User login

Promising HER2+/HR– breast cancer survival with de-escalated therapy

It may not be always necessary to approach the treatment of HER2-positive, hormone receptor–negative (HER2+/HR–) early breast cancer with added chemotherapy, survival results of a prospective multicenter randomized trial suggest.

In the ADAPT-HER2+/HR– trial, comparing a de-escalated 12-week neoadjuvant regimen consisting of dual HER2 blockade with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta) with or without weekly paclitaxel, the three-drug regimen was associated with high pathologic complete response(pCR) rates and excellent 5-year survival, irrespective of whether patients received additional chemotherapy, reported Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich.

“Chemotherapy-free regimens are promising in highly sensitive tumors with early response, but future investigation of such chemotherapy-free regimens need to be focused on selected patients, like those with HER2 3+ tumors, non–basal-like tumors, those showing early response to the de-escalated therapy, and those with predictive RNA signatures such as immune signatures,” she said in an oral abstract session during the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting (Abstract 503).

Under the WGS umbrella

The ADAPT HER2+/HR– trial (NCT01779206) is one of several conducted by the West German Study Group (WGS) on therapy for intrinsic breast cancer types.

In this study, 134 patients with HER2-positive, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative tumors with no metastatic disease and good performance status were assigned on a 5:2 basis to neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg for the first cycle followed by 6 mg/kg for subsequent cycles every 3 weeks x 4, plus pertuzumab at a loading dose of 840 mg followed by 420 mg every 3 weeks x 4 (92 patients), or to trastuzumab and pertuzumab at the same dose and schedule plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 once weekly for 12 weeks.

Patients had surgery within 3 weeks of the end of study therapy unless they did not have a histologically confirmed pCR, in which case they went on to receive standard neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery.

Adjuvant therapy was performed according to national guidelines, although patients with a pCR after 12 weeks of study therapy could be spared from adjuvant chemotherapy at the investigator’s discretion.

Patients underwent biopsy at 3 weeks for therapy for early response assessment, defined as either a Ki67 decrease of at least 30% from baseline, or low cellularity (less than 500 invasive tumor cells).

First survival results

The investigators previously reported the primary pCR endpoint from the trial, which showed a rate of 90% after 12 weeks in the three-drug arm, and a “substantial and clinically meaningful” pCR rate of 34% after the trastuzumab plus pertuzumab alone.

At ASCO 2021, Dr. Harbeck reported the first survival data from the trial.

After a median follow-up of 59.9 months, there were no statistically significant differences between trial arms in either overall survival, invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), or distant disease-free survival (dDFS).

The 5-year iDFS rate in the three-drug arm was 98%, compared with 87% for the dual HER2 blockade-only arm, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The 5-year dDFS rates were 98% and 92% respectively. There were only seven dDFS events during follow-up, Dr. Harbeck noted.

There were only six deaths during follow-up, with overall survival rates of 98% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, and 94% in the anti-HER2 antibodies–only arm, a difference of one overall survival event, Dr. Harbeck said.

pCR counts

However, patients who did not have pathologic complete responses at the end of first-line de-escalated therapy had worse outcomes, with a 5-year iDFS rate of 82%, compared with 98% for patients who had achieved a pCR. This translated into a hazard ratio for invasive disease in patients with pCRs of 0.14 (P = .011).

This difference occurred despite the study requirement that all patients who did not have pCR after 12 weeks of initial therapy would receive additional chemotherapy.

Looking at the tumor subtype among patients in the paclitaxel-free arm to see whether they could identify predictors of early response, the researchers found a pCR rate of 36.5% among 85 patients with nonbasal tumors, but 0% among 7 patients with basal tumors.

The investigators identified a population of patients whose tumors could be considered nonsensitive to dual HER2 blockade alone: Those with basal tumors, those tumors with low immunohistochemical HER2 expression, and those without an early response to therapy on biopsy 3 weeks into initial therapy. Among 31 of the 92 patients in the dual HER2 arm who met this description, 2 had pCRs, Dr. Harbeck noted.

The 5-year iDFS rate among patients in the dual blockade–only arm with nonsensitive tumors was 79%, compared with 93% for patients with treatment-responsive types, although there were only 13 invasive events total in this arm.

“If we look at the whole trial population, the negative prognostic impact of what we termed nonsensitive tumors was even significant regarding dDFS, with a hazard ratio of about 5,” she said.

‘A consistent theme’

Invited discussant Lisa A. Carey, MD, ScM, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, noted that the trial was underpowered for outcomes, but that results nonetheless suggest that patients with strongly HER2-driven tumors might get comparable benefits from less chemotherapy.

“This trial included only hormone receptor–negative, HER2-positive tumors, and these we know are likely to be HER2-enriched in terms of subtype, about three-quarters of them,”she said.

The previously reported pCR rate of 90% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, with 80% of patients requiring no further chemotherapy, resulted in the excellent 5-year iDFS and dDFS in this group, despite the relatively highly clinical stage, with about 60% of patients having clinical stage 2 or higher tumors, and more than 40% being node positive.

The idea that pCR itself can predict which patients could be spared from more intensive chemotherapy “is starting to look like a consistent theme,” she said.

Dr. Carey pointed out that in the KRISTINE trial comparing the combination of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab with standard chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive stage I-III breast cancer, although the experimental combination was associated with lower pCR rates and worse event-free survival, rates of iDFS/dDFS were virtually identical for patients in both arms who achieved a pCR.

“So the question is can pCR mean that we can either eliminate additional therapy,” she said, noting that the question is currently being addressed prospectively in two clinical trials, COMPASS-pCR and DECRESCENDO.

ADAPT HER2+/HR- is sponsored by F. Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Harbeck disclosed institutional research funding from Roche/Genentech, as well as honoraria and consulting/advising for multiple companies. Dr. Carey disclosed institutional research funding and other relationships with various companies.

It may not be always necessary to approach the treatment of HER2-positive, hormone receptor–negative (HER2+/HR–) early breast cancer with added chemotherapy, survival results of a prospective multicenter randomized trial suggest.

In the ADAPT-HER2+/HR– trial, comparing a de-escalated 12-week neoadjuvant regimen consisting of dual HER2 blockade with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta) with or without weekly paclitaxel, the three-drug regimen was associated with high pathologic complete response(pCR) rates and excellent 5-year survival, irrespective of whether patients received additional chemotherapy, reported Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich.

“Chemotherapy-free regimens are promising in highly sensitive tumors with early response, but future investigation of such chemotherapy-free regimens need to be focused on selected patients, like those with HER2 3+ tumors, non–basal-like tumors, those showing early response to the de-escalated therapy, and those with predictive RNA signatures such as immune signatures,” she said in an oral abstract session during the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting (Abstract 503).

Under the WGS umbrella

The ADAPT HER2+/HR– trial (NCT01779206) is one of several conducted by the West German Study Group (WGS) on therapy for intrinsic breast cancer types.

In this study, 134 patients with HER2-positive, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative tumors with no metastatic disease and good performance status were assigned on a 5:2 basis to neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg for the first cycle followed by 6 mg/kg for subsequent cycles every 3 weeks x 4, plus pertuzumab at a loading dose of 840 mg followed by 420 mg every 3 weeks x 4 (92 patients), or to trastuzumab and pertuzumab at the same dose and schedule plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 once weekly for 12 weeks.

Patients had surgery within 3 weeks of the end of study therapy unless they did not have a histologically confirmed pCR, in which case they went on to receive standard neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery.

Adjuvant therapy was performed according to national guidelines, although patients with a pCR after 12 weeks of study therapy could be spared from adjuvant chemotherapy at the investigator’s discretion.

Patients underwent biopsy at 3 weeks for therapy for early response assessment, defined as either a Ki67 decrease of at least 30% from baseline, or low cellularity (less than 500 invasive tumor cells).

First survival results

The investigators previously reported the primary pCR endpoint from the trial, which showed a rate of 90% after 12 weeks in the three-drug arm, and a “substantial and clinically meaningful” pCR rate of 34% after the trastuzumab plus pertuzumab alone.

At ASCO 2021, Dr. Harbeck reported the first survival data from the trial.

After a median follow-up of 59.9 months, there were no statistically significant differences between trial arms in either overall survival, invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), or distant disease-free survival (dDFS).

The 5-year iDFS rate in the three-drug arm was 98%, compared with 87% for the dual HER2 blockade-only arm, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The 5-year dDFS rates were 98% and 92% respectively. There were only seven dDFS events during follow-up, Dr. Harbeck noted.

There were only six deaths during follow-up, with overall survival rates of 98% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, and 94% in the anti-HER2 antibodies–only arm, a difference of one overall survival event, Dr. Harbeck said.

pCR counts

However, patients who did not have pathologic complete responses at the end of first-line de-escalated therapy had worse outcomes, with a 5-year iDFS rate of 82%, compared with 98% for patients who had achieved a pCR. This translated into a hazard ratio for invasive disease in patients with pCRs of 0.14 (P = .011).

This difference occurred despite the study requirement that all patients who did not have pCR after 12 weeks of initial therapy would receive additional chemotherapy.

Looking at the tumor subtype among patients in the paclitaxel-free arm to see whether they could identify predictors of early response, the researchers found a pCR rate of 36.5% among 85 patients with nonbasal tumors, but 0% among 7 patients with basal tumors.

The investigators identified a population of patients whose tumors could be considered nonsensitive to dual HER2 blockade alone: Those with basal tumors, those tumors with low immunohistochemical HER2 expression, and those without an early response to therapy on biopsy 3 weeks into initial therapy. Among 31 of the 92 patients in the dual HER2 arm who met this description, 2 had pCRs, Dr. Harbeck noted.

The 5-year iDFS rate among patients in the dual blockade–only arm with nonsensitive tumors was 79%, compared with 93% for patients with treatment-responsive types, although there were only 13 invasive events total in this arm.

“If we look at the whole trial population, the negative prognostic impact of what we termed nonsensitive tumors was even significant regarding dDFS, with a hazard ratio of about 5,” she said.

‘A consistent theme’

Invited discussant Lisa A. Carey, MD, ScM, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, noted that the trial was underpowered for outcomes, but that results nonetheless suggest that patients with strongly HER2-driven tumors might get comparable benefits from less chemotherapy.

“This trial included only hormone receptor–negative, HER2-positive tumors, and these we know are likely to be HER2-enriched in terms of subtype, about three-quarters of them,”she said.

The previously reported pCR rate of 90% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, with 80% of patients requiring no further chemotherapy, resulted in the excellent 5-year iDFS and dDFS in this group, despite the relatively highly clinical stage, with about 60% of patients having clinical stage 2 or higher tumors, and more than 40% being node positive.

The idea that pCR itself can predict which patients could be spared from more intensive chemotherapy “is starting to look like a consistent theme,” she said.

Dr. Carey pointed out that in the KRISTINE trial comparing the combination of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab with standard chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive stage I-III breast cancer, although the experimental combination was associated with lower pCR rates and worse event-free survival, rates of iDFS/dDFS were virtually identical for patients in both arms who achieved a pCR.

“So the question is can pCR mean that we can either eliminate additional therapy,” she said, noting that the question is currently being addressed prospectively in two clinical trials, COMPASS-pCR and DECRESCENDO.

ADAPT HER2+/HR- is sponsored by F. Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Harbeck disclosed institutional research funding from Roche/Genentech, as well as honoraria and consulting/advising for multiple companies. Dr. Carey disclosed institutional research funding and other relationships with various companies.

It may not be always necessary to approach the treatment of HER2-positive, hormone receptor–negative (HER2+/HR–) early breast cancer with added chemotherapy, survival results of a prospective multicenter randomized trial suggest.

In the ADAPT-HER2+/HR– trial, comparing a de-escalated 12-week neoadjuvant regimen consisting of dual HER2 blockade with trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta) with or without weekly paclitaxel, the three-drug regimen was associated with high pathologic complete response(pCR) rates and excellent 5-year survival, irrespective of whether patients received additional chemotherapy, reported Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich.

“Chemotherapy-free regimens are promising in highly sensitive tumors with early response, but future investigation of such chemotherapy-free regimens need to be focused on selected patients, like those with HER2 3+ tumors, non–basal-like tumors, those showing early response to the de-escalated therapy, and those with predictive RNA signatures such as immune signatures,” she said in an oral abstract session during the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting (Abstract 503).

Under the WGS umbrella

The ADAPT HER2+/HR– trial (NCT01779206) is one of several conducted by the West German Study Group (WGS) on therapy for intrinsic breast cancer types.

In this study, 134 patients with HER2-positive, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative tumors with no metastatic disease and good performance status were assigned on a 5:2 basis to neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg for the first cycle followed by 6 mg/kg for subsequent cycles every 3 weeks x 4, plus pertuzumab at a loading dose of 840 mg followed by 420 mg every 3 weeks x 4 (92 patients), or to trastuzumab and pertuzumab at the same dose and schedule plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 once weekly for 12 weeks.

Patients had surgery within 3 weeks of the end of study therapy unless they did not have a histologically confirmed pCR, in which case they went on to receive standard neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery.

Adjuvant therapy was performed according to national guidelines, although patients with a pCR after 12 weeks of study therapy could be spared from adjuvant chemotherapy at the investigator’s discretion.

