User login

Internists Feel Underpaid, But Job Satisfaction Persists

A majority of internal medicine physicians report feeling underpaid, but approximately half say that potential pay was not a factor in their decision to choose the specialty, based on data from Medscape’s annual Internist Compensation Report.

Data from the Mercer consulting firm cited in the Medscape report showed an increase of 3% in 2023 over 2022 earnings for physicians in the United States overall. However, on a list of 29 specialties included in the report, internal medicine ranked near the bottom for annual compensation.

The report, based on data from 7000 physicians across the United States, showed that 58% of internal medicine physicians think physicians in general are underpaid, while 33% said that “most physicians are paid about right,” and 8% said that physicians are overpaid. Similarly, when asked about their personal compensation, 55% said that internists are not fairly paid, given their work demands.

Despite concerns about pay, 65% of the internists surveyed said that they were not taking on extra work to boost their incomes. Although less than half (45%) reported being happy with their current pay, 49% said that pay was not a factor in their choice of internal medicine.

Among internists, 60% reported opportunities for bonuses, but the average primary care provider bonus in 2023 was $27,000, compared with an average of $51,000 for bonus pay among specialists.

Money was relatively low on the list as being the most rewarding part of the job for an internist, according to the report. While 34% of respondents cited being good at their jobs and finding answers and diagnoses as the most rewarding part of their jobs, only 9% said “making good money at a job I like” was the most rewarding. The most commonly cited most challenging part of the job was “having so many rules and regulations (22%).”

In addition, approximately two thirds of respondents said other medical businesses (such as telemedicine, retailer clinics, and nonphysician healthcare providers) had no impact on their income, nor did competing physician practices.

More than half (58%) of the respondents were women and the most common age group (based on 5-year increments) was 50-54 years (15%).

Regular Pay Assessment Increases Awareness

Assessing physician compensation annually or at regular intervals allows organizations and physicians to know their financial situation and compensation/benefits compared with other professionals, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, many individual practices and employed physicians saw a decline in their revenue due to decrease in routine patient visits to the clinician offices, and decrease in routine and preventative procedures,” he noted.

“The findings from the current report were not unexpected, as certain specialties are more lucrative than primary care,” Dr. Deep said. “Specialties such as orthopedics, plastic surgery, and cardiology have the potential not only to generate more income for those specialist physicians, but also for the healthcare organizations that employ them,” he said.

Job Satisfaction Remains Important

As a practicing internist, Dr. Deep agreed that many internal medicine physicians would state that the satisfaction that their job and caring for patients brings to them is more important than the financial aspect of their practice.

“I am asked on occasion if I had an opportunity to go back to medical school and make a choice, whether I would have picked a different specialty. My answer is no,” Dr. Deep said.

“I would have picked internal medicine because of the satisfaction that it brings me,” he said.

Dr. Deep shared some potential strategies for employers to recruit and retain internal medicine physicians. If employers could incentivize internal medicine and other primary care specialties with higher signing bonuses and try to make their annual bonuses comparable to surgical specialties, that would help ensure that internal medicine specialists feel they are being paid fairly for their work, he said. “Decreasing the bureaucratic burden and involving physicians in decision-making and determination of compensation would also help,” he said.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

A majority of internal medicine physicians report feeling underpaid, but approximately half say that potential pay was not a factor in their decision to choose the specialty, based on data from Medscape’s annual Internist Compensation Report.

Data from the Mercer consulting firm cited in the Medscape report showed an increase of 3% in 2023 over 2022 earnings for physicians in the United States overall. However, on a list of 29 specialties included in the report, internal medicine ranked near the bottom for annual compensation.

The report, based on data from 7000 physicians across the United States, showed that 58% of internal medicine physicians think physicians in general are underpaid, while 33% said that “most physicians are paid about right,” and 8% said that physicians are overpaid. Similarly, when asked about their personal compensation, 55% said that internists are not fairly paid, given their work demands.

Despite concerns about pay, 65% of the internists surveyed said that they were not taking on extra work to boost their incomes. Although less than half (45%) reported being happy with their current pay, 49% said that pay was not a factor in their choice of internal medicine.

Among internists, 60% reported opportunities for bonuses, but the average primary care provider bonus in 2023 was $27,000, compared with an average of $51,000 for bonus pay among specialists.

Money was relatively low on the list as being the most rewarding part of the job for an internist, according to the report. While 34% of respondents cited being good at their jobs and finding answers and diagnoses as the most rewarding part of their jobs, only 9% said “making good money at a job I like” was the most rewarding. The most commonly cited most challenging part of the job was “having so many rules and regulations (22%).”

In addition, approximately two thirds of respondents said other medical businesses (such as telemedicine, retailer clinics, and nonphysician healthcare providers) had no impact on their income, nor did competing physician practices.

More than half (58%) of the respondents were women and the most common age group (based on 5-year increments) was 50-54 years (15%).

Regular Pay Assessment Increases Awareness

Assessing physician compensation annually or at regular intervals allows organizations and physicians to know their financial situation and compensation/benefits compared with other professionals, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, many individual practices and employed physicians saw a decline in their revenue due to decrease in routine patient visits to the clinician offices, and decrease in routine and preventative procedures,” he noted.

“The findings from the current report were not unexpected, as certain specialties are more lucrative than primary care,” Dr. Deep said. “Specialties such as orthopedics, plastic surgery, and cardiology have the potential not only to generate more income for those specialist physicians, but also for the healthcare organizations that employ them,” he said.

Job Satisfaction Remains Important

As a practicing internist, Dr. Deep agreed that many internal medicine physicians would state that the satisfaction that their job and caring for patients brings to them is more important than the financial aspect of their practice.

“I am asked on occasion if I had an opportunity to go back to medical school and make a choice, whether I would have picked a different specialty. My answer is no,” Dr. Deep said.

“I would have picked internal medicine because of the satisfaction that it brings me,” he said.

Dr. Deep shared some potential strategies for employers to recruit and retain internal medicine physicians. If employers could incentivize internal medicine and other primary care specialties with higher signing bonuses and try to make their annual bonuses comparable to surgical specialties, that would help ensure that internal medicine specialists feel they are being paid fairly for their work, he said. “Decreasing the bureaucratic burden and involving physicians in decision-making and determination of compensation would also help,” he said.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

A majority of internal medicine physicians report feeling underpaid, but approximately half say that potential pay was not a factor in their decision to choose the specialty, based on data from Medscape’s annual Internist Compensation Report.

Data from the Mercer consulting firm cited in the Medscape report showed an increase of 3% in 2023 over 2022 earnings for physicians in the United States overall. However, on a list of 29 specialties included in the report, internal medicine ranked near the bottom for annual compensation.

The report, based on data from 7000 physicians across the United States, showed that 58% of internal medicine physicians think physicians in general are underpaid, while 33% said that “most physicians are paid about right,” and 8% said that physicians are overpaid. Similarly, when asked about their personal compensation, 55% said that internists are not fairly paid, given their work demands.

Despite concerns about pay, 65% of the internists surveyed said that they were not taking on extra work to boost their incomes. Although less than half (45%) reported being happy with their current pay, 49% said that pay was not a factor in their choice of internal medicine.

Among internists, 60% reported opportunities for bonuses, but the average primary care provider bonus in 2023 was $27,000, compared with an average of $51,000 for bonus pay among specialists.

Money was relatively low on the list as being the most rewarding part of the job for an internist, according to the report. While 34% of respondents cited being good at their jobs and finding answers and diagnoses as the most rewarding part of their jobs, only 9% said “making good money at a job I like” was the most rewarding. The most commonly cited most challenging part of the job was “having so many rules and regulations (22%).”

In addition, approximately two thirds of respondents said other medical businesses (such as telemedicine, retailer clinics, and nonphysician healthcare providers) had no impact on their income, nor did competing physician practices.

More than half (58%) of the respondents were women and the most common age group (based on 5-year increments) was 50-54 years (15%).

Regular Pay Assessment Increases Awareness

Assessing physician compensation annually or at regular intervals allows organizations and physicians to know their financial situation and compensation/benefits compared with other professionals, said Noel Deep, MD, an internal medicine physician in group practice in Antigo, Wisconsin, in an interview. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, many individual practices and employed physicians saw a decline in their revenue due to decrease in routine patient visits to the clinician offices, and decrease in routine and preventative procedures,” he noted.

“The findings from the current report were not unexpected, as certain specialties are more lucrative than primary care,” Dr. Deep said. “Specialties such as orthopedics, plastic surgery, and cardiology have the potential not only to generate more income for those specialist physicians, but also for the healthcare organizations that employ them,” he said.

Job Satisfaction Remains Important

As a practicing internist, Dr. Deep agreed that many internal medicine physicians would state that the satisfaction that their job and caring for patients brings to them is more important than the financial aspect of their practice.

“I am asked on occasion if I had an opportunity to go back to medical school and make a choice, whether I would have picked a different specialty. My answer is no,” Dr. Deep said.

“I would have picked internal medicine because of the satisfaction that it brings me,” he said.

