User login

Let side effects guide treatment choice for refractory OCD

Choosing the most effective treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder requires flexibility and agility on the part of clinicians, according to Wayne K. Goodman, MD.

“There are no data at this point to suggest that one SSRI is superior to another. It’s really dealer’s choice, and it has to do with really picking medications based upon side effects,” Dr. Goodman said at the Psychopharmacology Update, presented by Current Psychiatry and Global Academy for Medical Education. Clinicians can use family history as a guide, he noted, but pharmacogenetic testing has not been helpful in his experience for selection or dosing of an SSRI.

SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine, are one of two mainstays of treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The other drug class is serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which include medications such clomipramine. Cognitive-behavioral therapy options, such as Exposure and Response Prevention therapy, also has some, albeit limited, efficacy.

Meanwhile, Dr. Goodman said, antidepressant classes other than SRIs and SSRIs have not been effective in treating obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and some patients do not adhere well to cognitive-behavioral therapy, said Dr. Goodman, who is the D.C. and Irene Ellwood Professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Choosing the most effective treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder requires flexibility and agility on the part of clinicians, according to Wayne K. Goodman, MD.

“There are no data at this point to suggest that one SSRI is superior to another. It’s really dealer’s choice, and it has to do with really picking medications based upon side effects,” Dr. Goodman said at the Psychopharmacology Update, presented by Current Psychiatry and Global Academy for Medical Education. Clinicians can use family history as a guide, he noted, but pharmacogenetic testing has not been helpful in his experience for selection or dosing of an SSRI.

SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine, are one of two mainstays of treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The other drug class is serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which include medications such clomipramine. Cognitive-behavioral therapy options, such as Exposure and Response Prevention therapy, also has some, albeit limited, efficacy.

Meanwhile, Dr. Goodman said, antidepressant classes other than SRIs and SSRIs have not been effective in treating obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and some patients do not adhere well to cognitive-behavioral therapy, said Dr. Goodman, who is the D.C. and Irene Ellwood Professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Choosing the most effective treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder requires flexibility and agility on the part of clinicians, according to Wayne K. Goodman, MD.

“There are no data at this point to suggest that one SSRI is superior to another. It’s really dealer’s choice, and it has to do with really picking medications based upon side effects,” Dr. Goodman said at the Psychopharmacology Update, presented by Current Psychiatry and Global Academy for Medical Education. Clinicians can use family history as a guide, he noted, but pharmacogenetic testing has not been helpful in his experience for selection or dosing of an SSRI.

SSRIs, such as fluvoxamine, are one of two mainstays of treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The other drug class is serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which include medications such clomipramine. Cognitive-behavioral therapy options, such as Exposure and Response Prevention therapy, also has some, albeit limited, efficacy.

Meanwhile, Dr. Goodman said, antidepressant classes other than SRIs and SSRIs have not been effective in treating obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and some patients do not adhere well to cognitive-behavioral therapy, said Dr. Goodman, who is the D.C. and Irene Ellwood Professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

FROM PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

Maternal oxygen in labor: False reassurance?

False reassurance?

CASE Heart rate tracing suggests fetal distress

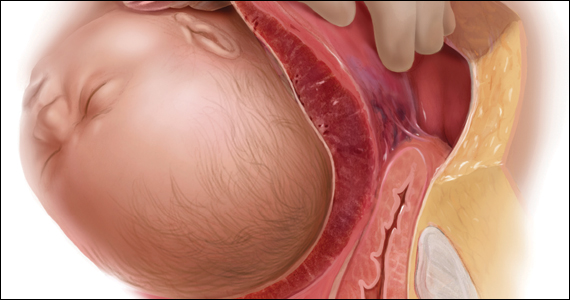

Ms. M. presents for elective induction of labor at 39 weeks’ gestation. During the course of her labor, a Category II fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing is noted, and maternal oxygen is administered as part of the intrauterine resuscitative efforts. Her infant ultimately was delivered vaginally with an arterial cord blood pH of 7.1 and Apgar scores of 5 and 7.

Should intrauterine resuscitation include maternal oxygen administration?

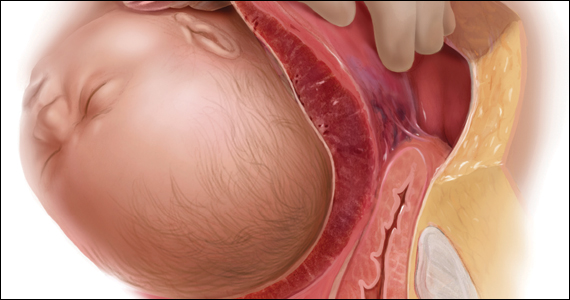

It is a common sight on labor and delivery: An FHR monitoring strip is noted to be a Category II tracing. There may be fetal tachycardia, late decelerations, or perhaps decreased variability. The nurse or physician goes to the laboring mother’s room, checks cervical dilation, changes the patient’s position, and puts an oxygen mask over her face.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists maternal oxygen administration, most commonly at 10 L/min via a nonrebreather face mask, as an intrauterine resuscitative measure for Category II or Category III FHR tracings.1 Maternal oxygen is used to treat abnormal FHR tracings in approximately half of all births in the United States.2 Despite these recommendations and the frequency of its use, however, evidence is limited that maternal oxygenation improves neonatal outcome. In fact, there is emerging evidence of potential harm.

Why use oxygen?

The use of maternal oxygen supplementation intuitively makes sense. We know that certain abnormalities in FHR tracings can signal fetal hypoxia. Left untreated, the hypoxia could lead to fetal acidemia and associated neonatal sequelae. Theoretically, the administration of maternal oxygen should lead to improved fetal oxygenation and improved fetal outcome. This is supported by studies from the 1960s that demonstrate improved FHR tracings after maternal oxygen administration.3

This idea was further supported by studies that demonstrated an increase in fetal oxygen levels when maternal oxygen is administered. Haydon and colleagues evaluated the administration of maternal oxygen in women with nonreassuring FHR tracings.4 Their data showed that maternal oxygen administration increased fetal oxygen as measured by fetal pulse oximetry. The lower the initial fetal oxygen levels prior to oxygen administration, the greater the increase.

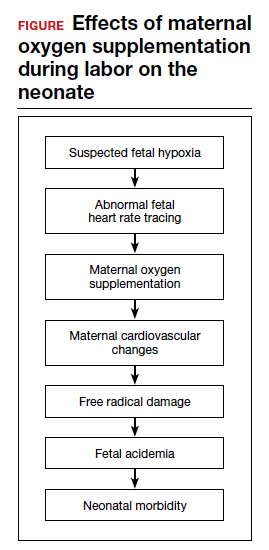

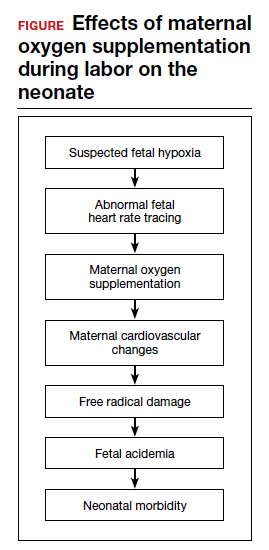

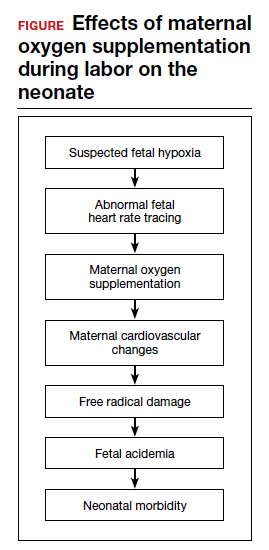

Despite these findings, evidence for improved neonatal outcomes is lacking.5 While heart rate tracings and fetal oxygen saturation may be improved with maternal oxygen supplementation, neonatal morbidity appears to remain unchanged (FIGURE). In fact, newer research suggests potential harm. Although an improved FHR tracing may be comforting to the clinician, the end result may be less so. Given these findings on maternal oxygen supplementation, it is time to break this practice habit.

Maternal cardiovascular effects

Most of the literature on maternal hyperoxygenation focuses on fetal response. Before examining the effects on the fetus, however, we must consider the effect on the mother. Cardiovascular changes occur during and after maternal oxygen administration that should be taken into account.

McHugh and colleagues measured the hemodynamic changes in 46 pregnant and 20 nonpregnant women before, immediately, and 10 minutes after a 30-minute period of high-flow oxygen administration.6 While there were no changes in the nonpregnant women’s parameters, in the pregnant women heart rate and stroke volume were decreased after oxygen administration. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance increased and did not return to baseline by 10 minutes postadministration.

Since the purpose of the maternal oxygen administration is to increase oxygen to the fetus, this decrease in cardiac output and increase in systemic vascular resistance is concerning. These results may negate the intended effect of increased oxygen delivery to the fetus.

Continue to: Maternal and fetal oxidative stress...

Maternal and fetal oxidative stress

Assuming that the abnormal FHR tracing in our case patient is actually due to fetal hypoxia, it would seem prudent to increase fetal oxygenation. However, fetal hyperoxygenation may lead to free radical damage that could worsen neonatal outcomes. Oxidative stress, which can be caused by both hypoxia and hyperoxia, can lead to endothelial and cell receptor damage. This is known to contribute to the cerebral damage of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

In a randomized trial, Khaw and colleagues measured lipid peroxidases as a “free radical footprint” in women undergoing elective cesarean delivery who were administered oxygen or room air.7 Maternal and fetal oxygen levels were higher in the oxygen-supplementation group, but lipid peroxidases also were elevated. This finding suggests that the excess oxygen results in free radical formation and potentially negative effects on the neonate.

Although maternal oxygen supplementation frequently is viewed as harmless, this research shows that free radical damage may occur in the mother as well.

