User login

Putting an end to chronic opioid prescriptions

Thanks to Dr. Linn et al for “Tips and tools for safe opioid prescribing” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:280-292), which addressed an important topic: the risks of, and poor evidence for, chronic opioids in noncancer pain.

Pain management is challenging, and it is easy to prescribe opioids from a desire to help. However, we must translate the evidence of chronic opioids’ poor benefit and real harms into practice. No studies show a long-term benefit of opioids for chronic noncancer pain, but they do demonstrate abundant findings of harm. As a family medicine community, we should be practicing at the highest level of evidence and addressing legacy opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain.

Increasing opioid doses for pain only offers short-term benefits and can result in rapid tolerance and withdrawal. We should not be starting people on opioids for knee and back pain. We do not need more ways to initiate opioids or tables on how to dose long-acting opioids—drugs that increase mortality.1 Let’s stop using poorly validated tools like DIRE to ignore the evidence against opioids (validated with 61 retrospective chart reviews; 81% sensitivity, 76% specificity for predicting efficacy of opioids).2,3

A 2018 randomized controlled trial of 240 patients with back, knee, or hip osteoarthritis found opioids were not superior to nonopioid medication for pain-related function at 12 months and had more adverse effects.4 A 2015 systematic review concluded there was insufficient evidence of long-term benefits of opioids but a dose-dependent risk of serious harm.5 Just 1 year of taking low-dose opioids can increase the risk of opioid use disorder by 0.7%, compared with 0.004% with no opioids.5

