User login

Immune checkpoint inhibitors don’t increase COVID-19 incidence or mortality, studies suggest

Cytokine storm plays a major role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. This has generated concern about using ICIs during the pandemic, given their immunostimulatory activity and the risk of immune-related adverse effects.

However, two retrospective studies suggest ICIs do not increase the risk of developing COVID-19 or dying from the disease.

In a study of 1,545 cancer patients prescribed ICIs and 20,418 matched controls, the incidence of COVID-19 was 1.4% with ICI therapy and 1.0% without it (odds ratio, 1.38; P = .15).

In a case-control study of 50 patients with cancer and COVID-19, 28% of patients who had received ICIs died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of patients who had not received ICIs (OR, 0.36; P = .23).

Vartan Pahalyants and Kevin Tyan, both students in Harvard University’s joint MD/MBA program in Boston, presented these studies at the meeting.

COVID-19 incidence with ICIs

Mr. Pahalyants and colleagues analyzed data from cancer patients treated in the Mass General Brigham health care system. The researchers compared 1,545 patients with at least one ICI prescription between July 1, 2019, and Feb. 29, 2020, with 20,418 matched cancer patients not prescribed ICIs. The team assessed COVID-19 incidence based on positive test results through June 19, 2020, from public health data.

The incidence of COVID-19 was low in both groups – 1.4% in the ICI group and 1.0% in the matched control group (P = .16). Among COVID-19–positive patients, the all-cause death rate was 40.9% in the ICI group and 28.6% in the control group (P = .23).

In multivariate analysis, patients prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for COVID-19 relative to peers not prescribed ICIs (OR, 1.38; P = .15). However, risk was significantly increased for female patients (OR, 1.74; P < .001), those living in a town or county with higher COVID-19 positivity rate (OR, 1.59; P < .001), and those with severe comorbidity (vs. mild or moderate; OR, 9.77; P = .02).

Among COVID-19–positive patients, those prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for all-cause mortality (OR, 1.60; P = .71), but male sex and lower income were associated with an increased risk of death.

“We did not identify an increased risk of [COVID-19] diagnosis among patients prescribed ICIs compared to the controls,” Mr. Pahalyants said. “This information may assist patients and their providers in decision-making around continuation of therapy during this protracted pandemic. However, more research needs to be conducted to determine potential behavioral and testing factors that may have affected COVID-19 diagnosis susceptibility among patients included in the study.”

COVID-19 mortality with ICIs

For their study, Mr. Tyan and colleagues identified 25 cancer patients who had received ICIs in the year before a COVID-19 diagnosis between March 20, 2020, and June 3, 2020, at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mass General Brigham network. The researchers then matched each patient with a cancer patient having a COVID-19 diagnosis who had not received ICIs during the preceding year.

Overall, 28% of patients who had received ICIs before their COVID-19 diagnosis died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of those who had not received ICIs.

In multivariate analysis, ICI therapy did not predict COVID-19 mortality (OR, 0.36; P = .23). However, the risk of death from COVID-19 increased with age (OR, 1.14; P = .01) and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 12.26; P = .01), and risk was lower for statin users (OR, 0.08; P = .02). Findings were similar in an analysis restricted to hospitalized patients in the ICI group and their matched controls.

Two ICI-treated patients with COVID-19 had persistent immune-related adverse events (hypophysitis in both cases), and one ICI-treated patient developed a new immune-related adverse event (hypothyroidism).

At COVID-19 presentation, relative to counterparts who had not received ICIs, patients who had received ICIs had higher platelet counts (P = .017) and higher D-dimer levels (P = .037). In the context of similar levels of other biomarkers, this finding is “of unclear significance, as all deaths in the cohort were due to respiratory failure as opposed to hypercoagulability,” Mr. Tyan said.

The patients treated with ICIs were more likely to die from COVID-19 if they had elevated troponin levels (P = .01), whereas no such association was seen for those not treated with ICIs.

“We found that ICI therapy is not associated with greater risk for COVID-19 mortality. Our period of follow-up was relatively short, but we did not observe a high incidence of new or persistent immune-related adverse events among our patients taking ICIs,” Mr. Tyan said.

“While larger prospective trials are needed to evaluate long-term safety in the context of COVID-19 infection, our findings support the continuation of ICI therapy during the pandemic as it does not appear to worsen outcomes for cancer patients,” he concluded.

ICI therapy can continue, with precautions

“The question of susceptibility to COVID-19 has been unclear as ICIs do not necessarily cause immunosuppression but certainly result in modulation of a patient’s immune system,” said Deborah Doroshow, MD, PhD, assistant professor at the Tisch Cancer Institute Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She was not involved in these studies.

“The findings of the study by Pahalyants and colleagues, which used a very large sample size, appear to convincingly demonstrate that ICI receipt is not associated with an increased susceptibility to COVID-19,” Dr. Doroshow said in an interview.

However, the findings of the study by Tyan and colleagues are more “thought-provoking,” Dr. Doroshow said. She noted that a large study published in Nature Medicine showed previous ICI therapy in cancer patients with COVID-19 increased the risk for hospitalization or severe COVID-19 requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation. The new study was much smaller and did not perform statistical comparisons for outcomes such as oxygen requirements.

“I would feel comfortable telling patients that the data suggests that ICI treatment does not increase their risk of COVID-19. However, if they were to be diagnosed with COVID-19, it is unclear whether their previous ICI treatment increases their risk for poor outcomes,” Dr. Doroshow said.

“I would feel comfortable continuing to treat patients with ICIs at this time, but because we know that patients with cancer are generally more likely to develop COVID-19 and have poor outcomes, it is critical that our patients be educated about social distancing and mask wearing to the extent that their living and working situations permit,” she added.

Mr. Pahalyants disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Mr. Tyan disclosed that he is cofounder and chief science officer of Kinnos, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Doroshow disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pahalyants V et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 826. Tyan K et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 481.

Cytokine storm plays a major role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. This has generated concern about using ICIs during the pandemic, given their immunostimulatory activity and the risk of immune-related adverse effects.

However, two retrospective studies suggest ICIs do not increase the risk of developing COVID-19 or dying from the disease.

In a study of 1,545 cancer patients prescribed ICIs and 20,418 matched controls, the incidence of COVID-19 was 1.4% with ICI therapy and 1.0% without it (odds ratio, 1.38; P = .15).

In a case-control study of 50 patients with cancer and COVID-19, 28% of patients who had received ICIs died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of patients who had not received ICIs (OR, 0.36; P = .23).

Vartan Pahalyants and Kevin Tyan, both students in Harvard University’s joint MD/MBA program in Boston, presented these studies at the meeting.

