User login

Rates and Characteristics of Medical Malpractice Claims Against Hospitalists

The prospect of facing a medical malpractice claim is a source of apprehension for physicians that affects physician behavior, including leading to defensive medicine.1-3 Overall, annual defensive medicine costs have been estimated at $45.6 billion,4 and surveys of hospitalists indicate that 13.0% to 37.5% of hospitalist healthcare costs involve defensive medicine.5,6 Despite the impact of malpractice concerns on hospitalist practice and the unprecedented growth of the field of hospital medicine, relatively few studies have examined the liability environment surrounding hospitalist practice.7,8 The specific issue of malpractice claims rates faced by hospitalists has received even less attention in the medical literature.8

A better understanding of the contributing factors and other attributes of malpractice claims can help guide patient safety initiatives and inform hospitalists’ level of concern regarding liability. Although most medical errors do not result in a malpractice claim,9,10 the majority of malpractice claims in which there is an indemnity payment involve medical injury due to clinician error.11 Even malpractice claims that do not result in an indemnity payment represent opportunities to identify patient safety and risk management vulnerabilities.12

We used a national malpractice claims database to analyze the characteristics of claims made against hospitalists, including claims rates. In addition to claims rates, we also analyzed the other types of providers named in hospitalist claims given the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to hospital medicine.13,14 To provide context for understanding hospitalist liability data, we present data on other specialties. We also describe a model to predict whether hospitalist malpractice claims will close with an indemnity payment.

METHODS

Data Sources and Elements

This analysis used a repository of malpractice claims maintained by CRICO, the captive malpractice insurer of the Harvard-affiliated medical institutions. This database, the Comparative Benchmarking System, a

Injury severity was based on a widely used scale developed for malpractice claims by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.16 Low injury severity included emotional injury and temporary insignificant injury. Medium injury severity included temporary minor, temporary major, and permanent minor injury. High injury severity included permanent significant injury through death. Because this study used a database assembled for operational and patient safety purposes and was not human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not needed.

Study Cohort

Malpractice claims included formal lawsuits or written requests for compensation for negligent medical care. Ho

Statistical Analysis

Malpractice claims rates were treated as Poisson rates and compared using a Z-test. Malpractice claims rates are expressed as claims per 100 physician-years. Each physician-year represents 1 year of coverage of one physician by the medical malpractice carrier whose data were used. Physician-years represent the duration of time physicians practiced during which they were insured by the malpractice carrier and, as such, could have been subject to a malpractice claim that would have been included in our data. Claims rates are based on the subset of the malpractice claims in the study for which the number of physician-years of coverage is available, representing 8.2% of hospitalist claims and 11.6% of all claims.

Comparisons of the percentages of cases closing with an indemnity payment, as well as the percentages of cases in different allegation type and clinical severity categories, were made using the Fisher exact test. Indemnity payment amounts were inflation-adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Comparisons of indemnity payment amounts between physician specialties were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank sum test given that the distribution of the payment amounts appeared nonnormal; this was confirmed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to predict the binary outcome of whether a hospitalist case would close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), based on the 1,216 hospitalist claims. The predictors used in this regression model were chosen a priori based on hypotheses about what factors drive the likelihood that a case closes with payment. Both the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the predictors are presented. The adjusted model is adjusted for all the other predictors contained in the model. All reported P values are two-sided. The statistical analysis was carried out using JMP Pro version 15 (SAS Institute Inc) and Minitab version 19 (Minitab LLC).

RESULTS

We identified 1,216 hospital medicine malpractice claims from our database. Claims rates were calculated from the subset of our data for which physician-years were available—including 5,140 physician-years encompassing 100 claims, representing 8.2% of all hospitalist claims studied. An additional 18,644 malpractice claims from five other specialties—nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialists, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry—were analyzed to provide context for the hospitalist claims.

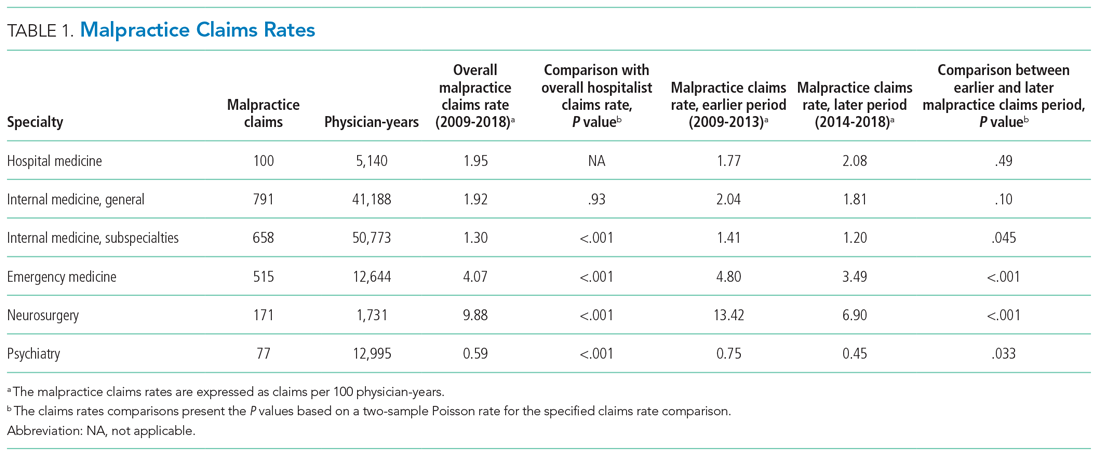

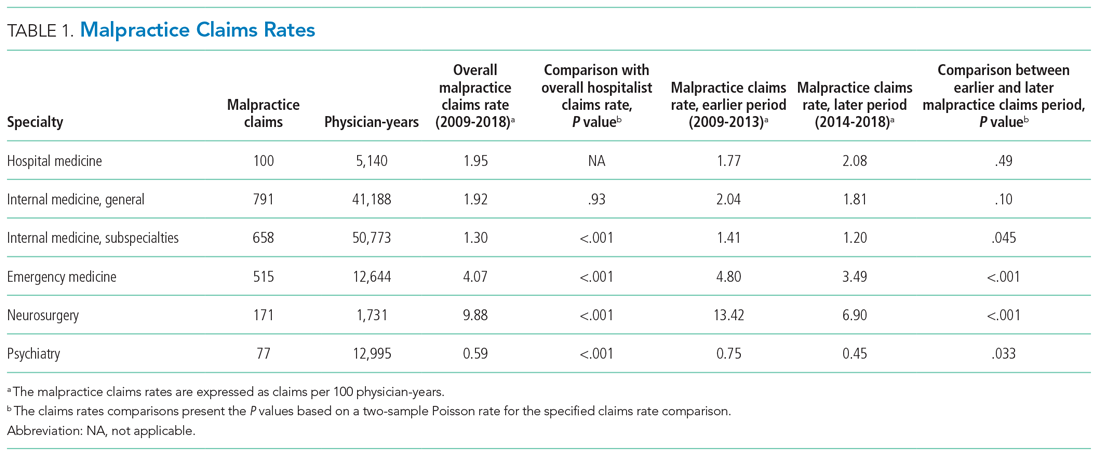

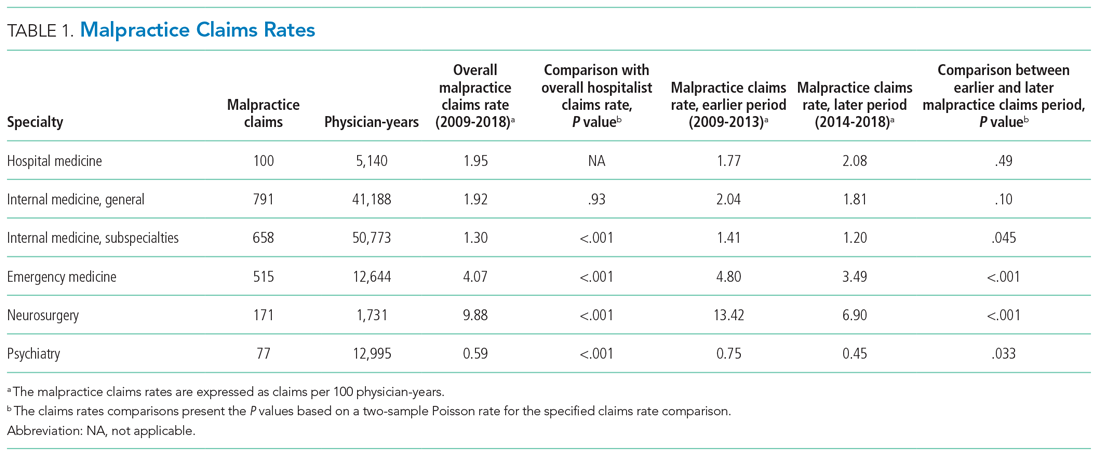

The malpractice claims rate for hospitalists was significantly higher than the rate for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001), though they were not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years; P = .93) (Table 1). Compared with emergency medicine physicians, with whom hospitalists are sometimes compared due to both specialties being defined by their site of practice and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships, hospitalists had a significantly lower claims rate (1.95 vs 4.07 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001).

