User login

Dual therapy serves as well as triple for most HIV patients

based on a meta-analysis including data from more than 5,000 patients.

Although triple therapy remains the standard of care, the availability of more potent drugs has revived interest in dual and mono therapies, wrote Pisaturo Mariantonietta, MD, of the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy, and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection, the researchers identified 14 articles including 5,205 treatment-naive HIV adults. The studies were published between 2008 and 2020; 13 were randomized, controlled trials.

The dual therapies used in the studies included atazanavir/r plus maraviroc; lopinavir/r plus lamivudine; raltegravir plus darunavir/r; lopinavir/r plus tenofovir, raltegravir, efavirenz, or maraviroc; atazanavir/r plus raltegravir and darunavir/r plus maraviroc; and dolutegravir plus lamivudine.

Overall, no significant differences occurred in the primary endpoint of treatment failure across 10 studies between dual therapy and triple therapy patients based on data at 48 weeks (relative risk 1.20). “The rate of treatment failure did not differ among the two groups when stratifying the patients according to the drug used in the dual regimen,” the researchers said.

Low viral load’s link to treatment failure

Among 2,398 patients with a low HIV viral load (less than 100,000 copies/mL), dual therapy patients were significantly more likely to experience treatment failure than were triple therapy patients (RR, 1.47, P = .007). No differences were noted between dual and triple therapy failure among patients with high HIV viral loads at baseline. Patterns were similar at 96 weeks, but only three studies included 96-week data, the researchers said.

The rate of discontinuation because of adverse events was not significantly different between the groups at 48 weeks.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of different regimens in the dual strategies, some of which are no longer in use, as well as there being insufficient data to fully compare outcomes at 96 weeks, and lack of information on cerebrospinal fluid viral load, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that dual therapy might be considered for HIV-naive patients with a low viral load, they said.

“Further RCTs that will evaluate the efficacy of antiretroviral regimens in use today among difficult-to-treat populations, such as patients with high viral load, including both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis, are needed to address this topic,” they concluded.

Consider range of patient factors when choosing therapies

Conducting the study at this time was important because of the expanding options for treating HIV patients, Donna E. Sweet, MD, an HIV specialist and professor of medicine at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in an interview.

“We now have two single tablet formulations that are dual rather than triple therapy, and as treaters we are all trying to know when to use them,” she explained.

Dr. Sweet said she was not surprised by the study findings, given that well-conducted, randomized, controlled trials allowed the combination therapies to be approved.

Some of the key challenges to identifying the optimal treatment for HIV patients include factoring in the use of concomitant medications that could lead to drug-drug interactions, noted Dr. Sweet, who serves an editorial advisory board member of Internal Medicine News.

The take-home message for clinicians, in her opinion, is that “less drugs may mean less toxicity, but we don’t want to sacrifice efficacy,” she said. “There may be patients who are better suited than others for two vs. three drugs,” Dr. Sweet emphasized.

The next steps for research on the value of dual vs. triple therapy should include longer term efficacy studies, especially in those with lower CD4 counts and higher viral loads, said Dr. Sweet. In addition to factors such as CD4 counts and viral load, the food requirements of certain ART regimens could affect adherence and therefore a clinician decision to use two drugs rather than three, she noted.

Dr. Sweet disclosed past relationships with ViiV, Gilead, Merck, and Janssen on their speakers bureaus, and current advisory roles with Gilead and ViiV.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Mariantonietta and several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including ViiV Healthcare, AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag and Gilead Science, and Merck Sharp & Dohme, but no conflicts in connection with this study.

SOURCE: Mariantonietta P et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.048.

based on a meta-analysis including data from more than 5,000 patients.

Although triple therapy remains the standard of care, the availability of more potent drugs has revived interest in dual and mono therapies, wrote Pisaturo Mariantonietta, MD, of the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy, and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection, the researchers identified 14 articles including 5,205 treatment-naive HIV adults. The studies were published between 2008 and 2020; 13 were randomized, controlled trials.

The dual therapies used in the studies included atazanavir/r plus maraviroc; lopinavir/r plus lamivudine; raltegravir plus darunavir/r; lopinavir/r plus tenofovir, raltegravir, efavirenz, or maraviroc; atazanavir/r plus raltegravir and darunavir/r plus maraviroc; and dolutegravir plus lamivudine.

Overall, no significant differences occurred in the primary endpoint of treatment failure across 10 studies between dual therapy and triple therapy patients based on data at 48 weeks (relative risk 1.20). “The rate of treatment failure did not differ among the two groups when stratifying the patients according to the drug used in the dual regimen,” the researchers said.

Low viral load’s link to treatment failure

Among 2,398 patients with a low HIV viral load (less than 100,000 copies/mL), dual therapy patients were significantly more likely to experience treatment failure than were triple therapy patients (RR, 1.47, P = .007). No differences were noted between dual and triple therapy failure among patients with high HIV viral loads at baseline. Patterns were similar at 96 weeks, but only three studies included 96-week data, the researchers said.

The rate of discontinuation because of adverse events was not significantly different between the groups at 48 weeks.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of different regimens in the dual strategies, some of which are no longer in use, as well as there being insufficient data to fully compare outcomes at 96 weeks, and lack of information on cerebrospinal fluid viral load, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that dual therapy might be considered for HIV-naive patients with a low viral load, they said.

“Further RCTs that will evaluate the efficacy of antiretroviral regimens in use today among difficult-to-treat populations, such as patients with high viral load, including both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis, are needed to address this topic,” they concluded.

Consider range of patient factors when choosing therapies

Conducting the study at this time was important because of the expanding options for treating HIV patients, Donna E. Sweet, MD, an HIV specialist and professor of medicine at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in an interview.

“We now have two single tablet formulations that are dual rather than triple therapy, and as treaters we are all trying to know when to use them,” she explained.

Dr. Sweet said she was not surprised by the study findings, given that well-conducted, randomized, controlled trials allowed the combination therapies to be approved.

Some of the key challenges to identifying the optimal treatment for HIV patients include factoring in the use of concomitant medications that could lead to drug-drug interactions, noted Dr. Sweet, who serves an editorial advisory board member of Internal Medicine News.

The take-home message for clinicians, in her opinion, is that “less drugs may mean less toxicity, but we don’t want to sacrifice efficacy,” she said. “There may be patients who are better suited than others for two vs. three drugs,” Dr. Sweet emphasized.

The next steps for research on the value of dual vs. triple therapy should include longer term efficacy studies, especially in those with lower CD4 counts and higher viral loads, said Dr. Sweet. In addition to factors such as CD4 counts and viral load, the food requirements of certain ART regimens could affect adherence and therefore a clinician decision to use two drugs rather than three, she noted.

Dr. Sweet disclosed past relationships with ViiV, Gilead, Merck, and Janssen on their speakers bureaus, and current advisory roles with Gilead and ViiV.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Mariantonietta and several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including ViiV Healthcare, AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag and Gilead Science, and Merck Sharp & Dohme, but no conflicts in connection with this study.

SOURCE: Mariantonietta P et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.048.

based on a meta-analysis including data from more than 5,000 patients.

Although triple therapy remains the standard of care, the availability of more potent drugs has revived interest in dual and mono therapies, wrote Pisaturo Mariantonietta, MD, of the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy, and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection, the researchers identified 14 articles including 5,205 treatment-naive HIV adults. The studies were published between 2008 and 2020; 13 were randomized, controlled trials.

The dual therapies used in the studies included atazanavir/r plus maraviroc; lopinavir/r plus lamivudine; raltegravir plus darunavir/r; lopinavir/r plus tenofovir, raltegravir, efavirenz, or maraviroc; atazanavir/r plus raltegravir and darunavir/r plus maraviroc; and dolutegravir plus lamivudine.

Overall, no significant differences occurred in the primary endpoint of treatment failure across 10 studies between dual therapy and triple therapy patients based on data at 48 weeks (relative risk 1.20). “The rate of treatment failure did not differ among the two groups when stratifying the patients according to the drug used in the dual regimen,” the researchers said.

Low viral load’s link to treatment failure

Among 2,398 patients with a low HIV viral load (less than 100,000 copies/mL), dual therapy patients were significantly more likely to experience treatment failure than were triple therapy patients (RR, 1.47, P = .007). No differences were noted between dual and triple therapy failure among patients with high HIV viral loads at baseline. Patterns were similar at 96 weeks, but only three studies included 96-week data, the researchers said.

The rate of discontinuation because of adverse events was not significantly different between the groups at 48 weeks.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the use of different regimens in the dual strategies, some of which are no longer in use, as well as there being insufficient data to fully compare outcomes at 96 weeks, and lack of information on cerebrospinal fluid viral load, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that dual therapy might be considered for HIV-naive patients with a low viral load, they said.

“Further RCTs that will evaluate the efficacy of antiretroviral regimens in use today among difficult-to-treat populations, such as patients with high viral load, including both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis, are needed to address this topic,” they concluded.

Consider range of patient factors when choosing therapies

Conducting the study at this time was important because of the expanding options for treating HIV patients, Donna E. Sweet, MD, an HIV specialist and professor of medicine at the University of Kansas, Wichita, said in an interview.

“We now have two single tablet formulations that are dual rather than triple therapy, and as treaters we are all trying to know when to use them,” she explained.

Dr. Sweet said she was not surprised by the study findings, given that well-conducted, randomized, controlled trials allowed the combination therapies to be approved.

Some of the key challenges to identifying the optimal treatment for HIV patients include factoring in the use of concomitant medications that could lead to drug-drug interactions, noted Dr. Sweet, who serves an editorial advisory board member of Internal Medicine News.

The take-home message for clinicians, in her opinion, is that “less drugs may mean less toxicity, but we don’t want to sacrifice efficacy,” she said. “There may be patients who are better suited than others for two vs. three drugs,” Dr. Sweet emphasized.

The next steps for research on the value of dual vs. triple therapy should include longer term efficacy studies, especially in those with lower CD4 counts and higher viral loads, said Dr. Sweet. In addition to factors such as CD4 counts and viral load, the food requirements of certain ART regimens could affect adherence and therefore a clinician decision to use two drugs rather than three, she noted.

Dr. Sweet disclosed past relationships with ViiV, Gilead, Merck, and Janssen on their speakers bureaus, and current advisory roles with Gilead and ViiV.

The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Mariantonietta and several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including ViiV Healthcare, AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag and Gilead Science, and Merck Sharp & Dohme, but no conflicts in connection with this study.

SOURCE: Mariantonietta P et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.048.

FROM CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY AND INFECTION

Early hearing impairment interventions key to kindergarten readiness

Starting early intervention (EI) enrollment before age 6 months in children who are deaf or hard of hearing may have a lasting influence on ensuring kindergarten readiness, Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

The researchers created a comprehensive, longitudinal, population-based database, which linked hearing screening and diagnostic data to that of early intervention data and educational records for 1,746 infants identified with permanent hearing loss who were born between Jan. 1, 2008 and Dec. 31, 2014 The database was established in partnership with the Ohio Departments of Health, Developmental Disabilities and Education, and with the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

Of those, 784 children ranging from preschool to fourth grade were evaluated based on education data available for the 2017 and 2018 school year that had been linked by way of an identifier that flagged students enrolled in EI.

