User login

An otherwise healthy 1-month-old female presents with lesions on the face, scalp, and chest

A potassium hydroxide preparation (KOH) from skin scrapings from the scalp lesions demonstrated no fungal elements. Further laboratory work up revealed a normal blood cell count, normal liver enzymes, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of less than 1:80, a positive anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type B (SSB) antibody but negative anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type A (SSA) antibody and anti-U1RNP antibody. An electrocardiogram revealed no abnormalities. Liver function tests were normal. The complete blood count showed mild thrombocytopenia. Given the typical skin lesions and the positive SSB test and associated thrombocytopenia, the baby was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus.

Because of the diagnosis of neonatal lupus the mother was also tested and was found to have an elevated ANA of 1:640, positive SSB and antiphospholipid antibodies. The mother was healthy and her review of systems was negative for any collagen vascular disease–related symptoms.

Discussion

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is a rare form of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) believed to be caused by transplacental transfer of anti-Ro (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen A, SSA), or, less commonly, anti-La (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen B, SSB) from mothers who are positive for these antibodies. Approximately 95% of NLE is associated with maternal anti-SSA; of these cases, 40% are also associated with maternal anti-SSB.1 Only about 2% of children of mothers who have anti-SSA or anti-SSB develop NLE, a finding that has led some researchers to postulate that maternal factors, fetal genetic factors, and environmental factors determine which children of anti-SSA or SSB positive mothers develop NLE.

A recent review found no association between the development of NLE and fetal birth weight, prematurity, or age.3 Over half of mothers of children who develop NLE are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis of the neonate,3 though many become symptomatic in following years. Of mothers who are symptomatic, SLE and undifferentiated autoimmune syndrome are the most common diagnoses, though NLE has been rarely reported in the offspring of mothers with Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.4,5

Fetal genetics are not an absolute determinant of development of NLE, as discordance in the development of NLE in twins has been reported. However, certain genetic relationships have been established. Fetal mutations in tumor necrosis factor–alpha appear to increase the likelihood of cutaneous manifestations. Mutations in transforming growth factor beta appear to increase the likelihood of cardiac manifestations, and experiments in cultured mouse cardiocytes have shown anti-SSB antibodies to impair macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in the developing fetal heart. These observations taken together suggest a fibroblast-mediated response to unphagocytosed cardiocyte debris may account for conduction abnormalities in neonates with NLE-induced heart block.6

Cutaneous disease in NLE is possible at birth, but more skin findings develop upon exposure to the sun. Nearly 80% of neonates affected by NLE develop cutaneous manifestations in the first few months of life. The head, neck, and extensor surfaces of the arms are most commonly affected, presumably because they are most likely to be exposed to the sun. Erythematous, annular, or discoid lesions are most common, and periorbital erythema with or without scale (“raccoon eyes”) should prompt consideration of NLE. However, annular, or discoid lesions are sometimes not present in NLE; telangiectasias, bullae, atrophic divots (“ice-pick scars”) or ulcerations may be seen instead. Lesions in the genital area have been described in fewer than 5% of patients with NLE.

The differential diagnosis of annular, scaly lesions in neonates includes annular erythema of infancy, tinea corporis, and seborrheic dermatitis. Annular erythema of infancy is a rare skin condition characterized by a cyclical eruption of erythematous annular lesions with minimal scaling which resolve spontaneously within a few weeks to months without leaving scaring or pigment changes. There is no treatment needed as the lesions self-resolve.7 Acute urticaria can sometimes appear similar to NLE but these are not scaly and also the lesions will disappear within 24-36 hours, compared with NLE lesions, which may take weeks to months to go away. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition seen in newborns with in the first few weeks of life and can present as scaly annular erythematous plaques on the face, scalp, torso, and the diaper area. Seborrheic dermatitis usually responds well to a combination of an antiyeast cream and a low-potency topical corticosteroid medication.

When NLE is suspected, diagnostic testing for lupus antibodies (anti-SSA, anti-SSB, and anti-U1RNP) in both maternal and neonatal serum should be undertaken. The presence of a characteristic rash plus maternal or neonatal antibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis. If the rash is less characteristic, a biopsy showing an interface dermatitis can help solidify the diagnosis. Neonates with cutaneous manifestations of lupus may also have systemic disease. The most common and serious complication is heart block, whose pathophysiology is described above. Neonates with evidence of first-, second-, or third-degree heart block should be referred to a pediatric cardiologist for careful monitoring and management. Hepatic involvement has been reported, but is usually mild. Hematologic abnormalities have also been described that include anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, which resolve by 9 months of age. Central nervous system involvement may rarely occur. The mainstay of treatment for the rash in NLE is diligent sun avoidance and sun protection. Topical corticosteroids may be used, but are not needed as the rash typically resolves by 9 months to 1 year without treatment. Mothers who have one child with NLE should be advised that they are more likely to have another with NLE – the risk is as high as 30%-40% in the second child. Hydroxychloroquine taken during subsequent pregnancies can reduce the incidence of cardiac complications,8 as can the so-called “triple therapy” of plasmapheresis, steroids, and IVIg.9

The cutaneous manifestations of NLE are usually self-limiting. However, they can serve as important clues that can prompt diagnosis of SLE in the mother, investigation of cardiac complications in the infant, and appropriate preventative care in future pregnancies.

Dr. Matiz is with the department of dermatology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. Moretti D et al. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1508-12.

2. Buyon JP et al. Nature Clin Prac Rheum. 2009;5(3):139-48.

3. Li Y-Q et al. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):761-7.

4. Rivera TL et al. Annals Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):828-35.

5. Li L et al. Zhonghua er ke za zhi 2011;49(2):146-50.

6. Izmirly PM et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1641-5.

7. Toledo-Alberola F and Betlloch-Mas I. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010 Jul;101(6):473-84.

8. Izmirly PM et al. Circulation. 2012;126(1):76-82.

9. Martinez-Sanchez N et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(5):423-8.

A potassium hydroxide preparation (KOH) from skin scrapings from the scalp lesions demonstrated no fungal elements. Further laboratory work up revealed a normal blood cell count, normal liver enzymes, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of less than 1:80, a positive anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type B (SSB) antibody but negative anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type A (SSA) antibody and anti-U1RNP antibody. An electrocardiogram revealed no abnormalities. Liver function tests were normal. The complete blood count showed mild thrombocytopenia. Given the typical skin lesions and the positive SSB test and associated thrombocytopenia, the baby was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus.

Because of the diagnosis of neonatal lupus the mother was also tested and was found to have an elevated ANA of 1:640, positive SSB and antiphospholipid antibodies. The mother was healthy and her review of systems was negative for any collagen vascular disease–related symptoms.

Discussion

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is a rare form of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) believed to be caused by transplacental transfer of anti-Ro (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen A, SSA), or, less commonly, anti-La (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen B, SSB) from mothers who are positive for these antibodies. Approximately 95% of NLE is associated with maternal anti-SSA; of these cases, 40% are also associated with maternal anti-SSB.1 Only about 2% of children of mothers who have anti-SSA or anti-SSB develop NLE, a finding that has led some researchers to postulate that maternal factors, fetal genetic factors, and environmental factors determine which children of anti-SSA or SSB positive mothers develop NLE.