Dr. Deep shared some potential strategies for employers to recruit and retain internal medicine physicians. If employers could incentivize internal medicine and other primary care specialties with higher signing bonuses and try to make their annual bonuses comparable to surgical specialties, that would help ensure that internal medicine specialists feel they are being paid fairly for their work, he said. “Decreasing the bureaucratic burden and involving physicians in decision-making and determination of compensation would also help,” he said.

Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

Can Insulin Sensitivity Preserve Muscle During Weight Loss?

TOPLINE:

A study found that higher insulin sensitivity is associated with a decrease in lean mass loss during weight loss.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 16-week controlled feeding study involving adults with overweight or obesity.

- The study included 57 participants with a baseline body mass index of 32.1 ± 3.8 kg/m2 .

- Participants were assigned to either a standard (55% carbohydrate) or reduced carbohydrate diet (43% carbohydrate). Both groups consumed 18% protein.

- Body composition was assessed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at baseline and at 16 weeks.

- Insulin sensitivity was measured using an intravenous glucose tolerance test, with multiple linear regression used to analyze the data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower baseline insulin was a predictor of greater lean muscle mass loss during weight loss.

- Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions could allow for personalized approaches to minimize lean mass loss.

- The study suggested that insulin sensitivity plays a significant role in determining the composition of weight lost during dieting.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions may allow for a personalized approach aiming at minimizing lean mass loss,” wrote the authors of the study. This insight underscores the importance of considering insulin sensitivity in weight loss programs to preserve muscle mass. Individuals with low insulin sensitivity may benefit from increasing protein and incorporating resistance training during weight loss.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ciera L. Bartholomew, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama. It was published online in Obesity (Silver Spring).

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s secondary analysis nature and its relatively small sample size limit the ability to establish relationships between insulin sensitivity and lean muscle loss. In addition, all food was provided, and participants all consumed the same protein level.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Comprehensive Diabetes Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and a National Institutes of Health Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A study found that higher insulin sensitivity is associated with a decrease in lean mass loss during weight loss.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 16-week controlled feeding study involving adults with overweight or obesity.

- The study included 57 participants with a baseline body mass index of 32.1 ± 3.8 kg/m2 .

- Participants were assigned to either a standard (55% carbohydrate) or reduced carbohydrate diet (43% carbohydrate). Both groups consumed 18% protein.

- Body composition was assessed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at baseline and at 16 weeks.

- Insulin sensitivity was measured using an intravenous glucose tolerance test, with multiple linear regression used to analyze the data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower baseline insulin was a predictor of greater lean muscle mass loss during weight loss.

- Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions could allow for personalized approaches to minimize lean mass loss.

- The study suggested that insulin sensitivity plays a significant role in determining the composition of weight lost during dieting.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions may allow for a personalized approach aiming at minimizing lean mass loss,” wrote the authors of the study. This insight underscores the importance of considering insulin sensitivity in weight loss programs to preserve muscle mass. Individuals with low insulin sensitivity may benefit from increasing protein and incorporating resistance training during weight loss.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ciera L. Bartholomew, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama. It was published online in Obesity (Silver Spring).

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s secondary analysis nature and its relatively small sample size limit the ability to establish relationships between insulin sensitivity and lean muscle loss. In addition, all food was provided, and participants all consumed the same protein level.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Comprehensive Diabetes Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and a National Institutes of Health Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A study found that higher insulin sensitivity is associated with a decrease in lean mass loss during weight loss.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 16-week controlled feeding study involving adults with overweight or obesity.

- The study included 57 participants with a baseline body mass index of 32.1 ± 3.8 kg/m2 .

- Participants were assigned to either a standard (55% carbohydrate) or reduced carbohydrate diet (43% carbohydrate). Both groups consumed 18% protein.

- Body composition was assessed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at baseline and at 16 weeks.

- Insulin sensitivity was measured using an intravenous glucose tolerance test, with multiple linear regression used to analyze the data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lower baseline insulin was a predictor of greater lean muscle mass loss during weight loss.

- Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions could allow for personalized approaches to minimize lean mass loss.

- The study suggested that insulin sensitivity plays a significant role in determining the composition of weight lost during dieting.

IN PRACTICE:

“Identifying individuals with low insulin sensitivity prior to weight loss interventions may allow for a personalized approach aiming at minimizing lean mass loss,” wrote the authors of the study. This insight underscores the importance of considering insulin sensitivity in weight loss programs to preserve muscle mass. Individuals with low insulin sensitivity may benefit from increasing protein and incorporating resistance training during weight loss.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ciera L. Bartholomew, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama. It was published online in Obesity (Silver Spring).

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s secondary analysis nature and its relatively small sample size limit the ability to establish relationships between insulin sensitivity and lean muscle loss. In addition, all food was provided, and participants all consumed the same protein level.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the Comprehensive Diabetes Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and a National Institutes of Health Research Grant. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advice, Support for Entrepreneurs at AGA Tech 2024

CHICAGO — Have a great tech idea to improve gastroenterology? Start-up companies have the potential to transform the practice of medicine, and to make founders a nice pot of money, but it is a difficult road. At the 2024 AGA Tech Summit, held at the Chicago headquarters of MATTER, a global healthcare startup incubator, investors and gastroenterologists discussed some of the key challenges and opportunities for GI startups.

The road is daunting, and founders must be dedicated to their companies but also maintain life balance. “It is very easy, following your passion, for your life to get out of check. I don’t know what the divorce rate is for entrepreneurs, but I personally was a victim of that. The culture that we built was addictive and it became all encompassing, and at the same time [I neglected] my home life,” Scott Fraser, managing director of the consulting company Fraser Healthcare, said during a “Scars and Stripes” panel at the summit.

For those willing to navigate those waters, there is help. Investors are prepared to provide seed money for companies with good ideas and a strong market. AGA itself has stepped into the investment field with its GI Opportunity Fund, which it launched in 2022 through a partnership with Varia Ventures. The fund’s capital comes from AGA members, with a minimum investment of $25,000. To date, AGA has made investments in six companies, at around $100,000 per company. “It’s not a large amount that we’re investing. We’re a lead investor that signals to other venture capital companies that this is a viable company,” Tom Serena, CEO of AGA, said in an interview.

The fund grew out of AGA’s commitment to boosting early-stage companies in the gastroenterology space. AGA has always supported GI device and tech companies through its Center for GI Innovation and Technology, which sponsored the AGA Tech Summit. The center now provides resources and advice for GI innovators and startups. The AGA Tech Summit has created a gathering place for entrepreneurs and innovators to share their experiences and learn from one another. “But what we were missing was the last mile, which is getting funding to the companies,” said Mr. Serena. The summit itself has been modified to increase the venture capital presence. “That’s the networking we’re trying to [create] here. Venture capitalists are well acquainted with these companies, but we feel that AGA can bring clinical due diligence, and the startups want to be exposed to venture capital,” said Mr. Serena.

During the “Learn from VC Strategists” panel, investors shared advice for entrepreneurs. The emphasis throughout was on marketable ideas that can fundamentally change healthcare practice, though inventions may not have the whiz-bang appeal of some new technologies of years past.

“We’re particularly focused on clinical models that actually work. There were a lot of companies for many years that were doing things that had minimal impact, or very incremental impact. Maybe they were helping identify certain patients, but they weren’t actually engaging those patients. We’re now looking very end-to-end and trying to make sure that it’s not just a good idea, but one that you can actually roll out, engage patients, and see the [return on investment] in that patient data,” said Kelsey Maguire, managing director of the Blue Venture Fund, which is a collaborative effort across Blue Cross Blue Shield companies.

Part of the reason for that shift is that healthcare has evolved in a way that has put more pressure on physicians, according to Barbara H. Jung, MD, AGAF, past president of AGA, who was present for the session. “I think that there’s huge burnout among gastroenterologists, [partly because] some of the systems have been optimized to get the most out of each specialist. I think we just have to get back to making work more enjoyable. [It could be less] fighting with the insurance companies, it could be that you spend less time typing after hours. It could be that it helps the team work more seamlessly, or it could be something that helps the patient prepare, so they have everything ready when they see the doctors. It’s thinking about how healthcare is delivered, and really in a patient and physician-centric way,” Dr. Jung said in an interview.

Anna Haghgooie, managing director of Valtruis, noted that, historically, new technology has been rewarded by the healthcare system. “It’s part of why we find ourselves where we are as an industry: There was nobody in the marketplace that was incented to roll out a cost-reducing technology, and those weren’t necessarily considered grand slams. But [I think] we’re at a tipping point on cost, and as a country will start purchasing in pretty meaningfully different ways, which opens up a lot of opportunities for those practical solutions to be grand slams. Everything that we look at has a component of virtual care, leveraging technology, whether it’s AI or just better workflow tools, better data and intelligence to make business decisions,” said Ms. Haghgooie. She did note that Valtruis does not work much with medical devices.

Specifically in the GI space, one panelist called for a shift away from novel colonoscopy technology. “I don’t know how many more bells and whistles we can ask for colonoscopy, which we’re very dependent on. Not that it’s not important, but I don’t think that’s where the real innovation is going to come. When you think about the cognitive side of the GI business: New diagnostics, things that are predictive of disease states, things that monitor disease, things that help you to know what people’s disease courses will be. I think as more and more interventions are done by endoscopists, you need more tools,” said Thomas Shehab, MD, managing partner at Arboretum Ventures.