An assessment of the temporal trends in the claims rates, based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period (2014-2018 vs 2009-2013), showed that the claims rate for hospitalists was increasing, but at a rate that did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). In contrast, the claims rates for the five other specialties assessed decreased over time, and the decreases were significant for four of these five other specialties (internal medicine subspecialties, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry).

Multiple claims against a single physician were uncommon in our hospitalist malpractice claims data. Among the 100 claims that were used to calculate the claims rates, one physician was named in 2 claims, and all the other physicians were named in only a single claim. Among all of the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims we analyzed, there were eight physicians who were named in more than 1 claim, seven of whom were named in 2 claims, and one of whom was named in 3 claims.

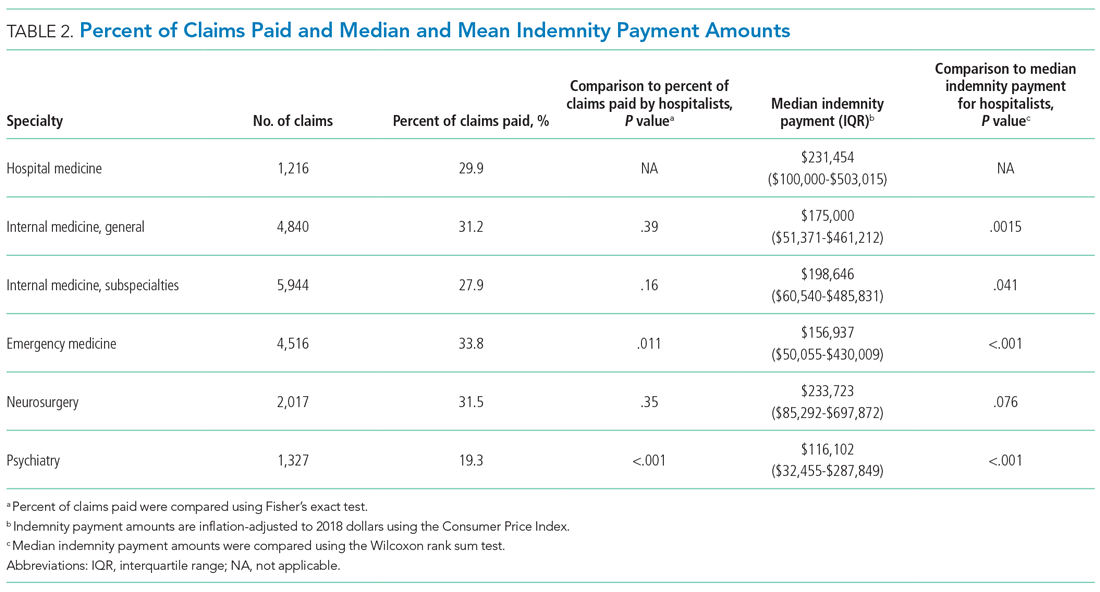

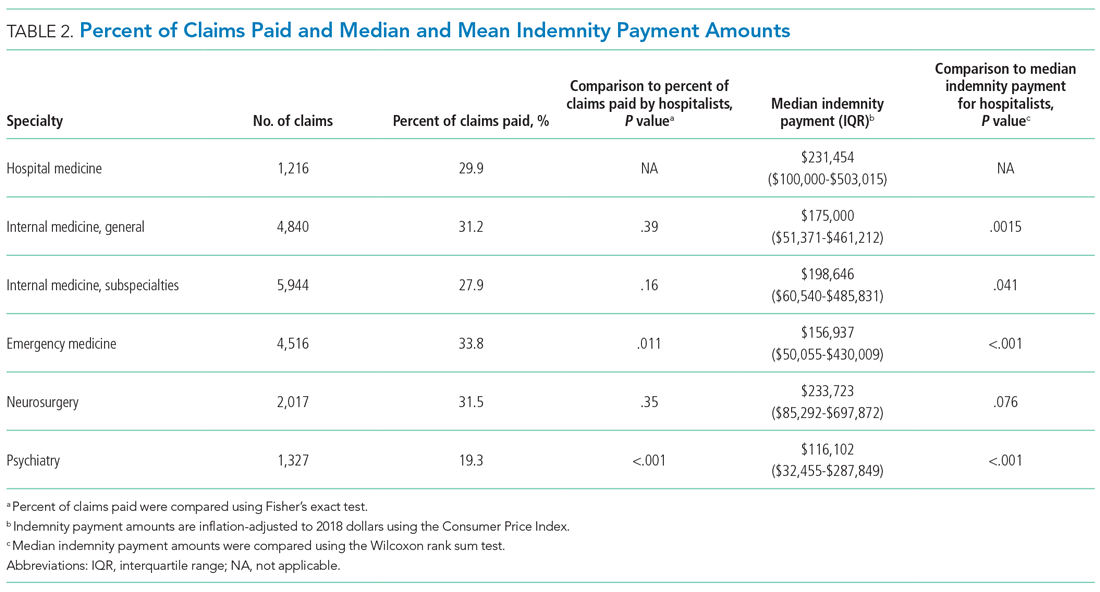

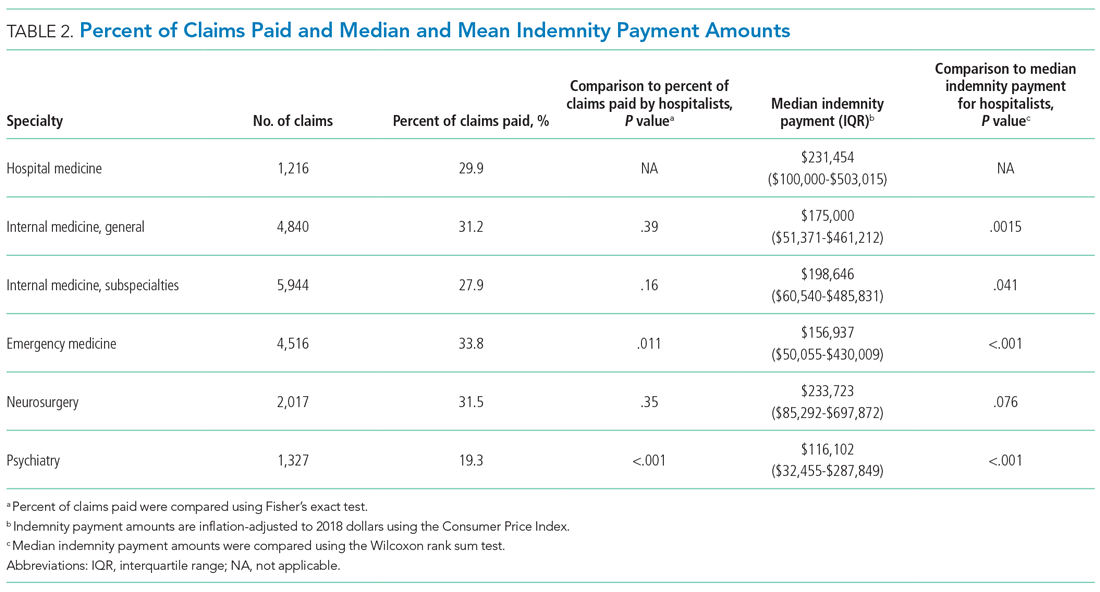

The median indemnity payment for hospitalist claims was $231,454 (interquartile range [IQR], $100,000-$503,015), similar to the median indemnity payment for neurosurgery ($233,723; IQR, $85,292-$697,872), though significantly greater than the median indemnity payment for the other four specialties studied (Table 2). Among the hospitalist claims, 29.9% resulted in an indemnity payment, not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialties, or neurosurgery, but significantly lower than the rate for emergency medicine (33.8%; P = .011). No