Additional research shows that longer durations of oxygen administration are correlated with worsening neonatal outcomes. In a study of liberal versus indicated oxygen use, the average time was approximately 90 minutes.8 Use for longer than 176 minutes was associated with lower oxygen levels in fetal blood. A proposed mechanism for this response is placental vasoconstriction thought to protect the fetus from free radical damage.

Again, if the goal is to increase oxygenation, prolonged maternal oxygen supplementation appears to produce the opposite effect.

Fetal acidemia and neonatal morbidity

If a fetus with an abnormal FHR tracing is thought to be hypoxic or acidemic, adding the potentially harmful effects of free radicals could worsen this condition. This is exactly what Raghuraman and colleagues demonstrated in a large prospective cohort analysis.9 While there was no difference in neonatal morbidity between those receiving oxygen and those on room air, there was a significant difference among infants with acidemia and hyperoxia. Composite morbidity (mechanical ventilation, hypothermic therapy, meconium aspiration, and death) was significantly increased in neonates with both hyperoxia and acidemia compared with nonacidemic hyperoxic infants.9 This is further supported by reports of an increased need for neonatal resuscitation and a fourfold increase in umbilical cord pH of less than 7.2.10

While intrauterine and extrauterine life certainly differ, these findings align with the pediatric literature that supports neonatal resuscitation with room air rather than 100% oxygen.11 Additionally, the intrauterine environment is relatively hypoxic, which may make free radical damage more severe.

Continue to: Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic...

Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic

While high-flow oxygen by mask is not considered an aerosol-generating procedure according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, data are limited regarding the cleaning and filtering of oxygen. It is unknown if high-flow oxygen by mask increases the risk of infectious disease transmission to care providers. Therefore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, ACOG currently recommends against using supplemental oxygen for Category II and Category III tracings, since the benefits are not well established and the possibility of harm to providers may be increased.12 Oxygen supplementation still should be used in mothers with hypoxia.

Other intrauterine resuscitation options

Maternal oxygen administration does not appear beneficial for neonatal outcomes, but other methods can be used. An intravenous fluid bolus and lateral positioning of the mother, for example, are both associated with increased fetal oxygenation. Reducing uterine activity by discontinuing oxytocin or cervical ripening agents or by administering a tocolytic also can improve FHR abnormalities. Oxygen use should be reserved for patients with maternal hypoxia.

The bottom line

The liberal use of maternal oxygenation for the management of abnormal FHR tracings should be stopped. Clear evidence of its benefit is lacking, and the real possibility of fetal and maternal harm remains. This may be especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic. ●

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 116. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1232-1240.

- Hamel MS, Anderson BL, Rouse DJ. Oxygen for intrauterine resuscitation: of unproved benefit and potentially harmful. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:124-127.

- Althabe O, Schwarcz RL, Pose SV, et al. Effects on fetal heart rate and fetal pO2 of oxygen administration to the mother. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:858-870.

- Haydon ML, Gorenberg DM, Nageotte MP, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration on fetal pulse oximetry during labor in fetuses with nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:735-738.

- Fawole B, Hofmeyr GJ. Maternal oxygen administration for fetal distress. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD0000136.

- McHugh A, El-Khuffash A, Bussmann N, et al. Hyperoxygenation in pregnancy exerts a more profound effect on cardiovascular hemodynamics than is observed in the nonpregnant state. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:397.e1-397.e8.

- Khaw KS, Wang CC, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Effects of high inspired oxygen fraction during elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia on maternal and fetal oxygenation and lipid peroxidation. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:18-23.

- Watkins VY, Martin S, Macones GA, et al. The duration of intrapartum supplemental oxygen administration and umbilical cord oxygen content. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:440.e1-440.e7.

- Raghuraman N, Temming LA, Stout MJ, et al. Intrauterine hyperoxemia and risk of neonatal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:676-682.

- Thorp JA, Trobough T, Evans R, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration during the second stage of labor on umbilical cord blood gas values: a randomized controlled prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 pt 1):465-474.

- Rabi Y, Rabi D, Yee W. Room air resuscitation of the depressed newborn: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2007;72:353-363.

- COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Obstetrics. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-obstetrics. Accessed October 15, 2020.

CASE Heart rate tracing suggests fetal distress

Ms. M. presents for elective induction of labor at 39 weeks’ gestation. During the course of her labor, a Category II fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing is noted, and maternal oxygen is administered as part of the intrauterine resuscitative efforts. Her infant ultimately was delivered vaginally with an arterial cord blood pH of 7.1 and Apgar scores of 5 and 7.

Should intrauterine resuscitation include maternal oxygen administration?

It is a common sight on labor and delivery: An FHR monitoring strip is noted to be a Category II tracing. There may be fetal tachycardia, late decelerations, or perhaps decreased variability. The nurse or physician goes to the laboring mother’s room, checks cervical dilation, changes the patient’s position, and puts an oxygen mask over her face.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists maternal oxygen administration, most commonly at 10 L/min via a nonrebreather face mask, as an intrauterine resuscitative measure for Category II or Category III FHR tracings.1 Maternal oxygen is used to treat abnormal FHR tracings in approximately half of all births in the United States.2 Despite these recommendations and the frequency of its use, however, evidence is limited that maternal oxygenation improves neonatal outcome. In fact, there is emerging evidence of potential harm.

Why use oxygen?

The use of maternal oxygen supplementation intuitively makes sense. We know that certain abnormalities in FHR tracings can signal fetal hypoxia. Left untreated, the hypoxia could lead to fetal acidemia and associated neonatal sequelae. Theoretically, the administration of maternal oxygen should lead to improved fetal oxygenation and improved fetal outcome. This is supported by studies from the 1960s that demonstrate improved FHR tracings after maternal oxygen administration.3

This idea was further supported by studies that demonstrated an increase in fetal oxygen levels when maternal oxygen is administered. Haydon and colleagues evaluated the administration of maternal oxygen in women with nonreassuring FHR tracings.4 Their data showed that maternal oxygen administration increased fetal oxygen as measured by fetal pulse oximetry. The lower the initial fetal oxygen levels prior to oxygen administration, the greater the increase.

Despite these findings, evidence for improved neonatal outcomes is lacking.5 While heart rate tracings and fetal oxygen saturation may be improved with maternal oxygen supplementation, neonatal morbidity appears to remain unchanged (FIGURE). In fact, newer research suggests potential harm. Although an improved FHR tracing may be comforting to the clinician, the end result may be less so. Given these findings on maternal oxygen supplementation, it is time to break this practice habit.

Maternal cardiovascular effects

Most of the literature on maternal hyperoxygenation focuses on fetal response. Before examining the effects on the fetus, however, we must consider the effect on the mother. Cardiovascular changes occur during and after maternal oxygen administration that should be taken into account.

McHugh and colleagues measured the hemodynamic changes in 46 pregnant and 20 nonpregnant women before, immediately, and 10 minutes after a 30-minute period of high-flow oxygen administration.6 While there were no changes in the nonpregnant women’s parameters, in the pregnant women heart rate and stroke volume were decreased after oxygen administration. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance increased and did not return to baseline by 10 minutes postadministration.

Since the purpose of the maternal oxygen administration is to increase oxygen to the fetus, this decrease in cardiac output and increase in systemic vascular resistance is concerning. These results may negate the intended effect of increased oxygen delivery to the fetus.

Continue to: Maternal and fetal oxidative stress...

Maternal and fetal oxidative stress

Assuming that the abnormal FHR tracing in our case patient is actually due to fetal hypoxia, it would seem prudent to increase fetal oxygenation. However, fetal hyperoxygenation may lead to free radical damage that could worsen neonatal outcomes. Oxidative stress, which can be caused by both hypoxia and hyperoxia, can lead to endothelial and cell receptor damage. This is known to contribute to the cerebral damage of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

In a randomized trial, Khaw and colleagues measured lipid peroxidases as a “free radical footprint” in women undergoing elective cesarean delivery who were administered oxygen or room air.7 Maternal and fetal oxygen levels were higher in the oxygen-supplementation group, but lipid peroxidases also were elevated. This finding suggests that the excess oxygen results in free radical formation and potentially negative effects on the neonate.

Although maternal oxygen supplementation frequently is viewed as harmless, this research shows that free radical damage may occur in the mother as well.

Additional research shows that longer durations of oxygen administration are correlated with worsening neonatal outcomes. In a study of liberal versus indicated oxygen use, the average time was approximately 90 minutes.8 Use for longer than 176 minutes was associated with lower oxygen levels in fetal blood. A proposed mechanism for this response is placental vasoconstriction thought to protect the fetus from free radical damage.

Again, if the goal is to increase oxygenation, prolonged maternal oxygen supplementation appears to produce the opposite effect.

Fetal acidemia and neonatal morbidity

If a fetus with an abnormal FHR tracing is thought to be hypoxic or acidemic, adding the potentially harmful effects of free radicals could worsen this condition. This is exactly what Raghuraman and colleagues demonstrated in a large prospective cohort analysis.9 While there was no difference in neonatal morbidity between those receiving oxygen and those on room air, there was a significant difference among infants with acidemia and hyperoxia. Composite morbidity (mechanical ventilation, hypothermic therapy, meconium aspiration, and death) was significantly increased in neonates with both hyperoxia and acidemia compared with nonacidemic hyperoxic infants.9 This is further supported by reports of an increased need for neonatal resuscitation and a fourfold increase in umbilical cord pH of less than 7.2.10

While intrauterine and extrauterine life certainly differ, these findings align with the pediatric literature that supports neonatal resuscitation with room air rather than 100% oxygen.11 Additionally, the intrauterine environment is relatively hypoxic, which may make free radical damage more severe.

Continue to: Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic...

Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic

While high-flow oxygen by mask is not considered an aerosol-generating procedure according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, data are limited regarding the cleaning and filtering of oxygen. It is unknown if high-flow oxygen by mask increases the risk of infectious disease transmission to care providers. Therefore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, ACOG currently recommends against using supplemental oxygen for Category II and Category III tracings, since the benefits are not well established and the possibility of harm to providers may be increased.12 Oxygen supplementation still should be used in mothers with hypoxia.