Finally, AI has become a central component to investment decisions. Ms. Haghgooie said that Valtruis is focused on the infrastructure surrounding AI, such as the data that it requires to make or help guide decisions. That data can vary widely in quality, is difficult to index, exists in various silos, and is subject to a number of regulatory constraints on how to move or aggregate it. “So, a lot of what we’re focused on are the systems and tools that can enable the next gen application of AI. That’s one piece of the puzzle. The other is, I’d say that every company that we’ve either invested in or are looking at investing in, we ask the question: How are you planning to incorporate and leverage this next gen technology to drive your marginal cost-to-deliver down? In many cases you have to do that through business model redesign, because there is no fee-for-service code to get paid for leveraging AI to reduce your costs. You’ve got to have different payment structures in order to get the benefit of leveraging those types of technologies. When we’re sourcing and looking at deals, we’re looking at both of those angles,” she said.

CHICAGO — Have a great tech idea to improve gastroenterology? Start-up companies have the potential to transform the practice of medicine, and to make founders a nice pot of money, but it is a difficult road. At the 2024 AGA Tech Summit, held at the Chicago headquarters of MATTER, a global healthcare startup incubator, investors and gastroenterologists discussed some of the key challenges and opportunities for GI startups.

The road is daunting, and founders must be dedicated to their companies but also maintain life balance. “It is very easy, following your passion, for your life to get out of check. I don’t know what the divorce rate is for entrepreneurs, but I personally was a victim of that. The culture that we built was addictive and it became all encompassing, and at the same time [I neglected] my home life,” Scott Fraser, managing director of the consulting company Fraser Healthcare, said during a “Scars and Stripes” panel at the summit.

For those willing to navigate those waters, there is help. Investors are prepared to provide seed money for companies with good ideas and a strong market. AGA itself has stepped into the investment field with its GI Opportunity Fund, which it launched in 2022 through a partnership with Varia Ventures. The fund’s capital comes from AGA members, with a minimum investment of $25,000. To date, AGA has made investments in six companies, at around $100,000 per company. “It’s not a large amount that we’re investing. We’re a lead investor that signals to other venture capital companies that this is a viable company,” Tom Serena, CEO of AGA, said in an interview.

The fund grew out of AGA’s commitment to boosting early-stage companies in the gastroenterology space. AGA has always supported GI device and tech companies through its Center for GI Innovation and Technology, which sponsored the AGA Tech Summit. The center now provides resources and advice for GI innovators and startups. The AGA Tech Summit has created a gathering place for entrepreneurs and innovators to share their experiences and learn from one another. “But what we were missing was the last mile, which is getting funding to the companies,” said Mr. Serena. The summit itself has been modified to increase the venture capital presence. “That’s the networking we’re trying to [create] here. Venture capitalists are well acquainted with these companies, but we feel that AGA can bring clinical due diligence, and the startups want to be exposed to venture capital,” said Mr. Serena.

During the “Learn from VC Strategists” panel, investors shared advice for entrepreneurs. The emphasis throughout was on marketable ideas that can fundamentally change healthcare practice, though inventions may not have the whiz-bang appeal of some new technologies of years past.

“We’re particularly focused on clinical models that actually work. There were a lot of companies for many years that were doing things that had minimal impact, or very incremental impact. Maybe they were helping identify certain patients, but they weren’t actually engaging those patients. We’re now looking very end-to-end and trying to make sure that it’s not just a good idea, but one that you can actually roll out, engage patients, and see the [return on investment] in that patient data,” said Kelsey Maguire, managing director of the Blue Venture Fund, which is a collaborative effort across Blue Cross Blue Shield companies.

Part of the reason for that shift is that healthcare has evolved in a way that has put more pressure on physicians, according to Barbara H. Jung, MD, AGAF, past president of AGA, who was present for the session. “I think that there’s huge burnout among gastroenterologists, [partly because] some of the systems have been optimized to get the most out of each specialist. I think we just have to get back to making work more enjoyable. [It could be less] fighting with the insurance companies, it could be that you spend less time typing after hours. It could be that it helps the team work more seamlessly, or it could be something that helps the patient prepare, so they have everything ready when they see the doctors. It’s thinking about how healthcare is delivered, and really in a patient and physician-centric way,” Dr. Jung said in an interview.

Anna Haghgooie, managing director of Valtruis, noted that, historically, new technology has been rewarded by the healthcare system. “It’s part of why we find ourselves where we are as an industry: There was nobody in the marketplace that was incented to roll out a cost-reducing technology, and those weren’t necessarily considered grand slams. But [I think] we’re at a tipping point on cost, and as a country will start purchasing in pretty meaningfully different ways, which opens up a lot of opportunities for those practical solutions to be grand slams. Everything that we look at has a component of virtual care, leveraging technology, whether it’s AI or just better workflow tools, better data and intelligence to make business decisions,” said Ms. Haghgooie. She did note that Valtruis does not work much with medical devices.

Specifically in the GI space, one panelist called for a shift away from novel colonoscopy technology. “I don’t know how many more bells and whistles we can ask for colonoscopy, which we’re very dependent on. Not that it’s not important, but I don’t think that’s where the real innovation is going to come. When you think about the cognitive side of the GI business: New diagnostics, things that are predictive of disease states, things that monitor disease, things that help you to know what people’s disease courses will be. I think as more and more interventions are done by endoscopists, you need more tools,” said Thomas Shehab, MD, managing partner at Arboretum Ventures.

Finally, AI has become a central component to investment decisions. Ms. Haghgooie said that Valtruis is focused on the infrastructure surrounding AI, such as the data that it requires to make or help guide decisions. That data can vary widely in quality, is difficult to index, exists in various silos, and is subject to a number of regulatory constraints on how to move or aggregate it. “So, a lot of what we’re focused on are the systems and tools that can enable the next gen application of AI. That’s one piece of the puzzle. The other is, I’d say that every company that we’ve either invested in or are looking at investing in, we ask the question: How are you planning to incorporate and leverage this next gen technology to drive your marginal cost-to-deliver down? In many cases you have to do that through business model redesign, because there is no fee-for-service code to get paid for leveraging AI to reduce your costs. You’ve got to have different payment structures in order to get the benefit of leveraging those types of technologies. When we’re sourcing and looking at deals, we’re looking at both of those angles,” she said.

CHICAGO — Have a great tech idea to improve gastroenterology? Start-up companies have the potential to transform the practice of medicine, and to make founders a nice pot of money, but it is a difficult road. At the 2024 AGA Tech Summit, held at the Chicago headquarters of MATTER, a global healthcare startup incubator, investors and gastroenterologists discussed some of the key challenges and opportunities for GI startups.

The road is daunting, and founders must be dedicated to their companies but also maintain life balance. “It is very easy, following your passion, for your life to get out of check. I don’t know what the divorce rate is for entrepreneurs, but I personally was a victim of that. The culture that we built was addictive and it became all encompassing, and at the same time [I neglected] my home life,” Scott Fraser, managing director of the consulting company Fraser Healthcare, said during a “Scars and Stripes” panel at the summit.

For those willing to navigate those waters, there is help. Investors are prepared to provide seed money for companies with good ideas and a strong market. AGA itself has stepped into the investment field with its GI Opportunity Fund, which it launched in 2022 through a partnership with Varia Ventures. The fund’s capital comes from AGA members, with a minimum investment of $25,000. To date, AGA has made investments in six companies, at around $100,000 per company. “It’s not a large amount that we’re investing. We’re a lead investor that signals to other venture capital companies that this is a viable company,” Tom Serena, CEO of AGA, said in an interview.

The fund grew out of AGA’s commitment to boosting early-stage companies in the gastroenterology space. AGA has always supported GI device and tech companies through its Center for GI Innovation and Technology, which sponsored the AGA Tech Summit. The center now provides resources and advice for GI innovators and startups. The AGA Tech Summit has created a gathering place for entrepreneurs and innovators to share their experiences and learn from one another. “But what we were missing was the last mile, which is getting funding to the companies,” said Mr. Serena. The summit itself has been modified to increase the venture capital presence. “That’s the networking we’re trying to [create] here. Venture capitalists are well acquainted with these companies, but we feel that AGA can bring clinical due diligence, and the startups want to be exposed to venture capital,” said Mr. Serena.

During the “Learn from VC Strategists” panel, investors shared advice for entrepreneurs. The emphasis throughout was on marketable ideas that can fundamentally change healthcare practice, though inventions may not have the whiz-bang appeal of some new technologies of years past.

“We’re particularly focused on clinical models that actually work. There were a lot of companies for many years that were doing things that had minimal impact, or very incremental impact. Maybe they were helping identify certain patients, but they weren’t actually engaging those patients. We’re now looking very end-to-end and trying to make sure that it’s not just a good idea, but one that you can actually roll out, engage patients, and see the [return on investment] in that patient data,” said Kelsey Maguire, managing director of the Blue Venture Fund, which is a collaborative effort across Blue Cross Blue Shield companies.

