User login

Web-based interviews, financial planning in a pandemic, and more

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Dear colleagues,

I’m excited to introduce the November issue of The New Gastroenterologist – the last edition of 2020 features a fantastic line-up of articles! As the year comes to a close, we reflect on what has certainly been an interesting year, defined by a set of unique challenges we have faced as a nation and as a specialty.

The fellowship recruitment season is one that has looked starkly different as interviews have converted to a virtual format. Dr. Wissam Khan, Dr. Nada Al Masalmeh, Dr. Stephanie Judd, and Dr. Diane Levine (Wayne State University) compile a helpful list of tips and tricks on proper interview etiquette in the new era of web-based interviews.

Financial planning in the face of a pandemic is a formidable task – Jonathan Tudor (Fidelity Investments) offers valuable advice for gastroenterologists on how to remain secure in your finances even in uncertain circumstances.

This quarter’s “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Yutaka Tomizawa (University of Washington), is a comprehensive piece elucidating the role of gastroenterologists in the management of gastric cancer. The article reviews the individual risk factors that exist for gastric cancer and provides guidance on how to stratify patients accordingly, which is critical in the ethnically diverse population of the United States.

Keeping a procedure log during fellowship can seem daunting and cumbersome, but it is important. Dr. Houman Rezaizadeh (University of Connecticut) shares his program’s experience with the AGA Procedure Log, a convenient online tracking tool, which can provide accurate and secure documentation of endoscopic procedures performed throughout fellowship.

Dr. Nazia Hasan (North Bay Health Care) and Dr. Allison Schulman (University of Michigan) broach an incredibly important topic: the paucity of women in interventional endoscopy. Dr. Hasan and Dr. Shulman candidly discuss the barriers women face in pursuing this subspecialty and offer practical solutions on how to approach these challenges – a piece that will surely resonate with many young gastroenterologists.

We wrap up our first year of TNG’s ethics series with two cases discussing the utilization of cannabis therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Dr. Jami Kinnucan (University of Michigan) and Dr. Arun Swaminath (Lenox Hill Hospital) systematically review existing data on the efficacy of cannabis use in IBD, the risks associated with therapy, and legal implications for both physicians and patients.

Also in this issue is a high-yield clinical review on the endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections by Dr. Robert Moran and Dr. Joseph Elmunzer (Medical University of South Carolina). Dr. Manol Jovani (Johns Hopkins) teaches us about confounding – a critical concept to keep in mind when evaluating any manuscript. Lastly, our DHPA Private Practice Perspectives article, written by Dr. Mehul Lalani (US Digestive), reviews how quality measures and initiatives are tracked and implemented in private practice.

If you have interest in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Ryan Farrell ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Stay well,

Vijaya L. Rao, MD

Editor in Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition

Role of gastroenterologists in the U.S. in the management of gastric cancer

Introduction

Although gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world, the burden of gastric cancer in the United States tends to be underestimated relative to that of other cancers of the digestive system. In fact, the 5-year survival rate from gastric cancer remains poor (~32%)1 in the United States, and this is largely because gastric cancers are not diagnosed at an early stage when curative therapeutic options are available. Cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists in the United States to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is an inherited form of diffuse-type gastric cancer and has pathogenic variants in the E-cadherin gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer in individuals with HDGC is very high, and prophylactic total gastrectomy is usually advised. This article focuses on intestinal type cancer.

Epidemiology

Gastric cancer (proximal and distal gastric cancer combined) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with 1,033,701 new cases and 782,685 deaths in 2018.2 Gastric cancer is subcategorized based on location (proximal [i.e., esophagogastric junctional, gastric cardia] and distal) and histology (intestinal and diffuse type), and each subtype is considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Distal intestinal type gastric cancer is most commonly encountered in clinical practice. In this article, gastric cancer will signify distal intestinal type gastric cancer unless it is otherwise noted. In general, incidence rates are about twofold higher in men than in women. There is marked geographic variation in incidence rates, and the age-standardized incidence rates in eastern Asia (32.1 and 13.2, per 100,000) are approximately six times higher than those in northern America (5.6 and 2.8, per 100,000) in both men and women, respectively.2 Recent studies evaluating global trends in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have demonstrated decreases worldwide.3-5 However, the degree of decrease in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer varies substantially across geographic regions, reflecting the heterogeneous distribution of risk profiles. A comprehensive analysis of a U.S. population registry demonstrated a linear decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States (0.94% decrease per year between 2001 and 2015),6 though the annual percent change in the gastric cancer mortality in the United States was lower (around 2% decrease per year between 1980 and 2011) than in other countries.3Several population-based studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that the incidence of gastric cancer varied by ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin, and the highest incidence was observed among Asian immigrants.7,8 A comprehensive meta-analysis examining the risk of gastric cancer in immigrants from high-incidence regions to low-incidence regions found a persistently higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality among immigrants.9 These results indicate that there are important risk factors such as environmental and dietary factors in addition to the traditionally considered risk factors including male gender, age, family history, and tobacco use. A survey conducted in an ethnically and culturally diverse U.S. city showed that gastroenterology providers demonstrated knowledge deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with increased risk of gastric cancer.10 Recognizing individualized risk profiles in higher-risk groups (e.g., immigrants from higher-incidence/prevalence regions) is important for optimizing management of gastric cancer in the United States.

Assessment and management of modifiable risk factors

Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen, is the most well-recognized risk factor for gastric cancer, particularly noncardia gastric cancer.11 Since a landmark longitudinal follow-up study in Japan demonstrated that people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection,12 accumulating evidence largely from Asian countries has shown that eradication of H. pylori is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer regardless of baseline risk.13 There are also data on the protective effect for gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication in asymptomatic individuals. Another meta-analysis of six international randomized control trials demonstrated a 34% relative risk reduction of gastric cancer occurrence in asymptomatic people (relative risk of developing gastric cancer was 0.66 in those who received eradication therapy compared with those with placebo or no treatment, 95% CI, 0.46-0.95).14 A U.S. practice guideline published after these meta-analyses recommends that all patients with a positive test indicating active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment and testing to prove eradication,15 though the recommendation was not purely intended to reduce the gastric cancer risk in U.S. population. Subsequently, a Department of Veterans Affairs cohort study added valuable insights from a U.S. experience to the body of evidence from other countries with higher prevalence. In this study of more than 370,000 patients with a history of H. pylori infection, the detection and successful eradication of H. pylori was associated with a 76% lower incidence of gastric cancer compared with people without H. pylori treatment.16 This study also provided insight into H. pylori treatment practice patterns. Of patients with a positive H. pylori test result (stool antigen, urea breath test, or pathology), approximately 75% were prescribed an eradication regimen and only 21% of those underwent eradication tests. A low rate (24%) of eradication testing was subsequently reported by the same group among U.S. patients regardless of gastric cancer risk profiles.17 The lesson from the aforementioned study is that treatment and eradication of H. pylori even among asymptomatic U.S. patients reduces the risk of subsequent gastric cancer. However, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study given the nature of the Veterans Affairs cohort, and more data are required to justify the implementation of nationwide preventive H. pylori screening in the general U.S. population.