Other intrauterine resuscitation options

Maternal oxygen administration does not appear beneficial for neonatal outcomes, but other methods can be used. An intravenous fluid bolus and lateral positioning of the mother, for example, are both associated with increased fetal oxygenation. Reducing uterine activity by discontinuing oxytocin or cervical ripening agents or by administering a tocolytic also can improve FHR abnormalities. Oxygen use should be reserved for patients with maternal hypoxia.

The bottom line

The liberal use of maternal oxygenation for the management of abnormal FHR tracings should be stopped. Clear evidence of its benefit is lacking, and the real possibility of fetal and maternal harm remains. This may be especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic. ●

CASE Heart rate tracing suggests fetal distress

Ms. M. presents for elective induction of labor at 39 weeks’ gestation. During the course of her labor, a Category II fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing is noted, and maternal oxygen is administered as part of the intrauterine resuscitative efforts. Her infant ultimately was delivered vaginally with an arterial cord blood pH of 7.1 and Apgar scores of 5 and 7.

Should intrauterine resuscitation include maternal oxygen administration?

It is a common sight on labor and delivery: An FHR monitoring strip is noted to be a Category II tracing. There may be fetal tachycardia, late decelerations, or perhaps decreased variability. The nurse or physician goes to the laboring mother’s room, checks cervical dilation, changes the patient’s position, and puts an oxygen mask over her face.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists maternal oxygen administration, most commonly at 10 L/min via a nonrebreather face mask, as an intrauterine resuscitative measure for Category II or Category III FHR tracings.1 Maternal oxygen is used to treat abnormal FHR tracings in approximately half of all births in the United States.2 Despite these recommendations and the frequency of its use, however, evidence is limited that maternal oxygenation improves neonatal outcome. In fact, there is emerging evidence of potential harm.

Why use oxygen?

The use of maternal oxygen supplementation intuitively makes sense. We know that certain abnormalities in FHR tracings can signal fetal hypoxia. Left untreated, the hypoxia could lead to fetal acidemia and associated neonatal sequelae. Theoretically, the administration of maternal oxygen should lead to improved fetal oxygenation and improved fetal outcome. This is supported by studies from the 1960s that demonstrate improved FHR tracings after maternal oxygen administration.3

This idea was further supported by studies that demonstrated an increase in fetal oxygen levels when maternal oxygen is administered. Haydon and colleagues evaluated the administration of maternal oxygen in women with nonreassuring FHR tracings.4 Their data showed that maternal oxygen administration increased fetal oxygen as measured by fetal pulse oximetry. The lower the initial fetal oxygen levels prior to oxygen administration, the greater the increase.

Despite these findings, evidence for improved neonatal outcomes is lacking.5 While heart rate tracings and fetal oxygen saturation may be improved with maternal oxygen supplementation, neonatal morbidity appears to remain unchanged (FIGURE). In fact, newer research suggests potential harm. Although an improved FHR tracing may be comforting to the clinician, the end result may be less so. Given these findings on maternal oxygen supplementation, it is time to break this practice habit.

Maternal cardiovascular effects

Most of the literature on maternal hyperoxygenation focuses on fetal response. Before examining the effects on the fetus, however, we must consider the effect on the mother. Cardiovascular changes occur during and after maternal oxygen administration that should be taken into account.

McHugh and colleagues measured the hemodynamic changes in 46 pregnant and 20 nonpregnant women before, immediately, and 10 minutes after a 30-minute period of high-flow oxygen administration.6 While there were no changes in the nonpregnant women’s parameters, in the pregnant women heart rate and stroke volume were decreased after oxygen administration. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance increased and did not return to baseline by 10 minutes postadministration.

Since the purpose of the maternal oxygen administration is to increase oxygen to the fetus, this decrease in cardiac output and increase in systemic vascular resistance is concerning. These results may negate the intended effect of increased oxygen delivery to the fetus.

Continue to: Maternal and fetal oxidative stress...

Maternal and fetal oxidative stress

Assuming that the abnormal FHR tracing in our case patient is actually due to fetal hypoxia, it would seem prudent to increase fetal oxygenation. However, fetal hyperoxygenation may lead to free radical damage that could worsen neonatal outcomes. Oxidative stress, which can be caused by both hypoxia and hyperoxia, can lead to endothelial and cell receptor damage. This is known to contribute to the cerebral damage of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

In a randomized trial, Khaw and colleagues measured lipid peroxidases as a “free radical footprint” in women undergoing elective cesarean delivery who were administered oxygen or room air.7 Maternal and fetal oxygen levels were higher in the oxygen-supplementation group, but lipid peroxidases also were elevated. This finding suggests that the excess oxygen results in free radical formation and potentially negative effects on the neonate.

Although maternal oxygen supplementation frequently is viewed as harmless, this research shows that free radical damage may occur in the mother as well.

Additional research shows that longer durations of oxygen administration are correlated with worsening neonatal outcomes. In a study of liberal versus indicated oxygen use, the average time was approximately 90 minutes.8 Use for longer than 176 minutes was associated with lower oxygen levels in fetal blood. A proposed mechanism for this response is placental vasoconstriction thought to protect the fetus from free radical damage.

Again, if the goal is to increase oxygenation, prolonged maternal oxygen supplementation appears to produce the opposite effect.

Fetal acidemia and neonatal morbidity

If a fetus with an abnormal FHR tracing is thought to be hypoxic or acidemic, adding the potentially harmful effects of free radicals could worsen this condition. This is exactly what Raghuraman and colleagues demonstrated in a large prospective cohort analysis.9 While there was no difference in neonatal morbidity between those receiving oxygen and those on room air, there was a significant difference among infants with acidemia and hyperoxia. Composite morbidity (mechanical ventilation, hypothermic therapy, meconium aspiration, and death) was significantly increased in neonates with both hyperoxia and acidemia compared with nonacidemic hyperoxic infants.9 This is further supported by reports of an increased need for neonatal resuscitation and a fourfold increase in umbilical cord pH of less than 7.2.10

While intrauterine and extrauterine life certainly differ, these findings align with the pediatric literature that supports neonatal resuscitation with room air rather than 100% oxygen.11 Additionally, the intrauterine environment is relatively hypoxic, which may make free radical damage more severe.

Continue to: Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic...

Oxygen use during the COVID-19 pandemic

While high-flow oxygen by mask is not considered an aerosol-generating procedure according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, data are limited regarding the cleaning and filtering of oxygen. It is unknown if high-flow oxygen by mask increases the risk of infectious disease transmission to care providers. Therefore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, ACOG currently recommends against using supplemental oxygen for Category II and Category III tracings, since the benefits are not well established and the possibility of harm to providers may be increased.12 Oxygen supplementation still should be used in mothers with hypoxia.

Other intrauterine resuscitation options

Maternal oxygen administration does not appear beneficial for neonatal outcomes, but other methods can be used. An intravenous fluid bolus and lateral positioning of the mother, for example, are both associated with increased fetal oxygenation. Reducing uterine activity by discontinuing oxytocin or cervical ripening agents or by administering a tocolytic also can improve FHR abnormalities. Oxygen use should be reserved for patients with maternal hypoxia.

The bottom line

The liberal use of maternal oxygenation for the management of abnormal FHR tracings should be stopped. Clear evidence of its benefit is lacking, and the real possibility of fetal and maternal harm remains. This may be especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic. ●

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 116. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1232-1240.

- Hamel MS, Anderson BL, Rouse DJ. Oxygen for intrauterine resuscitation: of unproved benefit and potentially harmful. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:124-127.

- Althabe O, Schwarcz RL, Pose SV, et al. Effects on fetal heart rate and fetal pO2 of oxygen administration to the mother. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:858-870.

- Haydon ML, Gorenberg DM, Nageotte MP, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration on fetal pulse oximetry during labor in fetuses with nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:735-738.

- Fawole B, Hofmeyr GJ. Maternal oxygen administration for fetal distress. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD0000136.

- McHugh A, El-Khuffash A, Bussmann N, et al. Hyperoxygenation in pregnancy exerts a more profound effect on cardiovascular hemodynamics than is observed in the nonpregnant state. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:397.e1-397.e8.

- Khaw KS, Wang CC, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Effects of high inspired oxygen fraction during elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia on maternal and fetal oxygenation and lipid peroxidation. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:18-23.

- Watkins VY, Martin S, Macones GA, et al. The duration of intrapartum supplemental oxygen administration and umbilical cord oxygen content. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:440.e1-440.e7.

- Raghuraman N, Temming LA, Stout MJ, et al. Intrauterine hyperoxemia and risk of neonatal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:676-682.

- Thorp JA, Trobough T, Evans R, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration during the second stage of labor on umbilical cord blood gas values: a randomized controlled prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 pt 1):465-474.

- Rabi Y, Rabi D, Yee W. Room air resuscitation of the depressed newborn: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2007;72:353-363.

- COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Obstetrics. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-obstetrics. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 116. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1232-1240.

- Hamel MS, Anderson BL, Rouse DJ. Oxygen for intrauterine resuscitation: of unproved benefit and potentially harmful. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:124-127.

- Althabe O, Schwarcz RL, Pose SV, et al. Effects on fetal heart rate and fetal pO2 of oxygen administration to the mother. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:858-870.

- Haydon ML, Gorenberg DM, Nageotte MP, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration on fetal pulse oximetry during labor in fetuses with nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:735-738.

- Fawole B, Hofmeyr GJ. Maternal oxygen administration for fetal distress. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD0000136.

- McHugh A, El-Khuffash A, Bussmann N, et al. Hyperoxygenation in pregnancy exerts a more profound effect on cardiovascular hemodynamics than is observed in the nonpregnant state. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:397.e1-397.e8.