Part of the reason for that shift is that healthcare has evolved in a way that has put more pressure on physicians, according to Barbara H. Jung, MD, AGAF, past president of AGA, who was present for the session. “I think that there’s huge burnout among gastroenterologists, [partly because] some of the systems have been optimized to get the most out of each specialist. I think we just have to get back to making work more enjoyable. [It could be less] fighting with the insurance companies, it could be that you spend less time typing after hours. It could be that it helps the team work more seamlessly, or it could be something that helps the patient prepare, so they have everything ready when they see the doctors. It’s thinking about how healthcare is delivered, and really in a patient and physician-centric way,” Dr. Jung said in an interview.

Anna Haghgooie, managing director of Valtruis, noted that, historically, new technology has been rewarded by the healthcare system. “It’s part of why we find ourselves where we are as an industry: There was nobody in the marketplace that was incented to roll out a cost-reducing technology, and those weren’t necessarily considered grand slams. But [I think] we’re at a tipping point on cost, and as a country will start purchasing in pretty meaningfully different ways, which opens up a lot of opportunities for those practical solutions to be grand slams. Everything that we look at has a component of virtual care, leveraging technology, whether it’s AI or just better workflow tools, better data and intelligence to make business decisions,” said Ms. Haghgooie. She did note that Valtruis does not work much with medical devices.

Specifically in the GI space, one panelist called for a shift away from novel colonoscopy technology. “I don’t know how many more bells and whistles we can ask for colonoscopy, which we’re very dependent on. Not that it’s not important, but I don’t think that’s where the real innovation is going to come. When you think about the cognitive side of the GI business: New diagnostics, things that are predictive of disease states, things that monitor disease, things that help you to know what people’s disease courses will be. I think as more and more interventions are done by endoscopists, you need more tools,” said Thomas Shehab, MD, managing partner at Arboretum Ventures.

Finally, AI has become a central component to investment decisions. Ms. Haghgooie said that Valtruis is focused on the infrastructure surrounding AI, such as the data that it requires to make or help guide decisions. That data can vary widely in quality, is difficult to index, exists in various silos, and is subject to a number of regulatory constraints on how to move or aggregate it. “So, a lot of what we’re focused on are the systems and tools that can enable the next gen application of AI. That’s one piece of the puzzle. The other is, I’d say that every company that we’ve either invested in or are looking at investing in, we ask the question: How are you planning to incorporate and leverage this next gen technology to drive your marginal cost-to-deliver down? In many cases you have to do that through business model redesign, because there is no fee-for-service code to get paid for leveraging AI to reduce your costs. You’ve got to have different payment structures in order to get the benefit of leveraging those types of technologies. When we’re sourcing and looking at deals, we’re looking at both of those angles,” she said.

FROM THE 2024 AGA TECH SUMMIT

MS in Men: Unusual, and Unusually Challenging

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE — Disease course, mental health, and social function may be different in male patients.

Among the clinical differences: Men may be diagnosed at an older age, often closer to 30 years of age, and they more often experience memory problems, spinal cord lesions, and motor symptoms. They are at higher risk of progressive-onset disease, but have lower relapse rates. Disability rates are higher in men than in women, but long-term survival is no different. Brain atrophy is also more common among men.

Not all MRI facilities will include brain atrophy assessment, so it is a good idea to put an order in for brain atrophy when there are reasons to be concerned, such as cognitive effects or issues with walking, according to Jeffrey Hernandez, DNP, during a talk at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Dr. Hernandez is affiliated with the University of Miami Multiple Sclerosis Center.

Addressing Sensitive Topics

Men may be less willing to discuss their symptoms, in part because they may have been raised to be tough and stoic. “Looking for help might make them feel more vulnerable,” said Dr. Hernandez. That’s not a feeling that most men are familiar with, he said. Men “don’t want to be deemed or seem weak or dependent on anyone.” Consequently, men are less likely to complain about any symptom, said Dr. Hernandez.

He advised asking more open-ended questions in an effort to draw men out. “Just ask how they’re doing. See if anything has changed from their usual habits, have their activities of daily living changed, has their work performance changed? That can give you an indication. One of my patients [said he] was demoted from [his] position, that the demotion was related to cognitive impairment and the way that he was working. That gives you an idea as to where you can help intervene and perhaps make an improvement for that patient’s quality of life, or consider switching treatments,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Men are less likely to report symptoms such as tingling, physical complaints, cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and sexual dysfunction. That doesn’t mean they’re not experiencing issues, though, especially when it comes to sexual problems. Dr. Hernandez recalled one patient who just stared out the window when asked about his sex life. “Then I said, the next time I want your wife to be here, and then she spilled the beans on everything. So it’s important sometimes to include other members of the family or their partners in the conversation to give you some insight. And perhaps that day it wasn’t a priority for him, but then the next time it was a priority for his wife,” he said.

He pointed out that erectile dysfunction could be due to a physiological response to MS, or to psychological effects.

Low testosterone levels may also play a role in MS, since it is a natural anti-inflammatory hormone. Hypogonadism has been found to be high among men with MS in some studies. MS in men is associated with more enhancing lesions, greater cognitive decline, and increased risk of disability, while high levels of testosterone are linked to neuroprotective effects and lower risk of developing MS.

Men with MS are more likely than women to report suicidal thoughts when depressed, and mental health can be taboo, as men may try to solve problems on their own before seeking help. “But a lot of the times they can use a little bit of help, whether it be from talk therapy or meds. With the expansion of telemedicine, virtual care has skyrocketed in psychiatry. I advocate strongly for it. Psychologytoday.com is a very common portal that I recommend so they can look up providers with their insurances, and they can see who gives in person versus virtual care. They can do it from the comfort of their car. I’ve had people in their car crying because they don’t want to be in their house when they talk to me,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Physical struggles can lead men to feel they’ve lost their independence, and that they are no longer the protector of the household. Divorce is common, which can lead to social isolation. One patient wanted to see Dr. Hernandez monthly, a request that he had to decline. “Sometimes they want to discuss these things and they just don’t have someone to talk to,” said Dr. Hernandez. Social support programs through the National MS Society, the MS Foundation, or the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America may sponsor local programs that could be beneficial.

Dr. Hernandez has no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE — Disease course, mental health, and social function may be different in male patients.

Among the clinical differences: Men may be diagnosed at an older age, often closer to 30 years of age, and they more often experience memory problems, spinal cord lesions, and motor symptoms. They are at higher risk of progressive-onset disease, but have lower relapse rates. Disability rates are higher in men than in women, but long-term survival is no different. Brain atrophy is also more common among men.

Not all MRI facilities will include brain atrophy assessment, so it is a good idea to put an order in for brain atrophy when there are reasons to be concerned, such as cognitive effects or issues with walking, according to Jeffrey Hernandez, DNP, during a talk at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Dr. Hernandez is affiliated with the University of Miami Multiple Sclerosis Center.

Addressing Sensitive Topics

Men may be less willing to discuss their symptoms, in part because they may have been raised to be tough and stoic. “Looking for help might make them feel more vulnerable,” said Dr. Hernandez. That’s not a feeling that most men are familiar with, he said. Men “don’t want to be deemed or seem weak or dependent on anyone.” Consequently, men are less likely to complain about any symptom, said Dr. Hernandez.

He advised asking more open-ended questions in an effort to draw men out. “Just ask how they’re doing. See if anything has changed from their usual habits, have their activities of daily living changed, has their work performance changed? That can give you an indication. One of my patients [said he] was demoted from [his] position, that the demotion was related to cognitive impairment and the way that he was working. That gives you an idea as to where you can help intervene and perhaps make an improvement for that patient’s quality of life, or consider switching treatments,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Men are less likely to report symptoms such as tingling, physical complaints, cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and sexual dysfunction. That doesn’t mean they’re not experiencing issues, though, especially when it comes to sexual problems. Dr. Hernandez recalled one patient who just stared out the window when asked about his sex life. “Then I said, the next time I want your wife to be here, and then she spilled the beans on everything. So it’s important sometimes to include other members of the family or their partners in the conversation to give you some insight. And perhaps that day it wasn’t a priority for him, but then the next time it was a priority for his wife,” he said.

He pointed out that erectile dysfunction could be due to a physiological response to MS, or to psychological effects.

Low testosterone levels may also play a role in MS, since it is a natural anti-inflammatory hormone. Hypogonadism has been found to be high among men with MS in some studies. MS in men is associated with more enhancing lesions, greater cognitive decline, and increased risk of disability, while high levels of testosterone are linked to neuroprotective effects and lower risk of developing MS.

Men with MS are more likely than women to report suicidal thoughts when depressed, and mental health can be taboo, as men may try to solve problems on their own before seeking help. “But a lot of the times they can use a little bit of help, whether it be from talk therapy or meds. With the expansion of telemedicine, virtual care has skyrocketed in psychiatry. I advocate strongly for it. Psychologytoday.com is a very common portal that I recommend so they can look up providers with their insurances, and they can see who gives in person versus virtual care. They can do it from the comfort of their car. I’ve had people in their car crying because they don’t want to be in their house when they talk to me,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Physical struggles can lead men to feel they’ve lost their independence, and that they are no longer the protector of the household. Divorce is common, which can lead to social isolation. One patient wanted to see Dr. Hernandez monthly, a request that he had to decline. “Sometimes they want to discuss these things and they just don’t have someone to talk to,” said Dr. Hernandez. Social support programs through the National MS Society, the MS Foundation, or the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America may sponsor local programs that could be beneficial.