Smoking has been recognized as the other important risk factor. A study from the European prospective multicenter cohort demonstrated a significant association of cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk (HR for ever-smokers 1.45 [95% CI, 1.08-1.94], current-smokers in males 1.73 [95% CI, 1.06-2.83], and current smokers in females 1.87 [95% CI, 1.12-3.12], respectively) after adjustment for educational level, dietary consumption profiles, alcohol intake, and body mass index (BMI).18 A subsequent meta-analysis provided solid evidence of smoking as the important behavioral risk factor for gastric cancer.19 Smoking also predisposed to the development of proximal gastric cancer.20 Along with other cancers in the digestive system such as in the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, a significant association of BMI and the risk of proximal gastric cancer (RR of the highest BMI category compared with normal BMI, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.3-2.5]) was reported, with positive dose-response relationships; however, the association was not sufficient for distal gastric cancer.21 There is also evidence to show a trend of greater alcohol consumption (>45 grams per day [about 3 drinks a day]) associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer.21 It has been thought that salt and salt-preserved food increase the risk of gastric cancer. It should be noted that the observational studies showing the associations were published from Asian countries where such foods were a substantial part of traditional diets (e.g., salted vegetables in Japan) and the incidence of gastric cancer is high. There is also a speculation that preserved foods may have been eaten in more underserved, low socioeconomic regions where refrigeration was not available and prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher. Except for documented inherited form of gastric cancer (e.g., HDGC or hereditary cancer syndromes), most gastric cancers are considered sporadic. A recent randomized study published from South Korea investigated a cohort of higher-risk asymptomatic patients with family history significant for gastric cancer. This study of 1,676 subjects with a median follow-up of 9.2 years showed that successful eradication of H. pylori in the first-degree relatives of those with gastric cancer significantly reduced the risk (HR 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21-0.94]) of developing gastric cancer.22 As previously discussed, in the United States where the prevalence of H. pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer are both lower than in some Asian countries, routine screening of asymptomatic individuals for H. pylori is not justified yet. There may be a role for screening individuals who are first-generation immigrants from areas of high gastric cancer incidence and also have a first-degree relative with gastric cancer.

Who should we consider high risk and offer screening EGD?

With available evidence to date, screening for gastric cancer in a general U.S. population is not recommended. However, it is important to acknowledge the aforementioned varying incidence of gastric cancer in the United States among ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. Immigrants from high-incidence regions maintain a higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality even after migration to lower-incidence regions. The latter comprehensive study estimated that as many as 12.7 million people (29.4% of total U.S. immigrant population) have emigrated from higher-incidence regions including East Asian and some Central American countries.9 Indeed, an opportunistic nationwide gastric cancer screening program has been implemented in South Korea (beginning at age 40, biannually)23 and Japan (beginning at age 50, biannually).24 Two decision-analytic simulation studies have provided insight into the uncertainty about the cost effectiveness for potential targeted gastric cancer screening in higher-risk populations in the United States. One study demonstrated that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening for otherwise asymptomatic Asian American people (as well as Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks) at the time of screening colonoscopy at 50 years of age with continued endoscopic surveillance every 3 years was cost effective, only if gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) or more advanced lesions were diagnosed at the index screening EGD.25 Previous studies analyzing the cost effectiveness for gastric cancer screening in the United States had the limitation of not stratifying according to race or ethnicity, or accounting for patients diagnosed with GIM. Subsequently, the same research group extended this model analysis and has published additional findings that this strategy is cost effective for each of the most prevalent Asian American ethnicities (Chinese, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Americans) in the United States irrespective of sex.26 Although the authors raised a limitation that additional risk factors such as family history, tobacco use, or persistent H. pylori infection were not considered in the model because data regarding differentiated noncardia gastric cancer risk among Asian American ethnicities based on these risk factors are not available.

These two model analytic studies added valuable insights to the body of evidence that subsequent EGDs after the one-time bundled EGD is cost effective for higher-risk asymptomatic people in the United States, if the index screening EGD with gastric mucosal biopsies demonstrates at least GIM. Further population-based research to elucidate risk stratification among higher-risk people will provide a schema that could standardize management and resource allocation as well as increase the cost effectiveness of a gastric cancer screening program in the United States. The degree of risk of developing gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis varies among the reported studies.27-29 Although the benefit of endoscopic screening in patients with autoimmune gastritis has not been established, a single endoscopic evaluation should be recommended soon after the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis in order to identify prevalent neoplastic lesions.30