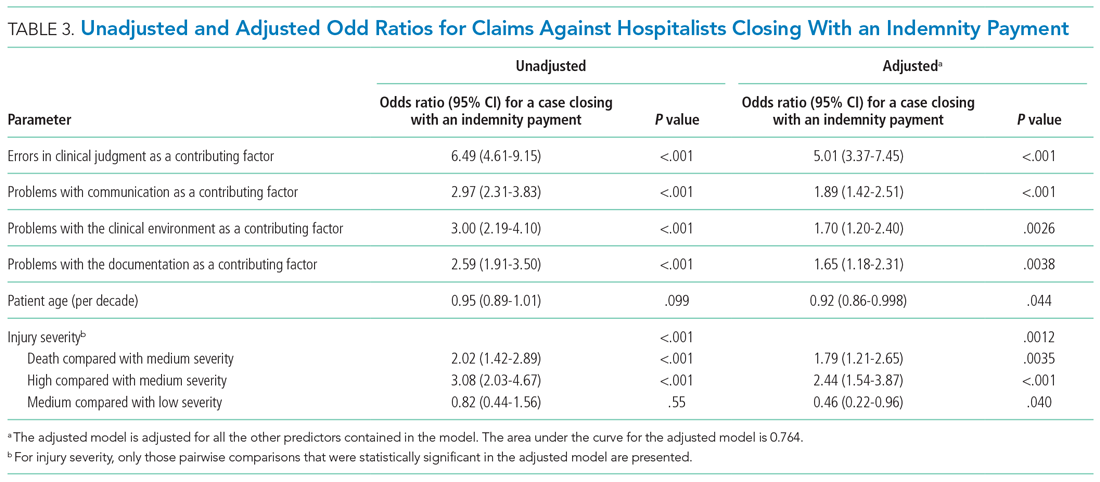

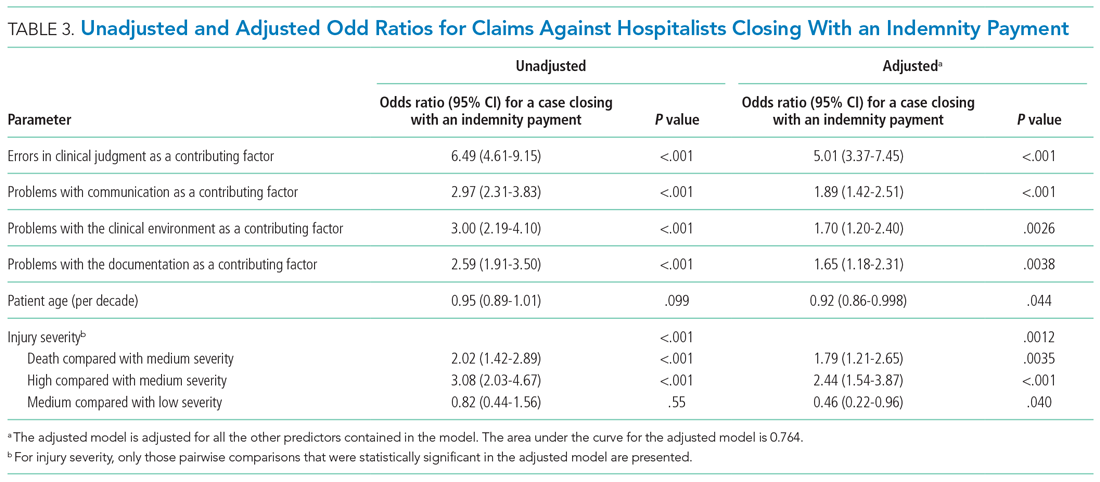

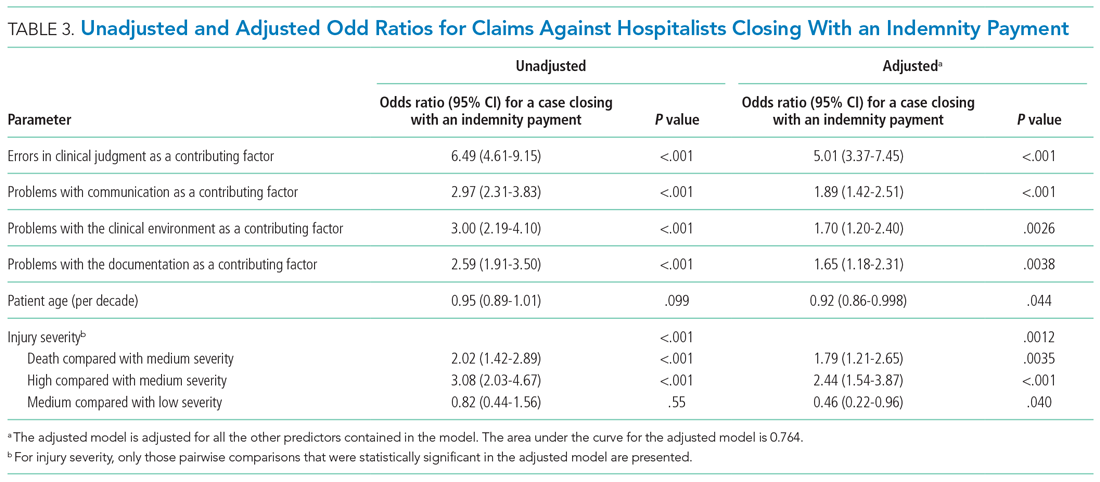

We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the effect of different factors on the likelihood of a hospitalist case closing with an indemnity payment, compared with no payment (Table 3). In the multivariable model, the presence of an error in clinical judgment had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 5.01 (95% CI, 3.37-7.45; P < .001) for a claim closing with payment, the largest effect found. The presence of problems with communication (AOR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.42-2.51; P < .001), the clinical environment (eg, weekend/holiday or clinical busyness; AOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20-2.40; P = .0026), and documentation (AOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.18-2.31; P = .0038) were also positive predictors of claims closing with payment. Greater patient age (per decade) was a negative predictor of the likelihood of a claim closing with payment (AOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.998), though it was of borderline statistical significance (P = .044).

We also assessed multiple clinical attributes of hospitalist malpractice claims, including the major allegation type and injury severity (Appendix Table). Among the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims studied, the most common allegation types were for errors related to medical treatment (n = 482; 39.6%), diagnosis (n = 446; 36.7%), and medications (n = 157; 12.9%). Among the hospitalist claims, 888 (73.0%) involved high-severity injury, and 674 (55.4%) involved the death of the patient. The percentages of cases involving high-severity injury and death were significantly greater for hospitalists, compared with that of the other specialties studied (P < .001 for all pairwise comparisons). Of the six specialties studied, hospital medicine was the only one in which the percentage of cases involving death exceeded 50%.

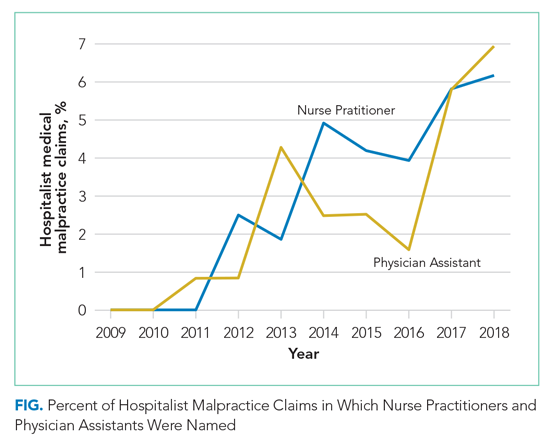

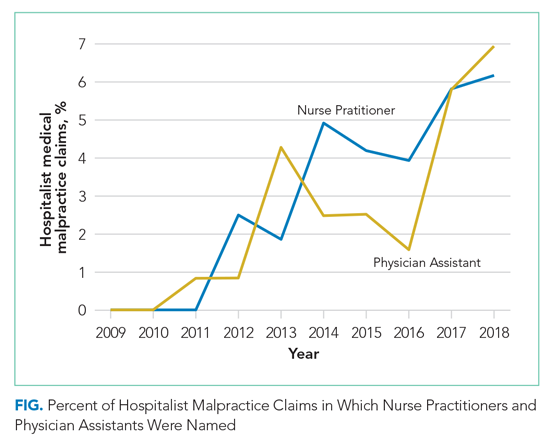

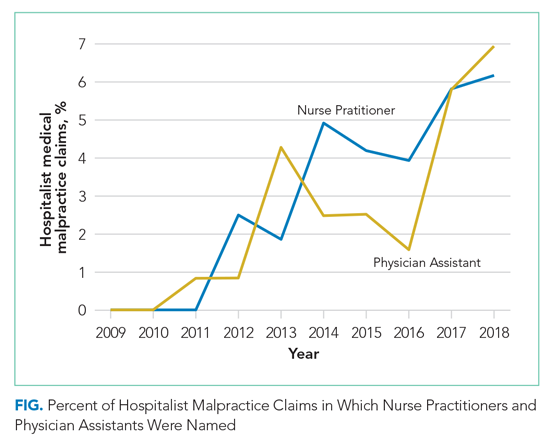

Hospital medicine is typically team-based, and we evaluated which other services were named in claims with hospital medicine as the primary responsible service. The clinician groups most commonly named in hospitalist claims were nursing (n = 269; 22.1%), followed by emergency medicine (n = 91; 7.5%), general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%), cardiology (n = 49; 4.0%), and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%) (Appendix Figure). During the first 2 years of the study period, no physician assistants (PAs) or nurse practitioners (NPs) were named in hospitalist claims. Over the study period, the proportion of hospitalist cases also naming PAs and NPs increased steadily, reaching 6.9% and 6.2% of claims, respectively, in 2018 (Figure) (P < .001 for NPs and P = .037 for PAs based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period).