Dr. Hernandez has no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE — Disease course, mental health, and social function may be different in male patients.

Among the clinical differences: Men may be diagnosed at an older age, often closer to 30 years of age, and they more often experience memory problems, spinal cord lesions, and motor symptoms. They are at higher risk of progressive-onset disease, but have lower relapse rates. Disability rates are higher in men than in women, but long-term survival is no different. Brain atrophy is also more common among men.

Not all MRI facilities will include brain atrophy assessment, so it is a good idea to put an order in for brain atrophy when there are reasons to be concerned, such as cognitive effects or issues with walking, according to Jeffrey Hernandez, DNP, during a talk at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Dr. Hernandez is affiliated with the University of Miami Multiple Sclerosis Center.

Addressing Sensitive Topics

Men may be less willing to discuss their symptoms, in part because they may have been raised to be tough and stoic. “Looking for help might make them feel more vulnerable,” said Dr. Hernandez. That’s not a feeling that most men are familiar with, he said. Men “don’t want to be deemed or seem weak or dependent on anyone.” Consequently, men are less likely to complain about any symptom, said Dr. Hernandez.

He advised asking more open-ended questions in an effort to draw men out. “Just ask how they’re doing. See if anything has changed from their usual habits, have their activities of daily living changed, has their work performance changed? That can give you an indication. One of my patients [said he] was demoted from [his] position, that the demotion was related to cognitive impairment and the way that he was working. That gives you an idea as to where you can help intervene and perhaps make an improvement for that patient’s quality of life, or consider switching treatments,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Men are less likely to report symptoms such as tingling, physical complaints, cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and sexual dysfunction. That doesn’t mean they’re not experiencing issues, though, especially when it comes to sexual problems. Dr. Hernandez recalled one patient who just stared out the window when asked about his sex life. “Then I said, the next time I want your wife to be here, and then she spilled the beans on everything. So it’s important sometimes to include other members of the family or their partners in the conversation to give you some insight. And perhaps that day it wasn’t a priority for him, but then the next time it was a priority for his wife,” he said.

He pointed out that erectile dysfunction could be due to a physiological response to MS, or to psychological effects.

Low testosterone levels may also play a role in MS, since it is a natural anti-inflammatory hormone. Hypogonadism has been found to be high among men with MS in some studies. MS in men is associated with more enhancing lesions, greater cognitive decline, and increased risk of disability, while high levels of testosterone are linked to neuroprotective effects and lower risk of developing MS.

Men with MS are more likely than women to report suicidal thoughts when depressed, and mental health can be taboo, as men may try to solve problems on their own before seeking help. “But a lot of the times they can use a little bit of help, whether it be from talk therapy or meds. With the expansion of telemedicine, virtual care has skyrocketed in psychiatry. I advocate strongly for it. Psychologytoday.com is a very common portal that I recommend so they can look up providers with their insurances, and they can see who gives in person versus virtual care. They can do it from the comfort of their car. I’ve had people in their car crying because they don’t want to be in their house when they talk to me,” said Dr. Hernandez.

Physical struggles can lead men to feel they’ve lost their independence, and that they are no longer the protector of the household. Divorce is common, which can lead to social isolation. One patient wanted to see Dr. Hernandez monthly, a request that he had to decline. “Sometimes they want to discuss these things and they just don’t have someone to talk to,” said Dr. Hernandez. Social support programs through the National MS Society, the MS Foundation, or the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America may sponsor local programs that could be beneficial.

Dr. Hernandez has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM CMSC 2024

Gastroenterology Data Trends 2024

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2024 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot GI topics told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

