User login

The Implications of Power Mobility on Body Weight in a Veteran Population

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical practice recommendations endorse a power mobility device (PMD) for individuals with adequate judgment, cognitive ability, and vision who are unable to propel a manual wheelchair or walk community distances despite standard medical and rehabilitative interventions.1 VHA supports the use of a PMD in order to access medical care and accomplish activities of daily living, both at home and in the community for veterans with mobility limitations secondary to cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, pulmonary disease, or musculoskeletal disorders. The goal of a PMD use is increased participation in community and social life, improved health maintenance via enhanced access to medical facilities, and an overall enhanced quality of life. However, there is a common concern among health care providers that prescribing a PMD may decrease physical activity, in turn, leading to obesity and increasing morbidity. 2

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in the United States. In the past decade 35.0% of men and 36.8% of women were classified as obese (body mass index [BMI], ≥ 30).3 Recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the overall prevalence of obesity in Americans is closer to 42.4%.4 The veteran population is not immune to this; a 2014 study of nearly 5 million veterans reported that the prevalence of obesity in this population was 41%.5,6 In addition to obesity being implicated in exacerbating many medical problems, such as osteoarthritis, insulin resistance, and heart disease, obesity also is associated with a significant decrease in lifespan.7 Almost half of adults who report ambulatory dysfunction are obese.8 Given the increased morbidity and mortality as a result of obesity, interventions that may promote weight gain need to be appropriately identified and minimized.

In a retrospective study of 89 veterans, Yang and colleagues demonstrated no significant weight change 1 year after initial PMD prescription.2 Another study of 102 patients noted no significant weight changes 1 year after PMD prescription.9 This study analyzes the effect of PMD prescriptions over a 2-year period on BMI and body weight in a larger population of veterans both as a whole and in BMI/age subgroups.

Methods

The institutional review board at Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia, reviewed and approved this study. A waiver of participant consent was approved due to the nature of the research (medical records of patients, some of whom were deceased) and the type of data collected (retrospective data). In addition, each individual was assigned a sequential code to de-identify any personal information. Prosthetics department medical records of consecutive veterans who received PMDs for the first time between January 1, 2011 and June 30, 2012, were reviewed.

Data extracted from the electronic health record (EHR) included demographics, indication for power mobility, weight at time of PMD prescription, weight at 2-years postprescription, and height. Weight readings were considered valid if weight was taken within 3 months of initial prescription and then again within 3 months at the 2-year interval. Individuals without weights recorded in these time frames were excluded. In addition, we excluded medical conditions that might significantly affect body weight, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), amputation during the study period, or history of weight loss surgery. Cancer diagnoses were excluded as they were not an indication for power mobility in the VHA. ALS, though variable in its disease course, was specifically excluded given the likelihood of these patients dying of the natural progression of the disease before the 2-year follow-up period: Median survival times in patients diagnosed with ALS aged > 60 years was < 15 months. 10-12

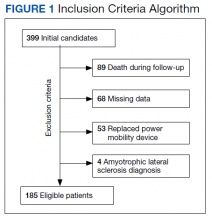

The EHRs of 399 individuals who received a PMD during the period were reviewed, and 185 veterans met criteria for data analysis. Subject exclusions in the weight and BMI analysis included death during the follow-up period (89), missing data (68), prior PMD users who came in for replacements (53), and ALS (4) (Figure 1). Patients were not excluded based on the presence or absence of intentional weight loss efforts as this information was not readily available through chart review.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change in BMI and body weight from time 1 (date of PMD prescription) to time 2 (2 years later). Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21. BMI was calculated using the weight (lb) x 703/ (height [inches]).2 Dichotomization of BMI was performed using the conventional cut scores: < 30.0, not obese; and ≥ 30.0, obese. Paired t tests and SPSS general linear model (repeated measures) were used to examine change of BMI from time 1 to time 2. The exact McNemar test was used to examine change in obesity classification across time 1 and time 2. Correlating with Yang’s retrospective observational study, data were analyzed separately for aged < 65 years and aged≥ 65 years.2

Results

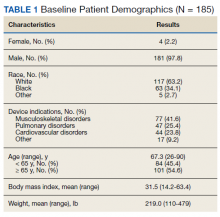

Of the 185 veterans, 181 were male (98%); mean age was 67.3 years (range, 26-90); and 55% were aged ≥ 65 years. Musculoskeletal disorders (41.6%) were the most common primary indication for a PMD, followed by pulmonary disorders (25.4%) and cardiovascular disorders (23.8%) (Table 1).

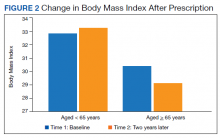

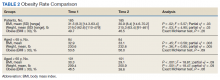

There was a significant decrease in BMI in the first 2 years after receiving a PMD prescription for the first time (estimated marginal means: 31.5 to 30.9 , P = .02). However, age moderated the relationship between BMI and time F[1, 183] = 12.14, P = .001, partial η2 = .06 (Table 2). The 101 subjects aged > 65 years experienced a significant decrease in BMI (estimated marginal means: 30.3 to 29.1, P < .001), whereas the 84 patients aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in BMI (estimated marginal means: 32.9 to 33.1, P = .45). BMI was significantly higher for subjects aged < 65 years at Time 1 (F[1, 183] = 4.32, P = .04, partial η2 = .02) and at Time 2 (F[1, 183] = 11.04, P = .001, partial η2 = .06).

Similarly, there was a significant decrease in weight in the first year after receiving a PMD prescription with a change in mean weight from 219.0 to 215.3 lb (P = .3). Again, age moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 12.81; P < .001; partial η2 = .07). Individuals aged ≥ 65 years experienced a significant decrease in weight (estimated marginal means = 209.4 to 200.9; P < .001), whereas those aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in weight (230.6 to 232.6; P = .36). Weight was significantly higher for individuals aged < 65 years at time 1 (F = 5.34; P = .02; partial η2 = .03) and at time 2 (F = 12.18; P = .001; partial η2 = .06).

The percentage of those who were obese (BMI ≥ 30) at time 1 (49.7%) did not significantly change at time 2 (46.5%) (exact McNemar test, P = .26). Similarly, there was no significant change in obesity from time 1 to time 2 for those aged < 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .69) or for those aged ≥ 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .06). Obesity at time 2 was significantly more common in those aged < 65 years (56.0%) than those aged ≥ 65 years (38.6%), χ2 [1] = 5.54; P = .02. Obesity at time 1 did not differ between those aged < 65 years (53.6%) and aged ≥ 65 years (46.5%), η2 [1] = 0.9; P = .34. Obesity moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 5.10; P = .03; partial η2= .03) in that obese individuals experienced a significant decrease in weight with estimated marginal means (SE) = 264.5 (4.51) to 257.4 (4.97); F = 11.32; P < .001; partial η2 = .06), whereas nonobese individuals had no weight change with estimated marginal means (SE) = 174.0 (4.48) to 173.61 (4.94); F = .03; P < .86; partial η2< .01).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant decrease in both weight and BMI at 2 years after the initiation of a PMD in patients aged < 65 years. No significant change was found for obesity rates. However, veterans who met criteria for obesity at the time of PMD prescription saw a significant decrease in their weight at 2 years compared with those who were nonobese.

VHA supports power mobility when there is a clear functional need that cannot be met by rehabilitation, surgical, or medical interventions to enhance veterans’ abilities to access medical care, accomplish necessary tasks of daily living, and to have greater access to their communities. Though limited by strength of association, studies involving PMD users generally found improvement in reported functional outcomes and overall satisfaction with PMD use based on a systematic review.13 Nonetheless, there is an implicit concern among providers that a PMD prescription, by limiting physical activity, may exacerbate obesity trends in potentially high-risk individuals.