All together, 417 students had kindergarten assessment records, and of those, 385 had Kindergarten Readiness Assessments (KRAs) between 2014 and 2018; 222 (58%) had been enrolled in EI before the age of 6 months. Of those who were enrolled early, the median age of EI enrollment was 3.4 months (2.4-4.3 months) and in those enrolled later, the median age was 9.2 months (7.5-15.4 months).

The importance of EI prior to 6 months

A total of 109 children (28%) receiving services as part of Ohio’s early intervention programs demonstrated kindergarten readiness on their overall KRA scores. The scores revealed that children receiving EI early (34%, n = 75) were more likely to be ready for kindergarten than were those who entered later (21%, n = 34; P = .005). They also were more likely to have on track language and literacy scores (60% vs. 42%, respectively; P = .0006).

Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues noted that factors identified with “an increased odds of being on track included having private insurance and some college education for the mother.” Conversely, factors identified with a decreased likelihood included having a diagnosed disability and bilateral hearing loss.

The researchers cautioned that children transitioned from EI to academic settings will face challenges that may go underrecognized because a school’s focus often is largely on social and academic performance. Thus, working with linked data systems can provide the data to track outcomes that might otherwise be missed, the researchers noted.

Furthermore, they cautioned that even though kindergarten readiness offers some glimpse into future academic success, these measures alone may not be sufficient predictors for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Risk for communication, social, and academic delays persist throughout school so it is important to employ alternative methods of reading instruction in order to “achieve more complex skills (e.g., complex syntax and advanced vocabulary) necessary for reading proficiency,” the researchers said.

Collecting data from public health and education systems posed limitations for the study. In addition, the absence of kindergarten language assessments prevented Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues from better elucidating reasons for kindergarten readiness. Also beyond the scope of the study was the ability to evaluate the effect service types may have had on outcomes.

The next step in the research process is to evaluate the link between outcomes and specific EI parameters, they said. “Our study demonstrates that an integrated data system can address relevant and important topics regarding early academic outcomes (kindergarten readiness and reading levels) among children who received EI. The current findings provide a new context by evaluating later outcomes among children who are deaf or hard of hearing,” they added, noting that more research is needed to grasp how various EI services impact outcomes since enrollment age is a marker of EI exposure.

Early intervention is everyone’s business

In a separate interview, Amy Hardy M.S. CCC-SLP, speech language pathologist and clinical professor at Idaho State University, emphasized the importance of early intervention, citing reports from the National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management, which credits detection and treatment of hearing loss at birth per child to saving $400,000 in special education costs by the time they graduate from high school (https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/newborn-hearing-screening-state-laws.aspx).

Earliest possible hearing detection is and should be a standard of care for infants and children, and the importance of follow up appointments also cannot be understated,” Ms. Hardy said. Perhaps the biggest challenge for professionals involved with early learning is that many children are delayed in receiving follow up appointments for hearing detection, she added. When families fail to receive a follow-up notice or opt not attend the follow-up appointment, this leaves infants that may be deaf or hard of hearing unidentified, she explained, noting that in some states, lack of consistent and stable state funding needed for effective follow-up with these children and families is a factor.

Ms. Hardy urged that anyone who knows an expectant family can tout the importance of early screenings. Even daycare workers have a responsibility to play a role in early hearing detection, she noted.

Although speech language pathologists routinely advocate for early intervention, “it is never too late to work on skills that will assist children in their everyday lives,” she advised.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the Disability Research and Dissemination Center via cooperative agreements with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Meinzen-Derr J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 October. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0557.

Starting early intervention (EI) enrollment before age 6 months in children who are deaf or hard of hearing may have a lasting influence on ensuring kindergarten readiness, Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

The researchers created a comprehensive, longitudinal, population-based database, which linked hearing screening and diagnostic data to that of early intervention data and educational records for 1,746 infants identified with permanent hearing loss who were born between Jan. 1, 2008 and Dec. 31, 2014 The database was established in partnership with the Ohio Departments of Health, Developmental Disabilities and Education, and with the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

Of those, 784 children ranging from preschool to fourth grade were evaluated based on education data available for the 2017 and 2018 school year that had been linked by way of an identifier that flagged students enrolled in EI.

All together, 417 students had kindergarten assessment records, and of those, 385 had Kindergarten Readiness Assessments (KRAs) between 2014 and 2018; 222 (58%) had been enrolled in EI before the age of 6 months. Of those who were enrolled early, the median age of EI enrollment was 3.4 months (2.4-4.3 months) and in those enrolled later, the median age was 9.2 months (7.5-15.4 months).

The importance of EI prior to 6 months

A total of 109 children (28%) receiving services as part of Ohio’s early intervention programs demonstrated kindergarten readiness on their overall KRA scores. The scores revealed that children receiving EI early (34%, n = 75) were more likely to be ready for kindergarten than were those who entered later (21%, n = 34; P = .005). They also were more likely to have on track language and literacy scores (60% vs. 42%, respectively; P = .0006).

Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues noted that factors identified with “an increased odds of being on track included having private insurance and some college education for the mother.” Conversely, factors identified with a decreased likelihood included having a diagnosed disability and bilateral hearing loss.

The researchers cautioned that children transitioned from EI to academic settings will face challenges that may go underrecognized because a school’s focus often is largely on social and academic performance. Thus, working with linked data systems can provide the data to track outcomes that might otherwise be missed, the researchers noted.

Furthermore, they cautioned that even though kindergarten readiness offers some glimpse into future academic success, these measures alone may not be sufficient predictors for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Risk for communication, social, and academic delays persist throughout school so it is important to employ alternative methods of reading instruction in order to “achieve more complex skills (e.g., complex syntax and advanced vocabulary) necessary for reading proficiency,” the researchers said.

Collecting data from public health and education systems posed limitations for the study. In addition, the absence of kindergarten language assessments prevented Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues from better elucidating reasons for kindergarten readiness. Also beyond the scope of the study was the ability to evaluate the effect service types may have had on outcomes.

The next step in the research process is to evaluate the link between outcomes and specific EI parameters, they said. “Our study demonstrates that an integrated data system can address relevant and important topics regarding early academic outcomes (kindergarten readiness and reading levels) among children who received EI. The current findings provide a new context by evaluating later outcomes among children who are deaf or hard of hearing,” they added, noting that more research is needed to grasp how various EI services impact outcomes since enrollment age is a marker of EI exposure.

Early intervention is everyone’s business

In a separate interview, Amy Hardy M.S. CCC-SLP, speech language pathologist and clinical professor at Idaho State University, emphasized the importance of early intervention, citing reports from the National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management, which credits detection and treatment of hearing loss at birth per child to saving $400,000 in special education costs by the time they graduate from high school (https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/newborn-hearing-screening-state-laws.aspx).

Earliest possible hearing detection is and should be a standard of care for infants and children, and the importance of follow up appointments also cannot be understated,” Ms. Hardy said. Perhaps the biggest challenge for professionals involved with early learning is that many children are delayed in receiving follow up appointments for hearing detection, she added. When families fail to receive a follow-up notice or opt not attend the follow-up appointment, this leaves infants that may be deaf or hard of hearing unidentified, she explained, noting that in some states, lack of consistent and stable state funding needed for effective follow-up with these children and families is a factor.

Ms. Hardy urged that anyone who knows an expectant family can tout the importance of early screenings. Even daycare workers have a responsibility to play a role in early hearing detection, she noted.

Although speech language pathologists routinely advocate for early intervention, “it is never too late to work on skills that will assist children in their everyday lives,” she advised.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the Disability Research and Dissemination Center via cooperative agreements with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Meinzen-Derr J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 October. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0557.

Starting early intervention (EI) enrollment before age 6 months in children who are deaf or hard of hearing may have a lasting influence on ensuring kindergarten readiness, Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

The researchers created a comprehensive, longitudinal, population-based database, which linked hearing screening and diagnostic data to that of early intervention data and educational records for 1,746 infants identified with permanent hearing loss who were born between Jan. 1, 2008 and Dec. 31, 2014 The database was established in partnership with the Ohio Departments of Health, Developmental Disabilities and Education, and with the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

Of those, 784 children ranging from preschool to fourth grade were evaluated based on education data available for the 2017 and 2018 school year that had been linked by way of an identifier that flagged students enrolled in EI.

All together, 417 students had kindergarten assessment records, and of those, 385 had Kindergarten Readiness Assessments (KRAs) between 2014 and 2018; 222 (58%) had been enrolled in EI before the age of 6 months. Of those who were enrolled early, the median age of EI enrollment was 3.4 months (2.4-4.3 months) and in those enrolled later, the median age was 9.2 months (7.5-15.4 months).

The importance of EI prior to 6 months

A total of 109 children (28%) receiving services as part of Ohio’s early intervention programs demonstrated kindergarten readiness on their overall KRA scores. The scores revealed that children receiving EI early (34%, n = 75) were more likely to be ready for kindergarten than were those who entered later (21%, n = 34; P = .005). They also were more likely to have on track language and literacy scores (60% vs. 42%, respectively; P = .0006).

Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues noted that factors identified with “an increased odds of being on track included having private insurance and some college education for the mother.” Conversely, factors identified with a decreased likelihood included having a diagnosed disability and bilateral hearing loss.

The researchers cautioned that children transitioned from EI to academic settings will face challenges that may go underrecognized because a school’s focus often is largely on social and academic performance. Thus, working with linked data systems can provide the data to track outcomes that might otherwise be missed, the researchers noted.

Furthermore, they cautioned that even though kindergarten readiness offers some glimpse into future academic success, these measures alone may not be sufficient predictors for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Risk for communication, social, and academic delays persist throughout school so it is important to employ alternative methods of reading instruction in order to “achieve more complex skills (e.g., complex syntax and advanced vocabulary) necessary for reading proficiency,” the researchers said.

Collecting data from public health and education systems posed limitations for the study. In addition, the absence of kindergarten language assessments prevented Dr. Meinzen-Derr and colleagues from better elucidating reasons for kindergarten readiness. Also beyond the scope of the study was the ability to evaluate the effect service types may have had on outcomes.

The next step in the research process is to evaluate the link between outcomes and specific EI parameters, they said. “Our study demonstrates that an integrated data system can address relevant and important topics regarding early academic outcomes (kindergarten readiness and reading levels) among children who received EI. The current findings provide a new context by evaluating later outcomes among children who are deaf or hard of hearing,” they added, noting that more research is needed to grasp how various EI services impact outcomes since enrollment age is a marker of EI exposure.

Early intervention is everyone’s business

In a separate interview, Amy Hardy M.S. CCC-SLP, speech language pathologist and clinical professor at Idaho State University, emphasized the importance of early intervention, citing reports from the National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management, which credits detection and treatment of hearing loss at birth per child to saving $400,000 in special education costs by the time they graduate from high school (https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/newborn-hearing-screening-state-laws.aspx).

