User login

Clean indoor air is vital for infection control

Health workers already know that indoor air quality can be as important to human health as clean water and uncontaminated food. But before the COVID-19 pandemic, its importance in the prevention of respiratory illnesses outside of health circles was only whispered about.

Now, a team of nearly 40 scientists from 14 countries is calling for “a paradigm shift,” so that improvements in indoor air quality are viewed as essential to curb respiratory infections.

Most countries do not have indoor air-quality standards, the scientists point out in their recent report, and those that do often fall short in scope and enforcement.

“We expect everywhere in the world to have clean water flowing from our taps. In most parts of the developed world, it is happening and we take it completely for granted,” said lead investigator Lidia Morawska, PhD, of the International Laboratory for Air Quality and Health at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

But bacteria and viruses can circulate freely in the air, and “no one thinks about this, whatsoever, apart from health care facilities,” she said.

A first step is to recognize the risk posed by airborne pathogens, something not yet universally acknowledged. The investigators also want the World Health Organization to extend its guidelines to cover airborne pathogens, and for ventilation standards to include higher airflow and filtration rates.

Germany has been at the forefront of air-quality measures, Dr. Morawska said. Years ago, she observed a monitor showing the carbon dioxide level and relative humidity in the room where she was attending a meeting. The screen was accompanied by red, yellow, and green signals to communicate risk. Such indicators are also commonly displayed in German schools so teachers know when to open the windows or adjust the ventilation.

Monitors show carbon dioxide levels

But this is not yet being done in most other countries, Dr. Morawska said. Levels of carbon dioxide are one measure of indoor air quality, but they serve as a proxy for ventilation, she pointed out. Although the technology is available, sensors that can test a variety of components in a building in real time are not yet affordable.

Dr. Morawska envisions a future where the air quality numbers of the places people frequent are displayed so they know the risk for airborne transmission of respiratory illnesses. And people can begin to expect clean indoor air when they enter a business, office, or entertainment space and request changes when the air quality dips and improvement is needed, she said.

It is a daunting challenge to clean indoor air for several reasons. Air is not containable in the same way water is, which makes it difficult to trace contaminants. And infections transmitted through dirty water and food are usually evident immediately, whereas infections transmitted through airborne pathogens can take days to develop. Plus, the necessary infrastructure changes will be expensive.

However, the initial cost required to change the flow and quality of indoor air might be less than the cost of infections, the scientists pointed out. It is estimated that the global harm caused by COVID-19 alone costs $1 trillion each month.

“In the United States, the yearly cost – direct and indirect – of influenza has been calculated at $11.2 billion. For respiratory infections other than influenza, the yearly cost stood at $40 billion,” the team noted.

“If even half of this was caused by inhalation, we are still talking about massive costs,” said Dr. Morawska.

Bigger is not always better

It is tempting to see the solution as increased ventilation, said Ehsan Mousavi, PhD, assistant professor of construction science and management at Clemson (S.C.) University, who studies indoor air quality and ventilation in hospitals.

“We are ventilating the heck out of hospitals,” he said in an interview. But there is much debate about how much ventilation is the right amount. Too much and “you can blow pathogens into an open wound,” he explained. “Bigger is not always better.”

And there is still debate about the best mix of outside and recirculated air. An increase in the intake of outdoor air can refresh indoor air if it is clean, but that depends on where you live, he pointed out.

The mix used in most standard office buildings is 15% outside air and 85% recirculated air, Dr. Mousavi said. Boosting the percentage of outside air increases costs and energy use.

In fact, it can take five times more energy to ventilate hospital spaces than office spaces, he reported.

Engineers searching for clean-air solutions need to know what particulates are in the air and whether they are harmful to humans, but the sensors currently available can’t identify whether a virus is present in real time.

Samples have to be taken to a lab and, “by the time you know a virus was in the space, the moment is gone,” Dr. Mousavi explained.

More research is needed. “We need a reasonable answer that looks at the problem holistically, not just from the infectious disease perspective,” he said.

Hydrating indoor air

Research is making it clear that health care environments can play a significant role in patient recovery, according to Stephanie Taylor, MD. Dr. Taylor is president of Building4Health, which she founded to help businesses assess the quality of air in their buildings and find solutions. The company uses an algorithm to arrive at a health assessment score.

Air hydration is the most important aspect to target, she said.

Since the 1980s, research has shown that a relative humidity of 40%-60% is healthy for humans, she said. Currently, in an office building in a winter climate, the humidity level is more like 20%.

Canada is the first country to officially recommend the 40%-60% range for senior citizen centers and residential homes.

“Properly hydrated air supports our immune system and prevents skin problems and respiratory problems. It also inactivates many bacteria and viruses,” Dr. Taylor explained. Inhaling dry air compromises the ability of the body to restrict influenza virus infection, researchers showed in a 2019 study.

In the case of COVID-19, as virus particles attach to water molecules, they get bigger and heavier and eventually drop out of the breathing zone and onto surfaces where they can be wiped away, she explained.

But when the particles “are very small – like 5 microns in diameter – and you inhale them, they can lodge deep in the lungs,” she said.

In properly hydrated air, particles will be larger – about 10-20 microns when they attach to the water vapor – so they will get stuck in the nose or the back of the throat, where they can be washed away by mucous and not travel to the lungs.

“Indoor air metrics” can support our health or contribute to disease, “not just over time, but quickly, within minutes or hours,” she said.

No one expects the world’s building stock to suddenly upgrade to the ideal air quality. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t move in that direction,” Dr. Taylor said. Changes can start small and gradually increase.

New research targets indoor air

Humidity is one of the key areas for current research, said Karl Rockne, PhD, director of the environmental engineering program at the National Science Foundation.

“When a virus comes out, it’s not just a naked virus, which is exceptionally small. It’s a virus encapsulated in liquid. And that’s why the humidity is so key. The degree of humidity can determine how fast the water evaporates from the particle,” he said in an interview.

In the wake of COVID-19, his institution is funding more cross-disciplinary research in biology, building science, architecture, and physics, he pointed out.

One such effort involved the development of a sensor that can capture live COVID-19 virus. This so-called “smoking gun,” which proved that the virus can spread through the air, took the combined expertise of professionals in medicine, engineering, and several other disciplines.

Currently, investigators are examining indoor air quality and water supplies in offices that have been left empty during the pandemic, and the effect they will have on human health. And others are looking at the way outside air quality affects indoor air quality, particularly where outdoor air quality is poor, such as in areas experiencing wildfires.

So will COVID-19 be the catalyst that finally drives changes to building design, regulation, and public expectations of air quality in the spaces where we spend close to 90% of our time?

“If not COVID, what else? It affected every country, every sector,” Dr. Morawska said. “There’s enough momentum now to do something about this. And enough realization there is a problem.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health workers already know that indoor air quality can be as important to human health as clean water and uncontaminated food. But before the COVID-19 pandemic, its importance in the prevention of respiratory illnesses outside of health circles was only whispered about.

Now, a team of nearly 40 scientists from 14 countries is calling for “a paradigm shift,” so that improvements in indoor air quality are viewed as essential to curb respiratory infections.

Most countries do not have indoor air-quality standards, the scientists point out in their recent report, and those that do often fall short in scope and enforcement.

“We expect everywhere in the world to have clean water flowing from our taps. In most parts of the developed world, it is happening and we take it completely for granted,” said lead investigator Lidia Morawska, PhD, of the International Laboratory for Air Quality and Health at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

But bacteria and viruses can circulate freely in the air, and “no one thinks about this, whatsoever, apart from health care facilities,” she said.

A first step is to recognize the risk posed by airborne pathogens, something not yet universally acknowledged. The investigators also want the World Health Organization to extend its guidelines to cover airborne pathogens, and for ventilation standards to include higher airflow and filtration rates.