However, a controversy exists about whether increasing physical activity alone leads to weight loss. A 2007 study followed 102 sedentary men and 100 women over 1 year randomized to moderately intensive exercise for 60 minutes, 6 days a week vs no intervention.14 The men lost an average of 4 pounds, and women lost an average of 3 pounds after 1 year. The Women’s Health Study divided 39,876 women into high, medium, and low levels of exercise groups. After 10 years, the intense exercise group did not have any significant weight loss.15

Our study was consistent with existing literature in that a PMD prescription did not correlate with weight gain.2,9 In our veteran population aged ≥ 65 years, we observed an opposite trend of weight loss after PMD prescription. Of note, studies have shown that peak body weight occurs in the sixth decade, remains stable until about aged 70 years, and then slowly decreases thereafter, at a rate of 0.1 to 0.2 kg per year.16 This likely explains some of the weight loss trend we observed in our study of veterans aged ≥ 65 years. Possible additional explanations include improved access to health care and to more nutritional foods that promote general health and well-being.

Limitations

The data were gathered from a predominantly male veteran population, potentially limiting generalizability. The health of any individual is determined by the interaction of factors of which body weight is just a single, isolated component. As such, the effect of powered mobility on body weight is not a direct reflection on the effect on overall health. Additionally, there are many factors that may affect an individual’s body weight, such as optimal management of medical comorbidities, which could not be controlled for in this study. Also, while these values can be compared with other veteran populations, this study had no true control group.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study with aforementioned limitations, PMD use does not seem to be associated with significant weight changes. Further studies using control groups and assessing comorbidities are needed.

1. Perlin J. Clinical practice recommendations for motorized wheeled mobility devices: scooters, pushrim-activated power-assist wheelchairs, power wheelchairs, and power wheelchairs with enhanced function. Published 2004. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/Docs/Motorized_Wheeled_Mobility_Devices.pdf

2. Yang W, Wilson L, Oda I, Yan J. The effect of providing power mobility on weight change. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):746-753. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31813e0645

3. Yang, L, Colditz GA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 2007-2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(8):1412–1413. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2405

4. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020.

5. Almond N, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L, Porterfield D. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among U.S. military veterans. Mil Med. 2008;173(6):544-549. doi:10.7205/milmed.173.6.544

6. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

7. Bray G. Medical consequences of obesity. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2583-2589. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0535

8. Fox MH, Witten MH, Lullo C. Reducing obesity among people with disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2014;25(3):175-185. doi:10.1177/1044207313494236

9. Zagol BW, Krasuski RA. Effect of motorized scooters on quality of life and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(5):672-676. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.049

10. Traxinger K, Kelly C, Johnson BA, Lyles RH, Glass JD. Prognosis and epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: analysis of a clinic population, 1997-2011. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3(4):313-320. doi:10.1212/cpj.0b013e3182a1b8ab

11. Wolf J, Safer A, Wöhrle J, et al. Factors predicting one-year mortality in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients—data from a population-based registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):197. doi:10.1186/s12883-014-0197-9

12. Körner S, Hendricks M, Kollewe K, et al. Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement intake in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): impact on quality of life and therapeutic options. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-84

13. Auger CJ, Demers L, Gélinas I, et al. Powered mobility for middle-aged and older adults: systematic review of outcomes and appraisal of published evidence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(8):666-680. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31816de163

14. McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin M, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1496-512. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.178

15. Lee IM, Djoussé L, Sesso H, Wang L, Buring JE . Physical activity and weight gain prevention, women’s health study. JAMA. 2010;303(12):1173-1179. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.312

16. Wallace J, Schwartz R. Epidemiology of weight loss in humans with special reference to wasting in the elderly. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00246-2

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical practice recommendations endorse a power mobility device (PMD) for individuals with adequate judgment, cognitive ability, and vision who are unable to propel a manual wheelchair or walk community distances despite standard medical and rehabilitative interventions.1 VHA supports the use of a PMD in order to access medical care and accomplish activities of daily living, both at home and in the community for veterans with mobility limitations secondary to cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, pulmonary disease, or musculoskeletal disorders. The goal of a PMD use is increased participation in community and social life, improved health maintenance via enhanced access to medical facilities, and an overall enhanced quality of life. However, there is a common concern among health care providers that prescribing a PMD may decrease physical activity, in turn, leading to obesity and increasing morbidity. 2

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in the United States. In the past decade 35.0% of men and 36.8% of women were classified as obese (body mass index [BMI], ≥ 30).3 Recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the overall prevalence of obesity in Americans is closer to 42.4%.4 The veteran population is not immune to this; a 2014 study of nearly 5 million veterans reported that the prevalence of obesity in this population was 41%.5,6 In addition to obesity being implicated in exacerbating many medical problems, such as osteoarthritis, insulin resistance, and heart disease, obesity also is associated with a significant decrease in lifespan.7 Almost half of adults who report ambulatory dysfunction are obese.8 Given the increased morbidity and mortality as a result of obesity, interventions that may promote weight gain need to be appropriately identified and minimized.

In a retrospective study of 89 veterans, Yang and colleagues demonstrated no significant weight change 1 year after initial PMD prescription.2 Another study of 102 patients noted no significant weight changes 1 year after PMD prescription.9 This study analyzes the effect of PMD prescriptions over a 2-year period on BMI and body weight in a larger population of veterans both as a whole and in BMI/age subgroups.

Methods

The institutional review board at Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia, reviewed and approved this study. A waiver of participant consent was approved due to the nature of the research (medical records of patients, some of whom were deceased) and the type of data collected (retrospective data). In addition, each individual was assigned a sequential code to de-identify any personal information. Prosthetics department medical records of consecutive veterans who received PMDs for the first time between January 1, 2011 and June 30, 2012, were reviewed.

Data extracted from the electronic health record (EHR) included demographics, indication for power mobility, weight at time of PMD prescription, weight at 2-years postprescription, and height. Weight readings were considered valid if weight was taken within 3 months of initial prescription and then again within 3 months at the 2-year interval. Individuals without weights recorded in these time frames were excluded. In addition, we excluded medical conditions that might significantly affect body weight, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), amputation during the study period, or history of weight loss surgery. Cancer diagnoses were excluded as they were not an indication for power mobility in the VHA. ALS, though variable in its disease course, was specifically excluded given the likelihood of these patients dying of the natural progression of the disease before the 2-year follow-up period: Median survival times in patients diagnosed with ALS aged > 60 years was < 15 months. 10-12

The EHRs of 399 individuals who received a PMD during the period were reviewed, and 185 veterans met criteria for data analysis. Subject exclusions in the weight and BMI analysis included death during the follow-up period (89), missing data (68), prior PMD users who came in for replacements (53), and ALS (4) (Figure 1). Patients were not excluded based on the presence or absence of intentional weight loss efforts as this information was not readily available through chart review.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change in BMI and body weight from time 1 (date of PMD prescription) to time 2 (2 years later). Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21. BMI was calculated using the weight (lb) x 703/ (height [inches]).2 Dichotomization of BMI was performed using the conventional cut scores: < 30.0, not obese; and ≥ 30.0, obese. Paired t tests and SPSS general linear model (repeated measures) were used to examine change of BMI from time 1 to time 2. The exact McNemar test was used to examine change in obesity classification across time 1 and time 2. Correlating with Yang’s retrospective observational study, data were analyzed separately for aged < 65 years and aged≥ 65 years.2

Results

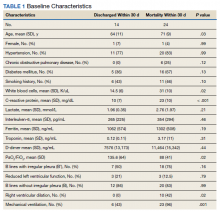

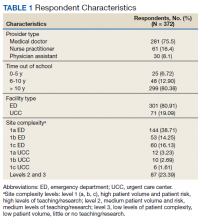

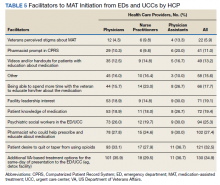

Of the 185 veterans, 181 were male (98%); mean age was 67.3 years (range, 26-90); and 55% were aged ≥ 65 years. Musculoskeletal disorders (41.6%) were the most common primary indication for a PMD, followed by pulmonary disorders (25.4%) and cardiovascular disorders (23.8%) (Table 1).

