User login

Tachycardia syndrome may be distinct marker for long COVID

Tachycardia is commonly reported in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS), also known as long COVID, authors report in a new article. The researchers say tachycardia syndrome should be considered a distinct phenotype.

The study by Marcus Ståhlberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues was published online August 11 in The American Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Ståhlberg told this news organization that although much attention has been paid to cases of clotting and perimyocarditis in patients after COVID, relatively little attention has been paid to tachycardia, despite case reports that show that palpitations are a common complaint.

“We have diagnosed a large number of patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS] and other forms of COVID-related tachycardia at our post-COVID outpatient clinic at Karolinska University Hospital and wanted to highlight this phenomenon,” he said.

Between 25% and 50% of patients at the clinic report tachycardia and/or palpitations that last 12 weeks or longer, the authors report.

“Systematic investigations suggest that 9% of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome patients report palpitations at six months,” the authors write.

The findings also shed light on potential tests and treatments, he said.

“Physicians should be liberal in performing a basic cardiological workup, including an ECG [electrocardiogram], echocardiography, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients complaining of palpitations and/or chest pain,” Dr. Ståhlberg said.

“If orthostatic intolerance is also reported – such as vertigo, nausea, dyspnea – suspicion of POTS should be raised and a head-up tilt test or at least an active standing test should be performed,” he said.

If POTS is confirmed, he said, patients should be offered a heart rate–lowering drug, such as low-dose propranolol or ivabradine. Compression garments, increased fluid intake, and a structured rehabilitation program also help.

“According to our clinical experience, ivabradine can also reduce symptoms in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia and post-COVID,” Dr. Ståhlberg said. “Another finding on Holter-ECG to look out for is frequent premature extrasystoles, which could indicate myocarditis and should warrant a cardiac MRI.”

Dr. Ståhlberg said the researchers think the mechanism underlying the tachycardia is autoimmune and that primary SARS-CoV-2 infections trigger an autoimmune response with formation of autoantibodies that can activate receptors regulating blood pressure and heart rate.

Long-lasting symptoms from COVID are prevalent, the authors note, especially in patients who experienced severe forms of the disease.

In the longest follow-up study to date of patients hospitalized with COVID, more than 60% experienced fatigue or muscle weakness 6 months after hospitalization.

PACS should not be considered a single syndrome; the term denotes an array of subsyndromes and phenotypes, the authors write. Typical symptoms include headache, fatigue, dyspnea, and mental fog but can involve multiple organs and systems.

Tachycardia can also be used as a marker to help gauge the severity of long COVID, the authors write.

“[T]achycardia can be considered a universal and easily obtainable quantitative marker of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and its severity rather than patient-reported symptoms, blood testing, and thoracic CT-scans,” they write.

An underrecognized complication

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS, director of women’s cardiovascular health and associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that she has seen many similar symptoms in the long-COVID patients referred to her practice.

Dr. Michos, who is also an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, said she’s been receiving a “huge number” of referrals of long-COVID patients with postural tachycardia, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and POTS.

“I think this is all in the spectrum of autonomic dysfunction that has been recognized a lot since COVID. POTS has been thought to have [a potentially] viral cause that triggers an autoimmune response. Even before COVID, many patients had POTS triggered by a viral infection. The question is whether COVID-related POTS for long COVID is different from other kinds of POTS.”

She says she treats long-COVID patients who complain of elevated heart rates with many of the cardiac workup procedures the authors list and that she treats them in a way similar to the way she treats patients with POTS.

She recommends checking resting oxygen levels and having patients walk the halls and measure their oxygen levels after walking, because their elevated heart rate may be related to ongoing lung injury from COVID.

Eric Adler, MD, a cardiologist with University of San Diego Health, told this news organization that the findings by Dr. Ståhlberg and colleagues are consistent with what he’s seeing in his clinical practice.

Dr. Adler agrees with the authors that tachycardia is an underrecognized complication of long COVID.

He said the article represents further proof that though people may survive COVID, the threat of long-term symptoms, such as heart palpitations, is real and supports the case for vaccinations.

The authors, Dr. Michos, and Dr. Adler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tachycardia is commonly reported in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS), also known as long COVID, authors report in a new article. The researchers say tachycardia syndrome should be considered a distinct phenotype.

The study by Marcus Ståhlberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues was published online August 11 in The American Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Ståhlberg told this news organization that although much attention has been paid to cases of clotting and perimyocarditis in patients after COVID, relatively little attention has been paid to tachycardia, despite case reports that show that palpitations are a common complaint.

“We have diagnosed a large number of patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS] and other forms of COVID-related tachycardia at our post-COVID outpatient clinic at Karolinska University Hospital and wanted to highlight this phenomenon,” he said.

Between 25% and 50% of patients at the clinic report tachycardia and/or palpitations that last 12 weeks or longer, the authors report.

“Systematic investigations suggest that 9% of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome patients report palpitations at six months,” the authors write.

The findings also shed light on potential tests and treatments, he said.

“Physicians should be liberal in performing a basic cardiological workup, including an ECG [electrocardiogram], echocardiography, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients complaining of palpitations and/or chest pain,” Dr. Ståhlberg said.

“If orthostatic intolerance is also reported – such as vertigo, nausea, dyspnea – suspicion of POTS should be raised and a head-up tilt test or at least an active standing test should be performed,” he said.

If POTS is confirmed, he said, patients should be offered a heart rate–lowering drug, such as low-dose propranolol or ivabradine. Compression garments, increased fluid intake, and a structured rehabilitation program also help.

“According to our clinical experience, ivabradine can also reduce symptoms in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia and post-COVID,” Dr. Ståhlberg said. “Another finding on Holter-ECG to look out for is frequent premature extrasystoles, which could indicate myocarditis and should warrant a cardiac MRI.”

Dr. Ståhlberg said the researchers think the mechanism underlying the tachycardia is autoimmune and that primary SARS-CoV-2 infections trigger an autoimmune response with formation of autoantibodies that can activate receptors regulating blood pressure and heart rate.

Long-lasting symptoms from COVID are prevalent, the authors note, especially in patients who experienced severe forms of the disease.

In the longest follow-up study to date of patients hospitalized with COVID, more than 60% experienced fatigue or muscle weakness 6 months after hospitalization.

PACS should not be considered a single syndrome; the term denotes an array of subsyndromes and phenotypes, the authors write. Typical symptoms include headache, fatigue, dyspnea, and mental fog but can involve multiple organs and systems.

Tachycardia can also be used as a marker to help gauge the severity of long COVID, the authors write.

“[T]achycardia can be considered a universal and easily obtainable quantitative marker of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and its severity rather than patient-reported symptoms, blood testing, and thoracic CT-scans,” they write.

An underrecognized complication

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS, director of women’s cardiovascular health and associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that she has seen many similar symptoms in the long-COVID patients referred to her practice.

Dr. Michos, who is also an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, said she’s been receiving a “huge number” of referrals of long-COVID patients with postural tachycardia, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and POTS.

“I think this is all in the spectrum of autonomic dysfunction that has been recognized a lot since COVID. POTS has been thought to have [a potentially] viral cause that triggers an autoimmune response. Even before COVID, many patients had POTS triggered by a viral infection. The question is whether COVID-related POTS for long COVID is different from other kinds of POTS.”

She says she treats long-COVID patients who complain of elevated heart rates with many of the cardiac workup procedures the authors list and that she treats them in a way similar to the way she treats patients with POTS.

She recommends checking resting oxygen levels and having patients walk the halls and measure their oxygen levels after walking, because their elevated heart rate may be related to ongoing lung injury from COVID.