COVID-19 incidence with ICIs

Mr. Pahalyants and colleagues analyzed data from cancer patients treated in the Mass General Brigham health care system. The researchers compared 1,545 patients with at least one ICI prescription between July 1, 2019, and Feb. 29, 2020, with 20,418 matched cancer patients not prescribed ICIs. The team assessed COVID-19 incidence based on positive test results through June 19, 2020, from public health data.

The incidence of COVID-19 was low in both groups – 1.4% in the ICI group and 1.0% in the matched control group (P = .16). Among COVID-19–positive patients, the all-cause death rate was 40.9% in the ICI group and 28.6% in the control group (P = .23).

In multivariate analysis, patients prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for COVID-19 relative to peers not prescribed ICIs (OR, 1.38; P = .15). However, risk was significantly increased for female patients (OR, 1.74; P < .001), those living in a town or county with higher COVID-19 positivity rate (OR, 1.59; P < .001), and those with severe comorbidity (vs. mild or moderate; OR, 9.77; P = .02).

Among COVID-19–positive patients, those prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for all-cause mortality (OR, 1.60; P = .71), but male sex and lower income were associated with an increased risk of death.

“We did not identify an increased risk of [COVID-19] diagnosis among patients prescribed ICIs compared to the controls,” Mr. Pahalyants said. “This information may assist patients and their providers in decision-making around continuation of therapy during this protracted pandemic. However, more research needs to be conducted to determine potential behavioral and testing factors that may have affected COVID-19 diagnosis susceptibility among patients included in the study.”

COVID-19 mortality with ICIs

For their study, Mr. Tyan and colleagues identified 25 cancer patients who had received ICIs in the year before a COVID-19 diagnosis between March 20, 2020, and June 3, 2020, at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mass General Brigham network. The researchers then matched each patient with a cancer patient having a COVID-19 diagnosis who had not received ICIs during the preceding year.

Overall, 28% of patients who had received ICIs before their COVID-19 diagnosis died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of those who had not received ICIs.

In multivariate analysis, ICI therapy did not predict COVID-19 mortality (OR, 0.36; P = .23). However, the risk of death from COVID-19 increased with age (OR, 1.14; P = .01) and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 12.26; P = .01), and risk was lower for statin users (OR, 0.08; P = .02). Findings were similar in an analysis restricted to hospitalized patients in the ICI group and their matched controls.

Two ICI-treated patients with COVID-19 had persistent immune-related adverse events (hypophysitis in both cases), and one ICI-treated patient developed a new immune-related adverse event (hypothyroidism).

At COVID-19 presentation, relative to counterparts who had not received ICIs, patients who had received ICIs had higher platelet counts (P = .017) and higher D-dimer levels (P = .037). In the context of similar levels of other biomarkers, this finding is “of unclear significance, as all deaths in the cohort were due to respiratory failure as opposed to hypercoagulability,” Mr. Tyan said.

The patients treated with ICIs were more likely to die from COVID-19 if they had elevated troponin levels (P = .01), whereas no such association was seen for those not treated with ICIs.

“We found that ICI therapy is not associated with greater risk for COVID-19 mortality. Our period of follow-up was relatively short, but we did not observe a high incidence of new or persistent immune-related adverse events among our patients taking ICIs,” Mr. Tyan said.

“While larger prospective trials are needed to evaluate long-term safety in the context of COVID-19 infection, our findings support the continuation of ICI therapy during the pandemic as it does not appear to worsen outcomes for cancer patients,” he concluded.

ICI therapy can continue, with precautions

“The question of susceptibility to COVID-19 has been unclear as ICIs do not necessarily cause immunosuppression but certainly result in modulation of a patient’s immune system,” said Deborah Doroshow, MD, PhD, assistant professor at the Tisch Cancer Institute Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She was not involved in these studies.

“The findings of the study by Pahalyants and colleagues, which used a very large sample size, appear to convincingly demonstrate that ICI receipt is not associated with an increased susceptibility to COVID-19,” Dr. Doroshow said in an interview.

However, the findings of the study by Tyan and colleagues are more “thought-provoking,” Dr. Doroshow said. She noted that a large study published in Nature Medicine showed previous ICI therapy in cancer patients with COVID-19 increased the risk for hospitalization or severe COVID-19 requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation. The new study was much smaller and did not perform statistical comparisons for outcomes such as oxygen requirements.

“I would feel comfortable telling patients that the data suggests that ICI treatment does not increase their risk of COVID-19. However, if they were to be diagnosed with COVID-19, it is unclear whether their previous ICI treatment increases their risk for poor outcomes,” Dr. Doroshow said.

“I would feel comfortable continuing to treat patients with ICIs at this time, but because we know that patients with cancer are generally more likely to develop COVID-19 and have poor outcomes, it is critical that our patients be educated about social distancing and mask wearing to the extent that their living and working situations permit,” she added.

Mr. Pahalyants disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Mr. Tyan disclosed that he is cofounder and chief science officer of Kinnos, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Doroshow disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pahalyants V et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 826. Tyan K et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 481.

Cytokine storm plays a major role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, according to research published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. This has generated concern about using ICIs during the pandemic, given their immunostimulatory activity and the risk of immune-related adverse effects.

However, two retrospective studies suggest ICIs do not increase the risk of developing COVID-19 or dying from the disease.

In a study of 1,545 cancer patients prescribed ICIs and 20,418 matched controls, the incidence of COVID-19 was 1.4% with ICI therapy and 1.0% without it (odds ratio, 1.38; P = .15).

In a case-control study of 50 patients with cancer and COVID-19, 28% of patients who had received ICIs died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of patients who had not received ICIs (OR, 0.36; P = .23).

Vartan Pahalyants and Kevin Tyan, both students in Harvard University’s joint MD/MBA program in Boston, presented these studies at the meeting.

COVID-19 incidence with ICIs

Mr. Pahalyants and colleagues analyzed data from cancer patients treated in the Mass General Brigham health care system. The researchers compared 1,545 patients with at least one ICI prescription between July 1, 2019, and Feb. 29, 2020, with 20,418 matched cancer patients not prescribed ICIs. The team assessed COVID-19 incidence based on positive test results through June 19, 2020, from public health data.

The incidence of COVID-19 was low in both groups – 1.4% in the ICI group and 1.0% in the matched control group (P = .16). Among COVID-19–positive patients, the all-cause death rate was 40.9% in the ICI group and 28.6% in the control group (P = .23).

In multivariate analysis, patients prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for COVID-19 relative to peers not prescribed ICIs (OR, 1.38; P = .15). However, risk was significantly increased for female patients (OR, 1.74; P < .001), those living in a town or county with higher COVID-19 positivity rate (OR, 1.59; P < .001), and those with severe comorbidity (vs. mild or moderate; OR, 9.77; P = .02).

Among COVID-19–positive patients, those prescribed ICIs did not have a significantly elevated risk for all-cause mortality (OR, 1.60; P = .71), but male sex and lower income were associated with an increased risk of death.