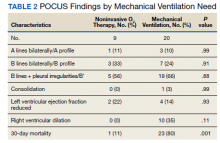

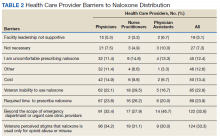

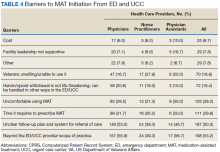

There was a significant decrease in BMI in the first 2 years after receiving a PMD prescription for the first time (estimated marginal means: 31.5 to 30.9 , P = .02). However, age moderated the relationship between BMI and time F[1, 183] = 12.14, P = .001, partial η2 = .06 (Table 2). The 101 subjects aged > 65 years experienced a significant decrease in BMI (estimated marginal means: 30.3 to 29.1, P < .001), whereas the 84 patients aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in BMI (estimated marginal means: 32.9 to 33.1, P = .45). BMI was significantly higher for subjects aged < 65 years at Time 1 (F[1, 183] = 4.32, P = .04, partial η2 = .02) and at Time 2 (F[1, 183] = 11.04, P = .001, partial η2 = .06).

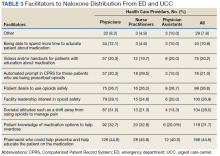

Similarly, there was a significant decrease in weight in the first year after receiving a PMD prescription with a change in mean weight from 219.0 to 215.3 lb (P = .3). Again, age moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 12.81; P < .001; partial η2 = .07). Individuals aged ≥ 65 years experienced a significant decrease in weight (estimated marginal means = 209.4 to 200.9; P < .001), whereas those aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in weight (230.6 to 232.6; P = .36). Weight was significantly higher for individuals aged < 65 years at time 1 (F = 5.34; P = .02; partial η2 = .03) and at time 2 (F = 12.18; P = .001; partial η2 = .06).

The percentage of those who were obese (BMI ≥ 30) at time 1 (49.7%) did not significantly change at time 2 (46.5%) (exact McNemar test, P = .26). Similarly, there was no significant change in obesity from time 1 to time 2 for those aged < 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .69) or for those aged ≥ 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .06). Obesity at time 2 was significantly more common in those aged < 65 years (56.0%) than those aged ≥ 65 years (38.6%), χ2 [1] = 5.54; P = .02. Obesity at time 1 did not differ between those aged < 65 years (53.6%) and aged ≥ 65 years (46.5%), η2 [1] = 0.9; P = .34. Obesity moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 5.10; P = .03; partial η2= .03) in that obese individuals experienced a significant decrease in weight with estimated marginal means (SE) = 264.5 (4.51) to 257.4 (4.97); F = 11.32; P < .001; partial η2 = .06), whereas nonobese individuals had no weight change with estimated marginal means (SE) = 174.0 (4.48) to 173.61 (4.94); F = .03; P < .86; partial η2< .01).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant decrease in both weight and BMI at 2 years after the initiation of a PMD in patients aged < 65 years. No significant change was found for obesity rates. However, veterans who met criteria for obesity at the time of PMD prescription saw a significant decrease in their weight at 2 years compared with those who were nonobese.

VHA supports power mobility when there is a clear functional need that cannot be met by rehabilitation, surgical, or medical interventions to enhance veterans’ abilities to access medical care, accomplish necessary tasks of daily living, and to have greater access to their communities. Though limited by strength of association, studies involving PMD users generally found improvement in reported functional outcomes and overall satisfaction with PMD use based on a systematic review.13 Nonetheless, there is an implicit concern among providers that a PMD prescription, by limiting physical activity, may exacerbate obesity trends in potentially high-risk individuals.

However, a controversy exists about whether increasing physical activity alone leads to weight loss. A 2007 study followed 102 sedentary men and 100 women over 1 year randomized to moderately intensive exercise for 60 minutes, 6 days a week vs no intervention.14 The men lost an average of 4 pounds, and women lost an average of 3 pounds after 1 year. The Women’s Health Study divided 39,876 women into high, medium, and low levels of exercise groups. After 10 years, the intense exercise group did not have any significant weight loss.15

Our study was consistent with existing literature in that a PMD prescription did not correlate with weight gain.2,9 In our veteran population aged ≥ 65 years, we observed an opposite trend of weight loss after PMD prescription. Of note, studies have shown that peak body weight occurs in the sixth decade, remains stable until about aged 70 years, and then slowly decreases thereafter, at a rate of 0.1 to 0.2 kg per year.16 This likely explains some of the weight loss trend we observed in our study of veterans aged ≥ 65 years. Possible additional explanations include improved access to health care and to more nutritional foods that promote general health and well-being.

Limitations

The data were gathered from a predominantly male veteran population, potentially limiting generalizability. The health of any individual is determined by the interaction of factors of which body weight is just a single, isolated component. As such, the effect of powered mobility on body weight is not a direct reflection on the effect on overall health. Additionally, there are many factors that may affect an individual’s body weight, such as optimal management of medical comorbidities, which could not be controlled for in this study. Also, while these values can be compared with other veteran populations, this study had no true control group.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study with aforementioned limitations, PMD use does not seem to be associated with significant weight changes. Further studies using control groups and assessing comorbidities are needed.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) clinical practice recommendations endorse a power mobility device (PMD) for individuals with adequate judgment, cognitive ability, and vision who are unable to propel a manual wheelchair or walk community distances despite standard medical and rehabilitative interventions.1 VHA supports the use of a PMD in order to access medical care and accomplish activities of daily living, both at home and in the community for veterans with mobility limitations secondary to cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, pulmonary disease, or musculoskeletal disorders. The goal of a PMD use is increased participation in community and social life, improved health maintenance via enhanced access to medical facilities, and an overall enhanced quality of life. However, there is a common concern among health care providers that prescribing a PMD may decrease physical activity, in turn, leading to obesity and increasing morbidity. 2

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in the United States. In the past decade 35.0% of men and 36.8% of women were classified as obese (body mass index [BMI], ≥ 30).3 Recent figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that the overall prevalence of obesity in Americans is closer to 42.4%.4 The veteran population is not immune to this; a 2014 study of nearly 5 million veterans reported that the prevalence of obesity in this population was 41%.5,6 In addition to obesity being implicated in exacerbating many medical problems, such as osteoarthritis, insulin resistance, and heart disease, obesity also is associated with a significant decrease in lifespan.7 Almost half of adults who report ambulatory dysfunction are obese.8 Given the increased morbidity and mortality as a result of obesity, interventions that may promote weight gain need to be appropriately identified and minimized.