Patients underwent biopsy at 3 weeks for therapy for early response assessment, defined as either a Ki67 decrease of at least 30% from baseline, or low cellularity (less than 500 invasive tumor cells).

First survival results

The investigators previously reported the primary pCR endpoint from the trial, which showed a rate of 90% after 12 weeks in the three-drug arm, and a “substantial and clinically meaningful” pCR rate of 34% after the trastuzumab plus pertuzumab alone.

At ASCO 2021, Dr. Harbeck reported the first survival data from the trial.

After a median follow-up of 59.9 months, there were no statistically significant differences between trial arms in either overall survival, invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), or distant disease-free survival (dDFS).

The 5-year iDFS rate in the three-drug arm was 98%, compared with 87% for the dual HER2 blockade-only arm, a difference that was not statistically significant.

The 5-year dDFS rates were 98% and 92% respectively. There were only seven dDFS events during follow-up, Dr. Harbeck noted.

There were only six deaths during follow-up, with overall survival rates of 98% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, and 94% in the anti-HER2 antibodies–only arm, a difference of one overall survival event, Dr. Harbeck said.

pCR counts

However, patients who did not have pathologic complete responses at the end of first-line de-escalated therapy had worse outcomes, with a 5-year iDFS rate of 82%, compared with 98% for patients who had achieved a pCR. This translated into a hazard ratio for invasive disease in patients with pCRs of 0.14 (P = .011).

This difference occurred despite the study requirement that all patients who did not have pCR after 12 weeks of initial therapy would receive additional chemotherapy.

Looking at the tumor subtype among patients in the paclitaxel-free arm to see whether they could identify predictors of early response, the researchers found a pCR rate of 36.5% among 85 patients with nonbasal tumors, but 0% among 7 patients with basal tumors.

The investigators identified a population of patients whose tumors could be considered nonsensitive to dual HER2 blockade alone: Those with basal tumors, those tumors with low immunohistochemical HER2 expression, and those without an early response to therapy on biopsy 3 weeks into initial therapy. Among 31 of the 92 patients in the dual HER2 arm who met this description, 2 had pCRs, Dr. Harbeck noted.

The 5-year iDFS rate among patients in the dual blockade–only arm with nonsensitive tumors was 79%, compared with 93% for patients with treatment-responsive types, although there were only 13 invasive events total in this arm.

“If we look at the whole trial population, the negative prognostic impact of what we termed nonsensitive tumors was even significant regarding dDFS, with a hazard ratio of about 5,” she said.

‘A consistent theme’

Invited discussant Lisa A. Carey, MD, ScM, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, noted that the trial was underpowered for outcomes, but that results nonetheless suggest that patients with strongly HER2-driven tumors might get comparable benefits from less chemotherapy.

“This trial included only hormone receptor–negative, HER2-positive tumors, and these we know are likely to be HER2-enriched in terms of subtype, about three-quarters of them,”she said.

The previously reported pCR rate of 90% in the paclitaxel-containing arm, with 80% of patients requiring no further chemotherapy, resulted in the excellent 5-year iDFS and dDFS in this group, despite the relatively highly clinical stage, with about 60% of patients having clinical stage 2 or higher tumors, and more than 40% being node positive.

The idea that pCR itself can predict which patients could be spared from more intensive chemotherapy “is starting to look like a consistent theme,” she said.

Dr. Carey pointed out that in the KRISTINE trial comparing the combination of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and pertuzumab with standard chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive stage I-III breast cancer, although the experimental combination was associated with lower pCR rates and worse event-free survival, rates of iDFS/dDFS were virtually identical for patients in both arms who achieved a pCR.

“So the question is can pCR mean that we can either eliminate additional therapy,” she said, noting that the question is currently being addressed prospectively in two clinical trials, COMPASS-pCR and DECRESCENDO.

ADAPT HER2+/HR- is sponsored by F. Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Harbeck disclosed institutional research funding from Roche/Genentech, as well as honoraria and consulting/advising for multiple companies. Dr. Carey disclosed institutional research funding and other relationships with various companies.

FROM ASCO 2021

How to choose the right vaginal moisturizer or lubricant for your patient

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants

Lubricants differ from vaginal moisturizers because they are specifically designed to be used during intercourse to provide short-term relief from vaginal dryness. They may be water-, silicone-, mineral oil-, or plant oil-based. The use of water- and silicone-based lubricants is associated with high satisfaction for intercourse as well as masturbation.14 These products may be particularly beneficial to women whose chief complaint is dyspareunia. In fact, women with dyspareunia report more lubricant use than women without dyspareunia, and the most common reason for lubricant use among these women was to reduce or alleviate pain.15 Overall, women both with and without dyspareunia have a positive perception regarding lubricant use and prefer sexual intercourse that feels more “wet,” and women in their forties have the most positive perception about lubricant use at the time of intercourse compared with other age groups.16 Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that condom-compatible lubricants be used with condoms for menopausal and postmenopausal women.17 Both water-based and silicone-based lubricants may be used with latex condoms, while oil-based lubricants should be avoided as they can degrade the latex condom. While vaginal moisturizers and lubricants technically differ based on use, patients may use one product for both purposes, and some products are marketed as both a moisturizer and lubricant.

Continue to: Providing counsel to patients...

Providing counsel to patients

Patients often seek advice on how to choose vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Understanding the compositions of these products and their scientific evidence is useful when helping patients make informed decisions regarding their pelvic health. Most commercially available lubricants are either water- or silicone- based. In one study comparing these two types of lubricants, water-based lubricants were associated with fewer genital symptoms than silicone-based products.14 Women may want to use a natural or organic product and may prefer plant-based oils such as coconut oil or olive oil. Patients should be counseled that latex condoms are not compatible with petroleum-, mineral oil- or plant oil-based lubricants.