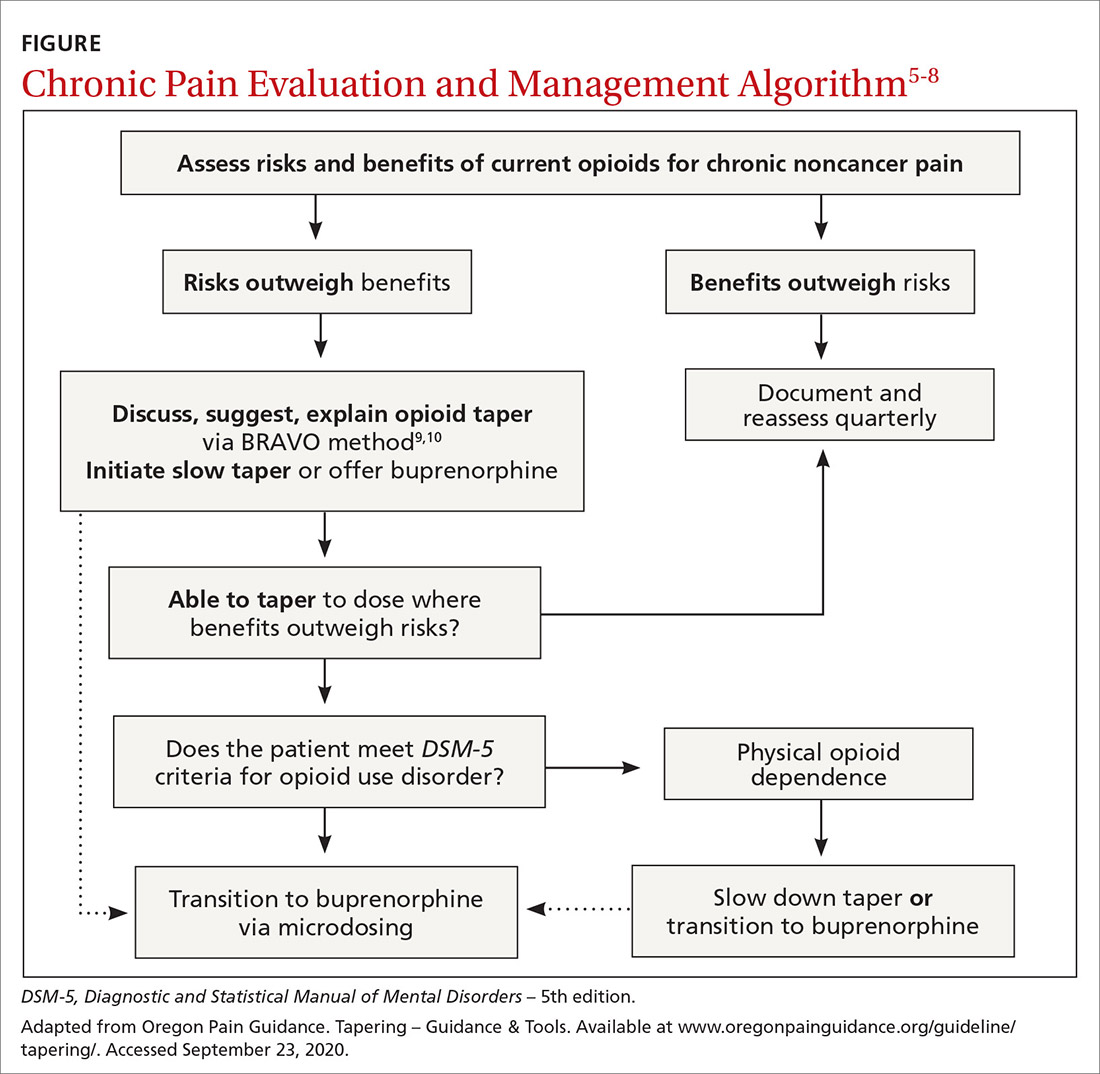

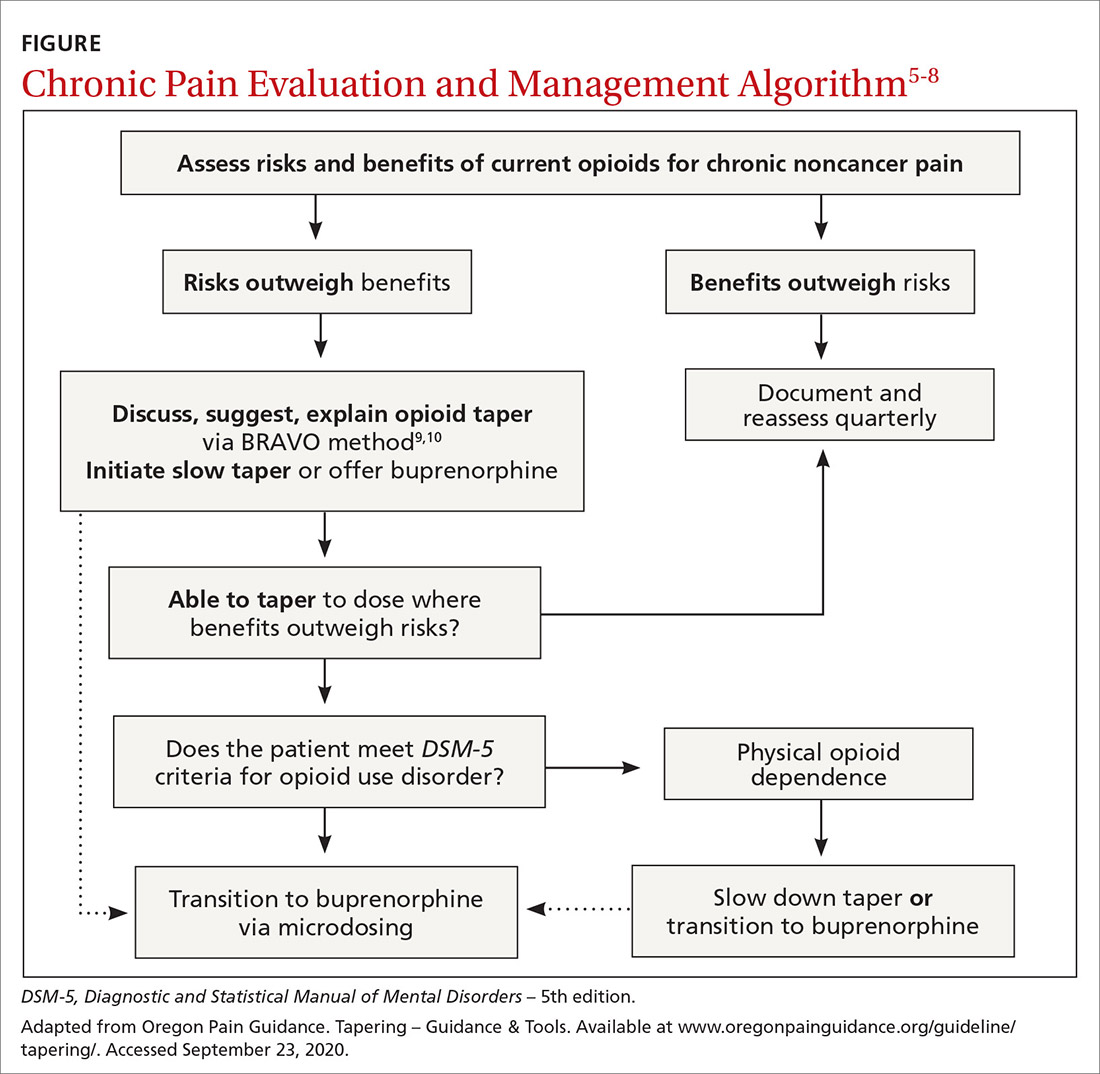

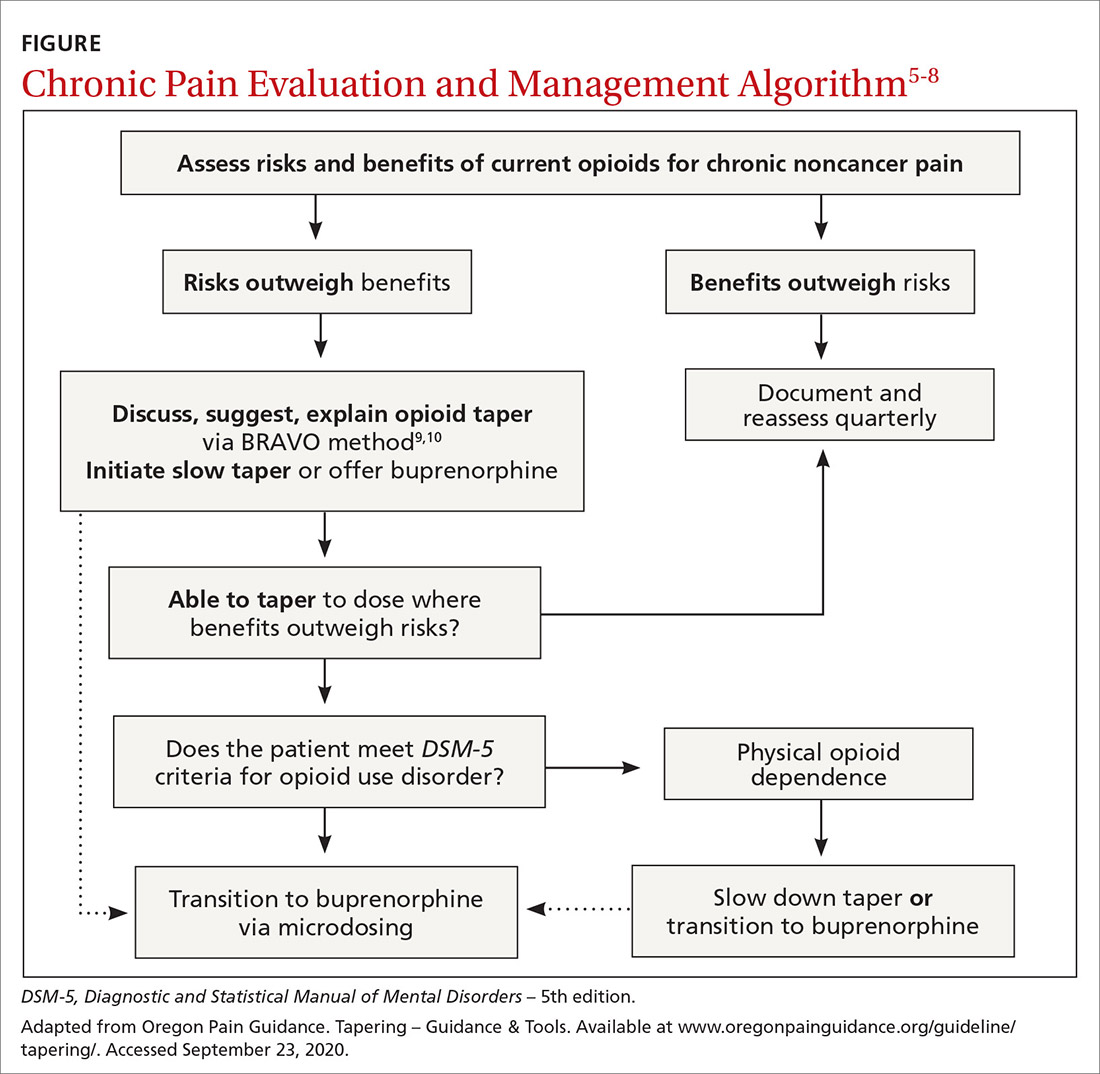

Practical approaches exist. Excellent examples of modern pain care have been developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, and state-level initiatives such as the Oregon Pain Guidance.6-8 All use a similar clinical algorithm (FIGURE). If pain is poorly controlled, a slow medically supervised tapering of opioids is indicated.

It can be challenging to raise the subject of opioid tapering with patients; I use Stanford’s BRAVO method to guide these conversations.9,10 At my facility, we are tapering about 50 legacy opioid patients, and most are surprised to find that their pain is the same or better with reduced to no opioids, with fewer adverse effects. Many are happier on sublingual buprenorphine, a safer opioid analgesic.11 The algorithm shown in the FIGURE and the BRAVO method should be more widely used within our specialty for a safe and patient-centered approach to chronic pain.

Above all, let the patient know that you are with them on this journey to safe pain management. Start the conversation: “I’ve been thinking a lot about your chronic pain and how best to help you with it. Our understanding of what opioids do for pain has changed, and I worry they’re causing more harm than good now. This is a scary thing to talk about, but I’ll be with you every step of the way.”