Practical consideration when we perform EGD for early gastric cancer screening

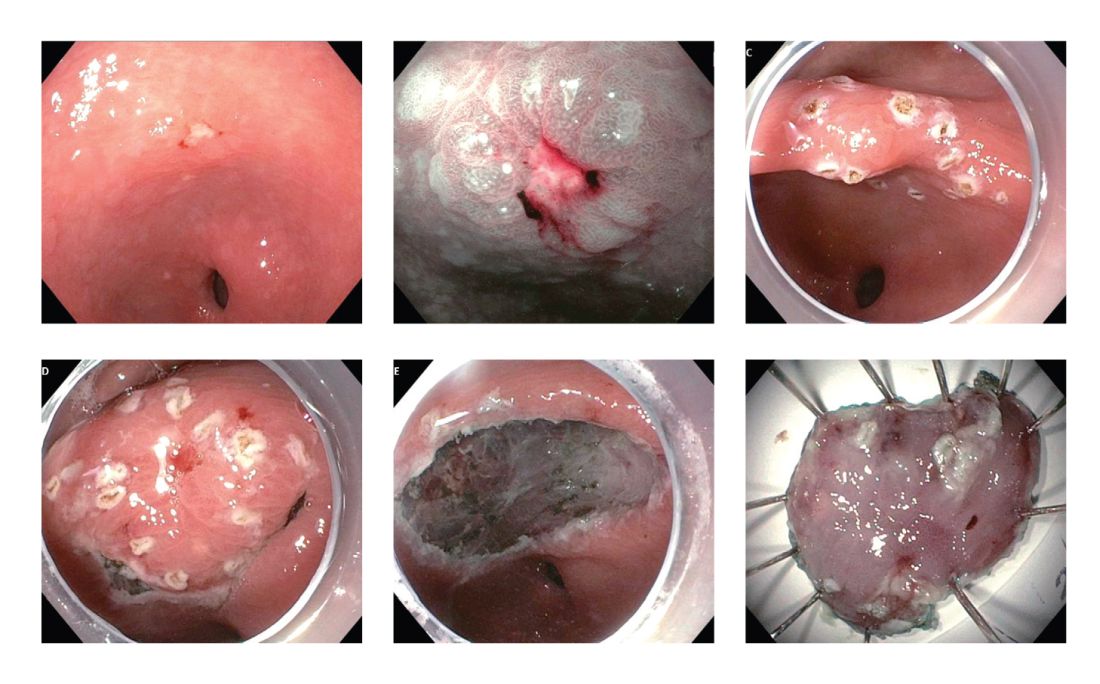

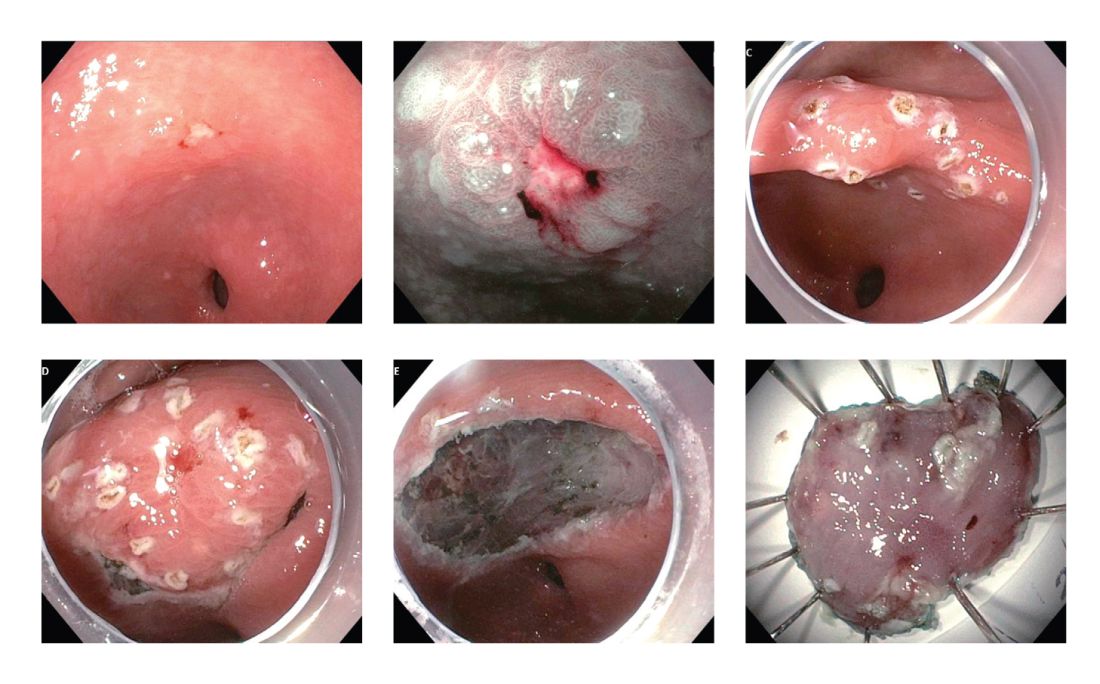

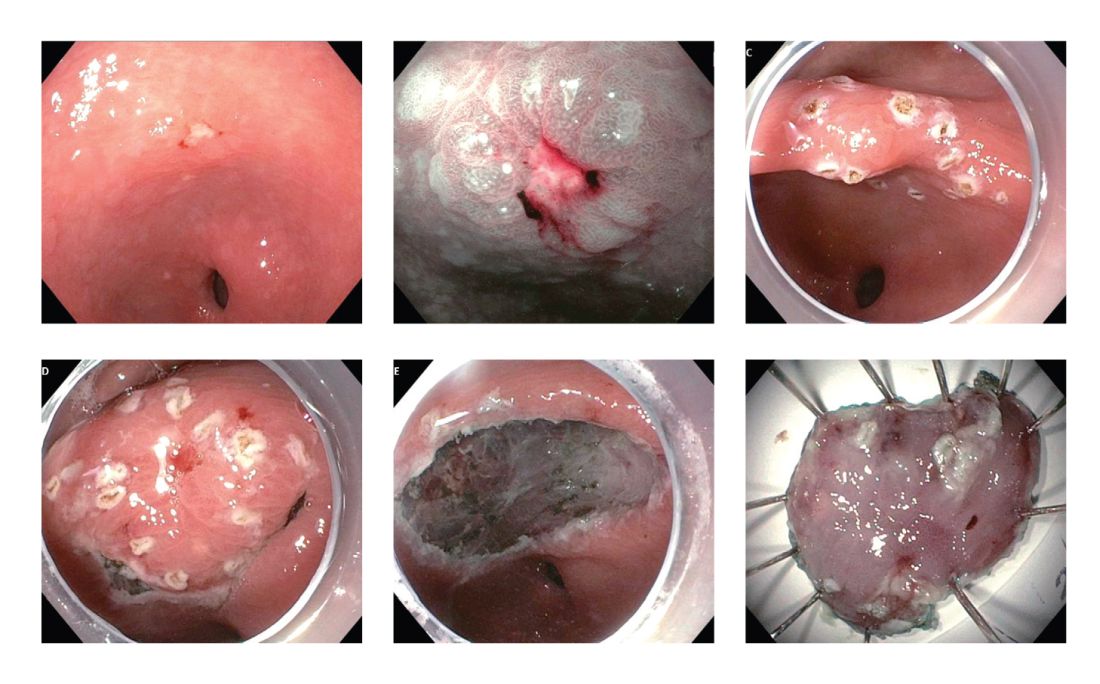

Identification of higher-risk patients should alert an endoscopist to observe mucosa with greater care with a lower threshold to biopsy any suspicious lesions. Preprocedural risk stratification for each individual before performing diagnostic EGD will improve early gastric cancer detection. While we perform EGD, detecting precursor lesions (atrophic gastritis and GIM) is as important as diagnosing an early gastric cancer. Screening and management of patients with precursor lesions (i.e., atrophic gastritis and GIM) is beyond the scope of this article, and this was published in a previous issue of the New Gastroenterologist. It is important to first grossly survey the entire gastric mucosa using high-definition while light (HDWL) endoscopy and screen for any focal irregular (raised or depressed) mucosal lesions. These lesions are often erythematous and should be examined carefully. Use of mucolytic and/or deforming agents (e.g., N-acetylcysteine or simethicone) is recommended for the improvement of visual clarity of gastric mucosa.31 Simethicone is widely used in the United States for colonoscopy and should also be available at the time of EGD for better gastric mucosal visibility. If irregular mucosal lesions are noted, this area should also be examined under narrowband imaging (NBI) in addition to HDWL. According to a simplified classification consisting of mucosal and vascular irregularity, NBI provides better mucosal surface morphology for diagnosis of early gastric cancer compared with HDWL, and a thorough examination of the surface characteristics is a prerequisite.32 This classification was further validated in a randomized control trial, and NBI increased sensitivity for the diagnosis of neoplasia compared with HDWL (92 % vs. 74 %).33 The majority of institutions in the United States have a newer-generation NBI (Olympus America, EVIS EXERA III video system, GIF-HQ190), which provides brighter endoscopic images to better characterize gastric neoplastic lesions. Once we recognize an area suspicious for neoplasia, we should describe the macroscopic features according to a classification system.