Earliest possible hearing detection is and should be a standard of care for infants and children, and the importance of follow up appointments also cannot be understated,” Ms. Hardy said. Perhaps the biggest challenge for professionals involved with early learning is that many children are delayed in receiving follow up appointments for hearing detection, she added. When families fail to receive a follow-up notice or opt not attend the follow-up appointment, this leaves infants that may be deaf or hard of hearing unidentified, she explained, noting that in some states, lack of consistent and stable state funding needed for effective follow-up with these children and families is a factor.

Ms. Hardy urged that anyone who knows an expectant family can tout the importance of early screenings. Even daycare workers have a responsibility to play a role in early hearing detection, she noted.

Although speech language pathologists routinely advocate for early intervention, “it is never too late to work on skills that will assist children in their everyday lives,” she advised.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the Disability Research and Dissemination Center via cooperative agreements with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCE: Meinzen-Derr J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 October. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0557.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Migraine nerve stimulation device now available over the counter

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared Cefaly Dual (Cefaly Technology) which was previously available only by prescription.

Most migraines involve the trigeminal nerve, which can be accessed through the skin on the forehead. Cefaly Dual stimulates the trigeminal nerve using a reusable self-adhesive electrode placed on the forehead.

The device has two settings, ACUTE and PREVENT. In the ACUTE setting, the individual wears the device for 60 minutes at headache onset or during a migraine attack. In the PREVENT setting, the individual wears the device for 20 minutes daily to help prevent future episodes.

At the start of a session, the wearer may feel a slight tingling sensation, which gradually increases and spreads throughout the forehead and the front part of the head. After about 14 minutes, the intensity stabilizes and remains constant until the treatment session is over, according to the company. The device automatically shuts off at the end of each session. It can be used as a stand-alone option or with existing treatment, the company noted.

“For millions of people across the U.S., living with migraine pain and coping with debilitating symptoms are daily realities. It is our mission to provide consumers with increased access to an effective and safe dual modality migraine treatment that is scientifically proven to reduce the number of monthly migraine days by almost half,” Jennifer Trainor McDermott, CEO of Cefaly Technology, said in a news release.

The FDA’s over-the-counter clearance of Cefaly Dual was based on several randomized, controlled clinical trials supporting the efficacy and safety of the device, the company said.

An earlier version of the Cefaly device was approved in the United States in March 2014 to help prevent migraine headache in adults aged 18 or older. The next-generation Cefaly Dual device is “small and sleek in comparison to its older model, which uses bands along the sides to create room for batteries. The newest device is palm-sized, more portable, and uses a battery that is rechargeable via USB,” the company said.

Last spring, the company announced a buyback program where customers in the United States may return their original device and receive a discount of the purchase of the Cefaly Dual device.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared Cefaly Dual (Cefaly Technology) which was previously available only by prescription.

Most migraines involve the trigeminal nerve, which can be accessed through the skin on the forehead. Cefaly Dual stimulates the trigeminal nerve using a reusable self-adhesive electrode placed on the forehead.

The device has two settings, ACUTE and PREVENT. In the ACUTE setting, the individual wears the device for 60 minutes at headache onset or during a migraine attack. In the PREVENT setting, the individual wears the device for 20 minutes daily to help prevent future episodes.

At the start of a session, the wearer may feel a slight tingling sensation, which gradually increases and spreads throughout the forehead and the front part of the head. After about 14 minutes, the intensity stabilizes and remains constant until the treatment session is over, according to the company. The device automatically shuts off at the end of each session. It can be used as a stand-alone option or with existing treatment, the company noted.

“For millions of people across the U.S., living with migraine pain and coping with debilitating symptoms are daily realities. It is our mission to provide consumers with increased access to an effective and safe dual modality migraine treatment that is scientifically proven to reduce the number of monthly migraine days by almost half,” Jennifer Trainor McDermott, CEO of Cefaly Technology, said in a news release.

The FDA’s over-the-counter clearance of Cefaly Dual was based on several randomized, controlled clinical trials supporting the efficacy and safety of the device, the company said.

An earlier version of the Cefaly device was approved in the United States in March 2014 to help prevent migraine headache in adults aged 18 or older. The next-generation Cefaly Dual device is “small and sleek in comparison to its older model, which uses bands along the sides to create room for batteries. The newest device is palm-sized, more portable, and uses a battery that is rechargeable via USB,” the company said.

Last spring, the company announced a buyback program where customers in the United States may return their original device and receive a discount of the purchase of the Cefaly Dual device.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared Cefaly Dual (Cefaly Technology) which was previously available only by prescription.

Most migraines involve the trigeminal nerve, which can be accessed through the skin on the forehead. Cefaly Dual stimulates the trigeminal nerve using a reusable self-adhesive electrode placed on the forehead.

The device has two settings, ACUTE and PREVENT. In the ACUTE setting, the individual wears the device for 60 minutes at headache onset or during a migraine attack. In the PREVENT setting, the individual wears the device for 20 minutes daily to help prevent future episodes.

At the start of a session, the wearer may feel a slight tingling sensation, which gradually increases and spreads throughout the forehead and the front part of the head. After about 14 minutes, the intensity stabilizes and remains constant until the treatment session is over, according to the company. The device automatically shuts off at the end of each session. It can be used as a stand-alone option or with existing treatment, the company noted.

“For millions of people across the U.S., living with migraine pain and coping with debilitating symptoms are daily realities. It is our mission to provide consumers with increased access to an effective and safe dual modality migraine treatment that is scientifically proven to reduce the number of monthly migraine days by almost half,” Jennifer Trainor McDermott, CEO of Cefaly Technology, said in a news release.

The FDA’s over-the-counter clearance of Cefaly Dual was based on several randomized, controlled clinical trials supporting the efficacy and safety of the device, the company said.

An earlier version of the Cefaly device was approved in the United States in March 2014 to help prevent migraine headache in adults aged 18 or older. The next-generation Cefaly Dual device is “small and sleek in comparison to its older model, which uses bands along the sides to create room for batteries. The newest device is palm-sized, more portable, and uses a battery that is rechargeable via USB,” the company said.

Last spring, the company announced a buyback program where customers in the United States may return their original device and receive a discount of the purchase of the Cefaly Dual device.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Being HIV positive increases risk of death from COVID-19

compared with people without HIV.

A comparison of outcomes of people with HIV to people without HIV who were hospitalized in the United Kingdom with COVID-19 from Jan. 17 to June 4 showed that HIV-positive status was associated with a 63% increased risk of day 28 mortality.

This was especially true for HIV+ patients younger than 70 years of age, said Anna Maria Geretti, MD, PhD, professor of virology and infectious diseases, University of Liverpool, England.

The results are from an analysis of data from the ISARIC World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Characterisation Protocol (UK) study, and were presented at the HIV Glasgow annual meeting, held virtually this year because of the pandemic.

“We investigated whether HIV status could be important in COVID-19 outcomes because there was anxiety on the part of our patients, and we wanted to gather some evidence-based information in order to help guide them,” Dr. Geretti said in an interview.

“ISARIC is an international protocol and the UK is one of the nations participating. We applied for access to its very large database, which connects data from all patients who are hospitalized with either known or suspected COVID-19. We wanted to see specifically how the presentation and outcomes of patients with HIV compared with the rest of the population without HIV. It afforded us an ideal opportunity to start to answer this question, and this is our first analysis in what will be an ongoing process. Importantly, we showed that there is a need to really look more carefully at the population with HIV,” she said.

Out of a total of 47,539 patients in the database, 115 (0.24%) had confirmed HIV-positive status, and 103 of those 115, or 89.6%, had a record of being on antiretroviral therapy.

On admission, the patients with HIV were younger, with a median age of 55 compared with 74 for patients without HIV (P < .001). They also had a higher prevalence of obesity, moderate to severe liver disease, higher lymphocyte counts and C-reactive protein, as well as more systemic symptoms.

There were no differences in respiratory rate, need for oxygen, or prevalence of chest infiltrates.

The cumulative incidence of mortality at day 28 was 25.2% in HIV-positive patients compared with 32.1% in HIV-negative patients (P = .12).

But when the researchers looked more closely, they noticed that the mortality rate was actually higher in younger HIV+ patients compared with HIV-negative patients.

Stratified by age, 28-day mortality was significantly higher in HIV+ patients aged <50 years (P =.004); and those aged 50 to 59 years (P = .05).

“So below the age of 70, the risk of mortality was double in people with HIV. The people with HIV who died often had diabetes with complications and also more frequent obesity, but this was not the only explanation,” Dr. Geretti said. “There is something to do with the HIV status per se.”

Next steps will be to expand the data set and repeat the analysis with an additional 100 patients “at least” she said.

The researchers also hope to zero in on what about being HIV+ is increasing the mortality risk from COVID-19.

“Right now we need greater numbers and we hope that the research community will be stimulated to take a closer look at this information, and merge other data so that we can strengthen confidence in the data and tease out what factors are causing this increased risk for mortality,” Dr. Geretti said.

She also emphasized that all patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 should be asked about their HIV status.

“It is important that the HIV status be recorded if we want to increase our ability to understand how HIV impacts survival,” she stressed. “In our experience we found that most of the hospital records were not doing that. Since HIV+ patients seem to be at increased risk, HIV status should be factored into the clinical management. Ask patients if they are HIV+, and if it is not known, then do a test. That would be good practice.”

Dr. Geretti reported no relevant financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health Research, the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, the Department for International Development, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with people without HIV.

A comparison of outcomes of people with HIV to people without HIV who were hospitalized in the United Kingdom with COVID-19 from Jan. 17 to June 4 showed that HIV-positive status was associated with a 63% increased risk of day 28 mortality.

This was especially true for HIV+ patients younger than 70 years of age, said Anna Maria Geretti, MD, PhD, professor of virology and infectious diseases, University of Liverpool, England.

The results are from an analysis of data from the ISARIC World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Characterisation Protocol (UK) study, and were presented at the HIV Glasgow annual meeting, held virtually this year because of the pandemic.

“We investigated whether HIV status could be important in COVID-19 outcomes because there was anxiety on the part of our patients, and we wanted to gather some evidence-based information in order to help guide them,” Dr. Geretti said in an interview.

“ISARIC is an international protocol and the UK is one of the nations participating. We applied for access to its very large database, which connects data from all patients who are hospitalized with either known or suspected COVID-19. We wanted to see specifically how the presentation and outcomes of patients with HIV compared with the rest of the population without HIV. It afforded us an ideal opportunity to start to answer this question, and this is our first analysis in what will be an ongoing process. Importantly, we showed that there is a need to really look more carefully at the population with HIV,” she said.

Out of a total of 47,539 patients in the database, 115 (0.24%) had confirmed HIV-positive status, and 103 of those 115, or 89.6%, had a record of being on antiretroviral therapy.

On admission, the patients with HIV were younger, with a median age of 55 compared with 74 for patients without HIV (P < .001). They also had a higher prevalence of obesity, moderate to severe liver disease, higher lymphocyte counts and C-reactive protein, as well as more systemic symptoms.

There were no differences in respiratory rate, need for oxygen, or prevalence of chest infiltrates.