- Khaw KS, Wang CC, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Effects of high inspired oxygen fraction during elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia on maternal and fetal oxygenation and lipid peroxidation. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:18-23.

- Watkins VY, Martin S, Macones GA, et al. The duration of intrapartum supplemental oxygen administration and umbilical cord oxygen content. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:440.e1-440.e7.

- Raghuraman N, Temming LA, Stout MJ, et al. Intrauterine hyperoxemia and risk of neonatal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:676-682.

- Thorp JA, Trobough T, Evans R, et al. The effect of maternal oxygen administration during the second stage of labor on umbilical cord blood gas values: a randomized controlled prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 pt 1):465-474.

- Rabi Y, Rabi D, Yee W. Room air resuscitation of the depressed newborn: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2007;72:353-363.

- COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Obstetrics. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/physician-faqs/covid-19-faqs-for-ob-gyns-obstetrics. Accessed October 15, 2020.

False reassurance?

False reassurance?

Early results ‘encouraging’ for CAR NKT cells in neuroblastoma

, according to results of an ongoing phase 1 trial.

In one of three patients treated thus far, the CAR NKT cells induced an objective response with regression of a metastatic bone lesion.

Andras Heczey, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues reported outcomes for the first three patients in Nature Medicine.

The three boys – two 12-year-olds and one 6-year-old – had relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma.

NKT cells were collected from the patients, then genetically engineered to express a CAR to recognize the GD2-ganglioside expressed in neuroblastomas and also to express interleukin-15, which supports NKT cell survival. The cells were expanded and reinfused back into the patients.

The initial results suggest that CAR NKT cells can be used safely to treat neuroblastomas and perhaps other solid tumors, investigators said.

‘A significant advance’ if confirmed

Treating solid tumors with CAR T cells has been a challenge, in part because of inefficient trafficking into tumors.

However, NKT cells naturally migrate to tumors in response to tumor-derived chemokines, Dr. Heczey and colleagues noted. NKT cells kill macrophages associated with tumor growth and promote NK- and T-cell–mediated antitumor responses.

“We decided to leverage this intrinsic property of NKTs and to arm them with an additional bullet – the so-called CAR – to further potentiate their capacity to destroy the tumor,” investigator Gianpietro Dotti, MD, of the University of North Carolina Lindberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, said in a press release.

Overall, the “results are very encouraging and, if confirmed in a larger cohort of patients, present a significant advance in the cell therapy field for solid tumors,” said CAR-T researcher Stephen Gottschalk, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., when asked for comment.

Treatment, safety, and efficacy details

NKT cells are infrequent in human peripheral blood, so the investigators stimulated the NKT cells collected from patients with alpha-galactosylceramide–pulsed irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The final products reached a mean NKT cell purity of 95%. The proportion of cells positive for the GD2-CAR ranged from 20% to 70% across the three patients.

After lymphodepletion with cyclophosphamide/fludarabine, the patients were infused with 3 × 106 CAR NKT cells/m2.

The cells were well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. There were grade 3/4 adverse events, but they occurred before CAR NKT-cell infusion and were thought to be related to lymphodepletion.

NKT-cell frequency and absolute numbers increased in the peripheral blood over baseline and remained elevated at the week 4 assessment.

Two patients had stable disease at 4 weeks, but one had a partial response and a change in Curie score from 2 to 1. The patient’s SPECT- and MIBG-merged scans “revealed a dramatic reduction in the size and MIBG uptake of a bone metastasis. The patient consequently received salvage therapy and achieved a complete response that lasted approximately 6 months,” the investigators noted.

The team found higher percentages of CAR NKT cells in primary tumor and metastatic bone marrow biopsies than in peripheral blood. A high percentage of CAR NKT cells from the tumor specimen, but only a small fraction from the bone metastasis, expressed the GD2-CAR.

This research was funded by Kuur Therapeutics, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, the American Cancer Society, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer Foundation, and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Heczey, Dr. Dotti, and two other researchers are coinventors on pending patent applications for NKT cells in cancer immunotherapy that have been licensed to Kuur Therapeutics for commercial development. Dr. Gottschalk has patent applications in the fields of T-cell and/or gene therapy for cancer. He has relationships with TESSA Therapeutics, Immatics, and Tidal.

SOURCE: Heczey A et al. Nat Med. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1074-2.

, according to results of an ongoing phase 1 trial.

In one of three patients treated thus far, the CAR NKT cells induced an objective response with regression of a metastatic bone lesion.

Andras Heczey, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues reported outcomes for the first three patients in Nature Medicine.

The three boys – two 12-year-olds and one 6-year-old – had relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma.

NKT cells were collected from the patients, then genetically engineered to express a CAR to recognize the GD2-ganglioside expressed in neuroblastomas and also to express interleukin-15, which supports NKT cell survival. The cells were expanded and reinfused back into the patients.

The initial results suggest that CAR NKT cells can be used safely to treat neuroblastomas and perhaps other solid tumors, investigators said.

‘A significant advance’ if confirmed

Treating solid tumors with CAR T cells has been a challenge, in part because of inefficient trafficking into tumors.

However, NKT cells naturally migrate to tumors in response to tumor-derived chemokines, Dr. Heczey and colleagues noted. NKT cells kill macrophages associated with tumor growth and promote NK- and T-cell–mediated antitumor responses.

“We decided to leverage this intrinsic property of NKTs and to arm them with an additional bullet – the so-called CAR – to further potentiate their capacity to destroy the tumor,” investigator Gianpietro Dotti, MD, of the University of North Carolina Lindberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, said in a press release.

Overall, the “results are very encouraging and, if confirmed in a larger cohort of patients, present a significant advance in the cell therapy field for solid tumors,” said CAR-T researcher Stephen Gottschalk, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., when asked for comment.

Treatment, safety, and efficacy details

NKT cells are infrequent in human peripheral blood, so the investigators stimulated the NKT cells collected from patients with alpha-galactosylceramide–pulsed irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The final products reached a mean NKT cell purity of 95%. The proportion of cells positive for the GD2-CAR ranged from 20% to 70% across the three patients.

After lymphodepletion with cyclophosphamide/fludarabine, the patients were infused with 3 × 106 CAR NKT cells/m2.

The cells were well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. There were grade 3/4 adverse events, but they occurred before CAR NKT-cell infusion and were thought to be related to lymphodepletion.

NKT-cell frequency and absolute numbers increased in the peripheral blood over baseline and remained elevated at the week 4 assessment.

Two patients had stable disease at 4 weeks, but one had a partial response and a change in Curie score from 2 to 1. The patient’s SPECT- and MIBG-merged scans “revealed a dramatic reduction in the size and MIBG uptake of a bone metastasis. The patient consequently received salvage therapy and achieved a complete response that lasted approximately 6 months,” the investigators noted.

The team found higher percentages of CAR NKT cells in primary tumor and metastatic bone marrow biopsies than in peripheral blood. A high percentage of CAR NKT cells from the tumor specimen, but only a small fraction from the bone metastasis, expressed the GD2-CAR.

This research was funded by Kuur Therapeutics, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, the American Cancer Society, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer Foundation, and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Heczey, Dr. Dotti, and two other researchers are coinventors on pending patent applications for NKT cells in cancer immunotherapy that have been licensed to Kuur Therapeutics for commercial development. Dr. Gottschalk has patent applications in the fields of T-cell and/or gene therapy for cancer. He has relationships with TESSA Therapeutics, Immatics, and Tidal.

SOURCE: Heczey A et al. Nat Med. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1074-2.

, according to results of an ongoing phase 1 trial.

In one of three patients treated thus far, the CAR NKT cells induced an objective response with regression of a metastatic bone lesion.

Andras Heczey, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues reported outcomes for the first three patients in Nature Medicine.

The three boys – two 12-year-olds and one 6-year-old – had relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma.

NKT cells were collected from the patients, then genetically engineered to express a CAR to recognize the GD2-ganglioside expressed in neuroblastomas and also to express interleukin-15, which supports NKT cell survival. The cells were expanded and reinfused back into the patients.

The initial results suggest that CAR NKT cells can be used safely to treat neuroblastomas and perhaps other solid tumors, investigators said.

‘A significant advance’ if confirmed

Treating solid tumors with CAR T cells has been a challenge, in part because of inefficient trafficking into tumors.

However, NKT cells naturally migrate to tumors in response to tumor-derived chemokines, Dr. Heczey and colleagues noted. NKT cells kill macrophages associated with tumor growth and promote NK- and T-cell–mediated antitumor responses.

“We decided to leverage this intrinsic property of NKTs and to arm them with an additional bullet – the so-called CAR – to further potentiate their capacity to destroy the tumor,” investigator Gianpietro Dotti, MD, of the University of North Carolina Lindberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, said in a press release.

Overall, the “results are very encouraging and, if confirmed in a larger cohort of patients, present a significant advance in the cell therapy field for solid tumors,” said CAR-T researcher Stephen Gottschalk, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., when asked for comment.

Treatment, safety, and efficacy details

NKT cells are infrequent in human peripheral blood, so the investigators stimulated the NKT cells collected from patients with alpha-galactosylceramide–pulsed irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The final products reached a mean NKT cell purity of 95%. The proportion of cells positive for the GD2-CAR ranged from 20% to 70% across the three patients.

After lymphodepletion with cyclophosphamide/fludarabine, the patients were infused with 3 × 106 CAR NKT cells/m2.

The cells were well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities. There were grade 3/4 adverse events, but they occurred before CAR NKT-cell infusion and were thought to be related to lymphodepletion.

NKT-cell frequency and absolute numbers increased in the peripheral blood over baseline and remained elevated at the week 4 assessment.

Two patients had stable disease at 4 weeks, but one had a partial response and a change in Curie score from 2 to 1. The patient’s SPECT- and MIBG-merged scans “revealed a dramatic reduction in the size and MIBG uptake of a bone metastasis. The patient consequently received salvage therapy and achieved a complete response that lasted approximately 6 months,” the investigators noted.