In a retrospective study of 89 veterans, Yang and colleagues demonstrated no significant weight change 1 year after initial PMD prescription.2 Another study of 102 patients noted no significant weight changes 1 year after PMD prescription.9 This study analyzes the effect of PMD prescriptions over a 2-year period on BMI and body weight in a larger population of veterans both as a whole and in BMI/age subgroups.

Methods

The institutional review board at Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia, reviewed and approved this study. A waiver of participant consent was approved due to the nature of the research (medical records of patients, some of whom were deceased) and the type of data collected (retrospective data). In addition, each individual was assigned a sequential code to de-identify any personal information. Prosthetics department medical records of consecutive veterans who received PMDs for the first time between January 1, 2011 and June 30, 2012, were reviewed.

Data extracted from the electronic health record (EHR) included demographics, indication for power mobility, weight at time of PMD prescription, weight at 2-years postprescription, and height. Weight readings were considered valid if weight was taken within 3 months of initial prescription and then again within 3 months at the 2-year interval. Individuals without weights recorded in these time frames were excluded. In addition, we excluded medical conditions that might significantly affect body weight, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), amputation during the study period, or history of weight loss surgery. Cancer diagnoses were excluded as they were not an indication for power mobility in the VHA. ALS, though variable in its disease course, was specifically excluded given the likelihood of these patients dying of the natural progression of the disease before the 2-year follow-up period: Median survival times in patients diagnosed with ALS aged > 60 years was < 15 months. 10-12

The EHRs of 399 individuals who received a PMD during the period were reviewed, and 185 veterans met criteria for data analysis. Subject exclusions in the weight and BMI analysis included death during the follow-up period (89), missing data (68), prior PMD users who came in for replacements (53), and ALS (4) (Figure 1). Patients were not excluded based on the presence or absence of intentional weight loss efforts as this information was not readily available through chart review.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the change in BMI and body weight from time 1 (date of PMD prescription) to time 2 (2 years later). Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21. BMI was calculated using the weight (lb) x 703/ (height [inches]).2 Dichotomization of BMI was performed using the conventional cut scores: < 30.0, not obese; and ≥ 30.0, obese. Paired t tests and SPSS general linear model (repeated measures) were used to examine change of BMI from time 1 to time 2. The exact McNemar test was used to examine change in obesity classification across time 1 and time 2. Correlating with Yang’s retrospective observational study, data were analyzed separately for aged < 65 years and aged≥ 65 years.2

Results

Of the 185 veterans, 181 were male (98%); mean age was 67.3 years (range, 26-90); and 55% were aged ≥ 65 years. Musculoskeletal disorders (41.6%) were the most common primary indication for a PMD, followed by pulmonary disorders (25.4%) and cardiovascular disorders (23.8%) (Table 1).

There was a significant decrease in BMI in the first 2 years after receiving a PMD prescription for the first time (estimated marginal means: 31.5 to 30.9 , P = .02). However, age moderated the relationship between BMI and time F[1, 183] = 12.14, P = .001, partial η2 = .06 (Table 2). The 101 subjects aged > 65 years experienced a significant decrease in BMI (estimated marginal means: 30.3 to 29.1, P < .001), whereas the 84 patients aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in BMI (estimated marginal means: 32.9 to 33.1, P = .45). BMI was significantly higher for subjects aged < 65 years at Time 1 (F[1, 183] = 4.32, P = .04, partial η2 = .02) and at Time 2 (F[1, 183] = 11.04, P = .001, partial η2 = .06).

Similarly, there was a significant decrease in weight in the first year after receiving a PMD prescription with a change in mean weight from 219.0 to 215.3 lb (P = .3). Again, age moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 12.81; P < .001; partial η2 = .07). Individuals aged ≥ 65 years experienced a significant decrease in weight (estimated marginal means = 209.4 to 200.9; P < .001), whereas those aged < 65 years experienced a slight and nonsignificant increase in weight (230.6 to 232.6; P = .36). Weight was significantly higher for individuals aged < 65 years at time 1 (F = 5.34; P = .02; partial η2 = .03) and at time 2 (F = 12.18; P = .001; partial η2 = .06).

The percentage of those who were obese (BMI ≥ 30) at time 1 (49.7%) did not significantly change at time 2 (46.5%) (exact McNemar test, P = .26). Similarly, there was no significant change in obesity from time 1 to time 2 for those aged < 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .69) or for those aged ≥ 65 years (exact McNemar test P = .06). Obesity at time 2 was significantly more common in those aged < 65 years (56.0%) than those aged ≥ 65 years (38.6%), χ2 [1] = 5.54; P = .02. Obesity at time 1 did not differ between those aged < 65 years (53.6%) and aged ≥ 65 years (46.5%), η2 [1] = 0.9; P = .34. Obesity moderated the relationship between weight and time (F = 5.10; P = .03; partial η2= .03) in that obese individuals experienced a significant decrease in weight with estimated marginal means (SE) = 264.5 (4.51) to 257.4 (4.97); F = 11.32; P < .001; partial η2 = .06), whereas nonobese individuals had no weight change with estimated marginal means (SE) = 174.0 (4.48) to 173.61 (4.94); F = .03; P < .86; partial η2< .01).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a significant decrease in both weight and BMI at 2 years after the initiation of a PMD in patients aged < 65 years. No significant change was found for obesity rates. However, veterans who met criteria for obesity at the time of PMD prescription saw a significant decrease in their weight at 2 years compared with those who were nonobese.

VHA supports power mobility when there is a clear functional need that cannot be met by rehabilitation, surgical, or medical interventions to enhance veterans’ abilities to access medical care, accomplish necessary tasks of daily living, and to have greater access to their communities. Though limited by strength of association, studies involving PMD users generally found improvement in reported functional outcomes and overall satisfaction with PMD use based on a systematic review.13 Nonetheless, there is an implicit concern among providers that a PMD prescription, by limiting physical activity, may exacerbate obesity trends in potentially high-risk individuals.

However, a controversy exists about whether increasing physical activity alone leads to weight loss. A 2007 study followed 102 sedentary men and 100 women over 1 year randomized to moderately intensive exercise for 60 minutes, 6 days a week vs no intervention.14 The men lost an average of 4 pounds, and women lost an average of 3 pounds after 1 year. The Women’s Health Study divided 39,876 women into high, medium, and low levels of exercise groups. After 10 years, the intense exercise group did not have any significant weight loss.15

Our study was consistent with existing literature in that a PMD prescription did not correlate with weight gain.2,9 In our veteran population aged ≥ 65 years, we observed an opposite trend of weight loss after PMD prescription. Of note, studies have shown that peak body weight occurs in the sixth decade, remains stable until about aged 70 years, and then slowly decreases thereafter, at a rate of 0.1 to 0.2 kg per year.16 This likely explains some of the weight loss trend we observed in our study of veterans aged ≥ 65 years. Possible additional explanations include improved access to health care and to more nutritional foods that promote general health and well-being.

Limitations

The data were gathered from a predominantly male veteran population, potentially limiting generalizability. The health of any individual is determined by the interaction of factors of which body weight is just a single, isolated component. As such, the effect of powered mobility on body weight is not a direct reflection on the effect on overall health. Additionally, there are many factors that may affect an individual’s body weight, such as optimal management of medical comorbidities, which could not be controlled for in this study. Also, while these values can be compared with other veteran populations, this study had no true control group.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study with aforementioned limitations, PMD use does not seem to be associated with significant weight changes. Further studies using control groups and assessing comorbidities are needed.