Eric Adler, MD, a cardiologist with University of San Diego Health, told this news organization that the findings by Dr. Ståhlberg and colleagues are consistent with what he’s seeing in his clinical practice.

Dr. Adler agrees with the authors that tachycardia is an underrecognized complication of long COVID.

He said the article represents further proof that though people may survive COVID, the threat of long-term symptoms, such as heart palpitations, is real and supports the case for vaccinations.

The authors, Dr. Michos, and Dr. Adler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tachycardia is commonly reported in patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS), also known as long COVID, authors report in a new article. The researchers say tachycardia syndrome should be considered a distinct phenotype.

The study by Marcus Ståhlberg, MD, PhD, of Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and colleagues was published online August 11 in The American Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Ståhlberg told this news organization that although much attention has been paid to cases of clotting and perimyocarditis in patients after COVID, relatively little attention has been paid to tachycardia, despite case reports that show that palpitations are a common complaint.

“We have diagnosed a large number of patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome [POTS] and other forms of COVID-related tachycardia at our post-COVID outpatient clinic at Karolinska University Hospital and wanted to highlight this phenomenon,” he said.

Between 25% and 50% of patients at the clinic report tachycardia and/or palpitations that last 12 weeks or longer, the authors report.

“Systematic investigations suggest that 9% of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome patients report palpitations at six months,” the authors write.

The findings also shed light on potential tests and treatments, he said.

“Physicians should be liberal in performing a basic cardiological workup, including an ECG [electrocardiogram], echocardiography, and Holter ECG monitoring in patients complaining of palpitations and/or chest pain,” Dr. Ståhlberg said.

“If orthostatic intolerance is also reported – such as vertigo, nausea, dyspnea – suspicion of POTS should be raised and a head-up tilt test or at least an active standing test should be performed,” he said.

If POTS is confirmed, he said, patients should be offered a heart rate–lowering drug, such as low-dose propranolol or ivabradine. Compression garments, increased fluid intake, and a structured rehabilitation program also help.

“According to our clinical experience, ivabradine can also reduce symptoms in patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia and post-COVID,” Dr. Ståhlberg said. “Another finding on Holter-ECG to look out for is frequent premature extrasystoles, which could indicate myocarditis and should warrant a cardiac MRI.”

Dr. Ståhlberg said the researchers think the mechanism underlying the tachycardia is autoimmune and that primary SARS-CoV-2 infections trigger an autoimmune response with formation of autoantibodies that can activate receptors regulating blood pressure and heart rate.

Long-lasting symptoms from COVID are prevalent, the authors note, especially in patients who experienced severe forms of the disease.

In the longest follow-up study to date of patients hospitalized with COVID, more than 60% experienced fatigue or muscle weakness 6 months after hospitalization.

PACS should not be considered a single syndrome; the term denotes an array of subsyndromes and phenotypes, the authors write. Typical symptoms include headache, fatigue, dyspnea, and mental fog but can involve multiple organs and systems.

Tachycardia can also be used as a marker to help gauge the severity of long COVID, the authors write.

“[T]achycardia can be considered a universal and easily obtainable quantitative marker of Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and its severity rather than patient-reported symptoms, blood testing, and thoracic CT-scans,” they write.

An underrecognized complication

Erin D. Michos, MD, MHS, director of women’s cardiovascular health and associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that she has seen many similar symptoms in the long-COVID patients referred to her practice.

Dr. Michos, who is also an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, said she’s been receiving a “huge number” of referrals of long-COVID patients with postural tachycardia, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and POTS.

“I think this is all in the spectrum of autonomic dysfunction that has been recognized a lot since COVID. POTS has been thought to have [a potentially] viral cause that triggers an autoimmune response. Even before COVID, many patients had POTS triggered by a viral infection. The question is whether COVID-related POTS for long COVID is different from other kinds of POTS.”

She says she treats long-COVID patients who complain of elevated heart rates with many of the cardiac workup procedures the authors list and that she treats them in a way similar to the way she treats patients with POTS.

She recommends checking resting oxygen levels and having patients walk the halls and measure their oxygen levels after walking, because their elevated heart rate may be related to ongoing lung injury from COVID.

Eric Adler, MD, a cardiologist with University of San Diego Health, told this news organization that the findings by Dr. Ståhlberg and colleagues are consistent with what he’s seeing in his clinical practice.

Dr. Adler agrees with the authors that tachycardia is an underrecognized complication of long COVID.

He said the article represents further proof that though people may survive COVID, the threat of long-term symptoms, such as heart palpitations, is real and supports the case for vaccinations.

The authors, Dr. Michos, and Dr. Adler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HM administrators plan for 2021 and beyond

COVID’s impact on practice management

The COVID-19 pandemic has given hospitalists a time to shine. Perhaps few people see – and value – this more than the hospital medicine administrators who work to support them behind the scenes.

“I’m very proud to have been given this opportunity to serve alongside these wonderful hospitalists,” said Elda Dede, FHM, hospital medicine division administrator at the University of Kentucky Healthcare in Lexington, Ky.

As with everything else in U.S. health care, the pandemic has affected hospital medicine administrators planning for 2021 and subsequent years in a big way. Despite all the challenges, some organizations are maintaining equilibrium, while others are even expanding. And intertwined through it all is a bright outlook and a distinct sense of team support.

Pandemic impacts on 2021 planning

Though the Texas Health Physicians Group (THPG) in Fort Worth is part of Texas Health Resources (THR), Ajay Kharbanda, MBA, SFHM, vice president of practice operations at THPG, said that each hospital within the THR system decides who that hospital will contract with for hospitalist services. Because the process is competitive and there’s no guarantee that THPG will get the contract each time, THPG has a large focus on the value they can bring to the hospitals they serve and the patients they care for.

“Having our physicians engaged with their hospital entity leaders was extremely important this year with planning around COVID because multiple hospitals had to create new COVID units,” said Mr. Kharbanda.

With the pressure of not enough volume early in the pandemic, other hospitalist groups were forced to cut back on staffing. “Within our health system, we made the cultural decision not to cancel any shifts or cut back on staffing because we didn’t want our hospitalists to be impacted negatively by things that were out of their control,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

This commitment to their hospitalists paid off when there was a surge of patients during the last quarter of 2020. “We were struggling to ensure there were adequate physicians available to take care of the patients in the hospital, but because we did the right thing by our physicians in the beginning, people did whatever it took to make sure there was enough staffing available for that increased patient volume,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

The first priority for University of Kentucky Healthcare is patient care, said Ms. Dede. Before the pandemic, the health system already had a two-layer jeopardy system in place to deal with scheduling needs in case a staff member couldn’t come in. “For the pandemic, we created six teams with an escalation and de-escalation pattern so that we could be ready to face whatever changes came in,” Ms. Dede said. Thankfully, the community wasn’t hit very hard by COVID-19, so the six new teams ended up being unnecessary, “but we were fully prepared, and everybody was ready to go.”

Making staffing plans amidst all the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic was a big challenge in planning for 2021, said Tiffani Panek, CLHM, SFHM, hospital medicine division administrator at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in Baltimore. “We don’t know what next week is going to look like, let alone what two or three months from now is going to look like, so we’ve really had to learn to be flexible,” she said. No longer is there just a Plan A that can be adjusted as needed; now there has to be a Plan B, C, and D as well.

Because the hospital medicine division’s budget is tied to the hospital, Ms. Panek said there hasn’t been a negative impact. “The hospital supports the program and continues to support the program, regardless of COVID,” she said. The health system as a whole did have to reduce benefits and freeze raises temporarily to ensure employees could keep their jobs. However, she said they have been fortunate in that their staff has been able to – and will continue to – stay in place.