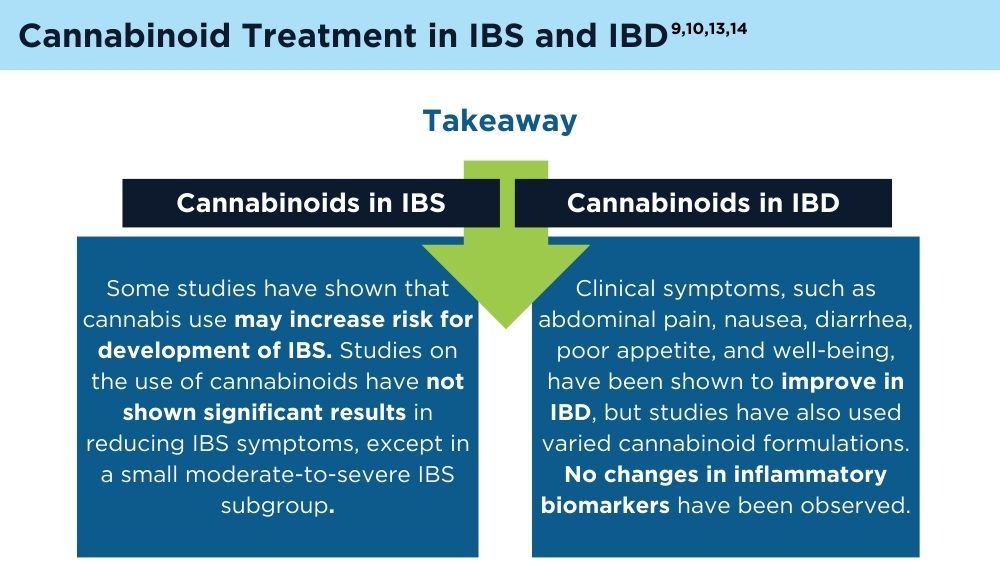

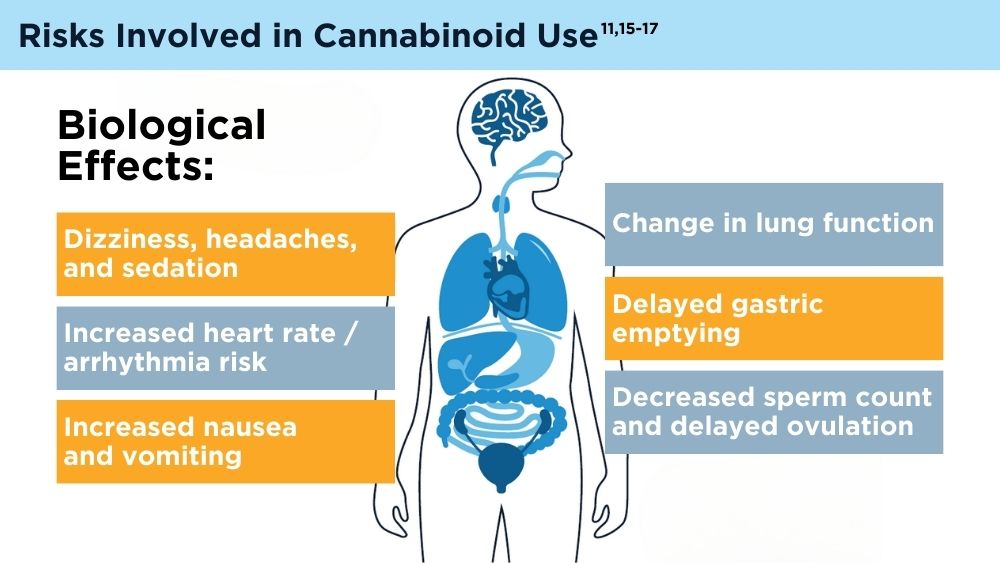

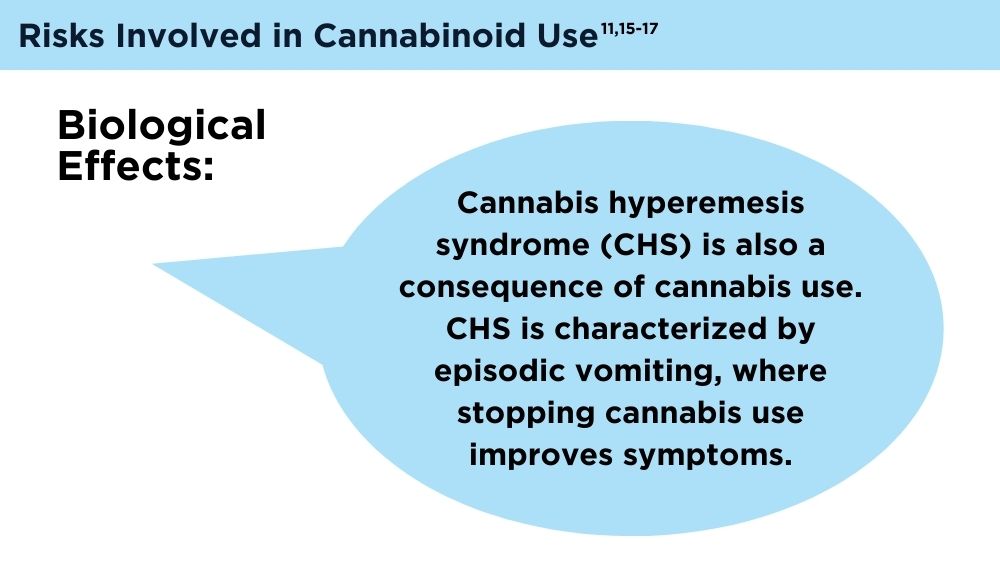

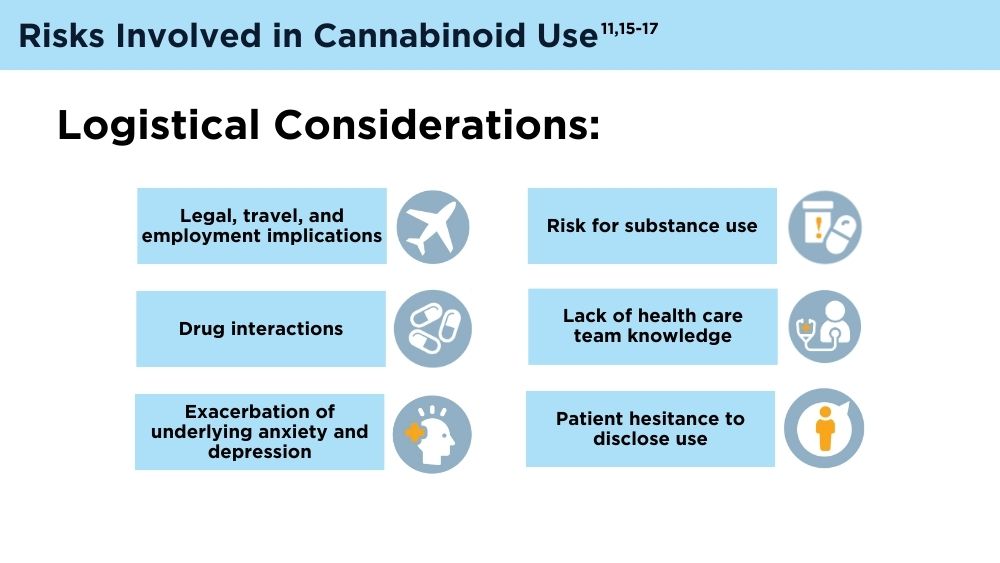

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

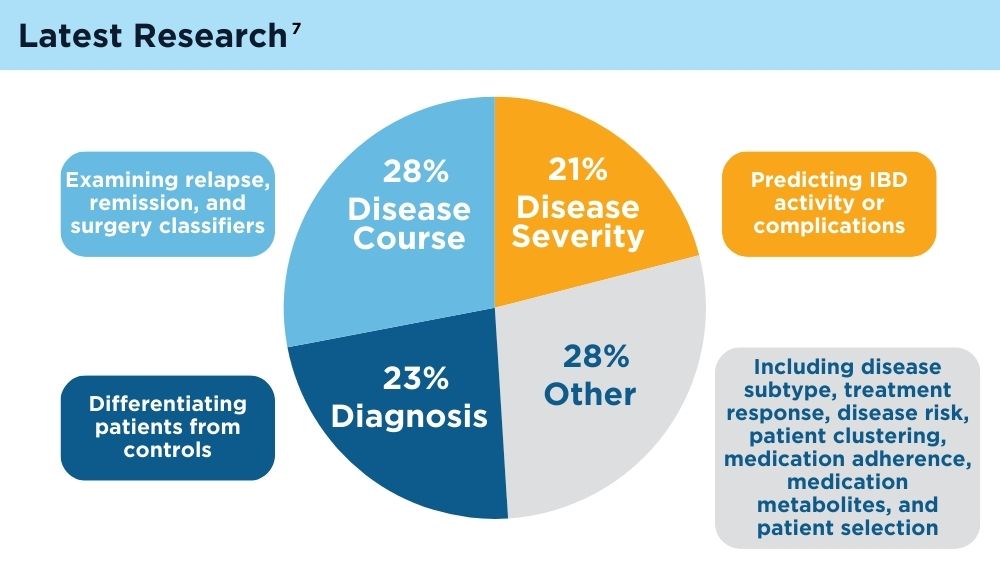

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

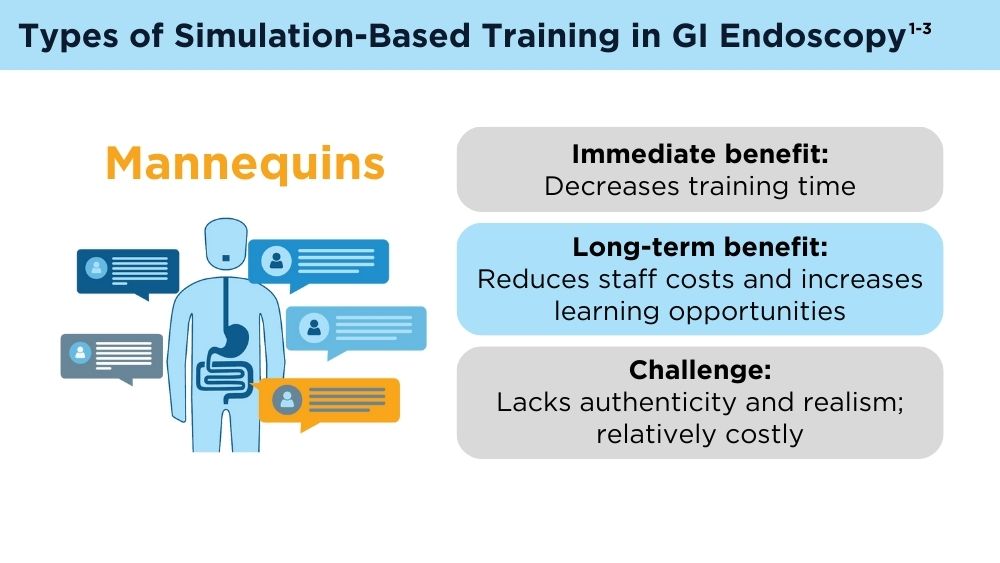

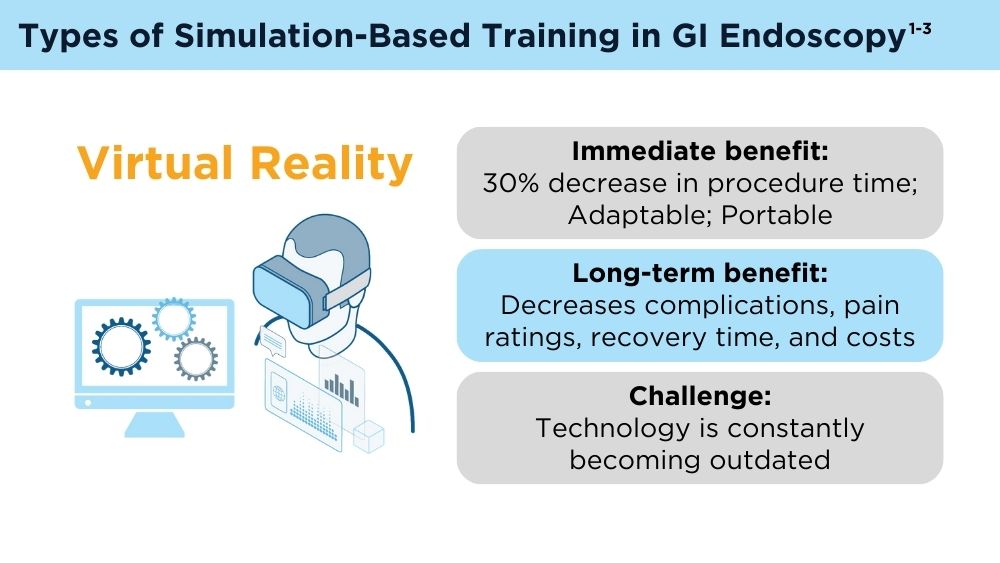

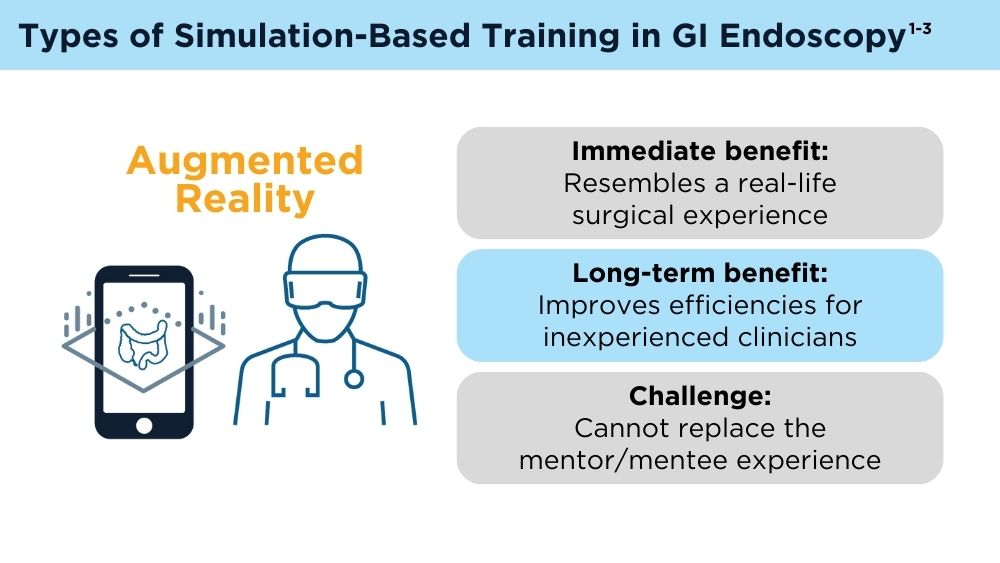

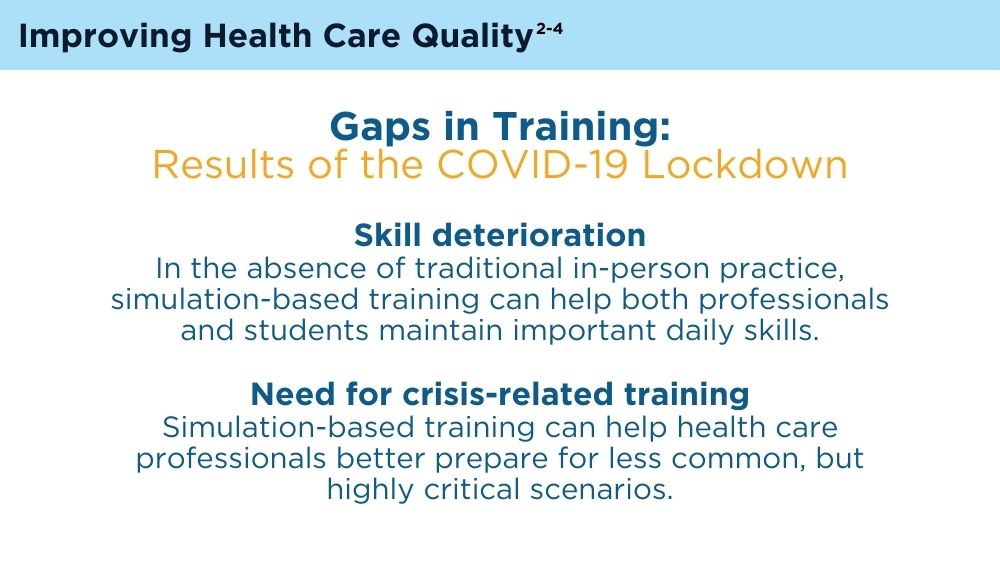

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2024 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot GI topics told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2024 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot GI topics told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases: Beyond EoE

Nirmala Gonsalves, MD, AGAF, FACG - The Changing Face of IBD: Beyond the Western World

Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, AGAF; Paulo Kotze, MD, MS, PhD; Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, AGAF - Role of Non-invasive Biomarkers in the Evaluation and Management of MASLD

Julia J. Wattacheril, MD, MPH - The Emerging Role of Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis and Management of CRC

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF - Cannabinoids and Digestive Disorders

Jami A. Kinnucan, MD, AGAF, FACG - AI and Machine Learning in IBD: Promising Applications and Remaining Challenges

Shirley Cohen-Mekelburg, MD, MS - Simulation-Based Training in Endoscopy: Benefits and Challenges

Richa Shukla, MD - Fluid Management in Acute Pancreatitis

Jorge D. Machicado, MD, MPH

‘Groundbreaking’ Trial Shows Survival Benefits in Lung Cancer

These are results of the ADRIATIC trial, the first planned interim analysis of the randomized, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study comparing the PD-L 1 antibody durvalumab vs placebo in patients with stage I-III limited stage disease and prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Lead author David R. Spigel, MD, drew several rounds of applause from an enthusiastic audience when he presented this data, at the plenary session of the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago.

“ADRIATIC is the first positive, global phase 3 trial of immunotherapy in limited stage SCLC,” said Lauren Byers, MD, the discussant in the session.

“This groundbreaking trial sets a new standard of care with consolidative durvalumab following concurrent chemoradiation,” continued Dr. Byers, who is professor and thoracic section chief in the Department of Thoracic/Head and Neck Medical Oncology at the University of Texas MD Andersen Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

ADRIATIC Methods and Results

The new study enrolled 730 patients and randomized them between 1 and 42 days after concurrent chemoradiation to one of three treatments: durvalumab 1500 mg; durvalumab plus tremelimumab 75 mg; or placebo. Treatment was continued for a maximum of 24 months, or until progression or intolerable toxicity.

The study had dual primary endpoints of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for durvalumab vs placebo. The researchers have not yet looked at the results for the secondary endpoints of OS and PFS for patients treated with durvalumab plus tremelimumab vs placebo.

After a median follow-up of 3 years, there was a median OS of 55.9 months in the durvalumab-treated patients, compared with 33.4 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73), and, at a median follow-up of 2 years, there was median PFS of 16.6 months vs 9.2 months respectively (HR, 0.76).

New Standard of Care for Patients with LS-SCLC

“This study had a very good safety profile,” said Dr. Spigel, who is also a medical oncologist and the chief scientific officer at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tennessee, during his presentation.

“Looking at severe grade 3 or 4 events, these were nearly identical in either arm at 24%. Looking at any-grade immune-mediated AEs, these were 31.2% and 10.2% respectively, and then looking at radiation pneumonitis or pneumonitis, the rates were 38.2% in the durvalumab arm, compared with 30.2% in the placebo arm,” Dr. Spigel said.

Noting that there have been no major advances in the treatment of LS-SCLC for several decades, with most patients experiencing recurrences within 2 years of the cCRT standard of care, Dr. Spigel said “consolidation durvalumab will become the new standard of care for patients with LS-SCLC who have not progressed after cCRT.”