The cumulative incidence of mortality at day 28 was 25.2% in HIV-positive patients compared with 32.1% in HIV-negative patients (P = .12).

But when the researchers looked more closely, they noticed that the mortality rate was actually higher in younger HIV+ patients compared with HIV-negative patients.

Stratified by age, 28-day mortality was significantly higher in HIV+ patients aged <50 years (P =.004); and those aged 50 to 59 years (P = .05).

“So below the age of 70, the risk of mortality was double in people with HIV. The people with HIV who died often had diabetes with complications and also more frequent obesity, but this was not the only explanation,” Dr. Geretti said. “There is something to do with the HIV status per se.”

Next steps will be to expand the data set and repeat the analysis with an additional 100 patients “at least” she said.

The researchers also hope to zero in on what about being HIV+ is increasing the mortality risk from COVID-19.

“Right now we need greater numbers and we hope that the research community will be stimulated to take a closer look at this information, and merge other data so that we can strengthen confidence in the data and tease out what factors are causing this increased risk for mortality,” Dr. Geretti said.

She also emphasized that all patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 should be asked about their HIV status.

“It is important that the HIV status be recorded if we want to increase our ability to understand how HIV impacts survival,” she stressed. “In our experience we found that most of the hospital records were not doing that. Since HIV+ patients seem to be at increased risk, HIV status should be factored into the clinical management. Ask patients if they are HIV+, and if it is not known, then do a test. That would be good practice.”

Dr. Geretti reported no relevant financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health Research, the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, the Department for International Development, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with people without HIV.

A comparison of outcomes of people with HIV to people without HIV who were hospitalized in the United Kingdom with COVID-19 from Jan. 17 to June 4 showed that HIV-positive status was associated with a 63% increased risk of day 28 mortality.

This was especially true for HIV+ patients younger than 70 years of age, said Anna Maria Geretti, MD, PhD, professor of virology and infectious diseases, University of Liverpool, England.

The results are from an analysis of data from the ISARIC World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Characterisation Protocol (UK) study, and were presented at the HIV Glasgow annual meeting, held virtually this year because of the pandemic.

“We investigated whether HIV status could be important in COVID-19 outcomes because there was anxiety on the part of our patients, and we wanted to gather some evidence-based information in order to help guide them,” Dr. Geretti said in an interview.

“ISARIC is an international protocol and the UK is one of the nations participating. We applied for access to its very large database, which connects data from all patients who are hospitalized with either known or suspected COVID-19. We wanted to see specifically how the presentation and outcomes of patients with HIV compared with the rest of the population without HIV. It afforded us an ideal opportunity to start to answer this question, and this is our first analysis in what will be an ongoing process. Importantly, we showed that there is a need to really look more carefully at the population with HIV,” she said.

Out of a total of 47,539 patients in the database, 115 (0.24%) had confirmed HIV-positive status, and 103 of those 115, or 89.6%, had a record of being on antiretroviral therapy.

On admission, the patients with HIV were younger, with a median age of 55 compared with 74 for patients without HIV (P < .001). They also had a higher prevalence of obesity, moderate to severe liver disease, higher lymphocyte counts and C-reactive protein, as well as more systemic symptoms.

There were no differences in respiratory rate, need for oxygen, or prevalence of chest infiltrates.

The cumulative incidence of mortality at day 28 was 25.2% in HIV-positive patients compared with 32.1% in HIV-negative patients (P = .12).

But when the researchers looked more closely, they noticed that the mortality rate was actually higher in younger HIV+ patients compared with HIV-negative patients.

Stratified by age, 28-day mortality was significantly higher in HIV+ patients aged <50 years (P =.004); and those aged 50 to 59 years (P = .05).

“So below the age of 70, the risk of mortality was double in people with HIV. The people with HIV who died often had diabetes with complications and also more frequent obesity, but this was not the only explanation,” Dr. Geretti said. “There is something to do with the HIV status per se.”

Next steps will be to expand the data set and repeat the analysis with an additional 100 patients “at least” she said.

The researchers also hope to zero in on what about being HIV+ is increasing the mortality risk from COVID-19.

“Right now we need greater numbers and we hope that the research community will be stimulated to take a closer look at this information, and merge other data so that we can strengthen confidence in the data and tease out what factors are causing this increased risk for mortality,” Dr. Geretti said.

She also emphasized that all patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 should be asked about their HIV status.

“It is important that the HIV status be recorded if we want to increase our ability to understand how HIV impacts survival,” she stressed. “In our experience we found that most of the hospital records were not doing that. Since HIV+ patients seem to be at increased risk, HIV status should be factored into the clinical management. Ask patients if they are HIV+, and if it is not known, then do a test. That would be good practice.”

Dr. Geretti reported no relevant financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health Research, the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, the Department for International Development, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Switch to integrase inhibitor regimen safe and effective

data from a randomized trial indicate.

Among 212 women with successful HIV virologic suppression following 48 weeks of treatment with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (ATV/r +TDF), among those who were switched to continued therapy with an integrase inhibitor–based regimen of elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (E/C/F/TAF), mean increases in lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) were greater and renal function was improved compared with patients who were maintained with ATV/r + TDF, reported Monica Thormann, MD, from Salvador B. Gautier Hospital in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and colleagues at the HIV Glasgow drug therapy meeting, which was held online in 2020.

Although the E/C/F/TAF regimen was associated with a significantly greater increase in lipids, there was no significant change in the total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio.

The patients in the study had previously participated in a blinded randomized trial comparing the integrase inhibitor combination plus TDF with ATV/r + TDF in treatment-naive women.

In the current study, patients were randomly assigned in a 3:1 ratio to maintenance with either E/C/F/TAF (159 patients) or ATV/r + TDF (53 patients).

Forty-eight weeks after the switch, virologic suppression (to fewer than 50 copies/mL) was maintained among 94.3% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen, compared with 86.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen. Virologic failure was seen in 1.9% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen and in 3.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen.

In addition, virologic suppression below 20 c/mL at week 48 was more common among women maintained on E/C/F/TAF, at 84.9% vs 71.7% (P = .041). No treatment-emergent resistance was seen with either regimen.

As noted, there were higher mean percentage increases in BMD in the E/C/F/TAF group for both total hip and lumbar spine, but only the latter measure improved significantly in comparison with patients treated with ATV/r + TDF (2.82% vs 0%, P < .001).

Markers of renal tubule damage, including the beta-2 microglobulin to creatinine ratio and the rentinol-binding protein to creatinine ratio, were significantly improved with the integrase inhibitor regimen.

Increases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were 27 vs 5 mg/dL, 16 vs 8 mg/dL, and 5 vs 0 mg/dL in each case comparing the integrase inhibitor–based regimen to the protease inhibitor–based regimen. All of those comparisons were statistically significant.

As noted, however, the total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio was not significantly different between the treatment arms. The rate or initiation of lipid-modifying agents was 1.3% in the E/C/F/TAF group vs 0 in the ATV/r + TDF group, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“These data demonstrate that women who switch to an integrase inhibitor + TAF‐based regimen maintain high levels of virologic suppression with improvement in BMD and renal function biomarkers, as compared with those remaining on their ritonavir boosted atazanavir + TDF‐based regimen,” the authors wrote.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

data from a randomized trial indicate.

Among 212 women with successful HIV virologic suppression following 48 weeks of treatment with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (ATV/r +TDF), among those who were switched to continued therapy with an integrase inhibitor–based regimen of elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (E/C/F/TAF), mean increases in lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) were greater and renal function was improved compared with patients who were maintained with ATV/r + TDF, reported Monica Thormann, MD, from Salvador B. Gautier Hospital in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and colleagues at the HIV Glasgow drug therapy meeting, which was held online in 2020.

Although the E/C/F/TAF regimen was associated with a significantly greater increase in lipids, there was no significant change in the total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio.

The patients in the study had previously participated in a blinded randomized trial comparing the integrase inhibitor combination plus TDF with ATV/r + TDF in treatment-naive women.

In the current study, patients were randomly assigned in a 3:1 ratio to maintenance with either E/C/F/TAF (159 patients) or ATV/r + TDF (53 patients).

Forty-eight weeks after the switch, virologic suppression (to fewer than 50 copies/mL) was maintained among 94.3% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen, compared with 86.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen. Virologic failure was seen in 1.9% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen and in 3.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen.

In addition, virologic suppression below 20 c/mL at week 48 was more common among women maintained on E/C/F/TAF, at 84.9% vs 71.7% (P = .041). No treatment-emergent resistance was seen with either regimen.

As noted, there were higher mean percentage increases in BMD in the E/C/F/TAF group for both total hip and lumbar spine, but only the latter measure improved significantly in comparison with patients treated with ATV/r + TDF (2.82% vs 0%, P < .001).

Markers of renal tubule damage, including the beta-2 microglobulin to creatinine ratio and the rentinol-binding protein to creatinine ratio, were significantly improved with the integrase inhibitor regimen.

Increases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were 27 vs 5 mg/dL, 16 vs 8 mg/dL, and 5 vs 0 mg/dL in each case comparing the integrase inhibitor–based regimen to the protease inhibitor–based regimen. All of those comparisons were statistically significant.

As noted, however, the total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio was not significantly different between the treatment arms. The rate or initiation of lipid-modifying agents was 1.3% in the E/C/F/TAF group vs 0 in the ATV/r + TDF group, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“These data demonstrate that women who switch to an integrase inhibitor + TAF‐based regimen maintain high levels of virologic suppression with improvement in BMD and renal function biomarkers, as compared with those remaining on their ritonavir boosted atazanavir + TDF‐based regimen,” the authors wrote.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

data from a randomized trial indicate.

Among 212 women with successful HIV virologic suppression following 48 weeks of treatment with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (ATV/r +TDF), among those who were switched to continued therapy with an integrase inhibitor–based regimen of elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide (E/C/F/TAF), mean increases in lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) were greater and renal function was improved compared with patients who were maintained with ATV/r + TDF, reported Monica Thormann, MD, from Salvador B. Gautier Hospital in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and colleagues at the HIV Glasgow drug therapy meeting, which was held online in 2020.

Although the E/C/F/TAF regimen was associated with a significantly greater increase in lipids, there was no significant change in the total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio.

The patients in the study had previously participated in a blinded randomized trial comparing the integrase inhibitor combination plus TDF with ATV/r + TDF in treatment-naive women.

In the current study, patients were randomly assigned in a 3:1 ratio to maintenance with either E/C/F/TAF (159 patients) or ATV/r + TDF (53 patients).

Forty-eight weeks after the switch, virologic suppression (to fewer than 50 copies/mL) was maintained among 94.3% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen, compared with 86.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen. Virologic failure was seen in 1.9% of those on the integrase inhibitor–based regimen and in 3.8% of those on the protease inhibitor–based regimen.

In addition, virologic suppression below 20 c/mL at week 48 was more common among women maintained on E/C/F/TAF, at 84.9% vs 71.7% (P = .041). No treatment-emergent resistance was seen with either regimen.

As noted, there were higher mean percentage increases in BMD in the E/C/F/TAF group for both total hip and lumbar spine, but only the latter measure improved significantly in comparison with patients treated with ATV/r + TDF (2.82% vs 0%, P < .001).