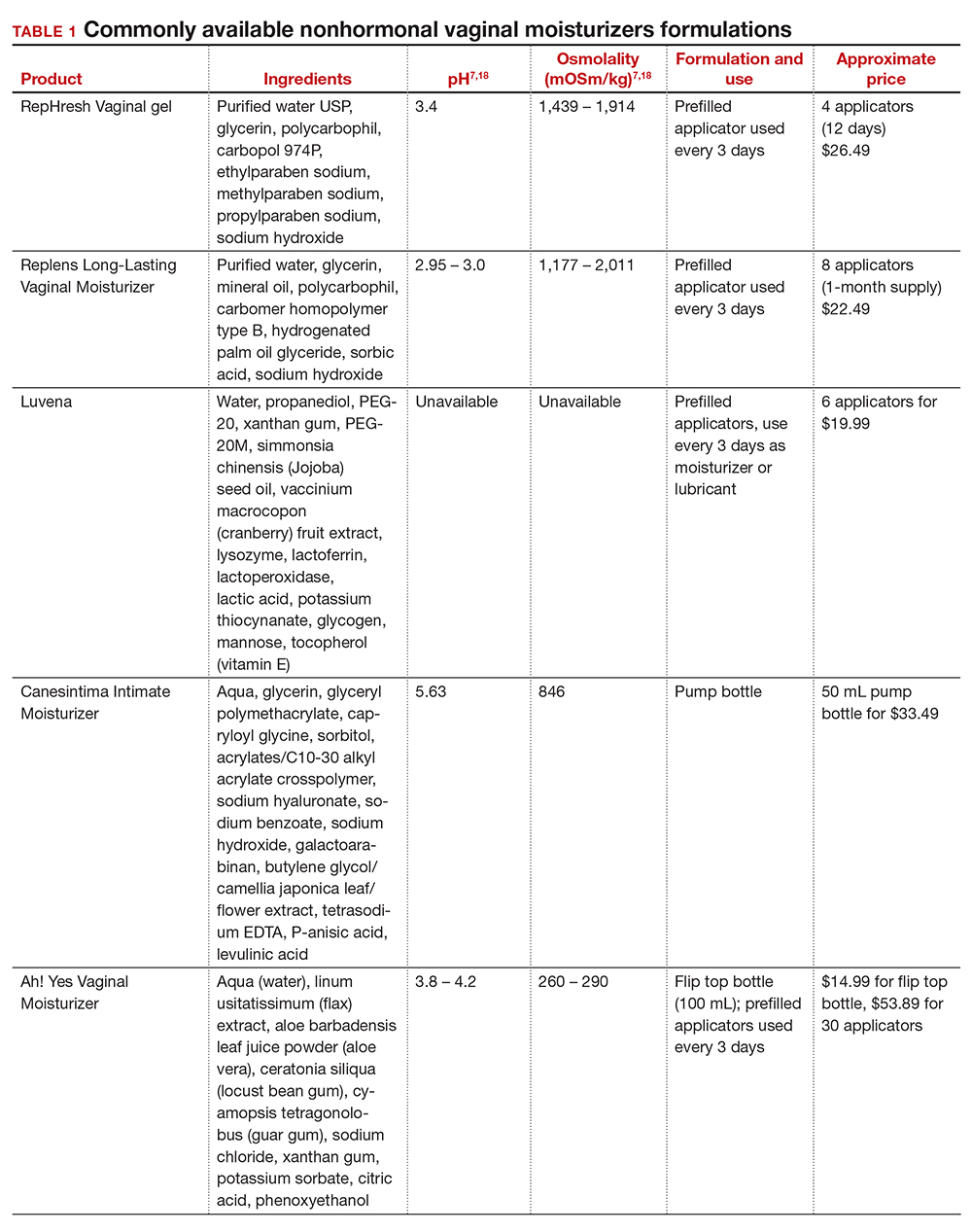

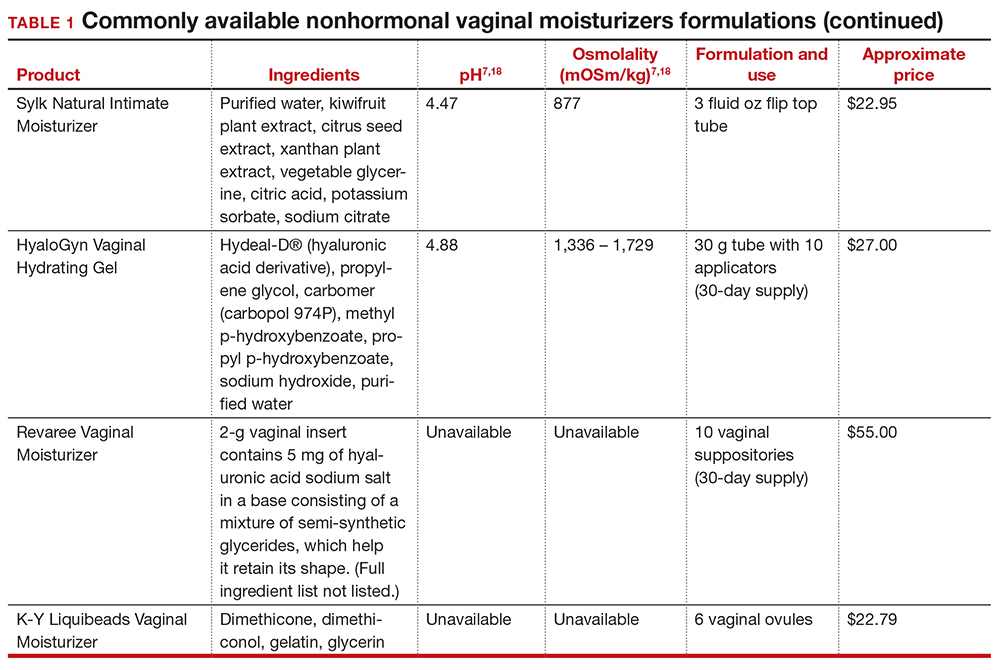

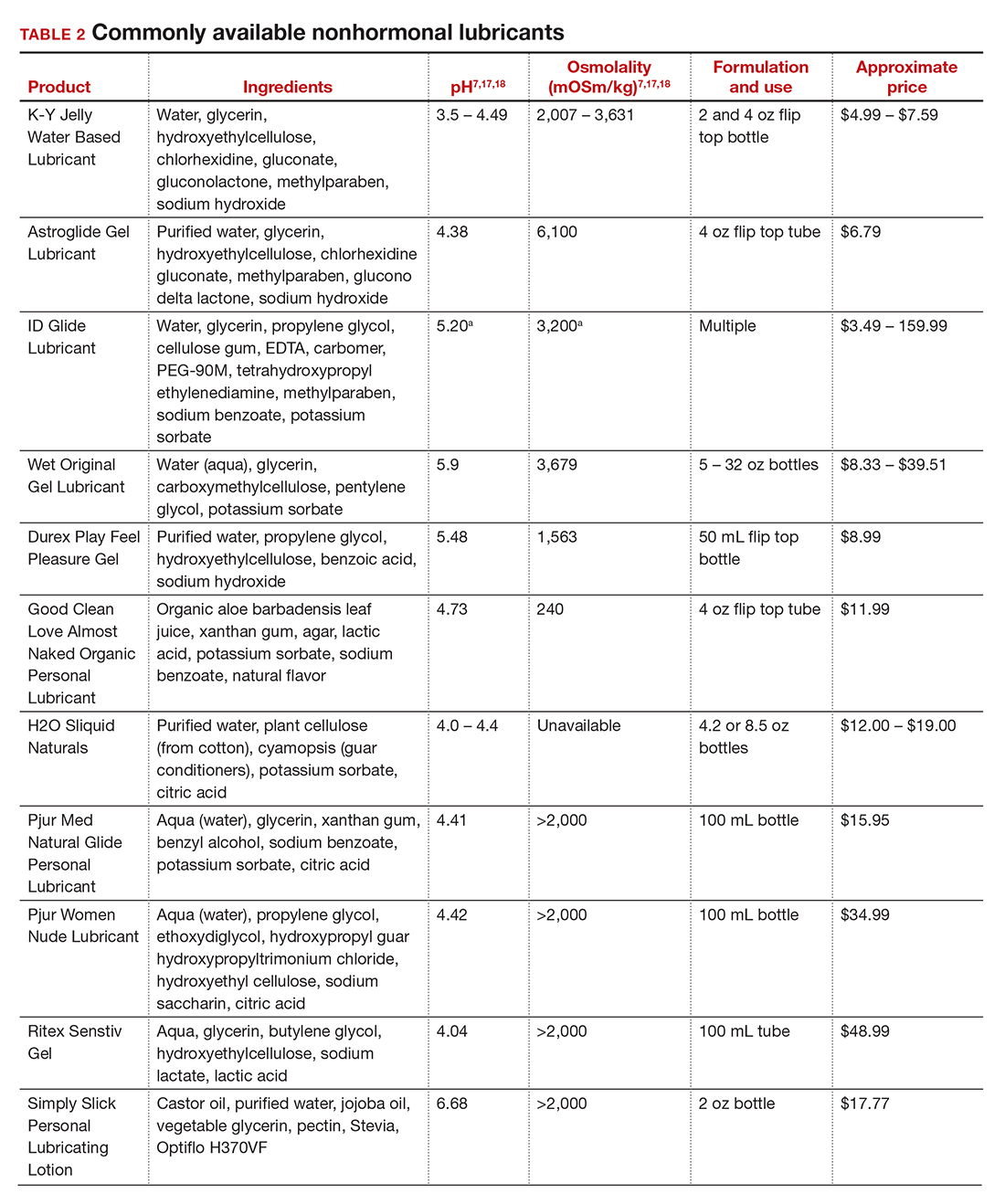

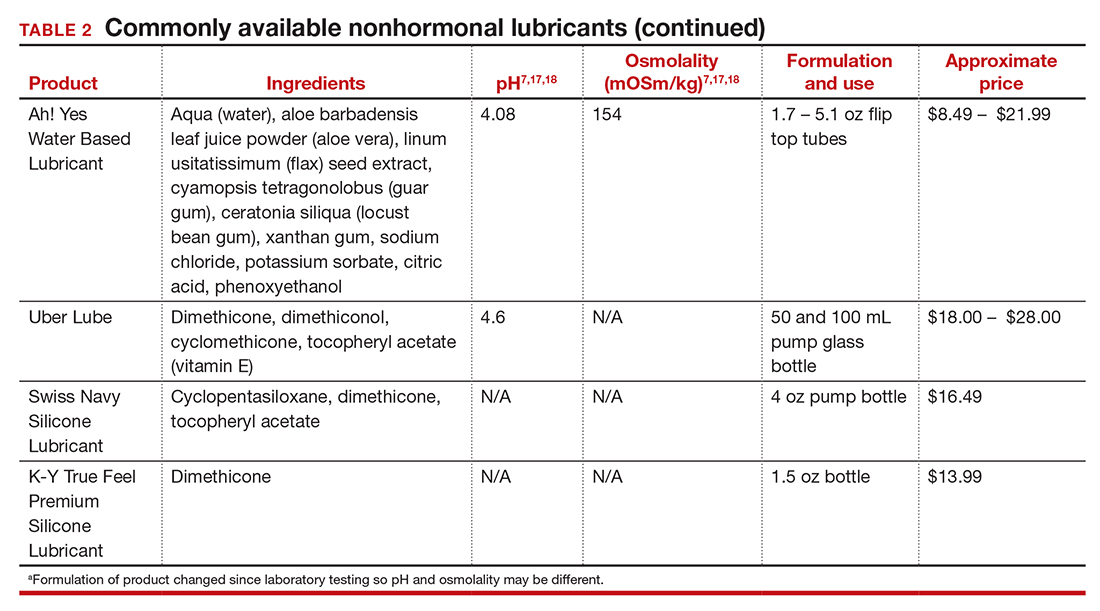

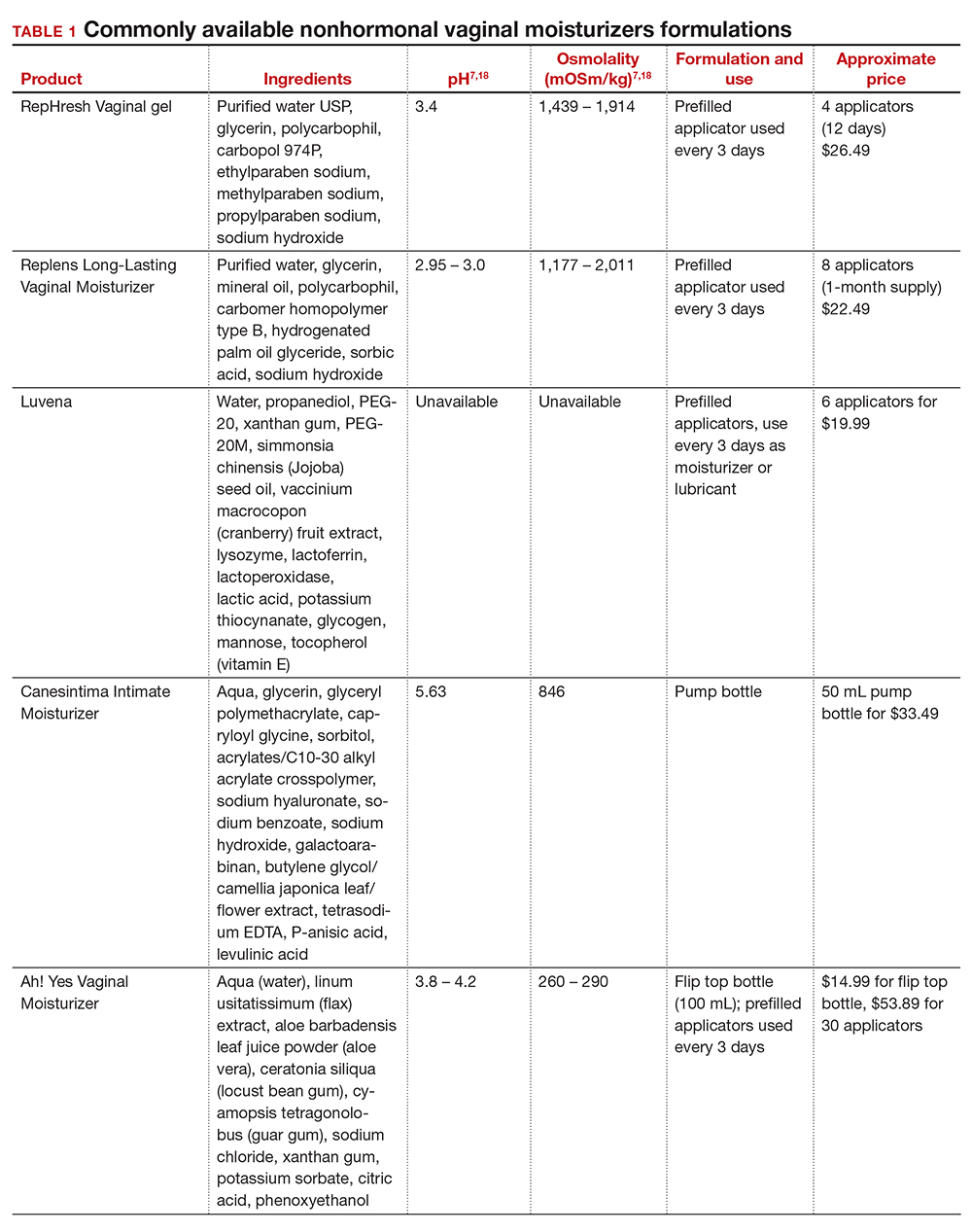

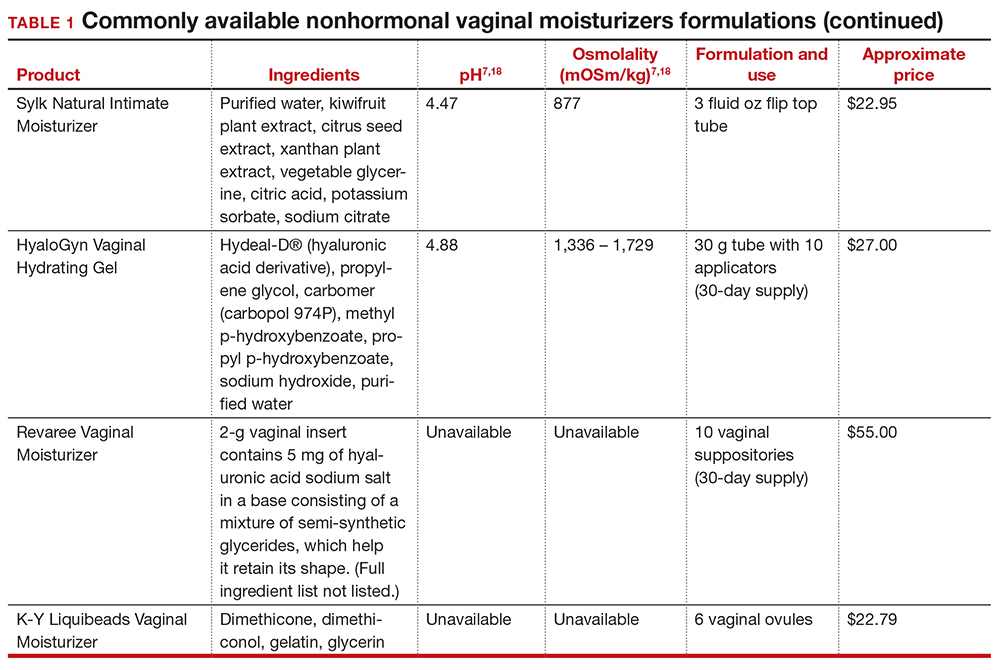

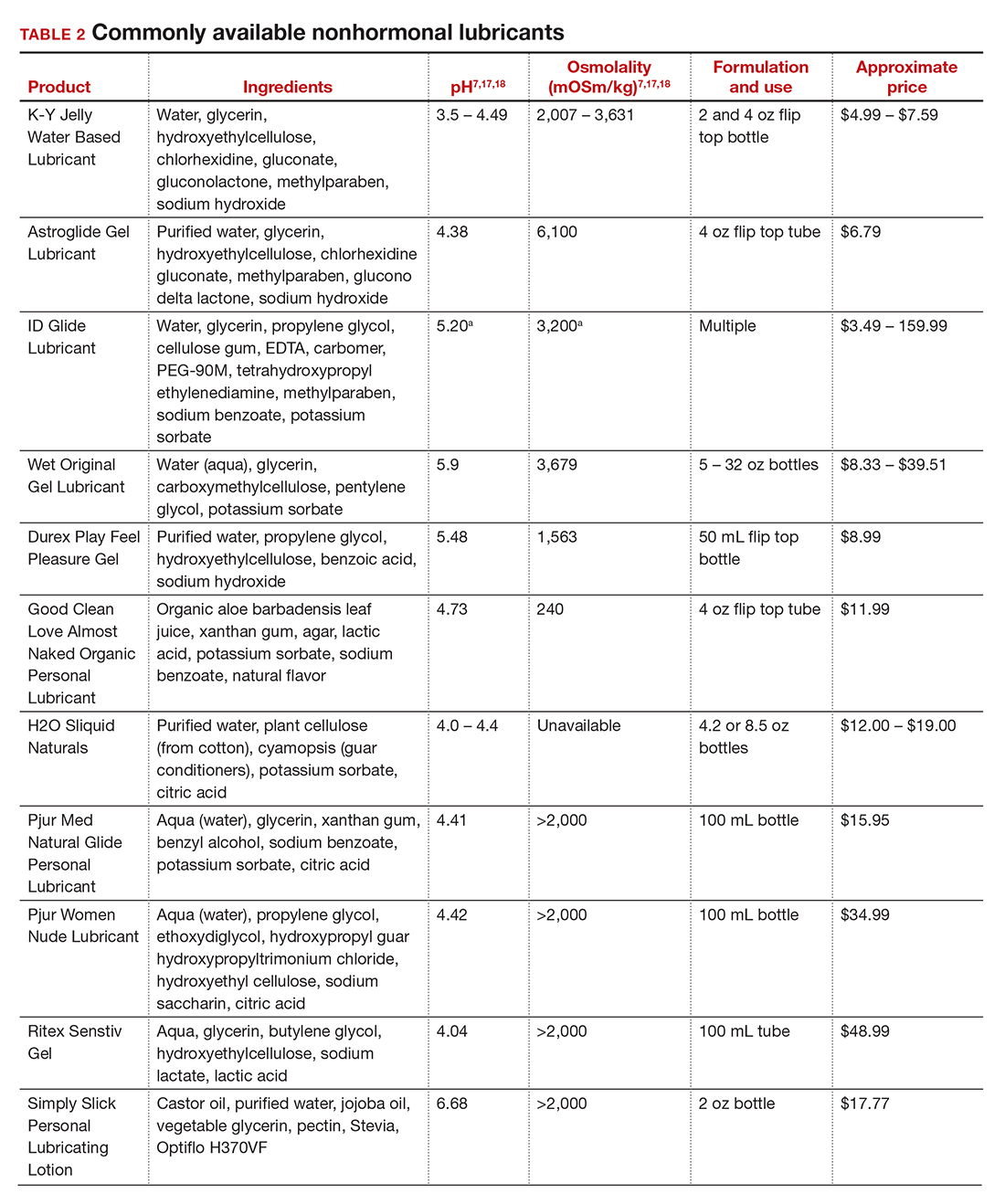

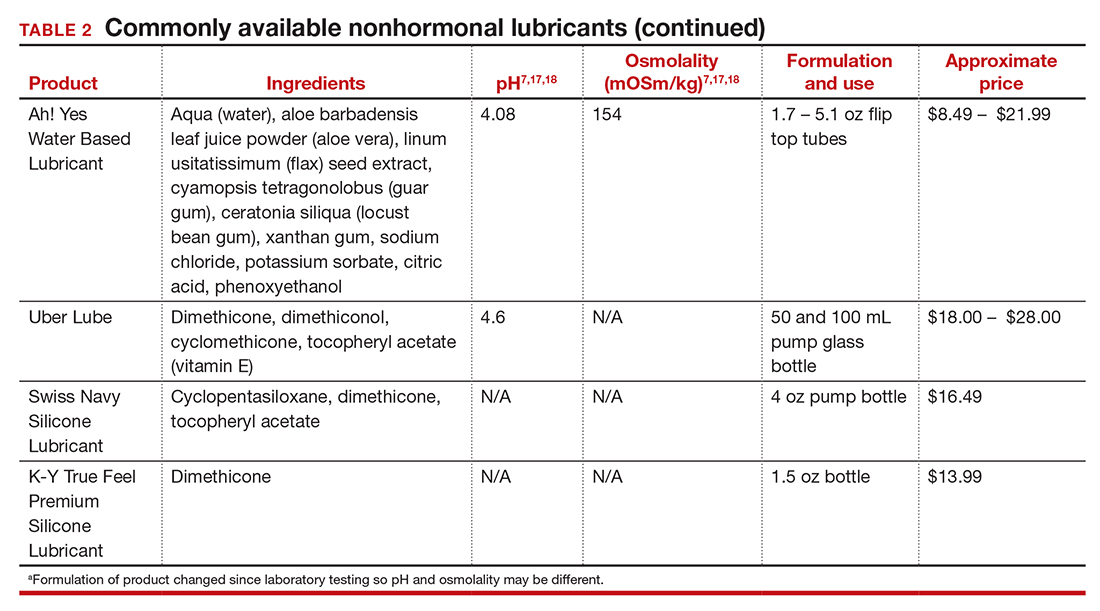

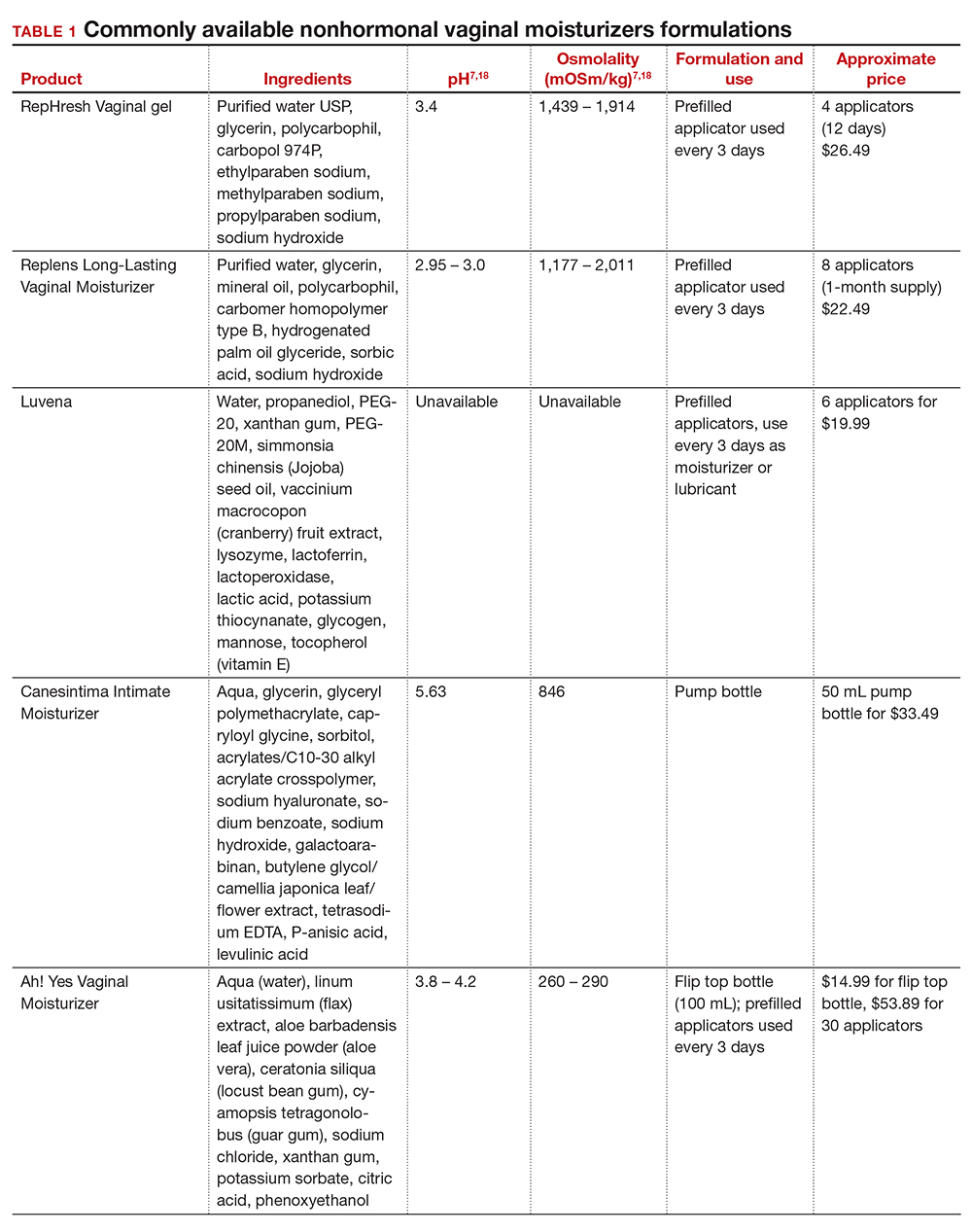

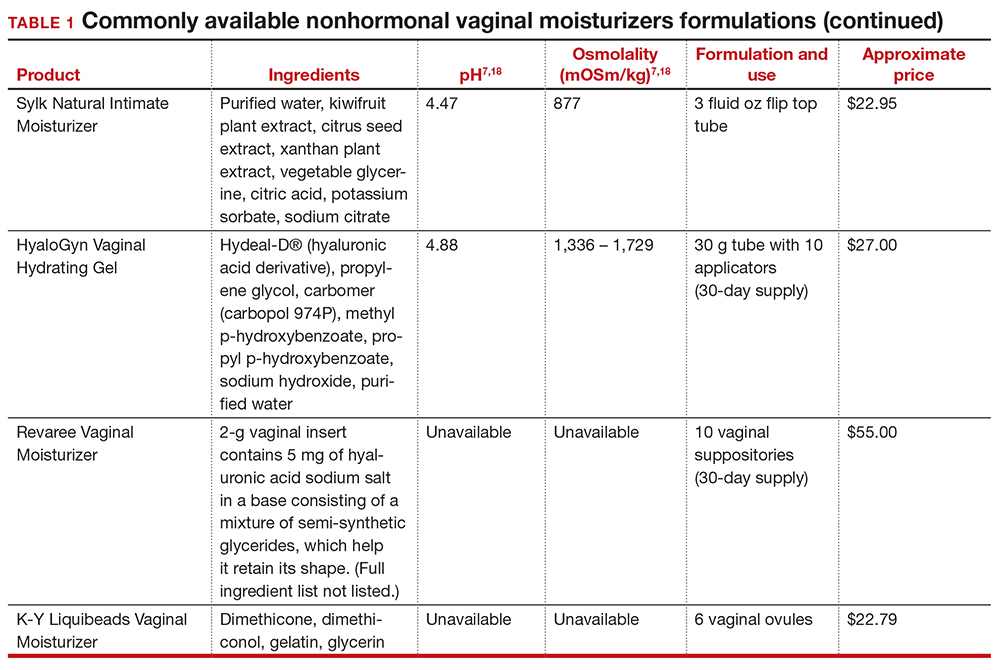

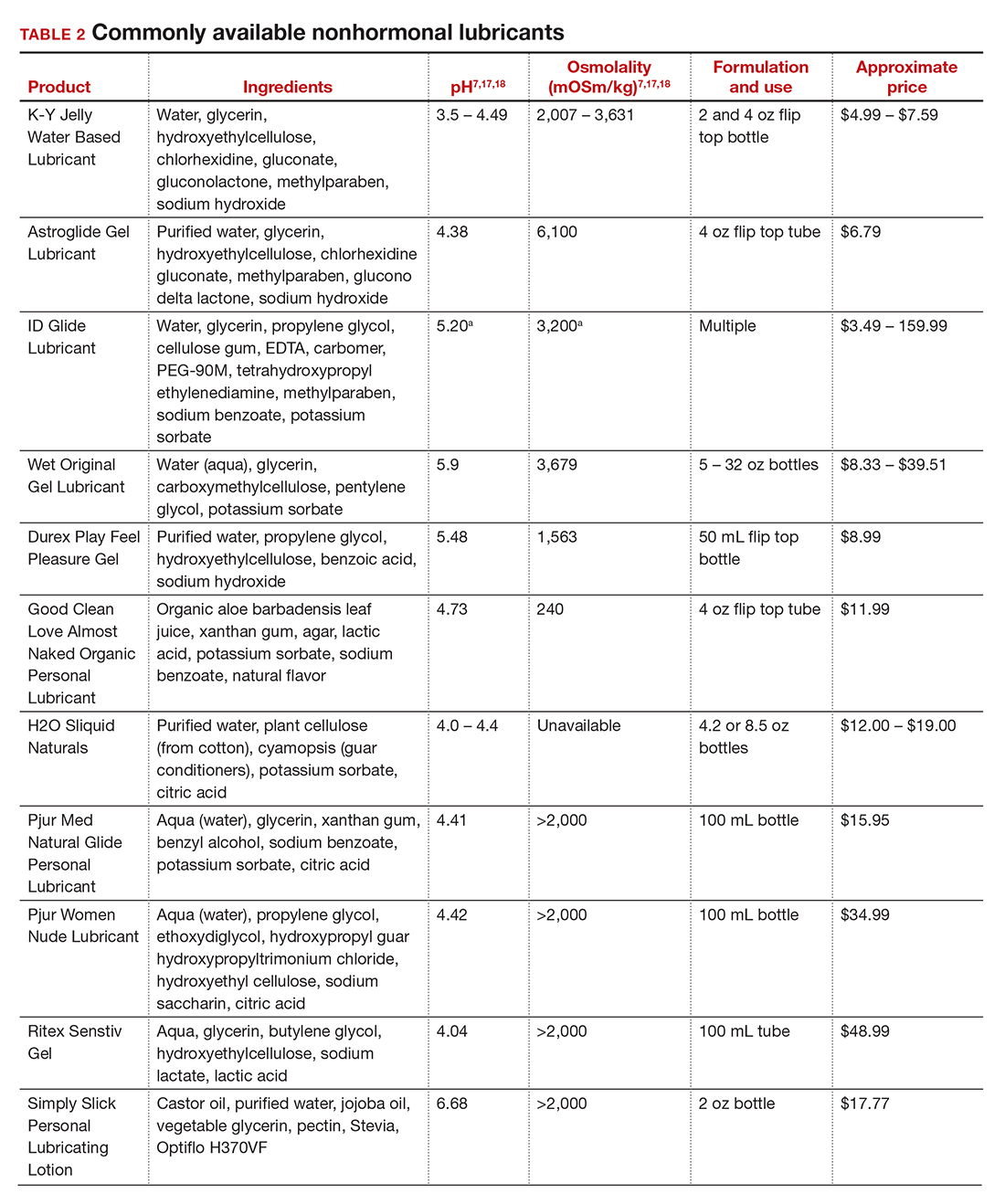

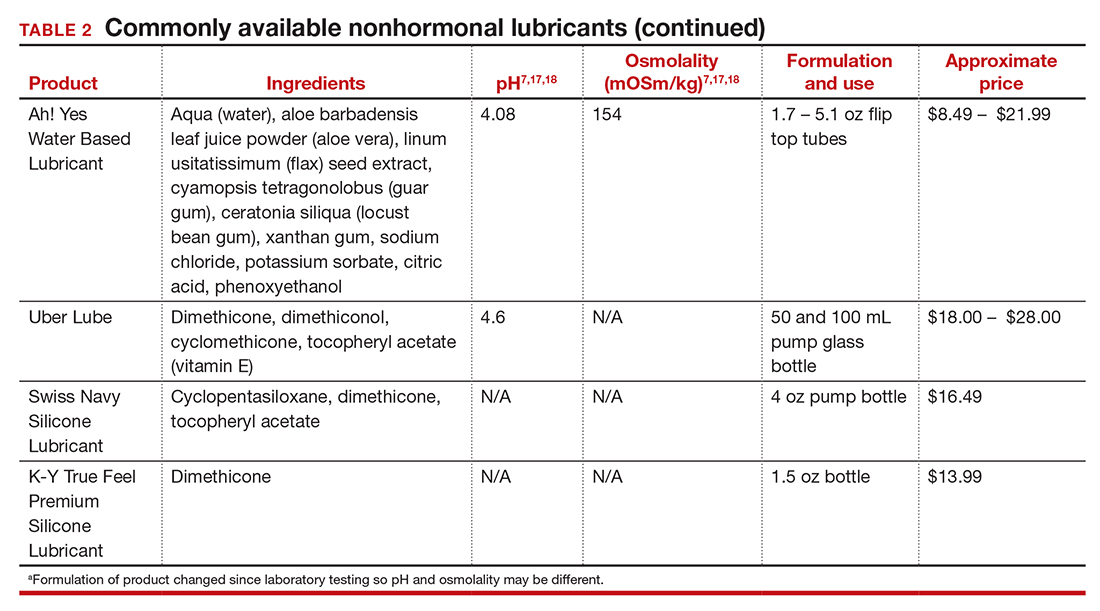

In our practice, we generally recommend silicone-based lubricants, as they are readily available and compatible with latex condoms and generally require a smaller amount than water-based lubricants. They tend to be more expensive than water-based lubricants. For vaginal moisturizers, we often recommend commercially available formulations that can be purchased at local pharmacies or drug stores. However, a patient may need to try different lubricants and moisturizers in order to find a preferred product. We have included in TABLES 1 and 27,17,18 a list of commercially available vaginal moisturizers and lubricants with ingredient list, pH, osmolality, common formulation, and cost when available, which has been compiled from WHO and published research data to help guide patient counseling.