A recent review found no association between the development of NLE and fetal birth weight, prematurity, or age.3 Over half of mothers of children who develop NLE are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis of the neonate,3 though many become symptomatic in following years. Of mothers who are symptomatic, SLE and undifferentiated autoimmune syndrome are the most common diagnoses, though NLE has been rarely reported in the offspring of mothers with Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.4,5

Fetal genetics are not an absolute determinant of development of NLE, as discordance in the development of NLE in twins has been reported. However, certain genetic relationships have been established. Fetal mutations in tumor necrosis factor–alpha appear to increase the likelihood of cutaneous manifestations. Mutations in transforming growth factor beta appear to increase the likelihood of cardiac manifestations, and experiments in cultured mouse cardiocytes have shown anti-SSB antibodies to impair macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in the developing fetal heart. These observations taken together suggest a fibroblast-mediated response to unphagocytosed cardiocyte debris may account for conduction abnormalities in neonates with NLE-induced heart block.6

Cutaneous disease in NLE is possible at birth, but more skin findings develop upon exposure to the sun. Nearly 80% of neonates affected by NLE develop cutaneous manifestations in the first few months of life. The head, neck, and extensor surfaces of the arms are most commonly affected, presumably because they are most likely to be exposed to the sun. Erythematous, annular, or discoid lesions are most common, and periorbital erythema with or without scale (“raccoon eyes”) should prompt consideration of NLE. However, annular, or discoid lesions are sometimes not present in NLE; telangiectasias, bullae, atrophic divots (“ice-pick scars”) or ulcerations may be seen instead. Lesions in the genital area have been described in fewer than 5% of patients with NLE.

The differential diagnosis of annular, scaly lesions in neonates includes annular erythema of infancy, tinea corporis, and seborrheic dermatitis. Annular erythema of infancy is a rare skin condition characterized by a cyclical eruption of erythematous annular lesions with minimal scaling which resolve spontaneously within a few weeks to months without leaving scaring or pigment changes. There is no treatment needed as the lesions self-resolve.7 Acute urticaria can sometimes appear similar to NLE but these are not scaly and also the lesions will disappear within 24-36 hours, compared with NLE lesions, which may take weeks to months to go away. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition seen in newborns with in the first few weeks of life and can present as scaly annular erythematous plaques on the face, scalp, torso, and the diaper area. Seborrheic dermatitis usually responds well to a combination of an antiyeast cream and a low-potency topical corticosteroid medication.

When NLE is suspected, diagnostic testing for lupus antibodies (anti-SSA, anti-SSB, and anti-U1RNP) in both maternal and neonatal serum should be undertaken. The presence of a characteristic rash plus maternal or neonatal antibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis. If the rash is less characteristic, a biopsy showing an interface dermatitis can help solidify the diagnosis. Neonates with cutaneous manifestations of lupus may also have systemic disease. The most common and serious complication is heart block, whose pathophysiology is described above. Neonates with evidence of first-, second-, or third-degree heart block should be referred to a pediatric cardiologist for careful monitoring and management. Hepatic involvement has been reported, but is usually mild. Hematologic abnormalities have also been described that include anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, which resolve by 9 months of age. Central nervous system involvement may rarely occur. The mainstay of treatment for the rash in NLE is diligent sun avoidance and sun protection. Topical corticosteroids may be used, but are not needed as the rash typically resolves by 9 months to 1 year without treatment. Mothers who have one child with NLE should be advised that they are more likely to have another with NLE – the risk is as high as 30%-40% in the second child. Hydroxychloroquine taken during subsequent pregnancies can reduce the incidence of cardiac complications,8 as can the so-called “triple therapy” of plasmapheresis, steroids, and IVIg.9

The cutaneous manifestations of NLE are usually self-limiting. However, they can serve as important clues that can prompt diagnosis of SLE in the mother, investigation of cardiac complications in the infant, and appropriate preventative care in future pregnancies.

Dr. Matiz is with the department of dermatology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. Moretti D et al. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1508-12.

2. Buyon JP et al. Nature Clin Prac Rheum. 2009;5(3):139-48.

3. Li Y-Q et al. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):761-7.

4. Rivera TL et al. Annals Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):828-35.

5. Li L et al. Zhonghua er ke za zhi 2011;49(2):146-50.

6. Izmirly PM et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1641-5.

7. Toledo-Alberola F and Betlloch-Mas I. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010 Jul;101(6):473-84.

8. Izmirly PM et al. Circulation. 2012;126(1):76-82.

9. Martinez-Sanchez N et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(5):423-8.

A potassium hydroxide preparation (KOH) from skin scrapings from the scalp lesions demonstrated no fungal elements. Further laboratory work up revealed a normal blood cell count, normal liver enzymes, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of less than 1:80, a positive anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type B (SSB) antibody but negative anti–Sjögren’s syndrome type A (SSA) antibody and anti-U1RNP antibody. An electrocardiogram revealed no abnormalities. Liver function tests were normal. The complete blood count showed mild thrombocytopenia. Given the typical skin lesions and the positive SSB test and associated thrombocytopenia, the baby was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus.

Because of the diagnosis of neonatal lupus the mother was also tested and was found to have an elevated ANA of 1:640, positive SSB and antiphospholipid antibodies. The mother was healthy and her review of systems was negative for any collagen vascular disease–related symptoms.

Discussion

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is a rare form of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) believed to be caused by transplacental transfer of anti-Ro (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen A, SSA), or, less commonly, anti-La (Sjögren’s syndrome antigen B, SSB) from mothers who are positive for these antibodies. Approximately 95% of NLE is associated with maternal anti-SSA; of these cases, 40% are also associated with maternal anti-SSB.1 Only about 2% of children of mothers who have anti-SSA or anti-SSB develop NLE, a finding that has led some researchers to postulate that maternal factors, fetal genetic factors, and environmental factors determine which children of anti-SSA or SSB positive mothers develop NLE.

A recent review found no association between the development of NLE and fetal birth weight, prematurity, or age.3 Over half of mothers of children who develop NLE are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis of the neonate,3 though many become symptomatic in following years. Of mothers who are symptomatic, SLE and undifferentiated autoimmune syndrome are the most common diagnoses, though NLE has been rarely reported in the offspring of mothers with Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.4,5

Fetal genetics are not an absolute determinant of development of NLE, as discordance in the development of NLE in twins has been reported. However, certain genetic relationships have been established. Fetal mutations in tumor necrosis factor–alpha appear to increase the likelihood of cutaneous manifestations. Mutations in transforming growth factor beta appear to increase the likelihood of cardiac manifestations, and experiments in cultured mouse cardiocytes have shown anti-SSB antibodies to impair macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in the developing fetal heart. These observations taken together suggest a fibroblast-mediated response to unphagocytosed cardiocyte debris may account for conduction abnormalities in neonates with NLE-induced heart block.6

Cutaneous disease in NLE is possible at birth, but more skin findings develop upon exposure to the sun. Nearly 80% of neonates affected by NLE develop cutaneous manifestations in the first few months of life. The head, neck, and extensor surfaces of the arms are most commonly affected, presumably because they are most likely to be exposed to the sun. Erythematous, annular, or discoid lesions are most common, and periorbital erythema with or without scale (“raccoon eyes”) should prompt consideration of NLE. However, annular, or discoid lesions are sometimes not present in NLE; telangiectasias, bullae, atrophic divots (“ice-pick scars”) or ulcerations may be seen instead. Lesions in the genital area have been described in fewer than 5% of patients with NLE.

