fleas) are highly adapted to life on the surface of their hosts. Their small 2- to 10-mm bodies are laterally flattened and wingless. They utilize particularly strong hind legs for jumping up to 150 times their body length and backward-directed spines on their legs and bodies for moving forward through fur, hair, and feathers. Xenopsylla cheopis , the oriental rat flea, lacks pronotal and genal combs and has a mesopleuron divided by internal scleritinization (Figure). These features differentiate the species from its close relatives, Ctenocephalides (cat and dog fleas), which have both sets of combs, as well as Pulex irritans (human flea), which do not have a divided mesopleuron. 1,2

Flea-borne infections are extremely important to public health and are present throughout the world. Further, humidity and warmth are essential for the life cycle of many species of fleas. Predicted global warming likely will increase their distribution, allowing the spread of diseases they carry into previously untouched areas.1 Therefore, it is important to continue to examine species that carry particularly dangerous pathogens, such as X cheopis.

Disease Vector

Xenopsylla cheopis primarily is known for being a vector in the transmission of Yersinia pestis, the etiologic agent of the plague. Plague occurs in 3 forms: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. It has caused major epidemics throughout history, the most widely known being the Black Death, which lasted for 130 years, beginning in the 1330s in China and spreading into Europe where it wiped out one-third of the population. However, bubonic plague is thought to have caused documented outbreaks as early as 320

Between January 2010 and December 2015, 3248 cases of plague in humans were reported, resulting in 584 deaths worldwide.5 It is thought that the plague originated in Central Asia, and this area still is a focus of disease. However, the at-risk population is reduced to breeders and hunters of gerbils and marmots, the main reservoirs in the area. In Africa, 4 countries still regularly report cases, with Madagascar being the most severely affected country in the world.5 The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Tanzania also are affected. The Americas also experience the plague. There are sporadic cases of bubonic plague in the northwest corner of Peru, mostly in rural areas. In the western United States, plague circulates among wild rodents, resulting in several reported cases each year, with the most recent confirmed case noted in California in August 2020.5,6 Further adding to its relevance, Y pestis is one of several organisms most likely to be used as a biologic weapon.3,4

Due to the historical and continued significance of Y pestis, many studies have been performed over the decades regarding its association with X cheopis. It has been discovered that fleas transmit the bacteria to the host in 2 ways. The most well-defined form of transmission occurs after an incubation period of Y pestis in the flea for 7 to 31 days. During this time, the bacteria form a dense biofilm on a valve in the flea foregut—the proventriculus—interfering with its function, which allows regurgitation of the blood and the bacteria it contains into the bite site and consequently disease transmission. The proventriculus can become completely blocked in some fleas, preventing any blood from reaching the midgut and causing starvation. In these scenarios, the flea will make continuous attempts to feed, increasing transmission.7 The hemin storage gene, hms, encoding the second messenger molecule cyclic di-GMP plays a critical role in biofilm formation and proventricular blockage.8 The phosphoheptose isomerase gene, GmhA, also has been elucidated as crucial in late transmission due to its role in biofilm formation.9 Early-phase transmission, or biofilm-independent transmission, has been documented to occur as early as 3 hours after infection of the flea but can occur for up to 4 days.10 Historically, the importance of early-phase transmission has been overlooked. Research has shown that it likely is crucial to the epizootic transmission of the plague.10 As a result, the search has begun for genes that contribute to the maintenance of Y pestis in the flea vector during the first 4 days of colonization. It is thought that a key evolutionary development was the selective loss-of-function mutation in a gene essential for the activity of urease, an enzyme that causes acute oral toxicity and mortality in fleas.11,12 The Yersinia murine toxin gene, Ymt, also allows for early survival of Y pestis in the flea midgut by producing a phospholipase D that protects the bacteria from toxic by-products produced during digestion of blood.11,13 In addition, gene products that function in lipid A modification are crucial for the ability of Y pestis to resist the action of cationic antimicrobial peptides it produces, such as cecropin A and polymyxin B.13

Murine typhus, an acute febrile illness caused by Rickettsia typhi, is another disease that can be spread by oriental rat fleas. It has a worldwide distribution. In the United States, R typhi–induced rickettsia mainly is concentrated in suburban areas of Texas and California where it is thought to be mainly spread by Ctenocephalides, but it also is found in Hawaii where spread by X cheopis has been documented.14,15 The most common symptoms of rickettsia include fever, headache, arthralgia, and a characteristic rash that is pruritic and maculopapular, starting on the trunk and spreading peripherally but sparing the palms and soles. This rash occurs about a week after the onset of fever.14Rickettsia felis also has been isolated in the oriental rat flea. However, only a handful of cases of human disease caused by this bacterium have been reported throughout the world, with clinical similarity to murine typhus likely leading to underestimation of disease prevalence.15Bartonella and other species of bacteria also have been documented to be spread by X cheopis.16 Unfortunately, the interactions of X cheopis with these other bacteria are not as well studied as its relationship with Y pestis.