As with others, volume fluctuation was an enormous hurdle in 2021 planning, said Larissa Smith, adult hospitalist and palliative care manager at The Salem Health Medical Group, Salem Health Hospitals and Clinics, in Salem, Ore. “It’s really highlighted the continued need for us to be agile in how we structure and operationalize our staffing,” Ms. Smith said. “Adapting to volume fluctuations has been our main focus.”

To prepare for both high and low patient volumes in 2021 and be able to adjust accordingly, The Salem Health Medical Group finalized in December 2020 what they call “team efficiency plans.” These plans consist of four primary areas: surge capacity, low census planning, right providers and right patient collaboration, and right team size.

Ms. Smith is working on the “right providers and right patient collaboration” component with the trauma and acute care, vascular, and general surgery teams to figure out the best ways to utilize hospitalists and specialists. “It’s been really great collaboration,” she said.

Administrative priorities during COVID-19

The pandemic hasn’t changed Ms. Panek’s administrative priorities, which include making sure her staff has whatever they need to do their jobs and that her providers have administrative support. “The work that’s had to be done to fulfill those priorities has changed in light of COVID though,” she said.

For example, she and her staff are all still off site, which she said has been challenging, especially given the lack of preparation they had. “In order to support my staff and to make sure they aren’t getting overwhelmed by being at home, that means my job looks a little bit different, but it doesn’t change my priorities,” said Ms. Panek.

By mid-summer, Ms. Dede said her main priority has been onboarding new team members, which she said is difficult with so many meetings being held virtually. “I’m not walking around the hallways with these people and having opportunities to get feedback about how their onboarding is going, so engaging so many new team members organically into the culture, the vision, the goals of our practice, is a challenge,” she said.

Taking advantage of opportunities for hospital medicine is another administrative priority for Ms. Dede. “For us to be able to take a seat at every possible table where decisions are being made, participate in shaping the strategic vision of the entire institution and be an active player in bringing that vision to life,” she said. “I feel like this is a crucial moment for hospitalists.”

Lean work, which includes the new team efficiency plans, is an administrative priority for Ms. Smith, as it is for the entire organization. “I would say that my biggest priority is just supporting our team,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve been on a resiliency journey for a couple years.”

Their resiliency work involves periodic team training courtesy of Bryan Sexton, PhD, director of the Duke Center for Healthcare Safety and Quality. The goal of resiliency is to strengthen positive emotion, which enables a quicker recovery when difficulties occur. “I can’t imagine where we would be, this far into the pandemic, without that work,” said Ms. Smith. “I think it has really set us up to weather the storm, literally and figuratively.”

Ensuring the well-being of his provider group’s physicians is a high administrative priority for Mr. Kharbanda. Considering that the work they’ve always done is difficult, and the pandemic has been going on for such a long time, hospitalists are stretched thin. “We are bringing some additional resources to our providers that relate to taking care of themselves and helping them cope with the additional shifts,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

Going forward

The hospital medicine team at University of Kentucky Healthcare was already in the process of planning and adopting a new funds flow model, which increases the budget for HM, when the pandemic hit. “This is actually very good timing for us,” noted Ms. Dede. “We are currently working on building a new incentive model that maximizes engagement and academic productivity for our physicians, which in turn, will allow their careers to flourish and the involvement with enterprise leadership to increase.”

They had also planned to expand their teams and services before the pandemic, so in 2021, they’re hiring “an unprecedented number of hospitalists,” Ms. Dede said.

Mr. Kharbanda said that COVID has shown how much impact hospitalists can have on a hospital’s success, which has further highlighted their value. “Most of our programs are holding steady and we have some growth expected at some of our entities, so for those sites, we are hiring,” he said. Budget-wise, he expected to feel the pandemic’s impact for the first half of 2021, but for the second half, he hopes to return to normal.

Other than some low volumes in the spring, Salem Health has mostly maintained its typical capacities and funds. “Obviously, we don’t have control over external forces that impact health care, but we really try to home in on how we utilize our resources,” said Ms. Smith. “We’re a financially secure organization and I think our lean work really drives that.” The Salem Hospital is currently expanding a building tower to add another 150 beds, giving them more than 600 beds. “That will make us the largest hospital in Oregon,” Ms. Smith said.

Positive takeaways from the pandemic

Ms. Dede feels that hospital medicine has entered the health care spotlight with regard to hospitalists’ role in caring for patients during the pandemic. “Every challenge is an opportunity for growth and an opportunity to show that you know what you’re made of,” she said. “If there was ever doubt that the hospitalists are the beating heart of the hospital, this doubt is now gone. Hospitalists have, and will continue to, shoulder most of the care for COVID patients.”

The pandemic has also presented an opportunity at University of Kentucky Healthcare that helps accomplish both physician and hospital goals. “Hospital medicine is currently being asked to staff units and to participate in leadership committees, so this has been a great opportunity for growth for us,” Ms. Dede said.

The flexibility her team has shown has been a positive outcome for Ms. Panek. “You never really know what you’re going to be capable of doing until you have to do it,” she said. “I’m really proud of my group of administrative staff for how well that they’ve handled this considering it was supposed to be temporary. It’s really shown just how amazing the members of our team are and I think sometimes we take that for granted. COVID has made it so you don’t take things for granted anymore.”

Mr. Kharbanda sees how the pandemic has brought his hospitalist team together. Now, “it’s more like a family,” he said. “I think having the conversations around well-being and family safety were the real value as we learn to survive the pandemic. That was beautiful to see.”

The resiliency work her organization has done has helped Ms. Smith find plenty of positives in the face of the pandemic. “We are really resilient in health care and we can adapt quickly, but also safely,” she said.

Ms. Smith said the pandemic has also brought about changes for the better that will likely be permanent, like having time-saving virtual meetings and working from home. “We’ve put a lot of resources into physical structures and that takes away value from patients,” said Ms. Smith. “If we’re able to shift people in different roles to work from home, that just creates more future value for our community.”

Ms. Dede also sees the potential benefits that stem from people’s newfound comfort with video conferencing. “You can basically have grand rounds presenters from anywhere in the world,” she said. “You don’t have to fly them in, you don’t have to host them and have a whole program for a couple of days. They can talk to your people for an hour from the comfort of their home. I feel that we should take advantage of this too.”

Ms. Dede believes that expanding telehealth options and figuring out how hospitals can maximize that use is a priority right now. “Telehealth has been on the minds of so many hospital medicine practices, but there were still so many questions without answers about how to implement it,” she said. “During the pandemic, we were forced to find those solutions, but a lot of the barriers we are faced with have not been eliminated. I would recommend that groups keep their eyes open for new technological solutions that may empower your expansion into telehealth.”

COVID’s impact on practice management

COVID’s impact on practice management

The COVID-19 pandemic has given hospitalists a time to shine. Perhaps few people see – and value – this more than the hospital medicine administrators who work to support them behind the scenes.

“I’m very proud to have been given this opportunity to serve alongside these wonderful hospitalists,” said Elda Dede, FHM, hospital medicine division administrator at the University of Kentucky Healthcare in Lexington, Ky.

As with everything else in U.S. health care, the pandemic has affected hospital medicine administrators planning for 2021 and subsequent years in a big way. Despite all the challenges, some organizations are maintaining equilibrium, while others are even expanding. And intertwined through it all is a bright outlook and a distinct sense of team support.

Pandemic impacts on 2021 planning

Though the Texas Health Physicians Group (THPG) in Fort Worth is part of Texas Health Resources (THR), Ajay Kharbanda, MBA, SFHM, vice president of practice operations at THPG, said that each hospital within the THR system decides who that hospital will contract with for hospitalist services. Because the process is competitive and there’s no guarantee that THPG will get the contract each time, THPG has a large focus on the value they can bring to the hospitals they serve and the patients they care for.