Germany has been at the forefront of air-quality measures, Dr. Morawska said. Years ago, she observed a monitor showing the carbon dioxide level and relative humidity in the room where she was attending a meeting. The screen was accompanied by red, yellow, and green signals to communicate risk. Such indicators are also commonly displayed in German schools so teachers know when to open the windows or adjust the ventilation.

Monitors show carbon dioxide levels

But this is not yet being done in most other countries, Dr. Morawska said. Levels of carbon dioxide are one measure of indoor air quality, but they serve as a proxy for ventilation, she pointed out. Although the technology is available, sensors that can test a variety of components in a building in real time are not yet affordable.

Dr. Morawska envisions a future where the air quality numbers of the places people frequent are displayed so they know the risk for airborne transmission of respiratory illnesses. And people can begin to expect clean indoor air when they enter a business, office, or entertainment space and request changes when the air quality dips and improvement is needed, she said.

It is a daunting challenge to clean indoor air for several reasons. Air is not containable in the same way water is, which makes it difficult to trace contaminants. And infections transmitted through dirty water and food are usually evident immediately, whereas infections transmitted through airborne pathogens can take days to develop. Plus, the necessary infrastructure changes will be expensive.

However, the initial cost required to change the flow and quality of indoor air might be less than the cost of infections, the scientists pointed out. It is estimated that the global harm caused by COVID-19 alone costs $1 trillion each month.

“In the United States, the yearly cost – direct and indirect – of influenza has been calculated at $11.2 billion. For respiratory infections other than influenza, the yearly cost stood at $40 billion,” the team noted.

“If even half of this was caused by inhalation, we are still talking about massive costs,” said Dr. Morawska.

Bigger is not always better

It is tempting to see the solution as increased ventilation, said Ehsan Mousavi, PhD, assistant professor of construction science and management at Clemson (S.C.) University, who studies indoor air quality and ventilation in hospitals.

“We are ventilating the heck out of hospitals,” he said in an interview. But there is much debate about how much ventilation is the right amount. Too much and “you can blow pathogens into an open wound,” he explained. “Bigger is not always better.”

And there is still debate about the best mix of outside and recirculated air. An increase in the intake of outdoor air can refresh indoor air if it is clean, but that depends on where you live, he pointed out.

The mix used in most standard office buildings is 15% outside air and 85% recirculated air, Dr. Mousavi said. Boosting the percentage of outside air increases costs and energy use.

In fact, it can take five times more energy to ventilate hospital spaces than office spaces, he reported.

Engineers searching for clean-air solutions need to know what particulates are in the air and whether they are harmful to humans, but the sensors currently available can’t identify whether a virus is present in real time.

Samples have to be taken to a lab and, “by the time you know a virus was in the space, the moment is gone,” Dr. Mousavi explained.

More research is needed. “We need a reasonable answer that looks at the problem holistically, not just from the infectious disease perspective,” he said.

Hydrating indoor air

Research is making it clear that health care environments can play a significant role in patient recovery, according to Stephanie Taylor, MD. Dr. Taylor is president of Building4Health, which she founded to help businesses assess the quality of air in their buildings and find solutions. The company uses an algorithm to arrive at a health assessment score.

Air hydration is the most important aspect to target, she said.

Since the 1980s, research has shown that a relative humidity of 40%-60% is healthy for humans, she said. Currently, in an office building in a winter climate, the humidity level is more like 20%.

Canada is the first country to officially recommend the 40%-60% range for senior citizen centers and residential homes.

“Properly hydrated air supports our immune system and prevents skin problems and respiratory problems. It also inactivates many bacteria and viruses,” Dr. Taylor explained. Inhaling dry air compromises the ability of the body to restrict influenza virus infection, researchers showed in a 2019 study.

In the case of COVID-19, as virus particles attach to water molecules, they get bigger and heavier and eventually drop out of the breathing zone and onto surfaces where they can be wiped away, she explained.

But when the particles “are very small – like 5 microns in diameter – and you inhale them, they can lodge deep in the lungs,” she said.

In properly hydrated air, particles will be larger – about 10-20 microns when they attach to the water vapor – so they will get stuck in the nose or the back of the throat, where they can be washed away by mucous and not travel to the lungs.

“Indoor air metrics” can support our health or contribute to disease, “not just over time, but quickly, within minutes or hours,” she said.

No one expects the world’s building stock to suddenly upgrade to the ideal air quality. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t move in that direction,” Dr. Taylor said. Changes can start small and gradually increase.

New research targets indoor air

Humidity is one of the key areas for current research, said Karl Rockne, PhD, director of the environmental engineering program at the National Science Foundation.

“When a virus comes out, it’s not just a naked virus, which is exceptionally small. It’s a virus encapsulated in liquid. And that’s why the humidity is so key. The degree of humidity can determine how fast the water evaporates from the particle,” he said in an interview.

In the wake of COVID-19, his institution is funding more cross-disciplinary research in biology, building science, architecture, and physics, he pointed out.

One such effort involved the development of a sensor that can capture live COVID-19 virus. This so-called “smoking gun,” which proved that the virus can spread through the air, took the combined expertise of professionals in medicine, engineering, and several other disciplines.

Currently, investigators are examining indoor air quality and water supplies in offices that have been left empty during the pandemic, and the effect they will have on human health. And others are looking at the way outside air quality affects indoor air quality, particularly where outdoor air quality is poor, such as in areas experiencing wildfires.

So will COVID-19 be the catalyst that finally drives changes to building design, regulation, and public expectations of air quality in the spaces where we spend close to 90% of our time?

“If not COVID, what else? It affected every country, every sector,” Dr. Morawska said. “There’s enough momentum now to do something about this. And enough realization there is a problem.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health workers already know that indoor air quality can be as important to human health as clean water and uncontaminated food. But before the COVID-19 pandemic, its importance in the prevention of respiratory illnesses outside of health circles was only whispered about.

Now, a team of nearly 40 scientists from 14 countries is calling for “a paradigm shift,” so that improvements in indoor air quality are viewed as essential to curb respiratory infections.

Most countries do not have indoor air-quality standards, the scientists point out in their recent report, and those that do often fall short in scope and enforcement.

“We expect everywhere in the world to have clean water flowing from our taps. In most parts of the developed world, it is happening and we take it completely for granted,” said lead investigator Lidia Morawska, PhD, of the International Laboratory for Air Quality and Health at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia.

But bacteria and viruses can circulate freely in the air, and “no one thinks about this, whatsoever, apart from health care facilities,” she said.

A first step is to recognize the risk posed by airborne pathogens, something not yet universally acknowledged. The investigators also want the World Health Organization to extend its guidelines to cover airborne pathogens, and for ventilation standards to include higher airflow and filtration rates.

Germany has been at the forefront of air-quality measures, Dr. Morawska said. Years ago, she observed a monitor showing the carbon dioxide level and relative humidity in the room where she was attending a meeting. The screen was accompanied by red, yellow, and green signals to communicate risk. Such indicators are also commonly displayed in German schools so teachers know when to open the windows or adjust the ventilation.

Monitors show carbon dioxide levels

But this is not yet being done in most other countries, Dr. Morawska said. Levels of carbon dioxide are one measure of indoor air quality, but they serve as a proxy for ventilation, she pointed out. Although the technology is available, sensors that can test a variety of components in a building in real time are not yet affordable.

Dr. Morawska envisions a future where the air quality numbers of the places people frequent are displayed so they know the risk for airborne transmission of respiratory illnesses. And people can begin to expect clean indoor air when they enter a business, office, or entertainment space and request changes when the air quality dips and improvement is needed, she said.

It is a daunting challenge to clean indoor air for several reasons. Air is not containable in the same way water is, which makes it difficult to trace contaminants. And infections transmitted through dirty water and food are usually evident immediately, whereas infections transmitted through airborne pathogens can take days to develop. Plus, the necessary infrastructure changes will be expensive.