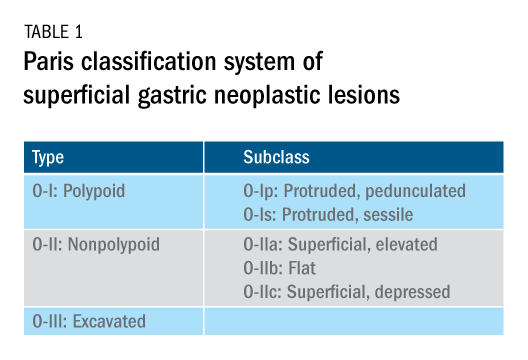

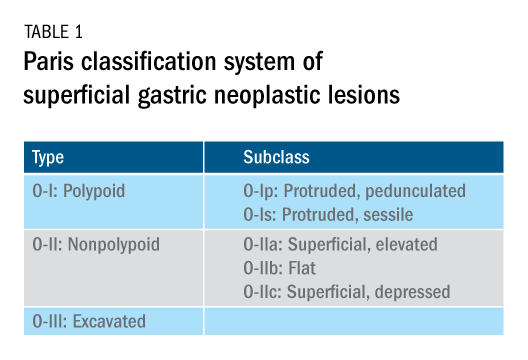

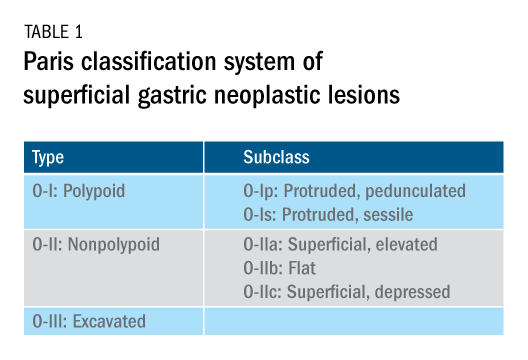

The Paris classification, one of the most widely recognized classification systems among U.S. gastroenterologists, is recommended for gastric neoplastic lesions.34Gastric neoplastic lesions with a “superficial” endoscopic appearance are classified as subtypes of “type 0.” The term “type 0” was chosen to distinguish the classification of “superficial” lesions from the Borrmann classification for “advanced” gastric tumors, which includes types 1 to 4. In the classification, a neoplastic lesion is called “superficial” when its endoscopic appearance suggests that the depth of penetration in the digestive wall is not more than into the submucosa (i.e., there is no infiltration of the muscularis propria). The distinctive characters of polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions are summarized in Table 1. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has steadily gained acceptance for the treatment of early gastric cancer in the United States. The American Gastroenterological Association recommended in the 2019 institutional updated clinical practice guideline that ESD should be considered the first-line therapy for visible, endoscopically resectable, superficial gastric neoplasia.35 This recommendation is further supported by the published data on efficacy and safety of ESD for early gastric neoplasia in a large multicenter cohort in the United States.36 For all suspicious lesions, irrespective of pathological neoplastic confirmation, referral to an experienced center for further evaluation and endoscopic management should be considered. Lastly, all patients with early gastric cancer should be evaluated for H. pylori infection and treated if the test is positive. Eradication of H. pylori is associated with a lower rate of metachronous gastric cancer,37 and treatment of H. pylori as secondary prevention is also recommended.

Conclusion

As summarized above, cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the U.S. varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. New gastroenterologists will need to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Risk stratification before performing endoscopic evaluation will improve early gastric cancer detection and make noninvasive, effective therapies an option.

References

1. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html.

2. Bray F et al. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

3. Ferro A et al. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1330-44.

4. Luo G et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1333-44.

5. Arnold M et al. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1164-87.

6. Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-42.

7. Kim Y et al. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015066.

8. Kamineni A et al. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:77-83.

9. Pabla BS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:347-59.

10. Shah SC et al. Knowledge Gaps among Physicians Caring for Multiethnic Populations at Increased Gastric Cancer Risk. Gut Liver. 2018 Jan 15;12(1):38-45.

11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. IARC. July 7, 2019. 12. Uemura N et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-9.

13. Lee YC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113-24.

14. Ford AC et al. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

15. Chey W et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-39.

16. Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:527-36.

17. Kumar S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 6;S1542-3565(20)30436-5.

18. González CA et al. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:629-34.

19. Ladeiras-Lopes R et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689-701.

20. Cavaleiro-Pinto M et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375-87.

21. Lauby-Secretan B et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794-8.

22. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:427-36.

23. Kim BJ et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:736-41.

24. Hamashima C. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:278–86.

25. Saumoy M et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:648-60.

26. Shah SC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21:S1542-3565(20)30993-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.031.

27. Brinton LA et al. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:810-3.

28. Hsing AW et al. Cancer. 1993;71:745-50.

29. Schafer LW et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:444-8.

30. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8.

31. Chiu PWY et al. Gut. 2019;68:186-97.

32. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2012;44:236-46.

33. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2016;48:723-30.

34. Participants in the Paris Workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43.

35. Draganov PV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:16-25.

36. Ngamruengphong S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun 18;S1542-3565(20)30834-X. Online ahead of print.

37. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085-95.

Dr. Tomizawa is a clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle.

Introduction

Although gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world, the burden of gastric cancer in the United States tends to be underestimated relative to that of other cancers of the digestive system. In fact, the 5-year survival rate from gastric cancer remains poor (~32%)1 in the United States, and this is largely because gastric cancers are not diagnosed at an early stage when curative therapeutic options are available. Cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists in the United States to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is an inherited form of diffuse-type gastric cancer and has pathogenic variants in the E-cadherin gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer in individuals with HDGC is very high, and prophylactic total gastrectomy is usually advised. This article focuses on intestinal type cancer.

Epidemiology

Gastric cancer (proximal and distal gastric cancer combined) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with 1,033,701 new cases and 782,685 deaths in 2018.2 Gastric cancer is subcategorized based on location (proximal [i.e., esophagogastric junctional, gastric cardia] and distal) and histology (intestinal and diffuse type), and each subtype is considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Distal intestinal type gastric cancer is most commonly encountered in clinical practice. In this article, gastric cancer will signify distal intestinal type gastric cancer unless it is otherwise noted. In general, incidence rates are about twofold higher in men than in women. There is marked geographic variation in incidence rates, and the age-standardized incidence rates in eastern Asia (32.1 and 13.2, per 100,000) are approximately six times higher than those in northern America (5.6 and 2.8, per 100,000) in both men and women, respectively.2 Recent studies evaluating global trends in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have demonstrated decreases worldwide.3-5 However, the degree of decrease in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer varies substantially across geographic regions, reflecting the heterogeneous distribution of risk profiles. A comprehensive analysis of a U.S. population registry demonstrated a linear decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States (0.94% decrease per year between 2001 and 2015),6 though the annual percent change in the gastric cancer mortality in the United States was lower (around 2% decrease per year between 1980 and 2011) than in other countries.3Several population-based studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that the incidence of gastric cancer varied by ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin, and the highest incidence was observed among Asian immigrants.7,8 A comprehensive meta-analysis examining the risk of gastric cancer in immigrants from high-incidence regions to low-incidence regions found a persistently higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality among immigrants.9 These results indicate that there are important risk factors such as environmental and dietary factors in addition to the traditionally considered risk factors including male gender, age, family history, and tobacco use. A survey conducted in an ethnically and culturally diverse U.S. city showed that gastroenterology providers demonstrated knowledge deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with increased risk of gastric cancer.10 Recognizing individualized risk profiles in higher-risk groups (e.g., immigrants from higher-incidence/prevalence regions) is important for optimizing management of gastric cancer in the United States.

Assessment and management of modifiable risk factors

Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen, is the most well-recognized risk factor for gastric cancer, particularly noncardia gastric cancer.11 Since a landmark longitudinal follow-up study in Japan demonstrated that people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection,12 accumulating evidence largely from Asian countries has shown that eradication of H. pylori is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer regardless of baseline risk.13 There are also data on the protective effect for gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication in asymptomatic individuals. Another meta-analysis of six international randomized control trials demonstrated a 34% relative risk reduction of gastric cancer occurrence in asymptomatic people (relative risk of developing gastric cancer was 0.66 in those who received eradication therapy compared with those with placebo or no treatment, 95% CI, 0.46-0.95).14 A U.S. practice guideline published after these meta-analyses recommends that all patients with a positive test indicating active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment and testing to prove eradication,15 though the recommendation was not purely intended to reduce the gastric cancer risk in U.S. population. Subsequently, a Department of Veterans Affairs cohort study added valuable insights from a U.S. experience to the body of evidence from other countries with higher prevalence. In this study of more than 370,000 patients with a history of H. pylori infection, the detection and successful eradication of H. pylori was associated with a 76% lower incidence of gastric cancer compared with people without H. pylori treatment.16 This study also provided insight into H. pylori treatment practice patterns. Of patients with a positive H. pylori test result (stool antigen, urea breath test, or pathology), approximately 75% were prescribed an eradication regimen and only 21% of those underwent eradication tests. A low rate (24%) of eradication testing was subsequently reported by the same group among U.S. patients regardless of gastric cancer risk profiles.17 The lesson from the aforementioned study is that treatment and eradication of H. pylori even among asymptomatic U.S. patients reduces the risk of subsequent gastric cancer. However, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study given the nature of the Veterans Affairs cohort, and more data are required to justify the implementation of nationwide preventive H. pylori screening in the general U.S. population.