“Having our physicians engaged with their hospital entity leaders was extremely important this year with planning around COVID because multiple hospitals had to create new COVID units,” said Mr. Kharbanda.

With the pressure of not enough volume early in the pandemic, other hospitalist groups were forced to cut back on staffing. “Within our health system, we made the cultural decision not to cancel any shifts or cut back on staffing because we didn’t want our hospitalists to be impacted negatively by things that were out of their control,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

This commitment to their hospitalists paid off when there was a surge of patients during the last quarter of 2020. “We were struggling to ensure there were adequate physicians available to take care of the patients in the hospital, but because we did the right thing by our physicians in the beginning, people did whatever it took to make sure there was enough staffing available for that increased patient volume,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

The first priority for University of Kentucky Healthcare is patient care, said Ms. Dede. Before the pandemic, the health system already had a two-layer jeopardy system in place to deal with scheduling needs in case a staff member couldn’t come in. “For the pandemic, we created six teams with an escalation and de-escalation pattern so that we could be ready to face whatever changes came in,” Ms. Dede said. Thankfully, the community wasn’t hit very hard by COVID-19, so the six new teams ended up being unnecessary, “but we were fully prepared, and everybody was ready to go.”

Making staffing plans amidst all the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic was a big challenge in planning for 2021, said Tiffani Panek, CLHM, SFHM, hospital medicine division administrator at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in Baltimore. “We don’t know what next week is going to look like, let alone what two or three months from now is going to look like, so we’ve really had to learn to be flexible,” she said. No longer is there just a Plan A that can be adjusted as needed; now there has to be a Plan B, C, and D as well.

Because the hospital medicine division’s budget is tied to the hospital, Ms. Panek said there hasn’t been a negative impact. “The hospital supports the program and continues to support the program, regardless of COVID,” she said. The health system as a whole did have to reduce benefits and freeze raises temporarily to ensure employees could keep their jobs. However, she said they have been fortunate in that their staff has been able to – and will continue to – stay in place.

As with others, volume fluctuation was an enormous hurdle in 2021 planning, said Larissa Smith, adult hospitalist and palliative care manager at The Salem Health Medical Group, Salem Health Hospitals and Clinics, in Salem, Ore. “It’s really highlighted the continued need for us to be agile in how we structure and operationalize our staffing,” Ms. Smith said. “Adapting to volume fluctuations has been our main focus.”

To prepare for both high and low patient volumes in 2021 and be able to adjust accordingly, The Salem Health Medical Group finalized in December 2020 what they call “team efficiency plans.” These plans consist of four primary areas: surge capacity, low census planning, right providers and right patient collaboration, and right team size.

Ms. Smith is working on the “right providers and right patient collaboration” component with the trauma and acute care, vascular, and general surgery teams to figure out the best ways to utilize hospitalists and specialists. “It’s been really great collaboration,” she said.

Administrative priorities during COVID-19

The pandemic hasn’t changed Ms. Panek’s administrative priorities, which include making sure her staff has whatever they need to do their jobs and that her providers have administrative support. “The work that’s had to be done to fulfill those priorities has changed in light of COVID though,” she said.

For example, she and her staff are all still off site, which she said has been challenging, especially given the lack of preparation they had. “In order to support my staff and to make sure they aren’t getting overwhelmed by being at home, that means my job looks a little bit different, but it doesn’t change my priorities,” said Ms. Panek.

By mid-summer, Ms. Dede said her main priority has been onboarding new team members, which she said is difficult with so many meetings being held virtually. “I’m not walking around the hallways with these people and having opportunities to get feedback about how their onboarding is going, so engaging so many new team members organically into the culture, the vision, the goals of our practice, is a challenge,” she said.

Taking advantage of opportunities for hospital medicine is another administrative priority for Ms. Dede. “For us to be able to take a seat at every possible table where decisions are being made, participate in shaping the strategic vision of the entire institution and be an active player in bringing that vision to life,” she said. “I feel like this is a crucial moment for hospitalists.”

Lean work, which includes the new team efficiency plans, is an administrative priority for Ms. Smith, as it is for the entire organization. “I would say that my biggest priority is just supporting our team,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve been on a resiliency journey for a couple years.”

Their resiliency work involves periodic team training courtesy of Bryan Sexton, PhD, director of the Duke Center for Healthcare Safety and Quality. The goal of resiliency is to strengthen positive emotion, which enables a quicker recovery when difficulties occur. “I can’t imagine where we would be, this far into the pandemic, without that work,” said Ms. Smith. “I think it has really set us up to weather the storm, literally and figuratively.”

Ensuring the well-being of his provider group’s physicians is a high administrative priority for Mr. Kharbanda. Considering that the work they’ve always done is difficult, and the pandemic has been going on for such a long time, hospitalists are stretched thin. “We are bringing some additional resources to our providers that relate to taking care of themselves and helping them cope with the additional shifts,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

Going forward

The hospital medicine team at University of Kentucky Healthcare was already in the process of planning and adopting a new funds flow model, which increases the budget for HM, when the pandemic hit. “This is actually very good timing for us,” noted Ms. Dede. “We are currently working on building a new incentive model that maximizes engagement and academic productivity for our physicians, which in turn, will allow their careers to flourish and the involvement with enterprise leadership to increase.”

They had also planned to expand their teams and services before the pandemic, so in 2021, they’re hiring “an unprecedented number of hospitalists,” Ms. Dede said.

Mr. Kharbanda said that COVID has shown how much impact hospitalists can have on a hospital’s success, which has further highlighted their value. “Most of our programs are holding steady and we have some growth expected at some of our entities, so for those sites, we are hiring,” he said. Budget-wise, he expected to feel the pandemic’s impact for the first half of 2021, but for the second half, he hopes to return to normal.

Other than some low volumes in the spring, Salem Health has mostly maintained its typical capacities and funds. “Obviously, we don’t have control over external forces that impact health care, but we really try to home in on how we utilize our resources,” said Ms. Smith. “We’re a financially secure organization and I think our lean work really drives that.” The Salem Hospital is currently expanding a building tower to add another 150 beds, giving them more than 600 beds. “That will make us the largest hospital in Oregon,” Ms. Smith said.

Positive takeaways from the pandemic

Ms. Dede feels that hospital medicine has entered the health care spotlight with regard to hospitalists’ role in caring for patients during the pandemic. “Every challenge is an opportunity for growth and an opportunity to show that you know what you’re made of,” she said. “If there was ever doubt that the hospitalists are the beating heart of the hospital, this doubt is now gone. Hospitalists have, and will continue to, shoulder most of the care for COVID patients.”

The pandemic has also presented an opportunity at University of Kentucky Healthcare that helps accomplish both physician and hospital goals. “Hospital medicine is currently being asked to staff units and to participate in leadership committees, so this has been a great opportunity for growth for us,” Ms. Dede said.

The flexibility her team has shown has been a positive outcome for Ms. Panek. “You never really know what you’re going to be capable of doing until you have to do it,” she said. “I’m really proud of my group of administrative staff for how well that they’ve handled this considering it was supposed to be temporary. It’s really shown just how amazing the members of our team are and I think sometimes we take that for granted. COVID has made it so you don’t take things for granted anymore.”

Mr. Kharbanda sees how the pandemic has brought his hospitalist team together. Now, “it’s more like a family,” he said. “I think having the conversations around well-being and family safety were the real value as we learn to survive the pandemic. That was beautiful to see.”

The resiliency work her organization has done has helped Ms. Smith find plenty of positives in the face of the pandemic. “We are really resilient in health care and we can adapt quickly, but also safely,” she said.