Adverse Reactions

A flea bite itself can cause discomfort. It begins as a punctate hemorrhagic area that develops a surrounding wheal within 30 minutes. Over the course of 1 to 2 days, a delayed reaction occurs and there is a transition to an extremely pruritic, papular lesion. Bites often occur in clusters and can persist for weeks.1

Prevention and Treatment

Control of host animals via extermination and proper sanitation can secondarily reduce the population of X cheopis. Direct pesticide control of the flea population also has been suggested to reduce flea-borne disease. However, insecticides cause a selective pressure on the flea population, leading to populations that are resistant to them. For example, the flea population in Madagascar developed resistance to DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), dieldrin, deltamethrin, and cyfluthrin after their widespread use.17 Further, a recent study revealed resistance of X cheopis populations to alphacypermethrin, lambda-cyhalothrin, and etofenprox, none of which were used in mass vector control, indicating that some cross-resistance mechanism between these and the extensively used insecticides may exist. With the development of widespread resistance to most pesticides, flea control in endemic areas is difficult. Insecticide targeting to fleas on rodents (eg, rodent bait containing insecticide) can allow for more targeted insecticide treatment, limiting the development of resistance.17 Recent development of a maceration protocol used to detect zoonotic pathogens in fleas in the field also will allow management with pesticides to be targeted geographically and temporally where infected vectors are located.18 Research of the interaction between vector, pathogen, and insect microbiome also should continue, as it may allow for development of biopesticides, limiting the use of chemical pesticides all together. The strategy is based on the introduction of microorganisms that can reduce vector lifespan or their ability to transmit pathogens.17

When flea-transmitted diseases do occur, treatment with antibiotics is advised. Early treatment of the plague with effective antibiotics such as streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, or chloramphenicol for a minimum of 10 days is critical for survival. Additionally, patients with bubonic plague should be isolated for at least 2 days after administration of antibiotics, while patients with the pneumonic form should be isolated for 4 days into therapy to prevent the spread of disease. Prophylactic therapy for individuals who come into contact with infected individuals also is advised.4 Patients with murine typhus typically respond to doxycycline, tetracycline, or fluoroquinolones. The few cases of R felis–induced disease have responded to doxycycline. Of note, short courses of treatment of doxycycline are appropriate and safe in young children. The short (3–7 day) nature of the course limits the chances of teeth staining.14

- Bitam I, Dittmar K, Parola P, et al. Flea and flea-borne diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E667-E676.

- Mathison BA, Pritt BS. Laboratory identification of arthropod ectoparasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:48-67.

- Ligon BL. Plague: a review of its history and potential as a biological weapon. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2006;17:161-170.

- Josko D. Yersinia pestis: still a plague in the 21st century. Clin Lab Sci. 2004;17:25-29.

- Plague around the world, 2010–2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016;91:89-93.

- Sullivan K. California confirms first human case of the plague in 5 years: what to know. NBC News website. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/california-confirms-first-human-case-bubonic-plague-5-years-what-n1237306. Published August 19, 2020. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- Hinnebusch BJ, Bland DM, Bosio CF, et al. Comparative ability of Oropsylla and Xenopsylla cheopis fleas to transmit Yersinia pestis by two different mechanisms. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005276.

- Bobrov AG, Kirillina O, Vadyvaloo V, et al. The Yersinia pestis HmsCDE regulatory system is essential for blockage of the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), a classic plague vector. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:947-959.

- Darby C, Ananth SL, Tan L, et al. Identification of gmhA, a Yersina pestis gene required for flea blockage, by using a Caenorhabditis elegans biofilm system. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7236-7242.

- Eisen RJ, Dennis DT, Gage KL. The role of early-phase transmission in the spread of Yersinia pestis. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:1183-1192.

- Carniel E. Subtle genetic modifications transformed an enteropathogen into a flea-borne pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18409-18410.

- Chouikha I, Hinnebusch BJ. Silencing urease: a key evolutionary step that facilitated the adaptation of Yersinia pestis to the flea-borne transmission route. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18709-19714.

- Aoyagi KL, Brooks BD, Bearden SW, et al. LPS modification promotes maintenance of Yersinia pestis in fleas. Microbiology. 2015;161:628-638.

- Civen R, Ngo V. Murine typhus: an unrecognized suburban vectorborne disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:913-918.

- Eremeeva ME, Warashina WR, Sturgeon MM, et al. Rickettsia typhi and R. felis in rat fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis), Oahu, Hawaii. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;14:1613-1615.

- Billeter SA, Gundi VAKB, Rood MP, et al. Molecular detection and identification of Bartonella species in Xenopsylla cheopis fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) collected from Rattus norvecus rats in Los Angeles, California. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7850-7852.

- Miarinjara A, Boyer S. Current perspectives on plague vector control in Madagascar: susceptibility status of Xenopsylla cheopis to 12 insecticides. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004414.

- Harrison GF, Scheirer JL, Melanson VR. Development and validation of an arthropod maceration protocol for zoonotic pathogen detection in mosquitoes and fleas. J Vector Ecol. 2014;40:83-89.

A dult Siphonaptera (fleas) are highly adapted to life on the surface of their hosts. Their small 2- to 10-mm bodies are laterally flattened and wingless. They utilize particularly strong hind legs for jumping up to 150 times their body length and backward-directed spines on their legs and bodies for moving forward through fur, hair, and feathers. Xenopsylla cheopis , the oriental rat flea, lacks pronotal and genal combs and has a mesopleuron divided by internal scleritinization (Figure). These features differentiate the species from its close relatives, Ctenocephalides (cat and dog fleas), which have both sets of combs, as well as Pulex irritans (human flea), which do not have a divided mesopleuron. 1,2

Flea-borne infections are extremely important to public health and are present throughout the world. Further, humidity and warmth are essential for the life cycle of many species of fleas. Predicted global warming likely will increase their distribution, allowing the spread of diseases they carry into previously untouched areas.1 Therefore, it is important to continue to examine species that carry particularly dangerous pathogens, such as X cheopis.