The team found higher percentages of CAR NKT cells in primary tumor and metastatic bone marrow biopsies than in peripheral blood. A high percentage of CAR NKT cells from the tumor specimen, but only a small fraction from the bone metastasis, expressed the GD2-CAR.

This research was funded by Kuur Therapeutics, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, the American Cancer Society, Cookies for Kids’ Cancer Foundation, and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Heczey, Dr. Dotti, and two other researchers are coinventors on pending patent applications for NKT cells in cancer immunotherapy that have been licensed to Kuur Therapeutics for commercial development. Dr. Gottschalk has patent applications in the fields of T-cell and/or gene therapy for cancer. He has relationships with TESSA Therapeutics, Immatics, and Tidal.

SOURCE: Heczey A et al. Nat Med. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1074-2.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Syphilis: Cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening

CASE Pregnant woman with positive Treponema pallidum antibody test

A 30-year-old primigravida at 10 weeks and 4 days of gestation by her last menstrual period presents to your office for her initial prenatal visit. She expresses no concerns. You order the standard set of laboratory tests, including a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening panel. Consistent with your institution’s use of the reverse algorithm for syphilis screening, you obtain a Treponema pallidum antibody test, which reflexes to the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Three days later, you receive a notification that this patient’s T pallidum antibody result was positive, followed by negative RPR test results. The follow-up T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test also was negative. Given these findings, you consider:

- What is the correct interpretation of the patient’s sequence of test results?

- Is she infected, and does she require treatment?

Meet our perpetrator

Syphilis has plagued society since the late 15th century, although its causative agent, the spirochete T pallidum, was not recognized until 1905.1,2T pallidum bacteria are transmitted via sexual contact, as well as through vertical transmission during pregnancy or delivery. Infection with syphilis is reported in 50% to 60% of sexual partners after a single exposure to an infected individual with early syphilis, and the mean incubation period is 21 days.3T pallidum can cross the placenta and infect a fetus as early as the sixth week of gestation.3 Congenital syphilis infections occur in the neonates of 50% to 80% of women with untreated primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis infections; maternal syphilis is associated with a 21% increased risk of stillbirth, a 6% increased risk of preterm delivery, and a 9% increased risk of neonatal death.4,5 Additionally, syphilis infection is associated with a high risk of HIV infection, as well as coinfection with other STIs.1

Given the highly infective nature of T pallidum, as well as the severity of the potential consequences of infection for both mothers and babies, primary prevention, education of at-risk populations, and early recognition of clinical features of syphilis infection are of utmost importance in preventing morbidity and mortality. In this article, we review the epidemiology and extensive clinical manifestations of syphilis, as well as current screening recommendations and treatment for pregnant women.

The extent of the problem today

Although US rates of syphilis have ebbed and flowed for the past several decades, the current incidence has grown exponentially in recent years, with the number of cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) increasing by 71% from 2014 to 2018.6 During this time period, reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in women more than doubled (172.7% and 165.4%, respectively) according to CDC data, accompanied by a parallel rise in reported cases of congenital syphilis in both live and stillborn infants.6 In 2018, the CDC reported a national rate of congenital syphilis of 33.1 cases per 100,000 live births, a 39.7% rise compared with data from 2017.6

Those most at risk. Risk factors for syphilis infection include age younger than 30 years, low socioeconomic status, substance abuse, HIV infection, concurrent STIs, and high-risk sexual activity (sex with multiple high-risk partners).3 Additionally, reported rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections, as well as congenital syphilis infections, are more elevated among women who identify as Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Hispanic.6 Congenital infections in the United States are correlated with a lack of prenatal care, which has been similarly linked with racial and socioeconomic disparities, as well as with untreated mental health and substance use disorders and recent immigration to the United States.5,7

Continue to: The many phases of syphilis...

The many phases of syphilis

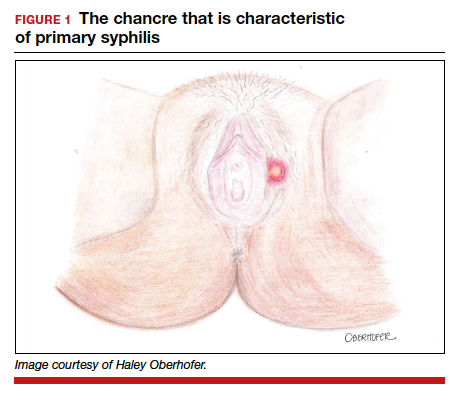

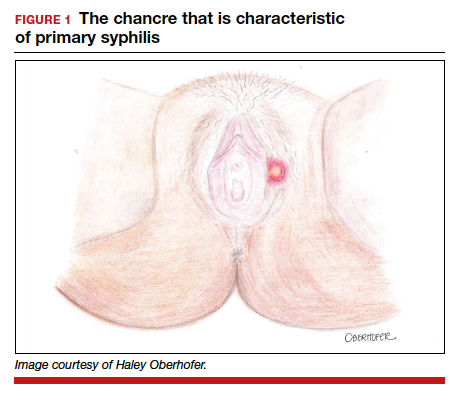

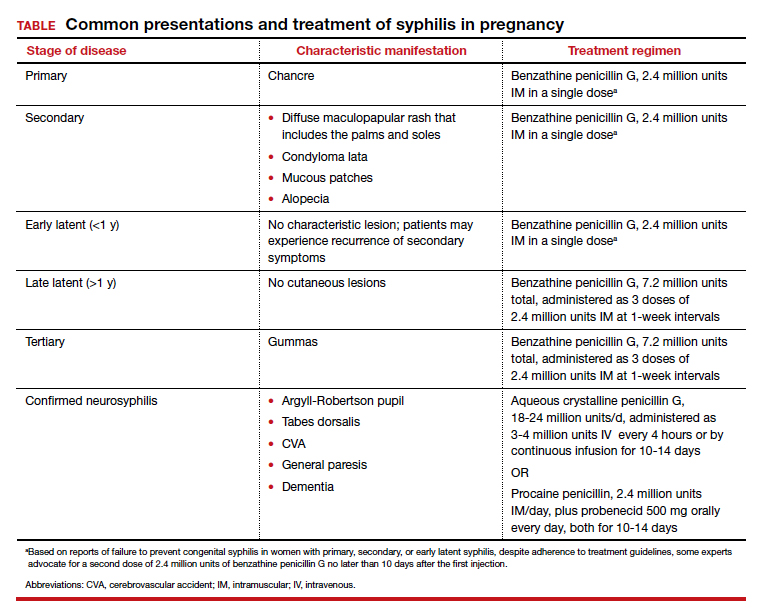

The characteristic lesion of primary syphilis is a chancre, which is a painless, ulcerative lesion with raised borders and a clean, indurated base appearing at the site of spirochete entry (FIGURE 1). Chancres most commonly appear in the genital area, with the most frequent sites in females being within the vaginal canal or on the cervix. Primary chancres tend to heal spontaneously within 3 to 6 weeks, even without treatment, and frequently are accompanied by painless inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given that the most common chancre sites are not immediately apparent, primary infections in women often go undetected.3 In fact, it is essential for clinicians to recognize that, in our routine practice, most patients with syphilis will not be symptomatic at all, and the diagnosis will only be made by serologic screening.

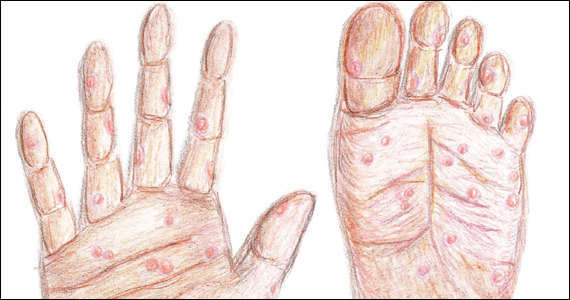

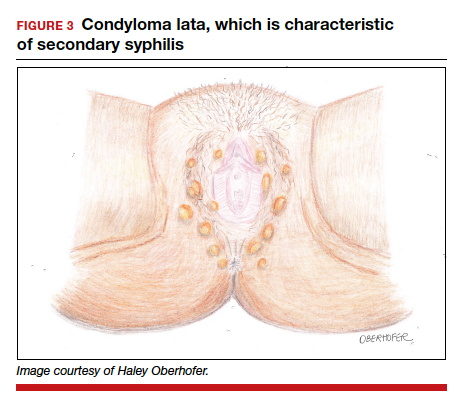

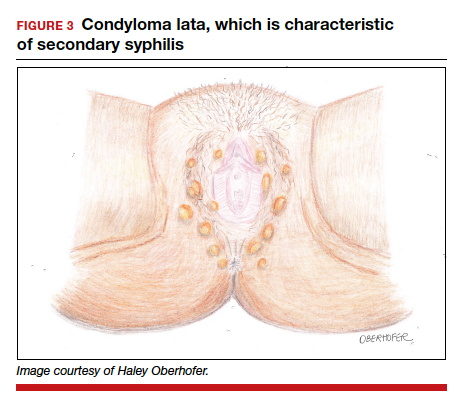

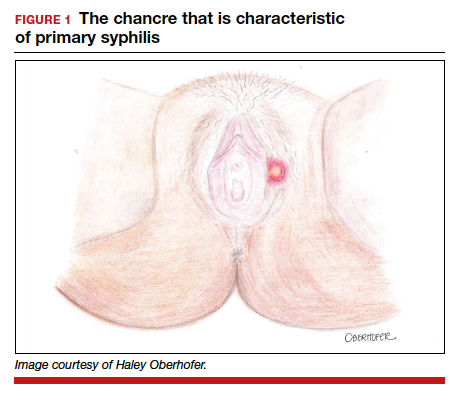

Following resolution of the primary phase, the patient may enter the secondary stage of T pallidum infection. During this stage, spirochetes may disseminate throughout the bloodstream to infect all major organ systems. The principal manifestations of secondary syphilis include a diffuse maculopapular rash that begins on the trunk and proximal extremities and spreads to include the palms and soles (FIGURE 2); mucosal lesions, such as mucous patches and condyloma lata (FIGURE 3); nonscarring alopecia; periostitis; generalized lymphadenopathy; and, in some cases, hepatitis or nephritis.1,3