Markers of renal tubule damage, including the beta-2 microglobulin to creatinine ratio and the rentinol-binding protein to creatinine ratio, were significantly improved with the integrase inhibitor regimen.

Increases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were 27 vs 5 mg/dL, 16 vs 8 mg/dL, and 5 vs 0 mg/dL in each case comparing the integrase inhibitor–based regimen to the protease inhibitor–based regimen. All of those comparisons were statistically significant.

As noted, however, the total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio was not significantly different between the treatment arms. The rate or initiation of lipid-modifying agents was 1.3% in the E/C/F/TAF group vs 0 in the ATV/r + TDF group, but this difference was not statistically significant.

“These data demonstrate that women who switch to an integrase inhibitor + TAF‐based regimen maintain high levels of virologic suppression with improvement in BMD and renal function biomarkers, as compared with those remaining on their ritonavir boosted atazanavir + TDF‐based regimen,” the authors wrote.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Delayed cancer screening could cause increase in deaths, study says

Delays in colorectal cancer screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to higher rates of advanced-stage cancer and death, according to a new study.

When compared with a delay of less than three months, the longer delay seen this year may result in an 11.9% increase in death rates.

“Across the globe, health care systems are facing serious difficulties while dealing with COVID-19, and it is imperative that support is given to the public and patients throughout the crisis, including for high-impact diseases such as colorectal cancer,” Luigi Ricciardiello, the lead study author and a professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, said in a statement.

Ricciardiello and colleagues presented their research on Monday at UEG Week Virtual 2020, an international conference for gastroenterologists. The study will be published in the UEG Journal .

The researchers created a model to forecast the effects of delayed cancer screening during 2020. A “moderate” delay of 7-12 months caused a 3% increase in advanced-stage colon cancer, and a long delay of more than 12 months caused a 7% increase in advanced cancer.

Based on a survival rate of 5 years for stage 3 or stage 4 colorectal cancer, the death rate would increase nearly 12% when screening is delayed for more than a year, as compared with less than three months of delay.

The research team found similar results when forecasting advanced-stage cancer and deaths earlier this year. In a paper published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology in early September, they projected that deaths could increase 12% if screening is delayed for more than a year.

Throughout the pandemic, screening programs have been delayed in many countries, particularly across Europe.

“Healthcare authorities need to act urgently on how they reorganise activities during COVID-19, without compromising the diagnosis of other high-impact diseases like this research shows,” Ricciardiello said.

United European Gastroenterology, a professional medical organization for digestive health specialists, has called for policymakers to implement colon cancer screening programs across the European Union. Annually, more than 375,000 new cases are diagnosed across the EU, and more than 170,000 people die from colorectal cancer, according to a UEG report.

“Early-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer is crucial — it’s far easier to treat and enhances optimal patient outcomes,” Ricciardiello said. “It is therefore essential that vital diagnosis tools, like screening programmes, continue and help to prevent mortality rates from rising even further.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Delays in colorectal cancer screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to higher rates of advanced-stage cancer and death, according to a new study.

When compared with a delay of less than three months, the longer delay seen this year may result in an 11.9% increase in death rates.

“Across the globe, health care systems are facing serious difficulties while dealing with COVID-19, and it is imperative that support is given to the public and patients throughout the crisis, including for high-impact diseases such as colorectal cancer,” Luigi Ricciardiello, the lead study author and a professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, said in a statement.

Ricciardiello and colleagues presented their research on Monday at UEG Week Virtual 2020, an international conference for gastroenterologists. The study will be published in the UEG Journal .

The researchers created a model to forecast the effects of delayed cancer screening during 2020. A “moderate” delay of 7-12 months caused a 3% increase in advanced-stage colon cancer, and a long delay of more than 12 months caused a 7% increase in advanced cancer.

Based on a survival rate of 5 years for stage 3 or stage 4 colorectal cancer, the death rate would increase nearly 12% when screening is delayed for more than a year, as compared with less than three months of delay.

The research team found similar results when forecasting advanced-stage cancer and deaths earlier this year. In a paper published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology in early September, they projected that deaths could increase 12% if screening is delayed for more than a year.

Throughout the pandemic, screening programs have been delayed in many countries, particularly across Europe.

“Healthcare authorities need to act urgently on how they reorganise activities during COVID-19, without compromising the diagnosis of other high-impact diseases like this research shows,” Ricciardiello said.

United European Gastroenterology, a professional medical organization for digestive health specialists, has called for policymakers to implement colon cancer screening programs across the European Union. Annually, more than 375,000 new cases are diagnosed across the EU, and more than 170,000 people die from colorectal cancer, according to a UEG report.

“Early-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer is crucial — it’s far easier to treat and enhances optimal patient outcomes,” Ricciardiello said. “It is therefore essential that vital diagnosis tools, like screening programmes, continue and help to prevent mortality rates from rising even further.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Delays in colorectal cancer screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to higher rates of advanced-stage cancer and death, according to a new study.

When compared with a delay of less than three months, the longer delay seen this year may result in an 11.9% increase in death rates.

“Across the globe, health care systems are facing serious difficulties while dealing with COVID-19, and it is imperative that support is given to the public and patients throughout the crisis, including for high-impact diseases such as colorectal cancer,” Luigi Ricciardiello, the lead study author and a professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, said in a statement.

Ricciardiello and colleagues presented their research on Monday at UEG Week Virtual 2020, an international conference for gastroenterologists. The study will be published in the UEG Journal .

The researchers created a model to forecast the effects of delayed cancer screening during 2020. A “moderate” delay of 7-12 months caused a 3% increase in advanced-stage colon cancer, and a long delay of more than 12 months caused a 7% increase in advanced cancer.

Based on a survival rate of 5 years for stage 3 or stage 4 colorectal cancer, the death rate would increase nearly 12% when screening is delayed for more than a year, as compared with less than three months of delay.

The research team found similar results when forecasting advanced-stage cancer and deaths earlier this year. In a paper published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology in early September, they projected that deaths could increase 12% if screening is delayed for more than a year.

Throughout the pandemic, screening programs have been delayed in many countries, particularly across Europe.

“Healthcare authorities need to act urgently on how they reorganise activities during COVID-19, without compromising the diagnosis of other high-impact diseases like this research shows,” Ricciardiello said.

United European Gastroenterology, a professional medical organization for digestive health specialists, has called for policymakers to implement colon cancer screening programs across the European Union. Annually, more than 375,000 new cases are diagnosed across the EU, and more than 170,000 people die from colorectal cancer, according to a UEG report.

“Early-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer is crucial — it’s far easier to treat and enhances optimal patient outcomes,” Ricciardiello said. “It is therefore essential that vital diagnosis tools, like screening programmes, continue and help to prevent mortality rates from rising even further.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low back pain in youth: Recognizing red flags

Low back pain in not uncommon in children and adolescents.1-3 Although the prevalence of low back pain in children < 7 years is low, it increases with age, with studies reporting lifetime prevalence at age 12 years between 16% and 18% and rates as high as 66% by 16 years of age.4,5 Although children and adolescents usually have pain that is transient and benign without a defined cause, structural causes of low back pain should be considered in school-aged children with pain that persists for > 3 to 6 weeks. 4 The most common structural causes of adolescent low back pain are reviewed here.

Etiology: A mixed bag

Back pain in school-aged children is most commonly due to muscular strain, overuse, or poor posture. The pain is often transient in nature and responds to rest and postural education.4,6 A herniated disc is an uncommon finding in younger school-aged children, but incidence increases slightly among older adolescents, particularly those who are active in collision sports and/or weight-lifting.7,8 Pain caused by a herniated disc often radiates along the distribution of the sciatic nerve and worsens during lumbar flexion.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are important causes of back pain in children. Spondylolysis is defined as a defect or abnormality of the pars interarticularis and surrounding lamina and pedicle. Spondylolisthesis, which is less common, is defined as the translation or “slippage” of one vertebral segment in relation to the next caudal segment. These conditions commonly occur as a result of repetitive stress.

In a prospective study of adolescents < 19 years with low back pain for > 2 weeks, the prevalence of spondylolysis was 39.7%.9 Adolescent athletes with symptomatic low back pain are more likely to have spondylolysis than nonathletes (32% vs 2%, respectively).2,10 Pain is often made worse by extension of the spine. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis can be congenital or acquired, and both can be asymptomatic. Children and teens who are athletes are at higher risk for symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.10-12 This is especially true for those involved in gymnastics, dance, football, and/or volleyball, where a repetitive load is placed onto an extended spine.