The differential diagnosis of annular, scaly lesions in neonates includes annular erythema of infancy, tinea corporis, and seborrheic dermatitis. Annular erythema of infancy is a rare skin condition characterized by a cyclical eruption of erythematous annular lesions with minimal scaling which resolve spontaneously within a few weeks to months without leaving scaring or pigment changes. There is no treatment needed as the lesions self-resolve.7 Acute urticaria can sometimes appear similar to NLE but these are not scaly and also the lesions will disappear within 24-36 hours, compared with NLE lesions, which may take weeks to months to go away. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin condition seen in newborns with in the first few weeks of life and can present as scaly annular erythematous plaques on the face, scalp, torso, and the diaper area. Seborrheic dermatitis usually responds well to a combination of an antiyeast cream and a low-potency topical corticosteroid medication.

When NLE is suspected, diagnostic testing for lupus antibodies (anti-SSA, anti-SSB, and anti-U1RNP) in both maternal and neonatal serum should be undertaken. The presence of a characteristic rash plus maternal or neonatal antibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis. If the rash is less characteristic, a biopsy showing an interface dermatitis can help solidify the diagnosis. Neonates with cutaneous manifestations of lupus may also have systemic disease. The most common and serious complication is heart block, whose pathophysiology is described above. Neonates with evidence of first-, second-, or third-degree heart block should be referred to a pediatric cardiologist for careful monitoring and management. Hepatic involvement has been reported, but is usually mild. Hematologic abnormalities have also been described that include anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, which resolve by 9 months of age. Central nervous system involvement may rarely occur. The mainstay of treatment for the rash in NLE is diligent sun avoidance and sun protection. Topical corticosteroids may be used, but are not needed as the rash typically resolves by 9 months to 1 year without treatment. Mothers who have one child with NLE should be advised that they are more likely to have another with NLE – the risk is as high as 30%-40% in the second child. Hydroxychloroquine taken during subsequent pregnancies can reduce the incidence of cardiac complications,8 as can the so-called “triple therapy” of plasmapheresis, steroids, and IVIg.9

The cutaneous manifestations of NLE are usually self-limiting. However, they can serve as important clues that can prompt diagnosis of SLE in the mother, investigation of cardiac complications in the infant, and appropriate preventative care in future pregnancies.

Dr. Matiz is with the department of dermatology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is with the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. Moretti D et al. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1508-12.

2. Buyon JP et al. Nature Clin Prac Rheum. 2009;5(3):139-48.

3. Li Y-Q et al. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(7):761-7.

4. Rivera TL et al. Annals Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):828-35.

5. Li L et al. Zhonghua er ke za zhi 2011;49(2):146-50.

6. Izmirly PM et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1641-5.

7. Toledo-Alberola F and Betlloch-Mas I. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010 Jul;101(6):473-84.

8. Izmirly PM et al. Circulation. 2012;126(1):76-82.

9. Martinez-Sanchez N et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(5):423-8.

A 1-month-old, full-term female, born via normal vaginal delivery, presented to the dermatology clinic with a 3-week history of recurrent skin lesions on the scalp, face, and chest. The mother has been treating the lesions with breast milk and most recently with clotrimazole cream without resolution.

The mother of the baby is a healthy 32-year-old female with no past medical history. She had adequate prenatal care, and all the prenatal infectious and genetic tests were normal. The baby has been healthy and growing well. There is no history of associated fevers, chills, or any other symptoms. The family took no recent trips, and the parents are not affected. There are no other children at home and they have a cat and a dog. The family history is noncontributory.

On physical examination the baby was not in acute distress and her vital signs were normal. On skin examination she had several erythematous annular plaques and patches on the face, scalp, and upper chest (Fig. 1). There was no liver or spleen enlargement and no lymphadenopathy was palpated on exam.

A male with pruritic scaling and bumps in the red area of a tattoo placed months earlier

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

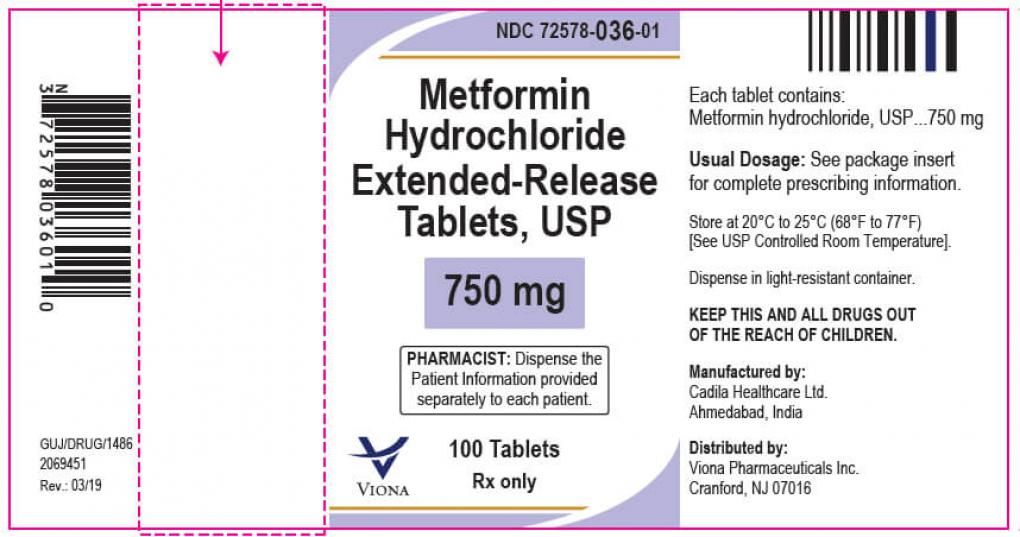

FDA: More metformin extended-release tablets recalled

Two lots of metformin HCl extended-release tablets have been recalled by Viona Pharmaceuticals because unacceptable levels of nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a likely carcinogen, were found in the 750-mg tablets.

According to a June 11 alert from the Food and Drug Administration, the affected lot numbers are M915601 and M915602.

This generic product was made by Cadila Healthcare, Ahmedabad, India, in November 2019 with an expiration date of October 2021, and distributed throughout the United States. The pill is white to off-white, capsule-shaped, uncoated tablets, debossed with “Z”, “C” on one side and “20” on the other side.

No adverse events related to the lots involved in the recall have been reported, the FDA said. It also recommends that clinicians continue to prescribe metformin when clinically appropriate.

In late 2019, the FDA announced it had become aware of NDMA in some metformin products in other countries. The agency immediately began testing to determine whether the metformin in the U.S. supply was at risk, as part of the ongoing investigation into nitrosamine impurities across medication types, which included recalls of hypertension and heartburn medications within the past 3 years.

In February 2020, the FDA reported that they hadn’t found NDMA levels that exceeded the acceptable daily intake. But starting in May 2020, voluntary recalls by, numerous manufacturers have been announced as levels of the compound exceeded that cutoff.