DISCUSSION

We found that the average annual claims rate for hospitalists was similar to that for nonhospitalist general internists (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years) but significantly greater than that for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years). Hospitalist claims rates showed a notable temporal trend—a nonsignificant increase—over the study period (2009-2018). This contrasts with the five other specialties studied, all of which had decreasing claims rates, four of which were significant. An analysis of a different national malpractice claims database, the NPDB, found that the rate of paid malpractice claims overall decreased 55.7% during the period 1992-2014, again contrasting with the trend we found for hospitalist claims rates.17

We posit several explanations for why the malpractice claims rate trend for hospitalists has diverged from that of other specialties. There has been a large expansion in the number of hospitalists in the United States.18 With this increasing demand, many young physicians have entered the hospital medicine field. In a survey of general internal medicine physicians conducted by the Society of General Internal Medicine, 73% of hospitalists were aged 25 to 44 years, significantly greater than the 45% in this age range among nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians.19 Hospitalists in their first year of practice have higher mortality rates than more experienced hospitalists.20 Therefore, the relative inexperience of hospitalists, driven by this high demand, could be putting them at increased risk of medical errors and resulting malpractice claims. The higher mortality rate among hospitalists in their first year of practice could be due to a lack of familiarity with the systems of care, such as managing test results and obtaining appropriate consults.20 This possibility suggests that enhanced training and mentorship could be valuable as a strategy to both improve the quality of care and reduce medicolegal risk. The increasing demand for hospitalists could also be affecting the qualification level of physicians entering the field.

Our analysis also showed that the severity of injury in hospitalist claims was greater than that for the other specialties studied. In addition, the percentage of claims involving death was greater for hospitalists than that for the other specialties. The increased acuity of inpatients, compared with that of outpatients—and the trend, at least for some conditions, of increased inpatient acuity over time21,22— could account for the high injury severity seen among hospitalist claims. Given the positive correlation between injury severity and the size of indemnity payments made on malpractice claims,12 the high injury severity seen in hospitalist claims was very likely a driver of the high indemnity payments observed among the hospitalist claims.

The relationship between injury severity and financial outcomes is supported by the results of our multivariable regression model (Table 3). Compared with medium-severity injury claims, both death and high-severity injury cases were significantly more likely to close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), with AORs of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.21-2.65) and 2.44 (95% CI, 1.54-3.87), respectively.

The most striking finding in our regression model was the magnitude of the effect of an error in clinical judgement. Cases coded with this contributing factor had five times the AOR of closing with payment (compared with no payment) (AOR, 5.01; 95% CI, 3.37-7.45). A clinical judgment call may be difficult to defend when it is ultimately associated with a bad patient outcome. The importance of clinical judgment in our analysis suggests a risk management strategy: clearly and contemporaneously documenting the rationale behind one’s clinical decision-making. This may help make a claim more defensible in the event of an adverse outcome by demonstrating that the clinician was acting reasonably based on the information available at the time. The importance of specifying a rationale for a clinical decision may be especially important in the era of electronic health records (EHRs). EHRs are not structured as chronologically linear charts, which can make it challenging during a trial to retrospectively show what information was available to the physician at the time the clinical decision was made. The importance of clinical judgment also affirms the importance of effective clinical decision support as a patient safety tool.23

More broadly, it is notable that several contributing factors, including errors in clinical judgment (as discussed previously), problems with communication, and issues with the clinical environment, were significantly associated with malpractice cases closing with payment. This demonstrates that systematically examining malpractice claims to determine the underlying contributing factors can generate predictive analytics, as well as suggest risk management and patient safety strategies.

Interdisciplinary collaboration, as a component of systems-based practice, is a core principle of hospital medicine,13 and so we analyzed the involvement of other clinicians in hospitalist claims. Of the five specialties most frequently named in claims with hospitalists, two were surgical services: general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%) and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%). With hospitalists being asked to play an increasing role in the care of surgical patients, they may be providing care to patient populations with whom they have less experience, which could put them at risk of adverse outcomes, leading to malpractice claims.24,25 Hospitalists need to be attuned to the liability risks related to the care of patients requiring surgical management and ensure areas of responsibility are clearly delineated between the hospital medicine and surgical services.26 We also found that hospitalist claims increasingly involve PAs and NPs, likely reflecting their increasing role in providing care on hospitalist services.27,28

A prior analysis of claims rates for hospitalists that covered injury dates from 1997 to 2011 found that hospitalists had a relatively low claims rate, significantly lower than that for other internal medicine physicians.8 In addition to covering an earlier time period, that analysis based its claims rates on data from academic medical centers covered by a single insurer, and physicians at academic medical centers generally have lower claims rates, likely due, at least in part, to their spending a smaller proportion of their time on patient care, compared with nonacademic physicians.29 Another analysis of hospitalist closed claims, which shared some cases with the cohort we analyzed, was performed by The Doctors Company, a commercial liability insurer.7 That analysis astutely emphasized the importance of breakdowns in diagnostic processes as a factor underlying hospitalist claims.

Our study has several limitations. First, although our database of malpractice claims includes approximately 31% of all the claims in the country and includes claims from every state, it may not be nationally representative. Another limitation relates to calculating the claims rates for physicians. Detailed information on the number of years of clinical activity, which is necessary to calculate claims rates, was available for only a subset of our data (8.2% of the hospitalist cases and 11.6% of all cases), so claims rates are based on this subset of our data (among which academic centers are overrepresented). Therefore, the claims rates should be interpreted with caution, especially regarding their application to the community hospital setting. The institutions included in the subset of our data used for determining claims rates were stable over time, so the use of a subset of our data for calculating claims rates reduces the generalizability of our claims rates but should not be a source of bias.

Potentially offsetting strengths of our claims database and study include the availability of unpaid claims (which outnumber paid claims roughly 2:1)11,12; the presence of information on contributing factors and other case characteristics obtained through structured manual review of the cases; and the availability of the specialties of the clinicians involved. These features distinguish the database we used from the NPDB, another national database of malpractice claims, which does not include unpaid claims and which does not include information on contributing factors or physician specialty.

CONCLUSION

First described in 1996, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in modern medical history.18,30 Therefore, an understanding of the malpractice risk of hospitalists is important and can shed light on the patient safety environment in hospitals. Our analysis showed that hospitalist malpractice claims rates remain roughly stable, in contrast to most other specialties, which have seen a fall in malpractice claims rates.17 In addition, unlike a previous analysis,8 we found that claims rates for hospitalists were essentially equal to those of other general internal medicine physicians (not lower, as had been previously reported), and higher than those of the internal medicine subspecialties. Hospitalist claims also have relatively high severity of injury. Potential factors driving these trends include the increasing demand for hospitalists, which results in a higher proportion of less-experienced physicians entering the field, and the expanding clinical scope of hospitalists, which may lead to their managing patients with conditions with which they may be less comfortable. Overall, our analysis suggests that the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable, and therefore, hospitalists should explore opportunities for mitigating liability risk and enhancing patient safety.

1. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.21.2609

2. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assuaged by tort reforms. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1585-1592. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0135

3. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-0694

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807

5. Rothberg MB, Class J, Bishop TF, Friderici J, Kleppel R, Lindenauer PK. The cost of defensive medicine on 3 hospital medicine services. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1867-1868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4649

6. Saint S, Vaughn VM, Chopra V, Fowler KE, Kachalia A. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):26-29. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2800

7. Ranum D, Troxel DB, Diamond R. Hospitalist Closed Claims Study: An Expert Analysis of Medical Malpractice Allegations. The Doctors Company. 2016. https://www.thedoctors.com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/closed-claims-studies/10392_ccs-hospitalist_academic_single-page_version_frr.pdf

8. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

9. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199107253250405

10. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, Zbar BI, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002

11. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa054479

12. Medical Malpractice in America: 2018 CRICO Strategies National CBS Report. CRICO Strategies; 2018.

13. Budnitz T, McKean SC. The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. In: McKean SC, Ross JJ, Dressler DD, Scheurer DB, eds. Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

14. O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.714

15. National Practitioner Data Bank: Public Use Data File. Division of Practitioner Data Banks, Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources & Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; June 30, 2019. Updated August 2020.