Matt Perez, MD

Neighborcare Health

Seattle

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315:2415-23.

2. Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:671-681.

3. Brennan MJ. Letter to the editor. J Pain. 2007;8:185.

4. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:872-882.

5. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276-286.

6. Oldfield BJ, Edens EL, Agnoli A, et al. Multimodal treatment options, including rotating to buprenorphine, within a multidisciplinary pain clinic for patients on risky opioid regimens: a quality improvement study. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S38–S45.

7. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics. US Department of Health of Human Services Web site. www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf. October 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. Pain treatment guidelines. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/pain-treatment-guidelines/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. Tapering – BRAVO – a collaborative approach clinical update March 2020. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/guideline/tapering/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

10. How to taper patients off of chronic opioid therapy. Stanford Center for Continuing Medical Education Web site. https://stanford.cloud-cme.com/default.aspx?P=0&EID=20909. Accessed September 29, 2020.

11. Chou R, Ballantyne J, Lembke A, et al. Rethinking opioid dose tapering, prescription opioid dependence, and indications for buprenorphine. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:427-429.

Thanks to Dr. Linn et al for “Tips and tools for safe opioid prescribing” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:280-292), which addressed an important topic: the risks of, and poor evidence for, chronic opioids in noncancer pain.

Pain management is challenging, and it is easy to prescribe opioids from a desire to help. However, we must translate the evidence of chronic opioids’ poor benefit and real harms into practice. No studies show a long-term benefit of opioids for chronic noncancer pain, but they do demonstrate abundant findings of harm. As a family medicine community, we should be practicing at the highest level of evidence and addressing legacy opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain.