Two lots of metformin HCl extended-release tablets have been recalled by Viona Pharmaceuticals because unacceptable levels of nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a likely carcinogen, were found in the 750-mg tablets.

According to a June 11 alert from the Food and Drug Administration, the affected lot numbers are M915601 and M915602.

This generic product was made by Cadila Healthcare, Ahmedabad, India, in November 2019 with an expiration date of October 2021, and distributed throughout the United States. The pill is white to off-white, capsule-shaped, uncoated tablets, debossed with “Z”, “C” on one side and “20” on the other side.

No adverse events related to the lots involved in the recall have been reported, the FDA said. It also recommends that clinicians continue to prescribe metformin when clinically appropriate.

In late 2019, the FDA announced it had become aware of NDMA in some metformin products in other countries. The agency immediately began testing to determine whether the metformin in the U.S. supply was at risk, as part of the ongoing investigation into nitrosamine impurities across medication types, which included recalls of hypertension and heartburn medications within the past 3 years.

In February 2020, the FDA reported that they hadn’t found NDMA levels that exceeded the acceptable daily intake. But starting in May 2020, voluntary recalls by, numerous manufacturers have been announced as levels of the compound exceeded that cutoff.

Two lots of metformin HCl extended-release tablets have been recalled by Viona Pharmaceuticals because unacceptable levels of nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a likely carcinogen, were found in the 750-mg tablets.

According to a June 11 alert from the Food and Drug Administration, the affected lot numbers are M915601 and M915602.

This generic product was made by Cadila Healthcare, Ahmedabad, India, in November 2019 with an expiration date of October 2021, and distributed throughout the United States. The pill is white to off-white, capsule-shaped, uncoated tablets, debossed with “Z”, “C” on one side and “20” on the other side.

No adverse events related to the lots involved in the recall have been reported, the FDA said. It also recommends that clinicians continue to prescribe metformin when clinically appropriate.

In late 2019, the FDA announced it had become aware of NDMA in some metformin products in other countries. The agency immediately began testing to determine whether the metformin in the U.S. supply was at risk, as part of the ongoing investigation into nitrosamine impurities across medication types, which included recalls of hypertension and heartburn medications within the past 3 years.

In February 2020, the FDA reported that they hadn’t found NDMA levels that exceeded the acceptable daily intake. But starting in May 2020, voluntary recalls by, numerous manufacturers have been announced as levels of the compound exceeded that cutoff.

FROM THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Expert shares her tips for an effective cosmetic consultation

The way Kelly Stankiewicz, MD, sees it,

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked into a room and thought the patient would say they’re concerned about one thing, but they’re concerned about something totally different,” Dr. Stankiewicz, a dermatologist in private practice in Park City, Utah, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The first question I ask is, ‘What would you like to improve?’ ‘What’s bothering you?’ ‘What would you like to make look better?’ Frequently, it’s not what you think.”

Next, she tries to get a sense of their lifestyle by asking patients about their occupation, hobbies, and outdoor activities they may engage in. “Here in Park City, it’s very sunny most all the time, so treatments need to be tailored to when those outdoor activities are being done, or perhaps they can be avoided for a period of time,” she said. “This gives you an idea of what kind of downtime people will tolerate. I also like to hear about their history of cosmetic procedures. If someone has had a lot of cosmetic procedures done, you can talk with them on a more detailed level. If someone is completely unaware of treatment options, you have to keep it simple.”

Dr. Stankiewicz also reviews their personal history of cosmetic procedures when considering safety of treatment. “For instance, if somebody has had a neck lift, you want to be very cautious doing any ablative procedures along the jawline,” she said. “I also like to know if anyone has had any reactions to dermal fillers or neuromodulators that they did not like. It’s very helpful to hear from patients what’s worked for them and what hasn’t. I also like to keep my ear open for pricing concerns. Not everyone will bring up the pricing issues, but sometimes they will, and it’s an important piece of information. Lastly, it’s important to look for any warning signs like irrational behavior or unrealistic expectations. These are patients you want to try to avoid treating.”

She shared four other key components to an effective cosmetic consultation, including the examination itself, which she prefers to separate from the discussion portion of the visit. “I lean the patient back in the exam chair and shine the light on their skin, which is important for evaluating for conditions you may not have discussed that could be easily improved,” Dr. Stankiewicz said.

“If the patient is concerned about pigmented lesions, I’ll pull out my dermatoscope to make sure there isn’t any concern for skin cancer. After the examination, I’ll sit the patient up again so that there is a very distinct start and finish to the examination portion of my cosmetic consultation.”

Surgery vs. noninvasive treatments

Step three in her consultative process is to review treatment options with patients. “I never hold back if surgery is their best treatment option,” she said. “I don’t perform surgery, but I have a list of people I can refer them to.”

Once she addresses the potential for surgery, she reviews noninvasive treatment options, including topical products, injectables, lasers, and chemical peels. “Everyone who comes in for a cosmetic consultation leaves with some sort of topical recommendation, even if it’s as simple as a sunscreen I think they would like or a prescription for generic tretinoin,” she said. “I always present options in a framework starting with those that require lower downtime, higher number of treatment options, and lower cost. Then I move up the scale to tell them more about treatments that require higher downtime, a lower number of treatments, but have a higher cost.”

Step four in her consultative process involves discussing her final treatment recommendations. She’ll say something like, “I’ve been through all these options with you and my final recommendation is X,” and the patient walks away with a clear understanding of the recommendations, she said. “When I leave the room after giving my final recommendation, I’ll write everything down outside of the room, or I’ll have a member of my staff write down everything I’ve said outside the room.”

Finally, she and her staff record all the relevant information for the patient as a customized handout, including the treatment options discussed, how many will be required, whether they have to come in early for numbing cream or not, and the per treatment price tag. “Once we’ve written down everything we’ve discussed, I’ll circle or I’ll star my recommended treatment,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. They also have a handout for topical products, and she checks off the topical products that she discussed with the patient. The third handout she provides to patients is a recommended skin care regimen.

Dr. Stankiewicz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The way Kelly Stankiewicz, MD, sees it,

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked into a room and thought the patient would say they’re concerned about one thing, but they’re concerned about something totally different,” Dr. Stankiewicz, a dermatologist in private practice in Park City, Utah, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The first question I ask is, ‘What would you like to improve?’ ‘What’s bothering you?’ ‘What would you like to make look better?’ Frequently, it’s not what you think.”

Next, she tries to get a sense of their lifestyle by asking patients about their occupation, hobbies, and outdoor activities they may engage in. “Here in Park City, it’s very sunny most all the time, so treatments need to be tailored to when those outdoor activities are being done, or perhaps they can be avoided for a period of time,” she said. “This gives you an idea of what kind of downtime people will tolerate. I also like to hear about their history of cosmetic procedures. If someone has had a lot of cosmetic procedures done, you can talk with them on a more detailed level. If someone is completely unaware of treatment options, you have to keep it simple.”