Ms. Smith said the pandemic has also brought about changes for the better that will likely be permanent, like having time-saving virtual meetings and working from home. “We’ve put a lot of resources into physical structures and that takes away value from patients,” said Ms. Smith. “If we’re able to shift people in different roles to work from home, that just creates more future value for our community.”

Ms. Dede also sees the potential benefits that stem from people’s newfound comfort with video conferencing. “You can basically have grand rounds presenters from anywhere in the world,” she said. “You don’t have to fly them in, you don’t have to host them and have a whole program for a couple of days. They can talk to your people for an hour from the comfort of their home. I feel that we should take advantage of this too.”

Ms. Dede believes that expanding telehealth options and figuring out how hospitals can maximize that use is a priority right now. “Telehealth has been on the minds of so many hospital medicine practices, but there were still so many questions without answers about how to implement it,” she said. “During the pandemic, we were forced to find those solutions, but a lot of the barriers we are faced with have not been eliminated. I would recommend that groups keep their eyes open for new technological solutions that may empower your expansion into telehealth.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has given hospitalists a time to shine. Perhaps few people see – and value – this more than the hospital medicine administrators who work to support them behind the scenes.

“I’m very proud to have been given this opportunity to serve alongside these wonderful hospitalists,” said Elda Dede, FHM, hospital medicine division administrator at the University of Kentucky Healthcare in Lexington, Ky.

As with everything else in U.S. health care, the pandemic has affected hospital medicine administrators planning for 2021 and subsequent years in a big way. Despite all the challenges, some organizations are maintaining equilibrium, while others are even expanding. And intertwined through it all is a bright outlook and a distinct sense of team support.

Pandemic impacts on 2021 planning

Though the Texas Health Physicians Group (THPG) in Fort Worth is part of Texas Health Resources (THR), Ajay Kharbanda, MBA, SFHM, vice president of practice operations at THPG, said that each hospital within the THR system decides who that hospital will contract with for hospitalist services. Because the process is competitive and there’s no guarantee that THPG will get the contract each time, THPG has a large focus on the value they can bring to the hospitals they serve and the patients they care for.

“Having our physicians engaged with their hospital entity leaders was extremely important this year with planning around COVID because multiple hospitals had to create new COVID units,” said Mr. Kharbanda.

With the pressure of not enough volume early in the pandemic, other hospitalist groups were forced to cut back on staffing. “Within our health system, we made the cultural decision not to cancel any shifts or cut back on staffing because we didn’t want our hospitalists to be impacted negatively by things that were out of their control,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

This commitment to their hospitalists paid off when there was a surge of patients during the last quarter of 2020. “We were struggling to ensure there were adequate physicians available to take care of the patients in the hospital, but because we did the right thing by our physicians in the beginning, people did whatever it took to make sure there was enough staffing available for that increased patient volume,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

The first priority for University of Kentucky Healthcare is patient care, said Ms. Dede. Before the pandemic, the health system already had a two-layer jeopardy system in place to deal with scheduling needs in case a staff member couldn’t come in. “For the pandemic, we created six teams with an escalation and de-escalation pattern so that we could be ready to face whatever changes came in,” Ms. Dede said. Thankfully, the community wasn’t hit very hard by COVID-19, so the six new teams ended up being unnecessary, “but we were fully prepared, and everybody was ready to go.”

Making staffing plans amidst all the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic was a big challenge in planning for 2021, said Tiffani Panek, CLHM, SFHM, hospital medicine division administrator at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in Baltimore. “We don’t know what next week is going to look like, let alone what two or three months from now is going to look like, so we’ve really had to learn to be flexible,” she said. No longer is there just a Plan A that can be adjusted as needed; now there has to be a Plan B, C, and D as well.

Because the hospital medicine division’s budget is tied to the hospital, Ms. Panek said there hasn’t been a negative impact. “The hospital supports the program and continues to support the program, regardless of COVID,” she said. The health system as a whole did have to reduce benefits and freeze raises temporarily to ensure employees could keep their jobs. However, she said they have been fortunate in that their staff has been able to – and will continue to – stay in place.

As with others, volume fluctuation was an enormous hurdle in 2021 planning, said Larissa Smith, adult hospitalist and palliative care manager at The Salem Health Medical Group, Salem Health Hospitals and Clinics, in Salem, Ore. “It’s really highlighted the continued need for us to be agile in how we structure and operationalize our staffing,” Ms. Smith said. “Adapting to volume fluctuations has been our main focus.”

To prepare for both high and low patient volumes in 2021 and be able to adjust accordingly, The Salem Health Medical Group finalized in December 2020 what they call “team efficiency plans.” These plans consist of four primary areas: surge capacity, low census planning, right providers and right patient collaboration, and right team size.

Ms. Smith is working on the “right providers and right patient collaboration” component with the trauma and acute care, vascular, and general surgery teams to figure out the best ways to utilize hospitalists and specialists. “It’s been really great collaboration,” she said.

Administrative priorities during COVID-19

The pandemic hasn’t changed Ms. Panek’s administrative priorities, which include making sure her staff has whatever they need to do their jobs and that her providers have administrative support. “The work that’s had to be done to fulfill those priorities has changed in light of COVID though,” she said.

For example, she and her staff are all still off site, which she said has been challenging, especially given the lack of preparation they had. “In order to support my staff and to make sure they aren’t getting overwhelmed by being at home, that means my job looks a little bit different, but it doesn’t change my priorities,” said Ms. Panek.

By mid-summer, Ms. Dede said her main priority has been onboarding new team members, which she said is difficult with so many meetings being held virtually. “I’m not walking around the hallways with these people and having opportunities to get feedback about how their onboarding is going, so engaging so many new team members organically into the culture, the vision, the goals of our practice, is a challenge,” she said.

Taking advantage of opportunities for hospital medicine is another administrative priority for Ms. Dede. “For us to be able to take a seat at every possible table where decisions are being made, participate in shaping the strategic vision of the entire institution and be an active player in bringing that vision to life,” she said. “I feel like this is a crucial moment for hospitalists.”

Lean work, which includes the new team efficiency plans, is an administrative priority for Ms. Smith, as it is for the entire organization. “I would say that my biggest priority is just supporting our team,” Ms. Smith said. “We’ve been on a resiliency journey for a couple years.”

Their resiliency work involves periodic team training courtesy of Bryan Sexton, PhD, director of the Duke Center for Healthcare Safety and Quality. The goal of resiliency is to strengthen positive emotion, which enables a quicker recovery when difficulties occur. “I can’t imagine where we would be, this far into the pandemic, without that work,” said Ms. Smith. “I think it has really set us up to weather the storm, literally and figuratively.”

Ensuring the well-being of his provider group’s physicians is a high administrative priority for Mr. Kharbanda. Considering that the work they’ve always done is difficult, and the pandemic has been going on for such a long time, hospitalists are stretched thin. “We are bringing some additional resources to our providers that relate to taking care of themselves and helping them cope with the additional shifts,” Mr. Kharbanda said.

Going forward

The hospital medicine team at University of Kentucky Healthcare was already in the process of planning and adopting a new funds flow model, which increases the budget for HM, when the pandemic hit. “This is actually very good timing for us,” noted Ms. Dede. “We are currently working on building a new incentive model that maximizes engagement and academic productivity for our physicians, which in turn, will allow their careers to flourish and the involvement with enterprise leadership to increase.”

They had also planned to expand their teams and services before the pandemic, so in 2021, they’re hiring “an unprecedented number of hospitalists,” Ms. Dede said.

Mr. Kharbanda said that COVID has shown how much impact hospitalists can have on a hospital’s success, which has further highlighted their value. “Most of our programs are holding steady and we have some growth expected at some of our entities, so for those sites, we are hiring,” he said. Budget-wise, he expected to feel the pandemic’s impact for the first half of 2021, but for the second half, he hopes to return to normal.