Secondary syphilis usually clears within 2 to 6 weeks, with the patient then entering the early latent stage of syphilis. During this period, up to 25% of patients are subject to flares of secondary syphilitic lesions but otherwise are asymptomatic.1,3,4 These recurrences tend to occur within 1 year, hence the distinction between early and late latent stages. Once a year has passed, patients are not contagious by sexual transmission and are unlikely to suffer a relapse of secondary symptoms.1,3 However, late latent syphilis is characterized by periods of intermittent bacteremia that allow for seeding of the placenta and infection in about 10% of fetuses.5

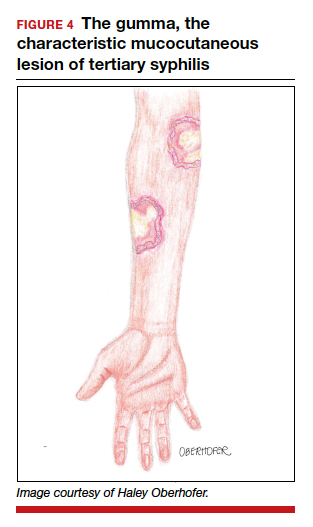

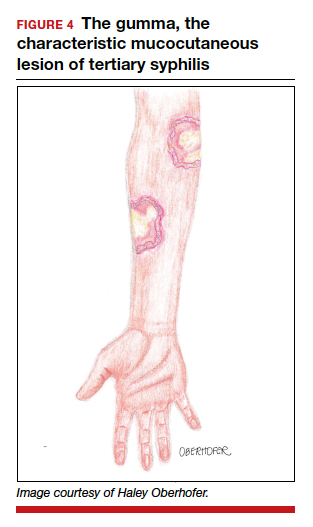

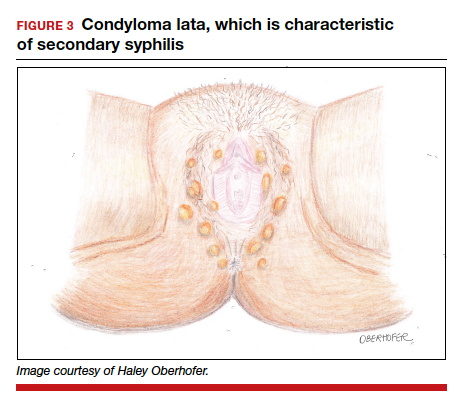

Untreated, about 40% of patients will progress to the tertiary stage of syphilis, which is characterized by gummas affecting the skin and mucous membranes (FIGURE 4) and cardiovascular manifestations including arterial aneurysms and aortic insufficiency.3

Neurologic manifestations of syphilis may arise during any of the above stages, though the most characteristic manifestations tend to appear decades after the primary infection. Early neurosyphilis may present as meningitis, with or without concomitant ocular syphilis (uveitis, retinitis) and/or as otic syphilis (hearing loss, persistent tinnitus).1,5 Patients with late (tertiary) neurosyphilis tend to exhibit meningovascular symptoms similar to stroke (aphasia, hemiplegia, seizures) and/or parenchymal effects such as general paresis. Tabes dorsalis (manifestations of which include urinary and rectal incontinence, lightning pains, and ataxia) is a late-onset manifestation.1,3

Congenital syphilis can be subdivided into an early and late stage. The first stage, in which clinical findings occur within the first 2 years of life, commonly features a desquamating rash, hepatomegaly, and rhinitis. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, periostitis, and osteomyelitis also have been documented.5 Of note, two-thirds of infants are asymptomatic at birth and may not develop such clinical manifestations for 3 to 8 weeks.3 If untreated, early congenital infection may progress to late manifestations, such as Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, interstitial keratitis, deafness, saddle nose, saber shins, and such neurologic abnormalities as developmental delay and general paresis.3

Continue to: Prenatal screening and diagnosis...

Prenatal screening and diagnosis

Current recommendations issued by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that all pregnant women should be screened for syphilis infection at their first presentation to care, with repeat screening between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation and at birth, for women living in areas with a high prevalence of syphilis and/or with any of the aforementioned risk factors.3,5 Given that providers may be unfamiliar with the prevalence of syphilis in their area, and that patients may acquire or develop an infection later on in their pregnancy, researchers have begun to investigate the feasibility of universal third-trimester screening. While the cost-effectiveness of such a protocol is disputed, recent studies suggest that it may result in a substantial decrease in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.8,9

Diagnostic tests

The traditional algorithm for the diagnosis of syphilis infection begins with a nontreponemal screening test, such as the RPR or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. If positive, these screening tests are followed by a confirmatory treponemal test, such as the

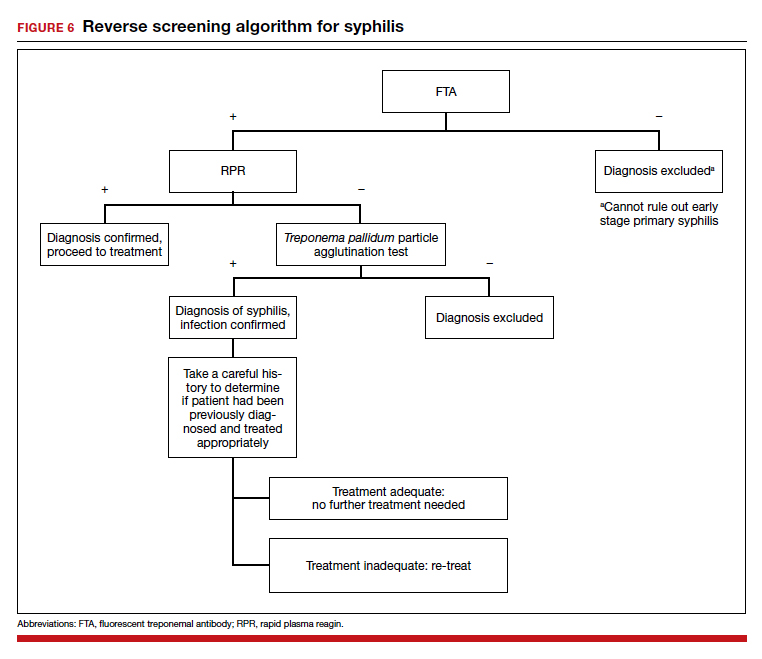

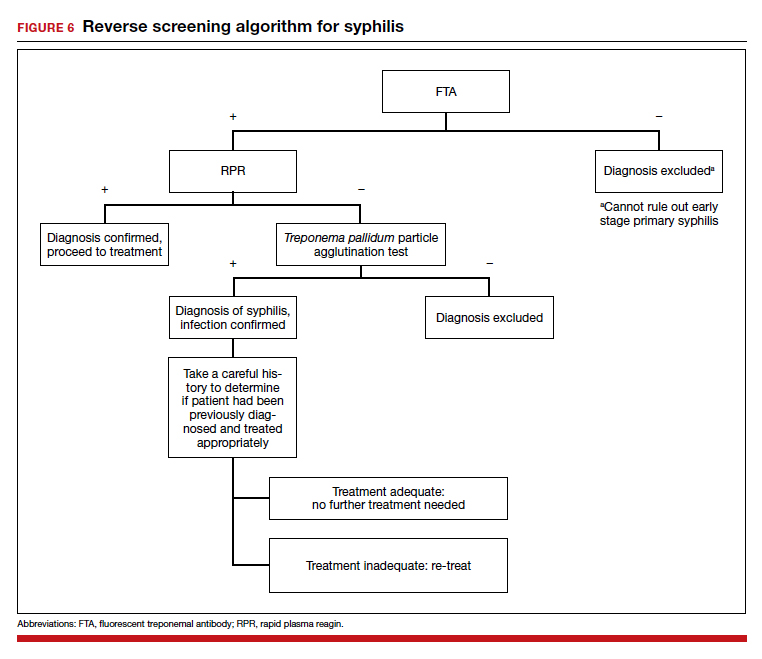

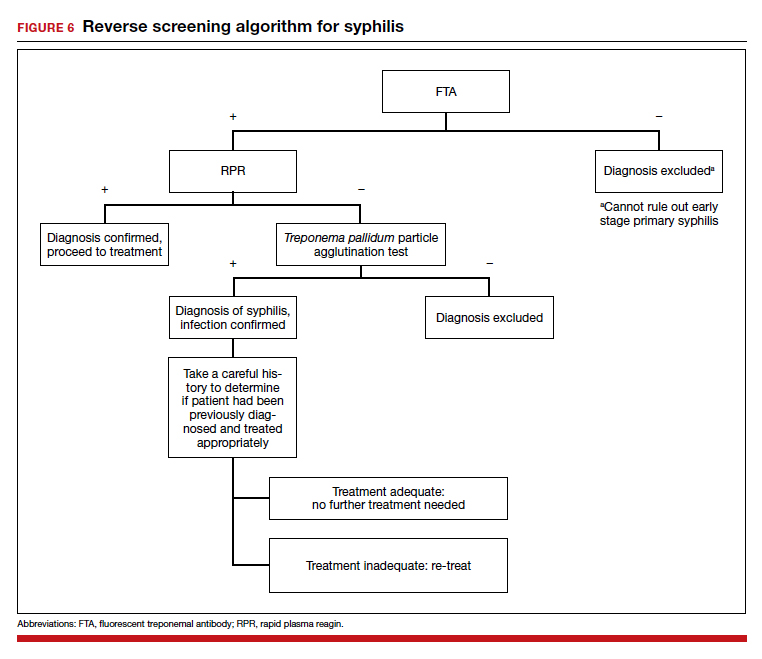

The “reverse” screening algorithm begins with the FTA and, if positive, reflexes to the RPR. A reactive RPR indicates an active infection, and the patient should be treated. A negative RPR should be followed by the TP-PA to rule out a false-positive immunoglobulin G test. If the TP-PA test result is positive, the diagnosis of syphilis is confirmed (FIGURE 6). It is crucial to understand, however, that treponemal antibodies will remain positive for a patient’s lifetime, and someone who may have been treated for syphilis in the past also will screen positive. Once 2 treponemal tests are positive, physicians should take a careful history to assess prior infection risk and treatment status. A negative TP-PA excludes a diagnosis of syphilis.