1. Perlin J. Clinical practice recommendations for motorized wheeled mobility devices: scooters, pushrim-activated power-assist wheelchairs, power wheelchairs, and power wheelchairs with enhanced function. Published 2004. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/Docs/Motorized_Wheeled_Mobility_Devices.pdf

2. Yang W, Wilson L, Oda I, Yan J. The effect of providing power mobility on weight change. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):746-753. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31813e0645

3. Yang, L, Colditz GA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 2007-2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(8):1412–1413. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2405

4. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020.

5. Almond N, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L, Porterfield D. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among U.S. military veterans. Mil Med. 2008;173(6):544-549. doi:10.7205/milmed.173.6.544

6. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

7. Bray G. Medical consequences of obesity. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2583-2589. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0535

8. Fox MH, Witten MH, Lullo C. Reducing obesity among people with disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2014;25(3):175-185. doi:10.1177/1044207313494236

9. Zagol BW, Krasuski RA. Effect of motorized scooters on quality of life and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(5):672-676. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.049

10. Traxinger K, Kelly C, Johnson BA, Lyles RH, Glass JD. Prognosis and epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: analysis of a clinic population, 1997-2011. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3(4):313-320. doi:10.1212/cpj.0b013e3182a1b8ab

11. Wolf J, Safer A, Wöhrle J, et al. Factors predicting one-year mortality in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients—data from a population-based registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):197. doi:10.1186/s12883-014-0197-9

12. Körner S, Hendricks M, Kollewe K, et al. Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement intake in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): impact on quality of life and therapeutic options. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-84

13. Auger CJ, Demers L, Gélinas I, et al. Powered mobility for middle-aged and older adults: systematic review of outcomes and appraisal of published evidence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(8):666-680. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31816de163

14. McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin M, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1496-512. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.178

15. Lee IM, Djoussé L, Sesso H, Wang L, Buring JE . Physical activity and weight gain prevention, women’s health study. JAMA. 2010;303(12):1173-1179. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.312

16. Wallace J, Schwartz R. Epidemiology of weight loss in humans with special reference to wasting in the elderly. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00246-2

1. Perlin J. Clinical practice recommendations for motorized wheeled mobility devices: scooters, pushrim-activated power-assist wheelchairs, power wheelchairs, and power wheelchairs with enhanced function. Published 2004. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/Docs/Motorized_Wheeled_Mobility_Devices.pdf

2. Yang W, Wilson L, Oda I, Yan J. The effect of providing power mobility on weight change. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):746-753. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31813e0645

3. Yang, L, Colditz GA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 2007-2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(8):1412–1413. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2405

4. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020.

5. Almond N, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L, Porterfield D. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among U.S. military veterans. Mil Med. 2008;173(6):544-549. doi:10.7205/milmed.173.6.544

6. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3962-1

7. Bray G. Medical consequences of obesity. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2583-2589. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0535

8. Fox MH, Witten MH, Lullo C. Reducing obesity among people with disabilities. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2014;25(3):175-185. doi:10.1177/1044207313494236

9. Zagol BW, Krasuski RA. Effect of motorized scooters on quality of life and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(5):672-676. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.049

10. Traxinger K, Kelly C, Johnson BA, Lyles RH, Glass JD. Prognosis and epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: analysis of a clinic population, 1997-2011. Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3(4):313-320. doi:10.1212/cpj.0b013e3182a1b8ab

11. Wolf J, Safer A, Wöhrle J, et al. Factors predicting one-year mortality in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients—data from a population-based registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):197. doi:10.1186/s12883-014-0197-9

12. Körner S, Hendricks M, Kollewe K, et al. Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement intake in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): impact on quality of life and therapeutic options. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-84

13. Auger CJ, Demers L, Gélinas I, et al. Powered mobility for middle-aged and older adults: systematic review of outcomes and appraisal of published evidence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(8):666-680. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31816de163

14. McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin M, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(6):1496-512. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.178

15. Lee IM, Djoussé L, Sesso H, Wang L, Buring JE . Physical activity and weight gain prevention, women’s health study. JAMA. 2010;303(12):1173-1179. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.312

16. Wallace J, Schwartz R. Epidemiology of weight loss in humans with special reference to wasting in the elderly. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00246-2

Biden vaccine mandate rule could be ready within weeks

The emergency rule ordering large employers to require COVID-19 vaccines or weekly tests for their workers could be ready “within weeks,” officials said in a news briefing Sept. 10.

Labor Secretary Martin Walsh will oversee the Occupational Safety and Health Administration as the agency drafts what’s known as an emergency temporary standard, similar to the one that was issued a few months ago to protect health care workers during the pandemic.

The rule should be ready within weeks, said Jeff Zients, coordinator of the White House COVID-19 response team.

He said the ultimate goal of the president’s plan is to increase vaccinations as quickly as possible to keep schools open, the economy recovering, and to decrease hospitalizations and deaths from COVID.

Mr. Zients declined to set hard numbers around those goals, but other experts did.

“What we need to get to is 85% to 90% population immunity, and that’s going to be immunity both from vaccines and infections, before that really begins to have a substantial dampening effect on viral spread,” Ashish Jha, MD, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., said on a call with reporters Sept. 9.

He said immunity needs to be that high because the Delta variant is so contagious.

Mandates are seen as the most effective way to increase immunity and do it quickly.

David Michaels, PhD, an epidemiologist and professor at George Washington University, Washington, says OSHA will have to work through a number of steps to develop the rule.

“OSHA will have to write a preamble explaining the standard, its justifications, its costs, and how it will be enforced,” says Dr. Michaels, who led OSHA for the Obama administration. After that, the rule will be reviewed by the White House. Then employers will have some time – typically 30 days – to comply.

In addition to drafting the standard, OSHA will oversee its enforcement.

Companies that refuse to follow the standard could be fined $13,600 per violation, Mr. Zients said.

Dr. Michaels said he doesn’t expect enforcement to be a big issue, and he said we’re likely to see the rule well before it is final.

“Most employers are law-abiding. When OSHA issues a standard, they try to meet whatever those requirements are, and generally that starts to happen when the rule is announced, even before it goes into effect,” he said.

The rule may face legal challenges as well. Several governors and state attorneys general, as well as the Republican National Committee, have promised lawsuits to stop the vaccine mandates.

Critics of the new mandates say they impinge on personal freedom and impose burdens on businesses.

But the president hit back at that notion Sept. 10.

“Look, I am so disappointed that, particularly some of the Republican governors, have been so cavalier with the health of these kids, so cavalier of the health of their communities,” President Biden told reporters.

“I don’t know of any scientist out there in this field who doesn’t think it makes considerable sense to do the six things I’ve suggested.”

Yet, others feel the new requirements didn’t go far enough.

“These are good steps in the right direction, but they’re not enough to get the job done,” said Leana Wen, MD, in an op-ed for The Washington Post.

Dr. Wen, an expert in public health, wondered why President Biden didn’t mandate vaccinations for plane and train travel. She was disappointed that children 12 and older weren’t required to be vaccinated, too.

“There are mandates for childhood immunizations in every state. The coronavirus vaccine should be no different,” she wrote.

Vaccines remain the cornerstone of U.S. plans to control the pandemic.

On Sept. 10, there was new research from the CDC and state health departments showing that the COVID-19 vaccines continue to be highly effective at preventing severe illness and death.

But the study also found that the vaccines became less effective in the United States after Delta became the dominant cause of infections here.

The study, which included more than 600,000 COVID-19 cases, analyzed breakthrough infections – cases where people got sick despite being fully vaccinated – in 13 jurisdictions in the United States between April 4 and July 17, 2021.

Epidemiologists compared breakthrough infections between two distinct points in time: Before and after the period when the Delta variant began causing most infections.