16. Sowka MP, ed. NAIC Malpractice Claims, Final Compilation. National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 1980.

17. Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):710-718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0311

18. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

19. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the Society of General Internal Medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

20. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049

21. Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, et al. National trends in admission and in-hospital mortality of patients with heart failure in the United States (2001-2014). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e006955. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.006955

22. Clark AV, LoPresti CM, Smith TI. Trends in inpatient admission comorbidity and electronic health data: implications for resident workload intensity. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):570-572. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2954

23. Gilmartin HM, Liu VX, Burke RE. Annals for hospitalists inpatient notes - The role of hospitalists in the creation of learning healthcare systems. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):HO2-HO3. https://doi.org/10.7326/m19-3873

24. Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.361

25. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00837-3

26. Thompson RE, Pfeifer K, Grant PJ, et al. Hospital medicine and perioperative care: a framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):277-282. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2717

27. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):190-194. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1001

28. Kartha A, Restuccia JD, Burgess JF Jr, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):615-620. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2231

29. Schaffer AC, Babayan A, Yu-Moe CW, Sato L, Einbinder JS. The effect of clinical volume on annual and per-patient encounter medical malpractice claims risk. J Patient Saf. Published online March 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000706

30. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199608153350713

The prospect of facing a medical malpractice claim is a source of apprehension for physicians that affects physician behavior, including leading to defensive medicine.1-3 Overall, annual defensive medicine costs have been estimated at $45.6 billion,4 and surveys of hospitalists indicate that 13.0% to 37.5% of hospitalist healthcare costs involve defensive medicine.5,6 Despite the impact of malpractice concerns on hospitalist practice and the unprecedented growth of the field of hospital medicine, relatively few studies have examined the liability environment surrounding hospitalist practice.7,8 The specific issue of malpractice claims rates faced by hospitalists has received even less attention in the medical literature.8

A better understanding of the contributing factors and other attributes of malpractice claims can help guide patient safety initiatives and inform hospitalists’ level of concern regarding liability. Although most medical errors do not result in a malpractice claim,9,10 the majority of malpractice claims in which there is an indemnity payment involve medical injury due to clinician error.11 Even malpractice claims that do not result in an indemnity payment represent opportunities to identify patient safety and risk management vulnerabilities.12

We used a national malpractice claims database to analyze the characteristics of claims made against hospitalists, including claims rates. In addition to claims rates, we also analyzed the other types of providers named in hospitalist claims given the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to hospital medicine.13,14 To provide context for understanding hospitalist liability data, we present data on other specialties. We also describe a model to predict whether hospitalist malpractice claims will close with an indemnity payment.

METHODS

Data Sources and Elements

This analysis used a repository of malpractice claims maintained by CRICO, the captive malpractice insurer of the Harvard-affiliated medical institutions. This database, the Comparative Benchmarking System, a

Injury severity was based on a widely used scale developed for malpractice claims by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.16 Low injury severity included emotional injury and temporary insignificant injury. Medium injury severity included temporary minor, temporary major, and permanent minor injury. High injury severity included permanent significant injury through death. Because this study used a database assembled for operational and patient safety purposes and was not human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not needed.

Study Cohort

Malpractice claims included formal lawsuits or written requests for compensation for negligent medical care. Ho

Statistical Analysis

Malpractice claims rates were treated as Poisson rates and compared using a Z-test. Malpractice claims rates are expressed as claims per 100 physician-years. Each physician-year represents 1 year of coverage of one physician by the medical malpractice carrier whose data were used. Physician-years represent the duration of time physicians practiced during which they were insured by the malpractice carrier and, as such, could have been subject to a malpractice claim that would have been included in our data. Claims rates are based on the subset of the malpractice claims in the study for which the number of physician-years of coverage is available, representing 8.2% of hospitalist claims and 11.6% of all claims.

Comparisons of the percentages of cases closing with an indemnity payment, as well as the percentages of cases in different allegation type and clinical severity categories, were made using the Fisher exact test. Indemnity payment amounts were inflation-adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Comparisons of indemnity payment amounts between physician specialties were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank sum test given that the distribution of the payment amounts appeared nonnormal; this was confirmed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to predict the binary outcome of whether a hospitalist case would close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), based on the 1,216 hospitalist claims. The predictors used in this regression model were chosen a priori based on hypotheses about what factors drive the likelihood that a case closes with payment. Both the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the predictors are presented. The adjusted model is adjusted for all the other predictors contained in the model. All reported P values are two-sided. The statistical analysis was carried out using JMP Pro version 15 (SAS Institute Inc) and Minitab version 19 (Minitab LLC).

RESULTS

We identified 1,216 hospital medicine malpractice claims from our database. Claims rates were calculated from the subset of our data for which physician-years were available—including 5,140 physician-years encompassing 100 claims, representing 8.2% of all hospitalist claims studied. An additional 18,644 malpractice claims from five other specialties—nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialists, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry—were analyzed to provide context for the hospitalist claims.

The malpractice claims rate for hospitalists was significantly higher than the rate for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001), though they were not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years; P = .93) (Table 1). Compared with emergency medicine physicians, with whom hospitalists are sometimes compared due to both specialties being defined by their site of practice and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships, hospitalists had a significantly lower claims rate (1.95 vs 4.07 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001).

An assessment of the temporal trends in the claims rates, based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period (2014-2018 vs 2009-2013), showed that the claims rate for hospitalists was increasing, but at a rate that did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). In contrast, the claims rates for the five other specialties assessed decreased over time, and the decreases were significant for four of these five other specialties (internal medicine subspecialties, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry).

Multiple claims against a single physician were uncommon in our hospitalist malpractice claims data. Among the 100 claims that were used to calculate the claims rates, one physician was named in 2 claims, and all the other physicians were named in only a single claim. Among all of the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims we analyzed, there were eight physicians who were named in more than 1 claim, seven of whom were named in 2 claims, and one of whom was named in 3 claims.

The median indemnity payment for hospitalist claims was $231,454 (interquartile range [IQR], $100,000-$503,015), similar to the median indemnity payment for neurosurgery ($233,723; IQR, $85,292-$697,872), though significantly greater than the median indemnity payment for the other four specialties studied (Table 2). Among the hospitalist claims, 29.9% resulted in an indemnity payment, not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialties, or neurosurgery, but significantly lower than the rate for emergency medicine (33.8%; P = .011). No

We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the effect of different factors on the likelihood of a hospitalist case closing with an indemnity payment, compared with no payment (Table 3). In the multivariable model, the presence of an error in clinical judgment had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 5.01 (95% CI, 3.37-7.45; P < .001) for a claim closing with payment, the largest effect found. The presence of problems with communication (AOR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.42-2.51; P < .001), the clinical environment (eg, weekend/holiday or clinical busyness; AOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20-2.40; P = .0026), and documentation (AOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.18-2.31; P = .0038) were also positive predictors of claims closing with payment. Greater patient age (per decade) was a negative predictor of the likelihood of a claim closing with payment (AOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.998), though it was of borderline statistical significance (P = .044).

We also assessed multiple clinical attributes of hospitalist malpractice claims, including the major allegation type and injury severity (Appendix Table). Among the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims studied, the most common allegation types were for errors related to medical treatment (n = 482; 39.6%), diagnosis (n = 446; 36.7%), and medications (n = 157; 12.9%). Among the hospitalist claims, 888 (73.0%) involved high-severity injury, and 674 (55.4%) involved the death of the patient. The percentages of cases involving high-severity injury and death were significantly greater for hospitalists, compared with that of the other specialties studied (P < .001 for all pairwise comparisons). Of the six specialties studied, hospital medicine was the only one in which the percentage of cases involving death exceeded 50%.

Hospital medicine is typically team-based, and we evaluated which other services were named in claims with hospital medicine as the primary responsible service. The clinician groups most commonly named in hospitalist claims were nursing (n = 269; 22.1%), followed by emergency medicine (n = 91; 7.5%), general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%), cardiology (n = 49; 4.0%), and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%) (Appendix Figure). During the first 2 years of the study period, no physician assistants (PAs) or nurse practitioners (NPs) were named in hospitalist claims. Over the study period, the proportion of hospitalist cases also naming PAs and NPs increased steadily, reaching 6.9% and 6.2% of claims, respectively, in 2018 (Figure) (P < .001 for NPs and P = .037 for PAs based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period).