The effects of additives

Water-based moisturizers and lubricants may contain many ingredients, such as glycerols, fragrance, flavors, sweeteners, warming or cooling agents, buffering solutions, parabens and other preservatives, and numbing agents. These substances are added to water-based products to prolong water content, alter viscosity, alter pH, achieve certain sensations, and prevent bacterial contamination.7 The addition of these substances, however, will alter osmolality and pH balance of the product, which may be of clinical consequence. Silicone- or oil-based products do not contain water and therefore do not have a pH or an osmolality value.

Hyperosmolar formulations can theoretically injure epithelial tissue. In vitro studies have shown that hyperosmotic vaginal products can induce mild to moderate irritation, while very hyperosmolar formulations can induce severe irritation and tissue damage to vaginal epithelial and cervical cells.19,20 The WHO recommends that the osmolality of a vaginal product not exceed 380 mOsm/kg, but very few commercially available products meet these criteria so, clinically, the threshold is 1,200 mOsm/kg.17 It should be noted that most commercially available products exceed the 1,200 mOsm/kg threshold. Vaginal products may be a cause for vaginal irritation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The normal vaginal pH is 3.8–4.5, and vaginal products should be pH balanced to this range. The exact role of pH in these products remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, products with a pH of 3 or lower are not recommended.18 Concerns about osmolality and pH remain theoretical, as a study of 12 commercially available lubricants of varying osmolality and pH found no cytotoxic effect in vivo.18

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants contain many inactive ingredients, the most controversial of which are parabens. These substances are used in many cosmetic products as preservatives and are weakly estrogenic. These substances have been found in breast cancer tissue, but their possible role as a carcinogen remains uncertain.21,22 Nonetheless, the use of paraben-containing products is not recommended for women who have a history of hormonally-driven cancer or who are at high risk for developing cancer.7 Many lubricants contain glycerols (glycerol, glycerine, and propylene glycol) to alter viscosity or alter the water properties. The WHO recommends limits on the content of glycerols in these products.17 Glycerols have been associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 11.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–70.27), and can serve as a food source for candida species, possibly increasing risk of yeast infections.7,23 Additionally, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may contain preservatives such as chlorhexidine, which can disrupt normal vaginal flora and may cause tissue irritation.7

Continue to: Common concerns to be aware of...

Common concerns to be aware of

Women using vaginal products may be concerned about adverse effects, such as worsening vaginal irritation or infection. Vaginal moisturizers have not been shown to have increased risk of adverse effects compared with vaginal estrogens.9,10 In vitro studies have shown that vaginal moisturizers and lubricants inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli but may also inhibit Lactobacillus crispatus.24 Clinically, vaginal moisturizers have been shown to improve signs of bacterial vaginosis and have even been used to treat bacterial vaginosis.25,26 A study of commercially available vaginal lubricants inhibited the growth of L crispatus, which may predispose to irritation and infection.27 Nonetheless, the effect of the vaginal products on the vaginal microbiome and vaginal tissue remains poorly studied. Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, while often helpful for patients, also can potentially cause irritation or predispose to infections. Providers should consider this when evaluating patients for new onset vaginal symptoms after starting vaginal products.

Bottom line

Vaginal products such as moisturizers and lubricants are often effective treatment options for women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause and may be first-line treatment options, especially for women who may wish to avoid estrogen-containing products. Vaginal moisturizers can be recommended to any women experiencing vaginal irritation due to vaginal dryness while vaginal lubricants should be recommended to sexually active women who experience dyspareunia. Clinicians need to be aware of the formulations of these products and possible side effects in order to appropriately counsel patients. ●

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas. 2005;52(suppl 1):S46-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.014.

- Crandall C, Peterson L, Ganz PA, et al. Association of breast cancer and its therapy with menopause-related symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11:519-530. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000117061.40493.ab.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistant Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78.

- Faubion S, Larkin L, Stuenkel C, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendation from The North American Menopause Society and the International Society for the Study for Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001121.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12427.

- Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric. 2016;19:151-116. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1124259.

- Van der Lakk JAWN, de Bie LMT, de Leeuw H, et al. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerized cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446-451. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446.

- Nachtigall LE. Comparitive study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:178-180. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7.

- Bygdeman M, Swahn ML. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:259-263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00955-8.

- Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, et al. Efficacy of vaginal estradiol or vaginal moisturizer vs placebo for treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:681-690. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0116.

- Chen J, Geng L, Song X, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1575-1584. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12125.

- Jokar A, Davari T, Asadi N, et al. Comparison of the hyaluronic acid vaginal cream and conjugated estrogen used in treatment of vaginal atrophy of menopause women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. IJCBNM. 2016;4:69-78.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, et al. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: a prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:202-212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x.

- Sutton KS, Boyer SC, Goldfinger C, et al. To lube or not to lube: experiences and perceptions of lubricant use in women with and without dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2012;9:240-250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02543.x.

- Jozkowski KN, Herbenick D, Schick V, et al. Women’s perceptions about lubricant use and vaginal wetness during sexual activity. J Sex Med. 2013;10:484-492. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12022.

- World Health Organization. Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO /UNFPA/FHI360 advisory note. 2012. https://www.who. int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/rhr12_33/en/. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira de Oliveira A, et al. Characterization of commercially available vaginal lubricants: a safety perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;6:530-542. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics6030530.

- Adriaens E, Remon JP. Mucosal irritation potential of personal lubricants relates to product osmolality as detected by the slug mucosal irritation assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:512-516. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644669.

- Dezzuti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048328.

- Harvey PW, Everett DJ. Significance of the detection of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004:24:1-4. doi: 10.1002/jat.957.

- Darbre PD, Alijarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumous. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13. doi: 10.1002/jat.958.

- Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, et al. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:297-302. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040592.

- Hung KJ, Hudson P, Bergerat A, et al. Effect of commercial vaginal products on the growth of uropathogenic and commensal vaginal bacteria. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7625.

- Wu JP, Fielding SL, Fiscell K. The effect of the polycarbophil gel (Replens) on bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.01.007.

- Fiorelli A, Molteni B, Milani M. Successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis with a polycarbophil-carbopol acidic vaginal gel: results from a randomized double-bling, placebo controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:202-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.10.011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v24i0.19703.

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants

Lubricants differ from vaginal moisturizers because they are specifically designed to be used during intercourse to provide short-term relief from vaginal dryness. They may be water-, silicone-, mineral oil-, or plant oil-based. The use of water- and silicone-based lubricants is associated with high satisfaction for intercourse as well as masturbation.14 These products may be particularly beneficial to women whose chief complaint is dyspareunia. In fact, women with dyspareunia report more lubricant use than women without dyspareunia, and the most common reason for lubricant use among these women was to reduce or alleviate pain.15 Overall, women both with and without dyspareunia have a positive perception regarding lubricant use and prefer sexual intercourse that feels more “wet,” and women in their forties have the most positive perception about lubricant use at the time of intercourse compared with other age groups.16 Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that condom-compatible lubricants be used with condoms for menopausal and postmenopausal women.17 Both water-based and silicone-based lubricants may be used with latex condoms, while oil-based lubricants should be avoided as they can degrade the latex condom. While vaginal moisturizers and lubricants technically differ based on use, patients may use one product for both purposes, and some products are marketed as both a moisturizer and lubricant.

Continue to: Providing counsel to patients...

Providing counsel to patients

Patients often seek advice on how to choose vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Understanding the compositions of these products and their scientific evidence is useful when helping patients make informed decisions regarding their pelvic health. Most commercially available lubricants are either water- or silicone- based. In one study comparing these two types of lubricants, water-based lubricants were associated with fewer genital symptoms than silicone-based products.14 Women may want to use a natural or organic product and may prefer plant-based oils such as coconut oil or olive oil. Patients should be counseled that latex condoms are not compatible with petroleum-, mineral oil- or plant oil-based lubricants.

In our practice, we generally recommend silicone-based lubricants, as they are readily available and compatible with latex condoms and generally require a smaller amount than water-based lubricants. They tend to be more expensive than water-based lubricants. For vaginal moisturizers, we often recommend commercially available formulations that can be purchased at local pharmacies or drug stores. However, a patient may need to try different lubricants and moisturizers in order to find a preferred product. We have included in TABLES 1 and 27,17,18 a list of commercially available vaginal moisturizers and lubricants with ingredient list, pH, osmolality, common formulation, and cost when available, which has been compiled from WHO and published research data to help guide patient counseling.

The effects of additives

Water-based moisturizers and lubricants may contain many ingredients, such as glycerols, fragrance, flavors, sweeteners, warming or cooling agents, buffering solutions, parabens and other preservatives, and numbing agents. These substances are added to water-based products to prolong water content, alter viscosity, alter pH, achieve certain sensations, and prevent bacterial contamination.7 The addition of these substances, however, will alter osmolality and pH balance of the product, which may be of clinical consequence. Silicone- or oil-based products do not contain water and therefore do not have a pH or an osmolality value.

Hyperosmolar formulations can theoretically injure epithelial tissue. In vitro studies have shown that hyperosmotic vaginal products can induce mild to moderate irritation, while very hyperosmolar formulations can induce severe irritation and tissue damage to vaginal epithelial and cervical cells.19,20 The WHO recommends that the osmolality of a vaginal product not exceed 380 mOsm/kg, but very few commercially available products meet these criteria so, clinically, the threshold is 1,200 mOsm/kg.17 It should be noted that most commercially available products exceed the 1,200 mOsm/kg threshold. Vaginal products may be a cause for vaginal irritation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The normal vaginal pH is 3.8–4.5, and vaginal products should be pH balanced to this range. The exact role of pH in these products remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, products with a pH of 3 or lower are not recommended.18 Concerns about osmolality and pH remain theoretical, as a study of 12 commercially available lubricants of varying osmolality and pH found no cytotoxic effect in vivo.18

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants contain many inactive ingredients, the most controversial of which are parabens. These substances are used in many cosmetic products as preservatives and are weakly estrogenic. These substances have been found in breast cancer tissue, but their possible role as a carcinogen remains uncertain.21,22 Nonetheless, the use of paraben-containing products is not recommended for women who have a history of hormonally-driven cancer or who are at high risk for developing cancer.7 Many lubricants contain glycerols (glycerol, glycerine, and propylene glycol) to alter viscosity or alter the water properties. The WHO recommends limits on the content of glycerols in these products.17 Glycerols have been associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 11.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–70.27), and can serve as a food source for candida species, possibly increasing risk of yeast infections.7,23 Additionally, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may contain preservatives such as chlorhexidine, which can disrupt normal vaginal flora and may cause tissue irritation.7

Continue to: Common concerns to be aware of...

Common concerns to be aware of

Women using vaginal products may be concerned about adverse effects, such as worsening vaginal irritation or infection. Vaginal moisturizers have not been shown to have increased risk of adverse effects compared with vaginal estrogens.9,10 In vitro studies have shown that vaginal moisturizers and lubricants inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli but may also inhibit Lactobacillus crispatus.24 Clinically, vaginal moisturizers have been shown to improve signs of bacterial vaginosis and have even been used to treat bacterial vaginosis.25,26 A study of commercially available vaginal lubricants inhibited the growth of L crispatus, which may predispose to irritation and infection.27 Nonetheless, the effect of the vaginal products on the vaginal microbiome and vaginal tissue remains poorly studied. Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, while often helpful for patients, also can potentially cause irritation or predispose to infections. Providers should consider this when evaluating patients for new onset vaginal symptoms after starting vaginal products.