From April 4 to June 19, fully vaccinated people made up just 5% of cases, 7% of hospitalizations, and 8% of deaths. From June 20 to July 17, 18% of cases, 14% of hospitalizations, and 16% of deaths occurred in fully vaccinated people.

“After the week of June 20, 2021, when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant became predominant, the percentage of fully vaccinated persons among cases increased more than expected,” the study authors wrote.

Even after Delta swept the United States, fully vaccinated people were 5 times less likely to get a COVID-19 infection and more than 10 times less likely to be hospitalized or die from one.

“As we have shown in study after study, vaccination works,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said during the White House news briefing.

“We have the scientific tools we need to turn the corner on this pandemic. Vaccination works and will protect us from the severe complications of COVID-19,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The emergency rule ordering large employers to require COVID-19 vaccines or weekly tests for their workers could be ready “within weeks,” officials said in a news briefing Sept. 10.

Labor Secretary Martin Walsh will oversee the Occupational Safety and Health Administration as the agency drafts what’s known as an emergency temporary standard, similar to the one that was issued a few months ago to protect health care workers during the pandemic.

The rule should be ready within weeks, said Jeff Zients, coordinator of the White House COVID-19 response team.

He said the ultimate goal of the president’s plan is to increase vaccinations as quickly as possible to keep schools open, the economy recovering, and to decrease hospitalizations and deaths from COVID.

Mr. Zients declined to set hard numbers around those goals, but other experts did.

“What we need to get to is 85% to 90% population immunity, and that’s going to be immunity both from vaccines and infections, before that really begins to have a substantial dampening effect on viral spread,” Ashish Jha, MD, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., said on a call with reporters Sept. 9.

He said immunity needs to be that high because the Delta variant is so contagious.

Mandates are seen as the most effective way to increase immunity and do it quickly.

David Michaels, PhD, an epidemiologist and professor at George Washington University, Washington, says OSHA will have to work through a number of steps to develop the rule.

“OSHA will have to write a preamble explaining the standard, its justifications, its costs, and how it will be enforced,” says Dr. Michaels, who led OSHA for the Obama administration. After that, the rule will be reviewed by the White House. Then employers will have some time – typically 30 days – to comply.

In addition to drafting the standard, OSHA will oversee its enforcement.

Companies that refuse to follow the standard could be fined $13,600 per violation, Mr. Zients said.

Dr. Michaels said he doesn’t expect enforcement to be a big issue, and he said we’re likely to see the rule well before it is final.

“Most employers are law-abiding. When OSHA issues a standard, they try to meet whatever those requirements are, and generally that starts to happen when the rule is announced, even before it goes into effect,” he said.

The rule may face legal challenges as well. Several governors and state attorneys general, as well as the Republican National Committee, have promised lawsuits to stop the vaccine mandates.

Critics of the new mandates say they impinge on personal freedom and impose burdens on businesses.

But the president hit back at that notion Sept. 10.

“Look, I am so disappointed that, particularly some of the Republican governors, have been so cavalier with the health of these kids, so cavalier of the health of their communities,” President Biden told reporters.

“I don’t know of any scientist out there in this field who doesn’t think it makes considerable sense to do the six things I’ve suggested.”

Yet, others feel the new requirements didn’t go far enough.

“These are good steps in the right direction, but they’re not enough to get the job done,” said Leana Wen, MD, in an op-ed for The Washington Post.

Dr. Wen, an expert in public health, wondered why President Biden didn’t mandate vaccinations for plane and train travel. She was disappointed that children 12 and older weren’t required to be vaccinated, too.

“There are mandates for childhood immunizations in every state. The coronavirus vaccine should be no different,” she wrote.

Vaccines remain the cornerstone of U.S. plans to control the pandemic.

On Sept. 10, there was new research from the CDC and state health departments showing that the COVID-19 vaccines continue to be highly effective at preventing severe illness and death.

But the study also found that the vaccines became less effective in the United States after Delta became the dominant cause of infections here.

The study, which included more than 600,000 COVID-19 cases, analyzed breakthrough infections – cases where people got sick despite being fully vaccinated – in 13 jurisdictions in the United States between April 4 and July 17, 2021.

Epidemiologists compared breakthrough infections between two distinct points in time: Before and after the period when the Delta variant began causing most infections.

From April 4 to June 19, fully vaccinated people made up just 5% of cases, 7% of hospitalizations, and 8% of deaths. From June 20 to July 17, 18% of cases, 14% of hospitalizations, and 16% of deaths occurred in fully vaccinated people.

“After the week of June 20, 2021, when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant became predominant, the percentage of fully vaccinated persons among cases increased more than expected,” the study authors wrote.

Even after Delta swept the United States, fully vaccinated people were 5 times less likely to get a COVID-19 infection and more than 10 times less likely to be hospitalized or die from one.

“As we have shown in study after study, vaccination works,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said during the White House news briefing.

“We have the scientific tools we need to turn the corner on this pandemic. Vaccination works and will protect us from the severe complications of COVID-19,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The emergency rule ordering large employers to require COVID-19 vaccines or weekly tests for their workers could be ready “within weeks,” officials said in a news briefing Sept. 10.

Labor Secretary Martin Walsh will oversee the Occupational Safety and Health Administration as the agency drafts what’s known as an emergency temporary standard, similar to the one that was issued a few months ago to protect health care workers during the pandemic.

The rule should be ready within weeks, said Jeff Zients, coordinator of the White House COVID-19 response team.

He said the ultimate goal of the president’s plan is to increase vaccinations as quickly as possible to keep schools open, the economy recovering, and to decrease hospitalizations and deaths from COVID.

Mr. Zients declined to set hard numbers around those goals, but other experts did.

“What we need to get to is 85% to 90% population immunity, and that’s going to be immunity both from vaccines and infections, before that really begins to have a substantial dampening effect on viral spread,” Ashish Jha, MD, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, R.I., said on a call with reporters Sept. 9.

He said immunity needs to be that high because the Delta variant is so contagious.

Mandates are seen as the most effective way to increase immunity and do it quickly.

David Michaels, PhD, an epidemiologist and professor at George Washington University, Washington, says OSHA will have to work through a number of steps to develop the rule.

“OSHA will have to write a preamble explaining the standard, its justifications, its costs, and how it will be enforced,” says Dr. Michaels, who led OSHA for the Obama administration. After that, the rule will be reviewed by the White House. Then employers will have some time – typically 30 days – to comply.

In addition to drafting the standard, OSHA will oversee its enforcement.

Companies that refuse to follow the standard could be fined $13,600 per violation, Mr. Zients said.

Dr. Michaels said he doesn’t expect enforcement to be a big issue, and he said we’re likely to see the rule well before it is final.

“Most employers are law-abiding. When OSHA issues a standard, they try to meet whatever those requirements are, and generally that starts to happen when the rule is announced, even before it goes into effect,” he said.

The rule may face legal challenges as well. Several governors and state attorneys general, as well as the Republican National Committee, have promised lawsuits to stop the vaccine mandates.

Critics of the new mandates say they impinge on personal freedom and impose burdens on businesses.

But the president hit back at that notion Sept. 10.

“Look, I am so disappointed that, particularly some of the Republican governors, have been so cavalier with the health of these kids, so cavalier of the health of their communities,” President Biden told reporters.

“I don’t know of any scientist out there in this field who doesn’t think it makes considerable sense to do the six things I’ve suggested.”

Yet, others feel the new requirements didn’t go far enough.