However, the initial cost required to change the flow and quality of indoor air might be less than the cost of infections, the scientists pointed out. It is estimated that the global harm caused by COVID-19 alone costs $1 trillion each month.

“In the United States, the yearly cost – direct and indirect – of influenza has been calculated at $11.2 billion. For respiratory infections other than influenza, the yearly cost stood at $40 billion,” the team noted.

“If even half of this was caused by inhalation, we are still talking about massive costs,” said Dr. Morawska.

Bigger is not always better

It is tempting to see the solution as increased ventilation, said Ehsan Mousavi, PhD, assistant professor of construction science and management at Clemson (S.C.) University, who studies indoor air quality and ventilation in hospitals.

“We are ventilating the heck out of hospitals,” he said in an interview. But there is much debate about how much ventilation is the right amount. Too much and “you can blow pathogens into an open wound,” he explained. “Bigger is not always better.”

And there is still debate about the best mix of outside and recirculated air. An increase in the intake of outdoor air can refresh indoor air if it is clean, but that depends on where you live, he pointed out.

The mix used in most standard office buildings is 15% outside air and 85% recirculated air, Dr. Mousavi said. Boosting the percentage of outside air increases costs and energy use.

In fact, it can take five times more energy to ventilate hospital spaces than office spaces, he reported.

Engineers searching for clean-air solutions need to know what particulates are in the air and whether they are harmful to humans, but the sensors currently available can’t identify whether a virus is present in real time.

Samples have to be taken to a lab and, “by the time you know a virus was in the space, the moment is gone,” Dr. Mousavi explained.

More research is needed. “We need a reasonable answer that looks at the problem holistically, not just from the infectious disease perspective,” he said.

Hydrating indoor air

Research is making it clear that health care environments can play a significant role in patient recovery, according to Stephanie Taylor, MD. Dr. Taylor is president of Building4Health, which she founded to help businesses assess the quality of air in their buildings and find solutions. The company uses an algorithm to arrive at a health assessment score.

Air hydration is the most important aspect to target, she said.

Since the 1980s, research has shown that a relative humidity of 40%-60% is healthy for humans, she said. Currently, in an office building in a winter climate, the humidity level is more like 20%.

Canada is the first country to officially recommend the 40%-60% range for senior citizen centers and residential homes.

“Properly hydrated air supports our immune system and prevents skin problems and respiratory problems. It also inactivates many bacteria and viruses,” Dr. Taylor explained. Inhaling dry air compromises the ability of the body to restrict influenza virus infection, researchers showed in a 2019 study.

In the case of COVID-19, as virus particles attach to water molecules, they get bigger and heavier and eventually drop out of the breathing zone and onto surfaces where they can be wiped away, she explained.

But when the particles “are very small – like 5 microns in diameter – and you inhale them, they can lodge deep in the lungs,” she said.

In properly hydrated air, particles will be larger – about 10-20 microns when they attach to the water vapor – so they will get stuck in the nose or the back of the throat, where they can be washed away by mucous and not travel to the lungs.

“Indoor air metrics” can support our health or contribute to disease, “not just over time, but quickly, within minutes or hours,” she said.

No one expects the world’s building stock to suddenly upgrade to the ideal air quality. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t move in that direction,” Dr. Taylor said. Changes can start small and gradually increase.

New research targets indoor air

Humidity is one of the key areas for current research, said Karl Rockne, PhD, director of the environmental engineering program at the National Science Foundation.

“When a virus comes out, it’s not just a naked virus, which is exceptionally small. It’s a virus encapsulated in liquid. And that’s why the humidity is so key. The degree of humidity can determine how fast the water evaporates from the particle,” he said in an interview.

In the wake of COVID-19, his institution is funding more cross-disciplinary research in biology, building science, architecture, and physics, he pointed out.

One such effort involved the development of a sensor that can capture live COVID-19 virus. This so-called “smoking gun,” which proved that the virus can spread through the air, took the combined expertise of professionals in medicine, engineering, and several other disciplines.

Currently, investigators are examining indoor air quality and water supplies in offices that have been left empty during the pandemic, and the effect they will have on human health. And others are looking at the way outside air quality affects indoor air quality, particularly where outdoor air quality is poor, such as in areas experiencing wildfires.

So will COVID-19 be the catalyst that finally drives changes to building design, regulation, and public expectations of air quality in the spaces where we spend close to 90% of our time?

“If not COVID, what else? It affected every country, every sector,” Dr. Morawska said. “There’s enough momentum now to do something about this. And enough realization there is a problem.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intervention reduces PPI use without worsening acid-related diseases

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use can safely be reduced by deprescribing efforts coupled with patient and clinician education, according to a retrospective study involving more than 4 million veterans.

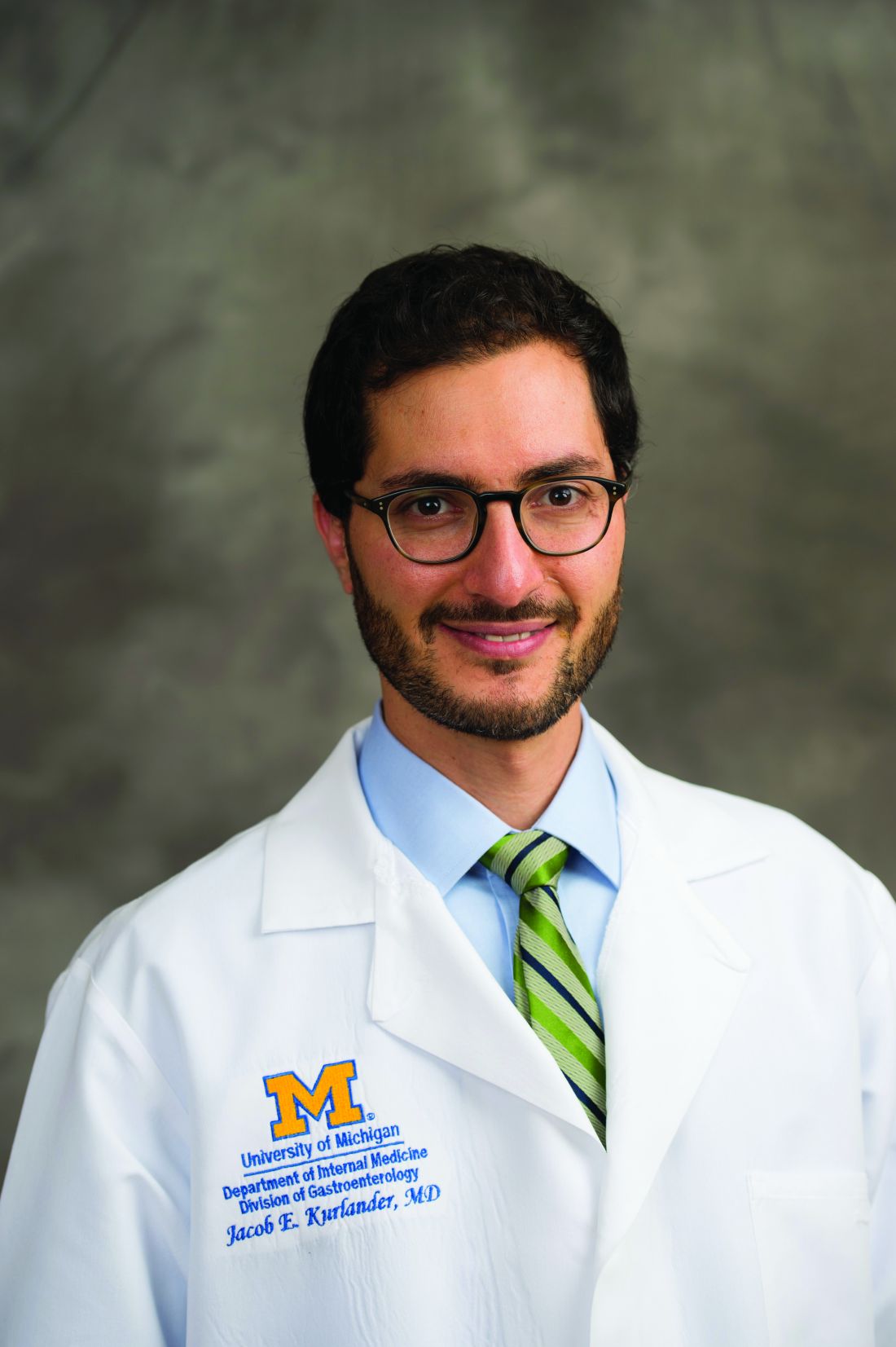

After 1 year, the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in PPI use without worsening of acid-related diseases, reported lead author Jacob E. Kurlander, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System’s Center for Clinical Management Research.