Bottom line

Vaginal products such as moisturizers and lubricants are often effective treatment options for women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause and may be first-line treatment options, especially for women who may wish to avoid estrogen-containing products. Vaginal moisturizers can be recommended to any women experiencing vaginal irritation due to vaginal dryness while vaginal lubricants should be recommended to sexually active women who experience dyspareunia. Clinicians need to be aware of the formulations of these products and possible side effects in order to appropriately counsel patients. ●

Vaginal dryness, encompassed in the modern term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 40% of menopausal women and up to 60% of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors.1,2 Premenopausal women also can have vulvovaginal dryness while breastfeeding (lactational amenorrhea) and while taking low-dose contraceptives.3 Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are the first-line treatment options for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and GSM.4,5 In fact, approximately two-thirds of women have reported using a vaginal lubricant in their lifetime.6 Despite such ubiquitous use, many health care providers and patients have questions about the difference between vaginal moisturizers and lubricants and how to best choose a product.

Vaginal moisturizers

Vaginal moisturizers are designed to rehydrate the vaginal epithelium. Much like facial or skin moisturizers, they are intended to be applied regularly, every 2 to 3 days, but may be applied more often depending on the severity of symptoms. Vaginal moisturizers work by increasing the fluid content of the vaginal tissue and by lowering the vaginal pH to mimic that of natural vaginal secretions. Vaginal moisturizers are typically water based and use polymers to hydrate tissues.7 They change cell morphology but do not change vaginal maturation, indicating that they bring water to the tissue but do not shift the balance between superficial and basal cells and do not increase vaginal epithelial thickness as seen with vaginal estrogen.8 Vaginal moisturizers also have been found to be a safe alternative to vaginal estrogen therapy and may improve markers of vaginal health, including vaginal moisture, vaginal fluid volume, vaginal elasticity, and premenopausal pH.9 Commercially available vaginal moisturizers have been shown to be as effective as vaginal estrogens in reducing vaginal symptoms such as itching, irritation, and dyspareunia, but some caution should be taken when interpreting these results as neither vaginal moisturizer nor vaginal estrogen tablet were more effective than placebo in a recent randomized controlled trial.10,11 Small studies on hyaluronic acid have shown efficacy for the treatment of vaginal dryness.12,13 Hyaluronic acid is commercially available as a vaginal suppository ovule and as a liquid. It may also be obtained from a reliable compounding pharmacy. Vaginal suppository ovules may be a preferable formulation for women who find the liquids messy or cumbersome to apply.

Lubricants

Lubricants differ from vaginal moisturizers because they are specifically designed to be used during intercourse to provide short-term relief from vaginal dryness. They may be water-, silicone-, mineral oil-, or plant oil-based. The use of water- and silicone-based lubricants is associated with high satisfaction for intercourse as well as masturbation.14 These products may be particularly beneficial to women whose chief complaint is dyspareunia. In fact, women with dyspareunia report more lubricant use than women without dyspareunia, and the most common reason for lubricant use among these women was to reduce or alleviate pain.15 Overall, women both with and without dyspareunia have a positive perception regarding lubricant use and prefer sexual intercourse that feels more “wet,” and women in their forties have the most positive perception about lubricant use at the time of intercourse compared with other age groups.16 Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that condom-compatible lubricants be used with condoms for menopausal and postmenopausal women.17 Both water-based and silicone-based lubricants may be used with latex condoms, while oil-based lubricants should be avoided as they can degrade the latex condom. While vaginal moisturizers and lubricants technically differ based on use, patients may use one product for both purposes, and some products are marketed as both a moisturizer and lubricant.

Continue to: Providing counsel to patients...

Providing counsel to patients

Patients often seek advice on how to choose vaginal moisturizers and lubricants. Understanding the compositions of these products and their scientific evidence is useful when helping patients make informed decisions regarding their pelvic health. Most commercially available lubricants are either water- or silicone- based. In one study comparing these two types of lubricants, water-based lubricants were associated with fewer genital symptoms than silicone-based products.14 Women may want to use a natural or organic product and may prefer plant-based oils such as coconut oil or olive oil. Patients should be counseled that latex condoms are not compatible with petroleum-, mineral oil- or plant oil-based lubricants.

In our practice, we generally recommend silicone-based lubricants, as they are readily available and compatible with latex condoms and generally require a smaller amount than water-based lubricants. They tend to be more expensive than water-based lubricants. For vaginal moisturizers, we often recommend commercially available formulations that can be purchased at local pharmacies or drug stores. However, a patient may need to try different lubricants and moisturizers in order to find a preferred product. We have included in TABLES 1 and 27,17,18 a list of commercially available vaginal moisturizers and lubricants with ingredient list, pH, osmolality, common formulation, and cost when available, which has been compiled from WHO and published research data to help guide patient counseling.

The effects of additives

Water-based moisturizers and lubricants may contain many ingredients, such as glycerols, fragrance, flavors, sweeteners, warming or cooling agents, buffering solutions, parabens and other preservatives, and numbing agents. These substances are added to water-based products to prolong water content, alter viscosity, alter pH, achieve certain sensations, and prevent bacterial contamination.7 The addition of these substances, however, will alter osmolality and pH balance of the product, which may be of clinical consequence. Silicone- or oil-based products do not contain water and therefore do not have a pH or an osmolality value.

Hyperosmolar formulations can theoretically injure epithelial tissue. In vitro studies have shown that hyperosmotic vaginal products can induce mild to moderate irritation, while very hyperosmolar formulations can induce severe irritation and tissue damage to vaginal epithelial and cervical cells.19,20 The WHO recommends that the osmolality of a vaginal product not exceed 380 mOsm/kg, but very few commercially available products meet these criteria so, clinically, the threshold is 1,200 mOsm/kg.17 It should be noted that most commercially available products exceed the 1,200 mOsm/kg threshold. Vaginal products may be a cause for vaginal irritation and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The normal vaginal pH is 3.8–4.5, and vaginal products should be pH balanced to this range. The exact role of pH in these products remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, products with a pH of 3 or lower are not recommended.18 Concerns about osmolality and pH remain theoretical, as a study of 12 commercially available lubricants of varying osmolality and pH found no cytotoxic effect in vivo.18

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants contain many inactive ingredients, the most controversial of which are parabens. These substances are used in many cosmetic products as preservatives and are weakly estrogenic. These substances have been found in breast cancer tissue, but their possible role as a carcinogen remains uncertain.21,22 Nonetheless, the use of paraben-containing products is not recommended for women who have a history of hormonally-driven cancer or who are at high risk for developing cancer.7 Many lubricants contain glycerols (glycerol, glycerine, and propylene glycol) to alter viscosity or alter the water properties. The WHO recommends limits on the content of glycerols in these products.17 Glycerols have been associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 11.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.96–70.27), and can serve as a food source for candida species, possibly increasing risk of yeast infections.7,23 Additionally, vaginal moisturizers and lubricants may contain preservatives such as chlorhexidine, which can disrupt normal vaginal flora and may cause tissue irritation.7

Continue to: Common concerns to be aware of...

Common concerns to be aware of

Women using vaginal products may be concerned about adverse effects, such as worsening vaginal irritation or infection. Vaginal moisturizers have not been shown to have increased risk of adverse effects compared with vaginal estrogens.9,10 In vitro studies have shown that vaginal moisturizers and lubricants inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli but may also inhibit Lactobacillus crispatus.24 Clinically, vaginal moisturizers have been shown to improve signs of bacterial vaginosis and have even been used to treat bacterial vaginosis.25,26 A study of commercially available vaginal lubricants inhibited the growth of L crispatus, which may predispose to irritation and infection.27 Nonetheless, the effect of the vaginal products on the vaginal microbiome and vaginal tissue remains poorly studied. Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, while often helpful for patients, also can potentially cause irritation or predispose to infections. Providers should consider this when evaluating patients for new onset vaginal symptoms after starting vaginal products.

Bottom line

Vaginal products such as moisturizers and lubricants are often effective treatment options for women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause and may be first-line treatment options, especially for women who may wish to avoid estrogen-containing products. Vaginal moisturizers can be recommended to any women experiencing vaginal irritation due to vaginal dryness while vaginal lubricants should be recommended to sexually active women who experience dyspareunia. Clinicians need to be aware of the formulations of these products and possible side effects in order to appropriately counsel patients. ●

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas. 2005;52(suppl 1):S46-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.014.

- Crandall C, Peterson L, Ganz PA, et al. Association of breast cancer and its therapy with menopause-related symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11:519-530. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000117061.40493.ab.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistant Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78.

- Faubion S, Larkin L, Stuenkel C, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendation from The North American Menopause Society and the International Society for the Study for Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001121.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12427.

- Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric. 2016;19:151-116. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1124259.

- Van der Lakk JAWN, de Bie LMT, de Leeuw H, et al. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerized cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446-451. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446.

- Nachtigall LE. Comparitive study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:178-180. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7.

- Bygdeman M, Swahn ML. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:259-263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00955-8.

- Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, et al. Efficacy of vaginal estradiol or vaginal moisturizer vs placebo for treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:681-690. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0116.

- Chen J, Geng L, Song X, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1575-1584. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12125.

- Jokar A, Davari T, Asadi N, et al. Comparison of the hyaluronic acid vaginal cream and conjugated estrogen used in treatment of vaginal atrophy of menopause women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. IJCBNM. 2016;4:69-78.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, et al. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: a prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:202-212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x.

- Sutton KS, Boyer SC, Goldfinger C, et al. To lube or not to lube: experiences and perceptions of lubricant use in women with and without dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2012;9:240-250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02543.x.

- Jozkowski KN, Herbenick D, Schick V, et al. Women’s perceptions about lubricant use and vaginal wetness during sexual activity. J Sex Med. 2013;10:484-492. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12022.

- World Health Organization. Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO /UNFPA/FHI360 advisory note. 2012. https://www.who. int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/rhr12_33/en/. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira de Oliveira A, et al. Characterization of commercially available vaginal lubricants: a safety perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;6:530-542. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics6030530.

- Adriaens E, Remon JP. Mucosal irritation potential of personal lubricants relates to product osmolality as detected by the slug mucosal irritation assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:512-516. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644669.

- Dezzuti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048328.

- Harvey PW, Everett DJ. Significance of the detection of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004:24:1-4. doi: 10.1002/jat.957.

- Darbre PD, Alijarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumous. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13. doi: 10.1002/jat.958.

- Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, et al. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:297-302. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040592.

- Hung KJ, Hudson P, Bergerat A, et al. Effect of commercial vaginal products on the growth of uropathogenic and commensal vaginal bacteria. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7625.

- Wu JP, Fielding SL, Fiscell K. The effect of the polycarbophil gel (Replens) on bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.01.007.

- Fiorelli A, Molteni B, Milani M. Successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis with a polycarbophil-carbopol acidic vaginal gel: results from a randomized double-bling, placebo controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:202-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.10.011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v24i0.19703.

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas. 2005;52(suppl 1):S46-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.06.014.

- Crandall C, Peterson L, Ganz PA, et al. Association of breast cancer and its therapy with menopause-related symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11:519-530. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000117061.40493.ab.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistant Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441353.20693.78.

- Faubion S, Larkin L, Stuenkel C, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendation from The North American Menopause Society and the International Society for the Study for Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001121.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Med. 2014;11:642-652. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12427.

- Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric. 2016;19:151-116. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1124259.

- Van der Lakk JAWN, de Bie LMT, de Leeuw H, et al. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerized cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446-451. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446.

- Nachtigall LE. Comparitive study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:178-180. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56474-7.

- Bygdeman M, Swahn ML. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:259-263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00955-8.

- Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, et al. Efficacy of vaginal estradiol or vaginal moisturizer vs placebo for treating postmenopausal vulvovaginal symptoms. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:681-690. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0116.

- Chen J, Geng L, Song X, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1575-1584. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12125.

- Jokar A, Davari T, Asadi N, et al. Comparison of the hyaluronic acid vaginal cream and conjugated estrogen used in treatment of vaginal atrophy of menopause women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. IJCBNM. 2016;4:69-78.

- Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, et al. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: a prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:202-212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x.

- Sutton KS, Boyer SC, Goldfinger C, et al. To lube or not to lube: experiences and perceptions of lubricant use in women with and without dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2012;9:240-250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02543.x.

- Jozkowski KN, Herbenick D, Schick V, et al. Women’s perceptions about lubricant use and vaginal wetness during sexual activity. J Sex Med. 2013;10:484-492. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12022.

- World Health Organization. Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO /UNFPA/FHI360 advisory note. 2012. https://www.who. int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/rhr12_33/en/. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira de Oliveira A, et al. Characterization of commercially available vaginal lubricants: a safety perspective. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;6:530-542. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics6030530.

- Adriaens E, Remon JP. Mucosal irritation potential of personal lubricants relates to product osmolality as detected by the slug mucosal irritation assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:512-516. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644669.

- Dezzuti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048328.

- Harvey PW, Everett DJ. Significance of the detection of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol. 2004:24:1-4. doi: 10.1002/jat.957.

- Darbre PD, Alijarrah A, Miller WR, et al. Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumous. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:5-13. doi: 10.1002/jat.958.

- Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, et al. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:297-302. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.040592.

- Hung KJ, Hudson P, Bergerat A, et al. Effect of commercial vaginal products on the growth of uropathogenic and commensal vaginal bacteria. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7625.