Increasing opioid doses for pain only offers short-term benefits and can result in rapid tolerance and withdrawal. We should not be starting people on opioids for knee and back pain. We do not need more ways to initiate opioids or tables on how to dose long-acting opioids—drugs that increase mortality.1 Let’s stop using poorly validated tools like DIRE to ignore the evidence against opioids (validated with 61 retrospective chart reviews; 81% sensitivity, 76% specificity for predicting efficacy of opioids).2,3

A 2018 randomized controlled trial of 240 patients with back, knee, or hip osteoarthritis found opioids were not superior to nonopioid medication for pain-related function at 12 months and had more adverse effects.4 A 2015 systematic review concluded there was insufficient evidence of long-term benefits of opioids but a dose-dependent risk of serious harm.5 Just 1 year of taking low-dose opioids can increase the risk of opioid use disorder by 0.7%, compared with 0.004% with no opioids.5

Practical approaches exist. Excellent examples of modern pain care have been developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, and state-level initiatives such as the Oregon Pain Guidance.6-8 All use a similar clinical algorithm (FIGURE). If pain is poorly controlled, a slow medically supervised tapering of opioids is indicated.

It can be challenging to raise the subject of opioid tapering with patients; I use Stanford’s BRAVO method to guide these conversations.9,10 At my facility, we are tapering about 50 legacy opioid patients, and most are surprised to find that their pain is the same or better with reduced to no opioids, with fewer adverse effects. Many are happier on sublingual buprenorphine, a safer opioid analgesic.11 The algorithm shown in the FIGURE and the BRAVO method should be more widely used within our specialty for a safe and patient-centered approach to chronic pain.

Above all, let the patient know that you are with them on this journey to safe pain management. Start the conversation: “I’ve been thinking a lot about your chronic pain and how best to help you with it. Our understanding of what opioids do for pain has changed, and I worry they’re causing more harm than good now. This is a scary thing to talk about, but I’ll be with you every step of the way.”

Matt Perez, MD

Neighborcare Health

Seattle

Thanks to Dr. Linn et al for “Tips and tools for safe opioid prescribing” (J Fam Pract. 2020;69:280-292), which addressed an important topic: the risks of, and poor evidence for, chronic opioids in noncancer pain.

Pain management is challenging, and it is easy to prescribe opioids from a desire to help. However, we must translate the evidence of chronic opioids’ poor benefit and real harms into practice. No studies show a long-term benefit of opioids for chronic noncancer pain, but they do demonstrate abundant findings of harm. As a family medicine community, we should be practicing at the highest level of evidence and addressing legacy opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain.

Increasing opioid doses for pain only offers short-term benefits and can result in rapid tolerance and withdrawal. We should not be starting people on opioids for knee and back pain. We do not need more ways to initiate opioids or tables on how to dose long-acting opioids—drugs that increase mortality.1 Let’s stop using poorly validated tools like DIRE to ignore the evidence against opioids (validated with 61 retrospective chart reviews; 81% sensitivity, 76% specificity for predicting efficacy of opioids).2,3

A 2018 randomized controlled trial of 240 patients with back, knee, or hip osteoarthritis found opioids were not superior to nonopioid medication for pain-related function at 12 months and had more adverse effects.4 A 2015 systematic review concluded there was insufficient evidence of long-term benefits of opioids but a dose-dependent risk of serious harm.5 Just 1 year of taking low-dose opioids can increase the risk of opioid use disorder by 0.7%, compared with 0.004% with no opioids.5

Practical approaches exist. Excellent examples of modern pain care have been developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services, and state-level initiatives such as the Oregon Pain Guidance.6-8 All use a similar clinical algorithm (FIGURE). If pain is poorly controlled, a slow medically supervised tapering of opioids is indicated.

It can be challenging to raise the subject of opioid tapering with patients; I use Stanford’s BRAVO method to guide these conversations.9,10 At my facility, we are tapering about 50 legacy opioid patients, and most are surprised to find that their pain is the same or better with reduced to no opioids, with fewer adverse effects. Many are happier on sublingual buprenorphine, a safer opioid analgesic.11 The algorithm shown in the FIGURE and the BRAVO method should be more widely used within our specialty for a safe and patient-centered approach to chronic pain.