Advantages of the reverse screening algorithm. Nontreponemal tests are inexpensive and easy to perform, and titers allow for identification of a baseline to evaluate response to treatment.11 However, given the fluctuation of RPR sensitivity (depending on stage of disease and a decreased ability to detect primary and latent stages of syphilis), there has been a resurgence of interest in the reverse algorithm.11 While reverse screening has been found to incur higher costs, and may result in overtreatment and increased stress due to false-positive results,12 there is evidence to suggest that this algorithm is more sensitive for primary and latent infections.8,11,13-15

Given the rise in prevalence of syphilis infections in the United States over the past decade, and therefore a higher pretest probability of syphilis in the population, we favor the reverse screening algorithm in obstetrics, particularly given the risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

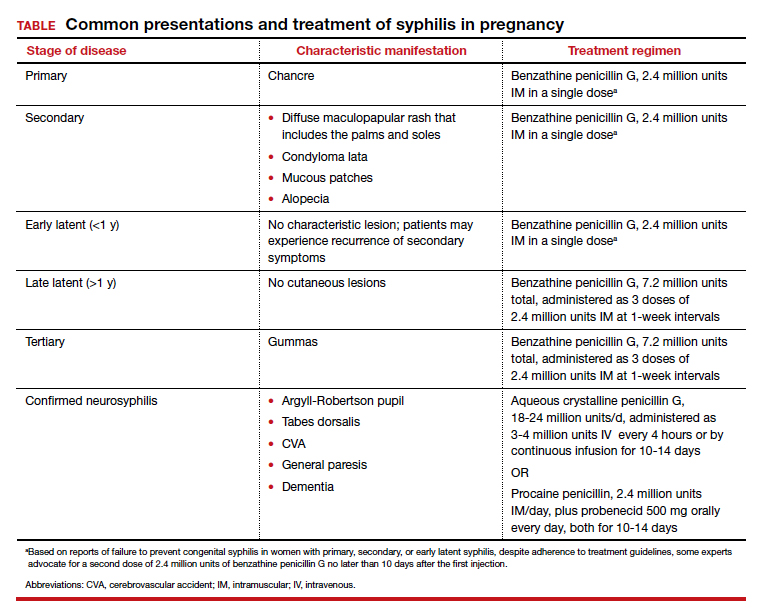

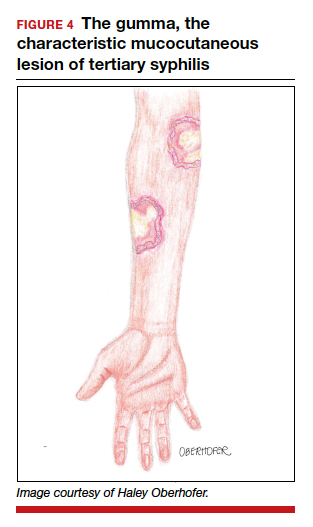

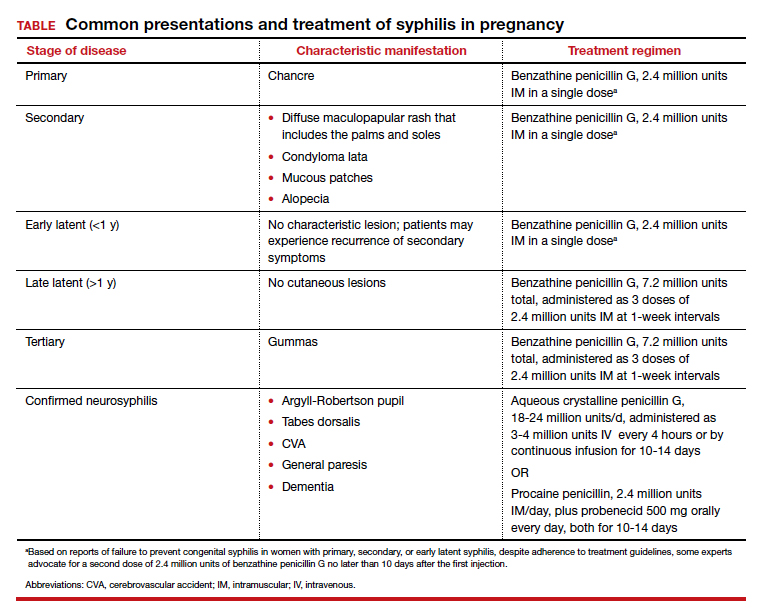

Treating syphilis in pregnancy

Parenteral benzathine penicillin G is the only currently recommended medication for the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy. This drug is effective in treating maternal infection and in preventing fetal infections, as well as in treating established fetal infections.3,5 Regimens differ depending on the stage of syphilis infection (TABLE). Treatment for presumed early syphilis is recommended for women who have had sexual contact with a partner diagnosed with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis within 3 months of their current pregnancy.5 Any patient with diagnosed syphilis who demonstrates clinical signs of neurologic involvement should undergo lumbar puncture to assess for evidence of neurosyphilis.3 CDC guidelines recommend that patients who report an allergy to penicillin undergo desensitization therapy in a controlled setting, as other antibiotics that have been investigated in the treatment of syphilis are either not appropriate due to teratogenicity or due to suboptimal fetal treatment.3,5

Syphilotherapy may lead to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which is an acute systemic reaction to inflammatory cytokines produced in response to lipopolysaccharide released by dying spirochetes.5 This reaction is characterized by fever, chills, myalgia, headache, hypotension, and worsening of cutaneous lesions. Preterm labor and delivery and fetal heart rate tracing abnormalities also have been documented in pregnant women experiencing this reaction, particularly during the second half of pregnancy.16 Prior to the start of treatment, a detailed sonographic assessment should be performed to assess the fetus for signs of early syphilis, including hepatomegaly, elevated peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery (indicative of fetal anemia), polyhydramnios, placentomegaly, or hydrops.5,7

CASE Resolved

The combination of the patient’s test results—positive FTA, negative RPR, and negative TP-PA—suggest a false-positive treponemal assay. This sequence of tests excludes a diagnosis of syphilis; therefore, no treatment is necessary. Depending on the prevalence of syphilis in the patient’s geographic location, as well as her sexual history, rescreening between 28 and 32 weeks may be warranted. ●

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Barnett R. Syphilis. Lancet. 2018;391:1471.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore T, et al. Creasy and Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:862-919.

- Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, et al. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:217-226.

- Adhikari EH. Syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1121-1135.

- Syphilis. CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/syphilis.htm. Published October 1, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Rac MF, Revell PA, Eppes CS. Syphilis during pregnancy: a preventable threat to maternal-fetal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;4:352-363.

- Dunseth CD, Ford BA, Krasowski MD. Traditional versus reverse syphilis algorithms: a comparison at a large academic medical center. Pract Lab Med. 2017;8:52-59.

- Hersh AR, Megli CJ, Caughey AB. Repeat screening for syphilis in the third trimester of pregnancy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:699-706.

- Albright CM, Emerson JB, Werner EF, et al. Third trimester prenatal syphilis screening: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:479-485.

- Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

- Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Peterman TA, Ballard RC. Serologic testing for syphilis in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis of two screening algorithms. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:1-7.

- Huh HJ, Chung JW, Park SY, et al. Comparison of automated treponemal and nontreponemal test algorithms as first-line syphilis screening assays. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36:23-27.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal test for initial screening-four laboratories. New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:872-875.

- Mishra S, Boily MC, Ng V, et al. The laboratory impact of changing syphilis screening from the rapid-plasma reagin to a treponemal enzyme immunoassay: a case-study from the greater Toronto area. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:190-196.

- Klein VR, Cox SM, Mitchell MD, et al. The Jarisch-Herzheimer reaction complicating syphilotherapy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:375-380.

CASE Pregnant woman with positive Treponema pallidum antibody test

A 30-year-old primigravida at 10 weeks and 4 days of gestation by her last menstrual period presents to your office for her initial prenatal visit. She expresses no concerns. You order the standard set of laboratory tests, including a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening panel. Consistent with your institution’s use of the reverse algorithm for syphilis screening, you obtain a Treponema pallidum antibody test, which reflexes to the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Three days later, you receive a notification that this patient’s T pallidum antibody result was positive, followed by negative RPR test results. The follow-up T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test also was negative. Given these findings, you consider:

- What is the correct interpretation of the patient’s sequence of test results?

- Is she infected, and does she require treatment?

Meet our perpetrator

Syphilis has plagued society since the late 15th century, although its causative agent, the spirochete T pallidum, was not recognized until 1905.1,2T pallidum bacteria are transmitted via sexual contact, as well as through vertical transmission during pregnancy or delivery. Infection with syphilis is reported in 50% to 60% of sexual partners after a single exposure to an infected individual with early syphilis, and the mean incubation period is 21 days.3T pallidum can cross the placenta and infect a fetus as early as the sixth week of gestation.3 Congenital syphilis infections occur in the neonates of 50% to 80% of women with untreated primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis infections; maternal syphilis is associated with a 21% increased risk of stillbirth, a 6% increased risk of preterm delivery, and a 9% increased risk of neonatal death.4,5 Additionally, syphilis infection is associated with a high risk of HIV infection, as well as coinfection with other STIs.1

Given the highly infective nature of T pallidum, as well as the severity of the potential consequences of infection for both mothers and babies, primary prevention, education of at-risk populations, and early recognition of clinical features of syphilis infection are of utmost importance in preventing morbidity and mortality. In this article, we review the epidemiology and extensive clinical manifestations of syphilis, as well as current screening recommendations and treatment for pregnant women.