Dr. Stankiewicz also reviews their personal history of cosmetic procedures when considering safety of treatment. “For instance, if somebody has had a neck lift, you want to be very cautious doing any ablative procedures along the jawline,” she said. “I also like to know if anyone has had any reactions to dermal fillers or neuromodulators that they did not like. It’s very helpful to hear from patients what’s worked for them and what hasn’t. I also like to keep my ear open for pricing concerns. Not everyone will bring up the pricing issues, but sometimes they will, and it’s an important piece of information. Lastly, it’s important to look for any warning signs like irrational behavior or unrealistic expectations. These are patients you want to try to avoid treating.”

She shared four other key components to an effective cosmetic consultation, including the examination itself, which she prefers to separate from the discussion portion of the visit. “I lean the patient back in the exam chair and shine the light on their skin, which is important for evaluating for conditions you may not have discussed that could be easily improved,” Dr. Stankiewicz said.

“If the patient is concerned about pigmented lesions, I’ll pull out my dermatoscope to make sure there isn’t any concern for skin cancer. After the examination, I’ll sit the patient up again so that there is a very distinct start and finish to the examination portion of my cosmetic consultation.”

Surgery vs. noninvasive treatments

Step three in her consultative process is to review treatment options with patients. “I never hold back if surgery is their best treatment option,” she said. “I don’t perform surgery, but I have a list of people I can refer them to.”

Once she addresses the potential for surgery, she reviews noninvasive treatment options, including topical products, injectables, lasers, and chemical peels. “Everyone who comes in for a cosmetic consultation leaves with some sort of topical recommendation, even if it’s as simple as a sunscreen I think they would like or a prescription for generic tretinoin,” she said. “I always present options in a framework starting with those that require lower downtime, higher number of treatment options, and lower cost. Then I move up the scale to tell them more about treatments that require higher downtime, a lower number of treatments, but have a higher cost.”

Step four in her consultative process involves discussing her final treatment recommendations. She’ll say something like, “I’ve been through all these options with you and my final recommendation is X,” and the patient walks away with a clear understanding of the recommendations, she said. “When I leave the room after giving my final recommendation, I’ll write everything down outside of the room, or I’ll have a member of my staff write down everything I’ve said outside the room.”

Finally, she and her staff record all the relevant information for the patient as a customized handout, including the treatment options discussed, how many will be required, whether they have to come in early for numbing cream or not, and the per treatment price tag. “Once we’ve written down everything we’ve discussed, I’ll circle or I’ll star my recommended treatment,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. They also have a handout for topical products, and she checks off the topical products that she discussed with the patient. The third handout she provides to patients is a recommended skin care regimen.

Dr. Stankiewicz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The way Kelly Stankiewicz, MD, sees it,

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked into a room and thought the patient would say they’re concerned about one thing, but they’re concerned about something totally different,” Dr. Stankiewicz, a dermatologist in private practice in Park City, Utah, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “The first question I ask is, ‘What would you like to improve?’ ‘What’s bothering you?’ ‘What would you like to make look better?’ Frequently, it’s not what you think.”

Next, she tries to get a sense of their lifestyle by asking patients about their occupation, hobbies, and outdoor activities they may engage in. “Here in Park City, it’s very sunny most all the time, so treatments need to be tailored to when those outdoor activities are being done, or perhaps they can be avoided for a period of time,” she said. “This gives you an idea of what kind of downtime people will tolerate. I also like to hear about their history of cosmetic procedures. If someone has had a lot of cosmetic procedures done, you can talk with them on a more detailed level. If someone is completely unaware of treatment options, you have to keep it simple.”

Dr. Stankiewicz also reviews their personal history of cosmetic procedures when considering safety of treatment. “For instance, if somebody has had a neck lift, you want to be very cautious doing any ablative procedures along the jawline,” she said. “I also like to know if anyone has had any reactions to dermal fillers or neuromodulators that they did not like. It’s very helpful to hear from patients what’s worked for them and what hasn’t. I also like to keep my ear open for pricing concerns. Not everyone will bring up the pricing issues, but sometimes they will, and it’s an important piece of information. Lastly, it’s important to look for any warning signs like irrational behavior or unrealistic expectations. These are patients you want to try to avoid treating.”

She shared four other key components to an effective cosmetic consultation, including the examination itself, which she prefers to separate from the discussion portion of the visit. “I lean the patient back in the exam chair and shine the light on their skin, which is important for evaluating for conditions you may not have discussed that could be easily improved,” Dr. Stankiewicz said.

“If the patient is concerned about pigmented lesions, I’ll pull out my dermatoscope to make sure there isn’t any concern for skin cancer. After the examination, I’ll sit the patient up again so that there is a very distinct start and finish to the examination portion of my cosmetic consultation.”

Surgery vs. noninvasive treatments

Step three in her consultative process is to review treatment options with patients. “I never hold back if surgery is their best treatment option,” she said. “I don’t perform surgery, but I have a list of people I can refer them to.”

Once she addresses the potential for surgery, she reviews noninvasive treatment options, including topical products, injectables, lasers, and chemical peels. “Everyone who comes in for a cosmetic consultation leaves with some sort of topical recommendation, even if it’s as simple as a sunscreen I think they would like or a prescription for generic tretinoin,” she said. “I always present options in a framework starting with those that require lower downtime, higher number of treatment options, and lower cost. Then I move up the scale to tell them more about treatments that require higher downtime, a lower number of treatments, but have a higher cost.”

Step four in her consultative process involves discussing her final treatment recommendations. She’ll say something like, “I’ve been through all these options with you and my final recommendation is X,” and the patient walks away with a clear understanding of the recommendations, she said. “When I leave the room after giving my final recommendation, I’ll write everything down outside of the room, or I’ll have a member of my staff write down everything I’ve said outside the room.”

Finally, she and her staff record all the relevant information for the patient as a customized handout, including the treatment options discussed, how many will be required, whether they have to come in early for numbing cream or not, and the per treatment price tag. “Once we’ve written down everything we’ve discussed, I’ll circle or I’ll star my recommended treatment,” Dr. Stankiewicz said. They also have a handout for topical products, and she checks off the topical products that she discussed with the patient. The third handout she provides to patients is a recommended skin care regimen.

Dr. Stankiewicz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ASLMS 2021

Pilot study: Hybrid laser found effective for treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

, results from a pilot trial showed.

“The genitourinary syndrome of menopause causes suffering in breast cancer survivors and postmenopausal women,” Jill S. Waibel, MD, said during the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. A common side effect for breast cancer survivors is early onset of menopause that is brought on by treatment, specifically aromatase-inhibitor therapies, she noted.

The symptoms of GSM include discomfort during sex, impaired sexual function, burning or sensation or irritation of the genital area, vaginal constriction, frequent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and vaginal laxity, said Dr. Waibel, owner and medical director of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute. Nonhormonal treatments have included OTC vaginal lubricants, OTC moisturizers, low-dose vaginal estrogen – which increases the risk of breast cancer – and systemic estrogen therapy, which also can increase the risk of breast and endometrial cancer. “So, we need a healthy, nondrug option,” she said.

The objective of the pilot study was to determine the safety and efficacy of the diVa hybrid fractional laser as a treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy. The laser applies tunable nonablative (1,470-nm) and ablative (2,940-nm) wavelengths to the same microscopic treatment zone to maximize results and reduce downtime. The device features a motorized precision guidance system and calibrated rotation for homogeneous pulsing.