“There’s increasing interest in interventions to reduce PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander said during his virtual presentation at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). “Many of the interventions have come in the form of patient and provider education, like the Choosing Wisely campaign put out by the American Board of Internal Medicine. However, in rigorous studies, few interventions have actually proven effective, and many of these studies lack data on clinical outcomes, so it’s difficult to ascertain the real clinical benefits, or even harms.”

In an effort to address this gap, the investigators conducted a retrospective, difference-in-difference study spanning 10 years, from 2009 to 2019. The 1-year intervention, implemented in August 2013, included refill restrictions for PPIs without documented indication for long-term use, voiding of PPI prescriptions not filled within 6 months, a quick-order option for H2-receptor antagonists, reports to identify high-dose PPI prescribing, and patient and clinician education.

The intervention group consisted of 192,607-250,349 veterans in Veteran Integrated Service Network 17, whereas the control group consisted of 3,775,978-4,360,908 veterans in other service networks (ranges in population size are due to variations across 6-month intervals of analysis). For each 6-month interval, patients were included if they had at least two primary care visits within the past 2 years, and excluded if they received primary care at three other sites that joined the intervention site after initial implementation.

The investigators analyzed three main outcomes: Proportion of veterans dispensed a PPI prescription from the VA at any dose; incidence proportion of hospitalization for upper GI diseases, including upper GI bleeding other than from esophageal varices or angiodysplasia, as well as nonbleeding acid peptic disease; and rates of primary care visits, gastroenterology visits, and esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs).

The analysis was divided into a preimplementation period, lasting approximately 5 years, and a postimplementation period with a similar duration. In the postimplementation period, the intervention group had a 5.9% relative reduction in PPI prescriptions, compared with the control group (P < .001). During the same period, the intervention site did not have a significant increase in the rate of patients hospitalized for upper GI diseases, primary care visits, GI clinic visits, or EGDs.

In a subgroup analysis of patients coprescribed PPIs during time at high-risk for upper GI bleeding (that is, when they possessed at least two high-risk medications, such as warfarin), there was a 4.6% relative reduction in time with PPI gastroprotection among the intervention group, compared with the control group (P = .003). In a second sensitivity analysis, hospitalization for upper GI diseases in high-risk patients at least 65 years of age was not significantly different between groups.

“[This] multicomponent PPI deprescribing program led to sustained reductions in PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander concluded. “However, this blunt intervention also reduced appropriate use of PPIs for gastroprotection, raising some concerns about clinical quality of care, but this did not appear to cause any measurable clinical harm in terms of hospitalizations for upper GI diseases.”

Debate around ‘unnecessary PPI use’

According to Philip O. Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of motility laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, the study “makes an attempt to do what others have tried in different ways, which is to develop a mechanism to help reduce or discontinue proton pump inhibitors when people believe they’re not indicated.”

Yet this latter element – appropriate indication – drives an ongoing debate.

“This is a very controversial area,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “The concept of using the lowest effective dose of medication needed for a symptom or a disease is not new, but the push to reducing or eliminating ‘unnecessary PPI use’ is one that I believe should be carefully discussed, and that we have a clear understanding of what constitutes unnecessary use. And quite honestly, I’m willing to state that I don’t believe that’s been well defined.”

Dr. Katz, who recently coauthored an article about PPIs, suggested that more prospective research is needed to identify which patients need PPIs and which don’t.

“What we really need are more studies that look at who really needs [PPIs] long term,” Dr. Katz said, “as opposed to doing it ad hoc.”

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Katz is a consultant for Phathom Pharma.

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use can safely be reduced by deprescribing efforts coupled with patient and clinician education, according to a retrospective study involving more than 4 million veterans.

After 1 year, the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in PPI use without worsening of acid-related diseases, reported lead author Jacob E. Kurlander, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System’s Center for Clinical Management Research.

“There’s increasing interest in interventions to reduce PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander said during his virtual presentation at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). “Many of the interventions have come in the form of patient and provider education, like the Choosing Wisely campaign put out by the American Board of Internal Medicine. However, in rigorous studies, few interventions have actually proven effective, and many of these studies lack data on clinical outcomes, so it’s difficult to ascertain the real clinical benefits, or even harms.”

In an effort to address this gap, the investigators conducted a retrospective, difference-in-difference study spanning 10 years, from 2009 to 2019. The 1-year intervention, implemented in August 2013, included refill restrictions for PPIs without documented indication for long-term use, voiding of PPI prescriptions not filled within 6 months, a quick-order option for H2-receptor antagonists, reports to identify high-dose PPI prescribing, and patient and clinician education.

The intervention group consisted of 192,607-250,349 veterans in Veteran Integrated Service Network 17, whereas the control group consisted of 3,775,978-4,360,908 veterans in other service networks (ranges in population size are due to variations across 6-month intervals of analysis). For each 6-month interval, patients were included if they had at least two primary care visits within the past 2 years, and excluded if they received primary care at three other sites that joined the intervention site after initial implementation.

The investigators analyzed three main outcomes: Proportion of veterans dispensed a PPI prescription from the VA at any dose; incidence proportion of hospitalization for upper GI diseases, including upper GI bleeding other than from esophageal varices or angiodysplasia, as well as nonbleeding acid peptic disease; and rates of primary care visits, gastroenterology visits, and esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs).

The analysis was divided into a preimplementation period, lasting approximately 5 years, and a postimplementation period with a similar duration. In the postimplementation period, the intervention group had a 5.9% relative reduction in PPI prescriptions, compared with the control group (P < .001). During the same period, the intervention site did not have a significant increase in the rate of patients hospitalized for upper GI diseases, primary care visits, GI clinic visits, or EGDs.

In a subgroup analysis of patients coprescribed PPIs during time at high-risk for upper GI bleeding (that is, when they possessed at least two high-risk medications, such as warfarin), there was a 4.6% relative reduction in time with PPI gastroprotection among the intervention group, compared with the control group (P = .003). In a second sensitivity analysis, hospitalization for upper GI diseases in high-risk patients at least 65 years of age was not significantly different between groups.

“[This] multicomponent PPI deprescribing program led to sustained reductions in PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander concluded. “However, this blunt intervention also reduced appropriate use of PPIs for gastroprotection, raising some concerns about clinical quality of care, but this did not appear to cause any measurable clinical harm in terms of hospitalizations for upper GI diseases.”

Debate around ‘unnecessary PPI use’

According to Philip O. Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of motility laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, the study “makes an attempt to do what others have tried in different ways, which is to develop a mechanism to help reduce or discontinue proton pump inhibitors when people believe they’re not indicated.”

Yet this latter element – appropriate indication – drives an ongoing debate.

“This is a very controversial area,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “The concept of using the lowest effective dose of medication needed for a symptom or a disease is not new, but the push to reducing or eliminating ‘unnecessary PPI use’ is one that I believe should be carefully discussed, and that we have a clear understanding of what constitutes unnecessary use. And quite honestly, I’m willing to state that I don’t believe that’s been well defined.”

Dr. Katz, who recently coauthored an article about PPIs, suggested that more prospective research is needed to identify which patients need PPIs and which don’t.