The extent of the problem today

Although US rates of syphilis have ebbed and flowed for the past several decades, the current incidence has grown exponentially in recent years, with the number of cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) increasing by 71% from 2014 to 2018.6 During this time period, reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in women more than doubled (172.7% and 165.4%, respectively) according to CDC data, accompanied by a parallel rise in reported cases of congenital syphilis in both live and stillborn infants.6 In 2018, the CDC reported a national rate of congenital syphilis of 33.1 cases per 100,000 live births, a 39.7% rise compared with data from 2017.6

Those most at risk. Risk factors for syphilis infection include age younger than 30 years, low socioeconomic status, substance abuse, HIV infection, concurrent STIs, and high-risk sexual activity (sex with multiple high-risk partners).3 Additionally, reported rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections, as well as congenital syphilis infections, are more elevated among women who identify as Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Hispanic.6 Congenital infections in the United States are correlated with a lack of prenatal care, which has been similarly linked with racial and socioeconomic disparities, as well as with untreated mental health and substance use disorders and recent immigration to the United States.5,7

Continue to: The many phases of syphilis...

The many phases of syphilis

The characteristic lesion of primary syphilis is a chancre, which is a painless, ulcerative lesion with raised borders and a clean, indurated base appearing at the site of spirochete entry (FIGURE 1). Chancres most commonly appear in the genital area, with the most frequent sites in females being within the vaginal canal or on the cervix. Primary chancres tend to heal spontaneously within 3 to 6 weeks, even without treatment, and frequently are accompanied by painless inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given that the most common chancre sites are not immediately apparent, primary infections in women often go undetected.3 In fact, it is essential for clinicians to recognize that, in our routine practice, most patients with syphilis will not be symptomatic at all, and the diagnosis will only be made by serologic screening.

Following resolution of the primary phase, the patient may enter the secondary stage of T pallidum infection. During this stage, spirochetes may disseminate throughout the bloodstream to infect all major organ systems. The principal manifestations of secondary syphilis include a diffuse maculopapular rash that begins on the trunk and proximal extremities and spreads to include the palms and soles (FIGURE 2); mucosal lesions, such as mucous patches and condyloma lata (FIGURE 3); nonscarring alopecia; periostitis; generalized lymphadenopathy; and, in some cases, hepatitis or nephritis.1,3

Secondary syphilis usually clears within 2 to 6 weeks, with the patient then entering the early latent stage of syphilis. During this period, up to 25% of patients are subject to flares of secondary syphilitic lesions but otherwise are asymptomatic.1,3,4 These recurrences tend to occur within 1 year, hence the distinction between early and late latent stages. Once a year has passed, patients are not contagious by sexual transmission and are unlikely to suffer a relapse of secondary symptoms.1,3 However, late latent syphilis is characterized by periods of intermittent bacteremia that allow for seeding of the placenta and infection in about 10% of fetuses.5

Untreated, about 40% of patients will progress to the tertiary stage of syphilis, which is characterized by gummas affecting the skin and mucous membranes (FIGURE 4) and cardiovascular manifestations including arterial aneurysms and aortic insufficiency.3

Neurologic manifestations of syphilis may arise during any of the above stages, though the most characteristic manifestations tend to appear decades after the primary infection. Early neurosyphilis may present as meningitis, with or without concomitant ocular syphilis (uveitis, retinitis) and/or as otic syphilis (hearing loss, persistent tinnitus).1,5 Patients with late (tertiary) neurosyphilis tend to exhibit meningovascular symptoms similar to stroke (aphasia, hemiplegia, seizures) and/or parenchymal effects such as general paresis. Tabes dorsalis (manifestations of which include urinary and rectal incontinence, lightning pains, and ataxia) is a late-onset manifestation.1,3

Congenital syphilis can be subdivided into an early and late stage. The first stage, in which clinical findings occur within the first 2 years of life, commonly features a desquamating rash, hepatomegaly, and rhinitis. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, periostitis, and osteomyelitis also have been documented.5 Of note, two-thirds of infants are asymptomatic at birth and may not develop such clinical manifestations for 3 to 8 weeks.3 If untreated, early congenital infection may progress to late manifestations, such as Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, interstitial keratitis, deafness, saddle nose, saber shins, and such neurologic abnormalities as developmental delay and general paresis.3

Continue to: Prenatal screening and diagnosis...

Prenatal screening and diagnosis

Current recommendations issued by the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists state that all pregnant women should be screened for syphilis infection at their first presentation to care, with repeat screening between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation and at birth, for women living in areas with a high prevalence of syphilis and/or with any of the aforementioned risk factors.3,5 Given that providers may be unfamiliar with the prevalence of syphilis in their area, and that patients may acquire or develop an infection later on in their pregnancy, researchers have begun to investigate the feasibility of universal third-trimester screening. While the cost-effectiveness of such a protocol is disputed, recent studies suggest that it may result in a substantial decrease in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.8,9

Diagnostic tests

The traditional algorithm for the diagnosis of syphilis infection begins with a nontreponemal screening test, such as the RPR or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. If positive, these screening tests are followed by a confirmatory treponemal test, such as the

The “reverse” screening algorithm begins with the FTA and, if positive, reflexes to the RPR. A reactive RPR indicates an active infection, and the patient should be treated. A negative RPR should be followed by the TP-PA to rule out a false-positive immunoglobulin G test. If the TP-PA test result is positive, the diagnosis of syphilis is confirmed (FIGURE 6). It is crucial to understand, however, that treponemal antibodies will remain positive for a patient’s lifetime, and someone who may have been treated for syphilis in the past also will screen positive. Once 2 treponemal tests are positive, physicians should take a careful history to assess prior infection risk and treatment status. A negative TP-PA excludes a diagnosis of syphilis.

Advantages of the reverse screening algorithm. Nontreponemal tests are inexpensive and easy to perform, and titers allow for identification of a baseline to evaluate response to treatment.11 However, given the fluctuation of RPR sensitivity (depending on stage of disease and a decreased ability to detect primary and latent stages of syphilis), there has been a resurgence of interest in the reverse algorithm.11 While reverse screening has been found to incur higher costs, and may result in overtreatment and increased stress due to false-positive results,12 there is evidence to suggest that this algorithm is more sensitive for primary and latent infections.8,11,13-15

Given the rise in prevalence of syphilis infections in the United States over the past decade, and therefore a higher pretest probability of syphilis in the population, we favor the reverse screening algorithm in obstetrics, particularly given the risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Treating syphilis in pregnancy

Parenteral benzathine penicillin G is the only currently recommended medication for the treatment of syphilis in pregnancy. This drug is effective in treating maternal infection and in preventing fetal infections, as well as in treating established fetal infections.3,5 Regimens differ depending on the stage of syphilis infection (TABLE). Treatment for presumed early syphilis is recommended for women who have had sexual contact with a partner diagnosed with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis within 3 months of their current pregnancy.5 Any patient with diagnosed syphilis who demonstrates clinical signs of neurologic involvement should undergo lumbar puncture to assess for evidence of neurosyphilis.3 CDC guidelines recommend that patients who report an allergy to penicillin undergo desensitization therapy in a controlled setting, as other antibiotics that have been investigated in the treatment of syphilis are either not appropriate due to teratogenicity or due to suboptimal fetal treatment.3,5

Syphilotherapy may lead to the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which is an acute systemic reaction to inflammatory cytokines produced in response to lipopolysaccharide released by dying spirochetes.5 This reaction is characterized by fever, chills, myalgia, headache, hypotension, and worsening of cutaneous lesions. Preterm labor and delivery and fetal heart rate tracing abnormalities also have been documented in pregnant women experiencing this reaction, particularly during the second half of pregnancy.16 Prior to the start of treatment, a detailed sonographic assessment should be performed to assess the fetus for signs of early syphilis, including hepatomegaly, elevated peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery (indicative of fetal anemia), polyhydramnios, placentomegaly, or hydrops.5,7

CASE Resolved

The combination of the patient’s test results—positive FTA, negative RPR, and negative TP-PA—suggest a false-positive treponemal assay. This sequence of tests excludes a diagnosis of syphilis; therefore, no treatment is necessary. Depending on the prevalence of syphilis in the patient’s geographic location, as well as her sexual history, rescreening between 28 and 32 weeks may be warranted. ●

CASE Pregnant woman with positive Treponema pallidum antibody test

A 30-year-old primigravida at 10 weeks and 4 days of gestation by her last menstrual period presents to your office for her initial prenatal visit. She expresses no concerns. You order the standard set of laboratory tests, including a sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening panel. Consistent with your institution’s use of the reverse algorithm for syphilis screening, you obtain a Treponema pallidum antibody test, which reflexes to the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Three days later, you receive a notification that this patient’s T pallidum antibody result was positive, followed by negative RPR test results. The follow-up T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test also was negative. Given these findings, you consider:

- What is the correct interpretation of the patient’s sequence of test results?

- Is she infected, and does she require treatment?

Meet our perpetrator

Syphilis has plagued society since the late 15th century, although its causative agent, the spirochete T pallidum, was not recognized until 1905.1,2T pallidum bacteria are transmitted via sexual contact, as well as through vertical transmission during pregnancy or delivery. Infection with syphilis is reported in 50% to 60% of sexual partners after a single exposure to an infected individual with early syphilis, and the mean incubation period is 21 days.3T pallidum can cross the placenta and infect a fetus as early as the sixth week of gestation.3 Congenital syphilis infections occur in the neonates of 50% to 80% of women with untreated primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis infections; maternal syphilis is associated with a 21% increased risk of stillbirth, a 6% increased risk of preterm delivery, and a 9% increased risk of neonatal death.4,5 Additionally, syphilis infection is associated with a high risk of HIV infection, as well as coinfection with other STIs.1