“We did not identify an increased risk of [COVID-19] diagnosis among patients prescribed ICIs compared to the controls,” Mr. Pahalyants said. “This information may assist patients and their providers in decision-making around continuation of therapy during this protracted pandemic. However, more research needs to be conducted to determine potential behavioral and testing factors that may have affected COVID-19 diagnosis susceptibility among patients included in the study.”

COVID-19 mortality with ICIs

For their study, Mr. Tyan and colleagues identified 25 cancer patients who had received ICIs in the year before a COVID-19 diagnosis between March 20, 2020, and June 3, 2020, at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Mass General Brigham network. The researchers then matched each patient with a cancer patient having a COVID-19 diagnosis who had not received ICIs during the preceding year.

Overall, 28% of patients who had received ICIs before their COVID-19 diagnosis died from COVID-19, compared with 36% of those who had not received ICIs.

In multivariate analysis, ICI therapy did not predict COVID-19 mortality (OR, 0.36; P = .23). However, the risk of death from COVID-19 increased with age (OR, 1.14; P = .01) and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 12.26; P = .01), and risk was lower for statin users (OR, 0.08; P = .02). Findings were similar in an analysis restricted to hospitalized patients in the ICI group and their matched controls.

Two ICI-treated patients with COVID-19 had persistent immune-related adverse events (hypophysitis in both cases), and one ICI-treated patient developed a new immune-related adverse event (hypothyroidism).

At COVID-19 presentation, relative to counterparts who had not received ICIs, patients who had received ICIs had higher platelet counts (P = .017) and higher D-dimer levels (P = .037). In the context of similar levels of other biomarkers, this finding is “of unclear significance, as all deaths in the cohort were due to respiratory failure as opposed to hypercoagulability,” Mr. Tyan said.

The patients treated with ICIs were more likely to die from COVID-19 if they had elevated troponin levels (P = .01), whereas no such association was seen for those not treated with ICIs.

“We found that ICI therapy is not associated with greater risk for COVID-19 mortality. Our period of follow-up was relatively short, but we did not observe a high incidence of new or persistent immune-related adverse events among our patients taking ICIs,” Mr. Tyan said.

“While larger prospective trials are needed to evaluate long-term safety in the context of COVID-19 infection, our findings support the continuation of ICI therapy during the pandemic as it does not appear to worsen outcomes for cancer patients,” he concluded.

ICI therapy can continue, with precautions

“The question of susceptibility to COVID-19 has been unclear as ICIs do not necessarily cause immunosuppression but certainly result in modulation of a patient’s immune system,” said Deborah Doroshow, MD, PhD, assistant professor at the Tisch Cancer Institute Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. She was not involved in these studies.

“The findings of the study by Pahalyants and colleagues, which used a very large sample size, appear to convincingly demonstrate that ICI receipt is not associated with an increased susceptibility to COVID-19,” Dr. Doroshow said in an interview.

However, the findings of the study by Tyan and colleagues are more “thought-provoking,” Dr. Doroshow said. She noted that a large study published in Nature Medicine showed previous ICI therapy in cancer patients with COVID-19 increased the risk for hospitalization or severe COVID-19 requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation. The new study was much smaller and did not perform statistical comparisons for outcomes such as oxygen requirements.

“I would feel comfortable telling patients that the data suggests that ICI treatment does not increase their risk of COVID-19. However, if they were to be diagnosed with COVID-19, it is unclear whether their previous ICI treatment increases their risk for poor outcomes,” Dr. Doroshow said.

“I would feel comfortable continuing to treat patients with ICIs at this time, but because we know that patients with cancer are generally more likely to develop COVID-19 and have poor outcomes, it is critical that our patients be educated about social distancing and mask wearing to the extent that their living and working situations permit,” she added.

Mr. Pahalyants disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Mr. Tyan disclosed that he is cofounder and chief science officer of Kinnos, and his study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Doroshow disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pahalyants V et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 826. Tyan K et al. SITC 2020, Abstract 481.