“What we really need are more studies that look at who really needs [PPIs] long term,” Dr. Katz said, “as opposed to doing it ad hoc.”

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Katz is a consultant for Phathom Pharma.

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use can safely be reduced by deprescribing efforts coupled with patient and clinician education, according to a retrospective study involving more than 4 million veterans.

After 1 year, the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in PPI use without worsening of acid-related diseases, reported lead author Jacob E. Kurlander, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System’s Center for Clinical Management Research.

“There’s increasing interest in interventions to reduce PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander said during his virtual presentation at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). “Many of the interventions have come in the form of patient and provider education, like the Choosing Wisely campaign put out by the American Board of Internal Medicine. However, in rigorous studies, few interventions have actually proven effective, and many of these studies lack data on clinical outcomes, so it’s difficult to ascertain the real clinical benefits, or even harms.”

In an effort to address this gap, the investigators conducted a retrospective, difference-in-difference study spanning 10 years, from 2009 to 2019. The 1-year intervention, implemented in August 2013, included refill restrictions for PPIs without documented indication for long-term use, voiding of PPI prescriptions not filled within 6 months, a quick-order option for H2-receptor antagonists, reports to identify high-dose PPI prescribing, and patient and clinician education.

The intervention group consisted of 192,607-250,349 veterans in Veteran Integrated Service Network 17, whereas the control group consisted of 3,775,978-4,360,908 veterans in other service networks (ranges in population size are due to variations across 6-month intervals of analysis). For each 6-month interval, patients were included if they had at least two primary care visits within the past 2 years, and excluded if they received primary care at three other sites that joined the intervention site after initial implementation.

The investigators analyzed three main outcomes: Proportion of veterans dispensed a PPI prescription from the VA at any dose; incidence proportion of hospitalization for upper GI diseases, including upper GI bleeding other than from esophageal varices or angiodysplasia, as well as nonbleeding acid peptic disease; and rates of primary care visits, gastroenterology visits, and esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs).

The analysis was divided into a preimplementation period, lasting approximately 5 years, and a postimplementation period with a similar duration. In the postimplementation period, the intervention group had a 5.9% relative reduction in PPI prescriptions, compared with the control group (P < .001). During the same period, the intervention site did not have a significant increase in the rate of patients hospitalized for upper GI diseases, primary care visits, GI clinic visits, or EGDs.

In a subgroup analysis of patients coprescribed PPIs during time at high-risk for upper GI bleeding (that is, when they possessed at least two high-risk medications, such as warfarin), there was a 4.6% relative reduction in time with PPI gastroprotection among the intervention group, compared with the control group (P = .003). In a second sensitivity analysis, hospitalization for upper GI diseases in high-risk patients at least 65 years of age was not significantly different between groups.

“[This] multicomponent PPI deprescribing program led to sustained reductions in PPI use,” Dr. Kurlander concluded. “However, this blunt intervention also reduced appropriate use of PPIs for gastroprotection, raising some concerns about clinical quality of care, but this did not appear to cause any measurable clinical harm in terms of hospitalizations for upper GI diseases.”

Debate around ‘unnecessary PPI use’

According to Philip O. Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of motility laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, the study “makes an attempt to do what others have tried in different ways, which is to develop a mechanism to help reduce or discontinue proton pump inhibitors when people believe they’re not indicated.”

Yet this latter element – appropriate indication – drives an ongoing debate.

“This is a very controversial area,” Dr. Katz said in an interview. “The concept of using the lowest effective dose of medication needed for a symptom or a disease is not new, but the push to reducing or eliminating ‘unnecessary PPI use’ is one that I believe should be carefully discussed, and that we have a clear understanding of what constitutes unnecessary use. And quite honestly, I’m willing to state that I don’t believe that’s been well defined.”

Dr. Katz, who recently coauthored an article about PPIs, suggested that more prospective research is needed to identify which patients need PPIs and which don’t.

“What we really need are more studies that look at who really needs [PPIs] long term,” Dr. Katz said, “as opposed to doing it ad hoc.”

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Katz is a consultant for Phathom Pharma.

FROM DDW 2021

More and more doctors abandoning private practice

according to a new report.

These patterns likely reflect broader trends toward consolidation in health care, with both insurance companies and hospitals also having grown in size in recent years.

The latest biennial analysis of doctors’ practices by the American Medical Association showed an acceleration of a trend away from private practice, defined as a practice wholly owned by physicians. The 2020 results found less than half – 49.1 % – of doctors involved in patient care worked in a private practice, the AMA said in a report released in May 2021.

This marked the first time private practice was not the dominant approach since the AMA analysis began in 2012. What’s more, the trend appears to be gaining steam, with a drop of almost 5 percentage points from 54.0% in private practice in 2018. The percent of doctors in private practice declined at a slower rate in previous AMA surveys, slipping to 55.8% in 2016 from 56.8% in 2018 and 60.1% in 2012.

Employment and ownership structures have become so varied that no single approach or size of organization “can or should be considered the typical physician practice,” the report noted.

The AMA, for example, added to its 2020 benchmark survey an option to identify private equity organizations as employers. The survey found 4% of doctors involved in patient care worked in practices owned by these kinds of firms. Other options include practices wholly or jointly owned by hospital and health systems and insurers, as well as direct employment and contracting.

There are signs that the shift away from smaller private practices will continue, with younger doctors appearing more likely to seek employment.

The survey found 42% of doctors ages 55 and older were employed by someone else, compared with 51.2% of doctors ages 40-54 and 70% of physicians under the age of 40.

The AMA surveyed 3,500 U.S. doctors through the 2020 Physician Practice Benchmark Survey. The survey was conducted from September to October 2020, roughly 6 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore may not reflect its full impact.

“Physician practices were hit hard by the economic impact of the early pandemic as patient volume and revenues shrank while medical supply expenses spiked. The impact of these economic forces on physician practice arrangements is ongoing and may not be fully realized for some time,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

In a survey released in 2020 by McKinsey & Company, 53% of independent doctors reported that they were worried about their practices surviving the stresses of the pandemic, this news organization reported.

Challenging environment

It’s not just money leading to the shift away from private practice, according to a 2020 report from the American Hospital Association, titled “Evolving Physician-Practice Ownership Models.”

Many recent graduates of medical schools have significant debt and are more likely to opt for employment, which offers more financial stability and work-life balance, the report said.

Doctors also need to keep up with expectations of their patients that have been shaped by advances in other sectors, like banking, the AHA noted. People are used to working on their own schedules, and want to make appointments through apps, get test results rapidly and on their mobile devices, and communicate with their providers virtually.

“It is challenging to meet these expectations and make the necessary technology investments as a solo or small group practice,” the AHA report said.

Hospitals face competition for doctors from insurers, which have been looking in some cases to directly employ more physicians, the AHA also noted. The report cites insurance giant UnitedHealth Group’s Optum unit as the most visible example of this trend.

On a January call about corporate earnings, David Wichmann, then chief executive of UnitedHealth, spoke about the firm’s “aim to reinvent health care delivery,” including efforts to have its own primary and multispecialty care practices.

“OptumCare entered 2021 with over 50,000 physicians and 1,400 clinics,” Mr. Wichmann said. “Over the course of this year, we expect to grow our employed and affiliated physicians by at least 10,000. This work of building local physician-led systems of care continues to be central to our mission. “

UnitedHealth’s new CEO is Andrew Witty, who had led the Optum unit.

Attractions of larger groups

Older doctors – those 55 years and up – were significantly more likely to work in small practices than those younger than 40, the 2020 survey found. Results showed 40.9% of doctors under 40 worked in practices of 10 or fewer colleagues, compared with 61.4% of those age 55 and older.

The large difference between age groups suggests that attrition is one reason for the shift in practice size. Retiring doctors who leave small practices are not being replaced on a one-for-one basis by younger doctors, AMA said. The same reason also appears to be a factor in the shift in practice ownership to larger systems.