DISCUSSION

We found that the average annual claims rate for hospitalists was similar to that for nonhospitalist general internists (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years) but significantly greater than that for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years). Hospitalist claims rates showed a notable temporal trend—a nonsignificant increase—over the study period (2009-2018). This contrasts with the five other specialties studied, all of which had decreasing claims rates, four of which were significant. An analysis of a different national malpractice claims database, the NPDB, found that the rate of paid malpractice claims overall decreased 55.7% during the period 1992-2014, again contrasting with the trend we found for hospitalist claims rates.17

We posit several explanations for why the malpractice claims rate trend for hospitalists has diverged from that of other specialties. There has been a large expansion in the number of hospitalists in the United States.18 With this increasing demand, many young physicians have entered the hospital medicine field. In a survey of general internal medicine physicians conducted by the Society of General Internal Medicine, 73% of hospitalists were aged 25 to 44 years, significantly greater than the 45% in this age range among nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians.19 Hospitalists in their first year of practice have higher mortality rates than more experienced hospitalists.20 Therefore, the relative inexperience of hospitalists, driven by this high demand, could be putting them at increased risk of medical errors and resulting malpractice claims. The higher mortality rate among hospitalists in their first year of practice could be due to a lack of familiarity with the systems of care, such as managing test results and obtaining appropriate consults.20 This possibility suggests that enhanced training and mentorship could be valuable as a strategy to both improve the quality of care and reduce medicolegal risk. The increasing demand for hospitalists could also be affecting the qualification level of physicians entering the field.

Our analysis also showed that the severity of injury in hospitalist claims was greater than that for the other specialties studied. In addition, the percentage of claims involving death was greater for hospitalists than that for the other specialties. The increased acuity of inpatients, compared with that of outpatients—and the trend, at least for some conditions, of increased inpatient acuity over time21,22— could account for the high injury severity seen among hospitalist claims. Given the positive correlation between injury severity and the size of indemnity payments made on malpractice claims,12 the high injury severity seen in hospitalist claims was very likely a driver of the high indemnity payments observed among the hospitalist claims.

The relationship between injury severity and financial outcomes is supported by the results of our multivariable regression model (Table 3). Compared with medium-severity injury claims, both death and high-severity injury cases were significantly more likely to close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), with AORs of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.21-2.65) and 2.44 (95% CI, 1.54-3.87), respectively.

The most striking finding in our regression model was the magnitude of the effect of an error in clinical judgement. Cases coded with this contributing factor had five times the AOR of closing with payment (compared with no payment) (AOR, 5.01; 95% CI, 3.37-7.45). A clinical judgment call may be difficult to defend when it is ultimately associated with a bad patient outcome. The importance of clinical judgment in our analysis suggests a risk management strategy: clearly and contemporaneously documenting the rationale behind one’s clinical decision-making. This may help make a claim more defensible in the event of an adverse outcome by demonstrating that the clinician was acting reasonably based on the information available at the time. The importance of specifying a rationale for a clinical decision may be especially important in the era of electronic health records (EHRs). EHRs are not structured as chronologically linear charts, which can make it challenging during a trial to retrospectively show what information was available to the physician at the time the clinical decision was made. The importance of clinical judgment also affirms the importance of effective clinical decision support as a patient safety tool.23

More broadly, it is notable that several contributing factors, including errors in clinical judgment (as discussed previously), problems with communication, and issues with the clinical environment, were significantly associated with malpractice cases closing with payment. This demonstrates that systematically examining malpractice claims to determine the underlying contributing factors can generate predictive analytics, as well as suggest risk management and patient safety strategies.

Interdisciplinary collaboration, as a component of systems-based practice, is a core principle of hospital medicine,13 and so we analyzed the involvement of other clinicians in hospitalist claims. Of the five specialties most frequently named in claims with hospitalists, two were surgical services: general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%) and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%). With hospitalists being asked to play an increasing role in the care of surgical patients, they may be providing care to patient populations with whom they have less experience, which could put them at risk of adverse outcomes, leading to malpractice claims.24,25 Hospitalists need to be attuned to the liability risks related to the care of patients requiring surgical management and ensure areas of responsibility are clearly delineated between the hospital medicine and surgical services.26 We also found that hospitalist claims increasingly involve PAs and NPs, likely reflecting their increasing role in providing care on hospitalist services.27,28

A prior analysis of claims rates for hospitalists that covered injury dates from 1997 to 2011 found that hospitalists had a relatively low claims rate, significantly lower than that for other internal medicine physicians.8 In addition to covering an earlier time period, that analysis based its claims rates on data from academic medical centers covered by a single insurer, and physicians at academic medical centers generally have lower claims rates, likely due, at least in part, to their spending a smaller proportion of their time on patient care, compared with nonacademic physicians.29 Another analysis of hospitalist closed claims, which shared some cases with the cohort we analyzed, was performed by The Doctors Company, a commercial liability insurer.7 That analysis astutely emphasized the importance of breakdowns in diagnostic processes as a factor underlying hospitalist claims.

Our study has several limitations. First, although our database of malpractice claims includes approximately 31% of all the claims in the country and includes claims from every state, it may not be nationally representative. Another limitation relates to calculating the claims rates for physicians. Detailed information on the number of years of clinical activity, which is necessary to calculate claims rates, was available for only a subset of our data (8.2% of the hospitalist cases and 11.6% of all cases), so claims rates are based on this subset of our data (among which academic centers are overrepresented). Therefore, the claims rates should be interpreted with caution, especially regarding their application to the community hospital setting. The institutions included in the subset of our data used for determining claims rates were stable over time, so the use of a subset of our data for calculating claims rates reduces the generalizability of our claims rates but should not be a source of bias.

Potentially offsetting strengths of our claims database and study include the availability of unpaid claims (which outnumber paid claims roughly 2:1)11,12; the presence of information on contributing factors and other case characteristics obtained through structured manual review of the cases; and the availability of the specialties of the clinicians involved. These features distinguish the database we used from the NPDB, another national database of malpractice claims, which does not include unpaid claims and which does not include information on contributing factors or physician specialty.

CONCLUSION

First described in 1996, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in modern medical history.18,30 Therefore, an understanding of the malpractice risk of hospitalists is important and can shed light on the patient safety environment in hospitals. Our analysis showed that hospitalist malpractice claims rates remain roughly stable, in contrast to most other specialties, which have seen a fall in malpractice claims rates.17 In addition, unlike a previous analysis,8 we found that claims rates for hospitalists were essentially equal to those of other general internal medicine physicians (not lower, as had been previously reported), and higher than those of the internal medicine subspecialties. Hospitalist claims also have relatively high severity of injury. Potential factors driving these trends include the increasing demand for hospitalists, which results in a higher proportion of less-experienced physicians entering the field, and the expanding clinical scope of hospitalists, which may lead to their managing patients with conditions with which they may be less comfortable. Overall, our analysis suggests that the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable, and therefore, hospitalists should explore opportunities for mitigating liability risk and enhancing patient safety.

The prospect of facing a medical malpractice claim is a source of apprehension for physicians that affects physician behavior, including leading to defensive medicine.1-3 Overall, annual defensive medicine costs have been estimated at $45.6 billion,4 and surveys of hospitalists indicate that 13.0% to 37.5% of hospitalist healthcare costs involve defensive medicine.5,6 Despite the impact of malpractice concerns on hospitalist practice and the unprecedented growth of the field of hospital medicine, relatively few studies have examined the liability environment surrounding hospitalist practice.7,8 The specific issue of malpractice claims rates faced by hospitalists has received even less attention in the medical literature.8

A better understanding of the contributing factors and other attributes of malpractice claims can help guide patient safety initiatives and inform hospitalists’ level of concern regarding liability. Although most medical errors do not result in a malpractice claim,9,10 the majority of malpractice claims in which there is an indemnity payment involve medical injury due to clinician error.11 Even malpractice claims that do not result in an indemnity payment represent opportunities to identify patient safety and risk management vulnerabilities.12

We used a national malpractice claims database to analyze the characteristics of claims made against hospitalists, including claims rates. In addition to claims rates, we also analyzed the other types of providers named in hospitalist claims given the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to hospital medicine.13,14 To provide context for understanding hospitalist liability data, we present data on other specialties. We also describe a model to predict whether hospitalist malpractice claims will close with an indemnity payment.

METHODS

Data Sources and Elements

This analysis used a repository of malpractice claims maintained by CRICO, the captive malpractice insurer of the Harvard-affiliated medical institutions. This database, the Comparative Benchmarking System, a

Injury severity was based on a widely used scale developed for malpractice claims by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.16 Low injury severity included emotional injury and temporary insignificant injury. Medium injury severity included temporary minor, temporary major, and permanent minor injury. High injury severity included permanent significant injury through death. Because this study used a database assembled for operational and patient safety purposes and was not human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not needed.