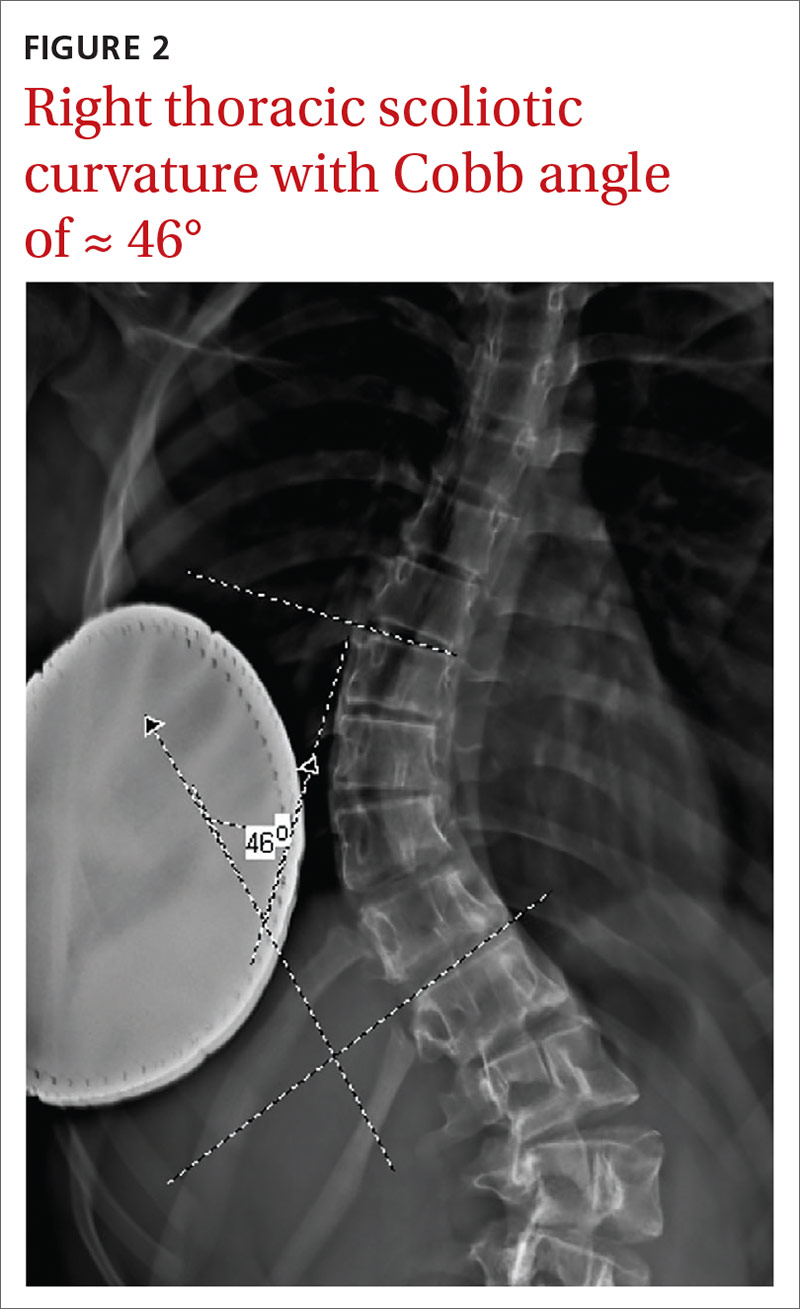

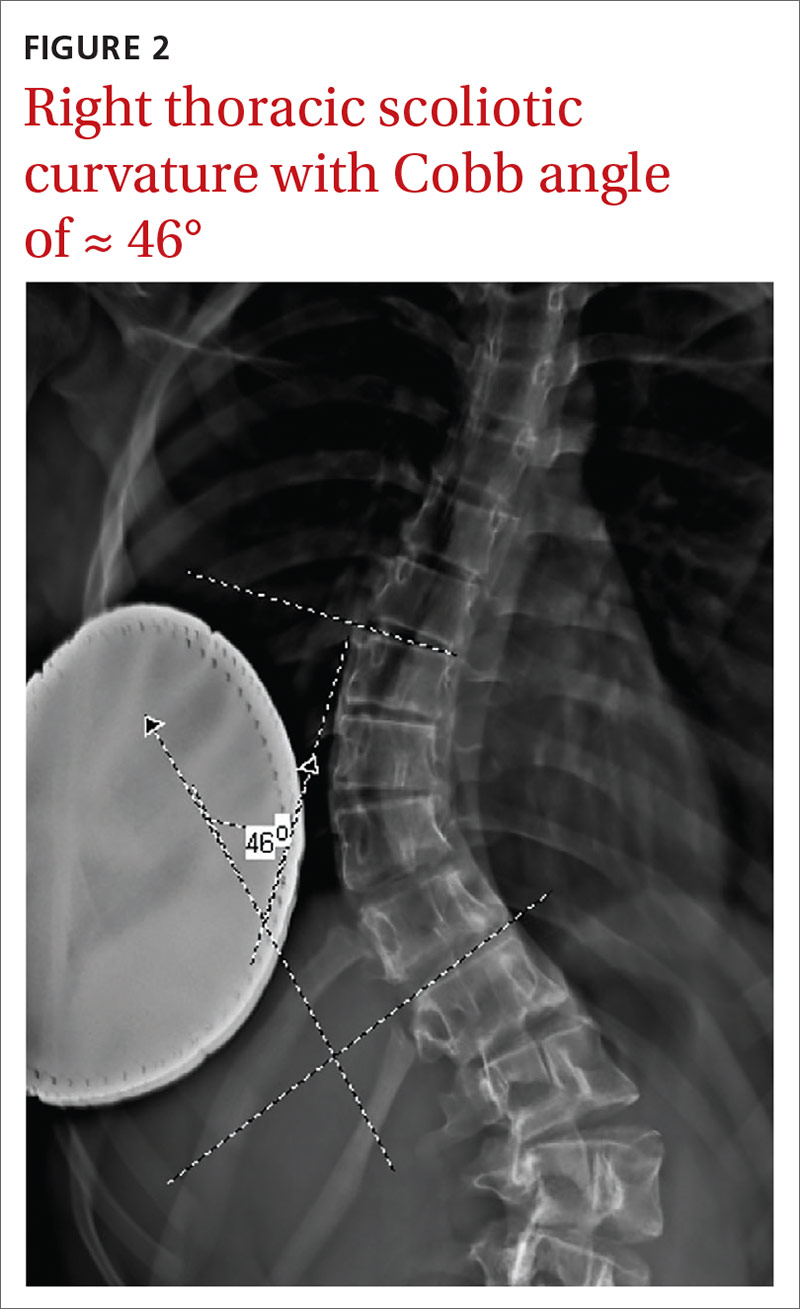

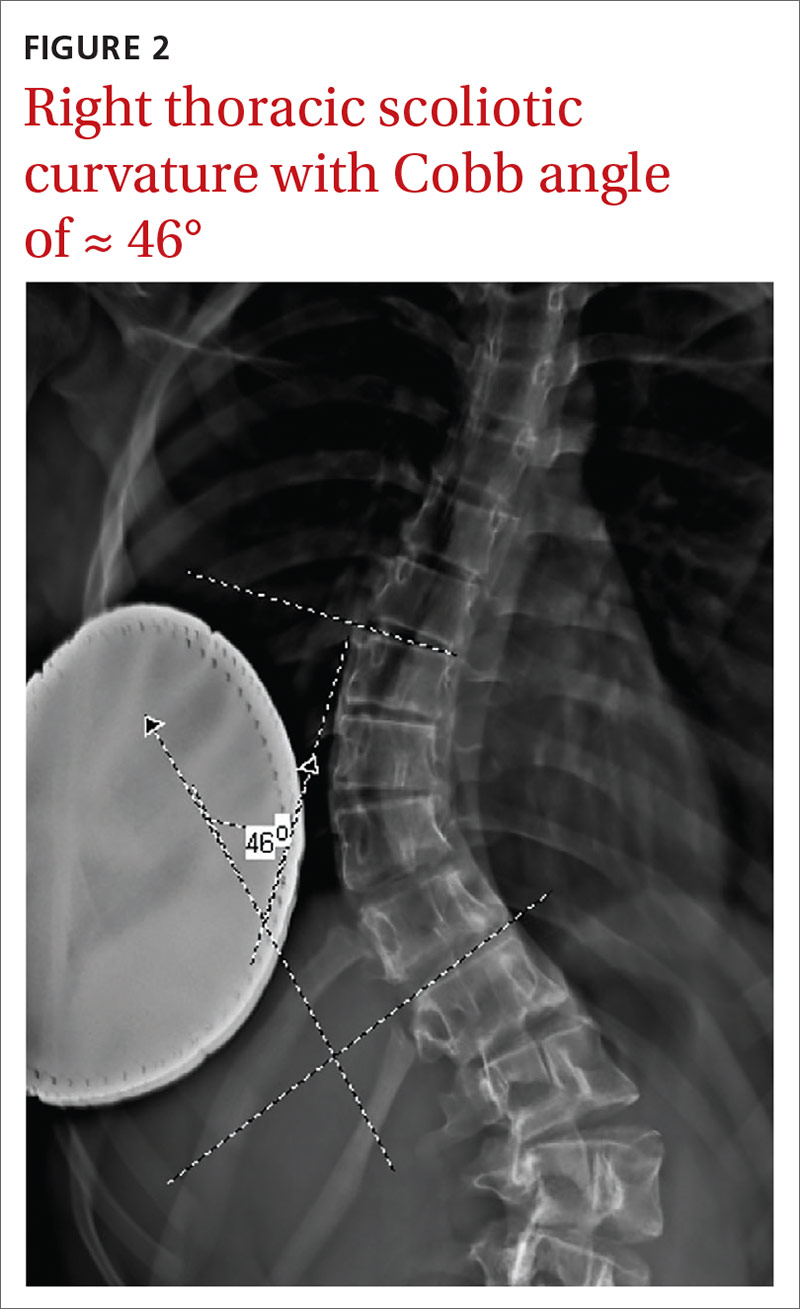

Idiopathic scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine that usually develops during adolescence and worsens with growth. Historically, painful scoliosis was considered rare, but more recently researchers determined that children with scoliosis have a higher rate of pain compared to their peers.13,14 School-aged children with scoliosis were found to be at 2 times the risk of low back pain compared to those without scoliosis.13 It is important to identify scoliosis in adolescents so that progression can be monitored.

Screening for scoliosis in primary care is somewhat controversial. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finds insufficient evidence for screening asymptomatic adolescents for scoliosis.15 This recommendation is based on the fact that there is little evidence on the effect of screening on long-term outcomes. Screening may also lead to unnecessary radiation. Conversely, a position statement released by the Scoliosis Research Society, the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America, the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends scoliosis screening during routine pediatric office visits.16 Screening for girls is recommended at ages 10 and 12 years, and for boys, once between ages 13 and 14 years. The statement highlights evidence showing that focused screening by appropriate personnel has value in detecting a clinically significant curve (> 20°).