FROM SITC 2020

Rapid relief of opioid-induced constipation with MNTX

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

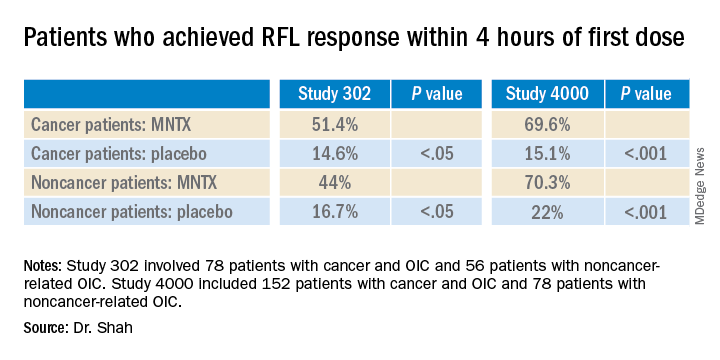

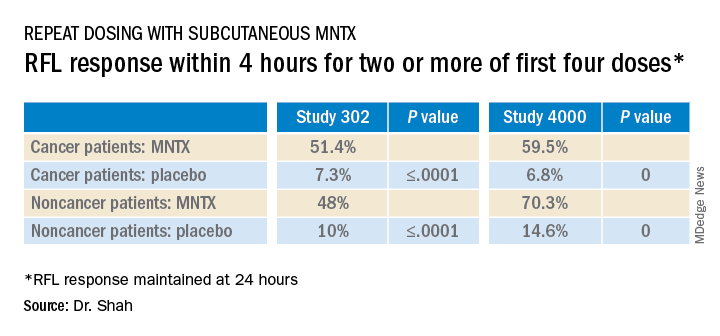

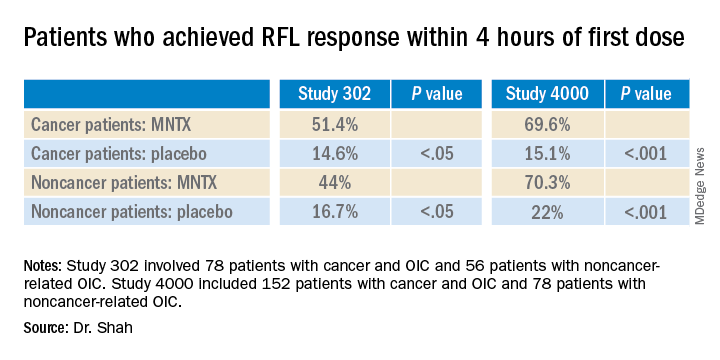

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

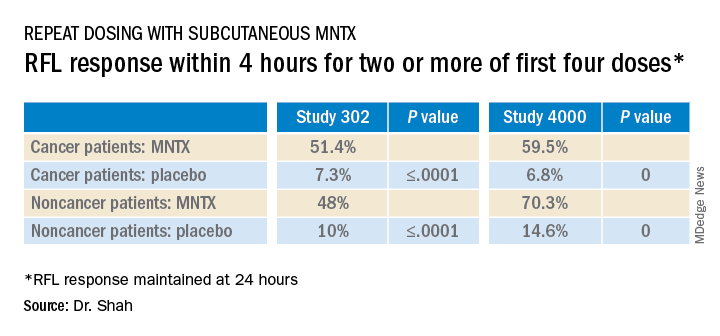

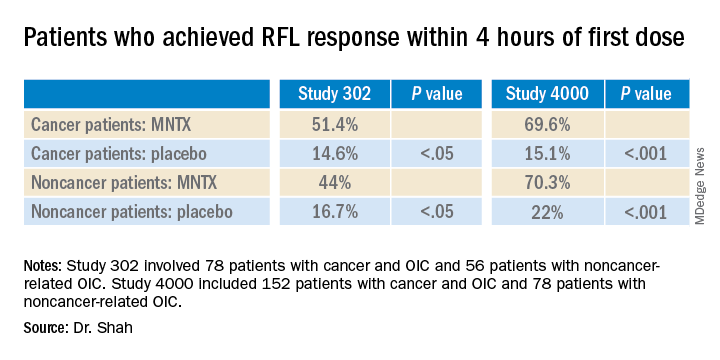

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subcutaneously administered methylnaltrexone (MNTX) (Relistor), a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, relieves opioid-induced constipation (OID) in both chronic, noncancer-related illness and cancer-related illness, a new analysis concludes.

“While these are two very different patient groups, the ability to have something to treat OIC in noncancer patients who stay on opioids for whatever reason helps, because [otherwise] these patients are not doing well,” said lead author Eric Shah, MD, motility director for the Dartmouth program at Dartmouth Hitchcock Health, Lebanon, N.H.

Importantly, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as MNTX do not affect overall pain control to any significant extent, which is “reassuring,” he said in an interview.

These drugs decrease the constipating effects of opioids without reversing CNS-mediated opioid effects, he explained.

“Methylnaltrexone has already been approved for the treatment of OIC in adults with chronic noncancer pain as well as for OIC in adults with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, which is often the case in patients with cancer-related pain,” he noted.

Dr. Shah discussed the new analysis during PAINWeek 2020, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 19th Annual Pain Medicine Meeting.

The analysis was based on a review of data collected in two previously reported randomized, placebo-controlled studies (study 302 and 4000), which were used to gain approval.

The new analysis shows that “the drug works up front, and the effect is able to be maintained. I think the studies are clinically relevant in that patients are able to have a bowel movement quickly after you give them an injectable formulation when they are vomiting or otherwise can’t tolerate a pill and they are feeling miserable,” Dr. Shah commented. Many patients with OIC are constipated for reasons other than from opioid use. They often have other side effects from opioids, including bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

“When patients go to the emergency room, it’s not just that they are not able to have a bowel movement; they are often also vomiting, so it’s important to have agents that can be given in a manner that avoids the need for oral medication,” Dr. Shah said. MNTX is the only peripherally acting opioid antagonist available in a subcutaneous formulation.

Moreover, if patients are able to control these symptoms at home with an injectable formulation, they may not need to go to the ED for treatment of their gastrointestinal distress, he added.

Viable product

In a comment, Darren Brenner, MD, associate professor of medicine and surgery, Northwestern University, Chicago, who has worked with this subcutaneous formulation, said it is “definitely a viable product.

“The data presented here were in patients with advanced illness receiving palliative care when other laxatives have failed, and the difference and the potential benefit for MNTX is that it is the only peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist that is approved for advanced cancer,” he added. The other products that are currently approved, naloxegol (Movantik) and naldemedine (Symproic), are both indicated for chronic, noncancer pain.

The other potential benefit of subcutaneous MNTX is that it can work very rapidly for the patients who respond to it. “One of the things investigators did not mention in these two trials but which has been shown in previous studies is that almost half of patients who respond to this drug respond within the first 30 minutes of receiving the injection,” Dr. Brenner said in an interview.

This can be very beneficial in an emergency setting, because it may avoid having patients admitted to hospital. They can be discharged and sent home with enough drug to use on demand, Dr. Brenner suggested.

New analysis of data from studies 302 and 4000

Both studies were carried out in adults with advanced illness and OIC whose conditions were refractory to laxative use. Both of the studies were placebo controlled.

Study 302 involved 78 patients with cancer and 56 patients with noncancer-related OIC. MNTX was given at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg subcutaneously every other day for 2 weeks.

Study 4000 included 152 patients with cancer and OIC and 78 patients with noncancer-related OIC. In this study, the dose of MNTX was based on body weight. Seven or fewer doses of either 8 mg or 12 mg were given subcutaneously for 2 weeks.

The main endpoints of both studies was the proportion of patients who achieved a rescue-free laxation (RFL) response within 4 hours after the first dose and the proportion of patients with an RFL response within 4 hours for two or more of the first four doses within 24 hours.

Dr. Shah explained that RFL is a meaningful clinical endpoint. Patients could achieve a bowel movement with the two prespecified time endpoints in both studies.

Not all patients were hospitalized for OIC, Dr. Shah noted. Entry criteria were strict and included having fewer than three bowel movements during the previous week and no clinically significant laxation (defecation) within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of study drug.

“In both studies, a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with MNTX versus placebo achieved an RFL within 4 hours after the first dose among both cancer and noncancer patients,” the investigators reported.

Results were relatively comparable between cancer and noncancer patients who were treated for OIC in study 4000, the investigators noted.

Both studies were sponsored by Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shah has received travel fees from Salix Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Brenner has served as a consultant for Salix Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and Purdue Pharma. AstraZeneca developed naloxegol.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reduced cancer mortality with Medicaid expansion

Researchers reviewed data on 523,802 patients in the National Cancer Database who were diagnosed with cancer from 2012 through 2015. Slightly more than half of patients (55.2%) lived in Medicaid expansion states.

After expansion, mortality significantly decreased in expansion states (hazard ratio, 0.98; P = .008) but not in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.01; P = .43). The difference was significant in a difference-in-difference analysis (HR, 1.03; P = .01).

Across 69,000 patients with newly diagnosed cancer in Medicaid expansion states, the 2% decrease in the hazard of death would translate to 1,384 lives saved annually.

The benefit was primarily observed in patients with nonmetastatic cancer. For patients with stage I-III cancer, the risk of death was increased in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P < .001) and unchanged in expansion states (HR, 0.99; P = .64). Mortality significantly improved in expansion states vs. nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P = .003).

For patients with stage IV cancer, both expansion and nonexpansion states had improvements in mortality, but the differences were not significant.