Other than some low volumes in the spring, Salem Health has mostly maintained its typical capacities and funds. “Obviously, we don’t have control over external forces that impact health care, but we really try to home in on how we utilize our resources,” said Ms. Smith. “We’re a financially secure organization and I think our lean work really drives that.” The Salem Hospital is currently expanding a building tower to add another 150 beds, giving them more than 600 beds. “That will make us the largest hospital in Oregon,” Ms. Smith said.

Positive takeaways from the pandemic

Ms. Dede feels that hospital medicine has entered the health care spotlight with regard to hospitalists’ role in caring for patients during the pandemic. “Every challenge is an opportunity for growth and an opportunity to show that you know what you’re made of,” she said. “If there was ever doubt that the hospitalists are the beating heart of the hospital, this doubt is now gone. Hospitalists have, and will continue to, shoulder most of the care for COVID patients.”

The pandemic has also presented an opportunity at University of Kentucky Healthcare that helps accomplish both physician and hospital goals. “Hospital medicine is currently being asked to staff units and to participate in leadership committees, so this has been a great opportunity for growth for us,” Ms. Dede said.

The flexibility her team has shown has been a positive outcome for Ms. Panek. “You never really know what you’re going to be capable of doing until you have to do it,” she said. “I’m really proud of my group of administrative staff for how well that they’ve handled this considering it was supposed to be temporary. It’s really shown just how amazing the members of our team are and I think sometimes we take that for granted. COVID has made it so you don’t take things for granted anymore.”

Mr. Kharbanda sees how the pandemic has brought his hospitalist team together. Now, “it’s more like a family,” he said. “I think having the conversations around well-being and family safety were the real value as we learn to survive the pandemic. That was beautiful to see.”

The resiliency work her organization has done has helped Ms. Smith find plenty of positives in the face of the pandemic. “We are really resilient in health care and we can adapt quickly, but also safely,” she said.

Ms. Smith said the pandemic has also brought about changes for the better that will likely be permanent, like having time-saving virtual meetings and working from home. “We’ve put a lot of resources into physical structures and that takes away value from patients,” said Ms. Smith. “If we’re able to shift people in different roles to work from home, that just creates more future value for our community.”

Ms. Dede also sees the potential benefits that stem from people’s newfound comfort with video conferencing. “You can basically have grand rounds presenters from anywhere in the world,” she said. “You don’t have to fly them in, you don’t have to host them and have a whole program for a couple of days. They can talk to your people for an hour from the comfort of their home. I feel that we should take advantage of this too.”

Ms. Dede believes that expanding telehealth options and figuring out how hospitals can maximize that use is a priority right now. “Telehealth has been on the minds of so many hospital medicine practices, but there were still so many questions without answers about how to implement it,” she said. “During the pandemic, we were forced to find those solutions, but a lot of the barriers we are faced with have not been eliminated. I would recommend that groups keep their eyes open for new technological solutions that may empower your expansion into telehealth.”

Survey: Family medicine adds wealth, but higher net worth skews male

.

In early 2020, in a survey done before the pandemic, family physicians reported average earnings of $234,000. In 2021, with months of pandemic behind them, survey data show that family physicians averaged $236,000 in earnings.

“Although many medical offices were closed for a period of time in 2020, some physicians made use of the Paycheck Protection Program; others cut staff, renegotiated leases, switched to telephysician visits, and made other cost-cutting changes that kept earnings on par,” Medscape’s Christine Lehman wrote.

Their net worth – total wealth accounting for all financial assets and debts – did even better in 2021. More family physicians are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (38% vs. 33%), more are worth over $5 million (4% vs. 3%), and fewer FPs are worth less than $1 million (60% vs. 65%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely, the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male, female family physicians

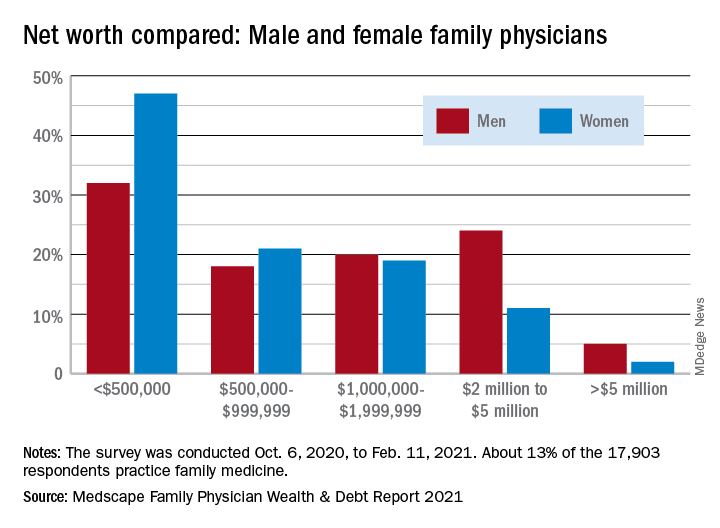

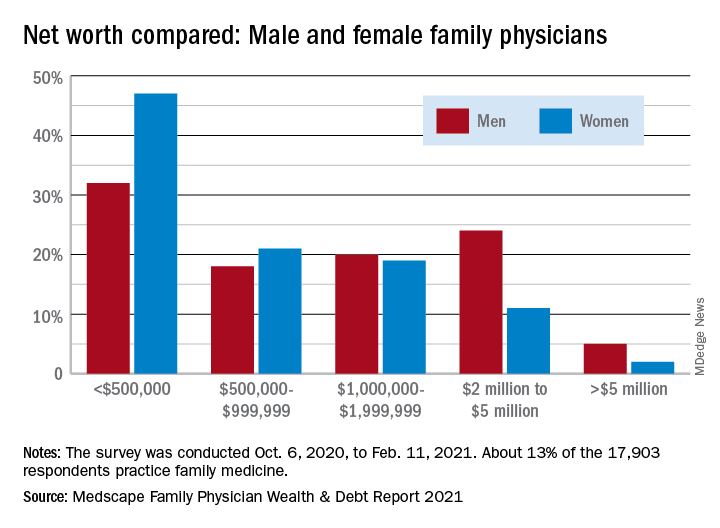

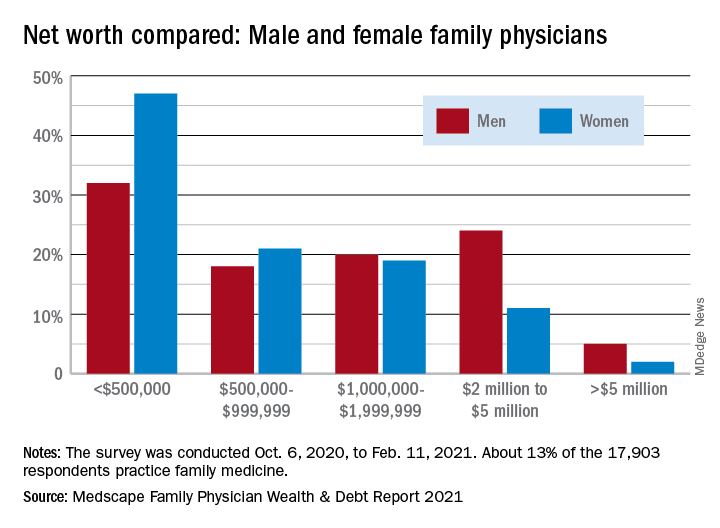

The wealth disparities that exist among family physicians get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: Five percent of male FPs are worth over $5 million versus 2% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million versus 11% of women, based on data from the 13% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice family medicine.