Above all, let the patient know that you are with them on this journey to safe pain management. Start the conversation: “I’ve been thinking a lot about your chronic pain and how best to help you with it. Our understanding of what opioids do for pain has changed, and I worry they’re causing more harm than good now. This is a scary thing to talk about, but I’ll be with you every step of the way.”

Matt Perez, MD

Neighborcare Health

Seattle

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315:2415-23.

2. Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:671-681.

3. Brennan MJ. Letter to the editor. J Pain. 2007;8:185.

4. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:872-882.

5. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276-286.

6. Oldfield BJ, Edens EL, Agnoli A, et al. Multimodal treatment options, including rotating to buprenorphine, within a multidisciplinary pain clinic for patients on risky opioid regimens: a quality improvement study. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S38–S45.

7. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics. US Department of Health of Human Services Web site. www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf. October 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. Pain treatment guidelines. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/pain-treatment-guidelines/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. Tapering – BRAVO – a collaborative approach clinical update March 2020. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/guideline/tapering/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

10. How to taper patients off of chronic opioid therapy. Stanford Center for Continuing Medical Education Web site. https://stanford.cloud-cme.com/default.aspx?P=0&EID=20909. Accessed September 29, 2020.

11. Chou R, Ballantyne J, Lembke A, et al. Rethinking opioid dose tapering, prescription opioid dependence, and indications for buprenorphine. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:427-429.

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315:2415-23.

2. Belgrade MJ, Schamber CD, Lindgren BR. The DIRE score: predicting outcomes of opioid prescribing for chronic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:671-681.

3. Brennan MJ. Letter to the editor. J Pain. 2007;8:185.

4. Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;319:872-882.

5. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276-286.

6. Oldfield BJ, Edens EL, Agnoli A, et al. Multimodal treatment options, including rotating to buprenorphine, within a multidisciplinary pain clinic for patients on risky opioid regimens: a quality improvement study. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S38–S45.

7. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics. US Department of Health of Human Services Web site. www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf. October 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. Pain treatment guidelines. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/pain-treatment-guidelines/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. Tapering – BRAVO – a collaborative approach clinical update March 2020. Oregon Pain Guidance Web site. www.oregonpainguidance.org/guideline/tapering/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

10. How to taper patients off of chronic opioid therapy. Stanford Center for Continuing Medical Education Web site. https://stanford.cloud-cme.com/default.aspx?P=0&EID=20909. Accessed September 29, 2020.

11. Chou R, Ballantyne J, Lembke A, et al. Rethinking opioid dose tapering, prescription opioid dependence, and indications for buprenorphine. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:427-429.

COVID-19 pandemic amplifies uncertainty for immigrant hospitalists

H1-B visa program needs improvement

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

H1-B visa program needs improvement

H1-B visa program needs improvement

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

Statistics tell the tale of immigrants in the American health care workforce in broad strokes. In an interview, though, one hospitalist shared the particulars of his professional and personal journey since arriving in the United States from India 15 years ago.

Mihir Patel, MD, MPH, FHM, came to the United States in 2005 to complete a Master’s in Public Health. Fifteen years later, he is still waiting for the green card that signifies U.S. permanent residency status. The paperwork for the application, he said, was completed in 2012. Since then, he’s been renewing his H-1B visa every three years, and he has no expectation that anything will change soon.

“If you are from India, which has a significant backlog of green cards – up to 50 years…you just wait forever,” he said. “Many people even die waiting for their green card to arrive.”

Arriving on a student visa, Dr. Patel completed his MPH in 2008 and began an internal medicine residency that same year, holding a J-1 visa for the 3 years of his US residency program.

“Post-residency, I started working in a rural hospital in an underserved area of northeast Tennessee as a hospitalist,” thus completing the 3 years of service in a rural underserved area that’s a requirement for J-1 visa holders, said Dr. Patel. “I loved this rural community hospital so much that I ended up staying there for 6 years. During my work at this rural hospital, I was able to enjoy the autonomy of managing a small ICU, doing both critical care procedures and management of intubated critical patients while working as a hospitalist,” he said. Dr. Patel served as chief of staff at the hospital for two years, and also served on the board of directors for his 400-physician medical group.