“Earlier stage at diagnosis appears to explain the mortality improvement,” wrote study author Miranda Lam, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

Clinical benefits, ‘no economic downside’

Under the Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, states have the option of expanding Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level. As of March 2020, 36 states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid, with more than 20 million residents obtaining coverage.

Previous studies have associated Medicaid expansion with fewer patients being uninsured, increased cancer screening, and earlier stage of diagnosis, as well as reduced racial disparities in access to high-volume hospitals for cancer surgery and increased rates of cancer surgery among low-income patients.

“This study adds to an increasingly large body of research finding that Medicaid expansion has improved our ability to fight cancer,” said Coleman Drake, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in this study.

“Obtaining health insurance through Medicaid allows patients to receive recommended preventive cancer screenings, which explains the increase in early-stage diagnosis rates. Detecting cancer early is critical for successful cancer treatment,” Dr. Drake noted.

“It is hard to overstate the positive effects of Medicaid expansion on health outcomes. At the same time, concerns that Medicaid expansion would be costly to state governments’ budgets have not been realized. In short, Medicaid expansion yields many benefits and has no economic downside for state policymakers. Clinical and economic evidence make an overwhelming case for states to expand Medicaid,” Dr. Drake said.

Significant difference for lung cancer

Most patients in this study were women (73.6%), and the patients’ mean age was 54.8 years (range, 40-64 years). Patients had newly diagnosed breast cancer (52.2%), colorectal cancer (21.3%), and lung cancer (26.5%).

The benefits of Medicaid expansion persisted after adjustment for education, income, insurance, and race.

The lower mortality in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states was similar across all three cancer types. However, in stratified analyses, the difference was significant only for lung cancer (P = .03).

“Lung cancer has a higher mortality rate than breast and colorectal cancer, and with longer follow-up, it is possible that the lower mortality rates seen for breast and colorectal cancer may also become significant,” the authors wrote.

This research was funded by Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Drake had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lam MB et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2024366.

Researchers reviewed data on 523,802 patients in the National Cancer Database who were diagnosed with cancer from 2012 through 2015. Slightly more than half of patients (55.2%) lived in Medicaid expansion states.

After expansion, mortality significantly decreased in expansion states (hazard ratio, 0.98; P = .008) but not in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.01; P = .43). The difference was significant in a difference-in-difference analysis (HR, 1.03; P = .01).

Across 69,000 patients with newly diagnosed cancer in Medicaid expansion states, the 2% decrease in the hazard of death would translate to 1,384 lives saved annually.

The benefit was primarily observed in patients with nonmetastatic cancer. For patients with stage I-III cancer, the risk of death was increased in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P < .001) and unchanged in expansion states (HR, 0.99; P = .64). Mortality significantly improved in expansion states vs. nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P = .003).

For patients with stage IV cancer, both expansion and nonexpansion states had improvements in mortality, but the differences were not significant.

“Earlier stage at diagnosis appears to explain the mortality improvement,” wrote study author Miranda Lam, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

Clinical benefits, ‘no economic downside’

Under the Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, states have the option of expanding Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level. As of March 2020, 36 states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid, with more than 20 million residents obtaining coverage.

Previous studies have associated Medicaid expansion with fewer patients being uninsured, increased cancer screening, and earlier stage of diagnosis, as well as reduced racial disparities in access to high-volume hospitals for cancer surgery and increased rates of cancer surgery among low-income patients.

“This study adds to an increasingly large body of research finding that Medicaid expansion has improved our ability to fight cancer,” said Coleman Drake, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in this study.

“Obtaining health insurance through Medicaid allows patients to receive recommended preventive cancer screenings, which explains the increase in early-stage diagnosis rates. Detecting cancer early is critical for successful cancer treatment,” Dr. Drake noted.

“It is hard to overstate the positive effects of Medicaid expansion on health outcomes. At the same time, concerns that Medicaid expansion would be costly to state governments’ budgets have not been realized. In short, Medicaid expansion yields many benefits and has no economic downside for state policymakers. Clinical and economic evidence make an overwhelming case for states to expand Medicaid,” Dr. Drake said.

Significant difference for lung cancer

Most patients in this study were women (73.6%), and the patients’ mean age was 54.8 years (range, 40-64 years). Patients had newly diagnosed breast cancer (52.2%), colorectal cancer (21.3%), and lung cancer (26.5%).

The benefits of Medicaid expansion persisted after adjustment for education, income, insurance, and race.

The lower mortality in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states was similar across all three cancer types. However, in stratified analyses, the difference was significant only for lung cancer (P = .03).

“Lung cancer has a higher mortality rate than breast and colorectal cancer, and with longer follow-up, it is possible that the lower mortality rates seen for breast and colorectal cancer may also become significant,” the authors wrote.

This research was funded by Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Drake had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lam MB et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2024366.

Researchers reviewed data on 523,802 patients in the National Cancer Database who were diagnosed with cancer from 2012 through 2015. Slightly more than half of patients (55.2%) lived in Medicaid expansion states.

After expansion, mortality significantly decreased in expansion states (hazard ratio, 0.98; P = .008) but not in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.01; P = .43). The difference was significant in a difference-in-difference analysis (HR, 1.03; P = .01).

Across 69,000 patients with newly diagnosed cancer in Medicaid expansion states, the 2% decrease in the hazard of death would translate to 1,384 lives saved annually.

The benefit was primarily observed in patients with nonmetastatic cancer. For patients with stage I-III cancer, the risk of death was increased in nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P < .001) and unchanged in expansion states (HR, 0.99; P = .64). Mortality significantly improved in expansion states vs. nonexpansion states (HR, 1.05; P = .003).

For patients with stage IV cancer, both expansion and nonexpansion states had improvements in mortality, but the differences were not significant.

“Earlier stage at diagnosis appears to explain the mortality improvement,” wrote study author Miranda Lam, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

Clinical benefits, ‘no economic downside’

Under the Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, states have the option of expanding Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level. As of March 2020, 36 states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid, with more than 20 million residents obtaining coverage.

Previous studies have associated Medicaid expansion with fewer patients being uninsured, increased cancer screening, and earlier stage of diagnosis, as well as reduced racial disparities in access to high-volume hospitals for cancer surgery and increased rates of cancer surgery among low-income patients.

“This study adds to an increasingly large body of research finding that Medicaid expansion has improved our ability to fight cancer,” said Coleman Drake, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in this study.

“Obtaining health insurance through Medicaid allows patients to receive recommended preventive cancer screenings, which explains the increase in early-stage diagnosis rates. Detecting cancer early is critical for successful cancer treatment,” Dr. Drake noted.

“It is hard to overstate the positive effects of Medicaid expansion on health outcomes. At the same time, concerns that Medicaid expansion would be costly to state governments’ budgets have not been realized. In short, Medicaid expansion yields many benefits and has no economic downside for state policymakers. Clinical and economic evidence make an overwhelming case for states to expand Medicaid,” Dr. Drake said.