Toby Campbell, MD, a thoracic oncologist, who is professor and chief of Palliative Care at the University of Wisconsin, in Madison, Wisconsin, agrees.

“I take care of patients with small cell lung cancer, an aggressive cancer with high symptom burden that devastates patients and families in its wake,” said Dr. Campbell, during an interview. “About 15% of patients luckily present when the cancer is still contained in the chest and is potentially curable. However, with current treatments we give, which include chemotherapy together with radiation, we are ‘successful’ at curing one in four people.

“This study presents a new treatment option which makes a big difference to patients like mine,” Dr. Campbell continued. “For example, at the 2-year time point, nearly half of patients are still cancer-free. These folks have the opportunity to live their lives more fully, unburdened by the symptoms and dread this disease brings. If approved, I think this treatment would immediately be appropriate to use in clinic.

“Further, oncologists are comfortable using this medication as it is already FDA-approved and used similarly in non–small cell lung cancer.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Spigel discloses consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lyell Immunopharma, MedImmune, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure, and Sanofi/Aventis. He has also received research funding from many companies, and travel, accommodations, and other expense reimbursements from AstraZeneca, Genentech, and Novartis.

Dr. Byers discloses honoraria from and consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Dohme, Novartis, and Puma Biotechnology. He also has received research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Campbell has served as an advisor for Novocure and Genentech.

These are results of the ADRIATIC trial, the first planned interim analysis of the randomized, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study comparing the PD-L 1 antibody durvalumab vs placebo in patients with stage I-III limited stage disease and prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Lead author David R. Spigel, MD, drew several rounds of applause from an enthusiastic audience when he presented this data, at the plenary session of the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago.

“ADRIATIC is the first positive, global phase 3 trial of immunotherapy in limited stage SCLC,” said Lauren Byers, MD, the discussant in the session.

“This groundbreaking trial sets a new standard of care with consolidative durvalumab following concurrent chemoradiation,” continued Dr. Byers, who is professor and thoracic section chief in the Department of Thoracic/Head and Neck Medical Oncology at the University of Texas MD Andersen Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

ADRIATIC Methods and Results

The new study enrolled 730 patients and randomized them between 1 and 42 days after concurrent chemoradiation to one of three treatments: durvalumab 1500 mg; durvalumab plus tremelimumab 75 mg; or placebo. Treatment was continued for a maximum of 24 months, or until progression or intolerable toxicity.

The study had dual primary endpoints of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for durvalumab vs placebo. The researchers have not yet looked at the results for the secondary endpoints of OS and PFS for patients treated with durvalumab plus tremelimumab vs placebo.

After a median follow-up of 3 years, there was a median OS of 55.9 months in the durvalumab-treated patients, compared with 33.4 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73), and, at a median follow-up of 2 years, there was median PFS of 16.6 months vs 9.2 months respectively (HR, 0.76).

New Standard of Care for Patients with LS-SCLC

“This study had a very good safety profile,” said Dr. Spigel, who is also a medical oncologist and the chief scientific officer at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tennessee, during his presentation.

“Looking at severe grade 3 or 4 events, these were nearly identical in either arm at 24%. Looking at any-grade immune-mediated AEs, these were 31.2% and 10.2% respectively, and then looking at radiation pneumonitis or pneumonitis, the rates were 38.2% in the durvalumab arm, compared with 30.2% in the placebo arm,” Dr. Spigel said.

Noting that there have been no major advances in the treatment of LS-SCLC for several decades, with most patients experiencing recurrences within 2 years of the cCRT standard of care, Dr. Spigel said “consolidation durvalumab will become the new standard of care for patients with LS-SCLC who have not progressed after cCRT.”