Doctors in larger group practices can count on a stable business model, with a better ability to survive disruptive market trends, including those of a more extreme nature, like COVID-19, said Fred Horton, president of AMGA Consulting.

AMGA Consulting is a wholly-owned subsidiary of AMGA, formerly called American Medical Group Association. Its more than 400 members include well-known multispecialty groups and health care systems such as the Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger, the Permanente Medical Group, and Intermountain Healthcare as well as many smaller physician practices.

Mr. Horton, who holds a master’s degree in health administration, said some doctors may want to participate in alternative payment programs offered by insurers, who are seeking to shift away from the fee-for-service model

“Larger organizations can dedicate more resources to continuous quality improvement,” Mr. Horton said. “This is especially important for physicians who are taking on risk-based contracts, as quality can directly impact how much they earn.”

For one oncologist, it was turning to alternative payment methods that helped him keep his private practice afloat.

Kashyap Patel, MD, chief executive of the Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates in Rock Hill, S.C., said he maintained the independence of his practice amid pressure from a large health system, which had been buying medical groups in the area. That began to interfere with referrals of patients from other doctors, which are key for cancer specialists, said Dr. Patel, who also is president of the Community Oncology Alliance.

In response, Dr. Patel worked with Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina on an arrangement where his practice sought certifications from the National Committee for Quality Assurance to get better rates.

The effort has allowed Dr. Patel’s clinic to focus more on preventing hospitalizations and visits to the emergency room he said.

In Dr. Patel’s view, his patients benefit from his efforts to remain in independent practice. A switch to ownership by a large health care organization would have put them at risk for higher medical bills, jeopardizing their access to treatment, he said. The reason? Hospitals can charge more for services provided by doctors they employ.

“Nothing would change. I would be the same. The building would be the same, but the cost would go up,” Dr. Patel said.

For its part, the AHA has repeatedly challenged arguments that acquisitions and mergers result in higher costs for patients.

Instead, the AHA has raised alarms about consolidation of health insurers, a concern it shares with AMA. In a 2020 report examining competition among insurers, AMA noted doctors working in small practices can be put at a disadvantage if mergers and acquisitions leave an insurer with too much market power.

“Under antitrust law, independent physicians cannot negotiate collectively with health

Insurers,” the AMA said in the report. “This imbalance in relative size leaves most physicians with a weak bargaining position relative to commercial payers.”

AMA’s research on the effects of insurers’ wielding significant market clout has been used in effort to thwart mergers in this industry.

‘Dramatic restructuring’

The Federal Trade Commission also has taken note of the trends discussed in the new AMA report, saying that “U.S. physician markets are undergoing a dramatic restructuring.”

The FTC in January announced a study of the impact of the consolidation of doctors groups and health care facilities. FTC is seeking data for inpatient, outpatient, and doctors services in 15 states from 2015 through 2020. To gather this data, the commission has issued orders to six major insurers – Aetna, Anthem, Florida Blue, Cigna, Health Care Service Corporation and United Healthcare.

The FTC is concerned that acquired practices may have to alter their referral patterns to favor their affiliated hospital system over competing hospital systems. But FTC staff also said it might be that these acquisitions result in efficiencies, such as enhanced coordination of care between doctors and hospitals “that outweigh potential competitive harms.”

The research project will likely take several years to complete because of its scope, the FTC said. For that reason, the FTC said its Bureau of Economics will release a series of research papers examining different aspects of this inquiry rather than a single paper containing all of the analyses.

Private equity ‘roll-ups’

On the day the FTC announced the study of the impact of doctors groups, one of the panel’s commissioners argued for a closer look at how private equity firms make their purchases.

In a Jan. 15 tweet, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra said his agency needs to challenge their “roll-ups of small physician practices” as well as clinics and labs. This is a practice of using a series of acquisitions too small to trigger the federal threshold for a serious look from the FTC and Department of Justice. (The threshold for 2021 stands around the $92 million mark. This benchmark is known as Hart-Scott-Rodino notification after a 1976 law that set a reporting standard.)

Mr. Chopra attached to his Jan. 15 tweet a 2020 statement in which he called for stepped-up scrutiny of private-equity firms’ acquisitions of doctors’ practices. Mr. Chopra noted that private-equity firms have been buying practices focused on anesthesiology and emergency medicine, fields which triggered consumer complaints about surprise billing for emergency care.

“Given trends in today’s markets, it is critical that the FTC find new ways to ensure the agency has a rigorous, data-driven approach to market monitoring and enforcement,” Mr. Chopra wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new report.

These patterns likely reflect broader trends toward consolidation in health care, with both insurance companies and hospitals also having grown in size in recent years.

The latest biennial analysis of doctors’ practices by the American Medical Association showed an acceleration of a trend away from private practice, defined as a practice wholly owned by physicians. The 2020 results found less than half – 49.1 % – of doctors involved in patient care worked in a private practice, the AMA said in a report released in May 2021.

This marked the first time private practice was not the dominant approach since the AMA analysis began in 2012. What’s more, the trend appears to be gaining steam, with a drop of almost 5 percentage points from 54.0% in private practice in 2018. The percent of doctors in private practice declined at a slower rate in previous AMA surveys, slipping to 55.8% in 2016 from 56.8% in 2018 and 60.1% in 2012.

Employment and ownership structures have become so varied that no single approach or size of organization “can or should be considered the typical physician practice,” the report noted.

The AMA, for example, added to its 2020 benchmark survey an option to identify private equity organizations as employers. The survey found 4% of doctors involved in patient care worked in practices owned by these kinds of firms. Other options include practices wholly or jointly owned by hospital and health systems and insurers, as well as direct employment and contracting.

There are signs that the shift away from smaller private practices will continue, with younger doctors appearing more likely to seek employment.

The survey found 42% of doctors ages 55 and older were employed by someone else, compared with 51.2% of doctors ages 40-54 and 70% of physicians under the age of 40.

The AMA surveyed 3,500 U.S. doctors through the 2020 Physician Practice Benchmark Survey. The survey was conducted from September to October 2020, roughly 6 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore may not reflect its full impact.

“Physician practices were hit hard by the economic impact of the early pandemic as patient volume and revenues shrank while medical supply expenses spiked. The impact of these economic forces on physician practice arrangements is ongoing and may not be fully realized for some time,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

In a survey released in 2020 by McKinsey & Company, 53% of independent doctors reported that they were worried about their practices surviving the stresses of the pandemic, this news organization reported.

Challenging environment

It’s not just money leading to the shift away from private practice, according to a 2020 report from the American Hospital Association, titled “Evolving Physician-Practice Ownership Models.”

Many recent graduates of medical schools have significant debt and are more likely to opt for employment, which offers more financial stability and work-life balance, the report said.

Doctors also need to keep up with expectations of their patients that have been shaped by advances in other sectors, like banking, the AHA noted. People are used to working on their own schedules, and want to make appointments through apps, get test results rapidly and on their mobile devices, and communicate with their providers virtually.

“It is challenging to meet these expectations and make the necessary technology investments as a solo or small group practice,” the AHA report said.

Hospitals face competition for doctors from insurers, which have been looking in some cases to directly employ more physicians, the AHA also noted. The report cites insurance giant UnitedHealth Group’s Optum unit as the most visible example of this trend.

On a January call about corporate earnings, David Wichmann, then chief executive of UnitedHealth, spoke about the firm’s “aim to reinvent health care delivery,” including efforts to have its own primary and multispecialty care practices.

“OptumCare entered 2021 with over 50,000 physicians and 1,400 clinics,” Mr. Wichmann said. “Over the course of this year, we expect to grow our employed and affiliated physicians by at least 10,000. This work of building local physician-led systems of care continues to be central to our mission. “

UnitedHealth’s new CEO is Andrew Witty, who had led the Optum unit.