Study Cohort

Malpractice claims included formal lawsuits or written requests for compensation for negligent medical care. Ho

Statistical Analysis

Malpractice claims rates were treated as Poisson rates and compared using a Z-test. Malpractice claims rates are expressed as claims per 100 physician-years. Each physician-year represents 1 year of coverage of one physician by the medical malpractice carrier whose data were used. Physician-years represent the duration of time physicians practiced during which they were insured by the malpractice carrier and, as such, could have been subject to a malpractice claim that would have been included in our data. Claims rates are based on the subset of the malpractice claims in the study for which the number of physician-years of coverage is available, representing 8.2% of hospitalist claims and 11.6% of all claims.

Comparisons of the percentages of cases closing with an indemnity payment, as well as the percentages of cases in different allegation type and clinical severity categories, were made using the Fisher exact test. Indemnity payment amounts were inflation-adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Comparisons of indemnity payment amounts between physician specialties were carried out using the Wilcoxon rank sum test given that the distribution of the payment amounts appeared nonnormal; this was confirmed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to predict the binary outcome of whether a hospitalist case would close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), based on the 1,216 hospitalist claims. The predictors used in this regression model were chosen a priori based on hypotheses about what factors drive the likelihood that a case closes with payment. Both the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the predictors are presented. The adjusted model is adjusted for all the other predictors contained in the model. All reported P values are two-sided. The statistical analysis was carried out using JMP Pro version 15 (SAS Institute Inc) and Minitab version 19 (Minitab LLC).

RESULTS

We identified 1,216 hospital medicine malpractice claims from our database. Claims rates were calculated from the subset of our data for which physician-years were available—including 5,140 physician-years encompassing 100 claims, representing 8.2% of all hospitalist claims studied. An additional 18,644 malpractice claims from five other specialties—nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialists, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry—were analyzed to provide context for the hospitalist claims.

The malpractice claims rate for hospitalists was significantly higher than the rate for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001), though they were not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years; P = .93) (Table 1). Compared with emergency medicine physicians, with whom hospitalists are sometimes compared due to both specialties being defined by their site of practice and the absence of longitudinal patient relationships, hospitalists had a significantly lower claims rate (1.95 vs 4.07 claims per 100 physician-years; P < .001).

An assessment of the temporal trends in the claims rates, based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period (2014-2018 vs 2009-2013), showed that the claims rate for hospitalists was increasing, but at a rate that did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). In contrast, the claims rates for the five other specialties assessed decreased over time, and the decreases were significant for four of these five other specialties (internal medicine subspecialties, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and psychiatry).

Multiple claims against a single physician were uncommon in our hospitalist malpractice claims data. Among the 100 claims that were used to calculate the claims rates, one physician was named in 2 claims, and all the other physicians were named in only a single claim. Among all of the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims we analyzed, there were eight physicians who were named in more than 1 claim, seven of whom were named in 2 claims, and one of whom was named in 3 claims.

The median indemnity payment for hospitalist claims was $231,454 (interquartile range [IQR], $100,000-$503,015), similar to the median indemnity payment for neurosurgery ($233,723; IQR, $85,292-$697,872), though significantly greater than the median indemnity payment for the other four specialties studied (Table 2). Among the hospitalist claims, 29.9% resulted in an indemnity payment, not significantly different from the rate for nonhospitalist general internal medicine, internal medicine subspecialties, or neurosurgery, but significantly lower than the rate for emergency medicine (33.8%; P = .011). No

We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the effect of different factors on the likelihood of a hospitalist case closing with an indemnity payment, compared with no payment (Table 3). In the multivariable model, the presence of an error in clinical judgment had an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 5.01 (95% CI, 3.37-7.45; P < .001) for a claim closing with payment, the largest effect found. The presence of problems with communication (AOR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.42-2.51; P < .001), the clinical environment (eg, weekend/holiday or clinical busyness; AOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20-2.40; P = .0026), and documentation (AOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.18-2.31; P = .0038) were also positive predictors of claims closing with payment. Greater patient age (per decade) was a negative predictor of the likelihood of a claim closing with payment (AOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.998), though it was of borderline statistical significance (P = .044).

We also assessed multiple clinical attributes of hospitalist malpractice claims, including the major allegation type and injury severity (Appendix Table). Among the 1,216 hospitalist malpractice claims studied, the most common allegation types were for errors related to medical treatment (n = 482; 39.6%), diagnosis (n = 446; 36.7%), and medications (n = 157; 12.9%). Among the hospitalist claims, 888 (73.0%) involved high-severity injury, and 674 (55.4%) involved the death of the patient. The percentages of cases involving high-severity injury and death were significantly greater for hospitalists, compared with that of the other specialties studied (P < .001 for all pairwise comparisons). Of the six specialties studied, hospital medicine was the only one in which the percentage of cases involving death exceeded 50%.

Hospital medicine is typically team-based, and we evaluated which other services were named in claims with hospital medicine as the primary responsible service. The clinician groups most commonly named in hospitalist claims were nursing (n = 269; 22.1%), followed by emergency medicine (n = 91; 7.5%), general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%), cardiology (n = 49; 4.0%), and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%) (Appendix Figure). During the first 2 years of the study period, no physician assistants (PAs) or nurse practitioners (NPs) were named in hospitalist claims. Over the study period, the proportion of hospitalist cases also naming PAs and NPs increased steadily, reaching 6.9% and 6.2% of claims, respectively, in 2018 (Figure) (P < .001 for NPs and P = .037 for PAs based on a comparison between the two halves of the study period).

DISCUSSION

We found that the average annual claims rate for hospitalists was similar to that for nonhospitalist general internists (1.95 vs 1.92 claims per 100 physician-years) but significantly greater than that for internal medicine subspecialists (1.95 vs 1.30 claims per 100 physician-years). Hospitalist claims rates showed a notable temporal trend—a nonsignificant increase—over the study period (2009-2018). This contrasts with the five other specialties studied, all of which had decreasing claims rates, four of which were significant. An analysis of a different national malpractice claims database, the NPDB, found that the rate of paid malpractice claims overall decreased 55.7% during the period 1992-2014, again contrasting with the trend we found for hospitalist claims rates.17

We posit several explanations for why the malpractice claims rate trend for hospitalists has diverged from that of other specialties. There has been a large expansion in the number of hospitalists in the United States.18 With this increasing demand, many young physicians have entered the hospital medicine field. In a survey of general internal medicine physicians conducted by the Society of General Internal Medicine, 73% of hospitalists were aged 25 to 44 years, significantly greater than the 45% in this age range among nonhospitalist general internal medicine physicians.19 Hospitalists in their first year of practice have higher mortality rates than more experienced hospitalists.20 Therefore, the relative inexperience of hospitalists, driven by this high demand, could be putting them at increased risk of medical errors and resulting malpractice claims. The higher mortality rate among hospitalists in their first year of practice could be due to a lack of familiarity with the systems of care, such as managing test results and obtaining appropriate consults.20 This possibility suggests that enhanced training and mentorship could be valuable as a strategy to both improve the quality of care and reduce medicolegal risk. The increasing demand for hospitalists could also be affecting the qualification level of physicians entering the field.

Our analysis also showed that the severity of injury in hospitalist claims was greater than that for the other specialties studied. In addition, the percentage of claims involving death was greater for hospitalists than that for the other specialties. The increased acuity of inpatients, compared with that of outpatients—and the trend, at least for some conditions, of increased inpatient acuity over time21,22— could account for the high injury severity seen among hospitalist claims. Given the positive correlation between injury severity and the size of indemnity payments made on malpractice claims,12 the high injury severity seen in hospitalist claims was very likely a driver of the high indemnity payments observed among the hospitalist claims.

The relationship between injury severity and financial outcomes is supported by the results of our multivariable regression model (Table 3). Compared with medium-severity injury claims, both death and high-severity injury cases were significantly more likely to close with an indemnity payment (compared with no payment), with AORs of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.21-2.65) and 2.44 (95% CI, 1.54-3.87), respectively.

The most striking finding in our regression model was the magnitude of the effect of an error in clinical judgement. Cases coded with this contributing factor had five times the AOR of closing with payment (compared with no payment) (AOR, 5.01; 95% CI, 3.37-7.45). A clinical judgment call may be difficult to defend when it is ultimately associated with a bad patient outcome. The importance of clinical judgment in our analysis suggests a risk management strategy: clearly and contemporaneously documenting the rationale behind one’s clinical decision-making. This may help make a claim more defensible in the event of an adverse outcome by demonstrating that the clinician was acting reasonably based on the information available at the time. The importance of specifying a rationale for a clinical decision may be especially important in the era of electronic health records (EHRs). EHRs are not structured as chronologically linear charts, which can make it challenging during a trial to retrospectively show what information was available to the physician at the time the clinical decision was made. The importance of clinical judgment also affirms the importance of effective clinical decision support as a patient safety tool.23

More broadly, it is notable that several contributing factors, including errors in clinical judgment (as discussed previously), problems with communication, and issues with the clinical environment, were significantly associated with malpractice cases closing with payment. This demonstrates that systematically examining malpractice claims to determine the underlying contributing factors can generate predictive analytics, as well as suggest risk management and patient safety strategies.