Toby Campbell, MD, a thoracic oncologist, who is professor and chief of Palliative Care at the University of Wisconsin, in Madison, Wisconsin, agrees.

“I take care of patients with small cell lung cancer, an aggressive cancer with high symptom burden that devastates patients and families in its wake,” said Dr. Campbell, during an interview. “About 15% of patients luckily present when the cancer is still contained in the chest and is potentially curable. However, with current treatments we give, which include chemotherapy together with radiation, we are ‘successful’ at curing one in four people.

“This study presents a new treatment option which makes a big difference to patients like mine,” Dr. Campbell continued. “For example, at the 2-year time point, nearly half of patients are still cancer-free. These folks have the opportunity to live their lives more fully, unburdened by the symptoms and dread this disease brings. If approved, I think this treatment would immediately be appropriate to use in clinic.

“Further, oncologists are comfortable using this medication as it is already FDA-approved and used similarly in non–small cell lung cancer.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Spigel discloses consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lyell Immunopharma, MedImmune, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure, and Sanofi/Aventis. He has also received research funding from many companies, and travel, accommodations, and other expense reimbursements from AstraZeneca, Genentech, and Novartis.

Dr. Byers discloses honoraria from and consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Dohme, Novartis, and Puma Biotechnology. He also has received research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Campbell has served as an advisor for Novocure and Genentech.

These are results of the ADRIATIC trial, the first planned interim analysis of the randomized, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study comparing the PD-L 1 antibody durvalumab vs placebo in patients with stage I-III limited stage disease and prior concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Lead author David R. Spigel, MD, drew several rounds of applause from an enthusiastic audience when he presented this data, at the plenary session of the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago.

“ADRIATIC is the first positive, global phase 3 trial of immunotherapy in limited stage SCLC,” said Lauren Byers, MD, the discussant in the session.

“This groundbreaking trial sets a new standard of care with consolidative durvalumab following concurrent chemoradiation,” continued Dr. Byers, who is professor and thoracic section chief in the Department of Thoracic/Head and Neck Medical Oncology at the University of Texas MD Andersen Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

ADRIATIC Methods and Results

The new study enrolled 730 patients and randomized them between 1 and 42 days after concurrent chemoradiation to one of three treatments: durvalumab 1500 mg; durvalumab plus tremelimumab 75 mg; or placebo. Treatment was continued for a maximum of 24 months, or until progression or intolerable toxicity.

The study had dual primary endpoints of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for durvalumab vs placebo. The researchers have not yet looked at the results for the secondary endpoints of OS and PFS for patients treated with durvalumab plus tremelimumab vs placebo.

After a median follow-up of 3 years, there was a median OS of 55.9 months in the durvalumab-treated patients, compared with 33.4 months in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73), and, at a median follow-up of 2 years, there was median PFS of 16.6 months vs 9.2 months respectively (HR, 0.76).

New Standard of Care for Patients with LS-SCLC

“This study had a very good safety profile,” said Dr. Spigel, who is also a medical oncologist and the chief scientific officer at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tennessee, during his presentation.

“Looking at severe grade 3 or 4 events, these were nearly identical in either arm at 24%. Looking at any-grade immune-mediated AEs, these were 31.2% and 10.2% respectively, and then looking at radiation pneumonitis or pneumonitis, the rates were 38.2% in the durvalumab arm, compared with 30.2% in the placebo arm,” Dr. Spigel said.

Noting that there have been no major advances in the treatment of LS-SCLC for several decades, with most patients experiencing recurrences within 2 years of the cCRT standard of care, Dr. Spigel said “consolidation durvalumab will become the new standard of care for patients with LS-SCLC who have not progressed after cCRT.”

Toby Campbell, MD, a thoracic oncologist, who is professor and chief of Palliative Care at the University of Wisconsin, in Madison, Wisconsin, agrees.

“I take care of patients with small cell lung cancer, an aggressive cancer with high symptom burden that devastates patients and families in its wake,” said Dr. Campbell, during an interview. “About 15% of patients luckily present when the cancer is still contained in the chest and is potentially curable. However, with current treatments we give, which include chemotherapy together with radiation, we are ‘successful’ at curing one in four people.

“This study presents a new treatment option which makes a big difference to patients like mine,” Dr. Campbell continued. “For example, at the 2-year time point, nearly half of patients are still cancer-free. These folks have the opportunity to live their lives more fully, unburdened by the symptoms and dread this disease brings. If approved, I think this treatment would immediately be appropriate to use in clinic.

“Further, oncologists are comfortable using this medication as it is already FDA-approved and used similarly in non–small cell lung cancer.”

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. Dr. Spigel discloses consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lyell Immunopharma, MedImmune, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Novartis, Novocure, and Sanofi/Aventis. He has also received research funding from many companies, and travel, accommodations, and other expense reimbursements from AstraZeneca, Genentech, and Novartis.

Dr. Byers discloses honoraria from and consulting or advisory roles with Abbvie, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Dohme, Novartis, and Puma Biotechnology. He also has received research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Campbell has served as an advisor for Novocure and Genentech.

FROM ASCO 2024

Should ER-Low Breast Cancer Patients Be Offered Endocrine Therapy?

For women with early-stage estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer, adjuvant endocrine therapy is known to decrease the likelihood of recurrence and improve survival, while omitting the therapy is associated with a higher risk of death.

For that reason, current guidelines, including those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) for patients with estrogen-receptor positive (ER+) breast cancers.

But these and other guidelines do not make recommendations for a class of tumors deemed estrogen receptor low positive, often referred to as “ER-low,” a category in which ER is seen expressed in between 1% and 10% of cells. This is because benefits of endocrine therapy have not been demonstrated in patients with ER-low disease.

The findings showed that omitting endocrine therapy after surgery and chemotherapy was associated with a 25% higher chance of death within 3 years in ER-low patients.

Endocrine therapy, the investigators say, should therefore be offered to all patients with ER-low cancers, at least until it can be determined which subgroups are most likely to benefit.

How Was the Study Conducted?

Grace M. Choong, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and her colleagues, looked at 2018-2020 data from the National Cancer Database for more than 350,000 female patients with stages 1-3, ER+ breast cancer. From among these they identified about 7000 patients with ER-low cancers who had undergone adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

“We specifically wanted to focus on those treated with chemotherapy as these patients have a higher risk of recurrence in our short interval follow-up,” Dr. Choong said during her presentation.

Patients’ median age was 55 years, and three-quarters of them were White. Their tumors were more likely to be HER2-negative (65%), PR-negative (73%), have higher Ki-67 expression, and have a higher clinical stage (73% grade III).

Forty-two percent of patients did not undergo AET as part of their treatment regimen, with various tumor factors seen associated with AET omission. At a median 3 years of follow-up, 586 patients had died. After the researchers controlled for age, comorbidities, year of diagnosis, tumor factors, and pathologic stage, the effect of omitting AET still resulted in significantly worse survival: (HR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05-1.48, P = .01).

Mortality was driven by patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, who comprised nearly half the study cohort. In these patients, omission of endocrine therapy was associated with a 27% higher risk of death (HR 1.27, 1.10-1.58). However, for those with a complete pathological response following chemotherapy, omission of endocrine therapy was not associated with a higher risk of death (HR 1.06; 0.62-1.80).

The investigators noted several limitations of their study, including a retrospective design and no information available on recurrence or the duration of endocrine therapy.

Why Is Endocrine Therapy So Frequently Omitted in This Patient Group?

Matthew P. Goetz, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, the study’s corresponding author, said in an interview that in Sweden, for example, ER-low patients are explicitly not offered endocrine therapy based on Swedish guidelines.

In other settings, he said, it is unclear what is happening.

“Are patients refusing it? Do physicians not even offer it because they think there is no value? We do not have that granular detail, but our data right now suggests a physician should be having this conversation with patients,” he said.

Which ER-Low Patients Are Likely To Benefit?

The findings apply mostly to patients with residual disease after chemotherapy, and underlying biological factors are likely the reason, Dr. Goetz said.

ER-low patients are a heterogeneous group, he explained.

“In genomic profiling, where we look at the underlying biology of these cancers, most of the ER-low cancers are considered the basal subtype of triple negative breast cancer. Those patients should have absolutely zero benefit from endocrine therapy. But there is another group, referred to as the luminal group, which comprises anywhere from 20% to 30% of the ER-low patients.”

Dr. Goetz said he expects to find that this latter group are the patients benefiting from endocrine therapy when they have residual disease.

“We are not yet at the point of saying to patients, ‘you have residual disease after chemotherapy. Let’s check your tumor to see if it is the basal or luminal subtype.’ But that is something that we are planning to look into. What is most important right now is that clinicians be aware of these data, and that there is a suggestion that omitting endocrine therapy may have detrimental effects on survival in this subgroup of patients.”

Are the Findings Compelling Enough To Change Clinical Practice Right Away?

In an interview about the findings, Eric Winer, MD, of the Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, cautioned that due to the retrospective study design, “we don’t know how doctors made decisions about who got endocrine therapy and who didn’t.”