Zooming out from the world of family practice to the universe of all physicians shows that FPs are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, family medicine at 4%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, family physicians’ 40% share of those worth under $500,000 is at the high end of a range in which oncologists are lowest at 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Another area where FPs find themselves looking down on most specialties is medical school debt. Only emergency medicine has more physicians (33%) paying off their school loans than family medicine (31%), while infectious disease has the fewest (12%), according to the Medscape survey, which was conducted Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021.

Larger proportions of family physicians are paying off credit card debt (30%), car loans (44%), and mortgages on primary residences (67%), while 10% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 9% of FPs who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost all FPs said that they live either within (48%) or below (46%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-month emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

.

In early 2020, in a survey done before the pandemic, family physicians reported average earnings of $234,000. In 2021, with months of pandemic behind them, survey data show that family physicians averaged $236,000 in earnings.

“Although many medical offices were closed for a period of time in 2020, some physicians made use of the Paycheck Protection Program; others cut staff, renegotiated leases, switched to telephysician visits, and made other cost-cutting changes that kept earnings on par,” Medscape’s Christine Lehman wrote.

Their net worth – total wealth accounting for all financial assets and debts – did even better in 2021. More family physicians are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (38% vs. 33%), more are worth over $5 million (4% vs. 3%), and fewer FPs are worth less than $1 million (60% vs. 65%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely, the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male, female family physicians

The wealth disparities that exist among family physicians get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: Five percent of male FPs are worth over $5 million versus 2% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million versus 11% of women, based on data from the 13% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice family medicine.

Zooming out from the world of family practice to the universe of all physicians shows that FPs are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, family medicine at 4%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, family physicians’ 40% share of those worth under $500,000 is at the high end of a range in which oncologists are lowest at 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Another area where FPs find themselves looking down on most specialties is medical school debt. Only emergency medicine has more physicians (33%) paying off their school loans than family medicine (31%), while infectious disease has the fewest (12%), according to the Medscape survey, which was conducted Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021.

Larger proportions of family physicians are paying off credit card debt (30%), car loans (44%), and mortgages on primary residences (67%), while 10% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 9% of FPs who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost all FPs said that they live either within (48%) or below (46%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-month emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

.

In early 2020, in a survey done before the pandemic, family physicians reported average earnings of $234,000. In 2021, with months of pandemic behind them, survey data show that family physicians averaged $236,000 in earnings.

“Although many medical offices were closed for a period of time in 2020, some physicians made use of the Paycheck Protection Program; others cut staff, renegotiated leases, switched to telephysician visits, and made other cost-cutting changes that kept earnings on par,” Medscape’s Christine Lehman wrote.

Their net worth – total wealth accounting for all financial assets and debts – did even better in 2021. More family physicians are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (38% vs. 33%), more are worth over $5 million (4% vs. 3%), and fewer FPs are worth less than $1 million (60% vs. 65%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely, the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male, female family physicians

The wealth disparities that exist among family physicians get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: Five percent of male FPs are worth over $5 million versus 2% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million versus 11% of women, based on data from the 13% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice family medicine.

Zooming out from the world of family practice to the universe of all physicians shows that FPs are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, family medicine at 4%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, family physicians’ 40% share of those worth under $500,000 is at the high end of a range in which oncologists are lowest at 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Another area where FPs find themselves looking down on most specialties is medical school debt. Only emergency medicine has more physicians (33%) paying off their school loans than family medicine (31%), while infectious disease has the fewest (12%), according to the Medscape survey, which was conducted Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021.

Larger proportions of family physicians are paying off credit card debt (30%), car loans (44%), and mortgages on primary residences (67%), while 10% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 9% of FPs who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost all FPs said that they live either within (48%) or below (46%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-month emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

Survey: Internists gain wealth, pay off debt

a Medscape survey shows.

More internists are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (42% vs. 37%), more are worth over $5 million (6% vs. 5%), and fewer internists are worth less than $1 million (52% vs. 58%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male and female internists

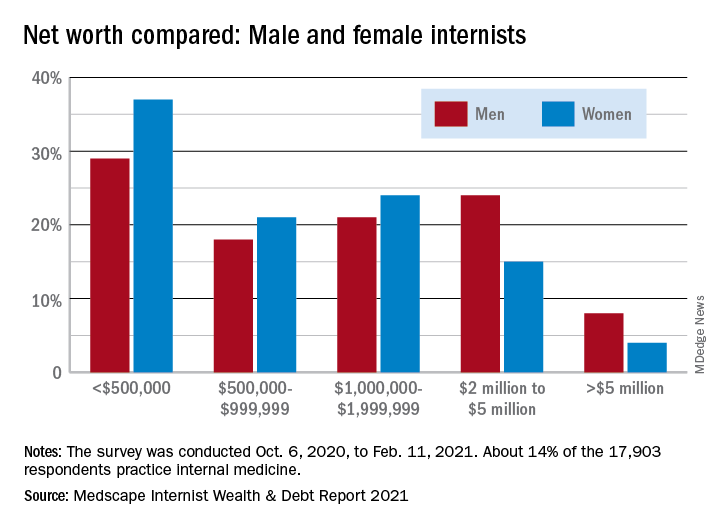

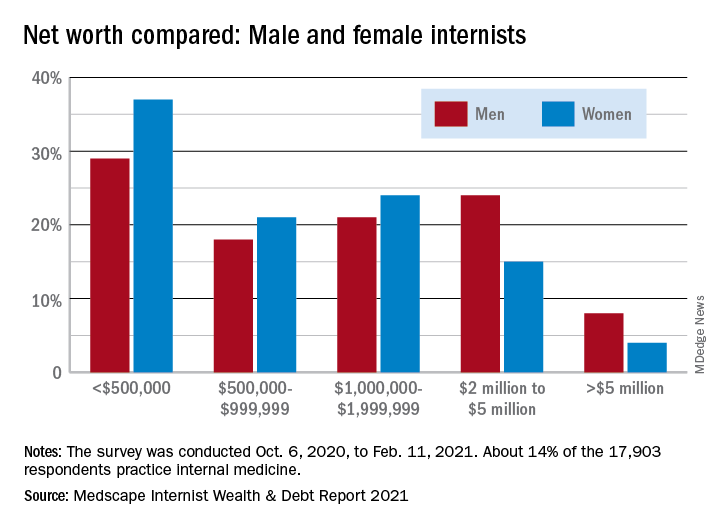

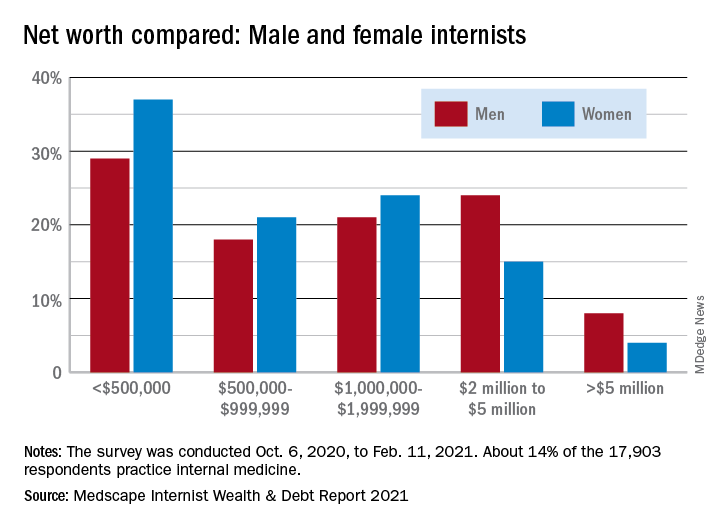

The wealth disparities that exist among internists get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: 8% of male internists are worth over $5 million versus 4% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million but only 15% of women, based on data from the 14% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice internal medicine.