“The 2,940-nm wavelength is used to ablate to a depth of 0-800 micrometers while the 1,470-nm wavelength is used to coagulate the epithelium and the lamina propria at a depth of 100-700 micrometers,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also subsection chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital of Miami. “This combination is used for epithelial tissue to heal quickly and the lamina propria to remodel slowly over time, laying down more collagen in tissue.” Each procedure is delivered via a single-use dilator, which expands the vaginal canal for increased treatment area. “The tip length is 5.5 cm and the diameter is 1 cm,” she said. “The clear tip acts as a hygienic barrier between the tip and the handpiece.”

Study participants included 25 women between the ages of 40 and 70 with early menopause after breast cancer or vaginal atrophy: 20 in the treatment arm and 5 in the sham-treatment arm. Dr. Waibel performed three procedures 2 weeks apart. An ob.gyn. assessed the primary endpoints, which included the Vaginal Health Index Scale (VHIS), the Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire, and the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging (DIVA) questionnaire. Secondary endpoints were histology and a satisfaction questionnaire.

Of the women in the treated group, there were data available for 19 at 3 months follow-up and 17 at 6 months follow-up. Based on the results in these patients, there were statistically significant improvements in nearly all domains of the FSFI treatment arm at 3 and 6 months when compared to baseline, especially arousal (P values of .05 at 3 months and .01 at 6 months) and lubrication (P values of .009 at three months and .001 at 6 months).

Between 3 and 6 months, patients in the treatment arm experienced improvements in four dimensions of the DIVA questionnaire: daily activities (P value of .01 at 3 months to .010 at 6 months), emotional well-being (P value of .06 at 3 months to .014 at 6 months), sexual function (P value of .30 at 3 months to .003 at 6 months), and self-concept/body image (P value of .002 at 3 months to .001 at 6 months).

As for satisfaction, a majority of those in the treatment arm were “somewhat satisfied” with the treatment and would “somewhat likely” repeat and recommend the treatment to friends and family, Dr. Waibel said. Results among the women in the control arm, who were also surveyed, were in the similar range, she noted. (No other results for women in the control arm were available.)

Following treatments, histology revealed that the collagen was denser, fibroblasts were more dense, and vascularity was more notable. No adverse events were observed. “The hybrid fractional laser is safe and effective for treating GSM, early menopause after breast cancer, or vaginal atrophy,” Dr. Waibel concluded. Further studies are important to improve the understanding of “laser dosimetry, frequency of treatments, and longevity of effect. Collaboration between ob.gyns. and dermatologists is important as we learn about laser therapy in GSM.”

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board of Sciton, which manufactures the diVa laser. She has also conducted clinical trials for many other device and pharmaceutical companies.