“I was a proud member of this rural community – Rogersville,” said Dr. Patel. Although he and his wife, who was completing her hospitalist residency, lived in Johnson City, Tenn., “I did not mind driving 120 miles round trip every day to go to my small-town hospital for 6 years,” he said.

Spending this time in rural Tennessee allowed Dr. Patel to finish the requirements necessary for the Physician National Interest Waiver and submit his application for permanent residency. The waiver, though, doesn’t give him priority status in the waiting list for permanent residency status.

After a stint in northern California to be closer to extended family, the pull of “beautiful northeast Tennesse and the rural community” was too strong, so Dr. Patel and his family moved back to Johnson City in 2018.

Now, Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at Ballad Health System in Johnson City. He is the corporate director of Ballad’s telemedicine program and is now also the medical director of the COVID-19 Strike Team. He co-founded and is president of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Under another H-1B visa, Dr. Patel works part-time from home as a telehospitalist, covering six hospitals in 4 different states.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the H-1B visa comes with constraints. Although Dr. Patel’s 6-year old daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen, Dr. Patel and his wife have to reapply for their visas every 3 years. “If we travel outside the U.S., we have to get our visas stamped. We cannot change jobs easily due to fear of visa denial, especially with the recent political environment,” said Dr. Patel. “It feels like we are essential health care workers but non-essential immigrants.”

Having recently completed a physician executive MBA program, Dr. Patel said he’d like to start a business of his own using Lean health care principles and telemedicine to improve rural health care. “But while on an H-1B I cannot do anything outside my sponsored employment,” he said.

Ideally, health care organizations would have high flexibility in how and where staff are deployed when a surge of COVID-19 patients hits. Dr. Patel made the point that visa restrictions can make this much harder: “During this COVID crisis, this restriction can cause significant negative impact for small rural hospitals, where local physicians are quarantined and available physicians are on a visa who cannot legally work outside their primary facilities – even though they are willing to work,” he said. “One cannot even work using telemedicine in the same health system, if that is not specifically mentioned during H-1B petition filling. More than 15,000 physicians who are struck by the green card backlog are in the same situation all over U.S.,” he added.

These constraints, though, pale before the consequences of a worst-case pandemic scenario for an immigrant family, where the physician – the primary visa-holder – becomes disabled or dies. In this case, dependent family members must self-deport. “In addition, there would not be any disability or Social Security benefits for the physician or dependents, as they are not citizens or green card holders and they cannot legally stay in the US,” noted Dr. Patel. “Any hospitalist working during the COVID-19 pandemic can have this fate due to our high exposure risk.”

Reauthorizing the H1-B visa program

SHM has been advocating to improve the H1-B visa system for years, Dr. Patel said, The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives with bipartisan support, and the Society is advocating for its passage in the Senate.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act (S. 386) simplifies the employment-based immigration system by removing per-country caps, converting the employment-based immigration system into a “first-come, first serve” system that does not discriminate on country of origin. The act will also help alleviate the decades-long green card and permanent residency application backlogs.

Dr. Patel emphasized the importance of action by Congress to reauthorize the physician visa waiver program and expediting physician permanent residency. “This is a crisis and we are all physicians who are ready to serve, regardless of our country of origin. Please let us help this great nation by giving us freedom from visa restrictions and providing security for our families.

“During wartime, all frontline soldiers are naturalized and given citizenship by presidential mandate; this is more than war and we are not asking for citizenship – but at least give us a green card which we have already satisfied all requirements for. If not now, then when?” he asked.

Choose wisely

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

‘Profound human toll’ in excess deaths from COVID-19 calculated in two studies

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intensive surveillance after CRC resection does not improve survival

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.

There were 356 recurrences in patients initially treated for colon cancer. CEA surveillance with or without CT scan was associated with an increased incidence of secondary resection with curative intent. The rate of secondary resection was 66.3% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 59.5% in the CT plus CEA arm, 50.7% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 40.9% with standard imaging and no CEA (P = .0035).