Attractions of larger groups

Older doctors – those 55 years and up – were significantly more likely to work in small practices than those younger than 40, the 2020 survey found. Results showed 40.9% of doctors under 40 worked in practices of 10 or fewer colleagues, compared with 61.4% of those age 55 and older.

The large difference between age groups suggests that attrition is one reason for the shift in practice size. Retiring doctors who leave small practices are not being replaced on a one-for-one basis by younger doctors, AMA said. The same reason also appears to be a factor in the shift in practice ownership to larger systems.

Doctors in larger group practices can count on a stable business model, with a better ability to survive disruptive market trends, including those of a more extreme nature, like COVID-19, said Fred Horton, president of AMGA Consulting.

AMGA Consulting is a wholly-owned subsidiary of AMGA, formerly called American Medical Group Association. Its more than 400 members include well-known multispecialty groups and health care systems such as the Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger, the Permanente Medical Group, and Intermountain Healthcare as well as many smaller physician practices.

Mr. Horton, who holds a master’s degree in health administration, said some doctors may want to participate in alternative payment programs offered by insurers, who are seeking to shift away from the fee-for-service model

“Larger organizations can dedicate more resources to continuous quality improvement,” Mr. Horton said. “This is especially important for physicians who are taking on risk-based contracts, as quality can directly impact how much they earn.”

For one oncologist, it was turning to alternative payment methods that helped him keep his private practice afloat.

Kashyap Patel, MD, chief executive of the Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates in Rock Hill, S.C., said he maintained the independence of his practice amid pressure from a large health system, which had been buying medical groups in the area. That began to interfere with referrals of patients from other doctors, which are key for cancer specialists, said Dr. Patel, who also is president of the Community Oncology Alliance.

In response, Dr. Patel worked with Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina on an arrangement where his practice sought certifications from the National Committee for Quality Assurance to get better rates.

The effort has allowed Dr. Patel’s clinic to focus more on preventing hospitalizations and visits to the emergency room he said.

In Dr. Patel’s view, his patients benefit from his efforts to remain in independent practice. A switch to ownership by a large health care organization would have put them at risk for higher medical bills, jeopardizing their access to treatment, he said. The reason? Hospitals can charge more for services provided by doctors they employ.

“Nothing would change. I would be the same. The building would be the same, but the cost would go up,” Dr. Patel said.

For its part, the AHA has repeatedly challenged arguments that acquisitions and mergers result in higher costs for patients.

Instead, the AHA has raised alarms about consolidation of health insurers, a concern it shares with AMA. In a 2020 report examining competition among insurers, AMA noted doctors working in small practices can be put at a disadvantage if mergers and acquisitions leave an insurer with too much market power.

“Under antitrust law, independent physicians cannot negotiate collectively with health

Insurers,” the AMA said in the report. “This imbalance in relative size leaves most physicians with a weak bargaining position relative to commercial payers.”

AMA’s research on the effects of insurers’ wielding significant market clout has been used in effort to thwart mergers in this industry.

‘Dramatic restructuring’

The Federal Trade Commission also has taken note of the trends discussed in the new AMA report, saying that “U.S. physician markets are undergoing a dramatic restructuring.”

The FTC in January announced a study of the impact of the consolidation of doctors groups and health care facilities. FTC is seeking data for inpatient, outpatient, and doctors services in 15 states from 2015 through 2020. To gather this data, the commission has issued orders to six major insurers – Aetna, Anthem, Florida Blue, Cigna, Health Care Service Corporation and United Healthcare.

The FTC is concerned that acquired practices may have to alter their referral patterns to favor their affiliated hospital system over competing hospital systems. But FTC staff also said it might be that these acquisitions result in efficiencies, such as enhanced coordination of care between doctors and hospitals “that outweigh potential competitive harms.”

The research project will likely take several years to complete because of its scope, the FTC said. For that reason, the FTC said its Bureau of Economics will release a series of research papers examining different aspects of this inquiry rather than a single paper containing all of the analyses.

Private equity ‘roll-ups’

On the day the FTC announced the study of the impact of doctors groups, one of the panel’s commissioners argued for a closer look at how private equity firms make their purchases.

In a Jan. 15 tweet, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra said his agency needs to challenge their “roll-ups of small physician practices” as well as clinics and labs. This is a practice of using a series of acquisitions too small to trigger the federal threshold for a serious look from the FTC and Department of Justice. (The threshold for 2021 stands around the $92 million mark. This benchmark is known as Hart-Scott-Rodino notification after a 1976 law that set a reporting standard.)

Mr. Chopra attached to his Jan. 15 tweet a 2020 statement in which he called for stepped-up scrutiny of private-equity firms’ acquisitions of doctors’ practices. Mr. Chopra noted that private-equity firms have been buying practices focused on anesthesiology and emergency medicine, fields which triggered consumer complaints about surprise billing for emergency care.

“Given trends in today’s markets, it is critical that the FTC find new ways to ensure the agency has a rigorous, data-driven approach to market monitoring and enforcement,” Mr. Chopra wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new report.

These patterns likely reflect broader trends toward consolidation in health care, with both insurance companies and hospitals also having grown in size in recent years.

The latest biennial analysis of doctors’ practices by the American Medical Association showed an acceleration of a trend away from private practice, defined as a practice wholly owned by physicians. The 2020 results found less than half – 49.1 % – of doctors involved in patient care worked in a private practice, the AMA said in a report released in May 2021.

This marked the first time private practice was not the dominant approach since the AMA analysis began in 2012. What’s more, the trend appears to be gaining steam, with a drop of almost 5 percentage points from 54.0% in private practice in 2018. The percent of doctors in private practice declined at a slower rate in previous AMA surveys, slipping to 55.8% in 2016 from 56.8% in 2018 and 60.1% in 2012.

Employment and ownership structures have become so varied that no single approach or size of organization “can or should be considered the typical physician practice,” the report noted.

The AMA, for example, added to its 2020 benchmark survey an option to identify private equity organizations as employers. The survey found 4% of doctors involved in patient care worked in practices owned by these kinds of firms. Other options include practices wholly or jointly owned by hospital and health systems and insurers, as well as direct employment and contracting.

There are signs that the shift away from smaller private practices will continue, with younger doctors appearing more likely to seek employment.

The survey found 42% of doctors ages 55 and older were employed by someone else, compared with 51.2% of doctors ages 40-54 and 70% of physicians under the age of 40.

The AMA surveyed 3,500 U.S. doctors through the 2020 Physician Practice Benchmark Survey. The survey was conducted from September to October 2020, roughly 6 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore may not reflect its full impact.

“Physician practices were hit hard by the economic impact of the early pandemic as patient volume and revenues shrank while medical supply expenses spiked. The impact of these economic forces on physician practice arrangements is ongoing and may not be fully realized for some time,” AMA President Susan R. Bailey, MD, said in a statement.

In a survey released in 2020 by McKinsey & Company, 53% of independent doctors reported that they were worried about their practices surviving the stresses of the pandemic, this news organization reported.

Challenging environment

It’s not just money leading to the shift away from private practice, according to a 2020 report from the American Hospital Association, titled “Evolving Physician-Practice Ownership Models.”

Many recent graduates of medical schools have significant debt and are more likely to opt for employment, which offers more financial stability and work-life balance, the report said.

Doctors also need to keep up with expectations of their patients that have been shaped by advances in other sectors, like banking, the AHA noted. People are used to working on their own schedules, and want to make appointments through apps, get test results rapidly and on their mobile devices, and communicate with their providers virtually.

“It is challenging to meet these expectations and make the necessary technology investments as a solo or small group practice,” the AHA report said.

Hospitals face competition for doctors from insurers, which have been looking in some cases to directly employ more physicians, the AHA also noted. The report cites insurance giant UnitedHealth Group’s Optum unit as the most visible example of this trend.

On a January call about corporate earnings, David Wichmann, then chief executive of UnitedHealth, spoke about the firm’s “aim to reinvent health care delivery,” including efforts to have its own primary and multispecialty care practices.