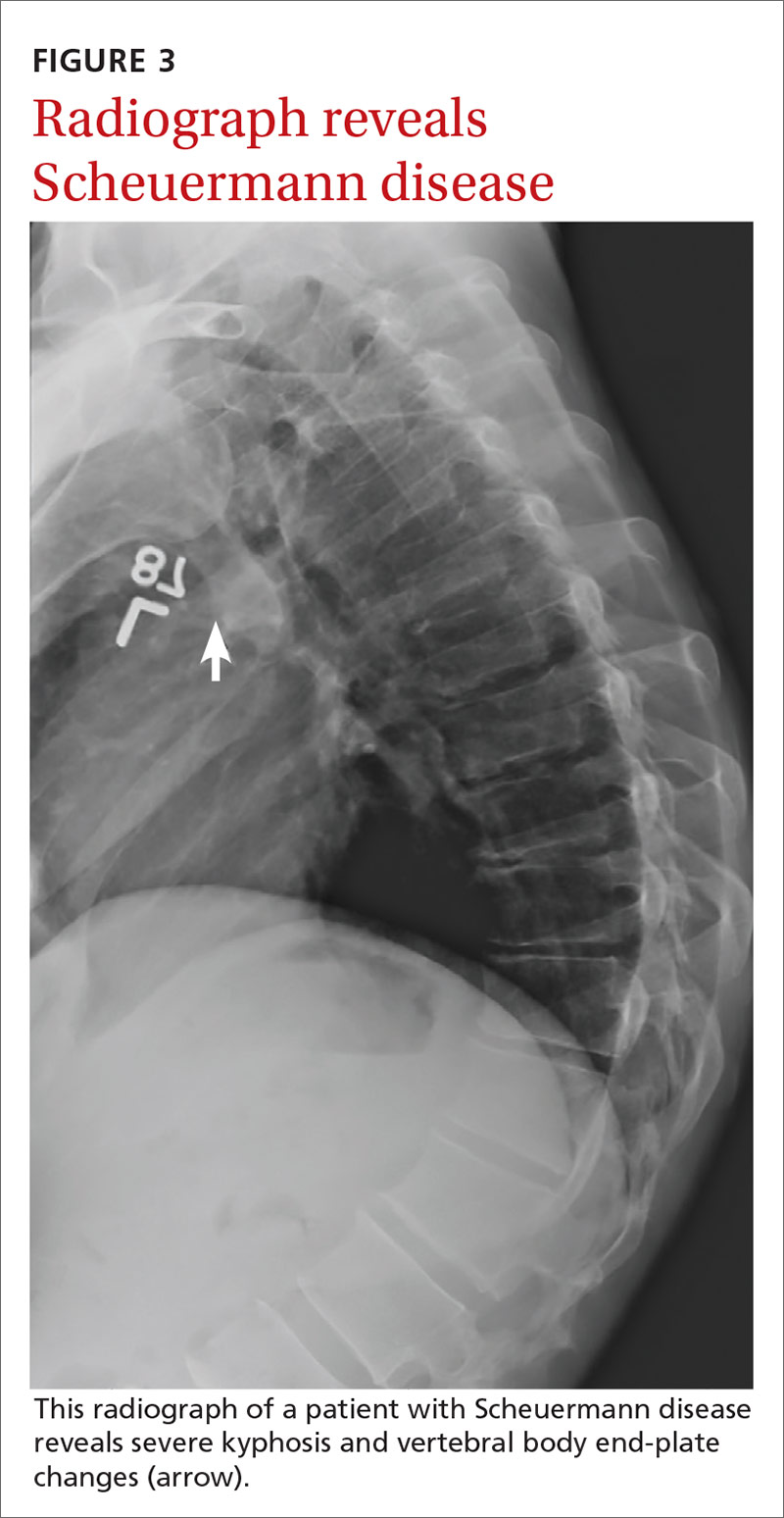

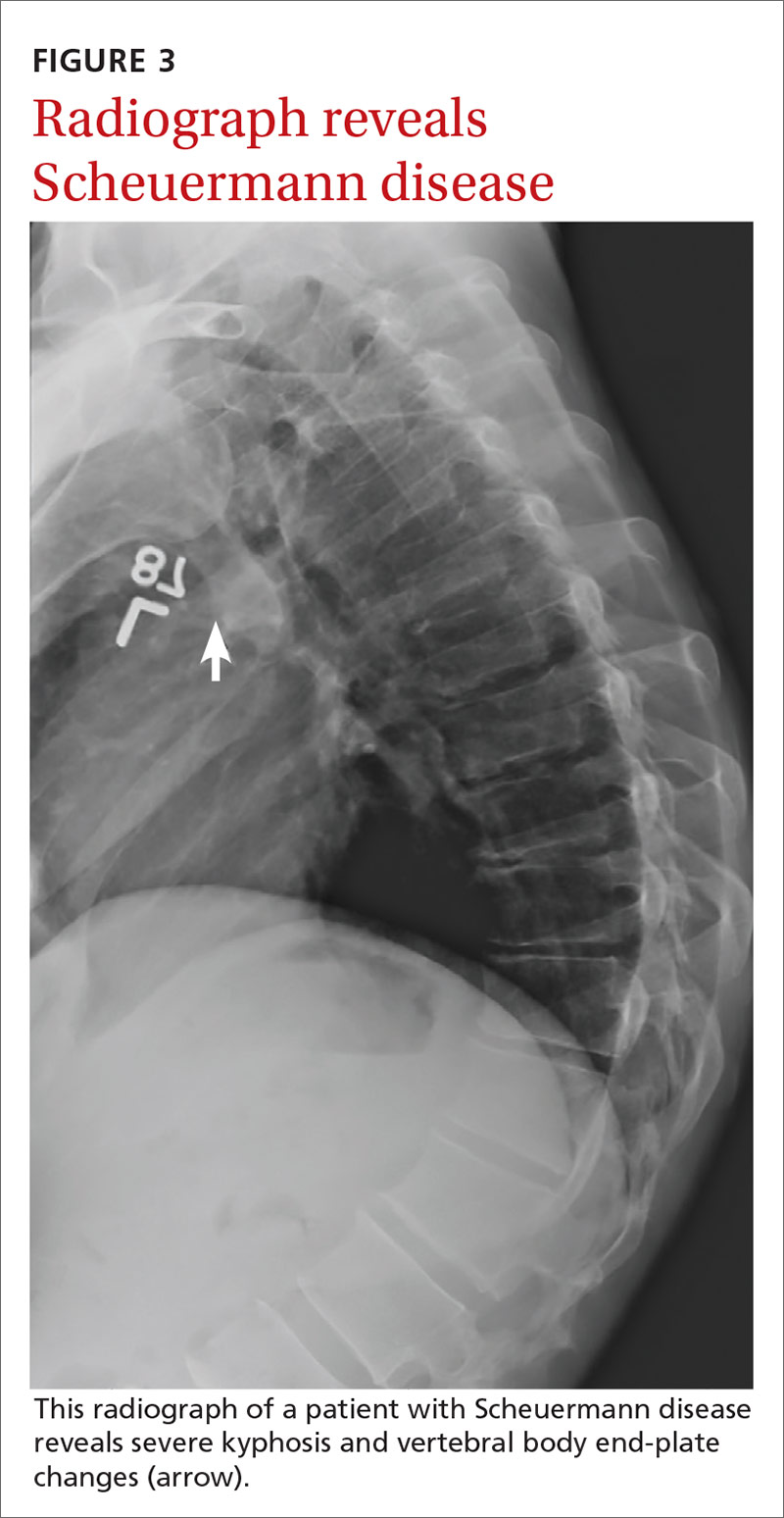

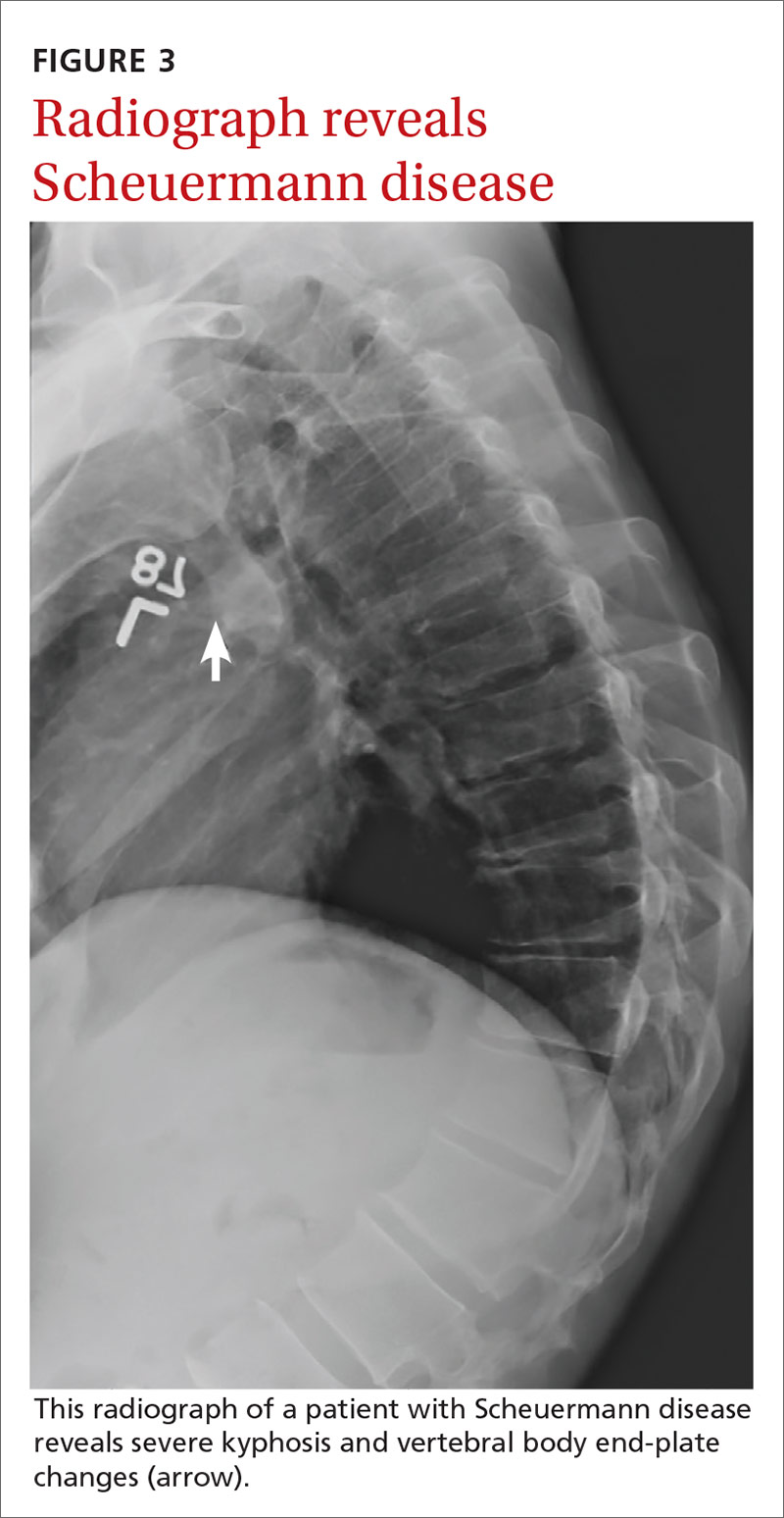

Scheuermann disease is a rare cause of back pain in children that usually develops during adolescence and results in increasing thoracic kyphosis. An autosomal dominant mutation plays a role in this disease of the growth cartilage endplate; repetitive strain on the growth cartilage is also a contributing factor.17,18 An atypical variant manifests with kyphosis in the thoracolumbar region.17

Continue to: Other causes of low back pain

Other causes of low back pain—including inflammatory arthritis, infection (eg, discitis), and tumor—are rare in children but must always be considered, especially in the setting of persistent symptoms.4,19-21 More on the features of these conditions is listed in TABLE 1.1-7,13-15,17-30

History: Focus on onset, timing, and duration of symptoms

As with adults, obtaining a history that includes the onset, timing, and duration of symptoms is key in the evaluation of low back pain in children, as is obtaining a history of the patient’s activities; sports that repetitively load the lumbar spine in an extended position increase the risk of injury.10

Specific risk factors for low back pain in children and adolescents are poorly understood.4,9,31 Pain can be associated with trauma, or it can have a more progressive or insidious onset. Generally, pain that is present for up to 6 weeks and is intermittent or improving has a self-limited course. Pain that persists beyond 3 to 6 weeks or is worsening is more likely to have an anatomical cause that needs further evaluation.2,3,10,21