“These are good steps in the right direction, but they’re not enough to get the job done,” said Leana Wen, MD, in an op-ed for The Washington Post.

Dr. Wen, an expert in public health, wondered why President Biden didn’t mandate vaccinations for plane and train travel. She was disappointed that children 12 and older weren’t required to be vaccinated, too.

“There are mandates for childhood immunizations in every state. The coronavirus vaccine should be no different,” she wrote.

Vaccines remain the cornerstone of U.S. plans to control the pandemic.

On Sept. 10, there was new research from the CDC and state health departments showing that the COVID-19 vaccines continue to be highly effective at preventing severe illness and death.

But the study also found that the vaccines became less effective in the United States after Delta became the dominant cause of infections here.

The study, which included more than 600,000 COVID-19 cases, analyzed breakthrough infections – cases where people got sick despite being fully vaccinated – in 13 jurisdictions in the United States between April 4 and July 17, 2021.

Epidemiologists compared breakthrough infections between two distinct points in time: Before and after the period when the Delta variant began causing most infections.

From April 4 to June 19, fully vaccinated people made up just 5% of cases, 7% of hospitalizations, and 8% of deaths. From June 20 to July 17, 18% of cases, 14% of hospitalizations, and 16% of deaths occurred in fully vaccinated people.

“After the week of June 20, 2021, when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant became predominant, the percentage of fully vaccinated persons among cases increased more than expected,” the study authors wrote.

Even after Delta swept the United States, fully vaccinated people were 5 times less likely to get a COVID-19 infection and more than 10 times less likely to be hospitalized or die from one.

“As we have shown in study after study, vaccination works,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said during the White House news briefing.

“We have the scientific tools we need to turn the corner on this pandemic. Vaccination works and will protect us from the severe complications of COVID-19,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Implementation and Impact of a β -Lactam Allergy Assessment Protocol in a Veteran Population

Allergies to β-lactam antibiotics are among the most documented drug allergies, and approximately 10% of the US population reports an allergy specifically to penicillin.1,2 Many allergic reactions are mediated via the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), producing an immediate hypersensitivity response, such as hives or anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. Reactions also may be mediated by T cells of the immune system, which target various cell lines and can cause a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).3Although β-lactam and penicillin allergies are frequently reported, < 5% manifest as either an IgE or T-cell–mediated response.4Furthermore, for the small proportion of patients who once had a true IgE-mediated reaction, including anaphylaxis, 80% experience a decrease in IgE antibodies over time, resulting in a loss of allergic response after about 10 years.2 Due to this decline in IgE response and the initial mislabeling of mild non-IgE penicillin reactions, 95% of patients who are labeled as penicillin-allergic can eventually tolerate a penicillin.2

When a patient’s β-lactam allergy is never reevaluated, negative consequences can ensue. This allergy in a patient’s medical record can lead to the inappropriate avoidance of the entire β-lactam antibiotic class, which includes all penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems. Withholding these antibiotics in certain situations can lead to negative patient outcomes.5-7 For example, the drugs of choice for the infections syphilis and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) are a penicillin or cephalosporin, and patients labeled as penicillin-allergic are more likely to experience treatment failure from using second-line therapies.8 Additionally, receiving non-β-lactam antibiotics puts patients at risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens like methicillin-resistant S aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) as well as adverse effects, such as Clostridioides difficile infection.9 Using alternative, and likely broad-spectrum, antibiotics also can be financially detrimental: These medications often are more costly than their β-lactam alternatives, and the inappropriate use of therapies can result in longer hospital courses.9-11

Penicillin allergies can complicate the antibiotic treatment strategy. The Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MVAMC) in Tennessee recently examined the negative sequelae of β-lactam allergies and found that more than half the patients received inappropriate antibiotics based on guideline recommendations, allergy history, and culture and sensitivity data.12 To mitigate the problems for patients with β-lactam allergies, the 2016 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) on the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASP) recommend that these patients undergo allergy assessment and penicillin skin testing.13In November 2017, MVAMC implemented such a process. The purpose of this study was to describe our pharmacist-run β-lactam allergy assessment (BLAA) protocol and penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) and evaluate their overall outcomes: the proportion of patients who have been cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam antibiotic or who have had their allergy removed altogether.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study with approval from the institutional review board at MVAMC. This institution is an academic teaching center with 240 acute care beds and a variety of outpatient clinics available at the main campus, serving veterans in Memphis and the Mid-South area, including west Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and northeastern Arkansas. Patients were consecutively evaluated from November 2017 through February 2020. All MVAMC patients with a documented β-lactam allergy were eligible for inclusion; there were no exclusion criteria. Electronic health record data were assessed and included basic patient demographics, allergy history, and the outcome of the BLAA and PAC. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis.

The purpose of the BLAA process is to evaluate, clarify, and potentially clear patients of their β-lactam allergies. Started in November 2017, the process includes appropriate patient screening with documentation of the β-lactam allergy. When patients with a β-lactam allergy are admitted to the hospital, they are interviewed by an inpatient CPS. This pharmacist then enters an assessment into the patient’s chart, which includes details of the allergen, reaction, and timing of the event. Based on this information, the CPS provides recommendations: clearance for alternative β-lactams, avoidance of all β-lactams, or removal of the allergy.

In January 2019, the pharmacist-driven penicillin allergy clinic (PAC) was started. Eligible patients receive a skin test to confirm or rule out their allergy after hospital discharge. To facilitate patient identification and screening, the ASP/infectious diseases (ID) clinical pharmacist runs a daily report of hospitalized patients with documented β-lactam allergies. All inpatient CPSs had access to this report and could easily identify and interview patients. Following the interview, the pharmacist enters a note in the patient’s chart, using the BLAA template (eFigures 1 and 2). On completion, a note is viewable in the Notes section adjacent to the patient’s allergies. The pharmacist then can enter a PAC consult for eligible patients. Although most patients qualify for PAC, exclusion criteria include non–IgE-mediated allergies (ie, SJS/TEN), allergies to β-lactams other than penicillins, or recent reactions (ie, within the past 5 years). Each inpatient CPS is trained on this BLAA process, which includes patient screening, chart review, patient interviewing, and the BLAA template and note completion. Pharmacists must demonstrate competency in completing 5 BLAA notes with review from the ASP/ID pharmacist. Once training is completed, this process is integrated into the pharmacist’s everyday workflow.

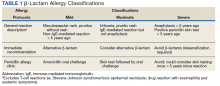

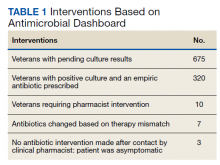

On receipt of the PAC consult, the ASP/ID pharmacist reviews the patient chart to further assess for eligibility and to determine whether oral challenge alone or skin testing followed by the oral challenge is required based on patient risk stratification (Table 1).3Relative contraindications to PAC include severe or unstable lung disease that requires home oxygen, frequent or recurrent heart failure exacerbations, or patients with acute or unstable cardiopulmonary, neurologic, or mental health conditions. These scenarios are discussed case by case with the allergy/immunology (A/I) physician.

The ASP/ID pharmacist also reviews the patient’s chart for medications that may blunt the histamine response during drug testing. The need to hold these medications before PAC also are individually assessed in conjunction with the A/I physician. The ASP/ID pharmacist and 3 other CPS involved in the creation of the BLAA and PAC have received formal hands-on training on penicillin allergy testing. The PAC process consists of a penicillin skin test, followed by the amoxicillin oral challenge.3The ASP/ID clinical pharmacist who is trained in penicillin skin testing performs all duties in PAC, with oversight from the A/I attending physician as needed. Currently, the ASP/ID pharmacist runs the PAC once a week with the A/I physician available if needed. Along with documenting an A/I clinic note detailing the events of PAC, the ASP/ID pharmacist also will add an addendum to the original BLAA note. If the allergy is removed through direct testing, it also can be removed from the patient’s profile after discussion with the A/I physician. Therefore, the full details necessary to evaluate, clarify, and clear the patient of their β-lactam allergy are in one place.