FROM ASLMS 2021

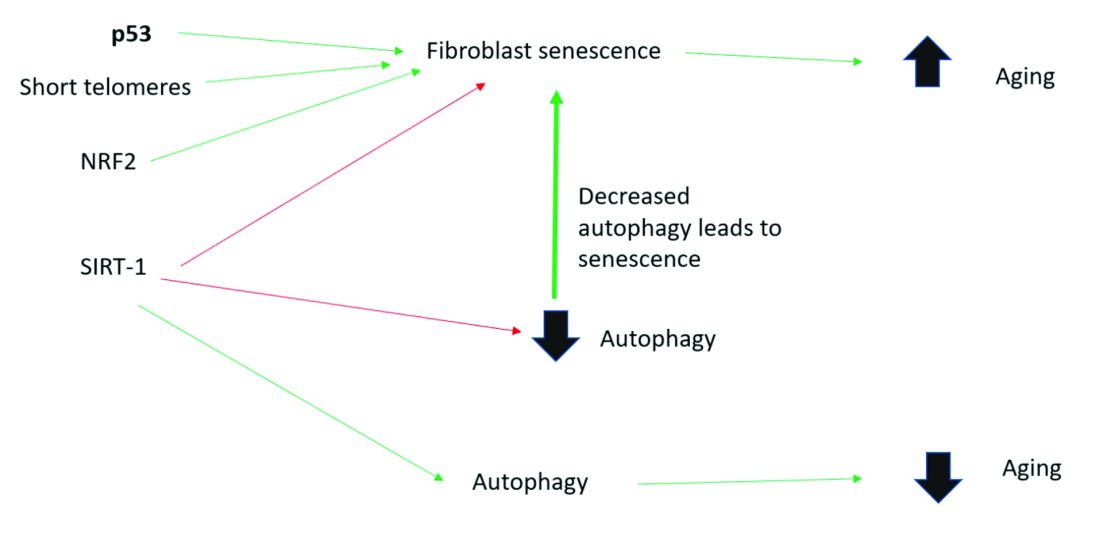

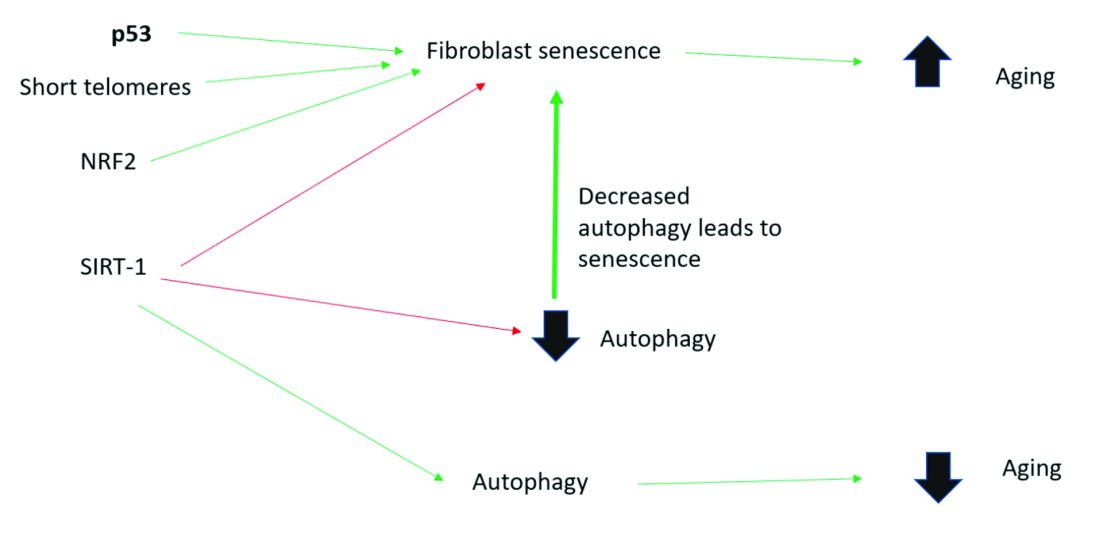

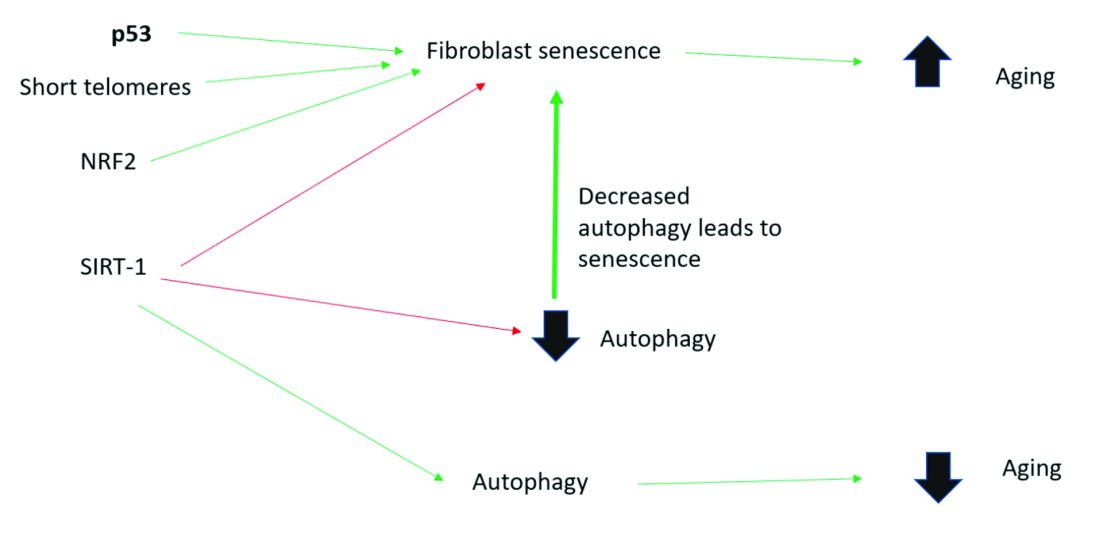

Cellular senescence, skin aging, and cosmeceuticals

I just completed the third edition of my Cosmetic Dermatology textbook (McGraw Hill), which will come out later this year. Although writing it is a huge effort, I really enjoy all the basic science. While I was working on the book, I was most surprised by the .

Right now, it is too early, and we don’t know enough yet, to have cosmeceuticals that affect cellular senescence and autophagy. But, it’s not too early to learn about this research, to avoid falling prey to any pseudoscience that invariably ends up affecting cosmeceuticals on the market. The following is a brief primer on cellular senescence, skin aging, and cosmeceuticals; it represents what we currently know.

Cell phases

Keratinocytes and fibroblasts go through five different phases: stem, proliferation, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis. The difference between apoptotic cells and senescent cells is that apoptotic cells are not viable and are eliminated, while senescent cells, even though they have gone into cell cycle arrest, remain functional and are not eliminated from the skin.

What are senescent cells?

Senescent cells have lost the ability to proliferate but have not undergone apoptosis. Senescent human skin fibroblasts in cell culture lose the youthful spindlelike shape and become enlarged and flattened.1 Their lysosomes and mitochondria lose functionality.2 The presence of senescent cells is associated with increased aging and seems to speed aging.

Senescent cells and skin aging

Senescent cells are increased in the age-related phenotype3 because of an age-related decline of senescent cell removal systems, such as the immune system4 and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway.5 Senescent cells are deleterious because they develop into a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which is believed to be one of the major causes of aging. SASP cells communicate with nearby cells using proinflammatory cytokines, which include catabolic modulators such as Matrix metalloproteinases. They are known to release growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, matrix-modeling enzymes, lipids, and extracellular vesicles. The last are lipid bilayer-lined vesicles that can transport functional RNA and microRNA and facilitate other modes of communication between cells.6

The SASP is likely a natural tumor suppressive mode employed by cells to prevent cells with cancerous mutations from undergoing replication;7 however, when it comes to aging, the deleterious effects of SASP outweigh the beneficial effects. For example, SASP contributes to a prolonged state of inflammation, known as “inflammaging,”8 which is detrimental to the skin’s appearance. Human fibroblasts that have assumed the SASP secrete proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs and release reactive oxygen species,9,10 resulting in degradation of the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). Loss of the ECM leads to fibroblast compaction and reduced DNA synthesis, all caused by SASPs.9

What causes cellular senescence?

Activation of the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related transcription factor 2 (NRF2) induces cellular senescence via direct targeting of certain ECM genes. NRF2 is a key regulator of the skin’s antioxidant defense system, which controls the transcription of genes encoding reactive oxygen species–detoxifying enzymes and various other antioxidant proteins.11 Loss of mitochondrial autophagy also induces senescence, as do activation of the TP53 gene, inactivity of SIRT-1, and short telomeres.

Cellular senescence and skin aging

Timely clearance of senescent cells before they create too much damage postpones the onset and severity of age-related diseases and extends the life span of mice.12,6 Antiaging treatments should focus on decreasing the number of senescent cells and reverting senescent cells to the more juvenile forms: proliferating or differentiating cells as an approach to prevent skin aging.13 Restoration of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis has been shown to revert SASP back to a juvenile status. Normalization of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis is a prerequisite to reverse senescence.14

Cellular senescence, autophagy, the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis, and cosmeceuticals

Autophagy is the important process of organelles, like mitochondria,15 self-digesting their cytoplasmic material into lysosomes for degradation. Mitochondrial autophagy is very important in slowing the aging process because damaged mitochondria generate free radicals. As you can imagine, much research is focused on this area, but it is too early for any research to translate to efficacious cosmeceuticals.

Conclusion

To summarize, activation of sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) has been shown to extend the lifespan of mammals, as does caloric restriction.16 This extension occurs because SIRT-1 decreases senescence and activates autophagy.

Although we do not yet know whether topical skincare products could affect senescence or autophagy, there are data to show that oral resveratrol16 and melatonin17 activate SIRT-1 and increase autophagy. I am closely watching this research and will let you know if there are any similar data on topical cosmeceuticals targeting senescence or autophagy. Stay tuned!

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Papadopoulou A et al. Biogerontology. 2020 Dec;21(6):695-708.

2. López-Otin C et al. Cell. 2013 June 6;153, 1194–217.

3. Yoon J E et al. Theranostics. 2018 Sep 9;8(17):4620-32.

4. Rodier F, Campisi J. J Cell Biol. 2011 Feb 21;192(4):547-56.

5. Dutta D et al. Circ Res. 2012 Apr 13;110(8):1125-38.

6. Terlecki-Zaniewicz L et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Dec;139(12):2425-36.e5.

7. Campisi J et al. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Sep;8(9):729-40.

8. Franceschi C and Campisi J. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Jun;69 Suppl 1:S4-9.

9. Nelson G et al. Aging Cell. 2012 Apr;11(2):345-9.

10. Passos JF et al. PLoS Biol. 2007 May;5(5):e110.

11. Hiebert P et al. Dev Cell. 2018 Jul 16;46(2):145-61.e10.

12. Baker DJ et al. Nature. 2016 Feb 11:530(7589):184-9.

13. Mavrogonatou E et al. Matrix Biol. 2019 Jan;75-76:27-42.

14. Park JT et al. Ageing Res Rev. 2018 Nov;47:176-82.

15. Levine B and Kroemer G. Cell. 2019 Jan 10;176(1-2):11-42.

16. Morselli E et al. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1(1):e10.

17. Lee JH et al. Oncotarget. 2016 Mar 15;7(11):12075-88.

I just completed the third edition of my Cosmetic Dermatology textbook (McGraw Hill), which will come out later this year. Although writing it is a huge effort, I really enjoy all the basic science. While I was working on the book, I was most surprised by the .