Significant difference for lung cancer

Most patients in this study were women (73.6%), and the patients’ mean age was 54.8 years (range, 40-64 years). Patients had newly diagnosed breast cancer (52.2%), colorectal cancer (21.3%), and lung cancer (26.5%).

The benefits of Medicaid expansion persisted after adjustment for education, income, insurance, and race.

The lower mortality in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states was similar across all three cancer types. However, in stratified analyses, the difference was significant only for lung cancer (P = .03).

“Lung cancer has a higher mortality rate than breast and colorectal cancer, and with longer follow-up, it is possible that the lower mortality rates seen for breast and colorectal cancer may also become significant,” the authors wrote.

This research was funded by Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Drake had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lam MB et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2024366.

FROM JAMA OPEN NETWORK

Survey finds Black, Hispanic patients may prefer race-concordant dermatologists, highlighting opportunities for changes in education and practice

, according to a patient survey.

In the survey, 42% of self-identified Black patients and 44% of self-identified Hispanic patients assigned some level of importance to the race or ethnicity of their dermatologist. Of patients self-identified as White, the figure was 2%, which was significantly lower (P less than .001).

Responses to the survey indicated that there is concern among non-White patients that White physicians are not fully sensitive to the clinical issues presented by their skin type. For example, 22% of Hispanic patients and 21% of Black patients agreed that a race-concordant physician would be better trained to treat their skin.

The results of the survey were recently published in a Research Letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

When patients were asked to agree or disagree with the statement that non-White patients receive the same quality of care as White patients, about a third disagreed, “but about half said they were unsure, which I interpret basically as a negative answer,” reported the lead author, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“These data are a call to action. Certainly, we need to diversify our workforce to mirror the overall population, but we can also do more to improve training for dermatologic diseases across skin types,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Ensuring all skin types are represented in all dermatologic education, from resident book clubs to the national stage is but one step to making dermatology more inclusive and prepared to care for all patients,” he added.

Ninety-two patients receiving dermatology care at Dr. Friedman’s institution completed the survey. Fifty identified themselves as White, nine as Hispanic, and 33 as Black. Allowing patients to self-identify race was an important feature of this survey, according to Dr. Friedman.

“Something I really struggle with is terminology. Are race and ethnicity the appropriate terms when discussing different skin types and tones? It is so easy to misuse even validated tools. The Fitzpatrick Scale, for example, requires patients to relay how easily they burn, but reveals nothing about how patients refer to their skin tone,” Dr. Friedman explained. “We need to reset how we characterize and categorize skin types.”

Among those who assigned at least some importance to having a dermatologist of the same race or ethnicity, the most common reason was that such physicians “are better able to listen and relate to me.” Thirty percent of Black patients and 22% of Hispanic patients agreed with this statement. The perception that such physicians are better trained to treat non-White skin was the next most common reason.

The results of the survey emphasize the importance of ensuring that there is comprehensive training in managing all skin types and that physicians receive rigorous implicit bias and cultural sensitivity training in order to win patient trust, according to Dr. Friedman. He suggested that the perception that White physicians might not provide optimal care to non-White patients by study participants “has some validity. Structural racism in medicine is well-documented, and dermatologists have already begun to combat this on several fronts.”

In fact, the process of conducting and analyzing data from this survey proved to be its own lesson in sociocultural sensitivity, he said.

After a draft completed peer review and was accepted for publication, Dr. Friedman was confronted with numerous criticisms of the language that was used. In particular, one of his former residents, Misty Eleryan, MD, who is now a Mohs Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, was instrumental in pointing out problems. Ultimately, he withdrew the paper to rephrase the findings.

“It was not until then that I also learned that there is a JAAD Sensitivity Workgroup, which was very helpful in identifying issues we had overlooked,” Dr. Friedman said. For example, he had used the term “minorities” for non-White populations, which is not only inaccurate in many situations but has a pejorative undertone.

“It is important to recognize that the impact is more important than the intention,” said Dr. Friedman, who reported that he learned a lot in this process.

It is the need for this type of augmented sensitivity that the survey underscores, he added. He called for cultural sensitivity to be part of medical training to undo unrecognized bias, and said, “We need to understand how our patients perceive us.”

SOURCE: Friedman A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 16;S0190-9622(20)32620-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.032.

, according to a patient survey.

In the survey, 42% of self-identified Black patients and 44% of self-identified Hispanic patients assigned some level of importance to the race or ethnicity of their dermatologist. Of patients self-identified as White, the figure was 2%, which was significantly lower (P less than .001).

Responses to the survey indicated that there is concern among non-White patients that White physicians are not fully sensitive to the clinical issues presented by their skin type. For example, 22% of Hispanic patients and 21% of Black patients agreed that a race-concordant physician would be better trained to treat their skin.

The results of the survey were recently published in a Research Letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

When patients were asked to agree or disagree with the statement that non-White patients receive the same quality of care as White patients, about a third disagreed, “but about half said they were unsure, which I interpret basically as a negative answer,” reported the lead author, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“These data are a call to action. Certainly, we need to diversify our workforce to mirror the overall population, but we can also do more to improve training for dermatologic diseases across skin types,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Ensuring all skin types are represented in all dermatologic education, from resident book clubs to the national stage is but one step to making dermatology more inclusive and prepared to care for all patients,” he added.

Ninety-two patients receiving dermatology care at Dr. Friedman’s institution completed the survey. Fifty identified themselves as White, nine as Hispanic, and 33 as Black. Allowing patients to self-identify race was an important feature of this survey, according to Dr. Friedman.

“Something I really struggle with is terminology. Are race and ethnicity the appropriate terms when discussing different skin types and tones? It is so easy to misuse even validated tools. The Fitzpatrick Scale, for example, requires patients to relay how easily they burn, but reveals nothing about how patients refer to their skin tone,” Dr. Friedman explained. “We need to reset how we characterize and categorize skin types.”

Among those who assigned at least some importance to having a dermatologist of the same race or ethnicity, the most common reason was that such physicians “are better able to listen and relate to me.” Thirty percent of Black patients and 22% of Hispanic patients agreed with this statement. The perception that such physicians are better trained to treat non-White skin was the next most common reason.

The results of the survey emphasize the importance of ensuring that there is comprehensive training in managing all skin types and that physicians receive rigorous implicit bias and cultural sensitivity training in order to win patient trust, according to Dr. Friedman. He suggested that the perception that White physicians might not provide optimal care to non-White patients by study participants “has some validity. Structural racism in medicine is well-documented, and dermatologists have already begun to combat this on several fronts.”

In fact, the process of conducting and analyzing data from this survey proved to be its own lesson in sociocultural sensitivity, he said.

After a draft completed peer review and was accepted for publication, Dr. Friedman was confronted with numerous criticisms of the language that was used. In particular, one of his former residents, Misty Eleryan, MD, who is now a Mohs Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, was instrumental in pointing out problems. Ultimately, he withdrew the paper to rephrase the findings.