Smoking has been recognized as the other important risk factor. A study from the European prospective multicenter cohort demonstrated a significant association of cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk (HR for ever-smokers 1.45 [95% CI, 1.08-1.94], current-smokers in males 1.73 [95% CI, 1.06-2.83], and current smokers in females 1.87 [95% CI, 1.12-3.12], respectively) after adjustment for educational level, dietary consumption profiles, alcohol intake, and body mass index (BMI).18 A subsequent meta-analysis provided solid evidence of smoking as the important behavioral risk factor for gastric cancer.19 Smoking also predisposed to the development of proximal gastric cancer.20 Along with other cancers in the digestive system such as in the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, a significant association of BMI and the risk of proximal gastric cancer (RR of the highest BMI category compared with normal BMI, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.3-2.5]) was reported, with positive dose-response relationships; however, the association was not sufficient for distal gastric cancer.21 There is also evidence to show a trend of greater alcohol consumption (>45 grams per day [about 3 drinks a day]) associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer.21 It has been thought that salt and salt-preserved food increase the risk of gastric cancer. It should be noted that the observational studies showing the associations were published from Asian countries where such foods were a substantial part of traditional diets (e.g., salted vegetables in Japan) and the incidence of gastric cancer is high. There is also a speculation that preserved foods may have been eaten in more underserved, low socioeconomic regions where refrigeration was not available and prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher. Except for documented inherited form of gastric cancer (e.g., HDGC or hereditary cancer syndromes), most gastric cancers are considered sporadic. A recent randomized study published from South Korea investigated a cohort of higher-risk asymptomatic patients with family history significant for gastric cancer. This study of 1,676 subjects with a median follow-up of 9.2 years showed that successful eradication of H. pylori in the first-degree relatives of those with gastric cancer significantly reduced the risk (HR 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21-0.94]) of developing gastric cancer.22 As previously discussed, in the United States where the prevalence of H. pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer are both lower than in some Asian countries, routine screening of asymptomatic individuals for H. pylori is not justified yet. There may be a role for screening individuals who are first-generation immigrants from areas of high gastric cancer incidence and also have a first-degree relative with gastric cancer.

Who should we consider high risk and offer screening EGD?

With available evidence to date, screening for gastric cancer in a general U.S. population is not recommended. However, it is important to acknowledge the aforementioned varying incidence of gastric cancer in the United States among ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. Immigrants from high-incidence regions maintain a higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality even after migration to lower-incidence regions. The latter comprehensive study estimated that as many as 12.7 million people (29.4% of total U.S. immigrant population) have emigrated from higher-incidence regions including East Asian and some Central American countries.9 Indeed, an opportunistic nationwide gastric cancer screening program has been implemented in South Korea (beginning at age 40, biannually)23 and Japan (beginning at age 50, biannually).24 Two decision-analytic simulation studies have provided insight into the uncertainty about the cost effectiveness for potential targeted gastric cancer screening in higher-risk populations in the United States. One study demonstrated that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening for otherwise asymptomatic Asian American people (as well as Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks) at the time of screening colonoscopy at 50 years of age with continued endoscopic surveillance every 3 years was cost effective, only if gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) or more advanced lesions were diagnosed at the index screening EGD.25 Previous studies analyzing the cost effectiveness for gastric cancer screening in the United States had the limitation of not stratifying according to race or ethnicity, or accounting for patients diagnosed with GIM. Subsequently, the same research group extended this model analysis and has published additional findings that this strategy is cost effective for each of the most prevalent Asian American ethnicities (Chinese, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Americans) in the United States irrespective of sex.26 Although the authors raised a limitation that additional risk factors such as family history, tobacco use, or persistent H. pylori infection were not considered in the model because data regarding differentiated noncardia gastric cancer risk among Asian American ethnicities based on these risk factors are not available.

These two model analytic studies added valuable insights to the body of evidence that subsequent EGDs after the one-time bundled EGD is cost effective for higher-risk asymptomatic people in the United States, if the index screening EGD with gastric mucosal biopsies demonstrates at least GIM. Further population-based research to elucidate risk stratification among higher-risk people will provide a schema that could standardize management and resource allocation as well as increase the cost effectiveness of a gastric cancer screening program in the United States. The degree of risk of developing gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis varies among the reported studies.27-29 Although the benefit of endoscopic screening in patients with autoimmune gastritis has not been established, a single endoscopic evaluation should be recommended soon after the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis in order to identify prevalent neoplastic lesions.30

Practical consideration when we perform EGD for early gastric cancer screening

Identification of higher-risk patients should alert an endoscopist to observe mucosa with greater care with a lower threshold to biopsy any suspicious lesions. Preprocedural risk stratification for each individual before performing diagnostic EGD will improve early gastric cancer detection. While we perform EGD, detecting precursor lesions (atrophic gastritis and GIM) is as important as diagnosing an early gastric cancer. Screening and management of patients with precursor lesions (i.e., atrophic gastritis and GIM) is beyond the scope of this article, and this was published in a previous issue of the New Gastroenterologist. It is important to first grossly survey the entire gastric mucosa using high-definition while light (HDWL) endoscopy and screen for any focal irregular (raised or depressed) mucosal lesions. These lesions are often erythematous and should be examined carefully. Use of mucolytic and/or deforming agents (e.g., N-acetylcysteine or simethicone) is recommended for the improvement of visual clarity of gastric mucosa.31 Simethicone is widely used in the United States for colonoscopy and should also be available at the time of EGD for better gastric mucosal visibility. If irregular mucosal lesions are noted, this area should also be examined under narrowband imaging (NBI) in addition to HDWL. According to a simplified classification consisting of mucosal and vascular irregularity, NBI provides better mucosal surface morphology for diagnosis of early gastric cancer compared with HDWL, and a thorough examination of the surface characteristics is a prerequisite.32 This classification was further validated in a randomized control trial, and NBI increased sensitivity for the diagnosis of neoplasia compared with HDWL (92 % vs. 74 %).33 The majority of institutions in the United States have a newer-generation NBI (Olympus America, EVIS EXERA III video system, GIF-HQ190), which provides brighter endoscopic images to better characterize gastric neoplastic lesions. Once we recognize an area suspicious for neoplasia, we should describe the macroscopic features according to a classification system.

The Paris classification, one of the most widely recognized classification systems among U.S. gastroenterologists, is recommended for gastric neoplastic lesions.34Gastric neoplastic lesions with a “superficial” endoscopic appearance are classified as subtypes of “type 0.” The term “type 0” was chosen to distinguish the classification of “superficial” lesions from the Borrmann classification for “advanced” gastric tumors, which includes types 1 to 4. In the classification, a neoplastic lesion is called “superficial” when its endoscopic appearance suggests that the depth of penetration in the digestive wall is not more than into the submucosa (i.e., there is no infiltration of the muscularis propria). The distinctive characters of polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions are summarized in Table 1. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has steadily gained acceptance for the treatment of early gastric cancer in the United States. The American Gastroenterological Association recommended in the 2019 institutional updated clinical practice guideline that ESD should be considered the first-line therapy for visible, endoscopically resectable, superficial gastric neoplasia.35 This recommendation is further supported by the published data on efficacy and safety of ESD for early gastric neoplasia in a large multicenter cohort in the United States.36 For all suspicious lesions, irrespective of pathological neoplastic confirmation, referral to an experienced center for further evaluation and endoscopic management should be considered. Lastly, all patients with early gastric cancer should be evaluated for H. pylori infection and treated if the test is positive. Eradication of H. pylori is associated with a lower rate of metachronous gastric cancer,37 and treatment of H. pylori as secondary prevention is also recommended.

Conclusion

As summarized above, cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the U.S. varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. New gastroenterologists will need to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Risk stratification before performing endoscopic evaluation will improve early gastric cancer detection and make noninvasive, effective therapies an option.