Interdisciplinary collaboration, as a component of systems-based practice, is a core principle of hospital medicine,13 and so we analyzed the involvement of other clinicians in hospitalist claims. Of the five specialties most frequently named in claims with hospitalists, two were surgical services: general surgery (n = 51; 4.2%) and orthopedic surgery (n = 46; 3.8%). With hospitalists being asked to play an increasing role in the care of surgical patients, they may be providing care to patient populations with whom they have less experience, which could put them at risk of adverse outcomes, leading to malpractice claims.24,25 Hospitalists need to be attuned to the liability risks related to the care of patients requiring surgical management and ensure areas of responsibility are clearly delineated between the hospital medicine and surgical services.26 We also found that hospitalist claims increasingly involve PAs and NPs, likely reflecting their increasing role in providing care on hospitalist services.27,28

A prior analysis of claims rates for hospitalists that covered injury dates from 1997 to 2011 found that hospitalists had a relatively low claims rate, significantly lower than that for other internal medicine physicians.8 In addition to covering an earlier time period, that analysis based its claims rates on data from academic medical centers covered by a single insurer, and physicians at academic medical centers generally have lower claims rates, likely due, at least in part, to their spending a smaller proportion of their time on patient care, compared with nonacademic physicians.29 Another analysis of hospitalist closed claims, which shared some cases with the cohort we analyzed, was performed by The Doctors Company, a commercial liability insurer.7 That analysis astutely emphasized the importance of breakdowns in diagnostic processes as a factor underlying hospitalist claims.

Our study has several limitations. First, although our database of malpractice claims includes approximately 31% of all the claims in the country and includes claims from every state, it may not be nationally representative. Another limitation relates to calculating the claims rates for physicians. Detailed information on the number of years of clinical activity, which is necessary to calculate claims rates, was available for only a subset of our data (8.2% of the hospitalist cases and 11.6% of all cases), so claims rates are based on this subset of our data (among which academic centers are overrepresented). Therefore, the claims rates should be interpreted with caution, especially regarding their application to the community hospital setting. The institutions included in the subset of our data used for determining claims rates were stable over time, so the use of a subset of our data for calculating claims rates reduces the generalizability of our claims rates but should not be a source of bias.

Potentially offsetting strengths of our claims database and study include the availability of unpaid claims (which outnumber paid claims roughly 2:1)11,12; the presence of information on contributing factors and other case characteristics obtained through structured manual review of the cases; and the availability of the specialties of the clinicians involved. These features distinguish the database we used from the NPDB, another national database of malpractice claims, which does not include unpaid claims and which does not include information on contributing factors or physician specialty.

CONCLUSION

First described in 1996, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in modern medical history.18,30 Therefore, an understanding of the malpractice risk of hospitalists is important and can shed light on the patient safety environment in hospitals. Our analysis showed that hospitalist malpractice claims rates remain roughly stable, in contrast to most other specialties, which have seen a fall in malpractice claims rates.17 In addition, unlike a previous analysis,8 we found that claims rates for hospitalists were essentially equal to those of other general internal medicine physicians (not lower, as had been previously reported), and higher than those of the internal medicine subspecialties. Hospitalist claims also have relatively high severity of injury. Potential factors driving these trends include the increasing demand for hospitalists, which results in a higher proportion of less-experienced physicians entering the field, and the expanding clinical scope of hospitalists, which may lead to their managing patients with conditions with which they may be less comfortable. Overall, our analysis suggests that the malpractice environment for hospitalists is becoming less favorable, and therefore, hospitalists should explore opportunities for mitigating liability risk and enhancing patient safety.

1. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.21.2609

2. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assuaged by tort reforms. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1585-1592. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0135

3. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-0694

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807

5. Rothberg MB, Class J, Bishop TF, Friderici J, Kleppel R, Lindenauer PK. The cost of defensive medicine on 3 hospital medicine services. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1867-1868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4649

6. Saint S, Vaughn VM, Chopra V, Fowler KE, Kachalia A. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):26-29. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2800

7. Ranum D, Troxel DB, Diamond R. Hospitalist Closed Claims Study: An Expert Analysis of Medical Malpractice Allegations. The Doctors Company. 2016. https://www.thedoctors.com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/closed-claims-studies/10392_ccs-hospitalist_academic_single-page_version_frr.pdf

8. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

9. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199107253250405

10. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, Zbar BI, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002

11. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa054479

12. Medical Malpractice in America: 2018 CRICO Strategies National CBS Report. CRICO Strategies; 2018.

13. Budnitz T, McKean SC. The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. In: McKean SC, Ross JJ, Dressler DD, Scheurer DB, eds. Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

14. O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.714

15. National Practitioner Data Bank: Public Use Data File. Division of Practitioner Data Banks, Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources & Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; June 30, 2019. Updated August 2020.

16. Sowka MP, ed. NAIC Malpractice Claims, Final Compilation. National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 1980.

17. Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):710-718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0311

18. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

19. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the Society of General Internal Medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

20. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049

21. Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, et al. National trends in admission and in-hospital mortality of patients with heart failure in the United States (2001-2014). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e006955. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.006955

22. Clark AV, LoPresti CM, Smith TI. Trends in inpatient admission comorbidity and electronic health data: implications for resident workload intensity. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):570-572. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2954

23. Gilmartin HM, Liu VX, Burke RE. Annals for hospitalists inpatient notes - The role of hospitalists in the creation of learning healthcare systems. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):HO2-HO3. https://doi.org/10.7326/m19-3873

24. Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.361

25. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00837-3

26. Thompson RE, Pfeifer K, Grant PJ, et al. Hospital medicine and perioperative care: a framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):277-282. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2717

27. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):190-194. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1001

28. Kartha A, Restuccia JD, Burgess JF Jr, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):615-620. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2231

29. Schaffer AC, Babayan A, Yu-Moe CW, Sato L, Einbinder JS. The effect of clinical volume on annual and per-patient encounter medical malpractice claims risk. J Patient Saf. Published online March 23, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/pts.0000000000000706

30. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199608153350713

1. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.21.2609

2. Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assuaged by tort reforms. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1585-1592. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0135

3. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-0694

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0807

5. Rothberg MB, Class J, Bishop TF, Friderici J, Kleppel R, Lindenauer PK. The cost of defensive medicine on 3 hospital medicine services. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1867-1868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4649

6. Saint S, Vaughn VM, Chopra V, Fowler KE, Kachalia A. Perception of resources spent on defensive medicine and history of being sued among hospitalists: results from a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):26-29. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2800

7. Ranum D, Troxel DB, Diamond R. Hospitalist Closed Claims Study: An Expert Analysis of Medical Malpractice Allegations. The Doctors Company. 2016. https://www.thedoctors.com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/closed-claims-studies/10392_ccs-hospitalist_academic_single-page_version_frr.pdf

8. Schaffer AC, Puopolo AL, Raman S, Kachalia A. Liability impact of the hospitalist model of care. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):750-755. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2244

9. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199107253250405

10. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, Zbar BI, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002

11. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa054479

12. Medical Malpractice in America: 2018 CRICO Strategies National CBS Report. CRICO Strategies; 2018.

13. Budnitz T, McKean SC. The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. In: McKean SC, Ross JJ, Dressler DD, Scheurer DB, eds. Principles and Practice of Hospital Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

14. O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.714

15. National Practitioner Data Bank: Public Use Data File. Division of Practitioner Data Banks, Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources & Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; June 30, 2019. Updated August 2020.

16. Sowka MP, ed. NAIC Malpractice Claims, Final Compilation. National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 1980.

17. Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among US physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):710-718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0311

18. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1607958

19. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the Society of General Internal Medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

20. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049

21. Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, et al. National trends in admission and in-hospital mortality of patients with heart failure in the United States (2001-2014). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e006955. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.006955

22. Clark AV, LoPresti CM, Smith TI. Trends in inpatient admission comorbidity and electronic health data: implications for resident workload intensity. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):570-572. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2954

23. Gilmartin HM, Liu VX, Burke RE. Annals for hospitalists inpatient notes - The role of hospitalists in the creation of learning healthcare systems. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):HO2-HO3. https://doi.org/10.7326/m19-3873

24. Siegal EM. Just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):398-402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.361

25. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001;111(3):247-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00837-3

26. Thompson RE, Pfeifer K, Grant PJ, et al. Hospital medicine and perioperative care: a framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):277-282. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2717