Results

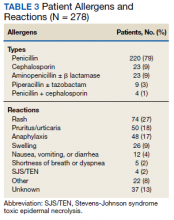

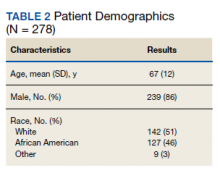

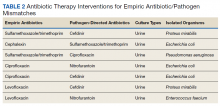

We evaluated 278 patients, using the BLAA protocol. In this veteran population, patients were generally older males and evenly split between African American and White patients (Table 2). Most patients reported an allergy to penicillin, with a rash being the most common reaction (Table 3).

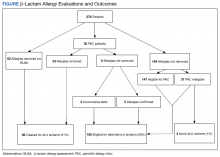

Of the 278 assessed, 246 patients were evaluated via our BLAA alone and were not seen in PAC. We were able to remove 25% of these patients’ allergies by performing a thorough assessment. Of the 184 patients whose allergies could not be removed via the BLAA alone, 147 (80%) were still eligible for PAC but are awaiting scheduling. Patients ineligible for PAC included those with a cephalosporin allergy or a severe and non–IgE-mediated reaction. Other ineligible patients who were not eligible included those with diseases where risk of testing outweighed the benefits.

Of the 32 patients who were seen in PAC, 75% of allergies were removed through direct testing. No differences between race or gender were observed. Of the 8 patients (25%) whose allergies were not removed, 5 had confirmed penicillin allergies with a positive reaction; 4 of these patients have since tolerated an alternative β-lactam (either a cephalosporin or carbapenem). Three patients had inconclusive tests, most often because their positive control was nonreactive during the percutaneous portion of the skin test; these allergies could neither be confirmed nor removed. Two of these patients have since tolerated alternative β-lactams (both cephalosporins). Although these 8 patients should not be rechallenged with a penicillin antibiotic, they could still be considered for alternative β-lactams, based on the nature and histories of their allergies.

In total, we removed 86 allergies (31% of our patient population) using both BLAA and PAC (Figure). These patients were cleared for all β-lactams. One hundred eighty-eight patients (68%) were cleared to receive an alternative β-lactam based on the nature or history of the allergic reaction. β-lactam avoidance was recommended for only 4 patients (1%), as they had no exposure to any β-lactams, and they had a recent or severe reaction: 2 patients with anaphylaxis in the past 5 years, 1 with SJS/TEN, and 1 with recent convulsions after receiving cefepime. Combining patients whose penicillin allergies were removed with those who had been cleared for alternative β-lactam antibiotics, 99% of patients were cleared for a β-lactam antibiotic.

Discussion

We have implemented a unique and efficient way to evaluate, clarify, and clear β-lactam allergies. Our BLAA protocol allows for a smooth process by distributing the workload of evaluating and clarifying patients’ allergies over many inpatient CPS. Furthermore, the BLAA is readily accessible to health care providers (HCPs), allowing for optimal clinical decision making. HCPs can quickly gather further information on the β-lactam allergy, while seeing actionable recommendations, along with documentation of the PAC visit and subsequent events, if the patient has been seen.

This study demonstrated the promotion of alternative β-lactam use for nearly all patients: 99% of our patient population were deemed candidates for a β-lactam type antibiotic. This percentage included patients whose allergies have been fully cleared, both through BLAA alone and in PAC. Also included are patients who have been cleared for an alternative β-lactam and not necessarily a penicillin.

In our PAC, 8 patients were not cleared for penicillins: 5 had penicillin allergies confirmed, and 3 had inconclusive results. Based on the nature of their reactions and previous tolerance of alternative β-lactams, those 5 patients are still eligible for alternative β-lactams. Additionally, the 3 patients with inconclusive results are also eligible for alternative β-lactams for the same reasons. The patients for whom

Accounting for those patients who have not been seen in PAC, our results are in concordance with previous studies, which demonstrated that implementation of a similar BLAA process results in clearance of ≥ 90% of penicillin allergies.13-17Other studies have evaluated inpatient implementation of penicillin skin testing or oral challenges; in this study, however, BLAAs were completed while the patient was hospitalized, and patients were seen in PAC after discharge. Completing BLAA during hospitalization not only allows for faster assessment and facilitates decision making regarding most patients’ antibiotic regimens, but also provides a tool that can be used by many pharmacists and HCPs. The addition of our PAC to the BLAA protocol further strengthens the impact on clearance of patients’ penicillin allergies.

Limitations

Although our study demonstrates many benefits of implementation of a BLAA protocol and PAC, it has several limitations. This analysis was a retrospective review of the limited number of patients who had assessments completed. Additionally, many patients were waiting to be seen in PAC. This delay is largely due to the length of time to establish our pharmacist-run PAC, the limited number of pharmacists trained and available for skin testing, the time constraints of our staff, and COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, only pharmacists administer the BLAA questionnaire, but this process could be expanded to other professionals such as nursing staff. Also, this study was not set up as a before-and-after analysis that examined outcomes associated with individual patients. Future directions include assessing the clinical impact of this protocol, such as evaluating provider utilization of β-lactam antibiotics for patients with penicillin allergies and determining associated cost savings.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that implementation of a pharmacist-driven BLAA protocol and PAC can effectively remove inaccurate penicillin allergy labels and clear patients for alternative β-lactam antibiotic use. The BLAA process in conjunction with PAC will continue to be used to better evaluate, clarify, and clear patient allergies to optimize their care.

1. Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819-2822. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.18.2819

2. Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188-199. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

3. Castells M, Khan DA, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2338-2351. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807761

4. Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, Li JTC. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681-687. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61100-3

5. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):361-367. doi:10.1093/cid/civ308

6. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294-300.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

7. Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):741-749. doi:10.1093/cid/civ394

8. Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding β-lactams in patients with β-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1148-1153. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.026

9. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci2013.09.021

10. Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

11. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin-allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):501-506. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01638.x

12. Ness RA, Bennett JG, Elliott WV, Gillion AR, Pattanaik DN. Impact of β-lactam allergies on antimicrobial selection in an outpatient setting. South Med J. 2019;112(11):591-597. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001037

13. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw118

14. King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67-71. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021

15. Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):686-693. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045

16. Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing of clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341-345. doi:10.1002/jhm.2036

17. Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):155-161. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw155

Allergies to β-lactam antibiotics are among the most documented drug allergies, and approximately 10% of the US population reports an allergy specifically to penicillin.1,2 Many allergic reactions are mediated via the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), producing an immediate hypersensitivity response, such as hives or anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. Reactions also may be mediated by T cells of the immune system, which target various cell lines and can cause a drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).3Although β-lactam and penicillin allergies are frequently reported, < 5% manifest as either an IgE or T-cell–mediated response.4Furthermore, for the small proportion of patients who once had a true IgE-mediated reaction, including anaphylaxis, 80% experience a decrease in IgE antibodies over time, resulting in a loss of allergic response after about 10 years.2 Due to this decline in IgE response and the initial mislabeling of mild non-IgE penicillin reactions, 95% of patients who are labeled as penicillin-allergic can eventually tolerate a penicillin.2