References

1. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html.

2. Bray F et al. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

3. Ferro A et al. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1330-44.

4. Luo G et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1333-44.

5. Arnold M et al. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1164-87.

6. Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-42.

7. Kim Y et al. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015066.

8. Kamineni A et al. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:77-83.

9. Pabla BS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:347-59.

10. Shah SC et al. Knowledge Gaps among Physicians Caring for Multiethnic Populations at Increased Gastric Cancer Risk. Gut Liver. 2018 Jan 15;12(1):38-45.

11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. IARC. July 7, 2019. 12. Uemura N et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-9.

13. Lee YC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113-24.

14. Ford AC et al. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

15. Chey W et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-39.

16. Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:527-36.

17. Kumar S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 6;S1542-3565(20)30436-5.

18. González CA et al. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:629-34.

19. Ladeiras-Lopes R et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689-701.

20. Cavaleiro-Pinto M et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375-87.

21. Lauby-Secretan B et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794-8.

22. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:427-36.

23. Kim BJ et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:736-41.

24. Hamashima C. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:278–86.

25. Saumoy M et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:648-60.

26. Shah SC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21:S1542-3565(20)30993-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.031.

27. Brinton LA et al. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:810-3.

28. Hsing AW et al. Cancer. 1993;71:745-50.

29. Schafer LW et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:444-8.

30. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8.

31. Chiu PWY et al. Gut. 2019;68:186-97.

32. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2012;44:236-46.

33. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2016;48:723-30.

34. Participants in the Paris Workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43.

35. Draganov PV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:16-25.

36. Ngamruengphong S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun 18;S1542-3565(20)30834-X. Online ahead of print.

37. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085-95.

Dr. Tomizawa is a clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle.

Introduction

Although gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world, the burden of gastric cancer in the United States tends to be underestimated relative to that of other cancers of the digestive system. In fact, the 5-year survival rate from gastric cancer remains poor (~32%)1 in the United States, and this is largely because gastric cancers are not diagnosed at an early stage when curative therapeutic options are available. Cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. It is important for practicing gastroenterologists in the United States to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is an inherited form of diffuse-type gastric cancer and has pathogenic variants in the E-cadherin gene that are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer in individuals with HDGC is very high, and prophylactic total gastrectomy is usually advised. This article focuses on intestinal type cancer.

Epidemiology

Gastric cancer (proximal and distal gastric cancer combined) is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with 1,033,701 new cases and 782,685 deaths in 2018.2 Gastric cancer is subcategorized based on location (proximal [i.e., esophagogastric junctional, gastric cardia] and distal) and histology (intestinal and diffuse type), and each subtype is considered to have a distinct pathogenesis. Distal intestinal type gastric cancer is most commonly encountered in clinical practice. In this article, gastric cancer will signify distal intestinal type gastric cancer unless it is otherwise noted. In general, incidence rates are about twofold higher in men than in women. There is marked geographic variation in incidence rates, and the age-standardized incidence rates in eastern Asia (32.1 and 13.2, per 100,000) are approximately six times higher than those in northern America (5.6 and 2.8, per 100,000) in both men and women, respectively.2 Recent studies evaluating global trends in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer have demonstrated decreases worldwide.3-5 However, the degree of decrease in the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer varies substantially across geographic regions, reflecting the heterogeneous distribution of risk profiles. A comprehensive analysis of a U.S. population registry demonstrated a linear decrease in the incidence of gastric cancer in the United States (0.94% decrease per year between 2001 and 2015),6 though the annual percent change in the gastric cancer mortality in the United States was lower (around 2% decrease per year between 1980 and 2011) than in other countries.3Several population-based studies conducted in the United States have demonstrated that the incidence of gastric cancer varied by ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin, and the highest incidence was observed among Asian immigrants.7,8 A comprehensive meta-analysis examining the risk of gastric cancer in immigrants from high-incidence regions to low-incidence regions found a persistently higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality among immigrants.9 These results indicate that there are important risk factors such as environmental and dietary factors in addition to the traditionally considered risk factors including male gender, age, family history, and tobacco use. A survey conducted in an ethnically and culturally diverse U.S. city showed that gastroenterology providers demonstrated knowledge deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with increased risk of gastric cancer.10 Recognizing individualized risk profiles in higher-risk groups (e.g., immigrants from higher-incidence/prevalence regions) is important for optimizing management of gastric cancer in the United States.

Assessment and management of modifiable risk factors

Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen, is the most well-recognized risk factor for gastric cancer, particularly noncardia gastric cancer.11 Since a landmark longitudinal follow-up study in Japan demonstrated that people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop gastric cancer than those without H. pylori infection,12 accumulating evidence largely from Asian countries has shown that eradication of H. pylori is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer regardless of baseline risk.13 There are also data on the protective effect for gastric cancer of H. pylori eradication in asymptomatic individuals. Another meta-analysis of six international randomized control trials demonstrated a 34% relative risk reduction of gastric cancer occurrence in asymptomatic people (relative risk of developing gastric cancer was 0.66 in those who received eradication therapy compared with those with placebo or no treatment, 95% CI, 0.46-0.95).14 A U.S. practice guideline published after these meta-analyses recommends that all patients with a positive test indicating active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment and testing to prove eradication,15 though the recommendation was not purely intended to reduce the gastric cancer risk in U.S. population. Subsequently, a Department of Veterans Affairs cohort study added valuable insights from a U.S. experience to the body of evidence from other countries with higher prevalence. In this study of more than 370,000 patients with a history of H. pylori infection, the detection and successful eradication of H. pylori was associated with a 76% lower incidence of gastric cancer compared with people without H. pylori treatment.16 This study also provided insight into H. pylori treatment practice patterns. Of patients with a positive H. pylori test result (stool antigen, urea breath test, or pathology), approximately 75% were prescribed an eradication regimen and only 21% of those underwent eradication tests. A low rate (24%) of eradication testing was subsequently reported by the same group among U.S. patients regardless of gastric cancer risk profiles.17 The lesson from the aforementioned study is that treatment and eradication of H. pylori even among asymptomatic U.S. patients reduces the risk of subsequent gastric cancer. However, it may be difficult to generalize the results of this study given the nature of the Veterans Affairs cohort, and more data are required to justify the implementation of nationwide preventive H. pylori screening in the general U.S. population.

Smoking has been recognized as the other important risk factor. A study from the European prospective multicenter cohort demonstrated a significant association of cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk (HR for ever-smokers 1.45 [95% CI, 1.08-1.94], current-smokers in males 1.73 [95% CI, 1.06-2.83], and current smokers in females 1.87 [95% CI, 1.12-3.12], respectively) after adjustment for educational level, dietary consumption profiles, alcohol intake, and body mass index (BMI).18 A subsequent meta-analysis provided solid evidence of smoking as the important behavioral risk factor for gastric cancer.19 Smoking also predisposed to the development of proximal gastric cancer.20 Along with other cancers in the digestive system such as in the esophagus, colon and rectum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, a significant association of BMI and the risk of proximal gastric cancer (RR of the highest BMI category compared with normal BMI, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.3-2.5]) was reported, with positive dose-response relationships; however, the association was not sufficient for distal gastric cancer.21 There is also evidence to show a trend of greater alcohol consumption (>45 grams per day [about 3 drinks a day]) associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer.21 It has been thought that salt and salt-preserved food increase the risk of gastric cancer. It should be noted that the observational studies showing the associations were published from Asian countries where such foods were a substantial part of traditional diets (e.g., salted vegetables in Japan) and the incidence of gastric cancer is high. There is also a speculation that preserved foods may have been eaten in more underserved, low socioeconomic regions where refrigeration was not available and prevalence of H. pylori infection was higher. Except for documented inherited form of gastric cancer (e.g., HDGC or hereditary cancer syndromes), most gastric cancers are considered sporadic. A recent randomized study published from South Korea investigated a cohort of higher-risk asymptomatic patients with family history significant for gastric cancer. This study of 1,676 subjects with a median follow-up of 9.2 years showed that successful eradication of H. pylori in the first-degree relatives of those with gastric cancer significantly reduced the risk (HR 0.45 [95% CI, 0.21-0.94]) of developing gastric cancer.22 As previously discussed, in the United States where the prevalence of H. pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer are both lower than in some Asian countries, routine screening of asymptomatic individuals for H. pylori is not justified yet. There may be a role for screening individuals who are first-generation immigrants from areas of high gastric cancer incidence and also have a first-degree relative with gastric cancer.