“It was not until then that I also learned that there is a JAAD Sensitivity Workgroup, which was very helpful in identifying issues we had overlooked,” Dr. Friedman said. For example, he had used the term “minorities” for non-White populations, which is not only inaccurate in many situations but has a pejorative undertone.

“It is important to recognize that the impact is more important than the intention,” said Dr. Friedman, who reported that he learned a lot in this process.

It is the need for this type of augmented sensitivity that the survey underscores, he added. He called for cultural sensitivity to be part of medical training to undo unrecognized bias, and said, “We need to understand how our patients perceive us.”

SOURCE: Friedman A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 16;S0190-9622(20)32620-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.032.

, according to a patient survey.

In the survey, 42% of self-identified Black patients and 44% of self-identified Hispanic patients assigned some level of importance to the race or ethnicity of their dermatologist. Of patients self-identified as White, the figure was 2%, which was significantly lower (P less than .001).

Responses to the survey indicated that there is concern among non-White patients that White physicians are not fully sensitive to the clinical issues presented by their skin type. For example, 22% of Hispanic patients and 21% of Black patients agreed that a race-concordant physician would be better trained to treat their skin.

The results of the survey were recently published in a Research Letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

When patients were asked to agree or disagree with the statement that non-White patients receive the same quality of care as White patients, about a third disagreed, “but about half said they were unsure, which I interpret basically as a negative answer,” reported the lead author, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“These data are a call to action. Certainly, we need to diversify our workforce to mirror the overall population, but we can also do more to improve training for dermatologic diseases across skin types,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview.

“Ensuring all skin types are represented in all dermatologic education, from resident book clubs to the national stage is but one step to making dermatology more inclusive and prepared to care for all patients,” he added.

Ninety-two patients receiving dermatology care at Dr. Friedman’s institution completed the survey. Fifty identified themselves as White, nine as Hispanic, and 33 as Black. Allowing patients to self-identify race was an important feature of this survey, according to Dr. Friedman.

“Something I really struggle with is terminology. Are race and ethnicity the appropriate terms when discussing different skin types and tones? It is so easy to misuse even validated tools. The Fitzpatrick Scale, for example, requires patients to relay how easily they burn, but reveals nothing about how patients refer to their skin tone,” Dr. Friedman explained. “We need to reset how we characterize and categorize skin types.”

Among those who assigned at least some importance to having a dermatologist of the same race or ethnicity, the most common reason was that such physicians “are better able to listen and relate to me.” Thirty percent of Black patients and 22% of Hispanic patients agreed with this statement. The perception that such physicians are better trained to treat non-White skin was the next most common reason.

The results of the survey emphasize the importance of ensuring that there is comprehensive training in managing all skin types and that physicians receive rigorous implicit bias and cultural sensitivity training in order to win patient trust, according to Dr. Friedman. He suggested that the perception that White physicians might not provide optimal care to non-White patients by study participants “has some validity. Structural racism in medicine is well-documented, and dermatologists have already begun to combat this on several fronts.”

In fact, the process of conducting and analyzing data from this survey proved to be its own lesson in sociocultural sensitivity, he said.

After a draft completed peer review and was accepted for publication, Dr. Friedman was confronted with numerous criticisms of the language that was used. In particular, one of his former residents, Misty Eleryan, MD, who is now a Mohs Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, was instrumental in pointing out problems. Ultimately, he withdrew the paper to rephrase the findings.

“It was not until then that I also learned that there is a JAAD Sensitivity Workgroup, which was very helpful in identifying issues we had overlooked,” Dr. Friedman said. For example, he had used the term “minorities” for non-White populations, which is not only inaccurate in many situations but has a pejorative undertone.

“It is important to recognize that the impact is more important than the intention,” said Dr. Friedman, who reported that he learned a lot in this process.

It is the need for this type of augmented sensitivity that the survey underscores, he added. He called for cultural sensitivity to be part of medical training to undo unrecognized bias, and said, “We need to understand how our patients perceive us.”

SOURCE: Friedman A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 16;S0190-9622(20)32620-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.032.

Prophylactic HIV treatment in female STI patients is rare

reported Kirk D. Henny, PhD, and colleagues of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an effort to quantify HIV testing rates as well as the rate of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women with gonorrhea or syphilis, Dr. Henny and his colleagues performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 13,074 female patients aged 15-64 diagnosed with a STI in the absence of HIV. Data was pulled in 2017 from the IBM MarketScan commercial and Medicaid insurance databases, and the research was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Medicaid patients were more likely to be tested for HIV

A total of 3,709 patients with commercial insurance were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,696 with syphilis. Among those with Medicaid, 6,172 were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,497 with syphilis. Medicaid patients diagnosed with either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than the commercially insured patients. With an adjusted prevalence ratio, patients commercially insured with had either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than patients who had no STI. Prophylactic treatment rates were similar in both insurance groups: 0.15% in the commercial insurance group and 0.26% in the Medicaid group. No patient from either group who was diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis and subsequently tested for HIV received pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) treatment.

STI diagnosis is a significant indicator of future HIV

Female patients diagnosed with either STI are more likely to contract HIV, the researchers noted. They cautioned that their findings of low HIV testing rates and the absence of prophylactic treatment means that “these missed opportunities for health care professionals to intervene with female patients diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis might have contributed to HIV infections that could have been averted.”

The researchers also pointed out that, in a recent analysis of pharmacy data, prophylactic prescribing for female patients with clinical indications for PrEP was 6.6%, less than one-third the coverage provided to male patients.

Future research should target understanding “individual and contextual factors associated with low HIV testing” and PrEP treatment in female patients, especially those with STIs, Dr. Henny and his colleagues advised.

In a separate interview, Constance Bohon, MD FACOG, observed: “The authors present data to document the low incidence of pre-exposure prophylaxis in women who are at substantial risk of acquiring HIV and possible causes for the low utilization of this treatment.” It is important to identify barriers to diagnosis, counseling, and treatment, she advised.

“Multicenter studies to determine the best methodologies to improve the identification, management, and treatment of these at-risk women need to be done, and the conclusions disseminated to health care providers caring for women,” Dr. Bohon said.

PrEP is an important, simple strategy for reducing HIV transmission

“Pre-exposure prophylaxis has been demonstrated to decrease HIV acquisition in those at risk by up to 90% when taken appropriately,” and yet prescribing rates are extremely low (2%-6%) in at-risk women and especially women of color. These disparities have only grown over time, with prophylactic prescriptions for women at 5% between 2012 and 2017, compared with 68% for men, Catherine S. Eppes, MD, MPH, and Jennifer McKinney, MD, MPH, said in a related editorial commenting on the Research Letter by Dr. Henny and colleagues in Obstetrics & Gynecology (2020 Dec;136[6]:1080-2).