“OptumCare entered 2021 with over 50,000 physicians and 1,400 clinics,” Mr. Wichmann said. “Over the course of this year, we expect to grow our employed and affiliated physicians by at least 10,000. This work of building local physician-led systems of care continues to be central to our mission. “

UnitedHealth’s new CEO is Andrew Witty, who had led the Optum unit.

Attractions of larger groups

Older doctors – those 55 years and up – were significantly more likely to work in small practices than those younger than 40, the 2020 survey found. Results showed 40.9% of doctors under 40 worked in practices of 10 or fewer colleagues, compared with 61.4% of those age 55 and older.

The large difference between age groups suggests that attrition is one reason for the shift in practice size. Retiring doctors who leave small practices are not being replaced on a one-for-one basis by younger doctors, AMA said. The same reason also appears to be a factor in the shift in practice ownership to larger systems.

Doctors in larger group practices can count on a stable business model, with a better ability to survive disruptive market trends, including those of a more extreme nature, like COVID-19, said Fred Horton, president of AMGA Consulting.

AMGA Consulting is a wholly-owned subsidiary of AMGA, formerly called American Medical Group Association. Its more than 400 members include well-known multispecialty groups and health care systems such as the Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger, the Permanente Medical Group, and Intermountain Healthcare as well as many smaller physician practices.

Mr. Horton, who holds a master’s degree in health administration, said some doctors may want to participate in alternative payment programs offered by insurers, who are seeking to shift away from the fee-for-service model

“Larger organizations can dedicate more resources to continuous quality improvement,” Mr. Horton said. “This is especially important for physicians who are taking on risk-based contracts, as quality can directly impact how much they earn.”

For one oncologist, it was turning to alternative payment methods that helped him keep his private practice afloat.

Kashyap Patel, MD, chief executive of the Carolina Blood and Cancer Care Associates in Rock Hill, S.C., said he maintained the independence of his practice amid pressure from a large health system, which had been buying medical groups in the area. That began to interfere with referrals of patients from other doctors, which are key for cancer specialists, said Dr. Patel, who also is president of the Community Oncology Alliance.

In response, Dr. Patel worked with Blue Cross Blue Shield of South Carolina on an arrangement where his practice sought certifications from the National Committee for Quality Assurance to get better rates.

The effort has allowed Dr. Patel’s clinic to focus more on preventing hospitalizations and visits to the emergency room he said.

In Dr. Patel’s view, his patients benefit from his efforts to remain in independent practice. A switch to ownership by a large health care organization would have put them at risk for higher medical bills, jeopardizing their access to treatment, he said. The reason? Hospitals can charge more for services provided by doctors they employ.

“Nothing would change. I would be the same. The building would be the same, but the cost would go up,” Dr. Patel said.

For its part, the AHA has repeatedly challenged arguments that acquisitions and mergers result in higher costs for patients.

Instead, the AHA has raised alarms about consolidation of health insurers, a concern it shares with AMA. In a 2020 report examining competition among insurers, AMA noted doctors working in small practices can be put at a disadvantage if mergers and acquisitions leave an insurer with too much market power.

“Under antitrust law, independent physicians cannot negotiate collectively with health

Insurers,” the AMA said in the report. “This imbalance in relative size leaves most physicians with a weak bargaining position relative to commercial payers.”

AMA’s research on the effects of insurers’ wielding significant market clout has been used in effort to thwart mergers in this industry.

‘Dramatic restructuring’

The Federal Trade Commission also has taken note of the trends discussed in the new AMA report, saying that “U.S. physician markets are undergoing a dramatic restructuring.”

The FTC in January announced a study of the impact of the consolidation of doctors groups and health care facilities. FTC is seeking data for inpatient, outpatient, and doctors services in 15 states from 2015 through 2020. To gather this data, the commission has issued orders to six major insurers – Aetna, Anthem, Florida Blue, Cigna, Health Care Service Corporation and United Healthcare.

The FTC is concerned that acquired practices may have to alter their referral patterns to favor their affiliated hospital system over competing hospital systems. But FTC staff also said it might be that these acquisitions result in efficiencies, such as enhanced coordination of care between doctors and hospitals “that outweigh potential competitive harms.”

The research project will likely take several years to complete because of its scope, the FTC said. For that reason, the FTC said its Bureau of Economics will release a series of research papers examining different aspects of this inquiry rather than a single paper containing all of the analyses.

Private equity ‘roll-ups’

On the day the FTC announced the study of the impact of doctors groups, one of the panel’s commissioners argued for a closer look at how private equity firms make their purchases.

In a Jan. 15 tweet, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra said his agency needs to challenge their “roll-ups of small physician practices” as well as clinics and labs. This is a practice of using a series of acquisitions too small to trigger the federal threshold for a serious look from the FTC and Department of Justice. (The threshold for 2021 stands around the $92 million mark. This benchmark is known as Hart-Scott-Rodino notification after a 1976 law that set a reporting standard.)

Mr. Chopra attached to his Jan. 15 tweet a 2020 statement in which he called for stepped-up scrutiny of private-equity firms’ acquisitions of doctors’ practices. Mr. Chopra noted that private-equity firms have been buying practices focused on anesthesiology and emergency medicine, fields which triggered consumer complaints about surprise billing for emergency care.

“Given trends in today’s markets, it is critical that the FTC find new ways to ensure the agency has a rigorous, data-driven approach to market monitoring and enforcement,” Mr. Chopra wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Liver transplant outcomes improving for U.S. patients with HIV/HCV

While liver transplant outcomes were historically poor in people coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV), they have improved significantly in the era of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy, a recent analysis of U.S. organ transplant data showed.

The availability of highly potent DAA therapy should change how transplant specialists view patients coinfected with HIV/HCV who need a liver transplant, according to researcher Jennifer Wang, MD, chief gastroenterology fellow at the University of Chicago, who presented the results of the analysis at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). Cumulative graft survival rates since the introduction of DAAs are comparable between transplant recipients with HIV/HCV coinfection and recipients who are both HIV and HCV negative, according to the study.

“Having hepatitis C no longer confers worse patient survival in the DAA era, and this is the main takeaway from our study,” Dr. Wang said.

The study also showed that the number of liver transplants among HIV-infected patients has increased over the past 4-5 years. However, the absolute number remains low at 64 cases in 2019, or less than 1% of all liver transplants that year, and only about one-third of those HIV-positive recipients had HCV coinfection, according to Dr. Wang.

Moreover, relatively few centers are performing liver transplants for patients who are HIV/HCV coinfected, and there is significant geographic variation in where the procedures are done, she said in her presentation.

Reassuring data that should prompt referral

Taken together, these results should offer reassurance to transplant centers that patients coinfected with HIV/HCV are no longer at increased risk for poor outcomes after transplantation, said Christine M. Durand, MD, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“The additional call for action should be beyond the transplantation community to ensure that referrals for liver transplant are where they should be,” Dr. Durand said in an interview.

“With a number of only 64 transplants a year, we’re not doing enough, and there are more patients that could benefit from liver transplants,” added Dr. Durand, who is principal investigator of HOPE in Action, a prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and survival outcomes of HIV-positive deceased donor liver transplants in HIV-positive recipients.

Impact of the HOPE Act

Liver transplantation for HIV-positive patients has increased since the signing of the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act in 2013, according to Dr. Wang.

The HOPE act expanded the donor pool to include HIV-positive deceased donors, which not only increased the donor supply overall, but specifically helped HIV-positive individuals, who experience a higher rate of waiting-list mortality, according to a review on the topic authored by Dr. Durand and coauthors.

However, some transplant centers may be reluctant to do liver transplants in HIV-positive patients coinfected with HCV. That’s because, in previous studies that were conducted before the DAA era, outcomes after liver transplant in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients were inferior to those in patients with HIV but no HCV infection, Dr. Wang said.