Who should we consider high risk and offer screening EGD?

With available evidence to date, screening for gastric cancer in a general U.S. population is not recommended. However, it is important to acknowledge the aforementioned varying incidence of gastric cancer in the United States among ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. Immigrants from high-incidence regions maintain a higher risk of gastric cancer and related mortality even after migration to lower-incidence regions. The latter comprehensive study estimated that as many as 12.7 million people (29.4% of total U.S. immigrant population) have emigrated from higher-incidence regions including East Asian and some Central American countries.9 Indeed, an opportunistic nationwide gastric cancer screening program has been implemented in South Korea (beginning at age 40, biannually)23 and Japan (beginning at age 50, biannually).24 Two decision-analytic simulation studies have provided insight into the uncertainty about the cost effectiveness for potential targeted gastric cancer screening in higher-risk populations in the United States. One study demonstrated that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening for otherwise asymptomatic Asian American people (as well as Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks) at the time of screening colonoscopy at 50 years of age with continued endoscopic surveillance every 3 years was cost effective, only if gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM) or more advanced lesions were diagnosed at the index screening EGD.25 Previous studies analyzing the cost effectiveness for gastric cancer screening in the United States had the limitation of not stratifying according to race or ethnicity, or accounting for patients diagnosed with GIM. Subsequently, the same research group extended this model analysis and has published additional findings that this strategy is cost effective for each of the most prevalent Asian American ethnicities (Chinese, Filipino, Southeast Asian, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Americans) in the United States irrespective of sex.26 Although the authors raised a limitation that additional risk factors such as family history, tobacco use, or persistent H. pylori infection were not considered in the model because data regarding differentiated noncardia gastric cancer risk among Asian American ethnicities based on these risk factors are not available.

These two model analytic studies added valuable insights to the body of evidence that subsequent EGDs after the one-time bundled EGD is cost effective for higher-risk asymptomatic people in the United States, if the index screening EGD with gastric mucosal biopsies demonstrates at least GIM. Further population-based research to elucidate risk stratification among higher-risk people will provide a schema that could standardize management and resource allocation as well as increase the cost effectiveness of a gastric cancer screening program in the United States. The degree of risk of developing gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis varies among the reported studies.27-29 Although the benefit of endoscopic screening in patients with autoimmune gastritis has not been established, a single endoscopic evaluation should be recommended soon after the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis in order to identify prevalent neoplastic lesions.30

Practical consideration when we perform EGD for early gastric cancer screening

Identification of higher-risk patients should alert an endoscopist to observe mucosa with greater care with a lower threshold to biopsy any suspicious lesions. Preprocedural risk stratification for each individual before performing diagnostic EGD will improve early gastric cancer detection. While we perform EGD, detecting precursor lesions (atrophic gastritis and GIM) is as important as diagnosing an early gastric cancer. Screening and management of patients with precursor lesions (i.e., atrophic gastritis and GIM) is beyond the scope of this article, and this was published in a previous issue of the New Gastroenterologist. It is important to first grossly survey the entire gastric mucosa using high-definition while light (HDWL) endoscopy and screen for any focal irregular (raised or depressed) mucosal lesions. These lesions are often erythematous and should be examined carefully. Use of mucolytic and/or deforming agents (e.g., N-acetylcysteine or simethicone) is recommended for the improvement of visual clarity of gastric mucosa.31 Simethicone is widely used in the United States for colonoscopy and should also be available at the time of EGD for better gastric mucosal visibility. If irregular mucosal lesions are noted, this area should also be examined under narrowband imaging (NBI) in addition to HDWL. According to a simplified classification consisting of mucosal and vascular irregularity, NBI provides better mucosal surface morphology for diagnosis of early gastric cancer compared with HDWL, and a thorough examination of the surface characteristics is a prerequisite.32 This classification was further validated in a randomized control trial, and NBI increased sensitivity for the diagnosis of neoplasia compared with HDWL (92 % vs. 74 %).33 The majority of institutions in the United States have a newer-generation NBI (Olympus America, EVIS EXERA III video system, GIF-HQ190), which provides brighter endoscopic images to better characterize gastric neoplastic lesions. Once we recognize an area suspicious for neoplasia, we should describe the macroscopic features according to a classification system.

The Paris classification, one of the most widely recognized classification systems among U.S. gastroenterologists, is recommended for gastric neoplastic lesions.34Gastric neoplastic lesions with a “superficial” endoscopic appearance are classified as subtypes of “type 0.” The term “type 0” was chosen to distinguish the classification of “superficial” lesions from the Borrmann classification for “advanced” gastric tumors, which includes types 1 to 4. In the classification, a neoplastic lesion is called “superficial” when its endoscopic appearance suggests that the depth of penetration in the digestive wall is not more than into the submucosa (i.e., there is no infiltration of the muscularis propria). The distinctive characters of polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions are summarized in Table 1. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has steadily gained acceptance for the treatment of early gastric cancer in the United States. The American Gastroenterological Association recommended in the 2019 institutional updated clinical practice guideline that ESD should be considered the first-line therapy for visible, endoscopically resectable, superficial gastric neoplasia.35 This recommendation is further supported by the published data on efficacy and safety of ESD for early gastric neoplasia in a large multicenter cohort in the United States.36 For all suspicious lesions, irrespective of pathological neoplastic confirmation, referral to an experienced center for further evaluation and endoscopic management should be considered. Lastly, all patients with early gastric cancer should be evaluated for H. pylori infection and treated if the test is positive. Eradication of H. pylori is associated with a lower rate of metachronous gastric cancer,37 and treatment of H. pylori as secondary prevention is also recommended.

Conclusion

As summarized above, cumulative epidemiologic data consistently demonstrate that the incidence of gastric cancer in the U.S. varies according to ethnicity, immigrant status, and country of origin. New gastroenterologists will need to recognize individual risk profiles and identify people at higher risk for gastric cancer. Risk stratification before performing endoscopic evaluation will improve early gastric cancer detection and make noninvasive, effective therapies an option.

References

1. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer statistics. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html.

2. Bray F et al. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

3. Ferro A et al. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1330-44.

4. Luo G et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1333-44.

5. Arnold M et al. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1164-87.

6. Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-42.

7. Kim Y et al. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015066.

8. Kamineni A et al. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:77-83.

9. Pabla BS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:347-59.

10. Shah SC et al. Knowledge Gaps among Physicians Caring for Multiethnic Populations at Increased Gastric Cancer Risk. Gut Liver. 2018 Jan 15;12(1):38-45.

11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. IARC. July 7, 2019. 12. Uemura N et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-9.