Right now, it is too early, and we don’t know enough yet, to have cosmeceuticals that affect cellular senescence and autophagy. But, it’s not too early to learn about this research, to avoid falling prey to any pseudoscience that invariably ends up affecting cosmeceuticals on the market. The following is a brief primer on cellular senescence, skin aging, and cosmeceuticals; it represents what we currently know.

Cell phases

Keratinocytes and fibroblasts go through five different phases: stem, proliferation, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis. The difference between apoptotic cells and senescent cells is that apoptotic cells are not viable and are eliminated, while senescent cells, even though they have gone into cell cycle arrest, remain functional and are not eliminated from the skin.

What are senescent cells?

Senescent cells have lost the ability to proliferate but have not undergone apoptosis. Senescent human skin fibroblasts in cell culture lose the youthful spindlelike shape and become enlarged and flattened.1 Their lysosomes and mitochondria lose functionality.2 The presence of senescent cells is associated with increased aging and seems to speed aging.

Senescent cells and skin aging

Senescent cells are increased in the age-related phenotype3 because of an age-related decline of senescent cell removal systems, such as the immune system4 and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway.5 Senescent cells are deleterious because they develop into a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which is believed to be one of the major causes of aging. SASP cells communicate with nearby cells using proinflammatory cytokines, which include catabolic modulators such as Matrix metalloproteinases. They are known to release growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, matrix-modeling enzymes, lipids, and extracellular vesicles. The last are lipid bilayer-lined vesicles that can transport functional RNA and microRNA and facilitate other modes of communication between cells.6

The SASP is likely a natural tumor suppressive mode employed by cells to prevent cells with cancerous mutations from undergoing replication;7 however, when it comes to aging, the deleterious effects of SASP outweigh the beneficial effects. For example, SASP contributes to a prolonged state of inflammation, known as “inflammaging,”8 which is detrimental to the skin’s appearance. Human fibroblasts that have assumed the SASP secrete proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs and release reactive oxygen species,9,10 resulting in degradation of the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). Loss of the ECM leads to fibroblast compaction and reduced DNA synthesis, all caused by SASPs.9

What causes cellular senescence?

Activation of the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related transcription factor 2 (NRF2) induces cellular senescence via direct targeting of certain ECM genes. NRF2 is a key regulator of the skin’s antioxidant defense system, which controls the transcription of genes encoding reactive oxygen species–detoxifying enzymes and various other antioxidant proteins.11 Loss of mitochondrial autophagy also induces senescence, as do activation of the TP53 gene, inactivity of SIRT-1, and short telomeres.

Cellular senescence and skin aging

Timely clearance of senescent cells before they create too much damage postpones the onset and severity of age-related diseases and extends the life span of mice.12,6 Antiaging treatments should focus on decreasing the number of senescent cells and reverting senescent cells to the more juvenile forms: proliferating or differentiating cells as an approach to prevent skin aging.13 Restoration of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis has been shown to revert SASP back to a juvenile status. Normalization of the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis is a prerequisite to reverse senescence.14

Cellular senescence, autophagy, the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis, and cosmeceuticals

Autophagy is the important process of organelles, like mitochondria,15 self-digesting their cytoplasmic material into lysosomes for degradation. Mitochondrial autophagy is very important in slowing the aging process because damaged mitochondria generate free radicals. As you can imagine, much research is focused on this area, but it is too early for any research to translate to efficacious cosmeceuticals.

Conclusion

To summarize, activation of sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) has been shown to extend the lifespan of mammals, as does caloric restriction.16 This extension occurs because SIRT-1 decreases senescence and activates autophagy.

Although we do not yet know whether topical skincare products could affect senescence or autophagy, there are data to show that oral resveratrol16 and melatonin17 activate SIRT-1 and increase autophagy. I am closely watching this research and will let you know if there are any similar data on topical cosmeceuticals targeting senescence or autophagy. Stay tuned!

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Papadopoulou A et al. Biogerontology. 2020 Dec;21(6):695-708.

2. López-Otin C et al. Cell. 2013 June 6;153, 1194–217.

3. Yoon J E et al. Theranostics. 2018 Sep 9;8(17):4620-32.

4. Rodier F, Campisi J. J Cell Biol. 2011 Feb 21;192(4):547-56.

5. Dutta D et al. Circ Res. 2012 Apr 13;110(8):1125-38.

6. Terlecki-Zaniewicz L et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Dec;139(12):2425-36.e5.

7. Campisi J et al. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Sep;8(9):729-40.

8. Franceschi C and Campisi J. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Jun;69 Suppl 1:S4-9.

9. Nelson G et al. Aging Cell. 2012 Apr;11(2):345-9.

10. Passos JF et al. PLoS Biol. 2007 May;5(5):e110.

11. Hiebert P et al. Dev Cell. 2018 Jul 16;46(2):145-61.e10.

12. Baker DJ et al. Nature. 2016 Feb 11:530(7589):184-9.

13. Mavrogonatou E et al. Matrix Biol. 2019 Jan;75-76:27-42.

14. Park JT et al. Ageing Res Rev. 2018 Nov;47:176-82.

15. Levine B and Kroemer G. Cell. 2019 Jan 10;176(1-2):11-42.

16. Morselli E et al. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1(1):e10.

17. Lee JH et al. Oncotarget. 2016 Mar 15;7(11):12075-88.

I just completed the third edition of my Cosmetic Dermatology textbook (McGraw Hill), which will come out later this year. Although writing it is a huge effort, I really enjoy all the basic science. While I was working on the book, I was most surprised by the .

Right now, it is too early, and we don’t know enough yet, to have cosmeceuticals that affect cellular senescence and autophagy. But, it’s not too early to learn about this research, to avoid falling prey to any pseudoscience that invariably ends up affecting cosmeceuticals on the market. The following is a brief primer on cellular senescence, skin aging, and cosmeceuticals; it represents what we currently know.

Cell phases

Keratinocytes and fibroblasts go through five different phases: stem, proliferation, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis. The difference between apoptotic cells and senescent cells is that apoptotic cells are not viable and are eliminated, while senescent cells, even though they have gone into cell cycle arrest, remain functional and are not eliminated from the skin.

What are senescent cells?

Senescent cells have lost the ability to proliferate but have not undergone apoptosis. Senescent human skin fibroblasts in cell culture lose the youthful spindlelike shape and become enlarged and flattened.1 Their lysosomes and mitochondria lose functionality.2 The presence of senescent cells is associated with increased aging and seems to speed aging.

Senescent cells and skin aging

Senescent cells are increased in the age-related phenotype3 because of an age-related decline of senescent cell removal systems, such as the immune system4 and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway.5 Senescent cells are deleterious because they develop into a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which is believed to be one of the major causes of aging. SASP cells communicate with nearby cells using proinflammatory cytokines, which include catabolic modulators such as Matrix metalloproteinases. They are known to release growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, matrix-modeling enzymes, lipids, and extracellular vesicles. The last are lipid bilayer-lined vesicles that can transport functional RNA and microRNA and facilitate other modes of communication between cells.6