- Wu JP, Fielding SL, Fiscell K. The effect of the polycarbophil gel (Replens) on bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;130:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.01.007.

- Fiorelli A, Molteni B, Milani M. Successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis with a polycarbophil-carbopol acidic vaginal gel: results from a randomized double-bling, placebo controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:202-205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.10.011.

- Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, et al. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v24i0.19703.

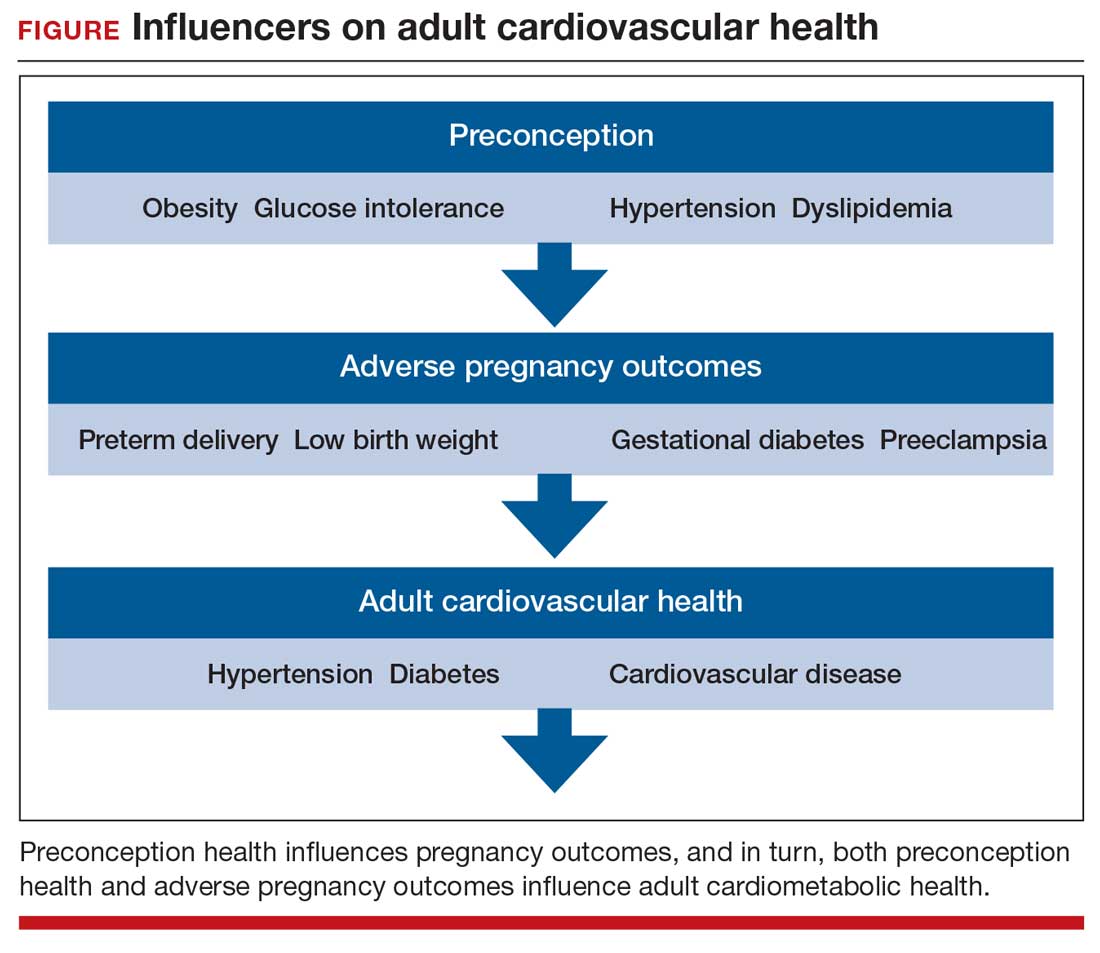

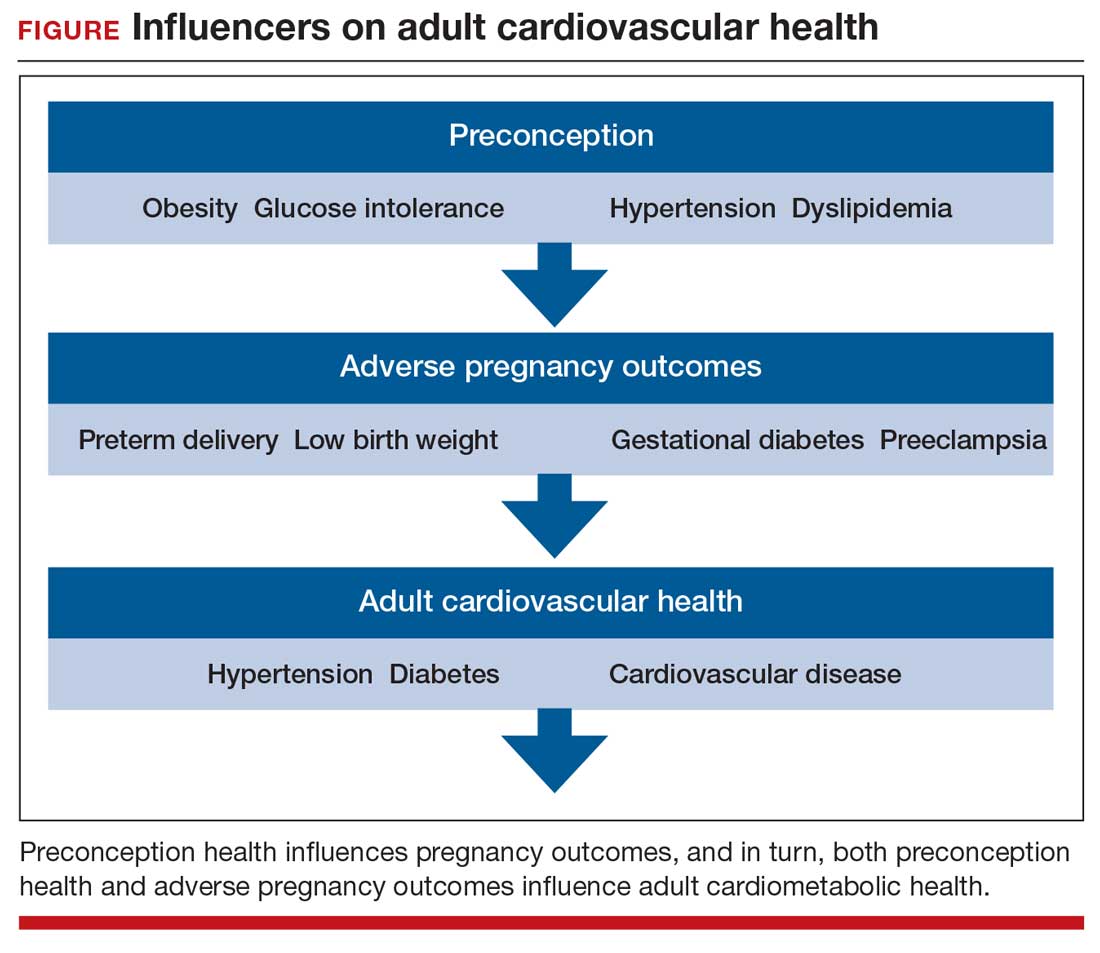

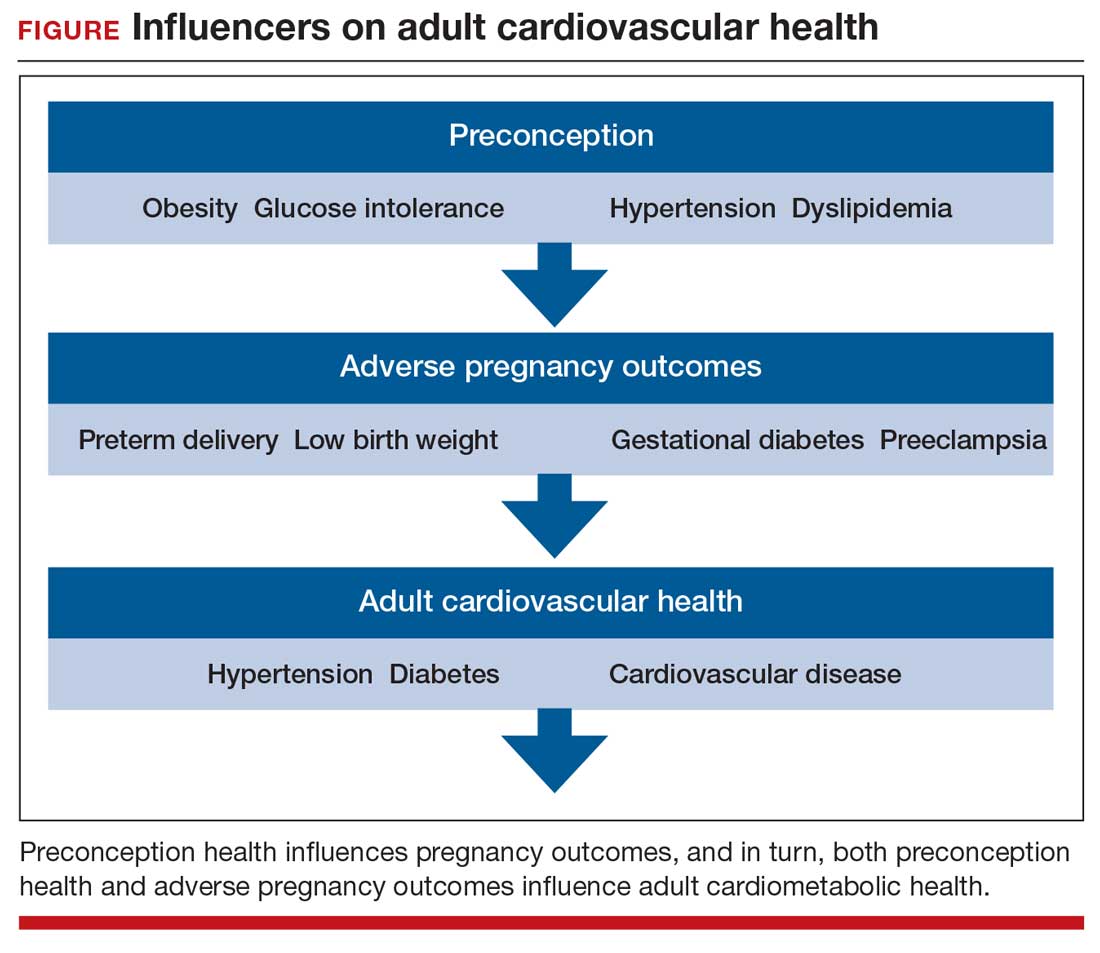

Adverse pregnancy outcomes and later cardiovascular disease

Preconception health influences pregnancy outcomes, and in turn, both preconception health and an APO influence adult cardiometabolic health (FIGURE). This editorial is focused on the link between APOs and later cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, recognizing that preconception health greatly influences the risk of an APO and lifetime cardiometabolic disease.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

Major APOs include miscarriage, preterm birth (birth <37 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (birth weight ≤2,500 g; 5.5 lb), gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, and placental abruption. In the United States, among all births, reported rates of the following APOs are:1-3

- preterm birth, 10.2%

- low birth weight, 8.3%

- GDM, 6%

- preeclampsia, 5%

- placental abruption, 1%.