Zooming out from the world of internal medicine to the universe of all physicians shows that internists are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, internal medicine at 6%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, internists’ 33% share of those worth under $500,000 is lower than family medicine’s 40% but higher than oncologists’ 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Continuing the comparison with all specialties, internists are doing somewhat better at paying off school loans. Among those responding to the survey, 20% are still paying off their medical school debt, closer to the low of 12% for infectious disease specialists than the high of 33% for the emergency physicians, according to the Medscape report.

Larger proportions of internists are paying off credit card debt (26%), car loans (35%), and mortgages on primary residences (61%), while 13% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 11% of internists who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID pandemic.

Almost all internists said that they live either within (50%) or below (44%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-months emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

a Medscape survey shows.

More internists are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (42% vs. 37%), more are worth over $5 million (6% vs. 5%), and fewer internists are worth less than $1 million (52% vs. 58%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male and female internists

The wealth disparities that exist among internists get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: 8% of male internists are worth over $5 million versus 4% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million but only 15% of women, based on data from the 14% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice internal medicine.

Zooming out from the world of internal medicine to the universe of all physicians shows that internists are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, internal medicine at 6%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, internists’ 33% share of those worth under $500,000 is lower than family medicine’s 40% but higher than oncologists’ 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Continuing the comparison with all specialties, internists are doing somewhat better at paying off school loans. Among those responding to the survey, 20% are still paying off their medical school debt, closer to the low of 12% for infectious disease specialists than the high of 33% for the emergency physicians, according to the Medscape report.

Larger proportions of internists are paying off credit card debt (26%), car loans (35%), and mortgages on primary residences (61%), while 13% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 11% of internists who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID pandemic.

Almost all internists said that they live either within (50%) or below (44%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-months emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

a Medscape survey shows.

More internists are worth $1 million to $5 million in 2021, compared with last year (42% vs. 37%), more are worth over $5 million (6% vs. 5%), and fewer internists are worth less than $1 million (52% vs. 58%), according to Medscape’s annual wealth and debt report.

“The rise in home prices is certainly a factor,” Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, a wealth management adviser for physicians, said in an interview.

“Definitely the rise in the stock market played a large role; the S&P 500 finished the year up over 18%. Finally, I’ve seen clients ... cut back on spending because they were worried about big declines in income and also because there was simply less to spend money on,” said Dr. Greenwald of St. Louis Park, Minn.

Wealth disparities between male and female internists

The wealth disparities that exist among internists get somewhat realigned, however, when viewed through the lens of physician gender. The higher-worth segments of the specialty skew rather heavily male: 8% of male internists are worth over $5 million versus 4% of females, and 24% of men are worth $2 million to $5 million but only 15% of women, based on data from the 14% of survey respondents (n = 17,903) who practice internal medicine.

Zooming out from the world of internal medicine to the universe of all physicians shows that internists are closer to allergists and immunologists than to dermatologists when it comes to share of practitioners with net worth over $5 million. That macro view puts allergy/immunology at 2%, internal medicine at 6%, and dermatology at 28%. Meanwhile, internists’ 33% share of those worth under $500,000 is lower than family medicine’s 40% but higher than oncologists’ 16%.

Medical school and other debt

Continuing the comparison with all specialties, internists are doing somewhat better at paying off school loans. Among those responding to the survey, 20% are still paying off their medical school debt, closer to the low of 12% for infectious disease specialists than the high of 33% for the emergency physicians, according to the Medscape report.

Larger proportions of internists are paying off credit card debt (26%), car loans (35%), and mortgages on primary residences (61%), while 13% said that they are not paying off debts. Nonpayment of those debts was an issue for 11% of internists who said that they missed payments on mortgages or other bills because of the COVID pandemic.

Almost all internists said that they live either within (50%) or below (44%) their means, Medscape reported.

“There are certainly folks who believe that as long as they pay off their credit card each month and contribute to their 401(k) enough to get their employer match, they’re doing okay,” Dr. Greenwald said. “I would say that living within one’s means is having a 3- to 6-months emergency fund; saving at least 20% of gross income toward retirement; adequately funding 529 college accounts; and, for younger docs, paying down high-interest-rate debt at a good clip.”

Low glycemic diet improves A1c, other risk factors in diabetes

A diet rich in vegetables and low in carbs – a so-called low glycemic index (GI) diet – is associated with clinically significant benefits beyond those provided by existing medications for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, compared with a higher glycemic diet, findings from a new meta-analysis show.

“Although the effects were small, which is not surprising in clinical trials in nutrition, they were clinically meaningful improvements for which our certainty in the effects were moderate to high,” first author Laura Chiavaroli, PhD, of the department of nutritional sciences, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, said in an interview.

The GI rates foods on the basis of how quickly they affect blood glucose levels.

Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains have a low GI. They also help to regulate blood sugar levels. Such foods are linked to a reduced risk for heart disease among people with diabetes.

But guidelines on this – such as those from the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – reflect research published more than 15 years ago, before several key trials were published.

Dr. Chiavaroli and colleagues identified 27 randomized controlled trials – the most recent of which was published in May 2021 – that involved a total of 1,617 adults with type 1 or 2 diabetes. For the patients in these trials, diabetes was moderately controlled with glucose-lowering drugs or insulin. All of the included trials examined the effects of a low GI diet or a low glycemic load (GL) diet for people with diabetes over a period 3 or more weeks. The majority of patients in the studies were overweight or had obesity, and they were largely middle-aged.

The meta-analysis, which included new data, was published Aug. 5 in The BMJ. The study “expands the number of relevant intermediate cardiometabolic outcomes, and assesses the certainty of the evidence using GRADE [grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation],” Dr. Chiavaroli and colleagues noted.

“The available evidence provides a good indication of the likely benefit in this population and supports existing recommendations for the use of low GI dietary patterns in the management of diabetes,” they emphasized.

Improvements in A1c, fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides

Overall, compared with people who consumed diets with higher GI/GL ratings, for those who consumed lower glycemic diets, glycemic control was significantly improved, as reflected in A1c level, which was the primary outcome of the study (mean difference, –0.31%; P < .001).

This “would meet the threshold of ≥ 0.3% reduction in HbA1c proposed by the European Medicines Agency as clinically relevant for risk reduction of diabetic complications,” the authors noted.

Those who consumed low glycemic diets also showed improvements in secondary outcomes, including fasting glucose level, which was reduced by 0.36 mmol/L (–6.5 mg/dL), a 6% reduction in low-density cholesterol (LDL-C) (–0.17 mmol/L), and a fall in triglyceride levels (–0.09 mmol/L).

They also lost marginally more body weight, at –0.66 kg (–1.5 pounds). Body mass index was lower by –0.38, and inflammation was reduced (C-reactive protein, –.41 mg/L; all P < .05).

No significant differences were observed between the groups in blood insulin level, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, waist circumference, or blood pressure.

Three of the studies showed that participants developed a preference for the low GI diet. “In recent years, there has been a growing interest in whole-food plant-based diets, and there are more options, for example, for pulse-based products,” Dr. Chiavaroli said.

This meta-analysis should support the recommendation of the low-glycemic diet, particularly among people with diabetes, she reiterated.

Will larger randomized trial show effect on outcomes?

The authors noted, however, that to determine whether these small improvements in intermediate cardiometabolic risk factors observed with low GI diets translate to reductions in cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and retinopathy among people with diabetes, larger randomized trials are needed.

One such trial, the Low Glycemic Index Diet for Type 2 Diabetics, includes 169 high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes and subclinical atherosclerosis. The investigators are evaluating the effect of a low GI diet on the progression of atherosclerosis, as assessed by vascular MRI over 3 years.

“We await the results,” they said.