Given the abundant research demonstrating the importance and ease of prescribing PrEP, the question remains: “why does preexposure prophylaxis uptake remain so low, especially for women and women of color? There are three important issues about preexposure prophylaxis raised by this study: the research gap, the implementation gap, and the effect of systemic racism and bias,” noted Dr. Eppes and Dr. McKinney.

Women constitute a significant portion of the population that would benefit from HIV-prevention strategies, yet they continue to be excluded from research, they noted. “Much focus on research into barriers and implementation interventions for preexposure prophylaxis have focused on men who have sex with men and transgender women,” the authors of the editorial wrote.

Most women eligible for treatment would be willing to consider it if they were aware of the option, but numerous studies have cited a lack of awareness, especially among high-risk women of color in the United States, Dr. Eppes and Dr. McKinney noted.

Clinicians also need to add it to their growing checklist of mandatory appointment discussion topics, the editorialists said. “We propose standardized inclusion of preexposure prophylaxis counseling during reproductive healthcare visits. This could be aided through an electronic medical record-based best practice advisory alert. … Standardized order sets with the medication and laboratory studies necessary for safe monitoring could facilitate ease of incorporating into routine visits,” they suggested.

“Preexposure prophylaxis is extremely effective in preventing HIV, is safe, and is the only prevention method that leaves control entirely in the hands of the female partner. As a specialty, we have a responsibility to make sure our patients know about this option,” the editorialists concluded.

The authors had no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Bohon had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Henny KD et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec;136(6):1083-5.

reported Kirk D. Henny, PhD, and colleagues of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an effort to quantify HIV testing rates as well as the rate of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women with gonorrhea or syphilis, Dr. Henny and his colleagues performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 13,074 female patients aged 15-64 diagnosed with a STI in the absence of HIV. Data was pulled in 2017 from the IBM MarketScan commercial and Medicaid insurance databases, and the research was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Medicaid patients were more likely to be tested for HIV

A total of 3,709 patients with commercial insurance were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,696 with syphilis. Among those with Medicaid, 6,172 were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,497 with syphilis. Medicaid patients diagnosed with either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than the commercially insured patients. With an adjusted prevalence ratio, patients commercially insured with had either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than patients who had no STI. Prophylactic treatment rates were similar in both insurance groups: 0.15% in the commercial insurance group and 0.26% in the Medicaid group. No patient from either group who was diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis and subsequently tested for HIV received pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) treatment.

STI diagnosis is a significant indicator of future HIV

Female patients diagnosed with either STI are more likely to contract HIV, the researchers noted. They cautioned that their findings of low HIV testing rates and the absence of prophylactic treatment means that “these missed opportunities for health care professionals to intervene with female patients diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis might have contributed to HIV infections that could have been averted.”

The researchers also pointed out that, in a recent analysis of pharmacy data, prophylactic prescribing for female patients with clinical indications for PrEP was 6.6%, less than one-third the coverage provided to male patients.

Future research should target understanding “individual and contextual factors associated with low HIV testing” and PrEP treatment in female patients, especially those with STIs, Dr. Henny and his colleagues advised.

In a separate interview, Constance Bohon, MD FACOG, observed: “The authors present data to document the low incidence of pre-exposure prophylaxis in women who are at substantial risk of acquiring HIV and possible causes for the low utilization of this treatment.” It is important to identify barriers to diagnosis, counseling, and treatment, she advised.

“Multicenter studies to determine the best methodologies to improve the identification, management, and treatment of these at-risk women need to be done, and the conclusions disseminated to health care providers caring for women,” Dr. Bohon said.

PrEP is an important, simple strategy for reducing HIV transmission

“Pre-exposure prophylaxis has been demonstrated to decrease HIV acquisition in those at risk by up to 90% when taken appropriately,” and yet prescribing rates are extremely low (2%-6%) in at-risk women and especially women of color. These disparities have only grown over time, with prophylactic prescriptions for women at 5% between 2012 and 2017, compared with 68% for men, Catherine S. Eppes, MD, MPH, and Jennifer McKinney, MD, MPH, said in a related editorial commenting on the Research Letter by Dr. Henny and colleagues in Obstetrics & Gynecology (2020 Dec;136[6]:1080-2).

Given the abundant research demonstrating the importance and ease of prescribing PrEP, the question remains: “why does preexposure prophylaxis uptake remain so low, especially for women and women of color? There are three important issues about preexposure prophylaxis raised by this study: the research gap, the implementation gap, and the effect of systemic racism and bias,” noted Dr. Eppes and Dr. McKinney.

Women constitute a significant portion of the population that would benefit from HIV-prevention strategies, yet they continue to be excluded from research, they noted. “Much focus on research into barriers and implementation interventions for preexposure prophylaxis have focused on men who have sex with men and transgender women,” the authors of the editorial wrote.

Most women eligible for treatment would be willing to consider it if they were aware of the option, but numerous studies have cited a lack of awareness, especially among high-risk women of color in the United States, Dr. Eppes and Dr. McKinney noted.

Clinicians also need to add it to their growing checklist of mandatory appointment discussion topics, the editorialists said. “We propose standardized inclusion of preexposure prophylaxis counseling during reproductive healthcare visits. This could be aided through an electronic medical record-based best practice advisory alert. … Standardized order sets with the medication and laboratory studies necessary for safe monitoring could facilitate ease of incorporating into routine visits,” they suggested.

“Preexposure prophylaxis is extremely effective in preventing HIV, is safe, and is the only prevention method that leaves control entirely in the hands of the female partner. As a specialty, we have a responsibility to make sure our patients know about this option,” the editorialists concluded.

The authors had no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Bohon had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Henny KD et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec;136(6):1083-5.

reported Kirk D. Henny, PhD, and colleagues of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In an effort to quantify HIV testing rates as well as the rate of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women with gonorrhea or syphilis, Dr. Henny and his colleagues performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis of 13,074 female patients aged 15-64 diagnosed with a STI in the absence of HIV. Data was pulled in 2017 from the IBM MarketScan commercial and Medicaid insurance databases, and the research was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Medicaid patients were more likely to be tested for HIV

A total of 3,709 patients with commercial insurance were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,696 with syphilis. Among those with Medicaid, 6,172 were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 1,497 with syphilis. Medicaid patients diagnosed with either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than the commercially insured patients. With an adjusted prevalence ratio, patients commercially insured with had either STI were more likely to be tested for HIV than patients who had no STI. Prophylactic treatment rates were similar in both insurance groups: 0.15% in the commercial insurance group and 0.26% in the Medicaid group. No patient from either group who was diagnosed with gonorrhea or syphilis and subsequently tested for HIV received pre-exposure prophylactic (PrEP) treatment.

STI diagnosis is a significant indicator of future HIV