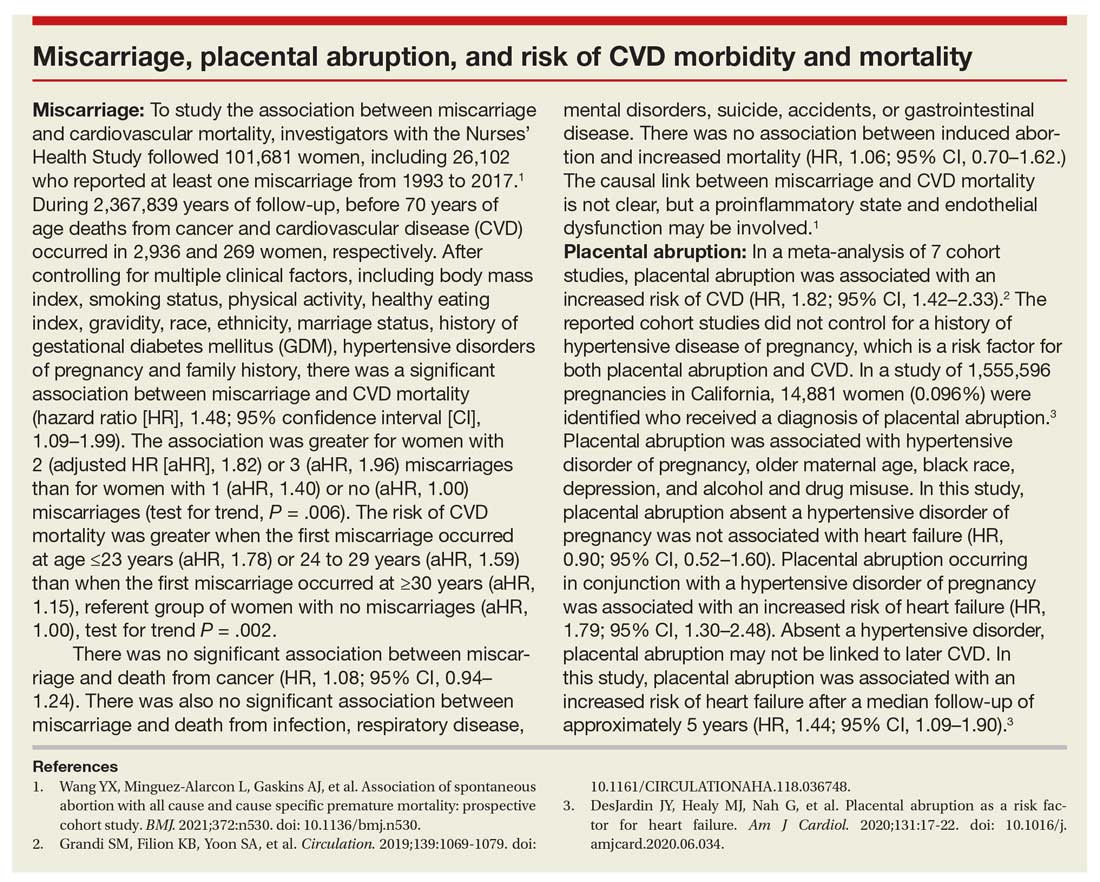

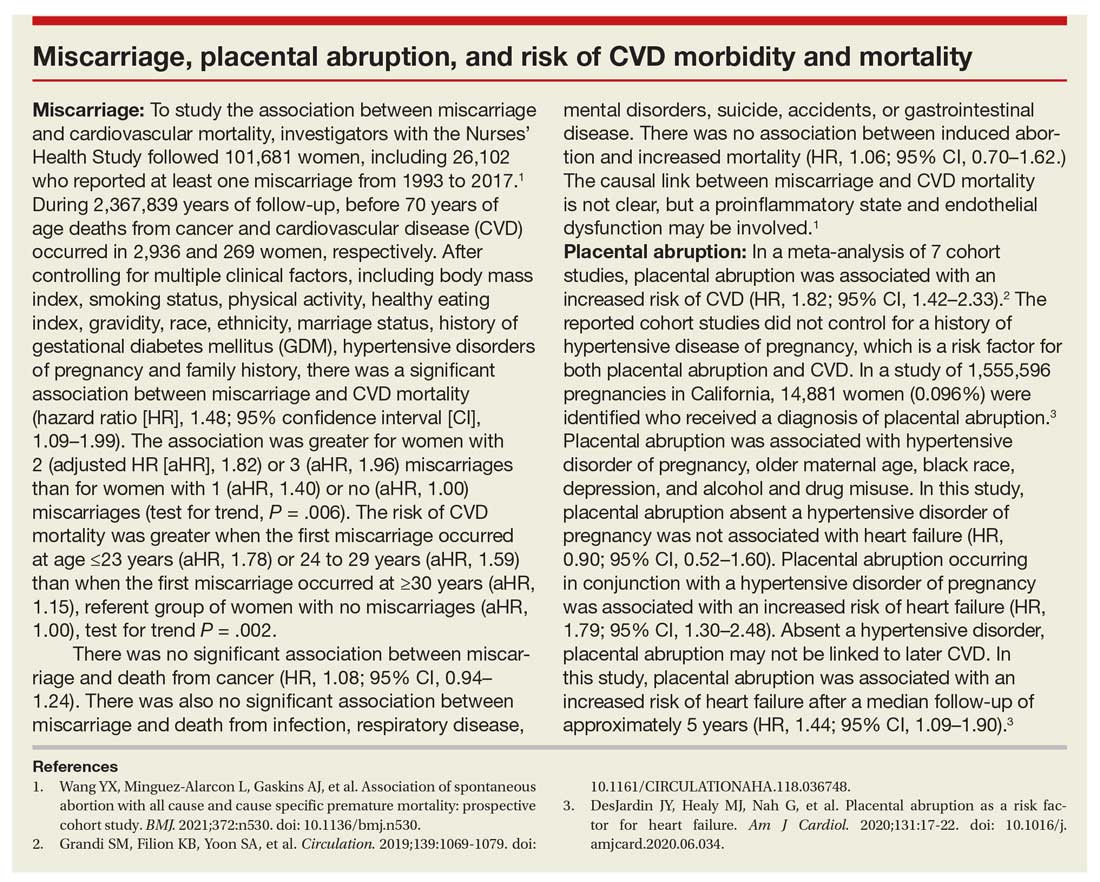

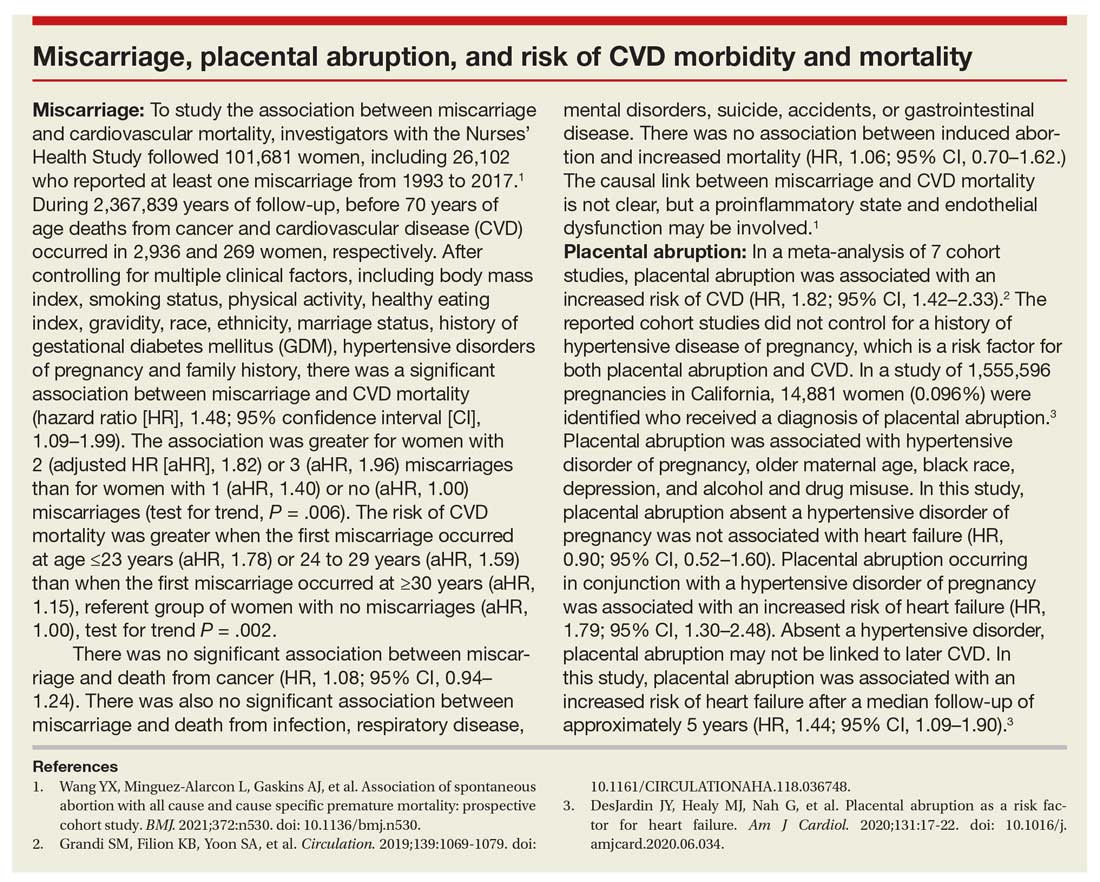

Miscarriage occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of pregnancies, influenced by both the age of the woman and the method used to diagnose pregnancy.4 Miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight, GDM, preeclampsia, and placental abruption have been reported to be associated with an increased risk of later cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

APOs and cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects the majority of people past the age of 60 years and includes 4 major subcategories:

- coronary heart disease, including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure

- CVD, stroke, and transient ischemic attack

- peripheral artery disease

- atherosclerosis of the aorta leading to aortic aneurysm.

Multiple meta-analyses report that APOs are associated with CVD in later life. A comprehensive review reported that the risk of CVD was increased following a pregnancy with one of these APOs: severe preeclampsia (odds ratio [OR], 2.74), GDM (OR, 1.68), preterm birth (OR, 1.93), low birth weight (OR, 1.29), and placental abruption (OR, 1.82).5

The link between APOs and CVD may be explained in part by the association of APOs with multiple risk factors for CVD, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dyslipidemia. A meta-analysis of 43 studies reported that, compared with controls, women with a history of preeclampsia have a 3.13 times greater risk of developing chronic hypertension.6 Among women with preeclampsia, approximately 20% will develop hypertension within 15 years.7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies reported that women with a history of GDM had a 9.51-times greater risk of developing T2DM than women without GDM.8 Among women with a history of GDM, over 16 years of follow-up, T2DM was diagnosed in 16.2%, compared with 1.9% of control women.8

CVD prevention—Breastfeeding: An antidote for APOs

Pregnancy stresses both the cardiovascular and metabolic systems. Breastfeeding is an antidote to the stresses imposed by pregnancy. Breastfeeding women have lower blood glucose9 and blood pressure.10

Breastfeeding reduces the risk of CVD. In a study of 100,864 parous Australian women, with a mean age of 60 years, ever breastfeeding was associated a lower risk of CVD hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96; P = .005) and CVD mortality (aHR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.89; P = .006).11

Continue to: CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations...

CVD prevention—American Heart Association recommendations

The American Heart Association12 recommends lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of CVD, including:

- Eat a high-quality diet that includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, beans, legumes, nuts, plant-based protein, lean animal protein, and fish.

- Limit intake of sugary drinks and foods, fatty or processed meats, full-fat dairy products, eggs, highly processed foods, and tropical oils.

- Exercise at least 150 minutes weekly at a moderate activity level, including muscle-strengthening activity.

- Reduce prolonged intervals of sitting.

- Live a tobacco- and nicotine-free life.

- Strive to maintain a normal body mass index.

- Consider using an activity tracker to monitor activity level.

- After 40 years of age calculate CVD risk using a validated calculator such as the American Cardiology Association risk calculator.13 This calculator uses age, gender, and lipid and blood pressure measurements to calculate the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD, including coronary death, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

Medications to reduce CVD risk

Historically, ObGyns have not routinely prescribed medications to treat hypertension, dyslipidemia, or to prevent diabetes. The recent increase in the valuation of return ambulatory visits and a reduction in the valuation assigned to procedural care may provide ObGyn practices the additional resources needed to manage some chronic diseases. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may help ObGyn practices to manage hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prediabetes.

Prior to initiating a medicine, counseling about healthy living, including smoking cessation, exercise, heart-healthy diet, and achieving an optimal body mass index is warranted.

For treatment of stage II hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) measurements with systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, therapeutic lifestyle interventions include: optimizing weight, following the DASH diet, restricting dietary sodium, physical activity, and reducing alcohol consumption. Medication treatment for essential hypertension is guided by the magnitude of BP reduction needed to achieve normotension. For women with hypertension needing antihypertensive medication and planning another pregnancy in the near future, labetalol or extended-release nifedipine may be first-line medications. For women who have completed their families or who have no immediate plans for pregnancy, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, or thiazide diuretic are commonly prescribed.14

For the treatment of elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in women who have not had a cardiovascular event, statin therapy is often warranted when both the LDL cholesterol is >100 mg/dL and the woman has a calculated 10-year risk of >10% for a cardiovascular event using the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology calculator. Most women who meet these criteria will be older than age 40 years and many will be under the care of an internal medicine or family medicine specialist, limiting the role of the ObGyn.15-17

For prevention of diabetes in women with a history of GDM, both weight loss and metformin (1,750 mg daily) have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the risk of developing T2DM.18 Among 350 women with a history of GDM who were followed for 10 years, metformin 850 mg twice daily reduced the risk of developing T2DM by 40% compared with placebo.19 In the same study, lifestyle changes without metformin, including loss of 7% of body weight plus 150 minutes of exercise weekly was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing T2DM.19 Metformin is one of the least expensive prescription medications and is cost-effective for the prevention of T2DM.18

Low-dose aspirin treatment for the prevention of CVD in women who have not had a cardiovascular event must balance a modest reduction in cardiovascular events with a small increased risk of bleeding events. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin for a limited group of women, those aged 50 to 59 years of age with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event >10% who are willing to take aspirin for 10 years. The USPSTF concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend low-dose aspirin prevention of CVD in women aged <50 years.20

Continue to: Beyond the fourth trimester...

Beyond the fourth trimester

The fourth trimester is the 12-week period following birth. At the comprehensive postpartum visit, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women with APOs be counseled about their increased lifetime risk of maternal cardiometabolic disease.21 In addition, ACOG recommends that at this visit the clinician who will assume primary responsibility for the woman’s ongoing medical care in her primary medical home be clarified. One option is to ensure a high-quality hand-off to an internal medicine or family medicine clinician. Another option is for a clinician in the ObGyn’s office practice, including a physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or office-based ObGyn, to assume some role in the primary care of the woman.

An APO is not only a pregnancy problem

An APO reverberates across a woman’s lifetime, increasing the risk of CVD and diabetes. In the United States the mean age at first birth is 27 years.1 The mean life expectancy of US women is 81 years.22 Following a birth complicated by an APO there are 5 decades of opportunity to improve health through lifestyle changes and medication treatment of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia, thereby reducing the risk of CVD.