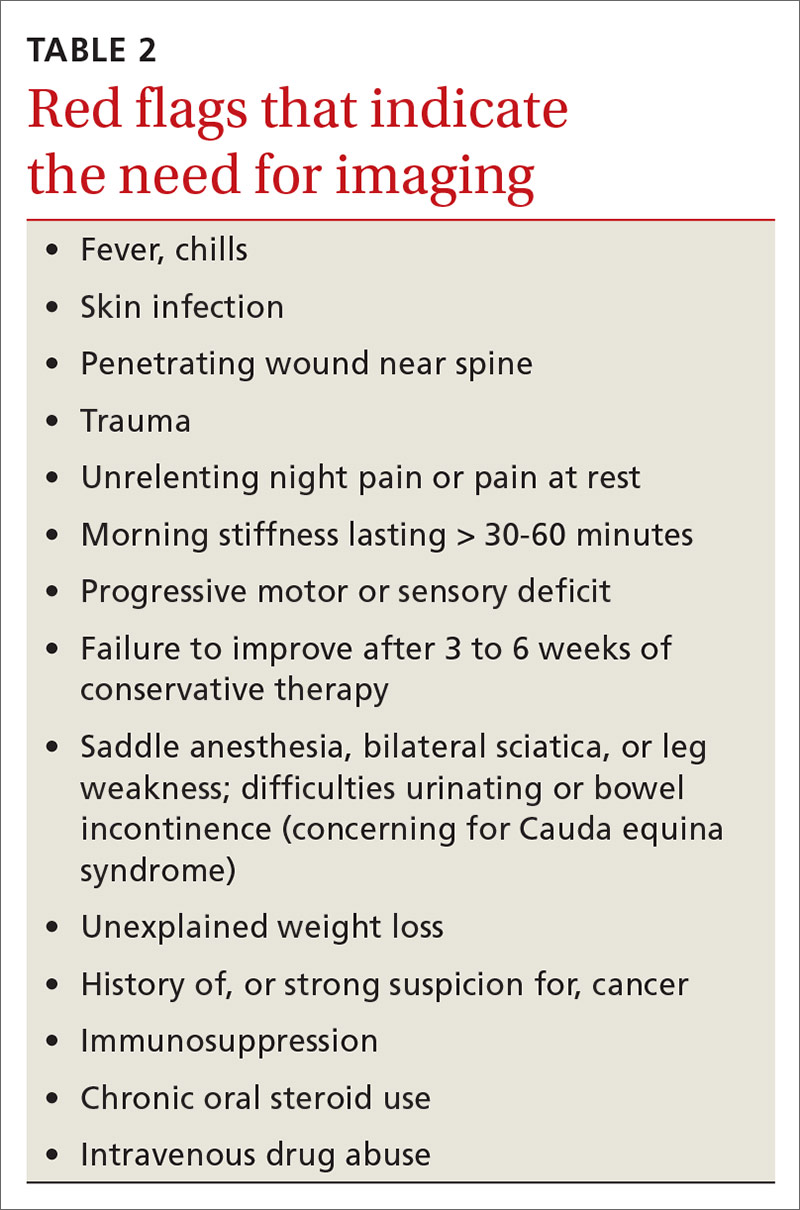

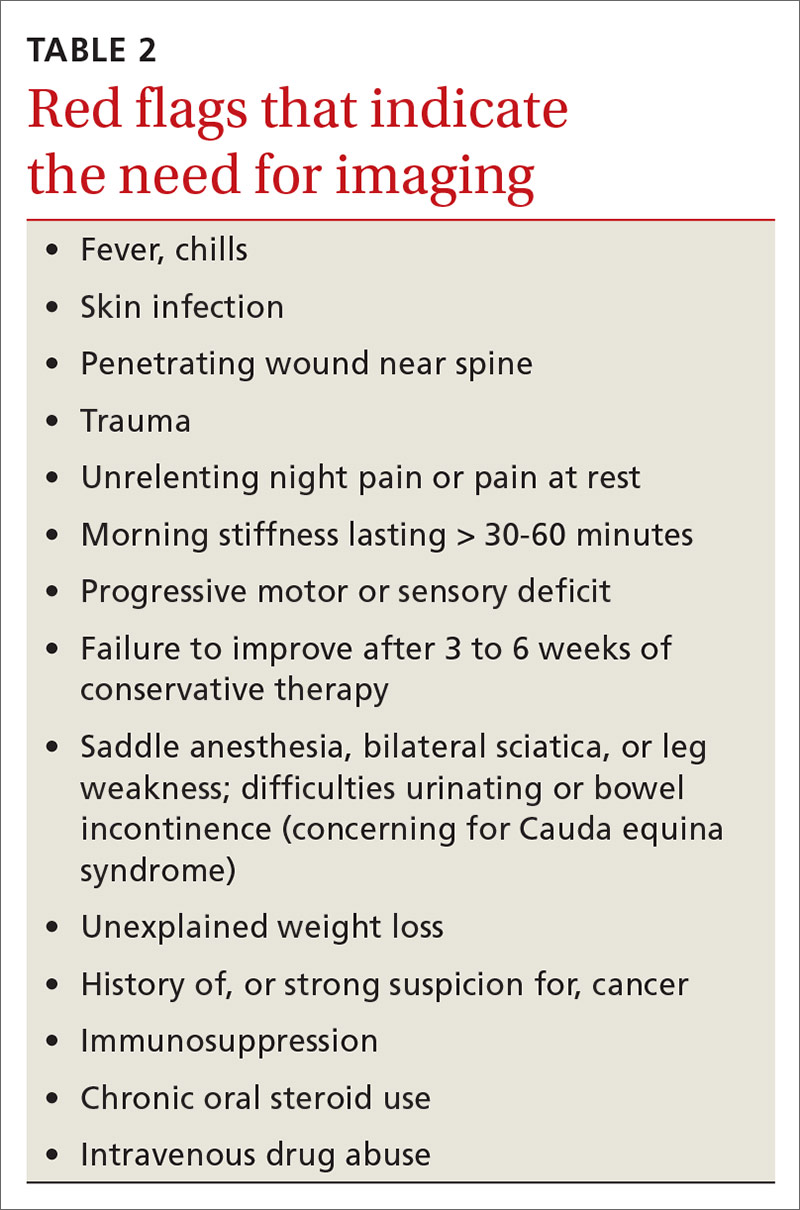

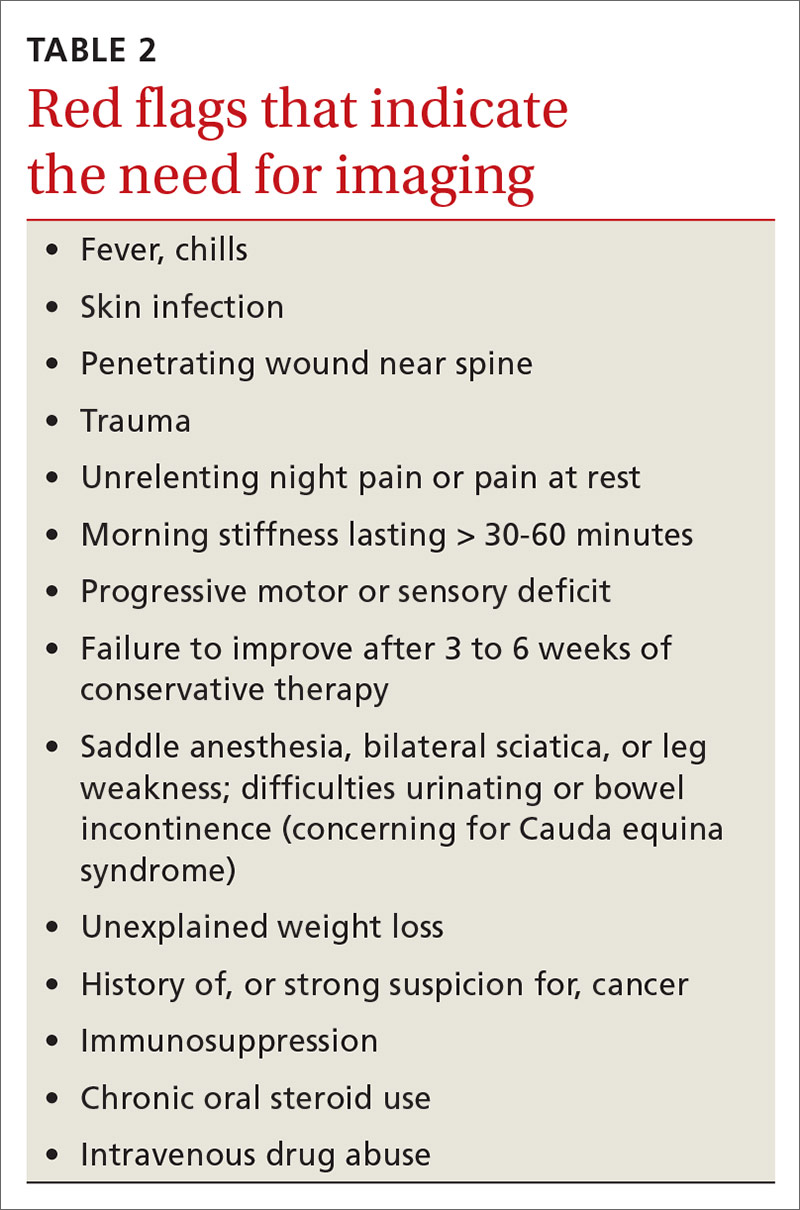

Identifying exacerbating and alleviating factors can provide useful information. Pain that is worse with lumbar flexion is more likely to come from muscular strain or disc pathology. Pain with extension is more likely due to a structural cause such as spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or Scheuermann disease.2,4,10,17,18,21 See TABLE 2 for red flag symptoms that indicate the need for imaging and further work-up.

The physical exam: Visualize, assess range of motion, and reproduce pain

The physical examination of any patient with low back pain should include direct visualization and inspection of the back, spine, and pelvis; palpation of the spine and paraspinal regions; assessment of lumbar range of motion and of the lumbar nerve roots, including tests of sensation, strength, and deep tendon reflexes; and an evaluation of the patient’s posture, which can provide clues to underlying causes of pain.

Continue to: Increased thoracic kyphosis...

Increased thoracic kyphosis that is not reversible is concerning for Scheuermann disease.9,17,18 A significant elevation in one shoulder or side of the pelvis can be indicative of scoliosis. Increased lumbar lordosis may predispose a patient to spondylolysis.

In patients with spondylolysis, lumbar extension will usually reproduce pain, which is often unilateral. Hyperextension in a single-leg stance, commonly known as the Stork test, is positive for unilateral spondylolysis when it reproduces pain on the ipsilateral side. The sensitivity of the Stork test for unilateral spondylolysis is approximately 50%.32 (For more information on the Stork test, see www.physio-pedia.com/Stork_test.)

Pain reproduced with lumbar flexion is less concerning for bony pathology and is most often related to soft-tissue strain. Lumbar flexion with concomitant radicular pain is associated with disc pathology.8 Pain with a straight-leg raise is also associated with disk pathology, especially if raising the contralateral leg increases pain.8

Using a scoliometer. Evaluate the flexed spine for the presence of asymmetry, which can indicate scoliosis.33 If asymmetry is present, use a scoliometer to determine the degree of asymmetry. Zero to 5° is considered clinically insignificant; monitor and reevaluate these patients at subsequent visits.34,35 Ten degrees or more of asymmetry with a scoliometer should prompt you to order radiographs.35,36 A smartphone-based scoliometer for iPhones was evaluated in 1 study and was shown to have reasonable reliability and validity for clinical use.37

Deformity of the lower extremities. Because low back pain may be caused by biomechanical or structural deformity of the lower extremities, examine the flexibility of the hip flexors, gluteal musculature, hamstrings, and the iliotibial band.38 In addition, evaluate for leg-length discrepancy and lower-extremity malalignment, such as femoral anteversion, tibial torsion, or pes planus.

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging: Know when it’s needed