13. Lee YC et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113-24.

14. Ford AC et al. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174.

15. Chey W et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-39.

16. Kumar S et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:527-36.

17. Kumar S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 6;S1542-3565(20)30436-5.

18. González CA et al. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:629-34.

19. Ladeiras-Lopes R et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689-701.

20. Cavaleiro-Pinto M et al. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375-87.

21. Lauby-Secretan B et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794-8.

22. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:427-36.

23. Kim BJ et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:736-41.

24. Hamashima C. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:278–86.

25. Saumoy M et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:648-60.

26. Shah SC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21:S1542-3565(20)30993-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.031.

27. Brinton LA et al. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:810-3.

28. Hsing AW et al. Cancer. 1993;71:745-50.

29. Schafer LW et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:444-8.

30. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8.

31. Chiu PWY et al. Gut. 2019;68:186-97.

32. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2012;44:236-46.

33. Pimentel-Nunes P et al. Endoscopy. 2016;48:723-30.

34. Participants in the Paris Workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43.

35. Draganov PV et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:16-25.

36. Ngamruengphong S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun 18;S1542-3565(20)30834-X. Online ahead of print.

37. Choi IJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085-95.

Dr. Tomizawa is a clinical assistant professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle.

Disruption of postpandemic world will precipitate innovation

When this editorial is published, we will know the results of the national election (hopefully) and whether there will be a smooth transition of power. We should know whether the Affordable Care Act will remain intact, and we will have indications about the impact of a COVID/flu combination. Health care will never be the same.

According to a recent Medscape survey, 62% of U.S. physicians saw a reduction of monthly income (12% saw a reduction of over 70%) in the first 6 months of this year. Almost a third of the physician workforce is contemplating retirement earlier than anticipated. As worrisome, according to a JAMA article (Aug 4, 2020;324:510-3) the United States saw a 35% increase in excess deaths because of non-COVID etiologies, an indication of health care deferral and avoidance. We all are scrambling to catch up and accommodate an enormous demand.

We are witnessing a “K” shaped recovery for both individuals and GI practices. If your health care is covered by Medicare, you own a mortgage-free home and your wealth is based on a balanced equity/bond portfolio, then all of your assets increased in value compared to last year’s peak valuations. For the other 90% of Americans, the recovery is modest, neutral, or more often nonexistent. Gastroenterologists who work in academic centers or large health systems did not lose income this year and were protected by billion-dollar credit lines and cash-on-hand accounts from robust days available to these entities. Independent practices (critically dependent on monthly cash flow) were decimated, furthering the trend towards consolidation, retirement, and acquisitions. With the new CMS E/M valuations we will see further reduction in procedural reimbursement.

However, disruption always precipitates innovation. Challenges are great but opportunities are clearly evident for those willing to risk.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

When this editorial is published, we will know the results of the national election (hopefully) and whether there will be a smooth transition of power. We should know whether the Affordable Care Act will remain intact, and we will have indications about the impact of a COVID/flu combination. Health care will never be the same.

According to a recent Medscape survey, 62% of U.S. physicians saw a reduction of monthly income (12% saw a reduction of over 70%) in the first 6 months of this year. Almost a third of the physician workforce is contemplating retirement earlier than anticipated. As worrisome, according to a JAMA article (Aug 4, 2020;324:510-3) the United States saw a 35% increase in excess deaths because of non-COVID etiologies, an indication of health care deferral and avoidance. We all are scrambling to catch up and accommodate an enormous demand.

We are witnessing a “K” shaped recovery for both individuals and GI practices. If your health care is covered by Medicare, you own a mortgage-free home and your wealth is based on a balanced equity/bond portfolio, then all of your assets increased in value compared to last year’s peak valuations. For the other 90% of Americans, the recovery is modest, neutral, or more often nonexistent. Gastroenterologists who work in academic centers or large health systems did not lose income this year and were protected by billion-dollar credit lines and cash-on-hand accounts from robust days available to these entities. Independent practices (critically dependent on monthly cash flow) were decimated, furthering the trend towards consolidation, retirement, and acquisitions. With the new CMS E/M valuations we will see further reduction in procedural reimbursement.

However, disruption always precipitates innovation. Challenges are great but opportunities are clearly evident for those willing to risk.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

When this editorial is published, we will know the results of the national election (hopefully) and whether there will be a smooth transition of power. We should know whether the Affordable Care Act will remain intact, and we will have indications about the impact of a COVID/flu combination. Health care will never be the same.

According to a recent Medscape survey, 62% of U.S. physicians saw a reduction of monthly income (12% saw a reduction of over 70%) in the first 6 months of this year. Almost a third of the physician workforce is contemplating retirement earlier than anticipated. As worrisome, according to a JAMA article (Aug 4, 2020;324:510-3) the United States saw a 35% increase in excess deaths because of non-COVID etiologies, an indication of health care deferral and avoidance. We all are scrambling to catch up and accommodate an enormous demand.

We are witnessing a “K” shaped recovery for both individuals and GI practices. If your health care is covered by Medicare, you own a mortgage-free home and your wealth is based on a balanced equity/bond portfolio, then all of your assets increased in value compared to last year’s peak valuations. For the other 90% of Americans, the recovery is modest, neutral, or more often nonexistent. Gastroenterologists who work in academic centers or large health systems did not lose income this year and were protected by billion-dollar credit lines and cash-on-hand accounts from robust days available to these entities. Independent practices (critically dependent on monthly cash flow) were decimated, furthering the trend towards consolidation, retirement, and acquisitions. With the new CMS E/M valuations we will see further reduction in procedural reimbursement.

However, disruption always precipitates innovation. Challenges are great but opportunities are clearly evident for those willing to risk.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

No lab monitoring needed in adolescents on dupilumab

, Michael J. Cork, MBBS, PhD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

These reassuring results from the ongoing LIBERTY AD PED-OLE study confirm that, as previously established in adults, no blood monitoring is required in adolescents on the monoclonal antibody, which inhibits signaling of interleukins-4 and -13, said Dr. Cork, professor of dermatology and head of Sheffield Dermatology Research at the University of Sheffield (England).

“The practical importance of this finding is that there are no other systemic drugs available that don’t require blood samples. Cyclosporine, methotrexate, and the others used for atopic dermatitis require a lot of blood monitoring, and they’re off-license anyway for use in children and adolescents,” he said in an interview.

Many pediatric patients are afraid of needles and have an intense dislike of blood draws. And in a pandemic, no one wants to come into the office for blood draws if they don’t need to.

“Blood draws are very different from the injection for dupilumab. Taking a blood sample is much more painful for children. The needle in the autoinjector is really, really tiny; you can hardly feel it, and with the autoinjector you can’t even see it,” noted Dr. Cork, who is both a pediatric and adult dermatologist.

This report from the ongoing LIBERTY AD PED-OLE study included 105 patients aged 12-17 years who completed 52 weeks on dupilumab (Dupixent) with assessments of hematologic and serum chemistry parameters at baseline and weeks 16 and 52.

“The results were anticipated, but we want to know the drug is safe in every age group. The immune system is different in different age groups, so we have to be really careful,” Dr. Cork said.

The clinical side-effect profile was the same as in adults, consisting mainly of mild conjunctivitis and injection-site reactions. It’s a much less problematic side effect picture than with the older drugs.

“We’re finding the conjunctivitis to be slightly less severe than in adults, maybe because we’ve learned from the first trials in adults and from clinical experience to use prophylactic therapy. There would be no child going on dupilumab now – and no adult – that I wouldn’t put on prophylactic eye drops with replacement tears. I start them 2 weeks before I start dupilumab,” the dermatologist explained.

He and others with extensive experience using the biologic agent also work closely with an ophthalmologist.

“If we see an eye problem before going on dupilumab we get an assessment and then ophthalmologic monitoring during treatment,” Dr. Cork said.