The rates were similar among the 83 patients with recurrence after initial treatment for rectal cancer, but the between-arm differences were not significant. The rate of secondary resection with curative intent was 57.9% in the standard imaging with CEA arm, 47.8% in the CT plus CEA arm, 55% with CT imaging but no CEA, and 42.9% with standard imaging and no CEA.

The research is ongoing, and the team expects to report on secondary outcomes and ancillary studies of circulating tumor DNA, among other things, in 2021.

The study is being funded by the Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive. Dr. Lepage disclosed ties with Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Servier, and AAA. Dr. Price disclosed institutional research funding from Amgen and being an uncompensated adviser to Pierre-Fabre and Merck.

SOURCE: Lepage C et al. ESMO 2020, Abstract 398O.

However, among patients with colon cancer recurrence, those randomized to intensive surveillance more often had a second surgery with curative intent. Even so, there was no overall survival benefit versus standard surveillance in this group.

In short, “none of the follow-up modalities resulted in a difference,” said investigator Come Lepage, MD, PhD, of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon (France).

Dr. Lepage presented these findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020.

Dr. Lepage said the study’s results suggest guidelines that include CT and CEA monitoring should be amended, and the standard surveillance methods should be ultrasound and chest x-ray. Dr. LePage called CEA surveillance “useless” and said CT scans should be performed only in cases of suspected recurrence.

However, study discussant Tim Price, MBBS, DHSc, of the University of Adelaide, noted that both the intensive and standard arms in this study had abdominal imaging every 3 months, be it ultrasound or CT, so even in the standard arms, surveillance “was still fairly aggressive.”

Because of that, the study does not “suggest we should decrease our intensity,” Dr. Price said.

He added that the study’s major finding was that more intensive surveillance led to higher rates of secondary surgery with curative intent, probably because recurrences were caught earlier than they would have been with standard surveillance, when curative surgery was still possible.

Patients in the study were treated during 2009-2015, and that might have also made a difference. “We need to remember that, in 2020, care is very different,” Dr. Price said. This includes increased surgical interventions and options for oligometastatic disease, plus systemic therapies such as pembrolizumab. With modern treatments, detecting recurrences earlier “may well have an impact on survival.”

Perhaps patients would live longer with “earlier diagnosis in today’s setting with more active agents and more aggressive surgery and radiotherapy [e.g., stereotactic ablative radiation therapy],” Dr. Price said in an interview.

Study details

The trial, dubbed PRODIGE 13, was done to bring clarity to the surveillance issue. Intensive follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer, including CT and CEA monitoring, is recommended by various scientific societies, but it’s based mainly on expert opinion. Results of the few clinical trials on the issue have been controversial, Dr. Lepage explained.

PRODIGE 13 included 1,995 subjects with colorectal cancer. About half of patients had stage II disease, and the other half had stage III. Most patients were 75 years or younger at baseline, and there were more men in the study than women. All patients underwent resection with curative intent and had no evidence of residual disease 3 months after surgery. Some patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients were first randomized to no CEA monitoring or CEA monitoring every 3 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for an additional 3 years. Members in both groups were then randomized a second time to either intensive or standard radiologic surveillance.

Surveillance in the standard arm consisted of an abdominal ultrasound every 3 months for the first 3 years, then biannually for an additional 2 years, plus chest x-rays every 6 months for 5 years. Intensive surveillance consisted of CT imaging, including thoracic imaging, alternating with abdominal ultrasound, every 3 months, then biannually for another 2 years.

At baseline, the surveillance groups were well balanced with regard to demographics, primary tumor location, and other factors, but stage III disease was more prevalent among patients randomized to standard radiologic monitoring without CEA.

Results

The median follow up was 6.5 years. There were no significant differences between the surveillance groups with regard to 5-year overall survival (P = .340) or recurrence-free survival (P = .473).

There were no significant differences in recurrence-free or overall survival when patients were stratified by age, sex, stage, CEA at a cut point of 5 mcg/L, and primary tumor characteristics including location, perineural invasion, and occlusion/perforation.